Michael Lopp's Blog, page 23

March 19, 2018

A Performance Question

At some point in your leadership career, you’ll need to care about performance management. My first bit of advice is the hardest: don’t ever let yourself think or say the words “performance management.” This is impossible, but aspirational. I will explain.

My hard earned definition of performance management: a well-defined workflow that either leads to an employee’s improved performance or their departure.

The moment you say or think “performance management,” you leave regular management and the rules of engagement change. The natural way you interact and communicate with this individual become structured and unnatural. Easy going conversations become stilted oddly… timed. and strangely punctuated. Smart, charismatic humans will tell you, “This is part of being a manager.” These humans are right, and while there are leadership merit badges to be acquired during performance management, the ultimate badge is awarded when you don’t end up in performance management.

The situations resulting in performance management are as varied as the individuals involved in them, but I am steadfast in my advice. Do all you can to avoid the consequential mindset of performance management because once you’re there, reality changes.

The Checklist Sentence

In our 1:1, you start the conversation, “Nelson has been six months, and I do not see the sustained productivity. I am thinking about…”

I interrupt you, which is rude, but you were about to say performance management, and I can’t have that. I hold up one finger, and I ask the only question that matters:

“Have you had multiple face-to-face conversations over multiple months with the employee where you have clearly explained and agreed there is a gap in performance?”

It’s a big question so while you construct your answer; I am going to break down the question idea by idea and word by word because there are significant words and concept in that big sentence that humans like forget or ignore.

Multiple conversations. “Rushing it” – the classic bad entry path into performance management. For the reason that feels completely valid at the time, an eager manager decides to get real with an employee. They have one hard conversation that goes poorly, so they decide it’s time for performance management.

No. Also, no. Three substantive conversations – minimum. You need to give yourself time to explain the situation clearly, and you need to give them ample time to think about what you said and ask clarifying questions. Chances are, especially for new managers, that what they think they’re saying is not what is being said especially when the message is critical feedback. The second and third conversations are essential opportunities for communication error correction.

Face-to-face conversations. I gave them the feedback in an email. No, you just sent them an email with no opportunity to debate and discuss. Feedback is two-way communication, and when you are uncomfortably sitting there delivering complex constructive feedback, you can see with your eyeballs how they hear it. Email, Slack, and any other non-face-to-face medium is a hard situation escape route.

Many months. I used to be scared of flying. Takeoffs were the worst. I had a process of counting backward by seven by an arbitrarily large number I randomly picked to keep my mind off of my imminent death. It distracted me, but you know what helped my fear? Flying. A lot. For years.

Substantive changes to deep-rooted human behavior are often necessary to correct issues with humans that lead to performance management, and that means talking about those issues. Repeatedly. In different contexts. For months. I’ve handily tucked the most useful piece of advice in the middle of this article: give yourself months and months to discuss a gap in performance. Analyze it from different angles and make it about learning rather than a step on the road to performance management. This requires that your feedback is…

Clearly explained. If whatever the emerging performance issue had an obvious fix, you would just say to the individual, Hey, I asked for XYZ and got ABC. Let’s debug this together and figure out what happened. You are currently not in a situation where the path forward is obvious which is why you take the time to clearly explain the situation. You write it down before you say it. You ask a trusted someone to listen to your explanation and see if it resonates. Then, you clearly explain the situation to your employee.

Did it work? Maybe. There’s an easy way to find out.

And agreed there is a gap in performance The final clause in our sentence is the most important because if they don’t agree with your description of the situation, they aren’t going to act. How are you going to tell if they agree? You ask.

Is it clear what I’m describing? Did that make sense? Do you agree with my assessment?

The questions above asked within an aura of performance management sound entirely different than they are asked as a regular course of being a leader. The structure and formality of how I’m breaking down the performance question sentence might give you the impression I expect your conversation to be structured and formal. Nope nope nope. While there is pre-work in having these conversations, your attitude, your demeanor is that of a coach. If you’ve flipped the switch on performance management, your demeanor is that of the Grim Reaper, and that’s the difference between them thinking, “Oh, I get it. I know what I need to do” versus “Oh, I get it. I should be looking for a new job.”

What if they don’t agree? Great. What wasn’t clear? What did you hear me say? What data do I not have? You’ve begun a healthy and clarifying conversation where the stakes are not fire, or do not fire, but how can we figure out how to communicate and work better.

What if they still don’t agree? No problem, let’s agree to table this now. Give ourselves a week to both percolate on the conversation and pick it up next week in our 1:1.

What if they still don’t agree? I have to follow this path because you, as a leader, are going to find yourself two months into a conversation where either you’re not clearly explaining or perhaps they just don’t want to hear what you have to say. Performance management time, right? Wrong.

Try one more perspective. Write your feedback down1. This might feel like a formal step towards performance management; we’re still not there. We’re removing the interpersonal dynamics from the situation and focusing on the words transformed into sentences delivering a critical thought. Yes, there is a smidge of formality that comes with the written word, but in my experience, it comes with a higher chance of clarity.

Reality Changes

The reality is that you’re always managing performance. Your very existence as a leader sets one performance bar. How you act, what you say, how you treat others, how you work, all of your attributes influence how your team performs because you demonstrate what you value as a leader.

The performance management attitude I want you to avoid is the flip-a-switch “Well, now it’s time to get serious” approach with your team because in my experience it’s manager shorthand for “How do I let this human go?” rather than “How do I make this human better?”

There are very clear, obvious, and immediate situations where you let a human go. If they are stealing from you, you let them go. There are others, but the vast majority of the situations surrounding performance are fixable. The work is complex, uncomfortable, time-consuming, and often hard to measure, but it is during these hard conversations that you become a better communicator, you learn the value of different perspective, you build empathy, you become a better coach, and you become a better leader.

