Marc Herman's Blog

May 15, 2012

Apparently a consensus exists that publishing many short ...

Apparently a consensus exists that publishing many short and frequent items is a better way to run a blog than is publishing fewer and longer items. I’m certain that’s so. I’m not very good at it. Nevertheless, this space’s previous conversations about journalism and digital survival, leavened with the occasional bit of good news, shall resume shortly. Thank you to the surprising number of people who have written recently to encourage this.

March 1, 2012

Truthfully, the Rain in Spain is Mainly on the Coasts

Links for early Spring:

Apple flips out over Amazon…

While Amazon flips out over ebook prices….

Leading Mathew Ingram to muse intelligently about both.

A team of three reporters, of which I'm lucky to be one, has launched a new documentary project about Spain's unemployment crisis.

An exciting, new magazine led by an editor so clever, she really ought to have been obligated to go to medical school instead of into publishing, will be both a bi-monthly and a daily, via a re-launched website.

Pablo Barrio of the digital design house Ganso y Pulpo ("Goose and Octopus") will be co-running a workshop on non-fiction ebooks with me next week, part of the XIII Digital Journalism Congress.

The US men's national soccer team beats powerhouse Italy 1-0 when a child of Haitian immigrants passes a ball to a guy from a trailer park on the Mexican border, who scores. The Italians later rue an injury to their own star, who is from Teaneck, New Jersey.

February 27, 2012

Today’s Telling Search String

Today's Telling Search String

Blech of a Salesman

In the three months since self-publishing a piece of long form reporting, I have become more aware of the niche businesses evolving around ebooks. Graphic designers appear to be finding sustaining work. Freelance editors have less traction, but some are doing well providing notes to authors. What I have yet to understand, and would like to explore, is why the marketing business hasn't gotten very involved in the ebook business. We do not yet see many boutique marketing shops cropping up for hire by authors to sell books. Or, not nearly to the degree graphic designers, ebook packagers, and distributors have.

I find that surprising. It seems like the demand is there. With so many books available, both self published and traditionally published, solving a signal-to-noise problem in the market should have value. Personally, after three months of education in book selling, I am disposed to pay someone a percentage of every copy to market The Shores of Tripoli.

I have two theories why no one is willing to take the job, yet. This will take a minute to explain:

The first theory has to do with attitudes toward technology. For the past decade or so, the trend in digital technology has been to make multitasking easier. In journalism, the increasing quality and ease of modern cameras, communications technologies, and video editing software has led to the reduction of many reporting teams from three or four to one. This is good and bad. In Libya, I had lower costs and more freedom working alone. I conducted research, wrote articles, took photographs, recorded HD video and broadcast-quality audio alone, and edited all of that on a $400 laptop. I had a lot of control and this was very helpful to define the story quickly, get the information I needed to tell it, and remain focused. The Shores of Tripoli was in part a result of that freedom.

However multitasking also meant I did every task slightly worse than I could were I concentrating on one discipline. It is particularly difficult to take good photographs when also trying to observe a scene from the more passive, removed point of view helpful to writers. For that reason, in part, The Shores of Tripoli does not include photos.

(The other reason is that pictures increase file size, which I have to pay Amazon for with each download. Right now I pay a penny or two per sale, but with high quality photos that would become a real cost).

When I returned from Libya, I faced another round of multitasking. The culture of ebooks seems based on the idea that if I am enough of a salesman to convince publishers to take my work, than I am enough of a salesman to convince the public to buy it too.

That's a fallacy in my case. Selling ideas to editors is a very different kind of business than is selling books to readers. Nor do I have as much experience selling to the public as I do reporting, writing and talking to editors. When I used to sell stories mostly to print magazines, I did not have to go down to the news stand and sell the magazine too. The new model is for me to sell The Shores of Tripoli to Kindle Singles or some other large-scale outlet that can offer marketing help, and yet, still do most of the work myself to sell it to customers who visit Amazon.

