Lily Salter's Blog, page 154

February 24, 2018

Bad bedside manna: Bank loans signed in the hospital leave patients vulnerable

(Credit: Getty/vm)

Laura Cameron, then three months pregnant, tripped and fell in a parking lot and landed in the emergency room last May — her blood pressure was low and she was scared and in pain. She was flat on her back and plugged into a saline drip when a hospital employee approached her gurney to discuss how she would pay her hospital bill.

Though both Cameron, 28, and her husband, Keith, have insurance, the bill would likely come to about $830, the representative said. If that sounded unmanageable, she offered, they could take out a loan through a bank that had a partnership with the hospital.

The hospital employee was “fairly forceful,” said Cameron, who lives in Fayetteville, Ark. “She certainly made it clear she preferred we pay then, or we take this deal with the bank.”

Hospitals are increasingly offering “patient-financing” strategies, cooperating with financial institutions to offer on-the-spot loans to make sure patients pay their bills.

Private doctors’ offices and surgery centers have long offered such no- or low-interest financing for procedures not covered by insurance, like plastic surgery, or to patients paying themselves for an expensive test or procedure with a fixed price.

But promoting bank loans at hospitals and, particularly, emergency rooms raises concerns, experts say. For one thing, the cost estimates provided — likely based on a hospital’s list price — may be far higher than the negotiated rate ultimately paid by most insurers. Sick patients, like Cameron, may feel they have no choice but to sign up for a loan since they need treatment. And the quick loan process, usually with no credit check, means they may well be signing on for expenses they can ill afford to pay.

The offers may sound like a tempting solution for scared, vulnerable patients, but they may not be such a great bargain, suggests Mark Rukavina, an expert in medical debt and billing at Community Catalyst, a Boston-based advocacy group.

His point: “If you pay zero percent interest on a seriously inflated charge, it’s not a good deal.”

How the loans work

Between higher deductibles and narrower networks, patients are paying larger portions of their medical bills. The federal government estimates consumers spent $352.5 billion out-of-pocket on health care in 2016.

But many patients have trouble coming up with cash to pay bills of hundreds or even thousands of dollars, meaning hospitals are having a harder time collecting what they believe they are owed.

To solve their problem, about 15 to 20 percent of hospitals are teaming up with lenders to offer loans, said Bruce Haupt, CEO of ClearBalance, a loan servicing company. He, along with many other analysts, expects that percentage to grow.

The process begins with a hospital estimate of a patient’s bill, which takes insurance coverage into account. A billing representative then lays out payment plans for the patient, often while he or she is still being treated.

A patient can then sign up for a loan, often without a credit check. Patients write smaller monthly checks to the lender, who has paid the hospital, while keeping a designated percentage of the bill as a fee.

Proponents view financing as a useful alternative to medical credit cards, which can surprise users with high interest rates. The partnerships are tempting for hospitals since they offload the need to administer monthly payment plans and collection efforts.

Federal law requires lenders be transparent about the loan terms, a protection that extends to consumers entering these health care arrangements. That means disclosure of interest rates, other fees and the payment schedule.

Even so, said Gerard Anderson, a Johns Hopkins health policy professor and an expert on health care pricing, “it’s an often gentler version of asking you to pay up.”

But an on-the-stretcher sell leaves patients little opportunity for due diligence.

“What’s the charge they’re using to determine what’s a reasonable amount to pay?” Anderson added.

Cameron was suspicious of the $830 estimate of her bill, since she had good coverage from her job at the University of Arkansas. She and her husband had extensive experience with the health care system and its costs. No one had ever asked her to pay upfront, even when her husband owed tens of thousands for cancer treatment.

“It just felt so uncomfortable to us that they would try to push us through a bank, which is designed to make a profit,” Cameron said.

A growth business with risk of default

At Florida-based Orlando Health, which works with ClearBalance, loans typically range from $3,000 to $7,000, said Michele Napier, the health system’s chief revenue officer. The highest debt a patient has taken on — about $13,000 — was because of a high-deductible plan, she said.

“All of a sudden a catastrophic event occurs, and to have $13,000 in the bank account is a lot to ask,” she said. “They’re able to spread those payments.”

Low-income patients without insurance likely will not need loans to finance large bills,because they should quality for aid from the hospital, or be treated as charity care, Napier said.

It’s a conversation that starts at registration, she added. “If a patient shares with us that they have no resources or limited resources to pay, we will provide information on our financial assistance and other programs including screening them for Medicaid.”

The idea is to foster open conversations about cost and help patients and doctors weigh their options, both financial and medical, said Rick Gundling, a senior vice president at the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a trade group.

“The patient may say, ‘Hey, do I need to do this knee surgery now? Can we wait until I save up, or do I have other options, like physical therapy?’” he said. “The doctor may say … let’s look at other options.”

But the loans can be a band-aid solution, leading vulnerable patients to sign up to pay far more than they should, said Kathleen Engel, a research professor of law at Boston-based Suffolk University and an expert in consumer credit and mortgage finance.

“The hospital potentially is charging the patient the full, what I would call ‘whack rate’ for their care,” she said. “They try to collect the debt.”

Since many of these loans come without credit checks or affordability tests, the odds are higher that a loan could be financially unwise, experts warn.

At ClearBalance, loans average about $1,700, Haupt said. In practice, that means some patients are financing $150 bills, while others have them for as large $50,000.

Default rates vary across the country, with the highest default rates — up to 1 in 5 patients — in places such as Texas and Louisiana. In other areas, closer to 6 or 7 percent of patients ultimately cannot pay off their loans.

“Some of these people are destined to default,” Engel said. “If you have to get a loan for $500 for medical care, that means you are really living at the margins.”

Cameron declined the loan — and chose not to hand over any other form of payment. She wanted to wait until she received her insurance statement.

In the end, the couple owed only $150, the copayment for an ER visit. “It felt to us like it could screw someone over who wasn’t aware about how to work that system,” she said, though she admitted to feeling intimidated as she lay on the stretcher.

She added: “It can be scary feeling like you owe someone money.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Alcohol probably makes it harder to stop sexual violence — so why aren’t colleges talking about it?

(Credit: Getty/Mixmike)

Several years ago, one of us (Dominic) was consulting with university administration on their sexual violence prevention program.

All colleges and universities that receive Title IX funding are federally mandated to offer intervention programs, where bystanders are trained to intervene in risky sexual situations. These programs aim to reduce campus sexual violence, as one in five college women say they’ve been a victim of sexual assault.

The good news is that studies show that such programs can help bystanders prevent sexual violence. The bad news is that risky sexual situations often involve alcohol, and there’s no research on how alcohol intoxication might influence bystanders’ ability to intervene. These programs weren’t designed to help bystanders compensate for the effects of alcohol on their decisions in these situations.

When I mentioned this problem, one administrator was shocked. Essentially, the university would be paying thousands of dollars for mandated prevention programming — with no evidence to suggest that it would help when students were drinking.

Unfortunately, the field remains where it was several years ago. Our latest work tries to finally understand how alcohol affects bystanders.

A narrow spotlight

One recent study indicates that bystanders are present for nearly 20 percent of sexual assaults, yet actually intervened in just 27 percent of those cases.

To intervene successfully, bystanders must make a series of decisions. Research suggests that at least half of campus sexual assaults involve alcohol use, and bystanders are likely drinking in these situations as well. We believe that alcohol intoxication inhibits these decisions and prevents bystanders from acting.

This is based largely on the premise that alcohol intoxication affects what people pay attention to in a situation. Think of attention as a spotlight. Sober people have a very wide spotlight. They can perceive a lot of information in their environment — both information that is significant and noticeable and information that’s easily overlooked. But when people are drunk, their attention narrows. They tend to consider only information that easily captures their attention.

Consider the decisions necessary for bystanders to effectively intervene.

First, a person must notice the risky situation. You cannot intervene to prevent sexual violence if you don’t see it. Signs of an unwanted sexual advance — like averted eye contact or polite resistance — are often subtle. Intoxicated individuals are more likely to “zone out” compared to their sober counterparts.

