Alison McGhee's Blog, page 39

February 11, 2012

Poem of the Week, by Ross Gay

Overheard

- Ross Gay

It's a beautiful day

the small man said from behind me

and I could tell he had a slight limp

from the rasp of his boot against the sidewalk

and I was slow to look at him

because I've learned to close my ears

against the voices of passersby, which is easier than closing

them to my own mind,

and although he said it I did not hear it

until he said it a second or third time

but he did, he said It's a beautiful day and something

in the way he pointed to the sun unfolding

between two oaks overhanging a basketball court

on 10th Street made me, too

catch hold of that light, opening my hands

to the dream of the soon blooming

and never did he say forget the crick in your neck

nor your bloody dreams; he did not say forget

the multiple shades of your mother's heartbreak,

nor the father in your city

kneeling over his bloody child,

nor the five species of bird this second become memory,

no, he said only, It's a beautiful day,

this tiny man

limping past me

with upturned palms

shaking his head

in disbelief.

–

For more information on Ross Gay, please click here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ross_Gay

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

February 7, 2012

Things of this world

Last week you had a vivid dream in which the lyrics to a beautifully sad Willie Nelson song you'd never heard before went scrolling through your head. When you woke up you went to the computer and googled the first line: I have a thing for the things of this world, but no such Willie Nelson song exists. You took this as a sign that you needed to write a poem that began with that line. But you put it off.

Yesterday, while you were driving in the pre-dawn dark to a tiny airport on the Panhandle, you went through a drive-through to get a cup of coffee. You took the coffee from the nice girl, so sweet and patient there at the drive-thru window at 6 a.m., and said thank you. Before you got back on the road a message ticked into your phone. You checked it. Then you pulled off the road and sat there and read it again. You sat there and thought, no. Not possible. This was a man you have known all your life. He and his wife knew you before you were even born.

You sat there in the car and called your parents.

? you asked your mother, and . . . was her answer, and ? and . . .

I'll put your father on, she said, he's right here.

– and then your father was on the line, your father who managed to say He was my oldest and best friend before he burst out into those awful, heartbreaking sobs when he heard your I'm so sorry, I'm so sorry, and had to hang up the phone, and you sat there in the car for a while before you started it up again and pulled back onto the road.

Why is this so hard to write? Because it's not a poem, you can hear your father's oldest and best friend saying, although he was far too gracious ever to say such a thing. Poems rhyme, you can hear him saying, although that, too, he would never say. You think of that sad song you dreamed last week, the one you put off writing.

On the way to the tiny airport, there in the pre-dawn dark, animal eyes glinting from the ditches the whole way, you could picture them in your head: her, short and stout and devout, and him, smiling. You could hear his voice, hear the sound of his car door thunking shut in the driveway of your parents' house, hear the songlike melody of his deep voice. You could hear the Swiss relatives yodeling down the valley when you were a child lying awake at night. You could see their Christmas tree, lit and glowing through the window. You could see him in the barn with the baby calves, in the farmhouse before it burned down that awful year. All the way back to the frozen north, from airplane to airplane, he kept appearing in your head.

There he is, walking through the kitchen door. Walking into the diner because he heard you were home. Behind the wheel of a big old car on a dusty rural road, pulling off to the shoulder and waiting for you, the eternal walker, to run up to him so he can roll down the window and find out what you're up to. Telling you how special you are, how beautiful you are, things you know damn well he says to everyone he loves but which always, somehow, when you hear them from him, make you feel that way.

This is hard to write. It's not a poem unless it rhymes, you can imagine him saying –he never would say something like that, but he wrote a lot of poetry, and every line of it rhymed.

There is no time of your life that you can remember without him in it. He is threaded into everything that has to do with the place you still call home. There he is dancing the polka with your mother on the dusty second floor of the dusty rural dance hall. There he is standing in the field, telling you about the beaver pond and how gradually, over the years, the beavers have come to trust him, and how he will take you out to see them one of these days. There he is showing you the soft ice cream maker that they kept in their pantry, the magical soft ice cream maker that used to make a half-gallon of vanilla every night until he had the emergency triple bypass. After the triple bypass you wrote him a letter that must have said other things but all you remember is the one line that made you sit down and write it: Do you have any idea how much I love you? You remember how tight he hugged you next time you saw him.

When was the last time you saw him? Last fall, it must have been, when you were sitting in the booth at the diner with the men, all his friends –was anyone not his friend?– while he sat on the red stool opposite you until you got up and sat next to him on another red stool so you could talk just to him. Oh this is hard to write. You have begun and erased this at least ten times since you sat down at this table.

When was the last time you saw him? Last fall, it must have been, when you were sitting in the booth at the diner with the men, all his friends –was anyone not his friend?– while he sat on the red stool opposite you until you got up and sat next to him on another red stool so you could talk just to him. Oh this is hard to write. You have begun and erased this at least ten times since you sat down at this table.

Poems aren't big blocks of words, Al, you can hear him saying, even though he would never say such a thing. Poems rhyme. This isn't a poem, Charlie, you imagine saying to him. Make it a poem, Al, you can hear him saying.

Long ago there was a silent rift between you and someone dear to him, and you didn't know he knew about it, and you would not ever have brought it up, and you retreated, you backed up and away, you thought you might not have anything other than polite conversation with him for the rest of your life, and that should be all right, that should be enough, you were a grown woman for God's sake, you lived a thousand miles away for God's sake, but late one night when you were home visiting your parents you saw his car pull into the driveway and you leapt into bed and told your parents I can't talk, I'm asleep already, tell him I'm asleep, but –so utterly uncharacteristic– he went past them and came into the room where you were hiding and told you how sorry he was, and you could see it in his eyes, on his face, in the way he leaned toward you, huddled stupidly on the bed with the blanket pulled up around you. You hadn't ever seen a look like that on his face, his always-smiling, always-interested, always-calm, never-judgmental face.

This taught you something, which is that when you see a rift, repair it. Or at least try. So that you know that at least you tried. This is very hard to write because there is too much to say. There is too much to protest. Is there anything good here? you said to one sister last night, anything at all? You could feel her silence over the phone. Um, they were not young? They never saw it coming? They went together? They went instantly? No. None of these are good enough to make anything about this good.

This is going to be the biggest funeral that Steuben has ever seen, you said to her. There will be no place big enough to hold the mourners.

You want to write about him, to honor him, but you can't do a good enough job. Try some rhyme, Al, you can hear him saying, although he would never say such a thing.

Okay, Charlie, I'll try some rhyme. Here you go. This one's for you.

The news came that Charlie had died

his loved wife – his "bride"– by his side

I tried to write a poem in rhyme

but I knew there was not enough time

to say anything that needed to be said.

Too sad. Too many memories in my head.

A thing for the things of this world

Last week you had a vivid dream in which the lyrics to a beautifully sad Willie Nelson song you'd never heard before went scrolling through your head. When you woke up you went to the computer and googled the first line: I have a thing for things of this world, but no such Willie Nelson song exists. You took this as a sign that you needed to write a poem that began with that line. But you put it off.

Yesterday, while you were driving in the pre-dawn dark to a tiny airport on the Panhandle, you went through a drive-through to get a cup of coffee. You took the coffee from the nice girl, so sweet and patient, there at the drive-thru window at 6 a.m., and said thank you. Before you got back on the road a message ticked into your phone. You checked it. Then you pulled off the road and sat there and read it again. You sat there and thought, no. Not possible. This was a man you have known all your life. He and his wife knew you before you were even born.

You sat there in the car and called your parents.

? you asked your mother, and . . . was her answer, and ? and . . .

I'll put your father on, she said, he's right here.

– and then your father was on the line, your father who managed to say He was my oldest and best friend before he burst out into those awful, heartbreaking sobs when he heard your I'm so sorry, I'm so sorry, and had to hang up the phone, and you sat there in the car for a while before you started it up again and pulled back onto the road.

Why is this so hard to write? Because it's not a poem, you can hear your father's oldest and best friend saying, although he was far too gracious ever to say such a thing. Poems rhyme, you can hear him saying, although that, too, he would never say. You think of that sad song you dreamed last week, the one you put off writing.

On the way to the tiny airport, there in the pre-dawn dark, animal eyes glinting from the ditches the whole way, you could picture them in your head: her, short and stout and devout, and him, smiling. You could hear his voice, hear the sound of his car door thunking shut in the driveway of your parents' house, hear the songlike melody of his deep voice. You could hear the Swiss relatives yodeling down the valley when you were a child lying awake at night. You could see him in the barn with the baby calves, in the farmhouse before it burned down that awful year. All the way back to the frozen north, from airplane to airplane, he kept appearing in your head.

There he is, walking through the kitchen door. Walking into the diner because he heard you were home. Behind the wheel of a big old car on a dusty rural road, pulling off to the shoulder and waiting for you, the eternal walker, to run up to him so he can roll down the window and find out what you're up to. Telling you how special you are, how beautiful you are, things you know damn well he says to everyone he loves but which always, somehow, when you hear them from him, make you feel that way.

This is hard to write. It's not a poem unless it rhymes, you can imagine him saying –he never would say something like that, but he wrote a lot of poetry, and every line of it rhymed.

There is no time of your life that you can remember without him in it. He is threaded into everything that has to do with the place you still call home. There he is dancing the polka with your mother on the dusty second floor of the dusty rural dance hall. There he is standing in the field, telling you about the beaver pond and how gradually, over the years, the beavers have come to trust him, and how he will take you out to see them one of these days. There he is showing you the soft ice cream maker that they kept in their pantry, the magical soft ice cream maker that used to make a half-gallon of vanilla every night until he had the emergency triple bypass. After the triple bypass you wrote him a letter that must have said other things but all you remember is the one line that made you sit down and write it: Do you know how much I love you? You remember how tight he hugged you next time you saw him.

When was the last time you saw him? Last fall, it must have been, when you were sitting in the booth at the diner with the men, all his friends –was anyone not his friend?– while he sat on the red stool opposite you until you got up and sat next to him on another red stool so you could talk just to him. Oh this is hard to write. You have begun and erased this at least ten times since you sat down at this table.

