Larry Brooks's Blog, page 19

December 6, 2014

The Role of Concept in a Real-World Story

Quick story to encapsulate the mindset – complete with barriers and old tapes and other priorities – of the writer who struggles with the notion of concept.

Concept, of course, is the presence of something conceptual within a story.

It’s not the story itself, but rather, the landscape for one. A framework. A compelling notion or proposition. It can be thematic (as it was in “The Help), it can be an issue of character (as is the case in any successful series). It can even simply be a fascinating moment in history, provided you don’t settle for that and launch a dramatic question within it.

Concept is one of the Six Core Competencies that I write about . Because it’s always there, yet not always something that is leveraged in the story… particularly in rejected stories.

Make a note of that. One of the things that gets stories published is the presence of something compellingly conceptual at its heart.

In all cases, in all genres…

… the presence of something conceptual that becomes the context for the story… is something that fuels the story with interest even before, and always in context to, plot and character.

Thing is, concept has a different role, and a different nature, from genre to genre.

If you write in one genre only, then you need to understand the nature and role of concept in your genre.

If you write in multiple genres, then you are a like a general practitioner in medicine, you need to become the master of several conceptual disciplines, each of them unique.

This is the thing missing from the conversation about concept…

… and why it confuses so many. (Click HERE for a previous Storyfix post on this). I experienced this first-hand this fall when I was teaching a full-weekend workshop to three dozen very passionate and accomplished romance authors.

I realized that I was the source of one writer’s confusion. As a guy who makes his living writing and teaching this stuff, that was an alarming feeling.

Romance is one of the genres in which concept is always challenging and often confusing. Because the genre itself is a concept, and from that writers make the mistake of not seeking a deeper level of conceptual framework for their stories.

Also, many writers use the work of their favorite romance authors as a model. And those may not rely on concept as heavily as this implies they should. Don’t be fooled, though. They can get by on premise alone. Their name IS the concept.

For us, though, we need to break in with something stronger than just another day in the love business.

Here’s how it went down.

I was doing my thing about concept, using it as the stage upon which the rest of craft shows itself. A story doesn’t solely depend on skill and structure to work, the raw material of the story itself – the inherent conceptual grist of it – is a huge factor.

A boring, normal, slice of life story, well told, will still be boring. Unless that life is interesting… which by definition makes it conceptual. But a meaty conceptual framework… now that’s something to work with.

So there I was, doing my whole concept dance, giving examples, defining and comparing and contrasting, asking for their concepts and analyzing as a group, and I’d used my favorite case study for concept, which is all the stories about Superman.

Ten films, hundreds of comic books, a major television franchise. Each one of them, every single movie and comic and episode, with its own premise. But each of them was framed by – arising from a landscape defined by – the CONCEPT itself. The conceptual notion was was and is Superman.

That seemed to work.

(Quick note here: if you’re not aware that concept and premise are different things, then I hope you’ll dive deeper on this site for that; the difference is huge, and the very thing that might be hindering your progress, or better, empowering your success.)

On the second day, though, as we were diving into their own stories across all of the elements and criteria, one woman’s hand went up. I’d noticed her body language over the course of the workshop – squirming is telling, and facial ticks speak volumes – so I sort of knew that was coming.

Her voice was shaky, her tone challenging. “I write romances. They’re love stories about real people in the real world. I don’t write about superheroes or murders or conspiracies or paranormal powers or schemes or whatever the hell you mean by something “conceptual.”

She held up both hands to show sarcastic quotation marks with her fingers.

“So I don’t really know what this has to do with me. Or with any of us.”

If you’ve ever been in that moment, when someone calls you out in front of a group, when they have a legit point (one that illustrates some combination of my own failure to clarify and her resistance because she was stuck in the limiting belief of a narrow paradigm), you know what that was like for me.

Could have heard a dangling participle drop in that room.

You see, romance is a great playing field for concept.

Concept within a romance, or a mystery (perhaps the second most challenging genre within which to leverage concept… in both cases as differentiated from premise) is one of best ways to elevate a story from a very crowded field.

But you have to dig for it.

One of the writers in the room was having huge success – as in, hundreds of thousands of copies sold in the past few months – with her latest romance, and I used that story as an example. (Click HERE to have a look.)

Her story had a killer concept. Killer, in the sense that it fit perfectly within the romance genre. It didn’t rely on paranormal powers or superheroes at all, and yet it was the very thing that made the novel work.

In her story a recently single woman buys an old house, concurrent with meeting a handsome stranger in town. As she begins to remodel, she finds an old journal hidden beneath the floorboards, telling a story – a love story – from half a century ago. It had war and tragedy in it, too.

Boom. There’s a concept. No capes or ghosts in sight.

The hero (heroine, in the context of the romance trade, where they still differentiate gender in this regard) became fascinated by this. As a means of her own healing, she wanted to track down the author and return the journals to him, and in doing so her path crosses not only with that of the handsome stranger, but with an entire family dynamic that links to the journals themselves.

That is conceptual. It is a compelling notion, standing alone before we meet anyone (because the house and the journals were there), and it fuels the plot itself. It is a catalyst for the story.

I hit them this simple example, too:

You have a love story. Do you have a concept yet, simply by being a love story? Yes… and it is as vanilla and pedestrian and less-than-compelling as can be, because so far it is exactly like every other incoming romance manuscript in this regard. Two people, falling in love… somehow.

So what would make this conceptual, yet keep it within the mainstream romance genre? Many answers raise their hand here.

A love story in a nunnery. A love story among White House staffers. A love story in the military. A love story told in flashback in the presence of present-day dementia (one Nicholas Sparks used that one to great effect). A love story with amnesia. With a violent ex lover lurking. With a criminal past in play. A love story in a real world in the presence of conceptual pressures… like office politics, legal issues, racial issues, sexual preference issues… the field is wide and long.

It could be as easy as giving your players conceptual careers — jobs that are interesting and vicarious, work that is fascinating and meaningful. Or hobbies… maybe one is a skydiver and the other is terrified of heights.

A love story among brain surgeons, for example. Or lawyers. Or teachers. Or bank robbers. Anything that creates a compelling arena for your otherwise “real world” love story.

Nobody is suggesting you cast your romance with superheroes or spin them around conspiracies (ironically, there are sub-genres of romance that do just that, and each of them has its own expectations, limits and opportunities where concept is concerned). The opportunity, rather, is to infuse your setting, your story ambiance, and your characters with something that is conceptual in nature, as defined by imbuing it with something that is compelling as a stage upon which your otherwise “real and normal” love story will unfold.

All effective fiction requires conflict.

Romances are not a diary of “what happened” as the sole narrative spine. By definition, there are problems that must be conquered, perhaps villains to defeat, and things to overcome… all of it presenting conflict and obstacles to the two lovers ending up together.

The source of conflict is your opportunity to become conceptual.

Really, in romance this should be obvious. Because if the HEA (Happily Ever After) is a non-negotiable trope of the genre, then we already know how it will end – there’s no suspense on that count – they’ll be together somehow. It is the “somehow” of that where the conflict resides, and is the opportunity for the writer to bring something conceptual to the exposition.

Later that day this writer cornered me in the courtyard outside the meeting room. I couldn’t read her, but her face wasn’t as red, so I was encouraged.

She got it. Said she really thought about it, and realized that there wasn’t a gap in the conversation after all, nor was there an exception where romance novels are concerned.

Conflict is universal to fiction (literary writers, shelve your exception to this and go with me here, for the rest of us this in always true). When the source or genealogy of that conflict is conceptual, the story is already elevated to a place where your characters and your plot will be richer, more emotionally resonance, and perhaps most of all, more vicarious for the reader.

