Andrew Zolli's Blog, page 3

July 21, 2013

Urgent Biophilia, Kairotic Time, and Sacred Space

One of the pleasures of my work is having regular contact with a community of thinkers whose collective interests wend (albeit in a eclectic way) through various tributaries of the contemporary arts and sciences.

When different constituents in this network start pointing to the same thing, it’s a pretty reliable proxy for its significance, or at the very least its interest. So it seemed more than kismet a few months ago when three unrelated colleagues pointed me to recent work by ecologist Keith Tidball at Cornell University, specifically his work on “urgent biophilia”.

Tidball’s contribution is a nuanced expansion of the term first introduced by E.O. Wilson in his 1984 landmark book, to express humanity’s innate preferences for living things, the “connections that human beings subconsciously seek with the rest of life”:

From infancy we concentrate happily on ourselves and other organisms. We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like moths to a porch light. Novelty and diversity are particularly esteemed; the mere mention of the word extraterrestrial evokes reveries about still unexplored life, displacing the old and once potent exotic that drew earlier generations to remote islands and jungled interiors …

To affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development. To an extent still undervalued in philosophy and religion, our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its currents.

Tidball elaborates on Wilson’s original concept of biophilia, connecting it to our response to disasters. He suggests that catastrophes may stir within us a vital instinct to reengage with nature, in ways that restore not only the environment, but also ourselves:

… when humans, faced with urgent disaster or hazard situations, when individuals and as communities and populations seek out doses of contact and engagement with nature to further their efforts to summon and demonstrate resilience in the face of a crisis, they exemplify an urgent biophilia … [T]he affinity we humans have for the rest of nature, the process of remembering that affinity and the urge to express it through creation of restorative environments, which may also restore or increase ecological function, may confer resilience across multiple scales.

Such an instinctive turn toward nature after disaster might initially strike one as counterintuitive. After all, there might not be any such thing as a ‘natural’ disaster, but many catastrophes feature significant ecological disruption. It seems just as plausible that, in the wake of such tumult, people might turn away from nature, expressing a kind of ‘urgent antibiophilia’.

Yet, in my own conversations with people in disaster-affected areas around the world, engagement with the natural world often surfaces as an important part of the post-disaster healing process. In New Orleans, after Katrina, a woman described how she and her neighbors planted trees throughout their neighborhood, both as a symbol of their own commitment to place, and (in a spirit of defiance and solidarity) to assert new ecological ‘facts on the ground’. A tornado victim from Joplin, MS told me he replanted tomatoes almost immediately after the tornadoes, “just to have living things around”.

In these, and countless other similar encounters, the conversation is almost never about dominance or reasserting control over nature, but rather about communion, consolation, recovery, and the restoration of coherence. One often hears synonyms for words like awakening, reckoning, correction, redemption, rebalancing, and even liberation through the disaster event.

For understandable reasons, the dialogue around disasters rarely exceeds a tally of what has been lost, harmed and broken. Almost never do we speak about broader cognitive and spiritual shifts that sometime attend such disruptions, out of an understandable fear of diminishing what has been often horrifically rent apart.

Yet for some (certainly not all) of those in a disaster-affected community, the period after a disruption can be one of profound, even peak significance. The loss of the usual signposts of life that attend a catastrophe can also liberate us from social norms and expectations, freeing us to think and act in new ways, surprising even ourselves. Amid the sorrow and confusion that follow any disaster, some people in affected communities experience a deepened sense of meaning and purpose, of increased agency, possibility and commonweal. Connections to place, to community, and to nature intensify, becoming more vivid and more sacred. Individuals can find themselves slipping into an entirely different kind of time, called kairotic time – not the chronological time of days, but closer to the psychological time found in novels – measured by the internal psychological progress of its protagonists, through a series of dilemmas and contradictions, toward a moment of resolution and purpose. In kairotic moments, the subjective experience of time itself is enlarged and its meaning is transformed. A Haitian colleague once told me that the earthquake “crucified her old life and set her free in her new one”. The choice of words hardly seemed accidental.

What is true for individuals seems likely true for communities as well. If the preexisting bonds of trust and solidarity are sufficiently strong, the post-crisis moment can be one of collective imagination and creative possibility, liberated from at least some prior constraints.

It seems likely that these aspects of human nature – our urgent biophilia and the possibility of post-crisis kairosis – are intertwined and mutually reinforcing. If that’s true, it suggests that ecological engagement and the design of restorative environments have critical roles to play in building community resilience in both the short and long-term.

Indeed, that’s the very premise of the Landscapes of Resilience project, led by Tidball, as well as Erika Svendsen and Lindsay Campbell, social scientists with the U.S. Forest Service, working with TILL, a landscape architecture firm in Newark, NJ, and others, supported by the TKF Foundation. The Landscapes project will collectively envision, design, build and measure two “open and sacred spaces” in Joplin, MS and New York City – places of ecological engagement, remembrance, shared stewardship, and psychosocial restoration. (In undertaking this work, the team would do well to connect with Milenko Matanovic and his colleagues at the Pomegranate Center, who have developed deep expertise in designing exactly these kinds of spaces with communities.)

Regardless of its outcomes, this project touches on important, and often under-appreciated aspects of our response to disruptions. First, the connections between our mental health and the natural environment are integral and profound, and need to be respected as a key enabler of the resilience of any community. Second, the cognitive, spiritual and social dimensions of disruptions take time to unfold, and should not be measured solely by what has been lost, but understood in much broader, longer-term and potentially transformational terms. And finally, the post-crisis moment may offer a unique window for positive intervention in a social-ecological system – one that we should be prepared for with the right tools and processes to help communities ‘bounce forward’ and not merely recover.

April 22, 2013

Ordinary Magic,No Less Magical

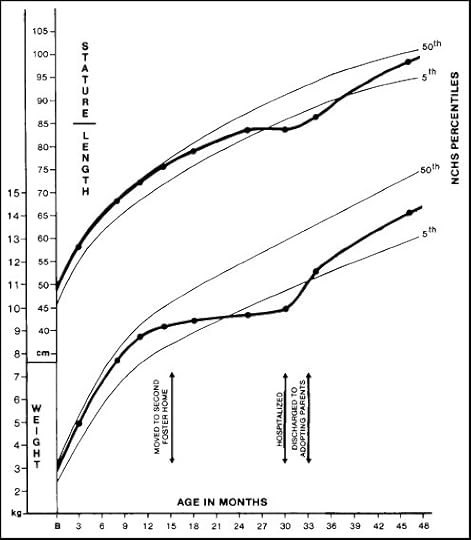

Here is one of the most powerful graphs I’ve been exposed to in some time:

It’s from a remarkable case study, first published in 1989, by the developmental child psychologist (and one of my intellectual heroes) Ann Masten and her colleague Mary J. O’Connor.

The diagram tells part of the developmental story of Sara (not her real name) a 2 ½-year-old girl in foster care who suffered significant early trauma. Her story powerfully illuminates some important aspects of trauma resilience, particularly early in life.

Little was known of Sara’s mother, except that she was an occasionally homeless sex worker who reported suffering from bouts of schizophrenia. (Nothing was known of her father.) On her first day of life, against her doctor’s advice, Sara’s mother removed her from the hospital, only to abandon her a day later. Sara was then entered into protective custody and placed with her first foster family, with whom she stayed for her first 15 months of life.

By all accounts, she was a healthy baby and toddler, developing normally. Then, sadly, the husband/father in her foster family became ill and suddenly died. Sara was removed, without any preparation, from the only family she had known, and placed with a second foster family.