Second, bystanders must figure out if it’s appropriate to intervene in a given situation. It’s rare for bystanders to witness a rape in progress. They’re more likely to witness behavior that precedes the assault, such as inappropriate sexual conversations. Such signs can seem ambiguous, and it may be unclear to a bystander if someone’s sexual boundaries are being crossed. Alcohol can exacerbate that ambiguity, making it harder to pick up on the risk for sexual violence.

Even in ideal circumstances, it’s difficult for bystanders to accept the responsibility to act. When other people are around, an individual is less likely to intervene. There isn’t any research to directly show this, but we believe alcohol likely strengthens this “bystander effect” — the person will look to someone else to intervene, instead of taking action themselves.

After all that, bystanders must decide how to help. Most bystander intervention programs teach students a range of strategies, such as how to use humor to safely and effectively intervene.

But acute alcohol intoxication impairs our ability to solve problems, plan out our behavior and stick to it. Intoxicated bystanders who would otherwise have the skills and confidence to intervene are less able to effectively implement a plan of action.

What’s more, bystanders must overcome their fear of how others will perceive them. Men may feel that they shouldn’t intrude on another man’s “sexual conquest” or fear losing respect from male peers if they intervene. Alcohol likely heightens men’s focus on these barriers and makes intervention less likely.

Better training for bystanders

There is no research that addresses the role of alcohol on bystander intervention for sexual violence. However, we recommend that colleges and universities consider adapting their prevention strategies.

Even current bystander training programs that do include an alcohol component focus on how alcohol impacts victims and perpetrators of sexual violence, rather than bystanders. But we believe that these programs should also focus on how alcohol intoxication impacts bystanders themselves. Programs should discuss the potential impairing effects of alcohol and how to intervene effectively when drinking. (We are currently working on a pilot for such a program.)

Colleges should also examine their policies. Evidence shows that there are ways colleges can successfully limit heavy alcohol use, such as college bans or limits on alcohol, as well as restrictions on the number and type of alcohol outlets. If we’re correct that sober individuals are more likely to intervene than intoxicated individuals, then these approaches may, in turn, increase bystander intervention.

In the same vein, colleges could implement initiatives that ensure the presence of sober bystanders. For example, at Cornell University, a student-led group called “Cayuga’s Watchers” provides sober party monitors who serve as responsible — and sober — bystanders. Similarly, there are programs that train bar staff to be effective bystanders. Colleges could partner with local bars that are often frequented by students to train these staff, and thus make these venues safer for all patrons.

Dominic Parrott, Professor of Psychology, Georgia State University and Ruschelle Leone, Doctoral Candidate in Clinical Psychology, Georgia State University

Parkland shooting survivor to Melania Trump: Talk to Trump Jr. about cyberbullying

Melania Trump (Credit: AP/Evan Vucci)

Parkland shooting survivors continue to speak up on social media, asking lawmakers to leverage their authority and power to impose stricter gun control laws. On Friday, 14-year-old Lauren Hogg had a different request for First Lady Melania Trump though: teach your stepson, Donald Trump Jr., about cyberbullying.

“Hey @FLOTUS you say that your mission as First Lady is to stop cyber bullying, well then, don’t you think it would have been smart to have a convo with your step-son @DonaldJTrumpJr before he liked a post about a false conspiracy theory which in turn put a target on my back,” Lauren Hogg tweeted.

Hey @FLOTUS you say that your mission as First Lady is to stop cyber bullying, well then, don’t you think it would have been smart to have a convo with your step-son @DonaldJTrumpJr before he liked a post about a false conspiracy theory which in turn put a target on my back

— Lauren Hogg (@lauren_hoggs) February 23, 2018

The First Lady hasn’t responded, and has been relatively silent on social media since the shooting. Indeed, she resorted to the GOP-beloved response of “thoughts and prayers” on the day of the massacre.

My heart is heavy over the school shooting in Florida. Keeping all affected in my thoughts & prayers.

— Melania Trump (@FLOTUS) February 14, 2018

Donald Trump Jr. reportedly liked tweets sharing the conspiracy theory suggesting that Lauren’s brother, David Hogg, was being coached to speak out against Donald Trump. Trump Jr.’s move appeared to be a passive endorsement of the one of many conspiracy theories floating around about the survivors that conservatives are embracing.

“The fact that Donald Trump Jr. liked that post is disgusting to me,” David Hogg told Anderson Cooper on Wednesday.

Just the president's son liking attacks on one of the Parkland survivors on the grounds that his father was in the FBI. pic.twitter.com/Dn4vrNBlFg

— Matthew Gertz (@MattGertz) February 20, 2018

It was this move that reportedly incited many internet trolls to bully the Hogg family though. The liked tweet “created a safe space for people all over the world to call me and my family horrific things that constantly re-victimizes us and our community,” Lauren Hogg explained on Twitter.

“I’m 14 I should never have had to deal with any of this and even though I thought it couldn’t get worse it has because of your family,” she tweeted.

While Melania Trump’s formal platform as First Lady has yet to officially be decided–during the campaign, she gave a speech addressing cyberbullying.

“Our culture has gotten too mean and too rough, especially to children and teenagers,” Melania Trump said in November 2016. “It is never OK when a 12 year old girl or boy is mocked, bullied, or attacked. It is terrible when that happens on the playground. And it is absolutely unacceptable when it is done by someone with no name hiding on the internet.”

According to a 2016 survey by the Cyberbullying Research Center, 33.8 percent of 5,700 middle and high school students between the ages of 12 and 17 said they’ve been bullied online in their lifetime. Nearly a quarter of those surveyed had received “mean of hurtful comments” in the last 30 days prior to when they took the survey.

I’m apologizing more — and saying “sorry” less

(Credit: Shutterstock)

During a recent visit, my Parisian friend was telling me the details of a family tragedy — a death, followed horribly by another one in unrelated circumstances. “I’m so sorry,” I said, as I leaned forward to touch his shoulder sympathetically. “Don’t say you’re sorry,” he said. “Why would you be sorry?” I fumbled for a reply. A day later, he described the comical tale of his afternoon and a near disastrous adventure involving lugging a large appliance up his hilly street. “I’m sorry you had such a rough time of it,” I told him, while chuckling at the image he’d described. “Don’t say that,” he insisted again. “I don’t understand why Americans always say they’re sorry.”

He was right. We do. What we as a culture don’t do, however, is apologize. Not often. Not well. Not sincerely. So going forward, I want to recalibrate my relationship with the word “sorry.”

I understand the uses of “sorry” as a means of expressing empathy. “Sorry” as a word to convey sadness and distress. As in, “I’m so sorry that happened to you.” “I’m so sorry to hear that news.” Even if the French frown on such overt expressions of dismay, I, with my unrestrained Yankee abundance of emotions, appreciate the compassionate intention of the sentiment. But my friend’s profound dismay for it got me thinking about how the phrase can be a convenient dodge. Saying “I’m sorry” describes how another person’s experience makes me feel. I feel sorry. I feel sad. I am saying that I understand what you went through, but I’m also conveying, whether you asked for it or not, my own eagerness to commiserate. Why presume that’s helpful, or wanted? Sometimes it takes a French person to tell you point blank that it is not.

I also know that, as a woman, I have a “sorry” locked and loaded for nearly every social occasion. I use it as a softening device, a rhetorical dryer sheet. Can’t chaperone a class trip? I’m so sorry, I have another obligation that day. Don’t like the price quoted on a job? I’m sorrrreeeee, that’s a little more than I can pay. In the course of a week, I routinely say I’m sorry to strangers for bumping into me on the subway and to line jumpers for cutting in front of me at the cafe. “I’m sorry,” I’ll tell them, “I think I was next,” knowing damn well the first four words of that sentence are an unnecessary smoothing of the way. I say I’m sorry for being interrupted and for having an opinion contrary to the one another person is expressing, however ridiculous the other person’s opinion may be. And I’m perfectly aware that I do this even less now than I did as a young woman, when I was more fearful of conflict and more eager to please. I’m also aware, still, of the consequences for a woman stating either a fact (Hello, I’m standing right here) or an opinion (Cilantro is delicious, haters) — she’s regarded as brittle, testy and difficult.