Poems aren't big blocks of words, Al, you can hear him saying, even though he would never say such a thing. Poems rhyme. This isn't a poem, Charlie, you imagine saying to him. Make it a poem, Al, you can hear him saying.

Long ago there was a silent rift between you and someone dear to him, and you didn't know he knew about it, and you would not ever have brought it up, and you retreated, you backed up and away, you thought you might not have anything other than polite conversation with him for the rest of your life, and that should be all right, that should be enough, you were a grown woman for God's sake, you lived a thousand miles away for God's sake, but late one night when you were home visiting your parents you saw his car pull into the driveway and you leapt into bed and told your parents I can't talk, I'm asleep already, tell him I'm asleep, but –so utterly uncharacteristic– he went past them and came into the room where you were hiding and told you how sorry he was, and you could see it in his eyes, on his face, in the way he leaned toward you, huddled stupidly on the bed with the blanket pulled up around you. You hadn't ever seen a look like that on his face, his always-smiling, always-interested, always-calm, never-judgmental face.

This taught you something, which is that when you see a rift, repair it. Or at least try. So that you know that at least you tried. This is very hard to write because there is too much to say. There is too much to protest. Is there anything good here? you said to one sister last night, anything at all? You could feel her silence over the phone. Um, they were not young? They never saw it coming? They went together? They went instantly? No. None of these are good enough to make anything about this good.

This is going to be the biggest funeral that Steuben has ever seen, you said to her. There will be no place big enough to hold the mourners.

You want to write about him, to honor him, but you can't do a good enough job. Try some rhyme, Al, you can hear him saying, although he would never say such a thing.

Okay, Charlie, I'll try some rhyme. Here you go. This one's for you.

The news came that Charlie had died

his loved wife – his "bride"– by his side

I tried to write a poem in rhyme

but I knew there was not enough time

to say anything that needed to be said.

Too sad. Too many memories in my head.

February 4, 2012

Poem of the Week, by Maria Baranda

(Excerpt from) 1

– Maria Baranda (translated from the Spanish by Joshua Edwards)

Everything begins with the moon and a desolate sky,

a place of frail words to open

the native prose of dreams. Calm

country poplars, Indian laurels

rise up, anxious on this island of memory.

There go the men who sail into port

when the word burns like a suburb

of truth, a mark on the page

that formed the earth. They approach too quickly.

They have lost the light and now break open a sea curd

in which time crackles.

They want to erase their names, to plant scams

in slow spirals of foam.

They recite a verse in an exiled country

like a clear net around infinite oceans.

There is blood between the rocks.

You listen to them. You wait for their silence.

You know they constitute an era.

Who will defend them from themselves?

Who will endure their eternal burden,

their first night of wind?

They'll remain in books forever.

Syllables of gratitude, sentences where the remnants

of their century glimmer.

They are a sliver of light within the atlas of time.

You pray for them.

You open a coconut and you drink from it.

Bells ring where birds chirp,

where fish throb with the calmness

of a heart that's on its own.

Once again the dream flows beneath your palm-thatched hut.

Who delights in you? Who says such prayers for you?

–

For more information about Maria Baranda, please click here: http://www.shearsman.com/pages/books/authors/barandaA.html

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

January 28, 2012

Poem of the Week, by Jim Harrison

June the Horse

- Jim Harrison

Sleep is water. I'm an old man surging

upriver on the back of my dream horse

that I haven't seen since I was ten.

We're night riders through cities, forests, fields.

I saw Stephanie standing on the steps of Pandora's Box

on Sheridan Square in 1957. She'd never spoken

to me but this time, as a horse lover, she waved.

I saw the sow bear and two cubs. She growled

at me in 1987 when I tried to leave the cabin while her cubs

were playing with my garbage cans. I needed a drink

but I didn't need this big girl on my ass.

We swam up the Neva in St. Petersburg in 1972

where a girl sat on the bank hugging a red icon

and Raskolnikov, pissed off and whining, spat on her feet.

On the Rhône in the Camargue fighting bulls

bellowed at us from a marsh and 10,000 flamingos

took flight for Africa.

This night-riding is the finest thing I do at age seventy-two.

On my birthday evening we'll return to the original

pasture where we met and where she emerged from the pond

draped in lily pads and a coat of green algae.

We were children together and I never expected her return.

One day as a brown boy I shot a wasp nest with bow and arrow,

releasing hell. I mounted her from a stump and without

reins or saddle we rode to a clear lake where the bottom

was covered with my dreams waiting to be born.

One day I'll ride her as a bone-clacking skeleton.

We'll ride to Veracruz and Barcelona, then up to Venus.

–

For more information on Jim Harrison, please click here: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/jim-harrison

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

January 25, 2012

Portrait of a Friend, Vol. V

You were listening to voicemails on speaker phone in the kitchen the other day, standing by the sink as your youthful companions and their friends sat around the table eating grapes. Most of the voicemails were short and to the point: Meet me then, see you there, can't wait, talk to you soon.

You were listening to voicemails on speaker phone in the kitchen the other day, standing by the sink as your youthful companions and their friends sat around the table eating grapes. Most of the voicemails were short and to the point: Meet me then, see you there, can't wait, talk to you soon.

One of the voicemails was not short and to the point. It was long and rambly. It included a brief pause: "Hang on, I've got the dog and I have to cross the busy street now!" and then picked up again: "Okay, I just crossed the busy street!"

Maybe you were laughing as you listened, or maybe you were just smiling, but one of your youthful companion's friends turned to her.

"Who's that voicemail from?" she said.

"Her bff," said your youthful companion. "Can't you tell?"

Yes. The friend could tell. They watched you as you hung up the phone (can you use the term "hung up the phone" for a phone that is shaped like a small flat brick and has no discernible buttons? Probably not). You must have still been smiling.

"Do you wish you lived across the street from your best friend, Mom?" asked your youthful companion, who, because she has grown up listening to you on the phone with your best friend, long conversations which often end with If only you lived across the street from me, already knew the answer, which is yes. Unequivocally yes.

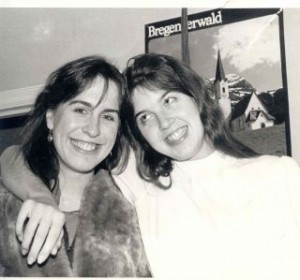

There was a time when you lived, not across the street from your best friend, but down the hall. And then across the hall. And then a few hundred yards away. Those were the years that you were in college together, at that little school in the Green Mountains. Even then, back when time, although it was precious and you knew it, seemed endless, you knew how lucky you were to have all those endless days with her.

She was the first person you met on the first day of college. Your parents had helped you lug your boxes and bags out of the old station wagon and up to the fourth floor of the dorm, and then you had waved goodbye to them and watched the wagon disappear down Route 125, back to the Adirondacks, and then it was time to go get your student i.d. card.

You took your place at the end of the long line snaking out of the student i.d. card building and looked around at the golden trees, the mountains rising all around you, the chattering students, none of whom you knew. This was your new life. This was the beginning of a life that you hadn't yet lived.

The girl directly in front of you was tall and slender. She had honey-brown hair that reached just below her shoulders. You couldn't see her face. As you recall, she was wearing her jean jacket. She was also wearing hiking boots, and you remember looking down at them and admiring their bright red laces.

She must have taken out the laces that came with those boots, you remember thinking, and then she bought new red laces and re-laced them.

This struck you as unimaginably creative. Had such a thing ever occurred to you? No. You had gone your entire life meekly accepting the laces that came standard-issue with your sneakers and shoes and boots. This girl had not.

You decided to take action and tapped her on the shoulder.

"Do you know by any chance know where the dining hall is?"

This is what you remember asking the girl with red-laced hiking boots, but it's possible that you asked her an entirely different question. Any question would have done the trick.

"I do!" she said. "I'll show you where it is. What dorm are you in?"

That is what you remember her saying to you, and while it's possible that she said something partially different, the dorm part of it is right. That much you know for sure, because as it happened, she lived just down the hall from the room into which you and your parents had just lugged your belongings.

That night you went to dinner, there at the dining hall, with her and some of the others from the fourth floor of your dorm. In your memory, that was the day that she became your best friend. Did it maybe take a little longer than that, like, a week or so? Maybe. But maybe it was just as effortless as you remember it: Stand in line behind a girl with red laces in her hiking boots, strike up a conversation, become best friends.

It's worthwhile to remember that some things don't take work, don't have to be nose to the grindstone, don't have to be struggled over. Some things really are effortless.

She was 17 and you were barely 18 when you met, and ever since you have been threaded through each other's lives, warp and woof. When her number appears on the screen of your little mango-colored brick of a phone, you press the green button.

"Oh thank God it's you," you say.

"Oh thank God you're there," she says.

That is always the feeling that fills you, at the sound of her voice: thank God. The hugeness of your relief at the mere sound of her voice seems vastly disproportionate to the weight of your conversations, which are usually not weighty at all.

But there you have it; you give way with her. Now you're thinking of how, when a football player gets injured on the field, the coach and the trainer put his arms over their shoulders and help him off the field, so that he doesn't have to bear all his own weight on his own two feet. That's how the sound of your best friend's voice makes you feel.

Back at college there was a long, steep, tree-lined hill, the one that led up to your dorms. At the bottom of the hill was the library, classroom buildings, the gym. Farther yet down the hill was the little town.

"Allie, I just do not have the strength to make it up this hill," she would say, after a long night of studying in the library or a long night of dancing at the bar. "I simply cannot do it."

And you would get behind her and brace your arms against her back and lean in and literally push her up the hill. Strangely, the act of pushing her up the hill also made your own trudge up the hill easier.

Like so many of those you most love in this world, she has always been who she is. So, in a way, have you. Early on you knew things about each other: that she would spend her spare pennies on art, art of any and all kinds, from a pretty scarf to a handmade notecard to a tiny silver ring, that you would spend yours on a plane ticket to anywhere. And that both of you would spend it on a double-dip Steve's ice cream cone.

In college, she loved the color blue and all its variations: teal, lavender, navy, and whatever the name is of that particular kind of blue that exists in bottles lined up on a white windowsill to catch the sunlight. She still does. There is a room in the house she lives in now that is blue, and it's her room, and she calls it the "blue room."

In college, she loved the color blue and all its variations: teal, lavender, navy, and whatever the name is of that particular kind of blue that exists in bottles lined up on a white windowsill to catch the sunlight. She still does. There is a room in the house she lives in now that is blue, and it's her room, and she calls it the "blue room."

She has never been able to bottle up, for long, something that troubles her. This does not translate into a hot temper, or a quick trigger; what it means is that if something is bothering her, she will talk about it. She will work it out.

This is something that you have always envied and admired about her: she will not hold within herself anything that threatens her sense of who she is or what is right. You have learned so much from her in this regard. You can't always put it into action the way she can, but still, even if it's taken decades, you've gotten better at it.

Something else about her that seems unrelated and yet somehow, yes, related to this refusal to bottle things up is her astonishing and wondrous ability to nap.

"Allie," she would say in college, in the late afternoon, after classes and before dinner. "Wake me up in 20 minutes, would you?"

At first you thought she was joking. Wake her up in 20 minutes? How could anyone just lie down on a bed and fall asleep like that?

Your own earliest memories include staring at the cracks on the ceiling above your crib, waiting. Waiting and waiting and waiting, for your mother to come in and lift you out of the damn thing.

And yet 20 minutes later, knock knock knock, there she was, peacefully asleep. It was like a parlor trick. To this day, she is a master of this particular parlor trick, and to this day, you still marvel at it.

Back then, one of your daily goals was to make her laugh so hard that tea would come out her nose. This was not a rare occurrence. It would happen near the end of dinner time in the dining hall, when you and her and your other friends would postpone the return to the library by drinking endless cups of coffee and tea.

Come to think of it, this tea-out-the-nose-thing is still one of your goals.

Back then you liked to go to parties or out dancing, her in the lavender shirt and you in the red shirt that in your memory you both wore every weekend. You'd wait until the cover charge at the Alibi was half-price and then in you'd go. That tiny dance floor, that long wooden bar, the pool tables downstairs, the bathrooms that everyone tried to avoid. That bar is still your favorite bar in the entire world, despite the fact that it exists now only in memory.

You typed papers to make money in college and she was a checker at the dining hall. This meant that she sat on a high stool at the entrance while students filed in, each reciting their i.d. number, which she then checked off a long list of student i.d. numbers.

Hers was a powerful position, a position of social engagement and deep intrigue, because everyone had to file past her on the way to the cafeteria line. Those were the days of myriad crushes, for both of you, and many was the time that you stood in line directly behind one of hers, trying with all your might to catch her eye, because you knew she would start to laugh, and then she would not be able to stop laughing, and then either the secret would be out or the tea would come out the nose, or, if you were really lucky, both.

Years passed, and you both left the mountains and moved to that city by the sea, where for those first few years you lived on the cobblestone street by the river and she lived three cobblestone blocks up the hill, just down the street from Primo's Deli.

In the late afternoon she would come down to your tiny one-room apartment before her waitress shift at the chi-chi restaurant down the block. She would be wearing her green chi-chi restaurant waitress apron, the one with the big pockets to hold a corkscrew and tips, and she would sit down in your one chair, the one you sat in to type out your stories on the typewriter balanced on the apple crates.

She would sit, and you would stand, and the two of you would talk as you French-braided her hair. Sometimes you would braid it in a single braid down the back of her head, sometimes two braids that you tied with ribbons. Once in a while you would braid a single braid that wrapped around her head; that was your favorite. It was the most challenging, the most unusual.

Off she would go for her shift, and late that night, when the restaurant closed, back she would come and tap on your window (you lived on the ground floor) to see if you were still awake. If you were she would come in and you would sit on the floor together. She would empty the big pockets of the green apron and you would count her tips together and talk about the customers, the tables, the other waiters and waitresses.

You might light a Duraflame log in the tiny fireplace that somehow, magically, was built into the tiny room, and you might talk late into the night.

You remember the party in that city by the sea where she met her future husband. It was late, very late, and there had been much music and much dancing and many drinks and much merrymaking, and he wrote her phone number on his palm with ballpoint pen and then kept his wits about him enough, once he made his drunken way home, not to wash it off.

That was it, for her and for him, and a couple of years later she was sitting on a chair in a distant bedroom, a long white dress spread carefully around her, and you were standing in back of her, slightly bent, your hands in motion, French-braiding her silky hair.

You don't know, when you're 18 years old, what life will hold. You don't know that there will be more times than you imagine, back then, when you feel as if you can barely hang on. Those times have come for the both of you, as they do for everyone.

Unlike your best friend, you did used to keep secrets. One in particular. All the years of college in the mountains, those mountains that turned to flame every fall, and for years before you went to college, you were keeping a secret that was literally eating you up from the inside out. It felt, back then, as if your survival depended on keeping this secret.

You hated yourself for what you were doing, but even though you vowed every day to stop, you couldn't. This is why you look at the trembling fingers and the dark eyes and the jiggling legs of certain people you know, some of your students, people you pass on the street, and you can feel their self-hatred, their desperation, and you look them in the eye and send them silent strength.

You kept your secret from everyone: your family, your friends, your boyfriend, and even her, your best friend. You never told it to anyone. It took two years after college –long, hard years of silent, solitary, daily, baby-step work, of sitting on the floor of your tiny room on that cobblestone street, the sun shining in the window, talking to yourself– to climb your way out of that wilderness of your own making.

When you knew that you were out of that wilderness, truly out, you sat down and wrote letters to everyone you loved, everyone who knew you best, and told them what you had kept hidden all the years they knew you. It was awful, terrifying work, writing those letters.

You dreaded writing to her. You dreaded telling her what you had never told her, all those years of your best-friendship, when she had kept nothing from you. You imagined her opening the letter –it was not something you could tell her over the phone; it was not something you could tell her in person; you knew she would need time– and all your imaginings were awful. You felt your own self-hatred stealing back into your body.

You put a stamp on the letter anyway and carried it down the street and put it in the blue mailbox. Two days later she called.

"Allie, I got your letter," she said. "This is going to take me time. This is terribly hard for me. I can't talk about this now. But I had to call you and tell you that I love you. I love you. Just know that."

I love you. She knew you so well that she knew you had to hear those words, so that you could keep going while she, on her end, did what she needed to do to get through. During those dark days, while you waited, you kept her voice and those words in your mind.

What did you learn, from others who called and wrote when they got those letters, who came to your tiny apartment and literally held your hand, who wrapped their arms around you, who told you how sorry they were that you had gone through that, that they hadn't known, that it hurt them to think of you going through it all alone, believing yourself unlovable? What did you learn from all of them, but especially from her, your best friend?

That the power of love is formidable. That love can, in fact and in act, be unconditional.

You remember her standing with you outside the little stone church when you yourself got married, holding your hand. And you remember her voice on the phone many years later, when you could not stop crying, agonizing over the hurt that your children and those you loved would have to endure by a decision that you had to make, and her voice like a murmuring river. Her voice on the other end of the phone, telling you that everything, including your children, in the end, would be all right.

Oh thank God it's you.

Oh thank God you're there.

Best friends can live 1500 miles apart and see each other only a few times a year. But another thing about love is that it is transcendent. It knows nothing of physical distance or the clocks by which we measure out time.

You have been through the fire with each other. You have watched each other go through things that neither would have wished on the other, were you in charge of the universe.

There have been times when one or another of either of your children were in pain, true pain, and you hung on tight to the phone and said to each other, If only I could do it for him, or, If only I could go through it for her, so that she wouldn't have to suffer.

Such is the nature of love. And such is the nature of life that you can't. All you can do is hang onto the phone for dear life, lie awake at night breathing in, breathing out. Breathing in thank you, breathing out goodbye.

Once, you were going through something bad, and she knew it, and you knew it, and you tried to pretend you weren't, and she knew you were pretending, and it became something that you couldn't talk about, but which you tried to talk around. That you chattered around, trying to fill the space of what you weren't talking about with words, any words, none of which worked.

There came a period of time in which, because of everything that wasn't being said, there were not many phone calls. Then one day the phone rang, and you could hear the determination in her voice, the same determination you have heard all your life with her. She is not one to keep things bottled up inside.

This has become something that we can't talk about, she said, but I woke up the other day and I knew that if you weren't talking about it with me, you weren't talking about it with anyone. And you need to. And so I decided that all I can do is love you. And that is the easiest thing in the world for me.

Your entire body sagged with relief.

So, she said then, I'm going to listen. Now talk.

And finally, you did. Because you could. In your life there have been three people, including her, who see you as you are and for whom that is enough. Who have never asked or expected or wanted you to be anything other than who you are.

This makes you a lucky, lucky person.

The years go by, don't they? They just keep right on going by. Last October you were holed up in your one-room shack in the Green Mountains, trying to finish a novel. It was a lonely slog, and you were alone, and suddenly you didn't want to be alone anymore. You flung your clothes into your duffel and got behind the wheel of the rental car. It was late afternoon. You called her.

"Oh thank God you're there."

"Oh thank God it's you."

"Listen, I'm at the shack and I can't take it anymore."

"Come on down!"

"I'm already in the car."

You slept in her away-at-college son's room. You wrote the novel while she and her husband were at work and their daughter –whom you think of as your niece– was at school. You sat on the blue couch in the family room, light pouring in the windows, surrounded by the things your best friend loves: the family photos, the heart-shaped rocks, the collection of sea glass that she picks up on the beach.

You were not alone. You were not lonely.

You are typing this at 23,000 feet in the air, which is neither here nor there in terms of your best friend, except that looking down on the patchwork earth below has the effect of making you envision all the years of your friendship as if seen through a telescope.

Has there ever been a day since that red-lace hiking boot day so long ago that she has not been a part of your life, and you part of hers?

The answer, no, feels like a revelation, although it's anything but.

And the question that immediately follows –what would I do without her?– also feels like a revelation, although it, too, is not.

When you think of her, what is the first thing that comes to mind?

Is it her smile, that wide smile that so often ends in a laugh? Is it the sight of her on the blue couch in her family room, her husband's head in her lap, him half-asleep as she rubs his head? Is it her distinctive handwriting, which is not handwriting but printing, and the especially distinctive way she forms her "E"s?

Her letters and postcards and birthday cards? There are a couple of boxes in the wall of boxed-up letters from all the people you love, labeled with her name and sent from Vermont, from London, from Connecticut, from Massachusetts, from all the places that she has called home over the years. Is it her hair, that silken bob that has not changed in all these years?

Whatever it is, it's not the red laces in her hiking boots. They already served their purpose, that long-ago day when you first thought up that "do you know where the dining hall?" question, just so you could start a conversation with her.

It has been many years since you French-braided your best friend's hair. Next time you see each other, a few months from now, maybe she'll humor you and let you braid it again for old time's sake.

Oh thank God it's you.

Oh thank God you're there.

January 13, 2012

Ghazal*

Ocean Ghazal

He came spiraling back up the stairs, all four flights, two at a time

Dark coat flying, dark eyes searching, something more to tell her, that last time.

At night by the ocean, salt spray and laughter and a dive in dark water.

Kisses, soft, then silence and her body, alive with longing. It was time.

A stranger on a yellow windsurfer like his, slicing through the northern ocean.

Curving the board back and forth to shore before her, the girl displaced in time.

Memory conjures a face, floating beyond the streaks of the bus window.

Please, please tell her what you didn't, those last weeks, running out of time.

Pesto is garlic and basil, oil and cheese. Salt. Dip your finger in green,

deep green its taste, green your finger in her mouth, green still seen in time.

When someone dies where do his memories go? Memories only you two know?

You are so much older now than that day he left you behind in time.

January 7, 2012

Poem of the Week, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

If thou must love me, let it be for nought

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning (from Sonnets for the Portuguese)

If thou must love me, let it be for nought

Except for love's sake only. Do not say

'I love her for her smile—her look—her way

Of speaking gently,—for a trick of thought

That falls in well with mine, and certes brought

A sense of pleasant ease on such a day'—

For these things in themselves, Belovèd, may

Be changed, or change for thee,—and love, so wrought,

May be unwrought so. Neither love me for

Thine own dear pity's wiping my cheeks dry,—

A creature might forget to weep, who bore

Thy comfort long, and lose thy love thereby!

But love me for love's sake, that evermore

Thou mayst love on, through love's eternity.

–

For more information on Elizabeth Barrett Browning, please click here: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/152

–

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

January 5, 2012

Two picture book writing workshops offered next month!

PICTURE BOOK WRITING WORKSHOPS

PICTURE BOOK WRITING WORKSHOPSAny picture book writers feeling isolated out there? I'm offering back to back one-day picture book manuscript workshops next month. We'll talk about the fascinating/fiendish (take your pick) specific challenges of writing these fabulous little books, including the essential elements of picture book writing: characters, story arc, language, beginnings and endings, voice and tension.

If you wish, you can bring in copies of a manuscript of your own (no more than 700 words) and we'll read it aloud and discuss it. Or, just come and absorb whatever's useful to you and your current or future work. Workshop is limited to a maximum of ten.

Dates: Saturday, February 11, and Sunday, February 12,12:30-4:30 p.m.

Place: my house in Uptown Minneapolis.

Cost: $50, including hand-outs and some kind of tasty homemade treat. Please email me at alison_mcghee@hotmail.com if you have questions or would like to sign up (specify which day you prefer). And please feel free to share this info with any interested friends.

January 3, 2012

a pretty a day (and every fades) is here and away -

One of your youthful companions wants to be Amish. The first time she saw a horse-drawn buggy and a bonnet-clad little girl dangling her feet off the seat, she turned to you and grabbed your hand.

One of your youthful companions wants to be Amish. The first time she saw a horse-drawn buggy and a bonnet-clad little girl dangling her feet off the seat, she turned to you and grabbed your hand.

"Look!" she said.

"Those people are Amish," you said. "They ride in buggies instead of cars."

She must have been about seven.

"I want to be Amish," she said.

You started to laugh but then you didn't, because you saw that she was serious. This was out in the country, far away from the city in which you lived then and in which she still lives when she's home from college. She followed the buggy's slow, creaking journey with her eyes until the horse rounded a corner and it was gone.

"Yup," she said. "That's what I'm going to be when I grow up. Amish."

She's pretty much grown up now, but she still declares, once in a while, that she's going to be Amish. Computer, cell phone, car, short skirts and tank tops and bikinis and movies and late nights at First Avenue and airplanes and passport and and and and and all of it, she says, all of it can go. She will gladly give it up to be Amish.

But not really. The collection of books by Amish people and about Amish people, the little Amish boy's handmade jacket, the Amish mug, the buggy crossing signs you bought her as a joke, her whole collection of useless Amish artifacts notwithstanding, she wouldn't really do it.

What she wants, at heart, is not to be Amish, but to live more simply. She wants more quiet, less chatter. She wants homemade fun.

This is the girl who, at family reunions held in a timewarp inn in the mountains of New Hampshire, will square dance the night away, collect eggs from the chicken coop, gather with her cousins and aunts and uncles three times a day at a long table, play Bingo, watch a magic show.

Fully part of the world the way it is, with all its electronics, she still wants it to slow down.

You don't blame her. You do too. When she and her sister were younger, you read them to sleep every night. Lots of books, including the entire Laura Ingalls Wilder series. A cliche, but so what. Even when you were little, back when the world wasn't as fast, you wanted to live that log cabin life. You wanted to gasp in wonder at the sight of an orange in your Christmas stocking.

You wanted a letter –the very paper it was written on– to be so precious that you saved up your news for months and then wrote diagonally, in tiny script, beginning in one upper corner triangle and covering the entire page before turning it over and filling every millimeter of the other side.

A handwritten letter is a beautiful thing. See that box way up in the righthand corner? In case you can't tell (this was supposed to be a biggish, sharp photo but, per usual, it ended up tiny and indistinct), it's full of handwritten letters sent to you over many years.

That particular box is one of ten such boxes that fill three long wall cupboards. Open the doors and there they all are: pretty much every letter ever sent to you from high school on. You never throw out a handwritten letter. Or a handwritten card. Or a handwritten postcard.

How could you? Someone, somewhere, sat down at a table, or a desk, or propped a book on their lap on a train or a bus, or pulled down the tray table on an airplane, and laid out a piece of stationery, or a notecard, or a postcard, or a napkin or the back side of a bank statement or an electric bill, and picked up a pen, or a pencil, or a crayon, and then wrote your name.

Dear Alison.

Dear Dragon Lady.

Dear Allie.

Dear daughter, granddaughter, sister, friend.

Dear.

Like so much else –the journals you've kept about your youthful companions, the notebooks filled with scribbled thoughts and ideas for future stories and novels and poems– you never looked at any of these saved letters until a few months ago. For decades you've dragged them all with you wherever you went, from apartment to apartment to house to house, thousands of miles in all: tripled-up plastic garbage bags, sagging coverless cardboard boxes, even double-bagged brown paper grocery bags full of them, hundreds and hundreds of letters. Thousands? Probably.

But when the Amish aspirant went to college you hauled them all out, determined once and for all to go through them, organize them, put your life in order, beginning with these sagging boxes and bags of letters letters letters. For God's sake, anyone looking in that closet would think you were one of those hoarders.

Besides, everything in you was raw, anyway, with the Amish aspirant so suddenly gone, her room all messy and her bed unmade as if she would be climbing into it that night, but no, she wouldn't be, she was a thousand miles away, so it couldn't hurt to rip off a little more skin. Right?

But it didn't hurt at all. That was the amazing thing. It was like watching a silent movie playing inside your brain, sorting those letters into piles by sender.

You only read some –it would take a year to read through all those letters– but even in the not-many you looked through, you couldn't have imagined how transfixing it would be, just a few sentences written twenty years ago being all it took to conjure up the face and laughter of someone you love. You couldn't have imagined how hard you would laugh. Or that sitting there holding a letter from someone you love would feel as if you were holding their hand.

Did you even know you had so many friends? That there were so many people out there you adored?

Yes. You did. But to see them all strewn around the bed and the floor and the shelves, piled by sender, was astonishing. The room was full of words, floating in the air. Full of voices. Faces.

Everyone's handwriting is distinct. Most of the letters you needed only to glance at your name and address and you knew immediately which pile it belonged to: Ellen, with her distinctive E's. Meredith, with her forward-slanting print. Christine, with her Palmer method script. Doc, those perfect capital letters in black Sharpie. DC, tall leaning lowercase. Stinky, a third-grader's scrawl. JO's delicate half-cursive that looks as if she barely presses down on the pen. Jeff, whose y's have that long hooked tail. Gabrielle, leftie with the backslanting leftie script. Bock, with his multi-colored crayoned envelopes. And so many others.

Aerograms. Pale blue lightweight airmail fold-and-stick stationery on which you wrote and received dozens of letters, back in the day. Here's a pile from DC, sent mostly from Asia, during that year or two when all his addresses began with Poste restante.

You remember him calling you –this was right after you'd both graduated from college, and you were living in the tiny room trying to be a writer and typing papers to pay the rent and he had gotten an office job of some kind, insurance? finance?– and telling you that he felt as if he was suffocating. That he had to get out.

"What should I do?" he said. "What am I going to do?"

You didn't know. You sat there at your typewriter, propped on two apple crates in front of your folding chair, all of which you'd scavenged from the curb on garbage night. It was a penniless sort of life but it was penniless on your own terms. You listened to him talk about traveling, and next thing you knew, poof – he was gone, quit his job, jumped on a plane, with the trickle of aerograms that began shortly thereafter as proof.

DC, poste restante.

Those aerograms are here in this box, right now, so many years later, reminding you of the day he came traveling back to Boston, having lost thirty pounds that he didn't have to lose, giant smile on that skeletal, handsome face.

What are your youthful companions going to do when they are the age you are now, without boxes of handwritten letters to sift through?

"I'm going to be Amish when I grow up."

Is this what she means, by being Amish? Does being Amish mean having boxes of handwritten letters to sift through? Touch me, the poet says, remind me who I am.