Sonia Marsh's Blog, page 5

November 27, 2016

Last Minute Glitch in Completing My Peace Corps Project

The day before the completion date of my Lesotho school renovation project, I got a phone call from my counterpart at 7 a.m.

“The contractor needs you to buy 115 meters of electrical wiring.”

“Why didn’t he tell me this before? We are running out of money.”

“He didn’t know,” my counterpart said.

“How much does it cost?”

“48 Rand a meter.”

I quickly calculated a total of 5,520 Rand (almost $400.)

This meant we were now 15,000 Rand ($1,065) over the contractor’s initial quotation for materials, and neither the contractor nor the teachers seemed concerned about this, and I know why. They thought I could keep dishing out cash like an ATM machine, despite my warning them about the $5,000 limit set by the Peace Corps.

At first my contractor said, “I’ll take the taxi to town and back.”

I knew from my weekly trips to Maseru, suffering inside a cranky, old, Toyota van with 25 people sitting on top of each other, that it would be impossible to get to town and back without wasting the entire day.

Public Taxi. This one is not yet full.

“How will you fit the wire inside?”

“I put it on the roof,” he said.

“There is no roof rack, plus the taxi has too many people.”

My contractor laughed.

This was the fourth glitch during a 17-day project requiring me to figure out a way to get my contractor to Maseru and back with the extra materials. I made sure to tell him, “Now make sure you have everything you need as I’m running out of money.”

Fortunately I’m friends with a local white business owner who has a couple of trucks. He was born and raised in Lesotho, and is therefore fluent in Sesotho and knows the contractor. In exchange for his “emergency” transportation help, I’ve given him a couple of computer lessons.

I also had to figure out how to get to the bank and withdraw the last of my project cash. I did not like the idea of carrying all that cash in a public taxi, so another friend of mine, Jennifer, the owner of a lodge said she would take me to the bank.

Later that morning, I received another phone call from my counterpart. “Can you buy one kilo of sugar and more meat for the workers?”

“There’s only one day of work left,” I said. “I just bought 5 kilos of chicken a couple of days ago. Can’t the workers eat bread and peanut butter for breakfast? I know we have a jar.”

The requests were never-ending, and I was happy when the project ended.

Fortunately, due to not skimping on transportation costs, and eliminating Phase III of the project, (the floor tile) due to overspending on materials, we got everything done on time. I kept reminding the workers that I was leaving for the Christmas holidays and that everything had to be done by November 25th, and they managed to finish at the last minute.

I bought a chocolate cake in town to celebrate, and despite the Principal, my counterpart, and two teachers not showing up, there was more cake to celebrate for those who did come to school.

The post Last Minute Glitch in Completing My Peace Corps Project appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

November 20, 2016

My Opinion on How to Get Things Done in Lesotho

My opinion on how to get things done in Lesotho is based on treating people like I’d want them to treat me.

In the case of my school renovation project, it looks like the work will be completed before the scheduled date of November 28th. How come? Because I believe in signing contracts, treating people with respect, and:

paying people on time, according to our agreement.

In the U.S., projects have deadlines, and we do everything we can to meet those deadlines, because there are consequences if we don’t, like the risk of getting fired.

Here in Lesotho, the work ethic is completely different. If things aren’t accomplished on time, so what? No one is surprised; at least that’s what I’ve experienced in the 13 months I’ve been here. Perhaps things are different in the capital city, but somehow I doubt it.

For example, I was “promised” a cabinet to store all the wonderful donations I’ve received from generous people who wanted to improve my school. Supplies that we take for granted are lacking in my rural school such as: crayons, activity books, flash cards, pencils, felt tip pens, Sharpies, glue sticks, scissors, and let’s not forget the stickers that children love. My counterpart teachers advised me to keep everything at home until we could lock them up at school, otherwise they would soon disappear.

The principal said, “Children steal pens from each other,” which explains why several have nothing to write with. My Principal allows one new pen per semester, and basically “tough luck” if they don’t have a pen to write with.

So I’ve been waiting for a cabinet to lock these donations up since February, and I finally got one with a broken lock last week; it took nine months to get it, and school is almost on summer break, until January 23rd, 2017.

The Cabinet I’ve waited 9 months has finally arrived from another classroom.