Almost immediately, everything about Sara’s developmental narrative changed. Upon arrival in her new home, she cried for a month without consolation. Her language skills declined precipitously, and she rarely spoke spontaneously. Distressingly, she would assume ‘statue-like poses’ for up to 20 minutes at a time, leading her new foster mother to speculate that she might have developmental disabilities. Even her physical growth slowed, as noted in the chart above – a phenomenon called ‘psychosocial dwarfism’. A consulting psychologist initially concluded she was functionally retarded, and may have been severely deprived. After much debate, she was admitted to an inpatient child psychiatric unit for evaluation.

In the hospital, Sara continued to express this fear of strangers, ‘freezing’ or walking with difficulty and stiffness, and showing an intense attachment, first to her foster mother, and then to her primary care nurse.

But after a month at the hospital, Sara’s interdisciplinary case team concluded that she was neither developmentally disabled nor schizophrenic. Rather, Sara’s challenges had come from environmental stressors, particularly the interruption of her early attachment relationships. They recommended she be adopted right away, and literally wrote a prescription for a new family designed around her needs: one that would have older children in it, but no infants or toddlers; a mother who would be at home most of the time; and a commitment to stay in the same place for some time.

Encouragingly, just such a family was found, and after several weeks of counseling, this new adoptive family took Sara home for good. Over her three months in the hospital, Sara had gained a year, developmentally; after discharge, she continued to grow, and after a year with her new (and permanent) family, had fully caught up. An assessment conducted several years later found she was a normal and well-adjusted little girl.

Sara’s precipitous decline after the trauma of being removed from her first foster home shows how severe stressors can affect not just our brains, but also our bodies – particularly when they are still developing. Her equally dramatic reversal shows just how resilient we can be, when placed in the right psychosocial context. (And, to me, it also captures something about the essential experience of love.)

Researchers, like Masten and others who study personal resilience, find many adaptive systems at work in our ability to recover from trauma. The strength of our social networks; the quality of our attachment relationships; the health of our brain and body; the interaction of our genes and lived experiences; our level of personal mastery and self-control; our spirituality and systems of belief; our access to resources of all kinds; the quality of the community we inhabit; and (especially) our ‘habits of mind’ – all play a part.

The good news is that these processes are neither mysterious nor rare – indeed they are so common (though by no means universal) that Masten famously labeled them ‘Ordinary Magic’.

The even better news is that we are discovering new ways to help bolster that innate resilience where it might have been diminished by circumstance. Thaddeus Pace, of the Emory University Mind Body Program (and a PopTech Science Fellow) and his colleagues have long-studied the effects of contemplative, compassion-based practices on our psychological and physical health. These practices, which researchers call Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT) originated in Tibetan Buddhism, and are designed to help practitioners better manage the emotional content of lived experience, and cultivate a sense of compassion toward themselves and others.

Pace and his colleagues recently researched the effectiveness of CBCT with a group of adolescents in the foster care system in Atlanta. Almost by definition, all of these children had experienced severe stressors – ranging from neglect and abuse to drug addiction and violence. CBCT training not only decreased their anxiety and improved other measures of psychological resilience, it also diminished their physiological levels of a biomarker called the C-reactive protein, which signifies a person’s level of cellular inflammation. This inflammation, in turn, is implicated in a wide array of chronic illnesses later in life, from cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes to cancer and depression. In other words, CBCT might (and I must stress, might) not only boost the near-term psychosocial resilience of young people who experience trauma, but also long-term, adverse health effects that might not manifest for decades.

These kinds of results are moving, inexorably, from the lab to the field. The coming years will bring exciting new ways of packaging, delivering and reinforcing such training – in person, via mobile devices, and in ways as yet unimagined.

February 15, 2013

Five Climate Actions Obama Can Take Without Congress

During Wednesday’s State of the Union speech, President Obama reaffirmed climate action as one of the central planks his second term agenda, saying “I urge this Congress to pursue a bipartisan, market-based solution to climate change, like the one John McCain and Joe Lieberman worked on together a few years ago. But if Congress won’t act soon to protect future generations, I will.” (Emphasis added.)

The next day, I sat down with Jeff Nesbit, the Executive Director of Climate Nexus – a communications initiative that is working to change the national climate conversation, and tell the climate story in new and innovative ways. Jeff is a talented and seasoned communicator and wise in the ways of Washington. We discussed the speech, and what, exactly, the President could do without Congressional approval.

Quite a bit, it turns out. There are five areas in particular where the President has latitude to act unilaterally:

The first is to direct the Environmental Protection Agency to seek additional opportunities where it can regulate greenhouse gasses as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act. This authority was affirmed in 2007 in a landmark ruling by the Supreme Court, and it has since been used as the legal basis for raising the CAFE fuel efficiency targets for automobiles, as well as for setting the emissions limits for coal plants high enough to force the closure of older plants and effectively shutter plans for new ones.

However, this part of the story here is a bit more complex, as the current US boom in natural gas – much of it driven by hydraulic ‘fracking’ – had already provided energy companies with more positive economic incentives to shift away from coal plants. And, it must be pointed out, coal isn’t going away globally – its use is continuing to grow rapidly, particularly in developing economies. In fact, the International Energy Association (IEA) predicts that coal will actually rival oil, globally, as the world’s dominant energy source by as early as 2017. (China uses more coal than the rest of the world combined, and India is on track to become the world’s largest importer – neither country has a fully developed natural gas infrastructure.) Indeed, so voracious are the developing economies’ (and Europe’s) appetites that US coal exports are skyrocketing. Whether these exports will ultimately raise or lower emissions is a subject of recent debate and conjecture.

One situation the EPA will likely address this year is the regulation of coal ash, a toxic byproduct of coal burning that gained national notoriety in a horrific spill in 2008 which dumped more than 525 million gallons of wet coal ash into the Tennessee River and surrounding areas. Industry groups argue that regulating coal ash as toxic waste could cost it $20 billion annually – a burden it can ill afford, given the circumstances described above (which is, presumably, just what environmental activists hope).

Given the natural gas boom mentioned above, the second thing that Obama can do is ensure that natural gas pipelines are secure and have minimal leakage. Methane, the key ingredient in natural gas, is a much worse greenhouse gas than carbon – and according to a 2011 study by the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, if too much gas leaks into the atmosphere, and not into a pipeline, it could actually make gas much worse than coal in terms of climate effects. As long as such leaked gas remains under 3.2% of the total, gas-powered plants ecologically outperform coal-powered plants. Worryingly, however, field research, just-published in Nature, undertaken in the Uinta Basin of Utah where a big natural gas project is underway, found a whopping 9% of the methane pulled out of the ground was going straight into the air. The Administration must insist on tough rules for monitoring and tougher maximum leakage limits.

The third thing that Obama can do unilaterally is to more wholeheartedly embrace efficiency. In his speech, he actually proposed doubling US energy efficiency by 2030, which is a huge task, but there are some things he can do on his own to get started. These include improving the energy efficiency of household appliances (which are regulated by the Department of Energy) and retrofitting federal buildings (a bill for which was recently introduced by Senator Barbara Boxer) and copying the “Race to the Top” model in education reform by creating similar competition for Federal dollars among the States for improving efficiency. (This last one is actually in the President’s more detailed post-speech proposals.)

The fourth approach Obama can undertake on his own is to work to accelerate the technical substitution of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). HFCs are gasses used in refrigeration and air conditioning, and their original purpose was beneficial: they were introduced by the chemical industry as part of the Montreal Protocol to replace chlorofluorocarbons (or CFCs) that created the ‘ozone hole’ in the 1980s. Today, almost all CFCs have been phased out, and the ozone hole is shrinking dramatically. Unfortunately, the HFCs which replaced them are ‘super greenhouse gasses’ – molecule-for-molecule, almost 4000 times more atmospherically potent than carbon dioxide.

