Alison Mercer's Blog, page 5

January 1, 2014

After I Left You becomes Und dann, eines Tages

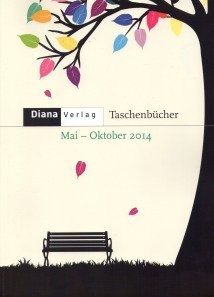

Diana Verlag catalogue with Und dann, eines Tages on the cover

Happy New Year everybody!

Just before Christmas I got a fantastic treat in the post: the May to October 2014 catalogue from my German publishers, Diana Verlag. Their edition of my next novel, After I Left You, is on the cover and looking beautiful on a double-page spread inside.

The German edition of After I Left You comes out in summer 2014, and it’s called Und dann, eines Tages. I love the cover design they’ve come up with – it refers to a specific scene in the book, as you’ll see when you get to it, but you don’t need to know this to pick up what the image suggests.

Once upon a time someone – perhaps several someones, friends or lovers – sat on that bench underneath that beautiful tree. Who were they, what happened to them, and where did they go?

All about Und dann, eines Tages in the Diana Verlag catalogue

The catalogue describes the novel as ‘about first love and the years that follow’. The story opens with Anna sheltering from the rain in a London bookshop and bumping into Victor, her first love from her university days. She hasn’t seen him for seventeen years. This chance encounter is destined to change Anna’s life, but first both of them will have to face up to the secrets of her past.

Other writers have made some lovely comments about the novel. Alice Peterson, author of Monday to Friday Man (which knocked Fifty Shades of Grey off the Kindle no 1 spot!) had this to say about it: ‘A lovely absorbing read, so evocative of student life. Alison Mercer really captures the passion of falling in love for the first time.’ Tamar Cohen, author of The Mistress’s Revenge, said, ‘Alison Mercer has expertly spun an engrossing story about love, secrets and second chances.’

I am so pleased that the novel is being translated for German readers, and I really hope they will love it.

I’ve just been on a hunt through some old photographs to find a snap from a trip I made to Berlin back in 2000 – here it is!

In Berlin back in 2000

I thought it was a wonderful city, full of energy and busily rebuilding itself. It was also very friendly, and there were plenty of quirky little bars – I’m in one of them in this picture.

At that time, there was a huge amount of construction and renovation work going on in Berlin – you’d walk along a row of houses and one would be awaiting restoration, the next would be covered in scaffolding and the third would be gleaming and good as new. There was very little evidence of when you were passing into the former East Berlin, apart from the bright pink overhead pipes that were used to carry cables, and, as I remember, the flat cap and pipe sported by the little green man on the pedestrian crossing signs.

I don’t know anything much about architecture, but I remember the Reichstag building as one of the most beautiful and impressive I’ve ever visited – there’s something very powerful about being able to look down and see politicians toiling away underneath your feet! You can see a video of it here.

The visit made me wish that I’d found some way to live in Berlin in the late 90s, and spent a little less time in London! I very much hope to visit Germany again one day.

Check out Diana Verlag’s website

Diana Verlag’s catalogue with Und dann, eines Tages on the cover

Early reviews of After I Left You: responses to proof copies on Goodreads

My blog posts about After I Left You

December 6, 2013

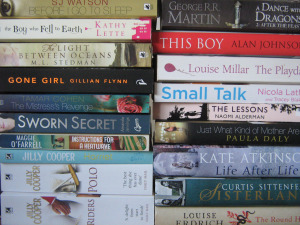

My year of reading: favourite books of 2013

My year in reading: favourite books of 2013

Revenge, injustice, unreliable narrators, psychic powers, power in hands that are good or bad or hapless or downright sadistic; not being able to remember how you got where you are, not being able to find a man because none of them can cope with your son, and having the chance to live your life over and over again. My 2013 has been filled with good books, and as it’s the season of lists and round-ups, I thought I’d return to some of them here.

This isn’t an exhaustive or particularly scientific list and I’m sure that as soon as I’m done I’ll be troubled by what I’ve left out, but over the past year these books have kept me gripped, made me smile, taken me out of myself, shown me the world as I never thought to see it before, and kept me up turning the pages because I just have to see what happens next…

The Light Between Oceans by M L Stedman. Oh! What a weepie. Beautiful, lyrical, elemental, epic. I believe it’s being filmed. A thing of beauty with a small and much-beloved child at its heart.

The Mistress’s Revenge by Tamar Cohen. This was the year I was introduced to the concept of ‘domestic gothic’, which I guess you could argue this and the next four books belong to. Home life isn’t all cupcakes and Mr Right; in this twisty tale of a woman scorned, it’s all about Mr Wrong. Darkly funny, acidic and obsessive, and one for anybody who’s ever been bitter or angry about the end of a relationship.

The Playdate by Louise Millar. How well do you really know your friends and neighbours? A paranoid glimpse of what can happen if those close to you aren’t as benign as you assume. The central character is a single mum trying to get back to work, with a really infuriating ex and a vulnerable child. If you’ve ever had to run to make the pick-up, you’ll find plenty here that’s familiar as well as a few of your worst fears.

Just What Kind of Mother Are You? by Paula Daly. So your friend’s child was meant to come to yours for a sleepover… and you forgot, and now she has disappeared. An edgy drama with a heroine who is warm but not always wise, played out against the backdrop of a small community in Cumbria. Expect some jaw-dropping surprises – including a startlingly excruciating dinner party scene – and plenty of menace.

Sworn Secret by Amanda Jennings. A dead teenage girl had a secret – and uncovering it will take her grieving family to the edge in this intense and suspenseful tale of the aftermath of loss. The vulnerability of adolescence is in the spotlight as her sister discovers love for the first time and struggles to make sense of the past. Who can she really trust, and who knows more than they are telling? The family’s ordeal is far from over, and as long as the truth is in doubt, it can’t be the right time to let go.

Before I Go to Sleep by S J Watson. The heroine looks in the mirror and sees a middle-aged woman; where did all those years go? She can’t remember, because she forgets each day as soon as she sleeps… unless she writes it down. Can she trust the husband who seems to care for her so patiently? Includes one of the most unsettling sex scenes I’ve ever read.

Outside Mostly Books in Abingdon. Books Are My Bag!

