Joshua Silverman's Blog, page 6

March 30, 2013

Happy Easter or Astarte?

It is widely known that many Christian traditions and holidays were modified forms of pagan festivals. In 313 CE, Constantine the Great (you know, the Roman Emperor who converted and turned the Western world Christian overnight), declared the official religion of the Roman Empire as Christianity. To smooth this idea over with the public and assist with the conversion process, he tied many Christian holidays to pagan ones which the public already celebrated. He didn’t want a revolt on his hands. (Although it’s an oversimplification, just imagine if the President of the United States declared the official religion of the United States wasn’t Judaism or Christianity. That is essentially what Constantine did in 313 CE.).

But, if we know that most holidays have their roots in ancient cultures, where does Easter come from? By using symbology and finding the common threads throughout the ancient world’s religions, we can understand why we celebrate our holidays the way we do.

Let’s start with something simple, the Easter bunny. Ancient Egyptians believed that the divine spark was in every creature, everything we can see, hear, smell, taste and touch. And, they associated gods to creatures, which is why Thoth is depicted with the head of an ibis, Horus the head of a falcon, Bastet the head of a cat, Sekhmet the head of a lion and so on. Yet, although she was not one of the most popular goddesses, the goddess Unut, also called Wenet (The Swift One)or (the Lady of Unu), was depicted as a woman with the head of a hare.

“The hare, the symbol of fertility in ancient Egypt, a symbol that was kept later in Europe…Its place has been taken by the Easter rabbit.” (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1991 ed., Vol. 4, p. 333).

As a symbol of fertility, the ancient Egyptians thought of the new moon and new season spring brings after cold, harsh winters. Because Easter is determined by the new moon on a lunar calendar (the same calendar ancient Egyptians used), the hare was connected to the resurrection of Osiris.

Lest we forget the resurrection myth, Osiris was murdered by his brother, Seth. As I’ll do many other blog posts on the Osiris myth, a paraphrased version is this. Seth dismembers Osiris’ body in fourteen different pieces. Isis, goddess of magic and the moon, is Osiris’ lover and reassembles his body. With the help of Thoth, the god of wisdom and magic, Isis makes love to Osiris to bring him back to life. Out of their communion, the son of god (Horus, the child), grows up and takes revenge on Seth for the murder of his father.

Ancient Egyptians always identified themselves with Osiris, for they too wanted to be resurrected and live in his glory. That is why, during the new spring, they celebrated his resurrection.

Now that we can see the connection between the hare and the celebration of a god’s resurrection, let us turn to the second most iconic symbol of Easter, the Easter egg.

“The origin of the Easter egg is based on the fertility lore of the Indo-European races…The egg to them was a symbol of spring…In Christian times the egg had bestowed upon it a religious interpretation, becoming a symbol of the rock tomb out of which Christ emerged to the new life of His resurrection.” (Francis X. Weiser, Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs, p. 233).

From Egyptian Belief and Modern Thought, James Bonwick, pp. 211-212: “Eggs were hung up in the Egyptian temples. Bunsen calls attention to the mundane egg, the emblem of generative life, proceeding from the mouth of the great god of Egypt. The mystic egg of Babylon, hatching the Venus Ishtar, fell from heaven to the Euphrates. Dyed eggs were sacred Easter offerings in Egypt, as they are still in China and Europe. Easter, or spring, was the season of birth, terrestrial and celestial.”

Although almost every culture in the modern world has a tradition of coloring eggs, since the Roman world wasn’t established until around 300 BCE, and we know that Egyptians influenced ancient Greece, who in turn influenced ancient Rome, we can infer that Ancient Egyptians were coloring eggs three thousand years before Rome existed.

The Name of Easter.

Will Durant, in his famous and respected work, Story of Civilization, pp. 235, 244-245, writes, “Ishtar [Astarte to the Greeks, Ashtoreth to the Jews], interests us not only as analogue of the Egyptian Isis and prototype of the Grecian Aphrodite and the Roman Venus, but as the formal beneficiary of one of the strangest of Babylonian customs…” The rest of the quote is unimportant as it has to do with the custom of virginity. What is important is the linkage between Venus, Aphrodite, Isis, and Astarte.