Like juggling cameras and notebooks, I can do that. I have twitter and this blog and the various mechanisms that have become central to this kind of project. I'm not sure I can do it as well part time as I could full time. I am certain I can't do it as well as someone who has ten or twenty years experience in sales and marketing. I'm suspicious that division of labor was a good idea in the past, and perhaps still is, even if it is no longer strictly necessary.

#

Let's look at the distinction between selling to editors and selling to readers, and why it makes the lack of marketers in the ebook field surprising.

In traditional publishing, creating publicity and marketing a story was one of the key roles legacy publishers filled. It's one of the things self-publishers abandon when they turn to a place like Amazon. Here's how it usually works for non-fiction:

An editor buys an idea for a book, often via a literary agent, who acts as middleman. The text used to do this is a proposal, which includes a writing sample. Unlike with fiction, in journalism a manuscript of the book itself does not yet exist. The publishing house is betting on the idea's potential.

The publisher pays an advance to the author to produce the work. The size of the advance represents the publisher's expectation for the book's sales. That expectation is the result of a good sales job in-house by the editor who acquired and believes in the book. Selling the book inside the publisher is important to the editor's career. The editor's reputation comes from the success of his or her acquisition choices. With a professional stake in the book, the editor will argue for more funds and more marketing efforts on its behalf. Acquisition supposes advocacy.

An unintended consequence is that authors published within the same publishing house actually compete with each other more than they compete with authors from other publishing houses. They are competing for the same pot of marketing resources in-house more than they are for readers in the bookstore.

(When I published a traditional book, the situation reminded me of my first job after college, as a bicycle messenger in Washington, DC. Our messenger service encouraged us to hurry, to make our deliveries faster than those of the competing messenger services. In reality, the riders ignored the other services, and rode hard to beat the people within their own company. Completing a run before a colleague got the rider back into the que for the next package — we were paid by the delivery, and the number of packages was finite. The service usually hired one more messenger than we had the business to support, to keep us all hopping….

I lasted a year. The most successful messengers rode curiously slowly. The successful messengers used the deliveries as a cover for selling pot. That is another story. While I am certain it contains a useful lesson for the publishing business, I have yet to figure out what that lesson may be).

Anyway:

The publisher decides the book's potential, pays a commensurate advance and sets a likely date to publish the book. This is usually a year or two away. The author goes off and writes the book.

When the manuscript is finished, the book's editor, its advocate, brings it to a marketing meeting inside the publishing house. All the editors with books scheduled for publication that season argue on behalf of the books they acquired. The books that received the largest advances two years previously have a decided advantage, because the house has made a larger investment, and has incentives to dedicate more of the marketing staff's time and budget to recouping that investment.

The book receives the share of marketing effort decided in the meeting. The publisher takes it to market. The house does what it can to persuade media outlets to cover it and booksellers to feature it prominently. It arranges appearances and events for the author in some cases. The author's job is mostly to show up when and where the publisher says to do so.

None of that works very well for most authors, because their editors did not win lots of resources for them in the marketing meeting. But for those for whom it does work well, it works spectacularly well. These are the people you see on The Daily Show.

Now look at life without that structure:

Amazon sends out an email blast noting the publication of The Shores of Tripoli and a few other singles that week. It invites me to write a blog on Amazon's Kindle page. They put up a bio and offer some basic sales tracking information.

I'm trying really hard.

That's about it. Amazon has an enormous presence, so even those few actions provide great visibility for the story. In a few weeks, that effort moves on to the next group of singles.

From there I and my agent do all the work. Three months on, that's the part of the cycle I'm in now.

I and my agent are fairly well-suited to the job. Because writers and literary agents are media employees, our professional networks coincide with the mechanisms everyone uses to publicize things. In my case, publicity about The Shores of Tripoli emerged organically, from people noticing the story at Amazon.com or conducting web searches for conversations about Libya's conflict.