Yeah, I know I said don’t deliver feedback digitally. In the case you write feedback down, you deliver it face-to-face. ↩

March 5, 2018

How to Rands

Hi, welcome to the team. I’m so glad you are here at $COMPANY.

It’s going to take a solid quarter to figure this place out. I understand the importance of first impressions, and I know you want to get a check in the win column, but this is a complex place full of equally complex humans. Take your time, meet everyone, go to every meeting, write things down, and ask all the questions – especially about all those baffling acronyms and emoji.

One of the working relationships we need to define is ours. The following is a user guide for me and how I work. It captures what you can expect out of the average week, how I like to work, my north star principles, and some of my, uh, nuance. My intent is to accelerate our working relationship with this document.1

Our Average Week

We’ll have a 1:1 every week for at least 30 minutes no matter what. This meeting discusses topics of substance, not updates. I’ve created a private Slack channel for the two us of to capture future topics for our 1:1s. When you or I think of a topic, we dump it in that channel.

We’ll have a staff meeting with your peers every week for 60 minutes no matter what. Unlike 1:1s, we have a shared document which captures agenda topics for the entire team. Similar to 1:1s, we aren’t discussing status at this meeting, but issues of substance that affect the whole team.

You can Slack me 24 hours a day. I like responding quickly.

If I am traveling, I will give you notice of said travel in advance. All our meetings still occur albeit with time zone considerations.

I work a bit on the weekends. This is my choice. I do not expect that you are going to work on the weekend. I might Slack you things, but unless the thing says URGENT, it can always wait until work begins for you on Monday.

North Star Principles

Humans first I believe that happy, informed, and productive humans build fantastic product. I optimize for the humans. Other leaders will maximize the business, the technology, or any other number of important facets. Ideological diversity is key to an effective team. All perspectives are relevant, and we need all these leaders, but my bias is towards building productive humans.

Leadership comes from everywhere My wife likes to remind me that I hated meetings for the first ten years of my professional career. She’s right. I’ve wasted a lot of time in poorly run meetings by bad managers. As an engineer, I remain skeptical of managers even as a manager. While I believe managers are an essential part of a scaling organization, I don’t believe they have a monopoly on leadership, and I work hard to build other constructs and opportunities in our teams for non-managers to lead.

I see things as systems. I reduce all complex things (including humans) into systems. I think in flowcharts. I take great joy in attempting to understand how these systems and flowcharts all fit together. When I see large or small inefficiencies in systems, I’d like to fix them with your help.

It is important to me that humans are treated fairly. I believe that most humans are trying to to do the right thing, but unconscious bias leads them astray. I work hard to understand and address my biases because I understand their ability to create inequity.

I heavily bias towards action. Long meetings where we are endlessly debating potential directions are often valuable, but I believe starting is the best way to begin learning and make progress. This is not always the correct strategy. This strategy annoys those who like to debate.

I believe in the compounding awesomeness of continually fixing small things. I believe quality assurance is everyone’s responsibility and there are bugs to be fixed everywhere… all the time.

I start with an assumption of positive intent for all involved. This has worked out well for me over my career.

Feedback Protocol

I firmly believe that feedback is at the core of building trust and respect in a team.

At $COMPANY, there is a formal feedback cycle which occurs twice a year. The first time we go through this cycle, I’ll draft a proposed set of goals for you for the next review period. These are not product or technology goals; these are professional growth goals for you. I’ll send you these draft goals as well as upward feedback from your team before we meet so you can review beforehand.

In our face-to-face meeting, we’ll discuss and agree on your goals for the next period, and I’ll ask for feedback on my performance. At our following review, the process differs thusly: I’ll review you against our prior goals, and I’ll introduce new goals (if necessary). Rinse and repeat.

Review periods are not the only time we’ll exchange feedback. This will be a recurring topic in our 1:1s. I am going to ask you for feedback in 1:1s regularly. I am never going to stop doing this no matter how many times you say you have no feedback for me.

Disagreement is feedback and the sooner we learn how to efficiently disagree with each other, the sooner we’ll trust and respect each other more. Ideas don’t get better with agreement.

Meeting Protocol

I go to a lot of meetings. I deliberately run with my calendar publicly visible. If you have a question about a meeting on my calendar, ask me. If a meeting is private or confidential, it’s title and attendees will be hidden from your view. The vast majority of my meetings are neither private nor confidential.

My definition of a meeting includes an agenda and/or intended purpose, the appropriate amount of productive attendees, and a responsible party running the meeting to a schedule. If I am attending a meeting, I’d prefer starting on time. If I am running a meeting, I will start that meeting on time.

If you send me a presentation deck a reasonable amount of time before a meeting, I will read it before the meeting and will have my questions at the ready. If I haven’t read the deck, I will tell you.

If a meeting completes its intended purpose before it’s scheduled to end, let’s give the time back to everyone. If it’s clear the intended goal won’t be achieved in the allotted time, let’s stop the meeting before time is up and determine how to finish the meeting later.

Nuance and Errata

I am an introvert and that means that prolonged exposure to humans is exhausting for me. Weird, huh? Meetings with three of us are perfect, three to eight are ok, and more than eight you will find that I am strangely quiet. Do not confuse my quiet with lack of engagement.

When the 1:1 feels over, and there is remaining time I always have a couple of meaty topics to discuss. This is brainstorming, and the issues are usually front-of-mind hard topics that I am processing. It might feel like we’re shooting the shit, but we’re doing real work.

When I ask you to do something that feels poorly defined you should ask me for both clarification and a call on importance. I might still be brainstorming. These questions can save everyone a lot of time.

Ask assertive versus tell assertive. When you need to ask me to do something, ask me. I respond incredibly well to ask assertiveness (“Rands, can you help with X?”). I respond poorly to being told what to do (“Rands, do X.”) I have been this way since I was a kid and I probably need therapy.

