Issandr El Amrani's Blog, page 10

January 17, 2014

Egypt's Good, Bad, and Ugly

Interesting argument by Hisham Hellyer in Foreign Policy, on what the outside world might do to nudge Egypt towards a resolution of its crisis:

Bilateral attempts by the United States to engage constructively with the Egyptian authorities do not have much hope of success in the short to medium term, and perhaps even in the long term. A multilateral one, however, may. An effort that involves the United States, as well as countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and European Union member states, may have a different outcome. The "War on Terror" paradigm the authorities are operating within is ultimately not a source of stabilization for the Egyptian state. The repercussions of it, as they intensify, have knock on effects on the economy and civil rights in Egypt. It will take a special kind of conglomerate of countries to constructively advise Egypt on these issues, without being ignored or dismissed.

Whether there are takers on the GCC side for this approach right now is dubious. But if/when Egypt's situation does not improve, they may change their mind.

Known Unknown: Why the Egyptian Referendum is a Black Box

Interesting observations by Matt Hall for the Atlantic Council on a question nagging many – the quality of observer missions in the Egyptian referendum. Worth reading the whole thing, but here's the bit that clarifies the question of whether or not this referendum process has been less or more transparent than previous electoral events:

Al Ahram reports that approximately 5,000 Egyptians were slated to observe the referendum—a very small number considering there are upwards of 30,000 polling stations. Not enough, for example, to observe if the overnight seals on ballot boxes were unbroken while in the custody of the military—or to keep a keen eye on voter registries—as was standard practice in past elections.

Part of the explanation for the reduced ranks of poll watchers is that, unlike in previous elections where the bulk of observation was shouldered by party agents, for this vote the High Electoral Commission barred party agents under the specious rationale that the constitutional referendum was not a political party contest—despite the fact that political parties have been instrumental in campaigning, advertising, and mobilizing for the vote. On top of this, many of the experienced domestic groups with national networks decided to sit out the referendum owing to the overall oppressive environment, or had trouble securing government permissions. For example, the group Shayfeenkum (“we see you”), which has observed Egyptian elections since 2005, reported 60 percent of their applications were refused. And, of course, observation groups affiliated with the FJP have been banned since the government declared the Muslim Brotherhood, from which the party stems, a criminal organization.Of the domestic groups observing the referendum, most have limited reach, resources, and technical proficiency. The only group that pledged to field a nation-wide observation mission, Tamarod, has no prior experience in the technical aspects of observation. Moreover, as the progenitors of the June 30 revolution that this election is meant to secure, their professional objectivity is suspect. Indeed their campaign spokesperson declared the objective of the group’s electoral observation is to prevent “schemes by the Muslim Brotherhood.”

In addition to gleaning information for a national audience, domestic observers serve as essential antennae for international observer missions, who are always far less knowledgeable about local conditions. For better or worse, the statements of international missions often are taken as the final word on an election in international media and foreign capitals, and the veracity of these statements depends in large part on quality partnerships with local actors.

The referendum has clearly been, to say the least, problematic since both people campaigning for a boycott and those campaigning for a "no" vote have been subjected to arrests, access to state and private media has been extremely imbalanced, and the overall political context is a highly repressive one. As a result, part of the debate over the referendum has been whether it tells us anything of use. You could break down the debate in the following way:

Triumphalist: Those like the government, its supporters and most of the Egyptian media who see the results as a triumph for Egypt, a blow to the Brotherhood, an endorsement of Sisi and an affirmation of the roadmap.

Pragmatic: Those who see the referendum as revealing genuine popularity of Sisi and public support for military, and that even if undemocratic or populist it is a reality that foreign observers, disappointed revolutionaries and others need to understand. These stress the decent apparent turnout to point out that a large number of Egyptians do support the current regime, like it or not.

Skeptical: Those who see the referendum as largely meaningless due to the impossibility of campaigning for a boycott or "no" vote, and the overall repressive environment and hysterical press. In essence, while the referendum is being used for propaganda purposes, it tells us little about Egypt's political realities aside from that the army is powerful. This has been a dominant response among Western analysts, much to the ire of some Egyptians.

Rejectionist: Those, mostly from the Anti-Coup Alliance, who see the referendum as illegitimate and its results and turnout figures as rigged. The MB has for instance claimed that the turnout was only around 10%, rather than the 36% or so from official preliminary results.

The first and the last position clearly appear to be out of touch with reality. Caution would lead one to side with the skeptical view, like the above article, but the pragmatic argument is also worth noting. Even if unreliable as a test of where popular opinion stands, it is pretty evident that there are many Egyptians who back the current state of affairs, just as it is pretty evident that there many who are not happy about it. The combination of repression and outright electoral fraud (in the case of not allowing people to campaign as they wish if not in the polling stations and vote counting rooms) should lead us to dismiss this referendum as a reliable indicator of anything but the regime's ability to put mobilize a sizable constituency and put on a show of self-legitimizing pageantry.

Springborg on Sisi

“He’s going to give them ‘Islamism light,’” said Robert Springborg, a Middle East expert from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. “That’s what they want, and that’s what they are going to get.”

— "Army chief said to be focused on Egypt’s problems", AP

January 16, 2014

Links 23 December 2013 - 17 January 2014

Happy new year, I guess.