And romance is, if nothing else, a genre that totally depends on the vicarious ride it provides to the reader.

What is conceptual about your story?

Can you describe your concept without having to introduce a hero or a plot? Is your concept a framework or a landscape for a story, standing alone as something compelling?

The acid test is when you pitch your concept just this way.

No premise. No heroine, hero of plot.

If the listener says, “Wow, that’s really interesting, I’d like to hear a story told from that idea,” then you have something conceptual in play.

That’s what everyone, for decades now, has said in response to the concept that underpins every Superman story. Without that cape and those super powers, there is no franchise.

That’s what we said when presented with the concept of Harry Potter: what if there was a school for paranormally gifted children, to teach them how to become better and more powerful witches and wizards?

Yeah, that worked. All of the Potter books had their own separate premise, but all of them sprang from this one single concept.

In romance and in mysteries, you need to bring something conceptual to the setting or the character. It’s harder, because there are boundaries. But reality is full of conceptual hooks, and the enlightened writer will benefit from brainstorming your story basis in this regard.

That’s why Concept is one of the Six Core Competencies.

And why you are missing a huge opportunity if you take the conceptual level of your story for granted.

*****

Would you like another set of eyes – professional eyes – to evaluate your concept? Be among the first to experience my newest story coaching service:

The Quick-Check Concept Analysis, priced at $49.

All I need is your genre, your statement of concept, and a brief look at where you want to go with this relative to premise. By keeping it all under 50 words (the concept alone should be one sentence), we can see how conceptual your story landscape will be.

Well over half of the writers I work with get this wrong, either by skipping concept altogether or making it totally redundant with premise. My evaluation will tell you what’s strong, and what’s missing, relative to your conceptual intentions.

A list of criteria to evaluate your concept is included, along with links to tutorials on the subject.

Pay via Paypal, or ask me to bill you. Turnaround within 72 hours.

(Note: this is a more focused, abbreviated program than the one I’ve been doing, with target criteria shown to assess your answer. It’s new, and will be rolled out officially in January. But it’s available now, in this new format.)

The Role of Concept in a Real-World Story is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post The Role of Concept in a Real-World Story appeared first on Storyfix.com.

December 3, 2014

Can Your Concept be TOO Big?

To open this can of worms…

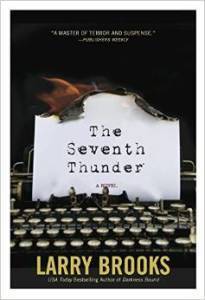

Announcing the re-release of my novel, “The Seventh Thunder.”

The concept is massive. So much so it initially scared agents and publishers away.

A few years ago I used this novel as my calling card to find a new agent. Leveraging the endorsement of my former editor at Penguin-Putnam, I hit up 11 big-name New York agents with the pitch.

All eleven said, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, that they liked it. Three said they were certain it would be published. But not with them involved.

All eleven took a pass.

It was too big. Too provocative. Too rooted in fact, it would make people uncomfortable. Davinci Code uncomfortable. Which made no sense to me since that book sold over 80 million hardcovers.

It was too big. Too provocative. Too rooted in fact, it would make people uncomfortable. Davinci Code uncomfortable. Which made no sense to me since that book sold over 80 million hardcovers.

Too often this business doesn’t make sense.

Can a concept be too big?

Depending on the genre, yes. If you don’t soften it with other things. And if you don’t play to the expectations of the genre’s audience.

The key in any genre is causing readers to suspend disbelief for the ride, and to use enough real-world elements to prop up what seems to be a leap. In sci-fi and fantasy the sky is the limit in this regard. But within a contemporary thriller, certain boundaries are in play.

My secular thriller, The Seventh Thunder, was pushing those boundaries.

In the story I leveraged a lot of real-life elements, which in and of themselves seemed like fiction. A hidden code within the original texts of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible; this has since been disproved by experts, but many still believe in it). A publicity-shy group of ultra-wealthy and powerful Christian men based in Washington (they allow the women to serve at their luncheons) who lobby world leaders to believe as they do. (Here’s a link to a 2003 Harper’s article about them.) Terrorist factions that justify their actions with radical Jihadist belief systems.

Then I pushed things by inserting a mysterious character who may or may not be an agent of something that is more than human. It’s an apocalyptic thriller (though secular, it’s not a “Christian” novel in that sense), after all. Angels and demons do have a role in such things.

And then I added a whopper of a “what if?” proposition.

There is a verse from Revelations (10:4) in which John is transcribing visions of the end of the world, using cryptic language and bizarre images to describe what he saw but couldn’t understand (how could a man who lived 2000 years ago possibly describe an Apache attack helicopter firing air-to-ground missiles?). Seven bowls. Seven trumpets. Seven scrolls. And then, finally, the seven thunders.

But then he is instructed by the angel who is delivering these visions to him to seal this up and “write them not,” because by the will of God no one can know these things, which will come to pass at the end of days.

I always wondered what it was that he saw. Logic says the visions would indicate when, where and how the prophesy would been ignited.

I considered writing a novel about the Rapture as described in Revelations (two guys named LeHaye and Jenkins beat me to it), and wondered what kind of spiritual mess I’d be in if I guessed at it and somehow came too close.

And then it hit me.

This would be the conceptual heart of my novel.

I would wrap my fiction around these real-life elements. In my novel a grieving author writes a book that speculates what those visions were. He looks at the unfolding world geo-political stage and takes a calculated guess at it.

It would soon become clear that he came too close.

When his book emerges from the slush pile and gets viral media buzz, it sends powerful forces of good and evil — one side seeking to eliminate the book and it’s author before publication, the other wanting nothing more than to thwart the will of God and put it on Page 1 — into a frenzy of desperate action.

Because what he wrote is already in play in an election year, with dark agendas and huge consequences on both sides. Suddenly he is the pawn, even a lynchpin, in a global and perhaps supernatural tug of war, with everything at stake.

Big, right?

And it seems ripped, as they say, straight out of today’s headlines. In the upcoming election year, you’ll wonder if there is a little divine intervention going on, given the spooky level of real-world relevance, and considering the book was written in 2008 (then updated for this new issue).

Behold the resurrection… of this novel.

I eventually landed an agent, then another agent, and then a small publisher. The book won an award (2010 “Best Thriller,” Next Generation Indie Awards), and shortly thereafter a larger publisher (Turner, who also published Deadly Faux) scooped it up, and here we are.

The book was re-republished yesterday, December 2, in paperback, hardcover and, coming very soon, on Kindle. It can also be found in select Barnes & Noble stores; if its not there they will order it for you.

I hope you’ll give it a read and decide for yourself.

Think big. Never give up.

There is always, especially in this evolving marketplace, a second chance.

Can Your Concept be TOO Big? is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Can Your Concept be TOO Big? appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 30, 2014

An Easy Approach to Story Building : The Bedtime Story Model

A Holiday Gift to Writers, from Art Holcomb

Novelists and screenwriters are like cousins twice removed. We only cross paths occasionally but, when we start swapping stories, it can be fascinating what each can learn from the other.

(Larry note: it’s also fascinating how much they can resist each other. Which is a shame, because despite popular belief, there is so MUCH crossover relative to structure and craft.)

I have been using a model to help some of my film students find and complete their ideas for a screenplay when all they have is a basic notion and a main character. It was developed by a great screenwriting instructor, Pilar Allesandra, in her groundbreaking book, The Coffee Break Screenwriter.