I can be hyperbolic but it’s almost always because I am excited about the topic. I also swear sometimes. Sorry.

If I am on my phone during a meeting for more than 30 seconds, say something. My attention wanders.

Humans stating opinions as facts are a trigger for me.

Humans who gossip are a trigger for me.

I am not writing about you. I’ve been writing a blog for a long time and continue to write. While the topics might spring from recent events, the humans involved in the writing are always made up. I am not writing about you. I write all the time.

This document is a living breathing thing and likely incomplete. I will update it frequently and would appreciate your feedback.

Speculation: there is an idea in this document that’d you’d like your manager to do. Thesis: Just because I have a practice or a belief doesn’t mean it’s the right practice or belief for your manager. Suggestion: Ask your manager if they think my practice or belief is a good idea and see what happens. ↩

February 25, 2018

You’re Probably Underestimating What You Can Do With Your iPhone Home Screen

I wrote this short piece on the current state of apps on my iPhone. People started sharing their home screens and I was blown away. The full list can be seen here. Here are a few that I  .

.

February 19, 2018

iPhone Home Screen – Year in Review

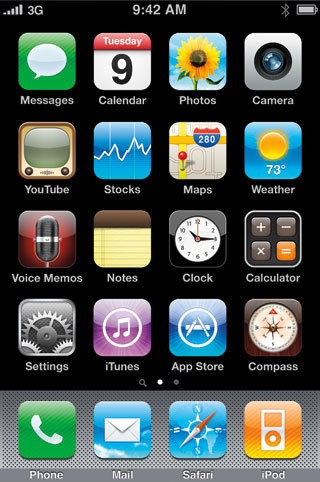

The first page of my home screen for my iPhone is a sacred real estate. It is the one screen where I carefully curate my apps. Placement and grouping are considered because the apps on my first screen are daily use apps. Here it is:

Because real estate is precious, each year I perform an annual reflection on this space. Apps are deleted or – worse – moved to the useless chaos that is anywhere else on my phone.

Before we get to the review, a few words on app placement. First, the dock is home for required applications and the place I spent the most time evaluating membership. For the first time ever, I moved the Phone app out of the dock and the Bear app to the dock. More on Bear in a moment. As for the Phone app? I don’t use the phone much anymore as it’s been mostly replaced by Slack and Messages.

As for the rest:

1Password continues to evolve and give me both a sense of security as well as insight into the health of my corpus of passwords. However. the process of finding and entering a password on mobile remains an incredibly high friction workflow. I paid for 1Password.

Google Maps & Waze? Google maps are better the Apple maps. Sorry Apple, but there have been far too many small little map errors that have eroded my Apple map confidence. Also, Google Maps allows me to download a section of a map for offline use which is handy for long bike rides in the middle of nowhere. Waze, yeah, it’s better for real-time car rides. Your mileage may vary.

Wunderground. Rands rule: I will always try any new monospaced typeface, productivity app, and weather app because I firmly believe these are unsolved problem spaces. While I continue to enjoy and trust the lens Dark Sky (Paid for it) provides into my day, and I particularly like the map (when it loads), the ten days graphed forecast in Wunderground is absolute gold. It reliably tells me both the arrival time, duration, and intensity of forthcoming weather.

Simple. Yup, I still use Simple for the Rands Slush Fund. Why? They continue to clean and, well, simple.

Snapseed and Camera+ continue to be my go-to apps for pre-Instagram image processing. 80% Snapseed, 10% Camera+, and 10% Instagram.

United. Because of miles. Not happy about it.

Tweetbot. Because of indie.

Strava. Because smaller more connected [villages] are bringing us a healthier internet. I have a lot to say about Strava in a future article. I pay a subscription fee for Strava.

Feedly. Because RSS is not dead. I pay a subscription fee for Feedly.

Spotify. Because I find iTunes to be UX nightmare. I pay a subscription fee for Spotify

Google Photos. This is a recent addition that has been on brain for years, but I have the same trepidation as I have with [using Chrome]. What is being done with my data? I could read the terms of service, and I’m reasonably confident Google isn’t sharing my photos with anyone because that isn’t what they want.

Here’s the “Things” album automatically created when I imported my current photo set into Google Photos:

Google doesn’t want to use my photos for anything other than training data. It allows them to learn which of my photos contains skyscrapers, forests, and cliffs. Yes, it’s creepy, but feature provides me unusual and unexpected value because of the variety of new lenses it provides my photo collection. It feels like magic. It’s not magic. It’s machine learning.

Photos Yeah, Apple’s Photos is still on the front page. Oddly, Google Photos doesn’t allow me to mark photos as Favorite, and I use that a workflow step in photo editing. I’m also hoping that Apple’s Photos improves.

Google Calendar Apple’s Calendar app is unreliable and I can not have my calendar not be rock solid. Google Calendar is fine, but I am fully prepared to be amazed by something else.

The four dock applications:

Bear The majority of my writing happens on Bear’s desktop application, but in a pinch, I’ll edit and write on mobile. Bear is the first application that I feel is best of breed on both mobile and desktop. It’s not with small flaws, but neither desktop nor mobile feels like second class. As a human who trades in words, Bear is a dock must-have. I pay a subscription fee for Bear.

Slack I work at Slack. Sooooooooo.

Messages Convenient and handy messaging with all my humans.

Gmail and final thoughts It is my great delight that there is very little mail in my life these days. Thanks, Slack. However, as I finish up this piece, I find it curious how much Apple is on the first screen of my iPhone X. Here’s the default home screen from the iPhone 3GS:

A full screen on the iPhone 3GS was 20 apps. A full iPhone X has 28.

