Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 17

May 8, 2025

Immersive Interiority: How to Collapse Narrative Distance to Get Emotion on the Page

Photo by Aidan Roof

Photo by Aidan RoofToday’s post is by author and book coach Alex Van Tol.

Want to create a journey that resonates on a deep emotional level with your audience? That’s something only your characters can accomplish. Emotion doesn’t arise from plot alone; it stems from the people who inhabit your story.

To bring the reader right into your characters’ experience, you need to collapse narrative distance. A few simple language shifts can take your reader from watching people on the page to feeling like they’re right inside the scene.

This suspension of reality—this total immersion in a character’s experience—is what makes videogames so compelling and addictive. But capturing immersion-level interiority is trickier to do on paper. You don’t have sound and lights and colors and haptic feedback. You don’t have feedback mechanisms like damage indicators and health bars.

You have…words.

But as Margaret Atwood says, “A word after a word after a word is power.”

Here, I’m going to use concrete before-and-after examples for three different emotional states to teach you how to collapse narrative distance so your reader forgets they’re just reading, and instead feels like they’re inside the story.

Example 1: GriefBefore: Maria walked through the empty house, aware of how silent it was. She remembered when it had been full of life, the sound of laughter echoing in the halls. Now, it felt like a shell of what it once was. She knew she should feel something, but all she could muster was a vague sense of loss.

After: Maria’s footsteps echoed in the empty house. Too quiet. Too still. Laughter had once tumbled down these halls, warm and full. Now, only dust remained. She paused, her hand on the balustrade that looked out over the grand entranceway. Shouldn’t she feel more? But all that sat in her chest was a hollow ache, like a memory she couldn’t quite touch.

What changed?

We moved from telling to showing. Instead of stating that Maria was “aware of how silent it was,” we’ve made the silence tangible with echoing footsteps, paired with Maria’s interiority: “Too quiet. Too still.”We’ve eliminated filter words. Phrases like “she knew” or “she remembered” create distance. These pop the reader out of the immersive experience, reminding them that they’re just reading a story. Instead, in the “after” example, Maria’s emotions are right on the page: She pauses, looking around a home that once bristled with activity…and we can feel the bereftness of it all.Sensory details make the story feel more real. The reader sees the dust—and I don’t know about you, but when I read that, I can smell the dustiness of the place, too. “Laughter had once tumbled down these halls, warm and full” is more vivid and tangible than “She remembered when it had been full of life.”Maria’s thoughts feel more true to life. The question “Shouldn’t she feel more?” and the description of the ache bring the reader directly into Maria’s emotional state. This makes her relatable—a core requirement of creating three-dimensional characters.These subtle shifts immerse the reader in the protagonist’s experience, rather than making them feel like an outside observer. We can feel the loneliness of the house; we can hear the way it once bustled with life; we can feel the ache inside Maria’s heart.

Example 2: RegretBefore: James sat on the bench and watched the sun set behind the hills. He thought about how quickly things had changed over the past few months. He felt uncertain about what came next and wondered whether he had made the right decisions.

After: The bench was cold beneath James, but he didn’t move. The sun dipped low behind the hills—too fast, just like everything else lately. Four months ago, he’d been sure. Now? Every choice felt like stepping off a cliff in the dark. Had he screwed it all up? Maybe. Probably.

What changed?

James’s internal thoughts are rendered directly. We’ve done away with distancing verbs like thought, felt and wondered. Again, these filter words take the reader out of the story and remind them that they’re just reading. We also get a nice sense of his inner experience with the words “too fast, just like everything else lately.” This signifies to the reader that James’s life feels out of control without being told as much.We’ve used sensory detail. “The bench was cold beneath James” brings the reader into the character’s body. This fires up the reader’s neural loop of what a cold bench feels like to sit on. Brr! Nobody likes that feeling. The fact that James doesn’t try to make himself more comfortable helps the reader understand the depth of his upset.James’s thoughts sound more natural. Humans don’t tend to think in complete sentences, so your characters shouldn’t either. The fragmented sentence structure and rhetorical questions of the “after” passage more closely mimic natural thought and emotion.We’ve made the verbs work harder, and sharpened the emotional tone. Stronger verbs like “stepping off a cliff” and a more realistic emotional tone (“Had he screwed it all up?”) evoke regret, uncertainty and doubt without stating it outright. I particularly love the Maybe. Probably. That’s much closer to how our brains think, especially when we’re beginning to catastrophize.The tweaks we’ve made here let the reader experience the moment as if they’re in James’s body, actually having his experience, not just reading about him from afar. His regret and uncertainty feel palpable here. With these few shifts, James becomes more authentic and multi-dimensional, and we can see more layers of his personality. We’re struggling with his internal conflict right alongside him.

Example 3: AnxietyBefore: Elena walked into the conference room and noticed that everyone was already seated. She felt nervous as she realized all eyes were on her. She reminded herself to stay calm and tried to act confident, even though her hands were trembling slightly.

After: Everyone was already seated when Elena pushed open the door. Eyes turned. Her pulse kicked. Too late to back out now. She straightened her spine, nodded like she belonged here. Her hand trembled on the doorknob and she stilled it, closing the door behind her.

What changed?

Those filter words again! We’ve ditched she noticed, she felt and she reminded herself. These create separation between the reader and Elena, forcing us to simply watch her as she goes through the motions. Way better to just have Elena see that everybody’s seated and feel her pulse kick. The reader gets to experience those sensations in live action.We’ve used physical sensation to show her stress. “Her pulse kicked” does a better job of showing Elena’s fear than “She felt nervous”. Just like all of us know how a cold bench feels under our bum, we also know exactly what it feels like when our heart gives off one of those super-hard beats that signify panic. And her trembling hand underlines her nervousness.We can hear Elena’s internal voice. “Too late to back out now” expresses her emotion from the inside, without even using a single emotion word. The reader understands that Elena is going to COMMIT, dammit, even though she hates this moment. This fires up our preexisting neural circuit about what it feels like to make a presentation to an unreceptive audience. With that, the pulse kick and the trembling hand, we know exactly how she’s feeling.Shorter, more immediate sentences signify stress. “Eyes turned. Her pulse kicked. Too late to back out now.” These are what we call staccato sentences, and they’re super powerful when you stack them up like this. Short sentences like these create a sense of urgency, like a train clackety-clacketing straight toward you, which intensifies the anxiety the character is feeling.Each sentence in the “after” passage pulls the reader closer. We’re not just watching Elena as she enters the room; we are Elena, feeling the weight of those stares and noticing how shaky her body feels. We also get to have the experience of rallying in the face of fear. We sense her determination with the straightening of her spine, and her commitment and courage in the moment she closes the door.

Bonus: Somatic experiencing at the level of your charactersTo get my characters to feel alive, I step right inside their bodies. I picture this sort of like how a ghost might slip inside someone’s skin. The idea is to get into your body and actually BE that character.

Let’s break down how this is done.

Close your eyes and put yourself in the scene you’re building. Feel the ground beneath your feet. Drop your breath into your belly and get centered in a sense of being present in this scene. Use your breath in real life to keep you grounded in this place.Once you’re inside your character’s body, you can experience the world on the same plane—at the same visual level. This is important. Too often, writers stay up at the bird’s-eye view.Take a breath. Notice any smells in that place.Keep your eyes closed, both in real life and in the scene. What can you hear? Is there a bird? A baby crying? Noise from passing cars that’s muffled by the closed window? Which direction is that running water coming from?Keep your eyes closed. Can you feel anything? What are your feet touching? Woolly sheepskin slippers? Cool tiles? What’s your heart doing? Is the sun hot on the back of your neck? Is the scotch tape dispenser in your hand biting into your palm because you’re gripping it so hard? Does your hip ache?Now open your eyes in the scene (keep them closed IRL). What do you see? There are probably 100 different things in your field of vision, and you could focus on any one of them if you wanted to. Which of them is salient to what’s going on in this character’s experience right now? Just notice.Turn your head to the right. What’s over that way? Turn your head to the left. What about that direction? What movement are you picking up on in your environment? What can you just make out in the periphery of your vision?If you’re in the middle of a heated conversation, notice the expression on your conversation partner’s face. Take in their body language: their posture, their degree of ease or unease, the pitch of their voice. What can you tell they’re feeling that they aren’t actually saying out loud? How do you know?As your character, feel around inside your own psyche for a second. You know what your issues are. What part of yourself are you projecting onto your conversation partner in this exchange? Because you know for sure your own bullshit can’t be very far away, right? This is a character-driven story, after all. What are you making it mean about you? And what are you going to do about it?This last part is the gold. To get to the richness in any scene, you need to discern what the situation means to your protagonist. This is all “story” is: the meaning we assign to things. It’s true for you in the real world, and it’s equally true for your characters.