It wasn’t long before I realized that it offeredpowerful applications for novelists as well. By giving you the basic story model of a fairy tale, it leads you through the story-creating process and gets you thinking about structure without realizing it! I recently shared it with Larry and he encouraged me to share it with you here.

How to begin: Start with an idea that you’ve been thinking about, and fill in the blanks as you go along.

Give it a try on your current project or something new. I think you’ll be VERY surprised with what you come up with:

The Bedtime Story Model

ACT 1 (same as “Part 1″ in novel structure): Once upon a time there was a ____________________( main character) who was ____________________ (character flaw). When ____________________ (obstacle) happened, she ____________________ (flaw-driven strategy). Unfortunately ____________________ (screw up). So she decided ____________________ (goal) and had to ____________________ (action that begins a new journey).

ACT 2A (which is Part 2 in novel structure): In order to take this action, she decided to ____________________ (strategy). Unfortunately ____________________ (obstacle) happened, which caused ____________________ (complication)! Now she had to ____________________ (new task) or risk ____________________ (personal stake)

ACT 2B (which is Part 3 in novel structure) : Where she once wanted to ____________________ (old desire) she now wanted ____________________ (new desire). But how could that happen when ____________________ (obstacle)? Filled with ____________________ (emotion) she____________________ (new action). But this only resulted in ____________________ (low point).

ACT 3 (which is Part 4 in novel structure) : Fortunately, this helped her to realize ____________________ (the solution)! All she had to do was____________________ (action using new lesson)! Using ____________________ (other characters), ____________________ (skills) and ____________________ (tools from the journey) she was able to ____________________ (victorious action). Unfortunately, ____________________ (final hurdle). But this time, she ____________________ (clever strategy)! This resulted in ____________________ (change of situation)

(Larry note: the three-Act structure for film is as immovable as those faces on Mt. Rushmore, so we must accept that. But don’t be fooled at a first glance. Because given that its “Act II” has two separate and equal-length elements, separated by the Midpoint and each with its own contextual mission — the first being a response to the hero’s call as launched by the First Plot Point, and the second post-Midpoint quartile being a proactive attack on the obstacles blocking the hero’s path — it’s really four parts after all.

Just to be clear, both models are almost exactly the same architecture , so don’t be confused. Part of that sameness includes a sequence of four — not three — contextual “quartiles” (roughly; hence, the quote marks) with their own contextually-driven missions relative to how they forward the story’s narrative.

That said, screenwriters — and the teaching of screenwriting in general — is orders of magnitude ahead of the conventional wisdom offered to novelists (although, I have to say, Storyfix is an exception, because one of my goals is to bridge that gap; its one of the reasons Art contributes here… we are on the same page on almost everything about storytelling. Any time you can step into a screenwriting learning opportunity, grab it, it’s pure gold.)

We thank Pilar for this model and I encourage you to pick up her book, The Coffee Break Screenwriter from Michael Wiese Publications. It holds a treasure of storytelling techniques that you can adapt for your latest novel.

Pilar runs a great writing studio in Southern California and you can learn more about her work at onthepage.tv

Until next time – Keep Writing!

Art

Art Holcomb is a novelist and screenwriter who teaches motivated private clients how to move from aspiring to professional writers. You can read more about him, his writing tips and his services at artholcomb.blogspot.com .

Or you can write him at aholcomb07@gmail.com.

An Easy Approach to Story Building : The Bedtime Story Model is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post An Easy Approach to Story Building : The Bedtime Story Model appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 22, 2014

Story Structure: What “going with the flow” Really Means

Anyone who tells you to ignore the principles of story structure is: a) confusing process with outcome; b) telling you to “do it like I do it, because I am a genius,” and c) making the entire storytelling proposition orders of magnitude more difficult, and possibly setting your career back years or even decades.

Let me be clear her: I am NOT telling you to “do it like I do it.” I am telling you to do it in a way that will get you to the finish line more effectively, more blissfully, and with something in your hands that has a shot.

Because this IS how successful stories are built. No matter what your process.

They mean well, but they’ve got it wrong.

Not all of it. They’ll talk about all the contexts and narrative forces that do indeed make a story work. But they aren’t giving you a path to clarity if that is what they advise.

Hey, I say opt for any process you want. Whatever works for you. But be clear: the goal of process is to lead you to what works. And unless you know that… know it like a surgeon knows how to fix a crashing patient… know it like an accountant recognizes something that will get you audited… know it like a parent who won’t allow their children to make up their own boundaries… christening yourself the arbiter of how a story works in a commercial sense is, well, a recipe for failure.

If you do know all this stuff… hey, open that hatch and let it all dump out onto the page any way you choose. Because you are a genius.

For the rest us… there is story structure. And it will never fail you.

Organic storytelling — pantsing — is certainly a viable way to find your story, and to get it into play in a story development sense. But be clear, that’s all it is. If you stamp “Final Draft” onto a manuscript that hasn’t, in fact, landed on the optimal structure for the story you are telling, then you are putting your dream in jeopardy.

Unless you are a seasoned professional who is solidly grounded in the structural arts, or at least you’re a natural freak of nature genius — are you either of those? — this “just get it onto the page” phase will only be the beginning of your structural journey.

Because the story won’t work (key subtlety, right now…) as well as it could UNTIL it begins to align with a certain basic flow. Which is not something you get to make up.

Rather, it’s out there waiting for you to find it.

Those who understand this flow — it is generic, by the way, it’s not something you reinvent every time you tell a story; rather, it’s something you fit your story into — can come very close to structural integrity in their first draft. Which means their subsequent drafts are about optimization, rather than scrambling out of chaos.

This story model is out there, ready to reveal itself to you, in pretty much every published book or commercial film. Once you understand it you’ll see it in play, which will serve to confirm that, finally, you have something to write in context to, rather than the random genius of your inner storyteller.

This structural flow is simple and intuitive.

If you don’t like boxes and principles and anything that tries to tell you what to do — which is about half of you out there – take comfort in knowing that this works as a natural phenomenon. Like gravity, it doesn’t care what you call it.

It just is.

In my last post I talked about the three major plot twists in the structural paradigm — changes to your story — that will make it soar. The flow being discussed here is the narrative scenes that connects those three story moments.

Your story should unfold — in other words, this is the sequence of your story, in a generic/modeled context — in four phases.

It goes like this:

You SETUP your core story… you launch and then show your hero RESPONDING to (wandering around in) this new situation or quest or mission… then you show your hero mounting a PROACTIVE ATTACK on the problem, or assault on the mountain of opportunity… and then you create a path toward a final confrontation and RESOLUTION.

One flow. Four parts. Separated by those three major plot twists, where you insert the catalytic narrative information — a moment, really — required to move (shift) the context from one part to the next.

This IS classic three-part story structure, by the way, recast in more accessible terms. Because the “Act II” of that model is always taught in two parts, each with a different context, so it’s all actually four parts after all.

Now, this doesn’t mean you can’t have as many parts as you want in your novel. Have twelve “parts” if you want. It’s semantics in that context. What’s not semantics, though, is this: the CONTEXT of your story sequence, it’s flow, is these four parts: setup… response… attack… resolution.

Each scene within each of these four parts should be written in context to this higher contextual target: setup… response… attack… resolution.

Each of these four parts needs substance. Each has its own set of part-specific missions and goals, which is available grist if you’re up for it (all of which is discussed on this site, and in my writing books). At the very least, though, start with shooting for equal length for each of the four parts in this sequence, then adjust from there.

Here’s what happens if you don’t understand this.

