Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 134

March 9, 2016

5 On: Henry Baum

In this 5 On interview, author, songwriter, and Self-Publishing Review founder Henry Baum (@henrybaum) discusses self-publishing services, the value of a paid review, why he started his own self-publishing service, and more.

Henry Baum is the author of the novels Oscar Caliber Gun, God’s Wife, North of Sunset, and The American Book of the Dead. He’s published work with Identity Theory, Storyglossia, Scarecrow, Dogmatika, Purple Prose, 3:AM, Les Episodes, and others. Both traditionally published and self-published, he founded Self-Publishing Review in 2008 and Kwill Books, a hybrid publishing service, in 2015. Born in New York City and raised in Los Angeles, he currently lives in Spain with his wife, Cate.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: In your books, there is a running theme or feeling of rage, decay, disappointment, and disgust when it comes not only to the celebrity culture, but the culture of attention-excess in general, I think. What draws you to what you write?

HENRY BAUM: I grew up in Los Angeles and went to high school with a lot of Hollywood kids (Jack Nicholson’s kid, Cher’s kid, many others). My father’s a screenwriter, mom’s a producer, so I was steeped in it. I went on to write novels about Hollywood and then about fundamentalist religion, which isn’t so far off, as my parents treated Hollywood like it was a religion, replete with its own gods.

Now that I live overseas I have a new perspective on the country, where people here don’t think America is the center of the world but find it curious and demented, which it is. Maybe it’s because I don’t recognize any of the celebrities in Spain, where I live, that pop culture doesn’t permeate me. But then I don’t think pop culture permeates anywhere as much as in America.

Now that I live overseas I have a new perspective on the country, where people here don’t think America is the center of the world but find it curious and demented, which it is. Maybe it’s because I don’t recognize any of the celebrities in Spain, where I live, that pop culture doesn’t permeate me. But then I don’t think pop culture permeates anywhere as much as in America.

Your book Oscar Caliber Gun at one point experienced a title change, becoming The Golden Calf. Now, upon its recent re-release, it’s back to the original title. What prompted the title changes, and have you noticed a difference in how buyers react to the respective titles?

No one understood the original title—except those who understood it. One woman at a reading asked me, “Is your name Oscar?” It was depressing, and I kind of gave in to the stupidity. But mostly the book was picked up by Canongate in the UK, and the title didn’t translate over there at all. Then it was re-printed by Another Sky Press in Portland, OR, and I thought I’d stick with the title. All the while not feeling like I was being true to my original intention for the book, so I released a Kindle version with the original title.

I know writers around forty years old who have decided to give up on writing. This is after years—decades—of being very passionate about it. I’m thinking people around this age possibly decide that having not reached a certain level of success (whatever that might mean to them) is a signal that it’s time to say, “Okay, this is ridiculous. I’m obviously living in a fantasy land and should probably stop fooling myself.”

Have you ever had thoughts like this, and if so, will you take us through what that period was like for you and what conclusion you reached?

Actually, I think the opposite. Forty is when a lot of writers hit their stride. I’ve actually unpublished my earlier self-published novels because I think they need work, and I think only now do I have a better sense of objectivity and more-reasonable self-criticism than I did when I was in my twenties. Back then I thought I was going to be a literary phenom, and it may be depressing that it didn’t really pan out like I’d thought, but I was pretty naive and self-obsessed in my twenties, and that showed up in my writing. Full of self-doubt, but under the misapprehension that my writing was the sole place where I had it all together. I didn’t. Now I’m older, understand a bit more how the world works, and I think I’m a better writer for it.

All that said, yeah, I’ve also thought of dropping out, because who wants to write for hours on end and not be guaranteed a lot of readers, but that’s only when I’m feeling really low and don’t really mean it. I guess it’s easier to make the decision to stick with it, given I have steadier income than I did in my twenties and I was desperate to hit it big and solve my life. That’s partially why I rushed things out there, hoping to get lucky, and too certain that I would.

Generally, it makes no sense to have success determined by how much money you’ve made, how many reviews you have, how many fan letters you get. Given what’s overly successful in this day and age, I’m not quite as bothered if I’m not lavished in praise. I’ve come to terms with being a niche writer who’s liked by some people, not at all by others. So I’m not giving up writing, any more than I’m giving up songwriting, even though I’ll never be a rock star.

You wrote a song for each chapter of your novel The American Book of the Dead. What came first in your life as a writer, lyric writing or fiction writing, and how did you decide for each chapter what the song would focus on lyrically and sound like musically?

I’ve been a musician for longer than I’ve been a writer, but I didn’t become a songwriter until after I wrote two novels. I played drums or bass for other people’s bands. I think being spread thin like that has screwed me in some way because I haven’t focused intensely on one thing; I always feel the pull of the other. Anyway, I really despise writing lyrics, as I’m more comfortable writing long-form prose. I put pressure on myself to be writerly in lyric writing, but it just doesn’t come naturally to me.

But I love writing melodies. The idea with the book project was to have a theme in place so lyrics would come easier, and it worked well enough. It was also fun to match the mood of a song to the chapter, so more epic songs came at the climax of the book, quieter songs in the beginning. I’m a fair fanatic of rock operas, and this seemed like an interesting way to write one. I always write the music first, plus the vocal melody, and lyrics come later, so I had a lot of unfinished songs. I’ve taken to writing instrumental music lately to avoid this issue entirely.

What’s an average day for you in your role at Kwill and/or SPR, and how does the work feed the creative part of your brain?

Running a self-publishing business entails writing reviews, posting content, corresponding with authors, managing social media accounts. The SPR office is at work fourteen hours a day—much of it by my wife, Cate, who handles editing and more hand-holding of authors. Authors can be pretty impatient if things aren’t going up immediately, and we spend a lot of time discussing their books with them on email.

To get into the depressing end of the spectrum—I also have to do dialysis three times a day for kidney disease, which is part of the reason I’ve worked so hard on this work-at-home business. I always knew at some point I would never be able to go to an office. That time started about five months ago.

At least we’re on the South Coast of Spain. Down the road’s a cathedral and a castle and the bullring. I have no interest in bullfighting at all, but I like being in a culture that doesn’t have a lot to do with my own. Virtually no one here has their face in a cell phone. I’m drenched in the internet all day, and it’s nice to be in a place with some history.

5 on Publishing

When you self-published North of Sunset, you used Lulu instead of one of the companies offering publishing/marketing packages. Have you noticed changes in how such companies operate over the years? I realize I’m practically laying out a carpet for, “Of course they haven’t changed; I never liked them, which is why I started my own,” but surely they’ve had to adjust to a community of writers who are more self-publishing savvy than they were at the onset of self-publishing.