The good news is that replacements for HFCs are on the horizon. For example, two American companies, DuPont and Honeywell, recently formed a joint venture to produce a ‘drop in’ automotive refrigerant that is 97% less impactful than the HFC it replaces. So one possible opportunity for Obama (and John Kerry) is use the existing platform of the Montreal Protocol to move the more-than-190 countries who are signatories to it away from HFCs.

Finally, there’s a fifth thing Obama can do: put real muscle into making sure we don’t go backwards. Little noticed amid the hoopla of increased automotive fuel efficiency standards was an ‘escape clause’ for carmakers: if, in 2018, they aren’t selling enough of Chevy Volts and Tesla Sedans, they can argue for a reversion of the standards. Obama can put effort into pressuring the car companies to either drop the escape clause, or make progress to the goal faster.

Taken together, argues Nesbit, these actions don’t amount to an energy policy, but they could propel two positive outcomes: first, spurring Congress to act more comprehensively, and second, returning America to a leadership position in the global climate arena, putting the President in a position, by 2015, to negotiate bilateral climate deals with India and China, which is the real prize.

I said to Jeff, “This list has many features of an energy policy, though it clearly isn’t one. What’s missing that would round it out?”

Without hesitation, he said:

“A Manhattan Project for renewables. But you can’t do that without the Congress.”

December 11, 2012

The Emerging (Arctic)World Order

This summer, while America was suffering through a mega-drought that plunged half the country into a state of emergency, and India was experiencing the largest blackout in history, a group of Chinese scientists were undertaking a remarkable voyage. Aboard the world’s largest icebreaker, the Xue Long, (or ‘Snow Dragon’) they charted a course through what was once called the “Northeast Passage”, over Russia through the record-setting melting Arctic sea ice, finally docking in Reykjavik, Iceland.

China is obviously not an Arctic country, but that has not prevented it, like many other nations, from taking a keen interest in the region – scientifically, diplomatically, and commercially. In fact, the Chinese seem intent on playing a leadership role in this part of the world, particularly in Iceland, which has vast geothermal and hydroelectrical capacity (much of it currently used, controversially, to power aluminum smelters). In the capital of this small country of 320,000 people, the Chinese are constructing a truly massive embassy, with room for up to five hundred people. (The American embassy, presently the largest, holds about seventy.)

Why build something so big? Partly, to broadcast China’s presence, and partly to act as a basis of operations for the whole region, particularly those involving access to rich mineral and oil and gas resources of nearby Greenland. These may include up to 25% of the world’s reserves of rare earth metals, which are used to make magnets used in everything from cell phones to wind turbines to precision-guided munitions. (Much to the chagrin of folks at the Pentagon, China currently has about 95% of the world’s current supply.)

Indeed, plans are already being drawn up to open a huge iron ore mine in Greenland that could, overnight, swell the population of the country by 4% with Chinese workers – and that’s just from one project alone. This poses a challenge to the country’s 57,000 citizens – many of them indigenous Kalaallit – just as it does to their Icelandic neighbors (and Africans, and many others): how to admit the interests of the insatiable global extractive economy into their country in a controlled way, while trying to conserve one of the world’s pristine – and globally essential – ecosystems.

Amid these moves in a new ‘great game’ in Arctic energy, materials, and transport, something can easily be lost – the vastly greater global importance of the disappearing Arctic ice itself. The Chinese scientists aboard the Snow Dragon were there because, much like every nation – including the United States – China has to worry both about finding and extracting vast quantities of natural resources to power its growth, and about the consequences – in the form of melting ice, rising sea levels, and threats to its coastal cities – of those very extractive processes. (These threats don’t just include increasing risk from severe weather events, but also from things like the contamination of drinking water by rising seawater.)

The health of the planet’s ice is implicated in all of this, as Iceland’s President Olafur Grimsson shared with me a few days ago on a visit to Reykjavik. In our wide ranging conversation, he mentioned two things that deeply impressed me: first, that, in his international travels, nations as far away as Singapore and South Korea – realizing they have a stake in what he calls the ‘Global Arctic’ – continuously express interest in joining the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental body that addresses issues faced by regional Arctic governments and their indigenous people.

Second, President Grimsson also suggested a compelling agenda-item for Obama’s second term: convening an international Summit to directly address our shared, civilizational interest in the State of the Ice, and to generate what he called an “AHA” moment, which stands for the Arctic, Himalayas and the Antarctic – the three major ice centers on the planet. You can read about both of these and other compelling ideas in this transcript of a terrific speech he gave on the subject at the Arctic Imperative Summit, held earlier this year in Alaska.

It’s clear we need a moment of global focus and rule setting, or the new Wild West may be the Wild North.

November 10, 2012

To Jeddah, And the Launch Of The i2 Institute

Later this week, I’ll be traveling to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for a very special event – the official launch of the i2 Institute, a new organization dedicated to building an ecosystem of entrepreneurship and social innovation for scientists, technologists and engineers in the Middle East and beyond.

I2 is the brainchild of my friend and colleague, the biotechnologist Hayat Sindi. Hayat is one of those people whose career path is as improbable as it is extraordinary. She left her home country, went to the UK alone, got into Cambridge, then MIT and Harvard to do her post-doc work. There, in one of the preeminent chemistry labs in the US, run by George Whitesides, she helped launch a breakthrough medical diagnostics company called Diagnostics For All – which is developing ultra-low cost medical tests for critical health conditions.

Hayat’s fierce determination and abundant talent has been widely (and rightly) lauded in her home region and around the world – she was the only person to receive both a PopTech Social Innovation Fellowship and a Science Fellowship; she has since been named a National Geographic Emerging Explorer and was recently named a UNESCO World Ambassador for Science, among many other justly-deserved honorifics.

When Hayat met with Leetha Filderman and I in a Camden, Maine coffeehouse, after her first PopTech gathering in 2009, she laid out a big challenge, and an equally bold vision to address it. Her remarkable experience – not just pursuing scientific work at the highest level, but also working to see it translated from a research context into a company – is comparatively rare, at least by the standards of her home region. This isn’t for lack of talent – the Middle East is full of brilliant people. Instead, what is often lacking is an ecosystem – not just of money, but of mentors, colleagues, role models and institutions who could provide the services, encouragement, peer support, skills training and connectivity to help turn scientists’ and engineers’ research ideas into applied innovations that create wealth, employment, and prestige.

The consequences of the absence of this gap are significant. For example, according to NPR, the unemployment rate for college-educated men in Saudi Arabia is and eye-popping 44%. That number is an proxy for countless stories of people unable to realize their dreams and contribute to the richness of society and the world. And, as Hayat told us, it’s a story that is repeated, in different ways, across the region.

Hayat wanted to tackle this enormous challenge, and she had a clear vision of how to do so – to create a new kind of institution, starting in her home country, which could become the hub of a network of high-capacity innovators who could blaze a new path, and themselves become role models for the next generation.

So, over the next two years, with PopTech’s enthusiastic early support, she marshaled world-class resources (including the renowned strategic design firm Wolff Olins, and later McKinsey, as well as signing on MIT and Harvard). These would be essential to the task of scoping, communicating and delivering the elements of her vision.

After much work, next week, in Jeddah, Hayat’s vision will become reality: the Institute for Imagination and Ingenuity – i2 – will officially launch, opening the nomination process for its first round of Fellows.

I’m delighted to be speaking at the launch, joining innovation and design luminaries like Joi Ito of the MIT Media Lab, noted digital thinker and venture capitalist Esther Dyson, Robert Fabricant of Frog Design, and Greg Brandeau of Pixar and Next. We will be joined by HRH Prince Khalid Al-Faisal Al-Saud, as well as Mohamed Al-Mady, the Chief Executive Officer of SABIC, Abdul Aziz Al Khodary, deputy Governor of Mekkah, and Arif Naqvi, the founder and Chief Executive Officer of Abraaj Capital, among others. I’ve also joined i2’s Board of Directors as a charter member.

It’s been an honor to play a small part in all of this, but it’s been ten times more inspiring to have watched Hayat undertake the never-easy, always-exhausting process of putting together a new organization from scratch. She is part of a global ‘reaspora’, which is the opposite of a diaspora: global elites, educated in the world’s best institutions, who could live and work anywhere in the world, but who choose to return to their home regions to labor on issues of critical social significance. That makes Hayat not only a social innovation hero, but also an embodiment of the very principles she seeks to inspire in others.

To Jeddah, And the Launch Of The I2 Institute

Next week, I’ll be traveling to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for a very special event – the official launch of the I2 Institute, a new organization dedicated to building an ecosystem of entrepreneurship and social innovation for scientists, technologists and engineers in the Middle East and beyond.

I2 is the brainchild of my friend and colleague, the biotechnologist Hayat Sindi. Hayat is one of those people whose career path is as improbable as it is extraordinary. She left her home country, went to the UK alone, got into Cambridge, then MIT and Harvard to do her post-doc work. There, in one of the preeminent chemistry labs in the US, run by George Whitesides, she helped launch a breakthrough medical diagnostics company called Diagnostics For All – which is developing ultra-low cost medical tests for critical health conditions.

Hayat’s fierce determination and abundant talent has been widely (and rightly) lauded in her home region and around the world – she was the only person to receive both a PopTech Social Innovation Fellowship and a Science Fellowship; she has since been named a National Geographic Emerging Explorer and was recently named a UNESCO World Ambassador for Science, among many other justly-deserved honorifics.

When Hayat met with Leetha Filderman and I in a Camden, Maine coffeehouse, after her first PopTech gathering in 2009, she laid out a big challenge, and an equally bold vision to address it. Her remarkable experience – not just pursuing scientific work at the highest level, but also working to see it translated from a research context into a company – is comparatively rare, at least by the standards of her home region. This isn’t for lack of talent – the Middle East is full of brilliant people. Instead, what is often lacking is an ecosystem – not just of money, but of mentors, colleagues, role models and institutions who could provide the services, encouragement, peer support, skills training and connectivity to help turn scientists’ and engineers’ research ideas into applied innovations that create wealth, employment, and prestige.

The consequences of the absence of this gap are significant. For example, according to NPR, the unemployment rate for college-educated men in Saudi Arabia is and eye-popping 44%. That number is an proxy for countless stories of people unable to realize their dreams and contribute to the richness of society and the world. And, as Hayat told us, it’s a story that is repeated, in different ways, across the region.

Hayat wanted to tackle this enormous challenge, and she had a clear vision of how to do so – to create a new kind of institution, starting in her home country, which could become the hub of a network of high-capacity innovators who could blaze a new path, and themselves become role models for the next generation.

So, over the next two years, with PopTech’s enthusiastic early support, she marshaled world-class resources (including the renowned strategic design firm Wolff Olins, and later McKinsey, as well as signing on MIT and Harvard). These would be essential to the task of scoping, communicating and delivering the elements of her vision.

After much work, next week, in Jeddah, Hayat’s vision will become reality: the Institute for Imagination and Ingenuity – I2 – will officially launch, opening the nomination process for its first round of Fellows.

I’m delighted to be speaking at the launch, joining innovation and design luminaries like Joi Ito of the MIT Media Lab, noted digital thinker and venture capitalist Esther Dyson, Robert Fabricant of Frog Design, and Greg Brandeau of Pixar and Next. We will be joined by HRH Prince Khalid Al-Faisal Al-Saud, as well as Mohamed Al-Mady, the Chief Executive Officer of SABIC and Arif Naqvi, the founder and Chief Executive Officer, of Abraaj Capital, among others. I’ve also joined I2’s Board of Directors as a charter member.

It’s been an honor to play a small part in all of this, but it’s been ten times more inspiring to have watched Hayat undertake the never-easy, always-exhausting process of putting together a new organization from scratch. She is part of a global ‘reaspora’, which is the opposite of a diaspora: global elites, educated in the world’s best institutions, who could live and work anywhere in the world, but who choose to return to their home regions to labor on issues of critical social significance. That makes Hayat not only a social innovation hero, but also an embodiment of the very principles she seeks to inspire in others.

November 3, 2012

Goodbye Sustainability,Hello Resilience.

An edited version of this essay appears today as an Op-Ed in the New York Times:

For decades, people who concern themselves with the world’s “wicked problems” — interconnected issues like environmental degradation, poverty, food security and climate change — have marched together under the banner of “sustainability”: the idea that with the right mix of incentives, technology substitutions and social change, humanity might finally achieve a lasting equilibrium with our planet, and with each other.

It’s an alluring and moral vision, and in a year that has brought us the single hottest month in recorded American history (July), a Midwestern drought that plunged more than half the country into a state of emergency, a heatwave across the eastern part of the country powerful enough to melt the tarmac below jetliners in Washington and, most recently, the ravages of Hurricane Sandy, it would seem a pressing one, too.

Yet today, precisely because the world is so increasingly out of balance, the sustainability regime is being quietly challenged, not from without, but from within. Among a growing number of scientists, social innovators, community leaders, NGOs, philanthropies, governments and corporations, a new, complementary dialogue is emerging around a new idea, resilience: how to help vulnerable people, organizations and systems persist, perhaps even thrive, amid unforeseeable disruptions. Where sustainability aims to put the world back into balance, resilience looks for ways to manage an imbalanced world.

It’s a broad-spectrum agenda, which, at one end, seeks to imbue our communities, institutions and infrastructure with greater flexibility, intelligence and responsiveness to extreme events, and at the other centers on bolstering people’s psychological and physiological capacity to deal with high-stress circumstances.

For example, “resilience thinking” is starting to shape how urban planners in big cities think about updating antiquated infrastructure, much of which is robust in the face of normal threats like equipment failures but — as was just demonstrated in the New York region — fragile in the face of unanticipated shocks like flooding, pandemics, terrorism or energy shortages.

Combatting those kinds of disruptions isn’t just about building higher walls — it’s about accommodating the waves. For extreme weather events, that means developing the kinds of infrastructure more commonly associated with the Army: temporary bridges that can be “inflated” or repositioned across rivers when tunnels flood, for example, or wireless “mesh” networks and electrical microgrids that can compensate for exploding transformers.

We’ll also need to use nature itself as a form of “soft” infrastructure. Along the Gulf Coast, civic leaders have begun to take seriously the restoration of the wetlands that serve as a vital buffer against hurricanes. A future New York may be ringed with them too, as it was centuries ago.

Hurricane Sandy hit New York hardest right where it was most recently redeveloped: Lower Manhattan, which should have been the least vulnerable part of the island. But it was rebuilt to be “sustainable,” not resilient, noted Jonathan Rose, an urban planner and developer.

“After 9/11, Lower Manhattan contained the largest collection of LEED-certified, green buildings in the world,” he said, referring to a common standards program for eco-friendly design. “But that was answering only part of problem. The buildings were designed to generate lower environmental impacts, but not to respond to the impacts of the environment” — for example, by having redundant power systems. In an age of volatility, the extremophilic trumps the ecoperfect.

The resilience frame speaks not just how buildings weather storms, but how people weather them, too. Here, psychologists, sociologists and neuroscientists are uncovering a wide array of factors that make you more or less resilient than the person next to you: the reach of your social networks, the quality of your close relationships, your access to resources, your genes and health, your beliefs and habits of mind.

Based on these insights, these researchers have developed training regimes, rooted in contemplative practice, that are already helping first responders, emergency-room physicians and soldiers better manage periods of extreme stress and diminish the rates and severity of post-traumatic stress that can follow. Researchers at Emory University have shown that similar practices can bolster the psychological and physiological resilience of children in foster care. These tools will have to find their way into wider circulation, as we better prepare populations for the mental, and not just physical dimensions of disruption.

There’s a third domain where resilience will be found, and that’s in big data and mobile services. Already, the United States Geological Survey is testing a system that ties its seismographs to Twitter; when the system detects an earthquake, it automatically begins scanning the social media service for posts from the affected area about fires and damages.

Similar systems have been used to scan blog postings and international news reports for the first signs of pandemics like SARS. And “hacktivists” are exploring ways to extend the power of the 311 system to help people not only better connect to government services, but to better self-organize in a crisis.

In a reversal of our stereotypes about the flow of innovation, many of the most important resilience tools will come to us from developing countries, which have long had to contend with large disruptions and limited budgets.

In Kenya, Kilimo Salama, a microinsurance program for argiculture, uses wireless weather sensors to help small farmers protect themselves financially against climate volatility. In India, Husk Power Systems converts agricultural waste into locally generated electricity for off-grid villages. And around the world, a service called Ushahidi empowers communities around the world to “crowdsource” information during a crisis using their mobile phones.

None of these is a permanent solution, and none roots out the underlying problems they address. But each helps a vulnerable community contend with the shocks that, especially at the margins of a society, can be devastating. In lieu of master plans, these approaches offer a diverse array of tools and platforms that enable greater self-reliance, cooperation and creativity before, during and after a crisis.

Yet as wise as this all may sound, a shift from sustainability to resilience leaves many old-school environmentalists and social activists feeling uneasy, as it smacks of adaptation, a word that is still taboo in many quarters. If we adapt to unwanted change, the reasoning goes, we give a pass to those responsible for putting us in this mess in the first place, and we lose the moral authority to pressure them to stop. Better, they argue, to mitigate the risk at the source.

In a perfect world, that’s surely true, just as it’s also true that the cheapest response to a catastrophe is to prevent it in the first place. But in this world, vulnerable people are already being affected by disruption. They need practical, if imperfect adaptations now, if they are ever to get the just and moral future they deserve tomorrow.

Unfortunately, the sustainability movement’s politics, not to mention it’s marketing, have led to a popular misunderstanding: that a perfect, stasis-under-glass equilibrium is achievable. But the world doesn’t work that way: it exists in a constant disequilibrium — trying, failing, adapting, learning and evolving in endless cycles. Indeed, it’s the failures, when properly understood, that create the context for learning and growth. That’s why some of the most resilient places are, paradoxically, also the places that regularly experience modest disruptions – they carry the shared memory that things can go wrong.

“Resilience” takes this as a given, and is commensurately humble. It doesn’t propose a single, fixed future. It assumes we don’t know exactly how things will unfold, that we’ll be surprised, that we’ll make mistakes along the way. It’s also open to learning from the extraordinary and widespread resilience of the natural world, including its human inhabitants, something that, counterintuitively, many proponents of sustainability have ignored.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t genuine bad guys and bad ideas at work, or that there aren’t things we should do to mitigate our risks. But we also have to acknowledge that holy war against boogeymen hasn’t worked, and isn’t likely to anytime soon. In its place, we need approaches that are both more pragmatic and more politically inclusive — rolling with the waves, instead of trying to stop the ocean.

September 26, 2012

Resilience and Simplification

This essay appears today on the website of the Harvard Business Review:

This July, aviation officials released their final report on one of the most puzzling and grim episodes in French aviation history: the 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447, en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The plane had mysteriously plummeted from an altitude of thirty-five thousand feet for three and a half minutes, before colliding explosively with the vast, two-mile-deep waters of the south Atlantic. Two hundred and twenty eight people lost their lives; it took almost two years, and the help of robotic probes from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to even find the wreckage. The sea had swallowed them whole.

What — or who — was to blame? French investigators identified many factors, but singled out one all-too-common culprit: human error. Their report found that the pilots, although well-trained, had fatally misdiagnosed the reasons that the plane had gone into a stall, and that their subsequent errors, based on this initial mistake, led directly to the catastrophe.

Yet it was complexity, as much as any factor, which doomed Flight 447. Prior the crash, the plane had flown through a series of storms, causing a buildup of ice that disabled several of its airspeed sensors — a moderate, but not catastrophic failure. As a safety precaution, the autopilot automatically disengaged, returning control to the human pilots, while flashing them a cryptic “invalid data” alert that revealed little about the underlying problem. Confronting this ambiguity, the pilots appear to have reverted to rote training procedures that likely made the situation worse: they banked into a climb designed to avoid further danger, which also slowed the plane’s airspeed and sent it into a stall.

Confusingly, at the height of the danger, a blaring alarm in the cockpit indicating the stall went silent — suggesting exactly the opposite of what was actually happening. The plane’s cockpit voice recorder captured the pilots’ last, bewildered exchange:

(Pilot 1) Damn it, we’re going to crash… This can’t be happening!

(Pilot 2) But what’s happening?

Less than two seconds later, they were dead.

Researchers find echoes of this story in other contexts all the time — circumstances where adding safety-enhancements to systems actually makes crisis situations more dangerous, not less so. The reasons are rooted partly in the pernicious nature of complexity, and partly in the way that human beings psychologically respond to risk.

We rightfully add safety systems to things like planes and oil rigs, and hedge the bets of major banks, in an effort to encourage them to run safely yet ever-more efficiently. Each of these safety features, however, also increases the complexity of the whole. Add enough of them, and soon these otherwise beneficial features become potential sources of risk themselves, as the number of possible interactions — both anticipated and unanticipated — between various components becomes incomprehensibly large.

This, in turn, amplifies uncertainty when things go wrong, making crises harder to correct: Is that flashing alert signaling a genuine emergency? Is it a false alarm? Or is it the result of some complex interaction nobody has ever seen before? Imagine facing a dozen such alerts simultaneously, and having to decide what’s true and false about all of them at the same time. Imagine further that, if you choose incorrectly, you will push the system into an unrecoverable catastrophe. Now, give yourself just a few seconds to make the right choice. How much should you be blamed if you make the wrong one?

CalTech system scientist John Doyle has coined a term for such systems: he calls them Robust-Yet-Fragile — and one of their hallmark features is that they are good at dealing with anticipated threats, but terrible at dealing with unanticipated ones. As the complexity of these systems grow, both the sources and severity of possible disruptions increases, even as the size required for potential ‘triggering events’ decreases — it can take only a tiny event, at the wrong place or at the wrong time, to spark a calamity.

Variations of such “complexity risk” contributed to JP Morgan’s recent multibillion-dollar hedging fiasco, as well as to the challenge of rebooting the US economy in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. (Some of the derivatives contracts that banks had previously signed with each other were up to a billion pages long, rendering them incomprehensible. Untangling the resulting counterparty risk — determining who was on the hook to whom — was rendered all but impossible. This in turn made hoarding money, not lending it, the sanest thing for the banks to do after the crash.)

Complexity is a clear and present danger to both firms and the global financial system: it makes both much harder to manage, govern, audit, regulate and support effectively in times of crisis. Without taming complexity, greater transparency and fuller disclosures don’t necessarily help, and might actually hurt: making lots of raw data available just makes a bigger pile of hay in which to try and find the needle.

Unfortunately, human beings’ psychological responses to risk often makes the situation worse, through twin phenomena called risk compensation and risk homeostasis. Counter-intuitively, as we add safety features to a system, people will often change their behavior to act in a riskier way, betting (often subconsciously) that the system will be able to save them. People wearing seatbelts in cars with airbags and antilock brakes drive faster than those who don’t, because they feel more protected — all while eating and texting and God-knows-what-else. And we don’t just adjust perceptions of our own safety, but of others’ as well: for example, motorists have been found topass more closely to bicyclists wearing helmets than those that don’t, betting (incorrectly) that helmets make cyclists safer than they actually do.

A related concept, risk homeostasis, suggests that, much like a thermostat, we each have an internal, preferred level of risk tolerance — if one path for expressing one’s innate appetite for risk is blocked, we will find another. In skydiving, this phenomenon gave rise, famously, to Booth’s Rule #2, which states that “The safer skydiving gear becomes, the more chances skydivers will take, in order to keep the fatality rate constant.”

Organizations also have a measure of risk homeostasis, expressed through their culture.

People who are naturally more risk-averse or more risk tolerant than the culture of their organizations find themselves pressured, often covertly, to “get in line” or “get packing.”

This was well in evidence at BP, for example, long before their devastating spill in the Gulf — the company actually had a major accident somewhere in the world roughly every other year for a decade prior to the Deep Water Horizon catastrophe. During that period, fines and admonitions from governments came to be seen by BP’s executive management as the cost of growth in the high-stakes world of energy extraction — and this acceptance sent a powerful signal through the rank-and-file. According to former employees at the company, BP’s lower-level managers would instead focus excessively on things like the dangers of not having a lid on a cup of coffee, rather than the risk and expense of capping a well with inferior material.

Combine complex, Robust-Yet-Fragile systems, risk-compensating human psyches, and risk-homeostatic organizational cultures, and you inevitably get catastrophes of all kinds: meltdowns, economic crises, and the like. That observation is driving increasing interest in the new field of resilience — how to build systems that can better accommodate disruptions when they inevitably occur. And, just as vulnerabilities originate in the interplay of complexity, psychology and organizational culture, keys to greater resilience reside there as well.

Consider the problem of complexity and financial regulation. The elements of Dodd-Frank that have been written so far have drawn scorn in some quarters for doing little about the problem of too-big-to-fail banks; but they’ve done even less about the more serious problem of too-complex-to-manage institutions, not to mention the complexity of the system as a whole.

Banks’ advocates are quick to point out that many of the new regulations are contradictory, confusing and actually make things worse, and they have a point: adding too-complex regulation on top of a too-complex financial system could put us all, in the next crisis, in the cockpit of a doomed plane.

But there is an obvious, grand bargain to be explored here: to encourage the reduction in the complexity of both firms and the financial system as a whole, in exchange for reducing the number and complexity of regulations with which the banks have to comply. In other words, a more vanilla, but less over-regulated system, which would be more in line with its original purpose. Such a system would be easier to police and tougher to game.

Efforts at simplification also have to deal urgently with the problem of dense overconnection — the growing, too-tight “coupling” between firms, and between international financial hubs and centers. In 2006, the Federal Reserve invited a group of researchers to study the connections between banks by analyzing data from the Fedwire system, which the banks use to back one another up. What they discovered was shocking: Just sixty-six banks — out of thousands — accounted for 75 percent of all the transfers. And twenty five of these were completely interconnected to one another, including a firm you may have heard of called Lehman Brothers.

Little has been done about this dense structural overconnection since the crash, and what’s true within the core of the financial sector is also true internationally. Over the past two decades, the links between financial hubs like London, New York and Hong Kong have grown at least sixfold. By reintroducing simplicity and modularity back into the system, a crisis somewhere doesn’t always have to become a crisis everywhere.

Yet, no matter the context, taking steps to tame complexity of a system are meaningless without also addressing incentives and culture, since people will inevitably drive a safer car more dangerously. To tackle this, organizations must learn to improve the “cognitive diversity” of their people and teams — getting people to think more broadly and diversely about the systems they inhabit. One of the pioneers in this effort is, counterintuitively, the U.S. Army.

Today’s armed forces confront circumstances of enormous ambiguity — theatres of operation with many different kinds of actors — NGOs, civilians, partners, media organizations, civilian leaders, refugees, and insurgents alike are mixed together, without a “front line.” In such an environment, the cultural nuances of every interaction matter, and the opportunities for misunderstanding signals is extremely high. In the face of such complexity, it can be powerfully tempting for tight-knit groups of soldiers to fall back on rote training, which can mean blowing things up and killing people. Making one kind of mistake might get you killed, making another might prolong a war.

To combat this, retired army colonel Greg Fontenot and his colleagues at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, started the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, more commonly known by its nickname, Red Team University. The school is the hub of an effort to train professional military “devil’s advocates” — field operatives who bring critical thinking to the battlefield and help commanding officers avoid the perils of overconfidence, strategic brittleness, and groupthink. The goal is to respectfully help leaders in complex situations unearth untested assumptions, consider alternative interpretations and “think like the other” without sapping unit cohesion or morale, and while retaining their values.

More than 300 of these professional skeptics have since graduated from the program, and have fanned out through the Army’s ranks. Their effects have been transformational — not only shaping a broad array of decisions and tactics, but also spreading a form of cultural change appropriate for both the institution and the complex times in which it now both fights and keeps the peace.

Structural simplification and cultural change efforts like these will never eliminate every surprise, of course, but undertaken together they just might ensure greater resilience — for everyone — in their aftermath.

Otherwise, like the pilots of Flight 447, we’re just flying blind.

Want Resilience?Kill the Complexity.

This essay appears today on the website of the Harvard Business Review:

This July, aviation officials released their final report on one of the most puzzling and grim episodes in French aviation history: the 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447, en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The plane had mysteriously plummeted from an altitude of thirty-five thousand feet for three and a half minutes, before colliding explosively with the vast, two-mile-deep waters of the south Atlantic. Two hundred and twenty eight people lost their lives; it took almost two years, and the help of robotic probes from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to even find the wreckage. The sea had swallowed them whole.

What — or who — was to blame? French investigators identified many factors, but singled out one all-too-common culprit: human error. Their report found that the pilots, although well-trained, had fatally misdiagnosed the reasons that the plane had gone into a stall, and that their subsequent errors, based on this initial mistake, led directly to the catastrophe.

Yet it was complexity, as much as any factor, which doomed Flight 447. Prior the crash, the plane had flown through a series of storms, causing a buildup of ice that disabled several of its airspeed sensors — a moderate, but not catastrophic failure. As a safety precaution, the autopilot automatically disengaged, returning control to the human pilots, while flashing them a cryptic “invalid data” alert that revealed little about the underlying problem. Confronting this ambiguity, the pilots appear to have reverted to rote training procedures that likely made the situation worse: they banked into a climb designed to avoid further danger, which also slowed the plane’s airspeed and sent it into a stall.

Confusingly, at the height of the danger, a blaring alarm in the cockpit indicating the stall went silent — suggesting exactly the opposite of what was actually happening. The plane’s cockpit voice recorder captured the pilots’ last, bewildered exchange:

(Pilot 1) Damn it, we’re going to crash… This can’t be happening!

(Pilot 2) But what’s happening?

Less than two seconds later, they were dead.

Researchers find echoes of this story in other contexts all the time — circumstances where adding safety-enhancements to systems actually makes crisis situations more dangerous, not less so. The reasons are rooted partly in the pernicious nature of complexity, and partly in the way that human beings psychologically respond to risk.

We rightfully add safety systems to things like planes and oil rigs, and hedge the bets of major banks, in an effort to encourage them to run safely yet ever-more efficiently. Each of these safety features, however, also increases the complexity of the whole. Add enough of them, and soon these otherwise beneficial features become potential sources of risk themselves, as the number of possible interactions — both anticipated and unanticipated — between various components becomes incomprehensibly large.

This, in turn, amplifies uncertainty when things go wrong, making crises harder to correct: Is that flashing alert signaling a genuine emergency? Is it a false alarm? Or is it the result of some complex interaction nobody has ever seen before? Imagine facing a dozen such alerts simultaneously, and having to decide what’s true and false about all of them at the same time. Imagine further that, if you choose incorrectly, you will push the system into an unrecoverable catastrophe. Now, give yourself just a few seconds to make the right choice. How much should you be blamed if you make the wrong one?

CalTech system scientist John Doyle has coined a term for such systems: he calls them Robust-Yet-Fragile — and one of their hallmark features is that they are good at dealing with anticipated threats, but terrible at dealing with unanticipated ones. As the complexity of these systems grow, both the sources and severity of possible disruptions increases, even as the size required for potential ‘triggering events’ decreases — it can take only a tiny event, at the wrong place or at the wrong time, to spark a calamity.

Variations of such “complexity risk” contributed to JP Morgan’s recent multibillion-dollar hedging fiasco, as well as to the challenge of rebooting the US economy in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. (Some of the derivatives contracts that banks had previously signed with each other were up to a billion pages long, rendering them incomprehensible. Untangling the resulting counterparty risk — determining who was on the hook to whom — was rendered all but impossible. This in turn made hoarding money, not lending it, the sanest thing for the banks to do after the crash.)

Complexity is a clear and present danger to both firms and the global financial system: it makes both much harder to manage, govern, audit, regulate and support effectively in times of crisis. Without taming complexity, greater transparency and fuller disclosures don’t necessarily help, and might actually hurt: making lots of raw data available just makes a bigger pile of hay in which to try and find the needle.

Unfortunately, human beings’ psychological responses to risk often makes the situation worse, through twin phenomena called risk compensation and risk homeostasis. Counter-intuitively, as we add safety features to a system, people will often change their behavior to act in a riskier way, betting (often subconsciously) that the system will be able to save them. People wearing seatbelts in cars with airbags and antilock brakes drive faster than those who don’t, because they feel more protected — all while eating and texting and God-knows-what-else. And we don’t just adjust perceptions of our own safety, but of others’ as well: for example, motorists have been found topass more closely to bicyclists wearing helmets than those that don’t, betting (incorrectly) that helmets make cyclists safer than they actually do.

A related concept, risk homeostasis, suggests that, much like a thermostat, we each have an internal, preferred level of risk tolerance — if one path for expressing one’s innate appetite for risk is blocked, we will find another. In skydiving, this phenomenon gave rise, famously, to Booth’s Rule #2, which states that “The safer skydiving gear becomes, the more chances skydivers will take, in order to keep the fatality rate constant.”

Organizations also have a measure of risk homeostasis, expressed through their culture.

People who are naturally more risk-averse or more risk tolerant than the culture of their organizations find themselves pressured, often covertly, to “get in line” or “get packing.”

This was well in evidence at BP, for example, long before their devastating spill in the Gulf — the company actually had a major accident somewhere in the world roughly every other year for a decade prior to the Deep Water Horizon catastrophe. During that period, fines and admonitions from governments came to be seen by BP’s executive management as the cost of growth in the high-stakes world of energy extraction — and this acceptance sent a powerful signal through the rank-and-file. According to former employees at the company, BP’s lower-level managers would instead focus excessively on things like the dangers of not having a lid on a cup of coffee, rather than the risk and expense of capping a well with inferior material.

Combine complex, Robust-Yet-Fragile systems, risk-compensating human psyches, and risk-homeostatic organizational cultures, and you inevitably get catastrophes of all kinds: meltdowns, economic crises, and the like. That observation is driving increasing interest in the new field of resilience — how to build systems that can better accommodate disruptions when they inevitably occur. And, just as vulnerabilities originate in the interplay of complexity, psychology and organizational culture, keys to greater resilience reside there as well.

Consider the problem of complexity and financial regulation. The elements of Dodd-Frank that have been written so far have drawn scorn in some quarters for doing little about the problem of too-big-to-fail banks; but they’ve done even less about the more serious problem of too-complex-to-manage institutions, not to mention the complexity of the system as a whole.

Banks’ advocates are quick to point out that many of the new regulations are contradictory, confusing and actually make things worse, and they have a point: adding too-complex regulation on top of a too-complex financial system could put us all, in the next crisis, in the cockpit of a doomed plane.

But there is an obvious, grand bargain to be explored here: to encourage the reduction in the complexity of both firms and the financial system as a whole, in exchange for reducing the number and complexity of regulations with which the banks have to comply. In other words, a more vanilla, but less over-regulated system, which would be more in line with its original purpose. Such a system would be easier to police and tougher to game.

Efforts at simplification also have to deal urgently with the problem of dense overconnection — the growing, too-tight “coupling” between firms, and between international financial hubs and centers. In 2006, the Federal Reserve invited a group of researchers to study the connections between banks by analyzing data from the Fedwire system, which the banks use to back one another up. What they discovered was shocking: Just sixty-six banks — out of thousands — accounted for 75 percent of all the transfers. And twenty five of these were completely interconnected to one another, including a firm you may have heard of called Lehman Brothers.

Little has been done about this dense structural overconnection since the crash, and what’s true within the core of the financial sector is also true internationally. Over the past two decades, the links between financial hubs like London, New York and Hong Kong have grown at least sixfold. By reintroducing simplicity and modularity back into the system, a crisis somewhere doesn’t always have to become a crisis everywhere.

Yet, no matter the context, taking steps to tame complexity of a system are meaningless without also addressing incentives and culture, since people will inevitably drive a safer car more dangerously. To tackle this, organizations must learn to improve the “cognitive diversity” of their people and teams — getting people to think more broadly and diversely about the systems they inhabit. One of the pioneers in this effort is, counterintuitively, the U.S. Army.

Today’s armed forces confront circumstances of enormous ambiguity — theatres of operation with many different kinds of actors — NGOs, civilians, partners, media organizations, civilian leaders, refugees, and insurgents alike are mixed together, without a “front line.” In such an environment, the cultural nuances of every interaction matter, and the opportunities for misunderstanding signals is extremely high. In the face of such complexity, it can be powerfully tempting for tight-knit groups of soldiers to fall back on rote training, which can mean blowing things up and killing people. Making one kind of mistake might get you killed, making another might prolong a war.

To combat this, retired army colonel Greg Fontenot and his colleagues at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, started the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, more commonly known by its nickname, Red Team University. The school is the hub of an effort to train professional military “devil’s advocates” — field operatives who bring critical thinking to the battlefield and help commanding officers avoid the perils of overconfidence, strategic brittleness, and groupthink. The goal is to respectfully help leaders in complex situations unearth untested assumptions, consider alternative interpretations and “think like the other” without sapping unit cohesion or morale, and while retaining their values.

More than 300 of these professional skeptics have since graduated from the program, and have fanned out through the Army’s ranks. Their effects have been transformational — not only shaping a broad array of decisions and tactics, but also spreading a form of cultural change appropriate for both the institution and the complex times in which it now both fights and keeps the peace.

Structural simplification and cultural change efforts like these will never eliminate every surprise, of course, but undertaken together they just might ensure greater resilience — for everyone — in their aftermath.

Otherwise, like the pilots of Flight 447, we’re just flying blind.

July 12, 2012

Learning from SARS

On November 16, 2002, physicians at the First People’s Hospital, in the Shunde district of Foshan City, in the southern province of Guandong, China, reported an unusual case of severe pneumonia. A few days previously, a local farmer had been admitted the hospital complaining of a high fever and a dry cough, and had died soon after. Though no one knew it at the time, this was the first reported case of the first major new disease of the 21st century: SARS.

A month later, the second case was reported about 200 km away, in the city of Heyuan, also in Guandong, and in the following three months, more than 300 cases were reported across the province, many of them lethal. Amazingly, long before the outbreak had spread even this far – and months before it became an issue of worldwide public concern – an organization on the other side of the planet was already sensing the danger. Canada’s Global Public Health Intelligence Network, or GPHIN, had been set up just a few years before the outbreak as an electronic global health observatory, monitoring the Internet and other global electronic media for signs of potential disease outbreaks or other health crises around the planet. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, GPHIN’s software scans tens of thousands of digital sources in eight languages for the first hints of trouble.

On the 27th of November – just 11 days after the first reported case – GPHIN picked up reports of a “flu outbreak” in China and sent them on to an equally remarkable organization called GOARN, the Global Outbreak and Alert Response Network. GOARN is a global network of more than 120 public health surveillance and response organizations operated by the World Health Organization. Each year, it identifies and coordinates responses to more than 50 public health outbreaks around the world – but SARS was the first new outbreak GOARN had to contend with which started spreading rapidly and internationally. In many ways, SARS shared features of both the pathogen that killed Jamaica’s urchins, and the contagion of uncertainty that spread through the financial network: it was fast, lethal, easily transmissible and on the move.

During the global SARS containment effort, GOARN proved invaluable, linking together some of the world’s best virologists, epidemiologists and other public health experts in a worldwide collaborative network that shared what was being learned about what caused SARS, how it was transmitted, and where it was likely to go next, all in real-time. This in turn enabled the World Health Organization to offer specific, up-to-date, scientifically informed guidance to governments and to the public directly about how to best prevent the spread of the illness as it was unfolding.

Nowhere were these communications better implemented than in Singapore. SARS had arrived there in February 2003, carried by a 26-year-old woman returning from a vacation with several friends in Hong Kong. There, she had a chance encounter in the elevator of the Metropole Hotel with an infected physician, a respitory specialist from southern China who was there to attend a wedding. The doctor (who became too sick to attend) acted as a ‘super spreader’, passing the illness not only on to her, but also to seven other international guests who were staying on the same floor of the hotel – perhaps by something as innocuous as leaving trace amounts of the virus on an elevator button. It was a crucial, silent and disastrous moment in spread of the disease, as two of these fellow hotel guests later carried the virus back to their home countries of Vietnam and Canada, initiating its spread there, while the young woman, unwittingly, brought it back to Singapore.

Between arriving back home and being admitted to the hospital on March 1st, 2003, the young woman infected at least 20 others over a period of several days. Then, once in the hospital, she infected one of her doctors, nine nurses, and nine of the approximately 30 family members and friends who visited her – all before her SARS was diagnosed. The disease subsequently spread to four other healthcare institutions and a vegetable wholesale center. Starting with this first case, during the period between March and May 2003, 238 probable SARS cases and 33 deaths were reported across Singapore. As the virus spread, so did public panic.

Singapore’s response to the emerging threat was an all-out, national effort, intended to be as comprehensive and as swift as the disease itself. Once it was clear that the infection was capable of spreading rapidly in hospitals, a single medical facility, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, was designated as an isolation hospital for SARS patients. All departing and arriving passengers at Singapore’s airports and seaports were given temperature checks to detect possible cases. Taxi and bus drivers were similarly checked, and public transport operators displayed stickers to indicate that the drivers had been checked and were not infected. All schools in the country were closed for ten days. Home quarantine was established for more than 6000 people known to have come into close contact with a SARS infected person; quarantined citizens had webcams set up in their homes and were called randomly during the day to ensure their compliance with the measure. The employment law was amended to ensure that quarantined citizens were compensated, alleviating economic pressures on those forced to stay at home; when a new case was discovered, a team of 100 trained “tracers” tracked down every person that the infected person might have come in contact with, from family members and neighbors to business colleagues and even local vendors on their commute to work, and placed in quarantine as well.

Singapore’s all-out response to contain the disease drew widespread praise from institutions from the World Health Organization to the World Bank, but international press coverage also suggested that the country’s success was due, at least in part, to its government’s ability to clamp down repressively on its citizens. Time Magazine’s reporting was characteristic, noting that Singapore “ruthlessly nipped its SARS problem in the bud with draconian quarantine measures.”

Yet the truth, according to according to Dr. Peter Sandman and Dr. Jody Lanard, crisis communications experts who closely followed Singapore’s response, was just the opposite. Singapore’s successful response to SARS rested not on repression, but on its near pitch-perfect use of public communications throughout the unfolding emergency.

In a crisis, the first challenge is to establish trust, and that means not sugar-coating the truth. “The most important risk communication recommendation during an evolving crisis is to avoid over-reassurance – in fact, to err on the alarming side rather than risk falling into over-reassurance,” writes Lanard. “This may well raise public anxiety in the short term, but it reassures the public in the long term that leaders are going to be honest with them. Paradoxically, over-reassuring statements tend to generate distrust – especially when the statements turn out wrong.”

As SARS panic spread across the country, Singapore’s prime minister at the time, Goh Chok Tong, said publicly that SARS could possibly become the worst crisis Singapore had faced since independence. When asked by a journalist if he was being alarmist, Goh responded: “Well, I think I’m being realistic because we do not quite know how this will develop. This is a global problem and we are at the early stage of the disease. If it becomes a pandemic, then that’s going to be a big problem for us … At the moment, I’d rather be proactive and be a little overreacting so that we get people who are to quarantine themselves to stay at home. The whole idea is to prevent the spread of the infection.”

According to Lanard, “Prime Minister Goh was illustrating an important outbreak communication principle, which is well-supported by the social science literature: Don’t aim for zero fear.” In a public health crisis, some fear is appropriate. And as long as it’s appropriately controlled, it helps. After the epidemic subsided, data suggests that Singaporean citizens who were more anxious took more recommended SARS precautions than those who were less so.

The Singaporean government also told its citizens what to expect – that this was an unprecedented situation, and that things would not return to normal for quite some time. This, according to Lanard, allowed people to emotionally rehearse for a wide variety of possibilities and get used to what might happen.

Just as importantly, when difficult choices confronted the government, Goh and his cabinet held public meetings to involve the public in key decisions. Lanard points to one example involving the most difficult part of the response: the quarantine. “People got angry about quarantine violators, particularly a man who went to a local bar waving his quarantine order in the air, and bragging that he was supposed to be at home. The Prime Minister and other officials held public meetings where they posed the dilemma of posting the names of those under quarantine order, rather than keep them confidential on medical grounds. After much discussion, they would ask for a show of hands, pro and con regarding revealing the names. The newspaper ran opinion polls on the issue. The public usually stated that they wanted other people’s names published – but not their own, if they were quarantined! Ultimately, the names were not posted. And all during this period, volunteers were taking food to the quarantined families, providing them with cell phones – and making sure they were home.”

Such responses demonstrated the government’s respect for the public’s feelings, and made them stakeholders in critical choices, building deep trust between citizens and the public health authorities. Post-outbreak surveys suggested that Singaporeans’ belief that they could communicate openly with their government was one of the most important contributing factors in their compliance with SARS precautions.