You may – because you’re heard your story should open BIG – decide to show the whole core story, fully formed, very early. On page 1, even. If you do this, you’ve just confused a “hook” with the “first plot point,” and you’ve just taken all the wind out of your opportunity to setup the story properaly.

If you introduce your whole-cloth core story early, as a hook, you are not optimizing the inherent power of story structure. Someone down the road will give you feedback that will sound like this: I just couldn’t get into it… I didn’t really care about your hero… it was too confusing… the stakes were too thin — and all of it will be the direct result of this particular story choice on your part.

This is what happens when you let it dump out of your head without understanding these principles. Fine as a starting point, as a process, as a first swing at it… toxic as a final draft.

Now you know.

The complex, the formulaic, has been rendered simple and clear. If you doubt it, test it. Read a novel, see a movie. It’ll be there. Your non-writer friends won’t see it, and they won’t care about it.

But you need to. Go find it. In modern commercial storytelling, it’ll reveal itself nearly every time.

It’ll even be there in the work of the very same writing gurus who tell you to just ignore it and let it spill out of you any way it wants to. Which is an interesting thing to observe. What they were talking about was process all along… leading to this outcome.

Begin the journey of wrapping your head around it. Your stories will immediately — from day one, even from just reading this post and letting it sink in – be better for it.

Story Structure: What “going with the flow” Really Means is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Story Structure: What “going with the flow” Really Means appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 15, 2014

Story Structure for Dummies

A Ceiling-Cracking Epiphany for Newer and Unaware Writers

An Explanation of the Inevitable for Frustrated Practitioners

There was a time, a decade or so, when you couldn’t write a headline like that. Because it seems to say one of two things: if you don’t understand this then you’re a dummy… or… you know you’re not a dummy so you can skip this one.

Both of those are unfortunate misperceptions.

Thanks to the popular line of books that play off this title, we now understand that this means something entirely different. A “X for Dummies” book means you are about to encounter that which is by nature complex explained in simple (or simpler) and more accessible terms compared to the conventional wisdom of that topic.

Income Taxes for Dummies, for example. Doesn’t mean you’re not smart, it just means you haven’t been shown around a Form 1040 to the extent necessary to work with one on a professional level.

And so it is here. You seek to become a professional-level storyteller. This is what, at square one, you need to understand.

Make no mistake, story structure is a can worms.

In fact, it is something that can, at times, make all of us, even the best of us, feel like a dummy.

Structure is so complicated because it has so many moving parts, each with rationale and mission-driven contexts behind it, and it is challenging because it is less than completely precise. It’s not math, we’re looking beneath the narrative of a story to see how it works, rather than the specifics of what happens.

So much easier to suggest that we simply step up to the tee and take a swing, you can always hit out of the trees later.

To make this even fuzzier, there are credible writing teachers and guru-types out there that either teach it in an incomplete or imprecise way, or they don’t believe in it at all.

And yet, when you see it, you can’t unsee it.

And you will see it if you look for it.

You will find a clear and rather simplistic structural model within nearly every publishable novel that you read and every movie that you see.

One model. With many variable options. But nonetheless… one model.

Hear this, and hear it clearly: Story does NOT trump structure. Story IS structure.

The guy who wrote a book by that title is highly credible, but the title of that book is toxic. Because he’s talking about how you write, not what you end up writing — or need to end up writing — that becomes publishable. It’s a process thing, style thing, a preference thing… one that leads you to the same outcome as someone who begins the process with structure.

Structure is like bones within a human being… you can preach muscle building and blood pressure and emotional health all you want, because they are important to the building of a whole healthy person, but at the end of the day it’s all hanging on a skeleton. There’s no life at all until that structural base is covered.

That debate is for another post… but at the end of the day it’s not a debate at all.

When your story works – however you got there – it will be, to a great extent, because you nailed the structure. And – here’s what newer writers don’t get – it will be a structure that is waiting for you to find it, a universal story model, rather than something you believe you made up on your own, following the organic demands of the story you are telling.

That’s what happens when you write drafts.

You add pace, increase dramatic tension, build intrigue, demonstrate character within time and place, polish the edges. When those things don’t work as well as they should, you change it up and write another draft. And guess what – that draft will take you closer to the very structural model that has been there waiting all along.

Because the truth is, the proven universal fact of it is, stories work better that way. Exceptions – not in process, but in outcome – are very difficult to find in modern commercial storytelling.

So if you want to play in that game, this stuff is something you need to understand.

Allow me to boil it down into something excruciatingly simple.

If you only get this much, without knowing or caring about what’s behind these three little bullets, you will have crossed over into another realm as a storyteller. You may, in fact, be able to instinctively construct a novel that works, on this alone.

Because this is what professional story tellers know. No matter how they write, whatever their process, this is where their stories end up.

Here is it:

Your story needs to have at least three major twists — plot twists, or major character arc moments — in its linear structure.

There are names for all three, and entire chapters of illumination explaining all three of them. Let’s skip that. This is the 101 – you need to change the direction of your story, you need to twist it, a minimum of three times for it to work in an optimally effective manner.

Can you have more than three plot twists? Absolutely. Have as many as you want. The Davinci Code, for example, has dozens of plot twists. As do most mysteries and thrillers, even romances. But all of those twists either lead to, or respond to, one of these three major story pillars, which appear at roughly the same spot in any story.

That’s the one — the target placement — the cynics get all sweaty about. But fact is, when you grab any successful story off the shelf, it’ll be there. They will be right there, in those three spots. Donna Tart did in her Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Goldfinch. Gillian Flynn did it in Gone Girl, and all of her other novels. Michael Connelly and David Baldacci and Nora Roberts – name your hero – do it in all of their stories.

Are you doing it? This is a wake-up call if you’re not.

Three major story-shifting plot twists. At roughly the same specific places in a story. That’s the difference between a newbie, an amateur, a dreamer… and someone with one foot through the door marked PROFESSIONAL.

The First Plot Twist

Welcome to the most important moment in a story. Allow me use an analogy to introduce it to you.

A flight on an airliner begins with the take-off, right? You would think so, at a glance. But so much needs to happen before the wheels safely leave the runway. If those things don’t happen, the airplane and the people in it may not survive the journey.

You need a flight plan. A destination. An understanding of the weather to be encountered. An awareness of other airplanes along the route. A level of skill on the part of the people flying it. Someone guiding you through the clouds. You need to put fuel in the tanks. You need to be sure all the moving parts of the machine are in working order.

All that, before the journey begins.

So it is with your story. Hopefully the airliner isn’t dealing with a drama before takeoff, but your story needs to.

Your story is ultimately about (but not yet, that’s the point here) a hero’s journey: the pursuit of a goal or a need or an opportunity (often – usually in fact – resulting in something that must be solved, avoided, treated, discovered or otherwise defeated). That’s when the story begins. It’s when the story’s wheels leave the runway.

And as it is within the analogy, so much needs to happen before that moment arrives.

Prior to that moment – the most important moment in your story – you need to setup the launch of that hero’s new path. You introduce the hero doing something else before the specific story itself plops into their lap. We see what will be at stake when it does. We see who and what might be a problem down the road (like, if the story is about a disease, we see symptoms here, before a diagnosis hits the page). We sense the seeds of backstory that may become problematic.

Some writers like to open big, with something massively dramatic and relevant. So be it – that’s called a hook. But be clear,this is not a First Plot Point. Because a properly rendered hook does not launch the full core story, though it may indeed launch it in a preliminary way, or simply preview it, in that case with something new happening later at the FPP, which is the major twist that fully puts the dramatic proposition into play.

Newbies confuse the hook and the First Plot Point. Now you know. They are very different things.

With all this setup narrative in place, then you lower the story-problem onto the shoulders of your hero. Something happens that changes – twists – the story, which until now has been about something else, something prior to and even disconnected to the story you are now telling.

Like, for example, a story about someone winning the lottery. The core dramatic story begins when the hero does, in fact, win the lottery. All kinds of new pressures and opportunities appear. But the story works better – it works best – when the reader comes to know the character and understand how and why winning the lottery matters – indeed, why the hero bought a ticket in the first place – before the winning numbers are announced. So when it happens, we feel something. We empathize.

This first twist is called The First Plot Point. It is the most important moment in a story.

You’ll see this in virtually every story you encounter, in some recognizable form. Test it, tonight in fact – rent a movie, and notice how the core dramatic story fully manifests about 20 or so minutes in. Prior to that we met the hero, we observed the world she/he lives in, see things that may come into play later, we sense the stakes being built… all prior to the story-bomb going off.

I saw “The Theory of Everything” yesterday. Great story. Do you think it opens with Stephen Hawking in a wheelchair? Of course not. We get 20 minutes of setup first… coming to know and like him as a fully functional, healthy young genius, chasing his dream, falling in love… and, with the seemingly inconsequential moment or two when his hands shake or he moves awkwardly. We come to care about him as this builds toward – sets-up – something.

The First Plot Point happens when he takes his first fall, a horrific face plant, resulting in his ALS diagnosis. Which IS the core story – his journey in dealing with that disease. It launches at the First Plot Point.

Every time. Test it.

Are you doing that in your story? If not, then you’re operating outside of the expectations of a professionally-structured story.

Have you seen the film or read the book Gone Girl? (Spoilers ahead.) The news that the wife is missing hits the story on Page 5. A hook. Easily misunderstood by the newer writer as the first major story twist. No, it is indeed “a” plot twist, but it is only an inciting incident (rather major, but that isn’t the point – it is an element of the setup only), rather than the first plot point itself. Those who would argue otherwise are dealing with semantics.

The First Plot Point occurs later, at about the 25th percentile mark, when the wife confesses in her diary that she believes her husband may try to kill her. Now, in that moment, it’s on.

It changes everything. It actually fully launches the core story of the novel. Everything prior to this has been a setup for it. The reader/viewer has been sucked in, completely fooled. This facade continues until later (at the second major plot twist), but the core dramatic story is now fully in play, in a way it wasn’t a page/minute earlier.

The Second Plot Twist

This one is easy to nail, and perhaps the most intuitive plot twist of all. It takes place as close to the exact middle of your story as possible. It is when what we thought was going on shifts somehow. It either changes or is illuminated to an extent it alters the hero’s path going forward.

Look for this, it’s in every story that works. Is it in yours? It needs to be.

In Gone Girl, it is when the point of view switches to that of the missing wife, via her diary entries. Suddenly we learn about her plans and the means of her deception… something we weren’t even sure was a deception. Until now. Everything changes. It occurs at the 52nd percentile mark in the novel, at at the exact middle of the movie.

Not a coincidence, by the way.

Everything changes.

But notice the hero hasn’t remotely solved the problem or won the day at this point. No, you save that until the end. This midpoint change is there to cause the hero to take new and/or stronger action, to shift from a response mode into a more proactive attack mode in confronting whatever has been in her/his way.

Notice that in the scenes after this midpoint, this is precisely what happens – the husband goes to war against the implication that he has killed his wife.

The Third Plot Twist

Simply put, you need to change things up in a major way at least one more time… and at a specific time within the narrative: roughly the three-quarter mark. It’s called The Second Plot Point, and how it looks depends on the nature and direction of what has been in play prior to that moment.

Suffice it to say, though, that this twist (new story information) opens the final floodgates of an inevitable confrontation between the hero and whatever blocks her/his path. It’s usually unexpected, or it may have been there all along but now, through new information or revelation, is suddenly rendered meaningful. You get to say what it is… as long as it adds tension and noticeably accelerates the pace toward a final confrontation, climax and resolution.

In Gone Girl the midpoint twist is incredibly easy to spot. The wife slits the throat of her lover, which allows her to return to her old life with a credible story, one that will paint her as a hero courageously emerging from a victim scenario (and thus explaining her absence, while vindicating her husband), and entrap her husband into a devil’s-deal pact.

It is really that simple?

Well, no. But it’s really the first thing you see, or should see, when you observe a story that works, and then, when you set out to write one. It’s the 101 of story structure, and if you never get your head wrapped around it, all the artful character and thematic chops and on the planet won’t fully serve you.

These three plot twists are the weight-bearing foundations that support the entire story itself. It is the engine of dramatic plot and the fuel for character development.

They are always there. Structure doesn’t care what you call it, doesn’t care that you believe you are discovering it for yourself as you feel your way through a story… it awaits as the final form of pretty much every modern commercial story that works.

Again, stories are like taxes in that regard. Go ahead, get creative. But mess with the tax laws and there will be consequences.

This doesn’t mean you were a dummy if you didn’t know this. It is surprising – shocking, actually – how seldom, and how confusingly this basic truth about storytelling is covered within the public writing conversation.

Be confused no more. Everything else in your story stems from this square one inevitability – your story will work better – best – when you twist it three times, at those three target locations. From there the playing field widens to allow virtually anything and everything you’d like to throw into your story.

****

Want more depth on this? Use the Search function here on Storyfix, there are dozens of posts on structure, plot points and story architecture. Or, consider my writing books, Story Engineering and Story Physics, both of which go deep into the powerful impact and technical demands of these essential story elements.

Story Structure for Dummies is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Story Structure for Dummies appeared first on Storyfix.com.

November 6, 2014

Writing Successful Fiction: When What You Don’t Know Trumps What You Do Know

A tale of mishandled craft sinking the story ship.

Quick story from the writing conference front.

A few weeks ago I was doing a couple of workshops at a major writing conference, and as is often the case at these gatherings, the spare hours between sessions were spent meeting one-on-one with writers to go over their projects. This is always a scheduled coaching session, not just a happenstance pitch in front of the elevators… which also happens, but without the feedback.

I could write for days about how the principles of story architecture – or the lack thereof – becomes a glaring issue in the novels these writers are working on. For the most part they’re totally publishable renderers of compelling prose, so that’s rarely the problem. (As I’ve written here and in my books, don’t get too excited about your way with words, that’s just a commodity ante-in to the game… the agents taking pitches at these things are looking for the next great story, not the next great wordsmith).

One fellow’s novel stood out as a case study in what can go wrong.

It should be said that everything about this guy’s story – including his sentence-smithing skill – was absolutely fantastic. The story had it all, including a really compelling conceptual landscape. I was excited, because at a glance it had a real shot.

But when we popped open the hood to see how the thing was built, the wheels started to come off.

I asked him about his opening hook.

His response was that he’d opened the story with some deep backstory of the hero. I asked if it would link directly to the forthcoming plot of the core story, and he said no, he just wanted to add characterization before putting the hero in harm’s way.

Strike one. Because a thriller needs a killer hook, every time.

Also, a thriller is not a character-driven vehicle, but rather, a conceptually driven narrative, one with a compelling character chasing a specific goal, against specific exterior antagonism. Which means the hero’s crappy childhood is not a primary story variable.

Opening with backstory – unless it is a prologue with a direct plot connection that later becomes poignant, clear and perhaps ironic – is rarely a good idea.

But I didn’t tell him that… yet.

I wanted to see how badly he’d mangled other principles of dramatic structure before I got specific about what it should look like.