My guess is 20 of the 20 apps on the iPhone 3GS were made by Apple. Yup, even YouTube. This makes sense since it was very early days for the iOS application ecosystem, but fast forward to my iPhone X and here’s the scorecard:

Number of “required” Apple system apps on the first home screen: 3 (System Prefs, App Store, and Phone)

Number of Apple apps still in play: 4 (Safari, Photos, Clock, and Messages)

Number of apps I paid for or am paying for via subscription: 6

Number of Apple apps that replaced with another vendor: 7 (Calendar, Maps, Weather, Notes, iTunes, Mail, and iPod)

Number of Apple-made maps replaced with Google equivalents: 3.5 (Google Maps, Google Photos, Google Calendar, and Gmail. I gave .5 for photos since I continue to use both apps regularly… which is weird)

You’ll notice in the bottom right corner I leave one spot open.1 I like to think that spot is in play. It’s a hopeful place waiting for the next app.

This is valuable real estate and if I could, I push that empty spot to the upper left, but the home screen hasn’t seen a significant design upgrade in, well, ever. ↩

February 8, 2018

Meeting Blur

Wednesday afternoon. 3:30. Tanya are I walking through a complex political scenario involving Product and Engineering. Nothing devious. Just complex. Many moving parts. I’ve had some version of this conversation five times today.

The whiteboard is my savior. I’m using it to draw a picture that anchors the core points of the situation. Those core points change from conversation to conversation, and I update the picture to capture this emerging reality.

The problem is, the picture captures my reality and not theirs. When it comes to complex political scenarios, you need to keep track of who knows what. Again, nothing nefarious. No ill intent. Just an honest attempt to shape the narrative productively.

Tanya says something important. Really important. It’s high on the Richter scale of thought, and I need to update my entire thinking in a moment. Problem is, I’ve had this conversation five times today, and suddenly I can not remember what was said by whom, when, and where.

Welcome to Meeting Blur.

Too Much

As a leader, you have disproportionate access to developments in your team and company. Nothing surprising here. You are the representative of your team, so you get invited to a lot of meetings for representatives. These meetings contain synthesized information about what is going down in the company right now.1

Because of your access to all this information and your disposition as a person who gets shit done, you sign up for things. Often you will sign up for too many things. Because your job is to get shit done, you often will be in denial about having too much to do. I want to talk about how I know I’m in this state and the unexpectedly dire consequences.

Meeting Blur. When the number of meetings exceeds your ability to remember what was said by whom, when, and where. Let’s forget for a moment why there are so many meetings2 and focus on your mental state. You’re a bright emotionally intelligent human. You walk into a meeting and have a credible mental profile of each human at the table. Why are they here? What do they want? How do they feel about the topic at hand? All of this information is front of mind and readily accessible.

This is what leaders do. We compile every single moment into a vast internal story about the state of the company. We use this informative narrative for good, not evil.

For me, Meeting Blur occurs when I can no longer compile these moments. The amount of incoming data exceeds my ability to compile the story. Wait? Does Tanya know this? No, Stuart said it this morning, and no one knows that thing, yet. Right? Maybe…

Blurred.

But I get shit done, I got this. This is a blur blip.

No, it’s not.

If I fail to recognize my overloaded mental state at the moment, I will undoubtedly recognize it later… in the middle of the night. My eyes pop open at 3:13 am like I’m in the middle of meeting with Tanya. I’m compiling, I’m working the problem, and my brain is fully engaged. In fact, it’s clear that my brain has been working the issue for some time, but it was 3:13 am when the compilation was complex enough to wake me.

For years, I diagnosed the 3:13 am wake-up call as stress. It is stress, but the root cause is bad leadership.

On the Topic of Operational Excellence

Let’s forget about the deleterious effects of not getting enough sleep and talk about why this is a leadership failure. You are about to violate leadership rule #8: “You sign-up for things and get them done. Every single time.”

When you achieve Meeting Blur, something has gotta go. Your plate needs at least one less big rock, and that means failing on a commitment. Sure, you can give the work to someone else or perhaps delay another project to give yourself breathing room. There are any number of time-saving moves you can pull, but remains a leadership failure because you do not have a good internal measure for what you can and can not do.

Leaders set the bar for what is and is not acceptable on their team. They define this bar both overtly with the words they say, but more subtly with their actions. There are two scenarios when you’ve achieved Meeting Blur and need to act. You can not change anything and do all of your work poorly, or you can drop some of that work which equates to a missed commitment. While I believe you agree the optics on both scenarios are bad, what is worse is that by choosing either course you signal your team that these obvious bad outcomes are acceptable.

Seem harsh? Yeah, I’m a bit fired up because I think leaders often vastly underestimate the impact of actions we consider inconsequential. Let’s play it out once more: Thinking I am responsible and helpful. I sign up for things. I do this repeatedly and sign up for too many things. Over time, I realize I’m in overloaded, so I miss commitments. Where’s the flaw? Because I could not initially correctly assess how much work I could do, I’m signaling to my team it’s ok to miss commitments. What?

Yes, I am glossing over the complexity of situations that are obviously more complex. There is always situational nuance. There is always complexity that is discovered only by doing the work. Given all of these guaranteed unknowns, a credible leader needs to work to be clear about one key variable: their own capabilities.

This is why when you go to these meetings, you must report back to the team. What happened? What’d we learn? What’s happening next? Everyone on your team knows this meeting happens, but only you know what happened. Share the knowledge. Free leadership points. ↩

Actually, let’s not. How many meetings are you having a day? How many people are in these meetings? Do they all need to be there or have meetings become the means by which forward progress occurs.? Shit, you have a problem. ↩

January 23, 2018

How to Write a Blog Post

Randomly think of a thing. Let it bump around your head a bit. If the bumping gets too loud, start writing the words with the nearest writing device. See how far you get. The more words usually mean a higher degree of personal interest. Stop when it suits you.

