Andrew Zolli's Blog, page 2

February 10, 2015

Darwin’s Stickers

For the past year, I have been working closely with Jad Abumrad and the team at RadioLab on a fascinating story about Facebook, entitled “The Trust Engineers“.

The story centers on the work of Arturo Bejar, who is one of the technical leaders at the company, and a team of engineers, product developers and external social scientists who collectively operate under the banner of the Compassion Research Group. Together, this team is studying how our ancient human capacities for conflict, compassion, respect, trust, and empathy are expressed by people on Facebook; based on these findings, they’re reworking the service’s interface to encourage more humane relationships among its 1.3 billion users.

In addition to exploring our digital relationships and emotions, the Facebook story also touches on the ways in which our online lives are continuously experimented upon; the new ways social scientists are exploring ancient questions with ‘big data’; and the ethical considerations that such inquiries inevitably raise. Social media is changing social science, and at Facebook, we caught a glimpse of its future.

For space and flow reasons, one particularly intriguing example of this work didn’t get an in-depth airing in the radio piece, and I thought I’d relate it here more fully.

The story actually begins all the way back in 1859, with the publication of Charles Darwin’s landmark treatise, On the Origin on Species. In that book, Darwin famously lays out the argument that species evolve over the course of generations, through the process of natural selection. At the time, most scientists, not to mention most people, were creationists who believed that the great diversity of Life was part of a natural and unchanging order, over which God had given us dominion. Accordingly, Darwin left the natural conclusion of his argument – that human beings evolved via the same mechanism as all other species – largely unstated. (Except, for a single, telling line at end of the book: “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”)

Darwin didn’t publish his own fuller views on human evolution until more than a decade later, with two works that came in rapid succession, The Descent of Man (in 1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (in 1872).

In first of these books, Darwin argued, to no one’s surprise, that human beings did indeed evolve from a common hominid ancestor. In the second book, however, he presented an argument not just about the origins of our species, but of our psyches.

His argument spoke to what was, both in Darwin’s time and our own, a commonly held view: that our emotional life – marked by feelings like grief, envy, tenderness, love, guilt, pride, and affirmation – is uniquely human. If our emotions are unprecedented, so the thinking went, then we must be, too.

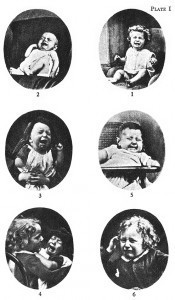

To debunk this idea, Darwin presented a detailed taxonomy of forty distinct emotions, ranging from “high spirits” such as joy, to the “low” spirits” such as despair, and concluded with the more complex emotions such as shame. Then he painstakingly documented how these emotional expressions have consistent physiological roots. Everywhere, people use the same thirty muscles in our faces to pull our lips up into a smile, knit our forehead into a frown, distort our cheeks into a grimace of psychic pain, bow our heads in supplication, and tilt our necks to signal puzzlement.

Innate experssions from Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

(CC source: Wikimedia)

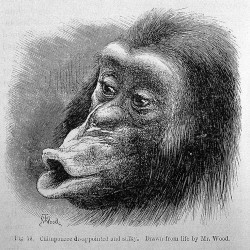

Darwin argued that these emotional expressions are not just universal across cultures, but have their roots in purposeful, and similar, animal behaviors across many mammalian species. A Chimpanzee uses similar muscle groups to purse its lips as we do, and often for the same reasons. We’re not as different – or as special – as we might suppose.

Chimpanzee pursing its lips in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

(CC source: Wikimedia)

With this argument, Darwin helped advance the field of evolutionary psychology and usher forth the robust scientific study of emotional experience. His basic thesis has been elaborated, refined, studied and debated ever since.

Researchers subsequently confirmed that human beings in both Western and non-Western societies can indeed consistently recognize a core subset of Darwin’s facial expressions. In 1967, psychologist Paul Ekman, perhaps the most well known contemporary figure in emotions research, went so far as to show these expressions to an isolated community in Papua New Guinea, who had never seen modern movies or television. They were able to identify the expressions without difficulty. Other studies have shown that our autonomic nervous system responds in consistent ways when we see Darwinian expressions of emotion – further evidence that they’re hard-wired into our biology.

Yet critics point out that both the subjective experiences and physical expressions associated with supposedly ‘basic’ emotions can vary widely even within a category. One person might stutter when enraged, while another lets loose an eloquent stream of epithets; one person might blush with quiet pride at an accomplishment, while another roars like an NFL star in the endzone.

To critics, this variability suggests that emotions are as much cultural signals as they are biological ones. To stereotype for a moment (for rhetorical purposes only – no letters, please!): is the Southern Italian, who wildly gesticulates with his hands as he talks, really using the same innate, emotional vocabulary as the famously stoic Swede? Is the facially impassive, but verbally expressive Japanese businessman really wired the same way as the ironic Brooklyn hipster? Doesn’t this variety suggest that our emotional lives are substantially, if not entirely, a matter of culture?

And, if that’s the case, why should it matter that everyone in the world can associate a smile with happiness, if people in your particular society don’t actually make a habit of smiling when they’re happy?

Here, we return to Facebook, and to the work of the Compassion Research Group. One of its leading members is the Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, who co-directs that university’s aptly-named Greater Good Science Center. A former student and colleague of Ekman, Keltner’s research explores the roots of human goodness, particularly compassion, awe, love, and beauty, and how they are communicated through means of gestures, touch and expression.

During their work together, Arturo Bejar approached Keltner with an intriguing proposition: would he be interested in using what had been gleaned in the scientific study of emotions to design a ‘sticker pack’ for Facebook?

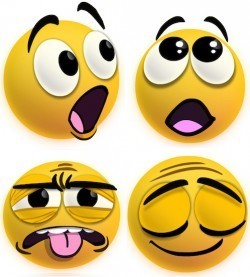

Stickers are widely-used animated icons (often of the human face or common objects) used to add expressiveness to otherwise bland text chats – think of them as more sophisticated versions of emoticons, like the “:-)”smiley face that some of us embed in our emails. Here was a chance to use Darwin’s insights to enhance the emotional content the online communications of millions of people around the world.

So Keltner turned to Matt Jones, an animator at Pixar Studios (yes, that Pixar) and gave him the job of designing 51 animated faces, mostly derived from Darwin’s original emotional taxonomy. The full list included admiration, affirmation, anger, anxiety, astonishment, awe, boredom, confusion, contemplation, contempt, contentment, coyness, curiosity, desire, determination, devotion, disagreement, disgust, embarrassment, enthusiasm, fear, gratitude, grief, guilt, happiness, high spirits, horror, ill temperment, indignant, interest, joy, laughter, love, maternal love, negation, obstinateness, pain, perplexity, pride, rage, relief, resignation, romantic love, sadness, shame, sneering, sulkiness, surprise, sympathy, terror, and weakness.

Early studies for Matt Jones’ Darwinian Facebook stickers.

