Alison Mercer's Blog, page 3

April 30, 2015

ChipLitFest: Reasons to Stay Alive, Richard and Judy and mothers in fiction

As the parent of a child with autism, you mess with routine at your peril – but once in a while you have to try something new. And so, last Saturday, instead of doing the usual things, I went off to Chipping Norton Literary Festival (ChipLitFest) to listen to authors talking about their books.

As the parent of a child with autism, you mess with routine at your peril – but once in a while you have to try something new. And so, last Saturday, instead of doing the usual things, I went off to Chipping Norton Literary Festival (ChipLitFest) to listen to authors talking about their books.

I also sat outside lovely indie bookshop Jaffe and Neale drinking tea and starspotting (I saw Lee Child! Charisma! Very tall! Nice to his fans! I was too shy to ask him for a photo/autograph though.)

And I set about filling up my biggest Books Are My Bag bag with signed copies. You can fit a *lot* in a Books Are My Bag bag, and here’s proof – this is what I got into mine:

All that, *and* a brolly and an outfit change…

Matt Haig talks to Cathy Rentzenbrick: Reasons to Stay Alive

First off, I went to see Matt Haig, author of The Humans, talking about his book Reasons to Stay Alive, which is about his experience of depression and – well, the title says it all, really. He was being interviewed by Cathy Rentzenbrick, who is associate editor of The Bookseller and has a memoir coming out in July this year about her brother, who was hit by a car on a night out a fortnight before his GCSE results and was left in a permanent vegetative state.

Sombre subject matter, but listening to them was ultimately enlightening and uplifting, far from the ‘double dose of misery and disaster’ that Cathy drily referred to. It was obvious from the questions asked by the audience that Matt’s philosophical frankness about what he’d been through had touched people and connected with their own experiences.

In the end, Matt said, he was grateful for his experience of anxiety and depression. ‘It’s made me appreciate life more, and appreciate pleasure more. When I was younger, it was about extremes. Now I’ve got a thinner skin, I can enjoy going for a walk and being with my children.’ He added: ‘You need to feel the terror to feel the wonder.’

Matt on writing? ‘For me writing is both uplifting and depressing. The actual writing is uplifting; the career aspect is difficult.’

Richard and Judy with Julie Cohen

On to Richard and Judy, interviewed by my fellow Transworld author Julie Cohen whose novel Dear Thing was a Richard and Judy Book Club pick. I never actually watched the Richard and Judy TV show… misspent youth! They’re brilliant – what a double act. It’s an art to tag-team the way they do, to be warm and open and personal, to tell anecdotes that work as stories. I was absolutely and completely charmed. It was a cosy venue − Chipping Norton’s lovely and compact Victorian theatre − and it really did feel like being invited into their living-room.

Richard talked about book programmes on TV – his view was that stand-alone book programmes couldn’t work, and that the Richard and Judy book club had been so successful on TV because it was an item on a show that was also about all sorts of other things. He recalled the first book they featured, Star of the Sea by Joseph O’Connor, and how, three days later, the publisher rang up to ask for advance warning if they were to feature another book on the programme, as they had sold out of the entire print run.

Both Richard and Judy discussed their attachment to Cornwall (I can definitely identify with that), which is where Judy’s novels are set. Now I know a bit about Looe Island! They also both spoke very movingly about their memories of their friend Caron Keating, who died in 2004.

Richard and Judy on writing? Both stressed the importance of pressing on and finishing – and both recommended Stephen King’s On Writing (I’m a fan too). And Richard said, ‘I’m a bloke from Romford, Essex, who left grammar school at 16 – if I can do it, anybody can do it.’

Mothers in fiction: Clare Mackintosh, Hannah Beckerman, Rowan Coleman

Next: mothers in fiction, a panel discussion with three novelists.

Clare Mackintosh was the founder of ChipLitFest and her debut novel I Let You Go, a psychological thriller, is out in paperback in May. It’s about a mother who moves to a remote cottage on the Welsh coast in an attempt to start a new life after a tragic accident – but then the past catches up with her. Clare observed about her novel, ‘I think you write books like that, and you read books like that, because ultimately you want to count your blessings.’

Rowan Coleman has written more than twenty books, including The Memory Book, which was a Richard and Judy Book Club pick and is about Claire, a mother whose family help her put together a book of memories after she is diagnosed with early onset Alzheimers. The Memory Book has its fair share of romance – Claire has a lovely husband (Rowan explained during the course of the talk that she didn’t want anybody in this book to be villainous), but it’s also very much an affectionate portrait of a matriarchy, with starring roles for Claire’s mother and daughter.

Hannah Beckerman’s debut novel, The Dead Wife’s Handbook, is about a woman who watches from the afterlife, or a kind of limbo, as her husband and child adjust to life without her – and then her husband meets someone new. Hannah wrote it when she was pregnant with her first child – it was then picked up for publication and she did a thorough rewrite after having her baby, having realised that the emotions her heroine went through didn’t go nearly far enough to reflect the reality of motherhood.

The novelists were asked to name their favourite mothers in fiction, and these are the books they mentioned:

Room by Emma Donoghue

Dear Thing by Julie Cohen

The Girl With All the Gifts by M R Carey

… though the very first fictional mother mentioned was Mrs Bennett, and I have to say she’s the first one I think of too.

Mulling over this later, I found myself thinking about Rachel in Patrick Gale’s Notes from an Exhibition (especially the scene where she gets so absorbed in drawing by the sea that she more or less forgets about her kid – when you read this you are on tenterhooks wondering if he is going to be all right). Also: Moominmamma, and the scene in The Magician’s Hat when she looks into Moomin’s eyes and knows it’s him, even though the magic hat has completely changed his appearance. That’s mother love all right.

To give Rowan Coleman the last word on motherhood: ‘It’s about being there when nobody else will be there. That’s what you know your mum will do, and what you know you will do for your children.’

Writers, Not Writing: an exhibition of photos by Jane Stillwell

Finally I went to see the exhibition of photos of writers not writing, by Jane Stillwell. Cue multiple double takes as the subjects wandered round chatting and swigging champagne while their portraits looked on from the walls… Here’s mine.

It was a great day – though it was lovely to get home too. My son asked where I’d been: ‘Mummy was invisible,’ he declared after I tried to explain. (Charlie Brown turns invisible in a cartoon he likes.)

I was also glad I made time to sneak away from the hubbub, sit on a bench, take in the scenery and read my book (Rachel Hore’s A Gathering Storm, which features an exceptionally heroic mother.)

More about parenting, books and other stuff…

The moment I found out about my son’s autism

Why I love Cornwall

Steve Shirley on autism, the Kindertransport and the most loving thing a parent can do

February 22, 2015

Male writers who changed my life

Girl meets boy! A proof of my 2nd novel hanging out with my OH’s Pynchon

Stevie Smith said differences between male writers and female writers were more obvious if the writing was bad. I’m a big fan of Stevie Smith, but I’m not sure that’s true. To quote The Life of Brian, we are all individuals. The writers I love have a distinctive voice and a way of seeing the world, and yet they tell stories that have a universal appeal that reaches way beyond the limitations of their personal experience and circumstances.

Reading blurs and breaks down boundaries and allows us to access the imagined unknown, and to experience many different lives (to paraphrase a line from one of George RR Martin’s Game of Thrones books, the man who reads has many lives, the one who does not lives only once). When I’m reading a book I love, I could be anyone, and so could the writer; there’s only the story. (Perhaps that’s what Stevie Smith meant.)

So why single out male writers for a list like this? Partly it’s to redress the balance – I’ve already blogged about women writers who changed my life (parts I and II – III will come at some point), so it seems only fair.

But it also raises a couple of questions… (The list follows so keep scrolling if you want to check it out…)

Are there differences between what men write and what women write, and if so, what are they?

Hmm… see above. That said, I wonder if women writers, outside of literary fiction, are rather more hampered than their male counterparts by the expectation that female characters should be sympathetic – it’s the long dark shadow cast by Bridget Jones.