Wait for time to pass and see if the bumping sound returns. Reread what you’ve written so far and find if it inspires you. Yes? Write as much as you can. No? Stop writing and wait for more bumping.

Repeat until it starts to feel done in your head. If it’s handwritten, type it into a computing device. When you are close to done, print it out on paper. Sit somewhere else with your favorite pen and edit your work harshly. If this piece is important, let someone else edit harshly.

Transfer all of your edits into your piece. Enter your writing into your favorite publishing platform. Proof your final piece once more. Use Grammarly because the Internet is a cruel copy editor. Hit publish and tell yourself you don’t need validation. Wait for validation and once more wait until you randomly think of a thing.

January 15, 2018

Pitch Room: Fixing The Last Jedi

EXT. MORNING, MONDAY JANUARY 18th, 2016, LUCASFILM HEADQUARTERS, LETTERMAN DIGITAL ARTS CENTER, SAN FRANCISCO.

INT. THE BOARDROOM. A circular room with an equally circular grey table. Carved into the table is an off-center recessed black circle. The table is populated by executives from both Disney and Lucasfilm. Standing opposite the entrance, across the room director RIAN JOHNSON who is pacing.

RIAN: Thank you all for coming on such short notice. I realize we locked the script two weeks ago, but I want to make sure that you all have read or have heard the major plot points otherwise this meeting might spoil some things for you. Show of hands. Who isn’t up to date on the final script?

RIAN: Great. Let’s proceed.

RIAN: I woke up last night at 3 am in one of those “I have made a horrible mistake” sweats. We have a massive problem at the end of The Last Jedi. We have no villain.

EXECUTIVES: (garbled)

RIAN: I know what I said at the final pitch meeting. We had to mix things up, and we had a pave the way for the next generation of the Jedi, but at the end of this movie, there is just no one to hate. Snoke is dead, Hux is borderline comic relief, and the audience is practically rooting for Kylo – shirt on or off.

EXECUTIVES: (louder. unintelligible)

RIAN: Rey made him good. His relationship with Rey makes him human. Their Force connection shows us that Kylo’s soul is still in play and, oh yeah, you know Adam Driver seethes with charisma. He’s the most interesting character on the screen and he’s not becoming eviler, he’s becoming more neutral. Batshit crazy, but neutral.

EXECUTIVES: (muddled)

RIAN: My point is, what’s the tension in the next movie? Saving Kylo? He’s just killed his master and apparently has a thing for Rey. Building the rebellion against the First Order? The First Order gets its ass kicked twice by the last rebel ship standing. One bombs them and the other rams them. The First Order needs to learn to steer away from shit before the audience takes it seriously. Also, what resistance? There’s more porg on the Millennium Falcon than there are fighters in the resistance.

RIAN: I know I pitched the theme of the Force can be a part of anyone. We need to think about a post-Skywalker Star Wars, but as written now, we’re going to into the third movie with very little tension and no villain… and I know how to fix it.

RIAN: Rey needs to turn to the dark side. When Kylo and Ray reach out and touch hands, she turns to the dark side.

EXECUTIVES: (screaming)

RIAN: Everyone calm down. This is not a restart. All of the major plot lines remain intact. Finn’s useless Raiders of the Lost Arc-inspired trip remains the same except he sees Rey and Kylo on Snoke’s ship. Suddenly Finn is in. He’s mad! He’s relevant! Is he a Jedi? I don’t know, but let’s find out. Luke and Kylo – again, it’s unchanged. We still get the showdown at Crait and now it’s more meaningful because – just like Luke predicted – Rey is just like Kylo. Luke still projects himself because Luke is a hero and that is what heroes do.

EXECUTIVES: (slightly less screaming)

RIAN: Yes, even the escape. Chewie shows up to rescue the remaining rebels, and they escape thanks to Luke’s Kylo-delay tactics. It’s 95% the same ending except for one crucial difference. Rey can sense that they are escaping… and she lets them.

EXECUTIVES: (silence)

RIAN: Of course, she’s not going to turn. She’s a mole. She’s full-on Severus Snape and who the hell didn’t love that guy’s arc? Even better, Chewie is in on the gig, and he’s full-on Dumbledoring his way to the next rebel base.

EXECUTIVES: (continued silence)

RIAN: I don’t know. That’s Colin’s job to figure out, but we’re handing him a gift. We hand him a villain. We provide him tension. We hand him the critical question to answer, “Is Rey good or bad?” I’d watch the hell out of that movie.

EXECUTIVES: (mumbling. threatening)

RIAN: Ron Howard?

EXECUTIVES: (confirmation)

RIAN: … This is just me spitballing. I think we’ve got an incredible movie on hands… as is. Sorry for wasting your time.

January 5, 2018

Act Last, Read the Room, and Taste the Soup

The quiet is my favorite attribute of a holiday break. My various Slacks are quiet, the house is quiet, and while it takes three days of quiet, eventually my head is quiet.

Quiet creates reflection. I replay the critical parts of recent life and rather than living them, I observe them… at a distance. This often allows me to find the lessons rather than react to the situation.

This holiday break I found three lessons and they are lessons I wish I knew a long time ago:

1. Act last. In poker, a full table is ten players, and the betting starts to the left of the button which is a round plastic thing that sits in front of one player and rotates clockwise with each subsequent hand. The button, the last player to bet, is the prime position because you get to see how every other player at the table is indicating they are going to play this hand. You have the most information for which to make a betting decision.

Oddly, at work, you will find yourself in precisely the same situation. You’ll be sitting in a meeting where folks are going around the table and giving their opinion about this important topic and for a great many situations when it’s your turn to offer your opinion; the correct move is to pass.

Information builds context and context is the circumstance that forms the setting for an idea so that it can be understood. The more folks go around the table and weigh in on what they think about the idea, the more context you have, so the better you can shape your opinion before you share it.