(Source: Dacher Keltner)

To succeed online, Jones’ sticker designs would have to consistently communicate these emotions without benefit of a label, and in very different parts of the world. End-users would have to be able to look at the sticker for ‘happiness’ or ‘maternal love’ and identify it as such. To ensure the stickers performed as expected, Keltner and his colleagues took Jones’s prototype designs and independently tested them with research subjects in two very different societies: the United States and China.

Overall, both the Chinese and American subjects had roughly the same accuracy, correctly identifying 42 of the 51 distinct emotions presented. Cultural differences did appear: the Chinese were better able to recognize negative emotions, while the Americans were better able to identify positive ones. Yet Jones’ designs universally communicated the most extensively-researched emotions like anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise, and happiness, as well as more recently-studied ones like embarrassment, pride, desire, and love – and even a few emotions that hadn’t been studied before, like contemplation, coyness, astonishment, boredom, and perplexity.

With these results in hand, Keltner and his colleagues turned Jones’ now-tested illustrations over to Facebook’s designers, who used the best performing ones to create a new sticker pack called Finch, named after the finches Darwin had famously encountered in the Galapagos Islands. Finch contains sixteen cross-culturally tested animations of emotions based on Jones’ original designs.

Final versions of the Finch stickers

(Source: Dacher Keltner)

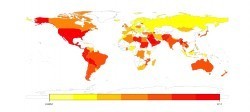

As the stickers were made available on Facebook, downloaded and then used in chats by millions of users around the world, the Compassion Research team could now look at how they were being used – not by specific users, but in the aggregate. How much ‘love’ was being expressed with the stickers in each country? Or ‘anger’? Or ‘sympathy’? Did different cultures vary in terms of the types of emotional stickers they use? Over time, the researchers realized they could use such analysis to take the emotional temperature of a sizeable portion of the planet.

Clear patterns emerged in the data. Italians, South Africans, Russians and Brazilians had ‘Cultures of Love’ – sending lots of amorous stickers. The U.S. and Canada were similar in most of their usage patterns – though the Canadians were vastly more ‘sympathetic’, while the Americans were ‘sadder’. And the use of ‘deadpan’ stickers predominated across North Africa and the Middle East.

Cultures of Sadness – geographical distribution of the use of the ‘sad’ Finch sticker on Facebook (Source: Dacher Keltner)

The picture got even more interesting when the researchers correlated the usage of the Finch stickers with other social indicators. Countries that expressed the most ‘awe’ online gave more to charity offline. And countries that expressed the most ‘happiness’ were not actually the happiest in real life. Instead, it was the countries that used the widest array of stickers that that did better on various measures of societal health, well-being – even longevity. “It’s not about being the happiest,” Keltner told me, “it’s about being the most emotionally diverse.”

These are intriguing correlations – and so far, they’re just that. We have to be careful not to over-extrapolate, or conflate the measure of the thing for the thing being measured. Clicking on a sticker to express a belly laugh is not quite the same thing as having an actual belly laugh. And while there are now more Facebook users than Catholics worldwide, there are still more people who’ve never been online than have ever been on Facebook. (One wonders how their inclusion would skew the data.)

Still, this is clearly the beginning of a unprecedented social science revolution, one that will reveal previously impossible assessments of the global psyche, and perhaps shift the dialogue about the relationship between nature and culture. And one wonders what else might consistently correlate with our global emotional weathermap. The stock market, maybe? Or social revolution? Or world peace?

How does that make you feel?

February 9, 2015

When Cleantech meets Cryptocurrency

During periods of relative calm, objective observation of the world is hard enough; foresight, even harder. During times of great change, clarity can be impossible.

Yet occasionally an encounter will reveal, sometimes just for a moment, the usually invisible systems and activities that comprise the global order – the “emergent now” that pulses just out of view. And it’s usually stranger than we would have otherwise imagined.

I had just such a moment recently in Iceland, where I had a chance to sit down with several of the country’s leading clean-tech and data center experts.

Iceland famously generates vast amounts of ultra-green electricity – about seventeen terawatts’ worth every year.* Twenty five percent of this capacity is geothermal in origin, and the rest comes from hydrothermal, making Iceland’s one of the cleanest economies in the world. This abundance has attracted energy-intensive industries (including highly controversial aluminum smelters) as well as clean-tech startups like Carbon Recycling, a company that fuses waste CO2 and hydrogen to produce “synthetic methanol”, which is exported to the Netherlands and blended with gasoline. Electricity is so cheap in Iceland (about a third of the cost in the U.S) plans are even being developed to export it to Europe via undersea cable.

Perhaps the buzziest of the industries that have been borne of Iceland’s energy independence is the green datacenter sector. The business pitch, made by local players like Verne Global, and Advania, is simple: in Iceland, data centers are cheaper to run from an electrical perspective and cheaper to cool from a geographical perspective – a double win.

Iceland’s remoteness makes it an inappropriate choice for certain datacenter applications like high-frequency Wall Street trading, where milliseconds matter and the computers have to be as close to the action as possible. But for slower applications, where cost and computing matter more than connectivity, Iceland is ideal.

One such “perfect” application is Bitcoin mining, and the country’s datacenters have attracted a lot of it. A year ago, the NYTimes’ Nathaniel Popper profiled Emmanuel Abiodun, a British entrepreneur who has established a multimillion-dollar bitcoin-mining operation called CloudHashing within a major Icelandic datacenter; Cloudhashing leases its specializing mining equipment to others.

This is presumably a tougher sell now that Bitcoins are worth closer to $200 apiece rather than the almost $1200 they commanded in late 2013. Even so, the lower cost of electricity in Iceland makes it possible to run these machines more efficiently, and presumably, make Bitcoin mining profitable at lower costs than elsewhere.

As I was preparing for my own walking tour of one of these ultra-secure facilities (the head of security pleasantly marched me through no less than nine physical security systems) one local tech-sector leader told me that most of the customers for these Bitcoin mining contracts are Chinese, and that, at its peak, demand was so high that an astounding eight percent of all Bitcoin mining worldwide was thought to be happening in Iceland.

Let’s take a moment to visualize and appreciate the resulting set of connected facts:

On an island in the North Atlantic, leagues below the surface, subterranean veins of liquid rock well upward through primordial vents, whereupon they make contact with equally ancient aquifers, producing steam that is artfully siphoned off and passed through turbines, which, when spun up, produce bountiful, carbon-free electricity.

This great stream of benign electrons – a true social good if ever there was one – is then passed onward, by means of cables, to some of the most esoteric, purpose-built computers ever assembled. These machines patiently wade through a truly psyche-shattering number of useless calculations, each one a discarded digital lottery ticket. Ever-more rarely, one of them strikes algorithmic gold. In an instant, the winning computation is transmuted into units of cryptocurrency, and on the other side of the planet, a Chinese hedge fund collects a small reward.

This is how the world works now: the geophysical system connects to the computational system, which links to the financial system, which shapes the geopolitical system, and round and round we go. Speculators from an ascendant, and nominally Communist 21st-century world power quietly leverage the entrepreneurial efforts of a citizen from a former 19th-century world power, to harness a market opportunity made possible by the unique ecological properties of an independent small state. These dependencies-at-a-distance make for strange bedfellows, for sure, but their larger consequences are not as neatly categorized: in times of relative stability, such interdependence likely improves resilience and reduces risk; in periods of complicated change, such connections likely amplify fragility and disruption.

