Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 135

February 22, 2016

Pinterest for Authors: A Beginner’s Guide

Photo by Bunches and Bits {Karina}

Today’s guest post is by author Kirsten Oliphant (@kikimojo).

Every few months another social platform emerges and I can almost hear a collective groan: “ANOTHER platform? Really?”

Finding the balance between actual writing and all the online promotion is a real struggle for writers. Lately I’ve heard many voices saying that writers need to be on Pinterest. With all the platforms to choose from, is Pinterest really an effective platform for writers?

This is, of course, a trick question. A better question (and one for any platform) is: Can Pinterest help you reach your goals?

I will give you four reasons you might want to use Pinterest, share ideas for using the platform, and give some best practices to get the most traction on the Pinterest.

4 Reasons Writers Should Use Pinterest

1. Traffic. Every social media site sends different kinds of traffic. Twitter typically sends a drop here and there. Facebook can send a surge that lasts a few days if a post is really shareable. Pinterest has legs and loves to run marathons, not sprints.

When I look at my page views from the last year on my lifestyle blog, Pinterest is by far my top referrer, sending me hundreds of page views a day on posts I wrote (and pinned) months before. This means that even if I take the month off (which I did last summer), I can still retain 20,000–30,000 page views per month from pins that are mostly a year old. The residual effect of Pinterest traffic can beat out any other platform and send you readers on autopilot.

The downside: Traffic from Pinterest does not always bring good readers who want to sit and stay. There is often a correlation between high bounce rate and Pinterest traffic. (My bounce rate for readers coming from Pinterest is much higher than those coming from Facebook, for example. Facebook readers also tend to read more pages.) To combat this, give readers a reason to stick around with great content, a blog that’s easy to navigate, and a clear sign up for your email list.

Note: My lifestyle blog from which I took those numbers is NOT about writing. Most of the traffic comes from food and DIY pins. The numbers I share are not the point, but more the fact that the traffic from Pinterest comes steadily rather than in spurts when you share, as it tends to work on the other platforms. Pins take on a life of their own and keep sending you referrals.

2. Un-Social Network. Unlike other platforms that are all about connecting, Pinterest is not super social. This means you can be more businesslike about your time there. On Twitter or Facebook, if you aren’t engaging, you might turn people off. On Pinterest, no one cares if you comment or interact. It utilizes an algorithm like Facebook, so if you decide to pin twenty things in ten minutes, it won’t clutter up your followers’ home feed. You can get in, do some pinning, and get out.

For those of us overwhelmed by conversations and connections, Pinterest is a refreshing platform. You can spend hours (or minutes) looking at pretty things and not have to talk to another human. It is an introvert’s dream: a social platform where you don’t have to be social to be successful. This also means that it’s really easy to get started with Pinterest as compared to other platforms.

The downside: If you want to form collaborative relationships, this is not the best place to do it. Good thing we have 200 other platforms for that!

3. Search. Pinterest has refined its search feature so that you can potentially find great pins (and have your pins found) through keywords. Many Pinterest users will actually go to Pinterest for search rather than Google.

Google, in turn, will show pins in search results. This means that your site can rise in Google rankings by doing well on Pinterest.

The downside: I don’t see one, do you?

4. Easy Buying. Pinterest has integrated buy buttons directly onto pins. This is only available to a select few, but you can join the waitlist to find out when this rolls out to the general public. This would mean that your followers could click to buy directly from Pinterest. I can see how this would be a fantastic selling tool for authors.

The downside: This is in beta and only available for big brands…so far.

How Writers Can Utilize Pinterest

1. As a writer writing about writing. Many authors have a successful book or two, then turn that into a platform telling writers how to have successful books. Teaching people how to write, market, or publish a book is actionable and meets a need. Whether we are talking Pinterest or in general, this kind of content will almost always win out over simple book marketing because it solves a problem.

These kinds of pins do well on Pinterest. You can write about all aspects of writing as well as social media and platform building. People come to Pinterest to learn something, whether that something is baking the best chocolate brownie or writing a bestseller. They also come for the great visual aesthetic, which is why you will want to master pin-worthy images (more on this in the best practices section).

2. As a writer simply writing. If you do not have an author platform built on teaching people how to write, Pinterest may not work as effectively as it would for those solving a problem. But the platform can be a great tool for your research and planning. The added bonus is that it provides that peek behind the curtain many fans love. It’s like sharing an intimate view of your planning process for your readers.

In addition to a board for your published books, you can create boards related to various characters or pin images related to your book’s setting. Pin inspiration books or quotes related to writing. You can share pins related to writing even if you don’t create that kind of content on your own blog.

If you like the visual appeal of Pinterest, it can be a great place for inspiration and to allow readers to connect with your process.

Pinterest Best Practices

Let me warn (and encourage) you: the setup to use Pinterest has a lot of steps. I imagine your eyes glazing over as you read. If you feel overwhelmed, let me assure you that these are all very easy steps and I’m linking to the simplest tutorials. It may take one hour total to optimize your Pinterest profile and your site. If you need to take things in batches, do that.

Pinterest is super easy to use once you get a few things in order. Bookmark (or pin) this post so you can come back with a cup of coffee or glass of wine to see you through the techie bits.

The Basic Setup

1. Use a business account. To use Pinterest effectively, you want to use a business account, not a personal one. That sounds fancy, but it makes virtually no difference on how your account looks. The business account provides free analytics, which you can use to see which pins are working well for you. It also get access to all the business tools so you can embed pins and boards right into blog posts or in your sidebar, which is great for growing your Pinterest following.

2. Write a great profile description. As with most platforms, you want to use great keywords, but have some personality in your profile. Because Pinterest is functioning more as a search engine now, use keywords related to your topics as well as great descriptions.

3. Create themed boards. Have at least one for your own content (possibly two: blog & books). I’ll give more tips for boards, but you can have boards related to your novel research, boards centered around writing tips, and boards related to personal interests. Don’t feel like you have to be consistent across all boards. It’s totally fine on Pinterest to have boards related to the best hamburgers and also writing tips. As with your profile, use keywords in the board descriptions.

4. Prominently feature a board for your blog & books. Depending on how much content you have, you may want to separate these. But your first board should be a board that is all of your content. You can use the name of your blog or use a name that is more searchable in keywords, but your top board should be all your content.

Your Website or Blog Setup

1. Get verified. This simply means that your site is officially connected to Pinterest. This allows you to see analytics of who is pinning what from your site. Here is a great tutorial on getting verified.

2. Get rich pins. This is the lovely branding and highlighted blog name underneath the image of certain pins. It is not hard to get rich pins if you are using WordPress and have the Yoast SEO for WordPress plugin. (See this tutorial for WordPress.) Rich pins make your pins stand out and give the audience confidence that pins from your site don’t lead somewhere spammy.

3. Install the Pin It Button. Having a Pin It button on each image ups the likelihood that other people will pin from your site. It’s great to have social share buttons at the top or bottom of each post, but this button maximizes the sharing from every image.This is the third (and last) technical bit and if your eyes are beginning to glaze over, you’re almost through! Follow this tutorial.

Now that you have the basics set up, you want to operate with a Pinterest mindset. Here are ways that you can get the most mileage out of the platform.