Fortunately, the wonderful team I have working on the school project, replaced the lock on the same day. I no longer have to schlep everything from my rondavel, up the hill, to school.

We all know that money motivates people to work, especially in a poor rural villages, like mine. I’ve experienced time and time again, workers who are promised payment once the work is done, and who are then told, “There’s no money.”

So I’ve made sure to pay the work crew and cook, the money that we agreed upon, and they know I will. None of those excuses, “Sorry, I have no money,” a common excuse where I live.

I’ve also made sure that the work crew are well fed, as I heard, during my Peace Corps project workshop, that workers expect to get a meal. So the cook I hired, bakes fresh bread at home (there are no supermarkets in my tiny village) brings it to school, and then cooks lunch in the 7th grade classroom, since those students are no longer attending school.

Daily cooked fresh meals by a wonderful cook from my village.

So I hope that some lessons can be learned in my community on how to accomplish projects in a timely manner.

The post My Opinion on How to Get Things Done in Lesotho appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

November 13, 2016

Jealousy Over a Radio in My Village

“I’ll take the radio back to the shop if it’s causing arguments,” I yelled. “I’ve had it with petty gossip and jealousy in this village.

“This radio has caused nothing but problems, and all I want to do is help.”

My host “mother” was shocked to hear me yell at her.

“Take the radio,” she said, pouting.

I never wanted the radio in the first place. It was a gift from the electrical supply store in Maseru where I spent a lot of money on wiring, and a meter box for my school renovation project.

Normally stores give discounts when customers spend a fair bit of money, but this store decided to give me a “free” radio/CD player instead.

Exhausted from my awful bank incident, I was in no mood to argue for a preferred discount, so I took the radio, without realizing the consequences.

My co-teacher, the electricians and the contractor admired the radio, and I did not think twice about it until it caused a problem.

At first, my co-teacher said she wanted to listen to music in bed that evening.

“You already have a large radio and speakers, don’t you?” I asked.

“Yes, but I’m so tired, I just want to have it next to me so I don’t have to get up.”

I laughed, and mentioned I was curious if this radio had better reception than my tiny one.

“Why don’t you take it home,” she said. “I want to sleep.”

I tested the radio in my rondavel, and realized that the reception for BBC World radio was worse than on my small radio, and the new one took up half my table top, so I decided to take it to school.

My small radio has better BBC World reception tan the large one.

My host mother saw me with it, and said she needed a radio. Her little one sounded crackly, and so I told her she could borrow it.

“I’ll buy it from you when you leave,” she said.

I did not respond, as I knew that she would hope expect me to give it to her as a “goodbye” gift.

When I reached school, my counterpart teacher asked, “Where is the radio?”

“I left it with Mary,” I said.

“It belongs to the school,” he replied.

“Actually it’s mine to decide what I do with it,” I replied crossing my arms over my chest.

“No, it’s for the school, not for Mary.”

Now I raised my voice and said, “Why should I bring the radio to school? So you can play your music? The holidays are coming and I promised Mary she could keep it until school starts again.”

I’ve become more assertive after one year of living in my village.

When I got home, I told Mary that the teachers wanted me to bring the radio to school, and that I would let her use it during the holidays, but I’d bring it to school after that.

“Those people want it for themselves,” she said.

“Mary, I don’t care. You told me everyone is jealous here, and now you’re acting the same.”

“Yes, everyone is jealous,” she said.

“Take the radio,” she said, frowning.

“I feel like digging a hole and burying it so no one gets it,” I said.

The following day, the young electrician asked me if I had a radio. I said, “No.”

The electrician who has installed lights in the staff room at school.

Now I felt bad as the crew is working hard and they know I have the radio from the store. They want to play music while they work, and I hate to disappoint them.

This damn radio has caused so many problems. I hate it. Now I look like the bad guy.

I wish I’d received a discount on the materials. This would have avoided all the jealousy in my village.

The post Jealousy Over a Radio in My Village appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

November 6, 2016

My Experience Working With A Contractor in My Village In Lesotho

I woke up at 4:20 a.m., excited and anxious about working on a construction project with a local contractor from my rural village in Lesotho, and his team of workers.