That’s when I asked the deal-breaking question: “So when in your story do you put your hero in harm’s way?”

He quickly answered, “When he gets his assignment to find the guy with the stolen bomb.”

I was already shaking my head. That’d certainly do the trick, but it wasn’t at all what I’d asked for. I had asked, literally: when, within the linear sequence of the story, does this moment occur?

A blank stare ensued.

So I explained, again: the hero needs to seek something in a story, have a need or a mission to engage with, to take action toward, with something at stake and significant obstacles – a villain – in his/her way.

You know, the 101-level most critical thing that makes a story work.

“Oh sure,” he said, momentarily relieved. “It has that. Like I said, it’s when he gets his assignment. That’s when all hell breaks loose.”

I was nodding, but not in agreement.

“So when does it happen? I asked you about the hook, and it seems that’s not it. So when? Give me a percentage based on total length.”

Mind you, this was a thriller he was writing. Not a literary novel. Not that it changes the answer… the best answer is the same for any genre.

He had to think a moment. Then his eyes suddenly lit up.

“It happens just short of the halfway mark. Maybe, like, forty-five percent in.”

I think he heard me gasp.

Or maybe that was the sound of his story going of the rails.

I shook my head. Then I asked what his hero was doing in those first 160 to 200 pages of the manuscript, before the boom was lowered.

He said, with some amount of confidence, that he was building up the character, showing us his life before he became a professional in the black ops business, adding a lot more backstory. Mostly backstory.

He said this as if he thought it was a good thing.

I asked why he thought the reader would need, or be interested in, all this backstory exposition.

His expression was as if I’d just asked him if his mother looked good with no clothes on.

Because, he explained with the very antithesis of confidence now, that this is what stories do, or at least that’s what he’d been taught they should do. Introduce your hero, show the reader what he does, who he is, position him, create a setting, make us like him, or at least relate to him, and…

I was still shaking my head. Must have been, because his voice simply tailed off into silence.

That’s when I told him I thought he needed a major revision before it would work.

“How can you know that?” he asked. “You haven’t read it yet.”

I get asked that a lot. It’s always the wrong question.

“That’s true,” I replied, “I haven’t read it. I don’t need to read it. Let me ask you this – did you understand my question about when you begin the hero’s core story quest? The actual plot itself? And was your answer accurate?”

He assured me that he did, and that it was.

And then I told him the ugly, deal-breaking truth:

He’d just violated one of the key principles of fiction: your setup simply cannot take that long. That the optimal place to turn the corner from setup, via something massively significant happening, toward the path that the hero would embark upon in the story, was closer to the twenty percent mark, give or take.

That when it happens, I told him, its called The First Plot Point, and it’s arguably the most important moment in a story – especially a thriller.

He thought a moment, then I saw a light in his eyes.

He said, “Okay, then. I’ve got it. I’ll open with it. Make it a hook.”

Still shaking my head.

While there may eventually be a way to make that work, simply moving the First Plot Point into hook position wasn’t it. The principles of story architecture demand more finesse than that, that the entire reasons for using those principles – so the forces of story, what I call story physics – have a chance to work their magic on the reader in the best possible way.

I explained that, while his story sounded thrilling, he had made a fatal error in waiting that long to pull the trigger on the dramatic core of it all. Because readers are waiting for that moment, and they’ll get impatient if you make them wait nearly half the book to get to it.

“I didn’t know that,” he said. “But it makes mad sense when you say it like that.”

“Mad sense. I kinda like that. That’s exactly right. That’s what the principles of story architecture are… mad sense. Without the madness.”

I suggested that he dig into this to understand these principles, and pointed to the copy of my writing book – one of two – that happened to be on the table next to us. And when he does, I added, he should test it out there in the real world, look for these principles in play within the books he reads and the movies he sees. Especially thrillers.

Seeing it is to believe it. It’s the best way to learn it.

“So other genres don’t follow this stuff?”

“On the contrary, all the genres follow it. It’s just that in thrillers its usually easier to see. Like, neon flashing graphics kind of easy.”

We discussed this with as much depth as the remaining five minutes would allow, and I sent him away with what seemed like a sense of purpose and, in his words, much gratitude for setting him straight.

He asked me to wish him luck with his agent pitches.

I smiled, forcing a smile, knowing he would need it.

But the story has an epilogue.

Next day I ran into him, this time in front of those elevators. I asked about those pitches. And he was excited to answer.

“Went great! Two agents want a synopsis. I guess they didn’t agree with you.”

Behold, the great head-scratching paradox of confusion on the part of the over-confident, under-enlightened writer. Which comprises a massive percentage of the manuscripts submitted to agents and editors.

Writers who don’t yet know what they don’t know.

Now I was nodding. Not in humble contrition, but with sad certainty. Because if he had written that novel as he described, he was in for a dark journey of frustration.

I asked if he’d told the agents how long his story setup was, how long it took to get to the point in the story where the hero’s core dramatic journey – the quest – came into play.

“No,” he said. “They didn’t ask about that stuff. They just liked the sound of it.”

They never ask about this stuff. That’s the problem. They just reject it when it doesn’t work.

And it doesn’t work if you manhandled the principles.

“Are you going to revise the draft before submitting?” I tossed out as the elevator doors opened.

“Naw. They want pages right away. We’ll see what happens.”

He smiled, as writers often do when they mistake the uncompleted conversation for the one that affirms their limited skill set.

I wished him luck. Then waited for the next elevator to arrive, even though the one he entered had been otherwise empty.

And so, we switch into teaching mode here.

This is what happens. This is where rejection comes from.

We don’t know what we don’t know. And thus, what we don’t know squashes our dreams.

Story architecture is very much like anything in life that lives or dies by how functional it is. An engine, a first date, your computer… one thousand moving parts can be perfectly tuned and positioned and connected and humming along, but if one single essential thing is off the mark, if it sputters at all, the whole thing will crash and burn.

And the event will be fatal.

Knowing the broad strokes of how a story seems to be constructed isn’t enough. And while you may have heard it before and dismissed it as just one presenter’s opinion – when what we hear contradicts what we have, that’s usually the outcome – it is just as likely that you’ve heard it and haven’t yet fully grasped it.

You need to know what makes a story engine work.

One bad spark plug and the whole thing won’t start, it will remain stillborn. Or it will sputter and die.

Or in the case of those agents, it will be rejected.

If you’re under contract, you’ll be asked to fix it. But if landing an agent or getting a deal is the goal, it’s an all-or-nothing proposition. Rejection will be the outcome. Makes no difference that they liked the Big Picture of your story in your pitch. You have to perform over the arc of 400 or so pages. All of it.

You have to get it right, all of it, every time.

You have to know what a core story arc is – what your core story arc is – what a hook is, what a setup quartile is, what a first plot point is, and a few dozen other elements and milestones and story beats and criteria, both plot or character – before has a real shot at working.

At least, working as well as it needs to work in the heat of competition among writers with equally cool story ideas and wonderful prose, just like you, and who are nursing dreams as lofty and urgent as your own.

And then… your version of right needs to glow in the dark.

Which is a function of story theory and story architecture elevated to a fresh, energized, call -the-publisher-now level, via your craft and the inherent conceptually-driven premise upon which you build that story.

Didn’t know that?

You need to. Not knowing will kill you, every time.

****

Want more story fundamentals? They’re waiting for your discovery in by two writing books, “Story Engineering” and “Story Physics.”

If you’d like to see how your story plan compares to professional standards relative to story architecture and conceptual power, click HERE and HERE to learn more.

