Alison McGhee's Blog, page 41

November 18, 2011

"Perhaps this soil is singing"

"Bees' eyes can pick up much of what ours can, but in addition they can see a wavelength of light, a color, impossible for us to perceive." (Philip Hilts)

"Bees' eyes can pick up much of what ours can, but in addition they can see a wavelength of light, a color, impossible for us to perceive." (Philip Hilts)

You often wondered, when your first baby, the boy with the fathomless blue eyes, was born, what was going through his mind. Thoughts that he had no language to express? Feelings beyond hunger, cold, pain, tiredness –beyond sensation?

You had no idea. You held him constantly in a dangling thing strapped to your chest, and you sang to him constantly as well. The same songs, over and over. You wondered if he ever heard the songs inside his baby head on the rare occasions when he wasn't with you. How could you know?

Once, back in those days, you poked your head into his room, silently so as not to wake him if he was still sleeping. He wasn't sleeping. Those blue eyes were wide open and staring up at something. Unblinking. You followed his gaze: the slatted blinds, half-closed at his window, were reflected and multiplied on the ceiling.

Dark bars, white slashes, dark bars, white slashes.

He watched and watched and watched.

Some time later, you read somewhere that infants are drawn to black and white contrast. You thought back to that day of the blue-eyed baby staring at the black and white bars. It made sense.

But did it, really? No. The fact that babies are drawn to black and white contrast means only that. You still don't know why he was drawn to the black and white. You never will.

He was seeing something that you didn't. He was seeing the world in a way that you had long outgrown, moved beyond.

When you began to read picture books to the blue-eyed boy, him on your lap, your arms around him, you realized that he saw the books in a way that was lost to you. Read him Goodnight Moon and his small finger would point to the mouse on each page. No matter where the mouse was hiding, he would find it, whereas your eyes went automatically to the printed words.

Two ways of seeing the same book. Two worlds in the same world.

You had a wave of sadness when you realized this, because you saw that you could never go back to the way the blue-eyed boy saw the world, because you knew how to read, and reading changes everything. Words first, pictures second.

The older you get the more aware you are of ways of seeing. Ways of perceiving. Ways of moving through the world.

Five years ago you moved into an old house with beautiful woodwork. Woodwork everywhere, from the box-beamed ceiling in the dining room to the handcrafted kitchen cabinets and radiator covers. Hardwood floors in every room. Gleaming, grained, hand-fitted wood, planed and shaped by the cabinetmaker who lived in the house before you.

Dear ___, what kind of wood are the kitchen cabinets made out of? They're so pretty. Thanks, Alison

That was the extent of the note you sent him. A simple question about the kitchen cabinets.

What came back was a long, long, long email detailing all the wood used in each room of the house. Cherry and oak and walnut and maple and birch, and all the variations and qualities of each.

Probably way more information than you wanted, I guess.

That was how he ended his email. But he was wrong. You saved that email and sometimes still you read through it to remind yourself not so much of the kind of wood in your house but of the love and devotion that someone else can bring to an ordinary something –wood, in this case– that you think you appreciate, but don't. Not really.

The friend who cuts your hair was born to cut hair and knew it from the beginning.

"I started cutting hair when I was in elementary school," she said. "I just knew how to do it. I would cut all my friends' hair."

"And you were good at it from the start, weren't you?" you said.

"Yes," she said, a simple statement of fact. "I was."

You were talking a few days ago with a friend who was attempting to explain various numbers on a budget chart to you. Some you got, some you had a hard time wrapping your head around, such as the numbers that count in one year but are actually carried forward to the next.

"It's another language," he said, "and there are people who know it as well as English. 'These are the four numbers that matter,' that kind of person will say, 'and here's why they matter.'"

He shook his head. "A page full of numbers, and they can read the entire story that those numbers signify in a couple of minutes."

This reminded you of your typing days, back in college and a few years beyond, when you typed papers for money. How you dreaded the math theses. All those numbers, all those lines, all those symbols, all that lack of words. Words are what you love, the very word-ness of them. Numbers, to you, are without story, without color and sound and sensation. Not so to the mathematicians, though.