The first self-published book I ever saw was my friend’s novel, who published with Xlibris in 2005. I thought, “Holy shit, this is a book.” I’d been struggling for years with agents (I’ve had around five) and getting traditionally published, and it was a revelation that I could do it myself. I’ve always been a DIY person—putting together fanzines, designing covers for demo tapes, and so on—so it seemed natural.

To be honest, I went with Lulu at the time because it was free and I couldn’t afford the Xlibris fee at the time. I also liked having complete control. This was back when there were literally three Blogspot.com blogs devoted to self-publishing and reviewing POD paperbacks. I don’t know how much I would have done differently then, because there weren’t too many options, though I’d never use Lulu today. I ordered a slate of books a couple years ago and the books came apart in my hands.

I’m not a person who’s against self-publishing services. There’s this echo chamber of people talking about anyone who uses a self-publishing service as not real self-publishing. Really, be quiet. If you’ve made the decision to release the book yourself, that’s self-publishing. Whether you upload it to AuthorHouse or Amazon KDP. A service like Author Solutions is awful in my estimation because they overcharge people for services that they can get elsewhere. But it’s at least understandable if people want to pay for a service that handles everything. I mean, really, tell Lisa Genova and Julianne Moore that iUniverse is a lesser form of publishing—I’m sure they don’t care a whole lot.

I’m not a person who’s against self-publishing services. There’s this echo chamber of people talking about anyone who uses a self-publishing service as not real self-publishing. Really, be quiet. If you’ve made the decision to release the book yourself, that’s self-publishing. Whether you upload it to AuthorHouse or Amazon KDP. A service like Author Solutions is awful in my estimation because they overcharge people for services that they can get elsewhere. But it’s at least understandable if people want to pay for a service that handles everything. I mean, really, tell Lisa Genova and Julianne Moore that iUniverse is a lesser form of publishing—I’m sure they don’t care a whole lot.

The reason we started Kwill was to offer a good version of a self-publishing service—an antidote to Author Solutions services. Already we’ve seen negativity about the service, for the sheer fact that it’s a service, and writers should only go it alone. Some people want help; some people don’t. It’s not taking advantage of writers to give them the option, especially since it’s reasonably priced with a reasonable profit margin and we market books in ways other services don’t. We make sure authors have a return and some sales in the three months we work with them. We also only publish a few books a season, so it’s more personalized. We spread them out over the year on a project managed schedule so we don’t overlook any part of the process and can spend the maximum time with each author.

It seems awfully weird to me that there should be such gate-keeping about the right way to self-publish. The whole point of self-publishing is that it gives people freedom to take the road they want. Certainly, you can steer people away from the ripoffs, but that doesn’t mean every single service is taking advantage of writers.

Given the experience and connections you have, the ability to guarantee Amazon bestsellers, and the skepticism still surrounding the idea of pay-to-publish companies, why not either create a traditional publishing company or a marketing/PR company, both of which can generate percentage-based earnings, rather than a pay-to-publish company?

Because we’re self-publishers. We love the tools of self-publishing and want to improve on the whole system. I don’t want to be a gatekeeper of other people’s writing. I hated being on the other end of that, so I wouldn’t really want to be part of that model. They’re still in complete control of what’s released. We customize every single part of a Kwill package as we go along. Traditional publishing doesn’t give you that control.

Kwill and SPR are marketing companies. What you’re paying for at Kwill is editing, book design, and Amazon marketing, plus 100 percent royalties as if you did it yourself. Additionally, the press is registered as a publishing house by epigraph; we’re not just a website that does it for you like most services. Authors get the perks of publishing with a publishing house, such as more Amazon categories, so it’s a hybrid model, and that interests me a lot more than something that conforms to the old model.

About that Amazon bestseller thing—there’s was a viral post going around that could make it sound like we do the same thing, make a book a bestseller in an obscure category. We don’t—we get a bestseller in a top-tier category, plus sales and reviews, within Amazon’s terms and conditions. We’ve met with their lawyer. We’re careful about this.

It’s an uphill battle. Just as self-publishing had to fight for notice in the publishing world, our services need to fight for legitimacy within the self-publishing community. But the internet is an outrage machine.

Kwill offers “Guaranteed bestseller listing on Amazon using unique marketing techniques.” What can you share about those marketing techniques that might be useful to authors doing their own marketing and publicity?

Well, not a lot, actually, in the same way that what BookBub does is not applicable to what authors can do themselves. BookBub has a list of people who are willing to buy a book, and so do we. The advice these days is that starting a newsletter is the best way to get repeat customers. What people with us are doing is buying access to a proven newsletter with people who are guaranteed to buy the book and, 7/10 times, review it. We also tweak Amazon keywords and categories to get a book a higher ranking—again, not just in some obscure category that’s easy to rank. We use mostly BISAC high-tier categories combined with sensible and logical keywords. That is something authors can do themselves and very often get wrong. Having access to readers willing to buy a book on demand is not something writers can do themselves without building up their own list.

An initial Kwill contract lasts as long as Amazon’s exclusive KDP Select term (three months), at which time the author has the option to renew for a year and expand distribution. Why not offer a full year at the start with the option to make the manuscript file available for expanded distribution (print, other ebook sellers, audio) after the KDP term ends? Are authors likely to recoup the cost of the contract in those three months, or as a result of those three months—or is earning money secondary to simply getting attention? Really what I’m asking is, if not money, do they get attention even possibly from agents that could lead to a contract and eventual income? Or is it, in the end, ultimately vanity (I ask possibly on behalf of my shadow)?

The reason we have a short window is to give writers as much flexibility as possible, if they want to take the reins after we do the launch. The first three months of the book are the most important on Amazon, so we handle that initial push.

There is no way that you can guarantee an income for a book. The fact that a writer gets an agent and a traditional publishing deal does not then guarantee a career for that writer. We give a book attention, but we can’t guarantee every single book makes thousands of dollars in the first three months.

For some reason, this is the sort of question asked to self-publishers. Would you ask an independent press if they can guarantee thousands of sales right off? It’s a miracle for small presses to sell 3,000 books over a book’s lifetime. So writers might not be guaranteed to recoup their investment, but they’ve gotten editing, design, and a launch that gives them a better chance. That’s valuable, even if it doesn’t pay back immediately.

Is that vanity? I don’t think so. What that question is implying is, if a book isn’t making money, then it’s vain to bother. Money isn’t the only kind of value—that’s much darker an idea than self-releasing a book. It’s not vain to express yourself and want people to read it. It’s vain to get plastic surgery.