In other cases, however, publicity was the result of me contacting a journalist I knew. Often it was a friend of a friend. I asked that he or she write about the single.

Some did and some didn't. Still the initial hurdle a person outside journalism would face was not so high for me. I had the names and addresses of people who write these kinds of stories, and I knew how to talk to them. This is the sales I know how to do: selling ideas to editors.

My agent knew people too and has an economic stake in the story succeeding. The most consistent publicity for the story has come from a connection my agent had in the technology press.

Another advantage was the lack of internal competition. The marketing meeting I faced at the legacy publisher years ago never happened with Amazon. Because they had not paid any of the Single authors an advance, they had no budgetary reason to favor marketing one story over another. The defining factor in deciding marketing priorities, so far as I can tell, was a story's publication date. They pushed the most recent work for a few weeks, replacing aging work with newer work.

#

It's a cliche, but part of the argument for ebooks is the graying notion of the "long tail." The idea is that the internet provides products a much longer shelf life. However, an infinite shelf requires infinite marketing effort. When The Shores of Tripoli was hanging around the top ten in the Kindle Singles store, I did not have to tell people it existed. Three months later, with dozens more Singles published, I'm five pages deep on Amazon's list. I have fallen off both the metaphorical and actual screen. Also, I am moving on to new stories already. So is my agent.

So I wonder what's preventing a marketing professional interested in books or technologies from getting into this business. It could simply be that I don't represent enough upside. That's the second possibility I can imagine. But the successes we've seen suggest that marketing an ebook badly still generates a fair amount of money. So marketing it well should, in theory, produce quite a bit. Is 50,000 copies of a two Dollar work of journalism an unrealistic target? And if so, at 70% split with Amazon — $70,000 — would fifteen percent of that be worth the work? Because that's what a traditional agent gets on a $70,000 book deal. And that's a viable business. Or once was.

The Shores of Tripoli is available for $1.99 at Kindle Singles.

February 21, 2012

Regarding the Pause

Updates will resume in this space shortly. I have been waiting until I have something useful to say.

December 29, 2011

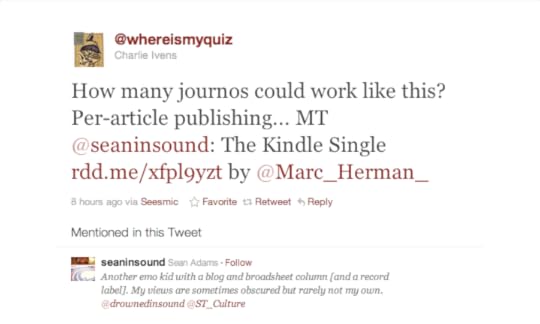

Scaling the Single

The above was among several responses over the holidays to a spate of articles on journalists and self-publishing. The stories I saw were by Ewan Spence at Forbes, Jenn Webb at O'Reilly Radar, and Matthew Ingram at GigaOm. Each talked about my own Kindle Single, which is why I saw them. From the many, many tweets and such that resulted, I suspect there are more stories out there, and a larger discussion.

I'll try to answer the question. My guess is the self-publishing model could support a lot of the reporters who were previously working as freelancers, stringers and — most notably — fixers. But it would have to be done internationally, and probably in groups.

Fixers are the people journalists hire to work as interpreters, translators and assistants. Often they are local journalists getting some side work. They usually work for $100 a day.

Rather than hire a fixer for $100 a day, it could make sense for a foreign reporter to team up with a local reporter and produce a story to market directly to readers. The team would produce a dual-bylined story, and sell it directly in a Single-like format, in both the foreign reporter's country, and the local reporter's.

Economically, the team would work pretty well. The foreign reporter offers the local one access to a new readership abroad. The local reporter offers the foreign reporter access to a story, and a savings on expenses. Translation, interpretation and local research assistance (read: help with legwork) are usually a large part of a reporting budget.