You used to have –you still have, you just haven't seen him in many many years– a friend who was born for math. You met him the first week of college, in the mountains, and he was immediately one of your best friends but he couldn't stay there; he needed to be in a place where numbers were everything. He transferred to MIT and you used to visit him there, in that place where the buildings had not names but numbers.

You would wander from building to building and back to his apartment, where his desk was pristine –completely bare but for a pen holder and a perfectly aligned stack of papers covered with those numbers.

A few years later you used to visit him in Princeton, where he had gone to get his doctorate in numbers, the youngest of anyone you've ever known to have those three letters after his name.

How you loved talking with him about math, because he loved it so much. At one point he was studying something called manifolds. He tried to explain the concept to you.

"Manifolds," you said, trying to understand. "Manifolds. . . what color are they?"

He stared at you. You stared at him. You both started laughing. Different worlds within the same world.

Sometimes, after you graduated from college and moved to Boston, you would temp if you were in need of extra cash. Once in a while the agency sent you to MIT, the very campus where your friend had been a student just a few years earlier. Those same numbered buildings, that manicured grass, those right-angle cement walkways.

You remember a certain professor striding down the hall to the desk where you sat lamely attempting to replicate a scrawled page of numbers onto a computer screen.

"It's Alison, right?" said the professor.

"Right."

"So, what are you? A ballet dancer, I'm guessing. Or an actress."

"A writer," you said.

He nodded briskly.

"Ah yes," he said. "That would've been my next guess."

Meaning that you didn't see the world the way he did. Meaning that your lame attempt at replication was lame in the extreme. What could you say? It was true.

Now you have many artist friends, painters and photographers and sculptors and textile artists. They all see in the world things that you don't, that you miss, that go right by you.

The only time you draw anything remotely look-at-able is when you let go of the idea you have in your mind of what you're drawing. When you draw only what you see in front of you, the shadows and weird shapes and lines and curves that don't have any relation to the thing that you're looking at, but which, when you're finished, look so much more like it than if you'd tried to steer yourself rationally.

Yours is not the world of a visual artist, but when you pick up a pencil and work in this way you can almost feel, for a little while, what it must be like to see the world this way.

Nothing is ordinary. To everything in the world there is someone, somewhere, fascinated by it, born to it, someone who sees in it things that you never will.

* * *

"Perhaps this soil is singing. Perhaps June

ends with scents of lavender and heal-all

even though we cannot smell them, and soon

wind feels exactly like the sea. We call

this sundown. We welcome the full moon

fading to a white we have learned to doubt . . ."

November 15, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Ed Bok Lee

String Theory

- Ed Bok Lee

As a boy, I chose a beach ball

with a metal chopstick

over food & grown-ups

What wouldn't float away

despite any mouth

Some things choose us

Waking in a best friend's coffin

Falling asleep in a too-thin language

The slow, inward draw of a lover's

draining dream

Feathery rain that will never land

Sweet dry leaf sage translucent silver-

fish flee still dispatching oceans

Each time I burn the world pure

When the Lord created the sun

shadows unfastened themselves

Let there be the mature mind

Some things won't return

Let there be the unquenchable sea

Let there be an infant somewhere, always

in the city night, refusing to obey

He will speak through scissors

He will collect infinitely useless string

He will fashion a kind of belief

in subtraction's eloquence

–

For more information on Ed Bok Lee, please click here: www.edboklee.com

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

November 6, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Naomi Shihab Nye

Two Countries

- Naomi Shihab Nye

Skin remembers how long the years grow

when skin is not touched, a gray tunnel

of singleness, feather lost from the tail

of a bird, swirling onto a step,

swept away by someone who never saw

it was a feather. Skin ate, walked,

slept by itself, knew how to raise a

see-you-later hand. But skin felt

it was never seen, never known as

a land on the map, nose like a city,

hip like a city, gleaming dome of the mosque

and the hundred corridors of cinnamon and rope.

Skin had hope, that's what skin does.

Heals over the scarred place, makes a road.

Love means you breathe in two countries.

And skin remembers–silk, spiny grass,

deep in the pocket that is skin's secret own.