Adorably goofball? Idealised? Sweet? Depending on what you mean by sympathetic, it could be tricky for a heroine of this kind to do bad, interesting stuff, or be more than a victim of other people’s bad, interesting deeds. Writers of suspense fiction can get away from this, though, and have heroines who are faithless, manipulative and so on – see Tamar Cohen and Harriet Lane for examples.

Are there differences between what men and women read?

Sometimes – yes. Did men bother with 50 Shades, and its sequels? (Did anyone keep going with the sequels? But of course they did – in droves.) I know some men were instructed to read the books to pick up sex tips (one imagines them reluctantly relinquishing the sofa and the football, or whatever). But by and large, surely, it was women who bought 50 Shades and snickered about it round the water cooler, or in lesson breaks at school. It was a female bonding book, and perhaps the only real way any writer can achieve that is to write about sex. (Note to self.)

50 Shades was a female bonding book, and perhaps the only way any writer can achieve that is to write about sex.

When I was a student, a fair few of my male peers were big fans of Martin Amis. They fancied Nicola Six; the line about her having her own personal cinematographer was admiringly quoted. There was something about the way they liked Amis that really bugged me; it was as if he was an uber-witty mouthpiece for stuff they couldn’t say well enough to get away with.

One of my closest female friends advised me to get over it and read Success, which I did, but I didn’t love it. I’m still ambivalent, though I think his essays are brilliant (his literary criticism makes me feel slightly scared to write; I’m pretty sure I am unworthy.)

It was as if Martin Amis was an uber-witty mouthpiece for stuff they couldn’t say well enough to get away with.

Are there differences between how books from different genres are marketed?

Hell yeah. Obviously. Maybe increasingly.

Look – no pink! 1980s Mary Stewart

Across the board, with anything that’s available for sale, the gender marketing gap is striking and seems to be getting bigger all the time, and it starts to transmit its insidious message even before you’re born. When I was pregnant in 2003 and ventured into Mothercare for the first time, I felt like I’d been inducted into a whole new world: pink on one side for the girls, blue on the other for the boys. And it goes on.

As a girl in the 70s I had dungarees with workmen’s tools embroidered on them and Richard Scarry books illustrated with all the primary colours. If I was a kid these days, I’d have been much more likely to spend my days in a pink fairy costume reading a pink book about pink princesses. I really, really wanted to be a fairy, ideally called Lavinia – you see, I definitely wasn’t a tomboy – so probably I would have been quite happy with this, at the time anyway.

the wannabe Lavinia fairy

I didn’t turn out to be a practical, puncture-fixing type, sadly, or a practical, fairy-cake baking type either, but I’m still grateful that the prevailing culture didn’t indulge my pink princess tendencies.

I really, really wanted to be a fairy, ideally called Lavinia. You see, I wasn’t a tomboy.

I don’t know whether it’s anything to do with the tidal wave of pink produce for girls – maybe it isn’t – but differences in how girls and boys explore their interests seem to be fixed very early on. When my daughter (not a big fan of pink) went to a coding workshop last year, she was the only girl. When she went to an art workshop, there were stacks of girls. Both workshops involved making pictures – it’s just that at the coding one, you used a computer to do it.

There’s an uphill struggle ahead for any initiatives to get women into science/tech careers – or even to study relevant subjects post-16, or study physics at GCSE, which is not an option in a large number of state schools anyway. In many cases they will already have decided long ago that it’s not for them. It’s too late.

OK – on with the list.

The male writers who have changed my life

This is a list of writers rather than of books, so the writers I have included have written more than one novel that has made a big impression on me. Hence some major omissions, of which the biggest is The Catcher in the Rye, which I discovered at the perfect time, as a lonely teen in the school library. Also, Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which features one of my all-time favourite heroines.

I haven’t touched on non-fiction (Al Alvarez would definitely be on that list, along with John Carey) or poetry (that’ll be a long one, with a starring role for T S Eliot and, of course, my OH Ian Pindar.)

Douglas Adams. Hitchhiker’s Guide and The Restaurant at the End of the Universe have soaked into my unconscious. I still often find myself thinking about the uniquely biroid lifestyle, or the first ten thousand years being the worst, the second ten thousand being the worst too, and after that, going into a bit of a decline. Or it being too late to worry that you left the gas on when you’re about to watch the universe boil away into nothingness. Or the mark of civilisation being the question, ‘Where shall we have lunch?’ Or about how you might feel safe on an alien spaceship if only you could see a small packet of cornflakes amid the piles of Dentrassi underwear. And so on.

Ian Fleming. Mary Goodnight is the reason I wear Chanel no 5 (though Marilyn Monroe also has something to do with it.) A couple of years ago I wrote a short story called What would a Bond girl do? The story probably wasn’t up to much, but I still kinda like the title.

Around the same time I read the Bond books (early to mid teens) I read a lot of Dick Francis novels, but all I really remember from them is the description of a hungry jockey griddling himself a steak. Also, that 80 hours into learning to be a pilot is the most dangerous time, because you begin to think you can do it and forget to be afraid, and the dictum that a truly satisfied woman doesn’t need to read dirty sex (hmm. 50 Shades.)

Raymond Chandler. Especially The Big Sleep. Love those slangy, cynical, man-of-the-world cadences – the beaten-up toughness of it. Love the old rich man with the orchids, the sharp dialogue, the ending. When I first read it I didn’t really get a lot of it, but it didn’t matter. And now I’m thinking of Bogart and Bacall. Btw, there is a brilliant essay on how Humphrey Bogart became Humphrey Bogart in a collection of essays by Louise Brooks, Lulu in Hollywood (if you read the book, look out for Charlie Chaplin and the jolly orgy involving paint).

Ernest Hemingway. My dad likes Hemingway and once told me The Old Man and the Sea was his favourite novel. Hemingway was also on an improving reading list that my English teacher gave me, and I read a fair bit aged 16 to 18 and loved it – For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Sun Also Rises. The short story Hills Like White Elephants has stayed with me – it catches so clearly the sterile feeling of being with a lover when there is almost nothing more to say. Read The Killers recently – eerily brilliant.

D H Lawrence. I read lots of DHL aged 16-21. (He was on the improving reading list too, and, later on, the degree syllabus.) The end of Sons and Lovers is one of my favourite endings of any novel – more affecting, to me, than the arguably more celebrated ending of The Great Gatsby. One of the endings of Neel Mukherjee’s The Lives of Others hits the same note: poignancy and exile, moving on and out into the world. And I like Ursula at the beginning of Women in Love, like a daffodil with all the growth going on underground, before the shoots come up for everybody else to see – and Mrs Morel with the lilies in the moonlight, her brute husband left behind indoors.

Raymond Carver. Bought mid-90s, collected short stories, after Short Cuts came out. Shining example of what can be achieved by being lean and spare. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love stays with me – an inspired sideways glance at the question of what love is, up there with James Joyce’s The Dead. Also the one about the three men who go fishing and find a body. And Cathedral.

James Ellroy. How do you find writers you love? Movie adaptations don’t hurt. I bought LA Confidential after seeing the film. Read the first page, thought huh? What’s a shiv? Soon found out. Got into the argot and read a load more. Big, ambitious books with amoral heroes – actually, he shares some qualities with George RR Martin, of which more to follow: an eagle eye for the workings of power; a desire to tell stories about bad people with a bit of good in them, and good people with a bit of bad in them; and an interest in twisted families.

William Gibson. Discovered mid-90s, browsing in a bookshop. The inventor of cyberspace, no? The kind of cyberspace we’re still evolving towards – a virtual simulacrum of the world we live in, with criminals, hustlers, defended power bases and ghosts. And Molly with the retractable claws… I often think of William Gibson when I see a wasp’s nest, or read about the hyper-rich – he’s brilliant on the dehumanising effect of immense wealth.

William Gibson introduced me to Cornell boxes – years later I saw some for myself and was stunned by how beautiful they were. Sometimes when I see my son, who has autism, set out his toys, I think of those Cornell boxes. There’s something very precise about the spacing and arranging, something numinous, even if I don’t understand it.

I once tried to write an imitation William Gibson story. It wasn’t very good, as my boyf at the time reluctantly, but rightly, pointed out.

George R R Martin. I’m going to pay a swift homage to Tolkein here, in passing – The Lord of the Rings had pride of place on the bookshelf in my mum’s house and we painstakingly taped the radio adaptation. My OH recently acquired a bit of the recording and it’s still brilliant.

Nearly at the end of season 4 of Game of Thrones as I write. George RR Martin has a spectacular ability to create real people in a fantasy world. Intensely believable and often terrifying. Grim to think that pretty much any of the dark stuff in the books has really happened sometime, somewhere – and a relief when humanity’s more redemptive qualities come through: courage, integrity, resourcefulness, self-sacrifice, a sense of humour in the face of overwhelming odds, loyalty, vision, love.

Neel Mukherjee can do it all – his fiction is funny, profound, vivid, sweeping, and revelatory about how and why people do the things they do. After I’d read The Lives of Others I felt I understood more about why terrorist atrocities happen than when I started – it was an education. I’m very much looking forward to his next. The extract that appeared in January’s Granta was startlingly, shiver-inducingly spooky.

Patrick Gale. I read my first Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition) last year and could happily spend the next working through everything else he’s written. Look out for A Place Called Winter, out next month – I was lucky enough to receive a proof copy.

Patrick Gale’s novels give me a feeling of space and light: new people, new territories, illumination. He’s also a damn good storyteller. When his characters do unexpected things, or have unexpected and sometimes terrible things happen to them, you’re left thinking – yes, that’s how it is, that’s the truth of it. He knows what makes people tick.

OK, so that’s my list. I know as soon as I post this I’ll be troubled by omissions – other names and books are occurring to me as I type, clamouring for inclusion – but you have to start somewhere…

December 21, 2014

My books of 2014: a year in reading in review

Over the last year, I’ve travelled in time and space from Calcutta in the late 1960s to Canada in the 1900s. I’ve witnessed the sinking of a Thames houseboat (the cat escaped, but only just), the lifting of beet on a struggling Yorkshire hill farm and the smoking of Sobranies at a Hungarian party in a tiny London flat (‘Dar-link! Von-dare-fool!’) I’ve witnessed the invasion of a strip club, a miscarriage at a baby shower, people being abused and betrayed and drawn into relationships with those who have misused them; painters at work, alcoholics in recovery, and, from the perspective of the afterlife, a woman trying to get over her still-living husband.

Over the last year, I’ve travelled in time and space from Calcutta in the late 1960s to Canada in the 1900s. I’ve witnessed the sinking of a Thames houseboat (the cat escaped, but only just), the lifting of beet on a struggling Yorkshire hill farm and the smoking of Sobranies at a Hungarian party in a tiny London flat (‘Dar-link! Von-dare-fool!’) I’ve witnessed the invasion of a strip club, a miscarriage at a baby shower, people being abused and betrayed and drawn into relationships with those who have misused them; painters at work, alcoholics in recovery, and, from the perspective of the afterlife, a woman trying to get over her still-living husband.

I’ve encountered villains, lovers, rescuers, torturers, aliens and a whole host of heroines. I had the chance to get to know Penelope Fitzgerald and George Eliot, and I observed a Brush with Greatness: (fictional) artist Rachel Kelly bumping into Dame Barbara Hepworth on a booze run.

It has been a terrific year’s reading, mainly of novels, almost all by writers who were new to me. Some were published this year, others some time ago; one – Patrick Gale’s A Place Called Winter − is due out in 2015. Some were recommendations; others I looked up because I’d come across the writers on Twitter or heard about them online. Twitter has played a part in my reading this year as never before – it’s a great medium for fandom.

The other novelty for me was that it was the first year I started reading on Kindle – though I’ve read most of these titles in paperback, which I still prefer. I was talking to a reader at a book group recently who said she read everything on her Kindle and had no idea what the books were called – if people asked her what she’d been reading, she had to look it up. She had started making a point of checking what the covers looked like. I’m still getting my head round this brave new ebook world… I don’t feel like I really own a book unless I have it on paper, and I don’t feel like I engage with a story as closely unless I’m actually turning the pages. OK, so we have severe book storage problems in our house, but as far as I’m concerned that is the only real advantage of the ebook. Also, I quite like reading in the bath. So chances are that 2015 will mean yet more demands on our limited shelf space…

Here are the books I read in 2014, which, in a rare fit of nerdiness, I’ve put in alphabetical order by author. (Check out the links to see their Twitter feeds).

Hephzibah Anderson: Chastened. What happens when you give up sex for a year in the hope that it will improve your chances of finding love – or at least make romantic disappointments a bit less heart-wrenching? Does treating ̕em mean keep ̕em keen, or is it just the route to a different kind of loneliness? This candid, witty, elegantly written study of sexual politics in and out of the bedroom is also a paean to the freedom of single-girl city living. It took me right back to my own London days and made me hanker to visit New York. (Should have gone in my twenties. Have still never been.)

Hannah Beckerman: The Dead Wife’s Handbook. The narrator of this novel is dead and grieving, existing in a nebulous afterlife from which she is permitted occasional glimpses of her husband, young daughter, mother and best friend. But as time moves on and their lives begin to change, can she find it in her heart to let go – especially when her husband is eventually coaxed into starting to date again? A smart, tear-jerking and expertly realised portrayal of the frustrations, sadness and joys of playing witness to your own life after the event, and coming to terms with your loved ones’ slow recovery from your loss.

Amanda Brookfield: A Family Man. This is the story of a man whose wife suddenly vanishes, leaving him to learn how to juggle work, childcare and the confusing possibility of new romance as a single parent. A warm, sympathetic account of a dad who finds that what looks like disaster is actually a chance of a different kind of life. Originally published in 2001, now available in ebook.

Julie Cohen: Dear Thing, Where Love Lies. Gosh, it has been a year of weepy reading! Dear Thing, Julie Cohen’s tale of a tug-of-love between two women who both come to want the same man and the same baby, got my tear ducts going. It’s crisply written, artfully structured and beautifully observed – the scene where Claire has a miscarriage at a baby shower is all the more heart-rending for its restraint. Julie has an acute eye for how people behave in extremis and how even good, kind, likeable people can be brutal when circumstances pit them against each other.

Where Love Lies is a lush, mysterious, time-travelling love story that sends its narrator back to her first experience of romance and then pulls her back into her present. Felicity is at the mercy of her senses, overwhelmed by flashbacks to her past and tempted to act on the old feelings that she is experiencing afresh; so who does she truly love – the old boyfriend who she feels impelled to seek out, or the long-suffering husband who has no idea what she is going through?

Tamar Cohen: The Broken. I *had* to peek at the end of this one – I literally couldn’t bear not knowing how it turned out and I had to get some sleep! It’s a study of conflicting loyalties, jealousy, rivalry and anxiety about doing the right thing. When their friends Sasha and Dan break up, Josh and Hannah find themselves sucked in to the fallout: is it wrong for them to meet Dan’s hot new model girlfriend, and is Sasha really as terrible a mother as Dan believes? The story is laced with dark humour and sharply-observed details of the insecurities and self-destructive impulses tucked away behind the shiny facade of North London domestic bliss. Wraps up with a mean twist. (I read Tamar Cohen’s The Mistress’s Revenge last year – there’s a bit about it in my round-up of my books of 2013.)

Rowan Coleman: The Memory Book. This is one to be read with the tissues at the ready, though it’s also very funny – one of my favourite scenes involves a mother and grandmother invading a strip club in order to retrieve the daughter they have found out is working there. This is a novel all about a matriarchy, and Claire, the mother, is at its heart, seeking to record her life in her memory book in a race against time, as she begins to lose her knowledge of who, when and where she is. However, the stories from the past are far from finished, and an intrigue unfolding in the present threatens to wreak havoc on the family as everybody struggles to come to terms with Claire’s worsening condition. Claire’s other half, Greg, is the love of her life, and yet she is meeting someone in secret, despite her increasing confusion. Is she putting herself in danger, and will she be able to help her loved ones make sense of their shared past before it’s too late?

Jenny Colgan: Meet Me at the Cupcake Cafe. A super-sweet comic confection that’s as much about getting your business dream off the ground as it is about choosing Mr Right, though it’s about that too. Published in 2011, it’s the story of how Issy Randall uses her redundancy pay-off to set up a charming café – but will her venture survive the interest that her property developer ex-boyfriend decides to take in it, and will Issy be taken in by him? I saw Jenny at an author event with Lisa Jewell and Rowan Coleman at Henley Literary Festival back in October, and Jenny explained that she was inspired to write Cupcake after moving to France and realising that she was going to have to learn to cook from scratch if her children were ever going to have anything to eat other than carrots, apples and crisps. I’m a baker of Bridget Jones-like incompetence myself, but reading Cupcake did inspire me to dig out my one and only truly reliable cake recipe.

Samantha Ellis: How to be a Heroine. Anne of Green Gables, Lizzie Bennett, or the ladies in Lace? This book, a re-reading of the formative novels that helped shape Samantha’s ideas about what makes a heroine, sent us all back to the fiction we read as children and teenagers to see how different it might look from the perspective of experience. It sparked a zillion conversations and got me thinking about my own personal canon of the women writers I’ve loved the most. Samantha’s book is a nostalgia-inducing book-lover’s approach to the questions that trouble all heroines: how to find love, happiness, yourself. Pure pleasure – and thought-provoking, revealing, brave, frank and funny, too.

Penelope Fitzgerald: The Bookshop. Also Hermione Lee’s Life of Penelope Fitzgerald. I came to Penelope Fitzgerald through the reviews of Hermione Lee’s Life. I was struck by the details that conveyed the indignities of not having enough money and trying to find ways to make do, sometimes with disastrous results: the affordable but leaky and decrepit Thames houseboat that ended up sinking, the attempt to dye her hair with tea-bags. I read the biography and then read my first of her novels, The Bookshop. It’s short, succinct, devastating and brilliant, and the sucker-punch ending floored me and made me howl as few books have done (the ending of Notes from an Exhibition also caught me by surprise by making me bawl like a thwarted baby.)

Patrick Gale: Notes from an Exhibition and A Place called Winter. (A Place Called Winter is out spring 2015 – I was lucky enough to receive a proof copy.) My work book group read Notes from an Exhibition some time ago; I missed it at the time (writing deadline – writing does sometimes interfere with my reading) and decided to catch up on it later. It’s set largely in Cornwall, so was great to read in the run-up to our first ever family holiday and my first visit to Cornwall in more than a decade. I admired and enjoyed it very much and it made me cry hopelessly. Some brief notes on what struck me: the portrait of the painter at work – so well realised, the physicality of the paint, the messiness of it; the Quakers; the relationships between the siblings, maternal and marital and filial love; and the pure storytelling – the movement from one point of view to another, revealing one surprise and then another until the last page goes over and you realise there isn’t any more. I’ve been in the process of moving from writing in the first person for my second novel back to the third person for my third, and it was a liberating reminder of just how much you can do with the third person.

A Place Called Winter – this is a historical novel about Harry Cane, a gay man in the 1900s who is forced by a scandal to leave England and settle in Canada. He embraces a new life as a farmer, but any chance he has of finding love and happiness is always attended by terrible jeopardy. It’s a profoundly romantic story – love stories need opposition, and if Harry is to be lucky enough to find a man to love and be loved by in return, their relationship will always be under threat, always required to remain a secret. There are some harrowing scenes of violence, and their consequences are explored with great truthfulness and insight. This is a novel with a sweepingly vivid sense of place, brilliant on the challenges and satisfactions of working on the land in different seasons and on the search for a place to call home and someone to share it with. It feels like a story that was crying out to be told.

Matt Haig: The Humans. A couple of years ago I read Moondust by Andrew Smith, which describes his mission to track down all of the surviving astronauts who walked on the moon and record their memories of it. It seemed that what was really remarkable about going to the moon was the perspective it offered on the Earth; how beautiful and precious it appears from a great distance, surrounded by blackness. Matt Haig’s wise and funny novel pulls off a similar trick. There’s no place quite like home and the people that make it so – and how better to arrive at a full appreciation of what it is to be human than by adopting the perspective of an alien who has fallen to earth, with a mission that is in jeopardy as soon as he begins to learn what it is to love?

Amanda Jennings: The Judas Scar. Amanda’s second novel is a dark, suspense-filled page-turner that explores the guilt felt by a man who failed to protect a childhood friend from a brutal history of boarding-school bullying. It’s also a tale of a marriage that is at risk from secrets on both sides, as well as being under attack from the treacherous intentions of apparent friends. When someone Will never thought to see again unexpectedly begins to play a part in his life once more, the consequences are potentially deadly – but who for? There is plenty that Will hasn’t told Harmony, his wife, and by and by Harmony will have reasons of her own to feel guilty… Amanda’s first novel, Sworn Secret, came out on the same day as my first, Stop the Clock – publication day twins! Amanda wowed a packed-out Henley Town Hall at Henley Literary Festival this year and I’m looking forward to her third novel.

Harriet Lane: Alys, Always. The scheming, shrewd, manipulative narrator of Harriet Lane’s debut novel is one of my favourite antiheroines ever. A dark twin of the narrator of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, she has no compunction whatsoever about trying to step into a dead woman’s shoes, and is dauntlessly predatory as she hunts down the highly-regarded widower she has set her heart on. A sense of something unseen, or something bad about to happen lurking around the corner, permeates this book. Will the schemer be exposed? Has she ventured out of her depth? It’s also a darkly funny account of what it takes to get ahead in the literary world, which might aptly be subtitled (with a nod to Tamar Cohen’s debut) The Sub’s Revenge.

Rebecca Mead: The Road to Middlemarch. One of my most vivid memories of reading this year is of turning to this book after a car breakdown on the road to Abingdon one hot summer afternoon, while waiting for the RAC to come and sort me out. It’s a personal appreciation of George Eliot and an exploration of her work and life, and it’s wry, witty, sharply observed and ultimately profoundly touching. I finished it filled with admiration for George Eliot, both for the brilliance of her writing and the courage it took to live her life as she did, on her own terms, flouting convention by cohabiting with a married man. Rebecca’s tribute to George Eliot was an excellent diversion from my roadside predicament, which was, thankfully, soon resolved.

Charlotte Mendelson: Almost English. Marina longs only to be inconspicuous at her super-snooty English public school, but her outspoken, glamorous, elderly Hungarian relatives have other ideas, and are not inclined to be discreet about them. They are ever ready to judge the appearance and behaviour of all and sundry – Marina included – with their favourite epithets, Von-dare-fool! and Tair-ible! And yet there is no doubting their love for her and the sincerity of their desire to see her succeed – and the weight of the responsibility she feels towards them in return. Includes an acidly funny portrait of Marina’s mother’s dangerous yearning for romantic escape, or, at least, a life that involves a modicum of privacy, a decent duvet and some labour-saving devices; an account of an almost-romantic reunion; a tragicomic tale of miscommunication between mother and daughter; a sly debunking of a smug male authority figure; and a hilariously liberating conclusion. All the joys of the school story set against the perfect foil: Marina’s Sobranie-smoking, silky-bloused great-aunts and their Hungarian expatriate community. And oh, the food! Made me so long to be invited to one of the great-aunts’ parties in their tiny London flat.

Lorrie Moore: Birds of America. I got this so I could read the short story People Like That Are the Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk. SO GOOD. If you’ve ever spent any time in hospital with a child – or in hospital, full stop – or just want to read a miracle of storytelling packed into 39 pages, this is for you.

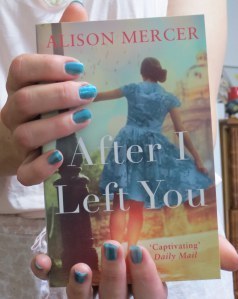

Liane Moriarty: The Husband’s Secret. This was recommended to me at a book group I went along to talk to about After I Left You. It’s a masterclass in how to build tension by moving between different points of view and raising the reader’s suspicions: just how dreadful is the husband’s secret, and what is the wife going to do when she finds out? It also explores a classic moral dilemma: what would you do if you found out the person you’d shared your life with had done something terrible before you even met? Cleverly structured and psychologically acute, plus every chapter is as well crafted as a stand-alone short story.

Neel Mukherjee: The Lives of Others. Neel’s second novel was shortlisted for the Man Booker prize and is now on the shortlist for the Costa and nominated for the Folio Prize. So many scenes stick in the mind, from the act of sabotage involving nail varnish and special clothes to the bitter, tender ending. It is a brilliant novel, and a devastating account of the violent and terrible consequences of great inequality.

Alice Peterson: One Step Closer to You and Monday to Friday Man. Monday to Friday Man knocked Fifty Shades of Grey off the kindle no 1 spot; it’s a touching romance about how meeting fellow dog-walkers and taking a weekday lodger might just get you over heartbreak and change your life, with a moving back-story about a much-loved sibling. Alice is brilliant at weaving together heartwarming love stories with explorations of experiences that bring her characters into conflict and put them to the test. Her new novel, One Step Closer to You, is about addiction and its impact on family life and relationships; its heroine’s recovery is threatened when the father of her child seeks to come back into their lives. The AA scenes are brilliantly done and I found the scene from Polly’s childhood when her brother Hugo leaves home for a residential school absolutely devastating. Polly is left feeling that she can never make up for how much her parents miss Hugo, and the novel shows how this and other losses add to her vulnerability when looking for love.

Geoffrey Robertson QC: Stephen Ward Was Innocent, OK: The Case for Overturning His Conviction. I’m distantly related to Stephen Ward, which doesn’t make me feel any closer to his story than anybody else, but did add an extra frisson of curiosity to the experience of reading this spirited defence of a man who seems to have been a charming, hedonistic chancer, well and truly hung out to dry by the Establishment. I hope I’m still around in 2046 when they finally release the records relating to the Profumo affair – my hunch is that there may yet be some interesting stuff to come out… (Here’s a recent Guardian article by Geoffrey Robertson about the Profumo affair, written following the death of Mandy Rice-Davies.)

Barbara Seaman: Lovely Me: Life of Jacqueline Susann. I always approach books that touch on autism with both curiosity and wariness – will they be upsetting? Infuriating? Enlightening? I was appalled to learn that Jacqueline’s son, her only child, was given ECT at the age of three in an attempt to treat his autism. (He was institutionalised soon afterwards.) It’s a devastating book, but an inspiring one too – Jacqueline was nothing if not a grafter. Her Valley of the Dolls is, apparently, one of the ten most widely distributed books in history – along with the Bible, Mao Tse-Tung’s Quotations and the Guinness Book of World Records.

Susie Steiner: Homecoming. This debut novel about a Yorkshire farming family introduced me to a tight-knit world where old livelihoods are increasingly hazardous, and making the wrong decision about how and when to lift the beet is to incur the risk of financial ruin. But what happens when the capable prodigal son returns? The characters are beautifully and lovingly evoked, from the pub vamp to the daughter-in-law-in-waiting who loves nothing better than to be left in peace with her wiring. An illuminating depiction of the horrors of lambing gone wrong and the satisfaction of seeing new life brought into the world, sibling rivalry, the settling of scores and the dawning joy of finding love you don’t want to live without.

Rebecca Wait: The View on the Way Down. Rebecca is an honorary Abingdonian and I’d heard this debut novel spoken about admiringly by mums and grandmothers in my children’s school playground. It’s about a family that has fallen apart after the death of one child and the disappearance of another: is there any hope of reconciliation? Painful family mealtimes, brotherly bonding over computer games, the awfulness of girls at school and the edgy, forceful positivity of the mother who’s trying and failing to hold it all together are all brilliantly summoned up in this tender, bold and poignant novel. A terrific debut.

Polly Williams: Husband, Missing. Gina fell in love hard and married fast. Six months later her husband, Rex, goes on a trip to Spain with his brother and some friends, and disappears. As Gina investigates Rex’s disappearance and begins to uncover the secrets he has been hiding, she is forced to confront the possibility that the charismatic, successful man whose spell she fell under so quickly was an illusion. But what became of him – and what is his brother not telling her? And was there something crucial that she had failed to tell him? A cracking tale of marital mistrust and how falling in love can blind you to truths you don’t want to acknowledge.

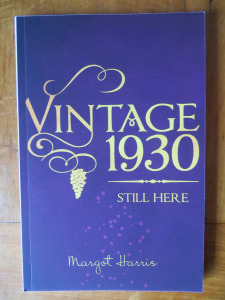

So, what’s on my reading list for 2015? I’m currently reading Lisa Jewell’s The House We Grew Up In, and I want to read the new Louise Douglas, Your Beautiful Lies, and Sarah Vaughan’s The Art of Baking Blind. I’ve dipped into the autobiographies of Dame Stephanie Shirley and Margot Harris and will revisit them to read them more closely. My Christmas list included Daughter by Jane Shemilt, Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald, Love, Nina by Nina Stibbe, The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion, Apple Tree Yard by Louise Doughty and My Policeman by Bethan Roberts. I’ve bought Rachel Hore’s The Gathering Storm and Santa Montefiore’s The Butterfly Box as gifts but I think I’ll be able to borrow them by and by – so, plenty to keep me going!

I also predict that, in 2015, somebody will write an article bewailing the state of women’s commercial fiction. (To echo Mandy Rice-Davies – they would, wouldn’t they?) This year Julie Bindel had a bit of a go in a blog post for The Spectator, coining the phrase ‘sick chick lit’ (others have talked about ‘chick noir’ or ‘domestic gothic’ when attempting to highlight the publishing trend Julie was getting at). There was then a set-to on Twitter which gave rise to my phrase of the year (another Julie Bindel coinage): Chick Lit Lout. I’ll have that on a t-shirt please, in glittery pink.

I’ll sign off with a quote from one of George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones books: ‘A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies… The man who never reads lives only one.’ Merry Christmas one and all, and all the very best for 2015. And happy reading!

at the Mostly Books Books Are My Bag party – my stint as the window display!

November 7, 2014

Why I love Cornwall

My abiding memory of my first trip to Cornwall, aged four, is of walking back from the beach in an odd assortment of clothes and no knickers. I’d been swept out to sea; well, that was my impression of the experience, but really, I’d been knocked off my feet by a wave. Everyone I was with donated something for me to put on, but underwear I had to do without.

My seven-year-old son, who has autism, had a similar wardrobe crisis recently following a too-close encounter with the sea. This was at St Ives, and it was beautiful – the sea and the sky were an extraordinary translucent blue (half-an-hour later, the mist rolled in and it all vanished). We were just about to leave when he fell over on the wet sand and soaked his top and trousers. A rescue party scaled the cliffs in search of a new outfit from a charity shop, duly returning with a surfer-dude shorts and hoodie look; in the meantime, he circled the sand in his anorak and a pair of slightly damp, and therefore transparent, white pants.

I’m told that the Anglo-Saxons regarded today, the 7th November, as the beginning of winter. It’s been so windy and foggy and murky in Oxfordshire over the last few days, it’s hard to believe that not so long ago the children really were paddling in the sea.

Our half-term trip to Cornwall was the very first family holiday the four of us have ever had. Given my son’s autism, a holiday has always seemed more likely to be an ordeal than a treat. So it was the most amazing feeling to look out of the train window and see an alien landscape – rugged, with unfamiliar trees and a haze of mist being sucked up towards the sun. The mist cleared as we approached Penzance and we saw the sea. The light was unmistakably different to home – more vivid: it was as if we’d stepped out of a Constable or a Reynolds and into a Cezanne.

We stayed in the family room at the youth hostel in Penzance – run by lovely people (the breakfast is very good too). But our stay was really made special by friends who live nearby and who took care of us, showing us round, feeding us and providing our boy with the perfect sofa for his afternoon nap.

And now I’ve finally been to St Ives! Years ago, when I was a rookie reporter, I went to a Sunday afternoon cake and gin party where a Canadian artist told us she’d gone on her own to St Ives by train – perhaps as a cure for a broken heart, or maybe just to dispel the blues. I’ve wanted to go there myself ever since. I wasn’t sure what our son would make of Tate St Ives, but actually he really loved the kids’ activities – lots of torches and lenses to play with.

Last time I went to Cornwall was for the July 1999 solar eclipse (ultimately an eerie experience – I won’t forget the strange cold rush of wind along the grass when the sun went dark). That was the trip that inspired the visits to Cornwall in my first novel, Stop the Clock. I still have, somewhere, the Perranporth Yard of Ale award I won on a previous Cornish holiday, in 1991.

Still on my Cornwall hitlist: Mousehole, the Eden Project, Lands’ End, the North Cornwall Book Festival (I hoped to make it this time round but it was too much to fit in), and much more… I’m also sorry I didn’t make it to the Edge of the World bookshop in Penzance and St Ives Bookseller – maybe next time!

To wind up with a mini-listicle, here are some Cornwall-set novels I’ve read and loved down the years:

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale, which is set mainly in Penzance. I read this recently and came away with the feeling that I’d been somewhere full of light.

The Camomile Lawn by Mary Wesley. One of the many things I love about this book is that Calypso marries for money and then falls in love, and firmly refuses to come to a bad end. I’m also a big fan of Patrick Marnham’s biography of Mary Wesley, Wild Mary – recommended reading for writers, especially women writers, along with Hermione Lee’s life of Penelope Fitzgerald, which I took with me on my most recent trip to Cornwall and will be very sorry to finish. Though I am also very happy to have got to the bit of the story where, late in life, she wins through to find a wide and admiring readership.)

Out of various Daphne du Maurier possibilities – Frenchman’s Creek.

The first few Poldark novels. They’re adapting them for telly again, so the books are set to have a second lease of life. I did feel for Demelza, battling it out against Elizabeth, the perfect, unobtainable first love.

Susan Howatch’s Penmarric. I read this as a teenager and it made a big impression, prompting me to attempt a family saga of my own. My opening line, written from the point of view of the hapless Casanova heir of the country estate, was: ‘I made the same mistake with Clara that I have made with every other woman in my life: first I fell in love with her, and then I fell in love with somebody else.’ I never finished it.

If anyone has any other recommendations for Cornwall reading or places to go, let me know!

my Books Are My Bag bag came too, along with my son’s autism awareness bear and Hermione Lee’s life of Penelope Fitzgerald

October 6, 2014

Steve Shirley on autism, the Kindertransport, and the most loving thing a parent can do

‘I was five when my world fell apart,’ Dame Stephanie Shirley (also known as Steve Shirley) told a packed audience at Henley Literary Festival last week. Later to become a pioneering IT entrepreneur and philanthropist, she grew up in Germany in the 1930s, the child of a Jewish father and a Gentile mother. Now 81, she attributes her drive to succeed and her need to give something back to survivor’s guilt – to having escaped and lived when a million other children died in the Holocaust.

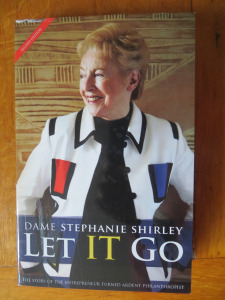

Steve Shirley’s autobiography

The family moved round Europe in search of safety as Nazism took hold, eventually settling in Vienna, where Steve’s older sister had a kind teacher who would let her leave early so that the other children would not throw stones at her as she made her way home. Then their parents heard about the Kindertransport, the organisation that saved the lives of 10,000 Jewish children by transporting them to safety.

‘It looked as if Europe was going to descend into barbarity,’ Steve explained, ‘and my parents did a very brave thing.’ They decided to part with Steve and her sister, who came to England: ‘Most of the families ended up in England because very few countries would open their doors to us.’

The children were taken in by a couple they came to refer to as Auntie and Uncle, who paid £50 – the equivalent of £10,000 in today’s money – for each child in order to be allowed to offer them a home. Once they had learned enough English, both girls were sent to school, where they did very well. Steve was so good at maths she was eventually sent to lessons at a boys’ school so that she could benefit from the more expert teaching available there.

Steve’s sister went to university and later emigrated to Australia, where she had a successful career as a social worker supporting children who had been through traumatic experiences. Steve did not go on to higher education on leaving school, however, instead deciding to find a job and start earning, and later obtaining a degree through six years’ worth of night classes. She married, but was absolutely determined to carry on working, and went on to set up a company that employed women with children, working from home, as computer programmers – 55 years ago.

‘People asked me why I should want to go on working,’ Steve said. ‘I felt passionately that I should be independent.’ That was when she decided to use a different name – Stephanie Shirley being doubly feminine, she started to sign her correspondence to potential clients as Steve Shirley. And then she started getting meetings, and the business took off.

Steve was inspired by the John Lewis model in setting up her company, and sought to give employees a stake in its success. When the venture was eventually sold, she had created no fewer than 70 millionaires – as well as undreamed-of wealth for herself, much of which she has given away to good causes.

She has set up a number of charities, including Autistica, which funds medical research into the causes of autism, a residential school for children with autism and a home for adults with autism. She has a personal reason for all this work related to autism; her only child, a son, was severely affected by the condition.

The boy who never spoke again

‘He started off as the most beautiful baby. He was lovely, and then at two and a half, like a changeling in a fairy story, he grew into a wild, unmanageable toddler. It wasn’t just the terrible twos. He was autistic. He lost what little speech he had, and never spoke again.’

At this point, there was an audible gasp of shock and sympathy from the audience, which made me wonder if some of those present had perhaps not heard before that such a thing can happen. Steve was describing a terrible experience, but not an isolated one; I have heard of autism manifesting itself in the same way with other children, though it was not the case with my son. The concept that a child who is apparently developing normally can suddenly go into reverse and become non-verbal again is a frightening one, but for many families it is daily reality and the consequences are lifelong.

Steve’s son was classed as ineducable, which used to be the standard response to a diagnosis of autism – much has changed, thanks in large part to the efforts of parents like Steve. However, Steve managed to find a school that would take him, and he was transported there by ambulance on a Monday and brought back the same way on a Friday.

She kept on working, and throwing herself into work offered her some respite from worrying about her son: ‘The only time I forgot my child was when I was working; I’m a workaholic.’ He became increasingly violent and difficult to control, and in due course had to be cared for in an institution: ‘It was a horrendous period and I ended up having a breakdown.’

After she had recovered, she began to think about how she could move beyond her own family’s problems to help others facing similar difficulties. ‘I wanted to make a difference to other families.’ She said she felt that she had made more of a difference with regards to autism than in the field of computing.

Looking back to her parents’ decision to put her and her sister on the Kindertransport, she described it as ‘the most loving thing a parent can do, to let children go to safety – though as children we experienced it as rejection.’ (Steve and her sister were subsequently reunited with their parents, but were never really able to bond with them following their separation.)

‘The most loving thing a parent can do.’ This is a phrase Steve echoed when describing, with great compassion, the pain of parents of children with autism who have reached the decision that a residential school is the best place for them.

‘When I see parents who let their children go to a residential school, I see them in tears, it’s the most loving thing a parent can do. The children need specialist training, and the pressures on the family are much too much to do any more than to contain the situation.’

Perhaps this is true of every kind of love; love is at its most powerful when it is at its most selfless, when giving something up to save the beloved. And sometimes that means letting go.

Margot Harris: ‘Change is the only constant in life’

Margot Harris’ autobiography

I first heard of Steve Shirley from a colleague who had interviewed her, and thought I would be particularly interested in her story because I, too, have a son who has autism. So when I saw that she was due to speak at Henley Literary Festival as part of a joint event with Margot Harris, who was born to a Jewish family in Germany in 1930 and also escaped to England, I knew I had to take up the chance to go along and listen.

Sitting in the serene surroundings of Henley Town Hall on a fine autumn morning, listening to these two remarkable women recall the horrific events of their childhoods, I found myself very close to tears. Margot Hemming, who still practises as a therapist – a career which she entered relatively late in life – described how she and her family hid from looters on Kristallnacht: ‘It was a mob. We lived over a menswear shop – I was one of five children – and I was upstairs and it was dark when we heard people come in looting. We all kept quiet.’

The looters didn’t realise that there was anybody upstairs and they survived the night unharmed, but later her father was taken away to Buchenwald concentration camp. The family’s solicitor successfully argued that he should be released in order to wind up his business, but was subsequently sent to a concentration camp himself. An uncle who lived in Paris managed to get the family out to England; they were meant to leave everything behind, but Margot’s parents hid some of her mother’s jewellery in little boxes which they managed to smuggle out, giving it to the children to take out to the corridor of the train when the Gestapo came by.

The family lived in the East End of London, survived the Blitz and moved to the US after the war, where Margot enjoyed a lot of parties before settling down to married life back in England, later going on to train as a therapist. Both she and Steve agreed that they could not bear to look back at news clips of the events of their childhoods, and listening to them both remembering that history from the perspective of a lifetime later, I was struck by the extreme poles of human behaviour that their formative experiences had exposed them to: the looters and the rescuers, the kind teacher and the children throwing stones.

I loved hearing both women talk about their work – especially as neither of them intend to stop any time soon. Margot said she believed it was essential to always have a project for the future, just as it was necessary to accept that change is the only constant in life. (This was a point that Steve made too: ‘Tomorrow will not always resemble today’.)

I’ve come across this strongly positive attitude to work on other occasions when I’ve met women of their generation: a straightforward, unambivalent belief that it is a good thing for a woman to have a job, one that she finds interesting if at all possible, and that she should not have to abandon it for family life, though this was an expectation and, in many careers, a requirement in the post-war years, when a woman married.

Steve observed, ‘A woman can do anything she wants these days. I remember when it was not possible for a woman to open a bank account; all those legal barriers have gone – it’s the cultural barriers that remain. We have to make sure we recognise that, and talk to men about it, and have an environment that is inclusive for people from all sorts of backgrounds.’

Steve’s comments about how her work gave her some respite from the difficulties and worries of having a child with autism chime with my own experience, and I think it is also true, or potentially true, for many other parents in the same situation. So much excellent work has been done in schools, but it seems to me that there’s still a desperate need for more suitable childcare for children with autism; their parents want to be able to both look after their families and work, as other mothers and fathers do, but this can be almost impossible without the right support.

I was very glad to have had the opportunity to hear Steve and Margot speak – it was genuinely inspiring to hear how they had survived and gone on to live such purposeful and creative lives; and it was very moving to hear them speak with such clarity about the past, and with so much optimism for the future. I shall treasure my signed copies of their books!

More blog posts about autism

The moment I found out about my son’s autism

Autism, parenting, Far From the Tree and a wishlist

Three women in the Thames: swimming for Ambitious about Autism

September 21, 2014

Reading around After I Left You: Anna’s silence and speaking out

Women’s fiction is often about choosing who to trust as much as it is about finding someone to love and be loved by in return. My new novel After I Left You is no exception, but my heroine Anna’s revelations about what happened to her in the past also touch on issues that are perhaps less often explored in the genre, and which I was determined to attempt to tackle… though also thoroughly intimidated by.

At this point I have to issue an all-caps *SPOILER ALERT* to anyone reading this who hasn’t read the book. I’m not going to unpick the fine detail of the story here, but the quotes and articles that follow will give you a pretty good idea of where it is heading – and also, perhaps, why it is such a difficult story for Anna to tell.

The newspaper and magazine articles that I’ve compiled here caught my eye not so much because I went looking for them as part of focused research, but because they helped me to understand the context in which I was working, whether I came across them during or after the process of writing the book. Yesterday I went along to talk to the first meeting of the Fe-line Book Club in Oxford and took these cuttings along with me, but in the end I didn’t share them. So, inspired by the points that came up during the book club, I thought I’d list the cuttings in a blog post, and hope they’ll be thought-provoking for readers who are looking to open the novel up for discussion.

The first Fe-line Book Club is go!! Thank you @AlisonLMercer for joining us! pic.twitter.com/85jtxFnEfq

— Fe-line (@Felinewomen) September 20, 2014

I described the novel to the readers I met yesterday as a coming-of-age novel with a 17-year time lag, and I suggested that Anna was like a Snow White figure, a woman who has been effectively frozen ever since the trauma she went through when she was 21, at the end of her time at university. She is only now beginning to come back to life, acknowledge her past and lay claim to her future.

Anna has never spoken to anybody about what has happened to her, and as she tells her story she is moving towards the point when it will finally become possible for her to break her silence. It’s a novel about what is not said and about finally finding the courage to speak out. So why is it so difficult for Anna to speak freely? Why has she chosen to cope with what has been done to her by ignoring it, avoiding it, and behaving, more or less, as if it never happened?

Breaking the silence

I read Rebecca Mead’s excellent profile of Mary Beard in The New Yorker because of the light it promised to cast on how Mary Beard has dealt with online abuse. I encourage you to read the whole article, but here are some quotes by way of introduction.

The article opens with an account of a talk Mary Beard gave earlier this year about ‘the many ways that men have silenced outspoken women since the days of the ancients’. It goes on to describe how, in 2000, Beard wrote an essay for the LRB which included an account of being raped in 1978 while travelling in Italy as a graduate student.

‘“To all intents and purposes, this was rape,” she wrote. “I did not want to have sex with the man and had certainly not given consent. If I appeared compliant, it was because I had no option: I was in a foreign city, with enough of the local language to ask directions to the cathedral maybe, but not to search out a reliable protector and explain convincingly what was happening.”‘

Beard did not report the assault, and over the years that followed her own private understanding of what had happened to her shifted: ‘She had even found herself “making sense of the incident as a much more emphatically willed part of my sexual history…”’

‘The difficulty of knowing how to talk about rape is not limited to those who have experienced it, she wrote. It is an enduring cultural problem… “Rape is always a (contested) story, as well as an event,” Beard wrote. “It is in the telling of rape-as-story, in its different versions, its shifting nuances, that cultures have always debated most intensely some of the most unfathomable conflicts of sexual relations and sexual identity.”‘

False allegations and a question about fiction

This column by Eva Wiseman, which appeared in The Observer in March 2013, quotes a Crown Prosecution Service report which found that over a 17-month period there were 5,651 prosecutions for rape, and 35 for false allegations of rape. False allegations of rape, it would seem, are relatively rare: but not so in fiction. The column cites Atonement, Gone Girl and numerous other novels and films as examples:

‘It’s a trope that exists because it’s powerful – it moves on stories and confuses the reader, and builds sympathy in a raw and painful way. It’s a plot device that works, but one that should be questioned… When real occasions of false allegations are published, they’re news for the same reasons – they’re lurid and exciting, and they make you feel something. But they’re news because they are so rare… the idea that it is a widespread problem, a weapon women use, is fiction.’

The truth and the ‘cultural script’

‘It should be a given: not a lot of us endorse the idea that a drunk woman is at least partly responsible for her own rape – but in Australia, one in five do.’

So begins a recent article in The Guardian by Jessica Reed. It goes on to say this:

‘Researchers have long pointed to a widely believed cultural script of what constitutes a “real” rape – the trope of the lone lady being attacked at night as she made her way home through dark alleys. Such a fantasy makes, one suspects, the idea of rape slightly easier to digest than the truth. But these are the facts:

The great majority of rapists were known to their victims.

Approximately half of reported sexual assaults involve alcohol consumption (on the victim’s part, the perpetrator’s part, or both)

Gendered violence is a learned behaviour upheld and reinforced by a broader social context (our family, community, a country’s cultural expectations and popular culture)

Men are less likely to intervene and try to stop gendered violence when they perceive their peers to find such abuse acceptable

Social censure (that is, public repudiation of violent behaviours and/or perpetrators) is among the most effective means of preventing violence’

‘A learned behaviour upheld and reinforced by a broader social context’… For more about how such learned behaviours can be changed, see the TED talk by Jackson Katz about preventing sexual violence and domestic abuse.

Fiction. Cultural script. Popular culture.

The stories that we tell each other matter. What do we find truthful? What are we willing to believe? And who are we willing to listen to?

August 11, 2014

Book group questions for After I Left You

about to set off for the launch party

After I Left You is out there! The launch was held last week, on a beautiful moonlit evening in the garden at Mostly Books in Abingdon (you can read about it on the Abingdon blog). Now it’s on the shelves at independent bookshops, Tesco and Sainsbury’s, and is also available from Amazon. In a couple of weeks’ time I’m due to do my very first book group talk about the book, with the book group at work.

I’ve had a think about questions that might be helpful for book groups who want to discuss the novel, and here they are. I don’t think there are any spoilers here, but you might want to wait until you’ve read it before you look through them – they will definitely make more sense then!

If you have read the book, I’d really welcome your thoughts. Do let me know if there are any other questions that you think would be useful, and if there are any you would particularly like to discuss with other readers – and also, of course, I would be very interested to know your responses!

If you’re in the Oxford area and your book group is going to be discussing AILY and you’d like me to come along and talk about the book, post a comment to let me know and let’s see if we can sort something out. Also, plans are shaping up for an event in north London next month – details to follow.

After I Left You on the Book Buzz shelf in Mostly Books

Discussion questions for After I Left You

What was your reaction to what happened to Anna on the night of the ball?

What are the fairytale elements of Anna’s story? What, or who, makes the fairytale go wrong?

Do you think it is possible to stay with your first love? What would happen if you bumped into your first love in a bookshop one day?

How are the different friendships in the story represented?

One of the key friendships in the novel is Anna’s friendship with Keith. How would you describe this friendship?

What other novels spring to mind that include a portrayal of a friendship between a man and a woman?

Who leaves who in the book? Which characters make peace with each other, and what does it take for this to happen?

By the end of the novel, what change has Anna experienced? How is she different to the beginning of the novel?

lucky nail varnish ready for the launch – wore it for my Thames swim too!

Three women in the Thames: swimming for Ambitious about Autism

The moment I found out about my son’s autism

Women writers who changed my life: Enid Blyton to Antonia White

August 1, 2014

What makes a great love story?

a romantic rose… plus thorns

‘Reader, I married him.’ A great love story can end that way, but only after a load of trouble. As we know from Shakespeare, true love involves a rocky ride, in literature at least. A compelling romance must have drama; someone, or something, has to oppose it and try to stop it happening. And in a truly great love story, the threat to the lovers has to appear insurmountable. We want to believe that love can conquer all, but at some point in the story, it has to look horribly likely that love is going to lose.

In John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars the stakes are sky-high from the outset; the forces ranged against the young lovers are depression, loneliness, illness and death. But that doesn’t stop the spark between them at that first meeting. If anything, it intensifies it.

True love is stubborn to a fault, and flourishes in the face of poor odds. It is also not sensible, convenient or rational. I can understand why Charlotte Lucas accepts Mr Collins’s proposal in Pride and Prejudice, I can even admire her pragmatism, but nobody would dream of describing their relationship as a great love story.

True love changes the lovers; in a really great love story, there will always be a transformation (or several). Take Romeo, who is teased by his friends at the beginning of Romeo and Juliet for moping around and pining for someone who isn’t even interested in him. He believes himself to be in love, but he doesn’t really know what it is. Then he meets Juliet and – kapow! – he is no longer a self-indulgent boy.

He is also no longer unrequited. Great love stories are never one-sided; there may be spells of confusion and separation and alienation – in fact, there almost certainly will be – but ultimately, the lovers will find some kind of equilibrium, even if this is only possible when they have lost their lives (think Wuthering Heights). They might not start off as equals, at least not in society’s eyes, but they have to end up that way, from the reader’s point of view if not the world’s.

Sparring, rivals and secrets

Jane Eyre is one of my favourite love stories, and had such a big impact on me that it crept into my very first novel, which I wrote as a child, without me even realising it. My story featured a burning house and a first wife tucked away somewhere, and it ended with a wedding. (I hope it’s not a spoiler to note that the quote at the beginning of this post – ‘Reader, I married him’ – is Jane’s.)

the end of my first novel

Jane is Rochester’s employee and his social inferior, but she is not about to let him get away with anything. This leads to a fair amount of sparring, which he seems to quite enjoy – they are clearly comfortable with each other – but a series of increasingly deadly threats rise up to force them apart. Jane has a love rival: the beautiful, wealthy and heartless Blanche Ingram. And then there is the madwoman in the attic, and the revelation that forces Jane to flee. Lovers do not keep secrets from each other; any attempt to keep the past locked away out of sight is an enemy to love.

In After I Left You, my new novel, Anna last said goodbye to Victor, her university boyfriend, seventeen years ago, and she has never told him the full story of the chain of events that led to her decision to cut off all contact with him. Something has silenced her, and she has lived a kind of half-life ever since.

When they meet again, her old feelings for him begin to return; but if she is to seize her chance of happiness, she is going to have to make the leap of faith that is always part of love, overcome her fears, give up her secret and speak out. Where there’s love there’s hope, and in any love story there is the possibility of transformation, and a question to be answered: will they or won’t they come together in the end?

A version of this post first appeared on the Diana Verlag blog. Diana Verlag is the publisher of the German edition of After I Left You.

Cover © t. mutzenbach design, shutterstock

July 23, 2014

After I Left You, nostalgia, old flames and the power of secrets

After I Left You fresh from the printers

Some years ago, standing by the buffet at a family occasion, I witnessed a brief encounter between a middle-aged woman and an old flame. As they turned towards each other they both seemed to soften, and although the years didn’t quite fall away from them, it was possible to glimpse their younger selves.

I didn’t know anything about the history between them, but then, I didn’t really need to. It was a public moment that was also very private; it was quite clear that whatever was involved in that exchange was none of anybody else’s business.

Inevitably, the time came for them both to move on, and be reabsorbed into the social scene going on all around them, with its greetings and small talk and introductions and catchings-up; and it was almost, but not quite, as if whatever had passed between them had never been.

The hideous lilac bridesmaid’s dress

At the beginning of my new novel, After I Left You (out July 31), Anna, the heroine and narrator, has a similarly poignant conversation with Victor, her first love. Their paths cross in a London bookshop. She is not looking her best, having come in to shelter from the downpour outside; she is drenched, her hair is dripping, and she is carrying a hideous lilac bridesmaid’s dress over one arm. They talk, briefly, and part with much left unsaid.

The past may be behind us, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone for good.

For Anna, this meeting does more than stir up memories of love. She hasn’t seen Victor for 17 years; she cut off all contact with him and their group of friends from university when she left. He reminds her of times she would rather forget and the secret she has never told him, and she is not at all sure that she is ready to face up to the past.

But try as she might, she can’t keep away from it. Before long her story jumps back to the early 90s and she is eighteen again, arriving at university and meeting Victor for the first time. The novel moves between two timelines – her student days and her present – and gradually reveals exactly what it is that Victor doesn’t know.

at my writing desk

Back to the 90s…

That’s part of the power of secrets. Truth has a way of burrowing up to the surface, and a revelation can break down the distinction between then and now, and bring what happened years ago right into the spotlight of the present. The past can change us and change with us. It may be behind us, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone for good.

I’ve always loved the idea of time travel, and until someone finally invents a suitably modified DeLorean for real, novels are the closest we’ve got. Like Anna, I was a student in the early 90s, when it still seemed yuppie to have a mobile phone, only geeks had email and you left messages for people on a sheet of A4 blu-tacked to their door. (Very public.)

The Conservatives seemed to have been in forever, pub interiors were havens for smokers (and there were many of them), ciabatta and cappuccino were sophisticated novelties and if somebody made you a mixtape you knew they really liked you. It increasingly seems like another world, and working on After I Left You gave me the chance to revisit it.

When I was a student: my 20th birthday

I have since had the strange double experience of walking into a scene that I had already written about from Anna’s perspective. Earlier this year, I went to a college reunion. Mine was much less dramatic than Anna’s. There was no Hollywood glamourpuss having an illicit fag in the ladies’, and nobody ostentatiously flirting to provoke an ex-spouse, sobbing in the chapel, or dodging a confrontation in the bar. (Not as far as I know, anyway. I left at midnight.)

But, like Anna, I did find that in some ways twenty-odd years really don’t make a lot of difference. Everybody’s younger selves were still there, and became more visible the longer you looked. It was a vivid reminder that the past is always out there somewhere; chances are that sooner or later, whether you seek it out or not, you’re going to walk right into it.

off to a college reunion