In the past, these foreign-local relationships between reporters were common, but tended to be sponsored by large news organizations. For example, when I lived in Jakarta, Indonesia a few years ago, the Washington Post's fixer was a friend of mine. He found stories for the Post's correspondents and made it possible for them to investigate. He translated, arranged transportation, and explained political and cultural facts to the reporters, who were from the US.

They in turn gave him a job, and in his case, training.

In his spare time, he and I worked on a few stories together for US magazines, and I helped him write a story in English for an American newspaper. We needed each other to do all these jobs. I needed his contacts in Jakarta and his Indonesian language skills. He needed my contacts in NY and my English language skills. We could have learned each other's skills and not needed each other after awhile. He speaks some English and I speak some Indonesian. But it would have taken a long time to make each other redundant. Even if his English grew fluent, my American professional culture would have thwarted him for awhile, and his Indonesian social culture would have thwarted me.

What does this have to do with the question posed above? I suspect were I to go back to Indonesia now, I would not only work for magazines and newspapers. Not even principally. Rather I'd propose to a local journalist that we co-author a 12,000 word story and sell it via whatever ebook distributors are largest in Indonesia, the EU and the US. We'd split the money.

This would do two things, both positive. One, we'd produce a better story, faster, working as a full-fledged team rather than a reporter and an assistant. It's a much more honest representation of what those relationships are really like — a partnership of equals. Only newspaper tradition keeps translators' and assistants' names at the bottom of the story, or invisible entirely.

Second, we'd reach a lot more readers. Indonesia, for example, is one of the most wired countries on Earth. Facebook penetration is high and mobile phone culture is overwhelming. People would likely read journalism on smartphones there. And the country has endless interesting stories. It's a fascinating, gigantic, yet ignored place.

Two bucks? But that's only 18,000 Rupiah!

If, working together, a foreign journalist like me and a local journalist produced editions of a story in Indonesian and English, the team would have access to two enormous markets. Indonesia is the world's fourth-largest country and one of its fastest-growing economies. Because ebooks have almost zero marginal cost, we could sell the story for a price that was reasonable in both Indonesia's economy and in the US or EU market. Even in Jakarta, $2-$3.00 is a good price for a small book.

We'd be more likely to produce a story that has universal appeal, too. We'd be writing for a global, rather than parochial, unilateral, monolingual audience.

If that model worked, it would be likely to repeat. Freelance journalists tend to be social types. Establishing useful partnerships would not be very hard.

#

The answer to the question "how many could do this" comes down, for me, to the changing distribution models for news. If we think of a press corps as limited to the representatives of one nation's media outlets, or to the group of correspondents present to cover a specific event (an election, a natural disaster, the Olympics) then the Single model probably supports only a narrow slice. You won't read ten Singles on the same subject.

But if a press corps is thought of as a body of multilingual, international actors working in teams, across various national, economic, linguistic and publishing communities, then I suspect quite a few people and quite a few stories could fit under a Singles or self-publishing model.

Research on this sort of thing is slim. It would be useful to have numbers on digital media use in various regions. East and South Asia seem like compelling places to experiment with selling non-fiction Singles to people who would read them on a cell phone.

It would be even more useful to have good research on translation and journalism. I worked on a small project on that theme a couple of years ago. The project was a train wreck, but we learned a few things. The most important was that virtually no one is paying attention to translation's role in journalism, and it's massively important. The Single or self-publishing model, taken internationally, might be a way into that conversation.

It is possible I am just looking for an excuse to visit Indonesia again.

December 10, 2011

The Death of the Gentleman Publisher

This week, publisher Hachette circulated a memo articulating the services it offers to authors. According to a copy reprinted on a website called Digital Book World, the memo said Hachette, and publishers in general, do four main things:

1. Curator: We find and nurture talent.

2.Venture Capitalist: We fund the author's writing process.

