Kristopher Jansma's Blog, page 15

June 18, 2012

Shadow of a Doubt: Franz Kafka and TV’s ‘The Killing’

How far would you go to learn the truth? In AMC’s detective drama, The Killing, “the truth” is the identity of 15-year-old Rosie Larsen’s killer in a perpetually-overcast Seattle. Would you risk losing your teenaged son, like Detective Sarah Linden? Ditch your fiancé? Would you work fifty hours straight, like her partner, Detective Stephen Holder? Endanger your sobriety by stepping into the den of your old meth dealer? Would you wrench your family even further apart, like Rosie’s father, Stan Larsen? Would you fight City Hall? Would you give up your badge and your gun?

Would you watch 13 hours of television? 26? 39?

This is, essentially, the question asked of us by The Killing, which just ended its controversial second season. The show began as one of the most critically acclaimed new shows of 2011, nominated for three Critic’s Choice awards and six Emmys. Tim Goodman at The Hollywood Reporter declared it “excellent, absorbing and addictive. When each episode ends, you long for the next – a hallmark of great dramas.” But a few months later, that same reviewer was singing a different tune. “Did The Killing Just Kill Itself?” his review of the first season finale asked.

June 14, 2012

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Everything is Illuminated — The New York Antiquarian Book Fair

Signed First ed. of The Catcher in the Rye - $186,000

Recently I dropped by the Armory on 67th and Park Avenue in Manhattan to see the 52nd Annual New York Antiquarian Book Fair and some of the rarest books on Earth. The fair brings booksellers from around the globe together with wealthy collectors and those, like me, who just want to breathe in the smell of hundred-year-old paper.

Actually I was sniffing around for something else. This was the same week that the Department of Justice’s suit against book publishers was announced and apocalyptic sentiments seemed to be in every newspaper, blog, and morning show. The enormous, austere Armory space on the Upper East Side, “one of the largest unobstructed spaces of its kind in New York,” seemed like a good place to get a bit of perspective. At the very least I thought I might hide amidst the most valuable books I could find.

[Read the rest here at Electric Literature's blog, The Outlet]

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Everything is Illuminated — The New York Antiquarian Book Fair

Signed First ed. of The Catcher in the Rye - $186,000

Recently I dropped by the Armory on 67th and Park Avenue in Manhattan to see the 52nd Annual New York Antiquarian Book Fair and some of the rarest books on Earth. The fair brings booksellers from around the globe together with wealthy collectors and those, like me, who just want to breathe in the smell of hundred-year-old paper.

Actually I was sniffing around for something else. This was the same week that the Department of Justice’s suit against book publishers was announced and apocalyptic sentiments seemed to be in every newspaper, blog, and morning show. The enormous, austere Armory space on the Upper East Side, “one of the largest unobstructed spaces of its kind in New York,” seemed like a good place to get a bit of perspective. At the very least I thought I might hide amidst the most valuable books I could find.

[Read the rest here at Electric Literature's blog, The Outlet]

June 8, 2012

True Stories: My Honesty Problem

Many friends of mine seem to be doing very difficult things right now. These friends, they are running marathons and joining Weight Watchers and going to business school and they are reading all of Infinite Jest. Recently I’ve decided I’d like to do something very difficult as well. Every week I’m going to write a true story and put it up here, online. Now, this may not seem like it would be very difficult. This may sound, in fact, like “starting a blog,” which millions of people do on a daily basis. But for me, writing truthfully each week will be like running a thousand miles. Let me explain.

Recently, I wrote a book review discussing how, as a fiction writer, I admire others’ ability to lie because I have always been terrible at lying to people. Except of course, when I’m writing. I love to make things up. I love inhabiting a good unreliable narrator. I love writing fiction that feels so real that you begin to forget it never really happened. I love creating characters that you get to know so well that you might find yourself thinking about calling them up on a Friday night to see if they want to hang out. But the flip-side of this is also true. As much as I love telling lies on the page, I find it nearly impossible to be totally truthful.

When I hold myself to the truth on the page, it always winds up looking, frankly, made-up – and I worry no one will buy it. I itch to embellish and tweak. I long to obscure things, even just a little bit. Writing the truth is a risky game – I think perhaps far riskier than telling lies.

But here’s a true story. I went to elementary school in a lady’s house. That’s true. It was called the Crighton School and it was in Old Bridge, New Jersey. You can look it up, if you want – though it has been closed now for years. It had only about 60 students, total, in grades K-6. We all had to wear uniforms: gray slacks, or skirts for the girls and white button-down shirts. In the winter, we wore red sweaters or yellow sweatshirts with a circular “Crighton School” emblem sewn on. Our Principal, Mrs. Kurtz was a strict woman who had once raised three sons in that stone-walled house. After they’d grown up, she’d moved into a small corner of the original home and transformed the rest into a beautiful three-room schoolhouse. There was a waterfall in the central stairwell of the school, and enormous picture windows, through which you could see the Edenic forest outside. We were, officially, “Gifted and Talented” children, safe behind Crighton School’s defensive walls.

