Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 361

October 14, 2015

Geonotating Interplaces

Jose Rivera participates on SoundCloud under the name Proxemia. A graduate student at MIT, he studies “sound art, geonotational mapping, location recording, experimental music,” and posts audio from his various excursions. One recent track of Rivera’s is “interplace,” a highly detailed sequence of largely drone- and rattle-rich “location recordings,” in his terminology. The phrase suggests something distinct from field recordings, perhaps — something with a more precise sense of position and place. A brief liner note explains that it’s a “composition experiment” for what appears to be the Sensory Ethnography Lab at neighboring Harvard. The lab “promotes innovative combinations of aesthetics and ethnography,” and is run by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ernst Karel. Past geonotational efforts by Rivera have included audio-visual documentation of natural and industrial spots in Asheville, North Carolina (which surface in a Disquiet Junto project), among other places.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/proxemia. More from Rivera/Proxemia at proxemiasound.net.

October 13, 2015

Lee Ranaldo + Christian Marclay

The Important Records label has been steadily uploading archival material from past releases to its SoundCloud page, such as this eight-minute stretch of a quiet quartet led by guitarist Lee Ranaldo, best known as a member of Sonic Youth. The track dates from 2008 and features Alan Licht on guitar, Christian Marclay on turntables, and William Hooker on drums. Marclay’s playing is especially syrupy and lovely, less hard-edged cut’n’paste than a soft, warbling interplay between source material, as he’s constantly slowing the vinyl in a way that makes the music sounds like it’s melting. The parallel brings to mind Salvador Dalí’s bowed clocks as much as it does Kid Koala’s sad-toned, downtempo beatcraft.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/importantrecords. More on the original release at importantrecords.com. More from Ranaldo at leeranaldo.com.

What Sound Looks Like

I rent a small office. In the morning it takes me about half an hour to walk to the office from my home. This commute is a modest version of a fantasy I have long harbored — not so much a fantasy as a scenario, and it’s probably not really even me in the scenario. It’s someone older, less social, more focused. I think this someone only writes fiction. I think. He has two homes. There’s a home where I live now, out in the Richmond District of San Francisco, and there’s another home deep downtown. I’d wake up — he’d wake up — in the morning, walk all the way downtown, which would take about an hour and a half, and then he’d write for the whole day. The next morning he’d wake downtown and walk all the way back to the Richmond District, where he’d begin writing again.

I’ve been in this new office for about two months, and the commute, the distance, the half-hour walk, has provided some of the structured reflection that the fictional scenario presupposes. One core component of the scenario isn’t just the distance, but how different are the two locations from each other. My half-hour walk doesn’t provide as much distance or difference, but it’s still re-orienting. Key among the office’s distinguishing characteristics are sonic ones. It has a carpeted floor, for one thing. And then there are the sounds from outside — church bells next door on the hour, the recess chatter at an elementary school just past the church, and the Tuesday noon civic warning siren.

There are a hundred-plus speakers spread around San Francisco that ring out with a test siren each Tuesday at noon — first the siren, then a male voice intoning in English (and in select neighborhoods in Spanish and Chinese) that this is only a test. Even with that many speakers, the majority of the citizens of this city hear the siren from some distance. Were there actually an alert, it would be louder and more insistent. As it turns out, the siren in my new work neighborhood is directly across the street from my building’s entrance. I had lunch earlier than usual today, and happened to walk right beside it as it rang out. Since I moved into the office I haven’t been sure where the siren is, until suddenly there it was, drawing attention to itself, high atop a massive pole in the middle of the street — loud as could be, telling us that all is well, at least for now. At home, the Tuesday noon siren is far more diffuse, to the extent that I hear several sirens at once, their relative proximity creating an echo effect, as if I live in a deep canyon when in fact I live on a high hill. At the office, the same siren is thundering and declarative, a forceful reassurance of the status quo.

An ongoing series cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.