Extroverted humans love to own the energy of a live conversation which means they’ll likely play their cards right out of the gate. Unlike poker, this is often the right move to land a new idea. It’s called “first mover advantage,” and for the human who wants to define the narrative by landing their compelling idea first, it’s solid opening play. Thing is… acting early might set tone, but it doesn’t make an idea sound. An idea doesn’t get better with agreement; it gets better with debate. It gets better when a diverse set of human have a chance to stare it and share their unique, informed perspective.

So, the question is, “When to act first or act last?” It’s a fair question which is why you need to…

2. Read the room. My opening move in any presentation is to read the room. The slippery question I am answering for myself is, “What mood is this particular set of humans in?” Impossible to answer, right? What is the aggregate happiness or sadness of a group of 500 humans? How are they feeling? And why does it matter?

The reason you care about the ambient mood of a group of humans is you have business with the folks. You have a talk to deliver; you have 1:1 to complete, or you have an urgent topic to discuss at a cross-functional meeting. Their collective mood is critical signal on your approach path for getting your work done, and the sooner you have tested the mood, the sooner you have your approach vector.

My opening moves for reading the room:

For a talk, I almost always open with an audience participation exercise. Raise your hands. How many extroverts? How many introverts? Why do care about the split of perceived personality types, what I care about is how many folks willingly raise their hand. 500 people and only a 100 raise their hands to identify as extrovert or introvert? Ok, this particular crowd has it’s guard up. No clue why, but it means they are holding me at arm’s reach so I will do extra work to connect by explaining my background and my goals for the talk to make myself familiar.

For a 1:1, I do what I wrote about here. I ask “How are you?” As I wrote, I am carefully listening to your answer:

What’s the first thing they say? Do they deflect with humor? Is it the standard off-the-cuff answer? Or is it different? How is it different? What words did they choose and how quickly are they saying them? How long did they wait to answer? Did they even answer the question? Do you understand the answer isn’t the point, either? The content is merely a delivery vehicle for the mood, and the mood sets your agenda.

Finally, for a meeting, and to make it harder, let’s say it’s a meeting I am not running, but have a role as a participant. Not being able to land the first question and set tone makes the initial read harder, but all the signal is still in the room. Who is running the meeting? How do they open it? Who perks up? Who keeps their nose buried in their phone? As topic changes, how does the demeanor of the different meeting denizens change? What is every single thing I know about that them and how might that context inform their changes of mood depending on topic?1

Reading the room is the specialty of introverts because we are comforted by the act of gathering of context. This context gives us the impression we have a map for how this particular meeting might go, but where introverts can fail is when all we do is listen, all we do is build more context, and we don’t…

3. Taste the Soup. What do we hate about micromanagers? I’ll tell you what I hate. I hate the leaders who believe that prescribing every single action without room for improvisation, iteration, or feedback is anything but demeaning and demoralizing. If I screwed up, if I failed on something critical because I failed to listen to your guidance then sure… dictator it up. Until we arrive at that failure case, I don’t need to be told what to do; I need you to taste the soup.

In your career, you’ve had a lot of soup. You’ve had tomato, chicken noodle, potato leek, and countless others. More importantly, you’ve had different variations of each soup. Big huge noodle chicken noodle. Some amazing type of cream on that tomato soup. This soup journey has taught you a lot about soup. Now, when presented with a new bowl of soup, the moment that counts is the first taste. You taste a bit and wonder, “What is going on with this soup?”

In a meeting where an individual or team is presenting a complex idea or project, my job as the leader is soup tasting. It’s sampling critical parts of the idea to get a sense of how this soup has been or will be made. Who are the critical people? What are the critical parts? Which decisions matter? I don’t know. I do believe that a pre-requisite for leadership is that you have experience. You’ve had trials which have resulted in both impressive successes and majestic failures. These aggregate lessons define your metaphoric soup tasting ability, and when your team brings you a topic to review, it is this experience you apply to ask the critical soup questions.

Leaders who default to micromanagement teach you nothing about the craft of building. Their tell-assertive style creates an unsafe environment where some of the best parts of being human, our inspiration and our creativity, cannot exist. Tasting soup, asking small, but critical questions based on legitimate experience, creates an environment of helpful and instructive curiosity. Why do you choose this design? What is this metric going to tell us? What do you think the user is thinking at this moment?

The opposite of quiet is noisy, and business is noisy. It’s full of humans acting first, ignoring the room, and tasting none of the soup… and being annoying successful with each of these acts. Like all advice you ever received, mine is situationally useful, but based on what I value as a leader.

Let others share their thoughts. You never know when a great idea will appear. Understand that as a leader, your team is going to be less likely to contradict your idea which is another good reason to act last.

Understand that everyone is busy having their life and they are often bringing that life to the conference, the 1:1, or the meeting. Their life might not always cleanly fit neatly into business and your job as a leader to read the room to understand what they need.

Demonstrate respect to the team by asking great questions. Be curious. Your experience has taught your lessons, and your questions often share lessons better than your lectures. Plus, you never know what kind of soup you’ll discover.

And have a great new year.

Exhausting right? Now you know why it takes three full days to clear my head. ↩

December 17, 2017

So

We need to talk about the end of sentences. Specifically, the end of spoken sentences. They’re a problem for me. I’m solidly in my 40s. And to this day when I finish a spoken thought, I often say “so,” and the reason is… you aren’t saying anything, yet.

So. I should explain.

To begin, self-diagnosed introvert here. No, I haven’t read Quiet because I’m living it. I’m sure there is likely a chapter in the book on the behavior I’m about to describe.

Let’s start with the fact that I’m not going to open my mouth until I’m 90% sure of the entirety of what I’m about to say. I know the beginning, middle and end of the story before I’ve said a thing. Often, I’ve also done the social math on how each person listening will react to my story. This why I am so quiet. I am testing, repeating, and refining my thoughts.

