Marie Chow's Blog

October 22, 2014

Switching Genres, and Taking Breaks

Much of the “literary” writing was stalling and in various stages of iteration death, so I thought it might be a good idea to switch genres.

For the past few months I’ve been working on, finishing, and rewriting a historical romance novel. I found it fun… uplifting. My characters were, for once, both likable and happy. The flow of the story was predictable, but soothing. There was something almost relaxing about playing with slightly-more-stock characters who were capable of laughing at themselves, and perhaps, their genre.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I more or less grew up on romance novels, and just as my grandmother learned English from watching General Hospital, All My Children and One Life to Live, I learned about everything from cucumber sandwiches to waltzing and chivalry from Harlequin, Silhouette and Avon. So when I insinuate that there is a certain amount of rote in some of these novels it’s not so much complaint as… willing compliance.

There’s a reason that romance sells so well. And I think there’s a reason I had so much fun switching genres.

Writing romance wasn’t quite as relaxing as reading it, but it was surprising close. Still work, but kind of like the project you take on while on vacation…

The problem is that now, I’m finding it hard to switch back. So I guess the year off is still going, but kind of pausing and unpausing while I have a writing identity crisis.

June 23, 2014

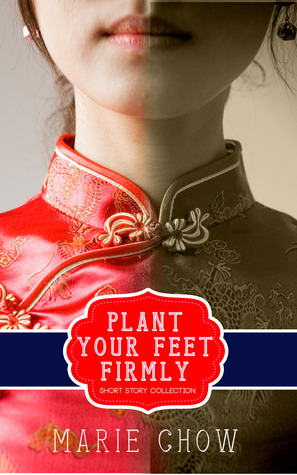

Plant Your Feet Firmly

New book of seven short stories is out on kindle and in paperback. There’s also currently a goodreads giveaway going on for the paperback version.

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Plant Your Feet Firmly

by Marie Chow

Giveaway ends July 01, 2014.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

June 2, 2014

And on that Farm there were some Robots…

My son is about to turn three, and as such, he has many of the normal three-year-old interests, of which dinosaurs, trains and (most of the) Avengers reign supreme. That’s why it was more cute than surprising when he learned how to sing “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” and the first livestock he listed included T. rex, Iron Man and later, when he was able to pronounce them correctly, dinosaurs like stegosaurus and triceratops.

What’s been a far more interesting phenomenon is that now that he goes to “preschool” (really a glorified term for daycare at his age), he’s now learned the “correct” animals to list. He sings about cows and pigs and makes all of the appropriate noises, and most distressingly, when my husband or I offer the idea of an Iron Man being at Old MacDonald’s farm, he’s quick to correct us.

(As an aside, I’m happy to report that he hasn’t left these creatures/characters homeless. He won’t just tell us that they don’t live on the farm, he’s imagined newer, perhaps better places that they do live. Iron Man resides in the sky, as do apparently, all robots. Dinosaurs live in our home, his room, etc.)

Still, I don’t know how I feel about this.

As a parent, I recognize that there are some social norms that he has to learn, many of which I won’t be the best possible teacher for. As a former teacher, I believe in the necessity of norms and rules and learning how to socialize. For example, my toddler has a not-so-great habit of going up to random people and roaring at them. Daycare/preschool has been a great place for him to start to truly understand that roaring is not necessarily the best way to make friends and/or to play. He’s far better about saying “I’m sorry” when there are little mistakes he makes (or when he’s just been careless and bumps into someone, etc). He also gets that “school” is a place for “learning” and has a better grasp on the idea that his parents “work” — really the list of small things that daycare/preschool has taught him, from songs, to words, to norms, is endless.

Yet this one thing — the fact that robots and Iron Man, that dinosaurs and dragons don’t get to live on Old MacDonald’s farm any more — bothers me more than I can adequately express. What else is he learning that’s shrinking the scope of his creative and imaginative boundaries? Just as importantly, are there things he now won’t he be able to unlearn? (For, despite the fact that my husband and I have been very, very encouraging about expressing our belief that yes, Iron Man can live on a farm, my son’s been adamant, “Iron Man does NOT live on the farm” has become his new mantra.)

It’s the first, but I’m certain not the last, time I’ve had to deal with this idea that formal schooling has both benefits and associated costs, and it’s been particular fascinating in terms of how normals and learning are balanced against creativity and individuality.

April 29, 2014

Blog Tours, Promotions and Guest Posts

I’ve tired out a couple different blog tours these past couple of months (to different/mixed results).

I definitely learned a lot (about the process, work involved, expectations, expected returns, etc), and also, it was a good opportunity to write guest posts… where someone else picks the topic.

My favorite was one I wrote about the Pros and Cons of Being an Indie Author.

April 27, 2014

Discover Authors: Unwell Giveaway

One of the wonderful things I stumbled upon during my rapid/steep/slightly painful book-marketing-self-education these past few months is that there are some nice sites and blogs that are pretty much devoted to helping indie authors publicize… for free!

Over the next few days, I’ll be part of the Discover Authors bloghop, and to that end, I’ll be profiling Unwell, which is also currently free on amazon.com (Kindle version only, through Tuesday, 4/28/2014).