October 11, 2015

Listeners on Listening

Steve Ashby, who teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University, recently asked me four questions about listening. Ashby is posing these same four questions to a variety of people. The questions are all about listening, and the answers are intended to inform a music-appreciation course that he teaches at VCU. As I worked on my responses to his questions I asked him some questions — yeah, interview an interviewer and you inevitably get interviewed back — for some background on his teaching. He explained:

I’ve noticed in the classes that I teach, as soon as I start playing a piece of music, say Mozart, Bach, what have you, the students’ attention drifts back to their phone, or other distraction. For all intents and purposes, making the music essentially white noise. … I thought maybe getting perspectives on listening from the music community might be useful. With a handful of perspectives from people in different realms of the music industry, we might be able to find a common thread that opens up new avenues of what it means to listen to music.

The first couple years teaching the course I followed the standard blueprint of an overview lecture through music history, from Chant to Stravinsky. Glazed over eyes, and too many PowerPoints, made me realize I need to rethink this. What’s the point of talking about specific music forms and terminology, when students’ ears aren’t tuned in or turned on to the sound surrounding them. Sounds and music outside of their comfort zone. As one of my guitar teachers used to say, you’ve got to create the space, before you can fill it.

Ashby also mentioned the musician Lawrence English, Simon Scott’s Below Sea Level album, the field recorder Gordon Hempton, and acoustic ecologist R. Murray Schafer as influences on his thinking, and in particular how a recent read of Peter Szendy’s Listen — this line in particular: “Can one make a listening listened to? Can I transmit my listening, unique as it is?” — had woken his ears to the sounds around him:

Bitten by the field recording bug, I began recording my walks to work, around town, outside my apartment, and noticed a big difference in what I heard at the time versus what was recorded. Remembering each step, but hearing my breath and surroundings differently. (The cicadas were loud this summer.)

Below are his four questions and my responses. If you’re interesting in participating, certainly feel free to in the comments below. Ashby has been part of the Guitar Faculty at Virginia Commonwealth University for a decade, and has taught music appreciation for nearly half of that.

1. You buy a new album. Describe your ritual/experience of its first listening.

I’m not sure I have a ritual, aside from listening to it as soon as possible. Most of the music I purchase I do so digitally, and when I purchase physical albums (CD, vinyl, cassette) I generally do so online. The latter often come with a download code, which means I have a digital copy before the physical copy even arrives in the mail. In fact, the most recent cassette tape I purchased — at a record store across town — came with a download code, and I downloaded it to my phone while taking the bus back home. Come to think of it, I only have a cassette player at my office, not at home, so it’s a darn good thing the cassette had that download code. Otherwise I would have had to wait a few days. Anyhow, I purchase music in such varied circumstances, I can’t say I have much of a ritual, again aside from listening to it as soon as possible. I will add that the more excited I am about a release, the more I try to diminish my expectations in advance of hitting the play button. One genre-specific ritual I have is that I listen to a lot of film music, and I try to listen to a movie’s score before I go to the theater to see it. A side note: I get an enormous amount of music for free, because I write about music and work with musicians, which means my inbox and my mailbox are inundated with, respectively, zip files and packages. I have music playing most of the day, less so in the evening. When I’m intrigued by a piece of music, I’ll often put it on repeat, sometimes for hours. The most extreme version of this is when I wrote my 33 1/3 book on Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume II, which took about a year, just about every day of which I listened to one track off the record over and over.

2. On subsequent listens to that same record, which aspects of the music do you focus your listening on. Does this change over time? How?

