Lily Salter's Blog, page 191

January 2, 2018

Orrin Hatch announces retirement, opening the door for Senator Mitt Romney

Orrin Hatch; Mitt Romney (Credit: AP/Colin E. Braley)

Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, has announced that he will not seek reelection in 2018.

“I was an amateur boxer in my youth, and I brought that fighting spirit with me to Washington. But every good fighter knows when to hang up the gloves. And for me, that time is soon approaching,” Hatch explained in a video statement.

He added, “That’s why, after much prayer and discussion with family and friends, I’ve decided to retire at the end of this term.”

An announcement from Senator Orrin G. Hatch. #utpol pic.twitter.com/UeItaLjR3j

— Senator Hatch Office (@senorrinhatch) January 2, 2018

Hatch has received intense criticism for his perceived obsequiousness toward President Donald Trump after the 2016 presidential election, with the Salt Lake Tribune even republishing a Washington Post editorial by Dana Milbank calling for Mitt Romney to oppose Hatch in the primary for that reason.

“Hatch was preparing to retire, but Trump pushed him to go back on his promise not to seek another term. Trump obviously prefers the obsequious Hatch to Romney, who, though as conservative as Hatch, would be no puppet. That’s why Mitt must run,” Milbank observed. That thought has been bouncing around Washington circles over the past few months, as Romney was denied a role in a Trump administration.

Source familiar with @MittRomney thinking says he has moved from WILLING to run towards WANTING to run in recent weeks. Putting pieces in place to pursue Utah senate seat.

— Garrett Haake (@GarrettHaake) January 2, 2018

A source with NBC News also reported that Trump repeatedly urged Hatch to run for reelection in 2018, even though Hatch is already the longest-serving Republican in the history of the Senate.

It is unclear whether Trump will support Romney if he becomes the Utah Senate candidate in 2018, given that the 2012 Republican presidential nominee delivered a speech in March 2016 denouncing Trump’s candidacy.

In addition to being Utah’s senior senator, Hatch is also Senate pro tempore, which places him third in line from the presidency after Vice President Mike Pence and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

Here’s America’s foreign policy under President Trump, in two stories

(Credit: AP/Manuel Balce Ceneta/KRT)

Overall, 2017 wasn’t a good year for the world. It was one of the hottest on record, and the leader of the world’s most powerful army spent a good chunk of it threatening a newly emerged nuclear power with the prospect of war.

It’s the latter part of that sentence that has many worried, but it’s also part of a larger trend.

When President Donald Trump assumed office last January, he came to the White House showing a clear lack of knowledge regarding international relations. Since then, Trump’s foreign policy has been less “learning on the fly” and more “is he learning anything?”

The latest example of Trump diplomacy comes from Politico, which reported on a dinner Trump had with Latin American leaders in September that ended with many in attendance worrying that the president was “insane.”

Over the course of the year, I have often heard top foreign officials express their alarm in hair-raising terms rarely used in international diplomacy—let alone about the president of the United States. Seasoned diplomats who have seen Trump up close throw around words like “catastrophic,” “terrifying,” “incompetent” and “dangerous.” In Berlin this spring, I listened to a group of sober policy wonks debate whether Trump was merely a “laughingstock” or something more dangerous. Virtually all of those from whom I’ve heard this kind of ranting are leaders from close allies and partners of the United States. That experience is no anomaly. “If only I had a nickel for every time a foreign leader has asked me what the hell is going on in Washington this year … ” says Richard Haass, a Republican who served in senior roles for both Presidents Bush and is now president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

While there’s hope that Trump may be a one-term wonder — an anomaly in global politics who Politico said is viewed as “essentially irrelevant” — the fact that he’s not showing leadership skills on the most basic level by getting other countries’ heads of state to simply like or tolerate him means that there may be a massive vacuum opening up on the international stage.

Enter China, which, per the New Yorker, has been waiting for just such a moment.

For years, China’s leaders predicted that a time would come—perhaps midway through this century—when it could project its own values abroad. In the age of “America First,” that time has come far sooner than expected.

For a real-world example of how Trump may have helped make China a major player, look no further than the president screaming that China should take responsibility of the North Korea situation, then getting upset when China acts in its own interests. Here is the president’s foreign policy: Ordering China to do something about North Korea, hoping from the sidelines that China would solve the North Korean situation, then getting frustrated when China doesn’t.

China has been taking out massive amounts of money & wealth from the U.S. in totally one-sided trade, but won't help with North Korea. Nice!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2017

China has been taking out massive amounts of money & wealth from the U.S. in totally one-sided trade, but won't help with North Korea. Nice!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2017

North Korea is behaving very badly. They have been "playing" the United States for years. China has done little to help!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 17, 2017

I explained to the President of China that a trade deal with the U.S. will be far better for them if they solve the North Korean problem!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 11, 2017

North Korea is looking for trouble. If China decides to help, that would be great. If not, we will solve the problem without them! U.S.A.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 11, 2017

Had a very good call last night with the President of China concerning the menace of North Korea.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 12, 2017

I have great confidence that China will properly deal with North Korea. If they are unable to do so, the U.S., with its allies, will! U.S.A.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 13, 2017

Why would I call China a currency manipulator when they are working with us on the North Korean problem? We will see what happens!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 16, 2017

China is very much the economic lifeline to North Korea so, while nothing is easy, if they want to solve the North Korean problem, they will

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 21, 2017

North Korea disrespected the wishes of China & its highly respected President when it launched, though unsuccessfully, a missile today. Bad!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 28, 2017

North Korea has shown great disrespect for their neighbor, China, by shooting off yet another ballistic missile…but China is trying hard!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 29, 2017

While I greatly appreciate the efforts of President Xi & China to help with North Korea, it has not worked out. At least I know China tried!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 20, 2017

North Korea has just launched another missile. Does this guy have anything better to do with his life? Hard to believe that South Korea…..

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 4, 2017

….and Japan will put up with this much longer. Perhaps China will put a heavy move on North Korea and end this nonsense once and for all!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 4, 2017

Trade between China and North Korea grew almost 40% in the first quarter. So much for China working with us – but we had to give it a try!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 5, 2017

Leaving Hamburg for Washington, D.C. and the WH. Just left China’s President Xi where we had an excellent meeting on trade & North Korea.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 8, 2017

I am very disappointed in China. Our foolish past leaders have allowed them to make hundreds of billions of dollars a year in trade, yet…

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 29, 2017

…they do NOTHING for us with North Korea, just talk. We will no longer allow this to continue. China could easily solve this problem!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 29, 2017

The United Nations Security Council just voted 15-0 to sanction North Korea. China and Russia voted with us. Very big financial impact!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 5, 2017

..North Korea is a rogue nation which has become a great threat and embarrassment to China, which is trying to help but with little success.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 3, 2017

President Xi of China has stated that he is upping the sanctions against #NoKo. Said he wants them to denuclearize. Progress is being made.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 11, 2017

Met with President Putin of Russia who was at #APEC meetings. Good discussions on Syria. Hope for his help to solve, along with China the dangerous North Korea crisis. Progress being made.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 12, 2017

Met with President Putin of Russia who was at #APEC meetings. Good discussions on Syria. Hope for his help to solve, along with China the dangerous North Korea crisis. Progress being made.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 12, 2017

China is sending an Envoy and Delegation to North Korea – A big move, we'll see what happens!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 16, 2017

Just spoke to President XI JINPING of China concerning the provocative actions of North Korea. Additional major sanctions will be imposed on North Korea today. This situation will be handled!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 29, 2017

The Chinese Envoy, who just returned from North Korea, seems to have had no impact on Little Rocket Man. Hard to believe his people, and the military, put up with living in such horrible conditions. Russia and China condemned the launch.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 30, 2017

And, of course, all these demands and complaints are met by inevitable disappointment from a man who seems to capable of little more than stewing in his feelings.

