Lily Salter's Blog, page 248

November 6, 2017

The failure of Larry David’s “SNL” monologue is an argument for letting women lead the way

Larry David on "Saturday Night Live" (Credit: NBC)

“I don’t like it when Jews are in the news for notorious reasons,” said Larry David during his “Saturday Night Live” monologue this weekend. It was a monologue that would put David, a Jewish man himself, in the news for a fairly notorious reason.

Picking up the one story that has dominated the entertainment world over the past three weeks, David steered the national conversation about male predatory behavior that spiked after allegations against Harvey Weinstein came to light into new, perhaps unwise territory.

“I couldn’t help but notice a very disturbing pattern emerging,” David said, “which is that many of the predators — not all, but many, are Jews.”

“I know I consistently strive to be a good Jewish representative,” he said. It, of course, was a joke (David’s comedy is wrapped around the idea that he’s an awful person). “When people see me I want them to say, ‘Oh, there goes a fine Jew for ya!'”

It was . . . odd, and somewhat uncomfortable. But, then again, so is David’s whole act. What truly drew criticism, was the joke below.

I’ve always, always, been obsessed with women and often wondered, if I’d grown up in Poland when Hitler came to power, and was sent to a concentration camp, would I still be checking out women in the camp? I think I would. “Hey Shlomo, Shlomo, look at the one by barracks 8. Oh my God, is she gorgeous! Ugh, I’ve had my eye on her for weeks. I’d like to go up and say something to her.” Of course, the problem is there are no good opening lines in a concentration camp: “How’s it going? They treating you OK? You know, if we ever get out of here, I’d like to take you out for some latkes. You like latkes. What? What did I say? Is it me, or is it the whole thing? It’s ’cause I’m bald, isn’t it?”

For a full look at how David actually delivered the lines, see the relevant part below, beginning around 3:46.

As holocaust jokes go, it’s not a particularly good one, though it does line up precisely with David’s self-effacing, transgressive comedy and his tendency to make a pettier, meaner version of himself the butt of almost all his jokes. It also corresponds to Jewish traditions of playful self-hatred and using the Holocaust as a source of dark mirth. Whether David’s joke on Saturday is funny is entirely up to you.

Certainly the Anti-Defamation League, the self-appointed bulwark against anti-Jewish sentiment in the media and politics didn’t find the monologue the least bit entertaining. “He managed to be offensive, insensitive & unfunny all at the same time Quite a feat,” tweeted ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt.

Watched #LarryDavid #SNL monologue this AM. He managed to be offensive, insensitive & unfunny all at same time. Quite a feat.

— Jonathan Greenblatt (@JGreenblattADL) November 5, 2017

It was a sentiment echoed by critics both Jewish and gentile, both on and off Twitter. As well, David caught substantial heat for entering the ongoing discourse about male predatory behavior in the entertainment industry and beyond and turning it into fodder for a joke about hitting on women in tragic circumstances. Whether those criticisms are valid or not, whether the material was offensive or not, is again, up to you.

What’s less up for debate is that this is a classic case of a comedian not knowing their audience — a cardinal sin in the industry. Indeed, knowing his audience is becoming a bit of a problem for David.

First, it’s worth mentioning that David’s use of Holocaust humor comes with a very particular history.

Those intimately familiar with the bulk of 20th and 21st century Jewish humor would have recognized this effort at grabbing a few uncomfortable laughs. Making light of anti-Semitism by ironically embracing and echoing anti-Jewish hate speech is, as far as we can tell, as old as Jewish involvement in stand-up comedy itself. Using the towering example of anti-Semitism that is the Holocaust as comedic material is, also as far as we can tell, not much younger than the Holocaust. Even those members of the Jewish community who don’t follow professional comedy have probably heard this kind of humor come up over the dinner table, even if they didn’t approve of it.

Many have cast this vein of humor as a survival method, as a way of processing the brutal, ever-present realities of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust in the Jewish mind. Making light of the dark, laughing instead of crying, has become a regular option for many (though just as many in the Jewish community abhor it.)

So, at least one half of David’s monologue was nothing new and, in that, not particularly controversial for many in the Jewish community. What was controversial for all, however, was the context.

In comedy, as in everything, context is everything. Here, the context was all wrong.

Yes, it is one thing for a Jewish person to make jokes that use and make fun of false stereotypes of Jewish miserliness or the Holocaust when surrounded by like-minded members of the community. That’s arguably a safe space where the value of this sort of comedy is known and, if anyone has a problem with those jokes perpetuating anti-Semitism, it can be hashed out in private.

Put those same jokes on a nationally broadcasted platform, however, and the value shifts. Out there on the other side of the television screen, we have men and women who actually believe the worst things one can think or say about Jews, who minimize, deny or actually celebrate the Holocaust, who walk down the street with Tiki Torches chanting “Jews will not replace us,” in polo shirts.

More importantly, you have a plurality of Americans who may not get what you would be trying to do with such a joke, who may not be familiar enough with the value of such self-effacing, transgressive work. A joke that many Jews may have accepted in private becomes completely unacceptable in public.

But it’s more than that, isn’t it?

Co-opting the issue of sexual harassment in Hollywood and trying to meld it with Jewish survival humor is the real failure here.

Yes, just like Jews, those sharing their stories of harassment, and many of those reading them, also need a narrative that will be helpful for surviving, for enduring. Maybe it should be a humorous one filled with similar gallows humor. Maybe it shouldn’t be. Whatever the case, it shouldn’t be determined by an older, rich white man who clearly has problems processing what to say and what not to say about it.

Survivors and the women around them have to lead the way here. Indeed, they’re already starting to. But it’s still under construction, and all of us have to be patient while women comics work on it. Already, there are some laughs available, but not enough to provide any sort of sustained relief from the sadness and anger.

While we wait for that to come, it’s important that we not let others co-opt the territory. More or less, David tried to horn in on the survivor narrative just as its beginning to have its necessary moment in the spotlight and before women in comedy have found a reliable way to discuss it. That was his real sin here.

#MeToo has a right to discover its own brand of survival humor. That David didn’t seem to realize that and, even at that, tried to approach it from a very ’90s, very masculine view of the world shows that — as funny as he still can be — he may already be a comedian who is past his time.

Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson breached impartiality rules, U.K. says

Sean Hannity (Credit: AP/Carolyn Kaster)

The British government’s media regulator, Ofcom, ruled on Monday that certain Fox News segments on Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson’s shows were in breach of the country’s impartiality rules.

The regulator declared that Hannity’s eponymous show violated certain media rules on Jan. 31 during its coverage of President Donald Trump’s travel ban. The U.K. requires adequate representation of “alternative views” on matters of major political and industrial controversy.

“[The alternative] views were briefly represented in pre-recorded videos and repeatedly dismissed or ridiculed by the presenter without sufficient opportunity for the contributors to challenge or otherwise respond to the criticism directed at them,” Ofcom wrote in its finding. “During the rest of the programme, the presenter interviewed various guests who were all prominent supporters of the Trump administration and highly critical of those opposed to the order. The presenter consistently voiced his enthusiastic support for the Order and the Trump Administration.”

Similarly, Ofcom found that Tucker Carlson’s program failed to include a “wide range of significant views when dealing with matters of major political and industrial controversy and major matters relating to current public policy.” The segment at issue was from May 25, when Carlson covered the terrorist attack in Manchester three days earlier.

“There was no reflection of the views of the U.K. Government or any of the authorities or people criticised, which we would have expected given the nature and amount of criticism of them in the program,” Ofcom said. “The presenter did not challenge the views of his contributors, instead, he reinforced their views.”

The ruling comes as the British government examines 21st Century Fox’s bid to buy British media network Sky News. Fox has faced heightened significant scrutiny from British regulators ever since the right-wing network was rocked with sexual harassment allegations. British lawmakers have expressed concern that Fox was too partial towards the Trump administration, especially when it began to push a conspiracy theory about a murdered DNC staffer.

Ofcom’s rulings Monday did not include any fine or censor, but the result definitely doesn’t help chairman Rupert Murdoch’s bid to expand his media empire in the U.K.

Fox pulled its programming in Britain back in August, likely out of fear that its shows could hurt chances to take over Sky News.

Trump’s secret weapon for 2020 is quietly gathering steam

(Credit: AP/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

If you live in a mid-sized city in a battleground state, you are more likely than ever to see pro-Trump propaganda on your local news by next election season — thanks to conservative media giant Sinclair Broadcast Group, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Trump administration itself.

Last week, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) quietly voted along party lines to eliminate its “main studio rule,” which mandated that local news stations maintain offices within the communities they serve. Without the main studio rule, Sinclair is free to consolidate and centralize local news resources in its roughly 190 stations across the country, eliminating the “local” element of local news as much as possible.

This move is just the latest in a thriving symbiotic relationship between the openly conservative Sinclair and the Trump FCC, a relationship that seems to benefit all parties but the American public. And there’s more to come.

Sinclair is known for its history of injecting right-wing spin into local newscasts, most notably with its nationally produced “must-run” commentary segments. The segments, which all Sinclair-owned and operated news stations are required to air, include (frequently embarrassing) pro-Trump propaganda missives from former Trump aide Boris Epshteyn, rants about “politically correct” culture from former Sinclair exec Mark Hyman, and fearmongering “Terrorism Alert Desk” segments that seem to largely focus on just about anything Muslims do.

Just yesterday, for example, as news broke of the federal indictments of former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort and campaign staffer Rick Gates and the guilty plea of George Papadopoulos for lying to the FBI during its investigation into Russian meddling — making it perhaps the worst day in Trump’s presidencyso far — Sinclair was airing a “Bottom Line With Boris” segment in which Epshteyn asserted that impending Republican tax reform was contributing to a soaring stock market benefiting all Americans.

As it stands, Sinclair is broadcasting segments like these on stations across 34 states and the District of Columbia, particularly in local media markets for suburbs and mid-sized cities from Maine to California. The news behemoth is now awaiting FCC approval of its acquisition of Tribune Media, which would allow Sinclair to further spread its propaganda in the country’s top media markets, reaching nearly three-quarters of U.S. households. If last week’s actions are any indication of the five FCC commissioners’ adherence to party lines, the FCC seal of approval for this deal is pretty much a sure thing thanks to its current Republican majority.

Millennials embrace nursing profession — just in time to replace baby boomers

(Credit: Getty)

The days are long past when the only career doors that readily opened to young women were those marked teacher, secretary or nurse. Yet young adults who are part of the millennial generation are nearly twice as likely as baby boomers were to choose the nursing profession, according to a recent study.

These young people, born between 1982 and 2000, are also 60 percent more likely to become registered nurses than the Gen X’ers who were born between 1965 and 1981.

What gives?

“There’s no perfect answer,” said David Auerbach, an external adjunct faculty member at Montana State University’s College of Nursing and the lead author of the study, which was published this month in Health Affairs. The trend could be associated with economic factors, he said. Millennials came of age during a period of deep economic uncertainty with the Great Recession, which began in 2007, and the nursing profession generally offers stable earnings and low unemployment.

In addition, researchers have teased out generational characteristics that might make nursing more attractive to millennials.

“These people are looking for more meaningful work and work that they care about,” Auerbach said.

One thing that hasn’t changed since the 1950s: Nursing is still dominated by women. In 2017, women made up at least 83 percent of registered nurses and licensed practical nurses, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

For the study, researchers analyzed Census Bureau data on 429,585 registered nurses from 1979 to 2015. The study excluded data on advanced practice nurses.

The study found that the number of new entrants into the field has plateaued in recent years. Still, the millennial generation’s embrace of the nursing profession should nearly compensate for the retirement of baby boomer nurses over the next dozen years and may help avert shortages, according to the researchers.

Many factors will influence whether the supply of nurses is adequate in coming years. The health care needs of an aging population is only one of them.

“The growth in accountable care organizations and alternative payment models is probably the biggest factor,” Auerbach said. For example, as hospitals move away from fee-for-service medicine toward models that pay based on quality and cost effectiveness, nurses’ roles may shift, and fewer of them may be needed in hospital settings as inpatient care declines.

Please visit khn.org/columnists to send comments or ideas for future topics for the Insuring Your Health column.

Environmentalists and developers: A love story

(Credit: © Reuters Staff / Reuters)

This was at least the eighth time that Scott Wiener sat through the same PowerPoint presentation, and he was beginning to wonder what the heck was going on. It was 2009, and Wiener was an environmentalist and LGBT-rights activist who had become president of his neighborhood association in San Francisco’s Castro district. Developers were presenting plans for a bunch of apartments atop a Whole Foods — and it seemed like a good idea to Wiener. The development would replace a vacant Ford showroom, it was on a transit line, and it would be designed by deep-green architect William McDonough+Partners.

But before they could build, they had to have meetings — so many meetings!

Even though this project complied with all local zoning codes, city officials had scheduled some 50 meetings to solicit community feedback, Wiener said. It seemed like a system designed to stop developers from building housing. This, he thought, had to be bad for the environment.

Environmentalists are usually thought of as folks who are trying to stop something: a destructive dam, an oil export terminal, a risky pipeline. But when it comes to housing, new-school environmentalists — like Wiener — understand that it’s necessary to support things, too. To meet California’s ambitious goals to cut pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, regulators say the state must build dense, walkable neighborhoods that allow people to ditch their cars.

If you slow down development in cities, houses will sprawl out over farmland, and people will wind up making longer commutes. “You can’t legitimately call yourself an environmentalist,” Wiener says, “unless you support dense housing in walkable neighborhoods with public transportation.”

Wiener decided to get involved in his neighborhood’s development issues, and he got elected to office — first as a San Francisco supervisor, then as a state senator. He’s made it a top priority to ditch all of those redundant meetings and clear away red tape for responsible housing development in cities. This year, he introduced a bill in the California state assembly that served as the lynch-pin in a historic package of 15 new laws aimed at spurring new housing, which San Francisco and other parts of the state desperately need.

All of this makes Wiener perhaps the most powerful voice in the YIMBY — yes, in my backyard! — movement. The YIMBYs are mostly millennials who, angered by the urban housing shortage, have begun demanding a building boom to put roofs over heads, get people out of cars, drive down rents, and stop sprawl.

But the idea that profit-driven builders could provide equitable, environmentally friendly housing sounds like a joke to much of San Francisco’s progressive establishment. The arguments against new, dense development are familiar: homeowners talk about the “character of their neighborhoods,” renters fear losing rent-controlled units. For decades, developers have been the bad guys. Now they’ve got some degree of public support on their side.

“The YIMBYs have pretty much been a Trojan horse for developers,” says Chris Carlsson, a cycling advocate and author in San Francisco.

And it’s not just in the Bay Area. Seems like everywhere across the country where there’s a housing shortage, you’ll find YIMBYs or like-minded advocates for denser development. The result: new partisans within the green movement sparring over policy and throwing more shade than a 50-story tower.

When Wiener got elected to San Francisco’s city hall as a supervisor in 2010, environmental activists would shout at him as he walked through the halls. “There was a lot of opposition to every conceivable housing proposal,” he remembers, “and not a lot of support — other than from the developers.”

Then Sonja Trauss started showing up.

An environmentalist from Philadelphia, Trauss grew up “aggressively committed to biking and walking,” because she didn’t want to be part of the climate problem. “I felt very resentful that people would design cities that required people to buy a car,” she says.

When she moved to San Francisco in 2011, she was shocked to see the local chapter of the Sierra Club opposing development. No matter the proposal — for affordable housing, or a luxury tower — there was always some ostensibly green organization ready to argue that it was fatally flawed. As thwarted projects piled up, something snapped inside her.

“I said, ‘Fuck you guys, I know what you are doing. You are making signs, I can make signs. You are writing letters? We can write letters.’”

She started urging people to join her at planning commission hearings. Anyone who had complained about NIMBYs on Facebook, over beers, or in the comments section of blog posts made her invite list. She made a Google group to keep the conversation going online. It was a snarky, profane community where social justice advocates and libertarians argued, found common ground, and trolled anyone opposed to new housing.

The chaotic nature of the group suited Trauss, who considers herself an anarchist. In a devil-may-care gesture, she named the group the San Francisco Bay Area Renters Federation — SF BARF.

Other YIMBY clubs sprang up (there are now 10 around the Bay Area) — although none had quite as provocative a name. Trauss, like a good anarchist, encouraged them all. “There’s tons of crazy people against development. I wanted to get a bunch of crazy people for development.”

These YIMBYs were a godsend for Wiener. He was no longer in the uncomfortable position of voting against all the community members that came to hearings. “These young, hip millennials were showing up and saying, ‘Hey, I’m a renter, and I want to know what my future is in this city,’” Wiener recalls. “‘Why are we making it so hard to build housing?’”

Unlike the buttoned-up businessmen who had spoken for developments in the past, these YIMBYs made their points forcefully. They could be funny, passionate, and a little unhinged. Trauss showed up for a debate on television wearing a Batman T-shirt.

“I’m really upset by some of the things that were said up here,” one YIMBY stalwart, Laura Foote Clark, ranted at a hearing. “My entire generation has been stunted by a housing shortage brought on by people who can’t stand to have apartment buildings in their neighborhoods.”

When Wiener ran for the California Senate last year, the YIMBYs were squarely behind him. They had more than 200 volunteers knocking on doors, and many more skirmishing on social media. Wiener never missed an opportunity to point out that he had voted for controversial measures to build more housing, which his opponent, Jane Kim, had fought.

It seemed like a risky move, but polls suggested the tactic was sound, he says. “The voters were ahead of the politicians in understanding that we need to have more housing.” (Kim’s office did not respond to an interview request.)

In December, on his first day in the Senate, Wiener introduced a housing bill aimed at fast-tracking developments in that meet zoning regulations in housing-strapped cities. It essentially stripped away the kind of meetings that Wiener had to sit through as a community activist.

To win support, he bargained with labor and environmental groups. The former wanted tweaks to require builders to hire a union workforce, the latter wanted revisions to prevent sprawl and protect prime farmland, wetlands, and coastal areas.

With those amendments, the California League of Conservation Voters and Natural Resources Defense Council both ultimately threw their weight behind Wiener’s measure. The California Sierra Club remained opposed, but “they never went to war,” he says. “They could have made things a lot harder.”

Still, the proposal had powerful opponents, including a powerful committee leader. Five months after Wiener had proposed the bill, it appeared to be stuck in legislative purgatory. “We just have to keep it going,” Wiener told staffers. “Our job is to keep this bill alive and intact until the cavalry arrives.”

As strange as San Francisco’s breed of anarchist-inspired YIMBYs might have seemed to traditional progressives, they’re part of a national trend, as millennial environmentalists embrace a different shade of green from their predecessors. They’re focused on social justice and looming global peril, not on saving beautiful places and individual species.

Carol Galante, a housing policy professor at the University of California, Berkeley, says many environmental groups have started to advocate for housing, reflecting this generational change.

“I see a huge shift happening,” she says.

The Sierra Club straddles that shift, with chapters on opposing sides. Sierra Magazine published an admiring article on the YIMBY movement earlier this year, and the group’s Seattle chapter is led by supporters of denser housing.

But the Bay Area chapter has clashed repeatedly with YIMBYs over both individual projects and big-picture policies. Last year, YIMBYs unsuccessfully tried to shift the chapter’s stance by joining en masse. This April, around the time that Wiener’s bill was beginning to hit opposition in legislative committees, a YIMBY journalist went to a Sierra Club meeting and wrote about members planning to use environmental laws to prevent housing from replacing a car repair shop.

The article garnered attention, and lots of people started pinging the California state lobbying arm of the Sierra Club to ask why they were fighting on the side of cars instead of urban housing.

After reading a series of critical tweets, the director of Sierra Club California, Kathryn Phillips, emailed the leaders of the San Francisco chapter to say that, even if the story was wrong, the chapter should correct the perception that it was using environmental protection rules to stop housing.

“Public perception and political optics right now are not good,” she wrote.

The Bay Area chapter declined my interview request, but leaders sent me a statement agreeing that more affordable housing in urban areas is good for the environment “as long as the ‘solutions’ don’t sell out values that are key to building a sustainable and equitable Bay Area — for example, by breaking urban limit lines, increasing reliance on cars, or prioritizing luxury development over affordable housing.”

But in San Francisco, all market-rate housing must sell at luxury prices to make a profit. The land itself, the community planning process, and the environmental reviews are staggeringly expensive. One new government-subsidized housing project in San Francisco cost $600,000 per apartment to build.

When environmentalists only support housing that offers below-market rents, they’re essentially opposing all private development. Some greens promote creative ideas for land trusts, government-backed co-ops, and other “anti-capitalist” options, as Miguel Robles-Durán, a Parsons School of Design professor, calls them, but experts don’t see those working in the United States anytime soon.

As UCLA planning professor Michael Lens puts it: “You could say we need to blow up the system, but it doesn’t strike me as being particularly realistic. I think the YIMBY movement is right to work within that system and work with developers.”

If the solution is to wait for the government to make affordable housing a priority, hardly anything will get built, argues Argues Brian Hanlon, a car-hating, vegetarian YIMBY: “It’s this idiotic thinking where the environment you are trying to protect gets worse and worse because you are waiting for some perfect solution to be delivered from God or the revolution or something. It’s monstrously unethical.”

When Wiener’s bill stalled in committee this spring, the YIMBYs kept up their support, but it was California Governor Jerry Brown who broke the stalemate in July, threatening to veto other housing bills supported by lawmakers without something similar to Wiener’s fast-track proposal.

The YIMBYs also lobbied for a tax on real estate sales and a $4-billion bond to pay for more affordable housing. Then there was the most audacious bill of them all — a measure to help YIMBYs and developers sue cities that blocked housing projects.

All of this, they hoped, would lead to a boom in urban housing, lower prices, and, eventually, less pollution. Wiener built green cred by working on other environmental bills as well, including measures to boost solar power, water conservation, and recycling (just to name a few).

After negotiations with the governor, legislators realized they needed Wiener’s bill to pass the housing package. On Sept. 14, Clark and several other YIMBYs were drinking in San Francisco’s Mission when word arrived that lawmakers were tussling over the housing measures late into the night.

“We pulled out our laptops and set up a mini war room right there in the bar,” says Hanlon, the car-hating vegetarian. The YIMBYs started emailing their compatriots, asking them to call or contact their legislators on social media. Around 11 p.m., one affordable housing bill after another passed, and the bar erupted in cheers.

Brown brought politicians from around the state to San Francisco to sign the bills into law on Sept. 29. Weiner made a speech, proclaiming: “Today, California begins a pivot — a pivot from a housing-last policy to a housing first policy.”

Is YIMBYism the future of environmentalism? Most researchers I talked to said the pro-housing activists are good for the environment, because they push cities to become denser and more transit-friendly. But not always.

Christine Johnson, the San Francisco director of the urbanism think tank SPUR, applauded YIMBYs for making NIMBYism less attractive, for changing the political conversation, and for fighting single-family zoning, which causes the most environmentally destructive sprawl. But she cautions that there’s a small segment of YIMBYs who embrace any form of housing, including sprawl.

“To really get to a new form of equitable environmentalism, YIMBYs need to take a step further,” she says. “I think they will get there. They aren’t there yet.”

That means taking a strong stand for policies that encourage modest and efficient living in cities, rather than luxury blight. YIMBYs could fight for limits on apartment sizes, Johnson suggests, so that more people can share each new development, and could also campaign for the regional transit lines needed to make dense cities work.

There’s also concern about the movement getting co-opted by developers, who definitely aren’t saints. As Clark started working full time as an activist, for instance, her group YIMBY Action started taking money from developers ($5,000 last year from a building PAC) and tech companies. But the majority of her funding still comes from individuals.

And she’s still not doing it for the money, she says. “There is no amount of money that could make me go to these hearings,” she laughs. “Caring is the worst.”

At least one point is beyond dispute: Californians need more places to live. Housing costs are the main reason that California has the highest poverty rate of any state, worse than Alabama and Mississippi. And California keeps building sprawling subdivisions. Pushing poor people away from the coasts to hot inland suburbs — where they have to run air conditioners and spend hours each day in cars — is terrible for the environment.

The housing crisis is what gives YIMBYs their power. Organizing offers people an outlet for their frustration and an opportunity to influence housing policy on a local level. Advocates can show up at a planning commission, join an online group, write letters to politicians, and knock on doors before local elections.

YIMBYs are making a difference, says Berkeley’s Galante. “They are really driving to get localities to approve new housing across the income spectrum — places with good transit and jobs.”

Now, with the passage of California’s big housing package, they’ve played a crucial role in changing the rules of the game. The new laws will provide more than $1 billion a year to build affordable housing, while eliminating some of the barriers that NIMBYs use to stop new buildings.

There are YIMBY clubs popping up all over the country and around the world.

After last year’s election, Clark went to Wiener’s apartment to interview him for the YIMBY podcast, Infill, which she, Trauss, and Hanlon started last year. His home was tiny and — she whispers — “kind of crappy.” They were both exhausted. After Donald Trump’s election, it felt like the world might crumble around her.

But she also felt like she had just made the world a little better by getting a YIMBY elected to state office. Clark has spent a lot of her life feeling powerless, she said, a sentiment she thinks many young people share. “Especially for millennials — a lot of them landed out of college, and there just wasn’t anything there for them,” she says. “You feel like you’re a bag of shit and a waste of space.

“To be part of something that’s bigger than yourself, and to actually be able to move it forward, is a very uplifting feeling. It feels like it’s not about me. It’s about what we can accomplish together.”

November 5, 2017

Why is it OK to let my kid see some types of movie violence but not others?

(Credit: Thomas Trutschel/Photothek via Getty Images)

Both “The Lego Movie” and “Scarface” have torture, explosions, and guns. But while one mixes in humor, animation, and empathy, the other glamorizes weapons and revenge and includes sexual violence. This difference is important. Research shows that a steady diet of movies portraying relatable, rewarded, realistic violence may have a long-term impact on viewers’ ideas about the necessity of violence and aggression.

But “The Lego Movie” isn’t off the hook. When your kid clonks another kid over the head in imitation of a cartoon character, you’re witnessing mimicry, or short-term impact — another effect of viewing violence.

Neither short-term nor long-term impact has been shown to cause a person to become violent. In other words, a violent movie all by itself will not make your kid violent. It’s the cumulative effect of high exposure to all media violence, combined with other serious risk factors, that may cause a person to be aggressive or violent. Also, the way violence is perceived depends on the kid and his or her age, unique sensitivities, individual temperament, interest in what he or she’s watching, and even home and social environment.

As a parent, it’s best to pay attention to your kids’ behavior after watching violent movies and ask questions to determine how they interpret what they’ve seen. Start with open-ended questions such as, “How do you feel after watching that?” and “Could the characters have handled that situation differently?”

Here are some different types of media violence to watch out for:

Cartoon violence. Though you may think anything animated is no big deal, cartoon violence can affect kids. Boys and girls younger than about 7 can have a hard time distinguishing between fantasy and reality and may interpret a violent act as “real.” And little kids are highly likely to imitate what they see.

Psychological and emotional violence. Kids’ emotional maturity develops in the tween years. Before that, they may not understand emotional violence. Scenes with torture, bullying, explosive anger, coercion, and so on are likely to confuse and scare them.

Sexual violence. Viewing a lot of sexual violence — which is usually depicted as men overpowering women — may lead to increased acceptance of violence toward women and the idea that women enjoy sexual abuse. Women who view a lot of sexual violence may develop low self-esteem and have poor relationships. It’s a particularly poor choice for kids, who may be more affected since their sexual patterns are not yet set.

Consequence-free or well-rewarded violence. When viewers believe that violence is justified, or when it’s rewarded (or at least not punished), they may have aggressive thoughts — especially in the long run.

Violence perceived as realistic. Viewers who believe a movie’s violence “tells it like it really is” and who identify with the perpetrator may be stimulated toward violent behavior over time. Until they hit the teen years, kids will simply be frightened by realistic-looking violence.

Parody violence. Movies that deliberately spoof violence, such as “Ghostbusters,” can be a bit tricky. Kids’ ability to detect sarcasm and irony develops early in the tween years, but many kids are quite literal. Key into how your kid is interpreting the action, and point out the sometimes subtle hallmarks of parody violence (for example, characters’ violent acts tend to backfire, the smug hero gets taken down a notch, and guns shoot a flag that says “Bang”).

American high schoolers lashing out in racist atmospheres

(Credit: Nagel Photography via Shutterstock/Salon)

Across America’s public high schools, the intolerance and bullying modeled by President Trump and the 2016 election has led to an outbreak of incivility, victimization and heightened stresses for a spectrum of minorities, according to a national report from the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education and Access.

Teachers have seen innumerable examples of white students preying on others—feeling empowered by Trump’s rhetoric and policies. Students on the receiving end have shouldered pressures not just from insensitive peers, but exhibited stressful symptoms tied to threats of deportation and victimization due to their race, religion and gender identity. In many schools, teachers are overwhelmed and are avoiding topics that could provoke attacks in the classroom and predatory behavior in the hallways. In other schools, administrators have had to take extra steps to publicly draw lines on discrimination, racial profiling and harassment of LGBTQ students.

These dismal trends were described in great detail, with many testimonials from teachers, in the UCLA report, Teaching and Learning in the Age of Trump: Increasing Stress and Hostility in America’s High Schools by John Rogers and his research team. The scholars at UCLA interviewed more than 1,500 teachers in 333 public high schools nationwide starting last spring, followed up by more discussions over the summer.

“Throughout his campaign and in his presidency to date, Donald Trump has addressed a number of ‘hot-button’ topics that call into question the status or rights of many different groups in American society,” their report’s summary said. “The charged political rhetoric surrounding these and other issues often has been polarizing and contentious. Many would agree that, since Donald Trump has moved into the White House, national political discourse has become a more potent force in shaping the consciousness and everyday experiences of Americans. It is important to ask if this new political environment has impacted high school students.”

The report begins with statistics quantifying the increases in stresses in students as seen by teachers, compared to before the 2016 election. These figures are alarming, as they show how public schools, which, for decades, have been a great equalizing force in the country, have become venues for bigotry and victimization.

For example, the report says stresses facing students are skyrocketing, “particularly in schools enrolling few white students.” The researchers note:

• 51.4% of teachers in our sample reported more students experiencing “high levels of stress and anxiety” than in previous years. Only 6.6% of teachers reported fewer students experiencing high stress than previous years. A Pennsylvania teacher reported: “Many students were very stressed and worried after the election. They vocalized their worries over family members’ immigration status and healthcare, as well as LGBT rights.”

• 79% of teachers reported that their students have expressed concerns for their well-being or the well-being of their families associated with recent public policy discourse on one or more hot-button issues, including immigration, travel limitations on predominantly Muslim countries, restrictions on LGBTQ rights, changes to health care, or threats to the environment.

• 58% of teachers reported that some of their students had expressed concerns in relationship to proposals for deporting undocumented immigrants. A Nebraska coach recounted that some of his student-athletes have begun to live their lives in “survival mode” because “at any time they could be possibly picked up by the police and deported to a country that they didn’t even grow up in.” A Utah teacher overheard her students grappling with what would happen should their undocumented parents face deportation. “Would I stay, because I was born here,” one student asked. “But how would I survive if my dad got taken back to Mexico?”

These first-person accounts are as riveting as they are disturbing, because they also underscore how Trump’s rhetoric and policies are undermining education itself—how students study, converse, communicate and learn.

The UCLA report said, “44.3% of teachers reported that students’ concerns about well-being in relation to one or more hot-button policy issues impacted students’ learning—their ability to focus on lessons and their attendance. A number of teachers also pointed to policy threats undermining students’ educational and career goals. A New Jersey teacher related that one of her students “had to postpone her plan to join the Navy because her parents had made her legal guardian of her siblings, in the event that her parents were deported.”

The increased polarization has included a rise in white supremacy. “Polarization, incivility, and reliance on unsubstantiated sources have risen, particularly in predominantly white schools,” the report said. “More than 20% of teachers reported heightened polarization on campus and incivility in their classrooms. A social studies teacher in North Carolina noted: “In my 17 years I have never seen anger this blatant and raw over a political candidate or issue.” A West Virginia social studies teacher explained that her students have interpreted politicians saying, “It’s not important to be ‘politically correct’” to mean “I can say anything about anyone.”

“27.7% of teachers reported an increase in students making derogatory remarks about other groups during class discussions,” the report said. “Many teachers described how the political environment “unleashed” virulently racist, anti-Islamic, anti-Semitic, or homophobic rhetoric in their schools and classrooms. An Indiana English teacher explained: “Individuals who do harbor perspectives and racism and bigotry now feel empowered to offer their views more naturally in class discussions, which has led to tension, and even conflict in the classroom.”

The report also said administrators and leaders in less than half the schools are responding proactively to try to counter or contain these aggressions.

“40.9% of teachers reported that their school leadership made public statements this year about the value of civil exchange and understanding across lines of difference,” the report said. “But beyond the “public statements” only 26.8% of school leaders actually provided guidance and support on these issues, as reported by teachers in the survey. Teachers in predominantly White schools were much less likely than their peers to report that their school leaders had taken these actions. Hence, the schools most likely to experience polarization and incivility were the least likely to have leaders responding to these issues proactively.”

Nearly three-fourths of the teachers surveyed agreed that, “My school leadership should provide more guidance, support, and professional development opportunities on how to promote civil exchange and greater understanding across lines of difference.” And more than nine out of ten teachers squarely placed the blame on political leaders, who they urged to start modeling better behavior. “91.6% of teachers surveyed agreed that: “national, state, and local leaders should encourage and model civil exchange and greater understanding across lines of difference.” Almost as many (83.9%) agreed that national and state leaders should “work to alleviate the underlying factors that create stress and anxiety for young people and their families.”

Teacher Testimonials

The report’s most compelling elements, however, were not the big-picture statistics. They were first person accounts from teachers about the pain that students — empowered by Trump’s racism, intolerance and bullying — are inflicting on others, as well as the impact and response among the targeted students. What follows are excerpts from the report’s first person accounts.

• Nicole Morris, a Utah social studies teacher, said some students felt on edge with anxiety because the Trump administration’s policies and rhetoric on immigration enforcement threatened their families. Morris describes one student sitting in her geography class “worried about his parents getting deported,” while trying to focus on a lesson about the religions of India. Another of her students uncharacteristically missed homework assignments after “his dad got deported” because “he’s now working to help support his family,” and so has less time for school assignments. For these students, she concludes, “it was more stressful, for sure.” For a few students, being on the edge meant being open, when they previously would have remained silent, about the vulnerabilities they felt in the face of the changing political climate. Such was the case for students who, after the election, told classmates, “This could be a big thing for my family.” Or, for another student who shared that election results were particularly disturbing to her because she was a survivor of sexual assault. “I guess what this means,” she told the class, “is it’s okay to openly assault women.”

• Jeff Seuss, a social studies teacher and coach in Nebraska, reported that some of his student-athletes have begun to live their lives in “survival mode” because “at any time they could be possibly picked up by the police and deported to a country that they didn’t even grow up in.” In New Jersey, many of Lisa Camden’s students from immigrant families similarly experienced “far greater levels of stress.” She noted that, “in class, students have cried about how they are worried about the outcome of their family members.” Several teachers reported that the greatest fear for students was the prospect that their parents would be deported, leaving them all alone.

• Connecticut English teacher Amy Clark recalled the intense reaction of fear that came every time one of her students received his mother’s text, as he worried that this would be news that his father had been detained. In Ohio, Aaron Burger recounted the story of an undocumented student — a “bright and engaged kid” — whose mother had heard rumors about Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials raiding a workplace much like her own. Burger’s student “broke down and cried and wondered if she was next.”

• In Delaware, one of Jake Norris’ highest performing students — Amina — underwent a dramatic change following the announcement of the travel ban. Whereas Amina previously had a “good sense of humor” and was “very dedicated to her studies,” she became deeply concerned that “she was never going to see some people again.” Amina also generally felt more vulnerable: “like if her father did his taxes wrong, then they were all going to get forcibly removed from their home.” Norris described how Amina “visibly changed — her color had changed, her demeanor, her body language.”

• Whereas immigrant youth and Muslim youth often expressed concern about specific policies or potential enforcement actions, LGBTQ youth and their allies responded to a more general sense of threat that they sensed from national political rhetoric. Astrid Natividad, an English teacher in New York reported: “I have gay students who were scared that they were going to lose the rights that they just celebrated achieving.” Across the country in Oregon, Jane Gorman noted that the group of students who were “most visibly upset, and afraid, and scared” following the election were her LGBTQ students or kids who identified closely with the community because of friends and family.” Stacy Marx, an English teacher working in what she describes as a very conservative Wyoming community recounted a similar story. One of her students cried in class the day after the election and “the biggest reason she felt so sad was that she was talking about all of her friends that are like transgender, or bisexual, or whatever, and she just felt like the hateful talk towards them would increase, so it hit her that way.”

• A number of teachers spoke about the ways that national political rhetoric shaped student interaction during class discussions. Colorado English teacher Kimberly Bran wrote that “the tone of the election spilled into the classroom and many students felt free to make unkind statements to those who did not agree with them.” Jimmy Lloyd in Utah spoke eloquently about the tendency for students to approach classroom discussions as an opportunity to “mock or offend.” He went on to explain: “I believe the unhealthy discourse that surrounded the previous election and that continues into the current presidential office has empowered students to speak recklessly and even disrespectfully because it is now seen as normal . . . Students feed off of this.”

• Many teachers responded to heightened tension in their classrooms by avoiding uncomfortable topics. Emily Hall in Delaware reported that she has been “less likely to bring up politics . . . [because] both sides are so emotionally charged . . . that they forget to respect each other’s thoughts.” She went on to add that it has been very hard to maintain civil exchange, and concluded: “So I avoid.” For some teachers, avoidance entailed eliminating all engagement with current events. Joshua Cooper in Wisconsin tried to steer clear of any issues that might provoke “potential conflict.”

• Numerous teachers spoke of ways that dynamics in the broader political environment unleashed prejudicial, racist, and xenophobic sensibilities. Patrick Sawyer in Texas wrote that on his campus there was a feeling of “justification, of outwardly being more open with bigotry, etc. because of the election results.” In Virginia, some of Will Carmel’s white students explained to administrators that they had a right to taunt “Hispanic students with ‘build the wall’” because “this isn’t any different” than what the president has done. Pat Weber, an English teacher in Indiana explained: “Individuals who do harbor perspectives and racism and bigotry now feel empowered to offer their views more naturally in class discussions, which has led to tension, and even conflict in the classroom.”

• Jude Canon, who teaches in what he described as a “very white community” in North Carolina, recounted a searing incident of racial intimidation that occurred in his U.S. History class. In the course of a lesson on Columbus enslaving and mistreating the native people in Hispaniola, one of his students said: “Well, that’s what needed to happen. They were just dumb people anyways like they are today. That was the purpose, that’s why we need a wall.” Multiple student agreed, leading to what Canon characterized as a “huge rile in the classroom.” After class, two Latina students whose families are migrant workers came up to Canon and said: “That’s not something we want to talk about. . . He doesn’t need to be saying stuff like that in class. We are worried for our wellbeing. We’re worried about things not going good for us.”

• Students overtly embraced the logic of white supremacy, deployed rhetoric or symbols made popular through national politics, and confronted classmates in threatening ways. Ingrid Dane, an English teacher in Washington reported that some of her students have: Told African Americans in my class that they wish they could go back to the “good old days,” referring to slavery times. And still others have told Hispanic students how excited they are about the wall. “Make America Great Again” has become a popular slogan to say when demeaning someone, telling someone to leave the country, and telling female classmates they should learn to cook and not go to college.

• In Arkansas, Tracy Neely has overheard students in the hallway saying: “National Geographic will have to print a retraction because it is scientifically proven that whites are the superior race.” Some students have incorporated these ideas into writing and class discussions. Susan Boyer, in Delaware, reported that one of her who had made numerous discomforting comments in class, “defend[ed] the institution of slavery as a just cause.” What was particularly striking to Boyer was that this student presented a ‘white supremacy argument” rather than a more typical case for states’ rights. While bigotry certainly is not new in American public schools, the substance and tenor of these incidents struck many teachers as a dramatic departure from the norm. Boyer told us: “I have never heard anything like this before.”

• Acts of intimidation and hostility took their toll on young people and undermined student learning. Jimmy Lloyd described the experience of Muslim students in his Utah school who faced bullying in the wake of the President’s travel ban. “They were mocked. It was a small percentage of students doing it, but to those students who heard those kind of jeers, it felt like the entire school was against them.” Richard Dorn, a social studies teacher in Tennessee, similarly highlighted a feeling of vulnerability and marginalization that characterized two groups of students at his school. The LGBTQ and immigrant students tried to make themselves invisible to potential assailants. Dorn explained that they “just kind of went underground . . . they didn’t engage. They kind of hid from this.” Missouri teacher Delia Gonzalez worried about the “long-lasting effects” of students “being harassed, targeted, effaced by their peers.” She related that these problematic dynamics have silenced students — they have “backed away from conversations.”

What Can Be Done?

The UCLA report importantly notes that bullying, prejudice and discrimination were problems in public high schools before the 2016 campaign and Trump’s election. More than anything, the report’s authors say targeted students and populations need support, while the provocateurs and bullies need to be held accountable and set straight.

“What additional action is then needed?” the report asks. “A first answer is more support. While some teachers share [Delaware teacher] Jake Norris’ sense of agency, most would like more support so that they and their colleagues can promote civil dialogue in their classrooms. 72.3% of teachers we surveyed agreed that: “My school leadership should provide more guidance, support, and professional development opportunities on how to promote civil exchange and greater understanding across lines of difference.” Teachers from all parts of the nation and teachers working in demographically distinct schools supported this statement at similar levels.”

“A second answer to what is needed is more data and reflection about how the new political environment is shaping student experiences,” the report said. “Bruce Williams, a social studies teacher in North Carolina, develops such understanding through ongoing observation and writing. “I think the thing that has changed for me is the amount of self-reflection. It’s deeper. . . Jotting down the notes, and doing diaries, and journals on my own, to make sure I’m actually sticking to what I believe because of the climate, because of the stuff that’s out there.” Williams’s commitment is to be admired. Yet, we need structures and conditions that ensure that such reflection becomes a normal part of how educators do their work. Reflective practice requires access to information and time and space to make sense of this information and forge plans of action.”

While these suggestions and others are laudable, there’s no denying the big picture is terribly disturbing. Nobody who has studied human nature expects bigotry and prejudice to disappear, but in recent decades educators have been in the forefront of modeling tolerance, respect and communication. Sadly, the political arena, led by the president, is not just rolling back the clock to more racially divisive times; he’s encouraging the darkest forces of human nature to emerge from the shadows and take center stage. As the UCLA report says, America’s high school students are following these dismal cues.

Steven Rosenfeld covers national political issues for AlterNet, including America’s democracy and voting rights. He is the author of several books on elections and the co-author of Who Controls Our Schools: How Billionaire-Sponsored Privatization Is Destroying Democracy and the Charter School Industry (AlterNet eBook, 2016).

Stoked! Weed may light the flame for a roll in the hay

(Credit: Getty/Juanmonino)

Many states permit the use of medical marijuana. Now there’s evidence that pot might work as “marital marijuana,” revving up sex drives in both men and women.

The exact nature of the cannabis-coitus connection remains unresolved, but researchers attempted to cut through the haze with a new study published in the November issue of the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

It showed that people who toke up are more likely to get down (and dirty).

It actually doesn’t matter who’s partaking — male or female, single or married, childless and carefree, or busy breeder. Among all demographic and ethnic groups, those who smoke weed reported having more sexual intercourse than those who don’t, the research shows.

“I was surprised,” said Dr. Michael Eisenberg, the study’s senior author and an assistant professor of urology at Stanford University School of Medicine.

The study is based on surveys of more than 50,000 Americans ages 25-45, conducted over more than 10 years by the National Center for Health Statistics.

Before seeing the results, Eisenberg had been telling his patients that getting baked might be a drag on their sex drive or performance. But now he’s much more confident that marijuana isn’t interfering with sexual behavior. And that’s good information these days, especially in a state like California, which already allows medical marijuana and is preparing to go all the way with recreational sales next year.

Last November, California voters approved Proposition 64, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, making California one of eight states — plus the District of Columbia — to legalize the drug for recreational use. The measure immediately made it legal for adults 21 and over to possess up to 1 ounce of cannabis, but delayed legal pot sales from licensed retailers until the beginning of 2018.

Eisenberg cautioned against drawing unwarranted conclusions from the study and cited the statistical adage that “correlation does not equal causation.”

“This doesn’t mean that if you want to have more sex, you should start smoking marijuana,” he said. “That’s definitely not what this data supports.”

But Eisenberg said the study could change how he counsels patients who already smoke marijuana. Previously, he’d advised them to quit smoking pot if they were having trouble with libido or sexual performance.

Now he thinks quitting might not be necessary, and that patients can focus on other lifestyle changes to increase libido.

“If somebody is using marijuana to help them for chronic back pain or something like that, there may be other interventions that we can think about targeting, rather than telling them they have to stop, otherwise their sex life is doomed,” he said.

Pot use and sexual activity appear to have a “dose-response relationship.” That means the more you smoke, the more likely you are to have had sex in the past month.

“The daily users, for example, compared to the never-users, reported about 20 more sexual encounters a year. So I think that is a significant difference,” Eisenberg said.

The survey respondents were not asked how much pot they smoked when they smoked. But it did ask about how much sex they had. According to the study, non-users said they had engaged in sexual intercourse between five and six times in the previous month.

But daily pot smokers reported having intercourse about seven times over that same period. The frequency was somewhere in between for people who smoked marijuana less often, on a weekly or monthly basis. They reported having sex more than abstainers, but less than daily users.

“For every group, the more marijuana use that they reported, the more sex they reported as well,” Eisenberg said. “So that … made me think that there could potentially be some biologic explanation here.”

Dr. Holly Richmond, a sex therapist who practices in Los Angeles and Portland, Ore., calls that finding “fantastic.”

“Obviously I’m not going to tell a couple that doesn’t use marijuana to use it,” she said. But “if they were interested, I would offer the information.”

Richmond said she has seen mixed results among her clients who use marijuana. Some couples tell her that they have more sex when they use pot; others have less.

She said those differences are probably attributable to how much pot someone smokes instead of how often they smoke.

“Too much can lead to lethargy and really checking out, which does not facilitate [emotional] connection at all, and definitely doesn’t encourage sexual activity,” she explained.

The results shed no light on what factors drive the association between pot use and sex, according to Dr. Igor Grant, chair of psychiatry and director of the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research at the University of California-San Diego.

The simplest explanation might be that the type of person who smokes pot — or is willing to admit it in a survey — also likes sex more. Grant called those people “risk-takers” or “sensation-seekers.”

“Drug use is one type of sensation-seeking behavior, and obviously sex is another,” he said.

Eisenberg said the study also controlled for other risk-taking behaviors, such as cocaine or alcohol.

He suspects marijuana may be stimulating arousal or other neural pathways in the brain. That’s different from Viagra, which works directly on the vascular system to improve blood flow to the penis.

But the study has some limitations. For instance, the study relies on self-reporting — and therefore imperfect memories — from participants who were asked to remember how many times they smoked pot in the past year and how many times they had sex in the past four weeks.

Also, the survey asked only about sex between men and women, so it’s unclear how marijuana affects same-sex encounters.

Still, the results fly in the face of some previous research, such as studies indicating that heavy marijuana use is associated with erectile dysfunction. Plus, research on cigarette smoking shows negative vascular effects that can interfere with male arousal, Eisenberg said.

The results also contradict stereotypes about stoners. Grant summed it up as “people just, you know, not feeling like having sex if they’re stoned all the time.”

Richmond, the sex therapist, agreed that those stereotypes exist, so this study could be reassuring to people who enjoy marijuana and also enjoy sex. At the very least, the study shows smoking weed doesn’t appear to decrease sexual activity.

“Individuals and couples look for additional ways to create novelty in the relationship and have fun, and [in some states] that’s now a legal and accessible way to do it,” she said.

This story is part of a partnership that includes KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

How the government can make disasters wose

Local residents wade through flooded streets after Hurricane Harvey (Credit: Getty/Mark Ralston)

As Hurricane Harvey roared toward the Texas coast in late August, weather models showed something that forecasters had never seen before: predictions of four feet of rainfall in the Houston area over five days — a year’s worth of rain in less than a week.

“I’ve been doing this stuff for almost 50 years,” says Bill Read, a former director of the National Hurricane Center who lives in Houston. “The rainfall amounts … I didn’t believe ‘em. 50-inch-plus rains — I’ve never seen a model forecast like that anywhere close to accurate.

“Lo and behold, we had it.”

That unbelievable-but-accurate rain forecast is just one example of the great leap forward in storm forecasting made possible by major improvements in instruments, satellite data, and computer models. These advancements are happening exactly when we need them to — as a warmer, wetter atmosphere produces more supercharged storms, intense droughts, massive wildfires, and widespread flooding, threatening lives and property.

And yet the Trump administration’s climate denial and proposed cuts threaten these advances, spreading turmoil in the very agencies that can predict disasters better than ever. The president’s budget proposal would slash the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s budget by 16 percent, including 6 percent from the National Weather Service.

Besides hampering climate research, the cuts would jeopardize satellite programs and other forecasting tools — as well as threaten the jobs of forecasters themselves. And they may undermine bipartisan legislation Trump himself signed earlier this year that mandates key steps to improve the nation’s ability to predict disasters before they happen.

It’s hard to overstate how backward that seems after the hurricane season we’ve just witnessed, as well as the deadly wildfires in California, the climate-charged droughts and deluges and, well, you name it. Just when we need forecasting to be better than ever — and need our forecasters to be able to go even further, using those predictions in ways that protect people’s lives and livelihoods — the Trump administration wants to cut back?

Here’s how far we’ve come in forecasting: Three-day hurricane forecasts are now nearly as accurate as one-day forecasts were when Katrina struck 12 years ago. Even routine, “will it rain this weekend?” forecasts are better today than you probably realize. A 2015 paper in the journal Nature called the advancements a “quiet revolution,” both because they’ve gone relatively unnoticed by the general public, and because it’s been cheap. The National Weather Service, an agency of the U.S. government, costs taxpayers about $3 per person each year.

Still, knowing what the weather is going to do tomorrow and understanding how best to warn the public about potential risks are two different things. The first is all about physics; the other is about psychology, human behavior, social interaction, the built environment, and much more. You can guess which is easier.

Forecasts for Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall totals might have been stunningly accurate, but the floodwaters still surprised thousands of people. Days after Harvey’s rains ended, first responders in towns throughout southeast Texas were still rescuing families stranded by rising waters that flowed downstream toward the Gulf.

In the interest of saving lives, forecasters have started moving from simply predicting the weather to attempting to predict the consequences. Call it impact forecasting, an attempt to say what will happen after the rain hits the ground. Scientists hope to answer questions like: Where will water accumulate? Where will floodwaters head? How will it affect people?

The next step is using those “impact forecasts” to get people to safety. Researchers are working to build customized, real-time personal prediction tools that could tell people if their house is likely to flood, or how long they might go without power. There’s also a drive to create easier to understand warning systems, making better use of the latest communication tools and social media.

Besides getting people out of harm’s way, better warning systems could help by letting nonprofits seek donations in advance of a devastating storm, for instance, so they could provide relief more quickly. And they could help public officials do a better job of prepping for the worst.

The need for this new branch of forecasting was highlighted during the height of Harvey’s rains, when the National Weather Service issued a bulletin that put the deluge in stark terms: “This event is unprecedented & all impacts are unknown & beyond anything experienced.”

“This was a good step forward,” says Kim Klockow, a meteorologist and behavioral scientist at the University of Oklahoma who supports the effort to develop impact forecasting. “It admitted something very important,” Klockow says — namely, that the system we have for warning people isn’t good enough.

In fact, experts say the best early-warning systems are ones that start years before the wind picks up and raindrops begin to fall, alerting people who live in vulnerable areas who might be prone to more threats in a climate-charged world.

Following Harvey, Klockow was named to a team of external scientists who will study the National Weather Service’s performance and look for ways to improve. They could start with better flood warnings, she says. “It’s like peering into a black box,” she says. “We give people almost nothing.”

In part, that’s a consequence of insufficient flood-zone maps. Even though rainstorms are getting more intense as the climate warms, FEMA sticks to historical flood data to determine which neighborhoods are required to purchase flood insurance — a policy that’s already leading to skyrocketing losses from floods. A recent study showed that 75 percent of the flood losses in Houston between 1999 and 2009 fell outside designated 100-year flood zones.

If residents don’t know their home is at risk of flooding, they’re less likely to consider that it might, even when a major storm is forecast. So it’s no surprise that, after floods, people report being caught by surprise.

How to keep them from getting surprised? Talk plainly.

There’s evidence that giving people unambiguous information can help move them to action. Recent research has shown that people often need to see the storm with their own eyes before they take cover. They need to see neighbors boarding up their houses before they do the same.

Read, the former National Hurricane Center director, says the same thing applies to him, despite his years of forecasting experience. “Most people, including myself if I’m really honest about it, are in denial that the bad thing will happen to you.”

Before Hurricane Katrina hit the New Orleans area in 2005, the National Weather Service issued a blunt statement that promised “certain death” should anyone be trapped outside unprotected. A post-storm analysis credited that warning with spurring an evacuation rate of more than 90 percent. Read says that’s why the Weather Service is shifting its focus toward making impending storms feel as real as possible to those in its path.

Forecasters need to “personalize the threat,” he says.

Klockow says that she’d like to see flood warnings take a personal approach, too. During a storm, an overlay in Google Street View could show you how high the water is rising in your neighborhood and re-route you away from flooded roads to get you home safely.

The tools to make that happen already exist. Several companies and local governments have already developed mapping tools that to warn of impending floods. North Carolina’s Flood Inundation Mapping and Alert Network relies on 500 measurement stations across the state that transmit their readings back to a central database. When conditions are ripe for flooding, the system’s software estimates possible consequences and alerts emergency managers.

This budding technology, integrated with databases of rescue supplies, could help FEMA figure out where to put aid and supplies before they’re needed.

Other organizations are working on an initiative called “forecast-based financing.” The idea is to allocate money for clearing out storm drains, as well as distributing first aid and water filtration systems, in the days ahead of a storm. Already tested in Uganda, Peru, Bangladesh and other countries, this innovation is now in the process of being scaled up worldwide. It could help organizations like the American Red Cross craft appeals for donations in advance, instead of relying on scenes of devastation after disaster strikes.

All of these efforts and ideas show a lot of promise. Yet even as forecasters have come to understand the importance of developing better advance-warning techniques, their ability to undertake those efforts is being undercut by a White House hostile to funding science.

Earlier this year, along with recommending that Congress gut funding for NOAA, President Trump proposed an 11 percent cut from the National Science Foundation’s budget, slashing funds from the institution behind much of the country’s basic scientific research. If Congress agrees, it would be the first budget cut in the foundation’s 67-year history.

At the National Weather Service, the Washington Post recently reported that the agency couldn’t fill 216 vacant positions as a result of a Trump-imposed hiring freeze. As a result, meteorologists were working double shifts when hurricane after hurricane hit last month and covering for each other from afar.

A forecast center in Maryland, for example, provided days of backup to the National Hurricane Center as hurricanes spun toward shore. National Weather Service meteorologists at the San Juan, Puerto Rico, office complained of “extreme fatigue.” Colleagues in Texas stepped in to give them breaks.

The threat of budget cuts is already crimping federally funded disaster research. A few days after Harvey struck Texas, the Colorado-based National Center for Atmospheric Research — one of the country’s top meteorological research institutions — cut entire sections of its staff focused on the human dimensions of disasters, including impact forecasting.

In an all-staff meeting on Aug. 30, the center’s director explained that the anticipation of tighter budgets forced the decision.

Antonio Busalacchi, president of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, which oversees the center, called the cuts “strategic reinvestments” in a statement to Grist. He said the money saved would be reallocated to “the priority areas of computer models, observing tools, and supercomputing.”

But researchers at the center, called NCAR, say the layoffs will hurt efforts to make forecasts more human-focused and effective.

“Our whole group was cut,” says Emily Laidlaw, an environmental scientist at NCAR, whose work focuses on understanding what puts people at risk from climate change and climate-related disasters. “I would absolutely say that these cuts make people less safe.”

Read, the former hurricane center chief, says increases in supercomputing power shouldn’t come at the expense of developing forecasts that work better for people.

“You can’t drop one for the other,” he says.

The cuts to the National Center for Atmospheric Research will result in the loss of 18 jobs. That may not sound like a lot, but consider that these were some of the only scientists in the United States working to prepare our country’s system for predicting disasters in an era of rapid change.

In that context, the recent revolution in meteorology and pitfalls in preparedness become a powerful metaphor: We know that if we stick to our current course, the future will be bleak. Acting on the forecast of a warmer planet in a way that helps us to usher in a safer and more prosperous future is completely possible, and the stakes keep getting higher.

One-third of the U.S. economy, some $3 trillion per year, is subject to fluctuations in the weather, and millions of people endure weather disasters every year — a number that keeps going up as climate change boosts the frequency and intensity of storms.

Despite excellent weather forecasts, hundreds of people have lost their lives, and billions of dollars in economic value have been lost during this year’s record-breaking hurricane season. In some especially hard-hit places, like Barbuda, Dominica, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, recovery will take years, or longer.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Get people out of a hurricane’s path, put aid workers and supplies in the right place, and a raging storm might not lead to a catastrophe.

We are living in a golden age for meteorology, but we haven’t yet mastered what really matters: knowing in advance exactly how specific extreme weather events are likely to affect our lives. Getting that right could usher in a new era of disaster prevention, rather than the current model of disaster response.

Dark matter: The mystery substance in most of the universe

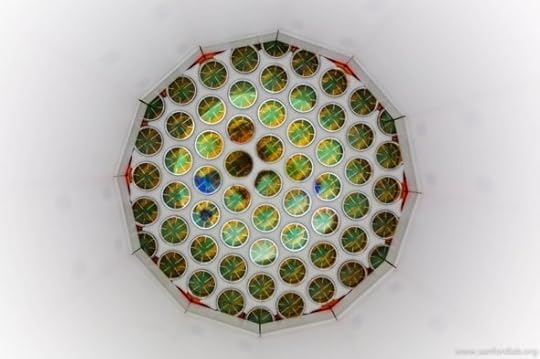

Sensors on the Large Underground Xenon dark matter detector can register the emission of just a single photon from a dark matter interaction within the detector's giant xenon tank. So far, however, no signs of dark matter have been seen. (Credit: Matt Kapust, Sanford Underground Research Facility)

The past few decades have ushered in an amazing era in the science of cosmology. A diverse array of high-precision measurements has allowed us to reconstruct our universe’s history in remarkable detail.

And when we compare different measurements – of the expansion rate of the universe, the patterns of light released in the formation of the first atoms, the distributions in space of galaxies and galaxy clusters and the abundances of various chemical species – we find that they all tell the same story, and all support the same series of events.

This line of research has, frankly, been more successful than I think we had any right to have hoped. We know more about the origin and history of our universe today than almost anyone a few decades ago would have guessed that we would learn in such a short time.

But despite these very considerable successes, there remains much more to be learned. And in some ways, the discoveries made in recent decades have raised as many new questions as they have answered.

One of the most vexing gets at the heart of what our universe is actually made of. Cosmological observations have determined the average density of matter in our universe to very high precision. But this density turns out to be much greater than can be accounted for with ordinary atoms.