Dans l’oasis du Fayoum, au sud du Caire, les Frères musulmans rasent les mursTraining Fighters of Future Across Gaza - NYTimes.comDoes Egypt’s Vote Matter?Ursula Lindsey on what the referendum signifiesDemocratic Republic of Zamalek

"Our official language will be a magical hybrid of Arabic, English and rural Filipino"Summary Of Egypt Aid Limits In The Omnibus Appropriations Bill

Handy rundownA Recipe for Civil War? [PDF]

FRIDE's Kristina Kausch compares Egypt and AlgeriaLive updates: 98% of votes in 25 governorates in favour of draft constitution - Politics - Egypt - Ahram Online

Egyptian news site estimates approval rateRumour and referendum in Egypt: Staying on side | The Economist

And another great one from Max RodenbeckVoters come out after Imbaba blast | Mada Masr

A good story from Sarah CarrKeep Pollard Behind Bars - NYTimes.comEgypt’s Quest for Itself

Peter Harling and Yasser El Shimy.De hauts gradés du DRS mis à la retraite

More sidelining of old guard in AlgeriaHey General, It's Me, Chuck. Again. - Shadi Hamid - POLITICO

Hamid argument based on (false) premise that US cares.Egypt’s phony democracy doesn’t deserve U.S. aid - The Washington Post

Post Op-Ed.From the Potomac to the Euphrates » Do Not Run, al Sisi…Do Not Run

Steven Cook makes his case.Armed institutions in Egyptian constitutions - Al Jazeera English

Omar Ashour on the Egyptian army's moves against democracy in 1952Exclusive: With Muslim Brotherhood crushed, Egypt sets sights on Hamas | ReutersShould We Cut Off Egypt Aid? Ask AIPAC - The Daily Beast

Israel and friend working hard to defend Egypt aid.It’s better if Al Sissi stays on as Egypt's army chief, says Mohammad Bin Rashid

Big deal this is made public?Civil war turns Syria into major amphetamines hub

Also the case in Libya - mix of young men, drugs and guns...Sisi…Egypt’s president in 2014 | Cairo Post

Good example of the kind of fawning "Sisi will save us" op-eds we can look forward to many more ofFun with facts | Inanities

Thank you Sarah Carr for tearing to bits supremely disingenuous WSJ column (and others)Ariel Sharon’s burial plot set to displace 15,000 Palestinians | The Pan-Arabia Enquirer

"It's what he would have wanted."Egypt’s unsustainable crackdown | European Council on Foreign Relations

Urges EU to think long-term, grow balls.Algérie | Ramtane Lamamra : "L'Histoire nous donnera raison" | Jeuneafrique.com

DZ FM refuses to discuss Morocco.Egypt’s Salafist official: ‘Courts decide who are the terrorists’ - Al Arabiya NewsLegitimizing an Undemocratic Process in Egypt - Carnegie

Michele Dunne.Egypt’s Counterrevolution - NYTimes.com

Missed this op-ed by Sara Khorshid.Burglars Who Took On F.B.I. Abandon Shadows

As young activists, they unveiled FBI spying, blackmailing of civil rights and anti-war groupsCrushed to death: Palestinian man dies at overcrowded West Bank checkpoint | MondoweissThe Controversial Death of a Teenage Stringer

Teenage Syrian photographer working for Reuters is killedThe Muslim Brotherhood takes its case to the International Criminal Court

Accuses regime of murder, torture, disappearances, persecutionAhmed Maher, Jailed Egyptian Activist, Describes Prison In Smuggled Letters

Unbelievable that this man is back in prisonEgyptian Chronicles: The Return of the #NDP RascalsAfrican migrants in Israel protest in Tel Aviv

Against a law that allows them to be detained for a year without chargesAt al-Azhar University « LRB blogSelling a constitution | Mada Masr

Anonymous Egyptian businessmen finance get-out-the-"Yes"-voteThe Israeli Embassy's Extension

Good BBC comedy sketchThe Muslim Brotherhood, Back in a Fight to Survive - NYTimes.com

Great reporting on MB adaptation.The Egyptian army collects billions in government contracts

Just in the last few monthsAl Sa’eh Library in Tripoli Before It Got Torched

80,000 books may be lost

January 15, 2014

Africa if it had not been colonized

Detail from a lovely map of Africa if European colonialism had not occurred, as imagined by Nikolaj Con, via WaPo. Some other interesting Middle Eastern maps there too. Click on the excerpted crop for the full map.

Khaled Fahmy on Egypt's constitution, al-Sisi, and more

A balanced and well-informed BBC interview of historian Khaled Fahmy.

January 14, 2014

US aid and Egypt: back to business as usual

Josh Rogin, reporting for Daily Beast, says the path is now clear to restore US aid to Egypt to its full level. Here's a quote from Michele Dunne that pretty much sums it up:

“I think there’s a sense of giving up on Egypt [inside of the Obama administration], on the Hill as well,” said Dunne. “There’s a sense that ‘Oh well they tried a democratic transition, it didn’t work, but we don’t want to cut ourselves off from Egypt as a security ally, so let’s just forget about the whole democracy and human rights thing except for giving it some lip service from time to time.’”

Also see this report from Ali Gharib on the crucial role Israel and its US lobby played in mustering Congressional support for this.

Last summer, the language on draft bills from the House and Senate on Egypt suggested a substantial reduction in aid and/or the linking of the aid to various requirements, and also threatened to drop the usual waiver the administration could exercise. Now, the administration is only required to certify that Egypt is maintaining good relations with Israel. The path is clear to restore the aid, and the bilateral relationship, to its Mubarak-era level.