Astarte was the Queen of Heaven in ancient Middle East. Links can be traced to Assyrian, Sumerian, Phoenician, and Egyptian origins. Nevertheless, her worship was associated with the sun. It is widely believed that the name EASTER is a Greek and Latinized derivative of the original pronunciation of Astarte.

“The term Easter was derived from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Eostre’, the name of the goddess of spring. In her honor sacrifices were offered at the time of the vernal equinox. By the 8th century the term came to be applied to the anniversary of Christ’s resurrection.” (International Standard Bible Encyclopedia edited by Geoffrey Bromiley, Vol. 2 of 4, p.6, article: Easter).

“What means the term Easter itself? It is not a Christian name. It bears its Chaldean origin on its very forehead. Easter is nothing else than Astarte, one of the titles of Beltis, the queen of heaven…Now, the Assyrian goddess, or Astarte, is identified with Semiramis by Athenagoras (Legatio, vol. ii. p. 179), and by Lucian (De Dea Syria, vol iii. p. 382)…Now, no name could more exactly picture forth the character of Semiramis, as queen of Babylon, than the name of ‘Asht-tart,’ for that just means ‘The woman that made towers’…Ashturit, then…is obviously the same as the Hebrew ‘Ashtoreth’” (Alexander Hislop, The Two Babylons, pp. 103, 307-308).”

Like everything, religion and spirituality borrows from one another. Easter is not a duplication of ancient Egyptian traditions but a modified and modernized festival which was influenced by over 3,000 years of cultures and civilizations before Constantine the Great turned the Roman Empire Christian.

March 27, 2013

Egyptian Gods and Goddesses: Bastet – The Lady of the East

Daughter of Ra, Bastet (sometimes also called Bast) was the cat-goddess of the Lower Egyptian city, Bubastis. As an heiress to the sun god, she was the opposite of her twin, Sekhmet, and thus, personified the beneficial aspects of the sun. [1]

Typically Bastet was drawn with the face of a cat (as opposed to her twin, Sekhmet, who had the face of a  lion). Often enough, as the patron goddess of pleasure and joy, she was associated with music and dancing, and was depicted with a sistrum in her hands. [2] As a result of her fondness for frivolity, her festivals (which were held in April and May according to the Stele of Canopus) were known even in Greece for their entertainment. Herodotus points out that hundreds of thousands of people came to Bubastis each year to “get their party on”. (That last part was me).

lion). Often enough, as the patron goddess of pleasure and joy, she was associated with music and dancing, and was depicted with a sistrum in her hands. [2] As a result of her fondness for frivolity, her festivals (which were held in April and May according to the Stele of Canopus) were known even in Greece for their entertainment. Herodotus points out that hundreds of thousands of people came to Bubastis each year to “get their party on”. (That last part was me).

Yet, she was not all fun and games. As the daughter of Ra (and though she was the non-violent twin sister), she was a fierce defender of her father, fighting with the snake, Apep, who tried to stop Ra’s journey through the Underworld.

If you covet Bastet and wear her cat-amulets so that she may protect you against evil spirits, then you want to pay attention to the days she’ll be particularly looking out for you, and the days where she woke up on the wrong side of the bed.

Favorable days are: (1) the tenth day of the second month of Akhet (September 9), as she is surely watching  out for you on this of all days;[3] (2) the fifteenth day of the fourth month of Akhet (November 13), as today is the feast of the twin sisters, Sekhmet and Bastet; and (3) the twenty-first day of the first month of Proyet (December 19), which is the day Bastet guards the red and black lands (Egypt).

out for you on this of all days;[3] (2) the fifteenth day of the fourth month of Akhet (November 13), as today is the feast of the twin sisters, Sekhmet and Bastet; and (3) the twenty-first day of the first month of Proyet (December 19), which is the day Bastet guards the red and black lands (Egypt).

The day where you might not want to step on a crack (and break your mother’s back), is the twentieth day of the third month of Akhet (October 19), as this is the day of Bastet’s going forth, and she is not very pleased about it.