This Boy by Alan Johnson. I’m not one for political autobiographies – but this isn’t at all the kind of book you would expect a politician to write. It’s really a story about women – in particular a mother struggling in a rotten marriage, doing her best to survive, and her resourceful teenage daughter, who later manages to keep herself and her brother out of care. It’s a tribute to women’s staunchness and resilience in the face of the odds, and a glimpse of a London of another time.

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. She is such a good writer. This is one that will keep you on your toes – and up late. The prose is lucid, the people are opaque, and there is no predicting what may be revealed next.

Sisterland by Curtis Sittenfeld. Twin psychics with very different attitudes to their shared gift. When there are intimations of an earthquake, are they right? A deliciously observed character study of two very different women who just can’t escape their interconnected fates (but can anyone?)

The Round House by Louise Erdrich. A brilliant study of the aftermath of a brutal crime on a Native American reservation, exploring what happens when justice loses its way on the border between cultures. Evocative and beautifully written.

The Boy Who Fell to Earth by Kathy Lette. Hats off to Kathy Lette for writing a funny, romantic, truthful novel about a single mum who is looking for love, struggling with an awful ex and trying to do her best for her son, who has autism and can’t help but tell her suitors what she really thinks of them.

Anything by George R R Martin. You know nothing, Jon Snow… I’m down to the last couple of hundred pages of the most recent book in the series. I’ll be bereft when I’ve finished. A monumental (and sometimes brutally gory) work of fiction, with a terrific cast of characters. A fully realised world that has plenty of parallels in the history and geography of our own.

The Lessons by Naomi Alderman. Begins with a louty food fight, but will it end with redemption? They say you should keep your friends close and your enemies closer, but sometimes it’s hard to tell them apart. An Oxford novel that definitely does not romanticise the dreaming spires.

Harriet by Jilly Cooper. My editor suggested I read this when I was working on After I Left You. It starts with an Oxford student whose randy tutor gets her to write an essay on which Shakespeare character would be best in bed. (You’d want to give Hamlet a miss, but Mercutio would be fun for a fling, or perhaps Benedict for a keeper?) After that I read Riders and Polo in quick succession. Robust, naughty fun.

Instructions for a Heatwave by Maggie O’Farrell. Sensuous and sensitive character study of an unravelled family drawn back together by a mysterious disappearance, against a background of simmering heat.

Small Talk by Nicola Lathey and Tracey Blake. Nicola is a brilliant speech therapist who has done lots of great work with my son, who has autism. This is a practical guide on how to help children learn how to communicate. A really useful parenting book, with expert tips presented in a friendly, accessible way.

The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida, with an introduction by David Mitchell. Just beautiful. The world seen through the eyes of a boy with autism and translated back to us. Listen: ‘Although people with autism look like other people physically, we are in fact very different in many ways. We are more like travellers from the distant, distant past. And if, by our being here, we could help the people of the world remember what truly matters for the Earth, that would give us a quiet pleasure.’

The Reason I Jump

Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life. Deserves to be showered with prizes. Elusive, stark, sharply observed, compelling tale of life, death and chances that are never quite missed, and keep coming around again.

So – what am I looking forward to in 2014? Well – by and by I will read Charlotte Mendelson’s Almost English, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Donal Ryan’s The Spinning Heart, Nina Stibbe’s Love, Nina, Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs and Susie Steiner’s Homecoming. I’m also looking forward to Alison Jameson’s Little Beauty, Sarra Manning’s It Felt Like a Kiss, The Best Thing That Never Happened To Me by Jimmy Rice and Laura Tait, In Her Shadow by Louise Douglas, Julie Cohen’s Dear Thing and Tamar Cohen’s The War of the Wives. And I have to read Me Before You by Jojo Moyes; I bought it as a present for someone and after she’d read it she went straight off to the library to hunt for more.

Plus my friend Neel Mukherjee has a new book out in the spring, The Lives of Others, which I know is going to be brilliant. Here is the cover. Gorgeous!

The Lives of Others, by Neel Mukherjee

November 22, 2013

Benjamin Britten and three lessons in creativity

Benjamin Britten’s music makes me think of countryside and childhood

A cold clear blue-sky day in Oxford, children from primary schools across the county singing, young and old in the audience, everybody drawn together by the music. I went to see my 10-year-old daughter and her school choir at the Sheldonian today, taking part in a ‘Friday Afternoons’ concert to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Benjamin Britten – and it was fantastic!

It was also a chance to hear Professor Robert Saxton, who is professor of composition and tutorial fellow in music at Worcester College, answering questions from the schoolchildren about Benjamin Britten, who taught him. Was Benjamin Britten a grumpy teacher? Well – a bit sharp sometimes, if people weren’t up to scratch or weren’t being efficient; but he was also very generous and very kind.

Dr John Traill, the conductor, passed on the children’s questions during an interview with Professor Saxton before the choirs embarked on the Friday Afternoons songs. Professor Saxton was also asked for tips for composers, and described three important lessons he had learned from his own teachers – including Benjamin Britten. His advice struck me as being relevant to pretty much any creative work, including writing, so here it is, paraphrased:

Think of the whole when you are working on the part. If you’re composing a line of music, have the impact you want the whole of the composition to make in mind.

Make it real. Get other people involved. Being able to record something and play it back via computer isn’t the same as letting other people loose on it to see if it works. (I suppose this is like the scary but essential part when you give your writing to readers.)

Work very hard! However great your ambitions for what you hope to achieve, none of it will be possible without working away on your technical skills.

It was amazing to hear the children singing songs I remember from my time in the South Berkshire Music Centre junior choir thirty years ago. You can’t beat a truly thundering finish with Old Abram Brown.

Happy St Cecilia’s Day everyone!

November 8, 2013

The Brixton bomb and Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life

I was on my way towards the centre of Brixton when the bomb went off. At first I had no idea what it was. I have no recollection of hearing an explosion. What I remember is the helicopter that almost immediately appeared above the rooftops of Brixton Road. It was early evening and the sky was tinged with red; the helicopter whirred and hovered, watching, waiting. It looked apocalyptic. It looked like a scene from a war film, and therefore it was also weirdly familiar, like a déjà vu, and I carried on walking towards it.

When the bomb went off I was just approaching the junction with Coldharbour Lane. I was on my way to Brixton Rec for a swim; my route ran right through the blast, and if I’d been a few minutes earlier, I would almost certainly have crossed over and walked into it.