January 13, 2014

The Arab world into the unknown

Our friends Peter Harling and Sarah Birke contributed the following piece, a reflection on the state of the Arab world after a confounding 2013 that saw, for many, the dissipation of the enthusiasm of the 2011 uprisings. Harling is Senior MENA advisor at the International Crisis Group; Birke is a Middle East Correspondent for The Economist.

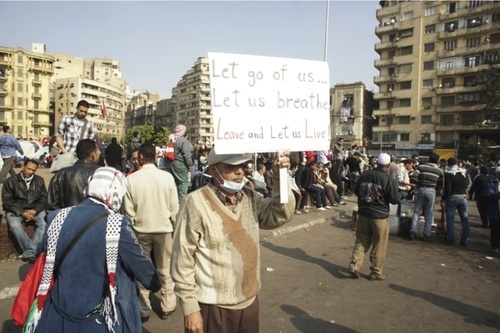

Two and a half years ago, Arab countries were abuzz with interesting conversations. Rich and poor, old and young, villager and urbanite, Islamist and secular all had their own take on the bewildering turmoil of the uprisings they were caught up in. They tended to be aware of the risks, hopeful that change was both inevitable and ultimately beneficial, and proud that the region could awaken and, after centuries of foreign interference, set its own agenda. Opinions were also invariably sophisticated, with people speaking profoundly about societies they thought they knew and had started to reassess.

This was a refreshing change from the pre-2011 tune of impotence. The region at that point, as its inhabitants saw it, was hostage to ossified regimes, intractable conflicts, worn-out narratives, and crumbling economies – not to mention Western hypocrisy, and schizophrenia, about urging client regimes to reform. Sterile agitation on the regional or international front, notably around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, distracted from thorough stagnation in domestic politics. Commentary was a cyclical run through the latest episode of violence, round of sanctions, realignment of alliances, or half-hearted diplomatic ventures. Uninspiring solutions to lingering problems left citizens reluctant to choose, among players in this game, the lesser of evils. Standing up to the US (like firebrand Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad) or surviving an Israeli assault (as Hezbollah did in 2006 and Hamas in 2009) could certainly make you popular beyond your traditional base, but not for long.

Less than three years after popular protests streaked across the Arab world, conversations appear to have come full circle. Optimism that societies in the region could no longer be ignored and would bring about change has reverted to doom and gloom. Outside observers have jumped from one label to the next: Arab spring to Islamist autumn to reactionary winter. All-too often, local residents view protests as a conspiracy, a naïve illusion or an ill-fated hope at best. Many see a stark choice between a failing old order and hegemonic Islamist rule—or war, as in Syria. Opinions are generally crude, aggressively intolerant and more rigid than ever. Interlocutors sport surprisingly definite conclusions about their home-region, no matter how fluid and contradictory the current trends actually are.

If commentary appears the same, events on the ground are not. On a domestic level, the region’s people remain more assertive than ever. Dissidents, both Muslim Brothers and liberals, have shown they won’t give up in Egypt, where they have spoken out against new laws banning protests and constitutional drafts allowing military trial of civilians. Syrians, despite the chaos in their country, talk openly about what they want, challenging both the regime and the opposition. Tunisia remains a place where parties are being forced to seek some sort of compromise. The environment in which this is happening has been transformed, too.

At a regional level, Iran has assumed a more overtly sectarian policy, which Tehran had hitherto tried to avoid; the so-called ”axis of resistance” to Israel is detached from any major Palestinian faction; Saudi Arabia has opened a front not only against Shiites, but Salafi Jihadis and Muslim Brothers, leaving it largely divorced from the Islamist scene it aspires to lead; Syria is no longer a player but an arena for others to compete in; Israel is only rarely accused of joining the scrum. The most noticeable change to the international environment is the US’ relationship with the Arab world. Rather than grab on and take advantage of change of the sort the US has long called for, the superpower has focused on negotiations with Iran and a push at the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, leading to strange shifts in its links with the region. It failed to define its interests in the Syrian context, missing out on what for decades was considered the prize of all regional struggles. It has allowed its relations to wane with its principal Arab partners, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. It has moved towards rapprochement with Iran, a foe since 1979. All told, the Arab world is still at the start of a period of domestic, regional and international flux.

Rising costs of instability and stability

It is easy to understand why people feel that the revolutions have changed nothing. Today the region’s inhabitants find themselves in a worsening predicament. The costs of the last three years of tumult are real and rising. This explains why they put faith in narratives that rationalise events in ways that do not do justice to the scale and persistent nature of change, but provide psychological comfort. Old thought patterns offer the poise that events have shaken. Change in itself is now seen as a risk not worth taking while stability and security have become the number one goal. But, this, the only thing the old order had to offer, is now unattainable: Egypt continues to impose a curfew in the Sinai as its army deals with a low-level insurgency. Libya is growing more lawless by the day, as the recent kidnapping of the prime minister and deadly clashes in the centre of Tripoli and Benghazi showed. Nostalgia for the days of repressive regimes has surged, nowhere more so than in Cairo where general Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, the army chief and minister of defence, is heralded as the demi-god of “a Pharoahnic people”. In other places such as Saudi Arabia, Gaza or Jordan, citizens resign themselves to their current rulers.