Even now, when skin is not alone,

it remembers being alone and thanks something larger

that there are travelers, that people go places

larger than themselves.

–

For more information on Naomi Nye, please click here: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/naomi-shihab-nye

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

November 5, 2011

Portrait of a Friend, Volume IV

Unlike most friends, this friend has been part of your life for as long as you can remember. He figures in your earliest memories, and there hasn't ever been a stretch of longer than half a year when you haven't been in his presence.

Unlike most friends, this friend has been part of your life for as long as you can remember. He figures in your earliest memories, and there hasn't ever been a stretch of longer than half a year when you haven't been in his presence.

That hat and shirt in the photo to the right stand as evidence of a rare instance of fashion coordination. The hat: plaid. The shirt: plaid. Two plaids = a well-matched outfit.

He's a tall man, a big man. He has a big presence and a giant voice. His laugh, when he gets going, will fill a room and make all those around him shake their heads in admiration. This is a man who likes to tell a story.

He's good at telling them, too. At the diner, where he goes every morning to meet his buddies for coffee, and where you go when you're visiting, they sometimes egg him on.

"Did you tell Alison about the woman who propositioned you at McDonald's?" one will say.

"Jesus H Christ!" he'll say. "No I didn't!"

"Are you kidding me?" you'll say. "A woman propositioned you at McDonald's?"

He will shake his head, that mighty laugh beginning to rumble out of him.

"Tell her," his friends will say. "Alison needs to know."

They will wink at you, and grin, while he looks down at the formica diner table, still shaking his head, still laughing. And then he'll tell it, in that giant voice, so that the whole diner ends up listening. And laughing. And shaking their heads.

He is a man who has never been accused of political correctness. Nor has he, unlike most people in the world, ever tried to be anything other than exactly who he is.

Sometimes he would come to visit you during the four years you spent at that little college in the mountains, where most of the other visiting adults wore pearls and linen dresses and suitcoats and polished shoes.

Over the Adirondacks and into the Green Mountains he would come, cresting the hill in a big old station wagon. The door would open and he would haul himself out. Those were the years of the neon orange polyester shirt and the polyester pants with the grease stain. Those were the years of your friends, unused to big men with giant laughs, unused to hearing "Jesus H Christ!" so frequently and happily roared out in public, looking forward to his visits.

"Al-oh-sun."

Despite a lifetime of knowing you, and despite the fact that your name is simple to pronounce, that is how he pronounces it.

"Alison," you sometimes say, even now. "A-li-son. Emphasis on the first syllable. Try it again."

He looks up and smiles, a gleeful little grin from a big man.

"Jesus H Christ!" he says. "I know how to pronounce your name, Al-oh-sun!"

This easy give and take, this banter, this happiness, wasn't always there. When you were little, you were often afraid of him.

Was it that big voice, his height and his bigness? He was a man of enormous physical strength. He often spent entire days chopping down trees, chainsawing them into big chunks, then smaller chunks, then splitting them into smaller and smaller chunks that, finally, were small enough to fit inside a woodstove.

You remember him once pouring Clorox over his bleeding arm: Disinfectant.

Unlike now, he was often angry.

Like most children, you assumed that his anger was directed at you. That you were the cause of it. That you must have done something to bring it on.

Like most of the grownups close to you, he was a familiar mystery. In retrospect, you didn't know him well. How could you? Each of you kept things hidden from the other.

You remember late nights when you were a girl, him working at the kitchen table, head bent over complicated graphs and charts, filling in tiny boxes with penciled numbers. He worked for a dairy farmers' cooperative; he was keeping track of milk counts at various farms. Or he was charting milk tank truck routes; milk has to be taken to a processing plant within a certain number of hours, and winter in upstate New York is fearsome and unpredictable.

You remember him figuring out other numbers, bent over a checkbook, writing check after check, paying bills.

"Where does it all go, though?" you remember saying once, when you were in your teens.

You were talking about the money that he made. It was an honest question, an idle question.

"Where does it go!" he roared. That anger again, or what you interpreted as anger, anger at you. "Where does it go!"