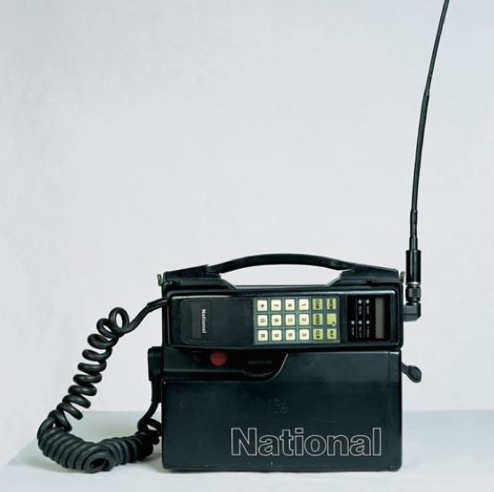

If there’s a track I like a lot at first, I’ll try to avoid it for awhile. After a few listens to an album, I’ll often put the album on shuffle, so I can listen to the tracks more remotely, more apart from each other. The biggest influence on how my listening changes over time is physical circumstances. I am amazed how different headphones, different speakers, different moods can change how a record sounds. (In the photo at the top of this post, the large black headphones are the ones I use at home, and the metal earbuds are the ones I use when I’m out and about. I also have some noise-canceling headphones for plane flights.)

3. If you could choose your favorite listening environment, what would it be? What draws you to that place to hear the music you’re listening to?

I like to listen to music in lots of different contexts. The primary places I listen to music are at my desk at home, at my desk at my office, in my living room at home, in my kitchen at home, while walking, and while on the bus. If I had to choose one favorite, it’d be wearing headphones while alone on the bus, enjoying the clarity that headphones provide, and the way music shapes everyday experience into a narrative. There’s nothing like taking a mundane bus trip while listening to a score fom a science fiction film or a thriller.

4. How does one make their listening listened to?

To take a step back, I should clarify my sense of the word “listening,” because it happens to be a word I use a lot. I teach a course on the role of sound in the media landscape at an art school, and I spend the first three weeks of the 15-week course discussing listening. To me, listening, clearly, applies broadly to the everyday experience of being in the world, of hearing the world. In fact, it’s hard for me to separate that sense of the word from the more specific context we’re working with here, where we’re mostly talking about listening to music. That said, there is, I think, a helpful transition from the “active listening” that I think of in regard to everyday life, to listening to music. There are lots of ways to make one’s listening listened to. I’ll describe four here, the first three of which I participate in, and the last being one I like to observe.

A. Dorm Space: For me, the single best social scenario for listening to listening to music — when my listening was listened to — was back in college, and it’s probably not repeatable in my daily life as an adult. I had a single dorm room my junior and my senior year, and I was always listening to music when I was in it. It became my habit in senior year to just leave my door open, and invariably people would walk through the hallway, hear something, and come in. There were frequently two or more people in my room in addition to me, listening to whatever I was listening to, sometimes while I was doing my homework. I think my listening then was kind of “performative.” I would talk about what was playing, move back and forth between records. My dorm room was like the world’s smallest radio station, one that broadcast only a few feet beyond the station’s doorway.

B. Radio DJ: I also DJ’d in college, in the radio sense of the word “DJ,” and I think DJing in that radio sense of the word is a fine example of having your listening listened to. I had a jazz show that was pretty straightforward, and a classical show, which was a mix of contemporary music and ancient vocal music, and where the two things often met — Pauline Oliveros’s Deep Listening and Steve Reich’s Tehilim feel very comfortable next Byrd and Palestrina. I also did a more freeform show, which would broaden the classical material to add in pop and rock that smacked of minimalism: My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, Brian Eno’s solo ambient stuff, lots of Robert Fripp, Fela, King Sunny Ade, and so on. Making connections between those records, whether simply by playing them in sequence or commenting on them after one track ended and before the next began, was a way of putting those connections in the listener’s head as to what I heard in the music, what I was listening to, listening for, in the music.

C. Music Criticism: I have written about music since I was in high school, and I think of writing about music as a means to express what I hear. It’s the primary way that I express my listening. This is recursive. To write about music, I need to think about my own listening — I need to listen to my listening — and that reflection then becomes the raw material for what I write. The single best advice I ever got in regard to writing about music was to use the writing to help explain how to listen to the music — not that there’s necessarily one way to listen to a piece of music.

D. Music About Music: All bands, the saying goes, begin as cover bands. This isn’t to say that every band is literally a cover band, performing some other band’s songs. What it means is that all bands begin with their influences plainly apparent, perhaps as homage, often as denied imitation, and then the good ones proceed over time to develop their own identity. Much music is built from pre-existing sound: sample-based hip-hop, quotations in jazz, electronic music that employs field recordings and presets (presets being audio and other tools that come as part of digital instruments). Just because the source audio remains evident in some of this work doesn’t mean that the artist has not fully consumed the material. But stepping back from even the most artfully assembled piece, like Steve Reich’s “It’s Gonna Rain” or the Dust Brothers’ production of the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, one has the opportunity to hear how the musicians hear, what it is they listen for, what sorts of sounds register with their ears and align with their creative impulses. If you listen closely to their acts of sampling you can listen to them listening.

October 9, 2015

A Map Is a Composition / A Composition Is a Map

Kate Carr, who travels widely and records as she goes, is employing sound as a mapping tool. Or perhaps a better way to put it is that she is employing a map as a compositional tool.

This half-hour track is an experiment of hers. As I understand it, roughly each three minutes marks one of 10 sites along a path of a mountain in Spain. The sound isn’t pure field recording — or it doesn’t appear to be. There seem to be edits and treatments, but perhaps the sound in the Spanish countryside is simply that surreal. There is muted singing, too — perhaps Carr in duet with the world.

She writes of the piece, which is titled “From a wind turbine to vultures (a sonic transect of a small mountain in Velez Rubio, Spain),”

This is an idea I have been working on for a while. It involves the sonic investigation of 10 sites along a sonic transect. These sites were evenly spaced along a straight line up a small mountain in a remote area in Spain. The wind turbine in the title was in the valley of the mountain, the vulture at the peak. This is just a testing out of this idea.

She also mentions that the individual sites are noted in the track’s comments — signposts along the audio timeline — but they don’t appear to have gone live yet. (Update 2015.10.10: The sites are now visible in the comments at the track’s SoundCloud page: 0:05, 7:59, 11:32, 15:07, 17:14, 20:04, 21:43, 23:25, 25:37, 28:36.) The audio was uploaded earlier today.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/katecarr. More from Carr at katecarr.bandcamp.com, gleamingsilverribbon.com, and twitter.com/flamingpines.

Modular Synth Status

Status report on my slowly evolving modular synthesizer. I’ve added the red thing in the lower left, which is a VCA mixer (details at the manufacturer, addacsystem.com). There’s an alternate version of the same item with a black faceplate, which I would have preferred, but black was an additional fee, and I’ve been trying to do this all with second-hand modules. In overly simplified terms this VCA (that’s “voltage controlled amplifier”) mixer means that I can vary the relative volume of five different channels, like have five different tweaks of the same sine wave, and move between various combinations and permutations. I think next up — to fill those dark voids — are a colored-noise source (white, brown, pink) and another VCO. After that, I’m not sure. Input is always appreciated, if you’re reading this and happen to be knowledgeable about such things. The above image is not a photo but a simulacrum from the database at modulargrid.net.

October 8, 2015

Disquiet Junto Project 0197: Earliest Polyphony

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group on SoundCloud.com and at disquiet.com/junto, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate.

This assignment was made in the early evening, California time, on Thursday, October 8, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, October 12, 2015.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0197: Earliest Polyphony

Sight-read newly uncovered choral music from the 10th century.

Thanks to Matthew Dean (m-68.com), among others, for encouraging this project.

Step 1: Perhaps you’ve read the news about a newly uncovered piece of music, dating back to the 10th century, that is believed to be the earliest known piece of polyphonic music. You can check it out here:

http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/ea...