The short-and-simple version of Unwell? It’s a women’s/contemporary/Asian American story:

Written as a letter to her unborn child, and with a poignant lack of emotion, a young mother shares her life story. As the child of Asian parents who moved to America early in her life, the mother shares how her life disintegrated after her parents’ divorce. From upper middle class suburban to sharing her mean aunt’s house to a one bedroom apartment in a shabby neighborhood, this mother endures the indignity that comes with the change of status. From her father’s absence to her mother becoming a married man’s mistress, her story reads like a tragic Victorian novel set in the 21st century, but that’s where the similarity ends—she is definitely not a shy country miss and she certainly did not take the easy way out.

Interested? Download it for free (from now until April 29th) here.

The tour this go-around has everything from kid’s books to sci-fi, since I’m a reader and writer who enjoys multiple genres, it’s been a great experience!

If you’ve already bought Unwell, it might still be nice to check out their site and check out other free books they’re hosting. If you’d like to hear more about my short stories (one collection out, one pending final cover art) or kid’s books (one bilingual story out, three pending illustrations, please continue to check-in at mariechow.com periodically

April 23, 2014

Help me figure out what’s wrong with this cover!!!

So, I’ve been working with a new graphic designer for my new book covers, and she did a wonderful job on the first one (a mini-collection of three short stories):

But… the larger collection (a set of five short stories) just isn’t coming together. We started with a great (I think) concept, but no matter how we tweak it, it just doesn’t seem to be working.

But… the larger collection (a set of five short stories) just isn’t coming together. We started with a great (I think) concept, but no matter how we tweak it, it just doesn’t seem to be working.

I’m officially going against the not-asking-for-feedback post from a week ago, and am now actively soliciting opinions. The stories are done, I just need this cover to work. Here are a few samples we’ve been working off of.

Here’s the latest iteration (where I asked her to try different borders for the pictures):

This is with a slightly different background. I think I like the crazy hair with the green background, but I’m not positive!

This is more or less where we started (I had asked her to take out the older/white hair, though now I’m having second thoughts. I also disliked that the nose was all from one lady, and has asked that to be changed.):

And here’s how I’m going to justify asking for feedback: it’s not feedback on my writing, and it’s not writing-in-progress. It’s just… a cover that I really want to resonate. I’m pretty artistically untalented when it comes to all-things-visual, so comments and feedback will be greatly appreciated.

April 10, 2014

10 Reasons I’ve Stopped Reading Reviews and Soliciting Opinions

Even in my most rebellious periods, I have always been one of those people who cared (far too much) about other people’s opinions.

When I was a teacher, I often (when I wasn’t totally burnt out by the end of the year) passed out end-of-the-year surveys. These were anonymous, and would remain sealed until after grades had been submitted. (By the end of the year, I could usually recognize my students via their handwriting, and I didn’t want any part of the grade to be subjective.) I would sometimes spend all summer obsessing over the bad ones (forget the actual good to bad ratios). I still have, in a folder somewhere, a bad review from the first year I taught. I still agonize about what I could have done differently to reach that student. (It was anonymous, but again, with handwriting, etc. I knew who wrote it.)

I also obsessively checked sites like ratemyteachers.com — and by obsessively, I mean just that. It was a problem. (Who am I kidding, on bad days, even though I don’t teach any more, it still is a problem.) I had to ground myself from the site. And then, I had to bargain with myself and have a daily and/or weekly allotment for how often I was allowed to check the site.

Now that I’m a writer, with books that can be reviewed?

Unadulterated torture.

Catastrophe of epic proportions.

Which is why I’ve decided to stop reading reviews (at least for now). I’ve decided to stop soliciting opinions on things that are in progress.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m still going to advertise, and market. I’m going to give books away and ask for reviews.

I’m just not going to read those reviews on a regular basis. I’m not going sit in front of my computer screen constantly refreshing the screen to see whether there are newer, better reviews up.

Here’s why:

1. I appreciate, yet ultimately second-guess 5-star reviews written by people who know me. I am so completely grateful when a friend reviews a book of mine. I need, need, need reviews. In the slush pile that is the indie self-publishing world, I desperately need those votes of confidence to gain visibility and hopefully, eventually, momentum. But, beyond the quantitative boost it gives my book on say, amazon.com, I don’t derive long-term pleasure from a friend’s 5-star review. I always think: well, they’re my friend. They like me. They probably see the book as an extension of me. They’ve just given me a 5-star review on our friendship. Who knows what they really think about the book?

2. I obsess, and am completely illogical about 4-star reviews given by people who know me.

3. I worry that strangers who give 5-star reviews are just really, really nice people. Even when total strangers have written very nice or even borderline glowing reviews, I still find a way to second-guess: Perhaps they’re just nice people. Perhaps they always write nice reviews. (I then obsessively check their past reviews to see how many 1-star reviews they’ve given, and so on).

4. Mediocre reviews don’t always have a rhyme or reason (which of course, causes me to lose sleep trying to invent a reason) I have a 3-star review on Goodreads, my first 3-star review. With no commentary. Another blogger, who actually contacted me about doing a giveaway and a guest post, said that it “wasn’t like the best book ever” but that she “enjoyed” it. Which a) totally feels like the literary equivalent of: You’re nice, but I’m just not that into you and b) made me run around in circles worrying about why she wanted me to do a guest post. If I’m going to obsess this much over the middling reviews, I shudder to think what will happen the first time I get a 2- or even 1-star review. If I stay in the game long enough, it’s only a matter of time…

5. No review is going to make me change the ending to a particular story or even… my writing. All of my writing is an extension of me, and reflects conscious choices that I’ve lots of time (frequently too much) deliberating on. After I published Unwell, two people asked about its ending and suggested they really wanted it to be… different. Yet (without giving it away here) the ending to that novel was one of the things that felt the most (sorry, cliche coming) “right.” I would never change it or the style in which it was written.