There is also a lesson here about what happens when a resource is made cheaply and abundantly: namely, people feel comfortable “wasting” it. In the dark winters of centuries’ past, whole Icelandic families might huddle around a small fire for warmth. Now, the heat of a single rack of Bitcoin-mining computers, performing many billions of calculations a second, make it warm to the touch.

* Note: This happens to be the exact amount of energy all of humanity consumes every second.

June 12, 2014

Norwegian Slow

On a trip to Oslo this spring, I was introduced to a fascinating, genuinely countercultural phenomenon: “Slow TV“, in which mundane events, some lasting days, are broadcast in their entirety, unedited and in real-time.

Slow TV got its start in Norway in 2009, when the Norwegian state broadcaster NRK televised a six-and-a-half-hour train ride from Oslo to Bergen (available in its entirety here). To almost everyone’s surprise, more than one in five people in the country tuned in for at least some of it.

That success was followed in 2011 by a five-day long piece of footage of a ship making its way up the Norwegian coastline (available in full here). Then twelve hours of watching a log burn. Then eighteen hours of salmon swimming upstream. Recently, NRK broadcast a 9-hour “National Knitting Evening“, which featured a team trying, paradoxically, to beat a world speed record in taking wool “from sheep to sweater” – a record held by the Australians. The Norwegians failed in their attempt – but in a country of four million people, 1.3 million of them watched at least four hours of a broadcast which included four hours of discussion and eight and half hours of “long, quiet sequences of knitting and spinning”. (A two-hour excerpt is available here.) This was followed by The Piip-Show, a three-month experiment in which you could follow the lives of birds in a feeder internally decorated to look like a coffee bar. Slow TV has even inspired at least one parody – a local radio station streamed real-time footage of an abandoned porcelain toilet left by the side of the road, though in a violation of the form, it remained there for less than an hour and half before being picked up.

Why on Earth would any of this succeed? The Norwegians who told me about the Slow TV movement expressed considerable pride in its existence. One woman in her 20’s told me, “Everything moves so fast now, going slow is the new punk.” Another told me that the absence of a narrative allowed her to look – really look – at what she was seeing on the screen – and to notice details she would have otherwise missed. And middle-aged man told me he found the broadcasts comforting, and that he and his mother had watched a bit together, talking about life while the train’s gentle rumbling filled her small parlor, then fell into an easy silence for a bit, while looking out the virtual window – in other words, what people on trains actually do.

March 8, 2014

Taking the Pulse of the Planet

If you could take a picture of the whole world every day, what could you see?

It’s a simple question, with a fantastical, almost childlike premise. Now, a remarkable startup, Planet Labs, is working to answer it.

The brainchild of three visionary ex-NASA scientists and technologists (Will Marshall, Robbie Schingler, and Chris Boshuizen), PlanetLabs is launching the largest constellation of Earth-observing satellites in history. It has just deployed its first ‘flock’ of 28 such devices, each the size of a shoebox, from the International Space Station. Together, these microsatellites will deliver a composite picture of most of planet Earth, at a 3-to-5-meter/pixel resolution, every day. With the vagaries of weather, a complete picture of the planet, sans-clouds, will emerge every week or two. (The average image in Google Earth, by comparison, is 36 months old.)

The first ‘flock’ of Planet Labs satellites being released into orbit at the ISS.

Up till now, getting your hands on up-to-date, high resolution imagery of any particular location from space has been a time consuming and expensive proposition, one largely reserved for big military, governmental and commercial customers. The focus was at the very high-end of spatial resolution (sub meter per pixel). In a classic example of Schumpeterian disruptive innovation, however, Planet Labs will now provide slightly lower-resolution, but much more frequent and accessible imagery to a much larger pool of constituencies and customers.

In that wider set of hands, Planet Labs’ data will enhance consumer Internet mapping services, enrich supply-chain monitoring and improve precision agriculture. It will also transform the way we approach global challenges like climate monitoring, environmental compliance, public health, and disaster recovery, to name just a few.

This isn’t just about having another tool for addressing our grand challenges, however. It’s also about changing us. Making the whole planet accessible will help us see and understand how our planet works, how others live upon it, and how we’re all connected – which is the first step toward greater stewardship, empathy and engagement.

Some of the first “Doves” being prepped for orbit.

It’s not just Planet Lab’s imagery that’s disruptive – it’s also the way the company’s “Doves” (as they call their satellites) are designed and built. The company has deeply embraced agile development thinking – adopting a rapid, iterative, modular and inexpensive approach to spacecraft design. Where a traditional spacecraft might take years to plan and build, Planet Labs can assemble Doves in a matter of weeks. This highly efficient, swarming approach to design and innovation ensures that the company can continuously upgrade and improve, in much the same way that apps and websites are. (n.b. This cinches it – if you can do Agile in space, you can do it anywhere.)

Planet Labs is not only bringing a new product, but a new ethos to space. I’m thrilled to be advising the company and working with them closely in the months to come.

February 12, 2014

Cooking, Nursing and Making

Like millions of people across the world, I’m an enthusiastic amateur cook. I pore over cookbooks and recipes for fun, constantly scanning for opportunities to learn, experiment and build new skills. In service to these experiments, I regularly handle potentially dangerous materials (like uncooked meat) and equally dangerous technologies (like sharpened knives and open flames), which might, if mishandled, seriously harm or even kill me. Then I put the results of these experiments into my body, and into the bodies of the people I love most in the world.

I can do all of this because cooking is one of humanity’s few truly democratized forms of practice. As an amateur cook, I don’t just have permission, but encouragement to experiment, fail and innovate – all in the service of learning and improving. Cooking places me in a dialogue with my culture, my region’s food traditions and agricultural practices, the seasons, family history, current social trends and contemporary scientific understanding, as well as with a thriving global community of cooks, who happily share all kinds of tips, tricks and techniques.

To cook in this way requires no special licensing from the government, or the taking of tests or paying of dues, or swearing to uphold a certain code of conduct. (Although it does sometimes involve swearing.) If I were ever to decide to cook professionally, the state mandates primarily that I keep a sanitary kitchen, not that achieve a certain consistent level of quality or that I prepare a set of sanctioned dishes.

In all of this, I am representative of the vast majority of the world’s cooks, only the tiniest fraction of which will ever be ‘professionals’. (Indeed, purely as a matter of statistics, it’s likely that most of the world’s best cooks are amateurs.)

The results of this system are pretty wonderful. Every day, human beings consume billions of delicious meals, prepared by themselves and others using an incredibly vast array of techniques, without incident.

Yet the results are not universally benign. Each year, some people get sick, and some even die from things cooked by themselves or others – whether from a single undercooked shrimp or from the accumulated effects of too many cheeseburgers. We tolerate these outcomes as acceptable risks – understanding them to be the cost of having a wide variety of food choices, and trusting ourselves to make them.

Not every field is so democratic – and some that were once more participatory have become intensely professionalized. Such is the case in healthcare, another ancient field where, as with cooking, people employ potentially dangerous technologies and and put things in the human body, with mostly (but not universally) good outcomes.

Healthcare is, in contrast to cooking, the hard-won realm of professionals. The government and medical bodies tightly control the license to operate. One cannot be a ‘hobbyist’ doctor, as one might have in the distant past; by and large, one must participate in the professional ecosystem of healthcare delivery or not at all.

This may seem like the appropriate and natural order of things, but it was not always thus. The professional, institutional delivery of health and medicine as we experience it today took centuries to develop, taking much of its modern form only in 19th century with the advent of professional medical associations, credentialing and licensing processes, the differentiation of specialists and general practitioners, the codification of medical ethics and the standardized delivery of care in hospitals. (Many great medical journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine and the Lancet all date from this period; the American Medical Association was founded in 1847.)

Much of this effort was spurred not only by a desire to ensure higher quality outcomes, but to suppress competition from a sea of unqualified competitors, and to normalize the interactions and expectations between doctors, specialists and patients. The highly professionalized, highly specialized and highly institutionalized model of healthcare we have to today is the product.

How well does this system innovate? It might seems strange to even ask the question, given that we’re living through a veritable Cambrian explosion of medical innovation, from personalized cancer therapies to point-of-care diagnostics.

But as wonderful as these innovations are, they represent the work of a very specific segment of the healthcare field, with an equally specific set of incentives and motivations. Innovation in today’s healthcare system is often arduous, expensive, and typically undertaken by only by a narrow set of commercial interests; not even everyone in the formal system gets to participate. Partly, this is due to the understandable (and commendable) instinct to avoid harm and quackery; partly it’s because the stakes and costs of insuring against failure are extremely high; partly it’s because new innovations arouse the natural, protective instincts of incumbent organizations and bureaucracies; and partly it’s because there’s a lot of money to be made.

In some cases – as with drug discovery and the development of very advanced technologies – the huge capital risks involved (and equally huge potential benefits to humanity) absolutely warrant this kind of outcome. But in many other circumstances, the results are less inspiring. When only a chosen few get to innovate, the results often end up just being more expensive than they have to be, not necessarily better. The problems that get addressed are often the ones that have the most significant potential for financial return, rather than the ones that solve the most acute medical needs in the most cost-effective way. Worse still, channeling innovation into a few officially sanctioned corners retards the growth and spread of innovation in the field as a whole, by discouraging a wider array of voices and perspectives.

I was thinking of all this when I watched the following video, which has been making the rounds online lately:

The video shows a small and typical example of knowledge sharing in the nursing field – how to create remove a ring from a swollen finger. It’s exactly the kind of noncommercial sharing of technique that is perfectly commonplace in cooking; yet has become less encouraged in fields like nursing, which is, paradoxically, the field closest to the actual delivery of care.

It wasn’t always like this. A scan of the back pages of The American Journal of Nursing from the 1940s and 50s shows lots of sharing of what we might today call nursing “hacks” – clever, unconventional uses for products, and DIY, jerry-rigged devices all invented to improve patient care, and make nurses’ jobs easier.

They include innovations like “a simple wire contrivance … used to hold drainage bottles on the patient’s bed” and “an apparatus for rinsing baby bottles, designed by the nursery staff, made of several copper pipes welded together … that could rinse fifteen baby bottles at one time”.

These innovations – products of a less bureaucratic, less litigious, and, one assumes, less market-oriented time in medical innovation – are answers to problems which nurses encountered (and still encounter) every day. Now, as then, nurses are loaded with this kind of tacit knowledge and insight – hard-won observations from the trenches about what is needed and useful. Every day, working outside the limelight of the “professional” innovation discussion, they are quietly fabricating solutions to many challenges on the front lines of patient care.

The challenge is to channel and amplify all of that latent creativity to best effect. That’s just what MIT researchers Jose Gomez Marquez and Anna Young, at the Little Devices Lab are attempting to do with MakerNurse – a project that brings together nurses with the right support and tools to unlock their tacit insights and give expression to their creative solutions. (The examples already documented by the project are impressive – ranging from pediatric nebulizers to reusable tracheostomy collars.)

This is work that assumes the natural inventiveness of the nurses themselves as a starting point. Helping them take their ideas further might then mean helping them understand and use the fabricating technologies needed to develop and prototype their ideas; sometimes it might mean pairing them with professionals who can help them refine their insights; sometimes it might mean helping them find a wider audience for their solutions; and sometimes it might just mean helping them find one another.

In addition to these worthy goals, the MakerNurse project is a great example of how the Maker movement will likely grow up. Once seen mostly as the provenance of techno-hobbyists and entrepreneurs, it will smuggle not just the tools, but the ethos of distributed innovation into entire fields of human endeavor.

In the process, it will enable and ennoble professionals on the front lines and amplify their creativity and effectiveness. And it should act to keep the costs of needlessly expensive innovations in check. A healthcare system that empowers MakerNurses is one that is better designed, more humane, cheaper to deliver, with happier providers and customers, and better outcomes. So too is airline industry with MakerAirlineAttendants, and an educational system with MakerTeachers.

We need a “Maker_____” project – and more cooks, and more kitchens – in every industry.

November 1, 2013

Anchor Me Here

Superstorm Sandy and its aftermath provoked many marvelous storytelling projects. Few capture the emotional core of the experience better than Anchor Me Here, a beautiful, five-minute short film by Laura Egan that serves as an homage to the residents of the Rockaways:

Shot with a special high-speed, high-fidelity camera, Anchor Me Here captures community resilience, wordlessly and perfectly, through the eyes of families, first responders, fishermen and leaders of faith.

One of the residents who make a significant appearance in the film is James “Frank the Fish” Culleton, one of the last commercial fishermen and charter boat captains in the Rockaways. Already challenged by slower economic forces affecting his 30-year livelihood, Culleton was wiped out by the storm in a single night. One year on, he remains a Sandy migrant, moving from place to place, in seemingly endless limbo.

For the past year, Brooklyn-based photographer Jonah Markowitz has been documenting Culleton’s life, and that effort resulted in a moving multimedia and photographic narrative of Culleton’s descent into purgatory, as well as a first-person account from Culleton himself called “Riding Out Sandy in the Rockaways,” which appeared recently in the New York Times.

Markowitz has set up an Indigogo campaign for Culleton, called Reeling to Recovery, which seeks a mere $7500 in funds to enable him to buy a motorhome, and the first steps back to stability and dignity. About half has been raised already – I urge you to support it.

October 27, 2013

The Verbs of Resilience

In the course of conversation with leaders, practitioners and critics, I sometimes encounter a set of questions about resilience thinking that unfold along the following lines:

Resilience (of the right things) seems self-evidently valuable, but is it more than a buzzword? If so, how do we put it into practice? What exactly do we do for people, systems and organizations to help them become resilient? And how do we measure the progress of our efforts?

These are trenchant questions. If resilience is to have real and lasting utility, we need models for it that can guide action, that can be rigorously characterized, implemented and measured and that are portable (within reason) from one circumstance to the next.

Before proposing any such model, however, we must acknowledge a complicated semantic mess. Today, the term “resilience” is used in a number of different, and sometimes conflicting ways: first, to signify a cultural and personal value in the society at large (one with a presumed, particular resonance in the American psyche); second, as a neutral property of systems and people (a usage that suggests that a given characteristic might be perversely resilient as much as positively so); and finally, as an affirmative goal in the face of risk, in domains as diverse as urban planning, climate adaptation, organizational design, psychology and disaster response, to name just a few. Amid this thicket of sometimes-divergent, sometimes-overlapping contexts, parties often use the same words to mean different things, and different words to mean the same thing.

To avoid confusion, we must carefully situate ourselves, and declare and limit the scope of our interests. Suitably, in this essay I’ll be referring to resilience in the “property of systems and people” context noted above, to describe the (mostly) beneficial ability to persist, recover or even thrive amid disruption.

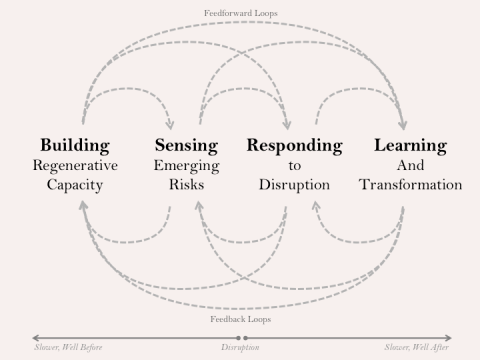

Below is a simplified model of resilience, inspired by principles articulated by the Danish systems researcher Erik Hollnagel, that decomposes the concept into four, concurrent clusters of verbs — the things that constitute the “doing” of resilience. The clusters are focused on building regenerative capacity, sensing emerging risks, responding to disruption, and learning and transformation. Whether in a city, a group of neurons, a social-ecological system, a community or even a person, resilience is often found in context-specific variations of these activities.

Like any high-level framework, the above model sacrifices some nuanced truths for broader ones. It is not intended to express every detail, but to help us to explore common processes, linkages, metaphors and tradeoffs found in many circumstances.

This model posits moderate disruptions as a necessary, if painful mechanism by which systems are tempered, adapt, learn and reorganize. A resilient system isn’t one in which failures never occur; it’s one in which disruptions engender a healthy response — one which enables a system to “bounce forward” as much as bounce back. It is further assumed that there are epistemic constraints – limits to what we can know and prepare for in advance – and that surprises are inevitable, and that we’ll make mistakes.

Another important feature of the framework is concurrency — a truly resilient system (or community, or person) is engaged in all of these activities all the time, albeit with different emphasis from moment to moment. Each activity influences the whole; it’s the connections between these activities that imbue the system with dynamism and adaptability.

~

The first “cluster” of activities in the framework is focused on building regenerative capacity. This is typically comprised of longer-term, slower processes of healthy growth and regrowth. In a community, for example, its relevant verbs might include creating access to shared resources, fostering entrepreneurialism and personal freedom, ensuring access to learning, training and education, promoting good local governance, healthy institutions and strong social networks, affirming social coherence, social memory, trust and cooperation, nurturing tolerance for diversity, and reinforcing mechanisms for meaning-making and healing. At its pinnacle, such capacity expresses itself as creativity, imagination and foresight — the ability to improvise, envision new and different arrangements, and to rehearse for an uncertain future.

These are the sorts of competencies that are essential for thriving, livable and healthy communities — and they’re also the ones that help ensure an adroit response to disruptions when they occur. Indeed, when these capacities are present, what might at first appear to be an impoverished community may, under duress, show surprising resilience. When they are absent, even an apparently wealthy community may demonstrate surprising fragility.

An analogous set of capacity-building processes occurs in many natural systems. Healthy ecosystems are comprised of complex interactions between species, shaped by competition and reciprocity, and moderated by geophysical cycles. Together these interactions, and their corresponding nutrient flows, enable the ecosystem to function, and to produce (and reproduce, when needed) abundant natural capital.

When an ecosystem’s functions are well — and diversely — met, not only does the ecosystem flourish — it can often cope with even severe disruptions and recover. However, when those same functions are poorly or narrowly fulfilled, the ecosystem becomes more fragile, and may be readily tipped past a threshold where healthy regrowth can no longer occur.

Human societies have long relied on the regenerative aspect of ecosystems as a self-replenishing form of infrastructure. That’s one reason why, for example, the loss of wetlands and oysterbeds in coastal estuaries has drawn so much concern in recent years: these systems provide self-repairing, extreme-weather “shock absorbers” for the human (often urban) settlements to which they are connected. Their absence concentrates and amplifies the destructive power of storms like Katrina and Sandy.

Regenerative capacity building not only happens at the grand scales of societies and ecosystems, but also at the most intimate levels of our human psyche. It is the continuous product of our skillful learning, and the result of our overcoming moderate life stressors on our way to greater levels of self-mastery, self-confidence and belonging. When we develop this kind of capacity, greater agency and self-advocacy follow, along with deepened senses of mindfulness, creativity and reciprocity that are key to personal resilience. Without such capacity building, many of these same qualities can wither, replaced by a sense of worthlessness, dependency and a loss of stakes in the future.

In all three contexts — communities, ecosystems and individuals — we must seek to understand the health — or apithology — of each of the underlying systems that produce capacity, not just the capacity present in the system at a given moment in time. It is not trust, but the capacity for creating trust; not ecological integrity, but the mechanisms for producing and restoring it; not learning, but the systems that ensure people’s access and engagement with it that we must understand, measure and encourage to build resilience.

Also, many of these capacity-building [OW1] mechanisms are deeply entwined and can’t be addressed in isolation. Certainly, for a time, wealth might be created through the exploitation of some cache of natural capital, or through the labors of marginalized people, but over the long-term, predicating capacity building in one domain on its systematic erosion in another simply moves fragility from one place to another.

However, done well, many capacity-building efforts have convergent benefits across domains. An inclusive community engagement process might, for instance, build trust, improve ecological stewardship, produce greater economic activity, and build the psychosocial resilience of its citizens — making possible what placemaking expert Milenko Matanovic calls “multiple victories.”

Our first step in building social and systemic resilience is to map, measure and encourage these underlying healthy, generative and restorative processes that operate when the system is undisturbed.

~

The second “cluster” of activities in the model is sensing emerging risks. Here we ask: how do we instrument a person, a community, a social-ecological-system or a city to listen for change?

Listening requires us to attend to signals, and some of those are as old as life itself. In an ecosystem, dramatic change may be foreshadowed by a subtle shift in the behavior of a key species, or in longstanding ecological rhythms. In communities, new economic patterns, the spread of certain behaviors, or even new modes of artistic expression may suggest the same. Attending to these kinds of changes is a craft as sophisticated and subtle as the changes being listened for — a skill that requires us to be fully present, and to listen closely without judgment.