But when I hear my teenaged daughters preface their declaratory statements with that buffering word, I know I have to try to set a better example. Because in truth, I am not sorry about not going on that field trip, nor being overcharged for goods and services, nor that hip check on my morning commute. I don’t want my daughters to be, either.

What I’m sorry about, instead, is how inadequate I often am at expressing true remorse. Like a lot of people, I don’t have a great education in the field. I grew up in a home in which sincere atonement was rarely, if ever, offered. “I’m sorry” was inevitably followed by an “if you feel that way” or “but I was only . . . ” It was conditional and self-exonerating. It wasn’t until I began a relationship with someone in AA, a program that literally contains a blueprint for restitution in its bedrock 12 steps, that I learned the concept of true amends.

Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time observing the near constant spectacle of bad apology — the myriad ways in which public figures who’ve done despicable things downplay their actions, insist they were just misunderstood and then, with a shrug, vow to go off and work on themselves. Hey, I’ve done my own version of it myself for some of my worst misbehavior. I know, however, what a real apology looks like. It’s honest and it’s vulnerable. The formula isn’t rocket science: Say what you did wrong, apologize for doing it, say how you’re going to make it right — oh, and don’t do it again! That’s an “I’m sorry” worth stating.

The English language is often a blunt instrument for conveying complicated ideas. You notice that acutely when you talk to someone who isn’t a native speaker. It wasn’t until I said a word I routinely say several times a day to a Parisian that I realized both how insufficient — and how important —it can be. How I need to say sorry less. And apologize more.

The Trump administration goes to war — with itself — over the VA

(Credit: AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

David Shulkin, the secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, showed up to what he thought would be a routine Senate oversight hearing in January, only to discover it was an ambush.

David Shulkin, the secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, showed up to what he thought would be a routine Senate oversight hearing in January, only to discover it was an ambush.

Sen. Jerry Moran, R-Kan., was the sole holdout among members of the veterans affairs committee on a bill that would shape the future of the agency. The bipartisan bill had the support of 26 service groups representing millions of veterans. But Moran was pushing a rival piece of legislation, and it had the support of a White House aide who wields significant clout on veterans policy. Neither proposal could advance as long as there was any doubt about which President Donald Trump wanted to sign.

Moran blamed Shulkin for the impasse. “In every instance, you led me to believe that you and I were on the same page,” Moran said at the hearing. “Our inability to reach an agreement is in significant part related to your ability to speak out of both sides of your mouth: double talk.”

There were gasps in the hearing room. It was an astounding rebuke for a Trump appointee to receive from a Republican senator, especially for Shulkin, who was confirmed by the Senate unanimously.

Clearly ruffled, Shulkin hesitated before answering. “I think it is grossly unfair to make the characterizations you have made of me, and I’m disappointed that you would do that,” he said. “What I am trying to do is give you my best advice about how this works.”

Moran dug in. “I chose my words intentionally,” he said. “I think you tell me one thing and you tell others something else. And that’s incompatible with our ability to reach an agreement and to work together.” Moran then left the hearing for another appointment.

The exchange exposed tensions that had been brewing for months behind closed doors. A battle for the future of the VA has been raging between the White House and veterans groups, with Shulkin caught in the middle. The conflict erupted into national headlines this week as a result of a seemingly unrelated development: the release of a lacerating report on Shulkin that found “serious derelictions” in a taxpayer-funded European business trip in which he and his wife enjoyed free tickets to Wimbledon and more.

The underlying disagreement at the VA has a different flavor than the overhauls at a number of federal agencies. Unlike some Trump appointees, who took the reins of agencies with track records of opposing the very mission of the organization, Shulkin is a technocratic Obama holdover. He not only participated in the past administration, but defends the VA’s much-maligned health care system. He seeks to keep the organization at the center of veterans’ health care. (An adviser to Shulkin said the White House isn’t permitting him to do interviews.)

But others in the administration want a much more drastic change: They seek to privatize vets’ health care. From perches in Congress, the White House and the VA itself, they have battled Shulkin. In some instances, his own subordinates have openly defied him.

Multiple publications have explored the turmoil and conflict at the VA in the wake of the inspector general report. Yet a closer examination shows the roots of the fight stretch back to the presidential campaign and reveals how far the entropy of the Trump administration has spread. Much has been written on the “chaos presidency.” Every day seems to bring exposés of White House backstabbing and blood feuds. The fight over the VA shows not only that this problem afflicts federal agencies, too, but that friction and contradiction were inevitable: Trump appointed a VA secretary who wants to preserve the fundamental structure of government-provided health care; the president also installed a handful of senior aides who are committed to a dramatically different philosophy.

The blistering report may yet cost Shulkin his job. But the attention on his travel-related misbehavior is distracting from a much more significant issue: The administration’s infighting is imperiling a major legislative deal that could shape the future of the VA.

Taking better care of veterans was a constant refrain at Trump’s presidential campaign rallies. In the speech announcing his candidacy, he said, “We need a leader that can bring back our jobs, can bring back our manufacturing, can bring back our military, can take care of our vets. Our vets have been abandoned.” Ex-military people overwhelmingly supported him on Election Day and in office.

Trump’s original policy proposals on veterans health, unveiled in October 2015, largely consisted of tweaks to the current system. They called for increasing funding for mental health and helping vets find jobs; providing more women’s health services; modernizing infrastructure and setting up satellite clinics in rural areas.

The ideas drew derisive responses from the Koch brothers-backed group Concerned Veterans for America (CVA). Pete Hegseth, its then-CEO, called the proposal “painfully thin” and “unserious.”

Trump then took a sharp turn toward CVA’s positions after clinching the Republican nomination. In a July 2016 speech in Virginia Beach, he embraced a very different vision for the VA, emphasizing private-sector alternatives. “Veterans should be guaranteed the right to choose their doctor and clinics,” Trump said, “whether at a VA facility or at a private medical center.”

Trump’s new 10-point plan for veterans policy resembled the CVA’s priorities. In fact, six of the proposals drew directly on CVA ideas. Three of them aimed to make it easier to fire employees; a fourth advocated the creation of a reform commission; and two involved privatizing VA medical care.

Trump’s new direction, according to a campaign aide, was influenced by Jeff Miller, then the chairman of the House veterans committee. Miller, who retired from Congress in January 2017, was a close ally of CVA and a scathing critic of Obama’s VA.

Miller became one of the first congressmen to endorse Trump, in April 2016. He did so a few weeks after attending a meeting of the campaign’s national security advisers. (That meeting, and the photo Trump tweeted of it, would become famous because of the presence of George Papadopoulos, who is cooperating with investigators after pleading guilty to lying about Russian contacts. Miller is wearing the light gray jacket in the front right. Now a lobbyist with the law firm McDermott Will & Emery, he didn’t reply to requests for comment.) Miller became Trump’s point man on veterans policy, the campaign aide said.

Miller and CVA portrayed the VA as the embodiment of “bureaucratic ineptitude and appalling dysfunction.” They were able to cite an ample supply of embarrassing scandals.

The scandals may come as less of a surprise than the fact that the VA actually enjoys widespread support among veterans. Most who use its health care report a positive experience. For example, 92 percent of veterans in a poll conducted by the Veterans of Foreign Wars reported that they would rather improve the VA system than dismantle it. Independent assessments have found that VA health care outperforms comparable private facilities. “The politicization of health care in the VA is frankly really unfair,” said Nancy Schlichting, the retired CEO of the Henry Ford Health System, who chaired an independent commission to study the VA under the Obama administration. “Noise gets out there based on very specific instances, but this is a very large system. If any health system in this country had the scrutiny the VA has, they’d have stories too.”