Her name comes from the ancient Egyptian word, bes, meaning “fire”. And, as the twin to Sekhmet (the Mighty One), and the daughter of the sun, she was the embodiment of the aspects of heat and light which encouraged growth.[4]

Because she is connected with the cat, whose eyes become full and very large during the full moon, ancient Egyptians held a similar view and connected Bastet with the moon. She was a lunar goddess. [5]

And, like most Egyptian gods and goddesses, the passage of time and dynasties muddies the water. In some myths she is associated with the goddess, Mut. In others, Bastet is said to be the personification of Isis.

[1] Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Barnett, Mary. P. 85. (1986)

[2] Egyptian Mythology, Goodenough, Simon. P. 83 (1997)

[3] Ancient Egyptian Magic, Brier, Bob. P. 231-237 (1980)

[4] The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol. 1, Budge, E.A. Wallis. P. 441 (1904)

[5] The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol. 1, Budge, E.A. Wallis. P. 442 (1904)

March 26, 2013

Ancient Egyptian Religion, Awakening Osiris: A New Translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead by Normandi Ellis

5/5 Far be it for me to say, but this is the most amazing translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead (Book of Going Forth by Day) that I have ever read. Ellis, though he professes his lack of … Continue reading →

Ancient Egyptian Religion, Awakening Osiris: A New Translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead by Normandi Ellis | Joshua G. Silverman

Awakening Osiris: A New Translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead by Normandi Ellis

5/5

Far be it for me to say, but this is the most amazing translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead (Book of  Going Forth by Day) that I have ever read. Ellis, though he professes his lack of academic status, is a remarkable writer. Basically what he does is he modernizes the language.

Going Forth by Day) that I have ever read. Ellis, though he professes his lack of academic status, is a remarkable writer. Basically what he does is he modernizes the language.

Although I love E.A. Wallis Budge, being one of the foremost Egyptologists in history, he is a strict academic with a strict translation, whereas Ellis brings the ancient text to life. Ellis takes the stilted, wooden translation of the words and gives it depth and meaning. He makes you believe you’re walking with Osiris in the Field of Flowers. He makes you believe you’re sitting with Ra as he travels over the horizon on his boat. What Ellis does, is poetry. It is art. It is the essence, most likely, of how the ancient Egyptians saw their world.

But, my words are not enough. I offer you a comparison:

Plate I of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, translated by E.A. Wallis Budge

Plate I of the Egyptian Book of the Dead translated by Normandi Ellis

“Adoration of Ra when riseth he in horizon eastern of heaven. Behold Osiris, the scribe of the holy offerings of the gods all, Ani! Saith he, homage to thee, who hast come as Khepera, Khepera as the creator of gods. Thou risest, thou shinest, making bright thy mother, crowned as king of the gods, doeth to thee mother Nut with her two hands the act of worship.”

“Stars fade like memory the instant before dawn. Low in the east, the sun appears golden as an opening eye. That which can be named must exist. That which is named can be written. That which is written can be remembered. That which is remembered lives. In the land of Egypt Osiris breathes. The sun rises and the mists disperse. As I am, I was, and I shall be a thing of matter and heaven.

On a midsummer’s day a rustle of beetles fly singing from dry grass to raise the sun like a dung ball. In the sky bright as Nut’s belly above her lover, the sun glints like yellow jasper.”

March 21, 2013

A Writer’s Guide to Reading

I’ve told you once before the two best pieces of advice I received were: read a lot and write a lot. I also expressed how utterly useless that advice is without explaining the how to accomplish those two things.

For the most part, the life of a writer is not glamorous and is solitary. We spend the majority of our time writing or reading (either reading ours or someone else’s work). The rest of the time is spent on research, marketing, travelling to and from events, or working with our publishers, editors, and/or artists to finalize our manuscripts for publication.

Reading for writing requires an active mental presence of mind. It requires focus and critical thinking. You can’t read for fun if you’re trying to learn. You can’t turn your brain off and just put it into neutral (as so many people have told me at conferences). Not to bash reading for fun, I do it all the time. But if you want to be a writer you have to put that aside for a while. Reading doesn’t, in and of itself, make you a writer.

To read for writing, you need to do many things at once.

Be focused and aware of the text. Don’t go into la-la land when you should be focusing on things like word choice, similes, metaphors, and active scenic descriptions which stimulate you. Don’t get too lost in the book. Focus on how the writer is creating these images. What words is he/she using? What is the writer doing to make you feel so absorbed in the book that you forget you left your burrito in the microwave? That is what you need to emulate as an aspiring writer. So sit up, pay attention, and learn not to get lost.