Optimize Your Post Images

Take deep breaths if you are not an image person. You can do this! Here are the important aspects to creating pinnable posts:

1. Use a vertical image. Try 736 (wide) x 1104-2477 (tall). If you don’t like super tall images, you can hide one in your post that will appear when people use the Pin It button in their dashboard. See this helpful tutorial from Pinch of Yum. (More on sizing HERE.) I personally always use 800 x 1200 on my blog and they look fine. If you don’t like the way vertical images look in your blog post, see this tutorial on hiding those images unless someone is pinning from your post.

2. Write a great description with keywords in the alt tag section of each image. When people click to pin, the alt tag will show up as the pin description. Write an inviting, keyword-rich description. Check out this helpful tutorial on writing a perfect pin description. If you don’t know where an alt tag is, you can find it when you edit a photo in WordPress or blogger.

3. Be consistent. Pick a few fonts and a style that you can keep. Spend some time on Pinterest looking at what pins stand out to you. One of the best examples of a writer with great pins is Kristen Kieffer from She’s Novel. In this screenshot you can see her old and newer style and how they all still fit together consistently. She has amassed a very large following in a relatively short time by creating great content and effectively utilizing platforms like Pinterest.

4. Visit Pinterest to see what kinds of images stand out to you. Use a free tool like Picmonkey or Canva and free stock photos on Pixabay. Watch this brief tutorial on Picmonkey to see how you can do this.

Be Active Daily

Pinterest can be an easy place to get lost. Set a timer and give yourself a few times a day to pop in and repin things you love, search and repin in your categories, or to pin your own content. Pinterest is fast and easy with less interaction, so you can pop in and pin a few things a few times a day. Do not just pin your own content, but pin from your home feed and utilize the search function.

If you prefer scheduling, try Ahalogy (free), Viral Tag (paid), Tailwind (paid), or Board Booster (paid). If this is a challenge, the Pinterest app functions well on mobile. Make it a point once or twice a day to pop it open and do some pinning.

Use Secret Boards

Your readers and raving fans may actually care about the kind of food you like, so having a few boards unrelated to your work is totally fine. Arrange your boards by relevance, keeping your content as the first few boards and moving less related ones to the bottom. (To do this, click on the Boards section of your profile and drag them in the order you want.)

If you have a few things that are totally off the wall, keep a secret board. As an example, I have a secret exercise board. Not because I want to hide the fact that I work out, but because the visuals for these pins (mostly sweaty women in sports bras) don’t jive with my overall brand.

Join Group Boards

Group boards bring together multiple pinners for a larger reach. Each group board has its own rules, usually written in the description of the board. You can search through Pin Groupie to find boards in your niche and even see how many followers they have or the general activity level. Be sure to follow the rules on group boards!

You can also create your own. I searched for “writing” and “writers” on Pinterest to find the pinners with the best visual pins. I invited them to pin on the Epic Writing Life board, requiring great visual pins and great content.

If you want to get started with a group board, I’m happy to invite you to my collaborative board, The Art of Writing, with 2,900 followers. Not huge, but it may give you a boost if you’re just starting out. Find the board here and follow the instructions to request an invite.

Do you think Pinterest could work for you, either as a tool or as a traffic-driver? Are you already finding success from Pinterest? Leave a comment below to share your thoughts about this visual platform.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, I recommend checking out Kirsten’s free monthly coaching calls.

February 16, 2016

How to Find and Work With a Book Publicist—Successfully

Boston Public Library

This past weekend, I had the honor of speaking at the San Francisco Writers Conference. While attending, I sat in on two sessions focusing on book publicity, with panelists Penny Sansevieri, Andrea Dunlop, and Natalie Obando (all publicists or marketing consultants).

Because marketing and publicity help is the most common request I receive, I was very interested in hearing advice from these publicists about what authors can expect from a professional firm and how the process works. What follows is a summary of their comments from both panels.

First: Understand the Right Mindset for Working with a Publicist

All panelists agreed that—even though you’re hiring a publicist—all authors have to be willing to learn how to market their book. Good marketing and publicity is a team effort, and the author is part of that team. Each publicist looks for clients willing to do some things on their own, and they also look for authors to be realistic. For example, if an author wants their book to be a movie, most publicists will not be able to meet those expectations if you’re a first-time author with no platform. The panelists seek clients who know marketing and publicity is a process and know that it will take some time to see the effects of an effort. (There are no overnight successes.)

All panelists emphasized the competitive nature of getting traditional media coverage, and the increasingly limited options when it comes to traditional publicity, especially for independently published books. Traditional outlets like print and radio have really shrunk, while at the same time the number of books being published has greatly expanded. So the competition is fierce for a small number of slots. Furthermore, although traditional media coverage feels very good when it happens, it doesn’t necessarily move the needle all on its own. The authors who work best with a publicist are those who understand what they’re up against, but feel positive about how much there is they can do.

Publicity seeks to find, identify, or target the audience to make them aware of your book. Therefore, Obando said, the best authors are those already familiar with their audience and who have aspects of their platform already in place. That way, when you do hire a publicist, the publicist has some starting assets: social media, websites, and other tools that are starting to connect with the book’s target reader.

Publicity seeks to find, identify, or target the audience to make them aware of your book. Therefore, Obando said, the best authors are those already familiar with their audience and who have aspects of their platform already in place. That way, when you do hire a publicist, the publicist has some starting assets: social media, websites, and other tools that are starting to connect with the book’s target reader.

Remember: You’re hiring a partner. A lot of authors tell publicists, “I don’t want to do it.” Yet that’s the job. Of course you can hire people to help you, and you can hire people to do parts of it. Especially in terms of pitching traditional outlets, that’s not something authors probably should do, but it is necessary to look at what you can do.

Does the age of the book matter? Sansevieri’s firm (and others) have worked with authors at all stages—even with books that were two years old. The main requirement for an older book is that it must still be relevant—it can’t be out of date.

How to Build Momentum Before You Hire a Publicist

Andrea Dunlop, who started her career as an in-house publicist at Doubleday and now helps authors with social media, says there’s a lot authors can accomplish on their own using digital media.

Obando recommends that authors learn all the social platforms that their potential or target audience uses. Being well-versed in those different languages of social media really helps—you begin to understand how to effectively reach potential buyers and develop a good idea of who your market is, and what they turn to for entertainment.

Obando recommends that authors learn all the social platforms that their potential or target audience uses. Being well-versed in those different languages of social media really helps—you begin to understand how to effectively reach potential buyers and develop a good idea of who your market is, and what they turn to for entertainment.

To be a good partner and marketer, all panelists discussed the need to understand your audience better than anyone. Even though many books have crossover appeal, you have to decide and focus on your core market. (And yes, one of the big things a publicist does is help you figure out who your audience is.) If you’re focused and clear about your target audience and your objectives in reaching them when you start your marketing/publicity campaign, you have a better chance later of reaching a larger or more national market.

Part of understanding one’s audience is also knowing what authors are your “competition,” or those who reach the audience you should also reach. Dunlop said, “I know we all feel like special snowflakes with our book, but you want your book to be like other books. Otherwise it can be really hard to figure out what the [audience] demographics are.” She recommended Goodreads as a good place to figure out what books are showing up in relation to other books.

Dunlop also encouraged authors to read anything/everything in your genre. When you like the books you read, talk about them on social media and connect with the authors. If possible, befriend those authors, talk about their books on social media, and try to do events with them. They will be your supportive community.

Publicity Cost and Its Payoff

Every publicist works differently—plus there are so many factors that can go into a publicity campaign, so it depends on what you want your publicist to work on the most. Brief consultations or assistance may cost in the hundreds of dollars, while intensive three-month campaigns can easily cost $20,000 and up.