One piece of extreme noise was a scandal in 2014, which strengthened Miller and CVA’s hand and created crucial momentum toward privatization. In an April 2014 hearing, Miller revealed that officials at the VA hospital in Phoenix were effectively fudging records to cover up long delays in providing medical care to patients. He alleged that 40 veterans died while waiting to be seen. A week later, CVA organized a protest in Phoenix of 150 veterans demanding answers.

Miller’s dramatic claims did not hold up. A comprehensive IG investigation would eventually find 28 delays that were clinically significant; and though six of those patients died, the IG did not conclude that the delays caused those deaths. Later still, an independent assessment found that long waits were not widespread: More than 90 percent of existing patients got appointments within two weeks of their initial request.

But such statistics were lost in the furor. “Nobody stood up and said, ‘Wait a minute, time out, are we destroying this national resource because a small group of people made a mistake?’” a former senior congressional staffer said. “Even those who considered themselves to be friends of the VA were silent. It was a surreal period. The way it grew tentacles has had consequences nobody would have predicted.”

In the heat of the scandal, Miller and CVA pushed for a new program called Choice. It would allow veterans who have to wait more than 30 days for a doctor’s appointment or live more than 40 miles from a VA facility to get private-sector care. The VA has bought some private medical care for decades, but Choice represented a significant expansion, and Democrats were wary that it would open the door to privatizing VA health care on a much broader scale.

Still, the Phoenix scandal had made it hard for the Democrats to resist. The Choice bill passed with bipartisan support and President Obama signed it into law in August 2014.

By 2016, then-candidate Trump was demanding further changes. “The VA scandals that have occurred on this administration’s watch are widespread and inexcusable,” he said in the Virginia Beach speech. “Veterans should be guaranteed the right to choose their doctor and clinics, whether at a VA facility or at a private medical center. We must extend this right to all veterans.”

Trump’s contacts with CVA and its allies deepened during the transition. He met Hegseth, who left CVA to become a Fox News commentator, in Trump Tower. Trump picked Darin Selnick for the “landing team” that would supervise the transition at the VA. Selnick had directed CVA’s policy task force, which in 2015 recommended splitting the VA’s payer and provider functions and spinning off the latter into a government nonprofit corporation. Such an operation, organized along the lines of Amtrak, would be able to receive federal funding but also raise other revenue.

Trump’s consideration of Hegseth and Miller to lead the VA ran into fierce resistance from veterans groups, powerful institutions whose clout is boosted by the emotional power that comes with members’ having risked their lives for their country. At a meeting with the Trump transition in December 2016, officials from the major veterans groups held a firm line against privatizing the VA and any secretary intent on it.

Trump finally settled on Shulkin, 58, who ran the VA health system under Obama. Shulkin is a former chief of private hospital systems and a doctor — an internist, he still occasionally treats patients at the VA — who comes across more as a medical geek than the chief of a massive organization.

Trump heaps praise on Shulkin in public appearances and meets with him regularly in private. He was one of the first cabinet secretaries Trump consulted about the impact of the government shutdown on Jan. 21. They met at Camp David in December and lunched at the White House on Feb. 8. “You’re doing a great job,” Trump told Shulkin at a Jan. 9 signing ceremony for an executive order on veterans mental health services, handing Shulkin the executive pen. “We appreciate you.”

Trump may like Shulkin. But that didn’t stop his administration from appointing officials who opposed his philosophy. One of them, Jake Leinenkugel, a Marine Corps veteran and retired Wisconsin brewery owner, became the White House’s eyes and ears inside the agency. He works in an office next to Shulkin’s, but his title is senior White House adviser. Leinenkugel, 65, said he came out of retirement to take the position because he was “excited about taking POTUS’s agenda and advancing it.” As he put it, “I’m here to help veterans.”

He and Shulkin got along fine for a few months. But then, in May 2017, the two men clashed, as Shulkin accused Leinenkugel of undermining him. Shulkin wanted to nominate the VA’s acting under secretary for health, Poonam Alaigh, to take the position permanently, according to two people familiar with his thinking. But, the VA secretary charged, Leinenkugel told the White House to drop Alaigh. Shulkin confronted Leinenkugel, who denied any sabotage, according to an email Leinenkugel subsequently wrote. Alaigh stepped down in October and the position remains unfilled.

Shulkin has even been at odds with his own press secretary, Curt Cashour, who came from Miller’s House committee staff. Last month, Shulkin assigned an official to send a letter to a veterans group that said the agency would update its motto, to be inclusive of servicewomen. (Adapted from Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address, the original reads, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan.” The new version would read: “To care for those who shall have borne the battle and their families and survivors.”)

Cashour told The Washington Post the motto wouldn’t change. A few days later, the secretary’s strategic plan went out using the updated, gender-neutral motto. Cashour then denied the change a second time, telling the Post that was “not VA’s position.” A new document with the Lincoln quote restored subsequently appeared on the VA’s website. Shulkin was stunned at being disobeyed by his own spokesman, two people briefed on the incident said. (Cashour denied defying the VA secretary. “The premise of your inquiry is false,” he told ProPublica. Cashour said Shulkin never approved the letter regarding the updated motto and authorized the restoration of the original one.)

Then there was Selnick, who became the administration’s most effective proponent for privatization. He joined the VA as a “senior advisor to the secretary.” Though he reported to Shulkin, he quickly began developing his own policy proposals and conducted his own dealings with lawmakers, according to people with knowledge of the situation. In mid-2017 Shulkin pushed him out — sort of.

Selnick left the VA offices and took up roost in the White House’s Domestic Policy Council. There he started hosting VA-related policy meetings without informing Shulkin, according to people briefed on the meetings. At one such meeting of the “Veterans Policy Coordinating Committee,” Selnick floated merging the Choice program with military’s Tricare insurance plan, according to documents from the meeting obtained by ProPublica.

Veterans groups were furious. At a Nov. 17 meeting, Selnick boasted that Trump wouldn’t sign anything without Selnick’s endorsement, according to a person present. Shulkin would later tell a confidant that moving Selnick out of the VA was his “biggest mistake” because he did even more damage from the White House. (Selnick did not reply to a request for comment. A White House spokesman said some VA officials were aware of the policy meetings that Selnick hosted. The spokesman said Selnick does not brief the president or the chief of staff.)

Selnick, 57, is a retired Air Force captain from California who worked in the VA under the George W. Bush administration. At CVA, he not only ran the policy task force, he testified before Congress and appeared on TV. In 2015, House Speaker John Boehner appointed Selnick to the Commission on Care, an independent body created by a Congressional act to study the VA and make recommendations.

Selnick impressed his fellow commissioners with his preparation but sometimes irked them with what they viewed as his assumption that he was in charge, people who worked with him on the commission said. Selnick often brought up his experience at the VA. But some commissioners scoffed behind his back because his position, in charge of faith-based initiatives, had little relevance to health care. Whatever his credentials, Selnick had audacious ambitions: He wanted to reconceive the VA’s fundamental approach to medical care.

Selnick wanted to open up the VA so any veteran could see any doctor, an approach that would transform its role into something resembling an insurance company, albeit one with no restrictions on providers. Other commissioners worried that would cost the government more, impose fees and deductibles on veterans and serve them worse. “He was probably the most vocal of all of the members,” said David Gorman, the retired executive director of Disabled American Veterans who also served on the commission, “in a good and a bad way.”

The bad part, in the view of Nancy Schlichting, the chairwoman, emerged when Selnick tried to “hijack” the commission. Selnick and a minority of commissioners secretly drafted their own proposal, which went further than CVA’s. (The group included executives of large health systems that stood to gain more patients.) They wrote that the “the current VA health care system is seriously broken” with “no efficient path to repair it.” They proposed closing facilities, letting all veterans choose private care, and transitioning the rest to private care over two decades.

