Lily Salter's Blog, page 206

December 18, 2017

Sarah Palin’s son charged for alleged attack on his father

Track Palin (Credit: Getty/Justin Sullivan)

Track Palin, the oldest son of former Alaska Governor and Republican vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, was recently arrested at his family home in Wasilla on burglary and assault charges. According to a sworn affidavit obtained by the Anchorage Daily News, Palin’s 28-year-old son “repeatedly hit” Todd Palin, his father.

Sarah Palin called the police on Saturday, December 16, at 8:30pm, and said that Track Palin was “”freaking out and was on some type of medication.” From the report in the Anchorage Daily News:

Track Palin came to the house to confront his father over a truck he wanted to pick up, according to the affidavit. Todd Palin told his son not to come because he’d been drinking and taking pain medication.

“Track told him he was (going to) come anyway to beat his ass,” [reporting officer Adam] LaPointe wrote.

Todd Palin told the officer he got his pistol to “protect his family” and met his son with the gun when he came to the door, according to the affidavit.

Track Palin broke a window and came through it, and put his father on the ground, the report states. He began hitting him on the head.

Todd Palin escaped and left the house. He suffered injuries to his face and head, the officer wrote. He was bleeding from several cuts on his head and had liquid coming from his ear.

This isn’t Track Palin’s first domestic violence charge at the family home. In August 2016, Palin entered into a plea agreement after punching a woman at the same house in Wasilla.

Some of Palin’s detractors might be prone to a sense of schadenfreude at the news, as such an event seems to exemplify conservative hypocrisy. While it’s tempting to see the irony in the family values party violating its self-imposed precepts, Track Palin’s issues are part of a larger, disturbing trend of domestic violence that touches all classes and political sides, and which disproportionately affects veterans (as perpetrators) and women (as victims).

As an Iraq war veteran, Track Palin was tried in Anchorage Veterans Court following his first arrest for punching his girlfriend. Sarah Palin commented at the time that her son “[came] back a bit different” from combat. “They come back hardened,” she added.

A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs study reported that “the prevalence of violence among individuals with PTSD is 7.5% in the US population and 19.5% in post-9/11 Veterans, suggest[ing] that the association between PTSD and violence is especially strong in this Veteran cohort.”

Annually, 10 million women and men are “physically abused by an intimate partner” in the U.S. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, an advocacy group, says that “1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men” will be “victims of [some form of] physical violence by an intimate partner within their lifetime.”

Trump vs. Trump: New national security speech contradicts national security strategy

(Credit: Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

President Donald Trump’s speech on Monday about national security has been met with a decidedly mixed response.

“Optimism has surged. Confidence has returned. With this new confidence, we are also bringing back clarity to our thinking. We are reasserting these fundamental truths: A nation without borders is not a nation. A nation that does not protect prosperity at home cannot protect its interests abroad,” Trump said in his speech. “A nation that is not prepared to win a war is a nation not capable of preventing a war. A nation that is not proud of its history cannot be confident in its future, and a nation that is not certain of its values cannot summon the will to defend them.”

Many aspects of Trump’s speech, and the national security document it outlined (the National Security Strategy), seemed to contradict the president’s own policies.

At one point the document singled out Russia and China for “attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” even though Trump has spent much of his presidency cozying up to Russia, including attempting to lift sanctions imposed by President Barack Obama and calling Russian President Vladimir Putin to thank him for saying kind words about Trump’s economic policies. While the speech echoed these claims, arguing that Russia and China “seek to challenge American influence, values, and wealth,” Trump appeared eager to offset that criticism when he added this anecdote:

Yesterday I received a call from President Putin of Russia thanking our country for the intelligence that our CIA was able to provide them concerning a major terrorist attack planned in St. Petersburg, where many people, perhaps in the thousands, could have been killed. They were able to apprehend these terrorists before the event, with no loss of life. And that’s a great thing, and the way it’s supposed to work. That is the way it’s supposed to work.

As CNN’s Jim Acosta noted, the National Security Strategy document mentioned Russia’s alleged meddling in the 2016 presidential election, which Trump has continued to deny.

“Today, actors such as Russia are using information tools in an attempt to undermine the legitimacy of democracies,” the document pointed out. Trump’s speech, however, made no similar mention.

The National Security Strategy document also claimed that America “must upgrade our diplomatic capabilities to compete in the current environment,” even though Trump has left a number of key State Department posts unstaffed. The president has also had a notoriously poor relationship with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, whom he has repeatedly embarrassed and who arrived noticeably late to the president’s address after hosting the French foreign minister, who publicly criticized Trump’s foreign policy as “a position of retreat.”

Trump’s speech also drew criticism from a wide array of foreign policy pundits.

Former U.S. ambassador to NATO, Nicholas Burns, noted the glaring disconnect between Trump’s words on Monday and his actions during his first year in office:

Contradiction in Trump #NationalSecurityStrategy: his policy of last 12 months a radical departure from every President since WWII. Trump weak on NATO, Russia, trade, climate, diplomacy. U.S. declining as global leader. These actions more revealing than a strategy document.

— Nicholas Burns (@RNicholasBurns) December 18, 2017

The other obvious contradiction in President Trump’s #NationalSecurityStrategy: he needs a strong State Department to implement it. Instead, State and the Foreign Service are being weakened and often sidelined.

— Nicholas Burns (@RNicholasBurns) December 18, 2017

Yet another contradiction in Trump #NationalSecurityStrategy: in nearly every part of the world, foreign leaders believe the U.S. is weakening as the global leader. That is how America First looks to the rest of the world.

— Nicholas Burns (@RNicholasBurns) December 18, 2017

Major contradiction in Trump #NationalSecurityStrategy on Russia—it is a competitor. So, why is he not defending us against Russia’s interference in our election?

— Nicholas Burns (@RNicholasBurns) December 18, 2017

As did Barack Obama’s former national security advisor, Ben Rhodes:

Trump now praising the benefits of partnership with Putin. This is what the strategy says: "Russia aims to weaken US influence in the world and divide us from our allies and partners," their nukes are "the most significant existential threat to the United States"

— Andrew Beatty (@AndrewBeatty) December 18, 2017

As is often the case on foreign policy, Trump is at odds with the views within the government. Foreign governments will put more stock in Trump's words than strategy documents. https://t.co/BZcpw39Vfd

— Ben Rhodes (@brhodes) December 18, 2017

2. And yes, I agree that economic security is national security. But then why are we risking that with a tax bill that adds trillions to the debt – much of which we owe foreign nations we're competing with! This National Security Strategy doesn't help us meet challenges abroad

— Senator Bob Menendez (@SenatorMenendez) December 18, 2017

18 mins in and we get the first mention of the NSS.

— Tom Wright (@thomaswright08) December 18, 2017

He hardly spoke about Russia. One passing mention as a competitor immediately followed by how much he wants partnership. NSS takes a very different tack

— Tom Wright (@thomaswright08) December 18, 2017

This sounds like the foreign policy equivalent of American carnage.

— Katty Kay (@KattyKayBBC) December 18, 2017

Not all of the reactions to Trump’s speech were negative.

In an editorial for Fox News, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich praised it as a rebuke to the post-Cold War foreign policies that “built their strategic efforts around a system of global multilateralism defined by lawyers, diplomats, and elite media.”

He added, “President Trump’s national security speech today should be read by every American who is concerned about national safety (which is the goal of national security).”

There was also this tweet by David Reaboi of Security Studies Group.

Trump’s speech today showed that he’s very much in line with tradition of conservative foreign policy, from Goldwater to Reagan. It’s the Bush folks who were outliers.

— David Reaboi (@davereaboi) December 18, 2017

Taxing the rich to help the poor? What the Bible says isn’t what the GOP says

Paul Ryan (Credit: AP/Susan Walsh)

The new tax reform bill has led to an intense debate over whether it would help or hurt the poor. Tax reform in general raises critical issues about whether the government should redistribute income and promote equality in the first place.

Jews and Christians look to the Bible for guidance about these questions. And while the Bible is clear about aiding the poor, it does not provide easy answers about taxing the rich. But even so, over the centuries biblical principles have provided an understanding on how to help the needy.

The Hebrew Bible and the poor

The Hebrew Bible has extensive regulations that require the wealthy to set aside for the poor a portion of the crops that they grow.

The Bible’s Book of Leviticus states that the needy have a right to the “leftovers” of the harvest. Farmers are also prohibited from reaping the corners of their fields so that the poor can access and use for their own food the crops grown there.

Hebrew Bible.

Darren Larson, CC BY-NC-ND

In Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Bible, there is the requirement that every three years, 10 percent of a person’s produce should be given to “foreigners, the fatherless and widows.”

Helping the poor is a way of “paying rent” to God, who is understood to actually own all property and who provides the rain and sun needed to grow crops. In fact, every seventh year, during the sabbatical year, all debts are forgiven and everything that grows in the land is made available freely to all people. Then, in the great jubilee, celebrated every 50 years, property returns to its original owner. This means that, in the biblical model, no one can permanently hold onto something that finally belongs to God.

Christians and taxes

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says, “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” Jesus thus joins respect for the poor with respect for God. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus also states “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” which is often interpreted as requiring Christians to pay taxes.

Throughout Christian history, taxation has been considered an essential government responsibility.

The Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin drew upon Psalm 72 to argue that a “righteous” government helps the poor.

In 16th-century England, “poor laws” were passed to aid “the deserving poor and unemployed.” The “deserving poor” were children, the old and the sick. By contrast, the “undeserving poor” were beggars and criminals and they were usually put in prison. These laws also shaped early American approaches to social welfare.

The common good

Over the last two centuries, new economic realities have raised new challenges in applying biblical principles to economic life. Approaches not foreseen in biblical times emerged in an attempt to respond to new situations.

The Salvation Army bucket.

Elvert Barnes, CC BY

In the 19th century, organizations like the Salvation Army believed that Christians should go out of the churches and into the streets to care for the destitute. During this period, the United States also saw the rise of the social gospel movement that emphasized biblical ideals of justice and equality. Poverty was considered a social problem that required a comprehensive social – and governmental – response.

The idea that government has an important role to play in human flourishing was made by Pope Leo XIII in his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum. In it, the pope argued that governments should promote “the common good.” Catholicism defines the “common good” as the “conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily.”

While human fulfillment is not just about material comfort, the Catholic Church has always maintained that citizens should have access to food, housing and health care. As the Catholic Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church makes clear, taxation is necessary because government should “harmonize” society in a just way.

And when it comes to taxes, no one should pay more or less than they are able. As Pope John XXIII wrote in 1961, taxation must “be proportioned to the capacity of the people contributing.”

In other words, believing that helping the poor is simply an individual or private responsibility ignores the scope and complexity of the world we live in.

Mercy, not the market

Human life has become more interconnected. In today’s globalized economy, decisions made in the heartland of China impact the American Midwest. But even with this deepening interdependence, by some measures, inequality has risen worldwide. In the United States alone, the top 1 percent possess an increasingly larger share of national income.

What social policy will do the most good?

Fibonacci Blue, CC BY

When it comes to helping the poor in these current times, some argue that cutting taxes on individuals and corporations will stimulate economic growth and create jobs – called the “trickle-down effect,” in which money flows from those at the top of the social pyramid down to lower levels.

Pope Francis, however, argues that “trickle-down” economics places a “crude and naive trust in those wielding economic power.” In the pope’s view, an ethics of mercy, not the market, should shape society.

But given the Jewish and Christian commitment to the poor, the question is perhaps a factual one: What social policy does the most good?

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus taught:

“Give, and you will receive. Your gift will return to you in full.”

At the very least, this means that people should never be afraid to offer up what they have in order to help those in need.

At the very least, this means that people should never be afraid to offer up what they have in order to help those in need.

Mathew Schmalz, Associate Professor of Religion, College of the Holy Cross

More college financial aid is going to the rich

(Credit: Getty/baona)

Maya Portillo started life solidly in the middle class. Both her parents were college graduates, they sent her to a Montessori school, they took family vacations and they owned a house in Tucson, Arizona, filled with the books she loved to read.

Maya Portillo started life solidly in the middle class. Both her parents were college graduates, they sent her to a Montessori school, they took family vacations and they owned a house in Tucson, Arizona, filled with the books she loved to read.

Then, when she was 10, Portillo’s father left, the house was foreclosed on and the recession hit. Her mother was laid off, fell into debt and took Portillo and her two sisters to live a hand-to-mouth existence with their grandparents in Indiana.

“It could have happened to anyone,” said Portillo, who took two jobs after school to pitch in while trying to maintain her grades. “I can’t even begin to describe how hard it was.” She choked up. “It’s really hard to talk about, but when you have to help put food on the table when you’re in high school, it does something to you.”

Portillo recounted this story in a quiet conference room on the pristine hilltop campus of Cornell University, from which she was about to graduate with a major in industrial labor relations and minors in education and equality studies.

Her long path from comfort to poverty and an against-the-odds Ivy League degree gave her firsthand exposure to how even the smartest low-income students often succeed despite, rather than because of, programs widely assumed to help them go to college.

This is happening as tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer-funded and privately provided financial aid, along with money universities and colleges dole out directly, flows to their higher-income classmates.

“There is a very seriously warped view among many Americans, and particularly more affluent Americans, about where the money is actually going,” said Richard Reeves, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution and author of “Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust.”

“They say, look, there’s always other support going to poorer kids,” Reeves said. “Well, there isn’t. There actually isn’t. But the ignorance about where the money is actually going and who benefits from it, that ignorance is really an obstacle to reform around what is, in fact, a reverse distribution.”

It’s a little-known reality that reflects – and, because higher education is a principal route to the middle class, widens – the American income divide. And at the same time that the fight over issues including health care and changes in tax law has reignited the national debate over income inequality, financial aid disparities are getting worse, driven by politics, the pursuit of prestige and policies that have been shifting resources away from students with financial need.

The result? “We’re not helping the right people go to college as much as we should,” said Ron Ehrenberg, a Cornell economist and director of the university’s Higher Education Research Institute.

At least 86,000 more low-income students per year are qualified to attend the most selective universities and colleges than enroll, according to a study by the Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce. On standardized admissions tests, these students score as well as or better than those who do get that privilege.

It’s not because selective institutions can’t afford to help low-income students, the Georgetown study said. The 69 most prestigious universities boast endowments averaging $1.2 billion and posted typical annual budget surpluses of $139 million from 2012 to 2015, the most recent year for which the figures are available.

Cornell has a $6.8 billion endowment and took in $390 million a year more than it spent during that time, the study said. Yet federal data show that 15 percent of its students are low-income, based on whether they qualify for a federal Pell Grant. Nationally, 33 percent of all students are low-income by this measure, the College Board reports.

Children of parents in the top 1 percent of earnings are 77 times more likely to go to an Ivy League college than those whose parents are in the bottom 20 percent, a National Bureau of Education Research study found. “Polishing the privileged,” one policymaker calls this.

But it’s not just Ivy League or even private institutions where the percentages of less well-off students are low. Some taxpayer-supported public universities enroll very small proportions of them. At the University of Virginia, for example, 12 percent of students come from families with incomes low enough to qualify for Pell Grants, federal data show.

It’s not because there aren’t plenty of low-income students who qualify, research by the Institute for Higher Education Policy found. At Pennsylvania State University’s main campus, for example, 15 percent of students are low-income, but the study showed that twice that proportion would meet admissions requirements, meaning Penn State could graduate 900 more lower-income students per year.

If such a change were made by all the universities and colleges that now take fewer lower-income students than they could, the report concluded, 57,500 more low-income students per year would be earning degrees.

“When you look at the way that higher education is financed, subsidized and organized in the United States, your heart sinks just a bit further,” Reeves said. “It takes the inequalities given to it and makes them worse.”

Even low-income students with the highest scores on 10th-grade standardized tests are more than three times less likely to go to top colleges than higher-income students, according to the Education Trust. More than a fifth of those high-achieving low-income students never go to college, while nearly all of their wealthier counterparts do.

In some cases, that’s because low-income prospects are discouraged by the cost. It’s a legitimate worry. Even though – as institutions argue – low-income students may be eligible for financial aid they’re not aware of, that money seldom covers the full price of their educations or enough of it that they could afford the rest. Portillo, for example, got comparatively generous help but still had to pay $3,500 a year she didn’t have, plus other expenses, such as mandatory health insurance.

“For someone like me, $3,500 is everything,” she said. “It’s a lot of money.”

So she borrowed $21,000 over the course of her education, which she’ll have to repay out of her salary working at a New York City charter school for low-income students.

“Oof,” she said, thinking about the day her loans come due. “I’m not coming out of here debt-free, as they kind of market themselves.”

Students who don’t need the money, meanwhile, keep getting more of it. At private universities, students from families with annual earnings of $155,000-plus receive an average of $5,800 more per year in financial aid than a federal formula says they need to pay tuition; at public universities, they get $1,810 more than they need, according to the College Board.

College is expensive even for the wealthiest of families, of course, and even more so if they have children close to each other in age or live in places with high costs of living, Ehrenberg said. But those are families whose kids would “absolutely” go to college without such help, he said.

This system has evolved because, with enrollment in decline, colleges and universities are vying for a shrinking supply of students – especially for students whose parents can pay at least some of the tuition, whom they lure by offering discounts and financial aid.

Cornell sophomore Aleks Stajkovic benefited from that strategy. He got financial aid he said he didn’t really need. “I know I’m on a bunch of scholarships and stuff,” he said, studying in the atrium of a grand century-old building on the university’s stately arts quadrangle. “It’s just like a supplement.”

He would have been able to afford Cornell without it, Stajkovic said. “For sure. I definitely would have. And that’s the sad thing – there’s kids that need that.”

All of this means that, in spite of promises from policymakers, politicians and colleges themselves to help the least-wealthy students, the net price of a higher education after discounts and financial aid is rising much faster for them than for the wealthiest ones. While higher-income students still pay more overall, federal data show, since 2012, the net price for the poorest students at Cornell has increased four and a half times faster than for the richest.

Cornell wouldn’t talk about these issues. A spokeswoman said no one at the university was available to discuss them at any time over a three-week period.

A mile away at smaller Ithaca College, however – which has one-twentieth as big of an endowment as Cornell but enrolls a larger proportion of low-income undergraduates – Student Financial Services Director Lisa Hoskey said all higher education institutions have to deal with the complicated calculus of attracting enough families that can pay to keep their campuses going.

“That balance is always tricky,” said Hoskey, the daughter of a factory worker who depended on financial aid herself to go to college. “I know people don’t often think that there’s a bottom line, but there is. And so do we help more people with less money or do we help less people with more money?”

She said: “If I had my way, if we could meet need, I would absolutely love to do that. We can’t.”

Wealthier families now have come to expect financial aid, and they negotiate for more – something lower-income ones without college-going experience may not know they can do – said Hoskey, on whose office wall hang thank-you notes from students she’s helped.

“Most people will tell you that financial aid is a privilege for those who earn it – until it becomes their own child, and then it’s a right,” she said. Parents who understand the mystifying process “try to maximize the benefits that they can receive. And I think some people are more knowledgeable about how to do that.”

Portillo gets that. “It’s like a business, right?” she said. “I understand where the university is coming from. At the same time, it’s difficult, as somebody who is low-income,” to pay for college without more help.

Colleges’ shifting of some of their financial aid to higher-income students who could kick in toward salaries, facilities and other things means taxpayer-supported government policies are largely left to support low-income ones. But those policies, too, disproportionately help the wealthy, often through hard-to-see tax subsidies.

“These programs do not get at basic public policy issues, which is that if you’re a bright kid coming from a relatively low-income family, your chances of enrolling in and eventually completing college are much, much lower than a less-talented student coming from a wealthy family,” Ehrenberg said.

It starts with savings. People who set up college savings accounts, called 529 plans, get $2 billion a year worth of federal tax deductions – projected by the Treasury Department to double to $4 billion a year by 2026. Yet the department says almost all of these benefits go to upper-income families that would send their kids to college even without them. Only 1 in 5 families earning under $35,000 a year even knows about 529 plans, a survey by the investment firm Edward Jones found. States forgo at least an additional $265 million in their own tax breaks for holders of 529 plans, according to the Brookings Institution.

Once they pay for college, Americans are eligible for federal tuition tax breaks. But those breaks also disproportionately benefit higher-income students and have grown to exceed the amount spent annually on Pell Grants for lower-income ones. The tax deductions cost the federal government $35 billion a year in forgone revenue, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. That’s 13 times more than in 1990, even when adjusted for inflation.

More than a fifth of the money provided under the principal deduction, the American Opportunity Tax Credit, goes to families earning between $100,000 and $180,000 per year, the Congressional Research Service found. It also found that 93 percent of recipients would have gone to college without it.

Other funding for students is also unequally applied. Portillo earned some cash toward her expenses by getting a work-study job on campus, part of a nearly $1 billion federal financial aid program that pays students for jobs such as shelving library books and busing tables. But because of a more than 50-year-old formula under which work-study money is distributed, it skews to more prestigious private universities with higher-income students.

These schools enroll 14 percent of undergraduates but get 38 percent of work-study money, while community colleges – which take almost half of all students, many of them low-income – get 20 percent, according to the Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

A student at a private university from a family in the top quarter of income is more likely to get work-study money than a student at a community college from the bottom quarter.

“Lots of higher education policies are built in a way that would win support from middle- and even upper-income taxpayers, and they were not really thought about as, ‘Will this really increase the number of people going to college?’ ” Ehrenberg said. “If I were a social planner, we would be using our resources to help support the people who would not be able to go to college.”

The Trump administration has proposed cutting work-study spending nearly in half.

Employer tuition assistance and private scholarships from Rotary clubs and chambers of commerce, too, benefit wealthier people more than poorer ones, who often don’t know about the aid or whose schools don’t have enough college counselors to help them get it. There is more than $17 billion available annually from such sources, the College Board reports; more than 10 percent goes to families earning $106,000 and up, and about 60 percent goes to those with incomes above $65,000, the U.S. Department of Education calculates.

States also provide more than $10 billion in financial aid to students, according to the College Board. But as they try to keep top students from moving away, the proportion of that money being given out based on measures other than need has risen from zero, in the early 1980s, to nearly a quarter of state financial aid today.

Experts say that even “free college” in states including New York – where it eventually will be extended for state schools to children of families with earnings of up to $125,000 – is likely to benefit wealthier students more than lower-income ones. That’s because it kicks in only after students already have exhausted all of their other financial aid. Students from higher-earning families who don’t qualify for things such as federal Pell Grants will end up getting bigger breaks than lower-income students who do.

In Oregon, which has made community college free, students from families in the top 40 percent of income got 60 percent of the free-tuition money, the state’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission found. Oregon officials have since have changed the eligibility requirements, disqualifying the wealthiest families from the program.

Unsurprisingly, given these trends, the proportion of low-income people getting degrees is declining while the proportion of higher-income ones continues to go up. Students from higher-income families today are nearly nine times more likely to earn bachelor’s degrees by the time they’re 24 than students from lower-income ones, up from about seven times more likely in 1970, according to the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education.

Those low-income students who do make it into college are much more likely to enroll at for-profit universities, where graduation rates are the worst in higher education, or thinly stretched regional public ones. At community colleges, which spend less per student than many public primary and secondary schools and where the odds of graduating are also comparatively low, about 4 in 10 of the students are low-income, according to the American Association of Community Colleges.

The policies perpetuating this aren’t likely to change in the current political climate, experts said.

“The system is in danger of becoming trapped in a kind of horrible anti-egalitarian equilibrium,” Reeves said. “I see that getting worse instead of better. The only hope, I think, is if the institutions themselves and the leaders of those institutions – who I think at some level are committed to the ideals of more opportunity – can find a way to alter the equilibrium themselves.”

As hard as it was for her to afford, Portillo hugely values her Cornell degree.

“I feel so lucky, because I know 10 other kids just like me who struggled the same with low socioeconomic status and couldn’t get that spot because there aren’t enough spots for people like us,” she said quietly. “That’s not based on how hard they work. It’s based on how much money they have. And that is heartbreaking.”

A Trumpian bonanza: We’ve never seen as much special ops as we do now

(Credit: AP Photo/Bullit Marquez)

“We don’t know exactly where we’re at in the world, militarily, and what we’re doing,” said Senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, in October. That was in the wake of the combat deaths of four members of the Special Operations forces in the West African nation of Niger. Graham and other senators expressed shock about the deployment, but the global sweep of America’s most elite forces is, at best, an open secret.

Earlier this year before that same Senate committee — though Graham was not in attendance — General Raymond Thomas, the chief of U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), offered some clues about the planetwide reach of America’s most elite troops. “We operate and fight in every corner of the world,” he boasted. “Rather than a mere ‘break-glass-in-case-of-war’ force, we are now proactively engaged across the ‘battle space’ of the Geographic Combatant Commands… providing key integrating and enabling capabilities to support their campaigns and operations.”

In 2017, U.S. Special Operations forces, including Navy SEALs and Army Green Berets, deployed to 149 countries around the world, according to figures provided to TomDispatch by U.S. Special Operations Command. That’s about 75% of the nations on the planet and represents a jump from the 138 countries that saw such deployments in 2016 under the Obama administration. It’s also a jump of nearly 150% from the last days of George W. Bush’s White House. This record-setting number of deployments comes as American commandos are battling a plethora of terror groups in quasi-wars that stretch from Africa and the Middle East to Asia.

“Most Americans would be amazed to learn that U.S. Special Operations Forces have been deployed to three quarters of the nations on the planet,” observes William Hartung, the director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy. “There is little or no transparency as to what they are doing in these countries and whether their efforts are promoting security or provoking further tension and conflict.”

Growth Opportunity

America’s elite troops were deployed to 149 nations in 2017, according to U.S. Special Operations Command. The map above displays the locations of 132 of those countries; 129 locations (in blue) were supplied by U.S. Special Operations Command; 3 locations (in red) — Syria, Yemen and Somalia — were derived from open-source information.

Photo Credit: Nick Turse

“Since 9/11, we expanded the size of our force by almost 75% in order to take on mission-sets that are likely to endure,” SOCOM’s Thomas told the Senate Armed Services Committee in May. Since 2001, from the pace of operations to their geographic sweep, the activities of U.S. Special Operations forces (SOF) have, in fact, grown in every conceivable way. On any given day, about 8,000 special operators — from a command numbering roughly 70,000 — are deployed in approximately 80 countries.

“The increase in the use of Special Forces since 9/11 was part of what was then referred to as the Global War on Terror as a way to keep the United States active militarily in areas beyond its two main wars, Iraq and Afghanistan,” Hartung told TomDispatch. “The even heavier reliance on Special Forces during the Obama years was part of a strategy of what I think of as ‘politically sustainable warfare,’ in which the deployment of tens of thousands of troops to a few key theaters of war was replaced by a ‘lighter footprint’ in more places, using drones, arms sales and training, and Special Forces.”

The Trump White House has attackedBarack Obama’s legacy on nearly all fronts. It has undercut, renounced, or reversed actions of his ranging from trade pacts to financial and environmental regulations to rules that shielded transgender employees from workplace discrimination. When it comes to Special Operations forces, however, the Trump administration has embraced their use in the style of the former president, while upping the ante even further. President Trump has also provided military commanders greater authority to launch attacks in quasi-war zones like Yemen and Somalia. According to Micah Zenko, a national security expert and Whitehead Senior Fellow at the think tank Chatham House, those forces conducted five times as many lethal counterterrorism missions in such non-battlefield countries in the Trump administration’s first six months in office as they did during Obama’s final six months.

A Wide World of War

U.S. commandos specialize in 12 core skills, from “unconventional warfare” (helping to stoke insurgencies and regime change) to “foreign internal defense” (supporting allies’ efforts to guard themselves against terrorism, insurgencies, and coups). Counterterrorism — fighting what SOCOM calls violent extremist organizations or VEOs — is, however, the specialty America’s commandos have become best known for in the post-9/11 era.

In the spring of 2002, before the Senate Armed Services Committee, SOCOM chief General Charles Holland touted efforts to “improve SOF capabilities to prosecute unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense programs to better support friends and allies. The value of these programs, demonstrated in the Afghanistan campaign,” he said, “can be particularly useful in stabilizing countries and regions vulnerable to terrorist infiltration.”

Over the last decade and a half, however, there’s been little evidence America’s commandos have excelled at “stabilizing countries and regions vulnerable to terrorist infiltration.” This was reflected in General Thomas’s May testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee. “The threat posed by VEOs remains the highest priority for USSOCOM in both focus and effort,” he explained.

However, unlike Holland who highlighted only one country — Afghanistan — where special operators were battling militants in 2002, Thomas listed a panoply of terrorist hot spots bedeviling America’s commandos a decade and a half later. “Special Operations Forces,” he said, “are the main effort, or major supporting effort for U.S. VEO-focused operations in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, across the Sahel of Africa, the Philippines, and Central/South America — essentially, everywhere Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are to be found.”

Officially, there are about 5,300 U.S. troops in Iraq. (The real figure is thought to be higher.) Significant numbers of them are special operators training and advising Iraqi government forces and Kurdish troops. Elite U.S. forces have also played a crucial role in Iraq’s recent offensive against the militants of the Islamic State, providing artillery and airpower, including SOCOM’s AC-130W Stinger II gunships with 105mm cannons that allow them to serve as flying howitzers. In that campaign, Special Operations forces were “thrust into a new role of coordinating fire support,” wrote Linda Robinson, a senior international policy analyst with the RAND Corporation who spent seven weeks in Iraq, Syria, and neighboring countries earlier this year. “This fire support is even more important to the Syrian Democratic Forces, a far more lightly armed irregular force which constitutes the major ground force fighting ISIS in Syria.”

Special Operations forces have, in fact, played a key role in the war effort in Syria, too. While American commandos have been killed in battle there, Kurdish and Arab proxies — known as the Syrian Democratic Forces — have done the lion’s share of the fighting and dying to take back much of the territory once held by the Islamic State. SOCOM’s Thomas spoke about this in surprisingly frank terms at a security conference in Aspen, Colorado, this summer. “We’re right now inside the capital of [ISIS’s] caliphate at Raqqa [Syria]. We’ll have that back soon with our proxies, a surrogate force of 50,000 people that are working for us and doing our bidding,” he said. “So two and a half years of fighting this fight with our surrogates, they’ve lost thousands, we’ve only lost two service members. Two is too many, but it’s, you know, a relief that we haven’t had the kind of losses that we’ve had elsewhere.”

This year, U.S. special operators were killed in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, and the Sahelian nations of Niger and Mali (although reports indicate that a Green Beret who died in that country was likely strangled by U.S. Navy SEALs). In Libya, SEALs recently kidnapped a suspect in the 2012 attacks in Benghazi that killed four Americans, including Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens. In the Philippines, U.S. Special Forces joined the months-long battle to recapture Marawi City after it was taken by Islamist militants earlier this year.

And even this growing list of counterterror hotspots is only a fraction of the story. In Africa, the countries singled out by Thomas — Somalia, Libya, and those in the Sahel — are just a handful of the nations to which American commandos were deployed in 2017. As recently reported at Vice News, U.S. Special Operations forces were active in at least 33 nations across the continent, with troops heavily concentrated in and around countries now home to a growing number of what the Pentagon’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies calls “active militant Islamist groups.” While Defense Department spokeswoman Major Audricia Harris would not provide details on the range of operations being carried out by the elite forces, it’s known that they run the gamut from conducting security assessments at U.S. embassies to combat operations.

Data provided by SOCOM also reveals a special ops presence in 33 European countries this year. “Outside of Russia and Belarus we train with virtually every country in Europe either bilaterally or through various multinational events,” Major Michael Weisman, a spokesman for U.S. Special Operations Command Europe, told “TomDispatch.”

For the past two years, in fact, the U.S. has maintained a Special Operations contingent in almost every nation on Russia’s western border. “[W]e’ve had persistent presence in every country — every NATO country and others on the border with Russia doing phenomenal things with our allies, helping them prepare for their threats,” said SOCOM’s Thomas, mentioning the Baltic states as well as Romania, Poland, Ukraine, and Georgia by name. These activities represent, in the words of General Charles Cleveland, chief of U.S. Army Special Operations Command from 2012 to 2015 and now the senior mentor to the Army War College, “undeclared campaigns” by commandos. Weisman, however, balked at that particular language. “U.S. Special Operations forces have been deployed persistently and at the invitation of our allies in the Baltic States and Poland since 2014 as part of the broader U.S. European Command and Department of Defense European Deterrence Initiative,” he told TomDispatch. “The persistent presence of U.S. SOF alongside our Allies sends a clear message of U.S. commitment to our allies and the defense of our NATO Alliance.”

Asia is also a crucial region for America’s elite forces. In addition to Iran and Russia, SOCOM’s Thomas singled out China and North Korea as nations that are “becoming more aggressive in challenging U.S. interests and partners through the use of asymmetric means that often fall below the threshold of conventional conflict.” He went on to say that the “ability of our special operators to conduct low-visibility special warfare operations in politically sensitive environments make them uniquely suited to counter the malign activities of our adversaries in this domain.”

U.S.-North Korean saber rattling has brought increased attention to Special Forces Detachment Korea (SFDK), the longest serving U.S. Special Forces unit in the world. It would, of course, be called into action should a war ever break out on the peninsula. In such a conflict, U.S. and South Korean elite forces would unite under the umbrella of the Combined Unconventional Warfare Task Force. In March, commandos — including, according to some reports, members of the Army’s Delta Force and the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 — took part in Foal Eagle, a training exercise, alongside conventional U.S. forces and their South Korean counterparts.

U.S. special operators also were involved in training exercises and operations elsewhere across Asia and the Pacific. In June, in Okinawa, Japan, for example, airmen from the 17th Special Operations Squadron (17th SOS) carried out their annual (and oddly spelled) “Day of the Jakal,” the launch of five Air Force Special Operations MC-130J Commando II aircraft to practice, according to a military news release, “airdrops, aircraft landings, and rapid infiltration and exfiltration of equipment.” According to Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Dube of the 17th SOS, “It shows how we can meet the emerging mission sets for both SOCKOR [Special Operations Command Korea] and SOCPAC [Special Operations Command Pacific] out here in the Pacific theater.”

At about the same time, members of the Air Force’s 353rd Special Operations Group carried out Teak Jet, a joint combined exchange training, or JCET, mission meant to improve military coordination between U.S. and Japanese forces. In June and July, intelligence analysts from the Air Force’s 353rd Special Operations Group took part in Talisman Saber, a biennial military training exercise conducted in various locations across Australia.

More for War

The steady rise in the number of elite operators, missions, and foreign deployments since 9/11 appears in no danger of ending, despite years of worries by think-tank experts and special ops supporters about the effects of such a high operations tempo on these troops. “Most SOF units are employed to their sustainable limit,” General Thomas said earlier this year. “Despite growing demand for SOF, we must prioritize the sourcing of these demands as we face a rapidly changing security environment.” Yet the number of deployments still grew to a record 149 nations in 2017. (During the Obama years, deployments reached 147 in 2015.)

At a recent conference on special operations held in Washington, D.C., influential members of the Senate and House armed services committees acknowledged that there were growing strains on the force. “I do worry about overuse of SOF,” said House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mac Thornberry, a Republican. One solution offered by both Jack Reed, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Republican Senator Joni Ernst, a combat veteran who served in Iraq, was to bulk up Special Operations Command yet more. “We have to increase numbers and resources,” Reed insisted.

This desire to expand Special Operations further comes at a moment when senators like Lindsey Graham continue to acknowledge how remarkably clueless they are about where those elite forces are deployed and what exactly they are doing in far-flung corners of the globe. Experts point out just how dangerous further expansion could be, given the proliferation of terror groups and battle zones since 9/11 and the dangers of unforeseen blowback as a result of low-profile special ops missions.

“Almost by definition, the dizzying number of deployments undertaken by U.S. Special Operations forces in recent years would be hard to track. But few in Congress seem to be even making the effort,” said William Hartung. “This is a colossal mistake if one is concerned about reining in the globe-spanning U.S. military strategy of the post-9/11 era, which has caused more harm than good and done little to curb terrorism.”

However, with special ops deployments rising above Bush and Obama administration levels to record-setting heights and the Trump administration embracing the use of commandos in quasi-wars in places like Somalia and Yemen, there appears to be little interest in the White House or on Capitol Hill in reining in the geographic scope and sweep of America’s most secretive troops. And the results, say experts, may be dire. “While the retreat from large ‘boots on the ground’ wars like the Bush administration’s intervention in Iraq is welcome,” said Hartung, “the proliferation of Special Operations forces is a dangerous alternative, given the prospects of getting the United States further embroiled in complex overseas conflicts.”

December 17, 2017

Think you know what your kids are doing online? Think again

(Credit: Getty/sturti)

When parents say that they know what their teens are doing online, are they kidding themselves? According to a survey by Common Sense Media and SurveyMonkey, parents can track, follow, and check in with their teens — and still be out of touch with reality. The disconnect may come from the time-honored tension between parents’ impulse to protect their kids and teens’ desire for independence. When parents hear horror stories about what kids put on Snapchat and other social media platforms, they double down on their efforts to be more involved. But to teens, this feels intrusive, and they find ways to tiptoe around the issues or appease their parents. To better understand if parents and teens are on the same page about teens’ online behaviors, check out the key findings from the survey:

Parents feel they know what teens are doing online, but teens don’t think so: More than half of parents with teenagers age 14 to 17 say they are “extremely” or “very aware” of what their kids are doing online; just 30 percent of teens say their parents are “extremely” or “very aware” of what they’re doing online.

Parents are tracking their teens more than teens know: 26 percent of parents say they use a tracking or monitoring device or service to learn what their teens are doing online, while only 15 percent of kids think their parents do so.

Teens are more on the level than their parents give them credit for: 34 percent of parents believe their teen has hidden online accounts, but only 27 percent of teens say they do.

Parents are most nervous about Snapchat: Snapchat is the app parents are most concerned about (29 percent), much more than Facebook (16 percent). Only 6 percent of parents are nervous about Instagram. Some parents aren’t nervous at all about the apps their teens use; Twenty percent say that “no apps and websites are concerning.”

Older parents are less aware of what their teens are doing online: Younger parents are more likely to say that they are more aware of what their teens are doing online. Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of parents age 18 to 34 say they are “extremely” or “very aware” of what their teens are doing online; under half of parents 55 and older say the same.

Facebook and Twitter aren’t cool: More than three-quarters of teens use Instagram and Snapchat, but just half use Facebook and fewer use Twitter.

Parents follow their kids on Facebook, but not much on other platforms: A large majority of teens who use Facebook are friends with their parents on the platform. Fewer of those who use Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter follow or are friends with their parents on those platforms.

Given that kids will almost certainly be doing things online that their parents won’t know about, it’s important to talk early and often about being safe online. Just because a teen behaves one way on Facebook does not mean they behave the same way on Intagram or Snapchat, platforms where parents are less likely to be. There are also partial technical solutions to keeping kids safe, like setting up parental controls and checking device privacy settings, but they’re not foolproof.

If you want to get a better grasp on what your kids are doing, just ask! Have your teen take you on a tour of their platforms so they can show you their privacy settings and give you examples of how social media makes them feel. Even surly teens may be happy to assume the role of an expert and do what they can to ease your fears. And if it doesn’t, it’s at least an opportunity to open a conversation about what can be done better.

Methodology

This Common Sense Media/SurveyMonkey online poll was conducted Sept. 20 – Oct. 12, 2017, among a national sample of 884 teens age 14 to 17 and 3,282 parents of teens. Respondents for this survey were selected from the nearly 3 million people who take surveys on the SurveyMonkey platform each day. The modeled error estimate for this survey is plus or minus 2 percentage points for all adults, 2.5 percentage points for parents of teens, and 3.5 percentage points for teens. Data have been weighted to reflect the demographic composition of the United States in terms of age, race, sex, education, and geography using the Census Bureau’s American Community.

The 3 states best positioned to legalize marijuana in 2018

(Credit: Getty/Juanmonino)

Election Day 2016 was a big day for marijuana. Voters in California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada all supported successful legalization initiatives, doubling the number of states to have done so since 2012 and more than quadrupling the percentage of the national population that now lives in legal marijuana states.

Marijuana momentum was high, national polling kept seeing support go up and up, and 2017 was expected to see even more states jump on the weed bandwagon. That didn’t happen.

There are two main reasons 2017 was a dud for pot legalization: First, it’s an off-off-year election year, and there were no legalization initiatives on the ballot. Second, it’s tough to get a marijuana legalization bill through a state legislature and signed by a governor. In fact, it’s so tough it hasn’t happened yet.

But that doesn’t mean it isn’t going to happen next year. Several states where legislative efforts were stalled last year are poised to get over the top in the coming legislative sessions, and it looks like a legalization initiative will be on the ballot in at least one state—maybe more.

There are other states where legalization is getting serious attention, such as Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island, but they all have governors who are not interested in going down that path, and that means a successful legalization bill faces the higher hurdle of winning with veto-proof majorities. Similarly, there are other states where legalization initiatives are afoot, such as Arizona, North Dakota and Ohio, but none of those have even completed signature gathering, and all would face an uphill fight. Still, we could be pleasantly surprised.

Barring pleasant surprises, here are the three states that have the best shot at legalizing pot in 2018.

1. Michigan

Michigan voters shouldn’t have to wait on the state legislature to act because it looks very likely that a legalization initiative will qualify for the ballot next year. The Michigan Coalition to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol has already completed a petition campaign and handed in more than 365,000 raw signatureslast month for its legalization initiative. It hasn’t officially qualified for the ballot yet, but it only needs 250,000 valid voter signatures to do so, meaning it has a rather substantial cushion.

If the measure makes the ballot, it should win. There is the little matter of actually campaigning to pass the initiative, which should require a million or two dollars for TV ad buys and other get-out-the-vote efforts, but with the Marijuana Policy Project on board and some deep-pocketed local interests as well, the money should be there.

The voters already are there: Polling has shown majority support for legalization for several years now, always trending up, and most recently hitting 58% in a May Marketing Resource Group poll.

2. New Jersey

Outgoing Gov. Chris Christie (R) was a huge obstacle to passage of marijuana legalization, but he’s on his way out the door, and his replacement, Gov.-Elect Phil Murphy (D), has vowed to legalize marijuana within 100 days of taking office next month.

Legislators anticipating Christie’s exit filed legalization bills earlier this year, Senate Bill 3195 and companion measure Assembly Bill 4872. State Senate President Stephen Sweeney (D) has also made promises, vowing to pass the bill within the first three months of the Murphy administration, and hearings are set for both houses between January and March.

But it’s not a done deal. There is some opposition in the legislature, and marijuana legalization foes will certainly mobilize to defeat it at the statehouse. It will also be the first time the legislature seriously considers legalization. Still, legalization has some key political players backing it. Other legislators might want to listen to their constituents: A September Quinnipiac poll had support for legalization at 59%.

3. Vermont

A marijuana legalization bill actually passed the legislature last year—a national first—only to be vetoed by Gov. Phil Scott (D) over concerns around drugged driving and youth use. Legislators then amended the bill to assuage Scott’s concerns and managed to get the amended bill through the Senate, only to see House Republicans refuse to let it come to a vote during the truncated summer session.

But that measure, House Bill 511, will still be alive in the second year of the biennial session, and Gov. Scott has said he is still willing to sign the bill. House Speaker Mitzi Johnson (D) is also on board, and the rump Republicans won’t be able to block action next year.

Johnson said she will be ready for a vote in early January and expects the bill to pass then. Vermont would then become the first state to free the weed through the legislative process.

Trump’s right about one thing: The Senate should end its 60-vote majority

(Credit: AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

As the dramatic and traumatic first year of the Trump presidency nears the finish line, with major legislative struggles over tax legislation and the budget, it is easy to overlook other important political events.

One such development is essential to both the tax reform package, which would be Trump’s only significant legislative achievement to date, and the less noted but spectacular success the president has had with judicial nominations.

In both cases success has depended on procedures created to negate the Senate filibuster, which is better thought of as minority obstruction.

The question now is, should the Senate move even further toward being a legislative body characterized by majority rule rather than minority obstruction?

Many Democrats, including me, might resist anything that helps President Donald Trump and his GOP congressional majority. Yet as a scholar of the Senate and advocate of responsible government, I believe the end of the 60-vote Senate would nonetheless be a good thing for the country — and conform to what the founders intended.

Limited nuclear warfare in the Senate

On Nov. 21, 2013 the Senate, under Democratic control, decided by a 52-48 vote that the “vote on cloture under Rule XXII for all nominations other than for the Supreme Court of the United States is by majority vote.”

These few and perhaps obscure words embodied the most important change in Senate standing rules — or, to be precise, in their interpretation — since at least 1975.

Rule XXII is the Senate rule that defines cloture — a motion to bring debate to a close — and requires a supermajority of at least 60 votes on most matters under consideration. The 60-vote threshold is what empowers filibusters or minority obstruction and can prevent a final vote on legislation. The 2013 decision eliminated that barrier for nearly all nominations to the executive and judicial branches. This allowed Democrats to confirm a significant number of nominations after cloture was invoked with a simple majority vote.

Just over three years later, on April 6, 2017, the Senate, under GOP control and with exclusively Republican support, voted by the same margin to apply the same interpretation to nominations to the Supreme Court. The immediate result, of course, was the easy confirmation of Neil Gorsuch.

What this means

These decisions are significant for four reasons.

First, an entire category of Senate business, its constitutional duty to give “advice and consent” on presidential nominations, was protected from obstruction by the minority.

Second, only a few years apart, a majority from each party voted to categorically restrict the filibuster.

Third, in each case the Democratic or Republican majority employed the same controversial method — often referred to as the “nuclear option” or “constitutional option” — to make these significant changes in a standing rule of the Senate.

Instead of amending the wording of the standing rule, the majority called for a parliamentary interpretation and ruling, which requires only a simple majority vote to sustain or overturn.

Finally, this change will likely endure now that it has been sustained by majorities of both Republicans and Democrats.

Fast-tracking past the filibuster

Use of the so-called nuclear option was spectacular, controversial and did bring significant change to the Senate. Yet these moves have also been complemented by a different type of limitation on minority obstruction.

Over several decades, Congress has forged and used dozens of legislative “carve-outs” or — to use congressional scholar Molly Reynold’s term — “majoritarian exceptions” that protect specific categories of legislation from minority obstruction in the Senate.

Every legislative carve-out features a time limit on consideration that applies to both chambers. This quashes minority obstruction in the Senate because a simple majority vote will be held at the end of the time restriction. The term “fast-track” is often associated with these provisions that expedite congressional consideration. These include such specifics as approval of trade agreements and the military base closure process. In each case, lawmakers used a “fast-track” procedure to prevent obstruction.

Looming large in this category is the increased use of budget reconciliation for major legislation, such as the final work on passage of the Affordable Care Act, the 2017 attempt to repeal that law and the current Republican tax legislation.

Restoring the Senate’s important but limited role

The 60-vote Senate remains powerful but circumscribed. This threshold for ending debate still applies to most legislation. This includes appropriations bills and most laws in areas such as military policy, the environment or civil rights.

Still, the combination of the legislative carve-outs with the entire category of nominations nevertheless constitutes a serious diminution of supermajority politics.

Following the second nuclear option in 2017, many senators and observers asked whether the Senate might be heading toward the elimination of supermajority cloture entirely. “Let us go no further on this path,” said Minority Leader Chuck Schumer.

A letter signed by a bipartisan group of 61 Senators implored the majority and minority leaders to help them preserve 60 votes for most legislation. Sen. Lindsay Graham, who voted for the 2017 nuclear option, warned that if the Senate does away with the requirement, “that will be the end of the Senate.”

While most senators showed little appetite for further curtailment of supermajority cloture, President Donald Trump was ready to go all the way. Trump has more than once tweeted, with characteristic imprecision, his support for an end to all 60-vote thresholds in the Senate, the first time a president has taken such a stance.

Finish what it started

In this rare instance, I agree with the president.

By creating these restrictions, the Senate has repeatedly recognized that the 60-vote threshold is often dysfunctional and that the costs to effective governance are too high.

The norms that support the supermajority Senate are eroding. And from a constitutional perspective, that’s just fine. Contrary to Graham’s all too common sentiment, a supermajority threshold is not what defines the Senate.

As political scientists and historians have noted over and over again, supermajority cloture is not part of and cannot be derived from the Constitution or any original understanding of the Senate. Elements such as equal representation by the states, six-year terms and a higher age requirement are what distinguish the Senate’s style of deliberation and decision-making from the House.

In fact, although it may seem like the 60-vote filibuster has been with us forever, it’s actually only been around since 1917.

Moreover, the protection of minority interests, often cited as a justification for the filibuster, is a product of the system as a whole — the separate branches, the checks, federalism — not the self-appointed duty of the Senate.

To finish what it started, the Senate could change its rules to allow a simple majority to close debate on any bill, nomination or other matter, while also guaranteeing a minimum period of debate, which would allow the minority position to be voiced and debated.

In so doing the Senate would end its undemocratic pretensions and resume its prescribed and limited role in the system of checks and balances. That would be a good thing no matter which party controls the Senate and regardless of who is, or will be, president.

In so doing the Senate would end its undemocratic pretensions and resume its prescribed and limited role in the system of checks and balances. That would be a good thing no matter which party controls the Senate and regardless of who is, or will be, president.

Daniel Wirls, Professor of Politics, University of California, Santa Cruz

Where have all the good male poets gone?

(Credit: Getty/200mm)

If you look at some of the most popular male poets in the writing community at the moment, you will most likely come across large accounts like r.h Sin, and Atticus. With hundreds of thousands of followers, best-selling poetry books, and a gaggle of fans consistently commenting on their writing as if they were all-knowing enigmas in the literary climate, you’d think that you’d be dealing with men who were speaking out on issues from their point of view — men you could respect, and look up to, for juxtaposing their privilege in the world with the kind of art that spoke for something, that stood out.

However, that is not what you will find.

Instead, the eerie similarity between all of these male poetry accounts, is the fact that they use the female experience to promote themselves. And though their writing seems to reach millions of people, day by day, when are we going to admit that these are not authentic pieces of work being gifted to the world, but rather, formulaic pieces of boy band prose meant to be marketed, and digested by the very population of women they are silencing?

Earlier in the year, one of these writers, r.h Sin, took a hiatus from Twitter because the writing community started to question the credibility of his work. How could someone, who has lived his whole life as a male, write from the female perspective? And when asked this, how could someone, who has become wealthy off of the female experience, completely denounce those same women when they try to educate him on how he has no right to speak on their behalf? Reuben was offended by the backlash. Instead of opening himself up to understanding, in a compassionate way, the reason why some women struggle with his platform, he instead reverted, in a stunning example of male fragility, to calling them “half-witted critics” and to diminishing their concerns. The women who have so eagerly inspired the work that has made him a player in the poetry community, are now, less great than him. Less credible. Less talented. Less. Only worthy enough to be walked on. Ignored. Discredited.

And herein lies another issue. Popular male poetry seems to not only speak on behalf of women, but it also sensationalizes their struggle. Women deal with oppression in many different ways. This is a concept that is coming to the forefront in every climate, whether that is political, educational, occupational, and so on. However, male writers are making money off of the prettiness of their existence.

“There is nothing prettier than a girl in love with every breath she takes.” — Atticus

“She wasn’t bored, just restless between adventures.” — Atticus

“Don’t forget to kiss her often.” — Atticus

Is this all women are meant to be? Listless, and beautiful? Eager to be loved, constantly in need of male affection? If you do not see an issue in those words, let me change them to represent a male.

“There is nothing prettier than a man in love with every breath he takes.” — Atticus

“He wasn’t bored, just restless between adventures.” — Atticus

“Don’t forget to kiss him often.” — Atticus

It feels cheap. It doesn’t resonate, and that is because males have not been illustrated in the media, and in the world for that matter, the same way women have. This is why Julia Roberts will get asked about her beauty routine during important interviews, but George Clooney will not. This is why Brie Larson gets asked about the dress she is wearing on a red carpet, and Leonardo DiCaprio gets asked about global warming, and the state of planetary affairs. When you flip the role, when you change the words to reflect the men who are writing them, suddenly the writing itself doesn’t seem so beautiful. Suddenly, you see it for what it is, and that is why you will never see this scrawled across Atticus’ Instagram feed, or r.h Sin’s Facebook page — because they themselves know that such words are less than marketable.

As a female writer, who is simply just trying to represent my own human experience through my writing, I will not apologize for speaking out against this. I am not afraid of any male with a larger following trying to vilify, discredit, or denounce me. I am not afraid. If there is one thing I have learned about writing in the last few years, it is that people do not want to be told how they feel. They simply just want to represented. So here I am, as a female writer, who lives in this world as a woman, who lives in a world that does not pay her the same as males, who lives in a world where I am statistically not safe from predatory behavior, I am trying to represent other women. I do not need a male to do so.

So please, male poets — stop trying to do so. My voice is loud enough. Let me speak.

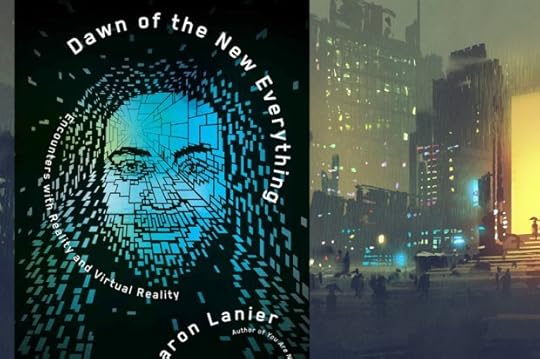

How virtual reality proves we are real

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality by Jaron Lanier (Credit: Henry Holt and Co/Getty/Grandfailure)

Even though it’s finally becoming more widely accessible, a lot of the joy in virtual reality (VR) remains in just thinking about it. One way to think about VR is through surreal thought experiments. Imagine the universe with a person-shaped cavity excised from it. What can we say about the inward-facing surface that surrounds the cavity?

Fourth VR Definition: The substitution of the interface between a person and the physical environment with an interface to a simulated environment.

You can think of an ideal virtual reality setup as a sensorimotor mirror; an inversion of the human body, if you like.

In order for the visual aspect of VR to work, for example, you have to calculate what your eyes should see in the virtual world as you look around. Your eyes wander and the VR computer must constantly, and as instantly as possible, calculate whatever graphic images they would see were the virtual world real. When you turn to look to the right, the virtual world must swivel to the left in compensation, to create the illusion that it is stationary, outside of you and independent.

Back in the early days I used to luxuriate when I described this most basic principle of VR to people who had never heard of it. People just flipped out when they first got it!

Wherever the human body has a sensor, like an eye or an ear, a VR system must present a stimulus to that body part to create an illusory world. The eye needs visual display, for instance, and the ear needs an audio speaker. But unlike prior media devices, every component of VR must function in tight reflection of the motion of the human body.

Fifth VR Definition: A mirror image of a person’s sensory and motor organs, or if you like, an inversion of a person.

Or, to make it more concrete:

Sixth VR Definition: An ever growing set of gadgets that work together and match up with human sensory or motor organs. Goggles, gloves, floors that scroll, so you can feel like you’re walking far in the virtual world even though you remain in the same physical spot; the list will never end.

The ultimate VR system would include enough displays, actuators, sensors, and other devices to allow a person to experience, well, anything. Become any animal or alien, in any environment, doing anything, with effectively perfect realism. Words like “any” show up a lot in VR definitions, but after working with VR, most researchers learn to be suspicious whenever “any” is uttered. What’s wrong with this innocent-seeming little word?

My position is that in a given year, no matter how far we project into the future, the best possible VR system will never achieve complete coverage of all the human senses or measurement of everything there is to be measured from a person. Whatever VR is, it’s always chasing toward an ultimate destination that probably can’t ever be reached. Not everyone agrees with me about that.

Some VR freaks think that VR will eventually become “better” than the human nervous system, so that it wouldn’t make sense to try to improve it anymore. It would then be as good as people could ever appreciate.

I don’t see things that way. One reason is that the human nervous system benefits from hundreds of millions of years of evolution and can tune itself to the quantum limit of reality in special cases already. The retina can respond to a single photon, for instance. When we think technology can surpass our bodies in a comprehensive way, we are forgetting what we know about our bodies and physical reality. The universe doesn’t have infinitely fine grains, and the body is already tuned in as finely as anything can ever be, when it needs to be.

There will always be circumstances in which an illusion rendered by a layer of media technology, no matter how refined, will be revealed to be a little clumsy in comparison to unmediated reality. The forgery will be a

little coarser and slower; a trace less graceful. But that’s not even the best reason to think that our simulations will not surpass our bodies.

When confronted with high-quality VR, we become more discriminating. VR trains us to perceive better, until that latest fancy VR setup doesn’t seem so high-quality anymore. The whole point of advancing VR is to make VR always obsolete.

Through VR, we learn to sense what makes physical reality real. We learn to perform new probing experiments with our bodies and our thoughts, moment to moment, mostly unconsciously. Encountering top-quality VR refines our ability to discern and enjoy physicality. This is a theme I will return to many times.

Our brains are not stuck in place; they’re remarkably plastic and adaptive. We are not fixed targets, but creative processes. If time machines are ever invented, then it would become possible to snatch someone from the present and put that person in a future, highly sophisticated VR setup. And that person would be fooled. Similarly, if we could grab people from the past and put them in our present-day VR systems, they would be fooled.

To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln: You can fool some of the people with the VR of their own time, and all of the people with VR from future times, but you can’t fool all of the people with the VR of their own time.

The reason is that human cognition is in motion and will generally outrace progress in VR.

Seventh VR Definition: A coarser, simulated reality fosters appreciation of the depth of physical reality in comparison. As VR progresses in the future, human perception will be nurtured by it and will learn to find ever more depth in physical reality.

Because of future progress in VR technology, we humans will become ever better natural detectives, learning new tricks to distinguish illusion from reality.

Both today’s natural retinas and tomorrow’s artificial ones will harbor flaws and illusions, for that will always be true for all transducers. The brain will constantly twiddle and test, and learn to see around those illusions. The unceasing flow of tiny learning forces—pressed finger against pliant material, sensor cell in the skin exciting a neuron that signals the brain as the pressure reflects—this flow is the blood of perception.

Verb Not Noun

Virtual reality researchers prefer verbs to nouns when it comes to describing how people interact with reality. The boundary between a person and the rest of the universe is more like a game of strategy than like a movie.

The body and the brain are constantly probing and testing reality. Reality is what pushes back. From the brain’s point of view, reality is the expectation of what the next moment will be like, but that expectation must constantly be adjusted.

A sense of cognitive momentum, of moment-to-moment anticipation, becomes palpable in VR.

So how can we simulate an alternate reality for a person? VR is not about simulating reality, really, but about stimulating neural expectations.

Eighth VR Definition: Technology that rallies the brain to fill in the blanks and cover over the mistakes of a simulator, in order to make a simulated reality seem better than it ought to.