It’s like you’re back in high school. Find the techniques the author uses to evoke an emotional response from the reader. You must understand why the author is doing things a certain way. Is he/she using similes or metaphors? How does the writer describe things? Why does the author have a character do X when the character could have done Y?

The right questions have the right answers. Notice in the first two tips you’re asking a lot of questions? This is because it is fundamental to your success as a writer. Ask yourself as you read the book, why did the writer write the story this way? Why did they use third person instead of first? Why is it in present tense vs. past tense (or vice versa)? How does the writer handle the characters? How much dialogue does the writer use? How much description? How much of the prose is internal monologue and exposition? How does the writer describe setting? Is he/she so descriptive like George R.R. Martin’s style where you know the number of stitches on a piece fabric or is it more like Herbert or King where you’re lucky to know the color of the garment the character is wearing? And, the most important question of all as an aspiring writer: If it were your story, what would you have done differently? Note I said differently; as writing is subjective and an art. There’s really no better or worse way to tell a story.

Find the themes. Most books I know of have a theme. There are some, just a few, that don’t want to reader to learn anything but to be entertained. However, most great books that I know of have themes. It’s your job as a critical reader and aspiring author to look beyond the words and find out what the author is trying to say.

Read in more than one genre. The Emerald Tablet is a science-fiction/fantasy book based in Egyptian mythology. But, to write in a specific genre does not mean that all you are allowed to read is that genre. Limiting yourself to a particular genre is like being trapped in a room without being able to see the whole house. Maybe you want to go out and take a dip in the pool? Maybe you want to watch the game on the big screen in the family room? There are many successful books out there by many writers that don’t write in the genre you want to write in. Study them too. What could it hurt? And oh my God, you may actually learn something.

I say these things because I love writing, not because I want to suck the enjoyment out of reading. But if you want to be a writer, and I hate to say this, don’t be so damn selfish. You won’t always have the luxury for reading for pleasure anymore. You might be tied down to writing, researching, and critical reading to improve your writing. It won’t kill you to be a better writer, will it? And if you’re not willing to invest a little time in studying great writers and learning their tricks and techniques, why would you expect a reader to read your book?

March 20, 2013

Book Review: A Clash of Kings by George R.R. Martin

While not as intriguing as the first book, Martin certainly doesn’t let up. The story picks up where Game of Thrones left off, with children on the run from villainous and tyrannical kings and queens, with certain kings dead and certain boys replacing them, and with the ever present treachery and underhandedness which we’ve come to expect from Martin’s characters.

Martin has a particular skill at character development and all authors should read his books if not for anything else but to learn at how real he can make fictional characters seem. They are not just cardboard cut-outs of the typical fantasy story (i.e. the hero, the villain, the sorceress, the slave). They are each the hero and the villain, the sorceress and the scoundrel, the slave and the king. That’s what makes his writing great. Nobody is any one thing, something I try to emulate as well. We are all the hero of our own story and the villain in someone else’s.

The biggest thing keeping me from giving it four stars was its length. At near 1,000 pages and the real action not starting until page 800, the first 800 pages became a bit of a struggle to get through as it was all thinking and talking and praying. Martin’s gift of words can be his curse, as well. He tends to be wordy where not necessary, have too many tangents and past-perfect tenses which are characters remembering times before that don’t really add to their development or characterization, but are nice side-bits of information. This tends to make the story read slower than it should.

But, despite all that, Martin’s story is still intriguing and thought provoking. I can’t wait to read book 3.

March 17, 2013

Book Review: Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Interpretation by Henri Frankfort

In general, I liked it. It was well researched, obviously, not overly reliant on footnotes (I’ve read some books where there’s more text in footnotes than the actual prose),  and fairly easy to read without getting into too much detail. It’s a good mid-level book for those interested in ancient Egypt. Though, the only thing lacking (which is not the fault of the author or anyone), is that it’s old (1948) and there are better books out there because our technology has greatly improved over the past 60 years.

and fairly easy to read without getting into too much detail. It’s a good mid-level book for those interested in ancient Egypt. Though, the only thing lacking (which is not the fault of the author or anyone), is that it’s old (1948) and there are better books out there because our technology has greatly improved over the past 60 years.