Most books don’t sell. Most self-published books also don’t sell. This isn’t a controversial statement. The fact that Author Earnings can tout that more self-publishers are making more money does not mean that’s the case for the average writer. So Joe Konrath and Barry Eisler may be inspiring, but they’re also anomalies, and saying their huge platforms are then applicable to every writer doesn’t make sense. The idea that there are some self-published millionaires has pushed this idea that self-publishing is about making a lot of money. I mean, that’s why I got out of traditional publishing—all the talk about “the market.” It’s a shame that that’s where much of the self-publishing talk is, even if it has given self-publishing a lot of legitimacy. And it’s great that more writers are making money than before—but more writers aren’t as well. But there are a lot of reasons people self-publish, and it’s not all profit motive.

So to give authors a chance to see how their book does after three months with our best marketing efforts will inform whether they want to spend more on their hard copy version, or if they are fine with being e-only. It’s better than a heartbreaking scenario we see all the time of authors telling us they spent a lot of money on print books and don’t know what to do with them now—even print on demand isn’t always necessary at first.

SPR offers paid book reviews, and a Kwill package provides, as one of its promised book reviews, one from SPR. In recent discussions both here at JaneFriedman.com and at the website of Porter Anderson, you’ve defended the paid book review as a critical first domino: not only does that first review from a respected, if paid, source lend validity to the work, but it also encourages more reviews.

In the comments following Jane’s article, “Are Paid Book Reviews Worth It,” you first quote Jane:

A positive review from a known or trusted source can help lead to other reviews—or interview opportunities, or other media coverage. Or you could use the review in advertisements to the trade.

Your reply:

Then what’s the argument against paid reviews, given that the majority of authors use a review exactly like this? You mention in passing things like back cover copy/Amazon Editorial review/marketing materials like those are small issues—those are huge parts of a book release. I obviously have skin in the game of paid reviews, but this really isn’t looking at what paid reviews offer in the current market.

Is that what paid reviews offer in the current market—the domino potential, interview opportunities, other media coverage—or is there more/something else? What is being missed about the value of a paid review, and does any of it translate into income?

In short, yes. The gist of the debate I had with Jane was she was saying that paid reviews are not a very good avenue to get noticed by the trade. My response was the most authors don’t care about trade outlets, they care about their Kindle page. And a paid review in the Editorial Reviews section of a Kindle page is very useful—certainly more useful than having an empty Editorial section.

They talk about marketing services as if there’s an exact cost-to-benefit ratio—as if something that doesn’t pay back immediately has no value. But that’s not how books ever work. Books should be about an entire career, not just the latest book. That’s always been my frustration with the traditional publishing industry, as writers need to be nurtured over time.

But the Kindle has a very short window as well. So if you release a book with nothing in the Editorial Reviews section and zero customer reviews, it’s going to be very hard to get it to take off. We can’t promise that the book will take off, but we can promise that you’ll have reader reviews and an Editorial Review—even a low-rated review will have something to excise for a blurb.

The misconception is that it’s easy to get free reviews. There are thousands of books self-published every week, so review blogs can’t really take on everything. SPR is a site with a good amount of traffic, unlike small book blogs that might review a self-published book. Bigger sites will often review more popular books. So with a site like SPR or IndieReader, you get a review on a popular site, which some people use like a manuscript critique, and something to put in your Editorial Reviews section, whose reviews are posted before customer reviews on Amazon.

I’m repeating myself, but I really don’t understand why this is such a big deal. It’s more helpful to have extra coverage than not. BookBub is also a decent way to spend money on marketing, but that’s just a day’s newsletter, whereas a review is permanent.

Does it lead to income? Again, that’s not the only measure of something’s worth. And the answer is, it will lead to book sales for some books, but not others. This week we had one lady write in to say her book got to number one on Amazon because of our review. Last week a guy jumped from the hundred thousands to just a few thousand within hours of his review being shared. Some people, yes, don’t sell a lot. All books don’t sell the same, whatever their marketing. But to remove tools from the box of self-publishing when there are so few seems like you’re not giving yourself a chance to get in front of readers. Self-publishing is a pay-to-play system—even free services require paying for editing and book design. Marketing is part of that. No one source of marketing is a cure-all. Facebook ads, newsletters, BookBub sites, Goodreads, the usual things. It seems obvious that using all types of marketing will help writers more than hurt them.

All that said, there are some paid review services that are way too expensive. But if you can afford it, why not? However, no one should have the illusion that any marketing will sell a book automatically. Nothing’s automatic in publishing.

Thank you, Henry.

March 8, 2016

How a Website Redesign Solved an Author’s Identity Dilemma

I’ve known Gigi Rosenberg by reputation for many years, as the author of The Artist’s Guide to Grant Writing, the most comprehensive book I know of on writing and winning grants. (Hint: It’s just as much for writers as it is for artists.) She’s also the editor of Professional Artist, an award-winning business magazine for visual artists with 20,000 subscribers, and is currently writing a memoir.

Last year, over a series of months, we discussed her big-picture goals for her online activity and platform, as part of a social media course I was running. We both agreed that one of her most important next steps was relaunching her author website at gigirosenberg.com.

Her new website is now in place, and the transformation is dramatic and successful. Because this is an area where I know many authors struggle to make progress, I invited her to answer a few questions about how she got it done—especially since she didn’t have to spend a fortune to do it.

What wasn’t working with your old site? How did you know it was time for a refresh?

My old site looked dated. The photos were small, the pages were narrow and it had too much text. But worse than that, it didn’t represent who I’ve become in the last nine years since I first launched my site.

Also, nothing was automatic. The events page only updated when I remembered to do it. There’s nothing worse than a two-month old event headlining your events page.

I kept procrastinating on the redesign because I had a conundrum: how could I represent myself as both a creative writer and an artist coach? Some people (including you!) suggested I make two sites. But I didn’t want that split. I’ve felt split most of my life between my creative self and my teacher self and I didn’t want to be split anymore. A new website felt like the way to bring the two sides of myself together.

This merging also made sense from a marketing perspective: my being a writer makes me a better coach because I’m shoulder-to-shoulder with all the other artists out there trying to make sense of succeeding as a creative person.

Gigi’s old homepage (left) and new homepage (right)

With the website relaunch and redesign, you ended up leaving WordPress and moving to SquareSpace. Deciding to change platforms is always a big deal—how did you know this was the best move?

I signed up for the free trial at SquareSpace thinking I would just fool around. But within a couple of days, I’d found a template and I’d built most of the site.

SquareSpace gave me independence. I was no longer waiting on another person to translate my ideas into a design. I could drop in photos, write text and see for myself how my words read on the page. It had the immediacy of making my site with paints and glue and cut-up images. If I were more technically savvy, maybe I could have found that with WordPress, but I liked the image-heavy designs on SquareSpace.

Mostly, I liked SquareSpace because I could work on the site myself and see how some of the conundrums starting solving themselves.

Another decision that can be difficult: whether to hire a professional designer. You work in the professional artist community, so I know the visuals of your site are critical. What was your approach?