I kept my fingers crossed there would be no glitches, and that we’d buy all the materials at the Basotho equivalent of “Home Depot.” After that, I’d offer lunch to everyone at KFC in Maseru, and then we’d drive back in the rented truck and reach my school by early afternoon. That was my plan.

‘M’e Mamoshaka, a teacher at my school asked me to head over to her house at 6:15 a.m. She likes to sleep late, so I was pleasantly surprised to find her up and dressed. She was frying frankfurters in oil, and wrapped them in two slices of bread and stuffed them in her purse. As we headed out the door, she tossed her empty water canteen to a woman who happened to be heading to the village tap, pushing empty canisters in a squeaky wheelbarrow. I still don’t understand how serendipity works in the Basotho culture. Their timing is perfect, while I’m always struggling with my American time schedule.

Just as we boarded the taxi at 6:33 a.m, the woman handed over the filled water canteen to ‘M’e Mamoshaka, and my contractor, Ntate Makae, magically appeared twenty seconds before our taxi van stopped by his house.

As we headed towards the main taxi rank in Maseru, traffic built up reminding me of the bumper to bumper traffic on the 5 freeway in Los Angeles. The only difference here is that when drivers get impatient, they pull over to the opposite side of the street, and drive on the sidewalk, against traffic. Are you kidding! The driver dodged cars heading straight towards us, as pedestrians jumped for safety. When we finally reached Maseru taxi rank, we headed over to the “Salman” hardware store. The store clerk hand wrote each item we needed, and I soon realized this was no “Home Depot.” After thirty minutes, I pulled out my bank card and paid.

Suddenly, two young men joined us, and I found out that they were here to work with Ntate Makae, so now I believed everything was under control, and well-organized by my contractor.

The Team

An old, beat-up truck pulled over, and a burly man gestured to ‘M’e Mamoshaka and myself to get in the front seat. At first I wondered how all five of us, plus the driver would fit inside, but I’d forgotten that in Lesotho, you can sit in the truck bed without getting arrested.

We headed over to City Lights to purchase the electrical items on our list, but my contractor had forgotten to add a meter box and the extra lights for 11 classrooms.

This time, my bank card was declined, and I panicked. I called the Peace Corps office to ask for advice, and they told me to go to my bank, and get the cash out. I was not keen on carrying cash on the streets of Maseru, but that seemed to be the only way.

So we asked the burly truck driver to take ‘M’e Mamoshaka and me to the bank. His truck wouldn’t start unless it was put into gear and pushed, or faced downhill. We finally got moving, and I started shaking my head when I saw at least 100 people waiting in line outside the bank. The line snaked around the building and I realized there was no way we could stand here. We would waste the whole day to get to the front of the line.

‘M’e Mamoshaka said, “Follow me.” An older woman stood at the information counter, and even she had about ten people waiting to talk to her. ‘M’e Mamoshaka grabbed my elbow, “Wait here.”

As soon as the older woman was free, she asked me to explain my dilemma.

“I will put you in this line today,” the woman said. It was a shorter one with around twelve people, “but next time you have to go to the end of the line.”

I thanked her, and then counted the people in front of me. Two hours later, I was about to strangle someone. I started doing leg lifts, shoulder raises and calf raises, as the blood in my body had stopped flowing. The line barely moved, and with only three cashiers for 100 people, many of them cutting in line, my patience had become non-existent.

When I finally reached the cashier, he asked me for my passport, which I didn’t have with me. I’m always scared it will get stolen in Maseru, and I only take it when I’m crossing the border to South Africa.

I had my California driver’s licence with a photo, and my Peace Corps ID with a photo as well. He didn’t seem to allow either one, until a Supervisor came by and allowed the transaction to proceed. I was just about to explode, and that would not have been a pretty sight.

Our driver stood outside smoking a cigarette. He had positioned his truck facing downhill, so he could jumpstart it.

We returned to City Lights, and I took the cash envelope and requested permission to go behind the burglar bars to count the cash. I’ve never paid for anything with this much cash, and meanwhile, the men loaded the truck.