6. None of the reviews will make me a better writer… but they might distract me, and thus make me a worse one. While there was a reviewer who very, very helpfully pointed out a couple of typos I still had (embarrassment, apologies, gratitude, etc), most of the reviews do nothing but distract me. Someone genuinely suggested a sequel to my debut novel, which isn’t something I could even begin to imagine (though I of course wasted several days half-wondering about it). While good reviews might (if I get over my other issues) make me happy, I don’t foresee a result where they help make me a better writer… and since my goal is to write.

7. Getting feedback as I write distracts and makes me second-guess myself in totally unproductive ways. (And I say that as someone who believes that there is such a thing as a “good” distraction.) Back when I was a hermit-writer (meaning one of those writers who never, ever told people I wrote), I could love, hate, edit-to-death, abandon or revise any story I wanted. Now that I’ve started to tell people about the writing and gather feedback on it, there have been fun, new ways in which other people’s opinions have become crippling.

When my husband says something shows promise, I translate that to: It’s not there yet.

When a friend says, I’ve done better, it becomes: I loved blah and blah, but this one is just bleh. I hear, and process: Charlie-Brown-wah-woh-wah, this is just BLEH! (emphasis intended).

Such criticism is meant to be helpful or even encouraging, but (at least for me) it’s not.

8. Even when feedback is useful, it’s sometimes… not useful. One of the novels I’ve been writing has already had several different beginnings. This is very, very common for me with both short stories and longer works. At once point, I asked just two people to look at the various endings. They both agreed on which beginning was better.

The problem was… even though they agreed, deep down. I didn’t. I just didn’t trust my gut instinct.

I wasted weeks trying to cram my story into the beginning both of my early-readers liked, only to finally realize that it just wasn’t going to work, and more than that, I realized that the beginning neither of them voted for was more on point with the rest of the novel, and what I really needed was to re-think, re-outline, and take a step back.

9. Everyone has a different opinion, and writing by committee (or editing by committee) is a terrible, terrible idea. You could think I would have learned this back when I was in a lab, working on research papers, but nope. I had to re-learn it here. I’ve just now realized that, now that I’m telling people I write and soliciting feedback, soliciting someone’s opinions on something as personal as writing? It’s a bit like herding caffeinated sheep with one hand and a rusty bugle. For example, on the rhyming book I recently finished? Here is some of the commentary I got:

Person A: oh, this is a half-rhyme. You should totally make it a real rhyme. It should be really easy. Thighs rhymes with eyes. Try that.

Person B: are you crazy? Who would put the word “thighs” in a children’s book? Who care’s that it’s a half rhyme?

Person C: What’s a half rhyme? Am I too stupid to be commenting on this?

Person D: Hrm, you changed something. What did you change? I liked it better before.

Person E: Wow. This is so much better now that you’ve changed that.

So, either I need to artificially assign Person C’s opinion as being fundamentally better than Person B’s, or I just accept that no matter what I change, or don’t change, someone’s going to think it should or could, have been better.

10. Reading reviews, soliciting feedback, all of it is non-writing time. With two children, a husband, tutoring, as well as some ever-finishing-side-gigs, I only get so many hours that are possible writing hours. Like Cinderella going to the ball, each of my writing hours feels like a precious, hard-won escape that can only be had after I’ve finished all of my other chores. Every minute I spend obsessively refreshing the computer screen to see if I have another review, another rating, or even if another friend has commented on my recent story… all of it detracts from the already-too-scarce writing time.

Though I know it feeds my compulsive-tendencies, and though it is at least somewhat satisfying and feels almost-like-progress whenever I get a new review, it isn’t ultimately necessary.

If I never read another review, I could, and probably would, still write.

If I never solicited another friend’s opinion or commentary, I could, and would, still write.

I don’t need to read reviews.

Unless I’m in the final editing stages where I need help catching typos or having egregious plot holes pointed out, I don’t need ongoing feedback about a still-amorphous and developing project.

That’s part of the benefit of being indie. I don’t have fans to disappoint, just a ladder I’m building, one rung at a time.

And so, like any addict, I’m making a promise to stop a pattern I’ve identified as counterproductive and unhealthy. Despite the fact that even whilst typing this I’ve been fighting the urge to hit “refresh” one last time on the other screen…

I’m just not going to do it.

10 Reasons I’m No Longer Reading Reviews or Soliciting Opinions on Works-in-Progress

Even in my most rebellious periods, I have always been one of those people who cared (far too much) about other people’s opinions.

When I was a teacher, I often (when I wasn’t totally burnt out by the end of the year) passed out end-of-the-year surveys. These were anonymous, and would remain sealed until after grades had been submitted. (By the end of the year, I could usually recognize my students via their handwriting, and I didn’t want any part of the grade to be subjective.) I would sometimes spend all summer obsessing over the bad ones (forget the actual good to bad ratios). I still have, in a folder somewhere, a bad review from the first year I taught. I still agonize about what I could have done differently to reach that student. (It was anonymous, but again, with handwriting, etc. I knew who wrote it.)