The best advice I received from a designer colleague was: “Don’t screw with the typefaces on SquareSpace!” She reminded me that SquareSpace templates are already “designed” and the typefaces and sizes are not arbitrary. Just because I could change them easily didn’t mean I should. “Trust the design,” she said. After her advice, I stopped wasting my time, thinking I needed to “customize” my site so it wouldn’t look generic. I realized that my images and text would make it my own.

I did show the site to my designer friends for tweaking before it launched. I also hired design, editing and technical help to make small tweaks. I made sure every page was read by me and at least one other person to catch typos and inconsistencies.

So, I didn’t need a designer to build it, but designers helped get it right, at the end. The biggest benefit to using a good template is that I saved thousands by not having to hire a designer and a developer. And I really enjoyed the process of making it—a process I would have missed otherwise.

It was good for me to build it myself. It helped me define who I am and what I do. I came out in the end, feeling more confident and clear about myself as a writer and as a coach. You know you’re doing your promotion right when the work you need to do to build the site, write the press release or write your elevator speech also helps you grow as an artist.

What do you think was the most important step of your redesign process?

The most important step was the sweating it out on paper, thinking about it, hemming and hawing for two years about it, and having many conversations with designer colleagues. I lived with the conundrum until I finally felt ready to solve it. Then, the most important step was figuring out the site architecture, which came down to answering some tough questions: who’s my audience, what do I want people to do and to find easily on the site, what do you want my visitors to feel?

I asked these questions until little by little my incomplete answers kept building. So, by the time I was on SquareSpace and trying things out, all that hand wringing paid off.

Then, I had a designer/developer come in at the end. She reminded me about my vision when I forgot it and she helped refine the site architecture and fix some small design details. Then, my design colleagues gave it the once-over.

Sometimes website relaunches don’t accomplish everything we set out to do, because of time, money, resource, or limitations of the platform. Is there anything on your wish list for your site that will have to wait until later?

Believe it or not, the site is better than I imagined it could be. How often does that happen?! The site helps me remember who I am as a writer and what I do as a coach. In curating my work for the site, I was forced to look back and see how much I’ve done. In creating a page for the memoir I’m writing now, I made a placeholder for this new project to emerge. My events page, which now updates automatically, makes me want to keep scheduling events. In subtle ways, this site helped me grow as a my writer and that helped mend the split between the two sides of myself.

I’m excited to have people visit the site—it’s like when you’re happy to have people visit your new office. The site helps me be enthusiastic in the world and that’s probably that best thing you can say about any marketing effort. In the end, it’s how much it supports and inspires you to show up in a big way.

March 7, 2016

5 Steps to Great Cover Art

Artwork from Into the Nanten entry 204

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by author Jay Swanson (@jayonaboat).

Cover art will be the unifying example through this post, but let’s consider this “5 Steps to Commissioning Great Art” because, if you’re like me, perhaps cover art is only the beginning.

When I started developing Into the Nanten, the world’s first real-time fantasy blog, I knew that artwork would be an intrinsic component. Thankfully by this point I had a solid track record with some amazing talent, but the road there wasn’t without its bumps. I can’t honestly say that I handled every transaction with the grace and poise I should have possessed along the way.

If you follow these five steps to commissioning great cover art, you’ll not only wind up with a piece of art of which you can be proud, but you’ll also keep yourself from damaging relationships that you will want to last you a lifetime.

1. Research Your Artist

If you read my post on five steps to creating a great audiobook, then this first part will sound eerily familiar: figure out what you want before you actually reach out to any artists. This is important for a number of reasons:

If you don’t have anything in mind, you’ll have no direction to give. This means you’ll wind up with something totally random. That might work for you, but it won’t resonate with your vision of the book, and the finished product may very well displease you once you have it. And you’ll still have to pay for it.

Just because you do have something in mind doesn’t mean any artist can do it. Many illustrators and painters are versatile in their styles, but few can do everything, and all of them have their strengths and weaknesses. Knowing what you want keeps you from setting your artist up for failure.

You might find your inspiration by doing the research.

The cover of my fourth book, Dark Horse, (illustrated by the amazing Marie Bergeron) was actually inspired when I stumbled across a painting by an entirely different artist, Russ Mills. The fractured mess of his style and stark contrast of black on white spawned a storm of ideas that led me to what you now see in the cover.

Once you know what you want, it hones you in on what you’re looking for stylistically. For Dark Horse I knew I wanted someone who could replicate Mills’s messy style—someone with a grasp of sharp contrasts and proper use of negative space. Marie stood out in that search, and she did not disappoint.

Cover artwork for Dark Horse

This is the time to ask questions about what style you want. Do you want it to be clean? Photorealistic? Abstract? Knowing if there’s a lot of blood-spraying action or if you’re just trying to capture a quiet meadow with happy flowers affects everything.

As for Nimit Malavia, the genius behind the illustrations for Into the Nanten, I knew from the first time I saw his art that I wanted to work with him on something massive. I was lucky enough to wrangle him into doing the cover for my third book, but it was his distinctive sketchbook style that I really wanted to pull into my world. As luck would have it, I would get the chance.

Artwork for Into the Nanten entry 336

2. Reach Out to Your Artist

Once you know what it is you want as far as style—and hopefully content—goes, it’s time to reach out to your artist. I suggest doing this in two phases.

Phase 1: Introduce Yourself by Email

When you send your first email to your prospective artist, there are some do’s and don’ts that I’ll claim are hard-and-fast rules (feel free to disagree as you wish):

Be concise

Be friendly

Briefly explain the project (and pitch it with passion)

Include a deadline

Tell them your budget

Be concise. Concise.

If you’re reaching out to more than one artist, tell them that, so there’s no confusion when they respond two weeks too late and you’ve already moved forward with someone else. If you can’t imagine any other artist in the world with whom you’d like to work, say so, but do it in the least stalker-creep way possible.

Don’t explain the entirety of your project up front, don’t ask them to work for free, don’t assume they’re dying to work with you, and don’t expect them to read your book. Don’t be stingy on your budget; money is going to come up, and it’s going to determine whether your artist can work with you. They are running a business after all, so cut to the point and tell them what you can afford. Let them know you’d like to negotiate if you need to, but remember that you get what you pay for.

Phase 2: Pitch Your Idea

Let’s say you hear back from an artist with whom you’d like to work and they tell you that they’re on board and can even work within the budget you set. Great. Now’s the time to inundate them with material.

Wait wait wait. Take two steps back and hold on a second.

This doesn’t mean you can send them a copy of your book and ask them to draw their own inspiration from their favorite part (unless you want to pay them for the time it takes to read your book). It also doesn’t mean that they need to know backstory, or about the world at large, or what kind of pie your protagonist prefers (unless they’re eating pie on the cover you have in mind—then by all means).