Construction guys helping with electrical

Stupid me kept thinking this truck was a temporary one, and we would transfer everything into a much larger truck later on. I also believed that ‘M’e Mamoshaka and I would have a comfortable seat in the bigger truck, but it wasn’t until we stopped to collect thirty-one, 6 metre (20 foot) wooden rafters, and six 50-kg bags of cement, that I realized Ntate Makae was planning to use this old-piece of shit truck.

Everyone was starving, and I’d told everyone we’d stop for lunch, but they insisted on getting the truck loaded.

Five men sat on crates in the warehouse, doing nothing. We waited thirty minutes, while the truck driver said he needed to fetch gas in a jerrycan. He asked me for money, to buy gas, and we had barely driven anywhere, but he claimed his tank was empty from taking us to the bank.

“He lying,” Mamoshaka said.

“Lets go to KFC and get a private taxi to take us home after that,” I whispered in ‘M’e Mamoshaka’s ear. I had visions of this truck not making it up the mountains to my village, and the guys at the warehouse hadn’t budged in the last thirty minutes from their crates.

A private taxi picked us up after lunch, and we headed back to our village in the mountains.

Afternoon traffic was getting heavy as it approached 4 p.m. I wondered if the truck had left yet, so we called and Ntate Makae who told us they were almost on their way.

‘M’e Mamoshaka and I got home at 5:45 p.m. It was still light and we called Ntate Makae again and he said they were close to my village.

By 7:30 p.m., they were having trouble climbing the mountain; the load was too heavy for the crappy truck, so they were stuck. They had to call a teacher from my school who arranged for a second truck.

It wasn’t until 9 p.m., that I received a call to say they had made it. Dressed in my pyjamas, I asked Mary my host “mother” to come with me. I carried my solar light, as I cannot see a damn thing in this rural darkness.

I pointed the light at two trucks outside: one large one, and the small, dilapidated one. All of the heavy stuff, including all the wood, had been transferred to the large truck, which I later found out belonged to one of my teachers at school.

Quite proud of myself for taking the private taxi home, rather than waiting for the truck to make it to my village, I was able to go to sleep and feel satisfied that the team could start work on the following day.

The post My Experience Working With A Contractor in My Village In Lesotho appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

October 30, 2016

Cultural Differences On How We Treat Dogs

It’s tough for dog-loving people to understand why dogs are treated poorly in many parts of the world.

In the comforts of our homes, we treat our pets like family. We buy them food and toys, we let them climb onto our beds, we cuddle them, we take them to parks so they can play with other dogs, we take them to the vet when they get sick, and we protect them from diseases by giving them their shots. In fact, us dog-lovers treat our dogs like a son or a daughter, and mourn their death, in some cases, more than the death of a relative.

But now I live in a rural village in Lesotho, where people don’t have enough money to buy milk, eggs, and meat to feed their own children, so why should they be able to afford meat, milk and dog food, for their animals?

This post is not meant to make you feel heartbroken for Shaka—the dog that belongs to my Basotho host family–it’s to point out some major cultural differences.

In my rural village in Lesotho, dogs do not sleep in people’s homes; they are solely there to guard the property. I am often awakened by dog fights in the middle of the night, often ending with a dog yelping in pain.

That does not mean I don’t have a heart, and care for Shaka.

In the beginning, Shaka followed me on my early morning walks. She took on the role of protecting me from Bo-Ntate (men) clad in the Basotho blanket. When I passed them on the dirt path, Shaka would start growling at the Bo-Ntate. I knew that sooner or later, one of them would pick up a stone, and throw it at her. My walks became stressful and unpleasant, so I started leaving her home, chained up, which also bothered me.

Shaka recently had her first litter, and Mary, my host “mother” told me her son would take care of the puppies. I believed her, until I heard that he was looking for a job, and was no longer in my village.

Shaka’s seven puppies

Shaka’s first puppy was born when I unchained her so she could get some exercise. I hated seeing that heavy chain around her neck, but Mary warned me someone could steal her and I didn’t want to be responsible for that. So I asked permission to let her run for a while, and that was when she squatted and a puppy was born. Shaka left her newborn on the grass and ran away. She didn’t seem to know what had happened. I waited for her to come back and pick it up but she was hiding in her tiny brick shelter. I charged home, grabbed an old T-shirt, and carried her puppy over to nurse.