All in all, a short quick read (150 pages), which is well written in a non-academic way which keeps the pace light and fast.

March 14, 2013

Happy Pi Day

“Probably no symbol in mathematics has evoked as much mystery, romanticism, misconception and human interest as the number pi.” - William L. Schaaf

The ancient Egyptians started the hunt for the mysterious number 4,000 years ago. In his book The History of Pi (1971), Petr Beckman speculates that the ancient Egyptians drew a circle, and then measured the  circumference and diameter with rope. They determined that pi was a sliver greater than three, and came up with the value 3 1/8 or 3.125.

circumference and diameter with rope. They determined that pi was a sliver greater than three, and came up with the value 3 1/8 or 3.125.

But the ancient Egyptians didn’t stop at rope measurements. According to the Rhind Papyrus, which was written by an Egyptian scribe named Ahmes around 1650 BCE, he claimed: “Cut off 1/9 of a diameter and construct a square upon the remainder; this has the same area as the circle.” For us non math geeks out there, Ahmes basically said pi = 4(8/9)2 = 3.16049, which was pretty accurate for a mathematician three thousand years ago.

The ancient Greeks, like most things, built upon what the ancient Egyptian mathematicians had done and made two revolutionary leaps forward. Antiphon and Bryson (who both hailed from the city-state Heraclea) thought of the clever idea to inscribe a polygon inside a circle, find its area, and then double the sides repetitively.

This leads us to the main who most people call the father of pi, Archimedes (from the city-state, Syracuse).  Where Antiphon and Bryson failed, Archimedes succeeded. Archimedes focused on the polygons’ perimeters as opposed to their areas, so that he approximated the circle’s circumference instead of the area. He started with an inscribed and a circumscribed hexagon then doubled the sides four times to finish with two 96-sided polygons.

Where Antiphon and Bryson failed, Archimedes succeeded. Archimedes focused on the polygons’ perimeters as opposed to their areas, so that he approximated the circle’s circumference instead of the area. He started with an inscribed and a circumscribed hexagon then doubled the sides four times to finish with two 96-sided polygons.

To quote Archimedes himself in his work entitled, Measurement of a Circle: Given a circle with radius, r = 1, circumscribe a regular polygon A with K = 3(2n-1 sides and semi perimeter and inscribe a regular polygon B with K = 3(2n-1 sides and semi perimeter bn. This result in a decreasing sequence a1, a2, a3… and an increasing sequence b1, b2, b3… with each sequence approaching pi. We can use trigonometric notation (which Archimedes did not have) to find the two semi perimeters, which are: an = K tan ((/K) and bn = K sin ((/K). Also: an+1 = 2K tan ((/2K) and bn+1 = 2K si n ((/2K). Archimedes began with a1 = 3 tan ((/3) = 3(3 and b1 = 3 sin ((/3) = 3(3/2 and used 265/153 < (3 < 1351/780. He calculated up to a6 and b6 and finally reached the conclusion that 3 10/71 < b6 pi < a6 < 3 1/7.

Well, I didn’t get any of that. But, for the next few hundred years most people accepted Archimedes’  calculations. That was until Archimedes’ calculations were refined by James Gregory in 1672 and Gottfried Leibniz in 1685. By 1750, mathematicians could express pi in an infinite series.

calculations. That was until Archimedes’ calculations were refined by James Gregory in 1672 and Gottfried Leibniz in 1685. By 1750, mathematicians could express pi in an infinite series.

Now we have computers to do the work for us, but it all comes back to what the ancient Egyptians started with a piece of rope and drawing a circle in the sand.

Sources:

Archimedes. Measurement of a Circle. From Pi: A Source Book.

Beckman, Petr. The History of Pi. The Golem Press. Boulder, Colorado, 1971.

Wilson, David. History of Mathematics, Rutgers, Spring 2000

Convention Roundup: ConDor 2013: Journeys in Science Fiction and Fantasy

I woke up Friday morning with a kick in my step because I was heading to San Diego for ConDor 2013: Journeys in Science Fiction and Fantasy. I honestly didn’t know what to expect as this was to be my smallest show to date, but the weekend turned out to be amazing. It was a great chance to meet a lot of interesting fans, hear their stories, and share in their passion for Egyptian mythology and sci-fi/fantasy.