Extroverts start talking somewhere between 1% and 5% thought confidence. I know this because I’m intently listening to their narrative evolve the more than they talk… and talk… and talk. I’m jealous. They’re simultaneously both talking, absorbing the non-verbal reaction to their thoughts, and adapting their message in real time. It’s impressive social sorcery.

So. What’s the deal with “so”?

Once I’ve constructed, and AB tested my thought that I have yet to say, I’m going to start saying it, ok? Ready? 1… 2… 3… 4… go!

Right. Talking now. I’m mostly reading from my tested mental script, but you wouldn’t know this because I’m pretty okay with the talk thing. I understand how quickly I can and can not speak. Pauses are my friend. I use them to check my speed, read the room, and measure the reaction to the message. The problem is, we’re getting to the end of the narrative, and it’s clear that no one is going jump in when I’m done. How do I know this?

Most humans are not pure introvert or extrovert. We’re all a blend. This is why I can successfully stand up in front of a room full of humans and deliver a talk. I can read the room and understand whether the message resonates. Yes, my preference would be hiding in my cave, but I do receive an odd sense of extroverted satisfaction talking to hundreds of humans.

So. This is different.

I’m almost at the end of my thought and interest in what I just said is low. Either you weren’t listening, what I said didn’t make sense, or you just don’t care about my topic. For majority introvert, this is a terrifying moment that extroverts don’t understand. The shame of silence.

So.

So, I say so.

Eddie and Cruisers is one of my mother’s favorite movies and my favorite scene from the movie is when one of the characters describes a French term: cesura. It’s a break in the verse where a phrase ends, and the following phrase begins. The pause may vary between the slightest perception of silence all the way up to a full pause1.

A good conversation contains moments of silences. Moments of consideration, but that is not what is going to happen as I finish my thought. My terror is based on my weak extrovert skills alerting me that pause that is about to arrive is not healthy. No one wishes to continue my thought. It will be quiet, and I know that good conversation is music.

So.

So, I say so.

In music, it’s called a breath. A better description. ↩

November 26, 2017

A Meritocracy is a Trailing Indicator

When you are asked as a manager “What do I need to get to the next level?” I suggest the quality and completeness of your answer is directly correlated to your effectiveness as a leader. Let’s start with the worst answer, “We’re a meritocracy where the best idea wins.”

This is a bullshit cop-out answer. First off, being a meritocracy is a philosophy, it’s not a strategy. Using this as an answer to the growth question is akin to saying, “We give out gold medals when you win, so when you start getting gold medals, we’ll all know you’re winning.”

A meritocracy, if achievable, would be a trailing indicator. It would be a sign that long ago, your leadership team successfully created a culture where the humans were recognized because of their ability. It reads like a noble dream worth striving for, but it is poor career growth advice.

Here’s a better answer.

Two Paths

There are two career paths1 in your organization. One which describes the growth of the individuals and one that illustrates the growth of the managers. These paths are readily visible public artifacts written by those who do the work. This means engineers write the paths for engineers, marketing writes marketing’s, and so on.

The contents of these artifacts need to reflect your values, culture, and language, but I humbly suggest they contain the following information:

A series of levels and titles. A level is a generic number to differentiate each level like Engineer 1, Engineer 2, etc. A title is a more descriptive version of the level such as Associate Engineer, Engineer, Senior Engineer, and so forth2.

A brief description of the overall expectation of the level. For a senior engineer title, this could be: “Owns well-defined projects from beginning to end.”

A list of competences that are required attributes for all versions of this role. These are the measures for success for each level. An example competency might be “Technical Ability” and might the following definition: “Technical: Designing, scoping and building features and systems. Helping others to make technical decisions.”

Finally, you need to define the per level expectation of the competencies that demonstrates the competency. An Associates job relative to the technical facet (“Implements and maintains the product or system features to solve scoped problems. Asks for guidance when necessary.”) is much different than a Senior engineer (“Independently scopes flexible technical solutions. Anticipates technical uncertainties. Trusted to design and implement team-level technical solutions. Guides team to improve code structure and maintainability. Garners resources required to complete their work.”)

This suggested list is not definitive. You could easily add sphere of influence, ideal years of experience, or comparable levels outside of your company to this artifact. And then do the whole thing over again for your manager career path.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by the enormity of this task, you are in good company. There are existing career paths on the internet that can serve as good starting points, but I strongly encourage your team to write their own because your culture is unique. The competencies you need are a function of the values of your particular collection of builders.

Two Equal Paths

As a human who was screwed up the design and landing of career paths in every possible way, I have hard-earned advice on common pitfalls of landing these artifacts. My first piece of advice is making it clear with your actions that these two paths – management and individual – are equal. I’ll explain this concept by describing how to not land your career paths.

The need for a career path begins when there are enough engineers to require a rubric for career growth. A well-intentioned group of individuals defines this path. Great! You have a career path. Who decides who goes where on this newly defined path? Who is Senior? Who is Senior staff? Usually some form of a manager. It is at this moment when individual contributors not familiar with the ways of managers realize that these folks have a heretofore unknown influence on their careers. They probably already suspected something was up because these people were sitting in meetings… all the time.

When it becomes apparent these managers have special powers, a subset of individual contributors quickly become interested in management. The problem is this is often a career path that doesn’t often exist yet usually because everyone one was too busy working to define the individual contributor career path.

Here’s the screw-up. You just finished defining the individual contributor career path, and suddenly everyone is interested in a career path that has yet to be written. What’s up? The answer is: your individual career path has not made it clear that individuals have equal opportunities to lead.