Writing Successful Fiction: When What You Don’t Know Trumps What You Do Know is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Writing Successful Fiction: When What You Don’t Know Trumps What You Do Know appeared first on Storyfix.com.

October 29, 2014

There’s Power in the Public Domain — A Guest Post by Art Holcomb

Stuck for an idea to develop?

As a writer, I’m constantly looking for new approaches and new ideas to write about. I’m guessing you do the same.

In recent years, there have been a number of books that have been written about characters developed by writers in the past – such as Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hide and others that are available for any writer today to use and spin off because they are in the Public Domain.

My friend Peter Clines wrote a great twisted novel entitled The Eerie Adventures of the Lycanthrope Robinson Crusoe and parodies like Sense and Sensibilities and Zombies received such critical acclaim that they have been in development as motion pictures.

Works in the public domain are those whose intellectual property rights have expired, have been forfeited, or are inapplicable. That means that any writer can continue to tell the tales of the characters – by writing prequels or sequels to existing stories, adaptations and continuing adventures, or develop entirely new approaches using these characters – without paying for the privilege or worrying about copyright issues. Not only is this a great writing exercise, but it can also be very profitable if you can match your skills with a character the public is still interested in.

Below is just a small list of famous writers and their stories that are in the public domain.

Take a look and see if there’s anything that suits your fancy. If interested in learning more about how to spin off public domain stories and the different approaches you can take to develop these characters, drop me a line in the Comment section here and I’ll develop the concept in a future post.

One other thought: if you write a novel inspired by or a screenplay adaptation of these works, be sure to make your source the lead when you pitch your story to an agent. Nothing says credibility like a little Literature, with a capital “L.”

Have fun!

Horatio Alger: Novelist famous for his rags-to-riches stories. All of his work is in the public domain. Famous stories include The Store Boy and Ragged Dick.

Hans Christian Anderson: All of this famous Dane’s works are in the public domain. Famous stories include Thumbelina, The Ugly Duckling, The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Clothes, and The Princess and the Pea.

Jane Austen: She has become one of the go-to storytellers in Hollywood in recent years. Well-known novels include Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion.

Honore de Balzac: Famous stories include The Girl With the Golden Eyes and Father Goriot.

Charlotte Bronte: All of her work is in the public domain including her most famous novel Jane Eyre.

Emily Bronte: Just like her sister, all of her work is in the public domain. Her only novel is the oft-filmed Wuthering Heights.

Frances Hodgson Burnett: Best known for the children’s stories The Secret Garden and A Little Princess. All of her works are in the public domain.

Edgar Rice Burroughs: Creator and author of Tarzan of the Apes. Only some of his work is in the public domain including the original Tarzan of the Apes and At the Earth’s Core. Be sure to check the availability of his other stories before considering using his other works.

Lewis Carroll: Famous mathematician and author whose works include Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through The Looking Glass and The Hunting Of The Snark. All of his work is in the public domain.

James Fenimore Cooper: His more famous tales include The Last of the Mohicans and The Deerslayer.

Daniel Defoe: All of his works are in the public domain. His most well-known stories are Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders.

Charles Dickens: All of Dickens’s work is in the public domain. Famous stories include A Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, A Tale of Two Cities, David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: Most, but not all, of his works are in the public domain. The later Sherlock Holmes stories may not yet fall under the public domain but all of his stories before 1923 have including many involving his most famous creation Sherlock Holmes. Other well-known stories include The Poison Belt and The Lost World.

Fyodor Dostoevsky: All of his works are in the public domain including Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: All of this German writer’s works are in the public domain. His most famous works include The Sorrows of Young Werther and Faust.

Brothers Grimm: Two German brothers who were famous collectors of fairy tales. Their versions of the famous fairy tales are all in the public domain including such cherished gems as Cinderella, Rapunzel, Snow White, Hansel and Gretel, and Little Red Riding Hood.

Nathaniel Hawthorne: All of his writings are in the public domain so go ahead and try to write a new version of The Scarlet Letter or The House of the Seven Gables. Stories like these work great when set in more modern times with hip and sophisticated contemporary characters.

Homer: Not Simpson, but the Greek guy who wrote the epic poems , The Odyssey and The Iliad, both of which are in the public domain.

James Joyce: You can based your novel on some of Joyce’s well-known works like Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Franz Kafka: This unique writer has a few stories that have fallen in the public domain. The most famous being The Metamorphosis.

Rudyard Kipling: Some, but not all, of Kipling’s work is in the public domain including The Jungle Book.

Jack London: All of this great American writer’s body of work is in the public domain. His most famous stories include The Call of the Wild and White Fang.

H. P. Lovecraft: All of this bizarre horror writer’s work before 1923 is in the public domain.

Herman Melville: All of this author’s work is in the public domain. His most famous story is the required reading for high school students: Moby Dick. A thought — ever wonder where Jaws came from? Just sayin’.

Edgar Allan Poe: Filmmaker Roger Corman has exploited much of Poe’s work and you can too. All of this macabre author’s work is in the public domain. His more famous works include The Raven, Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Mask of Red Death, The Fall of the House of Usher, The Black Cat, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Tell-Tale Heart.

Rudolf Erich Raspe: All of his works are in the public domain including his most famous story The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen.

William Shakespeare: Old Bill has been dead for a long time; hence, all of his work is in the public domain. Try your own take on Hamlet, Macbeth or Romeo and Juliet.

Mary Shelley: All of her writing is in the public domain including Frankenstein. Her other famous books include The Last Man and Matilda.

Robert Louis Stevenson: All of this writer’s work is in the public domain including the popular stories Treasure Island, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, Kidnapped, and New Arabian Nights.

Bram Stoker: All of this writer’s work is in the public domain including Dracula, The Jewel of Seven Stars, The Lady of the Shroud and The Lair of the White Worm.

Mark Twain: All of this great writer’s works are in the public domain. His most famous stories are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Jules Verne: All of this entertaining French writer’s work is in the public domain. His most famous works include Journey to the Centre of the Earth, From the Earth to the Moon, 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, The Mysterious Island and Around the World in Eighty Days.

H.G. Wells: Only some of Wells’s stories are in the public domain but they include The Invisible Man, The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau and The War of the Worlds. Most of the great modern time travel stories, both books and films, owe a nod of thanks to this author.

Oscar Wilde: All of this great playwright’s work is in the public domain. His most famous stories are The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest.

Johann David Wyss: This writer’s most famous story The Swiss Family Robinson is in the public domain.

*****

Art Holcomb is a screenwriter and comic book creator. His most recent comic book property is THE AMBASSADOR and his most recent project for TV is entitled THE STREWN. His new writing book is tentatively entitled “SAVE YOUR STORY: How to Resurrect Your Abandoned Story and Get It Written NOW!” (Release TBA.)

Larry’s add to Art’s bio: when he’s not on set doing rewrite work or chasing a deadline for a studio script assignment, he’s also a major screenwriting teacher at the University level, a story development coach and a sought-after workshop facilitator at writing conferences around the world.

There’s Power in the Public Domain — A Guest Post by Art Holcomb is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post There’s Power in the Public Domain — A Guest Post by Art Holcomb appeared first on Storyfix.com.

October 15, 2014

Getting Published: The Genre-Concept Connection

Somewhere deep within the genealogical family tree that illuminates the origins of the word genre, we find another word that confuses the whole issue: generic.

And that’s the problem. Your genre-based story can easily become generic – it simply becomes another face is a crowded sea of stories – rather than standing out.

This very thing, stated that way, explains a vast percentage of why stories within any given genre are rejected. They are simply good… when they need to be great. And greatness relies on a powerful concept driving the whole thing.

What will make it stand out is your concept.

Which is nothing other than the presence of something CONCEPTUAL about the story landscape and framework upon which — and within which – you define and execute your premise.

Example: “The Help,” the novel (and subsequent film) by Katherine Stockett. The premise (young woman tries to launch her journalism career by writing a book about the experiences of the domestic workers in her community) isn’t all that fresh and compelling until you place it within a conceptual framework: the whole thing goes down in 1962 Jackson, Mississippi, where racial bias defines the cultural values of the era and place.

(Click HERE to learn more about the critical differences between concept and premise.)

Most workshops, even when they are genre-specific, show us what to do, how to do it, and why. Few show us what can go wrong.

And yet, it is precisely that – what goes wrong – that derails stories and keeps budding careers locked in a holding pen.

I have read over 600 story plans in the past three years, including some from published writers.

The verdict is in: something usually goes wrong.

There is a reason that perfectly good, solidly executed stories get rejected. That reason often has a lot to do with the lack of something conceptual being offered at the heart of the story.

This is even more true, more often, when the genre itself – romance and mystery in particular – seem to defy the application of what might be construed as “high concept.”

Using that reading experience as a database – meaning, I’ve discovered this for myself, rather than read about it elsewhere — I’ve come to some empowering conclusion.

I’m quite clear on what actually does go wrong.

It’s an equal opportunity story killer, and because it has to do with our creative sensibilities, rather than our technical skills, it’s tough to teach, tougher to learn, and always a moving target.

When was the last time you went to a writing workshop or conference and came away with the realization that your story idea (concept, premise, plot, exposition) just isn’t good enough. Nobody tells you that. They leave it up to you to decide what works and what doesn’t. As if… anything can be made to work.

It can’t. Not when it is void, at its very core, of something compelling.

And so, a throng of writers go away and write the hell out of a perfectly mediocre or lame story idea. Because nobody told them to look right there – at the concept and the premise that springs from it – for the broken parts.

Right there is where many stories go wrong.

Apropos to today’s title… more than half the time it has to do with the writer’s choice of concept. Or worse, the complete lack of one.

And/or, the concept or lack thereof doesn’t match up with the conceptual demands of the genre.

A thriller must have thrills. Periods. The tragic childhood of the hero you are asking to thwart a threat… that’s not thrilling. If you put your eggs in that basket — if you try to write a “literary novel” within a genre that requires the presence of something conceptual, then you are in for a dark surprise down the road.

That hardly ever works. Your best shot in this case may be complete mediocrity.

What does work:

Mediocrity arises from one of two arenas (yes, sometimes both… that’s an even darker picture; that said, when the first goes south, odds are the other is at risk, as well):

- The nature of the concept and premise itself;

- The technical, structural expositional skill with which that concept/premise is rendered.

You can write the hell out of a vanilla idea… and it is still vanilla.

What makes an idea triple chocolate thunder is the concept underlying your dramatic premise.

In other words, the empowering context of something conceptual.

Enlightenment awaits at the intersection of concept and genre.

This perspective dawned on me this past weekend as I conducted a workshop with a roomful of eager-to-learn, highly educated and skilled romance authors. I’ve discovered that romance writers are a unique lot… they actually understand more about “story” than a lot of other genre-specific authors, perhaps because there are so many sub-genres within the romance paradigm.

Here, in a nutshell, is what became crystal clear:

Concept, and the way it is applied and becomes empowering, is different from genre to genre. Especially when it comes to romance.

Where other genres thrive on big loud conceptual elements, romance thrives on nuance and ambiance.

The optimal target and criteria for concept – the essence of it – is uniquely constrained for romance authors who are writing clean, traditional, classic two-people-meet-and-fall-in-love-after-jumping-through-hoops romance. The Debbie Macomber flavor of real-people-in-real-life-situations romance.

Soft fuzzy warm stories of love.

One of those writers nailed me on this. While sub-genres or romance are indeed subject to a higher conceptual bar as much their non-romance counterparts – thriller, mystery, paranormal, historical, speculative, time travel, etc. Those genres and romantic sub-genres do fall in line with the more-is-better essence of the highest/best form of concept… and thus, the water muddies for the traditional romance writer.

Here, paraphrased, is what she said:

“What if I don’t want a superhero, or the world isn’t ending. What if nobody in my novel reads minds and nobody gets killed and there are no cops and no one is investigating anything at all? That’s the romance I read, real people in real life, that’s the romance I write. So what about that? How do I make THAT more conceptual, which is what I hear you trying to sell us?”

A good point, that.

And yet, there is an answer. That real-life-real-people novel she’s writing… it’ll likely tank – disappear into the crowd – if there isn’t something conceptual, even in the most subtle way, something appropriate to her genre, at work behind the premise itself.

A love story… standing alone as a concept, that’s not highly conceptual. It needs… something.

A love story between people who work in the The White House, or who are being audited by the IRS, or who bring different and conflicting religions to the deal, or who are actually cousins… where one party is dealing with amnesia or a disease (i.e., “The Fault in Our Stars”)… something… any love story will be fresher and more compelling when there is something conceptual about the story arena/landscape.

When asked what was conceptual in her story, there was no answer. And thus, the opportunity is exposed.

You could frame the challenge this way: what about your romance novel is fresh and original, will make it stand out in a crowd, will get the attention of an agent… apart from your stellar writing voice and structural execution?

If you can’t answer that, then opportunity awaits in the conceptual realm.

Concept applies to all genres… just not equally so.

Here’s the truth that sets both ends of that spectrum free: your concept needs to align with and then optimize the conceptual demands of your chosen genre.

Different genres require different levels of, of forms of, something conceptual. The more genre-specific it is — thriller, suspense, paranormal, etc. — the more effective a higher concept will be.

Understanding this implies you know a lot about a lot of things. So lets look at some quick examples.

- In the mystery genre, you need to solve a crime that has something conceptual about it. Not just a generic murder, a generic detective, in a non-descript setting. A higher concept will make your story stand out and fuel a higher level of story physics across the entire narrative arc. Like, the victim was a hooker with a client list that includes powerful politicians. Like, the detective has been barred from the case because the victim was his ex-wife. Like, the murder happened in November of 1963 in Dallas, when everyone was looking elsewhere. Something that is conceptual.

Not just who killed your uncle?

- In the thriller genre, you need something conceptual that poses a threat that delivers the thrills. A massive, unprecedented tsunami. A pandemic disease. A terrorist with a new angle. An extortionist targeting her own wealthy family. Something that is conceptual.

Not just will the team win the game?

- In the suspense genre, including romantic suspense (which tends to mash mystery and thriller together within the tropes of romance) the suspense needs to be mysterious and thrilling. A lover with a secret life, or a game changing past. A hitwoman falling for her mark. A woman who bets everything on a man who isn’t what he seems. Something that is conceptual.

Not just will they end up together after all?

- In the paranormal genre… well, this one is obvious. Vampires, with a twist. Ghosts, with a twist. Mind readers and shape shifters, with a twist. Both are conceptual – the paranormal thing, and the twist you put on it. No twist, no real concept in play. Something that is conceptual.

Not just a look at the childhood of a girl who can read minds.

Notice how all of these examples, when they work, are not about otherwise unremarkable people involved with unremarkable real life romantic aspirations. Which begs the question: what IS remarkable about your story, on a conceptual level?

These genres demand something fresh, edgy and compelling, a notion or proposition or arena/landscape that frames a story with whatever the genre itself demands: mystery, thrills, eroticism, adventure, a massively urgent problem, etc. None of it can be simply a take on real life… at least if you want it to rise above the crowd.