In more contemporary systems, new innovations in sensors, data science, and informatics provide us with powerful new ways to listen for change, whether through distributed devices that help civic leaders better see and manage urban flows, crowd-sourced crisis-response platforms that help citizens self-organize in the face of disaster, or satellite imagery that measures the human footprint. These tools not only sense new kinds of phenomena, but produce novel, hybrid indicators — letting us see how, for instance, a change in patterns of mobile phone usage might presage a shift in the economic or physical health of a community, or make clear how a shift in food prices might correlate with a spike in political unrest.

Whether technologically mediated or not, this kind of sensing works by making the invisible visible. Sometimes, this process uncovers aspects of reality that were previously inaccessible; other times it reveals facts that were more intentionally obscured. Either way, it brings us closer to reality, and closer to the truth, which is the first step toward greater engagement and resilience. For we can’t mitigate, adapt to, or resist what we cannot see.

Of course, we must also understand what we see, which requires specialized interpretive abilities that are still not widely distributed. Thankfully, new organizations are rising to help promote data literacy in the kinds of organizations that care for vulnerable people, communities and systems. Particularly in such contexts, its not just literacy, but data ethics that must also be a paramount concern.

Systems scientists are also identifying new kinds of signals that might presage a disturbance. For example, just before a disruption occurs, many systems may experience synchrony, as agents within them briefly behave in lockstep just before being thrown into chaos. Synchrony can be seen in the brain cells of epileptics, for example, minutes before the onset of a seizure, and it was evident in the financial markets prior to the financial crash of 2008. Conversely, before a threshold is breached, systems may also manifest a phenomenon called critical slowing, becoming unstable and having difficulty returning to equilibrium. Both synchrony and critical slowing are examples of outlier levels of volatility — either too much or too little — that may portend disruption.

To be clear: We will never be able to detect every signal among the noise, nor can we even be sure we will know, beforehand, what we should be listening for. Some disruptions will arrive with little warning, and some can’t be listened for at all.

Even so, undertaken in the proper spirit, efforts to sense emerging risks can be their own form of capacity building. That’s because listening for any form of change promotes mindsets and relationships that are essential to responding to every form of change. In any such effort, most of the important questions are sociological, not technological: How do we pick the right signals to listen for? Who does the listening? How do we decide the threshold at which a signal should be actionable? How do we safeguard against false positives? How do we ensure signals will be heeded — particularly when doing so might be unpalatable for a particular interest group? How do we certify that the information contained in such signals is used respectfully and inclusively, and not as a tool to further amplify underlying inequities? How can we be confident of our own ability to respond to change?

Answering these questions takes more than getting good and timely data — it requires us to develop a whole portfolio of tools, activities and processes for paying sustained attention to potential disruptions, engaging the right stakeholders and institutions, developing a shared sense of the consequences and taking appropriate actions.

Effective sensing also requires two closely aligned, subsidiary skills: the ability to anticipate new potential risks, and to rehearse our responses to them in advance. Anticipation and rehearsal are strengthened through exercises like war games, preparedness drills, scenario-based exercises, and, increasingly, serious games. All of these are designed to improve decision making under uncertainty, and to encourage us to eliminate foreseeable risks where possible, and to mitigate the impacts of risks that cannot be avoided.

It’s worth noting here that our own cognitive biases play a significant, typically limiting role in our ability to sense and socialize emerging risks. As psychologist Dan Gilbert has pointed out, human beings are extremely attentive to short-term, quickly-moving, narrative, personified threats, particularly those, like terrorism, that involve the breaking of a moral taboo. We are far less responsive to slow moving, more abstract and less narrative forms of change, like climate change or growing income inequality.

This is why storytelling is also a vital part of sensing and socializing emerging risk. Stories dramatize less obvious, but no less impactful forms of change to which human beings are less naturally sensitive, and can help build context and momentum for action. Increasingly, we need the ability to build and tell stories with data.

As we can see, “sensing emerging risks” comprises a whole suite of verbs: assessing risks, establishing mechanisms for listening, interpreting potential signifiers of change, ensuring that these signals are properly understood, building processes for anticipation, rehearsal, and storytelling, and, when necessary, taking appropriate action.

~

The third “cluster” in the model is responding to disruption. Here we ask, how do we ensure a person, a community or a system responds and recovers effectively after an unforeseen shock?

It should go without saying that a healthy response to disruption such as a natural disaster requires timely delivery of material, information and support, delivered in as inclusive and efficient a way as possible. This support is not only essential in its own right, but sends a strong signal of care, concern, dignity and respect.

Yet there is also a direct correlation between the health of prior capacity building and risk-sensing practices, and the nature and quality of response to a disruption. Healthy communities, systems and people are far more likely to produce or participate in their own effective responses, rather than be wholly dependent on external help.

For example, an analysis by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research commissioned by the Rockefeller Foundation found that, other things being equal, communities that lacked trust and social cohesion recovered more slowly after Superstorm Sandy than did neighboring communities. That’s because trust and cohesion help us turn self-concern into empathy and compassion — to see ourselves in the other — which in turn helps promote mutual aid when it’s needed most.

This cooperative dynamic shapes our responses in other, subtler ways, too. In numerous field experiences, the most effective responses to disruptions we’ve encountered are not fully-rehearsed, off-the-shelf recovery plans from formal institutions, but rather adhocratic responses comprised of a mix of public and private efforts from local, national and international organizations, informal social networks, government agencies, volunteers and citizens, social innovators and technology platforms, all working together in highly improvisational, spontaneous, and self-organized ways. Each disruption and circumstance is unique, and there is no prefabricated organizational chart for the players — indeed, one of their first tasks is to create it.

Adhocracy is characterized by informal team roles, limited focus on standard operating procedures, deep improvisation, rapid cycles, selective decentralization, the empowerment of specialist teams and a general intolerance of bureaucracy. It’s well suited to the earliest moments of response to a disruption, when you don’t know exactly what you’re dealing with, and a valuable complement during subsequent recovery, when more standard operating procedures often take over.

Technology can support healthy responses in several ways. First, digital technologies enable the dissemination of timely and accurate information, which is often the first casualty in a disruption, and the encouragement of appropriate behaviors. It allows for the discovery of services, the coordination of both self-organization and external support, and the allocation of resources to the places that they’re needed most. Digital services that deliver such services are increasingly interoperable, enabling rapid, plug-and-play, Lego-like development of tools that provide just the services that are needed in a given circumstance.

This is all well and good, as long as we have the electricity and connectivity needed to power them – and that’s the second area where technology has an important role to play. As part of a ‘micro-everything’ revolution, engineers have been developing small-scale, rapidly-deployable neighborhood-level utilities: portable microgrids that provide energy, and wireless mesh networks that provide communications and connectivity when more traditional systems fail.

Finally, technology promises new ways to deploy productive capacity — the ability to make and produce assets where they’re needed most. Although still rapidly evolving, distributed manufacturing via 3D printing and “fablabs” will certainly be used in the future to help a community produce some of the assets it needs, before, during and after a disruption, right on the spot.

Of course, it’s not just the infrastructure we care about most in a disruption – it’s the people. In a recurring motif, many forms of personal capacity developed before a disruption shape our individual ability to cope and respond after it strikes.