Caught RED HANDED – very disappointed that China is allowing oil to go into North Korea. There will never be a friendly solution to the North Korea problem if this continues to happen!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 28, 2017

Sooner rather than later, China’s economy will surpass that of the United States. With its newfound economic power, China has global ambitions that the U.S. doesn’t.

So far, Trump has proposed reducing U.S. contributions to the U.N. by forty per cent, and pressured the General Assembly to cut six hundred million dollars from its peacekeeping budget. In his first speech to the U.N., in September, Trump ignored its collective spirit and celebrated sovereignty above all, saying, “As president of the United States, I will always put America first, just like you, as the leaders of your countries, will always and should always put your countries first.”

China’s approach is more ambitious. In recent years, it has taken steps to accrue national power on a scale that no country has attempted since the Cold War, by increasing its investments in the types of assets that established American authority in the previous century: foreign aid, overseas security, foreign influence, and the most advanced new technologies, such as artificial intelligence. It has become one of the leading contributors to the U.N.’s budget and to its peacekeeping force, and it has joined talks to address global problems such as terrorism, piracy, and nuclear proliferation.

And China has embarked on history’s most expensive foreign infrastructure plan. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, it is building bridges, railways, and ports in Asia, Africa, and beyond. If the initiative’s cost reaches a trillion dollars, as predicted, it will be more than seven times that of the Marshall Plan, which the U.S. launched in 1947, spending a hundred and thirty billion, in today’s dollars, on rebuilding postwar Europe.

How close are we to seeing 2018 kick off a new world order led by China, and not the United States? There’s reason to believe that the coming decades will see China become a world leader in America’s absence. After all, that’s the intent.

By setting more of the world’s rules, China hopes to “break the Western moral advantage,” which identifies “good and bad” political systems, as Li Ziguo, at the China Institute of International Studies, has said. In November, 2016, Meng Hongwei, a Chinese vice-minister of public security, became the first Chinese president of Interpol, the international police organization; the move alarmed human-rights groups, because Interpol has been criticized for helping authoritarian governments target and harass dissidents and pro-democracy activists abroad.

Military power — known in international circles as “hard power” — is very easy to come by, actually. And the United States has the hard power advantage. The U.S. spends the most on its military, and it’s not even close.

But American hegemony only really works if the rest of the world wants to play along.

Social media anti-harassment strategies won’t stop trolls

(Credit: AP Photo/Richard Drew, File)

There’s a good chance that if you regularly spend time on the internet (and who doesn’t these days?), you may have been harassed. The Pew Research Center says 41% of Americans have been harassed online in some way, and about one in five people have been seriously harassed, like receiving “physical threats, harassment over a sustained period, sexual harassment or stalking.” And women are nearly twice as likely to say they’ve reported severe harassment online — frequently on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Entire internal task forces have been created to monitor and police the platforms, and they’ve repeatedly insisted that tackling this issue is a major priority.

But a recent study shows that as they attempt to quell hateful behavior on their platforms, Twitter and Facebook may actually be making thing worse.

They do try. If a woman encounters a troll on Facebook who makes incessant, lewd comments about her appearance, for example, she can follow the site’s instructions for reporting that user. The site will respond with a few scripted statements, programmed by a bot to classify her experience into one of a few categories. Then her complaint will disappear into the void, unlikely to garner a personalized response. With over a billion people on Facebook, it would be impossible to respond to every instance of harassment.

The study, from researchers at the University of Michigan School of Information and Sassafras Tech Collective, “finds that users of popular social media platforms — such as Facebook and Twitter—are frustrated when their harassment experiences aren’t taken seriously, especially when major companies rely on scripted responses that do not acknowledge individual experiences or the impacts of harassment, which include personal or professional disruptions, physical and emotional distress, and self-censorship or withdrawal.”

As one study participant explained, the reporting process can feel meaningless. “There’s really no point in reporting stuff on social media . . . either they had their account indefinitely suspended, or just suspended until they took the tweet down.” Another participant reported an image from Twitter of a man pointing at a sniper on a rooftop, which she had been sent directly. After she reported the tweet, she said, “We did ask Twitter to take that down, and they did — but I don’t know what they did with the person who posted it.”

What was especially frustrating to those who reported harassment on Twitter or Facebook was being told by the website’s community managers that their experience didn’t actually violate the site’s policies. This is fairly common: of the 11 people who experienced social media harassment and were interviewed by researchers for the study, seven said they faced a dead-end when they complained to the websites.

“What I think was really frustrating was the level of what people could say and not be considered a violation of Twitter or Facebook policies,” one person said. “That was actually really scary to me — if they’re just like, ‘You should shut up and keep your legs together, whore,’ that’s not a violation because they’re not actually threatening me. It’s really complicated and frustrating, and it makes me not interested in using those platforms.”

This poor response from Twitter and Facebook has a serious negative impact on the people who feel harassed. The study’s researchers say that to heal this broken system, social media platforms need “a more democratic, user-driven approach to defining and managing abusive behaviors online.” This year alone, Twitter and Facebook have been criticized for allowing hate groups and white supremacists to broadcast their messages widely. Both have since taken steps to address the issue, and the publicity has been a small silver lining for those who study harassment.

“I think increased pressure on platforms like Twitter and Facebook to remove white supremacists from their platforms will ultimately benefit people experiencing harassment of all kinds,” said Lindsay Blackwell, lead researcher on the study. “Social media platforms have always operated under a veil of neutrality, and it’s becoming increasingly clear that these companies will need to take a stand on major issues and rewrite their policies accordingly.” It’s time these sites find more human ways to tackle online harassment, beyond just a heartless auto-response.

Liz Posner is a managing editor at AlterNet. Her work has appeared on Forbes.com, Bust, Bustle, Refinery29, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter at @elizpos.

When nursing homes push out poor and disabled patients

(Credit: AP)

Anita Willis says the social worker offered her a painful choice: She could either leave the San Jose, Calif., nursing home where she’d spent a month recovering from a stroke — or come up with $336 a day to stay on.

She had until midnight to decide.

Willis’ Medicaid managed-care plan had told the home that it was cutting off payment because she no longer qualified for such a high level of care. If Willis, 58, stayed and paid the daily rate, her Social Security disability money would run out in three days. But if she left, she had nowhere to go. She’d recently become homeless after a breakup and said she couldn’t even afford a room-and-board setting.

In tears, she said, she agreed to leave. Thus began a months-long odyssey from budget motels to acquaintances’ couches to hospital ERs — at least five emergency visits in all, she said. Sometimes, her 25-year-old daughter drove down from Sacramento, and Willis slept in her daughter’s car.

“They kicked me out in the cold,” said Willis, a former Head Start teacher.

Complaints about allegedly improper evictions and discharges from nursing homes are on the rise in California, Illinois and other states, according to government data. These concerns are echoed in lawsuits and by ombudsmen and consumer advocates.

In California alone, such complaints have jumped 70 percent in five years, reaching 1,504 last year, said Joseph Rodrigues, the state-employed Long-Term Care Ombudsman, who for 15 years has overseen local ombudsman programs, which are responsible for resolving consumer complaints.

Around the country, ombudsmen say many patients like Willis end up with no permanent housing or regular medical care after being discharged. Even when the discharges are deemed legal, these ombudsmen say, they often are unethical.