3. Sales and Distribution Specialist: We ensure widest possible audience.

4. Brand Builder and Copyright Watchdog: We build author brands and protect their intellectual property.

Reading the memo caused me to think back to the spring, when I had lunch with a friend who works as an senior editor with a large New York publishing house. I'd asked him to make a similar case – to convince me why authors should market their work to traditional publishers – and he had offered a similar list. In addition to finding and nurturing talent, he provides his authors money (what he called "a banking function") plus marketing, distribution, and legal muscle. It was a slightly uncomfortable conversation because I wasn't convinced. I did not know why I wasn't convinced.

After I published The Shores of Tripoli, I sent out an email to friends, family and my professional network, including the editor I had had lunch with in spring. In the email I described the Kindle Singles program this way:

Kindle Singles has been around for about a year. In the past few months it has emerged as a boutique publisher inside Amazon, publishing long-form journalism and short stories of the sort that I associate with previous eras: Life, Colliers, the classic New Yorker and those "folio" articles Harper's used to do.

The editor wrote back with a thoughtful argument taking exception to the comparison. Life and Collier's, he pointed out, were "editorially driven" – their job was journalism, not retailing. Those magazines also represented a key market for book publishers. They used to spend hundreds of thousands of Dollars to buy the right to print excerpts from the most highly-anticipated books of their era.

He has a point. At the turn of the 20th century, McClure's published Ida Tarbell's investigation of Rockefeller's Standard Oil as a nineteen-part, year-long feature. Tarbell's investigation cost the her publisher, good Mr. McClure, well into the millions in modern Dollars. It also culminated in a book, which McClure also made possible. Amazon won't do anything like that for me. Amazon just takes my work, edits it and does some marketing (or in most cases, doesn't) and makes it available for sale.

Two weeks since publishing a Single, I think I wasn't convinced back in Spring because my discomfort is less about business, than about professional culture. I've met several would-be Ida Tarbells over the past few years. I'm not sure there are too many McClures. Not in the sense of a shortage of rich guys who want to be publishers – there's still plenty of money. But in the sense of wanting to support journalism. I don't feel the values of golden age journalism are common in modern publishing; I'm suspicious that the services Hachette outlined in its memo are increasingly beside the point, because to get those services, I need to work through a culture that is at best indifferent, and often actively opposed, to the professional culture they inherited. I am suspicious Ida Tarbell would have been appalled by modern publishing, and struck out on her own.

I feel that way because of my own experiences. When I wrote a traditional book a few years back, I worked under an editor who had become famous in publishing circles for his ability to spot talent and promote it. He made best sellers. You want that, obviously. My book was a non-fiction account of a gold rush in 1990s South America. I travelled to the region several times over several years and spent months with teams of gold miners. When we were editing the book, which my famous editor did carefully, he felt that I had failed to really capture what the gold miners themselves were like.

He was right. Each one of the men I described had interesting qualities, but none of them had everything. None of them rose to the level of protagonist, and it left the story lacking.

My editor, in an email, floated the idea that I create a "composite miner." In that case, I would invent a fictional character who embodied parts of all the real miners, to exemplify the story's themes. I was surprised by the suggestion and said I thought it was a prodigiously bad one.

This happened at a low moment for American journalism. Judith Miller had yet to be fired; editors of the country's leading publications were advocating the invasion of Iraq, despite millions of people around the world understanding well enough that the White House hadn't made its case, and what case it had made smelled of something. Closest to home, we were amid a mini-wave of scandals in which journalists, most of them young men my age, had gotten caught representing fiction as fact. Stephen Glass of The New Republic and Jason Blair of the NYTimes were the most famous. Another reporter, Mike Finkel, was a closer parallel to my situation. He had done precisely what my editor was proposing. In a story about cocoa farming in western Africa, for the NYTimes Sunday Magazine, he had depicted the use of child labor in the cocoa fields. To do so, he aggregated the tales and qualities of several real children he had met in the region, invented a fictional child from that material, and told that fictional character's story as the chronicle of a real boy's life. He got caught and the Times fired him.

That's an extreme case. But it hews to a general atmosphere I've experienced firsthand. In traditional publishing, particularly books, the impulse to enforce professional standards comes more and more from the journalist and less and less from the editor. This suits me, but it's the reverse of how things usually go. Traditionally, the journalist pushes to include material. The editor evaluates the material's appropriateness. The final balance of source and information happens in the editor's office, not the journalist's notepad.

A dramatization of the system a lot of people know comes from the old movie version of the reporter's classic All the President's Men. Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, as the reporters, want to run a damning story about the President. Jason Robards, as the editor, keeps telling them they haven't got the story yet.

Great in a 30 year-old movie. In my 20 years, I've never had an editor say that. I've said it to editors lot — that I don't have it yet.

Everyone has a theory on why that's so: on what's gone wrong in US media. Mine is by far the most boring. I think it's a human resources issue. It's very hard to find numbers on any of this. My suspicion is what happened is the Cold War ended. Foreign bureaus began to close. It paralleled cutbacks in the government's defense budget. At the same time, media organizations went public in large numbers, and had to hit quarterly earnings numbers. Layoffs began. Within a year or two, the first tech boom caused many reporters to leave the industry for what seemed like promising opportunities. In total, the forces of the 1990s cost the industry a generation of institutional memory.

For international news, that was particularly damaging. Like any beat, you need some firsthand experience with international events, and ideally chaotic events, to edit stories about them. General editing skill is important, but a memory of 1980s east Africa or 1990s Bosnia helps more. And it's often a young person's game, because of the travel and instability involved, and by 40 or 45 you're ready to head to a nice, stable desk.

So a system had evolved. The reporters who had covered the Civil Rights era, the Vietnam War, and Nixon, acted later in their careers as editors for the reporters who covered the war in El Salvador, the end of Apartheid, the AIDS crisis, and the fall of communism.

But then things fell apart. By the time of 9-11, the editors answering the phone in New York, when I and my generation called from abroad (I'm 42; we're talking a decade or so ago) had come up covering the tech boom and Monica Lewinksy, not Somalia and Bosnia. They had no idea where, in my case, Jakarta, Indonesia was, or what it was like. Two months before the Bali disco bombing, the then-foreign editor of a big West Coast paper told me the only thing likely to be interesting in Indonesia would be if Osama bin Ladin was there.

Maybe Max Perkins played dirty too, though.

It's not clear to me the wave of fabulists that happened around that time is entirely the result of an attenuated professional culture. But I can't imagine that helped. It's hard to overlook that in 20 years or so, I have only in the rarest of cases worked with an editor of a previous generation. Most of my editors are peers. And very, very few of them have ever done my job themselves. So the editorial rigor in Libya or Indonesia or even at home in Barcelona came from my colleagues. The other writers created the community that mutually enforced standards. Because our bosses weren't doing it. They were thinking about staffing problems and the advertising crash and all the other things that prompted Hachette's memo.

That, finally, is why I'm skeptical of claims that working with Amazon robs me of an editorially-driven experience. In legacy publishing, I already had to create that experience myself. That's not to say I haven't worked with fantastic editors. I have, and still do. But when I add in the new business crisis, the funding questions, and look at the list above from the Hachette memo, it's hard to see the upside.

#

I was thinking about all this during the week, because I had received a few emails from other journalists asking me to comment on these kinds of issues, and to talk about my choice to self-publish a piece of long-form reporting. So I tried to look for some additional information, and mid-week, was surprised to see this:

The Wall Street Journal among others reported this week that the Justice Department is looking into whether several large publishing houses and Apple broke anti-trust laws in an effort to compete with Amazon. The case centers on an alleged effort a few years ago to counter Amazon, which had discounted electronic books to the point where publishers were losing money. If true, five publishers made a deal under which Apple, which was retailing ebooks through its Apple Store, would take a 30% cut of each book sale, but allow the publishers to set cover prices. Normally booksellers buy books wholesale from publishers, and set the retail prices themselves. The result was a floor in book prices, and higher book prices for the consumer. Next they told Amazon, allegedly, that if it didn't sign a similar agreement, called an Agency Contract, locating pricing power with the publishers, they would cut off Amazon's supply of books. From reporter Thomas Catan's story:

Before he died this year, Apple's former chief executive, Steve Jobs, told his biographer that the arrangement gave the publishers leverage to stop Amazon's heavy discounts.

"We told the publishers 'We'll go to the agency model, where you set the price, and we get our 30%, and yes, the customer pays a little more, but that's what you want anyway,'" Mr. Jobs was quoted as saying by Walter Isaacson.

"But we also asked for a guarantee that if anybody else is selling the books cheaper than we are, then we can sell them at the lower price too. So they went to Amazon and said, 'You're going to sign an agency contract or we're not going to give you the books.'"

Since last year, the Justice Department has been scrutinizing the role of Apple in negotiating what was effectively an industry-wide price increase, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The publishers named in the story are all very large players, include divisions of Hachette, Simon and Schuster, Penguin and HarperCollins. The European Union started the investigation (several of the publishers are owned by European parents). Now the US is carrying out a parallel investigation.

At at the end of the week, I'd ended up with a coda to my conversation with the editor. I don't imagine Amazon's inside stories are any more savory that its competition's are. In fact, looking through the list of Kindle Singles, I see one by a guy named Mike Finkel.

But I don't have the feeling the traditional publishing industry is on the whole more likely to produce an Ida Turnbell, or less likely to act like Standard Oil, than is Amazon. My former editor, who wanted me to create a composite, later published a best-seller revealed to be a fraud. He has nevertheless climbed steadily through the industry and continues to be a respected traditional publisher.

December 1, 2011

Meanwhile, in Egypt

I came back from Libya with some video footage. I was curious to see what I could do with it. In the end I didn't use it. Most eReaders can't handle video yet. That will change, and some reasonably well-known experiments with direct-publishing multimedia journalism already exist.

It was with this in mind that earlier this year, I made the short movie below with reporter Jenn Baljko. Jenn and I happened to run into a man named Wael Metwally, a telecom executive from a Cairo suburb, who the week before had been throwing rocks in Tahrir Square. He was a really personable guy. He also turned out to have recorded hours and hours of the Egyptian revolution on his iphone. He shared those videos with us.

We aren't film makers (we've since met someone who is, and jumped her into our gang). Months later, it's interesting to me to look at this little movie, because already it's clear the role of tablets, of selling this directly, was not yet in mind. We figured we would sell it to a traditional magazine's website. That was less than a year ago; the idea of selling a stand-alone video as journalism, for the web, as a business, now seems like a non-starter.

If I wanted to dive back into the FinalCutPro file, I think I'd change the name of this 7-minute video from "Wael's Phone" to "Wael's Head Wound." We used "Wael's Phone" because much of the imagery in the mini-doc is from Wael's phone. Thinking more about it, the story the video tells is of how an upper-class telecom executive came to get hit on the head with a brick while participating in a revolution.

My suspicion is that the one-man-band approach I've taken in writing a Kindle Single — one reporter, doing everything — will evolve into small teams of independent journalists working collaboratively, and sharing income. I very quickly started working with Jenn, and Jenn and I are now starting to work with a videographer. Our bet is that the direct publishing model for journalism will allow, and perhaps demand the inclusion of short video documentaries soon. That is too much work and too many specialties and skills for one person. Or two.

Three could work. A team can produce stories that don't just exist, but are very, very good. I was able to write a Kindle Single, but I could not have produced a Kindle Video Single, which we have to imagine will someday soon exist.

The encouraging part of the video experience so far is that we are moving strongly back toward a model for producing journalism, rather than just content. Good video with good reporting and long-form text takes us in the direction of the old Life Magazine or more recent National Geographic-type journalism. We are not there yet but it is interesting that we could get even this far with very little practice, only as long ago as spring, which now seems like another century:

Wael's Phone from ObjectivaMedia on Vimeo.

Why and How A Novelist Didn’t Write a Kindle Single

L.A. – based novelist Edan Lepucki just published a thoughtful takedown of electronic self-publishing, at The Millions. An excerpt:

The thought of Amazon being the only place to purchase my novel shivers my timbers. I don’t mind if someone else chooses to read my work electronically, just as I don’t mind if Amazon is one of the places to purchase my work; I’m simply wary of Amazon monopolizing the reading landscape. Self-publishing has certainly offered an alternative path for writers, but it’s naive to believe that a self-published author is “fighting the system” if that self-published book is produced and made available by a single monolithic corporation. In effect, they’ve rejected “The Big 6″ for “The Big 1.”

She’s also concerned that she may not be able to buy her own book (which her publisher sells both as a print edition and as a $5.00 ebook).

She’s right to worry. I can’t buy my latest story. I don’t have an eReader, and my 2007 Macbook tells me it needs its OS updated to support the Kindle Reader App.

The people I wrote about don’t have any idea what I said about them, either. This is a first in my career. I’ve always sent copies of books or articles to the people who share their stories with me. To do that will require more creativity now. My latest story is a dispatch from Libya. The characters, who are real people, read in Arabic.

So it was dismaying when my friend Mohamed ElGohary, an Egyptian journalist, informed me a few days ago that the Kindle screen does not yet support Arabic. (Some models can display PDFs in Arabic. They process the words as images, not as text, constraining usability.)

That’s not just a problem of courtesy for me. It’s also a business handicap. A key question implied by direct digital publishing is the fate of international copyright. Copyright used to end at the water’s edge. Selling publishing rights in other languages was a key business for legacy publishers and a source of income — often considerable — for authors.

That’s not the case for my Kindle Single. I can sell it to whomever can connect to Amazon.com’s Single’s page, and Amazon is expanding throughout the world.

It’s a technical issue, but how fast Kindle supports different alphabets could influence how I distribute long-form dispatches in the future. If hardware support defines this kind of journalism’s expansion more than market support does, an international reporter will be in a bind.

That bind is different for a novelist like Edan Lepucky than it is for a reporter like me. I know that the Arab Spring is an important story. I know too that Arabic speakers are one of the fastest-growing user communities on the internet, and that Arabic readers are enthusiastic customers for electronic devices. And I know, most importantly, that my story takes place in Libya. Social networking is wildly popular in the MENA (“Middle East-North Africa”) region. And Arabic has one of the world’s richest literary traditions. People in the Middle East will absolutely be online buying, talking about, and debating literature, and the biggest story of the year happened in their backyard (and in Libya, the front yard). I suspect I could find readers in the MENA region to justify the $1000 or so it would cost me to translate my story into Arabic, that part of the world’s lingua franca.

The non-business issue is tied to the business issue. I can’t sell to the people whose lives I’m writing about; for a journalist, this brings up questions of what kind of conversation I’m hoping to provoke. I’m not, in theory, an anthropologist, doing my fieldwork and then carrying that back to another land to discuss with my own people. I’m seeking to occupy a lacuna in an emerging global narrative. The Shores of Tripoli is the result of a baton pass, from the journalists who wrote other, previous stories about the Arab Spring. Then I get my turn. Then I pass to, say, Mohamed ElGohari. And then he passes to the next, who may well be Japanese or Spanish. That is how we understand current events today, I suspect. In aggregate.

But the hardware has to support that narrative chain, or it breaks, and can be pretty taxing to repair. And the Arab world is a huge link this year.

So while I’m still confident I did the right thing bringing The Shores of Tripoli to Amazon and not a traditional magazine, Lepucky’s comments were provocative. Paper reliably accepts ink in whatever shapes one prefers.