The draft was written in a way that seemed to speak for the commission as a whole, with phrases like “the Commission recommends.” The commission staff suggested labeling it a “straw man report,” implying it was meant to provoke discussion. Still, veterans organizations were angry, and Schlichting had to publicly disavow the draft. “Darin Selnick has never run a health system in his life and doesn’t understand the complexity of it,” Schlichting told ProPublica.

For his part, Shulkin publicly staked out his vision in a March 17, 2016 article in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, he defended the VA’s quality of care and proposed reimagining the VA as an integrated system composed of its own core facilities, a network of vetted private-sector providers, and a third layer of private care for veterans in remote places. Shulkin also edited a book published last year trumpeting the VA’s successes, called “Best Care Everywhere.”

Almost four years after the Phoenix scandal, the emergency measure letting some veterans get care outside the VA is still limping along with temporary extensions, not to mention payment glitches and confusion about its rules. Key legislators grew tired of renewing emergency funding and wanted to find a long-term solution. In the House, negotiations broke down after Democrats boycotted a listening session featuring CVA. So last fall, focus turned to the Senate.

The crux of the debate was the extent to which the VA should rely on private care. The chairman and ranking member on the Senate veterans committee, respectively, Johnny Isakson of Georgia and Jon Tester of Montana, drafted a bill to consolidate all of the VA’s programs that pay for private care and let doctors and patients decide where veterans would get care. The VA would buy private care when that makes the most sense but would still coordinate all veterans care in an integrated, comprehensive way. The bill garnered the support of 26 veterans organizations and every committee member except Moran.

Moran represents the Koch brothers’ home state; employees of Koch Industries are the second-largest source of campaign contributions in his career, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics. With the support of CVA, Moran wanted to establish clear criteria making veterans eligible for private-sector care, like the 30 days/40 miles standard in the Choice program. It might sound like a subtle distinction, but it means the difference between keeping all veterans within the VA system versus ceding the direction of patient care to the private sector. When the committee rejected his amendment, Moran proposed his own bill and signed up Sen. John McCain as a co-sponsor.

Moran’s bill initially called for all veterans to be able to choose private care. When a McCain aide shared it with a lobbyist for the American Legion, the lobbyist was so enraged by what he viewed as a bid to undermine the VA that he torched a copy of the bill and sent the McCain aide a photo of the charred draft. (An American Legion spokesman declined to comment.) With the American Legion’s input, McCain’s and Moran’s staffs toned down the bill to the point that they got letters of support from the group, along with Amvets and CVA. But American Legion and Amvets were still working to get consensus on the Isakson-Tester bill.

Still, the Moran-McCain bill had a few key allies: Selnick and Leinenkugel. They had gained sway in part because of a White House vacuum. The president himself has been largely absent on veterans policy and there’s no senior point person. The portfolio has at times belonged to Kellyanne Conway, Jared Kushner and Omarosa Manigault, according to veterans groups and congressional officials. (A White House spokesman said those officials played a role in “veterans issues,” but not “veterans policy.” The latter, the spokesman said, is overseen by Selnick on the Domestic Policy Council.)

That has given Selnick and Leinenkugel wide latitude to shape White House positions on issues that don’t rise to Trump’s level. “Darin [Selnick] is pretty much in the ascendancy,” said Michael Blecker, the executive director of Swords to Plowshares, a San Francisco-based charity serving veterans.

As long as Moran had a competing claim to the Trump administration’s support, the Isakson-Tester bill was stuck. Republicans wouldn’t risk a floor vote on a bill the president might not sign. Shulkin supported the Isakson-Tester bill but he knew his rivals inside the White House were pushing for Moran’s proposal. So Shulkin hedged, awkwardly praising both bills. “We still don’t know which bill he wants,” Joe Chenelly, executive director of Amvets, said. “If the White House wants something different, then we need to know how to reconcile that.”

Amid the impasse, the Choice program was out of money again and needed an extension as part of the end-of-year spending deal. Tester vowed to make it the last one he’d agree to. He called on Shulkin to break the stalemate by publicly endorsing his and Isakson’s bill. “I would love to have the VA come out forcefully for this bill,” he said on the Senate floor in late December. “I think it would help get it passed.”

In a private meeting, Isakson and Tester chided Shulkin for withholding support for their bill, according to three people briefed on the meeting. Shulkin told them he was doing the best he could, but he had to fend off a competing agenda from the White House.

Unbeknown to Shulkin, there was already talk in the White House of easing him out. On Dec. 4, Leinenkugel wrote a memo, which ProPublica obtained, summarizing his disillusionment with Shulkin as well as with Shulkin’s deputy, Thomas Bowman, and chief of staff, Vivieca Wright Simpson. (“I was asked to tell the truth and I gave it,” said Leinenkugel of his memo; he declined to say who requested it.)

Leinenkugel accused Bowman of disloyalty and opposing the “dynamic new Choice options requested by POTUS agenda.” The memo recommended that Bowman be fired — and replaced by Leinenkugel himself. It also asserted that Wright Simpson “was proud to tell me she is a Democrat who completely trusts the secretary and it’s her job to protect him.” Leinenkugel accused her of delaying the placement of Trump’s political appointees. Leinenkugel recommended replacing her, too.

As for Shulkin, Leinenkugel’s memo advocated he be “put on notice to leave after major legislation and key POTUS VA initiatives [are] in place.”

After the clash between Moran and Shulkin at the January hearing, Isakson said the White House would provide feedback on his bill to help the committee chart a way forward. “The president basically is pushing to get a unanimous vote out of committee,” said Rick Weidman, the top lobbyist for Vietnam Veterans of America. “The only reason why we didn’t get it before was there is one mid-level guy on the Domestic Policy Council who threw a monkey wrench into it by confusing people about what the administration’s position is.” That person, Weidman said, is Selnick.

The White House’s feedback on the Isakson-Tester bill, a copy of which was obtained by ProPublica, was the closest the administration has come to a unified position on veterans health care. It incorporated input from the VA and the Office of Management and Budget. Selnick told veterans groups he wrote the memo, leaving some miffed that Selnick seemingly had the final word instead of Shulkin. (A White House spokesman said Selnick was not the only author.)

Selnick requested changes that might look like minor tweaks but would have dramatic policy consequences. “It’s these very small differences in details that the public would never notice that change the character of the thing entirely,” said Phillip Longman, whose 2007 book, “Best Care Anywhere,” argued that the VA works better than private health care. (The title of the book Shulkin edited, “Best Care Everywhere,” was a nod at Longman’s book.)

Most important, the White House wanted clear criteria that make veterans eligible for private care. That was the main feature of Moran’s bill and the sticking point in the negotiations. The administration also asked to preserve a piece of the Choice program by grandfathering in veterans living more than 40 miles away from a VA facility. CVA praised the White House for nudging the bill in Moran’s direction. “We applaud President Trump for taking a firm stand in favor of more health care choice for veterans at the VA,” the group’s director, Daniel Caldwell, said in a statement dated Jan. 24.

The White House feedback also called for removing provisions that would regulate providers, such as requiring them to meet quality standards and limiting opioid prescriptions. And the administration objected to provisions in the bill that would require it to fill critical vacancies at the VA and report back to Congress.

Selnick got what he asked for, but it still might not be enough. Isakson and Tester agreed to most of the changes. But in a White House meeting with veterans groups on Feb. 5, Selnick continued to insist on open choice, suggesting that’s what Trump wants. Selnick visited Moran’s staff, a person with knowledge of the meeting said, and Moran indicated he wouldn’t support the modified version of the Isakson-Tester bill. (A White House spokesman said Isakson and Tester did not accept all the changes and negotiations continue. He denied that Selnick pushed for open choice.) Moran’s spokesman didn’t answer emailed questions by press time.)

The tensions spilled out publicly again on Feb. 8, when the Washington Post reported that the White House wanted to oust Bowman, Shulkin’s deputy. The article said the purpose was to chastise Shulkin for “freewheeling” — working with senators who don’t share the administration’s position. Isakson’s spokeswoman called it a “shameful attempt” to derail the negotiations. Isakson resolved to move ahead without Moran, the spokeswoman said, but it’s not clear when the bill will get time on the Senate floor (the Senate focused on immigration this week and then will take a recess). Moran could still place a “hold” on the bill or round up other senators to oppose it.

Shulkin determined that Selnick and Leinenkugel had to go, according to four people familiar with the secretary’s thinking. But Shulkin doesn’t appear to have the authority to fire them since they work for the White House. Plus, the attacks from the right were already taking a toll on Shulkin’s standing. “If leaders at Trump’s VA don’t support REAL CHOICE — why won’t they resign?” former CVA chief Hegseth tweeted on Feb. 13, tagging Shulkin in the post.

Veterans advocates responded by defending Shulkin against attacks they viewed as originating with Selnick and Leinenkugel. “They thought they could coopt David,” said Weidman, the lobbyist for Vietnam Veterans of America. “When he couldn’t be coopted, they decided to go after his character.”

The biggest blow came on Feb. 14, when the VA’s Inspector General released its report on Shulkin’s trip to Europe in April 2017. It concluded that Shulkin improperly accepted Wimbledon tickets, misused a subordinate as a “personal travel concierge,” lied to reporters, and that his chief of staff doctored an email in such a way that would justify paying travel expenses for Shulkin’s wife.

Shulkin disputed the IG’s findings, but he again ran into trouble getting his message out from his own press office. A statement insisting he had “done nothing wrong” disappeared from the VA’s website, and Cashour replaced it with one saying “we look forward to reviewing the report and its recommendations in more detail before determining an appropriate response.” Cashour said the White House directed him to take down Shulkin’s statement and approved the new one.

Shulkin told Politico the IG report was spurred by internal opponents. “They are really killing me,” he said. By Feb. 16, his chief of staff had told colleagues Friday she would retire, USA Today reported.

The condemnation after the IG report was swift and widespread. House veterans committee member Mike Coffman, R-Colo., called on Shulkin to resign. Democrats, though generally sympathetic to Shulkin, couldn’t resist lumping the imbroglio in with other travel-expense tempests across Trump’s cabinet (involving Tom Price, Ryan Zinke, Scott Pruitt, and Steven Mnuchin). The chairs and ranking members of the House and Senate veterans committees said they were “disappointed” and want Shulkin to address the allegations, but acknowledged the politics at work and the stakes in a joint statement: “We need to continue progress we have made and not allow distractions to get in the way.”

The next day, Shulkin appeared before another routine oversight hearing, in this instance on the House side. He told the representatives he would reimburse the government for his wife’s travel and accept the IG’s recommendations. Shulkin thanked the chairman and ranking member for urging their colleagues not to let the scandal commandeer the hearing. “I do regret the decisions that have been made that have taken the focus off that important work,” he said.

Turning to the VA’s budget, Shulkin resumed his tightrope walk. He praised the VA’s services while acknowledging the need for some veterans to be treated outside the government’s system. By the time he left the hearing, two hours later, the Trump administration’s position on veterans health privatization remained a mystery.

House Intelligence Committee releases Schiff memo with redactions

(Credit: AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

The House Intelligence Committee released the Adam Schiff memo on Saturday after weeks of speculation on if and when the Democratic memo would be released—and with what controversial FBI redactions.

In early February, Donald Trump objected to Schiff releasing the memo, which caused a backlash. The 4-page memo released by Chairman David Nunes, R-Calif., alleged abuses by the Department of Justice and FBI, but according to the memo released on Saturday by Schiff, D-Calif., the move to rush and release the Nunes memo was “by design.”

“The Democratic response memo released today should put to rest any concerns that the American people might have as to the conduct of the FBI, the Justice Department and the FISC,” Schiff said in a statement on Saturday. The Democratic memo seeks to set the record straight on the FISA warrant application for former Trump campaign foreign policy advisor Carter Page.

“Our extensive review of the initial FISA application and three subsequent renewals failed to uncover any evidence of illegal, unethical, or unprofessional behavior by law enforcement and instead revealed that both the FBI and DOJ made extensive showings to justify all four requests,” Schiff wrote.

The Schiff memo states that the FISA application wasn’t used “to spy on Trump or his campaign.” Page, who reportedly had connections to the Russian government, “ended his formal affiliation with the campaign months before DOJ applied for a warrant.” The memo explains that the DOJ’s request for a warrant was based on “probable cause to believe Page was knowingly assisting clandestine Russian intelligence activities in the U.S.”

Some of the probable cause and evidence are redacted in the memo, but from the information available, Page allegedly had an “extensive record” of a redacted bit of information prior to joining the Trump campaign.

The memo states that the DOJ “provided additional information obtained through multiple independent sources that corroborated [Christopher] Steele’s reporting.” It’s also stated that the FBI’s concerns about Page “long predate the FBI’s receipt of Steele’s information.”

In the four-page Republican memo, it claimed “on October 21, 2016, DOJ and FBI sought and received a FISA probable court order” that authorized electronic surveillance of Page; it failed to address that Page was actually known to American counterintelligence officials as far back as 2013, according to The Wall Street Journal— which the Democratic memo corroborates.

The Schiff memo states that Steele’s reporting was properly disclosed and that the DOJ had properly disclosed Steele’s motives to “discredit” Trump’s campaign.

“Steele’s reporting did not reach the counterintelligence team investigating Russia at FBI headquarters until mid-September 2016, more than seven weeks after the FBI opened its investigation because the probe’s existence was so closely held within the FBI,” the memo states.

The struggle to release the rebuttal memo started when Trump claimed that the memo would have to be heavily redacted prior to publication.

“The Democrats sent a very political and long response memo which they knew, because of sources and methods (and more), would have to be heavily redacted, whereupon they would blame the White House for lack of transparency,” Trump tweeted. “Told them to re-do and send back in proper form!”

The memo is redacted but provides sufficient information to dispute claims from the Nunes memo.

“We are workers, not slaves”

Farmers march with a sign that reads "Remove farming from NAFTA" in Mexico City. (Credit: AP/Gustavo Martinez Contreras)

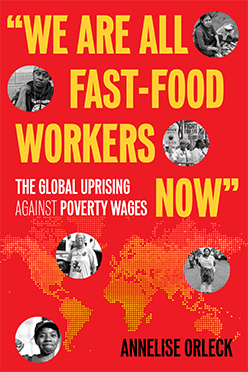

Excerpted from “We Are All Fast-Food Workers Now”: The Global Uprising Against Poverty Wages by Annelise Orleck (Beacon Press, 2018). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

In March 2015, tens of thousands of indigenous berry pickers walked out of the vast agribusiness fields of the San Quintin Valley in northern Mexico, launching the largest agricultural strike Mexico had seen in decades. Strikers carried signs that explain much about the world in which twenty-first-century workers operate. “Somos Trabajadores, No Esclavos. We Are Workers, Not Slaves.” When police cracked down violently, the Mexican newspaper La Jornada ran a cartoon of police beating strikers. “Haven’t thirty years of neoliberalism taught you anything?” the caption asked. The answer, in short, is: Yes. A lot.

As neoliberalism has spread, so have mass evictions, involuntary migrations, and many forms of unfree labor. Among those who grow grapes for the global wine market, pick berries, apples, and tomatoes for global grocery chains, are many who would rather have stayed on their own lands, growing their own food. In China alone, tens of millions of farmers were displaced by agribusiness, factories, and real estate development in the 2010s. Many became factory workers, in vast export zones, making products for export. In 2015, China unveiled a plan to move 250 million more farmers to cities by 2025. Meanwhile, food multinationals Cargill, Monsanto, and John Deere sell maize and soybeans grown in Brazil to Chinese consumers.

On Luzon, the largest island of the Philippines, farmers flooded the cities in the early 21st century as 2,000-year-old rice terraces fell into disrepair, says rice activist Vicky Carlos Garcia. Indigenous farmers on the southern island of Mindanao, forced off their lands at gunpoint to make way for banana and palm oil plantations, also have resettled in the vast shantytowns at the center of Manila—the infamous slums of Tondo. “Ask them why they are there,” says Garcia. “No one ever asks them. They just call them problems.”

In South Africa, more than two million farmers and farmworkers were evicted between 1994 and 2013. Cambodia, Taiwan, India, Japan, and Indonesia passed new laws in the 2010s opening their countries to foreign ownership and leasing, leaving tens of millions of farmers landless. After the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, an estimated two million Mexican farmers left their lands as corn prices plummeted and common lands were privatized.

Displaced farmers have become cheap labor for global industry and for agribusiness farms. Some become “guest workers”; many endure slave labor conditions. Undocumented migrants, laboring in the shadows, unprotected by labor laws, live in fear of deportation.

These migrants fill the mega-slums of Asia, Latin America, and Africa, living in cardboard shacks and tin huts along polluted rivers. They survive on food scavenged from fast-food Dumpsters, recooked and resold. They pick and resell garbage—waste from the global economy. Profiteers sell them water and access to illegal electric lines at exorbitant rates.

Increasingly fed up, farmers and farmworkers have been organizing globally. In 1993, they created La Via Campesina—“The Peasant’s Way.” By 2014, the group represented 164 farmers’ organizations in 72 countries and held conventions from Indonesia to Turkey. Its headquarters move every few years—from Brussels to Honduras to Zimbabwe. In 2015, Zimbabwean organic farmer Elizabeth Mpofu became “coordinator of the international peasant movement.” She is leading the fight against transnational corporations grabbing land and water, making people landless, poisoning the earth, destroying traditional farming practices. Via Campesina has helped to tie farmers, farmworkers, and landless and indigenous activists together around the world. “We are organized,” she said in 2016, “and we know what we want.”

In China, protests that the government calls “mass incidents” have skyrocketed, from a few thousand annually in the early 1990s to more than 180,000 per year in the 2010s. Most have been sparked by evictions and land expropriations. It’s the same story around the world. In 2012, Via Campesina began to push the United Nations to adopt an International Declaration of the Rights of Peasants to enshrine rights to land, clean water, and freedom from violence.

“In most regions where Via Campesina is present, the leaders are women,” Mpofu says. Women are “the backbone of agriculture” and have been at the forefront of farm protests. In South Africa in 2012, women grape pickers sparked the largest farmworker strike the country had seen in decades. In the Western Cape Winelands, thousands laid down their hoes and scythes to demand gender and race equity in pay, clean water, decent housing, and an end to sexual harassment and violence. By strike’s end, they had nearly doubled their wage to $10 daily. Most importantly, they overcame their fear and learned they could win gains if they fought.

When Oaxacan migrant berry pickers in the U.S. and Mexico began organizing en masse in the twenty-first century, women played a crucial role as well. One Mixteca woman, who had picked berries in the San Quintin Valley of northern Mexico since she was seven, explained that she was tired of being yelled at and made fun of for being indigenous, tired of being sexually harassed and abused. “That’s how it was for many years.” But the stirrings of militancy among other indigenous workers changed her. “We were asleep but now people have stood up and we will continue in this struggle for what is right so that our grandchildren will have a better future.”

In the mountain towns of Oaxaca, after NAFTA flooded Mexico with cheap industrial American corn, Triqui, Mixteco, and Zapoteco farmers could longer survive on their meager earnings from native corn and beans. Mexico stopped subsidizing domestically grown corn in 2008. Hunger raged as millions transitioned from subsistence farming to purchasing staple foods.

Tens of thousands of Mixtecos headed north. Arcenio Lopez walked through desert mountains under cover of night, paying “coyotes” (human smugglers) to guide him from Tijuana to California. He dodged snakes and bandits to join his father who had found work picking berries in Oxnard and lettuce in Watsonville. Now director of the Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP), Arcenio trains indigenous farmworkers to stand up for their rights.

The migrants MICOP serves often have spent years following crops from Mexico through California, Oregon, and Washington. They pick berries, apples, and grapes, pack kale, lettuce, and cilantro. At the end of the season they start again.

But the border has been increasingly militarized and it is more difficult to cross back and forth these days. Families have been separated. Some remain in California, Texas, or Arizona. Others work on the Mexican side — planting and picking tomatoes in Sinaloa, berries in San Quintin. They are the people behind the fresh-food revolution that has transformed the diets of affluent consumers worldwide.

Theirs, too, is a struggle for respect and against violence. In 2012, Mixteco and Triqui farmworkers in Oxnard brought a case to the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board against employers who had used Tasers to stop field-workers from unionizing. When he was fired for organizing, Mixteco migrant Bernardino Martinez sued in court, and a judge ordered his reinstatement. “Most workers are too scared to go to court,” Martinez says. “They are afraid they’ll be deported. I was scared too, but even more, I was mad. And I was tired. I had been doing this for seven years, and it never got better.”

For it to get better, indigenous field-workers in the U.S. and Mexico knew they would have to build coalitions that wielded economic power. When workers struck Washington State’s largest blueberry grower in 2013, they reached out to consumers and college students and organized a boycott of Sakuma berries. It quickly broadened into a boycott of Driscoll’s berries. To make that work, they knew, meant organizing globally. Driscoll’s employs migrants from Canada to Mexico, Egypt to Portugal, and exports berries to Europe, China, and Australia.

Transnational networking produced impressive results. In the spring of 2015, 50,000 berry pickers in Baja California walked out of the fields, threatening the immensely lucrative harvest. Like their South African counterparts, many of these workers were migrants, forced to flee their ancestral farmlands by falling produce prices and international trade agreements. Bernardino Martinez believes that it is time for migrant farmworkers to be offered a path to citizenship, in the U.S. and around the world. Giving migrant workers citizenship rights, he says, “is the least you can do. Remember, we feed you all.”

Prince on film: from humble MTV beginnings to camp masterpiece “Purple Rain”

(Credit: AP/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon)

With all due respect to “Dirty Mind,” “Purple Rain,” “Parade,” and “Sign O’ the Times,” “1999” remains the most widely imitated record of Prince’s career. It’s one of the earliest, and most complete, meldings of electronic textures and dancefloor-oriented, blood-and-sweat funk, and it should come as no surprise that a childhood 1999 fan like myself would eventually dive deep into rave culture. Playing ancestor-worship can be a tired exercise, and God knows dance music hasn’t exactly stood still for the past 20 years. But “1999” is every bit as important as the handful of other late ’70s/early ’80s records–Parliament’s “Flash Light,” Kraftwerk’s “Trans-Europe Express,” Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock,” Larry Levan’s remix of Instant Funk’s “I Got My Mind Made Up,” and New Order’s “Blue Monday”—that carved the path for the next 20 years of house and techno. As the most down to earth, immediately accessible, and song-savviest of those records, it’s hardly surprising that “1999” had (and has) the broadest appeal—three million copies sold within its first two years of release, four million total in the U.S.

Given how densely electronic and dance-oriented “1999” is, there’s something ironic about it having turned Prince into a rock star. That had less to do with the album, though, than with MTV. Looking at Prince’s early videos, it’s amazing how ungainly he is. The “I Wanna Be Your Lover” clip is straightforward enough—multiple medium shots and close-ups of Prince playing all the instruments and singing—and his 1981 appearance on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” finds him and his band exuding a frenzied, bug-eyed energy. But the “Dirty Mind” clip—Prince and group performing onstage, wildly costumed, in front of a typically mixed audience of black funkateers and white new wavers—is jarring to look at today for anyone who grew up watching Prince execute some of the most intricate choreography in rock. His dancing is extremely sloppy; he flounces around, full of a nervous energy that’s appealing but also a little unsteady. This improves in the “Controversy” video, and by the “1999” video, with its stylish camera angles and priceless reaction shots (Prince’s mugging after the screen-whitening flashpots that accompany the line “We could all die any day” demonstrate him at his most openly goofy), he had shed some of that on-camera mania.

In the anthology “O.K. You Mugs: Writers on Movie Actors,” art critic Dave Hickey describes a television appearance by Robert Mitchum in which Mitchum explains the difference between stage and movie acting:

When you’re acting in a film… everything will be moving. There will be this hurricane of pictures swirling around you. The projector will be rolling, the camera will be panning, the angle of the shots will be changing, and the distance of the shots will be changing, and all these things have their own tempo, so you have to have a tempo, too. If you sit or stand or talk the way you do at home, you look silly on the screen, incoherent. On screen, you have to be purposive. You have to be moving or not moving. One or the other. So a lot of times, in a complicated scene, the best thing to do is stand absolutely still, not moving a muscle. This would look very strange if you did it at the grocery store, but it looks okay on screen because the camera and the shots are moving around you. Then, when you do move, even to pick up a teacup, you have to move at a speed. Everything you do has to have pace, and if you’re the lead in a picture, you want to have the pace, to set the pace, so all the other tempos accommodate themselves to yours.

To watch the video for “Little Red Corvette” after seeing the earlier clips is to see Prince having learned Mitchum’s lesson. Shot on film, not videotape, “Little Red Corvette” finds Prince rock-still behind the microphone while his hands move in slow, dramatic arcs, at a speed. The music gears up, and Prince gears up with it; it backs down, and he backs down. A deaf person could figure out what he’s singing about. Of course, so could a chimpanzee; Prince is always singing about sex, more or less. But like the song itself, the video is more playful suggestion than horny-toad come-on, pocked with cheetah-quick flashes of aggression when the song calls for them. During the guitar solo, Prince executes a quick, breathtaking series of dance steps that seem to harness all the energy he expended so carelessly in the “Dirty Mind” video. Then he gets back behind the mic to sing the bridge. His eyes don’t dart around anymore; he’s in command. And he’s teasing us; there are glimpses of this in the “Controversy” and “1999” videos, but nothing as sustained as the 30 seconds in which his lips curl into a sneer, then a moue, then an outrageously lubricious leer before the final chorus revs back in. In that short space, Prince completely sells the image he’d spent five albums propagating—to the viewer, and just as importantly to himself. So of course he made the semi-autobiographical feature film “Purple Rain” next. After a demonstration of self-belief that overpowering, what else could he do?

Reducing red tape for traveling nurses

Lauren Bond, a traveling nurse, has held licenses in five states and Washington, D.C. She maintains a detailed spreadsheet to keep track of license fees, expiration dates and the different courses each state requires.

The 27-year-old got into travel nursing because she wanted to work and live in other states before settling down. She said she wished more states accepted the multistate license, which minimizes the hassles nurses face when they want to practice across state lines.

“It would make things a lot easier — one license for the country and you are good to go,” said Bond, who recently started a job in California, which does not recognize the multistate license.

The license, known as the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC), was launched in 2000 to address nursing shortages and enable more nurses to practice telehealth. Under the agreement, registered nurses licensed in a participating state can practice in other NLC states without needing a separate license. They must still abide by the laws that govern nursing wherever their patients are located.

About half of the states joined the original compact, which was modeled on the portability of a driver’s license. Some states that declined to sign on cited a major flaw: The agreement didn’t require nurses to undergo federal fingerprint criminal background checks.

Last month, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing launched a new version of the NLC that requires those checks. Twenty-nine states have passed legislation to join the new agreement.

Jim Puente, who oversees the compact for the council, said he expects even more states to sign the agreement now that criminal background checks are required. He noted that nine states have legislation pending to join.

Among states participating in the new nurse licensing compact are Iowa, Kentucky, Tennessee, Delaware, Idaho and Arizona.

California does not plan to join the new compact, largely because of concern about maintaining state training and quality standards. The state, like many others, already requires nurses to undergo background checks. Washington, Oregon and Nevada are among the other states that do not accept the multistate license.

Proponents of the nurse licensing agreement — both the old and new versions — argue that it helps fill jobs in places where there aren’t enough nurses and enables nurses to respond quickly to natural disasters across state lines.

“The nurse shortage tends to wax and wane regionally, so being able to move nurses where the needs are is really, really important,” said Marcia Faller, chief clinical officer at AMN Healthcare, a San Diego-based medical staffing company that employs Bond. The multistate license “really helps with that mobility … to deliver care to patients across state lines.”

Similar cross-state agreements exist for physicians, psychologists, emergency medical technicians and physical therapists.

In some states, the multistate nursing license is helpful because it streamlines the process for nurses doing case management or telehealth, said Sandra Evans, executive director of the Idaho Board of Nursing. Getting nurses to work in the rural areas of Idaho is a challenge, and hospitals often rely on telemedicine in places where the closest health care facility might be in Montana, she said.

Before Idaho joined the original NLC in 2001, nurses doing telehealth or case management needed numerous licenses to work across state lines, but now they “can travel virtually — electronically or telephonically — to help their clients,” she said.

Joey Ridenour, executive director of the Arizona State Board of Nursing, said one of the biggest advantages of the compact for her state is that it allows authorities to share information and collaborate with other states to investigate and discipline problem nurses. “We are able to take action faster,” she said.

Opponents of the compact argue that states have different standards, course requirements and guidelines and that nurses licensed in one state may lack the necessary knowledge or experience to practice in another one.

“The ability to control the standards of training and quality are of some concern to us,” said Linda McDonald, president of United Nurses and Allied Professionals union in Rhode Island, which participated in the original NLC but hasn’t signed on to the new one. “We want them trained in Rhode Island. We want them licensed in Rhode Island.”

Nurses in California have similar concerns. “We really want to make sure that nurses who are entering our state and taking care of our patients are competent and qualified,” said Catherine Kennedy, a Sacramento-area nurse who is secretary of the California Nurses Association. Some traveling nurses haven’t been, she added.

Kennedy said California does not have difficulty recruiting nurses, even without the compact, because of the state’s relatively high salaries and strict nurse-to-patient ratios in hospitals.

Research has shown that California’s minimum nurse staffing requirements, which were the first in the nation, can reduce workloads and burnout, improve the quality of care and make it easier for hospitals to retain their nurses.

Massachusetts, which has never participated in the nurse licensing compact, requires nurses licensed there to take courses on treating victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, said Judith Pare, director of the division of nurses for the Massachusetts Nurses Association. If the state allowed out-of-state nurses to practice in Massachusetts without getting a license there, they wouldn’t necessarily have that training, she noted.

Bond, the traveling nurse, said additional courses don’t make her more qualified to do her job. “Across the board, wherever you go to nursing school, everybody comes out with a similar experience,” said Bond, who works at UCLA Medical Center in Santa Monica. “Then most of the training you are going to do is on the job.”

Jenn Stormes works as a nurse and formally cares for her 18-year-old son, who has a severe seizure disorder and developmental disabilities. Stormes is licensed in Colorado, which participates in the multistate compact.

She has been able to use that license in some states. But she has also had to get several individual licenses so she can continue serving as her son’s nurse in other states where the family travels for medical care. Stormes estimated she has spent about $2,000 on licenses.

“It took me over a year to get all these licenses,” she said. “I had to prove to every state the same education, the same experience, the same fingerprints. I think it is a duplication of efforts and is a waste of everybody’s time and money.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

February 23, 2018

Anna Deavere Smith on “Notes from the Field”: “I see this as a mating call”

Anna Deavere Smith in "Notes from the Field" (Credit: Courtesy of HBO)

Art mirrors headline news too often these days.

Take the nine days preceding the HBO premiere of Anna Deavere Smith’s “Notes from the Field,” for instance. They’ve been dominated by passionate debates about the fundamental right of children to be safe in their classrooms, inspired by the massacre in Parkland, Florida, that killed 17 people, most of them high schoolers.

Out of this terrible tragedy a student-led movement has been born to hold politicians accountable for their dedication to corporate values of the safety of their citizens, reopening the too-old debate about tighter gun regulations. It heated up considerably after the right wing preposterously suggested arming teachers as a viable solution.