I also obsessively checked sites like ratemyteachers.com — and by obsessively, I mean just that. It was a problem. (Who am I kidding, on bad days, even though I don’t teach any more, it still is a problem.) I had to ground myself from the site. And then, I had to bargain with myself and have a daily and/or weekly allotment for how often I was allowed to check the site.

Now that I’m a writer, with books that can be reviewed?

Unadulterated torture.

Catastrophe of epic proportions.

Which is why I’ve decided to stop reading reviews (at least for now). I’ve decided to stop soliciting opinions on things that are in progress.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m still going to advertise, and market. I’m going to give books away and ask for reviews.

I’m just not going to read those reviews on a regular basis. I’m not going sit in front of my computer screen constantly refreshing the screen to see whether there are newer, better reviews up.

Here’s why:

1. I appreciate, yet ultimately second-guess 5-star reviews written by people who know me. I am so completely grateful when a friend reviews a book of mine. I need, need, need reviews. In the slush pile that is the indie self-publishing world, I desperately need those votes of confidence to gain visibility and hopefully, eventually, momentum. But, beyond the quantitative boost it gives my book on say, amazon.com, I don’t derive long-term pleasure from a friend’s 5-star review. I always think: well, they’re my friend. They like me. They probably see the book as an extension of me. They’ve just given me a 5-star review on our friendship. Who knows what they really think about the book?

2. I obsess, and am completely illogical about 4-star reviews given by people who know me.

3. I worry that strangers who give 5-star reviews are just really, really nice people. Even when total strangers have written very nice or even borderline glowing reviews, I still find a way to second-guess: Perhaps they’re just nice people. Perhaps they always write nice reviews. (I then obsessively check their past reviews to see how many 1-star reviews they’ve given, and so on).

4. Mediocre reviews don’t always have a rhyme or reason (which of course, causes me to lose sleep trying to invent a reason) I have a 3-star review on Goodreads, my first 3-star review. With no commentary. Another blogger, who actually contacted me about doing a giveaway and a guest post, said that it “wasn’t like the best book ever” but that she “enjoyed” it. Which a) totally feels like the literary equivalent of: You’re nice, but I’m just not that into you and b) made me run around in circles worrying about why she wanted me to do a guest post. If I’m going to obsess this much over the middling reviews, I shudder to think what will happen the first time I get a 2- or even 1-star review. If I stay in the game long enough, it’s only a matter of time…

5. No review is going to make me change the ending to a particular story or even… my writing. All of my writing is an extension of me, and reflects conscious choices that I’ve lots of time (frequently too much) deliberating on. After I published Unwell, two people asked about its ending and suggested they really wanted it to be… different. Yet (without giving it away here) the ending to that novel was one of the things that felt the most (sorry, cliche coming) “right.” I would never change it or the style in which it was written.

6. None of the reviews will make me a better writer.. but they might distract me, and thus make me a worse one. While there was a reviewer who very, very helpfully pointed out a couple of typos I still had (embarrassment, apologies, gratitude, etc), most of the reviews do nothing but distract me. Someone genuinely suggested a sequel to my debut novel, which isn’t something I could even begin to imagine (though I of course wasted several days half-wondering about it). While good reviews might (if I get over my other issues) make me happy, I don’t foresee a result where they help make me a better writer… and since my goal is to write.

7. Getting feedback as I write distracts and makes me second-guess myself in totally unproductive ways. (And I say that as someone who believes that there is such a thing as a “good” distraction.) Back when I was a hermit-writer (meaning one of those writers who never, ever told people I wrote), I could love, hate, edit-to-death, abandon or revise any story I wanted. Now that I’ve started to tell people about the writing and gather feedback on it, there have been fun, new ways in which other people’s opinions have become crippling.

When my husband says something shows promise, I translate that to: It’s not there yet.

When a friend says, I’ve done better, it becomes: I loved blah and blah, but this one is just bleh. I hear, and process: Charlie-Brown-wah-woh-wah, this is just BLEH! (emphasis intended).

Such criticism is meant to be helpful or even encouraging, but (at least for me) it’s not.

8. Even when feedback is useful, it’s sometimes… not useful. One of the novels I’ve been writing has already had several different beginnings. This is very, very common for me with both short stories and longer works. At once point, I asked just two people to look at the various endings. They both agreed on which beginning was better.

The problem was… even though they agreed, deep down. I didn’t. I just didn’t trust my gut instinct.

I wasted weeks trying to cram my story into the beginning both of my early-readers liked, only to finally realize that it just wasn’t going to work, and more than that, I realized that the beginning neither of them voted for was more on point with the rest of the novel, and what I really needed was to re-think, re-outline, and take a step back.

9. Everyone has a different opinion, and writing by committee (or editing by committee) is a terrible, terrible idea. You could think I would have learned this back when I was in a lab, working on research papers, but nope. I had to re-learn it here. I’ve just now realized that, now that I’m telling people I write and soliciting feedback, soliciting someone’s opinions on something as personal as writing? It’s a bit like herding caffeinated sheep with one hand and a rusty bugle. For example, on the rhyming book I recently finished? Here is some of the commentary I got:

Person A: oh, this is a half-rhyme. You should totally make it a real rhyme. It should be really easy. Thighs rhymes with eyes. Try that.

Person B: are you crazy? Who would put the word “thighs” in a children’s book? Who care’s that it’s a half rhyme?

Person C: What’s a half rhyme? Am I too stupid to be commenting on this?

Person D: Hrm, you changed something. What did you change? I liked it better before.

Person E: Wow. This is so much better now that you’ve changed that.

