Lily Salter's Blog, page 272

October 13, 2017

Jimmy Fallon doesn’t “care that much about politics” — that’s what privilege buys

Jimmy Fallon (Credit: Getty/Mike Coppola)

Donald Trump’s presidency has undoubtedly inspired a sense of urgency in entertainers across the country. Awards shows of all kinds are filled with explicit shots at the president. Eminem just dropped a four-minute rap takedown of Trump. The list of celebrities who’ve publicly condemned the president must be longer than his unfulfilled campaign promises at this point.

As critical issues like healthcare, immigration and climate change are being debated and attacked in Washington, most people can’t help but react be they famous or not.

That is, except for Jimmy Fallon.

“It’s just not what I do,” Fallon told Willie Geist during a preview of his interview on “Sunday Today.” “I think it would be weird for me to start doing it now,” he said of engaging in jokes or critiques of the president like some of his late-night counterparts.

Fallon came under intense fire during Trump’s candidacy after hosting him on the “Tonight Show,” and for playfully tussling his hair in what felt like a normalization of the future president’s hateful rhetoric. In an interview with the New York Times afterward, Fallon sort of apologized for his behavior, saying: “If I let anyone down, it hurt my feelings that they didn’t like it. I got it.”

After the white supremacist rallies in Charlottesville, Fallon deviated from his apolitical stance to deliver an opening monologue where he called the violence “disgusting” and Trump’s late condemnation of such actors “shameful.”

But as many were quick to point out, Trump had already done and said absolutely disgraceful things, none of which elicited a response from Fallon. Literally, someone had to die. By then, his stand against literal tiki torch-holding white supremacists and swastika-adorned neo-Nazis seemed too little, too late.

Fallon reverted back to his bottom line in the interview with Geist. “I don’t even really care that much about politics, I gotta be honest,” he said. “I love pop culture more than I love politics.” Jimmy, we all do. We just recognize which is more important.

“I’m just not that brain,” Fallon said. “But with Trump it’s like everyday’s a new thing,” he continued. “A lot of stuff is hard to even make a joke about, because it’s just too serious.”

It’s easy to say you don’t care about politics when the only thing threatened by this administration is your ratings. Not caring about politics is a privilege, one most afforded to straight white men such as Fallon. His rights have never been questioned, nor has his immigration status or his right to marry. People who look like Jimmy Fallon aren’t getting gunned down by the police at alarming rates.

At a time when many performers with visibility and a platform see it their as their duty to speak out — when NFL players are putting their careers on the line for racial justice and ESPN host Jemele Hill is being suspended and targeted by the president for voicing her beliefs — clearly Fallon feels no responsibility on his white, male shoulders. Hell, even Jimmy Kimmel is out there on the court, and he’s as much a good-time Charlie as Fallon.

At this moment, Fallon’s apolitical brand is too convenient and comfortable. With the rest of us — right and left — anything but comfortable, it’s no wonder his ratings are sinking.

There is a feeding frenzy going down in Trump’s swamp

Donald Trump; Mike Pence (Credit: AP/Andrew Harnik/AJ Mast/Photo montage by Salon)

Donald Trump was initially hesitant to use the phrase “drain the swamp.” But as he explained to a raucous crowd in Las Vegas shortly before the election, he changed his mind when he saw his supporters’ reaction.

“I said it, and the place went crazy. Then I said it a second time and the place went even crazier. And then the third time, like you, they started saying it before I said it. And all of a sudden, I decided I love that expression. It’s a great expression!”

When he debuted the expression during his campaign, Trump released an ethics reform plan that focused on cracking down on federal lobbyists. But it quickly became evident that he never fully bought into the idea.

Within a few days of his upset victory, Trump had brought more than a dozen lobbyists into key positions on his transition team, outsourcing the creation of his new government to the swamp dwellers themselves.

The thinly staffed Trump government that has emerged since then is full of lobbyists, including at least three dozen who had recently lobbied on issues of direct relevance to their new government posts.

Trump’s staffing practices are a textbook example of the “revolving door” phenomenon, in which Washington insiders hop from high-paying D.C. influence jobs to government positions – collecting expertise and connections to prepare for their next spin.

A new Public Citizen report looks at the other half of the revolving door equation: cashing in.

We identified more than 40 individuals with close ties Trump or Vice President Mike Pence who have worked as lobbyists this year, trading on their relationships to the White House. These lobbyists are included on billings and reported in-house lobbying expenditures of more than $40 million.

For example, Brian Ballard, who previously lobbied for the Trump Organization in Florida, opened a Washington office after Trump’s election. In the first half of 2017, Ballard signed more than 40 clients and brought in more than $5 million. Robert Grand, a longtime Pence fundraiser, had not signed a new lobbying client since 2013. This year, he has signed 17.

More than half of the lobbyists identified worked on the transition, which was tasked with the highly influential role of recommending appointees and policies for the new administration.

About a week after the election, roiled by headlines over the influx of lobbyists, the Trump transition team issued rules requiring any lobbyists who wanted to stay on to sever their client relationships. At least five transition team members indicated on lobbying disclosure forms that they were “no longer expected” to work as lobbyists for their clients. All five ended up lobbying for at least some of the same clients in the first half of 2017, blatantly ignoring their earlier promises.

The transition team’s ethics rules also supposedly prohibited members from lobbying for six months on issues they worked on during the transition. That rule didn’t appear to mean much, either.

Consider Nova Daly, a lobbyist who worked on trade issues for the transition. He returned to his clients in the first quarter of 2017 and disclosed lobbying on the North American Free Trade Agreement, “import surges,” “Buy America” provisions and “issues relating to trade restrictions,” among other issues. Those sound like the sort of trade issues he would have been working on during the transition.

Daly said that he did not break the ethics agreement because he did not lobby the executive branch. That was an inaccurate reading of the agreement, but at least Daly acknowledged that there was an agreement to break. At least four people who jumped from the transition team or administration to K Street said that they never signed the ethics pledges, or that the rules for some reason did not apply to them.

Trump was right. The crowd did go crazy when he promised to drain the swamp. That was probably because they were infuriated with people in Washington rigging the system for themselves, ignoring the rules and breaking promises.

What would they say now?

Autopilot wars: Sixteen years, but who’s counting?

Flight deck crew prepare to launch an F/A 18 Hornet during early morning flight operations from the USS Theodore Roosevelt, Thursday March 20, 2003. (Credit: AP/Richard Vogel)

Consider, if you will, these two indisputable facts. First, the United States is today more or less permanently engaged in hostilities in not one faraway place, but at least seven. Second, the vast majority of the American people could not care less.