But by the time I approached the carnage there was already glass scattered all across the pavement. I think I remember a double-decker that had ground to a halt, its windows blown out. It’s always a busy thoroughfare, but the traffic had come to a standstill and many people on my side of the road were standing and looking around, dazed and uncertain.

I still didn’t understand what had happened. I thought perhaps a gas explosion? It didn’t occur to me that this might have been deliberate. This was before 9/11, before 7/7; more longstanding Londoners would have remembered IRA attacks, but I did not. This was 1999, and my experience of the city had been peaceful.

When I looked across to the opposite side of the road I was horrified to glimpse someone lying on the pavement, clearly seriously injured, being attended to by somebody else. A man sprinted past me, heading away from the destruction back towards Brixton Hill, where I had come from. He shouted out that it had been a bomb, that we were fools, that we should all get away. For a moment I thought this was farfetched. Then I realised it was not. It seemed to have taken a very long time (though it was probably mere minutes) but the emergency services began to cordon the area off. Somebody was in charge again.

I turned round and began to retrace my steps, heading back towards home. All the way along Brixton Hill people were coming out of shops and cafés, asking what had happened, telling what they knew. Numbers of the injured were mentioned. People were shocked, disbelieving, matter-of-fact. I have never in my life been in any other situation in which every single stranger around me was talking so intently and so urgently about the same thing.

Back home, I turned on the news. The terrible details of the suffering that had been inflicted became clearer, and I began to realise what I had escaped. Later I went out and got good and drunk at my friends’ house round the corner, and I think lots of others did the same; I heard that there was a mood of bravado in the clubs and pubs of Brixton that night.

Sometime in the next few days I saw an image from that evening that has stayed with me, as it must have done for many: the x-ray of the head of a 23-month-old baby injured in the blast. A nail from the bomb had penetrated the child’s skull, lodging in the brain.

I thought of the Brixton bomb when I read Kate Atkinson’s excellent novel Life After Life earlier this year. The heroine experiences her life over and over again, cut short by different combinations of incident and coincidence and reaction. It’s a salutary reminder of how close we often come to danger, and how much of the time we may not even be aware of what we have escaped.

Life After Life made me think of another experience too − not my own, one that was related to me by a friend. One night this friend was out driving with his girlfriend somewhere rural in the US; they came to a level crossing that had no barriers, and only just managed to stop before a train thundered past.

After the train had gone and everything was still and quiet again one of them turned to the other and said, ‘Did you feel that?’ – meaning, did you feel that near-miss, near-impact, that sudden, terrifying proximity to disaster? It was shared between them as intensely as a secret, almost impossible to convey to anyone who hadn’t been sitting in the car at that particular time and place.

This is what Life After Life does. It is a history-melding litany of deaths and rebirths. The heroine goes under time and time again, slipping into darkness, but she always comes back, and the next time it is a little different and there is another ending, and another beginning.

Peril is never far away, but then, that’s how it is for us, too. We are so often just a hair’s breadth from the end; sometimes, we can feel it.

Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life

August 22, 2013

The cover of After I Left You

The cover of After I Left You

Here it is – the cover of my new book, After I Left You, due out in Jan 2014 from Black Swan.

I’ve posted it on Twitter and Facebook and have had a really lovely response – even the chaps seem to like it! I appreciate this so much, as this is a peculiarly, irrationally nerve-racking moment. It’s the tipping point at which the book begins to shift definitively from being mine − something that sits quietly on my computer − to being yours (I hope), in your hands. It’s not quite the top of the helter-skelter ride that is publication; that will come in January next year – but it’s well on the way up.

Lisa Horton, the designer, has put a lot of thought and ingenuity into this cover. You can see Oxford in the background, and that’s perfect because that’s where a lot of the story is set, and where the lovers met back in the day. And you can see straight away that all hasn’t turned out blissfully well for these two – well, for most university couples it doesn’t, does it? But who knows, maybe that could change…

I really love the torn photo in this design. It makes me think of a box I have tucked away that has various bits and pieces of memorabilia in it: 20-year-old letters, postcards, and yes, a few photos. I have a hunch that most women have an equivalent to that box somewhere. (Men too?) I don’t look in it, but I know it’s there, like a time capsule.

(The box that Tina uses for Justin’s letters in Stop the Clock is the same kind of thing, but doesn’t quite manage to stay out of sight – I won’t say any more about that though, in case you haven’t read it. Spoilers are BAD, as my husband recently reminded me when I dropped a clanger about Game of Thrones.)

Here’s the copy my editor at Transworld, Harriet Bourton, has written to introduce After I Left You:

Every broken heart has a history

Anna hasn’t been back to Oxford since her last summer at university, seventeen years ago. She tries not to think about her time there, or the tightly knit group of friends she once thought would be hers forever. She has almost forgotten the sting of betrayal, the heartache, the secret she carries around with her, the last night she spent with them all.

Then a chance meeting on a rainy day in London brings her past tumbling back into her present, and Anna is faced with the memories of that summer and the people she left behind. As Anna realises that the events of their past have shaped the people they’ve all become, hope begins to blossom for what her future could hold…

An absorbing, powerful novel of love and friendship that will sweep you away

from the very first page.

Praise for Alison Mercer’s debut novel, Stop the Clock

‘This is grown-up chick-lit at its very best’ Closer

‘Funny and moving, this is a fab debut’ new!

‘Mercer has a satirical eye which she puts to good effect . . . A funny, promising debut’ Daily Mail

After I Left You is available for pre-order from the publisher, Transworld.

More about After I Left You

After I Left You: the story of my second novel

Five rules for writing an Oxford novel

Stories of love and love gone wrong: After I Left You and romance second time round

July 28, 2013

Curtis Sittenfeld’s Sisterland and the writer as psychic

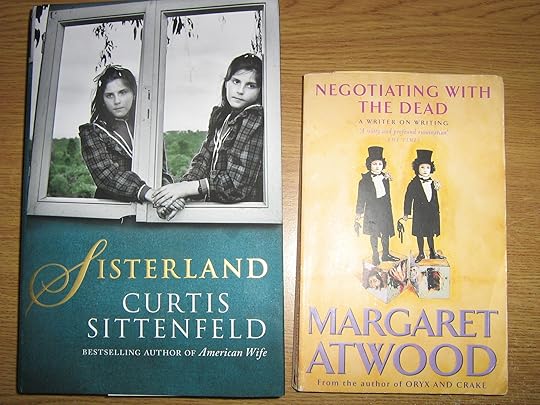

On my desk right now: Sisterland and Negotiating with the Dead

I got into Curtis Sittenfeld because of the cover of American Wife, which featured a nostalgic photograph of a hopeful woman in a skirt, on a bike, against a backdrop of some arable crop – it could be corn, or maybe wheat – and sky. It made me think of Dorothy in Kansas, but all grown up and without the gaudy technicolour magic. I kept seeing that picture in the supermarket until I bought the book.

After that I read Curtis Sittenfeld’s first and second novels, and then I was left waiting for her next, which turned out to be Sisterland, which the postman handed over to me last week, as part of a parcel of books from my publisher. (Thank you Harriet.) I finished Sisterland last night and, as I expected, I loved it.

Like Curtis Sittenfeld’s other books, Sisterland is ostensibly about a story about a unique, even bizarre, situation but also, as if by sleight of hand – or, perhaps, in the shadowy room for manoeuvre created by a really strong hook – deals with something else. So American Wife answers the question, What is it like to be married to the President? And: What kind of woman ends up married to the President? But at the same time it tackles a number of other questions, which I can’t explicitly reveal without spoiling the book for you if you haven’t read it (in which case, get thee hence and tuck in), but which can be summarised as: what if you make a life-wrecking mistake when you are young? Can you recover, and if you do, will it still catch up with you anyway?

In Sisterland, the overt question – the narrative hook – is this: a psychic predicts a major earthquake. Is she right? Is it possible to accurately predict the future? But underlying that – at least, the way I read it – is another dilemma, and this is a much more universal one: is it possible to be feminine, a wife and mother, and also to use your gifts and be free? And if you have a gift and decide not to use it, what happens to you then?

Slippery doubles, twinship and writing

Sisterland sent me back to one of my favourite books about writing, Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead, which talks at some length about the use of doubles in fiction, and why writers are so preoccupied by them. (Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin is largely about a fraught relationship between sisters – and Curtis Sittenfeld’s The Man of my Dreams also explores this. But to take it further, to make the sisters twins and psychic to boot, makes it ever more apparent that you are dealing with two mutations of one self.)

There’s a passage in Negotiating with the Dead where Margaret Atwood draws a distinction between ‘the person who exists when no writing is going forward – the one who walks the dog, eats bran for regularity, takes the car in to be washed, and so forth – and that other, more shadowy and altogether more equivocal personage who shares the same body, and who, when no one is looking, takes it over and uses it to commit the actual writing.’

She goes on to say, ‘I am after all a writer, so it would follow as the day the night that I must have a slippery double – or at best a mildly dysfunctional one – stashed away somewhere. I’ve read more than one review of books with our joint surname on them that would go far toward suggesting that this other person – the one credited with authorship – is certainly not me. She could never be imagined – for instance – turning out a nicely browned loaf of oatmeal-and-molasses bread, whereas I . . . but that’s another story.’

The twins, or slippery doubles, in Sisterland are Daisy and Violet Schramm, except when Daisy leaves home she decides she wants to distance herself from Violet (and, by implication, from her true self), and changes her name. Marriage helps, and when we meet her, at the beginning of the novel, she has become the altogether less distinctive Kate Tucker, who, as Vi points out, sounds like a Puritan.

Kate/Daisy begins to move away from Vi as an adolescent because they put on a show together and she plays the feminine role, and is afterwards praised for her prettiness. Popularity and acceptability beckon. She doesn’t want to be weird, and she certainly doesn’t want to be like Vi, one of whose gifts is a robust indifference to what other people think. (Also, Vi is overweight, whereas Kate/Daisy is meticulous about hitting the Stairmaster.)

And so Kate/Daisy ends up as a full-time wife and mother who has done her best to abandon her psychic abilities (but has she managed to destroy them entirely? Not quite, as you’ll see – gifts have a way of passing themselves on), a woman who is dangerously flattered, at a crucial point in the novel, when someone tells her how pretty and nice she is. Meanwhile Vi lurches towards celebrity, or notoriety, with her very public earthquake prediction – much to Kate’s embarrassment and fear.

It turns out that writing about psychics is a neat way to allude to the business of writing itself. Writers intuit what might happen to characters as the story goes on, though they don’t know for sure until it happens – and Kate and Vi are in much the same awkward and uncertain position. It made me smile when Vi, having achieved some success as a psychic (though, as it turns out, only with Kate/Daisy’s help), is able to make a living out of her gift, having previously struggled along as a waitress; some of the members of her old meditation group, who have not been quite so lucky commercially, are rather jealous of her. (I was wondering if something similar might happen if one member of a writing group found herself in a position to make the writing pay for itself.)

The art of making it real

Sisterland is unsettling, and creepy and funny and melancholy, and pulls off the coup of being both startling and believable. When I read, I want to be introduced to a new world and recognise it as true, while at the same time knowing that I’m being shown people and places that I’ve never seen before; Curtis Sittenfeld has the requisite twin gifts of truthfulness and originality in abundance, which is why she is one of my favourite discoveries of recent years.

Within the first few pages of American Wife I realised I’d found a new writer that I really liked, which is one of the great pleasures of reading. The best consolation for coming to the end of a book you love is knowing that there are others by the same author that you can go on to; and reading a number of different books by the same writer helps to confirm your sense of what is unique about them, and what attracted you to them in the first place.

It’s like getting to know someone by seeing them over time, dealing with different situations and environments; you can satisfy your curiosity about what this person has done in the past, and if the writer is still going strong, you’ll be eager to find out where they’re going next.

For me, and I suspect for most of us, this doesn’t happen all that often – this finding a book you really like, and chasing up the writer’s backlist. Back in the 1990s, it was William Gibson (starting with Neuromancer ), Margaret Atwood (The Blind Assassin), Raymond Carver (the collected short stories), James Ellroy (LA Confidential), Jean Rhys (Wide Sargasso Sea), Jayne Anne Phillips (Fast Lanes), and Joyce Carol Oates (Blonde). Those are all terrific books, and if you haven’t read them, I urge you to at least look them up – maybe you’ll get hooked on those writers the way I did.

More recently, there’s been Claire Messud (The Emperors’ Children), George R R Martin (Game of Thrones) and, of course, Curtis Sittenfeld. I guess you might deduce from this list that, on the whole, I love genre fiction and women’s fiction (or rather, fiction by and largely about women), and my heart is unstirred by much else, and you’d probably be about right. Why exactly it should be so I don’t know. What exactly it is that gets me hooked I don’t know. Sympathy for the underdog might be part of it, but only part; I suspect I also respond to writers who let their underdogs bite back.

July 24, 2013

Three women in the Thames: swimming for Ambitious about Autism

I’m in the middle! About to swim with my friends

Not surprisingly, we hesitated at the water’s edge. Sure, there had been a heatwave, and the Thames was likely to be rather less freezing than it might usually be. But it did look somewhat murky, and we’d committed ourselves to swimming a mile of it. Downstream, sure, but all the same…

It was all a bit Calendar Girls. There we were, three women on the more experienced side of 40, having just taken up a range of increasingly silly poses for the photographer from the local newspaper. We were sporting a selection of vintage swimhats that were beyond absurd: heaven only knows where my friend had got them from, or why she should have a collection of such things.

All this was in a good cause: we’d planned our mile-long river swim to raise funds for the national charity for children and young people with autism, Ambitious about Autism. And it was a cause close to my heart, as my six-year-old son has autism.

As we stood together looking down at the Thames, we knew there was nothing for it but for to get in or to admit defeat and go home. And there was no way we were going to do that. Our friends, family and colleagues had already supported us to the tune of around £700. (If you’d like to sponsor us too, that would be just brilliant – here’s our JustGiving page – it’s still open.)

We’d shed our charity t-shirts. Standing on the little jetty in our swimming costumes, we were fast approaching the moment of no return.

Our eyes met. I don’t know who said, ‘Oh come on, let’s get in and get it over with,’ but somebody did. And then we were in.

We posed for a few more photos, and then we were off.

I’d taken my swimhat off by this point. Too tight!

Three women in the river, chatting all the way

I’d originally been absolutely adamant that I was NOT GOING TO TALK. When I’m in my local swimming pool I get a little frustrated with those ladies who swim along double file, talking all the way. Swim! Chat later! I find myself thinking. And anyway, talking might have increased the chance that some of that Thames water – supposedly better than it used to be, but still, not exactly pure – could end up in my mouth, and then ultimately in my stomach, with potentially unpleasant results.

Did I stick to that? Did I heck. After the first few strokes, I heard my friends, the two Helens, chatting away behind me, and of course I joined in. We chatted solidly the whole way. Apparently the acoustics were such that our riverbank supporters could hear every single word loud and clear, even when their view of us was obscured by foliage.

Just a note of caution – swimming in open water is potentially dangerous, and I’m not going to advocate it. As we all know water is always to be treated with great respect and wariness. I was nearly bowled out into the sea at Cornwall as a small child, and that is one of my formative memories – in fact, what I remember best of all is not being in the water, but having to wear a very odd assembly of everybody else’s too-big clothes on the way home, and no knickers.

One of my friends is an experienced river swimmer: she’d come up with the idea for our Thames dip and researched it. My river companions started thinking about our next challenge almost as soon as we’d finished this one! I’ve noticed that a theme that crops up from time to time in my fiction is the friendship that takes a cautious character out of the familiar and into adventure – that’s what happens to Anna in After I Left You (due out Jan 2014) when she goes to university. In art as in life!

Helen Rumbelow, me, Helen Sage. Check us out! Yeah!

The real challenge that day, however, was the one accomplished by my husband, Ian Pindar, who looked after our children on the river bank. We’d hesitated about whether to bring our son. It was an absolutely exceptional situation – would it confuse him? Would he run off? And yet we had talked to him about it and it was clear he wanted to be there.

And so he was. And I will always treasure the memory of seeing my husband and both my children all there together, smiling and waving at me as I looked up at them from the river.

Read my blog post on the moment I found out about my son’s autism

Read my blog post on After I Left You and the story behind the story

Arriving for the challenge, looking less nervous than I felt…

July 17, 2013

The moment I found out about my son’s autism

Tom pre-diagnosis, twirling flowers in his hands: we had no idea this repetitive play was a symptom of autism

I expect that for all parents of children with autism, there is a point at which you realise that life has changed, and it is never going to change back again. This is when you finally recognise that you are going to have to learn about something you do not understand, and you are also going to learn to live with it and love it, because that something is autism and (you now know) it is part of your child, and your family and so, indirectly, of you too…

At first, let’s face it, this is a shock. Acceptance, maybe a degree of illumination, comes later. But at that moment of recognition – this is no longer something remote that happens to other people, it is real and it has happened to you and will carry on happening – it is as if a fog has suddenly descended, and you can see no way out.

Because all you know is what everybody else knows – Rain Man, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time – and it seems that what you’ve just been given is Bad News, although at the same time life carries on from where you left off and, perhaps, what you’ve just been told makes sense of some hitherto unacknowledged aspects of what life was like before.

Here’s how I found out.

The warning rash

It started with a rash – a non-fading rash, the type you are told, as a parent, to be vigilant about and test with a glass pressed to the skin (if the spots fade, it is not ominous), the potential warning sign of meningitis.

My son Tom, three and a half years old, was ill, with a temperature, lying on the sofa at home. He was clearly unwell, but I thought it was one of those sudden fevers that young children get, that often pass as quickly as they came.

However, he wasn’t really capable of telling us clearly how he was feeling – his ability to express himself freely was very limited. He understood much more than he could say – we had learned to communicate with him by asking him questions he could answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to. He sometimes echoed other people’s speech, which could give the deceptive impression that his command of language was greater than it really was.

That day, there was no obvious sign that whatever he’d come down with was anything out of the ordinary… until I saw the rash. I only noticed it because I had taken his t-shirt off to help him stay cool. It was just three spots, which didn’t look too bad, but they didn’t fade. I knew at that point I needed to get him checked out, and quickly.

At paediatric A&E, the medics initially seemed fairly relaxed and hopeful that it would turn out to be nothing too serious; after all, Tom didn’t appear to be seriously ill. He was off his food and drink – not a good sign – but he certainly didn’t seem to be in pain.