I never knew who, or what, “Crighton” was. If this were fiction, I would invent some venerable forefather, whose portrait hung on the wall in the foyer. More likely Mrs. Kurtz made the name up, thinking it sounded austere. I’m only one paragraph in and I’m also itching to change all these names. After all, I’m Facebook friends with probably a dozen former Crighton Schoolers – and for all I know, Mrs. Kurtz is still out there somewhere. When people scrutinize my fiction, it only has to hold up against itself, and whatever empirical facts happen to come up. But non-fiction has to stand against the memories of everyone else involved. People who might remember things differently. People who may not want to be dragged into it, quite frankly.

But there are some things I remember very clearly. For instance, every day we would have lunch and then recess and then come back in for “Journal Time”. We were each given a black-and-white marble notebook in which to write daily about what we were doing and learning. From the start, this seemed extremely dull to me. I still have all of these old journals, and my early entries read like this: “Today we went outside. All the chickens are really big now. Amy said that she would play chess with me before school but Gregory was playing so we couldn’t.” Not exactly a thrilling narrative.

Which is why I soon got the idea to use Journal Time to record all the make-believe games I played with my friends during recess. My friend Susan and I had invented a fantasy kingdom where each day we rescued cute orange creatures named “Spots” from larger, blue, scary creatures called “Spikes”. The twist was that the Spots were really just baby Spikes, and needed to be inoculated to prevent them from growing up and turning evil. In this fantasy I was no longer a short boy with thick bifocals and an itchy school uniform; I could shoot fireballs from my palms and fly with rocket-propulsion through the sky. Susan could freeze anything on the spot and shoot arrows with icicle tips. It was, needless to say, a hell of a lot more interesting to write about than the things I was doing in real life, like learning the French alphabet or memorizing state capitals. Soon, several other friends joined our game and we eventually had a whole Avengers-type squad, embarking on complex rescue missions around the schoolyard. Over several years, these episodes evolved into epic, intertwined sagas, complete with illustrations of the Spike’s body armor, maps of the caves beneath the King’s palace, and diagrams of every detail of our powers. My friends and I would pore over these journals for hours and hours, examining this fantasy from every angle – trying to make it real.

I’m not sure how the next part happened exactly. That’s the trouble with true stories. Somehow my 4th grade teacher, Mrs. Hak, must have read my journal. I don’t remember being upset by this, or thinking that they were meant to be somehow private. I don’t know that I had much of a concept of “private” at that age. Either way, she called me up to let me know that Journal Time was for reflecting on one’s thoughts and ideas, and writing about what we’d really done that day. I tried to explain that these were real games of make-believe, but Mrs. Hak, who had always been very kind to me and our classmates, told me that I should give her way a chance. Maybe I would like writing about real things, if I tried it.

I was not interested. I pointedly refused to write in my journal, each day during Journal Time. It pained me to stand up against my favorite teacher this way. I’d known her since Kindergarten, at another school. There she’d been the more familiar “Carol” and I’d had to learn to call her “Mrs. Hak” when she came to teach at the Crighton School just after I enrolled. She liked to tease us by saying that she’d whip us with a wet noodle if we did not mind our P’s and Q’s. To me, now as an adult, that sounds a bit scary – but at the time I remember finding it hysterical. I liked her, and I liked that she was tough. Over the summer, she had gotten her hip replaced and was still getting around on crutches. So I’m sure I would have folded my protest in a couple of days-- except when all my friends noticed, they wanted in too. One boy, Michael, got particularly excited and encouraged everyone in the class to not write during Journal Time, and to sit there and stare angrily at our teacher.

When Mrs. Hak asked us why we were all refusing to write in our journals, Michael leapt up onto his chair and began yelling, “WE’RE ON STRIKE!” He kept yelling this, even as he was marched off to Mrs. Kurtz’s office.

Clearly, things had gotten out of hand. Michael not only co-opted my whole rebellion, but he told Mrs. Hak that I was the one who’d started it. The next day I was summoned to the Principal’s Office for the first time in my life. Terrified and disheartened, I was more than ready to give up the fight, just to avoid being punished. I’d heard horrible stories of what could happen in Mrs. Kurtz’s office from Michael, who was frequently sent to see her in that small part of the school that she lived in. That Michael was most often sent there for lying and making things up, never occurred to me then.

Strict Mrs. Kurtz echoed Mrs. Hak, “The purpose of Journal Time is to have you write about the real world. Make believe is perfectly fine, but there is a time and a place for it.”

I’m positive that I’d have sworn to never write another word of fiction again, merely to get out of that office alive. But then Mrs. Kurtz took out a box of new journals with red, plastic covers and golden ring binding.

“In the future, Journal Time will be extended by five minutes. After recess you will first write in your journals about real things. Then, afterwards, you can have five minutes to write anything you want in your new red notebooks.”

I returned to Mrs. Hak’s classroom in glorious triumph. For the rest of that year, my friends and I all dutifully scribbled in our journals each day about our boring old real lives, and then were rewarded with this special, wonderful Free Time to write in our red notebooks about whatever we wanted. In the war against adults and reality, I believed I’d won a major battle. I was hero, and not just a make-believe one this time.