There are many good reasons for an engineer to want to move into management, but if their only reason is the perception that management is they best place to grow as a leader, then you’ve started down a path where the perception is leadership is not the job of individuals. This is disaster.

The Growth Tax

Artifacts like a career path show up to document the culture, to define rubrics, and to help inform a process to allow informed decisions to be made to help the team scale. They exist to provide accessible definition, but how they are applied is what the team is truly watching. In the example above where managers are choosing levels for a newly defined career path, the team cares equally about their level and who is choosing it.

During a period of rapid growth with only organic role definition, everyone is wondering where they stand because everything is changing all the time. Suddenly, these managers appear who have the power to determine role and individuals ask themselves, “What other powers are they going to grant themselves? And how do I get in on that situation?”

Yes, you already wrote a career path for individuals. You defined a clear set of competencies of what makes a successful growing individual, but you forgot to make it clear that leadership comes from everywhere. If an individual doesn’t believe that they have an equal chance to lead as a manager, then those who desire to lead will attempt to get on the manager path.

This isn’t a horrible outcome because you do need to build and hire capable managers, but it’s a disaster because you are signaling to your team that it’s the managers who are calling the shots.

The growth tax is a perceived productivity penalty that you incur as a function of the size of your team. How long does it take make a hard decision? How does a person find out a critical piece of information? Who owns what? The cost to answer each of these (and far more) questions slightly increases as each new human arrives.

These small communication taxes pale in comparison to the taxes levied by defining cultural norms. In a company where it is believed that the managers are the only leaders, you create hierarchy. We must go a higher power to ask for permission. Hierarchy creates silos. We own this, and they own that. Silos often create politics. Our mission is the only mission. Their mission is lesser.

Again, a disaster.

Leadership Comes From Everywhere

A meritocracy is a philosophy that states that power should be vested in individuals almost exclusively based on ability and talent. Advancing in this system is based on performance measured through examination and/or demonstrated achievement. As a leader and as an engineer, the concept of a meritocracy is appealing3. I want my teams as flat as possible and full of empowered individuals and any action that re-enforces the perspective that “managers have all the power” is sub-optimal.

Are managers required to scale a large group of humans? My vote is yes. You might disagree, but I think a set of humans responsible for the people, process, and the product are an essential scaling function. One reason you might disagree is that you’ve seen managers who’ve done the job poorly. That sucks. There are good managers out there, and they are the ones that understand their job is their team because without their team they have exactly no job.

The definition of individual contributor leadership starts with defining a leadership competency in your career path, but you need to spend an equal amount of time defining clear places for individuals to lead. Here are two places you can invest:

Technical Lead What does technical lead mean for your company? Is it a throwaway title that managers use to placate cranky engineers? That’s a missed opportunity to define credible contributor leadership. Here’s a starting definition: “You are the owner of this code/project/technology and this means you are the final decision maker when it comes to this area.”

With this definition in hand, you make a list of the all the technical areas that need technical leadership and make it publicly available. These are the areas we are responsible for and these are the technical leads. Ask them first.

Details about defining this role are both numerous and potentially politically hazardous. For example, how long can someone be a technical lead? What happens when they leave? And, finally, the contentious, “Who chooses technical leads?” Good luck.

Technical Lead Manager Another leadership variant. This role is a hybrid designed to give aspiring managers a transparent and fair view of people management.

The details: Technical Lead Managers continue to code a minimum of 50% of their time, but they also have direct reports. What’s the catch? Cap their direct reports at three. This constraint is intended to give new managers exposure to all the aspects of people leadership (Reviews, promotions, 1:1s, there’s a book) while giving them reasonable time to be hands-on engineers. Why three directs? Why 50%? Your ratios may vary, but what we’re optimizing for is a higher probability that they can do both jobs well instead of both poorly.

Like Technical Leads, the devil is in the operational details, but one cultural aspect I like to reenforce is the removal of any stigma when a Technical Leader Managers chooses to leave the role. After four months in the role when they approach me and suggest, “I don’t think I am built for the people thing.” I ask clarifying questions, we discuss, and once we’re both satisfied with the answers, we celebrate because it is likely we just avoided inflicting another crap manager on the world.

A Trailing Indicator

My final piece of advice is the most complex and incomplete. As I wrote above, the manner that you define leadership is as important as how it is perceived you are applying it. A thoughtfully constructed promotion process provides a means of consistently and fairly demonstrating to the entire team how you value leadership.

The topic of building a promotion process deserves an entire article. I’ll write it. I’m sorry to leave you hanging, but if you intend to follow the advice in this piece, you’re on the right track. You have career growth paths for both individuals contributors and managers. You’ve also perhaps defined additional non-managerial roles that give individuals opportunities to lead.

Your future promotion process benefits from work above because it gives both managers and individuals a standard frame of reference to have career and promotion discussions not just at promotion time, but all the time. Your future promotion process also needs to answer the question, “Are you consistently and fairly promoting both individual contributors and managers who are demonstrating leadership?”

There is more work you need to do. You need to train your managers to have career conversations all year long, you need to build an employee-friendly internal transfer policy that allows individuals to freely move about your company, you need to invest in teaching the entire company to give feedback, and there’s much much more because building a growth-mind company isn’t defined by a word, it’s defined by hard work.

Folks like using the word ladder here, but I prefer the term path. A ladder is a thing you must climb upwards. A path is a journey. ↩

Yeah, I said that titles are toxic. In particular, I said “The main problem with systems of titles is that people are erratic, chaotic messes who learn at different paces and in different ways.” This is true. It’s also true that I have not yet thought of a better mechanism for defining career progression. ↩

True story. While the concept of a meritocracy has been around, it was until 1958 that humans called it a meritocracy. It’s a term coined by Michael Young, a British sociologist, who was satirizing the British education system. Young was “disappointed” that it was adopted into the English language with none of the negative connotations. ↩

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers