Lily Salter's Blog, page 201

December 23, 2017

Can humanity make peace with its death?

(Credit: Getty/solarseven)

Earlier this month, a 3-mile wide asteroid known as 3200 Phaethon passed by earth. It didn’t strike us (obviously), and if it had it’s not clear whether its impact would have completely obliterated humanity or merely been devastating. But scientists believe it could hit us in the future — and even if it doesn’t, there are plenty of other celestial bodies out there which are large enough to wipe out all life on this planet and which could very well strike us.

This raises an important question: If humanity were to go extinct, would we as a species be collectively ready for it?

I don’t mean would we be able to avoid it somehow. Are we able to make peace with our own death as a species, much as specific human beings often try to make peace with their own deaths as individuals?

There are many compelling reasons for us to ask this question right now. Global warming is reaching a crisis point, and while it’s impossible to predict how exactly that will end, humanity’s extinction is certainly within the realm of plausibility. The threat of nuclear war has loomed over our species since that fateful day in 1945 when Harry Truman dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and today could come about either through the actions of Islamist extremists or the dueling man-children Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un. Epidemics have become increasingly likely, as diseases evolve into antibiotic-resistant superbugs. There are even dropping sperm counts among men in the Western world which, if mirrored by men everywhere else on the planet, could wipe us out while leaving most other species intact.

We like to imagine that, even if these or other extinction-level scenarios were to transpire, somehow humanity would avoid its own demise at the last second, like in a blockbuster movie. Perhaps we could do so — but it’s entirely possible that we could not. And if there is one thing we don’t want to do, it’s spend our final moments as a species in denial of the inevitable.

Or don’t we?

“Well, I really hope people don’t find a way to make peace with human extinction,” Dr. Thomas Pyszczynski, a psychology professor at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs and co-founder of Terror Management Theory, told Salon. “I suspect if the disaster scenario came to pass, we’d see a lot of what we currently see among people faced with terrifying reality — denial. And there would likely be voices telling them it’s not really going to happen, a hoax by scientists, or whatever — and many would believe this more comforting version of reality, just as they do now.”

“You’d also likely see a massive resurgence of religious fervor and wishful thinking in terms of scientific solutions,” he added. “People would likely become more vigorous in their insistence that only they have the right answers. And ultimately, in the end, people would cling to their loved ones and families as the end approaches, just as they do now.”

His point was echoed by Dr. Jeff Greenberg, a psychology professor at the University of Arizona and another co-founder of Terror Management Theory.

“We live in denial of lots of stuff; we can’t enjoy life without blocking out our awareness of tragedy happening for some people in some places around the clock,” Greenberg told Salon. “We deny death as final via investment in literal and symbolic bases of immortality. Our own mortality is hard to escape; we’re reminded of it in so many ways day to day. The end of the species is more remote; it takes considerable cognitive effort to think about it and recognize.”

Greenberg also noted that if humanity was confronted with the fact of its impending extinction, it would “lead us to question our strings for symbolic continuance through ‘achievements,’ offspring etc.” This is another key point: One of the most significant ways that we try to cope with our own deaths as individuals is to imagine ways in which we can be “immortal” through our contributions to humanity. This is one of the reasons why so many of us have children, pursue careers or try to do good works that help other people. Yet what if there are no other people, or even other life forms at all? What if our careers are meaningless because there are no other sentient beings capable of appreciating those accomplishments? What if our children, like ourselves, will one day be wiped out completely?

Assuming we could move past the initial phases and forms of denial, the next step would be to figure out how we could make peace with the meaning of our own collective existence as a species. Does it all become pointless once everything ends?

“People have put much thought to what it means to live ‘the good life’ as a person, but there has been almost no thought put into what it means to live the good life as a species,” Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist working for the Carnegie Institution for Science, Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University, told Salon. “I guess one trivial answer is that we as a species are nothing but a collection of individuals, and the good life of a species is nothing more-nor-less than the individuals of that species living good lives. And I suppose that trivial answer would likely be my answer.”

Caldeira makes an excellent point here, one that perhaps offers the best defense against the logic of those who would respond to an extinction-level event by looting and rioting en masse. If we’re all going to die anyway, why not spend our final moments doing good by the ones we care about? Why not comfort and play with our children, express gratitude to our parents, joke with our friends, make love to our spouses and significant others? If we must be or choose to be solitary, why not spend our final moments at least engaging in those activities which make us most happy (a suggestion that, admittedly, would likely be toxic in the hands of the truly malevolent)?

There is a deeper level to Caldeira’s point about living the good life as a species. How we wind up dying off collectively matters a great deal in terms of how we can cope with the underlying meaning of the very fact that we existed at all. There is no shame in dying off because of some event that was entirely beyond our control, like an asteroid hitting earth, or even one that we caused for understandable reasons, like fighting diseases so effectively that they evolved into superbugs. On the other hand, it will be shameful if we die off because a faction of our population was unwilling to restrain polluters who caused unnecessary climate change. There are other ways in which pollution could kill us off (look at the declining bee populations, for one thing), and beyond that there is always the possibility that nuclear war could do us in. If the unrestrained ids of fanatics or fragile egos of powerful men wind up resulting in our annihilation, it would be hard to imagine how we could explain ourselves to any hypothetical god.

I won’t claim to have the definitive answers to these questions, aside from the fact that they absolutely must be asked right now. It strikes me that, when you study the universe, the structure of the largest objects often seem to mirror the structures of the smallest ones. My favorite example is how the solar system looks an awful lot like an atom, and in that same way I wonder if maybe the life of an individual human being — which progresses from infancy and childhood through adolescence, adulthood and death — mirrors that of what we will experience as a species.

If so, then this question is really, at its core, about what phase we are in now, and whether we are ready to meet its challenges.

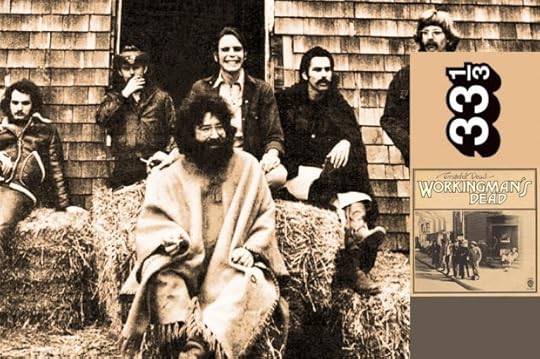

The Grateful Dead, with a side of LSD-laced venison stew

(Credit: Wikimedia/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon)

We need to go back to the beginning, when the Dead were still known as the Warlocks, an electric blues band unlike most electric blues bands. Their first gig happened on May 5, 1965, at a pizza parlor in Menlo Park, California, the next town over from Palo Alto on the peninsula south of San Francisco that separates the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean. That summer, they landed a residency more like a prison sentence, playing five 50-minute sets six nights a week at the In Room in Belmont, “a heavy-hitting divorcee’s pickup joint” (McNally, 2002). It was a formative period. The band would hang around together all day, some of them often high on LSD, arrive at the club, smoke pot, and play for a few hours. The songs became louder, longer, and weirder the later it got. It was how they began to learn to play together, and this led to people showing up not to get lucky at the In Room, but to hear a band making music fusing elements of Junior Walker, John Coltrane, and even the passing trains that regularly rattled the bar—“as the band grew more and more attuned to the schedule, they learned to play with, instead of against, the sound.” By November, their reputation had extended beyond the Peninsula, sharing similar musical and ideological freedoms with other Bay Area bands, like the Charlatans, the Great Society, Quicksilver Messenger, and Jefferson Airplane.

That November, the Warlocks learned of another band called the Warlocks. In fact, there were two bands using the same name at that time. The Velvet Underground were known as the Warlocks in their early days, and there was also a garage band out of Dallas, Texas, that used the same moniker (and happened to include Dusty Hill who would go on to be a member of ZZ Top). High on DMT at Phil Lesh’s house on High Street in Palo Alto, Jerry Garcia discovered the term “grateful dead” in a 1956 edition of Funk and Wagnall’s “New Practical Standard Dictionary.” These two seemingly incompatible words refer to a folktale about a corpse being refused a proper burial because of a debt owed. The tale’s hero unselfishly pays the debt, permitting the corpse’s spirit to be released from the dead body; later, the hero then encounters, and is rewarded by, the spirit he helped. As Dennis McNally writes: “The motif is found in almost every culture since the ancient Egyptians. Unknowingly, the Warlocks had plunked themselves into a universal cultural thread woven into the matrix of all human experience.”

Garcia and Lesh had been experimenting with LSD before the formation of the Warlocks, but between the advent of the Dead and the recording of “Workingman’s Dead” the band had earned their reputation as psychedelic trailblazers during the Acid Tests, the LSD- and lightshow-drenched gatherings devised by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” The Dead, like the Pranksters, were born out of the 50s bohemian scene in and around Palo Alto. Kesey had showed up from Oregon to attend Stanford University in 1958 and found himself living on Perry Lane, “Stanford’s bohemian quarter . . . It was a cluster of two-room cottages with weathery wood shingles in an oak forest, only not just amid trees and greenery, but amid vines, honeysuckle tendrils . . . Everybody sat around shaking their heads over America’s tailfin, housing-development civilization.” With his country boy genuineness Kesey made his presence known right away on Perry Lane. His reputation boomed, however, after he volunteered for drug experiments conducted by Stanford scientists at the Veterans Hospital in Menlo Park. All sorts of drugs were administered to him, but it was the LSD that changed everything—“suddenly he was in a realm of consciousness he had never dreamed of before and it was not a dream or delirium but part of his awareness.” Kesey wanted to share this profound awareness with anyone brave enough to try so he started bringing the experimental drugs home to Perry Lane. He’d make LSD-laced venison stew and local artists and musicians, including Garcia, would come on over to get hip to new realms of awareness.

The founding members of the Dead – Garcia and Bob Weir on guitars and vocals; Phil Lesh on bass and occasional vocals; Bill Kreutzmann behind the drums; Ron “Pigpen” McKernan striding back and forth between an organ and a front-and-center microphone into which he sang and played harmonica – had met through the overlapping scenes on the Peninsula. They’d been running into one another starting as far back as the early 60s. Near the end of 1963 a developer’s vision of modernity brought the high times on Perry Lane to an end. Kesey, having made a name for himself as a prominent novelist with “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Sometimes a Great Notion,” moved up into the hills of La Honda, where he bought a “log house, a mountain creek, a little wooden bridge . . . a redwood forest for a yard.” By 1964, Kesey and the Pranksters were throwing weekly Saturday night parties during which most everyone ate acid and then ran through the woods, played music, and made noise, sound recordings, and movies. When the Dead showed up for the first time the Acid Tests really came together. They went from house party to publicized events that took place around California, including on the campus of San Francisco State University and a Unitarian Church in Los Angeles, and beyond. The Dead also began to formulate their core creative ethos. The Acid Tests were about facilitating the freedom to experience the awareness acid had unlocked for Kesey. At any given Test, all present were equals; there was no distinction of us and them, performer and audience, straight-laced or radical—anyone and everyone could “Turn on, tune in, drop out” (a Timothy Leary expression that became famous after he declared it at the Human Be-In in San Francisco in 1967, at which the Dead played). As Garcia remembered the Acid Tests in a 1988 interview, “Everybody got high and stuff would happen . . . Everyone there was as much performer as audience” (Garcia, 2013).

The Dead weren’t at every Acid Test—and sometimes even when they were scheduled to play they didn’t because the drugs got the better of them—but it was the blurring of the line between performer and audience and the freedom it permitted to all that was the greatest takeaway for the band at this early stage in their career. During the Tests they reveled in music’s power to possess both performers and audience; everyone joyously surrendering to rhythms and harmonies, and arguably touching on something even more profound that reaches back to the origins of theater and art, connecting the temporal realm with the mystic. This is what the Dead sought to share with their fans through music. It wasn’t about getting high; it was about creating a space to be free from convention.

Check out the most-supported bag in Kickstarter history

In theory, your holiday luggage should make travel easier, right? That is unless your roller bag has a creaky wheel and your beaten up duffel is dangerously frayed at the edges. Consider an upgrade to the Bomber Barrel Duffel Bag, which helps you not only organize like a pro but look like a bonafide jet-setter.

Made out of premium, weather-resistant materials, this bomber bag, and travel kit feature carefully designed pockets designed to help you remain aware of where you keep your smaller essentials, from your toothbrush to your passport and anything in between. Not only does it help you stay organized, avoiding the annoyances of buying small expensive essentials you already packed (and just misplaced), it helps you carry your stuff with greater comfort and ease.

From an adjustable, padded quick release shoulder strap to wraparound, rivet-reinforced carry handles, you’ll get from point A to point B without looking like you’ve boarded the struggle bus. Added plus: it looks good too — just in case you wanted a dash of sartorial style at the airport.

Check out Kickstarter’s most funded bag ever: usually the Bomber Barrel Duffel Bag is $200, but you can get it now for $69.99, or 65% off the usual price.

December 22, 2017

Terror attack thwarted: Ex-marine charged with Christmas day plot

The J. Edgar Hoover Building, The Federal Bureau of Investigation headquarters, Wednesday, Aug. 19, 2015, in Washington. () (Credit: AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Federal officials have arrested a 26-year-old ex-marine for allegedly conspiring an ISIS-inspired Christmas Day terror attack. According to court documents filed on Friday, Everitt Aaron Jameson planned to attack San Francisco’s Pier 39.

Officials disclosed in the document that Jameson, who lives in Modesto, Calif., had been under investigation since September 2017 when he was first flagged for suspicious activity on Facebook. According to the report, Jameson was “liking” and “loving” Facebook posts that promoted terrorism and supported ISIS.

Once flagged, an FBI agent began direct messaging with Jameson on Facebook, where Jameson shared that he was wholeheartedly dedicated to “the cause.” The undercover agent responded by saying, “Patience.”

After the terror attack in New York on October 31, which killed 8 people, Jameson once again voiced his support for ISIS to the undercover FBI agent. A day after this conversation, Jameson reportedly filled out a “Franchise Tow Truck Driver Application” with the Modesto Police Department. Trucks have increasingly become a weapon for terrorists around the globe.

On December 16, in an in-person meeting with the undercover FBI agent, Jameson revealed that he wanted to carry out “something along the lines of New York or San Bernadino.” He suggested Pier 39, a popular tourist destination where visitors can see groups of sea lions, as a “target location.”

According to the complaint, Jameson described a plan in which explosives could “tunnel” or “funnel” people into an area where he could then “inflict casualties.” He also said Christmas Day would be a good day for the alleged attack, and that there was no reason for him to have an escape plan because he was “ready to die.”

Jameson allegedly suggested an assault rifle, like a M-16 and AK-47, as his weapon. According to the FBI, Jameson attended the U.S. Marine Corps’ basic recruit training in June 2009 and earned a “sharpshooter” rifle qualification. He was later discharged, according to the report, for not disclosing a “latent asthma history.”

Following the arrest, London Breed, San Francisco’s acting Mayor, said that there are no additional threats to San Francisco over the Christmas holiday.

“At this time, there are no known additional threats to San Francisco related to this investigation. While the FBI investigation into this case continues, the San Francisco Police Department will be increasing its presence throughout the City,” she said in a statement.

Puerto Ricans aren’t giving up on Christmas

(Credit: AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

Some say Puerto Rico has the longest Christmas in the world.

For Puerto Ricans, who are 85 percent Catholic, Christmas starts after Thanksgiving, continues through Christmas Day, and extends beyond Three Kings Day, on Jan. 6, with the “octavitas” – an eight-day street party that concludes in the St. Sebastian Festival in Old San Juan in mid-January. Christmas trees and decorations stay up for almost two months. The new year is greeted in noisy fashion, with street concerts and fireworks and guns fired celebratorily – albeit dangerously – into the air.

At least, that’s the tradition in my country. This year everything is different. In September, hurricanes Irma and Maria both battered Puerto Rico, killing perhaps as many as a thousand people and destroying much of the island.

Three months later, most Puerto Ricans still contend with some combination of unsafe water, no electricity, blocked highways, broken bridges, lack of internet and food shortages. Some 600 people are still living in shelters.

Can Christmas survive this catastrophe?

Survival first

I’m considering this question from my home in San Juan, the capital, where a Christmas miracle has occurred: Last week electricity was restored to parts of the neighborhood.

Currently, about 65 percent of the island has electrical power, and everyone else is constantly hunting for it.

But we’re also seeking another kind of power, I think – the strength to get through this national disaster.

Rural governments are still trying to tend to thousands of people left without water, electricity and medicine. Meanwhile, Gov. Ricardo Roselló is handling Puerto Rico’s hurricane aftermath while also reckoning with the island’s bankruptcy. Everyone has been working so hard for so long.

There are signs of desperation. Suicides and post-traumatic stress are a reality here now. It will be a long time before anything here starts to look normal again, and we know some things may never be the same.

At my job, as a special collections librarian at the University of Puerto Rico’s Humacao campus, our team is working from a tent outside while the library gets a deep clean. The building that houses the library leaked during Maria, so it soon became mold-infested. We lost our reference collection completely, along with all the furniture and computer equipment.

For a while there, I thought maybe Christmas might be one more thing lost to Maria.

The University of Puerto Rico in Humacao has reopened for classes since Hurricane Maria, though some buildings remain closed.

Milagros Rodriguez, Author provided

After the celebrations

Puerto Ricans, as it happens, are good at adversity. It’s a legacy of our colonial history.

Either way, the country’s resilience is on full display this Christmas season. Despite the blackouts that still affect even places where power’s been restored and the cold showers, we will have our holiday.

It may not be the longest Christmas in the world this year. And there may not be a lot of decorated trees, wreaths or parties. But in homes across the country people are roasting suckling pig right now, preparing blood sausages and stewing rice and peas.

We may have to cook over a charcoal fire, but to be sure: There will be bananas for our pasteles, meat-filled pastries served wrapped in a leaf.

Families hum along to holiday favorites – “Navidad,” a salsa tune by José Nogueras, and “Los reyes no llegaron,” a Christmas bolero by Victoria Sanabria – accompanied by the roar of generators.

José Nogueras’s ‘Navidad’ is a classic Puerto Rican holiday song.

Since my house has electricity, we’re stringing the Christmas lights and planning to party. Even in homes without power, that’s sometimes the case. As I heard one caller say on the radio, “We’ll turn on the Christmas lights even if it means plugging them into a generator.”

At work, the library team hung a Three Wise Men-themed decoration on our temporary library tent.

Christmas is on.

M. Rodriguez, Author provided

Elsewhere, sadness is more tangible. By November, 100,000 Puerto Ricans had fled Hurricane Maria’s aftermath, a number that grows daily. Many families will be missing their loved ones this Christmas.

Tragedy unites us all right now. In some places – like Santa Isabel, on Puerto Rico’s southern coast, and Moca, a town near Aguadilla – locals have decked out the main square, transforming storm debris into makeshift Christmas trees and wooden nativity scenes, all strung up with lights.

Such scenes reflect the national sentiment that not destruction, or terrible crisis management, or bankruptcy can take Christmas from Puerto Rico. Celebrating the holidays this year means feeling, if only for a moment, normal. It’s a sign of survival.

Evelyn Milagros Rodriguez, Research, Reference and Special Collections Librarian, University of Puerto Rico – Humacao

Watch for 7 U.S. science regulations/deregulations in 2018

(Credit: Spotmatik Ltd via Shutterstock)

Americans love to gripe about ridiculous-sounding regulations. We scoff at state rules that bar kids from running lemonade stands without proper permits and federal code that makes it a crime to sell earplugs when their noise-reduction rating isn’t written in a particular font (Helvetica Medium, for the record). There is even a popular twitter account, @CrimeADay, that churns out mentions of absurd-sounding regulations on a daily basis.

Certainly, not all laws are equally enforced, nor do they affect us all in the same ways. Yet once a rule is on the books it can have real consequences for individuals, businesses and communities—as can the delay or lack of clear requirements. Scientific American has looked into a suite of health-related federal regulations and guidance actions — including some that could affect tobacco use and food safety—that are likely to advance or stall out in 2018.

Say hello to nonaddictive cigarettes? Imagine buying a pack of smokes so light on nicotine that they are unlikely to create addiction. They would still have all the flavorings, chemicals and additives of old, yet they would have extremely low levels of the core ingredient that helps fuel smokers’ attachment to cigarettes at a chemical level. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration says such a change would help tamp down smoking rates that kill more than 480,000 people in the U.S. each year. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has said his agency is taking its first step toward that future. By the end of this year, he has said, it will release a formal request for public input on lowering nicotine in cigarettes. That document is currently with the Office of Management and Budget for review, and will then be published in the Federal Register.Lower nicotine levels could reduce new addictions and help currently hooked people quit, according to the FDA. Such a move was proposed decades ago but never took off — and will face significant opposition from tobacco companies. And if it does get the green light, officials will have to determine an acceptable nicotine level. “The best data we have suggests a nonaddictive level would be 0.5 milligrams in a cigarette, so that’s like a 95 percent or more reduction,” says Neal Benowitz, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Nicotine can be reduced via several techniques such as crossbreeding, genetic engineering or supercritical extraction—a process sometimes used to separate caffeine from coffee beans — says K. Michael Cummings, an expert in health behavior and tobacco research at the Medical University of South Carolina.

It’s time to judge chemical safety. Last year Congress revamped the decades-old Toxic Substances Control Act, which regulates thousands of chemicals. But in order to manage those substances the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency must now decide what levels it will consider harmful to human health and the environment. As a first step, in 2018 the EPA will start releasing risk assessments for 10 priority chemicals including asbestos and a dry-cleaning substance called trichloroethylene as well as a dye called Pigment Violet 29, which is used in paints, inks and pharmaceuticals. (All 10 risk assessments are due by 2019 and will be published in the Federal Register.)Deciding the official cutoffs for each chemical will be controversial. For example, a big question will be whether or not to count background levels of each substance that have accumulated in the past when there were no regulatory limits, says Rena Steinzor, a professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law and a member scholar the Center for Progressive Reform, a nonprofit organization that focuses on health and safety. Then there is the contentious fact that a top official responsible for these risk assessments is Nancy Beck, a scientist who, for many years, worked for the chemical industry at the American Chemistry Council. The Trump administration controversially granted her a special status exemption, sidestepping restrictions that would otherwise keep her from regulating or working with her former employer or clients for two years.

Stop your DIY gene editing. Last month the FDA issued a tersely worded warning to anyone thinking of trying gene editing at home: Don’t do it. This came after a software engineer injected himself with an experimental gene therapy for HIV while streaming it live on Facebook this past fall. Selling such unproved therapies is already against the law, the FDA notes. But the agency does not typically step in when individuals engage in such “biohacking.” All it has said so far about individual use is that “consumers are cautioned to make sure that any gene therapy they are considering has either been approved by the FDA or is being studied under appropriate regulatory oversight.” This may be an area to watch for further action in 2018, says Adam Thierer, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Guidance! Get your guidance here! In Pres. Donald Trump’s first address to Congress, he promised to seek sweeping cuts to restrictions on business. “We have undertaken a historic effort to massively reduce job-crushing regulations, creating a deregulation task force inside of every government agency; imposing a new rule, which mandates that for every one new regulation, two old regulations must be eliminated; and stopping a regulation that threatens the future and livelihoods of our great coal miners,” Trump told lawmakers.And regulatory affairs experts say it is likely the number of regulations coming out of federal agencies will be slow in 2018 — partly due to the administration’s decreased agency budgets and its belief that there should be far less federal rulemaking and also because technological advances often outpace policy. As a result, Thierer says there will likely be more “informal consultations” between agencies like the FDA and companies with questions. He adds we should also expect the release of more guidance documents that spell out what agencies are worried about and what they do not plan to regulate — effectively deregulating items or practices without formal rulemaking.In response to a list of detailed questions on this and other regulatory issues the FDA wrote to Scientific American in an e-mailed statement: “The FDA has put forth a robust policy agenda to advance our public health mission in 2018. Over the next year we will tackle many of our priority areas through both regulations and guidance documents, determined based on the best and most appropriate path.”

Food label makeover? Not so fast. A revamped nutrition label was slated to debut on food packages in July 2018 but in September the Trump administration announced companies could have another couple years to comply with this requirement. Big food companies will have until January 2020 and smaller ones until January 2021. The new labels were approved by the FDA in May 2016. They offered more detailed information about “added sugar” versus natural sugar and easier-to-read information on calorie counts, among other changes. Critics say the new extension represents a major blow to public health and the fight against obesity.

Action to stabilize the health insurance market. In the early years of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) the Department of Health and Human Services was kept busy issuing and implementing regulations to support the monumental health care law, notes Wendy Parmet, faculty director of the Center for Health Policy and Law at Northeastern University. Now the tax bill has a provision that removes the insurance mandate and once it becomes law, as expected, then lawmakers may have to follow up with some sort of actions to stabilize the market, potentially leading to new regulations from HHS.

Repealing a major Obama-era carbon emissions rule? In August 2015 the Clean Power Plan was announced by the White House. This EPA policy required power plants fueled by coal and natural gas to significantly slash their carbon dioxide emissions. But this past fall the Trump administration said it would repeal this regulation — a move experts said would make it difficult to cut power emissions or meet Paris climate accord requirements. The change was open to public comments through December 15 and elicited more than 150,000 submissions. The agency will review that feedback in the coming months. But it is also moving forward with its next steps: On Monday, the administration started asking for public comment on what a replacement rule for the plan should look like.

Bonus: State action to improve health and safety. States and cities may take up their own regulatory actions, too. Areas to watch include more possible soda and cigarette taxes, already imposed in a handful of jurisdictions. Cities may also seek to reduce pedestrian deaths via programs similar to New York City’s “NYC Safe” — an initiative that changed zoning and speed laws and required more barriers between pedestrians and cars, notes Lawrence Gostin, the director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. “We often think of public health as being about infectious disease and obesity,” he says, “but road traffic injuries and deaths are part of this, too, and they are very amenable to regulatory prevention.”

How to get away with bankruptcy fraud

(Credit: Getty/AlexStar)

The boxy building that houses JC Foreclosure Service doesn’t look like much. Drive past, and you might miss it among the gas stations and body shops and small homes here in Bell, a working class, Hispanic enclave in the south part of Los Angeles County. The only thing that might catch your attention is the bold red writing on the front window that says, in Spanish, “WE MODIFY YOUR LOAN. EVICTIONS. BANKRUPTCIES.”

The boxy building that houses JC Foreclosure Service doesn’t look like much. Drive past, and you might miss it among the gas stations and body shops and small homes here in Bell, a working class, Hispanic enclave in the south part of Los Angeles County. The only thing that might catch your attention is the bold red writing on the front window that says, in Spanish, “WE MODIFY YOUR LOAN. EVICTIONS. BANKRUPTCIES.”

But inside, a kind of magic happens. The owner of the business, Carlos Baez, is a master of a Los Angeles art: contorting bankruptcy into a tool for profit. When his clients come to him, desperate to stay in their homes, he can promise help — as long as they keep paying him — by harnessing the power of bankruptcy to stop foreclosure. Baez is not a lawyer and records show the hundreds of cases he’s filed are often shoddily prepared and thrown out within a few months. But actually winning lasting debt relief for his clients isn’t the point. The goal is to buy time — which he does again and again.

Of course, there are laws to prevent such abuse of the system. If someone files again and again, bankruptcy’s protections can be revoked. But Baez has another technique he often uses. On paper, his clients appear to transfer ownership in their homes to a group of people who get 5 percent apiece. It’s a trick that can turn one homeowner into four homeowners, each of whom can file for bankruptcy, one after the other. It doesn’t matter if these new homeowners are real. By the time a flesh-and-blood person must appear at a hearing, a month or two has passed. Then the case is dismissed and a new homeowner comes forward. Rinse and repeat.

With tricks like this, foreclosure can be kept at bay for months and sometimes years. It’s the kind of brazen fraud one would expect to be swiftly spotted and punished. But this is Los Angeles, where Baez is not a remarkable innovator, but merely one more practitioner in a decades-old local industry. He’s been at it for more than 10 years. It’s hard to keep track of all the bankruptcy laws he’s broken and based on his answers to my questions, he won’t be stopping anytime soon. He’s helping his clients, he says, and that’s what bankruptcy is for.

I came to Los Angeles because national filing data showed something remarkable was happening there. No other district in the country has anywhere close to the number of cases filed without an attorney as the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Central District of California, a warning sign because debtors generally fare much worse without legal representation. Digging deeper, our analysis found thousands of cases filed each year that bore the hallmarks of fraud.

Moreover, it turned out this is an open secret not only among the judges and court administrators in the district, but also among bankruptcy experts nationwide. Twice, Congress has even passed laws to combat the bankruptcy-related schemes emanating from Los Angeles.

This is what underscores the frustration of Judge Maureen Tighe, who presides in the district and has tried to raise the alarm about the level of fraud. A former prosecutor, she directs court employees to look for suspicious people, tries to sanction those breaking the law, and helps publish reports on the scale of potential fraud. She’s even called special hearings. But that is where her powers stop. And the arms of the justice system charged with policing these crimes — the U.S. Attorney and the Federal Bureau of Investigation — rarely do.

“If nobody follows the law, and there’s no enforcement mechanisms or enforcement resources, what good is the law?” Tighe asked.

The success of these schemes reflects a basic fact about the bankruptcy system. For people with the sophistication and resources to hire reputable attorneys, bankruptcy works well. For others, there are traps.

ProPublica has been examining deeply ingrained problems in the nation’s bankruptcy system using a first-of-its-kind analysis of filings. Across the country, we’ve found how the costs of filing have, in various ways, caused harm to those bankruptcy was designed to serve. Earlier this year, we reported on how black Americans in the South are far less likely to attain lasting debt relief from bankruptcy because steep, up-front attorney fees force them to choose bankruptcy payment plans they are likely to fail.

In Los Angeles, we found, vulnerable people with debt, particularly minorities and immigrants, are more likely to try navigating the system with no attorney at all. Many turn to unlicensed bankruptcy petition preparers like Baez, who often operate beyond what the law allows and hide their involvement in filings.

Court districts in other parts of the country with high numbers of pro se filings — places like Atlanta, Detroit and Milwaukee — have similar fraud problems, particularly involving unscrupulous petition preparers who flout the rules and overcharge for their services.

“There are all these people that need the relief of the bankruptcy system, who can’t afford it,” said Tighe. “And they fall prey to these fraudsters. If we had adequate access to our legal system, they would not be this wonderful ripe field for picking by the fraud artists.”

Despite these destructive patterns, both in the South and in Los Angeles, we found an entrenched lack of will to stop them.

Without much criminal enforcement of the laws, the amount of fraud in the Central District of California rises and falls with the economy. During the foreclosure crisis in 2011, when the district’s 126,000 consumer bankruptcy filings accounted for nearly a tenth of all such filings in the country, it exploded. But, in an area where so many struggle to afford their homes, plenty of fraudsters are still in business.

The U.S. Trustee Program, which oversees the bankruptcy court, refers hundreds of potential crimes to the local U.S. Attorney office every year. In most years, only one to three cases result in prosecution, according to data obtained by ProPublica through a Freedom of Information Act request. In 2009, not a single one of the 266 criminal referrals made by the U.S. Trustee office in the district resulted in prosecution.

“There’s a lot of frustration, I think, among some members of the U.S. Trustee Program who feel like they’re doing their darndest trying to do something about this type of financial crime,” said Jennifer Braun, who worked as an attorney with the program’s district office until earlier this year.

Federal prosecutors cite a lack of resources and a need to pursue higher profile crimes as the reason for the dearth of bankruptcy cases. Untangling the complicated schemes is a lot of work for a low-wattage win, they said.

As a result, especially in the largely Hispanic and immigrant neighborhoods in and around Los Angeles, it’s not hard to find examples of these schemes. All I had to do was look.

I found Liderazgo Financiero just a couple miles away from JC Foreclosure. “NO PIERDA SU CASA” — Don’t Lose Your Home — said the printed sign hanging over a barred window outside. Inside, stacks of lime-green mailers covered in urgent warnings about foreclosure in Spanish sat on a desk, ready to be sent out.

“The only way to stop a foreclosure is a bankruptcy,” Santiago Nuñez told me when I visited his small office in South Gate last June. “You have to do a Chapter 13.”

Chapter 13 really is the best option under the bankruptcy code for someone facing foreclosure. Theoretically, struggling homeowners can catch up on their mortgages through a payment plan, typically lasting five years, calibrated to their income.

But even when debtors file with an attorney, Chapter 13 has its risks. Without an attorney, it’s almost hopeless.

Between 2008 and 2014, almost half of the Chapter 13 bankruptcies filed in the Central District of California were done without an attorney. About 85 percent of these pro se filings were left incomplete, lacking the debtors’ basic financial information, according to ProPublica’s analysis. Nearly all were dismissed within a few months, meaning the debtors were back at square one with no debt relief.

When I reviewed 50 pro se Chapter 13 filings in mostly Hispanic areas where bankruptcies without attorney representation are most common, I found that two-thirds of the debtors ultimately lost their homes, usually within a year of filing.

Neither Nuñez, nor his wife, Veronica, who owns the company, is an attorney.

Switching between English and Spanish, Nuñez affably described the services Liderazgo offers clients desperate to save their homes. Local bankruptcy attorneys, he said, can bill up to $5,000 to file under Chapter 13, but his company charges clients just $200. Attorney fees for Chapter 13 in Los Angeles do indeed range from $4,000 to $5,000, but many attorneys accept a portion of that up front, with the remainder paid through the plan. Much to the frustration of judges and attorneys in the district, companies like Liderazgo often lure in clients with promises of a cheap rescue, but then end up extracting fees similar to what attorneys charge.

When I asked Nuñez about his fees, he conceded that the $200 covered only the most basic document — the petition. To file all the necessary information about the debtor’s incomes, assets and debts, the company charged $1,500, he said.

That’s against the law. Non-attorneys are permitted to assist someone with a bankruptcy, but if they accept payment, their activities are strictly limited. They must disclose their involvement and can’t give legal advice. In Los Angeles, anyone can open up shop as a petition preparer, but the maximum they can accept for filling out the forms is $200.

One preparer I spoke with said the job is all but impossible to do well and also be in compliance with the law. “You can’t be a preparer and not give legal advice, because if a client has any question [about the bankruptcy], and you answer the question, you’re giving them legal advice,” said Christian Yates, a paralegal. After being fined by Tighe in 2012 for violating filing laws, Yates said he now only assists with bankruptcies with a lawyer present, which is allowed. But other preparers are “going to continue to do it until they get caught,” he said.

The preparers are most active in the district’s Hispanic neighborhoods, but they are everywhere, promising help with both Chapter 13 and Chapter 7, which typically wipes away debts within a couple months. One debtor I met at a court hearing, who asked that his name not be used, told me that he’d found a preparer by simply Googling “Los Angeles Paralegal” and had paid $750. Petition preparers are forbidden from using “legal” or similar words in advertising their services, but many just ignore that.

According to court records, Araneta Legal Services, which until recently operated the website losangelesparalegal.org, didn’t disclose that it had filled out the debtor’s petition. Preparers can evade the attention of the court by simply not disclosing their involvement in a case, another violation of law. Joseph Araneta, the company’s owner, did not respond to my calls and emails. The company appears to have shut down.

As for Liderazgo, records show that it has been involved in more than 200 bankruptcies since the middle of 2012. In at least 56 of them, the company didn’t disclose its involvement.

I was able to tie these cases to the company because Veronica Nuñez is identified in court data as having brought them to the courthouse. As a way to combat preparers dodging the disclosure requirements, all five court locations in the district began requiring non-attorneys in 2012 to present their ID when filing bankruptcies for clients in person. The court shared this data with ProPublica. But even this tally is likely incomplete, since Santiago Nuñez told me that the company generally requires its clients to file the cases themselves. Doing so is another way for preparers to avoid scrutiny.

Some of the Liderazgo bankruptcies I looked at were clearly phony. In one scheme that ran from 2009 and 2015, 18 different debtors listed the same Compton address as their home on their bankruptcy filings, but only one of them actually lived in the 1,100-square-foot house, according to public records.

Veronica Nuñez brought eight of these Compton bankruptcies to the courthouse, the court data shows. A ninth bankruptcy was filed under the name of Juan Azuaje, a man who had hired Liderazgo to help avoid foreclosure on his home 50 miles away in Simi Valley, according to a recording of a court hearing in 2012. Court records show he, or someone using his name, filed two separate bankruptcies on the same day — one listing the Simi Valley address as his home, the other the Compton address. Public records show Azuaje had no connection to the Compton home, which was ultimately foreclosed on. Azuaje and the former owner of the Compton property could not be reached for comment.

Liderazgo’s frequent filings haven’t gone unnoticed by the court entirely. In January 2012, a judge in the district issued an order for Santiago Nuñez to appear and face possible fines for improperly filing a case. He didn’t show.

That’s typical, Tighe said. “I have hundreds of orders that are being ignored.”

Nuñez did not respond to a detailed list of questions that outlined several violations of the law.

In the summer of 2012, Mohsen Saeedy was desperate. An Iranian immigrant in his 50’s, he’d built up his own photo printing business in Los Angeles and poured his savings into a ranch-style house in Phoenix, Arizona, where he and his wife planned to retire. The interest-only, adjustable-rate mortgage had seemed affordable in 2007. It wasn’t anymore.

Then he found JC Foreclosure. As Saeedy remembers it, the company promised to force the bank to modify his loan and knock the principal down to what the house was actually worth. Amid his desperation, Saeedy said, the promises were irresistible. He paid $1,000 to a middleman for connecting him with JC Foreclosure. Then he gave the company $1,600 to get started, and agreed to pay $600 every month in cash.

Of course, JC Foreclosure had no special power to bend banks to the company’s will. But it had plenty of tricks.

Shortly thereafter, the company executed a deed transfer from Saeedy’s wife, who was the title-holder of the Arizona home, to a woman named Marian Garcia. Later, a second and then a third deed transferred interests in the home to four other individuals. Saeedy told me he’d never heard of Garcia or any of the other people, and his wife said she never signed any such deeds.

In these types of arrangements, Chapter 13’s power to protect can be deployed over and over for the same home as long as each debtor appears to have a claim to bankruptcy’s protections.

It’s “the cheapest temporary restraining order anybody can get,” Tighe said.

It’s unclear if any of these people knew they’d gained an interest in an Arizona home. A couple of them don’t appear to be real.

But one unwitting new owner of a piece of Saeedy’s property is definitely a real person. In fact, he’d already filed his own, unrelated bankruptcy case — after initially filing on his own, he then retained an attorney. Unbeknownst to him, scam artists had transferred portions of at least 11 properties, Saeedy’s home among them, to him, according to motions filed in his case.

Attorneys, judges and prosecutors call this fraud technique “hijacking.” Fraudsters simply pick a recently filed bankruptcy — it doesn’t matter which one, really — and then pretend the debtor in that case owns the properties the fraudsters want to protect. It’s a neat ploy that stops foreclosure and saves the expense of the filing fee.

“Hijackings” like these create headaches for attorneys and judges and put legitimate debtors in danger of being adversely affected. Renay Rodriguez, an attorney in Los Angeles, handled one case in which portions of 13 different properties were transferred to her clients. “It was absolutely bewildering to try and explain to them,” she said.

The other four people who received an interest in Saeedy’s home all filed for bankruptcy pro se. One appears to be a real person who, with the help of a different petition preparer, filed for bankruptcy nine times over six years and finally was barred by a judge from ever filing again. Another claimed to live at JC Foreclosure’s business address.

When I visited this summer, the company’s small office was empty except for a woman at the front desk.

She told me the company didn’t file bankruptcies because Baez, the owner, wasn’t a lawyer. Instead, she said, the company referred clients to a law firm when bankruptcy seemed appropriate. She couldn’t remember the name of the firm.

On the counter in front of her desk — next to a stack of mailers, marked “URGENTE,” addressed and ready to send to potential clients — were bankruptcy forms, filled out for a debtor by the name of Suyay Crow, but yet to be filed.

Later, when I checked public records, it appeared that no one by that name has ever lived at the South Los Angeles home that was listed in the bankruptcy filing. It was actually the second time Crow had filed for bankruptcy at that address, each time without an attorney. Crow, who may or may not exist, had gained an interest in the property through a deed executed last March.

The next day, I visited that South Los Angeles home. Four cars were parked outside, and children played in the yard. Junk, including an old fish tank and tires, lined the front porch. The owner of the home, an 86-year-old black woman, answered the door in a wheelchair. She said she lived there with her niece, son and his two daughters and had owned the home for over 20 years.

The woman, who asked that her name not be used, told me she’d never heard of Crow, Baez or JC Foreclosure. She was facing foreclosure, she said, because a loan had jumped in payments. Using another nearby petition preparer, she’d twice filed for bankruptcy under her own name in recent years. Both times the cases were quickly dismissed. But she said that she knew nothing about other filings and had never signed any deed transferring an interest in the property.

“I didn’t have nothing to do with it, nothing at all,” she told me.

Public records show that the lender foreclosed on the home in October.

Since 2012, Baez has brought at least 237 bankruptcy cases to the courthouse. In only 10 cases was a preparer disclosed. As with Liderazgo, the count likely captures only a portion of the company’s activity, especially since JC Foreclosure has been operating since 2005, long before the court began tracking suspicious filers more closely.

The company appears to routinely charge its clients fees well in excess of the allowed $200 for its services, as it did Saeedy. One contract shared with me from last year shows the company charged $1,200 to file a Chapter 13 bankruptcy.

Cycles of fake bankruptcies can prevent foreclosure for years, but sometimes mortgage servicers eventually figure out the scheme and file a motion to stop it. In response to a string of seven filings that appear to have been arranged by Baez (court data shows he personally brought at least two of the cases to the courthouse), an attorney for a mortgage servicer declared in a 2013 motion, “The abuse of bankruptcy laws must be put to an end. Enough is enough.”

The mortgage servicer eventually caught on in Saeedy’s case, too, and obtained an order preventing any future bankruptcy from stopping foreclosure on the property. For more than a year, Saeedy paid Baez’s company with the expectation of a loan modification, he said. Then Baez abruptly informed him the company could do nothing more to help him. Foreclosure was again imminent. In a fresh panic, Saeedy filed for bankruptcy on his own to stop the sale and then quickly retained an attorney.

Only then, he said, did he learn about the fraudulent bankruptcies. His lawyer explained that because of them, his own bankruptcy had not halted foreclosure.

Almost four years later, Saeedy is still picking up the pieces. He ultimately decided to drop his bankruptcy case because he didn’t see the point. He regrets not having filed earlier. “I would have a much different outcome,” he said.

Typical of those who are swindled, Saeedy didn’t file a complaint or go to the authorities. Instead, he said, he has been “in denial” about the thousands of dollars he wasted. “I didn’t want to think about how stupid I was.”

I sent questions to Baez, laying out the evidence that his company had violated bankruptcy laws hundreds of times. I also detailed four other deed transfer schemes in addition to the ones discussed in this story.

In a written response, Baez didn’t deny or admit forging documents or filing bankruptcies in the names of fake people. He declined to discuss any particular case, saying that doing so would require a signed release from the client.

Instead, he argued that since his company filed bankruptcies to benefit clients, the filings had not been fraudulent, since the bankruptcy laws “are there to protect debtors.” He also said I was wrong to say he worked as a petition preparer because most of his clients “do not come to us just to file a bankruptcy.” He charges clients more than $200, he said, because the company spends a lot of time working with clients. “It is common practice among many service providers to assist their clients in filing a Chapter 13 if more time is needed in negotiating with the lenders,” he added.

There is no exception in the law that allows businesses to charge more than $200 if they provide other services in addition to preparing bankruptcies.

Baez said that his office routinely provides clients “the service” of bringing their bankruptcy filings to court and paying the filing fees. That is a violation of the law.

But he said that my questions had spurred “a careful review of our business practices.” Going forward, JC Foreclosure will require that clients file their own bankruptcies, he said.

In a sign of the challenges the court faces, this promised change will simply make it harder for the court to track the company’s activities.

Prosecutions of bankruptcy fraud weren’t always as rare as they are now. In 1988, when Tighe began her career as a prosecutor in Los Angeles, her sole responsibility was combatting such fraud. Even then, the area demanded attention due to the extremely high number of filings by debtors without attorneys and the proliferation of petition preparers.

“I put a lot of them in jail,” Tighe said of the early innovators of fraud in the district. Into the 1990s, bankruptcy prosecutions remained a priority. In 1996, then Attorney General Janet Reno launched a national effort focused on the problem called “Operation Total Disclosure.”

But national statistics show these prosecutions began to dwindle after 2001. By 2011, the number of federal prosecutions in which a bankruptcy crime was the lead charge had dropped by more than half, according to data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

This drop came despite some internal alarms. At the FBI, a 2010 intelligence assessment, since made public, concluded that fraudulent bankruptcies, particularly those used to thwart foreclosures, would have a “significant impact on the US mortgage, banking, and securities industries; consumers; and the overall US economy.”

The schemes affect banks, investors and neighborhoods by drawing out inevitable foreclosures. They also cause unnecessary foreclosures by ensnaring struggling homeowners who might have succeeded in keeping their homes by legitimate means.

Despite the assessment, there is no evidence that resources were re-allocated.

In interviews, former federal prosecutors said budget cuts have gutted their ability to pursue such cases.

Evan Davis, a former federal prosecutor in Los Angeles, recalled his frustration when it was his job to coordinate federal bankruptcy prosecutions in the district during the foreclosure crisis, and the local U.S. Trustee office was sending him a steady stream of possible crimes to investigate.

“My inbox would get clogged with referrals that I had no interest in reading, because I knew they would go nowhere,” he said. “We would sit there lamenting that we can’t do more of these cases.”

Robert Dugdale, an assistant U.S. Attorney who was chief of the criminal division in Los Angeles from 2010 to 2015, said there was “a hiring freeze in our office for a number of years, so that everybody who left couldn’t be replaced.” At one point, he said, money was so tight that just sending a package by FedEx required a memo justifying the expense.

Constraints were even worse at the FBI, they said. After the 9/11 attacks, domestic terrorism became a major focus for the FBI and other law enforcement, drawing resources away from white-collar prosecutions. On top of that, FBI agents were “effectively dissuaded from pursuing [bankruptcy] cases,” Davis said, because bankruptcy fraud is classified in the lowest band of white-collar crimes.

The U.S. Trustee Program has also been squeezed by budget cuts. In recent testimony to Congress, the director of the program boasted about its “diligent management of increasingly scarce resources,” as its staff has been reduced by 14 percent over the last 10 years.

U.S. Trustee attorneys can bring civil cases in response to violations, but not criminal charges. For that, they refer cases to other agencies. State and local prosecutors can sometimes bring charges, but only if local laws have also been violated as part of the scheme.

In a statement to ProPublica, the Justice Department emphasized activities by the U.S. Trustee Program to identify bankruptcy crimes and train others to recognize it: “Over time, these collective efforts within the Justice Department and with the wider bankruptcy community may result not only in an increase in referrals and prosecutions, but also in greater deterrence of bankruptcy crimes at the outset.” The statement didn’t explain how this increase in prosecutions “may” occur.

The lack of resources available for bankruptcy-related prosecutions isn’t limited to Los Angeles. In Milwaukee, bankruptcy judges have long been concerned by the conduct of petition preparers.

“It’s somewhat tragic because the people who are being victimized by this are the most defenseless people out there,” said Judge Susan Kelley, the chief bankruptcy judge in the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

Every April, after the harshest months of the Midwestern winter have passed, Milwaukee’s energy utility ends its winter moratorium on shutting off gas or electrical service due to nonpayment. Threatened with losing service, many residents respond by filing for bankruptcy — often with the help of preparers, Kelley said.

The vast majority of these debtors are low-income and black. According to ProPublica’s analysis of filings in the district from 2013 through 2015, almost half of the Chapter 7 cases filed by debtors from majority black areas were done without an attorney. In the mostly white areas, only 5 percent of filings were pro se.

Stopping these preparers has sometimes proven beyond the powers of the court. In one example, judges twice sent U.S. Marshals to force a preparer to appear before them and explain why she had ignored court orders and fines. When even that didn’t stop her, the court sought criminal sanctions.

The local U.S. attorney’s office, however, declined to prosecute, because doing so “would not be a wise use of law-enforcement resources,” according to a district court order.

“I just find it very frustrating that we can’t do something more,” said Kelley, who said she can’t recall hearing about a single prosecution of a preparer in the district. “These people are preying on the poorest of the poor.”

A spokesman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Wisconsin declined to comment.

Thom Mrozek, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles, acknowledged that staffing has been particularly diminished “at several points over the past 10 years,” but said that it’s on the upswing. “We allocate our limited resources after taking into account the facts of an individual case, as well as our desire to address the most serious crimes and maximize deterrence in areas of most concern.”

The office has brought a few significant prosecutions for bankruptcy fraud in recent years. But sometimes even those cases have a way of highlighting how limited the enforcement of bankruptcy laws has been.

Last June, the U.S. filed charges against Mickey Henschel, who is something of a Los Angeles institution. In 1995, he was the subject of a profile in The Los Angeles Times. The author marveled that, despite several allegedly fraudulent activities (including arranging bankruptcies by fictitious people), Henschel had managed to stay out of jail. Nine years later, the Times again reported on Henschel, noting, “One of the safest places to engage in fraud is Southern California,” and again marveled at his ability to avoid prison, despite several scrapes with the law and a long history of alleged bankruptcy fraud.

Now in his late 60s, Henschel has finally for an alleged scheme to string along desperate homeowners by filing phony bankruptcies, among other tactics. His company has collected more than $7 million from victims, according to prosecutors. Henschel pleaded not guilty. His attorney did not respond to my questions.

To prosecutors who have worked in the district, the existence of longtime operators like Henschel offers some explanation for why bankruptcy fraud is so common here. The fraudsters teach their craft to others, who teach still others. By now, the skillset is hopelessly widespread. And the demand, when the economy sours, can be limitless.

“We’ve got this major consumer fraud problem here, and we don’t have any deterrent,” said Tighe. “It’s a shame, because it gives bankruptcy a bad name for the people who really need it and who are using it legitimately.”

Please stop breaking up with my girlfriend

(Credit: Getty/123ducu)

Looking up from my drink and across the room, I watched my girlfriend and my roommate kiss for the first time.

It was her 21st birthday, five days into the spring of our junior year. Heads swiveled toward Elizabeth and Jamie as their kiss deepened. Quiet rippled out through the din of the party. In the background, Beyoncé continued to serenade us with “Drunk in Love.”

Jealousy welled up in me: I was the one who wanted an open relationship, not Elizabeth.

Crushes have always sprouted in me, independent of my will, like I live in an endless springtime. One blossoms for someone who feels right in my arms at a blues dance, another bursts for a classmate who writes achingly beautiful poetry — all the time, people pop up and make me dizzy.

But every time a crush budded, I felt like I’d betrayed Elizabeth. When I snipped it before it could fully bloom, I felt like I’d betrayed myself. I didn’t want to leave her, but I craved freedom to explore.

Several months before, I’d confessed this desire to her. “I want to give that to you,” she whispered — but the idea made her seethe with anxiety. Our time together was already a constant negotiation. She had to micromanage her schedule to balance a Mathematics major with ADHD, while my distaste for clocks and Google Calendar verged on phobia. We lived in glimpses and embraces between class; love slipped into the little spaces we had left over. She feared we’d have no time left at all if we were entangled with other people.

So as her mouth moved against Jamie’s in one of the loveliest kisses I’d ever seen, I felt a lot of things. Jealousy, yes, at the bitter irony that she had what I wanted. Confusion: Had she changed her mind, or was this just a drunken birthday kiss? Happiness, too — what some polyamorous people call “compersion” — that two people I loved were sharing this intimacy. And also a little private hope: that Elizabeth would understand me better now. Under my breath, I whispered, “Finally.”

As the night progressed, time warped around Jamie and Elizabeth’s kiss. It never stopped. I got drunker than I’d ever been. For the first time, I spent my night retching into a toilet. Elizabeth, after holding my hair, spent her first night in Jamie’s bed.

There was no privacy in our room; closeness was the way of our student-housing cooperative. The stairwells resounded with mandolin music. The walls of the gender-neutral shower room were sheened with orange grime. Nobody locked their doors, ever.

The third time I walked in on Jamie and Elizabeth kissing, we decided it was time to talk about it.

We spoke for hours. Softly, carefully. Elizabeth held my gaze. Jamie averted it. “We need each other,” Elizabeth confessed.

“Okay,” I said.

They glanced at each other. “Okay? Really?”

“I never want to keep you from what you need,” I said. “Need is sacred.”

“Thank you,” Jamie told me, over and over. And, “I don’t deserve this.”

Maybe they didn’t. Jamie hadn’t yet told Sophie, their long-distance high school sweetheart and maybe-someday-fiancée, about kissing Elizabeth. “She’ll definitely be okay with it,” Jamie assured us.

I had my doubts that Sophie — who rarely used gender-neutral pronouns for Jamie and wanted them to be her husband, not her androgynous partner — would be a fan of polyamory.

But Elizabeth was beaming at me, moon-eyed. “I feel a hundred times lighter right now,” she said, “than I can remember having felt in I-don’t-know-how-many-months.”

We weren’t sure how we’d make it work, but we knew we’d figure it out. We had to. At dusk we walked to a campus café through swirling snow, arm-in-arm and arm-in-arm, giddy with laughter, embarking on this strange journey together.

The walk sticks out in my memory, because I think it was the last time all three of us were happy at once.

Later that night, Jamie called Sophie. Sure enough, they returned to the room and murmured, almost inaudibly, “This can’t happen anymore.”

But it kept happening.

Maybe I should’ve told Jamie and Elizabeth to stop. But watching them fall in love felt like falling in love myself. I liked when Jamie, half-asleep, would murmur, “I’m crazy about her,” and I would reply, “Right?!” I liked how Elizabeth told me little secrets and snippets of dialogue — and I liked the mystery of what she’d keep to herself. I liked waking up curled against her some mornings, and on others watching her stretch from Jamie’s bed, and waving to her.

But I hated how, wracked with guilt after Skyping with Sophie, Jamie would wrench themself away from Elizabeth.

It was a vicious cycle. Jamie couldn’t kiss Elizabeth without confessing the infidelity to Sophie, who insisted that this couldn’t continue. Jamie couldn’t help but agree and tell Elizabeth they had to break it off. Which left me stroking Elizabeth’s hair through the night as she wept and pined for all of the things they couldn’t do. Next week, they would find themselves alone together, and the cycle would begin again.

Jamie’s cheating sucked. I was complicit in it. But I felt Jamie deserved to be with someone who fully embraced their gender. Someone like Elizabeth.

So I began to root for my roommate to break up with the woman they planned to marry so they could stop breaking up with my girlfriend. For all our sakes.

Selfishly, what I liked most about our situation was clear proof that Elizabeth and I needed an open relationship. I liked trusting each other that much. I’d lost the guilt I felt when I held someone else’s eye contact in the library, or their hand on a walk, or their name in my mouth at night.

Until, that is, Elizabeth voiced her continued doubts about “outsiders” interfering in our relationship. People we both already knew and loved, like Jamie, were one thing. But interweaving the fickle needs of strangers into our life patterns? Weren’t we having enough trouble untangling the mess we were in already?

The double standard dug at me, made everything harder. Made it harder to hear about how wonderful Jamie was, how cruel Jamie was. Made it harder even when it was just me and her — because it was just me and her.

By mid-March, we were all looking for distractions. Elizabeth chose math. Jamie chose drugs. I decided to scrub every inch of mold from the co-op shower walls. Without a mask. The ensuing asthma attack landed me briefly in the hospital. After I was discharged, every time I stepped into our co-op, I felt my lungs seize up. I exiled myself for a week, sleeping alone in Elizabeth’s room across campus, while she and Jamie continued living in “our” room.

I lay alone in my girlfriend’s bed.

Without me there as a buffer, the tides of their relationship rose higher and broke harder. In panicked midnight walks and phone calls, Elizabeth insisted, “I can’t do this, Nick. I can’t. I’m not a polyamorous person.”

“But you’re in love with two people,” I protested.

“Exactly. That’s the problem.”

To Elizabeth, polyamory was an experimental structure for our relationship — one that wasn’t working. To me, polyamory was, is, a matter of identity. To me, loving two people at once is… loving two people at once. Three is three, twelve is twelve, one is one. Nothing about love should exclude, or possess, or covet. To me, it’s Time that is the great divider, limiter, and dissector of what could otherwise be infinitely expansive love.

And I will never stop wishing for more time.

I finally grew truly jealous of Jamie, as Elizabeth’s time and energy was consumed with their presence or siphoned by their absence. Grew resentful of their perpetual indecision, of how they kept hurting both Elizabeth and Sophie, of how the state of my relationship with Elizabeth depended entirely on theirs. Jamie had, at their core, a great restless emptiness that I couldn’t comprehend. They tried to fill it with drugs, with lovers, with an endless string of hobbies and talents that they inevitably soured on. Nothing sated. In the past I’d been concerned about Jamie’s patterns, but it was their life. Now everything they did with their time impacted how I spent my own.

Everyone just wanted everyone to be happy, but nobody was allowed to be.

Toward the end of April, Jamie left Elizabeth for good. Finally swallowed by guilt, they told Elizabeth, “I don’t love you anymore. You’ve hurt me too much.”

Elizabeth sobbed in my arms with wind whipping her hair as she repeated, “I am fucking up their life. I am fucking up their life.”

“Elizabeth,” I murmured. “I don’t think you’re doing anything to them that they’re not already doing to themself.”

At the end of the semester, I helped Jamie move out. That morning I was wearing a thin, floral-patterned shirt that had mysteriously appeared on my pillow. I tossed the last suitcase into the trunk of Jamie’s car, and we hugged farewell. I turned to head back upstairs.

“Thank you, Nick,” Jamie said quietly, their eyes briefly meeting mine. “For everything.”

I smiled back at them. “No problem,” I lied.

Later, Elizabeth called. She wanted to kiss me goodbye before she, too, drove away for the summer. I excused myself from my meeting and walked quickly from the library. I was startled as air rushed past me — I was running. Asthma and all, I was sprinting. As I flew down an alley toward the street, I heard a car door slam and a loud, fast pair of feet approaching.

Elizabeth careened around the corner and into my arms. The air was thick with birdsong. We kissed, still breathing hard from running to each other. Then her hands tugged at my new shirt.

“Why are you wearing Jamie’s shirt?” she giggled.

“I found it on my pillow,” I said, cocking my head. “I wonder why Jamie didn’t say anything about it.”

Elizabeth closed her eyes. “I left it there by accident. I was wearing it last night.”

And we laughed the way we had at the beginning of the semester, walking through snowfall, when everything was untarnished. Nothing was healed, nothing was saved, nothing made sense — but we were laughing again.

“The Greatest Showman” is a giant step backward

Zac Efron and Zendaya in "The Greatest Showman" (Credit: 20th Century Fox)

Hasn’t our popular culture evolved beyond biopics like “The Greatest Showman”?

The lavish movie-musical about the 19th century showman and circus entrepreneur P. T. Barnum certainly could have told an interesting story. Barnum was a fascinating and complex individual, a man who championed abolitionism and served as a reasonably competent politician in his later years but made his fortune through schemes that mislead paying audiences about what he was displaying and exploited the physical difference of so-called “freaks.” He was a philanthropist who always insisted on making a buck off of his charitable works if possible, a huckster who was beloved by those who knew him well, a charlatan entertainer who tried to debunk spiritualists and others whose deceptions he considered morally worse than his own.

I am not of the school that argues that biopics about historical figures need to vilify them, or even that they need to be terribly accurate. We can have fare like the musical “Hamilton” which, though glossing over Alexander Hamilton’s economic elitism and other unsavory political views, still manages to capture the nuances of his character in an intelligent and convincing way. It doesn’t even bother me that much of “The Greatest Showman” is grossly inaccurate in many ways (for example, Barnum was much older than Hugh Jackman is portrayed when he created the modern circus). These are understandable compromises, necessary for the sake of displaying a work of art — a fact that, appropriately enough, Barnum himself would have understood.

At the same time, there is something disheartening about the way that “The Greatest Showman” insists on transforming a three-dimensional human being into a generic musical protagonist. This isn’t the story of Barnum’s life, but a formulaic rags-to-riches story grafted onto the broad outlines of Barnum’s career as a circus entrepreneur. It’s remarkably unambitious as a result, turning its real-life characters into cardboard cutouts — Barnum is the con man with a heart of gold, his wife Charity is the long-suffering but loyal partner, New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett is a snooty and joyless art critic, etc. — and ignoring the thorny ethical questions that made Barnum’s story so intriguing.

Take its depiction of the “freaks” such as the morbidly obese man, the bearded lady, General Tom Thumb, the giant, the dog boy and so on. Considering that these marginalized individuals were vital to Barnum’s cultural legacy — without them, he never would have had his legendary circus — it is impossible to honestly tell Barnum’s story without exploring the moral questions at the core of their contribution. On the one hand, Barnum was offering them a much better living than they could have received in any other way during that era and was much less cruel to them than many of their contemporaries. He was also undeniably exploiting their suffering for cash, and what the movie describes as a “celebration of humanity” was to many 19th century consumers an easy way to poke fun at and feel superior to men and women who could be “othered.”

This is perhaps the most interesting story in “The Greatest Showman,” but it’s one that the musical never bothers telling. Aside from a single showstopping number “This Is Me” — and while the song is good, it is a standard empowerment piece that doesn’t address the specifics of its characters’ situation — this theme is almost entirely ignored. The closest it ever comes to having a meaningful confrontation with this issue is when Barnum recruits a reluctant Charles Stratton (later Tom Thumb) by inquiring, if people are going to laugh at you anyway, why not get paid for it? The fact that Barnum both has a valid point and is yet contributing to the way little people are brutally demeaned and dehumanized speaks to the central moral quandary that exists at the film’s soul. While this would merely be a storytelling shortcoming if “The Greatest Showman” was purely fictional, it becomes morally problematic considering that it exists to celebrate Barnum as both a pioneering entertainer and a lovable rogue.