This has led the Arab people’s desire for dignity and feeling of empowerment to turn into a sense of apathy. Political actors have fallen back on behaviours that are caricatures of their pre-2011 policies. In Algeria, the regime meets creeping threats and rising expectations with nothing less than the political embalmment of ailing president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who is set to run for a fourth term in April despite being incapacitated by a stroke last year. The Syrian regime, which now rules over rubble, has nothing else to offer than more Bashar al-Assad. Hizbollah will do anything to save him in the name of fighting Israel, even if every measure it takes actually weakens it on that front. Saudi Arabia is throwing money at problems in Syria, Egypt and elsewhere. Israel and the PLO have another go with a peace process that is along predictably unworkable lines. Egypt is desperately trying to revive the spirit of the 1952 military coup that founded the Republic, although the social contract it embodied has fallen apart.

Radical change has proven prohibitively costly in numerous ways: bloodletting, social breakdown, economic slump, eroding institutions, fading borders, plummeting morale. Many of the problems that originally fuelled the uprisings, such as unemployment, rapid and haphazard urbanisation, a widespread sense of disenfranchisement and humiliation, distrust in the political establishment and unaccountable security services have paradoxically been exacerbated as a result of the turmoil they originally triggered. But the unambitious aim is to preserve the status quo and muddle through—uninspiring as well as increasingly high-priced, albeit in the longer-term.

Much-needed, cautious reform programs embarked on before the uprisings are today being reversed. Some countries are enlarging their creaking bureaucracies to buy social peace. As investments generally decline, the informal sector is playing an ever-growing role compared to the formal across the region. Those countries that are doing better, at least in terms of stability, such as Algeria or some of the Gulf monarchies, are resorting to well-oiled bad practices—populist redistribution, subsidies and cash hand-outs that do little to redress the underlying issues. For example, when the uprisings of 2011 got underway, rather than give more political space to opposition parties that pose little threat to those in power, the Algerian government raised salaries and launched a program to give money to anyone under 35 with a business plan, or the appearances thereof.

Tentative political openings, as occurred in Morocco and Jordan, have all but been aborted now that the fear of collapse appears sufficient to hold countries together. Virtually everywhere, the stability agenda is empowering security apparatuses whose behaviour has, on the whole, worsened. They are bolstered by a popular desire for stability that depressingly echoes the argument long used by the region’s dictators. Tellingly, 2013 saw much worse repression of dissent than 2011 did. And Syria, ominously, tells everyone that no amount of violence against one's citizens is beyond the pale.

So the region has not changed quite as much as we expected. Underlying structures remain and in some cases negative features of these societies have been reinforced. These include stale political cultures that continue to decay; corrupt and brutal security forces; conflicts between rural and urban populations, the capital and provinces, rich and poor, religious and secular, old and young, not to forget sects, tribes, ethnicities and parochial identities. Women have not gained despite playing a vital role in all the uprisings. All told, the "youth revolutions" are in part giving rise to a new wave of talented people leaving in despair, exacerbating the region’s brain drain. The pre-existing trend of Christians departing from the Middle East has picked up pace. Geopolitical strategies are shifting, but remain more of an obstacle to change than a vector of transformation, continuing to act as a distraction or excuse for those threatened by any alternative to the old status-quo.

Hosni al-Zaim, who led the first Arab military coup post-World War 2 in 1949. From unknown archive.

--> -->--> --> -->

The change that was

The Arab world is paying the price for a wretched twentieth century; obstacles are deeply entrenched in the region’s history and geography. The last century started with an appetite for revival, emancipation, empowerment and modernity similar to what we witnessed in 2011. But Western imperialism would have it otherwise, with European powers and the US saddling the Middle East with their proxies and clients. Through support to the Zionist vision of building a national state in Palestine, it led to a parachuted "Jewish issue" after centuries of relatively functional religious coexistence (albeit one in which a Jewish aspiration to found a nation could find no expression). Legitimacy in the region became externalised, a function of outside support, regional rivalries and the conflict with Israel rather than stemming from domestic support.

With the mid-century military coups and concomitant emergence of leadership cults centred around a saviour or father of the nation, legitimacy became personalised, creating a troubling political culture that bedevils the region to this day. When wealth flowed from oil, legitimacy was monetised. The growth of Islamist movements as alternatives to failing republics and monarchies gave regimes a domestic threat to play up as they repressed their societies. The century ended in political bankruptcy. Legitimacy boiled down to a threat: the status quo or the promise of chaos. Today Tunisia and Yemen are the only countries where there is any sign of an attempt, however tentative and fragile, to renew the political culture. Elsewhere, that pledge stands fulfilled.

The region’s countries are all struggling to deal with a source of genuine change that is less visible and dramatic but equally as important – and which was happening long-before 2011: the evolution of societies. These societies have modernised remarkably. Over a century, people have moved into cities, improved their levels of education, developed new patterns of consumption, and are connected to the outside world through modern media. Their sense of self is more complex, ambivalent and confused than the peasants and elites of old. We have therefore witnessed some of the same kind of evolutions as elsewhere in the world: the rise of individualism, cynicism vis-à-vis ideologies; and a drift toward identity politics.

Very little of this change is reflected in the region’s political systems. They offer virtually no representation or redistribution to the broad urban constituencies that emerged from the rural exodus, although this migration erased much of the cognitive and geographical distance that separated them from the elites. As ruling parties decayed, power became vested in ruling families and their minions, floating above the people, rather than rooted in their midst. Regimes both profoundly corrupt and ideologically bankrupt hindered individual fulfilment while outlining no collective ambition. Pluralistic societies where secondary identities were expressed more forcefully as the nation-state concept receded were contained through divide-and-rule tactics, when devolution and regulation were needed. Only the security forces showed any form of modernisation, as technology increased the breadth and depth of their reach. But this only improved the rulers’ ability to dominate and diminished their urge to evolve.

This disconnect is the backdrop to the discontent in 2011 and subsequently. It now has to be addressed both in countries that are undergoing dramatic conflicts and others that have been spared so far. Real stability will only come once that connection is restored, rather than the temporary stability attained by parking tanks in streets on a Friday when protests spill out after Muslim prayers, imposing curfews, repressing dissidents and waving the red flag of impending chaos. Put simply: political systems need to be sufficiently in sync with their own societies. That doesn’t necessarily entail a democratic system, but one that does cater for its people’s needs for participation and redistribution.

But that is more easily said than done. The traditional elites are fearful of change, perhaps now more so than pre-2011, and do not appear to have this in mind. Medium-term survival is trumping long-term vision; their obsession with preserving their ascendency open-endedly is plunging their countries into the abyss. Their best argument is that the emerging elites, who could only be Islamist, are part of the old paradigm and have proven to be as power-hungry and inefficient as their predecessors. The old fallacy of stability is holding back the need for trial and error, however cautious. This bodes badly for the future. Cycles of discontent will likely repeat themselves, with the costs and barriers to change increasing each time.

Mural on US Embassy, Tehran. Shutterstock

Chaotic transition within chaotic transition

The transitions are both set amidst and impacting an international setting in flux, which in turn can create further obstacles or allow societies more room to explore. The uprisings suggest the region is being orphaned, thanks to a mixture of the West’s reduced ability to shape events and its lack of desire to do so. NATO’s military intervention in Libya revealed the West’s lack of broad legitimacy and available resources: intervention was limited and Libya has now been left to muddle through. The endless, escalating tragedy in Syria has taken the trend even further. Diplomats have disingenuously focussed on unrealistic goals, calling for al-Assad to step down, or now pushing for peace talks, regardless of whether conditions are propitious or not and without wanting to play any real role in matching the rhetoric with action. It beggars belief that one of the worst conflicts in the region, – one that impacts into many traditional American and European interests – has failed to evoke any credible response, or worse, intelligible policy.

In particular, as said, a fundamental change has occurred in Washington's relations with the region. Thanks to a combination of the trauma of recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and subsequent isolationism, the strategic pivot toward Asia, the shale oil and gas revolution that has diminished the relevance of Middle Eastern energy producers, and inward-looking domestic priorities, America is narrowing down its interests in the region. The Obama administration has delineated two areas to put energy into: improving ties with Iran, both toward and through resolution of the dispute over its nuclear capabilities, and another push at the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks. In pursuing welcome but risky talks the US has shown unusual willingness to ignore Israeli lobbying against engagement with Tehran, as well as consequences for other allies like Saudi Arabia, and the fallout of further Iranian empowerment on places like Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. If that trend were to continue, we might expect an American posture in the region that would look as if turned on its head.

The US isn't leaving the region in the sense that it is withdrawing all its assets from it. It will continue to devote considerable resources to securing oil and gas routes, notably in the Gulf, because failing to do so could create instability that would affect the global economy and therefore the US. But it is giving every indication that it seeks to rid itself of most other responsibilities it got entangled in. It is proving as unreliable a partner for its longstanding state allies (dropping President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, criticizing the Khalifa dynasty in Bahrain, and now estranging Saudi and Israel) than it has been for its more transitory non-state ones (the Palestinian Authority, March 14 in Lebanon, or the Iraqi tribal "sahwa"). But it has not swapped them for new allies aligned with its interests, i.e. democrats in Egypt, the opposition in Syria. Instead it accepts the status quo—in Egypt’s case, the military.

For now, US aloofness and mixed signals have spelled significant mayhem. Friends are baffled, left to their own devices and having to improvise hectically. A clear example is Syria where the US contracted out to Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar the task of dealing with the armed opposition, and now seems keen to withdraw further. Foes such as the Syrian regime, Hizbollah and the Iranian Republican Guards are equally perplexed, tempted to overreach in the absence of a clear US point of reference that has served in recent decades—for better or worse—to structure the regional balance of powers, whether by securing the Gulf, pushing back on Soviet designs, negotiating peace deals with Israel, or containing alleged “rogue” states. New players have jumped into the void, adding to the confusion more than producing decisive outcomes. Syria – which has fallen victim to a mix of Iranian hubris, Saudi adventurism, Qatari ambition, Russian obstructionism and French brinksmanship, not to mention its own leadership and a host of other complicating factors – best encapsulates this state of affairs.

The international environment in which the region is evolving is undergoing a chaotic transition, too. The international order has changed as we move out of the unipolar, post-Cold War world. This has proved an obstacle more than an opportunity. The UN is malfunctioning even by its own standards, as shown clearly over Syria where Russia has not just pre-empted Western interventionism, but vetoed the most benign, humanitarian resolutions. Fragile international norms are eroding, because the Western-dominated international system that articulated them is stalemated. The prohibition of chemical weapons (whose repeated use in Syria ultimately benefited the regime), international humanitarian law, international justice, and concepts like the "responsibility to protect" increasingly appear like losing battles. Regional organisations are largely impotent. Emerging players challenge the existing order but for now do little to build a new one.