Now bring that gold back with you, out of your somatic experience and back into your writing world, where your hands are poised over the keyboard. As you practice and become more skilled in this embodying exercise, you’ll write better, deeper, more heartfelt and emotionally compelling characters.

May 7, 2025

New agent at SteelWorks Literary

Julie Romeis Sanders was previously an editor at Bloomsbury Children’s.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Here's what subscribers get:

Access to more than 3,000 premium articles on this site, all searchableIndustry news that includes Jane’s reporting and analysis, sent via email once a wekAccess to Jane’s private resource guides, continually updatedLogin below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

New agent at Spencerhill

Renee Runge has joined Spencerhill and seeks middle-grade and YA.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Here's what subscribers get:

Access to more than 3,000 premium articles on this site, all searchableIndustry news that includes Jane’s reporting and analysis, sent via email once a wekAccess to Jane’s private resource guides, continually updatedLogin below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

New Simon & Schuster UK award for unpublished authors of color

Entrants must be a resident of Great Britain and be able to qualify themselves as coming from a minority ethnic background.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Here's what subscribers get:

Access to more than 3,000 premium articles on this site, all searchableIndustry news that includes Jane’s reporting and analysis, sent via email once a wekAccess to Jane’s private resource guides, continually updatedLogin below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

Authors Equity partners with German new adult romance imprint

Starting this fall, Authors Equity will bring a number of bestselling LYX Books to North American readers on an expedited schedule.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Here's what subscribers get:

Access to more than 3,000 premium articles on this site, all searchableIndustry news that includes Jane’s reporting and analysis, sent via email once a wekAccess to Jane’s private resource guides, continually updatedLogin below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

Links of Interest: May 7, 2025

The latest in AI, traditional publishing, culture & politics, bookselling, and trends.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Here's what subscribers get:

Access to more than 3,000 premium articles on this site, all searchableIndustry news that includes Jane’s reporting and analysis, sent via email once a wekAccess to Jane’s private resource guides, continually updatedLogin below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

Username or E-mail Password * function mepr_base64_decode(encodedData) { var decodeUTF8string = function(str) { // Going backwards: from bytestream, to percent-encoding, to original string. return decodeURIComponent(str.split('').map(function(c) { return '%' + ('00' + c.charCodeAt(0).toString(16)).slice(-2) }).join('')) } if (typeof window !== 'undefined') { if (typeof window.atob !== 'undefined') { return decodeUTF8string(window.atob(encodedData)) } } else { return new Buffer(encodedData, 'base64').toString('utf-8') } var b64 = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/=' var o1 var o2 var o3 var h1 var h2 var h3 var h4 var bits var i = 0 var ac = 0 var dec = '' var tmpArr = [] if (!encodedData) { return encodedData } encodedData += '' do { // unpack four hexets into three octets using index points in b64 h1 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h2 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h3 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) h4 = b64.indexOf(encodedData.charAt(i++)) bits = h1 << 18 | h2 << 12 | h3 << 6 | h4 o1 = bits >> 16 & 0xff o2 = bits >> 8 & 0xff o3 = bits & 0xff if (h3 === 64) { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1) } else if (h4 === 64) { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1, o2) } else { tmpArr[ac++] = String.fromCharCode(o1, o2, o3) } } while (i < encodedData.length) dec = tmpArr.join('') return decodeUTF8string(dec.replace(/\0+$/, '')) } jQuery(document).ready(function() { document.getElementById("meprmath_captcha-681c5bbc7322b").innerHTML=mepr_base64_decode("OSArIDUgZXF1YWxzPw=="); }); Remember Me Forgot PasswordMay 6, 2025

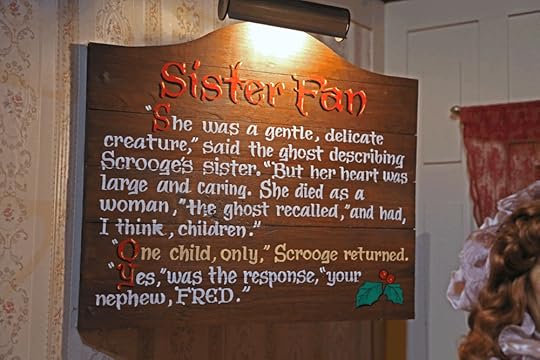

An Argument for Why The Christmas Carol Is Really a Coming-of-Age Story

“Sister Fan” by Jim, the Photographer is licensed under CC BY 2.0 [image error][image error].