What you want to give them is strictly relevant information. If it has a direct impact on or appearance in the scene, hand it over. From the practical (do you need them to do the title work for you?) to the intangible (do you want the book to communicate joy, fear, intrigue, or what other emotion?) (Your book should always convey something intrinsic to the book on an emotional level.)

Describe the scene with as much detail as you have in mind—at the very least, give them the details that matter. Hair/skin/eye color, the style of sword, the type of flowers in the meadow, or (if we’re writing romance novels here) the percentage of pec you want visible on your male love interest.

I can draw a little, so that tends to be useful. For my book Shadows of the Highridge, I knew I wanted a dark mountain scene with one of the protagonists huddled alone, scared, and bleeding on an isolated pile of rocks. The idea morphed over time, but you can see one of my early sketches here and how it was translated in the end.

Cover art progression for Shadows of the Highridge from sketch to finished product

It wasn’t just the sketch that did it though. I clearly communicated what I wanted in the lighting (two moons), the colors, and the atmosphere as well. Which leads us to the most important foundational aspect of this whole process.

3. Communicate Communicate Communicate with Your Artist—Then TRUST Your Artist

Something you should be aware of is that you are able and encouraged to give feedback to your artist. They want to make sure you wind up with something of which you will be proud—and so do you. The final yea or nay will be on you. If you’re having a difficult time articulating your thoughts, wait until you can. Sometimes it takes a few days or even a week to figure out what it is that’s bothering you about a piece. Sometimes you need to borrow another set of eyes to figure it out.

I always show the iterations of my art to an artistically inclined friend or family member during the process because often I’m too close to see what’s wrong. Once I’ve figured out what needs alteration, I put it into words and do my best to communicate clearly.

The flipside is that you shouldn’t expect more than a few minor changes along the way. You also need to trust your artist. Let me say that again.

TRUST YOUR ARTIST.

This is why doing the research is so important. If you love their style, if they’ve produced works of art that move you and that you wish were a part of your very soul, then you need to trust them to bring that skill to the table.

This can be said another way before we move on: don’t micromanage your artist.

Ideally, said artist will send you some quick rough sketches to get the major things right at first—composition, angle, and all of the necessary components. You can go back and forth as many times as it takes to get this part right, but you still want to do your best to communicate as clearly as possible to keep this stage short. (I was so excited with the pencil work by Marjolein Caljouw for my first book that I almost dropped the whole process and took it as it was from the first glance.)

Cover art progression for White Shores from sketch to finished product

Once you okay your rough, you’re going to wind up with something that’s 80 to 90 percent finished a few days-to-weeks later. Major changes will take more time (and may cost you more money). The speed and process will depend on the artist, as will the level of patience for your nitpicking. They may give you more opportunities to check in along the way, or they may drop something practically finished in your lap. Either way, keep your changes as specific as possible to avoid wasting time.

In the video above you can see a lot of changes that I requested Nimit make, largely with the shape and style of the helmet. The wings on the sides underwent a lot of iterations, as did the shape of the visor. The end result was something with which we were both really happy.

After you receive something near-finished, you’re going to be giving them requests that align more with polish. Do you need a shift in the color palette? Perhaps you don’t like the way the light strikes the protagonist’s face, or there’s not enough space left for the title you intended to use.

As a rule of thumb I’d say you can go back to the artist with two rounds of requests at this level, and no more. This is a personal challenge on your side: to really know what it is that you want and help guide your artist there as directly as possible. It’s worth it because (a) you’ll get what you want quicker, and (b) they’ll probably be more likely to want to work with you in the future.

Here’s my guiding principle in approaching new art: What emotion am I trying to elicit, and does this image do it?

4. Pay Your Artist Well

You know what also encourages artists to look forward to repeat business from you? Paying them well.

If you treat your artist with dignity and respect, as the creative professional they are, you’ll be off to a better start than most people out there commissioning artwork. If you pay them well and don’t gripe about the fact that you’re actually paying for art (shouldn’t they just do it for the sake of the art?), then you’ll be leagues ahead.

Here’s a loose pricing chart to get your expectations aligned with reality before you approach any artists and offer them peanuts (all of these prices depend largely on the experience and prestige of the artist):

Journal/sketchbook style illustrations: $80–$150

Simple but polished cover: $400–$800

Polished, highly detailed cover: $800–$1,500

Polished cover from famous artist: $5,000 to the moon

These prices can vary widely based on a number of factors, including where the artist is at in their career, demand for their work, their work/life circumstances, and what kind of relationship you have with them already. Even the type of project you’re bringing them in for can have an effect, so keep that in mind.

This is also all in reference to original illustration-based artwork. There are plenty of sites out there that will direct you to cover designers who specialize in photo and text-based cover art, or traditional graphic design. Many produce these covers in batch, allowing you to browse and select from pre-designed artwork. If you find one you love, this can be a great way to go, and unless you’re buying something pre-made, these principles all still apply.

You will get what you pay for, but at the same time you need to get what makes you happy. If you’re proud of your cover art, you’re more likely to pump your own work and share it like crazy. So don’t let me or anyone else dictate to you what’s good enough.

If you love it, go for it.

5. Give Your Artist the Recognition They Deserve

For Shadows of the Highridge I did something I had never done before: I hired a cover designer as well as an illustrator. Andreas Rocha did the artwork, and then J. Caleb Clark came along and asked for a shot at the cover design. I had never bothered to hire anyone for this component, having always done it myself (see below, the left side), and immediately regretted my hubris once Clark sent me his rendition (the right side).

The two front cover designs for Shadows of the Highridge

The two back cover designs for Shadows of the Highridge

He made Shadows look professional. He knew what he was doing, and I’ll never go without his help again.

This brings me to the final point, which is to give credit where credit is due. On my website I have a page dedicated entirely to the artists, narrators, and editors that I’ve worked with over the years.

I have an Instagram account (@mindofjayswanson) where you can scroll through all of the artwork from Into the Nanten, my book covers, maps, and more. I tag each artist in their work and try to redirect praise to their accounts in comments. And I try to pump them everywhere I go because their success is mine, and vice versa. The only one I missed in this article was Sam Spratt, who is as professional as he is talented. Go hire him if you can break into his insane schedule.

If art is an investment in your business, strong relationships and the success of your artists are investments in your future. There are no guarantees that they’ll even like you in the end, but if you do your best to work well with them and pump them everywhere you can and the day comes that they become super out-of-your-league famous, they may grandfather you in on your old prices because darned if they don’t want to work with you again.

And isn’t that a great goal? To build relationships along with works of art? Personally, I think it is.

If this has got you pumped up on art, you should check out the Kickstarter we just launched for Into the Nanten! There’s tons of art up for grabs as well as some truly unique items you’ll find nowhere else.