But by the following year we’d gone back to plain old Journal Time again. I don’t remember being upset about it. I’m not sure when exactly we outgrew the red journals. Steadily, the fourth grade just took the wind out of us. Mrs. Hak left the school a few months after The Strike. “You’d better all mind your P’s and Q’s,” she told us, on her last day. “Or I’ll whip you with a wet noodle.”

We’d hear from our parents that one of her kidneys had developed an infection from the surgery and she had to get a transplant. While they were working on that, she was diagnosed with lung cancer – she’d been an avid smoker, though I don’t know if I knew that then. All year long we had a string of terrible substitutes, whose incompetence showed badly. They would teach us for a week or a month and then move on. Often times the new teacher would simply do the same lesson plans we’d done with the previous teacher. There was a tacit bargain amongst us, not to tell them we’d learned this all already, and we felt we were getting away with something brilliant. But it got boring. Watching our substitutes go over things again and again began to foster fresh doubts in my mind about the infallibility of grown-ups. Because they were never around long, they didn’t try hard to keep us in line. Soon we could get away with almost anything – so the privilege of writing make believe didn’t seem like such a huge deal.

We heard that Mrs. Hak had beaten her lung cancer, and quit smoking, and was doing fine with her new kidney. We all told stories about her to the kids in the lower grades. She was like The Terminator, or Robocop – she survived everything they threw at her. And I hoped and hoped she would return, so I could show her my black-and-white journal, filled with true stories and my red one, bursting with fiction. But then one day we were told that she had passed away. After beating cancer, surviving a kidney transplant and a hip replacement, she’d gone and had a heart attack. This was not how the story was supposed to go.

Other stories, too, kept going the wrong way. My best friend Ted’s parents got divorced that same year. I spent three days a week after school at his house and loved both his parents. I’d never even heard of divorce before, but my parents explained it to me and assured me it would never happen to them. The next day, I told Ted how sorry I was – and that it was all going to be OK, just like my parents had promised. He had no idea what I was talking about. His parents hadn’t told him yet. He thought I was making it up and I wished that I was.

He had to move out of his house, with its huge yard where we had built forts and conquered countless enemies. Then he left our school at the end of that year.

That was the year I got a bad ear infection and my eardrum burst in the middle of class, and mucus seeped out in front of everyone. That was the year that Winston threw a desk at one of our teachers. That was the year they tried to make us learn to write in script, and I hated it, because I could write much faster in print. All my familiar letters were now reinvented? The Qs looked like 2s – it was absurd. I refused to learn script and, despite hours of my parents making me practice at home, I got my first C+ ever in Penmanship that year. I still cannot write anything in script aside from my name.

That was the year there was a new girl – Danielle. She was the only black girl in the class. The rest of us always blamed her for stealing pencils from our desks. I don’t think I had any concept that this might have been racism at the time. What I do remember that she played Rosa Parks in the school play at the end of the year – a musical revue of the 20th century – and I got the part of the bus driver who forbid her to sit in the front of the bus. I had a little blue conductor’s hat, which dwarfed my tiny head.

“Go – to - the - back of the - bus” I bellowed, in as deep a voice as a nine-year-old was capable of, “You - can’t - sit up here with - us.”

People now recoil in horror when I tell that true story. They find it impossible to believe that any teacher would put either of us in that position. But it happened – and at the time I don’t remember thinking it was horrible at all. I was just excited about my solo. It’s only now that I can look back and wonder how she felt about all of it. It’s only now I wish I could rewrite it, from inside her head.

See, now if this was fiction, I would lie again right now. Not to cover up something shameful, but to keep things simple. I’d combine that first girl with another girl from our class who everyone always teased her for being obsessed with the Ninja Turtles. This second girl went around telling everyone she wanted to marry Raphael, which was bad enough because Ninja Turtles weren’t cool anymore, but then one day, this girl made the mistake of inviting a bunch of us over to her house for her birthday. I didn’t go for some reason, but afterwards everyone came back talking about how she didn’t even have a bed – that she slept on a mattress on the floor. That they had way more cats than normal people ought to have. That her mother had took them to the beach and then forgotten them there. Kids’ parents had said her mom had been drunk. I just remember noticing, always, afterwards that her sweaters were always dirty and her sweatshirts had holes in the wrists. Now suddenly I’m beginning to think that there were actually three girls, not two.

I never knew what happened to any of these girls – I don’t think any of them came back for fifth grade and everyone eventually forgot about them. There were new teachers, new school plays, new journals for a new year. I suppose I forgot the girls too, but I carried with me the distinct impression, for the first time, that there were problems out there that I didn’t have. That I was really lucky. That probably the true things I had managed to scribble into my journal were likely a lot less real than the things those three girls had been scribbling in theirs. If I could be any age again, I’d go back to the fourth grade. That was the year everything changed and somehow, despite all of these things, I remember it as one of the happiest years of my life.

Fourth grade was the year I wrote my very first book. It was an art project, and I had to illustrate, and bind it all by myself. It was 22 pages long - fiction, naturally – with a bright orange cover, and titled “The Pencil Thief”. I wrote it entirely in print, with all my Ps and Qs minded. In the book, Ted and I hid out in our school late at night and laid in wait to see who was stealing all the pencils from our desks. It turned out it was a girl who looked a lot like Danielle, but I disguised her by giving her a super-villain sort of costume: a ninja turtle-style mask and a big pointy-pencil hat. My friend and I chased her through a mystical portal, which led us into a magical world where everything was made of pencils. We captured her and there, the girl confessed that she did not like stealing pencils, but that she was the prisoner of her father, the evil Pencil King, who demanded that she go out into our world and steal our pencils, so that he could build himself an ever-larger palace. [image error]

So my friend and I teamed up with the Pencil Thief and thwarted the evil Pencil King. I’m pretty sure that at the end we returned all the stolen pencils to their rightful owners. What I definitely remember is that at the very end, the Pencil Thief was set free and everyone was happy.

In my story, I could do that.

May 26, 2012

Sideways Review: How To Fool Ourselves

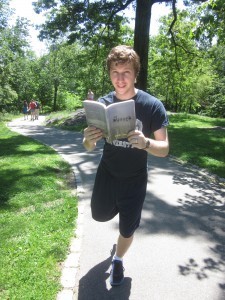

Photo by Leah MillerHunger Mountain, the literary journal for Vermont College of Fine Arts, has just posted my review of The Runner by writer David Samuels, a biography of con artist James Hogue, who successfully lied his way into Princeton University's class of 1993. How did a bicycle thief from Kansas gain entry to one of the most exclusive institutions in America? By using a little thing we like to call fiction, my friends...

"Hogue applied to Princeton University’s Class of 1992 with a personal essay describing his idyllic life as a Mexican-American sheepherder in California. He spoke of reading Whitman, Plato, and Kerouac in a moonlit canyon known as Little Purgatory. He said his mother was an artist residing in Switzerland and that his father was deceased. When Fred Hargadon, then head of Princeton Admissions, was asked to describe his ideal candidate for Princeton, he replied simply, 'Huckleberry Finn.' Hargadon wanted a fictional character, and Hogue made sure he got one. Hogue was admitted and granted a $12,730 track scholarship. Only everything he’d written was pure fiction, including his nom de application—Alexi Indris-Santana."

Check out the full story at Hunger Mountain's Sideways Reviews - http://www.hungermtn.org/sideways-review-how-to-fool-ourselves/ for more on Hogue, a few lies I've told (or tried to tell) in my day, and what all this can teach us about lying and writing fiction.

April 30, 2012

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Girls Gone Oscar Wilde

Spring! When a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of g-string bikinis, Pauly D branded bronzer, and doing lime Jello shots on booze cruises. From Cabo to Cancun, those who look good in swimsuits are celebrating that magical time of year when they can abandon their textbooks and fly south for sun and surf.

Which is why I decided to head in the opposite direction to spend Spring Break in Paris, where wearing sensible layers in March is recommended and “pasty” is a hue in high-demand. For those who look forward to vacations as “time to read something really fun” and who prefer downing snails at Brasserie Lipp to tequila shots at Señor Frog’s, it is tough to beat the City of Lights. True, the girls are a bit less likely to randomly remove their tops, but who needs that when you’ve got the Venus di Milo? Yes, the Moulin Rouge has become an overpriced tourist trap and the pink inn where Van Gogh once bedded prostitutes now serves bad soup. But things can still get a little raucous when you’re running the same wine-soaked streets that Hemingway and Fitzgerald stumbled down not so very long ago.

April 10, 2012

Finishing the Hat: Elmore Leonard, Raylan, and Justified

[image error]

Timothy Olyphant as US Deputy Marshall Raylan Givens

In the opening scene of FX’s hit series Justified, Deputy US Marshal Raylan Givens, played with no small amount of charm by Timothy Olyphant, wears a full white suit and a white cowboy hat as he strides between Miami sunbathers and sits down across the table from gun-runner Tommy Bucks. Leaning coolly back in his chair, Givens reminds Bucks he’s been given 24 hours to leave Miami. Time is up in two minutes. Bucks looks around wistfully. “I’ve been coming here ever since I was a kid. […] And to tell you the truth I love it here. I really do. I loved it then and I love it now. So I’m not gonna leave.” Bucks goes for his gun. Faster, cooler, and steadier, Givens puts three in his chest before Bucks can even blink.

Following this dust-up, Givens himself is exiled from Miami, forced by the Marshal’s Service to return to his own childhood home in Harlan County, Kentucky, where he is eternally weary of, and wise to, the peculiar characters he’d been hoping to escape. Whether it is his ex-wife Winona, his father Arlo, or his former coal mining partner, the devilish Boyd Crowder, Raylan can hardly tip his hat without running into his past along the “lonely road” of the show’s theme song.

Both the character of Raylan and the world of Harlan come from the pages of master crime-writer Elmore Leonard, who created Givens in two novels from the mid-90s, Pronto and Riding the Rap. The Wild West duel in Miami between Givens and Bucks comes straight out of the final pages of Pronto, though it wasn’t until 2001 when Leonard wrote the story “Fire in the Hole” where the killing of Bucks is given as the reason for Raylan being sent back to Kentucky. Perhaps it is a testament to Leonard’s interest in breaking new ground that he originally released the story as an e-book novella, well before e-readers were common, and despite the fact that, as he put it, “I won’t be able to read it - at least not in my home - since I don’t own a computer.”

Now Elmore Leonard is breaking a new kind of ground. Raylan Givens is hardly the first literary character to leave the stories where he was born for the bright lights of film or television, but he may be the first to ever return home to print again.

In his new novel, Raylan, published earlier this year by William Morrow, Elmore Leonard writes his first Raylan Givens story since 2001. It is an idea that he got from actor Timothy Olyphant. Justified’s creator Graham Yost explains, “It started when (Leonard) was visiting the set in the first season and Tim said to him, ‘Hey, why don’t you write another Raylan short story?’” It must have been a somewhat surreal moment for Leonard, his own character standing there telling him to write some more about him.

While many television characters drawn from literature exist on screen and in print simultaneously, these tend to be steadily diverging universes. The pilot episode of Showtime’s Dexter closely mimics the opening chapters of Jeff Lindsay’s Darkly Dreaming Dexter, but by the end of the first season the entire cast of characters has become radically different. On the show, the villainous Ice Truck Killer is defeated, but in the novel he escapes after taking down another principle character. Multiply this effect by five subsequent seasons and five more novels and the plot lines of the two Dexter universes have hardly a passing resemblance beyond the main character.

But Justified’s universes are not diverging; in fact, they’re tangled together more with every installment. Because Elmore Leonard is an executive producer on Justified in more-than-name-only, he often feeds potential story ideas to the writers. As Leonard explains, “I've never just taken money, I've always had to write something. So I felt I should, since I know these characters better than any of their writers. But I didn't want to interfere with them, any stories they might have in mind. I thought mine would be just filler. And they've been using them.” In turn, the writers of Justified routinely consult Leonard’s novels for dialogue and tone, and allegedly have blue wristbands stamped WWED … What Would Elmore Do?

Justified’s creator Graham Yost explains, “In his new book, Raylan, it’s this weird back-and-forth thing we’ve got going on where he’s using characters we’ve created for the show in his new stories.” Meanwhile, Leonard downplays his own role to some degree. "I don't ask them what they're doing. I always keep away from them […] I'll do some episodes I think will work and they can use little bits then to sprinkle into thirteen episodes. I don't want them feeling that they have to use my stuff, because I'm not a screenwriter, and they have good writers. I think they have very good writers." But as Yost describes it, the show relied a lot on Leonard. “He wrote this novel … and said, ‘Hang it up and strip it for parts […] And so we did. There were two big chunks that we took from it last year, and thematic things and characters. And there’s a couple of big things we’re taking this season. If there’s a fourth season, there’s a few more things we’d like to mine from the book as well.”

[image error]

Promotional Poster for FX's Justified, Season 2The result being that the character of Raylan Givens and the world of Harlan continue to evolve not just in two mediums, but between them in a way never before seen.

In Season 2 of Justified, Raylan is tangled in an old feud between his own family and the Bennett clan: Mama Mags and her sons Dickie and Coover run the General Store in town as well as the marijuana racket for a thousand acres in either direction. Dickie and Coover appear in the Raylan novel as members of the Crowe family, and their father Pervis minds the store while his boys are off plotting to kidnap men, remove their kidneys, and sell them back – a plotline which arises in Season 3 of Justified.

On the show however it is Dickie Bennett and his neo-Nazi friend Dewey Crowe who are nearly the victims of the kidney thieves. Lovably-stupid Dewey Crowe has been on the show since the pilot episode, where he is reprimanded by Givens for stepping into a lady’s home without knocking – a scene taken nearly verbatim from “Fire in the Hole”. In both the episode and the story, Raylan chats with Dewey about having previously locked up one of his kin, a fellow by the name of Dale Crowe Jr., who Givens drives to jail in the opening of the novel Riding the Rap. Justified’s writers closely-adapted this dialogue in the second episode of the first season when Givens transports Dewey to jail.

Confused? Then let’s not even get into the recent Season 3 appearance of Assistant Director Karen Goodall, played by Carla Gugino, who is based on Leonard’s character Karen Sisco from the novel Out of Sight, which was adapted into a Soderbergh film in 1998 starring George Clooney, and featured Jennifer Lopez as US Marshall Karen Sisco. The film was far more successful than the briefly-lived 2003 television show it inspired, a cop drama that aired on ABC for one season called Karen Sisco, starring— wait for it— Carla Gugino as Karen Sisco. Is Karen Goodall the Karen Sisco of the novel, the movie, the television show, or someone new entirely? All we do know is that the writers seem to be enjoying themselves, inserting dialogue that practically winks at viewers-in-the-know, about how Gugino’s character married, changed her name, and got divorced.

Perhaps the most startling effect that the show has had on the book pertains to the brilliant character of Boyd Crowder. Boyd is a spiky-haired chameleon: a neo-Nazi one episode, a bible-thumbing revivalist in the next, then a dusty-faced coal miner, then a suit-wearing bodyguard for the mining company. His loyalties are forever-shifting and his diction is always precise, making Boyd the perfect foil for the laconic but constant Raylan. Their odd bromance propels the show. Each respects the other somehow, and whenever they square off against one another, you can see they hardly can bear to shoot (until they do).

Both the pilot episode of Justified and Leonard’s 2001 story “Fire in the Hole” end with Raylan shooting Boyd in a scene which eerily mirrors the duel with Tommy Bucks. In the original story Boyd dies, but on the show his life is barely spared. Graham Yost is quite grateful that they dodge that particular bullet on the show. “We thank our lucky stars every day that we didn’t go through with that — and that was suggested by FX, by research and by Elmore. He said, ‘Oh, you should keep that Boyd around.’” Leonard apparently took some of his own advice. In the novel Raylan, Boyd is inexplicably alive again, resurrected thanks to the character’s success on the TV show.

How do we talk about a book, based on a TV show, based on a book? A review at The New York Times chooses to take Leonard’s latest novel on its own merits and barely mentions Justified. But pop-culture website The AV Club criticizes the novel specifically for failing where the show triumphs: creating cohesive episodic plots with consistent character development. They conclude that Raylan is a “complicated culture artifact” where the adaptation almost seems more definitive than the original.

But it was a review at Slate that put its finger on the real conundrum here, observing that “Justified may be the first show to inspire fanfic from its creator.”

The first, perhaps, but likely not be the last. The close relationship between novelist and TV show seen with Leonard and Justified is an inevitable progression of the one formed by Jonathan Ames and HBO’s Bored to Death, which was based on a short story by Ames. In the show, Jason Schwartzman plays a character named “Jonathan Ames” who pretends to be a detective on Craig’s List. The real Ames continued to write for the show and at one point even guest-starred as a villain that the character-Ames had to defeat. The show was just cancelled after three seasons, but HBO, along with producer Scott Rudin, has gone on an acquiring spree of late, signing contemporary writers left and right to produce new shows. Mary Karr will be adapting material from her three memoirs into a new show. Jonathan Safran Foer is due to write a new comedy that will star Ben Stiller. Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! will also be brought to life on the small screen, and of course there is no better example of the altering landscape than Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections.

In 1996, before The Corrections was published, Franzen wrote distastefully about television in his famous Harper’s essay “Why Bother?” and viewing it as something that had moved Americans regrettably farther and farther from what he calls the substantial novel. He wrote, “Just as the camera drove a stake through the heart of serious portraiture, television has killed the novel of social reportage.” Fast-forward sixteen years and today Franzen has not only sold his novel to HBO, but he’s said that he’s going to the casting sessions and is enjoying writing new backstories for main characters and fleshing out more minor ones. In an interview last year with David Remnick of The New Yorker, Franzen noted that because the show is a series and not a miniseries, he even sees the potential to develop things beyond the original novel’s boundaries.

Why the drastic change in tune? Because of course “It’s not TV. It’s HBO.” In the last sixteen years,[image error]

Olyphant as Sheriff Seth Bullock (HBO's Deadwood) HBO has pioneered new kinds of novelistic storytelling in mainstream television. A year after Franzen’s laments in Harper’s, HBO began airing Oz, and two years later, The Sopranos, both of which featured large casts of morally-complex characters from all walks of life, who are developed steadily through the intricate weaving of subplots. Like many great works of literary fiction, some of these shows like The Wire could be challenging at first: occasionally slow, difficult to follow, and hard to stomach. Favorite characters were apt to be killed off, while even small changes in others took multiple seasons to develop. Yet audiences grew to appreciate the many rewards, including a feeling of seeing something realer than we’d thought television could express. Since then the HBO model has left the nest and roosted at non-premium cable channels like AMC, with Mad Men and FX, with Justified. It’s no coincidence that Timothy Olyphant learned his rogue lawman character first as Sheriff Seth Bullock on the set of HBO’s Deadwood, a historical Western drama about 1870s South Dakota.

We forget that it was the dime novel cowboys and pulp magazine detectives of the 20s and 30s who eventually became the first radio heroes of the 40s and the television heroes of the 50s. Slinging guns and cracking wise, characters like Gunsmoke’s Marshal Matt Dillon or Martin Kane, Private Eye walked the same lonely road between law and lawlessness that Raylan Givens goes down today. So-called genre fiction has always broken barriers between popular and artistic cultures, and Elmore Leonard has long been a master with a foot in both camps. His hardboiled storytelling is always surprisingly rich and never clichéd. It exactly is why so many of his books have been adapted into such memorable films: Three-Ten to Yuma, Get Shorty, and Out of Sight.

While promoting Raylan, fans have asked Leonard whether or not he plans to continue writing more Raylan stories. Leonard admits, “I'm tempted to put the character Raylan into my new book, and my agent in Hollywood says no, don't. And I'm not sure why, outside of the fact that Sony owns the rights to the character and I can't sell the book on my own to somebody else if Raylan's in it. So that's probably it. Well, he's an agent. I may put him in anyway.” Even Leonard doesn’t quite seem to know who truly owns Raylan Givens at this point.

But whatever road Leonard and Raylan go down, it is sure to interest both viewers and readers, and to shape fresh possibilities for the future of both television and literature. If Justified is indeed a harbinger of things to come, then the further-entwining of television and literature is bound to raise many hackles, and critics will surely expend much ink (or many pixels) lamenting the selling-out of novelists, the deficiencies of television, or the death of literature forever and ever (amen). But perhaps the education that HBO is providing television viewers is actually leaving more of us still hungry for more. Perhaps an evening of watching FX will prompt a curious pause at a bookstore the next morning. If television viewers continue to embrace rich, complex, novelistic storytelling, then yes, we can expect more writers like Leonard, Ames, Carr, Foer, Russell and Franzen to be drawn to the form. But we can also anticipate that these shows will likewise draw viewers back again towards their tremendous literary works.

As more and more the lines become blurred, fresh possibilities are opened in both forms. Readers will be on the look-out for changes, and thinking about how what they’ve seen informs what they read. Viewers will be wary of how what they’re reading shapes how they view.

For example, nothing physically defines the character of Raylan more than his hat. It is inevitably the first thing characters mention to describe him. In Pronto, bookie Harry Arno asks his girlfriend, Joyce, if she’s seen anyone odd downstairs. She answers, “‘How about a guy in a cowboy hat? Not the kind country-western stars wear. A small one. Like a businessman’s cowboy hat.’” Harry replies, “‘I know what you mean, the Dallas special […] That Stetson, the kind the cops were wearing when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald.” Joyce agrees. “‘That’s the one. Light tan, or sort of off-white.’” By making the historical reference Leonard creates a kind of equivalence here in a reader’s mind between the morally-complex Raylan and this disturbing historical artifact of the police standing by as vigilante justice is done.

[image error]

Jack Ruby Shooting Lee Harvey OswaldIn Riding the Rap, Leonard describes Raylan again as he drives Dale Crow Jr. to prison. “He had on one of those business cowboy hats, but broken in; it looked good on him, the way he wore it cocked low on his eyes.” This emphasis on his hat being business-like but worn down is echoed in “Fire in the Hole”, Leonard has Raylan’s boss, Art Mullen, reflect on the hat when they are first reintroduced. “The kind Art Mullen thought of as a buisnessman’s Stetson, except no businessman’d wear this one with its creases and just slightly curled brim cocked toward one eye, the hat part of Raylan’s lawman personality.”

But in the pilot episode of Justified, the hat Olyphant wears is not what Leonard initially had in mind. “The critics have been calling Raylan a cowboy with his hat. The hat came unexpectedly [with the show]. I had described kind of a businessman’s Stetson, a smaller Stetson. […] But evidently he found his own hat and design. It’s perfect. I don’t see him bareheaded. He seems to need a hat to define who he is.”

Leonard here seems to defer his own vision of Raylan’s hat to the one on the television show. Indeed,

[image error]

Cover of "Raylan" by Elmore LeonardCover of "Raylan" by Elmore Leonard his praise of Olyphant’s Raylan is always effusive in interviews. “Tim Olyphant plays the character exactly the way I wrote him. I couldn't believe it. He's laid back and he's quiet about everything but he says, if I have to pull my gun, then that's a different story. And it works. There are very few actors that recite the lines exactly the way you hear them when you're writing the book. George Clooney [in the 1998 movie "Out of Sight"] was one. He was very good.”

Clooney was very good, but Olyphant is exact.

So much so that his picture is even on the jacket of the Raylan novel, the broad hat pulled down low over his eyes as he points his gun over the reader’s shoulder. It is the exact image used in promotions for Season 2 of Justified. Open the book up and start reading, and you’ll find that there is no description of Raylan’s signature hat anywhere to be found. There is no longer any need for it.

TweetMarch 6, 2012

"Indehiscent" in Shaking Vol. 1

On sale today! Copies of the very excellent literary magazine, Shaking ONE, put together by editor Vito Grippi of Shaking Magazine and featuring one of my very best short stories, "Indehiscent"... which was featured on this site as part of the Dictionary Stories sequence last year.

"Indehiscent" is a special story for me for several reasons. I began writing it in a class with Alice McDermott my Junior year in college, and finished it my Senior year in Jean McGarry's graduate seminar on Landscape and Setting. It was the first story of mine that I was ever wholly satisfied with upon finishing it, and the one I used to apply to graduate school later that year. This makes it not only my first real story, but my oldest story, and it's an honor to have it in Shaking alongside works by Curtis Smith, Jennifer Taylor, Emma Briant, and Travis Kurowski.

Read a short excerpt below, and buy your copy online today!

***

Blair Dovedale leaned on her bedroom windowsill, watching a fat green caterpillar creep from one end to the other. Its legs wiggled, its body bunched up and it inched blindly forward. Curious, she held a trembling hand out over it and blotted out its enormous sun. It froze and then continued its journey. With one shaky finger she touched its back. The tiny creature went into a terrible panic at first and then seized up in total paralysis. She waited to see how long it would take for it to recover. Eventually she got tired of waiting for it to start moving again and fell backwards onto her bed.

The gloom of her bedroom was impervious to the brilliance of summer that hovered around the curtains of her window. Glossy posters of figure skaters covered the pale white walls. These athletic teenage girls held bouquets of flowers and smiled at crowds of adoring fans. Or they were frozen on skates: intensely absorbed in their performance. An autographed poster of the 1994 U.S. Olympic Team that hung above her bed, once her most prized possession, now lacked two of its corners and hung crooked.

She’d been five then. Watching the Games late at night, falling asleep in her mother’s lap each night before the final scores had been tallied, asleep to dream of her own imminent stardom. Afterwards her mother had taken out subscriptions to every fan and hobby magazine available and when these failed to curb Blair’s enthusiasm, she took her to practice at the downtown skating rink on weekends. Then she started taking Blair in for private lessons after school after about a month. “You’re got what it takes, bay-bay,” her coach, a Ukrainian man named Maxwell Silver would shout from the stands.

Now, magazines lay all around the room in uneven, disorganized stacks. It hadn’t been that long ago that Blair had lain in bed at night, imagining that she was a girl on a poster. Lately, she found herself ignoring a growing urge to tear them all down and shred them into tiny pieces. Only the thought of the cold, bare walls beneath kept her tucked tightly beneath her heavy cotton sheets until morning.

[For the rest, head on over to Amazon to buy a copy... and for more great "prose that rests on the fault lines of literature and stirs our understanding of humanity" check out Shaking's Website here!]

February 29, 2012

Short-listed for the 2012 Fish Short Story Prize!

[image error]

Fish Publishing (Ireland)Just found out my story is short-listed for the 2012 Fish Short Story Prize... which is actually a "short" list of 145 stories... but it does mean that my literary idol David Mitchell is actually going to read my crazy-ass story about an imaginary prog-rock band called "The Uraniums" whose members each become recluses after their first-and-only gig!

The final winners will be announced on March 17th... assuming David Mitchell can read 145 stories between now and then, I guess, which I believe if anyone could do... he could.

(The official link is here, although the site has been crashing all day... probably because all of the other writers who submitted work are checking the list.)

The story was originally written as part of my Dictionary Stories challenge and posted right here on this website, so thanks to everyone who read it and sent comments! I had to take the full story down, but below is a short excerpt:

***

[image error]

The Uraniums played just one show at The 92 Club before splitting up for good in October of 1963. Though the American President John Kennedy wouldn’t be assassinated for another month, the country at this time was already fogged over. Already it seemed like nothing could stay together very long. The 92 Club was a dank pub basement outside of Cambridge, best known in those days for booking folk acts like Dylan and Baez for crowds of Harvard and BU undergraduates. Even today the 92 Club strictly admits no more than 175 rock and roll fans at a time, as dictated by the fire codes, but receipts from that night show that 238 ticket stubs were sold and ripped. 238 hands were stamped and 238 one-drink minimums were bought and paid for and 238 pairs of ears were treated to a truly singular experience in Rock and Roll history.

When I say it was singular I mean every aspect of this word. Uncommon, peculiar, never reproduced – all apt descriptions. But it was so much more than just that. On the powder-blue graph paper of a mathematician, a singularity is a point of un-definition. An exceptional set which fails to behave as expected. A seemingly ordinary course of data will suddenly “explode” (their terminology) to plus-or-minus infinity and lose all describable character. It is my contention that this is precisely what the band’s founder, Theodorus Hamilton, accomplished that night in Boston, in 1963. But think also of the impossibly empty universe of the astronomer, where a singularity refers to a black hole – a point with no volume and infinite density, because at this point all matter is obliterated by limitless gravity. I do not mean to be hyperbolic when I assert that this was the case at The 92 Club that evening, in the vibrations of Sarah Dickens’s mandolin, and yet, one final time let me suggest that even though Science Fiction author Vernor Vinge had not yet authored the short story “Bookworm, Run!” in which he’d extend the concept of the singularity to technology – a threshold where the intelligence of machines surpasses that of humans – that the intellectual event horizon was indeed breached that night as the guitars and amplifiers of Roger Barnacle and Jackson Press.

What’s startling, perhaps, is that The Uraniums had never played a show together before. As a nine-some, no one, the band included, quite anticipated what the results would be. The nine of them had never actually rehearsed all together, because the only time keyboardist S.L. Miles showed up to the early sessions, accordion player Penny Orbach was being held for questioning by the Boston Police in connection with some spray-paintings that had cropped up over in Chinatown. By the time she was released, Miles had been forced out of town by a family emergency.

The result being that even the nine members of The Uraniums had no means to expect that the history of rock music – and indeed the history of America herself – would be irreversibly altered on that evening in 1963. Indeed, absolutely no one expected much of anything, which is why, tragically, no recordings were even made. The Uraniums spoke about the 92 Club gig as little more than a toe-in-the-water, just a rehearsal for a bigger show later that month at the nearby Watertown Community Center – which would, for various complicated reasons, never happen. The 92 Club show would be their only performance and were it not for the 238 witnesses (myself included) the impact of The Uraniums would have fizzled out into nothingness.

***