So, either I need to artificially assign Person C’s opinion as being fundamentally better than Person B’s… I can just know that no matter what I change, or don’t change, someone’s going to think it should or could, have been better.

10. Reading reviews, soliciting feedback, all of it is non-writing time. With two children, a husband, tutoring, as well as some ever-finishing-side-gigs, I only get so many hours that are possible writing hours. Like Cinderella going to the ball, each of my writing hours feels like a precious, hard-won escape that can only be had after I’ve finished all of my other chores. Every minute I spend obsessively refreshing the computer screen to see if I have another review, another rating, or even if another friend has commented on my recent story… all of it detracts from the already-too-scarce writing time.

Though I know it feeds my compulsive-tendencies, and though it is at least somewhat satisfying and feels almost-like-progress whenever I get a new review, it isn’t ultimately necessary.

If I never read another review, I could, and probably would, still write.

If I never solicited another friend’s opinion or commentary, I could, and would, still write.

I don’t need to read reviews.

Unless I’m in the final editing stages where I need help catching typos or having egregious plot holes pointed out, I don’t need ongoing feedback about a still-amorphous and developing project.

That’s part of the benefit of being indie. I don’t have fans to disappoint, just a ladder I’m building, one rung at a time.

And so, like any addict. I’m making a promise to stop a pattern I’ve identified as counterproductive and unhealthy. Despite the fact that even whilst typing this I’ve been fighting the urge to hit “refresh” one last time on the other screen…

I’m just not going to do it.

March 28, 2014

Goodreads Giveaway!

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget { color: #555; font-family: georgia, serif; font-weight: normal; text-align: left; font-size: 14px;

font-style: normal; background: white; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget img { padding: 0 !important; margin: 0 !important; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a { padding: 0 !important; margin: 0; color: #660; text-decoration: none; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a:visted { color: #660; text-decoration: none; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a:hover { color: #660; text-decoration: underline !important; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget p { margin: 0 0 .5em !important; padding: 0; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink { display: block; width: 150px; margin: 10px auto 0 !important; padding: 0px 5px !important;

text-align: center; line-height: 1.8em; color: #222; font-size: 14px; font-weight: bold;

border: 1px solid #6A6454; border-radius: 5px; font-family:arial,verdana,helvetica,sans-serif;

background-image:url(https://www.goodreads.com/images/layo... background-repeat: repeat-x; background-color:#BBB596;

outline: 0; white-space: nowrap;

}

.goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink:hover { background-image:url(https://www.goodreads.com/images/layo...

color: black; text-decoration: none; cursor: pointer;

}

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Unwell

by Marie Chow

Giveaway ends March 31, 2014.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

March 26, 2014

Excerpt from Unwell

The following is a three chapter excerpt from my debut novel, Unwell.

Part I

1

I won’t lie to you. Since we’ll have nothing else together—no physical contact, no hugs, no kisses or shared memories—the least I can give you is truth.

No, I won’t be telling you the whole truth. By the time you read this, you’ll understand that there’s no such thing. Everything pure is eventually tarnished, people are ruined, and memory is, by definition, incomplete.

I’m sorry.

That came out quite a bit harsher than I intended. All I meant to say is this: I’ll give you whatever truth I can, to the best of my ability.

I’ll start with a confession: I didn’t enter the hospital to get better. Your father probably told you I had a near miss when I was thirty weeks pregnant, depression, a cry for help, blah, blah. I have no right to interfere with his version of reality, but he doesn’t know the whole story.

If you’re interested, that’s what this is.

So.

I wasn’t trying to kill myself. I don’t think I was trying to kill you — though if I’m completely truthful, that last part is a bit muddled.

What I wanted to do was escape: your father, my marriage, my life.

The idea of motherhood.

You.

2

I took a creative writing class, once, because MIT required a certain number of humanities—part of an effort to make their graduates appear well rounded.

There you have it, one of the crowning achievements of my life, and I revealed it as though it were part of something else. As if it was the writing class, not my alma mater, that mattered.

That’s not exactly a lie, but it’s not exactly truthful either. If I were to tell you as complete of a truth as I could, I would say that MIT was (hopefully still is) one of the best schools in the nation, that it was a big deal that I was accepted, and that it was almost always something I worked into conversations.

Stupid to let a degree from over a decade ago define me, but it’s the truth. I never wore my brass rat (our official class ring, which, as a member of our student council, I helped design) because that would have been too obvious. In fact, I always told people it was sad to see so many former classmates still wearing their brass rats, as if they were trying to relive the glory days. (“Brass rats?” people would ask. “Oh, I went to MIT and that’s what we called our class ring,” I would scrunch my nose and explain, as though I hadn’t prompted them into the conversation.)

Anyhow, I peaked early, and getting in was the highlight of my academic career. My grades were shitty and I worked as a glorified technician for years, begging to get on papers as the third or fourth author time and again, before a school like UCLA would accept me, but that’s another story.

So.

This writing class I took, at MIT.

I waited until the beginning of my junior year, and in-between 10.301 (fluid mechanics) and 10.213 (chemical and biological engineering thermodynamics), I registered for 21W.730 (Expository Writing: The Creative Spark). That’s one of the egotistical idiosyncrasies about MIT, every course is a number; so you never say you’re majoring in chemical engineering, you say you’re course 10. The humanities weren’t really large enough to have their own numbers, and so they settled for a number and a letter: 21A for Anthropology, 21F for Foreign Languages, 21H for History, and so on.

The reason I bring up the writing class is because Guy, my 21W.730 professor, would probably have an apoplexy if he ever read any of this. Guy was a writer, a musician, and a pothead who had somehow drifted into teaching creative writing during his latter years. His debut collection of short stories had been a Pulitzer finalist. In the decades that followed, he would constantly tell people he was working on a novel, and that he was this close to finishing it…

As far as I know, it’s still not done.

Instead, Guy drank, got high, and was married and divorced three times (this, despite the fact that almost all of his short stories featured the recurring theme of closeted homosexuality—makes you wonder whether any of his ex-wives were literate).

Anyhow, he would show up for our seminar-like courses, clearly hung-over or high, with his orange tinted sunglasses daring you to question his lucidity. He’d slouch in his chair, bored with us and our pedantic stories, and then suddenly would decide to contribute, to insert some morsel of genius, a flash of insight the rest of us missed, before slouching again, his paycheck for the day earned, his reputation reestablished.

Of course we tried desperately to arouse his interest.

We refrained from straying into genre (a lesser plane of existence in his worldview and quite unfortunate considering where he was teaching). We infused as much originality into stories that were essentially barely revisionist versions of childhood traumas and imaginary discretions as we could.

But ultimately, we were a fairly boring group – many of us were Chinese and spent too much time trying to explain in our stories how Chinese from Taiwan was different from Chinese from China, Chinese from Hong Kong, or worse, being an ABC (American Born Chinese). Our narratives described the sacrifices our parents made, the feng shui used to decorate our houses, mahjong, red envelopes and, of course, food: lion’s head meatballs, sticky rice in bamboo leaves, ten seasons of vegetables, flavors of the east stir fried two ways, things we only ate during the holidays and barely understood even then.

Our Indian counterparts were no better, submitting prose about Bengali versus Hindi, Tamil versus Assamese, and again with the food: tandoori, naan, and ghee (which I found out later, much to my disappointment, is just a type of butter).

Our American peers wrote arguably the most personal stories: the culture shock of college, the loss of virginity.

Still, as the semester progressed, we improved. We were a college full of good students after all, and we learned to do things that would at least grab Guy’s attention: we swapped out descriptions, saying our blankets tasted like eggplant, the skunk smelled like the color turquoise. We didn’t know what we were writing, but at least we knew how to get a reaction out of him. We’d chop off the beginning and ending paragraphs of any story, because that always pleased him, and the rest of the time, we used the Mad Libs method for adjectives and adverbs: we ate nakedly, hurt vivaciously, drank primrose.

Guy saw through it all, of course, and would tell us our stories lacked integrity.

For hours afterwards, we would drink coffee and chain smoke trying to understand what it meant – how a piece of fiction could have integrity.

It was easier and far more enjoyable to participate in such philosophical discussions than to pound my head, once again, against my latest problem sets. About the only thing I remember from junior year was trying to apply Navier-Stokes equations to a series of seemingly simple scenarios, problems that always started by saying: Sally partially obstructed the opening of the garden hose with her thumb, assuming that water blah blah blah. Gilbert is hired to clean up an oil spill, assuming that oil’s viscosity blah blah blah blah.

Except you should know that I don’t smoke, and never have, even in college which is when you’re supposed to try such things. Instead, I would sit and inhale it all second hand, worrying about whether not smoking was somehow a betrayal of the entire writing experience, the back of my mind trying to make sense of Sally and her water hose, Gilbert and the viscous oil spill.

Looking back, it’s hard not to wonder how much of Guy was just affectation, an act he put on for his nerdy tech-ers. With his Einstein-hairdo and broad gestures, tobacco stained fingernails and talk of the artist’s life, the artist’s life damn it all, he was perhaps very actively, consciously, building a particular aura around himself.

Yet, despite all the posturing and undeniable drugs, he was a genius when it came to editing – he could turn pages of average ramblings into two enthralling sentences, never mind if the original intent had been lost along the way. He had rigorous rules about characters, that they were alive, and our children – and like real children (of which he had none, proof of higher forces at work, he would say) they would never shrug, would know the difference between lie and lay. And, he said, leaning in with a sibilant whisper, “Sometimes, not always, but sometimes, we have to eat our children.”

I never understood what that meant.

I’m not sure any of us did, really.

Anyhow.

If Guy were reading this now, he would probably throw his too-delicate musician’s hands in the air and say, as he did once, a long time ago, “You’ve missed the point completely, my darling.”

I’ll admit, that was always a bit of a thrill for me. I was a quiet, studious little Chinese girl: still a virgin at twenty, still raising my hand even in seminar discussions. To hear any kind of an endearment, especially from someone like Guy? Well, even something completely asexual, commonplace in a man like Guy’s vocabulary, it seemed somehow a triumph.

“You’ve finally got a story to write, a story that’s been forced upon you, and here you are, fucking it up.” Guy swore a lot, even when he was happy. One of the few men who could make “fucking it up” sound like poetry.

All semester long I had given him the usual stuff: old women cooking and praying to the kitchen gods, elongated versions of what happens when stairs are facing the front door of a house, the dangerous voodoo of living in a house located at the junction of a T-intersection.

Nothing personal, nothing private.

The one time I’d been too tired to make anything up and had relied solely on the strict and unvarnished facts of my childhood, of what all of that would mean within the context of my blossoming almost-affair with Yafeu, he’d pulled me aside after class and said, “Here you are finally! Here you finally are.”

And then he’d continued, the two of us huddled together in a corner of the small converted conference room used for smaller classes and seminars. “Do you know what I would give to have a real story to write right now? To have it thrust upon me?” He looked around and, as if noting that there was really nothing of value around him, nothing to help him make his point, continued. “I’d give a finger – this, this pinky – to have a story forced upon me, as it’s being forced upon you.”

And no, I’m not making that up, Guy did say that once to me, the first time I tried to write this. If it wasn’t the same, it was at the very least a very similar narrative: it’s my story after all, sans the husband and pregnancy, more than a decade ago.

“I’m not creative,” I remember saying.

Guy laughed. “With this,” he held the pages aloft, “With this you don’t have to be.”

“I’m not a writer. It’s not what I do.”

I remember Guy had shaken his head despairingly. “Just begin at the beginning. And try not to fuck it up,” he’d said.

If he were here right now, I’d try to explain that my time is limited. He’s not around to edit it. I’m not sure what to include and what not to.

He’d probably repeat, as he did back then whenever I made similar excuses, “Start with the important stuff. And don’t fuck up.”

Well.

Here goes.

Here is everything I would want to tell you, everything I think you should know about either me, my life, or just in general.

I’ll try not to fuck it up.

Apologies in advance.

3

I suppose I should start by telling you a little about my family, your family. I assume your father will handle his side of the story, so I’ll focus on mine.

Your great grandparents were all Chinese from China, which they would say is a distinction that matters. They fled from the mainland shortly after World War II — each had been members of the Kuomintang, which was one of the leading forces in overthrowing the last Chinese dynasty.

I tell you this because they would think it important, and it’s unlikely to be covered in your history classes.

They were all college students at the time: idealistic, energetic. They hated the Japanese (that’s something your classes probably will cover. If not, you can check out any book that talks about the Nanking Massacre, for that was their city of origin: Nanking. You can probably intuit the rest from the word massacre). They hated the Communist Party (for taking over the mainland shortly after the Second World War, and for, in their words, diluting and destroying the Chinese culture). To a lesser degree, they hated Taiwanese people as well: they’d only moved to Taiwan because they’d thought it would be a temporary relocation and didn’t think much of the natives, the islanders. Especially in later years, they hated having to explain to people that though they lived in Taiwan, they were not Taiwanese.

By the time of the wars, my father’s parents were already married and fled together. They were political figures who aligned themselves with Chiang Kai-shek, were quite influential within the Kuomintang, and, till their death, believed that the Republic of China (by then headquartered firmly in what the rest of the world called Taiwan) would somehow retake the mainland, overthrowing the Communist regime.

That was the optimism of their generation: that an island could overpower the most populous country in the world, that other nations would somehow rise up with them, when the timing was right.

My mother’s parents, on the other hand, got engaged because of the war. My mother’s mother was, I’m told, quite the beauty. Thinking back, I suppose you could say she still had a certain something about her, though I never saw any pictures of this younger, beautiful version of her. The woman I knew frowned perpetually, as though there was a putrescence to the world only she could detect. All of her stories centered on the unhappiness of her years, the weight of life: her husband had disappointed her, her children had all but abandoned her, and later, she would reveal that even her lover (though I don’t think she meant in the sexual sense, not that I asked, of course) had failed her.

More on that later, if I can get to it in time.

She chose my grandfather because he was ambitious (though later, she would say he was not ambitious enough), could provide for their eventual family, and also because he had enough gold to ensure the safe passage of her entire family. Both of them spoke of this freely.

My grandfather felt proud to have secured such a beauty.

My grandmother wanted everyone to remember: she had done her duty, saved her sisters and her young brother.

None of my grandparents had arranged marriages, though neither set could be classified as love matches. These were people who had made tough choices during difficult times, and then stuck with their decisions, regardless of whether it made them happy or not. My grandmother, the former beauty, used to tell me, “Choice is a privilege your generation enjoys – and takes for granted.” It sounded more pejorative in Mandarin, take my word for it.

Though both sets of grandparents visited the United States, neither stayed for long. They would never admit it, but Taiwan had become their home; everything else felt foreign. When they visited us, they would demand Chinese food from the best Chinese restaurants and then complain bitterly that it wasn’t authentic.

The sign advertised Shanghainese when really it was Schezwan!

Back home, they would have been embarrassed to charge money for that dish.

And so on.

I remember I used to ask my parents if my grandparents were hamming it up, playacting for us, intensifying their Chinese-ness. But my mother always said no, that’s how they’d always been. My father told me it was rude to ask such questions and then ruffled my hair, to take away the sting of his reprimand.

Most of our interactions happened in Taiwan, in their cramped apartments in Taipei and Kaohsiung. Summer vacations, I would fly there by myself, and my grandparents would take me to the markets: where you could pick which chicken you wanted butchered, where blood from the fresh fish dripped down the ice packs they’d been laid upon, so that your shoes became stained if you dawdled too long over a decision.

Of course I hated it.

Speaking Mandarin at home and going to Chinese school every other Sunday did little to prepare me for that level of immersion. My grandparents were forever correcting my Mandarin, asking constantly, “Have your parents taught you nothing? Is this how you communicate at home?”

Also, there were almost no children to play with – my grandparents were in their sixties and seventies. They played mahjong, they read the newspaper, they watched news on the three television stations Taiwan had available at the time. They had no idea what to do with a little girl and left me in their children’s old rooms, which had more textbooks than toys, more mosquitoes than could possibly be kept out, despite the layers of nets. They encouraged me to wear more dresses and more skirts and wrinkled their brows and their noses when I tried to explain the concept of “tomboy.” The beauty even asked me once if I was a homosexual. She’d heard that there were a lot of homosexuals in San Francisco.

I was nine at the time and told her that we lived in Modesto, not San Francisco.

When they tried to pay attention to me, they would inevitably tell me stories about their homes in Nanking, the servants and milk mothers they’d grown up with. Or they’d try to explain to me the various political machinations they’d been involved in or had written letters about.

Once, just once, my father’s father tried to show me how to whistle using a leaf from a mango tree.

This was the scene I had tried to write for Guy, years later. How my grandfather had looked in his checkered shirt, the top button open and revealing a glimpse of his undershirt beneath. His eyes closed in concentration, his fingers frozen around the leaf.

I remember the warmth of the sun on my neck, which means my always-too-long hair must have been up in a ponytail. I remember the flutter of the leaf, as he blew against it successfully, but not the sound it made.

It was the highlight of the month, possibly my entire summer.

I was five when the trips started, and I went every summer until I was ten. Five years of summers in Taiwan, spending four weeks with one set of grandparents, four weeks with the other. Five years of no one telling me why I’d been sent: that my parents were unhappy with each other, and that they were planning on getting a divorce but trying to make it work. That removing me from our house was somehow supposed to rekindle their romance, jumpstart their relationship. Give them a chance to try, try, try again for a son who would never come.

It was my father’s mother who finally told me, at the beginning of my last summer in Taiwan, that my parents were done trying and that, by the time I returned to the United States, everything would be different.

She sat me down on the edge of my bed, my father’s old bed, and explained that my father had tried, but living with my mother was just too difficult.

She said, “You understand, don’t you? That he doesn’t want to leave you?”

Out of all of my grandparents, she was the only one who consistently talked down to me, as if my poor Mandarin was part of a larger, overarching intellectual deficiency. I’d overheard her once, telling one of her friends that she worried about me constantly. She said she’d always known her son was smart, that he would grow up to be something, make something of himself. But I was different. I caused her much worry.

She always spoke slowly, always patted me on the hand in between sentences, asking me if I understood, squeezing my hand even when I told her I did.

“Of course he wants to stay with you. You know he would take you with him, if he could.”

Like I said, I was ten at the time. I understood that this meant my father was leaving and that I would be living with my mother.

“You know, of course, that he’s been unhappy for a while?” She liked adding the phrase “of course” to all of her statements and questions, even when something wasn’t obvious, when something was new knowledge.

“I didn’t,” I said.

“Your Chinese will never get better if you don’t practice it,” I remember her saying, as if I cared about my speaking skills at that moment.

“I didn’t know,” I repeated, in Mandarin. “I don’t understand why they would divorce.”

I wasn’t trying to prolong the conversation. And I wasn’t looking for sympathy. My parents never fought in front of me, never disagreed. They took me to parks together, drove me to recitals together. On weekends, they invited mutual friends and ate together, listened to music and talked about missing their family, their homes in Taiwan. Sometimes they held hands, even in front of company.

Unlike my friend Melissa, whose parents swore and fought constantly, my parents rarely disagreed. It had made sense when Melissa’s parents separated. This just didn’t.

My grandmother nodded.

“Your father is good at hiding his sadness.”

I remember she took my hand again, but didn’t hug me. I asked other questions, which I don’t really remember in detail now, but my grandmother’s answers were all more or less the same: my mother had failed her son.

I remember that’s when I realized what the divorce would really mean: that my father would be her son.

My mother.

Her son.

A new division of properties and relatives. An explanation and supposition of where my allegiance was expected, without anyone having bothered to stop and question what I might have chosen.

She reiterated that she had always had a feeling that the two of them would come to a bad end. She said that’s what happened when the doors of two families were not well aligned (my father was from old money, with generations of highly educated ancestors who had served in various government positions, unlike my mother’s family – a point my grandmother stated but then refused to elaborate upon).

I could tell, even then, that she was comforting herself rather than me. Her son was unhappy and would be leaving.

I was collateral damage.

Things got ugly (or uglier, if you prefer) after the divorce, something I only really understood years later, and I never saw my father’s parents again. We called one another occasionally, but the phone calls lessened over the years. I tried writing them once sometime during my high school years, in English, but my grandmother responded in Chinese. My mother would have been the best person to translate it, but it seemed wrong to ask, and eventually, I forgot about it.

My sophomore year in college, my father called to say that they’d both passed away in a car crash and that it was a blessing it had happened so quickly, for they’d been spared the normal indignities of old age. He said their passing was unfortunate, but the timing was fortuitous – he was having some financial stickiness (his word, not mine), but now that he had his inheritance, everything would be okay.

The letter’s tucked away in a box somewhere. I tried to read it again, once. But my Chinese was so bad that, by then, I could barely tell she’d addressed it to my Chinese name. There was a part, buried in the middle of the letter, where she referred to me as her good granddaughter. It’s too late to feel guilty about it now, but I do, a little.

****

Thank you for reading this excerpt of Unwell! If you enjoyed what you read, it’s available for purchase here as a print or Kindle book. If you read the book, please consider leaving a review! All honest reviews will be appreciated!