Psychosocial resilience has many correlates, including the strength of our social networks, our access to resources, the quality of our most intimate, pair-bonded relationships, our physical health (particularly our brain health), our beliefs and our habits of mind. Many of these can be encouraged: in particular, mindfulness practices, even those taught after a disruption, have been shown to dramatically improve emotional self-regulation, and limit the long-term, damaging psychological (and physiological) effects of high-stress circumstances. Many people also find restoration and resilience through commemoration and healing rituals, and engagement with the natural world.

Unfortunately, stress doesn’t just come from the loss and grief that are often associated with disruption — it can also come from prolonged exposure to the bureaucracy that accretes in its aftermath. In the transition to recovery, competing interests and murky jurisdictional issues create a morass of complexity and red tape — the experience of which can rival the initial disruption in its stressfulness and disorientation. We can and must redesign the interface between individuals and institutions involved in response and recovery.

These capacities, of adhocratic cooperation, improvisation and self-organization; timely and effective dissemination of information; attendance to not just the physical but the psychosocial dimensions of response; and the redesign of bureaucratic interactions are all fruitful places where we can amplify the effectiveness of response.

~

The final cluster in the model is Learning and Transformation. Here we ask: How do we effectively learn from disruptions? When do we decide to gird a system against future risks, and when do we decide to transform it altogether?

If disruptions are the mechanisms by which systems learn, adapt and grow, we must ensure we take the right lessons from them. That requires putting in place inclusive processes for honest analysis, reflection and, when needed, structural change.

Disruptions are painful, not only for the damage they incur, but for what they can sometimes reveal. Like the geological patterns in rocks, they can lay bare our long, accumulated history of prior decisions, social arrangements, prejudices and fragilities. As Neil Smith aptly put it:

It is generally accepted among environmental geographers that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. In every phase and aspect of a disaster — causes, vulnerability, preparedness, results and response, and reconstruction — the contours of disaster and the difference between who lives and who dies is to a greater or lesser extent a social calculus.

This observation provokes a host of questions: when should we decide to improve the resilience of a vulnerable community, and when should we decide that their vulnerability is morally unacceptable, and then work to transform the system altogether? Who should decide such a thing? On what basis? And by what means?

For example, during Superstorm Sandy, low-income public housing units, many of them located on previously undesirable plots of land on what was once a working waterfront, flooded, ruining the boilers that provide heat and hot water to residents. Is the proper response to flood-proof the basement, move the boilers to the roof, or to decide that concentrating vulnerable people in flood-prone areas is no longer an option?

Another example: in many other parts of the world, smallholder farmers, who tend tiny plots of land, do most of the farming. These farmers work in near-subsistence conditions, have extremely low labor costs, and face significant risks from a changing climate — they are sometimes only one extreme weather event away from disaster. Is the best response to this to insure these farmers financially against climate volatility? Or to rethink the smallholder system altogether?

These questions are ones, ultimately, of framing and politics, and there are no obvious answers. They highlight unavoidable tensions between the need for social cohesion, inclusive decision making and the need for sometimes unpalatable forms of risk mitigation, even if they lead to positive, even transformational outcomes. The success of such efforts rests not just on post-mortems, but also on inclusive coalition-building, strong formal and informal governance, and credible leadership. All of these things need to be in place for learning and transformation to occur.

~

Each of these four clusters – and the linkages between them – represent important places where we might intervene to improve resilience. Of course, the verbs in each will always be context-specific, and we may never be able to understand all of the dynamics beforehand. This is why we must embrace what F. David Peat calls ‘gentle action’ – spending as much time as possible understanding and illuminating a system, designing reversible interventions and experiments ‘with, not for’ its stakeholders, before embracing larger wholesale change.

It should be clear that, human (and technological) energies being finite, there will also be tradeoffs between how much we can invest in any of the activities presented above. In some communities, we may find strong regenerative capacity, but little ability to listen for change. In others, we may find strong response mechanisms, but little capacity for anticipating new forms of risk. To build resilience is to work in the shadow of the system’s dominant capacities and culture, strengthening its weaker elements.

Third, timing matters. In this model, the “outer” processes — of building regenerative capacity and learning and transformation — are slower than the “inner” processes of sensing emerging risks and responding to change. Because it takes time for the system to recover and adapt, it is the cadence, not just the severity of disruptions, which shapes resilience. Moderate disruptions, moderately spaced, may keep the system in a place of healthy response and renewal. More frequently spaced, their effects can accumulate and become a system’s undoing.

This model has resonated with researchers and practitioners in a wide variety of resilience-related fields, and, excitingly, with citizens and community members as well. It has demonstrated its value as a framework for comparing approaches and strategies found in different contexts, as a powerful way to get new people into the resilience discussion and to widen the aperture of the resulting dialogue. Feedback on it is welcome!

Note: a version of this essay is included in PopTech’s “The City Resilient” Edition, and contains elements which first appeared in “Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back.”

September 15, 2013

Poetry in the Cloud

The artist Doris Mitsch is best known for her gorgeous, super-high-resolution scanner-based images of natural subjects like flora, birds nests and sea creatures. These are not photographs in the traditional sense, but an alternative way of capturing images, as both the scanner lens and light move over the object to produce a composite with luminous, ‘impossible’ lighting conditions. (Disclosure: I am the happy owner of several of these.)

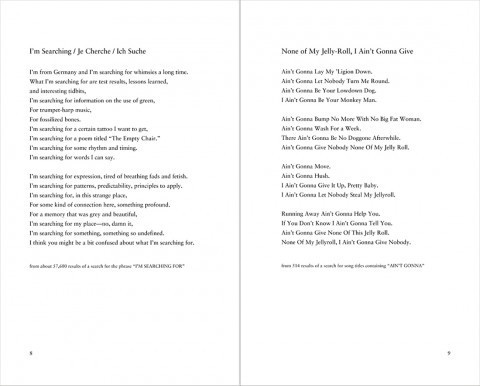

Now, Mitsch has assembled an equally remarkable work of poetry, entitled I’m Searching For Something So Undefined: Poetry Found in the Cloud, which seems perfectly in tune with the digital zeitgeist. I say ‘assembled,’ rather than ‘written’ because she didn’t actually write a single line of these compelling pieces. Instead she knit them together from found fragments of online content, all derived from Google searches – like the title piece, I’m Searching / Je Cherche / Ich Suche, which you can read by clicking below:

I’m Searching / None of My Jelly Roll, I Ain’t Gonna give (Click to Enlarge)

Each line of the poem was extracted from the roughly 57,600 results Google returned for the phrase “I’M SEARCHING FOR”.

Knowing the manner of composition encourages the reader (this one, anyway) to continuously flicker between three ways of reading: first, considering each line individually – wondering about its original author and context; then, collectively, as some expression of the ephemeral, “Internet moment” from which they all derive; and then finally as an entirely new poetic construction, with its own cadence and meaning. In some ways, reading these poems feels a lot like using the Internet itself, as our surfing yields hobbled-together brief constellations of meaning, cobbled together from vast patterns of inchoate data.