“Sister Fan” by Jim, the Photographer is licensed under CC BY 2.0 [image error][image error].Today’s post is by author, filmmaker, and coach Colleen Patrick.

True or false: Ebenezer Scrooge changes who he is at the end of Charles Dickens’ immortal classic, A Christmas Carol.

When I begin my writing seminars with this challenge, a wave of hands flies up when I ask, “True?”

The eager group becomes self-righteously still, arms crossed, for, “False?”

When I proclaim the premise false, a disbelieving cacophony ensues. “That’s crazy!” “Of course he changed!” “No way!” “He completely transformed!”

Before desks can be overturned, notebooks thrown, pencils broken, and the otherwise docile writers trip over one other, desperate to escape and demand a refund, I explain.

My belief is that Scrooge became who he really is—or was, inside, all along. But he was too terrified to face his past because of the emotional wounds and turmoil he was dealt in childhood.

Dickens’ Christmas treatise is the gold standard for understanding human psychology, far ahead of its time. As serious as the subject is, he chose to tell his story using a whimsical writing style, no doubt to lower our resistance to deal with these serious, mysterious ordeals.

Before I deconstruct Ebenezer’s literary journey to prove my case, let’s gain some insights about the preeminent authority of A Christmas Carol: Charles Dickens.

In autumn 1843, Dickens’ funds were depleted, his career careening with poor sales of his latest episodic, The Life and Times of Martin Chuzzlewit. Desperate to excite readers again and please his bankers, he decided to write a full book with a Christmas theme. He had just begun dabbling with the world of spirits and poltergeists, so he began writing the ghostly A Christmas Carol October 14, 1843. It was released just two months later, on December 19. He wrote it so quickly he was not entirely happy with the published work—which, in only a matter of days, became the bestselling book in all of 1843.

In fact, the book’s phenomenal popularity, as well as its many iterations, continues nearly 200 years after its initial release.

I contend its audience magnetism derives from Dickens’ character structure for Scrooge. After dramatizing how the world sees Ebenezer, and how he experiences the world, Dickens takes us more deeply into the mind and heart of Scrooge than we’d normally be allowed any male character at that time.

It’s an inside job. Everything and everyone he grapples with emanates from his mind, his gut, his heart, his imagination. The ghost of Marley and the Spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Future appear from his inner tumult, feelings he has been fighting to mute for so many years. His dilemmas become like a large balloon he strives to hold underwater—which, as we all know, is impossible. He tries to dismiss them, because, after all, they just might be conjured from “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato.”

No. They’re created from his inner upheaval, facing his woulda, coulda, shoulda life. Reflection is not Ebenezer’s strong point. He reluctantly scuffles, parries and thrusts with Marley, the Christmas Spirits and every bombshell revelation he encounters on his journey of self-discovery, each one creating more conflict and epiphanies to pull the story forward.

The inciting incident is not Bob Cratchit’s sad Tiny Tim story or Marley’s terrifying apparition or a pair of do-gooder business peers seeking donations for the poor. It’s his full of Christmas cheer adult nephew, Fred, who intrudes at Scrooge’s place of business, disgusting the “Bah! Humbug!” miser.

Scrooge ridicules Fred’s ebullient Christmas demeanor and dismisses him, burying the pain he carries from seeing his nephew under any circumstance. The reason: Scrooge blames his nephew for the death of the only person who ever loved Ebenezer unconditionally—his sister, Fan. She died giving birth to Fred. Incidentally, Dickens had a sister named Fan.

We get to know characters by the way they react to whatever or whoever confronts them. Our attention remains rapt when we discover how characters respond: what they’re feeling, what they’re thinking. Being literary sleuths, we want to solve this mystery—what makes Scrooge behave so badly? How can he be redeemed?

Dickens uses conversation—inner monologues from Scrooge and dialogue with interlopers—to show us what he’s thinking, remembering, and feeling. Each new character forces him to react—to deal with feelings and memories he believed long sealed away.

Compliments of the Ghost of Christmas Past, Scrooge sees the school and pals that made him so happy, he can’t help but clap his hands and laugh. Then he sees himself—broken-hearted, though putting on a brave face for his peers, left to suffer Christmas alone in his room as they happily leave to enjoy the holidays with their families. Scrooge weeps openly, recalling the pain he locked in.

This is followed by the joy of his younger sister, Fan, surprising him. She has arranged to take him home for Christmas. She reaches up to hug her taller brother, proclaiming their father is so much kinder and happier now. Scrooge is overwhelmed with gratitude. Fan’s loving, generous, kind older brother was rewarded with her appreciation, affection and protection; he’s thrilled.