As far as payoff, the overarching answer to this question is that authors should not expect to see each publicity dollar come back to them in the form of book sales.

Dunlop said directly, “There isn’t a one to one. I don’t think that’s the right way to look at that investment.” Furthermore, no publicist can promise or guarantee you specific coverage or sales. Unfortunately, authors get very focused on things they know and understand, like being on the Today show, or getting traditional reviews—and they’re great if you can get them, but you can’t rely on getting them, no matter how much money you throw at it.

Dunlop, aside from working in publicity, also hired a publicity firm to assist with the launch of her novel from Atria this month. She said, “This is an investment in my career; I’m not looking to make back my money in sales in six months. I want a lifelong career as an author. I don’t equate it in a hard way with sales.”

Dunlop, aside from working in publicity, also hired a publicity firm to assist with the launch of her novel from Atria this month. She said, “This is an investment in my career; I’m not looking to make back my money in sales in six months. I want a lifelong career as an author. I don’t equate it in a hard way with sales.”

Obando agreed with Dunlop, and said that publicity is more about getting people to recognize who you are in a world of oversaturation (rather than book sales). Publicity elevates you above the rest of the chatter.

Some authors want to work with marketers by offering them a percentage of book sales, and Sansevieri explained that publicists don’t work that way. First, publicity firms are not set up to track long-term sales. But also, in the majority of cases, publicity is about the long runway of promotion. Sales or publicity hits may happen in those first 90 days of the campaign, but no one knows when it’s going to pop—you’d have to track books for years and years. Performance varies too greatly.

Remember that you’re hiring someone who can see the 30,000-foot strategy of everything that needs to happen. “I just want to sell books” is a terrible metric to live and die by, according to the panelists.

First Steps With a Publicist

Initially, when Sansevieri talks to an author, she asks things like: What are your goals? Is this just about one book—you’ll never publish another? Is it part of a series? Is this book going to be building your business? Then she asks, “What’s your dream—what do you really want?” Her strategy talks are about 30 minutes, and cover where authors want to be and what they want to focus on. She then puts together a proposal that looks at the first 90 days of publicity.

Dunlop tries to meet authors where they are and get a read on how they feel about publicity. A lot of authors are overwhelmed, so she tries to give them concrete marketing steps they can accomplish on their own.

Obando prefer to work with authors as early in the process as possible. She says authors should start thinking about publicity at conception of the idea, and while they’re writing the book. As far as working on a specific campaign, she generally starts three months before the release date. But most authors end up at her door when their book is not selling. By that time, it is a little late in the game—especially for a traditionally published author—but that’s not to say things can’t still happen. Much depends on the book and platform.

The big difference between a publisher’s publicity efforts and a self-publisher’s publicity efforts: Dunlop explained why traditional publishers focus so much on doing publicity around a book’s launch date, within a three-month or six-month window: It’s all because of the bookstore retail model. Publishers are focused on selling as many as possible right after the book goes on sale to avoid returns from bookstores. With self-published books, which aren’t typically distributed in high volume to the bookstore market, there is no pressure to sell to avoid returns, so the timeframe for success stretches over years rather than months. Indie authors don’t have to worry about establishing a solid sales track record right out of the gate; it can be a slow burn.

Keep in mind the publisher’s publicity team is working for the publisher, not you, and while you may have all kinds of great ideas about your marketing and publicity campaign, they’ll first focus on their goals for the book rather than your own. It’s important to communicate early with the in-house publicity team and understand what they have planned, which can help inform your own decision about whether to hire a publicist and what they should focus on.

Dunlop said that when she worked as an in-house publicist, she sometimes saw authors who would pay an outside publicist to do exactly what the in-house publishing team would’ve done on their behalf. So look for an outside publicist who will augment what the in-house publicity will do—which is all about communication. You want to have coordinated outreach so they’re not reaching out to the same people.

For Authors Who Get a Very Late Start

It’s fairly common for authors to end up seeking a publicist or marketing help after their book has already launched and not done well. This sometimes results in panicked authors, who realize they should’ve been developing a plan many months ago, and end up on social media with blatant self-promotional messages that command, “Buy my book!”

Dunlop says authors should try to avoid that panic: You’re going to build your audience by writing multiple books, and your social media efforts are about building community. If you’re an independent author, you don’t have to worry about your sales track record—you can wait and do it better the next time. She says it’s sort of like being on a diet: Forget the past, and adopt good habits moving forward. The book you have now (that isn’t marketed well) is a piece of content that will foster marketing for your next book.

All panelists said that marketing and publicity never really ends—it’s ongoing for as long as the book can or should sell, or for as long as you have an author career.

Regional Marketing: A Good Steppingstone to National Publicity

Sansevieri discussed that, especially for independent authors or those without much of a platform, regional marketing is a good place to start a marketing and publicity campaign. Authors can schedule events or tours in their city or area—not necessarily in bookstores, although that’s perfectly acceptable—but in wine stores or restaurants or libraries, or other nonconventional places. (Be creative.) As much as possible, Sansevieri tries to anchor regional publicity around an event the author is doing.

Sansevieri said that if you’re trying to land national publicity, then you should get media training. Media training is where you sit with a coach, learn how to have key talking points, and get trained to be in front of a camera. You come to understand how quickly the person interviewing you will have to put together the story—meaning, they’re not going to read your book. That means that whenever you deal with the media, you should go in with a cheat sheet for the journalist or interviewer.

For Authors Who Pitch the Media on Their Own

Nobody cares that you wrote a book. Or: Don’t lead with the book. Lead with the hook or the story, what that book will do for people.

The most important thing about your email when pitching is your subject line. Put the hook in the subject line. Keep your pitches short, about a paragraph. A lot of journalists and reviewers are looking at emails on their phones, so keep it succinct, and think about it in terms of a brief elevator pitch.

Most media won’t say “no” to your pitch; they just won’t answer. Sansevieri doesn’t recommend calling because of the pressures of the news cycle; if you do have to call, the first thing you ask should be: “Are you on deadline?” You don’t want to pitch if they’re on deadline.

To learn more from these marketing and publicity experts, visit their websites or follow them on Twitter:

Andrea Dunlop (@andrea_dunlop)

Penny Sansevieri, Author Marketing Experts (@bookgal)

Natalie Obando, Do Good PR (@dogoodprgroup)

For more advice on marketing and publicity:

Simple Tips on Finding and Working with a Publicist

5 Marketing Models for Self-Publishing Success

Book Marketing 101

February 15, 2016

Storytelling Across Media: Q&A with Agent Laurie McLean

Fuse Literary (@FuseLiterary) is one of the more interesting and progressive literary agencies I know, founded by Laurie McLean (@AgentSavant) in 2013 with Gordon Warnock. It blends traditional publishing methods with digital publishing and emerging technologies, plus operates a digital-first publishing division, Short Fuse, to help build their clients’ audience between books.

Just recently, an interesting new deal was announced by the agency: Their client, recording artist Simon Curtis, signed a book deal with Simon Pulse for the YA novel Boy Robot, to release in November of this year. To coincide with the deal announcement, Curtis released an album with songs that inspired the book, and a cover reveal will follow this month.

Laurie McLean agreed to answer a few questions about the unique nature of this client and book deal.

JANE FRIEDMAN: How did Simon Curtis come to be your client—did he find you or vice versa?