Later that night he called you out to that kitchen table. On it was a piece of ruled notebook paper. BUDGET at the top of the page. Underneath, line after line with things like Mortgage and Taxes and Food and Gas and Car Payment, each with a dollar amount jotted next to it. Exact dollar amounts, written from memory, subtracted and subtracted and subtracted from that single figure titled "Income."

"Now do you see?" he said. "Now do you see where it goes?"

Yes. Now you saw.

You didn't, not really. But later, many years later, when you yourself were sitting up late at night, your children asleep upstairs, dividing a small number over and over again, trying to make it come out differently, you remembered that night so long ago. That piece of lined paper titled Budget.

He was a young man, back then, which is something else you didn't know. Grownups, those mysterious beings. To a child, a grownup is born a grownup. Could you have imagined him, back then, as a child himself? No.

When you were a little girl you had no idea how young he was. You do now, though. You look back and you wonder at his youth. What went through his mind? What were his dreams? What had he put aside, for four children and the responsibilities that go with them?

Once, when you were about twelve and he was, what, 36, someone asked the people in the kitchen in which you were both standing this question. "If you could start your life over, would you?"

Almost everyone in the room answered immediately: "No."

But not him. "Yes," he said. "I would."

And not you. "Yes," you said. "I would."

Looking back, it seems impossible that you, at that age, could have answered that way. How in the world could you have lived long enough, lived through enough, to want the chance to do it over? But the memory is perfectly clear.

You remember looking at him –that big, tall man, often angry the way he was back then– and recognizing that something in him, something he had never talked about, was in you too. Even if neither of you knew what it was.

If he never talked about the big questions, he was full of small ones. When you would return from a day or overnight at a friend's house, for example, he would quiz you.

"What did you have for lunch?" he would say, "and what did you have for supper? Where did you sleep? How warm do they keep their house?"

He would lean forward so as not to miss anything, and you would describe it all.

"Jesus H Christ!" he would interject, fascinated and needing more details, which you would supply.

He loves a good story, and so do you. He will happily exaggerate if it will make a good story better, and so will you. His love of a good laugh, his keen interest in the people around him, his frustrated anger at his young children when he was a young man, his deadpan humor, his fierce need to make his own schedule, to be free, to get in his car and drive?

All these are in you too. Early on, you felt yourself so different from him. Not anymore.

Now, these many years later, you sometimes get eight or nine emails a day from him. Almost all are forwarded posts that he's gotten from others: astonishing or weird sights, political jokes, cute pictures of animals, unusual historical facts. Off-color jokes that almost always make you laugh.

Usually, the mere sight of a forwarded email, with those telltale and dreaded endless lines of recipients and senders, gets the automatic delete. Not so if he's the sender. You read them all. You respond to the ones you like best.

He likes late night solitaire. Sometimes, when you're going to bed, you picture him, far away in that house in the foothills, his still-big body perched on a small chair, gazing at the green screen, seven vertical rows of cards.

The sound of a baseball game turned low on a television in the background of a room, or a baseball game on the radio in a car, any car, brings you back to childhood. When you visit you sit and watch with him, arguing about the Yankees.

You're lucky people. Lucky to have both lived long enough to live through the storms. Not a day goes by that you don't get up in the morning and sit and bow your head and thank the world for that. For having come out on the other side. For the loss of fear and the gain of love.

In your 20′s you read a poem, this poem:

* * *

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love's austere and lonely offices?

* * *

You memorized it.

November 1, 2011

Some Writers Don't Keep Journals–

–and for good reason. Below are actual excerpts from the fifth-grade diary of a writer who, for the purposes of this blog, shall remain nameless. No animals were harmed in the transcription of these entries, and, despite the fact that the writer really, really wanted to revise many of them, not a single word has been changed.

May 13

Today I had my piano lesson. Everyone says I do beautifully. I think I do terribly.

May 14

Tomorrow is my New York trip. I can't wait. I'm so excited about it.

May 15

It was one of the most marvelous days of my whole life. It was just great.

May 16

Today was my boring Dress Revue.

May 17

Today we had Mr. Tibbetts and his wife up for dinner. The dessert was dreamy.

May 18

Next Monday we are going to change seating arrangements. I hope I get with you know who.

May 21

Today I had my piano lesson. I played baseball + made 2 runs.

May 22

We had gym today. I asked Mr. Roberts about my spelling prize and all he said was, "Moving Up Day." I can't wait.

May 23

We went to Granny's as usual. We had clam chowder. The way Granny makes it it's delicious! Yum!

May 24

I got into a group with ____!!! YAY!!!!!!!!

May 26

_____ hated our group so he moved out. I almost cried.

May 27

Today I had my piano lesson. Our school is holding a track meet.

May 28

Today is the end of Religious Ed. I didn't even go to it anyways.

May 31

In 4.H. I am making a wastebasket. It's real pretty. (I guess.)

June 4

Today was our track meet. Holland Patent won again. !!!!YIPPEE!!!!

June 5

I bought a $.50 milk chocolate candy bar. I love candy. I might get fat.

June 9

Wednesday! To me Wednesday sounds like it's all blue! That probably sounds weird!

October 30, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Spring and Fall: to a Young Child

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow's springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

–

For more information on Gerard Manley Hopkins, please click here: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/284

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

October 22, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Ece Temelkuran

Squirrel

- Ece Temelkuran (translated from the Turkish by Deniz Perin)

Truthfully, I ruminated when I came down from the tree.

Had sorrow made me say all these things?

Had someone been with me, they would say at once

that I was 'deeply wounded.'

I would like to show them

the squirrel that flickers in and out of sight, small as a crumb

but still able to animate the dark forest.

Her soul is surely the picture

of this tranquil elation that quivers and rests inside me.

The squirrel was drawing my path toward the forest.

–

For more information on Ece Temelkuran, please click here.

October 15, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Tony Hoagland

The Word

- Tony Hoagland

Down near the bottom

of the crossed-out list

of things you have to do today,

between "green thread"

and "broccoli" you find

that you have penciled "sunlight."

Resting on the page, the word

is as beautiful, it touches you

as if you had a friend

and sunlight were a present

he had sent you from some place distant

as this morning—to cheer you up,

and to remind you that,

among your duties, pleasure

is a thing,

that also needs accomplishing

Do you remember?

that time and light are kinds

of love, and love

is no less practical

than a coffee grinder

or a safe spare tire?

Tomorrow you may be utterly

without a clue

but today you get a telegram,

from the heart in exile

proclaiming that the kingdom

still exists,

the king and queen alive,

still speaking to their children,

—to any one among them

who can find the time,

to sit out in the sun and listen.

–

For more information about Tony Hoagland, please click here:

–

For Alison's Facebook page, please click here:

Manuscript Critique Service:

http://alisonmcghee.com/manuscript.html

October 9, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Taha Muhammad Ali

Meeting at an Airport

- Taha Muhammad Ali

You asked me once,

on our way back

from the midmorning

trip to the spring:

"What do you hate,

and who do you love?"

And I answered,

from behind the eyelashes

of my surprise,

my blood rushing

like the shadow

cast by a cloud of starlings:

"I hate departure…

I love the spring

and the path to the spring,

and I worship the middle

hours of morning."

And you laughed…

and the almond tree blossomed

and the thicket grew loud with nightingales.

…A question

now four decades old:

I salute that question's answer;

and an answer,

as old as your departure;

I salute that answer's question…

…And today,

it's preposterous,

here we are at a friendly airport

by the slimmest of chances,

and we meet.

Ah, Lord!

we meet.

And here you are

asking—again,

it's absolutely preposterous—

I recognized you

but you didn't recognize me.

"Is it you?!"

But you wouldn't believe it.

And suddenly

you burst out and asked:

"If you're really you,

What do you hate

and who do you love?!"

And I answered—

my blood

fleeing the hall,

rushing in me

like the shadow

cast by a cloud of starlings:

"I hate departure,

and I love the spring,

and the path to the spring,

and I worship the middle

hours of morning."

And you wept,

and flowers bowed their heads,

and doves in the silk of their sorrow stumbled.

–

For more information on Taha Muhammad Ali, please click here: http://www.poetryinternational.org/piw_cms/cms/cms_module/index.php?obj_id=3181

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

October 5, 2011

The story behind the picture book

She was tall, especially when you were a child. She was a big woman of girth and substance, with heavy legs of which she was ashamed all her long life. In her closet hung a neat row of size 22 flowered polyester dresses. Below them, a row of size 12 lace-up shoes.

She was tall, especially when you were a child. She was a big woman of girth and substance, with heavy legs of which she was ashamed all her long life. In her closet hung a neat row of size 22 flowered polyester dresses. Below them, a row of size 12 lace-up shoes.

It took her twenty minutes to roll on her orange support hose, but you never once saw her wear pants. She smelled of talcum powder and a perfume the name of which you can't recall. She had her hair done once a week at the beauty parlor, soft blue-ish white waves.

She did not drink, ever, but you remember twice at weddings she took a sip of champagne. Each time her button nose turned bright red and she hid her face in her hands and laughed.

You have written about her before. You always want to write about her. You have to stop yourself from writing about her more than you do, and also from talking about her more than you already do. Look at you, a full-grown woman of middle age, still talking about your grandmother?

But there you have it. She was one of the great loves of your life. You still miss her. You still talk to her. Out loud, sometimes. You say things like, "What do you think I should do, Christine?" and then you picture her and wait for her to answer.

Usually she just shakes her head in that way she had, and laughs the way she did.

"Oh, I don't know, Alison."

And then she reaches out and touches your arm and keeps looking at you, smiling, until you smile back at her. She knows that you'll be all right.

In her presence you always were all right.There was nothing you couldn't, or didn't, tell her. You told her things you'd done, heartbreaking things, and she would furrow her brow and tilt her head and nod. And reach out and touch your arm. And ask you questions, but only so that you could keep talking if you needed to.

And she would say how sorry she was that you had to go through that. That she knew you had done the only thing you could. That she herself just didn't see any other way around it.

In her presence you relaxed. You let down. Things inside you gave way. You didn't have to try so hard, around her. You didn't have to try at all.

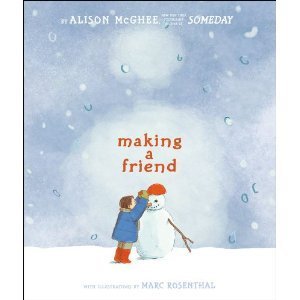

She is the story behind Making a Friend, that new picture book over there, the one with the pretty blue cover of the little boy and the snowman.

That little boy makes a snowman one day. He gives him arms and eyes and a nose and a mouth. He gives him his red hat, to keep him warm.

You were thinking about your grandmother the day you wrote down the first few words of that story in a notebook. You were thinking how lucky you were that she lived so long, that you were in your 30′s before you lost her.

Did you, though? Lose her?

When you really need her, you sit still and close your eyes. You picture her. There she is, sitting at the dining room table, head supported by one arm. She's wearing a blue bathrobe. She's smiling and shaking her head.

You sit there and wait until you feel her next to you. That if you open your eyes, right now, there she'll be.

You open your eyes and they rest on the needlepoint cushion she made, the one with her initials –CM– in the corner.

You open your eyes and they rest on the needlepoint cushion she made, the one with her initials –CM– in the corner.

You open your eyes and see a squirrel –her nickname– poised on the pine branch outside your window.

You go to the store and see that her favorite ice cream –butter pecan– is on sale.

That these are all ordinary things, things that happen on any ordinary day, means only that she is with you. It doesn't take anything special to conjure her. She is like electricity, invisible and everywhere.

A few years ago you were in a drugstore when you smelled her, that particular kind of talcum-y perfume she used to wear. You followed your nose from aisle to aisle, searching her out, until you stood directly behind an old lady wearing a dark blue coat. She turned to look at you inquiringly.

What could you possibly say, other than that you liked her perfume?

You said nothing. You lifted your shoulders and shook your head helplessly. You smiled at her. You wanted to thank her for bringing your grandmother back to you, there in the paper goods aisle.

The little boy talks to his snowman every day of a long winter, until all that is left is his own red hat. Snowman, where did you go?

"What you love will always be with you."