“Absolutely, it’s a growing problem,” said Leza Coleman, executive director of the California Long-Term Care Ombudsman Association. Coleman says the practice stems from skilled nursing facilities’ desire for better compensation for their services and from the shortage of other affordable long-term care options that might absorb less severe cases.

In Willis’ case, she ultimately lost her appeal to return to the nursing home, Courtyard Care Center. A state hearing judge determined that she had left the home voluntarily because she refused the opportunity to pay to remain there.

Top administrators at Sava Senior Care, which owns Courtyard, did not return repeated calls for comment.

Among other recent cases of allegedly improper discharges:

In October, California’s attorney general moved to prevent a Bakersfield nursing home administrator from working with elderly and disabled people, while he awaits trial on charges of elder abuse and wrongful discharge. State prosecutors said one patient was falsely informed that she owed the home money, then sent to an independent living center even though she could not “walk or toilet on her own.” The administrator did not return messages left at the nursing home.

A pending lawsuit by Maryland’s attorney general alleges a nursing home chain, Neiswanger Management Services (NMS), illegally evicted residents, sending them to homeless shelters or other inadequate facilities to free up bed space for higher-paying patients. NMS countersued state regulators, alleging they are trying to drive the chain out of business.

Last month, a 73-year-old woman with diabetes and heart failure sued a Fresno, Calif., nursing home for allegedly leaving her with an open wound on a sidewalk in front of a relative’s home. The suit said conditions in the residence were unsafe and a family member refused to allow her inside. The state cited the home in July and issued a $20,000 fine.

Of course, not all complaints or lawsuits are well-founded. Federal law allows a nursing home to discharge or evict a patient when it cannot meet the resident’s needs or the person no longer requires services; if the resident endangers the health and safety of other individuals; or if the patient has failed, after reasonable and appropriate notice, to pay.

The law also generally requires a home to provide 30 days’ notice before discharging a patient involuntarily and requires all discharges be safe and orderly.

Deborah Pacyna, spokeswoman for the California Association of Health Facilities, a trade organization that represents nursing homes, questions why nursing homes should be responsible for providing a safety net for the indigent and homeless.

“Nursing home residents reflect society,” she said in a written statement. “Some nursing home residents live in homeless shelters or hotels. They may request that they go back ‘home,’ or to their local shelter or hotel upon discharge. We must honor their choices as long as their needs are met.”

Pacyna also noted that eviction and discharge complaints represent a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of residents released from the state’s nursing homes each year.

Nationally, discharge and eviction complaints have remained more or less steady in recent years after rising significantly between 2000 and 2007, according to data collected by the federal government. Still, these complaints remain the top grievance reported to nursing home ombudsmen as the number of overall complaints about everything from abuse to access to information has dropped in the past decade.

The rate of complaints can vary considerably by state. Jamie Freschi, the Illinois state ombudsman, says discharge and eviction complaints have more than doubled in her state since 2011.

She recalled one wheelchair-bound nursing resident who was in severe pain from osteoarthritis, scoliosis and fibromyalgia when she was discharged from a nursing home and sent to a homeless shelter. After the shelter rejected her because it could not accommodate her wheelchair, the resident went to a motel, which kicked her out when she ran out of money. She has since cycled between the emergency room and the streets, Freschi said.

“It’s an example of a really, really broken system, all the way around,” Freschi said.

Advocates say such decisions are often money-driven: Medicare covers patients for just a short time after they are released from hospitals. After that, these critics say, many nursing homes don’t want to accept the lower rates paid by Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income residents.

Even when they appeal and win, advocates say, it doesn’t always help the patient. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has advised California on two occasions — including this past summer — that it must enforce decisions from appeals hearings. (The state contends that it uses a variety of strategies to enforce the law.)

Last month, the California Long-Term Care Ombudsman Association joined with the legal wing of the AARP Foundation to sue a Sacramento nursing home, alleging it had improperly discharged an 83-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s — requiring the nursing home to readmit her.

“The facilities are getting the message that they don’t have to follow the rules here, so they’re emboldened,” said Matt Borden, a San Francisco attorney helping with the lawsuit.

Willis and her advocates were convinced that Courtyard Care Center broke the rules in her case.

Willis “did not leave Courtyard ‘voluntarily’ in just about any sense of the word,” said Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney with California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform.

At a hearing in April, held at the nursing home and attended by a reporter, Chicotel and an ombudsman argued that Willis’ discharge violated legal requirements, including lack of written notice. They asked that she be immediately readmitted.

According to hearing documents, Willis’ documented medical problems were many: an aneurysm, an ulcer, difficulty walking, muscle weakness, gastritis, anemia and heart and kidney disease. During her stay at the nursing home, she said, she’d fallen and hit her head while visiting the doctor, resulting in a severe concussion.

For their part, Courtyard staffers explained that Medicaid wouldn’t cover Willis anymore based on their assessment of her condition. They said she had “almost returned to her prior level of functioning.”

During the hearing, Willis repeatedly told those in attendance that she felt dizzy and nauseated. Her head pounded. “I’m not good,” she said. Afterward, she begged for a ride to the emergency room, where she was admitted with a torn aorta and bleeding ulcer.

She was still in the hospital when the hearing officer issued her decision a few days later. Eventually, she was released to another nursing home, which also discharged her after a month, she said. Then she resumed sleeping on friends’ couches. She chose not to file another appeal.

“This time in my life,” Willis said, “it’s very discouraging.”

What #MeToo can teach the labor movement

(Credit: AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

My first #MeToo memory is from the kitchen of the Red Eagle Diner on Route 59 in Rockland County, N.Y. I was 16 years old, had moved out of my home, and was financially on my own. The senior waitresses in this classic Greek-owned diner schooled me fast. They explained that my best route to maximum cash was the weekend graveyard shift. “People are hungry and drunk after the bars close, and the tips are great,” one said.

That first waitressing job would be short-lived, because I didn’t heed a crucial warning. Watch out for Christos, a hot-headed cook and relative of the owner. The night I physically rebuffed his obnoxious and forceful groping, it took all the busboys holding him back as he waved a cleaver at me, red-faced and screaming in Greek that he was going to kill me. The other waitress held the door open as I fled to my car and sped off without even getting my last paycheck. I was trembling.

Although there were plenty of other incidents in between, the next time I found myself that shaken by a sexual assault threat, I was 33 and in a Manhattan cab with a high-up official in the national AFL-CIO. He had structural power over me, as well as my paycheck and the campaign I was running. He was nearly twice my age and size. After offering to give me a lift in the cab so I could avoid the pelting rain walking to the subway, he quickly slid all the way over to my side, pinned me to the door, grabbed me with both arms and began forcibly kissing me on the lips. After a determined push, and before getting the driver to stop and let me out, I told the AFL-CIO official that if he ever did it again I’d call his wife in a nanosecond.

These two examples underscore that behind today’s harassment headlines is a deeper crisis: pernicious sexism, misogyny and contempt for women. Whether in in our movement or not, serious sexual harassment isn’t really about sex. It’s about a disregard for women, and it shows itself numerous ways.

For the #MeToo moment to become a meaningful movement, it has to focus on actual gender equality. Lewd stories about this or that man’s behavior might make compelling reading, but they sidetrack the real crisis — and they are being easily manipulated to distract us from the solutions women desperately need. Until we effectively challenge the ideological underpinnings beneath social policies that hem women in at every turn in this country, we won’t get at the root cause of the harassment. This requires examining the total devaluation of “women’s work,” including raising and educating children, running a home and caring for the elderly and the sick.

It’s time to dust off the documents from the nearly 50-year-old Wages for Housework Campaign. The union movement must step in now and connect the dots to real solutions, such as income supports like universal high-quality childcare, free healthcare, free university and paid maternity and paternity leave. We need social policies that allow women to be meaningful participants in the labor force — more of a norm in Western Europe where unionization rates are high.

Sexist thought is holding our movement back

Sexist male leadership inside the labor movement is a barrier to getting at these very solutions. This assertion is sure to generate a round of, “She shouldn’t write that, the bosses will use it against us.” Let’s clear that bullshit out of the way: We aren’t losing unionization elections, strikes and union density because of truth-telling about some men in leadership who should be forced to spend out their years cleaning toilets in a shelter for battered women. And besides, we all know the bosses are far, far worse — and have structural power over tens of millions of women in the United States and beyond.

Some of the sexual harassers who see women as their playthings are men on “our side” with decision-making roles in unions. This mindset rejects real organizing, instead embracing shallow mobilizing and advocacy. It rejects the possibility that a future labor movement led by women in the service economy can be as powerful as the one led by men in the last century who could shut down machines. Factories, where material goods are produced by blue collar men are fetishized. Yet, today’s factories — the schools, universities, nursing homes and hospitals where large numbers of workers regularly toil side by side — are disregarded, even though they are the key to most local economies. Educators and healthcare workers who build, develop and repair humans’ minds and bodies are considered white and pink collar. This workforce is deemed less valuable to the labor movement, because the labor it performs is considered women’s work.

While presenting on big healthcare campaign wins at conferences, I’ve had men who identify as leftists repeatedly drill me with skeptical questions such as, “We thought all nurses saw themselves as professionals; you’re saying they can have class solidarity?” I wonder if these leftists missed which workers got behind the Bernie Sanders campaign first and most aggressively. I’ve hardly ever met a nurse who didn’t believe healthcare is a right that everyone deserves, regardless of ability to pay.

When I began negotiating hospital-worker contracts, which often included the nurses, I routinely had men in the movement say things like, “It’s great you love working with nurses. They are such a pain in the ass at the bargaining table.” These derogatory comments came from men who can’t stand empowered women who actually might have an opinion, let alone good ideas, about what’s in the final contract settlement. Many hold a related but distinct assumption: that the so-called private sector is more manly — and therefore, important — than the so-called public sector, which is majority-women. This belief also contributes to the devaluation of feminized labor.

Capitalism is one economic system, period. The fiction of these seemingly distinct sectors is primarily a strategy to allow corporations to feed off the trough of tax-payer money and pretend they don’t. This master lie enables austerity, which is turning into a tsunami post-tax bill. And yet white, male, highly educated labor strategists routinely say that we need totally different strategies for the public and private sectors. Hogwash.

This deeply inculcated sexist thought — conscious or not — is holding back our movement and contributing to the absurd notion that unions are a thing of the past. These themes are discussed in my book “No Shortcuts, Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age” (Oxford, 2016).

The union movement has increased the number of women and people of color in publicly visible leadership positions. But the labor movement’s research and strategy backrooms are still dominated by white men who propagate the idea that organizing once worked, yet not anymore. This assertion is presented as fact rather than what it is: a structuralist argument. The erosion of labor law, relocation of factories to regions with few or no unions, and automation are the common reasons put forth. The argument omits the devastating failure of business unionism, and its successor — the mobilizing approach, where decision-making is left in the hands of mostly white male strategists while telegenic women of color with “good stories” are trotted out as props by communications staffers.

If you think these men are smarter than the millions of women of color who dominate today’s workforce, then an organizing approach — which rests the agency for change in the hands of women — is definitely not your preferred choice. Mobilizing, or worse, advocacy, obscures the core question of agency: Whose is central to the strategy war room and future movement? As for loud liberal voices — union and nonunion — that declare unions as a thing of the past, the forthcoming SCOTUS ruling on NLRB v Murphy Oil will prove most of the nonunion “innovations” moot. Murphy Oil is a complicated legal case that boils down to removing what are called the Section 7 protections under the National Labor Relations Act, and preventing class action lawsuits.

Murphy Oil blows a hole through the legal safeguards that non-union workers have enjoyed for decades, eviscerating much of the tactical repertoire of so-called Alt Labor, such as class-action wage-theft cases, and workers participating in protests called by nonunion community groups in front of their workplaces. The timing is horrific and uncanny: As women are finally finding their voices about sexual harassment at work, mostly in nonunion workplaces (as the majority are), Murphy Oil will prevent class action sexual harassment lawsuits.

Unions can’t win without reckoning with sexism and racism

The central lesson the labor movement should take from the #MeToo movement is that now is the time to reverse the deeply held notion that women, especially women of color, can’t build a powerful labor movement. Corporate America and the rightwing are out to destroy unions, in part, so that they can decimate the few public services that do serve working-class families, including the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security and public schools. Movements won these programs when unions were much stronger. It makes sense that unions, and the women’s movement, should throw down hardest to defend and grow these sectors, largely made up of women, mostly women of color, who are brilliant strategists and fighters.

The labor movement should also dispense of the belief that organizing and strikes can’t work. It’s self-defeating. Unions led by Chicago teachers and Philadelphia and Boston nurses, to name a few, prove this notion wrong. The growing economic sectors of education and healthcare are key. These workers have structural power and extraordinary social power. Each worker can bring along hundreds more in their communities.

Another key lesson for labor is to start taking smart risks, such as challenging the inept leadership in the Democratic Party by running its own pro-union rank-and-file sisters in primaries against the pro-corporate Democrats in safe Democratic seats, a target-rich environment. As obvious as it might sound, this strategy is heresy in the labor movement. Women who marched last January should demand that gender-focused political action committees, such as EMILY’s list, use support for unionization as a litmus test for whether politicians running for office will get their support. No more faux feminist Sheryl Sandberg types.

It’s time for unions to raise expectations for real gender equality, to channel the new battle cry to rid ourselves of today’s sexual harassers into a movement for the gender justice that women in Scandinavian countries and much of Western Europe enjoy. To think of winning what has become almost normal gains in many countries — year-long paid maternity and paternity leave, free childcare, healthcare and universities, six weeks’ annual paid vacation — is not pie-in-the-sky. To fight for it, people have to be able to imagine it.

The percentage of workers covered by union-negotiated collective agreements in much of Western Europe, the countries with benefits women in this country desperately need, is between 80 percent and 98 percent of all workers. This compares to a paltry 11.9 percent in the United States, as of 2013. This is far beyond a phased-in raise to $15 and hour — still basically poverty, and a wage that most women with structural power in strategic sectors already earn.

Women can’t win without building workplace power

There’s enough wealth in this country to allow the rich to be rich and still eradicate most barriers to a genuine women’s liberation, which starts with economic justice in the workplace. Upper-class mostly white women drowned out working-class women, many of color, in the 1960s and 1970s. The results of second-wave feminism are clear: Even though some women broke corporate and political glass ceilings and won a few favorable laws, individual rights will not truly empower women. Unions — warts and all — are central to a more equal society, because they bring structural power and collective solutions to problems that are fundamentally societal, not individual.

Women in the United States are stuck with bosses who abuse them, because to walk out could mean living in their cars or on the streets — or taking two full-time jobs and never spending a minute with their kids. Similarly, women are stuck in abusive marriages, because the decision to stop the beating means living on the streets. European women from countries where union contracts cover the vast majority of workers don’t, to the same extent, face the decision of losing their husband’s healthcare plan, or not having money to pay for childcare or so many of the challenges faced by women here. This country is seriously broken, and to fix it we must build the kind of power that comes with high unionization rates, which translate into political — not just economic — power.

Naming and shaming is not sufficient. Women need to translate the passion of this moment into winning the solution that will help end workplace harassment. A good union radically changes workplace culture for the better. The entire concept of a human resources office changes when a union is present. For example, when entering the human resources office, women aren’t alone: They’ve got their union steward. Union contracts effectively allow women to challenge bosses without being fired. Good unions do change workplace culture on these and many issues. Why else would the men who control corporations, and now the federal and most state governments, spend lavishly on professional union busters and fight so damn hard to destroy unions?

It’s going to take a massive expansion of unions again — like what happened in the 1930s, the last time unions were declared dead — before we can translate #MeToo into a demand that raises all workers’ expectations that this country can be a far more equal society. If we commit to this goal, we can achieve it. This time, the people leading the unions will be the same people who saved the nation from Roy Moore, because women of color are already at the center of the future labor force.

I went from sexual harassment in male-heavy restaurant kitchens to sexual harassment as a rare woman allowed into the kitchen cabinet of many successful campaigns. Whether it is union leaders ignoring the experience and genius of workers in today’s strategic employment sectors of education and healthcare, politicians following the corporate line or individual bad bosses harassing their employees, all of it comes down to a disrespect and disregard for women, especially women of color. If we focus on the power analysis, the answer is staring us in the face. There is no time to waste. Everyone has to be all-in for rebuilding unions.

January 1, 2018

Tiny computers are transforming weather data collection

(Credit: Dusty Compton/The Tuscaloosa News, via AP, File)

Imagine you’re a farmer in a developing country, and not only do you have no way to measure the amount of rain you received this month or this year, but you also have zero knowledge of past trends. Outside of anecdotal knowledge, or what your neighbor or grandfather tells you, you’re running a business blindly.[image error]

This is what many farmers struggle with in developing countries, where weather information is sparse. Most weather stations carry a high cost, which limits the total number a developing country can purchase, even before maintenance and security become problems, as they often do in rural areas.

In addition to thermometers and barometers to gauge temperature and pressure, weather stations are installed with a large battery and a solar panel, so that data can be continuously recorded over long periods. Exposure to the elements (wind, moisture, temperature fluctuations) reduces the lifetime of the weather station, and its parts eventually need to be replaced. Furthermore, weather stations need to be secured against looters and human interference. In the course of my research, I’ve gone to collect data from a rain gauge and found that someone had used it as a can for target practice, rendering my data useless, and the station in need of a replacement. In remote areas, people also often distrust or do not understand the weather station itself, asking, “what is this device, why is it here, and why is the government spying on me?”

Now imagine if you could give developing countries the tech for low-cost weather stations, made with a 3D printer and run with a computer that costs around $20. Imagine the huge influx of weather information that would follow, helping farmers plan crops and scientists learn more about storms. This is the type of revolution taking place thanks to the development of single-board computers (SBCs).

Handheld weather stations

A functional computer built on a single circuit board, SBCs generally look like a computer chip, with a dark green or blue color and silver metallic connectors on top, and can usually fit in the palm of your hand. The simplest model costs around $5, and ranges up to $35 for a SBC with more connections pre-installed.

Computer hobbyists have been tinkering with SBCs for a few decades, taking advantage of how they condense all the necessary features, including microprocessors, memory, etc. They’re ideal for learning to program, and have become popular with amateur robot and game makers. Many companies sell and develop these low-cost, miniature computers, with names like “Raspberry Pi” and “Beaglebone”; many also sell attachment boards for whatever purpose you can imagine: temperature sensors, LED lighting, moveable parts, and more. As SBCs have become more popular, with a growing open-development community, they’ve also become increasingly useful.

This weather station initiative to adapt SBCs is taking place around the world, orchestrated largely by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Their initial effort has focused on Africa, with the first weather stations installed in Zambia. Stations have also been installed in Barbados, Curacao, and Kenya, with planned near-future development in Western and Southern Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin America.

In order to forecast the weather next week, the model needs to know conditions right now

This effort is important because weather forecast models require initial conditions; in order to forecast the weather next week, the model needs to know what conditions are like right now. However, large gaps in weather information decrease the validity of weather forecasts worldwide. Such gaps exist over large expanses of ocean, for example, where no land exists for a surface weather station. Other gaps exist in developing countries where the technology isn’t readily available or is too expensive.

NCAR’s toolkit only has a few, cheap ingredients: a 3D printer, PVC pipes, commercially available SBCs, their adaptors, a solar panel, and a battery. With these, NCAR has created a 3D-printed weather station system that locals can quickly deploy on the ground. They provide 3D printer blueprints for the weather stations, the 3D printer, and training. This helps not only the country and its citizens, but forecasting ability worldwide. And NCAR is not just providing weather stations to developing countries, they’re teaching residents how to build and maintain a weather network to increase their information.

More data > costly data

I myself have ventured into the world of adapting SBCs for science. In my research, I grapple with the wind, rain, and sun, and in order to observe atmospheric properties, I need my instruments directly exposed to those elements. You wouldn’t take your brand new shiny Macbook Air to the beach, never mind into the water for a swim, would you? The sun heats up the electrical components, water and electronics don’t mix, and wind blows dust and debris into your system. And though our instruments are designed to take some environmental abuse, they can only suffer so much. Given the choice, I’d rather install a number of SBCs with attachments, totaling at most $300 each, rather than one piece of equipment that costs over $10,000.

Scientists take several factors into consideration when deciding on their tools. For one, SBCs have shorter lifetimes than more high-tech equipment, and they are more fragile or vulnerable to the environment; an SBC left outside may only last one year instead of 10. Secondly, SBCs do not yet leave the store shelf ready to use in research, so scientists need some extra technical skill and time to adjust the device. And lastly, results drawn from an SBC will need to be verified with higher-tech solutions. Still, even with these considerations, I’d rather learn the technology myself, install 10 SBC systems outside to observe the atmosphere, and use the additional information provided by 10 SBCs, to ensure that despite a potentially lower data quality, the quantity of data (10 sources to one) increases the overall value of the research study. We may currently be missing out on important data that requires sophisticated tools — and is expensive to collect — but with new low-tech solutions, science can benefit from a larger trove of information.

Sea-salt aerosol causes hazardous haze and accelerates rust, and may make rain form faster

In my research, the size distribution of sea-salt aerosols, or the sizes of tiny sea spray droplets, is extremely difficult to measure. Most people who live on a coast know that sea-salt aerosol particles in the atmosphere affect visibility and metallic corrosion. Sea-salt aerosol is responsible for the haziness that makes sea-travel hazardous, for example, and an abandoned car next to the beach rusts far sooner than one in a desert. Furthermore, and of great interest to me, there are also some studies showing that sea-salt aerosols can affect the development of precipitation in shallow clouds. Because sea-salt attracts water, sea-salt aerosols in the atmosphere may be able to make rain form faster.

Researchers cannot measure the aerosols from a distance, or what in atmospheric science is called “remote sensing.” They need to measured in-situ, in the place where the aerosols exist, and the same corrosion that affects boats and cars affects the devices designed to measure the sea-salt matter.

Flying for science

Currently the best technology to sample sea-salt aerosol size distribution needs to be flown on a research aircraft, cruising close to the surface of the sea to take samples. The instrument hangs under the wing of an aircraft, usually a GV or C-130, in a pod, and looks something like a weapon if you didn’t know better. Due to the expense of flight and the limited time the aircraft spends in one location, the measurements are instantaneous in time and space — and inherently limited. I’ve recently been funded for a small National Science Foundation (NSF) exploratory grant to resolve this problem, and to develop a new system.

I proposed to do this using SBCs deployed on a kite platform, to make it easier to sample the sea-salt aerosols — meaning a literal kite, with wind and an electric fishing reel, so I don’t have to manually pull 1km worth of line. Living in Hawaii, I can take my kite to the windward shore anytime, and reduce the cost of technology by using SBCs. I hope that in the future the technology will also be used on drones or small quadcopters.

The project means that researchers like me can sample aerosols more frequently, in more places around the world, increasing what we know about their size distributions and their impacts. For example, the size of the sea-salt aerosol determines how it affects visibility. Knowing what conditions create many small droplets versus a few larger ones can help us to forecast visibility more accurately and keep mariners and aviators safe.

The lessons we’re gaining from SBCs in weather science can be incredibly powerful, and could revolutionize many aspects of life. Wouldn’t it be neat if every single person had a tiny weather station on their roof? Wouldn’t it be powerful to be able to trust a forecast more than five days out?

Thirty years ago, computers were bulky and expensive. Today they’re getting smaller and stronger. The integration of advancing technology into science fields often lags the capability, but SBCs are working their way into all sorts of science fields, especially atmospheric science research. Low-tech is the new high-tech, to the benefit of atmospheric science.

4 Reasons for a surprising change in racial incarceration trendlines

(Credit: Shutterstock)

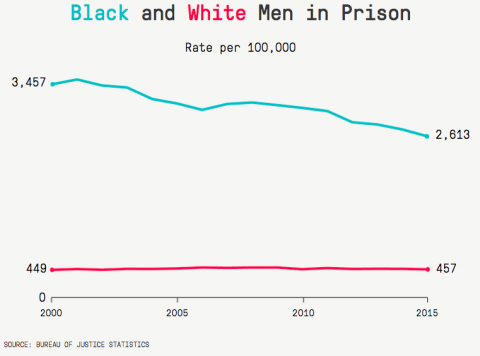

It’s long been a given that racial disparities plague the nation’s criminal justice system. That’s still true — black people are incarcerated at a rate five times higher than that of white people — but the disparities are decreasing, and there are a number of interesting reasons behind the trend.

It’s long been a given that racial disparities plague the nation’s criminal justice system. That’s still true — black people are incarcerated at a rate five times higher than that of white people — but the disparities are decreasing, and there are a number of interesting reasons behind the trend.

That’s according to a report released this month by the Marshall Project, a non-profit news organization that covers the U.S. criminal justice system. Researchers reviewed annual reports from the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics and the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting system and found that between 2000 and 2015, the incarceration rate for black men dropped by nearly a quarter (24 percent). During the same period, the white male incarceration rate bumped up slightly, the BJS numbers indicate.

When it comes to women, the numbers are even more striking. While the black female incarceration rate plummeted by nearly 50 percent in the first 15 years of this century, the white rate jumped by a whopping 53 percent.

Make no mistake: Racial disparities in incarceration haven’t gone away. As the NAACP notes, African Americans account for only 12 percent of the U.S. population, but 34 percent of the population in jail or prison or on parole or probation. Similarly, black children account for 32 percent of all children who are arrested and more than 50 percent of children who are charged as adults.

When it comes to drugs, the NAACP reports, African Americans use drugs in proportion to their share of the population (12.5 percent), but account for 29 percent of all drug arrests and 33 percent of state drug prisoners. Black people still bear the heaviest burden of drug law enforcement.

Still, that 5:1 ratio for black vs. white male incarceration rates in 2015 was an 8:1 ratio 15 years earlier. Likewise, that 2:1 ration for black vs. white female incarceration rates was a 6:1 ratio in 2000.

“It’s definitely optimistic news,” Fordham University law professor and imprisonment trends expert John Pfaff told the Marshall Project. “But the racial disparity remains so vast that it’s pretty hard to celebrate. How, exactly, do you talk about ‘less horrific?'”

It behooves analysts and policy-makers alike to try to make sense of the changing complexion of the prison population, but that’s no easy task.

“Our inability to explain it suggests how poorly we understand the mechanics behind incarceration in general,” Pfaff said.

Still, the Marshall Project wanted some answers, so it did more research and interviewed more prison system experts. Here are four theories, not mutually exclusive, that try to provide them.

1. Shifting drug war demographics

The black vs. white disparity in the prosecution of the war on drugs is notorious, and a central tenet of drug reform advocacy. But even though black Americans continue to suffer drug arrests, prosecutions, and imprisonment at a far greater rate than whites, something has been happening: According to BJS statistics, the black incarceration rate for drug offenses fell by 16 percent between 2000 and 2009; at the same time, the number of whites going to prison for drugs jumped by nearly 27 percent.

This could be because the drug crises of the day, methamphetamines and heroin and prescription opioid addiction, are problems mainly for white people. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, the drug crisis du jour was crack cocaine, and even though crack enjoyed popularity among all races, the war on crack was waged almost entirely in black communities. The war on crack drove black incarceration rates higher then, but now cops have other priorities.

The shift in drug war targeting could also explain the dramatic narrowing of the racial gap among women prisoners, because women prisoners are disproportionately imprisoned for drug crimes.

2. White people blues

Declining socioeconomic prospects for white people may also be playing a role. Beginning around 2000, whites started going to prison more often for property offenses, with the rate jumping 21 percent by 2009. Meanwhile, the black incarceration rate for property crimes dropped 9 percent.

Analysts suggest that an overall decline in life prospects for white people in recent decades may have led to an increase in criminality among that population, especially for crimes of poverty, such as property crimes. A much-discussed study by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found that between 1998 and 2013, white Americans were experiencing spikes in rates of mortality, suicide, and alcohol and drug abuse. That’s precisely when these racial shifts in imprisonment were happening.

And while African Americans also faced tough times, many whites were newer to the experience of poverty, which, in an explanation the Marshall Project says is “speculative,” could explain why drug use rates, property crime, and incarceration rates are all up:

“Perhaps, says Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, whites are just newer to the experience of poverty, which could explain why their rates of drug use, property crime and incarceration have ticked up so suddenly.”

3. Reform is more likely in the cities, where more black people live

Since the beginning of this century, criminal justice reform has begun to put the put brakes on the mass incarceration engine, but reforms haven’t been uniform. They are much more likely to have occurred in more liberal states and big cities than in conservative, rural areas. And while people are still being arrested for drugs at sky-high rates — more than 1.5 million drug arrests in 2016, according to the FBI — those reforms mean that fewer of them are ending up in prison.

In big cities such as Los Angeles and Brooklyn, new prison admissions have plummeted thanks largely to sentencing and other criminal justice reforms. But in counties with fewer than 100,000 residents, the incarceration rate was going up even as crime went down. In fact, people from rural areas are 50 percent more likely to be sent to prison than city dwellers.

Even in liberal states, the impact of reforms varies geographically. After New York state repealed its draconian Rockefeller drug laws, the state reduced its prison population more than any other state in the country in the 2000s. But the shrinkage came almost entirely from the far more diverse New York City, not the whiter, more rural areas of the state.

4. Crime has been declining overall

Arrests for nearly all types of crime rose into the mid-1990s, then declined dramatically, affecting African Americans more significantly than whites since they were (and are) more likely to be arrested by police in the first place. In the first decade of the new century, arrests of black people for violent offenses dropped 22 percent; for whites, the decline was 11 percent. Since those offenses are likely to result in substantial prison sentences, this shift has likely contributed to the changing racial makeup of the prison population.

Whatever the reason for the shrinking racial disparities in the prison population, there is a long way to go between here and a racially just criminal justice system. If current trends continue, it would still take decades for the disparities to disappear.

Who would pay $26,000 to work in a chicken plant?

(Credit: AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File)

The first week Yongho Yeom worked on the chicken line at the House of Raeford poultry plant was like nothing he had ever imagined as a computer engineer in South Korea.

The first week Yongho Yeom worked on the chicken line at the House of Raeford poultry plant was like nothing he had ever imagined as a computer engineer in South Korea.

Supervisors clocked him as he rapidly maneuvered scissors again and again to cut bones out of raw chicken thighs. The plant was cold to prevent spoilage. And the slaughtering of chickens created an awful stench.

“It hurt a lot,” Yeom said. “All of the Korean workers, we all had some sort of chronic symptoms or pain, and some would lose their nails.”

Yeom, now 46, had landed in South Carolina in 2015 after researching how to immigrate to the United States. At the time, he was living in Daejeon, a technology center about 90 miles south of Seoul and worried about the future of his two young daughters in Korea’s high-pressure education system, where many children spend additional hours each day in private “cram schools.” He also believed pollution blowing in from China was making him ill.

Online, he came across the website of a Korean migration agency, which said House of Raeford, a large chicken processor, was sponsoring foreign workers through a little-known green card program designed to fill unskilled jobs that U.S. employers say they can’t find American workers to do.

Over the past year, ProPublica has documented how chicken plants and other low-wage industries rely heavily on unauthorized immigrants and refugees, often mistreating them, and in some cases, using their immigration status to get rid of workers who are injured or fight for better conditions.

In the last few years, the nation’s poultry companies have found yet another way to get cheap and willing labor to do the grueling work of processing tens of thousands of chicken carcasses each day for fast-food restaurants and supermarkets across the country.

Ideally, the program, known by its category EB-3 (Other), could offer a lifeline for businesses facing legitimate labor shortages while providing a pathway to citizenship for unskilled immigrants. Companies that participate would need to show good-faith efforts to hire American-born workers first, improving wages and conditions in the process.

But as the program has accelerated in recent years, it has been co-opted by a handful of companies and foreign consultants who have used it to bring in immigrants willing to work for low pay in often-dangerous jobs. In the U.S., the program is now dominated by a handful of poultry processors with poor safety records, one janitorial firm and a single fast-food franchisee. Overseas, a cottage industry of migration agents has popped up charging steep fees for “migration assistance,” even as the law bars the selling of green card sponsorship and other recruiting fees.

And under the program, U.S. companies aren’t obligated to do much to first persuade Americans to take their jobs. They merely have to place two want ads seeking American workers in the local Sunday newspaper and a notice on the state jobs board — not raise pay or improve work conditions.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and the Labor Department have increased scrutiny of the unskilled green card program over the past year. But even now, House Republicans are pushing a bill that could help the meat and poultry industry bring in more than 10 times as many foreign workers a year with few of the protections provided by the green card program.

The bill would expand another visa program for agricultural guest workers to meat and dairy processors, which usually can’t obtain guest workers because their jobs aren’t seasonal. Instead, it would let them hire the workers year-round. The pay would be below the prevailing wage in many areas. And workers’ legal status would be tied to their employers, preventing them from quitting to seek higher wages or better conditions.

Unlike EB-3, guest worker programs for farmworkers (H-2A) and seasonal workers (H-2B), which are larger and receive more attention, do not provide a path to permanent residency or citizenship.

The unskilled green card program has remained little known in part because from 2001 until 2013, it was virtually closed, with waits of six to eight years to get a visa. But that year, the backlog started to clear, spurring aggressive advertising in South Korea, China and Vietnam.

Demand is now so high that some foreign migration consultants have developed a lucrative niche charging between $20,000 and $130,000 for assistance accessing the jobs offered by employers in the program, which usually pay less than $20,000 a year. Turning the common immigration narrative upside down, the program often attracts middle-class professionals, such as engineers like Yeom and office workers, who are willing to take a steep fall down the economic ladder for the chance to raise their children in the U.S.

Like unauthorized immigrants, EB-3 immigrants are similarly compelled to accept poor work conditions, often having made a one-year commitment in exchange for the green card sponsorship.

Jinhee Wilde, a Maryland immigration attorney, handles EB-3 cases for poultry processers like Case Farms, which was featured in an earlier story by ProPublica. The Labor Department has certified 568 foreign workers for Case Farms in the past three years.

Wilde says the program serves a legitimate need and that sponsorship carries enough costs and hurdles that employers wouldn’t do it if they didn’t have to. Many new hires in jobs like chicken processing leave after a few weeks or even just a few days, she said, but EB-3 workers agree to serve a much longer stint.

“Employers have a need for workers, whether unskilled work like chicken processing that no one wants to do it seems, or high-tech companies that need specialized skills,” she said. “Otherwise, the economy is going to come to a screeching halt.”

Critics say poultry companies could attract U.S. workers if they improved safety, decreased line speeds and paid a living wage.

“That’s why these jobs are so undesirable,” said Alex Galimberti, who leads the poultry worker campaign at Oxfam. “It is not surprising to me that some of the companies that are known as the lowest players in the industry, as far as working standards, are the same ones that are trying to take advantage of this visa program.”

“To me,” he added, “this just looks like a scheme to keep standards low.”

Beginning at the end of the Obama administration and accelerating under President Donald Trump, U.S. immigration agents and embassy officials have been clamping down on the program and increasing reviews of visa petitions, according to immigration attorneys, employers and foreign workers.

ProPublica also found a severe slowdown in the processing of applications at the Labor Department, where the number of decisions for unskilled jobs has been cut in half while the denial rate has nearly doubled. The freeze was even more evident for poultry jobs, where about six out of 10 applications were denied — more than triple the rejection rate from the year before.

A Labor Department spokesman said there has been no policy change under Trump, but couldn’t provide a reason for the slowdown. In response to questions, a spokeswoman for Citizenship and Immigration Services pointed to recent comments made by the agency’s new director, L. Francis Cissna, who said that the new scrutiny of visas “reflects our commitment to protecting the integrity of the immigration system.”

Wilde said immigration agents are questioning why white-collar Koreans would want to pay tens of thousands of dollars to cut chicken.

“They are sacrificing themselves for the futures of their children,” she said. “That is no different than any other immigrants in American history.”

Based in Rose Hill, North Carolina — home of the world’s largest frying pan — House of Raeford ranks among Apple, Google, Microsoft and Amazon as one of the biggest sponsors of green cards. The chicken processor, which employs 4,300 people at seven plants, has applied for 1,900 foreign workers in the last three years, according to Labor Department data. The company also ranks among the most dangerous poultry processors in the country, according to a ProPublica analysis of safety violations, with many workers suffering crippling hand injuries.

House of Raeford spokesman Dave Witter said that “plant locations and available labor pools” have forced the company to come up with various strategies to recruit workers. “We became aware of this federal program a few years ago,” he said, “and saw it as an opportunity to expand our search for viable candidates.”

Yeom said he paid $26,000 to the migration agency from his family’s savings and, in about a year, arrived at the plant where he started on the graveyard shift at $8.50 an hour, rising to $10.25 after the first three months. The rapid, repetitive motions were challenging, he said.

Several former EB-3 workers interviewed for the story had similar experiences. While the work was abhorrent and sometimes humiliating, they were willing to endure it because they had received the opportunity to become permanent U.S. residents and potentially citizens.

While the law doesn’t spell out how long immigrants have to stay with the sponsoring employer, some migration agents require workers to sign six-month or one-year contracts. Yeom said he didn’t have to, but still felt he had a duty to stick it out.

“I thought it was a promise, so I decided to keep the promise, and also, I thought about all the other Korean workers who are trying to come to the U.S.,” he said, “because if I quit prematurely, I thought it might somehow disadvantage my fellow Korean people.”

About 54 percent of all immigrants who received green cards through the program in fiscal year 2016 were from South Korea. Another 16 percent came from China.

The origins of the EB-3 program date back to the 1965 immigration act when Congress created a green card category for “skilled and unskilled workers in short supply.” Congress reorganized the immigration categories in 1990, but left a maximum of 5,000 green cards every year for jobs requiring no education and less than two years of training or experience.

The program became increasingly popular with chicken plants and middle-class Koreans in the 1990s. But a 2000 law, which created a short window for people who entered illegally or overstayed visas to apply for permanent residence, led to a flood of applications that virtually closed the program in the 2000s through the early part of this decade.

As the program began to reopen, migration agents in Korea, China and Vietnam saw an opportunity to advertise it as a fast track to the American dream, especially as fast-food franchisees began to seek workers for jobs at restaurants like Pizza Hut or Burger King.

“Your chance to immigrate is at your fingertips,” says one ad posted on the website of a Vietnamese migration agency. “People who have visited the United States all praise, admire and sigh in exclamation at the never-ending green,” touts another in China. “There are trees, grass, flowers everywhere.” “Do not miss this opportunity!” “Only $70,000 and you can apply for a U.S. green card and give yourself and your family a beautiful future!”

The law prohibits “the sale, barter or purchase” of labor certifications and requires employers to pay all fees associated with the applications. But the law leaves open fees related to “migration assistance,” such as explaining the different ways to immigrate to the United States, translating official paperwork and helping families get settled in a new country, said Wilde, the Maryland attorney.

Some foreign migration agencies, whose websites were translated by ProPublica, play by the rules, simply offering information about visa requirements and the community, schools, cost of living and apartment rentals around the sponsoring employers.

But other agencies cleverly disguise recruitment fees as “settlement services” or “assimilation packages,” charging inflated rates, said David Hirson, an immigration attorney in Costa Mesa, California. One ad in China, where demand for visas is so high that the wait under the program is 11 years, lists the going rate to migrate through Burger King and Pizza Hut at $130,000.

Hirson said any such fees to middlemen should be suspect because they are essentially reducing the foreign workers’ pay below the prevailing wage.

“They are effectively paying an agent to get them the job,” he said.

But Yeom didn’t see it that way.

Last year, after the savings he brought from Korea ran out, Yeom took on a second job at a fish market. He would come home from the chicken plant at 8 a.m., massage his hands with warm water, eat breakfast and go to the fish market, where he worked from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Then he’d return home, spend time with his kids and sleep for four to five hours before getting up for his midnight job at House of Raeford.

After 13 months at the chicken plant, Yeom quit and worked full time at the fish market. Seeing that business was good, he decided to open his own.

Walking with your doctor could be better than talking

(Credit: Getty/sturti)

Gyms across the country will be packed this week with people vowing to “get moving” to lose weight this year.

Much of the effort will be for naught. And, in fact, some of it could lead to injury and frustration.

Currently, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention exercise guidelines call for all individuals to do 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, or 75 minutes of high-intensity exercise per week. In addition, the CDC recommends two days of strength training, or muscle strengthening, for obese people.

I am a physician assistant and exercise physiologist from the Lifestyle Modification Clinic at UConn Health. Current recommendations seem extremely unrealistic, considering less than 10 percent of all individuals meet these criteria for exercise, even without the resistance exercises.

We’ve lost the focus on using the guidelines only as guidelines, and not individualizing an exercise prescription for our patients. We need to be smarter about prescribing it, and here’s why.

A customized approach

The medical profession has learned a few things in recent years about exercise and the obese and those who have become diabetic as a result. All exercise is not created equal, and neither are its benefits.

For those who want to burn fat, aerobic exercise is important. Fat metabolism is greatest during aerobic exercise which is achieved during moderate intensity exercise.

Type 2 diabetes is due to insulin resistance, so the exercise that is more effective to increase insulin sensitivity is more specific to the duration of the exercise than the intensity.

But overweight and obese people may not be able to do either of these without injuring themselves. The Hippocratic oath, whereby doctors pledge to first “do no harm,” gets lost with the prescription of exercise with most individuals. The risk of injury and noncompliance should be the first two things when discussing an exercise routine.

The risk of injury for all individuals, especially of the lower extremities, such as plantar fasciitis and knee pain, is up to four times greater doing high-intensity exercise, such as jogging compared to moderate intensity, such as walking. Obese individuals are at even greater risk.

The risk of injury drives noncompliance, especially with higher-intensity exercise. Educating patients about the benefits of breaking up prolonged sitting throughout the day has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity for diabetics which will help motivate them to start making little changes to start. This will allow them to make realistic changes and even those will have benefits.

Walking the walk

Understanding the importance of exercise, you would assume that physicians spend a lot of time counseling on exercise.

However, in 2010, fewer than 31 percent of physicians recommended physical activity for overweight and less than 47 percent for obese people during an office visit. This was an increase, however, from fewer than 17 percent for overweight and 35 percent for obese in 2000.

This could be partly due to how health care providers are educated, with less than 20 percent of medical schools in the U.S. even requiring one class in physical activity or exercise. More than half of the physicians trained in the United States in 2013 received no formal education in physical activity and may, therefore, be under prepared to properly advise about exercise.

Exercise has been shown to reduce the risk up to 50 percent for all people from becoming diabetic, and since obese individuals are at greater risk, they would benefit the most. For physicians, the challenge is how to help obese patients understand this and help them become more active.

The first thing is to educate our health care professionals during their medical education on exercise physiology and the medical importance of physical activity which will help them give an appropriate exercise prescription.

It has been shown that the more the physicians focus on exercise, the more likely patients will exercise.

Also, the more we doctors go into our “patient’s lifestyle” and find ways to get them moving more and being respectful of them, the more successful they will be. We need to get outside of our box of guidelines and listen to our patients. An example would be to go for a walk during their visits.

Patients walking with their doctors can help doctors assess patients’ fitness levels. Health care providers can assess whether patients have any limitations such as knee or back pain. They also can explain the difference between aerobic and anaerobic exercise, which is best done by explaining the “talk test”. If you can talk but not sing while exercising, you are maintaining aerobic metabolism, which burns fats and is good for weight loss. If you are unable to say more than a few words without pausing for a breath, you will then be exercising anaerobically and burning sugar.

Patients walking with their doctors can help doctors assess patients’ fitness levels. Health care providers can assess whether patients have any limitations such as knee or back pain. They also can explain the difference between aerobic and anaerobic exercise, which is best done by explaining the “talk test”. If you can talk but not sing while exercising, you are maintaining aerobic metabolism, which burns fats and is good for weight loss. If you are unable to say more than a few words without pausing for a breath, you will then be exercising anaerobically and burning sugar.

Brad Biskup, Coordinator of Lifestyle Medicine Clinic, University of Connecticut

New York in the 1960s: John Lindsay, Joe Namath and the rise of “Fun City”