The mood changed as soon as his blood test results came back. These indicated that he was fighting a very serious infection. The medics seemed slightly bemused by how a child who appeared to be nothing more than a bit under par could actually be in such a bad way.

The next day he was diagnosed as having a ruptured appendix. That was what had caused the rash – the infection had spread into his bloodstream. Once the cause of his illness had been established, he was booked in for surgery straight away. This was the NHS at its best – dealing with an emergency, saving a life.

It was the last op of the day, and it took a long time because they had to clean out Tom’s insides. My other half was back home, looking after our daughter; I sat by myself in an otherwise empty waiting room, reading Victoria Beckham’s autobiography, unable to do anything other than pass the time. Sometimes a book is exactly what you need, and at that point, that particular book was an effective distraction. I have retained a special soft spot for Posh Spice ever since.

When it was all done I saw Tom and met the surgeon. He looked shattered; I thought of the intense concentration it must have taken, to ensure that every last trace of infection was removed. And I was profoundly grateful, and relieved that it was all over.

Questions and answers

But then, a few days later, a paediatrician drew me aside. He said the nurses had made some observations about my Tom’s behaviour while he was on the ward recovering from the operation; did I have any concerns about it?

Certainly, we were worried about Tom’s delayed language development, and had already had some communication about this with health professionals, but I wasn’t quite sure what the doctor was getting at. Talking was clearly a problem, but on the whole, Tom was a placid, even passive child – so why the question about behaviour?

We were outside in the garden area; Tom was much better by this point, freed of the various tubes and wires he’d been attached to post-op, and was playing on a bike. It was reassuring to see him like that, the doctor said. I was offered an out-patient developmental assessment, which I gratefully agreed to. But still, something niggled… I knew there was a further question I had to ask.

It wasn’t until Tom was being discharged that I got up the nerve to ask about what exactly the nurses had observed. Repetitive behaviour, I was told: twiddling small objects in his hands. Oh yes, I said. He does that all the time. What could that mean, then?

The doctor said carefully, It could suggest an autism spectrum disorder.

And then I went home in a cab with Tom – my other half was taking our daughter to her swimming lesson. The weather was awful; it had been tipping it down. They were excited to notice a couple of rainbows, but I felt that I had been plunged into a world of black and white.

That evening I googled autism. And that was how I found out.

It made sense. It made me sad to read the statistics – the prospects for employment, the prevalence of bullying, and so on. And it still does. But over time, the sense of gloom I felt that night has receded. I think it was probably shock as much as anything. And fear: fear of the future. Fear of the unknown. Fear of other people, too, and what they might do.

I won’t say those fears were all groundless, but there was also so much to hope for and be grateful for: so many blessings to count. I’ve come to realise, since then, that the calmer and happier and more loving I can be, the better things tend to go. I know that sounds really obvious, but it’s harder in practice than in theory!

And so here we all are, with our much-loved boy, as lucky as anything. We’ve been helped along the way by some great people – not least the staff at Tom’s excellent school – and some brilliant charities:

Ambitious about Autism, which supports children and young people with autism and their families. In a few days’ time I’ll be taking part in a Thames river swim organised by a friend to raise funds for Ambitious about Autism – here’s our JustGiving page. I’ll let you know how we get on!

The National Autistic Society – I recently did an EarlyBird course with the National Autistic Society – this brings together parents and carers with staff from the child’s school to learn about autism and strategies that can help to give children the best possible chance to thrive.

I discovered the websites of both Ambitious about Autism and The National Autistic Society on that first evening when I started to try to find out about autism – they do a great job of raising awareness and providing information and support. Here are some more charities that have given us invaluable help:

Guideposts Trust – runs terrific holiday playschemes for children with disabilities. Tom absolutely loves going to his holiday club.

South and Vale Carers Centre – fantastic volunteers provide advice on filling in DLA (Disability Living Allowance) forms – which are pretty daunting, and very long.

More about autism from my blog

Aftermath of a scandal: Winterbourne View and my family’s fears

Parents of children with autism: so many differences, so much the same

June 24, 2013

The two types of love story and After I Left You

Here’s a narrative rule about love stories (but rules are made to be broken) – they usually work in one of two ways:

1.) The romance. Boy meets girl, or man meets woman, but they are separated by apparently insurmountable obstacles: pride and prejudice, for example, or social inequality and a mad wife in the attic. Eventually the obstacles are overcome and the couple are united. Jane Eyre is my favourite example of this kind of story – it’s my Ur-romance, the one I read first.

2.) Is the inverse of 1.) The couple come together some time before the end, and the drive of the story, as it turns out, is towards separation, as insurmountable obstacles come between the lovers and force them apart.

It can be (should be?) hard to tell which kind of story you’re reading till the very last page. Both use your uncertainty and doubt, and the suspense that creates, to hook you in and pull you through. Will they or won’t they?

My second novel, After I Left You, uses two timelines to give the same two people two different love stories. In the present, they meet long after the end of their relationship; many years earlier, they encounter each other for the first time. It’s not will they or won’t they, so much as: why can’t she (or shouldn’t she)? It’s not due to be published till January 2014, though, so if that’s piqued your curiosity, there’s a bit longer to wait to see how it turns out in the end.

Love and un-love, from Casablanca to Gone Girl

I have been told that readers, and viewers, like conclusive endings, and I think that is true, but some stories make a virtue out of uncertainty. Gone with the Wind is an obvious example: will-they-or-won’t-they remains as a final hope, a grace note, conferring a tentative immortality on the sparring lovers by raising the possibility that they may one day rebound together yet again.

Here are some other classic films that fall into the second type (where the lovers fall apart rather than together):

Casablanca. Here the obstacle is War, the epic backdrop against which the troubles of three people don’t amount to more than a hill of beans. But as far as we’re concerned, of course, the individuals are epic, and the war is reduced to a horizon line, its details smoothed and miniaturised by distance.

Brief Encounter. Surely one of the most heartbreaking of love stories. Here the lovers are up against not just society and its values, but also their own morality – the imperative to be good and sad rather than bad and briefly, selfishly happy. I agree wholeheartedly with Zadie Smith’s assertion, in a review published in her essay collection Changing My Mind, about what makes this film so distinctively English: when the couple decide they must part, most of their agonising final encounter is given over to politely passing the time of day with a busybody acquaintance. There really is no escaping other people.

Love Story. Girl meets boy, they fall in love; then she gets sick. There is nothing like definitive loss to define what has been lost.

Every love story needs opposition – whether it’s war, ill health, other people, death – to tell us what love is. But love can be so mixed up with un-love (separation, isolation, anger, fear) that it is difficult to tell them apart. Gone Girl (which might more accurately be called a hate story than a love story) gets plenty of mileage out of our instinctive understanding of this: what possibilities lurk in the un-love we might prefer not to acknowledge?

When I studied Romeo and Juliet at school, our teacher pointed out how shrewd Shakespeare was to introduce a Romeo who professed to be in love with some other random girl, and was teased by his friends for being pathetic about it. When Juliet comes along we are in no doubt that this is suddenly the real thing. It’s mutual, for a start. It’s eloquent (it speaks in sonnets). The lovers are inspired, and transformed… but the odds are stacked up against them, in direct proportion to the strength of their feelings.

Family is always difficult, or so Zaphod Beeblebrox observed when Arthur Dent found himself back on Earth with the primates. A blood feud is certainly an unpromising beginning to in-law relations. Not to mention the dawn that brings the lark and not the nightingale, the charm that works all too well, the message that fails to meet its destination, and, ultimately, mortality, the conclusion that waits to sever all lovers in the end (though in art at least, even that can be overcome).

What do we talk about when we talk about love?

Raymond Carver’s short story What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is a brilliantly concise, and oblique, answer to the questions that all love stories ask: what is love, really, and how do we know when it’s real? The story introduces two couples, who are going to discuss the subject for us by invoking the stories of other couples, all the while knocking back stacks of booze.

First up is Terri, who is, as her husband Mel says, a romantic ‘of the kick-me-so-I’ll-know-you-love-me school’. Terri describes an ex who beat her up one night: ‘He dragged me around the living room by my ankles. He kept saying, I love you, I love you, you bitch… what do you do with love like that?’ Terri is convinced this was love – ‘he was willing to die for it. He did die for it,’ but Mel is not so sure: ‘I’m not interested in that kind of love… If that’s love, you can have it.’

So then it’s Mel’s chance to have his say. What does he talk about when he talks about love? Well – I urge you to read the whole story to find out (it’s only 13 pages long), but here’s a taster: ‘It seems to me we’re just beginners at love. We say we love each other and we do, I don’t doubt it… But sometimes I have a hard time accounting for the fact that I must have loved my first wife too. But I did. I know I did… How do you explain that? What happened to that love? What happened to it, is what I’d like to know. I wish someone would tell me.’

Also, if you haven’t yet, read (or re-read) James Joyce’s short story The Dead, about another lost love. See where it ends. See where the promise of love can take you. And see if the hairs don’t stand up on the back of your neck.

May 15, 2013

Five rules for writing an Oxford novel

Labels can be pretty annoying – I’m sure there’s many a female author who grits her teeth when she hears her fiction described as ‘chick lit’, or is simply perplexed, as I would be if anyone referred to me as a chick. (Chicks are young, cute, vulnerable and clueless, right? I guess any of us might fit the bill on the last two counts, but as for young and cute, well, now I’m 39 I think that boat has sailed.)

But… labels are also jolly useful; and perhaps we only really chafe under them when we begin to feel that they diminish rather than strengthen our appeal. And now that I’ve written one, I’m beginning to realise that the description ‘Oxford novel’ is rather handy.

In my last blog post, I explained that I didn’t originally intend to set my forthcoming novel, After I Left You, in Oxford at all… but that’s where it ended up, albeit a lightly fictionalised Oxford, just to stop ye olde dreaming spires from taking over and trying to make it all about them.

Here are five rules that all those who write about Oxford students are likely to find themselves up against, whether they choose to comply or not.

1. Thou shalt have read Brideshead Revisited, and Evelyn Waugh’s novel will engender more Anxiety of Influence than Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, though you’ll have that somewhere in the back of your mind as well.

You will also, more problematically, have vague memories of Antony Andrews and Jeremy Irons looking fetchingly pouty in cricket whites in the television adaptation of Brideshead Revisited. Which is still blooming brilliant if you catch an episode now, btw. Even after the great Age of the DVD Box-Set, and The Wire and Six Feet Under and Battlestar Galactica and everything.

Because they did make great telly back in the olden days, though not all the time, as you will realise if you ever catch any of old Poldark.

2. Thou shalt find thyself tackling at least some of the subject matter that the mention of Brideshead Revisited evokes.

In no particular order: youth vs experience, privilege, aristocracy, searching for a home and finding it and losing it, drunkenness, alcoholism, addiction, religion, sex, sexuality, the backwards glance, what the passing of time does to people, betrayal, friendship, responsibility for a friend who is self-destructive, love, art, and what it takes to make or recognise good or bad art, and to find the good and bad in both oneself and the people one loves.

What’s that you say? Oxford possibly can’t lay claim to all that territory for itself, because, come on, zillions of novels from all over the world touch on those themes? Quite so. The Oxford novel must always be more novel than Oxford. Otherwise it’s just a tour guide.

A Life Apart by Neel Mukherjee is not an Oxford novel, but a novel about India and England with some early chapters set in Oxford, which it captures brilliantly. This is an Oxford of hit-and-miss socialising, institutional toad-in-the-hole, cold, rain, and cottaging at St Giles’. It is also where Ritwik, the Indian student who has come to Oxford after the funeral of his parents, begins to write his novel, and it is in words, as much as with anyone or in any place, that Ritwik finds fleeting comfort.

‘At the lit display window of Blackwells, a shy, uncertain Mary looks down from her home in the shiny open pages of a luxury art book at some unspecified spot near his feet.’ Mary-in-the-book looks as if she has just finished ‘doling out some grace’; but if so, where has it gone? Ritwik, who has just used a helpline to confess a terror from his past, ‘almost looks around him to see if it is still dispersed in the restless air.’

3. Thou shalt feature a home, maybe stately, maybe run-down, which the protagonist gains access to because of Oxford. (The stay is not quite free, but the true cost may be unclear.)

Brideshead’s wartime neglect and decline frames Brideshead Revisited and it is a visit to the house that tugs Charles from the present back into the past. ‘I have been here before…’

Nick Guest (and of course he is a guest) feels he can appreciate the beautiful things in the Feddens’ plushy place in Notting Hill rather better than they can – and I think of Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty every time I catch the Oxford tube, and pass those white stucco-fronted houses with their secret gardens. (I’m including The Line of Beauty here as a post-Oxford novel that elides the student bit.)

Naomi Alderman’s The Lessons casts a less than flattering light on the posh and their property, suggesting that people are likely to be as careless with their belongings as they can afford to be. Mark is absolutely loaded, and uses his money to buy himself friends (though he likes to keep them a little bit insecure, too, and deploys sex to help with that). However, the Oxford house that he installs them in is rather grubby and unloved and unappealing. Also, the object d’art that comes James’s way because of Mark, the music box, is a rather hideous thing that no-one really seems to want. Mark’s flaws, and the effect he has on others, suggest that wealth corrupts, and quite possibly corrupts a person’s good taste as well as the capacity for other kinds of judgement.

Mark’s funds are limitless, and prone to being wasted, as the brilliant opening scene, with a spoilt feast sinking in the swimming-pool of an Italian villa, makes clear. In Brideshead Revisited, by way of contrast, Rex Mottram points out that the Flytes are much less well-off than they appear, and are heading towards financial disaster – though in their different ways Cordelia, Sebastian and Julia all appear to be willing to renounce their riches.

‘Creamy English charm’… and the lack of it

In The Lessons, though his apparent generosity helps, it is Mark’s self-destructiveness that is his most seductive characteristic. He is in many ways a bit of a git, and knows it. From the yobby food-throwing opening onwards, he is generally lacking in the ‘creamy English charm’ that Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited tells us Charles Ryder’s paintings convey, even when Charles attempts to ‘play tigers’. (Charles agrees.)

Blanche describes charm as ‘the great English blight’. Nick Guest has creamy English charm in abundance, but in the end it is not enough to save him.

NB: where would British fiction be, without its great houses? What would Darcy be, without Pemberley? Or Rochester, without Thornfield? Which has to be razed to the ground before Jane can meet him as an equal.

That’s the problem with the property of the wealthy. The act of visiting may close the gap, and marriage can establish the right to remain, but even that falls short of the entitlement bestowed by inheritance.

Ownership can be undone, though. Rebecca does pretty much force the de Winters into exile from Manderley. Popular fiction can be enticingly subversive in fulfilling the fantasy of taking over from the old guard; take, for example, Barbara Taylor Bradford’s A Woman of Substance, in which Emma Harte eventually gets her own back on the Fairley Hall lot after her time in service there ends in her apparent ruin.

4. Thou shalt also have read Donna Tartt’s The Secret History.

This demonically clever novel is a very different beast to Brideshead Revisited, though in some ways they are flip sides of the same coin.

Now, if you’re the kind of person who worries about spoilers, and you’ve never read Brideshead Revisited, The Secret History, or Antonia White’s novels Frost in May and Beyond the Glass, you’re going to need to skip the rest of this, because I’m going to talk about endings.

The Secret History is, to me, a truly terrifying novel, a horror story almost, that ends on a note of damnation rather than redemption. Its conclusion reminds me of the end of the film of Carrie, when Carrie’s dead hand reaches up from the grave to grab the penitent, remorseful schoolmate who has survived her.

And yet, how could the narrator of The Secret History have possibly avoided arriving at his final bleak vision? His loyalty is with the lost. His life has been saved – who could forget the scene in which he nearly freezes to death over the course of the university vacation? – but who has he really been saved by, and what for, and at what cost?

The conclusion of Brideshead Revisited is the inverse of this, a glimmer of salvation rather than a glimpse of hell. Brideshead Revisited strikes me as being at least as much a Catholic novel as an Oxford one – but does anyone talk about Catholic novels any more? Perhaps it is a label that has fallen into disuse, if it was ever much used in the first place.

5. Thou shalt consider redemption, though it is bound to be, at best, ambiguous.

In Brideshead Revisited, God is going to get you in the end whether you want Him to or not, however much you resist, and Charles, the narrator, does resist, as far as he possibly can, but in the end, it’s no use.

The conclusion, when Charles Ryder reflects on the lamp burning in the chapel – ‘it could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians’ – is despairing and sardonic and redemptive in quick succession, and ultimately, I think, cathartic; it certainly lingers in my memory just as much as Sebastian Flyte’s throwing up and teddy bear, and eventual strange fate. And I say that as someone who is not in the least devout, and who likes lighting candles in churches very much and does so rather superstitiously, but has not actually been to church, apart from on obligatory school visits, for a very long time.

Also, who could forget devout Cordelia fretting about her vocation, the deathbed scene of Lord Marchmain, Julia’s decision not to go with Charles, Sebastian with the monks? (NB – Cordelia is thrown out of her convent school for something she is writing, and the heroine of Frost in May suffers a similar fate for a story about a lurid bunch of sinners, though of course her intent in making them so lurid is only to make their eventual repentance the more powerful.)

Brideshead Revisited is a novel in which the religious faith of the characters shapes what they do, and what they choose to deny themselves. When Charles says to Sebastian that Catholics seem ‘just like other people’, Sebastian says, ‘My dear Charles, that’s exactly what they’re not – particularly in this country, where they’re so few.’

The rosary in the hand and the man in the mirror

So, Catholicism is written through Brideshead Revisited like Brighton through a stick of rock… and yet it manifests itself as a source of mysterious comfort as well as playing a part in Charles Ryder’s heartbreak. The conclusion of Brideshead Revisited reminds me of Clara Batchelor at the end of Antonia White’s Beyond the Glass, turning away from the darkness because of the rosary in her hand; faith is something to live for, a reason to carry on when it seems all else has been lost. (That is a heartbreaking novel, too.)

It is a very different matter in The Lessons, where Catholicism is associated with Mark’s mother’s rejection and attempted repression of his sexuality, and with the expectation of suffering. James is not in the least drawn to Mark’s faith, and concludes that there is ‘only one subject on which life’s lessons are in any way informative’ – the ‘man in the mirror’.

So who is the man in the mirror? At the end of The Lessons, James is free to be who? What? He hardly knows, although he has decided what he is not willing to be. Like Paul at the end of D H Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, it is in moving away from the past, alone, unmoored and insubstantial as a ghost, that he is finally able to save himself.