CUT TO: Fan, the adult, giving birth to Fred, her last words beseeching Scrooge to watch over her baby. Scrooge again weeps openly as he witnesses the only person who ever loved him unconditionally slipping away from her life. And his. Because of that baby. Fred.

I maintain that without these early scenes, we would never believe in Scrooge’s redemption on Christmas day. This is who the guy really is. But, like many who experience a severe trauma, he becomes emotionally stuck. He locks out the possibility of love because even the thought of its loss is too excruciating to bear.

Without proper guidance or therapy, kids who are raised in out-of-control environments tend to be controlling adults. Scrooge found what he could control—business and money. Money that never bought him happiness, but power and control are always for sale.

Later, despite a lovely young woman who wanted to marry him, Scrooge prioritized peer approval, privilege, and profit. He recalls his first boss, Mr. Fezziwig, who threw wonderful Christmas parties and gave generous bonuses. He relives being disrespectful to Mr. Fezziwig, which, in hindsight, he regrets. A mature breakthrough: expressed empathy. Now Scrooge is open to receiving new life information about what he’s previously missed because of his emotional blinders.

Thanks to the Ghost of Christmas Present, Scrooge becomes swept up in the heady bliss of the season he celebrated years ago, passing by new toys in shop windows, then experiencing the joy of an invisible visit to the poor, but loving, Cratchit family. While Bob Cratchit did not disparage his boss at their meager Christmas goose dinner, his wife does—loudly, sparing no insults.

Scrooge’s empathy expands once more to wonder after the sickly Tiny Tim. The Ghost grimly informs Scrooge that without proper care, the diminutive child who walks with a crutch will die. Scrooge is stricken. Concerned. For the first time we see him care about something—someone—more deeply than business, money or being on the lookout for someone looking to cheat him.

The Ghost of Christmas Future shows Scrooge that when he dies, he will reap what he has sown. Those left behind are near celebratory—ridiculing his death, stealing his burial clothes and jewelry, they would have taken his teeth if they had access.

But unlike before his nocturnal Spirits’ reckoning, his attention remains on the Cratchits and sickly Tiny Tim, and his unkept vow to his dear Fan—to watch over Fred.

Arising Christmas morning, he is on fire with the Spirit of Christmas. He has a life to live! To give! Everything good he felt as a boy is now alive and energized in his aging body—whose spine is again straightened, not curved and bent over like an old man. What thrilled him at Christmas as a boy has come full circle. It’s once again alive in him now as an adult.

Radiating the ebullience of the season, he sets out to make amends to his nephew, bring gifts and a turkey to the Cratchits so they might all share a genuinely Merry Christmas, complete with a pay raise for Bob and a position for his older son.

Scrooge chose to live in gratitude rather than anger at what he doesn’t have or what he believed was taken from him. Thus, the elder Ebenezer Scrooge becomes the person he had locked inside most of his life, maturing with every revelation along the way. A true coming-of-age story.

Because Dickens took us on this journey, first showing us the outside world of Scrooge, how others react to him negatively, then taking us through the inner sanctum of Scrooge’s mind, we are hooked, possibly discovering the Scrooge inside us, wishing we could also find a similar redemption. I mean, after all, if Ebenezer Scrooge can do it…

I’d be remiss not to mention Dickens’ focus on life and death. Or rather, early on, Scrooge’s fear of death, and later, living a full life, having no fear of death.

The book starts out by declaring Marley is as dead as a door nail. Buried. Gone. Just like Ebenezer’s feelings and wounded memories. When Marley appears as an apparition, Scrooge is terrified. Of death. Of the ghost’s message. Near the end, he’s fearful of his own passing. But when he reclaims the youthful bliss of living out loud, giving, sharing, loving, then joining his nephew (his birth family (and then the Cratchits (his chosen family), his fear of death vanishes.

In one night’s drama, Dickens has brought us through a personal evolution many of us have spent years in therapy, self-help books and “personal growth” seminars trying to achieve.

I declare to my students: No matter how old the body, it’s never too late! Scrooge’s is a coming-of-age story.

May 1, 2025

Building Devices That Drive Story Suspense

Today’s post is by author Janee’ Butterfield.

Let’s be honest—writer’s block is frustrating. It creeps in when you least expect it and can make even the most dedicated writer feel like they’ve run out of ideas. For thriller writers, the pressure can feel even heavier. You’re not just trying to write—you’re trying to shock, grip, twist, and terrify.

But here’s the secret: you don’t always need a plot to start writing. You need a trigger. And sometimes that trigger is a single object.

Building devices that drive suspenseWhen I’m stuck creatively, I don’t stare at a blank page and wait for a plot twist to materialize. I start with a device—something strange, eerie, or dangerous. A tool, object, or mechanism that instantly creates unease. From there, the story starts to grow.

In my debut novel Caught in Cryptic, I built the plot around a pair of yellow-tinted glasses. These weren’t your average retro shades. They had tiny windshield wipers that scraped back and forth across the lenses, creating a bizarre and unsettling effect. But their real horror came from what they did: if the wearer disobeyed a certain rule, the glasses would activate a timed chemical agent that burned through the eyes. It was psychological torment with a built-in countdown.

The sequel, Falling Cryptic, expanded that idea with virtual reality glasses that trapped users inside manipulated memories, making it nearly impossible to tell reality from illusion. Both sets of devices served one core function: raise the stakes, distort control, and force my characters into impossible decisions.

The right device doesn’t just add suspense—it becomes the engine of the story.

Why devices workThere’s something primal about the fear of being trapped, controlled, or helpless in the face of an object you don’t fully understand. Devices tap into that.

Here are a few iconic examples that inspired me and perfectly illustrate this concept:

The Ring (2002): A cursed VHS tape kills anyone who watches it within seven days. It’s simple, tangible, and terrifying. The moment the characters hit “play,” the countdown begins. The tape isn’t just a prop—it’s the core of the horror.Saw’s Reverse Bear Trap: This device does more than threaten physical destruction. It represents the larger moral dilemma of the series: how far are you willing to go to survive? Its visceral design and time pressure create immediate dread.Stephen King’s Christine: A 1958 Plymouth Fury with a mind of its own. It seduces, possesses, and kills. Christine is both a character and a device—one that transforms the mundane (a car) into something monstrous.What makes these examples unforgettable isn’t the object itself—it’s the rules tied to them. The countdown. The punishment. The helplessness. It’s the stakes.

Tech meets terrorI work in the tech industry full time and write thrillers on the side, so technology naturally shapes the way I think about suspense. In Caught in Cryptic and Falling Cryptic, I used devices like yellow-tinted glasses that punished disobedience and virtual reality tools that manipulated memory. My newest book, Nighty Night, Dear, introduces the Dream Catcher—a device that turns sleep into a weapon. I’m especially drawn to tools that act like subconscious conditioning—tech that controls behavior in subtle, disturbing ways.

For me, the goal is to make these devices feel possible—grounded in logic, but just eerie enough to keep you up at night.

I always ask myself:

What fear does this device tap into?What are the consequences of its misuse?How does it reflect a deeper emotional or societal truth?Because at the heart of a great device is more than function—it’s a motive. Something the reader can recognize and fear in their own lives.

Literary lifelinesSome of my favorite authors also inspire this approach. Freida McFadden’s psychological thrillers have taught me how to weaponize the ordinary. Jeneva Rose’s clever twists remind me to keep readers guessing. Mia Sheridan’s emotionally rich storytelling challenges me to add heart even to horror.

Each of them, in their own way, builds tension not just through plot but through things—notes, recordings, tech, locked rooms, broken phones. Tangible items that change the game.

Start smallIf you’re staring at a blank page, don’t force the plot. Start with the device.

Ask yourself: what object could you place in a room that would shift the atmosphere? What’s the rule attached to it? What happens if someone breaks that rule?

Sometimes the key to moving forward isn’t inventing a new plot—it’s finding the one thing that breaks your character’s sense of safety.

For me, it started with a man at a ballpark wearing yellow-tinted glasses. Something about him gave me chills. Years later, those glasses became the seed for my first thriller. And every book since has been a search for the next eerie mechanism.

Ideas aren’t magic. They’re built—one creepy object at a time.

April 30, 2025

New agents at Wave Literary

Bethany Saltman and Jessica Larios-Zarate have joined Wave Literary, a full-service literary agency.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

New Adult Book Prize in the UK

The Bookseller has announced a new award for the fiction category of new adult, which focuses on the transitional years after young adulthood.

This premium article is available to paid subscribers of Jane's newsletter. Login below, or learn more and subscribe.

Wondering why some content isn't free? Did something change? Here's an explanation.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1885 followers