Step 2: Review the notation in the article (and pictured on this project page on Disquiet.com).

Step 3: Record your own interpretation of the music. (You don’t have to sing it.)

Step 4: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

Deadline: This assignment was made in the evening, California time, on Thursday, October 8, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, October 12, 2015.

Length: The length of your finished work should be as long as you see fit.

Upload: Please when posting your track on SoundCloud, only upload one track for this assignment, and be sure to include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Title/Tag: When adding your track to the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com, please include the term “disquiet0197-earlypolyphony” in the title of your track, and as a tag for your track.

Download: It is preferable that your track is set as downloadable, and that it allows for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

More on this 197th Disquiet Junto project (“Sight-read newly uncovered choral music from the 10th century”) at:

http://disquiet.com/2015/10/08/disqui...

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

Join the Disquiet Junto at:

http://soundcloud.com/groups/disquiet...

Disquiet Junto general discussion takes place at:

More on the source material for this project at:

This Week in Sound: Bike Music + Ancient Acoustic Tiles +

A lightly annotated clipping service:

Bicycle Built for Tunes: We get the quarterly publication of the Historic New Orleans Collection as a reminder of our four years in New Orleans, from 1999 to 2003. The Fall 2015 issue lists recent acquisitions, among them some “bicycle sheet music.” A description by Robert Ticknor connects the rise of the bicycle in the latter half of the 1900s and the pre-radio era of popular music: “During this time, before the advent of radio, sheet music was a common means of bringing popular song into the American home. The recent acquisition of 18 pieces of bicycle-themed sheet music shows how the two trends merged for a short time around the turn of the century. With titles such as ‘The Pretty Little Scorcher’ and ‘The Crackajack March and Two Step,’ these songs often praised the healthful pleasures and independence of bicycle riding. The cyclist’s life, as depicted in ‘The Wheelman’s Song,’ is ‘one unfading spring /Green and blooming till its close.'” There’s a beautiful shot, as well, of “Cycle Polka.” You can read the full piece on page 20 of the freely downloadable PDF of the issue at hnoc.org.

If These Halls Had Ears: Blogging platforms are paved with two- or three-post websites that start off with good intentions and then end so prematurely that it’s as if they barely ever began. But good intentions are reason enough to cue up fromthesoundup.tumblr.com, which promises a tour of great European concert halls as experienced from the perspective of a student of acoustics. The first stop takes us to the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, described as “essentially a big, minimally ornamented box.” The entry explores the unique characteristics of the hall — what makes it different from other, more recent box halls, as pictured above — and asks questions about its presumed superiority: “Should the acoustics privilege one type of music at the expense of others?” There also two prior entries, one a busker’s perspective on the subway as a performance venue, and another announcing the concert-hall tour. (Found via Christine Sun Kim.) The Tumblr appears to be the work of Willem Boning. The above illustration is from the blog entry, and was presumably drawn by its author. (Bonus fun fact: if you pop those line drawings of hall schematics into Google’s image search, you end up with lots of patterns for making clothes.) … I wrote that first section of this notice when I initially came upon the blog, and in the ensuing days there have been a bunch more posts, richly illustrated and observed, including “leather and feather” wall hangings as early acoustic panels, two very different organ scenarios in the Netherlands, and acoustical instruments at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, including a “sound analyzer” from 1880 and a “sound mixer” from 1865.

She Came to the Land of Ice and Snow: At fluid-radio.co.uk, intrepid and prolific artist Kate Carr reports on her field recording expedition in Iceland, complete with photography and audio. In a detailed summary of her journeying and procedures, she admirably de-romanticizes the landscape, and brings some humor to the grey of Ólafsfjörður: “One day after spending about half a day up in the silence near the top of one the nearby mountains recording the sounds of tiny pebbles tumbling from the peak, I began to notice the unmistakable throb of dance music. As I descended further it became a pounding soundtrack, which reverberated across the valley. It was the local aqua aerobics class, which takes place each day near the primary school.”

Startup Sound: There are many fronts in the entrepreneurial war to monetize artificial intelligence at the consumer level. So far as we presume that such intelligence will be recognizable to us, the presumed interface is not physical but aural — well, it’s physical to the extent that the aurality triggers something in our fairly sensitive human ears. Spike Jonze knew this in his fine movie Her, and Apple, Google, and Microsoft, among others, know it in their service-oriented fledgling technologies. For Apple, this intelligence is a humanoid known as Siri. Microsoft’s Cortana has a name that sounds like a font but is borrowed from a fictional artificial intelligence from a video game. (It says something about where we’re at that we must distinguish fictional artificial intelligence from non-fictional artificial intelligence.) Google continues to keep its AI behind a functional wall; it has no anthropomorphism-enticing name, just the willfully bland product appellation Google Now. Among the latest events in this AI war is Apple’s acquisition of a company called VocalIQ. It seems that VocalIQ focuses not on the response system, but the input system. For in AI, listening is just as important as thinking or speaking. Details at independent.co.uk.

Earliest Polyphony: As ever, the further we move forward in time, the more our technology advances, and thus the further back we can reach in time. This time it’s to what the Cambridge University describes as the “earliest known piece of polyphonic music” (see above). It dates back to the 10th century: “It is the earliest practical example of a piece of polyphonic music – the term given to music that combines more than one independent melody – ever discovered.” Now we can just hope for a Janet Cardiff installation to make it real for us. (Found via Jeff Kolar.)

This first appeared in the October 6, 2015, edition of the free Disquiet “This Week in Sound” email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.

October 7, 2015

Everything Passes with Ease

Matthew Barlow’s “Sound Meditation 3” is eight minutes of gently pulsing tones. They layer and they ripple. The ripples spread out as new tones emerge. Somehow the fragility is retained, despite the sequential activity, despite the accumulation of tones, the eternal reemergence of tones. The piece never comes close to suggesting, let alone reaching, anything like a critical mass. Everything passes with ease. Balancing the elegance is an underlying plasticity to the tones. It is light music made from vaguely unnatural sounds, a synthesizer’s vision of cloud formations, a silicon chip’s sense of water drops.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/matthewbarlow. More from Barlow, who is based in Asheville, North Carolina, at matthewbarlow.bandcamp.com.

October 6, 2015

The Ghost in the Cloud

There is a subset of SoundCloud accounts that either through anxiety, or cluelessness, or an extremely refined and considered sense of how social media functions, opt to share very little besides the music itself. Sometimes even the account names themselves are purely generic, many following in the semi-anonymous footsteps of Aphex Twin’s user18081971 (that particular number, by the way, isn’t as anonymous as it looks — it’s his birthday: August 18, 1971). Other such mysterious accounts have a handle, even an avatar, maybe an evident design sensibility, but little if anything else. If the media is loud, quiet gets attention. If your music is in any way ambient, then quiet comes naturally. All, for example, that the account of blu3b0x says of the musician(s) behind it is a claim of allegiance to a group that takes its name from a hallowed cyberpunk anime: “Gh05T_1N_TH3_5H3ll_Kr3W” reads the only text in the account’s biography field. The tracks so far — there appear to have only been six in the past two years, all but one of them in the past four months — are largely elegant, glitch-ish beats, like “Backtrack5,” which pumps a pneumatic pulse that sounds like a cybernetic dog panting for more data:

In contrast, “HAARP” is more background than backbeat, some drum pads ushering in soft tones that borrow from the more sci-fi-esque elements of the Selected Ambient Works Volume II playbook:

Each blu3b0x track comes with a black and white icon, a photo that in some way or other touches on technologically mediated communication. For blu3b0x, SoundCloud is the medium, and the communication is limited to the essentials.

Tracks originally posted at soundcloud.com/blu3b0x.