Nor can it be said that we don’t care because we don’t know. True, government authorities withhold certain aspects of ongoing military operations or release only details that they find convenient. Yet information describing what U.S. forces are doing (and where) is readily available, even if buried in recent months by barrages of presidential tweets. Here, for anyone interested, are press releases issued by United States Central Command for just one recent week:

September 19: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

September 20: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

Iraqi Security Forces begin Hawijah offensive

September 21: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

September 22: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

September 23: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

Operation Inherent Resolve Casualty

September 25: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

September 26: Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq

Ever since the United States launched its war on terror, oceans of military press releases have poured forth. And those are just for starters. To provide updates on the U.S. military’s various ongoing campaigns, generals, admirals, and high-ranking defense officials regularly testify before congressional committees or brief members of the press. From the field, journalists offer updates that fill in at least some of the details — on civilian casualties, for example — that government authorities prefer not to disclose. Contributors to newspaper op-ed pages and “experts” booked by network and cable TV news shows, including passels of retired military officers, provide analysis. Trailing behind come books and documentaries that put things in a broader perspective.

But here’s the truth of it. None of it matters.

Like traffic jams or robocalls, war has fallen into the category of things that Americans may not welcome, but have learned to live with. In twenty-first-century America, war is not that big a deal.

While serving as defense secretary in the 1960s, Robert McNamara once mused that the “greatest contribution” of the Vietnam War might have been to make it possible for the United States “to go to war without the necessity of arousing the public ire.” With regard to the conflict once widely referred to as McNamara’s War, his claim proved grotesquely premature. Yet a half-century later, his wish has become reality.

Why do Americans today show so little interest in the wars waged in their name and at least nominally on their behalf? Why, as our wars drag on and on, doesn’t the disparity between effort expended and benefits accrued arouse more than passing curiosity or mild expressions of dismay? Why, in short, don’t we give a [expletive deleted]?

Perhaps just posing such a question propels us instantly into the realm of the unanswerable, like trying to figure out why people idolize Justin Bieber, shoot birds, or watch golf on television.

Without any expectation of actually piercing our collective ennui, let me take a stab at explaining why we don’t give a @#$%&! Here are eight distinctive but mutually reinforcing explanations, offered in a sequence that begins with the blindingly obvious and ends with the more speculative.

Americans don’t attend all that much to ongoing American wars because:

1. U.S. casualtyrates are low. By using proxies and contractors, and relying heavily on airpower, America’s war managers have been able to keep a tight lid on the number of U.S. troops being killed and wounded. In all of 2017, for example, a grand total of 11 American soldiers have been lost in Afghanistan — about equal to the number of shooting deaths in Chicago over the course of a typical week. True, in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries where the U.S. is engaged in hostilities, whether directly or indirectly, plenty of people who are not Americans are being killed and maimed. (The estimated number of Iraqi civilians killed this year alone exceeds 12,000.) But those casualties have next to no political salience as far as the United States is concerned. As long as they don’t impede U.S. military operations, they literally don’t count (and generally aren’t counted).

2. The true costs of Washington’s wars go untabulated. In a famous speech, dating from early in his presidency, Dwight D. Eisenhower said that “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.” Dollars spent on weaponry, Ike insisted, translated directly into schools, hospitals, homes, highways, and power plants that would go unbuilt. “This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense,” he continued. “[I]t is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.” More than six decades later, Americans have long since accommodated themselves to that cross of iron. Many actually see it as a boon, a source of corporate profits, jobs, and, of course, campaign contributions. As such, they avert their eyes from the opportunity costs of our never-ending wars. The dollars expended pursuant to our post-9/11 conflicts will ultimately number in the multi-trillions. Imagine the benefits of investing such sums in upgrading the nation’s aging infrastructure. Yet don’t count on Congressional leaders, other politicians, or just about anyone else to pursue that connection.

3. On matters related to war, American citizens have opted out. Others have made the point so frequently that it’s the equivalent of hearing “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” at Christmastime. Even so, it bears repeating: the American people have defined their obligation to “support the troops” in the narrowestimaginable terms, ensuring above all that such support requires absolutely no sacrifice on their part. Members of Congress abet this civic apathy, while also taking steps to insulatethemselves from responsibility. In effect, citizens and their elected representatives in Washington agree: supporting the troops means deferring to the commander in chief, without inquiring about whether what he has the troops doing makes the slightest sense. Yes, we set down our beers long enough to applaud those in uniform and boo those who decline to participate in mandatory rituals of patriotism. What we don’t do is demand anything remotely approximating actual accountability.

4. Terrorism gets hyped and hyped and hyped some more. While international terrorism isn’t a trivial problem (and wasn’t for decades before 9/11), it comes nowhere close to posing an existential threat to the United States. Indeed, other threats, notably the impact of climate change, constitute a far greater danger to the wellbeing of Americans. Worried about the safety of your children or grandchildren? The opioid epidemic constitutes an infinitely greater danger than “Islamic radicalism.” Yet having been sold a bill of goods about a “war on terror” that is essential for “keeping America safe,” mere citizens are easily persuaded that scattering U.S. troops throughout the Islamic world while dropping bombs on designated evildoers is helping win the former while guaranteeing the latter. To question that proposition becomes tantamount to suggesting that God might not have given Moses two stone tablets after all.

5. Blather crowds out substance. When it comes to foreign policy, American public discourse is — not to put too fine a point on it — vacuous, insipid, and mindlessly repetitive. William Safire of the New York Times once characterized American political rhetoric as BOMFOG, with those running for high office relentlessly touting the Brotherhood of Man and the Fatherhood of God. Ask a politician, Republican or Democrat, to expound on this country’s role in the world, and then brace yourself for some variant of WOSFAD, as the speaker insists that it is incumbent upon the World’s Only Superpower to spread Freedom and Democracy. Terms like leadership and indispensable are introduced, along with warnings about the dangers of isolationism and appeasement, embellished with ominous references to Munich. Such grandiose posturing makes it unnecessary to probe too deeply into the actual origins and purposes of American wars, past or present, or assess the likelihood of ongoing wars ending in some approximation of actual success. Cheerleading displaces serious thought.