The framework is therefore a mixture of gridlock and vacuum. There are no broadly appealing ideologies, in the east or west. Economically, Western capitalism—a frequent substitute for failing political paradigms—is in crisis. In many quarters, once again apathy towards political engagement is growing, manifested in part by a retrenchment into one’s immediate community, isolationism, or virulent nationalism. People are trying to navigate the economy and society for individual survival rather than big ideas. Democracy is being tested; populism is order of the day. Modernity is bringing an identity crisis to the region as it has elsewhere. The role of Islam, which for a century has been perceived by many thinkers and citizens around the Arab world as a solution to all its ills, remains ill-defined and on trial. As a reaction, in many quarters Islamic ideology is becoming more assertive, less open to change and ever less likely to provide a fruitful structure.

In theory the flux offers opportunities. In practice it is difficult to minimise the costs and optimise the benefits. Of course revolutionary change everywhere is messy and takes time, and is unclear at the point of change whether it will succeed. Reading a book on the French revolution while sitting in today's Arab world is an eerie experience: almost everything seems contemporary and familiar, over two centuries later and in a very different part of the world. In both cases, and unlike revolutionary episodes in Russia or China, the confusion is made worse since there is no clear narrative, model, or vision. Most people know what they want freedom from—oppression in one form or another—but not what positive attributes that freedom should have.

Protest in Tahrir Square, Cairo, 2011. Photo by Issandr El Amrani.

May good things come to those who wait

But the authoritarianism and malaise of the current period is not the same as that prior to 2011. First, the region has an unprecedented level of awareness. Although its people do not feel able to change anything, all that is changing is doing so in visible ways. The utter incompetence of traditional elites, the vacuity of promises of reform, the final collapse of long-eroding social contracts, the pluralistic nature of societies, the exclusionary character of their political representatives and sectarian instincts are just some of the things on display. People feel confused mostly because they do not want to see realities, not because the region remains as opaque as it once was. Issues are discussed openly, if aggressively. In this sense, a public space has appeared and widened; and no amount of repression seems to be bringing it to a close.

Second, the silver lining to the many low- and high-intensity conflicts is that many of them, suppressed for years if not decades, had to play out. Not all will find solutions, let alone lasting ones, but some will. This may offer a refreshing departure from an increasingly intricate and intractable set of deadlocks the region has hitherto found itself hostage to.

Third, in this context, the challenging, slowly and painfully, of all the old narratives—pan-Arabist, nationalist, various shades of Islamism, anti-imperialism, “the resistance”—is ultimately positive because none of them work. They are used reflexively to fill a vacuum, to cover up for a lack of program, vision or ethic, and they are constantly belied and undermined by reality. Events, in a sense, are calling every narrative's bluff.

Fourth, the region is emerging from a century in which a succession of European imperialism, the Cold War and US hegemony denied it any genuine opportunity to define its own future. It is only just beginning to realise it will have to sort out many of its problems by itself. In 2010 US soft and hard power had reached its nadir after a decade of disastrous war on terror. Foreign interference has left a legacy that will continue to bear down, and meddling from outside will not end entirely, but the trend points toward a more autonomous Arab world. There again, this promises to be slow and painful, but opens up a whole new horizon.

This may be aided by the region’s generational shift. The youth may not always be as reformist as one would like to think of them—the Lebanese ability to follow in their forebear’ petty footsteps is a sad reminder of that. But today’s generation was born as all political systems essentially went bankrupt and is coming to age in an era when certitudes are being challenged and undone. These young men and women often have a strikingly different outlook to their parents. For one thing, the political culture that plagues the region has less of a hold over them. Their vague, multiple, nihilistic but powerful aspirations drove the uprisings although they couldn't ultimately guide them. Just as the legacy of existing political structures and cultures won't soon be swept away, this generational shift will only slowly come to bear. For now, those who have more to lose than to gain remain an obstacle to change, but that will not last forever.

Finally, the contagious effect of outrage, as displayed in 2011, may have a hidden corollary: the contagious effect of success. Although each and every country is profoundly different, we have witnessed the region's startling ability to function as an integrated space as protests swept from one country to the next. Starved of achievements and doubting itself, it wouldn’t necessarily take much to be reenergised collectively, if one or the other paths taken individually showed signs of tangible success.

That, of course, is the optimistic view. Until then, for those living through the tumult, it is all about surviving to see another, more hopeful day.

-->

-->

Bassem Youssef on the Egyptian media's "Great Writers"

Another entry in our In Translation series, courtesy of the excellent team Industry Arabic. Comedian Bassem Youssef had his hit satirical news show pulled -- after just one episode -- last Fall. While he looks for new options, he has been one of the few voices of reason and conscience and humor in Egyptian op-ed pages. This column appeared a few weeks back, but what it has to say about local media's free use of anonymous sources, rumors and conspiracy theories is still (and unfortunately will probably remain for a long time ) relevant.

Your Dear Old Professionalism is Dead, Shorouk newspaper, 24 December

by Bassem Youssef

What I read was not the typical sort of Facebook nonsense. And it wasn't a "prank" on one of those fake forums; it was a respectable article penned by the Great Writer.

There are a few names that just need to appear on any article for it to receive the "stamp of authority." For the Great Writer and Journalist cannot just flush his history down the drain and publish "any old drivel and that's it."