March 5, 2016

I’m Starting Official (Free!) Office Hours

When I was still working at F+W, I avidly followed Jason Fried and his company 37 Signals. I admired the company culture I read about, as well as the business advice that I gleaned from their blog. (If you’re curious, Fried has co-authored a book, Rework, that imparts his philosophy.)

In 2009, Fried launched what he called “CEO Office Hours.” I thought the idea was ingenious and lovely, but I didn’t see a good way to incorporate that idea into my career at the time.

I’m finally returning to that concept and launching monthly office hours via Facebook. Why Facebook?

Facebook recently rolled out a feature that allows you to host live video on your Facebook page. (Note: This feature isn’t yet available to personal profiles unless Facebook verifies you as a public figure.) If you’ve ever used Periscope, it’s similar to that.

The No. 1 source of social media traffic to my site is from Facebook, and it’s generally where I have the most conversations and engagement with authors.

Most people are familiar with the Facebook interface; it doesn’t require any special software, tools, or knowledge to watch or join me for a live video. There’s no limit to how many people can watch.

People watching the live video can comment and participate easily through Facebook, on whatever device they happen to be using.

My first office hour dates are:

Monday, March 14, 7 p.m. ET

Monday, April 11, 7 p.m. ET

Monday, May 9, 7 p.m. ET

Monday, June 13, 7 p.m. ET

For each session, I’ll be available and taking questions on my Facebook page for one hour or thereabouts. You don’t have to be my friend or follow me to watch—anyone who has a Facebook account and is logged in will be able to see the video. For those who aren’t available to join live, the video is automatically recorded and publicly available through my Facebook page.

I hope to see you there!

March 3, 2016

Why You Should Join All Social Media Networks

I think it’s fair to say that most of us are not looking to add more social media activity to our lives. In fact, we prefer to trim online activity or drop entire networks if possible.

So the advice I’m about to offer may feel objectionable and time-wasting at first, but if you stay with me until the end, you may find wisdom in what I’m advocating.

I recommend that as soon as you find out about a new social media service, join it.

It’s not necessary to conduct much research on the service or even learn how to use it—not at first. (And let’s assume you’ve heard about the social network from a reputable source or someone you trust.)

Here’s what you should do; it’s about a 10- or 15-minute commitment.

Create a username, account name, or profile URL using the name you publish under—or intend to publish under. Hopefully you’ve been consistent about what usernames you have on social media. For instance, no matter where you find me online, my handle is always the same, “janefriedman” or a display name of “Jane Friedman.”

Add a link to your website in your profile. (Almost every social network allows you to add a link to your website, so do it.)

Complete the profile information to whatever level you feel comfortable. You can copy and paste in your standard bio from another social media site if appropriate.

Quickly see if there’s anyone else you know using the platform; consider following/friending.

Add a brief post of some kind; experiment for roughly 5 minutes with using the network.

Then you’re done. You never have to go back, until you feel curious or motivated to do so.

Here are the benefits to completing this process:

You’re laying claim to the best (or a better) username or handle for yourself.

By being an early adopter, you gain the benefit of being “found” by the hundreds or thousands who join the network after you, looking for people they already know on the network. (See #4 above.) On some networks, new users may automatically friend/follow people they’re friends with elsewhere. That means if/when you return to the network at a future date, you have a built-in following you didn’t have to work for.

You’re linking to your website and creating a profile that may surface when people search for your name. If the social network becomes big and important, or influential in terms of SEO (search engine optimization), you’ve just created a useful social signal that helps search engines (and others) better identify who you are and understand what work you produce.

You don’t have to be active on the social network in order to reap the above benefits.

What are the drawbacks to this process? You’ve got an account out there that may be largely inactive. Some people advocate against this for security reasons, but based on my experience, there’s little to no repercussion. Use a strong and unique password, sign up for weekly email alerts to inform you of any account activity, and generally you’ll be fine.

When I signed up for Facebook (in 2006) and Twitter (in 2008), I didn’t find much to do (or much activity overall). Not enough people were there, neither were yet seen as professional marketing channels, and you couldn’t even advertise. But I still signed up, created a page, and every once in a while returned. Eventually, I started using both networks when they became interesting to me, and my friends and colleagues were there.

Right now, I have accounts at many social media networks, including Pinterest, Tumblr, Snapchat, Peach, and the List App. But I’m not very active on any of them. Maybe one day I will be, and if so, my account is ready and waiting, with a baseline of followers and friends I can build from.

Related: SEO and Fiction Writers—check out some excellent advice from marketer Pete McCarthy.

March 2, 2016

Writing Fiction: Does It Feel Indulgent?

In the literary fiction world especially, it’s often taken as an article of faith that writing is an intrinsically important activity to be engaged in. So when writer David Mizner (@DavidMizner) challenged this view at a writing workshop, he was taken to task for it:

When I was twenty-nine, shortly after I started writing fiction, I went to a two-day workshop. The first night, a group of writers—including an accomplished or at least published novelist (I forget who it was; I’m not choosing not to name him)—were sitting around talking about the “writing life.” Loose after a few drinks, I asked them if they ever questioned the value of writing fiction. “It feels indulgent,” I said. There was an awkward silence, as if I’d said something borderline racist or taken off my pants. Finally, the published author suggested that I might not have the stuff to be a fiction writer.

Mizner goes on to discuss his ambivalence about fiction writing, which is partly tied to fiction possibly being less relevant and powerful in today’s culture. Read the full piece over at Glimmer Train’s site.

Also at Glimmer Train this month:

Building a Collection by Christine Grace

Bob Shacochis interview

Why Write Characters of Color? by Lillian Li

March 1, 2016

A Warning About Writing Novels That Ride the News Cycle

by m01229 | via Flickr

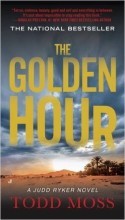

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is from Todd Moss (@ToddJMoss), author of a thriller series featuring State Department diplomat Judd Ryker.

My first book contract was a fluke of good timing. Al-Qaeda, Muammar Gaddafi, and French Special Forces are all, in part, responsible for my writing career. But I’ve since discovered that it’s risky, and probably unwise, for a novelist to chase current events too closely.

Let me explain. I left the State Department in late 2008 and wrote a thriller, The Golden Hour. It’s set in West Africa, where State Department crisis manager Judd Ryker fights to reverse a coup d’etat and save the US embassy from terrorist attack. The plot was inspired by a real coup in Mauritania, but I set the story in a neighboring country, Mali, on the assumption that more Americans would recognize Timbuktu than Nouakchott.

Let me explain. I left the State Department in late 2008 and wrote a thriller, The Golden Hour. It’s set in West Africa, where State Department crisis manager Judd Ryker fights to reverse a coup d’etat and save the US embassy from terrorist attack. The plot was inspired by a real coup in Mauritania, but I set the story in a neighboring country, Mali, on the assumption that more Americans would recognize Timbuktu than Nouakchott.