6. Besides, we’re too busy. Think of this as a corollary to point five. Even if the present-day American political scene included figures like Senators Robert La Follette or J. William Fulbright, who long ago warned against the dangers of militarizing U.S. policy, Americans may not retain a capacity to attend to such critiques. Responding to the demands of the Information Age is not, it turns out, conducive to deep reflection. We live in an era (so we are told) when frantic multitasking has become a sort of duty and when being overscheduled is almost obligatory. Our attention span shrinks and with it our time horizon. The matters we attend to are those that happened just hours or minutes ago. Yet like the great solar eclipse of 2017 — hugely significant and instantly forgotten — those matters will, within another few minutes or hours, be superseded by some other development that briefly captures our attention. As a result, a dwindling number of Americans — those not compulsively checking Facebook pages and Twitter accounts — have the time or inclination to ponder questions like: When will the Afghanistan War end? Why has it lasted almost 16 years? Why doesn’t the finest fighting force in history actually win? Can’t package an answer in 140 characters or a 30-second made-for-TV sound bite? Well, then, slowpoke, don’t expect anyone to attend to what you have to say.

7. Anyway, the next president will save us. At regular intervals, Americans indulge in the fantasy that, if we just install the right person in the White House, all will be well. Ambitious politicians are quick to exploit this expectation. Presidential candidates struggle to differentiate themselves from their competitors, but all of them promise in one way or another to wipe the slate clean and Make America Great Again. Ignoring the historical record of promises broken or unfulfilled, and presidents who turn out not to be deities but flawed human beings, Americans — members of the media above all — pretend to take all this seriously. Campaigns become longer, more expensive, more circus-like, and ever less substantial. One might think that the election of Donald Trump would prompt a downward revision in the exalted expectations of presidents putting things right. Instead, especially in the anti-Trump camp, getting rid of Trump himself (Collusion! Corruption! Obstruction! Impeachment!) has become the overriding imperative, with little attention given to restoring the balance intended by the framers of the Constitution. The irony of Trump perpetuating wars that he once roundly criticized and then handing the conduct of those wars to generals devoid of ideas for ending them almost entirely escapes notice.

8. Our culturally progressive military has largely immunized itself from criticism. As recently as the 1990s, the U.S. military establishment aligned itself with the retrograde side of the culture wars. Who can forget the gays-in-the-military controversy that rocked Bill Clinton’s administration during his first weeks in office, as senior military leaders publicly denounced their commander-in-chief? Those days are long gone. Culturally, the armed forces have moved left. Today, the services go out of their way to project an image of tolerance and a commitment to equality on all matters related to race, gender, and sexuality. So when President Trump announced his opposition to transgendered persons serving in the armed forces, tweeting that the military “cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail,” senior officers politely but firmly disagreed and pushed back. Given the ascendency of cultural issues near the top of the U.S. political agenda, the military’s embrace of diversity helps to insulate it from criticism and from being called to account for a less than sterling performance in waging wars. Put simply, critics who in an earlier day might have blasted military leaders for their inability to bring wars to a successful conclusion hold their fire. Having women graduate from Ranger School or command Marines in combat more than compensates for not winning.

A collective indifference to war has become an emblem of contemporary America. But don’t expect your neighbors down the street or the editors of the New York Times to lose any sleep over that fact. Even to notice it would require them — and us — to care.

Trump’s zeal to deregulate may lead to a robber baron era

(Credit: Getty/kali9)

The Trump administration has a clear economic objective: deregulate. Loosening regulations on industries, the White House believes, will lead to faster growth and more jobs. This is the stated reason for pulling the U.S. from the international climate accord, and the economic justification for seeking to rescind the EPA Clean Power Plan that limits carbon emissions from plants.

But an examination of history shows that government regulations are not always harmful to industry; they often help business. Indeed, government regulation is as central to the growth of the American economy as markets and dollars.

Robber barons and the Progressive Era

The late 19th century in the United States was the heyday of robber barons – John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Jay Gould and many others – who secured exorbitant wealth by building unregulated monopolies. They controlled the country’s oil, steel and railroads, and they used their wealth to bankrupt competitors, buy off politicians and fleece consumers. They manipulated a growing market economy that had weak rules and even weaker legal enforcement.

The progressive movement of the early 20th century took aim at the robber barons, calling upon government to regulate their activities in the interest of the public welfare. Writing on the eve of the First World War, journalist Walter Lippmann famously explained that Americans had a choice to continue their economic drift into ever-deeper corruption and inequality, or they could empower their elected representatives to master the challenges of their age and create a more just and sustainable economic order. Lippmann and other progressives wanted a more active government, led by men of intelligence, who would regulate the most powerful corporations and ensure that they served the public interest.

The Progressive Era arose in the late 19th century in part in response to poor working and living conditions for workers. This illustration from Puck Magazine shows industrialists Cyrus Field, Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Russell Sage.

Library of Congress

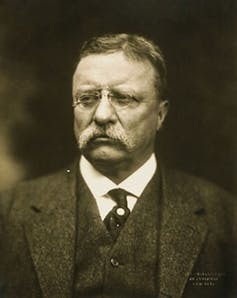

President Theodore Roosevelt was a creature of both the New York business elite from which he came and the progressive reform movement which he eloquently embraced with his calls for a “square deal” to help the poor and “strenuous” efforts by the well-endowed to enter “in the arena.” Roosevelt saw himself as part of an intelligent and energetic elite who would take the reins of government to improve society as a whole.

From the Executive Mansion, which he renamed the “White House,” Roosevelt pushed the federal government to expand its regulatory role over oil, steel, railroads and numerous other industries. He was not anti-business. His efforts proved that government regulation could improve the lives of citizens while allowing businesses to continue to prosper.

Historians of the period like me have, in fact, shown that the progressive era regulations often helped businesses by providing them with a more stable, predictable economic environment, where government regulations enabled increased capital investments and expanded consumer purchases. Progressive regulations of the robber baron market were good for businesses and consumers.

Regulatory ‘capture’

The same is true for regulations a century later. Government activities to ensure competition, transparency and safety in various industries give the American economy stability almost unparalleled in any other country.

Investors send their capital to American companies because government regulations ensure that capital is not stolen or siphoned for corrupt purposes. Talented workers travel to the United States to work in American companies because government regulations protect safe and humane working environments, where businesses are held accountable for fulfilling their obligations to employees. Consumers buy products from American businesses – from food and drink to cars and houses – confident that they are receiving value for their money because of government regulations against cheating, lying and fakery in product sales. Investors buy stocks in the auto companies, workers seek employment in the auto industry and citizens buy cars because government helps protect the integrity of the process at all levels. The federal government bails out shareholders, workers and purchasers when everything goes wrong.

Regulation can stifle innovation, which is why the type of regulation is more important than the number of them. The Bell telephone monopoly was broken up in the 1990s, which helped usher in competition for broadband internet services.

EvgeniiAnd/Shutterstock.com

This is not to say that all regulation is good. Sometimes regulation chokes innovation by slowing change and prohibiting risk taking. This was evidently true for regulated monopolies in mid-20th-century America, including the venerable Bell telephone company.

In other circumstances, regulations empower special interest groups who gain power from laws that protect them and hurt potential competitors. This is true for pharmaceutical and insurance companies who drive the massive and troubled health care industry in the United States today. Government regulations actually disempower doctors, who have reduced control over treatments, and patients, who cannot shop for price when they are choosing health options.

Extensive research shows that business leaders often “capture” regulation. Large companies – particularly in communications, real estate, pharmaceuticals and defense – use clever legal practices, control over information and often brute force to make regulators bend to their will.

The classic case is how lobbyists for Lockheed Martin, Boeing and other military contractors pressure members of Congress, with thousands of constituents employed in the industry, to limit restrictions on their production and sales. The regulators get bought off and bullied into becoming the advocates of the companies they are supposed to control.

Perhaps college athletics is the best example. Does the NCAA really regulate the big college sports programs, or does it advocate for them, and defend them when they bend the rules? As for the fate of the Clean Power Plan, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt is an unabashed champion of the fossil fuel industry, declaring the “war on coal is over” when announcing plans to roll back regulations to limit carbon emissions from power plants.

Consumer benefits

This short history of government regulation shows how complex the issue really is.

The historical record reveals that regulation is generally beneficial to big established businesses: It often solidifies their dominance in markets, stabilizing basic practices. However, regulation will frequently hurt small startup competitors, who cannot mobilize as much influence over the regulators as their bigger counterparts. For consumers, regulation can help or hurt, depending on how it is carried out.

Roosevelt spearheaded regulatory reform but made clear his actions were not anti-business, but were instead aligning business and public interests.

U.S. Library of Congress

With the determined political leadership of a leader like Theodore Roosevelt, regulations can indeed make workplaces safer and products more reliable for citizens, while providing the stable conditions corporations need to do business. But vigilance is necessary, and a number of government boards and agencies emerged to play this role. Hence the creation of federal bodies from the Federal Communications Commission (1934) and the National Labor Relations Board (1935) to the Federal Aviation Administration (1958) and the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), and many others.

When we look forward to the next decade, the question is not whether to have federal regulations. Less regulation will only mean more instability, uncertainty and losses for businesses and consumers. The real question is what kind of regulations, and how can federal, state and local governments administer them to serve the public interest as a whole, preventing excessive red tape, special interest domination and big business “capture.”

What the United States needs is less ideology and more detailed attention among politicians to matching regulatory processes with public purposes. That was, of course, the goal of the progressives more than a century ago. If we don’t return to their model, chances are we will continue the current drift into another age of robber barons.

What the United States needs is less ideology and more detailed attention among politicians to matching regulatory processes with public purposes. That was, of course, the goal of the progressives more than a century ago. If we don’t return to their model, chances are we will continue the current drift into another age of robber barons.

Jeremi Suri, Professor of History and Public Affairs, Mack Brown Distinguished Chair, University of Texas at Austin

5 things Trump said he invented, but didn’t

For Donald Trump, lying comes as easily as breathing, and perhaps it’s even more effortless. He makes up falsehoods about not only big political issues or even sensitive personal matters, but everything. That includes the small stuff, especially if he thinks the lie will make him look good.

If he were smarter, he might choose not to lie about things that can be disproven with a Google search. As it stands, Trump’s claims about his achievements are pretty easy to discredit. That includes his lies about things he’s invented, a list that includes words, ideas, even nicknames. Because the only thing Trump has ever really invented was the idea of selling steaks through the Sharper Image catalog.

Here are five things Trump has lied about inventing.

1. The word ‘fake.’

On Sunday, Trump sat down with Mike Huckabee for an “interview,” if that is what you call it when one person compliments and stares adoringly at another person for half an hour. During this “conversation” — if that’s the word for a meeting between a sycophant and a narcissist fully acting out their respective roles — Trump decided to discuss his invention of the word “fake.”

“The media is — really, the word, one of the greatest of all terms I’ve come up with, is ‘fake,'” Trump said. “I guess other people have used it perhaps over the years, but I’ve never noticed it.”

The most fascinating thing about Trump’s contention is not that it’s patently untrue, but the unvarnished blend of insanity and stupidity in its suggestion that Trump invented a word that’s been in common parlance for hundreds of years. Merriam-Webster points out that usage of the word “fake” dates back to the 15th century. Even giving Trump the benefit of the doubt and assuming he actually meant to take credit for the term “fake news,” the claim still doesn’t hold up. Merriam-Webster points to specific citations of that phrase in the late 1800s.

If you want to watch the entire Trump-Huckabee “discussion” — if that is the way to describe what happens when an owner makes a dog sit very still with a treat on its nose in some cruel, torturous approximation of a trick — it’s in the video below. It includes Huckabee calling Trump a “rock star,” among other embarrassments.

2. An 84-year-old economic theory.

In May, Trump spoke with editors from the Economist, a publication staffed by people who know a lot about economics, the dead giveaway being the fact that it’s called the Economist. Unfortunately, there were no cameras running during the interview, so we can’t see the look on the editors’ faces when Trump insisted he invented a well-established economic theory.

ECONOMIST: But beyond that it’s OK if the tax plan increases the deficit?

TRUMP: It is OK, because it won’t increase it for long. You may have two years where you’ll… you understand the expression “prime the pump”?

ECONOMIST: Yes.

TRUMP: We have to prime the pump.

ECONOMIST: It’s very Keynesian.

TRUMP: We’re the highest-taxed nation in the world. Have you heard that expression before, for this particular type of an event?

ECONOMIST: Priming the pump?

TRUMP: Yeah, have you heard it?

ECONOMIST: Yes.

TRUMP: Have you heard that expression used before? Because I haven’t heard it. I mean, I just… I came up with it a couple of days ago and I thought it was good. It’s what you have to do.

ECONOMIST: It’s—

TRUMP: Yeah, what you have to do is you have to put something in before you can get something out.

Is there anything better than the end of the exchange, when the Economist editor, befuddled and stunned by the whole dumb conversation, starts to repeat Trump’s own words back to him, and instead of listening, Trump plows onward, proudly ignorant and obnoxious? Congratulations, America! You elected Michael Scott president.

There’s also the fact that Trump says he “came up with [‘prime the pump’] a couple of days ago,” despite the fact that he used the phrase multiple times before the Economist interview. Once while he was on Fox News a month prior, and twice during media appearances in 2016.

For the record, the New York Times notes that prime the pump “was in wide use by 1933, when President Roosevelt fought the Great Depression with pump-priming stimulus.”

3. The border wall.

During the election, Trump riled his base of racists and xenophobes with promises of a useless, costly southern border wall to keep brown immigrants out. It wasn’t a new idea — a barrier that runs 850 miles along the dividing line was erected by Bush 43 in 2006, and the border patrol was put in place in 1924. But Trump accused his GOP primary competitor Ted Cruz and others for stealing an idea that hadn’t been his to begin with.

“People are picking up all of my ideas, including Ted, who started talking about building a wall two days ago,” Trump told Politico in January 2016.

During an episode of Face the Nation, Trump said, “I was watching the other day. And I was watching Ted talk. And he said, ‘We will build a wall.’ The first time I’ve ever heard him say it. And my wife, who was sitting next to me, said, ‘Oh, look. He’s copying what you’ve been saying for a long period of time.’”

“Every time somebody says we want a wall, remember who said it first,” Trump said at a New Hampshire rally. “Politicians do not give credit.”

That seems to include “politicians” named Trump who rip off the many racist politicians who have come before them.

Added bonus: Trump also stole an idea for putting solar panels on the wall. From a veteran.

4. The nickname ‘Rocket Man’ for the Supreme Leader of North Korea.

Hilariously, White House staffers have talked up Trump’s use of “Rocket Man” as a nickname for Kim Jong-un as proof that he’s a real-life Don Draper. “That’s a President Trump original,” Sarah Huckabee Sanders . “As you know, he’s a master in branding.”

Is he, though?

Actually, this one may come as a bit of a surprise because it seemed just dumb enough to be a believable Trump (via Elton John) invention. But even this Trump creation originated somewhere else.

The cover of the July 8, 2006, issue of the Economist featured then-North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Il blasting off toward the sky, clouds of smoke billowing from his feet. “Rocket Man” the caption read, an allusion to the dictator’s nuclear ambitions. Trump has reapplied the moniker to his successor and son, Kim Jong-un, who by all indications he seems to think is the same guy. What a shock that a raging racist can’t tell two totally different Asian men apart.

This isn’t to suggest Trump ever read an issue of the Economist aside from the one he was featured in (and even then, he probably only skimmed one-third of his interview). Maybe he saw it when he did an image search for “The Economist” the night before his interview.

5. The whole ‘Make America Great Again’ nonsense.

Trump told the Washington Post that the day after Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss, he got to work on a new slogan for his campaign.

“I said, ‘We’ll make America great.’ And I had started off ‘We Will Make America Great.’ That was my first idea, but I didn’t like it. And then all of a sudden it was going to be ‘Make America Great.’ But that didn’t work because that was a slight to America because that means it was never great before. And it has been great before. So I said, ‘Make America Great Again.’ I said, ‘That is so good.’ I wrote it down. I went to my lawyers . . . said, ‘See if you can have this registered and trademarked.'”

When Trump says America was “great before,” he is obviously referring either to the days of Jim Crow or slavery or Native American genocide, because that pretty much covers America up until this moment. For the record, “Let’s Make America Great Again” was used by Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election campaign. It seems fairly likely that Trump, who was a fully grown adult of voting age at the time, picked it up there. Realizing he might be called out on this, he responded with proactive defensiveness.

“You know, everyone said, “Oh, it was Ronald Reagan’s.” And then they found out they were wrong. His was — and I didn’t know this at the time, I found it out a year ago. I found it out a year after I — his was, “Let’s Make America Great.”

“But he didn’t trademark it.”

October 12, 2017

Noah Baumbach performs a miracle: Adam Sandler doesn’t suck in “The Meyerowitz Stories”

Ben Stiller and Adam Sandler in "The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)" (Credit: Netflix/Atsushi Nishijima)

The place is New York. The time is the present. And Adam Sandler is Danny Meyerowitz, a man who wears stubble with his mustache and a leather jacket with his cargo shorts. He’s searching for a parking spot. He passes one. His daughter, sitting in the passenger seat, tells him about a podcast she likes. He stops — no, a hydrant. A car beeps. “Shut the fuck up!” Sandler screams.

It’s then that the thought bubbles: Yes. Sandler’s back!

For a comedian whose name has been a punchline to a joke about bad comedies for more than a decade, it doesn’t take long for Adam Sandler to win over the audience in “The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected).” Nor does it take much. From that first scene, Sandler does his classic Sandler schtick: he’s a little bit pathetic one moment and he rages bright the next. But he’s doing it on 16mm film, in a literary Noah Baumbach movie. And the result is that coverage of the film has centered around how Sandler “triumphs,” how he is “a revelation,” how he is “miraculously great,” how “it’s time to admit that Adam Sandler is actually a good actor.”

I can’t argue with any of these superlatives. Sandler really is quite good in the film. But the way that the perception of Sandler seemingly changed in an instant is interesting within the context of “The Meyerowitz Stories,” because it’s what the film is all about.

Danny’s father is Harold Meyerowitz (Dustin Hoffman), a visual artist whose works are to be displayed in a retrospective at Bard College. The show serves as a cause for a family reunion. Danny’s sister Jean (Elizabeth Marvel) and his half-brother Matthew (Ben Stiller) visit. Baumbach introduces the siblings as though they are characters in a collection of short stories that have been anthologized. Replace Franny and Zooey with Danny and Matthew (and Jean), and there you have it — formally, at least.

The story of these siblings is the story of them and their father. Danny is the son who Harold never believed in and who didn’t amount to much professionally. Matthew is the golden child, who disappointed his father by becoming a wealthy accountant rather than an artist. And Jean is an afterthought. Each child’s perspective provides a different angle on Harold. He is disconnected with Danny and Jean, overbearing with Matthew. He’s both sensitive and narcissistic.

As Harold’s work is being displayed in a modest show at Bard, his friend and contemporary L.J. Shapiro’s (Judd Hirsch) work is the subject of a new show at The MOMA. Sigourney Weaver comes and tells L.J. how great the work is; meanwhile, no one recognizes Harold. He wears a tuxedo, but it makes him look out of place rather than important.

Even Harold’s children aren’t quite sure whether their father’s work is good or not. Danny thinks it is. Matthew thinks it isn’t. And then Danny second-guesses himself. “If he isn’t a great artist, that means he’s just a prick. But I think the work is good,” he says in one scene.

The viewer only gets a glimpse of a few pieces, and they look unremarkable but also vaguely professional. It isn’t supposed to be clear whether Harold was a good artist or not. The work itself is secondary to how it’s presented. Displayed at Bard, the perception is that the work is middling. If it were displayed at MOMA, though, the perception might be that the work is great.

In “The Meyerowitz Stories,” Baumbach probes subjectivity and the truth within popular narratives — about art and artists, but also about people and places. Harold might see Matthew as a success and Danny as a failure, but to the viewer, those narratives aren’t so clear cut. Danny is an attentive father and son; Matthew, though loving, is more absent.

And New York is equally open to interpretation. To the older generations, the city is a hollow, corporate shell of itself. When Danny looks for parking in downtown Manhattan, he recalls going dancing and laments all the construction underway. On Harold’s bookshelf, there are a series of big books with spines that read “New York 1900,” “New York 1930,” “New York 1960,” which might be the periods for which he’s nostalgic. Yet, for Danny’s college-aged daughter the city just is. And through Baumbach’s classic lens, the city looks as gorgeous as ever.

The most frequent comparison to the dramatic comedies Baumbach likes to make are the films of Woody Allen. But Baumbach also nods to some of the hallmarks of other more kinetic New York classics through the film’s motion. Characters drive to the small towns just outside of the city, like in “Something Wild.” And they run. Man, do they run. There’s something about characters running through the streets of Manhattan that’s always intoxicating — be it in “Marathon Man,” “After Hours,” or some of Baumbach’s previous films, like “Frances Ha” — and in “The Meyerowitz Stories,” it feels as though one Meyerowitz is always chasing after another. At separate points, both Sandler and Stiller are tasked with running down Dustin Hoffman, who at 80, can still move.

I suppose it’s subjective whether “The Meyerowitz Stories” is a good work of art or not. But all of the film’s stars shine, it’s beautifully shot, it’s in turns hilarious and touching and the literary conceit pays off. So I’ll wager that it doesn’t matter whether you see the film in a theater, on Netflix (available Thursday, Oct. 12) or in the MOMA. The quality of Noah Baumbach’s latest isn’t contingent on critical narratives or the perception that comes along with presentation, and it shouldn’t be that hard to parse.

Defining deviancy: The clammy thrills of David Fincher’s “Mindhunter” on Netflix

"Lore" (Credit: Amazon Studios)

Metal has an antiseptic sheen; skin is dirty. Reel to reel tape has concise borders and a distinct purpose. Hair tangles into knots and is superfluous. Microphones absorb sound and speech; the gaping, parted lips of a corpse are a gateway to secrets a dead tongue will never yield. The opening credits of Netflix’s “Mindhunter,” debuting Friday, feature an interlacing of these images, mechanical devices used in crime-solving spliced by quick flashes of lifeless body parts, in a symbolic montage.

Succinctly the sequence illustrates the tale’s central theme, a clash of order and chaos, the firm borders of law and the fractured anarchy of evil, of everything that makes sense and the confusion of what never will. Then again, I could be saying all this because “Mindhunter,” an auteur’s take on the serial killer crime procedural, has tricked me into seeing meaning in its vision that isn’t really there.

What Netflix plies the audience with in “Mindhunter” is a version of the bread and butter that CBS presents in bottomless servings with its wildly successful crimetime programming brand, a series centered upon dedicated noble badges going against the system with the hope of solving nightmarish cases.

But no network shows benefit from the imprimatur of director David Fincher and his fellow executive producer Charlize Theron. Nor, for that matter, do they methodically wade into excavations of the true meaning of deviancy. The cops in this series are baffled, frustrated, and take their time because there is no other choice. They stand on the ghastly line between previous notions of civility and a savagery never previously seen or comprehended.

Fincher executive produces “Mindhunter” in addition to directing four of the first season’s 10 episodes, and his signature cinematic approach permeates every scene. He’s a master of wringing exposition and establishing character’s tics and traits via tightly framed shots of actors chatting passionately. Sometimes this approach lends a fire to the story, but in “Mindhunter” the effect is the opposite — this is the chilly, clinical side of the director at work here.

In fairness, the two “Mindhunter” episodes provided to critics have more going for them than mere atmosphere, largely thanks to robust performances by Jonathan Groff and Holt McCallany, who embody the familiar rookie and veteran cop partnership with a taut crackle.

Together and individually these actors elevate dialogue that comes across as contrived and stilted, particularly in the first episode. But within the expansive context of a series set in culturally liminal year of 1979, when America was still sobering up in the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate, the wooden, brittle writing may be an intentional choice on the part of series creator Joe Penhall.

One view of the ‘70s holds that it was the era in which the long mythologized American sense of decency and trust in governmental authority was irrevocably shattered. Groff evokes this by lending an awkward, out-of-place confidence to his Special Agent Holden Ford, a young man who represents the tail end of a generation that views criminal behavior as a violation of an establishment in which he maintains faith.

Groff is tremendous at making Ford consciously uncool; he doesn’t fit with his contemporaries despite his strivings. In one scene he attempts to impress a colleague examining what the Bureau believes to be a new kind of threat, the homicidal sociopath, by quoting “Dragnet” as if it were gospel.

Ford behaves as if he has all the answers. Criminal motivations fit into predictable categories, such as crimes of passion or acts of desperation.

But when by-the-book practices spectacularly fail him in a field situation with an unstable suspect, he’s reassigned to a teaching position at Quantico.

Eventually Ford partners with veteran Bill Tench (Holt McCallany) in the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, joining Tench on teaching tours of local police departments across the country. Along the way the two men come across unsolved case files involving levels of sadism that defy simple explanation.

“Mindhunter,” based on the memoir of FBI veteran John E. Douglas, benefits from a cast of skilled actors including Anna Torv (“Fringe”) in the role of Dr. Wendy Carr. Like Groff’s and McCallany’s character, Torv’s role is based on a real figure, Dr. Ann Wolbert Burgess. The late Robert Ressler, the FBI agent credited as pioneer of psychological profiling, serves as the model for Tench, while Groff’s Ford is another of Douglas’ many avatars (He is the inspiration for novelist Thomas Harris’ character Jack Crawford).

Aside from a burst of predictable gore in its opening moments, “Mindhunter” initially presents itself as a series that tells much more than it shows and trips over itself as it clunkily lays its expository groundwork in the first episode.

For previously mentioned reasons its narrative style batters the ear and can detract from Fincher’s purposeful camera work. The strain in the writing juts out like a stubborn cowlick during a lengthy meet-cute in which Ford makes the acquaintance of a sociology master’s degree candidate named Debbie (Hannah Gross), whose grad school reading list inspires Ford to consider the sociological underpinnings of deviancy.

While McCallany’s gruff portrayal of a weathered, determined lawman nicely complements Groff’s uptight, inquisitive greenhorn, “Mindhunter” doesn’t fully kick into gear until Ford gets into a room with convicted serial killer Ed Kemper (Cameron Britton), aberrant behavior made flesh.

Once Ford decides to bait and joust with Ed, an unnerving and excessively courteous yet physically imposing slob, the pulse of “Mindhunter” quickens considerably. Groff and Britton prove that a psychological thriller can evoke tension and dread without a droplet of blood splattering the screen. When Ed discusses the delight he takes in murder with the same lackadaisical affect as his rave review of a sandwich, the skin prickles and wriggles.

People familiar with Fincher’s work may get the nagging sense that they can deduce where this is all leading. Then again, one anticipates Penhall and his co-writer Jennifer Haley have taken all the oeuvre’s tropes and practices into account in developing the first season’s plot arc.

In choosing to accentuate the cerebral nature of horror over visceral displays, at least at first, “Mindhunter” departs from the standard approach to such lurid subject matter. These days, an in the realm of streaming, that deviant in itself — and it makes me curious enough to press onward and see what lies in wait for Ford, Tench and a nation on the cusp of a frightening new age.

5 ways you can change the world through art

As an artist, I’ve visited many inner-city schools and have had wonderful opportunities to connect with amazing young people. Their creativity, innovative ideas and worldviews give me an insurmountable amount of hope during these tough political times. I’m fueled by their presence and excited about their futures, as many of them are being exposed to transformative forms of art like creative writing, filmmaking and photography. Not only are they the getting a chance to learn how to express themselves in those media, they are also getting to interact with successful artists who hail from similar backgrounds, who are excited about sharing those skills.

One of those artists making this happen is Devin Allen, a self-trained photographer from west Baltimore. He rose to prominence after the death of Freddie Gray, an unarmed African-American male who died in police custody in 2015. Gray’s death sparked protests and unrest across the city, and Allen, frustrated with the way Gray was being portrayed in the media, took to the streets and documented the events during and after the protests, from the bottom up.

His photographs went viral, stretching across the world and making him the go-to guy for what was happening on the ground in Baltimore. Allen’s art changed the world by providing a perspective that is rarely considered or captured.

Today, Allen spends his free time collecting and giving away cameras to young people who also dream of changing the world with their art. So on this episode of “The Salon 5,” he’s going to share five ways you can use art to change the world, too.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook .

What it’s like to be gay and in a gang

In this Sept. 5, 2014 photo, a reputed member of the Los Solidos street gang shows his tattoo to police in Hartford, Conn. (Credit: (AP Photo/Dave Collins))

There are many stereotypes of and assumptions about street gangs, just as there are many stereotypes and assumptions about gay men. Pretty much none of those stereotypes overlap.

In movies and television, some of the most recognizable gay characters have been portrayed as effeminate or weak; they’re “fashionistas” or “gay best friends.” Street gang members, on the other hand, are often depicted as hypermasculine, heterosexual and tough.

This obvious contradiction was one of the main reasons I was drawn to the subject of gay gang members.

For my new book “The Gang’s All Queer,” I interviewed and spent time with 48 gay or bisexual male gang members. All were between the ages of 18 and 28; the majority were men of color; and all lived in or near Columbus, Ohio, which has been referred to as a “Midwestern gay mecca.”

The experience, which took place over the course of more than two years, allowed me to explore the tensions they felt between gang life and gay manhood.

Some of the gang members were in gangs made up of primarily gay, lesbian or bisexual people. Others were the only gay man (or one of a few) in an otherwise “straight” gang. Then there were what I call “hybrid” gangs, which featured a mix of straight, gay, lesbian and bisexual members, but with straight people still in the majority. Most of these gangs were primarily male.

Because even the idea of a gay man being in a gang flies in the face of conventional thought, the gang members I spoke with had to constantly resist or subvert a range of stereotypes and expectations.

Getting in by being out

Male spaces can be difficult for women to enter, whether it’s boardrooms, legislative bodies or locker rooms.

How could I — a white, middle-class woman with no prior gang involvement — gain access to these gangs in the first place?

It helped that the initial group of men whom I spoke to knew me from years earlier, when we became friends at a drop-in center for LGBTQ youth. They vouched for me to their friends. I was openly gay — part of the “family,” as some of them put it — and because I was a student conducting research for a book, they were confident that I stood a better chance of accurately representing them than any “straight novelist” or journalist.

But I also suspect that my own masculine presentation allowed them to feel more at ease; I speak directly, have very short hair and usually leave the house in plaid, slacks and Adidas shoes.

While my race and gender did make for some awkward interactions (some folks we encountered assumed I was a police officer or a business owner), with time I gained their trust, started getting introduced to more members and began to learn about how each type of gang presented its own set of challenges.

Pressure to act the part

The gay men in straight gangs I spoke with knew precisely what was expected of them: be willing to fight with rival gangs, demonstrate toughness, date or have sex with women and be financially independent.

Being effeminate was a nonstarter; they were all careful to present a uniformly masculine persona, lest they lose status and respect. Likewise, coming out was a huge risk. Being openly gay could threaten their status as well as their safety. Only a handful of them came out to their traditional gangs, and this sometimes resulted in serious consequences, such as being “bled out” of the gang (forced out through a fight).

Despite the dangers, some wanted to come out. But a number of fears held them back. Would their fellow gang members start to distrust them? What if the other members got preoccupied about being sexually approached? Would the status of the gang be compromised, with other gangs seeing them as “soft” for having openly gay guys in it?

So most stayed in the closet, continuing to project heterosexuality, while discreetly meeting other gay men in underground gay scenes or over the internet.

As one man told me, he was glad cellphones had been invented because he could keep his private sexual life with men just that: private.

One particularly striking story came from a member of a straight gang who made a date for sex over the internet, only to discover that it was two fellow gang members who had arranged the date with him. He hadn’t known the others were gay, and they didn’t know about him, either.

Becoming ‘known’

In “hybrid” gangs (those with a sizable minority of gay, lesbian or bisexual people) or all-gay gangs, the men I interviewed were held to many of the same standards. But they had more flexibility.

In the hybrid gangs, members felt far more comfortable coming out than those in purely straight gangs. In their words, they were able to be “the real me.”

Men in gay gangs were expected to be able to build a public reputation as a gay man — what they called becoming “known.” Being “known” means you’re able to achieve many masculine ideals — making money, being taken seriously, gaining status, looking good — but as an openly gay man.

It was also more acceptable for them to project femininity, whether it was making flamboyant gestures, using effeminate mannerisms, or wearing certain styles of clothing, like skinny jeans.

They were still in a gang. This meant they needed to clash with rival gay crews, so they valued toughness and fighting prowess.

Men in gay gangs especially expressed genuine and heartfelt connections to their fellow gang members. They didn’t just think of them as associates. These were their friends, their chosen families — their pillars of emotional support.

Confronting contradictions

But sometimes these gang members would vacillate about certain expectations.

They questioned if being tough or eager to fight constituted what it should mean to be a man. Although they viewed these norms with a critical eye, across the board they tended to prefer having “masculine” men as sexual partners or friends. Some would also patrol each other’s masculinity, insulting other gay men who were flamboyant or feminine.

Caught between not wanting themselves or others to be pressured to act masculine all the time, but also not wanting to be read as visibly gay or weak (which could invite challenges), resistance to being seen as a “punk” or a pushover was critical.

It all seemed to come from a desire to upend damaging cultural stereotypes of gay men as weak, of black men as “deadbeats” and offenders, and of gang members as violent thugs.

But this created its own tricky terrain. In order to not be financial deadbeats, they resorted to sometimes selling drugs or sex; in order to not be seen as weak, they sometimes fought back, perhaps getting hurt in the process. Their social worlds and definitions of acceptable identity were constantly changing and being challenged.

Fighting back

One of the most compelling findings of my study was what happened when these gay gang members were derisively called “fag” or “faggot” by straight men in bars, on buses, in schools or on the streets. Many responded with their fists.

Some fought back even if they weren’t openly gay. Sure, the slur was explicitly meant to attack their masculinity and sexuality in ways they didn’t appreciate. But it was important to them to be able to construct an identity as a man who wasn’t going to be messed with — a man who also happened to be gay.

Their responses were revealing: “I will fight you like I’m straight”; “I’m gonna show you what this faggot can do.” They were also willing to defend others derided as “fags” in public, even though this could signal that they were gay themselves.

These comebacks challenge many of the assumptions made about gay men — that they lack nerve, that they’re unwilling to physically fight.

It also communicated a belief that was clearly nonnegotiable: a fundamental right to not be bothered simply for being gay.

It also communicated a belief that was clearly nonnegotiable: a fundamental right to not be bothered simply for being gay.

Vanessa R. Panfil, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice, Old Dominion University

Add dwarf planet Haumea to the list of solar system objects with rings

Artist concept of Haumea with the newly-discovered ring. (Credit: IAA-CSIC/UHU)

When we think of a ringed planet, most of us envision something akin to the intricate grooves of Saturn’s ring system, which have fascinated humans for centuries. Yet a recent astronomical observation seems to suggest that the distant dwarf planet Haumea, which possesses only about one-third the mass of Pluto, may have a ring as well.

Haven’t heard of Haumea before? That’s not too surprising: it was only discovered in 2004, and there are no direct images of it that look like more than a few low-resolution light blips in the sky. (The image used in this article is an “artist’s conception”; if you want to see a grainy telescope image of Haumea and its moon Hi’iaka, click here.) As a dwarf planet, it’s not one of the solar system bodies taught to schoolchildren the way that the eight major planets are. (Other dwarf planets you may have heard of include Eris, Ceres, Quaoar, and, of course, Pluto, which the International Astronomical Union demoted to “dwarf” status to widespread popular objection.)

Haumea’s orbit around the sun is relatively elliptical, and situates it a bit beyond the orbit of Neptune, albeit at a much greater tilt than that planet; this puts it in a class of solar system objects known as “trans-Neptunians” in addition to being classified as a dwarf planet.

A letter published yesterday in Nature by a consortium of scientists led by José Luis Ortiz at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia in Spain reported on the discovery, based on observational data, that Haumea harbors a thin, rocky ring system around 2300 kilometers from the center of mass of the dwarf planet.

Why are we only just discovering that Haumea has a ring? Well for one, it’s extremely hard to see, by virtue of being quite far away and pretty small, as mentioned. Astronomers had to wait for the dwarf planet to pass by a bright star (relative to Earth) in order to observe how Haumea blocked out the light from the star in the background. This kind of observation — of watching one body pass in front of another, usually brighter body — is known as occultation in the astronomy world, and is a fairly common method of inferring the mass, atmospheric density, and shape of astronomical objects. Indeed, in hunting for extrasolar planets, occultation is one excellent means of observing if nearby stars harbor their own planets.

Multiple ground-based telescopes all across Europe observed how the light from the star was dimmed as Haumea passed in front of it. A telltale dip in light preceding and following the occultation, at the same distance, revealed that Haumea likely had a ring.

This puts Haumea in a class of its own in terms of astronomical bodies with rings. In our solar system, most of the ringed planets are gas giants, not rocky planets. Earth is thought to have briefly had a ring, after a collision with a Mars-sized body, although that ring is believed to have eventually coalesced into the Moon. But a ring around a dwarf planet?

“Until a few years ago we only knew of the existence of rings around the giant planets; then, recently, our team discovered that two small bodies situated between Jupiter and Neptune, belonging to a group called centaurs, have dense rings around them, which came as a big surprise,” said Pablo Santos-Sanz, a member of the research team, in a press release. “Now we have discovered that bodies even farther away than the centaurs, bigger and with very different general characteristics, can also have rings,” he added.

“Different” is an apt description for Haumea: not only is it far away, cold, harbors two moons and has a ring, but it is also egg-shaped. Indeed, the occultation also provided the team with new data about just how elongated Haumea is.

“There are different possible explanations for the formation of the ring; it may have originated in a collision with another object, or in the dispersal of surface material due to the planet’s high rotational speed,” Ortiz said in the same press release.