LAURIE MCLEAN: Simon and I were actually united by Simon Pulse editor Michael Strother. Michael knew that Fuse Literary had been formed to explore the potential of hybrid authors and storytelling across multiple media. Plus Michael and Simon had been interacting on Twitter for years. Michael was a fan of Simon’s music.

So when Simon mentioned on Twitter that he was working on a YA science fiction novel, Michael jumped in and asked to see it. When Simon Pulse eventually expressed interest in buying the book, Michael reached out to a few select agents, and I was one of them. I convinced Simon that Fuse was a perfect match for his interests and talents, and boy are we enjoying the journey together.

Usually I tell authors that, for fiction deals, platform is rarely as important as story. With this deal, it looks like platform and Simon’s music career played a very strong role. What made this project attractive to you and/or to Simon Pulse?

Fuse Literary is always looking for hybrid authors who have interests outside the book that we can exploit. We have self-published and traditionally published authors, sure. But we also have Joey Coco Diaz, who is a standup comedian, podcaster, and author. We have A.R. Kahler, who is a circus performer, and Ransom Stephens, who is a particle physicist. Both are novelists, and we use their other talents to reach those target readers as well.

Simon’s performing artist celebrity did play a big part in this deal, as did his amazing dominance of Twitter. He has such a strong base of fans on Twitter who not only buy his music, but also interact with each other and Simon to a huge degree. It’s that social media juggernaut action that got everyone interested.

How do you envision the cross-marketing and publicity strategy working—getting people from the music to the book?

Agent Laurie McLean

We intend to keep the music and the books as separate, yet symbiotic, entities. We really want the book to be billed as an amazing YA debut by an exciting new author crafting an entire new universe full of incredibly diverse characters.

At the same time, Simon will be releasing new music and expanding his audience there as much as possible, so that when the time comes the largest number of eyes and ears possible will be on the book. The music will never be “book soundtracks,” per se, but fans of the music will find references in the books, and vice versa.

What does Simon have planned in the build-up to the book’s release day?

In addition to the cover reveal this month, Simon’s also working on new music that should drop immediately before or coinciding with Boy Robot in November. I’m sure there will be YouTube videos, music videos, performances, and more. The book and Simon’s musical vision are very intertwined.

This book will be released by Simon Pulse, an imprint focused on teen fiction. What do you think is different about marketing a debut author to a teen audience?

You have to market to teens where they live, and today’s teen lives online. Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube, and to some extent Twitter and Facebook are where these kids hang out and interact, so that’s where Simon intends to have a big presence. You will still have the gatekeepers—parents, teachers and librarians. But if a teen wants a book, a parent is more than likely to buy them the book they want. To a parent’s mind, a book is much better than yet another video game or app. Storytelling in a book works on immersive imagination, and that makes it special.

February 11, 2016

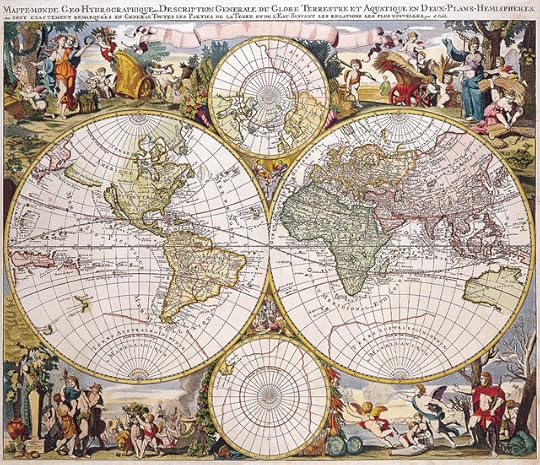

Selling Your Books Internationally

by rosario fiore | via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s post is an excerpt from the newly released How Authors Sell Publishing Rights by Helen Sedwick (@HelenSedwick) and Orna Ross (@OrnaRoss).

When it comes to selling your work overseas, there are two channels:

Licensing your English-language or translation rights to traditional publishers located abroad

Selling your book in English and/or translation directly through online retailers or local distributors.

This second option is providing great opportunities for indie authors. For some books, sales from international licensing dwarfs sales of the original English editions.

For example, David Vann is one of the most accomplished US authors you’ve never heard of. His award-winning works have been translated into nearly twenty languages, and he’s a former Guggenheim Fellow and Stegner Fellow. Even though his books are published by a major publisher, he receives more attention and more sales abroad. He claims he’s sold more copies of his books in Barcelona than in the entire US.

Not long ago, selling rights internationally required a network of agents, publishers, translators, and distributors, and it was almost impossible for independent authors to break into the market. But social media, email, online licensing and retail platforms, and advances in technology have made exploiting international rights easier than ever for all publishers, including author-publishers. Writers can now engage with licensees and readers all over the world without leaving their desks.

Why English Books Have a Leg Up

When it comes to global sales, books in English are at an advantage. English is spoken as a first language by around 375 million people and as a second language by an additional 375 million people. Around 750 million people speak English as a foreign language (where English is not spoken as a first or second language). One out of four of the world’s population speaks English to some level of competence, and demand from the other three-quarters is increasing.

Opportunities to sell rights vary by market, and authors should consider researching foreign rights early in the self-publishing process. “There are some markets, like other English-language markets outside of the US, [where] you might have demands to publish even before you self-publish in the US,” says Seth Dellon of PubMatch.

Licensing and selling books in translation is more complicated. It requires a greater investment of time and money and relies on the creative talents of professional translators.

“It’s important to understand that the translation markets are each as tough to crack as home English-language markets,” says Jennifer Custer, Rights Director at AM Heath. “Translation itself can cost many thousands of dollars/euros, and so publishers have an extra financial dimension to their calculations. Each market comes with its own difficulties, and the economic crisis is biting—trade book sales are down, and publishers are cutting their lists and have less money to invest in translation and marketing.”

No matter which route you take, keep in mind that marketing is key to success. “Marketing your book to readers is really important, but what’s equally important is marketing your book to the industry,” Dellon adds. “Whether that’s rights buyers and publishers around the world, or even librarians and booksellers, there are other groups besides readers that it’s really important to reach.”

However, before you launch your international publishing career, you need to make sure you still hold your international publishing and translation rights.

Do You Own Your International Rights?

Surprisingly, many traditionally and independently published authors do not know the status of their international and translation rights. In fact, when IPR License quizzed a cross-section of published and aspiring authors, they found:

Almost half of authors (47 percent) admitted they did not know or were unsure if they owned the world rights to their book.

Only 13 percent of respondents had licensed their work to an overseas publisher, representing a potentially huge opportunity missed.

28 percent of authors didn’t know when they did or didn’t have rights to license.

Many published writers surveyed are not quite sure if they still own their own world rights or not.

Traditionally published authors need to look carefully at their book contracts to see what they own and what they have licensed away. If you are represented by an agent or attorney, ask for their review and interpretation. And, if considering a trade-publishing contract, always look closely at the rights clauses and consider the rights potential of that particular book or series and your own ability to trade those rights separately.

If you are publishing independently, then check the publishing or services agreement of your self-publishing service company or POD provider. Tom Chalmers, the founder and director of the rights management service IPR License, noted that “authors far too easily just check ‘world rights’—all languages—and pass them over.” If you have signed on with a SPSC that has taken an exclusive, worldwide license to your work in all languages and all formats, then figure out how to terminate that agreement before you launch your book internationally.

Don’t assume no one will care if you start selling your book in France in violation of an existing agreement. If your book is successful, then trust us, they will care.

Should You Grant Your Publisher a License for Your International Rights?

Suppose a traditional publisher wants to license your international publishing rights along with domestic rights. You’re delighted, of course. Surely this demonstrates their faith in your work? Not necessarily—the publisher wants to make sure that if your book sells well, it will control all of the distribution and marketing (and profits) in every country.

There is nothing wrong with granting a trade publisher international and translation rights, so long as the publisher has the wherewithal and intent to exploit those rights successfully. So before you sign these rights away, consider the following:

How big is the publishing house? Size will usually have an impact on its ability to invest in translating and marketing your book.

Does the publisher have the connections in other territories to have your book expertly translated?

What is the publisher’s track record in the international market?

In what format does it intend to circulate your book in each territory? Digital, print, audio, film, others?

What languages? Which countries?

How and when will the license end? Is it forever or only a few years? When will rights and translation revert fully and completely to you?

Do they have a plan for your book, and do they seem intent on pursuing it to the fullest?

You will need to be comfortable with the answers to all of the above before signing.

Selling Foreign Rights Without an Agent

The popular self-publishing guru, Dean Wesley Smith, recommends a DIY approach, cutting out the agent to contact the overseas publishers yourself.

“If your agent in a big agency wants to try to sell your books overseas, they give it to the dedicated foreign agent (who you likely don’t know), who then either shops it or gives it to yet another agent (who you certainly don’t know and didn’t hire). If you want to be an internationally selling fiction writer, take control of this aspect of your career as well as home market. My wife sold her last few books overseas on her own completely from start to end. On another, she sold it but brought her agent in to help with the deal.”

In order to do this, you will need to become an expert in foreign rights, getting to know a wide variety of agents, sub-agents and publishers in a number of territories. Traveling to large international rights fairs at least twice a year (e.g., Frankfurt Book Fair or London Book Fair) becomes essential to get direct contact with foreign publishers and sub-agents.

To maximize your presence in overseas Kindle stores, set up an Author Central account on country-specific Amazon sites, where possible, such as:

Amazon.es

Amazon.co.jp

Amazon.com.br

Amazon.cn

Amazon.ca

If you are selling your books only in English, set up your bio and book information in English. If you have a foreign translated version, use that language in that foreign online site instead.

Other companies like Apple and Kobo are also aggressively pushing into overseas markets. Kobo has teamed with booksellers throughout the world—e.g. British book chain WH Smith and French chain Fnac—as an exclusive e-book partner.

Pricing and Promoting in Overseas Territories

Marketing, promotion and enhancing discoverability are always the most challenging aspects of publishing, and these are even more challenging in an overseas environment. A key factor to consider is pricing.

“Setting an optimal e-book retail price for each country will always be a challenge,” says publishing consultant Thad McElroy. “Various indices offer different guidance for assessing prices abroad. Often mentioned is the Economist’s Big Mac Index, measuring the price of a McDonald’s Big Mac in countries around the world. Launched half in jest in 1986, the index has become a useful guide to understanding purchasing parity worldwide. Using the index, a publisher would determine that an e-book retailing for $9.99 in the US should be priced at $7.49 in the Czech Republic, $4.99 in Indonesia and $3.49 in India (using standard e-book price points in US dollars).”

Having a free book is a good way to be discovered in overseas stores. You can do this on Kindle by being part of KDP Select or, if you offer a book free through other stores, Amazon will eventually price match. This will happen first at Amazon.com, then slowly in the others (Amazon.uk, .de, .es, etc) over time.

Author Lindsay Buroker has blogged about making that strategy work for her: “It’s taken a while for the free e-books to percolate through, showing up in the international Apple stores, but I’m now … making between $1,500 and $2,000/month overall in overseas sales. … If I tried to target each of these countries individually through forums or paid sponsorships, it’d be a tall order.”

Author Lindsay Buroker has blogged about making that strategy work for her: “It’s taken a while for the free e-books to percolate through, showing up in the international Apple stores, but I’m now … making between $1,500 and $2,000/month overall in overseas sales. … If I tried to target each of these countries individually through forums or paid sponsorships, it’d be a tall order.”

Many other authors agree—but remember it’s not an overnight process and you should be clear about the value and pulling power of the book you are going to offer as your “discovery vehicle.” Like all permafree strategies, this one works best if the book is the first in a series.

For more about selling international rights, check out How Authors Sell Publishing Rights by Helen Sedwick and Orna Ross.

February 10, 2016

5 On: Reggie Lutz

In this 5 On interview, author and radio broadcaster Reggie Lutz discusses her tendency as a writer to synthesize fiction genres, recommends qualities to look for in a writing critique group, offers advice on pitching and interviewing with radio hosts, and more.

Reggie Lutz is the author of Haunted and Aliens in the Soda Machine and Other Strange Tales, and is an occasional broadcaster. Summers she can be heard on WRKC with her show The Not-So-Hectic Eclectic, featuring a mix of alternative music from the ’90s and now. She lives on top of a mountain with a parrot who offers editing advice and a dog who provides comic relief. A professional radio broadcaster in the ’90s, she has turned her attention to fiction writing.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: Is there a story behind your website’s tagline, “Lady Writer”?

REGGIE LUTZ: There is, but it isn’t very interesting. A lot of folks who haven’t met me assume I’m a guy because my first name is Reggie, and I have a fondness for hiding my face in photos. It causes confusion when meeting someone via telephone for the first time, which was more prevalent in ’90s radio. I used to get a lot of interactions like this:

Phone person: “Can I speak with Reggie Lutz?”

Me: “Speaking.”

Phone person: “No, I need to talk to Reggie.”

Me: (Sighs. Holds phone to shoulder for three seconds. Puts phone next to ear.) “Hi, this is Reggie. What’s up?”

Phone person: “I thought you were a dude.”

“Lady Writer” is just a tagline for clarity.

When you were little, you were reading the Little House on the Prairie series, you’ve said, but you also tried to read the North and South series because it was something your dad enjoyed. How would your review of North and South read had you written one at that time/age?

That’s a tough question to answer, because I don’t remember much of it. Given that I was twelve, I probably would have said something like, “I thought there would be more horses in it.” I remember being disturbed by discussions of slavery in those books.

Part of what disturbed me is the violence, but I kind of recall at least one passage where one family of slave owners was described as more fair than another family of slave owners, and though I couldn’t articulate it at the time, it struck me as a particularly insidious thing. It seemed like a justification, or an argument that there are degrees of slavery. It didn’t sit right with me, and I remember it made it hard to care about the characters. I don’t remember much else about those books, and that might actually be the reason.

What were you reading by the time you reached high school and, of what you read as a young person, what had the most fundamental influence on what you write?

By high school I was reading the beat poets, Anaïs Nin, Naomi Wolf, Alice Walker, the plays of Oscar Wilde, Shakespeare, of course. Joanna Russ was someone whose work interested me, and of course I was probably re-reading Tolkien. Ursula K. Le Guin was on my shelf. I read a lot of sci-fi because my brother and I were always swapping books—he was the sci-fi guy and I was reading contemporary fiction. By college I discovered Thomas Pynchon, Tom Robbins, and Angela Carter.

This is another tough question to answer. I have a hard time pinpointing the most influential storyteller I read, because I read fast and across genres. It’s probably the habit of reading widely that accounts for a lot of how I approach writing fiction. I’ll start writing something that is meant to be contemporary, and then I can’t resist putting in paranormal elements. Conversely I’ll start writing something intended to be fantasy and then it will turn out to be a drama about family, just set in a strange place.

I think that with early Pynchon and Tom Robbins there’s a sense that there are no boundaries / all things are possible that is freeing as both a reader and a writer. Their work, when I first encountered it, sort of widened the landscape for me in terms of what could be achieved with narrative prose. Tom Robbins, for example, could make a dirty sock, a spoon, a conch shell, and a painted stick magical and weirdly sexy as characters in a book. I can’t even begin to pretend that I can do the linguistic gymnastics those guys pulled off, but it was that blurring of genre with literary fiction that gave me creative permission to simply write the story I wanted to write and worry about genre later.

You wrote—and finished—your first novel when you were twelve. What was it about? What about it (besides finishing it) makes you proud, and what makes you cringe?

Oof. I don’t remember, and I haven’t looked at it in a long time, but it was probably a terrible mashup of S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and the movie Labyrinth. I’m proud that I did the work and was able to see it through at the age of twelve, but the rest, I am sure, is cringe-worthy.

When writing, what comes more easily to you, and what challenges you? And when you get to the challenge, what do you to do work through it?

As a pantser at heart, my biggest challenge is often plot. I do plot my novels very loosely, now, but I have this tendency to either go off and write deeply in tangential territory to the point where I lose the plot and have to re-tread, or if I’ve plotted too closely I’ll get mired in a certain scene that won’t come easily and get stuck re-writing the same sentence over and over.

The tendency toward narrative that will eventually have to be cut is the easiest to cope with because, in that case, words on the page are still words on the page, and if writer-brain wants to go off-roading, it is best to just let it go because there might still be something useful there.

When I get stuck in a scene and can’t move forward, sometimes I’ll just move to a different place in the chronology of the story and come back to the problem scene refreshed, or I’ll go into editing mode and work on what came previously. Editing will sometimes reveal what the issue is with the scene where you are stuck and jog something loose in terms of narrative problem-solving.

5 on Publishing

You’ve said of self-publishing that there are “a lot of hurdles your first time out,” including which projects will be best served by going the indie route. How did you arrive at the conclusion that your novel and short story collection should be self-published, and do you plan to try to get a traditional publisher for any of your works in progress?

A lot of the stories I write do not fit firmly into a genre, which can be an issue when attempting to go the traditional route. The novel Haunted was one of those, but I also knew I had something that deserved its chance out in the world. I was reluctant and afraid to go the self-publishing route with it at first, but the more I thought about it, the more the idea of self-publishing appealed to me. I figured that if I gained nothing else from the experience I would learn a lot, and that knowledge would help whether the next project was traditionally published or self-published. So partly it was awareness of the sort of project I had, and partly it was to see what I could learn and whether I could do it. I didn’t make a huge splash financially, but I broke even and did a little better, so I’m pretty proud of that.

A lot of the stories I write do not fit firmly into a genre, which can be an issue when attempting to go the traditional route. The novel Haunted was one of those, but I also knew I had something that deserved its chance out in the world. I was reluctant and afraid to go the self-publishing route with it at first, but the more I thought about it, the more the idea of self-publishing appealed to me. I figured that if I gained nothing else from the experience I would learn a lot, and that knowledge would help whether the next project was traditionally published or self-published. So partly it was awareness of the sort of project I had, and partly it was to see what I could learn and whether I could do it. I didn’t make a huge splash financially, but I broke even and did a little better, so I’m pretty proud of that.

The short story collection as a self-published project felt like a natural progression. I had several previously published pieces that had generated some buzz but were no longer available, in some cases, and some new stories that I once again could not find appropriate markets to submit to. Interstitial work, once again. I also wanted to offer something to readers who were curious about my other work, or waiting for the next set of misadventures with the characters in Haunted.

I do have a few works in progress that sit more firmly within genre categories that I plan to take to traditional publishing when the time comes.

What hurdles fell away (or got shorter) as you became more familiar with self-publishing, and which ones persist?

Formatting the first time was a tear-inducing exercise in frustration. The second time was far easier. It’s one of those things that the first time you do it seems impossible, and then suddenly everything clicks and the second time out is no big deal.

Marketing is a persistent challenge, largely because the things that work the first time out do not necessarily work as things change. In my case, I’m relying on internet word of mouth for much of this, and generating that kind of buzz is a crapshoot. Things change there every day.

My advice to people is to have as much fun with it as you can. One of the things I did for Aliens in the Soda Machine and Other Strange Tales was to hire Trevor Strong to write a song for the book, which was a blast. I uploaded it to YouTube with a cover of the book as a video, and when Aliens was released I used the song in social media posts as a fun way to promote it. I had the idea that this would be a great payoff for audiences who stick with me through literary shenanigans, almost like a fun internet Easter egg people might find down the line.

I’m not sure how well it worked in terms of marketing, but I view it as a fun bonus for the audience as they find my work. It was also an opportunity to blend two of my greatest loves: music and fiction.

As part of the pre-self-publication process, you send (or used to send) your writing to Claw Critique for feedback. What was the system there, and what key things would you say to a writer considering joining her or his first critique group?

As part of the pre-self-publication process, you send (or used to send) your writing to Claw Critique for feedback. What was the system there, and what key things would you say to a writer considering joining her or his first critique group?

Claw Critique is a critique group that meets in real life. I moved after I hooked up with them, but I continued with them online.

When searching for a critique group, I would suggest keeping in mind that you want a group whose writing goals match your own. Are you writing fiction, screenplays, memoir, etc., and does the group take those forms on? Is their level of seriousness about craft the same as yours? Are they meeting with the intent to produce work for publication, or is it hobby writing?

You won’t necessarily be able to figure all that out right out of the gate. Don’t be afraid to shop around for the right fit. Ask a lot of questions.

When you submit for review, at least the first time, I suggest only submitting work that is in at least a complete first draft stage. Make sure they do have a process in place. Our critique group developed a process to make sure everyone who had work up for review in a given week got time and attention. The way we did it was to have everyone submit new work, either a chapter or a short story, the week before it was to be reviewed. Then at the meeting we’d take turns offering feedback. The author was allowed to respond once the feedback had been delivered.

We met once a week, but that frequency doesn’t work for everyone, so look for something that will match your schedule. Online we have a closed group and you can post as you finish things, then folks can respond as time permits, but meeting in person is invaluable because things come up when conversation is made possible that won’t come up in an online forum.

You’ve interviewed authors as part of your radio broadcast. What advice do you have for authors being interviewed in a voice-only environment?

Get comfortable with sentence fragments and be prepared for snark.

I would suggest finding out a little about about the program and the host’s personality beforehand, if you can. The reason I say this is that the way someone approaches interviews on a college station is different from what someone working for NPR will do, and someone who hosts a commercial music format will deliver their questions very differently. There’s sometimes a disconnect: what sounds fun in an audio-only environment can sound almost hostile in real life.

Another thing to be aware of is that, unlike a conversation in person, radio hosts will ask a question, let the guest answer, and then move onto the next question without responding in a satisfying way to the thing the author has just said. It can feel really awkward. This has to do with radio format and keeping the program moving for the sake of the audience. If you can do the interview pre-recorded in a studio, things are easier, because you can have a regular conversation with the host and then, in production, someone will edit out all of the ums and ahs to make it sound good.

Also, remember that you, as the author, would not have been invited if the programmer or host didn’t think you were worth having on the air. Don’t worry about perfect delivery, diction, or even making sure every last word is interesting. It’s up to the host to work around things like that. It will get easier each time.

And: the thing you said you feel most anxious about is probably the very thing that lands best with an audience.

When it comes time to pitch an appearance, send a press release that is clean, short, and as to-the-point as possible. Media outlets tend to receive a ton of press releases that are about everything from recent releases of different kinds of art to announcements about lost dogs, so if it is too long the person who vets such things might set it aside. Send links and relevant information. (Email works best.) If you have an appearance upcoming in the same market the radio station broadcasts from, you have a better chance of getting on the air, because it serves local interests. So be sure to mention that in the release you send.

When writing a press release, error-free is always desirable, and be as straightforward as you can. I think if you are an author who writes humor, then going for funny is a good thing; otherwise, you want to be as clear and concise as possible. If you have public speaking experience or have done interviews previously, include those things, because that indicates you’ve got guest chops, meaning you’re more likely to be engaging to an audience.

Programming needs change very rapidly in radio. On the program I do as a volunteer, I have control over content, so when I am doing author interviews it tends to be with people whose work I am interested in, and I reach out to invite people to appear, which is a bit unusual. If time passes after your first pitch and you want to follow up, emailing once again is probably best. If you don’t hear back, it can mean a million different arbitrary things. My advice is to simply let it go and try again with the next project.

You’ve had to do a lot of your own PR. What were you almost positive would work that, in fact, didn’t, and what more than anything else has drawn attention?

As much as we have all come to depend on the internet, print media is still really important for bringing awareness. As someone who works in radio, I know what radio can still do to boost awareness, and that, too, is a lot more than people think.

I don’t know that I was confident that any one particular thing would do wonders. I think, because of my experience working in media, I knew before going in that PR works best when you don’t hang your hopes on any one attempt. You send your press releases to as many media venues as you think might bite and cross your fingers and hope that enough things hit in the right time to make a positive difference.

Nothing can replace the connections you make with other human beings who love story, though. That’s everyone from your best friend to the random person you strike up a conversation with at a coffee shop or bar.

Thank you, Reggie.

February 9, 2016

Writers’ Consortiums and Co-ops: What They Are and How to Start One

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by author Ursula Wong.

The combination of independent publishing and the broad use of social media has provided many ways for writers to produce books and engage with readers, but it has also forced writers to do more than just write.

Editing, formatting manuscripts, organizing book launches, maintaining a social media presence, and more, have become the writer’s responsibility. Publishing services can reduce the amount of work an author must do to produce a book, but they can be pricey. Critique groups or workshops can reduce editing cost, but may not find systemic issues in novels.

Writers’ consortiums (or co-ops) offer another path. While consortiums require an author’s time and energy as well, and have their own limitations, writers’ consortiums that apply business principles may offer authors an advantage in quality, cost control, and marketing.

Typically, writers’ consortiums are groups of writers who meet for the purposes of workshops, education, and networking. Some require members to pay yearly fees, and some, like the New Hampshire Writers’ Project, have a board that arranges events and provides services to the community.

In business-based writers’ consortiums, members share the work needed to edit, produce, and market their books. Members focus on mutual success. They pool their resources and time to undertake the editing, formatting, and promotion of books created by individual writers or by several authors who are writing a book together. They may have an associated publishing company, or members may publish independently.

Business-based writers’ consortiums achieve synergy from many people working on each book and each bringing his or her unique skill set to the production process. Sharing the editing work saves money, and marketing reach is broader than any one person could easily achieve, resulting in more sales potential.

For example, one member of The Storyside, a business-based writers’ consortium, used Facebook advertising to promote a new book, and achieved about 250 Facebook “likes” in two days. That number doubled when members also promoted the book through personal channels, ultimately reaching about 14,000 users, far more than any one person could have reached on their own.

Some groups that employ the principles of the business-based writers’ consortium are the Book View Café (BVC), the Writers Co-op of the Pacific Northwest, and The Storyside.

BVC, a cooperative publisher, started in 2008 and has fifty members. Writers manage the production and marketing of their own books while leveraging resources of the organization to create ebook formats, boost social media announcements, and so on. BVC offers an impressive catalogue of competitively priced titles and most of the retail price goes to the author. New members have typically published traditionally, and offer specific skills to the organization. BVC has grown into a mainstream publisher for member authors, offering over 100 books a year.

The Writers Co-op of the Pacific Northwest started in 2015, and has over 30 authors who share resources within the group for editing, assistance with query letters, layout, marketing, and more. Their focus includes building communities on social media, cover design, and improving Amazon ratings. Individual writers must choose their own publishers, but the co-op assists by working with local bookstores to promote member offerings.

The Storyside consists of 5 writers who have published both traditionally and independently. Members focus on controlling costs, providing quality books, and experimenting with marketing techniques such as seasonal book sales, online advertising, and book events. The Storyside has an associated publishing company for its members.

Even with its advantages, business-based writers’ consortiums may not be the right solution for everyone, since they take time away from writing. Others may be skeptical about the success of collaborative efforts, and avoid them fearing that the work expended outweighs the benefit. Members must manage this problem.

Suggestions for Joining or Starting Your Own Consortium or Co-op

Organize. Determine yearly objectives and deliverables. Decide short-term and long-term goals. Create plans, schedules, and a budget.

Plan. Create a production plan and a contingency plan for each book, and track progress. How will you overcome delays if a member cannot do their work for some unforeseen reason? Will you divide the work or delay the schedule? What happens to the rest of the manuscripts in the pipeline?

Choose a leader. One person needs the authority to finalize schedules, keep the group focused, and mediate decisions, such as a shift in goals.

Discuss roles and responsibilities. Members will have different skills, although minimally, each should have editing experience. Be aware of inequities. A good copyeditor may spend an inordinate amount of time preparing a manuscript for publication, especially when that person is responsible for copyediting every book in the pipeline. If this happens, discuss solutions such as adding another member with the required skill, hiring temporary help, sharing the work, and so on.

Discuss problem escalation. Expect disputes between members, for commitment may wane because of outside obligations, and creative people may disagree about a change in direction. Discuss how to mediate differences.

Determine how to grow. Decide how to find and vet new members. Is there a probationary period? Does the consortium need a person with a particular skill? Discuss soft traits such as enthusiasm, ability to “fit in,” and shared goals.

Discuss the possibility of downsizing. Members may choose to leave for various reasons, or a problem could arise, prompting the group to ask a member to resign. Minimally, set the expectation that new people may join and others may leave.

Try new things. Experiment with anything that sparks the creative interest of members. Track web traffic, social media access, and sales to judge reader interest.

Note the synergies. The benefits of collaboration can be significant. The social media reach extends significantly when every member participates in promoting a book. Writers who edit others’ work become better writers. Writers committed to the success of each book create better books. Expertise can shift over time, ultimately leveling the work and creating a stronger base of experience.

Celebrate success. Finding people willing to put time and effort into helping each other succeed is a gift. Cherish it and repay the kindness.

Fundamentally, writers’ consortiums rooted in business principles are still creative people working together on shared projects. Expect problems. Solve them together. Talk. Try to stay close. Review goals and refresh commitment regularly in order to keep the team focused and excited, and to help ensure success.

Note from Jane: This post is written by a member of The Storyside, a business-based writers’ consortium centered in New England. Learn more about its members at its website.

February 8, 2016

Are Paid Book Reviews Worth It?

photo by StockMonkeys.com

Paying for professional book reviews remains a controversial topic that very few authors have practical, unbiased information about. In fact, it’s not even well-known in the author community that paid book reviews exist, and even less is known about the value of such reviews.

Before I discuss the pros and cons of paid reviews, I want to define them (strictly for the purposes of this post).

Trade book reviews. Trade publications are those read by booksellers, librarians, and others who work inside the industry (as opposed to readers/consumers). Such publications primarily provide pre-publication reviews of traditionally published books, whether from small or large presses. Typically, these publications have been operating for a long time and have a history of serving publishing professionals. However, with the rise of self-publishing, some trade review outlets have begun paid review programs especially for self-published authors. Examples: Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews.

Non-trade book reviews. Because of the increased demand for professional reviews of self-published work, you can now find online publications that specialize in providing such services. These publications or websites may have some reach and visibility to the trade, or they may be reader-facing, or a mix of both. Examples: Indie Reader, Blue Ink Review, Self-Publishing Review.

Reader (non-professional) reviews. It’s considered unethical to pay for reader reviews posted at Amazon or other sites, and Amazon is actively trying to curb the practice.

This post is focused on the first two types of paid reviews; I recommend you stay away from the third.

Some of you reading this post may be looking for a quick and easy answer to the question of whether you should invest in a paid book review. Here’s what I think in a nutshell, although a lot of people will be unhappy with me saying so:

The majority of authors will not sufficiently benefit from paid book reviews, and should invest their time and money elsewhere.

However, this can be a more nuanced issue than this broad statement indicates. Here are three questions I ask authors when advising about the value of paid reviews:

Do you have a well-thought-out marketing plan that targets librarians, booksellers, or schools?

What is your overall marketing budget, and does it include hiring a publicist or outside help?

What’s your book category? Are you trying to market a children’s book?

Let discuss each issue in more detail.

1. Are you targeting the trade?

It makes little sense to pay for a trade book review if all you’re going to do is make your book available for sale on Amazon or other online retailers and consider your marketing job done. This is a huge waste of your money, yet this is what many authors do, because what they’re mainly after is validation, not a marketing tool.

Ask yourself: Do you want this review because you feel it’s part of having “real” book published—that having it gives you some additional credibility? If that’s your only motivation, you are paying to feel better about yourself and your work, not to sell books.

A better way to sell more books on Amazon, or through online retail, is to generate as many reader reviews as possible. Some might argue that having a professional review as part of the book’s description on Amazon (and elsewhere) adds a sheen of professionalism and leads to more readers taking a chance on the book. But I believe readers are generally not persuaded by one professional review when there are few reader reviews and/or a low star rating. Like it or not, purchasing behavior online is driven by quantity of reviews that help indicate a book is worth the price, assuming no prior exposure to the author.

However, if you have an outreach plan that involves approaching libraries to consider your book, or if you’re trying to reach independent booksellers, then having a positive review from a source they know can help you overcome an initial hurdle or two. It will not guarantee they will carry or buy your book, but it may help make a favorable impression. (That said, they may know your review was paid for if your book is self-published. This probably won’t matter to them as long as they trust the review source.)

Another thing to understand is that even if you pay for your trade review, that doesn’t mean it will have as much prominence or visibility as other (unpaid) reviews from that publication. Paid reviews are typically segregated and run separately from unpaid reviews, so a bookseller or librarian may have to actively seek out reviews of self-published books. How much attention these reviews receive from the trade, in aggregate, is anyone’s guess. One thing is for sure: there’s a ton of competition even just among traditionally published books.

All of this assumes that the paid review you receive is positive or will make a good impression. The review may, in fact, be negative, and you won’t be able to use it. (In such cases, the trade review outlet allows you to suppress publication of the review altogether.)

If you are targeting the trade, and you’re operating on a professional level, then consider approaching trade publications just as any traditional publisher would: four to six months in advance of your book’s publication date. (Since the focus of these trade publications is on pre-publication reviews, they won’t review your book if you don’t send the copy several months in advance of your pub date.) Send an advance review copy along with a press release or information sheet about the book, and cross your fingers that your book is selected for review (for free). If not, later on you can consider paying for a review if necessary.

If you’re not targeting the trade, sometimes a paid review can still be helpful. That brings us to the second question.

2. What does your overall marketing plan look like?

If paying for a review consumes all of your marketing and publicity budget, stop. This isn’t what you should spend your money on. You’d see far more sales from spending that money on a BookBub promotion or on other types of discounts or giveaways to increase your book’s visibility.

On the other hand, if the paid review is just one piece of a larger marketing plan to gain visibility, then you’re in a better place to capitalize on a positive paid review. If you can see it as a steppingstone—as a way to get people on board quicker—that’s the right mindset. A positive review from a known or trusted source can help lead to other reviews—or interview opportunities, or other media coverage. Or you could use the review in advertisements to the trade.

With paid reviews, remember: steppingstone. It’s not paid review = book sales. A good marketer or publicist can help open doors for you, and they could have an easier time if they’re armed with some good blurbs or coverage (including that paid book review) to start.

If all you intend to do with your paid review is add it to your book cover, your website, your Amazon book description, or other online marketing copy, then it is not likely to have any noticeable effect on your sales. (And frankly, in such cases, there is no way to measure if it really did make a difference.)

3. What’s your book category?

The children’s market is one area where I think paid reviews can make the most sense, because you’re not typically marketing directly to readers (children) but to educators, librarians, and schools. The children’s market highly values trade publications such as School Library Journal or Publishers Weekly; these publications help them understand what’s releasing soon and make good choices about what to buy, often on a limited budget.

Here’s the rub: you can’t buy a review in either of those publications I just mentioned. You would have to submit to them through the traditional channels at least a couple months (or more) in advance of your publication date.

I spent more than a dozen years in traditional publishing and oversaw the publication of hundreds of books. During that time, only a handful of our titles received professional trade reviews. By and large, our company did not submit books for review, and pre-publication reviews did not perceptibly affect our sales when they did appear. That’s because our books were mainly in instructional or enthusiast nonfiction categories, where sales aren’t typically driven by professional or trade reviews.

If you don’t have industry experience, it may be difficult to figure out if a paid review might make a difference for your particular book category. Here’s what I recommend: Using Amazon, find books that would be considered direct competitors to yours. Take a look at their Amazon category or genre (e.g., paranormal romance, cozy mystery, etc.), then look at the bestsellers in that category over a period of a week or two. (If you can, make sure you research a good mix of both traditionally published and self-published titles.) Read the books’ Amazon page descriptions and see what review sources are quoted. Many times, you’ll find (free) blogger reviews and a variety of (free) niche publication reviews, rather than reviews from the companies I mentioned at the beginning of this post.

Taking the time to pursue free reviews or reader reviews is the preferred method of established, career indie authors; they’re rarely concerned about courting the traditional gatekeepers, unless their work is of a literary bent.

Paid Book Review Benefits That Don’t Really Mean Anything

Most paid review outlets promise that your review will be distributed to Ingram, online retail sites, and all sorts of important-sounding places. This type of review promotion doesn’t discount any of what I’ve discussed above. Again, just because the review is distributed or available doesn’t mean it will be seen or acted upon. And I don’t recommend that you pay these companies for extra promotion or advertising of your review unless you really know what you’re doing and a marketer or publicist thinks it will get your book in front of exactly the right audience. Too much of online advertising is like flushing money down the toilet—whether it’s done through these companies or not. If you’re interested in quality and targeted advertising for your book, consider M.J. Rose’s AuthorBuzz service, but even then, make sure it’s only one part of a larger marketing plan, not the only part.

Are Paid Book Reviews Tainted?