But between the "stamp of authority" and what I read I'm at a loss about what to believe.

Here the Writer is narrating true and accurate details about what happened between the US Secretary of State and the Gulf State Ruler.

And oh my what details!!!

The Secretary of State conveys to the king serious information about Qatar and their relations with Israel and the article goes on to relate how the Secretary of State fidgeted and how the Ruler cleared his throat. The article narrates with great precision what the US Secretary of State told him, from the opening "Allow me, Your Highness, to tell you a critical secret," to secret phone calls between Obama, the emir of Qatar and Erdogan, to how a Syrian minister snuck into Jordan dressed as a woman, to details about the latest episode of "Sponge Bob."

The article did everything short of following the minister into the bathroom!!!

The article was not a general account of what happened between the two parties – you know, the big picture. It was a word-by-word script with choice lines from a screenplay by Osama Anwar Okasha.

I'm not casting doubts on the credibility of the Great Writer, and I'm not accusing him of lying. However, the Great Writer and his comrades from among the legends of Arab journalism are the first ones who told us that if a writer writes something for his readers, he has to have sources for it. I read the article from start to finish and didn't find a single source….at all.

All that's written is that "someone trustworthy" told him these things.

Who's the layabout source that would spin these yarns?

So why were we upset with the Islamists?

Weren’t their show nothing but a steady 24-hour stream of "I was told" and "He told me and I told him”?

So why are we upset? It's enough that thousands of people read the article and really believed this friendly dialogue between the US Secretary of State and the Gulf State Ruler, and that they exchange the Arabian Nights stories that this article is chock-full of.

The problem is that, unfortunately, this type of writing, which was invented by a Great Writer in the Sixties, has become acceptable in Arab journalism, and since then "bullshitting" has become a lifestyle for many who were at the forefront of the Egyptian newspaper scene.

There's an entire generation that grew up hearing urban legends about how Sadat put poison in Nasser's cup of coffeee. And for you to be able to know this story, either Sadat told you or Nasser came back from the dead and told you, or you yourself were hiding in the coffee pot.

This Writer who confounds us every two months with a new book about the secrets of the intelligence services, the presidency and the army and who by sheer dumb luck just happens to be present at the right time and place to hear what Mubarak, Tantawy, Anan and Morsi all said. This is in addition to his uncanny ability to get in the good graces of Mubarak, Morsi and anyone else he ends up with. And let's not forget that "the Minister of Defense will force himself to run against his will;” Congratulations!

Then you have the other Writer who every now and then will inform us about the plots that American intelligence is hatching and divulge to us what spy agencies around the world are telling us. I recall that at the time of the trial of the human rights NGOs when the Americans fled, the Great Journalist told viewers that he had verified information that the US army was going to land helicopters on the roof of the American embassy to evacuate the people working in these NGOs. As a result, those in power were forced to give in and allow them to be smuggled out so such a scandal would not take place. Of course the Great Writer thought that he was thereby serving the Military Council by relating this ridiculous scenario so that people would say: "This is God's grace and wisdom. Thank God America didn't get the better of us."

Do you get it? A helicopter penetrates Egyptian airspace like it's nothing, crosses the Delta and gets past the air defense systems -- again no big deal -- then the welcome mat is rolled out for these aircraft to reach downtown. Finally, these helicopters land – nothing to see here – on the roof of the embassy and get these people out of Egypt. All while we – pardon the expression – sit around like a sack of potatoes.

But why? The Military Council at that time – how awful! – was forced into this shameful solution so that Egypt wouldn't be put to shame by a landing operation. Although this boot-licking scenario is actually more shameful to the country and its rulers. But it seems that the Great Writer "didn't think it through." But no matter, is there anyone who's paying attention or remembering these stories?

I don't mind that there are these people who know the inside story of all these matters – I wish you nothing but the best, good fellow! But I have a question about all these nice stories that these people are circulating about America, Obama and intelligence agencies: how did these stories escape the notice of American newspapers, American media outlets and American oversight bodies to end up in our newspapers and books, out of all of God's good creation?

Do you remember the story of Khairat El-Shater, who sold Sinai for 80 million dollars? Do you remember the documented information that Obama's brother is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood? Do you remember the documented information that came from a German base where a meeting took place between the great powers, and newspapers published details of the foul conspiracy that these countries were plotting against Egypt? How is it that the "respectable" newspapers and "respectable" talk shows were able to dedicate large amounts of space to discuss this villainous conspiracy -- then days later, we forgot the villainous conspiracy and Egypt's leaders sat with representatives of these countries that had plotted against us, as if it was nothing?

Doesn't it get you riled up or make you proud if you believe that neither the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN or any American media outlets were able to obtain this information, yet the bold, heroic journalists of Egyptian newspapers were able to get a hold of it so the "super" professional broadcasters could circulate it on Egyptian TV?

Do you remember the Egyptian talk show stars who reported statements about the Brotherhood, Morsi, Morsi's wife and Ezzat al-Garf -- but they were reporting statements from fake Twitter accounts?

Have you followed the transcripts of the calls attributed to Morsi and the rest of the Brotherhood leadership?

Have any of us heard them? If these calls describe their treason in detail, why are the Egyptian people not allowed to hear them? If journalists are allowed to publish transcripts of these recordings, then what objection is there to releasing the recording themselves?

I remember now the famous program that was broadcasting the events of 30 June moment by moment; The presenters in the studio were determined to read funny tweets from an account attributed to Mohamed Morsi, while the journalist sitting in their midst was trying to explain that this Twitter account was satirical. But the veteran presenter insisted on reading this fluff as if it were real.

Now the ground is ripe for such beings known as strategic experts to emerge, and for journalists who were educated at the same "Great Writer School" of the poisoned coffee cup. And nobody gives a thought to consulting sources or asking for proof of the bullshit that they spew.

My dear reader, I'm asking you to review all the information that you've read on Facebook or on websites that you think are news websites, or from presenters that read their news from these sites. How may pieces of news turned out to be true? How many pieces of news were confirmed by global news sources?

To be frank, the answer to this question is: "It doesn't matter." This news sooths your nerves because it is against those you hate. So there is no need for us to check it or verify its sources.

This is the same sin that the Islamists were guilty of before. They did not hesitate to use rumours and fabrications no matter the source, as long as it served their aims.

Now the Islamists are gone and the rumors remain, but going in the opposite direction.

January 9, 2014

Egyptian intellectuals, revolution, and the state

One of the most surprising and troubling developments of the last six months, for those of us interested in cultural as well as political life in Egypt, has been the alignment of the overwhelming majority of prominent artists and writers here with the military-backed authorities against the Brotherhood, with the endorsement of state violence and the abandonment of pluralism and human rights that that has entailed. A few recent pieces have focused on this troubled intersection between between art and politics, nationalism and liberalism.

At Jadaliyya, Elliot Colla writes about Sonallah Ibrahim's novel al-Jalid ("The Ice") which came out January 25, 2011.

Like these other novels, al-Jalid is concerned with Left revolution—its defeats, its disappointments, its erasure—in Egypt and across the globe. And of all Ibrahim’s novels, al-Jalid is his saddest. Lacking the laughter of his other works, it offers little more than a laconic lament, a shrug, about the passing of so many revolutions. More than once, as characters walk through the Moscow winter, Shukri says, “And we walked across the ice…” The protagonist plods on silently, surrounded by “comrades” but also alone, the only sound being that of feet scuffling cautiously over cracking ice. The image is an apt one for describing the increasingly slippery and cold ground on which the Egyptian Left began to tread from 1970 onwards. With these unsure steps, al-Jalid ruminates on the failure of most every revolution the Egyptian Left ever believed in, and with that, it seems to mourn the passing of the possibility of revolution itself.

[…]

What does it mean to read Ibrahim’s latest novel as a satire in this sense? For one thing, it allows us to begin to recognize the author's deep skepticism toward the revolutionaries' proposition that another world is possible. Al-Jalid elaborates a form of Left pessimism, a Marxist, anti-imperialist critique of injustice and oppression, but without the utopian promise of justice or emancipation.

This is how Ibrahim, presumably, viewed things in the late Mubarak years. Recently, it is the great writer's lack of skepticism -- his belief that the Egyptian army is "standing up to the West" and to a US-Brotherhood conspiracy -- and his willingness to overlook, even condone, police brutality, that has shocked some of us.

Meanwhile, on the New Yorker's site, Negar Azimi writes of Alaa Al Aswany's embrace of June 30 and describes a recent literary salon in Cairo:

When it finally came time for questions, a young man in a hoodie got up and, with prepared notes in hand, made a series of statements about the crimes of the Army, ending with the massacre that took place in Rabaa al-Adawiyah. At one point, he said to Aswany, “Ask yourself, do they have the right to kill innocent protestors?”

Aswany—probably thinking, “This again?”—seemed taken aback. “I didn’t kill anyone,” he said, defensively, “but anyone who kills a member of the Army is a traitor … The Muslim Brotherhood has blood on its hands.” He reiterated a point he had made earlier in the evening: even though many of Egypt’s Communists had spent years in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s prisons in the nineteen-fifties and sixties, their party never turned to violence. “They didn’t touch a mosquito,” Aswany concluded. The Brotherhood, he seemed to suggest, had violence in its DNA.

At that point, a well-dressed woman, with elaborately pomaded hair and a tight-fitting top, turned to her friend and said, loudly, of the boy in the hoodie and his female friends, who were veiled: “They are with the Brotherhood!”

One of the veiled women took issue, and soon, everyone seemed to be standing, pointing, and shouting. I saw a few elderly people in the room slip out, probably anticipating a fistfight.

Both Al Aswany -- a star public intellectual and writer of blockbusters -- and Ibrahim -- a revered experimental writer with great political and moral cachet -- exemplify the position of most of Egypt's muthaqafeen, who have gone from cheering the Janurary 25 revolution to cheering General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. Their positions shows not only the deep animosity that (for some justifiable reasons) exists between the cultural class and Islamists; it also shows how most intellectuals here continue to see themselves as guardians and spokesmen for an idealized strong state which they may criticize and oppose but which they cannot imagine life without and which they will rally to if persuaded that it is under threat. A point that is well-made in a recent article in Le Monde Diplomatique, entitled "Fractures among Egyptian Writers," which begins:

As repression grows in Egypt in the name of the "war on terrorism," eminent intellectual figures, nostalgic for Nasserism and often of the Left, have proclaimed their support for the army. This generation of elders is opposed by writers and artists who reject the return of the "deep state" and the betrayal of revolutionary ideals.

Issandr El Amrani's Blog

- Issandr El Amrani's profile

- 2 followers