The following morning, I found seven puppies nursing. Shaka was starving, and needed protein and milk, but was only given a bowl of water and papa, (maize meal) the staple of Lesotho. There is very little nutrition in this starch, and the children at my school eat if every day. They also need protein to supplement their poor nutrition, just like Shaka.

Shaka stares at my front door with sad eyes, begging for something more substantial.

I cook some oatmeal and add long-life milk, which she gulps, but she’s still hungry.

I cook rice in chicken stock, and gave her the skin off a roast chicken I had bought in town.

I try to hide the food I give her, as I feel guilty that the children next door only get dry bread and papa to eat. They cannot afford butter or peanut butter. I often see the young seventeen-year-old mother, next door, picking green leaves (which look like weeds) and cooking them in her black, cast-iron pot over a fire made from twigs.

The people in my village are shocked that I care so much about Shaka and her puppies.

It’s a difficult situation, and when I explain how we treat dogs in America, no one understands that we allow them to sleep in our house, and care for them as part of our family.

The post Cultural Differences On How We Treat Dogs appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

October 23, 2016

Children in My Village in Lesotho

I am amazed to see how very young children in my rural village in Lesotho, are left to entertain themselves without toys or adult supervision.

As I sat on Mary’s porch, I watched these, one to three-year-olds, playing together with stones that they lined up or rolled on the tile. This kept them busy for about two hours without a single child crying or whining. They are so used to figuring out how to keep busy with nothing other than what they can find in nature.

Things are different at my school though. It came as a shock to see how children are often treated as ‘servants’ who are pulled out of class to run errands for the teachers. They have no choice, and are expected to obey, without ever questioning the teacher: “Why are you making me skip class to collect your cell phone at so-and-so’s house?”

When the child returns with the cell phone, the teacher grabs it, without a “thank you.” It’s expected. Rarely do I hear a teacher thank a student.

I understand why my own students grab pencils and pens from me, without saying, “Thank you.” I don’t put up with the lack of good manners, so I hold onto the pencil and say, “What do you say?” Often they are unsure of what I mean, so I ask them to repeat, “Thank you ‘M’e Sonia.”

I’m not opposed to children helping at school, it just bothers me when I see ten-year-old children carrying heavy desks across the school property. Once I ran over to help them lift the desk over a step, and one of the male teachers yelled, “’M’e Sonia, you should not be doing that.”

Eating porridge with fingers

Twice a day, after the morning liquid porridge, and the maize meal with dried beans for lunch, I see tiny, under-nourished, first graders schlepping buckets of water uphill, to wash their plastic lunch containers. They wash their dishes in cold water with no soap. Their hands are sticky as they scoop liquid porridge with their fingers; they don’t have spoons. The teachers have spoons and proper bowls, but not the children. It reminds me of the three little bears, where Papa Bear has a big bowl, Mama bear a medium bowl, and baby bear has a tiny bowl. This is definitely a culture where the adults get fed more, and (meat, if there happens to be a special event, like Moshoeshoe Day) and the kids don’t.

During lunch, the children are expected to serve the teachers breakfast and lunch. When they want water, the teachers point to their plastic bottle, and the child runs to the tap and fills it.

Girl mopping 7th grade floor

Fridays are always “cleaning” days, and the children in each grade run into the woods to get branches to sweep the floors in their classrooms and the front yard. They sweep the staff room, and attempt to dust the tables in the staff room with a dirty rag.

Sweeping the grass while the teachers stand and watch

Can you imagine asking our 1-3 year-olds in America to entertain themselves and our primary school children to clean the floors and sweep the grass?

The post Children in My Village in Lesotho appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

October 13, 2016

Please Help Me Raise $5,000 to Make My School Safe

I need your help to raise $5,000 to improve the safety and education of students at my rural school in Lesotho, Africa.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO MY PROJECT IN LESOTHO

(Scroll Down Until You Reach S. Marsh)

All donations are sent through the Peace Corps and are

TAX DEDUCTIBLE DONATION

Your donations will go through the Peace Corps Partnership Program funds website.

My community has agreed upon the following 3 priorities to help our school.

Collapsed ceiling in Grade 5

1). Make a safe classroom environment for 5th grade students.

Half the roof and ceiling collapsed in July, due to the unusually heavy snow storm, and I’m worried about our safety.

Students want to learn computer skills

2). Electrical wiring of all classrooms to teach computer skills.

My village now has electricity, however, the classrooms have not been wired due to a lack of funds. Since we received four desktop computers from the Minister of Energy, the teachers and students would like to learn how to use them.

Cracks on cold cement floors in classrooms

3). Install vinyl tiles on the floors in all classrooms.

Only the staff room and grade 7 have vinyl floor tiles, all other classrooms have cracked, cement floors which are icy-cold in the winter, and hazardous throughout.

I’d like your help to raise $5,000 and get the work completed by November 30th, 2016, before the Christmas holidays.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO MY PROJECT IN LESOTHO

(Scroll Down Until You Reach S. Marsh)

All donations are sent through the Peace Corps and are

TAX DEDUCTIBLE DONATION

PLEASE SHARE WITH OTHERS WHO MAY BE INTERESTED IN HELPING.

The children, teachers, community (AND ME) are all extremely grateful to you for helping us make the school a better place.

I shall post updates and photos once we receive the funds, and start the 3 phases of the project.

You can also follow our progress on my FaceBook if you’d like.

THANK YOU SO MUCH.

Sonia

The post Please Help Me Raise $5,000 to Make My School Safe appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

January 31, 2016

HIV/AIDS Orphans: Interview With Prince Harry’s Sentebale Staff

Sekoate from Sentebale, Prince Harry’s charity. I love his T–shirt.

There is a beautiful clinic in my village in Lesotho, Africa, funded by the U.S. Millenium Challenge Corporation.

As you may have read in a previous blog post, I visited it a few weeks ago, and discovered that once a month, Sentebale, the charity Prince Harry and Prince Seeiso of Lesotho started, runs a workshop for children and orphans with HIV/AIDS at the clinic. Sentebale means “Forget-me-not,” in Sesotho.

As I approach the clinic, I hear children singing in the main building. The door is open and I peek into the workshop room and notice two women talking to a large group of adults. One woman takes my hand and whisks me away from the room. I explain why I’m here. She then leads me to a white truck parked inside the property, where I find a man asleep in the front seat. His foot is bandaged and he says he cannot walk, but is willing to be interviewed from his car.

Sekoati is his name, and he tells me he is the program coordinator for Sentebale, responsible for the monitoring and evaluation of the children’s adherence to medication.

Sentebale partners with clinics around Lesotho and forms clubs for HIV/AIDS children aged 9-18. They offer several programs, including one specifically for the herd boys who attend a nighttime program, since they tend to the cattle and sheep during the day. (More on the life of the herd boys after I finish reading an interesting book written by a herd boy.)

The program Sekoati is responsible for is called the Mamohate program; the name given to the new children’s center in Thaba Bosiu, inaugurated by Prince Harry on November 26th, 2015. This center provides emotional and psychological support to children affected by HIV/AIDS.

Once a month, clinics around Lesotho run these clubs to distribute free ARVs, (antiretrovirals) to the children. They make it a fun day of games and offer snacks and food. They also reimburse transportation for the orphans, as some have to walk 2-3 hours to reach the clinic.

“What are your main challenges?” I ask Sekoati.

“The record keeping of how children are taking their medication. It’s very challenging to monitor their CD4 count, which we do twice a year. The blood is sent to a local hospital, but the machine is often broken, and we don’t get the results back.”

He tells me that many clinics don’t understand the benefits of the clubs, so they don’t support them.

“What about the adults I saw in the workshop?” I ask.

“Those are the caregivers. They meet four times a year, and they don’t always give the necessary support to the child.”

“What do you mean?” I ask.

He explains that many orphans have behavioral problems, and are violent, troubled kids. The caregivers don’t know how to handle the behavioral issues, and the children are stigmatized; caregivers often use scare tactics with the children.

I ask Sekoati whether they teach the children sex education and condom use. He said in general, “No,” as this is a cultural/religious issue, “but things are changing.”

I mention what I’ve heard from many Basotho young women, including one expert on sexual harassment in schools and universities. Many girls have sex without protection in exchange for money or gifts. I wonder how can we make a difference in reducing HIV/AIDS in Lesotho when there is extreme poverty, starvation, as well as religious and cultural issues about not using condoms.

Young women tell me that in some (many?) primary schools, 7th grade girls will fail their exams if they refuse to have sex with their teachers. One woman I interviewed who is passionate about this topic, and is devoting her time and money to making a difference, told me that sexual harassment happens at universities and in some cases, if the young women talk about this, their teacher will flunk them, and they won’t be allowed to pursue their studies.

I am learning so much and want to help the orphans at my school. Please read next week’s post on what I hope to do in my community to help the orphans.

The post HIV/AIDS Orphans: Interview With Prince Harry’s Sentebale Staff appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

January 20, 2016

I Have No Privacy

My latrine and where I burn my trash

When you live in a rural village in Lesotho, southern Africa, you soon realize that everyone knows your business, and that you have no privacy.

In the morning, I peek out my door to see if there are any bo-‘m’e, bo-ntate or bana (women, men or kids) sitting on Mary’s (my host mother) porch, chatting, singing or shouting, as that’s how most people communicate in my village. Mary’s radio is tuned in to her favorite religious station, and I have no idea how her visitors can hear one another speak. Many people stop by for a chit-chat, and sometimes I see a stranger, leaning against the bricks in her yard, scanning daily life in the neighborhood.

When I think the road is clear, I dash out with my pee bucket and make sure it’s on my left side when I pass Mary’s porch, as I don’t want Mary to see how full it is. I’m scared the village will gossip about how much I pee during the night, even though I dump bleach and dirty dishwater into my pee bucket to rinse it out.

Oh dear, a woman is walking towards me. Now I have to greet her. Greeting people is important to the Basotho culture; they are insulted if you don’t stop and ask them,

“How did you sleep last night?”

“Very well thank you, and you?”

“Oh, I slept harmoniously well (hamonate) thank you,”

“Thank you ‘M’e.”

All this conversation with my pee bucket in hand, trying to hide it while smiling, is something I don’t think I can get used to.

View to the right of my latrine and where I burn my trash

My latrine is 50 metres from my rondavel, and faces the main road. People know exactly when I enter, and when I exit my latrine. I have a lock on my latrine’s metal door which makes a hammering sound whenever I unlatch it. Even the horse turns his head to look at me when I use it. For some reason I haven’t seen any Basotho use their latrines in my village. Am I the only one who needs to pee? My ‘M’e even asked me one day if I had a (mathata) problem, because I visited my latrine twice in one morning.

When I walk around my village, I see kids run to the side of the road and pull down their pants and squat. I’ve even seen men, including my taxi driver, stop the car and pee on the side of the road.

People know everything about me in my village. Even my ‘M’e said, “I know you drink a lot of coffee.” How does she know? Perhaps from the wet coffee filters full of ground coffee that I throw in the trash, or the fact that I use my latrine. They also know I drink red wine, as they see the empty box when I burn my trash.

I hate burning my trash as I’m worried that I’ll start a brush fire, and I’m concerned about breathing the toxic fumes from burning plastic bags, containers and metal cans. I tear my grocery and bank receipts into tiny pieces before burning them. I know children, and sometimes adults go through my trash, as they collect items they can use.

When I received my package from the U.S., everything was wrapped in cardboard and beautiful packaging. The kids love to keep boxes, tissue paper, yoghurt containers, empty wine boxes, and create dollhouses, and make “pretend” beds and furniture out of anything they find in the trash.

When Karabelo, Mary’s eleven-year-old granddaughter, showed me where and how to burn my trash for the first time, she squatted next to the flames. With her bare hands, she removed objects that she wanted to keep. The tips of her toes were less than an inch from the flames, but this did not bother her.

Teaching Karabelo how to use my laptop

My rondavel

People want to come inside my rondavel. I have a laptop, books, an exercise ball and a nice duvet cover with pillows. My host mother warned me not to let anyone inside, except for her, and her granddaughter, because once I allow one person inside, the whole village will stop by to “see” what I have in my room.

I guess I have to redefine privacy, and realize that it will be non-existent for the next two years I’m serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Lesotho.

If you enjoy my posts, you can sign up to receive my updates here.

The post I Have No Privacy appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.

January 11, 2016

Integrating into My Rural Village in Lesotho

The American built clinic in a rural village in Lesotho, southern Africa

Visiting my local clinic is an important part of integrating into my community as a Peace Corps volunteer. I live in a rural part of Lesotho, a small landlocked country in southern Africa.

I want to find out whether rural clinics are providing ARV’s (Antiretroviral) medication to HIV patients in my area, and if they teach sex education and condom use in schools. Peace Corps informed us that 30% of girls between 20-24, have HIV in Maseru, the capital of Lesotho, and 23% of the total population has HIV/AIDS, which makes Lesotho the country with the second highest prevalence rate in the world.

Road to the clinic

My host mother, ‘M’e, and I walk along the two kilometer stretch of dirt road to the clinic; the one I visited on a previous weekend, and discovered it was closed. (Apparently it’s only open on weekdays.)

The clinic is super modern, built three years ago, with U.S. funds. The waiting room has metal chairs arranged in airport-style seating, and I asked ‘M’e how does the staff know the order of the patients arriving, since there is no check-in system. “They just do,” she replied.

A flat screen TV with a Basotho soap, entertains the patients. They are laughing and chatting away and I feel like I’m inside someone’s house, waiting for the popcorn to be passed around.

‘M’e introduces me to the head nurse, and all of a sudden, I get the VIP treatment. I walk past all the patients, and follow nurse to her office. There another nurse is talking to a patient.

I feel uncomfortable knowing that twenty or so patients are sitting in the waiting room, and these two nurses are allowing me to ask them questions about the clinic.

In the three months I’ve been in Lesotho, I realize the importance of forming relationships, so I ask the nurses if they have children, and let them talk about themselves first, before interviewing them about their work.

The younger nurse is six-months pregnant and is sitting on the edge of the desk, holding a blood pressure cuff. I joke around and ask her to take my blood pressure.

“The batteries are dead and we don’t have other batteries,” she says.

“Do you have a manual one?” I ask, demonstrating the pumping action with my hand.

“No.”

I know ‘M’e came along to get her blood pressure checked so they could give her medicine, so I’m concerned for her.

Peace Corps informed us that local clinics are supposed to send nurses to schools to talk to the children about HIV/AIDS, several times a year, and these nurses told me they had only been out once last year, for three hours, to my assigned school. They taught sexual reproduction health and HIV/AIDS to grades 4 through 7.

“We do not do condom demonstrations because we are Christian,” the nurse said, “We encourage children to come for voluntary HIV testing at the clinic. They have to come with their mother,” she continued.

I was happy to see the shelves fully stocked with ARVs, and other medications which are delivered monthly through NDSO (National Drug Service Organization,) according to what I was i

My ‘M’e sticks her head through the door and says, “People are waiting.”

I feel guilty taking up so much time.

“They wouldn’t let me go,” I said in the hallway.

She returns to watch the soap, and arranges for the cleaning lady/pharmacist, yes, they wear many hats in this clinic, to show me around.

She takes me on a tour of all the buildings, and I’m in shock. There is a delivery room with a baby monitor, and apparently only 7 babies have been delivered there since the clinic opened, three years prior.

There is also a room with a fridge and gas stove, all equipped with brand new cooking pots, and this room has never been used, and when I ask her why? she says, “There aren’t enough nurses to take care of the women who are waiting to deliver their babies.” There is a ward with eight brand new beds, which is not being used. Another building has a shower, a toilet and a sink, and the floor shows signs of a previous leak, so I ask if they have running water, and she says, “No, because of the leaking toilet.”

large maternity ward

New kitchen for moms, never used.

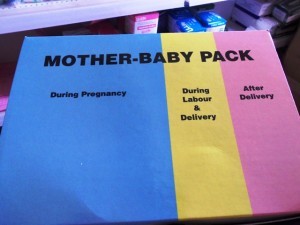

Mother-baby packs available, but not sure if they are given away

A nice workshop room at the center

Seating in the workshop room

I am happy to see that ARVs, and being given to patients with HIV, but due to a lack of government funding, there is a shortage of nurses. This is what I was told.

The post Integrating into My Rural Village in Lesotho appeared first on Sonia Marsh - Gutsy Living.