Most ‘data art’ takes the form of beautiful, algorithmic arrangements of pixels on a screen – a medium that is so new the tools to produce it are still being invented. Mitsch’s poems, by contrast, manage to embed the Internet in one of our most ancient media, yet with results that are no less revelatory.

You can (and should!) buy a copy of I’m Searching for Something So Undefined, along with the several other beautiful books by Doris Mitsch, available on Blurb.

August 26, 2013

The Qualified Self

My colleague Robyn Brentano at the Garrison Institute recently shared a Buddhist parable with me, which is retold in the book Eight Steps to Happiness by the renowned teacher, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso:

In Tibet there was once a famous Dharma practitioner called Geshe Ben Gungyal, who neither recited prayers nor meditated in the traditional posture. His sole practice was to observe his mind very attentively and counter delusions as soon as they arose. Whenever he noticed his mind becoming even slightly agitated, he was especially vigilant and refused to follow any negative thoughts. For instance, if he felt self-cherishing was about to arise, he would immediately recall its disadvantages, and then he would stop this mind from manifesting by applying its opponent, the practice of love. Whenever his mind was naturally peaceful and positive he would relax and allow himself to enjoy his virtuous states of mind.

To gauge his progress he would put a black pebble down in front of him whenever a negative thought arose, and a white pebble whenever a positive thought arose, and at the end of the day he would count the pebbles. If there were more black pebbles he would reprimand himself and try even harder the next day, but if there were more white pebbles he would praise and encourage himself. At the beginning, the black pebbles greatly outnumbered the white ones, but over the years his mind improved until he reached the point when entire days went by without any black pebbles. Before becoming a Dharma practitioner, Geshe Ben Gungyal had a reputation for being wild and unruly, but by watching his mind closely all the time, and judging it with complete honesty in the mirror of Dharma, he gradually became a very pure and and holy being. Why can we not do the same?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this story lately, as I’ve been undertaking a learning journey with an iPhone app called Expereal.

The program is a sort of 21st-century update on Gungyal’s pebbles, intended to promote self-reflection. Once installed, at regular intervals throughout the day, Expereal asks you a simple question:

“How are you feeling right now?”

In response, you turn an onscreen dial, providing a subjective rating from 1 to 10. As you move your finger, a corresponding inkblot grows in size and color on the screen, from a subdued blue dot to a bursting crimson splash. (The precise meaning of these kinesthetic ratings is left for you to decide.)

Your responses can be further annotated with notes and photos detailing where you were when you made them, and with whom. Expereal also allows you to chart your assessments over time, and (of course!) compare yourself to friends and fellow users:

The app owes much to its conceptual forebears, like designer Nicholas Felton’s personal “annual reports”, in which he details various aspects of his experiences and interactions with people over the course of a year, and to various other Quantified Self efforts.

But there is something qualitatively different here, and it starts with nature of the question itself. How often do we actually, genuinely attend to our own feelings? (An A-type New York friend joked, “I can’t do that and keep living here.”) How often do we seriously ask others how they’re feeling, or get asked in return? Once a day? Once a week? And how well do we remember how we were feeling last Tuesday? Last month? Last year? Like the inky stains on the wineglasses after a party, these countless subjective states have somehow left their traces in us, but who can remember the taste?

Unfortunately, being given the opportunity to answer the question doesn’t necessarily mean that one will do a good job actually answering it, especially at the beginning. The first hundred or so times Expereal asked me how I was feeling, my assessments were the kinds of superficial ones you might respond with if a stranger asked you on the street: “I’m fine.”, “All good.”, “Frustrated by a supermarket line.” Reviewing my answers after the first few weeks, it dawned on me: I had been politely lying to my smartphone. There’s a humbling moment.

So I recommitted to answering the question less glibly. How was I feeling right now?

The ‘real’ answers were harder to get to, and often more surprising when they arrived. Much of the time, I didn’t really know what I was feeling – it was hard to pin down what largely felt like an ephemeral mishmash. Expereal rarely found me living in the present moment – usually, my mind was occupied with a chorus of distant concerns or distractions. In the middle of a conversation, Expereal made me realize I wasn’t listening at all to my partner, or to myself, at all – I was just waiting, bored and impatiently, for my turn to speak. Ouch.

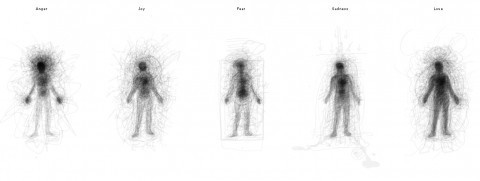

Pushing past such uncomfortable observations meant taking a short break, and attending more carefully and more holistically. And with practice I got better. I began to observe that whatever I was feeling, I was rarely feeling it just in my mind, it was in my body, too. – not just my hands, but my posture, the way I held my frame. I was reminded of a wonderful PopTech talk by the Irish designer Orlaugh O’Brien, about her project “Emotionally}Vague”, in which she collected and overlayed hundreds of people’s self-reported drawing of where they felt various emotions in their bodies:

The aggregate picture that emerged in the project is striking. People reported that anger was ‘felt’ in the head and hands, while love, by contrast, was felt all over. “Anger is a force, love is field,” said O’Brien. I certainly found the same.

More subtly still, I began to see how much of my own cognition was enactive, inextricably bound up in loops of perception and action, intimately connected to the systems that govern every modern life, including ones I had invented and taken on for my own purposes. The taxi, the railway station, the flickering of a neon light, the obligations to family and profession and countless other systems, objects and ideas all cycle through me continuously, leaving their stain, shaping my cognition and sense of self, in ways I had rarely attended to in the moment.

Answering the “How do you feel right now?” question over and over again has had other effects as well. It’s encouraged at least a little more generosity in me, made me modestly more likely to ask others how they are feeling, and ready to attend more carefully to the answers. Attending builds awareness, and awareness in turn is the pretext for empathy, generosity and equanimity.

~

Expereal is available on iTunes for free. You can read an interview with its creator, Jonathan Cohen, here. Note: a Facebook login is required to use the program.

August 9, 2013

The Birth of a Meme

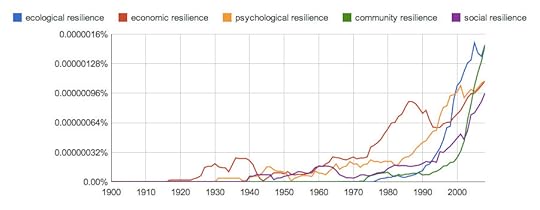

Google’s N-gram viewer allows you to watch the prevalence of certain words or phrases among the vast library of books that the company has been digitizing. As such, it’s a powerful tool for seeing patterns in our culture – so much so that it’s become a basic tool in the new field of culturomics, the computational analysis (and prediction) of human culture through the analysis of large-scales bodies of texts.

For example, use of the term resilience has more than doubled since 1990. More interestingly, here the graphs for five terms: ecological resilience, economic resilience, psychological resilience, community resilience, and social resilience:

You can literally watch the meme being born. (And a shoutout to my friend and colleague Charles Rutheiser for this idea.)

Andrew Zolli's Blog

- Andrew Zolli's profile

- 18 followers