Friday started slowly, I think primarily because it was a workday and people didn’t want to use a vacation day or play hooky to come to the show. But at the Town & Country Resort, the vendors still had fun. During the  slow times, vendors generally mingle and network among themselves (though there are a few who like to bury their head in a book or do work—draw/write). This gave me the awesome opportunity to meet Henry Herz, author of the children’s fantasy book Nimpentoad, as well as Valerie Frankel who writes about girls transforming into goddesses in mythology and modern literature. Valarie and I had an awesome chat about the similarities and cross-cultural mythologies of the ancient Sumerians, Greeks, and Egyptians. I also had a chance to meet James Morris, a young author who’s writing the Sky Bound Trilogy, a series of books about the Earth being split into three kingdoms, those that live below the ocean, those that live on the ground, and those that live in the sky.

slow times, vendors generally mingle and network among themselves (though there are a few who like to bury their head in a book or do work—draw/write). This gave me the awesome opportunity to meet Henry Herz, author of the children’s fantasy book Nimpentoad, as well as Valerie Frankel who writes about girls transforming into goddesses in mythology and modern literature. Valarie and I had an awesome chat about the similarities and cross-cultural mythologies of the ancient Sumerians, Greeks, and Egyptians. I also had a chance to meet James Morris, a young author who’s writing the Sky Bound Trilogy, a series of books about the Earth being split into three kingdoms, those that live below the ocean, those that live on the ground, and those that live in the sky.

After the show on Friday, I did my normal thing (get a quick workout in and grab dinner), then settled in for a fun evening of writing in my hotel room (work never stops!). I got down about 2,000 words for book three in my Legends of Amun Ra series and hit the sack, exhausted from a great day of networking.

Saturday and Sunday were by far the most eventful days. The showroom floor was packed with an amazing display of Victorian/Steampunk cosplayers (I’d never seen so many Steampunk cosplayers at once—I’m used to the more comic/anime type).

I was involved in lengthy chats about costume design, hat choices, gadget choices, and the quality of fabrics on some of these outstanding bustles and corsets the women were wearing. I even got a minute to take a few snaps of some Sand People cosplayers from Star Wars. Meanwhile, the table next to me had a FILK singer who was singing acapella with some of her customers and longtime fans.

The fans themselves were great—always willing to stop and chat with me about the intricate nature of the Egyptian gods and goddesses or the mythologies surrounding their favorite stories.

All in all, ConDor 2013 was a great show and I’ll be glad to attend again next year.

March 11, 2013

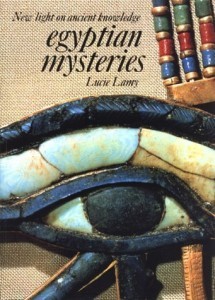

Book Review: Egyptian Mysteries: New Light On Ancient Knowledge by Lucie Lamy

Egyptian Mysteries by Lucie Lamy covers a wide spectrum of the ancient mythology of the Egyptian gods and goddesses. She starts the book with an introduction into some of the more basic concepts of ancient Egypt: the Nile. The Nile was the life-blood of both Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. She goes into great depth about the mythologies surrounding the Nile because it was so important to the ancient Egyptians.

From there, she discusses alchemy and the following of Thoth as well as his sacred writings and the importance writing played with the Egyptian gods and goddesses. Additionally, she elaborates on the feuding gods, Seth and Osiris. She also talks about the magic of Isis and her relationship with Bast and the Nile.

One of the things I found most interesting was the vast information she gave on Horus. As the “sky” god, his iconography was immensely important. Ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses were riddled with symbolism of the universe in their mythology.

Later in the book she goes into great detail involving trigonometry and the subject of the pyramids as well as the Eye of Horus, including pictures and schematics of how the symobology of ancient Egypt was so precise it perfectly fit with their understanding of the world.

All in all, this isn’t an introductory book to Egyptian mythology, but it certainly isn’t as complex as E.A. Wallis Budge’s writings.

If you’re looking for an interesting primer on mythology and the Egyptian gods and goddesses, this might be the book for you.