As I was finishing the manuscript and trying to find an agent, I caught a very lucky break: Mali had a real coup. In early 2012, the country’s president was overthrown by his own army, and the coup was immediately followed by an incursion from Libya by well-armed fighters who had lost their jobs after Gaddafi’s death. Al-Qaeda-aligned extremists then took advantage of the chaos and seized the northern half of Mali to create an Islamic caliphate the size of Texas in the middle of the Sahara Desert. A few months later, the French military invaded, pushing the radicals out.

I hadn’t predicted a coup or a war against jihadists in Mali, but it sure looked like I had.

The troubling chain of events in West Africa helped me because an agent, Josh Getzler of HSG Agency, watches BBC News before going to bed. One night, he was surprised to see French troops battling terrorists in the Sahara. He remembered he had recently received a query about a debut thriller remarkably similar to the events he was witnessing on his television. A few days later he offered to represent me, and within a few weeks he sold my novel to Putnam Books. The Golden Hour was published in September 2014.

When Putnam asked for three more books in the series, I tried to ride the news cycle again. Bad idea.

In my second novel, Minute Zero, the hero, Judd Ryker, lands in the southern African country of Zimbabwe just as an aging dictator is clinging to power in a chaotic election. The story was inspired by a real-life election in that country in 2008, when a then eighty-six-year-old Robert Mugabe “won” re-election via cheating and intimidation. As I laid out the plot on my kitchen table in the late spring of 2013, in the back of my mind I was anticipating that Zimbabwe might be in the news by the time the book was published. Perhaps Mugabe might even be gone?

Minute Zero was published in September 2015. For those of you not closely following obscure world politics, Mugabe is still in charge. He celebrated his ninety-second birthday last month, and he’s planning to run again (!) in 2018. I haven’t given up yet that Zimbabwe could still hit the news, but the timing of Minute Zero is looking less prophetic and more like wishful thinking.

In the spring of 2014, I sat down to decide where to set book three in the Ryker series. I wanted a country ripe for major political change and a place Americans have a strong interest.

Cuba was perfect. I laid out a detailed plot for Ghosts of Havana, which opens with four dads from suburban Maryland fishing off the coast of Florida when they’re captured by the Cuban navy. Judd Ryker is sent to Havana to negotiate their release, but he discovers his mission is a smokescreen for secret talks to find a breakthrough with the Cuban government.

Cuba was perfect. I laid out a detailed plot for Ghosts of Havana, which opens with four dads from suburban Maryland fishing off the coast of Florida when they’re captured by the Cuban navy. Judd Ryker is sent to Havana to negotiate their release, but he discovers his mission is a smokescreen for secret talks to find a breakthrough with the Cuban government.

I was halfway through the first draft when, in December 2014, President Obama announced surprise plans to normalize relations with Cuba. The White House revealed that the half-century-long diplomatic logjam was broken during secret talks.

As with Mali, I was as surprised as anyone. I didn’t have any inside information, and I haven’t had top-secret security clearance since I left government. But I quickly had to adjust my book plot to accommodate this breaking news. As Cuba policy has sped along—embassies reopened, travel barriers reduced, the Pope’s arrival, and now a Presidential visit next month—I’ve been playing catch-up in the final revisions.

On one level, it’s fantastic that Cuba is all over the news. Yet Ghosts of Havana won’t be released until September. If Minute Zero looks like it came out too soon for the news cycle, Ghosts of Havana might be too late.

Reflecting on all of this, and thinking about writing realistic contemporary thrillers in the future, I’ve drawn a few conclusions.

Remember that timeless beats timely. It’s probably best to use a topic or location that will be in the news regularly and often, rather than a one-time flash that requires luck to align with your release date. I like to believe that setting a thriller in a place like Mali or Zimbabwe is unique, but it also could limit your audience. I’m still searching for just the right balance between originality and familiarity.

Anticipate the pivot. The world is unpredictable. But when I’m outlining a novel, I now try to imagine how potential world events might affect the plot and the book’s long-term relevance.

Plan for long lead time. From initial outlining of the story to release date is twenty-four to thirty months for me. This includes nearly six months at the end when the book is locked down and few changes can be made. I’m just now, in March 2016, starting to think about a plot for a thriller that won’t be out before September 2018. Who knows what the world will look like by then?

I’ll continue to write thrillers set in unusual places and tackle topics I hope will grab people’s attention. “Ripped from the headlines” is still the dream. But I now anticipate the news cycle with extreme caution.

February 25, 2016

The Author Website: Your Central Marketing Hub

Earlier this week, I wrote a column for Writer Unboxed, where I discussed the primary function and value of an author website, which is marketing related.

Yet many authors ask me questions that indicate they plan to focus on their website as a publishing tool—and they wonder if that’s OK. My response:

Sure, posting content you own at your website is OK. But why do it?

What do you gain by posting your book, in part or in its entirety, on your website?

How will anyone know it’s there?

Why will anyone want to read it on your website?

What are you trying to accomplish by putting it on your site and not publishing it through the biggest retailer of ebooks (Amazon)?

Read the full column over at Writer Unboxed, where there’s already an active discussion in the comments.

February 24, 2016

5 On: Barry Eisler

In this 5 On interview with author Barry Eisler (@BarryEisler): the pros and cons (where they exist) of legacy, Amazon, and self-publishing; notes on research and editing; selling book rights; and more.

Barry Eisler spent three years in a covert position with the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, then worked as a technology lawyer and startup executive in Silicon Valley and Japan, earning his black belt at the Kodokan International Judo Center along the way. Eisler’s bestselling thrillers have won the Barry Award and the Gumshoe Award for best thriller of the year, have been included in numerous “best of” lists, and have been translated into nearly twenty languages. Eisler lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and, when he’s not writing novels, he blogs about torture, civil liberties, and the rule of law.

5 on Writing

CHRIS JANE: When you started writing A Clean Kill in Tokyo (previously Rain Fall), you didn’t really know how to construct a book, you’ve said, but you had a talent for writing. How/when did you first become aware of that talent (did you enjoy writing essays in high school? work on short stories in your spare time?), and what were some of your earliest creative writing projects?

BARRY EISLER: I’ve always enjoyed writing, starting with short stories about vampires and werewolves when I was a kid (fortunately, these are no longer extant). But I don’t think I conceived of it at the time as a talent—more just something I enjoyed. In retrospect, I wish I’d recognized sooner that this thing I enjoyed and seemed to be good at was in fact a kind of talent—I might have gravitated to a career in writing instead of spending time in intelligence, law, and business, none of which was as fulfilling a fit for me.

Though I guess that unplanned, meandering path has led to a pretty good place.

If only one of your existing works of fiction and one of nonfiction were allowed to remain while the rest of your writing was destroyed forever, what would you save?

Whoa, you are a cruel interviewer!

For nonfiction, it’s a little easier, with two blog posts I particularly enjoyed writing. First, “The Definition of Insanity,” about the neurotic devotion to war that characterizes a certain class of deranged former intelligence officer along with our Very Serious press corps; second, “It’s Just a Leak,” which reads almost like a short story and exposes some of the government’s propaganda techniques (in this case, describing an undersea oil eruption as a “leak”).

Well, okay, I’m also kind of fond of my essay, “Authors Guild and Authors United are such a pernicious joke, and other such activities.

Beyond which, self-publishing and Amazon Publishing have introduced the first real competition the New York Big Five has ever seen. This moribund, hidebound, incestuous industry badly needed a shakeup, and the good news is, it’s getting one! Compared to all that, I doubt any imprint of mine would add very much.

Thank you, Barry.

February 23, 2016

A Former Book Publicist’s Advice to Traditionally Published Authors

by Matt Biddulph| via Flickr

Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is from Andrea Dunlop (@andrea_dunlop), formerly a publicist at Doubleday, and now the executive director of social media and marketing at Girl Friday Productions.

I wasn’t the first aspiring writer to move to New York to work in book publishing in the hopes it would make my dreams of becoming an author myself come true. Exactly how labyrinthine the path would be (just three agents, a round of MFA applications, and a cross-country move later) was a bit of a surprise, but everything I learned in my first real job as a publicist at Doubleday—as well as what I learn every day in my current gig as the social media and marketing director at Girl Friday Productions—has prepared me exceptionally well for the launch of my debut novel this month.

Being a book publicist can be an absolute blast at its best: when you work with kind, grateful authors and you’re able to secure all the media coverage you were hoping for and it’s all positive and everyone is delighted. I probably don’t need to tell you this isn’t the norm. Many of the authors I worked with at Doubleday were lovely, but trying to secure coverage for their books—even with the venerable Doubleday behind them—was an uphill battle. This was in the mid-aughts, when the media market was shrinking dramatically, standalone book sections were disappearing (RIP Washington Post Book World), and the number of titles being pitched to the same tiny handful of outlets was exploding. In my final year in New York (2009), the economy tanked, Doubleday was folded into Knopf, and layoffs ensued. Those who remained saw their workloads double (but not their salaries, natch). The pace of change in the industry has only sped up since then.

Now, all these years later, my own novel is hitting shelves (Losing the Light, from Atria) and I am feeling that signature mix of terror and joy I’ve seen in the eyes of so many over the years. Here’s what I’ve learned along the way.

Now, all these years later, my own novel is hitting shelves (Losing the Light, from Atria) and I am feeling that signature mix of terror and joy I’ve seen in the eyes of so many over the years. Here’s what I’ve learned along the way.

Do Unto Your Publicist …

Many authors do not understand their true relationship to their publisher’s publicity team, thinking that those in-house work for them, which is not the case. This can result in some outlandishly entitled behavior. Oh, the tantrums I’ve seen! You would imagine that the authors who berated me when I was a publicist did so because their campaigns went badly, and you would be wrong. Some authors were impossible to please.

Now, we were professionals at Doubleday; we did our jobs well irrespective of authorial shenanigans. But we answered to the publisher, and the publisher wanted to sell books. But. There were authors who made me cry and authors who sent me flowers. Who do you think I went the extra mile for? Turns out publicists are human. So is everyone else who is working on your book. Publishing folks, by and large, are good, smart, passionate book-loving people—not to mention often young, underpaid, and living in one of the world’s most expensive cities. An author’s role is to be their teammate, not their taskmaster. And bully the assistants at your peril—they’ll be running things sooner than you think.

Show Up for Your Book

When I was at Doubleday, there was the occasional mention of blogging or tweeting, but social media was nowhere near as ubiquitous or as powerful as it is today. In my current role at Girl Friday, I sometimes hear people complain about “having” to promote their own work. No. You get to promote your own work now.

What has always been true is that authors need to care about their books way more than anyone else involved. What’s true now is that you don’t have to so much as leave your couch to help your cause. Get your head around social media, web analytics, bloggers, all of it—there are a million resources out there to help you help yourself, and there’s no excuse for you not to be an integral part of your book’s promotion.

What broke my heart far more than the meanie authors were the nice ones who wrote beautiful, worthy books that, for whatever reason, just slipped beneath the waves with nary a splash. This fate was the most terrifying prospect of all. What if I did all that work, suffered all the slings and arrows of years of rejection, only to finally get a book published and have it met by utter silence? It was awful, watching these books die on the vine.

That never has to be you. If your book has an audience (and if a publisher bought it, it likely does), you have all the tools at your disposal to reach them. I’m not saying this doesn’t take a lot of work and some expertise, but these things are available to you. There will never be nothing you can do.

Part of the reason I stopped working on publicity campaigns for authors was because it was so impossible to promise authors that there would be a return on their investment. I could hustle, I could pitch, I could, in essence, try, but the decisions were always up to the members of the media who I was pitching. But with savvy use of social media (especially the paid features, which are, in Facebook’s case, mind-blowingly sophisticated), you will always see some results. They may not be exactly the results you hoped for, but they will be something you can build on over time, which is crucial if you want being an author to be a lifelong enterprise, as most of us do.

Get the Help You Need

Showing up for your book doesn’t mean doing everything yourself. Getting in an entrepreneurial mindset is key. If you were starting a business, you’d likely hire a team of folks to help: a lawyer, an accountant, and so on. This is something successful self-published authors are savvy about by necessity. Know what you want and decide who you’ll need to help you get there.

For my debut novel, I hired a publicist, not because I didn’t trust my in-house team—who have all been enthusiastic, supportive, and highly competent—but because I know I have especially big goals. I hired Booksparks, who came recommended to me by other authors from Atria, and I couldn’t be happier with the results: they’ve worked seamlessly with my in-house team and been a delight throughout the process.

Such referrals are one of the many ways in which your fellow authors will be your best resource. Developing this community by reading other contemporary books in your genre, promoting those books on your own social media, and connecting with those folks (in that order, please) is one of the best things you can do to set yourself up for success. Not to mention that this is the most fun part of the whole process. You waited all your life to be in this club, so enjoy getting to know the other members.

Because I no longer work in-house, I can tell you everything I wish I could have been more blunt about when I was a publicist. Understand what you’re up against, because the odds are not going to be in your favor, but the landscape—at least for the motivated author—definitely is. Be your book’s biggest champion, get creative about your promotion, and never, ever make your publicist cry.

For more from Andrea Dunlop, check out her contributions to the Girl Friday Productions blog.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers