Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 358

November 14, 2015

The Quantified Shelf

OJ: Original Jedi

1: Fun!

2: Van Dyke Parks. D? P? Is that a last name?

3: This Dillinja/Lemon D split single is gonna kill me.

3b: “Dad, I need an ‘N’ record.”

4: Is there an app for this?

5: I could put a piano in there.

6: Sell it all.

7: Dump it all.

8: Oh, then I’d have to sort the sheet music.

9: No, this is fun.

10: Take break to tweet a lot.

11: Yeah, I need this LP of John Cheever reading The Swimmer.

12: First sighted accidental second copy: Ray Davies’ Return to Waterloo.

13: I worked for Tower Records for 7 years full time. It’s probably best I never actually worked in a Tower store.

14: I own a heap of hip-hop 12″s but playing them interrupts this activity even more than tweeting does.

15: Whatever happened to [____]. Do not hit search. Do not hit search. Do not hit search.

16: Whew, hit a stack of Ns. Was worried the movers lost a crate (back in 2003 when I moved back to San Francisco).

17: I don’t think Randy Weston owns this many Randy Weston albums.

18: There were 4 people in Destiny’s Child at some point?

19: Note on Billy Childish LP says art’s inside it. Assigned him a drawing. We ended up not being able to print it.

20: Why’s this Ornette Coleman sleeve empty? (Whew, found it.) (And why’s “Ornette” not in my laptop’s dictionary?)

21: 5-year-old is making a temporary post-it sign. Says: “Dad, are there any silent letters in ‘various’?”

22: 5-year-old plays electric piano along to Nav Katze remix album, turns it into a Herbie Hancock album.

23: Done. (For now.) I still need to sort through this huge stack of WTF.

24: And then I’ll need to, you know, sort within each letter/category.

25: And, er, then on to the 7″s, 10″s and, er, CDs …

26: Then get ’em into a spreadsheet.

27: And then back to MP3/FLAC/etc., which is mostly what this was an exercise to avoid.

November 13, 2015

Slurred and Unscrewed: Aphex Twin Reworks Himself

The “spotlight” feature on SoundCloud is how a given individual account can highlight tracks, raising up to five of them to the top of the account page. The spotlight feature can also hide new tracks in plain sight. If you pay attention regularly to a given account, you’ll often peek below the spotlight to see what is new. However, new tracks don’t appear at the top of the regular feed if they’re — well — already spotlighted.

All of which is a roundabout way of saying several new Aphex Twin tracks popped up recently on his soundcloud.com/user18081971 account, in addition to the revised “Avril 14th” I mentioned earlier this month. In fact, perhaps my single favorite post-seclusion track is among the recent uploads. The track was part of the original Aphex Twin SoundCloud mother(up)load, back when he was disguised as user48736353001, before becoming user18081971. And then for awhile it disappeared, as his tracks are wont to do. Here it is:

What it is is Richard D. James playing his much loved, oft-sampled, movie-accompanying “Avril 14th” — originally on his 2001 album Drukqs — backwards. Now, there are backwards versions of many of James’ tracks, including all of Selected Ambient Works Volume II, floating around, especially on YouTube. Backward listening provides lots of insight, and not all of it Satanic. It gives the listener a sense of structure and tonality apart from the original. But this version isn’t simply “Avril 14th” reversed by a fan in Audacity. What it is is all the notes of “Avril 14th” played backwards in sequence, by Aphex Twin himself. The brief accompanying track note states:

[[tapedel] played & programmed customised Yamaha Disklavier Pro, Recorded To Nagra IVS 5″]

What’s funny about this distinction is that he goes so far as to make that the title of the track: “avril 14th, notes played backwards, not the audio.” And what results is unmistakably reminiscent of the original, but as if played with gloves on, the melody half-remembered. And it is absolutely beautiful. Music can be over-heard all too easily, and it’s remarkable how simply hearing the notes in reverse order provides comfortable proximity and yet the freshness of something somehow new.

Another recent Aphex/user18081971 highlight is “Th1 [evnslower].” It is just that, the track “Th1 [slo],” which appeared about nine months ago on the account, slurred and unscrewed: the original 6.5-minute drone stretched to nearly twice its length:

The original “Th1 [slo]” was part of the Selected Ambient Works Volume 3 beta playlist’s starter set that I first put together, and the “[evnslower]” edit has, of course, been added to the playlist, bringing the set to 14 tracks total:

November 12, 2015

Disquiet Junto Project 0202: Text-to-Speech-to-Free

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group on SoundCloud.com and at disquiet.com/junto, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate.

Tracks will be added to this playlist for the duration of the project:

This assignment was made in the evening, California time, on Thursday, November 12, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, November 16, 2015.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0202: Text-to-Speech-to-Free

Create an audiobook chapter from the new essay collection The Cost of Freedom.

Earlier this week the book The Cost of Freedom, with an essay by Lawrence Lessig, among others, was published into the public domain. Its goal is to raise awareness about the ongoing detainment of Creative Commons coder/artist Bassel Khartabil Sadafi. I have an essay in the book, as does Jon Phillips, who encouraged that China-gallery project we did a few weeks ago (project 0195).

We’re going to help spread the book by creating audiobook entries of some of its chapters. This is the third Junto project related to Bassel. On March 12, 2015, the third anniversary of his seizure, we did Disquiet Junto Project 0167: Placid Cell. And earlier still, on January 23, 2014, we did Disquiet Junto Project 0108: Free Bassel.

These are the steps:

Step 1: Obtain a copy of the free book The Cost of Freedom: A Collective Inquiry at:

Step 2: You will be turning one of these chapters into a spoken-word recording. You’re encouraged to use text-to-speech, but you also can read it aloud. Select a chapter — perhaps out of a specific interest, or perhaps by chance operation. When doing so, please, if you have a moment, please register which chapter you’re doing on the Disquiet discussion forum, so we’re less likely to have repeated chapters:

http://disquiet.com/forums/discussion/18/junto-0202-bassel-chapters

Step 3: Create a track with the spoken text of the chapter and additional background music. You can use your own original music, or source audio from previous Bassel-related projects. The text should remain intelligible. Do confirm the license on music from these two projects before employing:

http://disquiet.com/2015/03/12/disquiet0167-freebassel/

http://disquiet.com/2014/01/23/disquiet0108-freebassel/

Step 4: Upload your completed track to the Disquiet Junto group on SoundCloud. In the title to your track include the term “disquiet0202-costoffreedom” and the title of the chapter you used.

Step 5: When sharing the music, please consider employing these two tags: #freebassel and #newpalmyra. The first is an ongoing tag raising awareness of Bassel’s situation. The second, related to Junto project 0167, involves collective effort to continue one of Bassel’s art projects: a three-dimension CGI rendering of the ancient city of Palmyra.

Step 6: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

Deadline: This assignment was made in the evening, California time, on Thursday, November 12, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, November 16, 2015.

Length: The length of your finished work will be determined by the length of your selected chapter.

Upload: Please when posting your track on SoundCloud, only upload one track for this assignment, and be sure to include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Title/Tag: When adding your track to the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com, please in the title to your track include the term “disquiet0202-costoffreedom” and the title of the chapter you used. Also use “disquiet0202-costoffreedom” as a tag for your track.

Download: It is preferable that your track is set as downloadable, and that it allows for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

Linking: When posting the track, please be sure to include this information:

More on this 202nd weekly Disquiet Junto project (“Create an audiobook chapter from the new essay collection The Cost of Freedom) at:

http://disquiet.com/2015/11/12/disquiet0202-costoffreedom/

The source of the text in this project is from the book The Cost of Freedom, which raises awareness about the ongoing detainment of Creative Commons coder/artist Bassel Khartabil Sadafi. More on it here:

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

Join the Disquiet Junto at:

http://soundcloud.com/groups/disquiet-junto/

Subscribe to project announcements here:

http://tinyletter.com/disquiet

Disquiet Junto general discussion takes place at:

#freebassel

#newpalmyra

November 11, 2015

Waveform as Spoiler

When, a few seconds in, the click clack chitter chatter of Louise Rossiter’s elegant “Rift” gives way to a break-beat sliver of silence, you know something’s coming. For one thing, the track certainly isn’t merely two seconds in length. For another, it’s called “Rift,” not “Cliff,” so there must be something on the other side of this gap. But also, there’s the SoundCloud waveform, and the waveform of “Rift” shows plenty of sound, and plenty of rifts, ahead.

What follows is variety of play on that beat, and the rift. A few other sounds mingle: something like a whip spun overhead, something like a top spinning on metal (headphones are a must), something like the sizzle of a match, something like an empty glass bottle bouncing on a hard surface but failing to break. The SoundCloud waveform may spoil the silences and the peaks, but it doesn’t begin to hint at the sounds.

She writes, in a brief accompanying note:

There are a number of different meanings of Rift permeating this work. The deliberate destruction of source materials allow for the creation of gestures that permit the fracturing and breaking of the sonic space. One of the pieces principle functions is an exploration of relationships between sound and silence. The silences that punctuate the sonic canvas throughout Rift are intended to allow the listener to reflect on events in the work, and anticipate what might follow.

Rossiter has her way with the battery of noises she has compiled. “Rift” is prickly and fiery and convinces your ears to pay close attention.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/mad_lou. More from Louise Rossiter, originally from Scotland and based in Leicester, U.K., at louiserossiter.com and twitter.com/electro_lou.

November 9, 2015

The Bell Jar Filter

Vantzou (standing) in a performance at M-Museum in Belgium with a six-piece cello ensemble

Christina Vantzou makes a dense, rich music that brings old-world classical textures into a contemporary electronic realm — and vice versa. She directs her own videos, drawing not only on the slow-motion aesthetic that guides her music, but also on the training she received as an art student in Baltimore, Maryland. Video is what brought her into music in the first place. She collaborated with, among others, Adam Wiltzie, of Stars of the Lid, and their work together culminated in recordings under the name the Dead Texan.

Having lived in Brussels, Belgium, for over a decade, Vantzou has released a trio of solo albums whose evocative stasis never fully hides the sense of sheer effort that is required for her to consistently achieve this level of concerted, sublime quietude. This interview was timed to coincide with the release of her latest full-length record, Nº3 (Kranky). She agreed to be interviewed, and after some phone calls we did this via email as a back-and-forth. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of that discussion, in which she details her compositional process, describes how she interacts with chamber ensembles by utilizing graphic scores, and reveals that the sound she most wants to achieve may be that of an orchestra performing inside a giant bell jar. Her use of graphic scores and mid-performance flash cards bring to mind the experiments of Frank Zappa and, later, John Zorn. For one track on the new record the “score,” as she describes it, was a prepared recording that musicians listened to on headphones and responded to in real time. We discussed her graphicscores.com website, which she launched to explore common ground between visual artists and musicians, including John Also Bennett, Peter Broderick, and Julia Kent.

Interspersed throughout are photos shared by Vantzou that depict her visual scores and her live interaction with musicians. Also below are two videos from the album, both of which she directed. (And full disclosure: Vantzou contributed a score to a museum installation, “Sonic Frame,” that I developed for the 45th anniversary of the San Jose Museum of Art based on a video by artist Josh Azzarella.)

Vantzou makes music that doesn’t so much blur the lines between what is broadly considered “classical” and “electronic,” as it is that she lets the two conceptions overlap until wonderful moiré patterns result from where they do and don’t inherently align.

Marc Weidenbaum: Just to start with, what brought you to Brussels?

Christina Vantzou: I was passing through. I was on my way to Greece. I’m half Greek, so I would travel to Greece a lot, and I had a plane flight that was rerouted through Brussels. So, I had an unexpected stop in Brussels, and I liked it and decided to stay. Well, I did go to Greece, but I ended up moving to Brussels not long after that. It was all these unexpected circumstances that introduced me to Brussels. I’ve been there since 2004. When I moved to Brussels I spoke the kind of French that you learn when you learn French in American schools, so very little, but I did take French classes in elementary school and high school.

Weidenbaum: That’s around when the Dead Texan work came out.

Vantzou: Yeah, the Dead Texan work started in transition from when I was living in Baltimore. I remember starting there and then continuing in Brussels. I was working on that for a couple years — 2003, 2004 — and then focused on touring with the Dead Texan the next few years.

Weidenbaum: Please say a little about your art-school education.

Vantzou: I went to MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. They had a general fine art degree, which is common now in art schools, but it was not so common at the time. It was the “newest” major in a lot of art schools. You could shift around to different departments. It got made fun of within the school at that time. While now interdisciplinary work is really well accepted, at the time I remember the general fine art department — which was called “GFA” for short — was referred to as “generally fucking around.” [Laughs.] I got into art school after I got a full scholarship based on a very strong ceramics portfolio. [Laughs.] I was doing a lot of ceramics but I thought I would be a painting major. And then after my first foundation year I decided I wanted to do GFA as a major where I ended up doing mostly photography at first, black-and-white and color, and then slowly I started focusing more and more on video. My last two years I took mostly all video and animation courses. I took a sound class and learned Pro Tools, which I still use today. I think on my degree it says “general fine arts major with an emphasis on video.”

Weidenbaum: Were there instructors there who were especially instrumental in honing your sense of what you wanted to do?

Vantzou: Yeah. There were two or three people in particular who were influential in their open-minded approach to being practicing artists in the world. I remember there was one teacher in particular. We spent a lot of the class time just watching music documentaries. We watched the Maysles Brothers’ Gimme Shelter, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Don’t Look Back, about Bob Dylan, and on and on. Anyone could recommend one; we’d watch it. I got really interested in this genre and even thought, as a video artist at the time, that I would work in this field. I was really inspired by cinéma vérité and the artists making these documentaries. That particular class had a number of individuals in it who have become successful visual artists. I think the teacher inspired a lot of us. His name was Jeremy Sigler, and his class was called “Parapainting.” We also had to form bands as part of the class and each band played a show at the end of the semester.

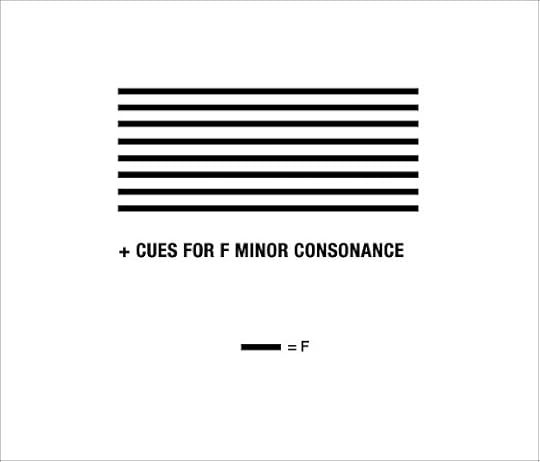

First draft of the score for “Engtanglement” from the album Nº3

Weidenbaum: Your work in video lead to your association with Adam Wiltzie, of Stars of the Lid. The two of you then recorded and performed as the Dead Texan. I have one question about the Dead Texan period of your music, since it’s already pretty well-documented. Wiltzie has been widely quoted as saying that the music made by the Dead Texan took on a name other than Stars of the Lid because the Dead Texan music was “too aggressive” for Stars of the Lid. I’ve often wondered if he really meant it literally, or if he was joking.

Vantzou: [Laughs.] Adam is very clever and he is smart enough to know that these few quotes that you let become part of the original press release — that quote about the music being “too aggressive” was in the press release that went out with the record — are being copy-pasted everywhere, and especially for a record like that, that enters the world through a network that’s relatively small. There’s just a lot of recycling of the wording from those press releases, so that one quote got printed over and over and over. He’s clever and he’s got a sense of humor, and he doesn’t take all of this too seriously, and if anything that quote is an example of that. Does that make sense?

Weidenbaum: Yes, that makes perfect sense. It, I think, confirms something I’ve long thought about.

Vantzou: It’s really funny, I think, that little statement. [Laughs.]

Weidenbaum: It’s funny, also, how much it’s taken at face value, to have factual, direct meaning. I’ve always thought, I dunno, it feels like he was poking at something in a fun way, rather than making a clear distinction between two types of music. In any case, moving on, how did you come to work with graphic scores, in which images serve as visual compositions of non-traditional notation? They are central to your music production. I’ve always admired the work of people like Morton Feldman, and Stephen Vitiello, just to name two people, among many, associated with graphic scores.

Vantzou: In the time that I was working on the first two albums, I had a few opportunities to perform, and each time I would be working with a quartet or a string trio or sometimes a string quintet, or however many string players I could get hold of. There was a very low budget, or no budget, and so I often worked with local musicians. So I’d gather up different ensembles in the different cities I would play, and there was also very short rehearsal time. It’s a lot of work, actually, to work that way, but that was necessary, and along with that necessity it became urgent to figure out a simplified way to work on the music with so many different groups of people. Given all of those restraints, and the fact that I don’t read or write musical notation in the classical sense, I had to come up with another way to communicate the musical structure to musicians. I needed a system where even if we only had time to rehearse some pieces in the set, the other pieces could be played because of their immediacy and simplicity. Rehearsals and concerts were smashed into one day, but I would have plenty of time leading up to concerts to work on these scores. The very first graphic scores I made were all by hand. Sometimes they just looked like MIDI sequences drawn out on paper, and sometimes I incorporated symbols. It was just a simple way of making a very rudimentary translation of the music for the group of musicians and the instruments I would be working with for a particular concert. That’s how I came about working out my own graphic scores. As I was doing that, I realized this was part of a bigger history of graphic. I found myself really interested to discover more about what its history was and who was involved and how it’s played out over time.

Sol LeWitt–inspired F drone score, which was first performed at M – Museum inside a Sol LeWitt exhibition

Weidenbaum: When you produced the website graphicscores.com, how far along was that into your explorations into graphic scores?

Vantzou: That was pretty far in. I organized that after Nº2. I wrote friends, different musicians I’d played with, different people I’ve collaborated with, and artists and musicians that I thought would be interested in the project. I made a private call to friends to see who wanted to submit and the pieces that are on the website are the ones that were turned in. I’ve been meaning to do a second call. I plan to do that one day, but I haven’t found the time.

Weidenbaum: The URL is a pretty great one. Was it readily available, or did it take effort to get it?

Vantzou: The URL graphicscores.com was readily available. That’s kinda why I wanted to post them on a website, because as I was looking more into graphic scores, I was surprised by the lack of books that are floating around. There are two really beautiful ones that I know of. I don’t own them but I’ve looked at them. There are many people making graphic scores out there and you can find them here and there, some are very beautiful, but as far as I could tell a contemporary collection of graphic scores was nowhere to be found.

Weidenbaum: The only collection I have is Notations 21 by Theresa Sauer.

Vantzou: And it’s a fat one, right, a hardback?

Weidenbaum: Yeah.

Vantzou: That’s one of the ones I’ve seen. That’s really beautiful.

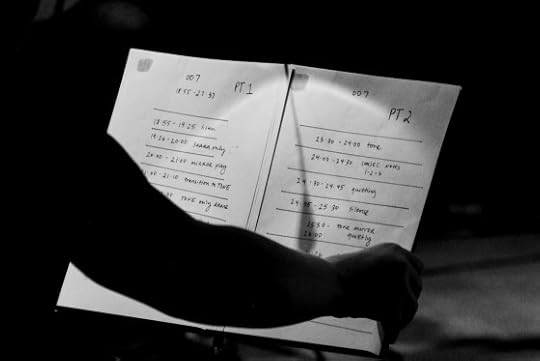

Weidenbaum: You yourself employ at least three different ways of scoring with graphic notation. You make notes for yourself as a composer when creating music. You make static graphics that musicians then interpret. And you also use a flash-card system in which you conduct musicians by showing them images as they perform. Are these all interrelated, all part of the same graphic language, or do they form distinct categories?

Vantzou: They’re all different. I used homemade flashcards a lot for Nº1 and Nº2. A big favorite was a whale drawn with a blue marker. The cards were helpful in that they provided some spontaneity. I was reading the Frank Zappa autobiography at the time, The Real Frank Zappa Book, and you really get a sense of him as a composer. I was inspired by how he worked with different classical groups and orchestras over the years. Apparently, when he auditioned musicians, he would introduce the idea of “cues” to them, to see if they could spontaneously change the flavor of their playing. Each cue involved a pop-culture reference. He’d say “Mister Rogers” and see if the musician could play with a Mister Rogers flair. He found that certain very skilled musicians couldn’t do that, so he used this as a filter and only brought in musicians who could add in the spontaneous flair. Reading that, I took from this the idea that you could play with spontaneity in a concert setting. Not improvisation, because there are clear parameters, but unrehearsed: Spontaneous. With classical instruments that’s very much against the rules. [Laughs.] It’s precisely the opposite of what you’re always told. It was educational for me, to see the musicians that I would work with get really excited about those kinds of things, because it felt pretty rebellious, I suppose, kind of a radical thing to do, counter to the sort of things that conservatories drill in.

Six-pice cello ensemble at M-Museum, Belgium

Notation in time: a score made for performing Nº1

Weidenbaum: Were musicians generally responsive to the flash cards and graphic scores?

Vantzou: Sure. At first I was intimated to introduce these ideas. I was nervous that the cards wouldn’t be well received. But looking back I can see that the music always attracted musicians who were open to these ideas. It’s clear from the music that there’s some experimentation involved. I’ve been fortunate that each time I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with musicians on concerts or recordings, everyone’s been pretty open. Depending on the group, some warm up to certain ideas differently or more slowly than others, but everyone seems to come around.

A graphic score made by Vantzou for “Kol Nidre”

Whale card: used to perform “And Instantly Take Effect” from Nº1

Weidenbaum: You started off doing art in the non-musical sense. And you did videos for other people’s music before you made videos for your own music. Now you create your own videos for all of your own music. Do you feel your own music is done when the music’s done, or do you feel like your musical work is not done until the video is completed?

Vantzou: That’s a good question. I’ve been figuring out that the music is not done until the video is complete. I feel like, because of production timelines — both video and sound production taking years in some cases — it’s been challenging to sync up these production cycles — and so the tendency is that the music is completed first. Album Nº1 clued me in, Nº2 made this more clear, and now with Nº3 I’ve got it. For Nº4 I’d like to make sure videos are complete before sound is mastered. What I find is that the video really informs the music in a way that isn’t possible until the two are together. For Nº3 I managed to do half and half. I did some early edits to the video so that I could — no, that’s not true. Actually, what I did, which is really what you’re not supposed to do, is this: so, there’s a track called “The Future” on Nº3, and there’s also a video out there called “The Future.” I don’t think it’s very noticeable, but the mix on the video is different than the mix on the record. By the time I put the sound and video together I realized that the sound needed some work so I decided to go ahead and do that work and released the video with this slightly different mix. I guess in a perfect world I would have done that before mastering so both versions are identical, but anyways, that’s how it went.

Video Interlude

These are two videos from Christina Vantzou’s album Nº3. Both were directed by Vantzou, and both are accompanied by this note: “for best viewing watch in the dark at night.”

“The Future” (vimeo.com) was directed and shot by Vantzou, with performance and choreography by Siet Rae:

“Shadow Sun” (brainwashed.com.

“Bassel K”

“Bassel K” is a short essay I wrote for the book The Cost of Freedom: A Collective Inquiry, which was published today, November 9, 2015, to draw attention to the continued detainment in Syria of Bassel Khartabil Sadafi. The publication came together as part of a “book sprint” held in Pourrières, France, from the 2nd to the 6th of November. (I wasn’t in France. I was home, typing in San Francisco.) Contributors include Lawrence Lessig, Lucas Gonze, Barry Threw, Niki Korth, and Jon Phillips, among many others. Bassel has been held since March 15, 2012.

We’ve done two Disquiet Junto projects related to Bassel’s detainment. On the third anniversary of his seizure, March 12, 2015, we focused our imaginations on the silence of a closed room: “Disquiet Junto Project 0167: Placid Cell.” Previous to that, back on January 23, 2015, as described in the essay below, we expanded on one of his works-in-progress, creating an imaginary soundscape to the ancient city of Palmyra: “Disquiet Junto Project 0108: Free Bassel.”

And here is the essay:

“Bassel K”

I read The Trial at too young an age. It instilled in me many things, some of them even positive, such as an affection for Franz Kafka, an aspiration to taut structure, and a desire to tell stories. It also haunted me, and it does to this day. It imprinted on me an intense fear of undeserved imprisonment.

I was introduced to the imprisonment of Bassel Khartabil by three remarkable people: Niki Korth, Jon Phillips, and Barry Threw. They are in many admirable ways as free as Bassel is not. Each of the trio is dedicated to their own individual and collective artistic pursuits to explore the deep potential where technology and culture meet. They make and celebrate the things that make today a special time.

And they know full well that all is not right in our time. They expend significant energy in building awareness of the ongoing fact of Bassel’s murky, tragic legal status. At their suggestion, back in January 2014, I gathered musicians to highlight Bassel’s plight. These musicians participate collectively in something called the Disquiet Junto. It’s a freeform group I moderate that each Thursday responds to music-composition prompts. The idea behind all the prompts is that creative constraints, such as those employed in Oulipo and Fluxus, are a useful springboard for creativity and productivity.

The Junto’s fondness for such “constraints” met a fierce complement when we tackled Bassel’s situation, which is that of a most uncreative form of constraint. There were many ways we could have paid tribute to Bassel. What we elected to do in the Junto was to keep one of his projects going: He may be in jail, but his art could continue to develop. Prior to Bassel’s arrest on March 15, 2012, in Damascus, he was working on several projects. Among them was a three-dimension computer rendering of the ancient city of Palmyra. What we in the Junto did was make “fake field recordings”: audio of what the halls of Palmyra’s structures might have sounded like millennia ago. Much as Bassel was trying to revive an ancient world, the Junto participants were, in essence, keeping one of his projects alive while he is incapable of doing so. And, of course, building upon his artistic efforts was true to the ethos of the Creative Commons, in which Bassel has been profoundly engaged.

We had no idea, of course, back in early 2014 that Palymra would itself receive worldwide attention when ISIS, the extremist movement, would in 2015 move to destroy much of the ancient city’s remaining architectural history — or that, later still, Russian warplanes would further damage the site. This is one of Kafka’s lasting legacies: just when things seem horrible, they can and do get worse.

Palmyra has fallen. Bassel remains in jail. The challenge to rectify his situation has long since surpassed the overly employed term “Kafkaesque.” Someone must have been telling lies about Bassel K, because he is still kept from his freedom. But as long as he is in prison, there are plenty of people telling his story, and keeping his work alive.

Below is a shot of Bassel in happier times, and an image from his “3D Palmyra” work mentioned in my essay:

More on the book The Cost of Freedom: A Collective Inquiry, which is in the public domain and is available as an ePub and PDF, at costoffreedom.cc.

November 8, 2015

Nicklas Lundberg’s Aleatoric Voicings

Nicklas Lundberg of Sweden uploads audio to SoundCloud under the various names, including Back Porch and Entryway. These appear not to be names, however, so much as points of orientation. Lundberg lists “Entryway” as his “main account,” which makes “Back Porch,” in contrast, a place where he presumably tends to his less common creative practices. One hopes that the practices that inform the dramatically titled “Greater Duophonic Mass Part 02 – (parallel modes and aleatoristic melodies for long digital notes)” become more common for Lundberg, because the results are beautiful — harrowing at times, yes; emotionally draining even, yes. But, beautiful nonetheless, like the Roches covering Arvo Pärt around a camp fire. It’s a nearly 20-minute piece of layered singing, the parts passing with the chance criss-crossing hinted at in the title (the “aleatoric” part). At times a voice comes to the fore, a deep groan or a high, piercing screech, but it all, in the end, is subsumed into the mass. That’s “mass” in both the density and liturgical sense of the word.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/nlundberg2. More from Lundberg at soundcloud.com/nlundberg.

Report from the (Real) Future (Fair)

As you can perhaps deduce from the unused drink tickets that remain attached to these two wristbands, I had a pretty debilitating head cold during the Real Future Fair in San Francisco on November 6 and 7. I did, though, have the great opportunity to share the fruits and nearly four-year history of the Disquiet Junto in a short presentation during the Fair’s closing night “Future of Sound” event.

This appearance meant, among other things, sharing a bill with soul-pop figure Kelela, Hrishikesh Hirway of the Song Exploder podcast, San Francisco electronic musician Pamela Z, and performance artist Dia Dear, as well as a bunch of journalists from Real Future and its parent media organization, fusion.net. Head cold or not, that was pretty grand.

Finally made it the @TheRealFuture Fair. pic.twitter.com/sjYZu3cyNa

— Marc Weidenbaum (@disquiet) November 6, 2015

Some quick highlights of the Fair:

— Alexis Madrigal, editor-in-chief of fusion.net, did me the favor of interviewing me for the Junto presentation. I like talking in front of crowds, and I like a public discussion all the more. Madrigal did a great job of summing up what the Junto is, and if I get my hands on the audio I’m going to transcribe it for future (not just Real Future) use.

— Madrigal has a particular sense of how the sounds emitted from Junto projects are interestingly apart from what is generally considered music. This perspective is something that I can, frankly, lose track of since I spend much of my listening time inside the drone bubble. (I did take the opportunity to mention that one of my favorite Junto projects played with the idea of a song, using the room tone of three different places to flesh out the verse, chorus, and bridge of a “song.”)

— My favorite moment of the live Junto event was when Madrigal had the entire audience close their eyes for 30 seconds and just listen to the final of the Junto tracks we prepared. Me? I kept my eyes open to take it in.

— The Junto project we shared with the Real Future audience is the current one, number 201, in which we: “Encapsulate an album for efficient yet meaningful consumption.” The idea is that in the future, among the many problems of overpopulation and the resulting leisure time provided by the robotization of work is that way more art is being produced. So, how do we, as humans, consume it — not to mention the vast back catalog of novels, music, video games, etc.? In addition to some very interesting sonic processing, this Junto project has led to some fun short-form science fiction in the liner notes to the various tracks. We’ve compressed two different albums in the course of the project, self-titled records by the French group Salmo and the New Zealand duo Montano. For the Real Future event I played a few tracks off the Montano album for context, and then three of the Junto reworkings: from Australia-based Tuonela, Tokyo-based Hiroyuki Kuromiya, and, closer to home, Erik Kuehnl of Berkeley.

— In addition to the folks I mentioned up top, there was some interesting live journalism. Kashmir Hill talked about the “real world mute button” being developed at Doppler Labs. Hill also did a great job the day prior moderating a panel about the future of surveillance.

— Kevin Roose gave a funny talk on vocaloids, in particular Hatsune Miku (who made a guest appearance in the Red Bull Music Academy comic on synthesizer legend Tomita that I edited, with Hideki Egami, last year).

— There was a short video from Daniela Hernandez on LRAD sound weapons.

— Kristen V. Brown reported on an outlier in the field of performance-venue acoustics.

— And there was a report on sonic healing that balanced skepticism with inquiry, but I didn’t catch the name of the reporter.

— One great thing that the Real Future producers did was hire Marc Kate to “live score” the event. Of course, he didn’t live score my session, since I was providing the music, but in all the reports he, in real time, summoned up audio to augment the narrative.

— The headliner of the show was Kelela, who is very much of the soul-pop realm in whose context the idea of much Junto work being “musical” to a general audience can be a complicated sell. I didn’t stay for her performance (#headcold) but I greatly enjoyed the interview that Hrishikesh Hirway of the Song Exploder podcast did with her at the start of the evening, talking about the recording of one of her songs. She discussed various aspects of her process, including working with producers, reworking provided instrumental tracks, singing first in vocalese before filling in the vowels and consonants and spaces with actual words. (I also missed Pamela Z.) One great thing about Hirway’s Song Exploder is how the musicians among its listenership are being encouraged, if not outright trained, to speak analytically about how they do what they do. Historically, this has not been a strongpoint of pop-music journalism, excepting technology/instrument-specific reporting in magazines like Guitar Player.

More details on the event: realfuturefair.com. Major thanks to Alexis Madrigal and Cara Rose DeFabio. Check out the website at

fusion.net, and definitely subscribe to Madrigal’s Real Future newsletter at

tinyletter.com/realfuture.

Immediacy + Accessibility = Joy

Finger Painting: A hand interacts with the innovative Borderlands Granular iPad app

One of the great resources for mobile music — from iPad apps to small new gadgets — is the website palmsounds.net. For almost a decade, Ashley Elsdon has tracked, and participated in, the development of mobile audio, from full-blown digital workstations to casual entertainment, what here on Disquiet.com is often referred to as “audio-games.”

Elsdon graciously submitted to an interview, which we did over a few weeks as a collaborative Google Drive document. The discussion ranges from the early sonic hacking of the now ancient PalmPilot to the museum-approved devices from Teenage Engineering. In between we touch on old-school manufacturers such as Korg and Roland adapting their hardware for use as software, Elsdon’s own efforts to use mobile tech to aid those with learning disabilities, as well as his and my mutual disappointment that — so far, at least — mobile music has not yet become a general-public form of entertainment, even as it has become a massive force in professional and home-based music production.

Marc Weidenbaum: I want to start with the name of your site, palmsounds.net. The word “palm” is in it because it started in relation to the making of music on the Palm Pilot, right — what later became “Palm OS”?

Ashley Elsdon: You’re right there. It did start as a result of making music on Palm OS devices. This came about because I started using a Palm III a long time ago, mostly for getting myself organised. But as I started to get used to the device I realised just how much these little computers could do and what a vast community there was for them (which is sadly all but gone). Eventually I stumbled into looking into the musical capabilities of the Palm OS. Back in the late 1990s it was, to say the least, minimal, but it was there. A site called “minimusic.com” had started developing some notation and sequencing apps for the Palm OS (although back then we didn’t call them apps) and I started playing with these. But even then this was quite a while before Palm Sounds started. As Palm OS evolved, a new app arrived called Bhajis Loops, which was, and in fact still is, one of the best mobile music making apps ever, in my opinion. I spent a lot of time with that app.

Memento Mori: The Palm III , introduced in 1998

It wasn’t long after that I started to write Palm Sounds. I was experimenting with blogging about a bunch of different subjects, and making music on mobile devices was the one that really stuck for me. I was actually quite surprised that people were interested in such a niche subject. But they were, and people started to contact me about mobile music, and things have just continued from there. The rest is history as they say.

Substance Over Stylus: Screen interfaces for the Palm software Bhaji Loops, the work of Olivier Gillet, later of Mutable Instruments

Weidenbaum: What year was that around? Could you provide a general timeline for major milestones for the site’s development?

Elsdon: Hmm, actually, that’s quite difficult. The site started off in 2006, but as for milestones I can’t remember much I’m afraid.

Weidenbaum: I feel like the word “palm” right now works as a good synonym for “mobile,” because we have some distance from Palm OS’s onetime ubiquity. Was there a time when you considered changing the name?

Elsdon: In fact I did, and a lot of people talked to me about changing the name. Some people were quite vocal as well. In the end I decided against it as I just didn’t think it was worth it. Palm Sounds grew out of the Palm OS and the musical apps that were around back then. However, it did occur to me that Palm was also a good way to describe handheld music making, so I stuck with it, and in hindsight I’m glad that I did. So much of mobile music has become about iOS that it’s sort of become the only thing that people talk about and I’ve always wanted Palm Sounds to be about more than just one operating system, or one technology. So I think that Palm Sounds is still a good name and is more about mobile music in its most general sense, rather than just iOS.

Weidenbaum: Do you make music?

Elsdon: Oh yes, I’ve been making electronic music since I was 10 or 11 years old. I started out with what you’d now refer to a circuit bent toys, but at the time it was just breaking up toys and making them do things they were never supposed to do in the first place. I quite enjoyed doing that, but back then electronic toys that made noises were expensive and not available in charity shops like today, so it wasn’t a cheap hobby. So from there I went to small devices like Casio’s VL-1. I had two of those. Back then they were about the cheapest synthesizer you could get your hands on, and even then they were about £100 each. But with a 100-note sequencer and a little synth on board it was a nice device.

Cheap Beaps: The Casio VL-1, manufactured from 1979 to 1981

Over time I amassed a range of synths, but they were never too useful for doing anything mobile. And then mobile started to happen. With Palm at first, as I said before, but also with Windows Mobile too, which had some really exciting possibilities in the late ’90s with apps like Griff, which had a complete plugin architecture on a mobile device, something that’s only just happening with iOS.

So, I make a lot of music with mobile devices. Mainly iOS, but also I still do some stuff with Palm and Windows Mobile, too. I like using hardware, too. I love my OP-1 from Teenage Engineering and their PO series too. There’s some quite interesting stuff going on with hardware at the moment.

Teen Dreams: The OP-1, introduced in 2011 and now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, design-wise a feature-packed homage to the Casio era

But I also like desktop music software. I’m fond of Ableton, Reaktor, and Kontakt. One area I’ve avoided is the modular world, at least in terms of stuff like Eurorack. I’m not sure it’s for me, although I do see the attraction.

Anyway, you can find my music, sounds, field recordings, etc. at: soundcloud.com/palmsounds.

Weidenbaum: Part of what interested me recently in speaking with you was a post you wrote about the modular synthesizer “So, Modular Is Huge Right Now, but Is It Right for Mobile Music?”, and its growing popularity. You talked about how “modular” does and doesn’t correlate with your sense of mobile music, of “palm music.” You noted two characteristics that you consider — if I can paraphrase — essential to mobile apps. They are “immediacy” and “accessibility.” And you went on to describe what you mean by those two ideas. I’ll quote them here:

Immediacy — The app is obvious, you can see how to use it and understand it. You’re able to get up and running really quickly.

Accessibility — And I’m not just talking about accessibility from a disability perspective. I’m talking about music software that’s easy to get to and once you’re there it’s easy to make use of.

Were these two concepts clear to you from the start of Palm Sounds, or did they come to mind as time passed?

Elsdon: That’s a good question — and this article of mine might be of interest too: “Modal Pro, a First Look and Some Other Thoughts on Modular Synth Apps”. No they weren’t clear from the start, rather they’ve evolved over a number of years, but as they have evolved they’ve become much more prominent in how I think not only of mobile music but also about music technology in general. This is in no small part because of the work I’ve been doing with Heart n Soul and specifically in the SoundLab project (makeyoursoundlab.org). On the one hand, immediacy is about being able to create music straight away without a steep learning curve, as is often present with desktop software, and also about an interface design that draws you into the act of creating music without dictating a specific workflow. This is a very difficult balance to strike but one that I believe is necessary to engage new users and especially those with little or no musical experience. Accessibility is inextricably intertwined with this. Often I’ve found that traditional musical interfaces are immensely off-putting to users with no experience. However, a more novel or less intimidating interface can result in users finding the sudden and unexpected joy of making their own music.

It boils down to this for me:

Immediacy + accessibility = joy

It’s simple, but not easy to achieve. When you see it in operation it is very obvious.

Audio Access: The web homepage of SoundLab, where Elsdon is a producer and project advisor

Weidenbaum: I followed mobile music from pretty early on, and I think I was, myself, very mistaken in my assumptions about where it would lead. I was fascinated with what I began to refer to as “audio-games,” things like Brian Eno and Peter Chilvers’s Bloom, and a wide variety of browser-based entertainments. It was very late in the game that I realized it was largely going to be the province of musicians, casual and professional, and everywhere in between, using new tools — such as the Caustic, Borderlands Granular, and Samplr, just to name a few — and of course virtual versions of old tools. When mobile music first started happening, I thought it would all be about a new line of general-public interest in interactive sound. Does my early misconception make sense to you, and did you foresee how and where mobile music was headed?

Elsdon: I, like you, had hoped for something that would expand the role of musical creativity into a wider audience. I think that some of the early experiments that emerged in the first days of iOS (before it was called iOS) showed so much promise and some were very well received. Start ups like RJDJ did amazing work in gestural and reactive music, but sadly failed to catch mass-market appeal. Even so, there is still a relatively small community working in this field and beginning, once again, to get some attention.

I was at an event at Abbey Road Studios early this year which focused on the world of generative and reactive music, and whilst a lot of the people there are still pushing forward with ideas and concepts in this area there are new entrants trying out ideas that might bridge the gap in popular culture. I am, as ever, hopeful.

However, mobile music itself hasn’t gone in quite the direction I would have liked. In many ways mobile has followed a path that largely replicates the desktop world, albeit at a much reduced price tag. That in itself is an improvement in terms of accessibility in its widest sense, so that has to be a good thing.

However, as the hardware improves and the OS develops I think that we’ll only see mobile become more and more desktop-esque. On the one hand I believe that cross-platform and inter-device working has got to be a good thing. Some of that I already happening now, but what isn’t happening, at least in a mainstream way, is mobile devices making real use of the actual capabilities of the device in terms of gestural interfaces and how the device can react to its own environment and sensor data. This is my most recent piece: “Are There Too Many Synths?”

Weidenbaum: I’m a huge admirer of RJDJ, and I’ve pleased that over the years Robert M. Thomas, who was Chief Creative Officer at Reality Jockey, has participated in the Disquiet Junto projects and other music scenarios I’ve helped make happen. I still have RJDJ on my iPod Touch. Your critique of the desktop-like nature of mobile music doesn’t seem to deter the energy you put into the site. I trust you haven’t ever given serious thought to stopping the site, right?

Elsdon: Well, I did stop for a while. But I came back, and I’m glad that I did. Keeping up to date takes more and more effort as time goes on, but I’ve no intention of quitting. I still think that the mobile world has a lot to offer and that there are people expanding possibilities to engage new users. Propellerheads Figure is a great example of this. They’re doing excellent work. It’s apps and interfaces like Figure that keep me interested in mobile and what is possible with mobile devices. So I’ll keep at it.

Go, Figure: The app Figure from Propellerheads, makers of the desktop software Reason

I’d like to see more people involved in mobile music realise that there’s more available to them than just iOS. There’s a whole range of interesting portable hardware arriving, like the Teenage Engineering PO series. It’s this kind of thing that keeps my interest in the mobile world, and I hope it’ll keep going for a long time to come.

Weidenbaum: As someone who is at best semi-informed on such topics, and who looks to you in particular, along with Peter Kirn and others, for technological guidance, it seems like Audiobus was something of a game changer for iOS. Everyone talks about “ecosystem,” but where people says “ecosystem” I usually just see “shopping mall.” Audiobus, however, made connecting iOS apps possible in a way, if I’m not mistaken, that didn’t exist previously. I guess this leads to two questions. The first is: What’s your estimation of the role of Audiobus? The second is: What are the strengths of other non-iOS mobile operating systems, primarily Android. I want to get on to Teenage Engineering, but let’s stick to software for a little while longer.

Elsdon: Well the short answer is yes. Audiobus was a game changer for iOS-based mobile music. It made possible what was already possible on the desktop but that Apple had restricted by their sandbox approach to iOS apps. It brought a whole new dimension to iOS mobile music making — but, let’s be clear, one that had been closed off by Apple. That’s not to say that Apple haven’t been vocal in their support for iOS music making. They have. To a great degree in fact. If you look back at the history of iOS you’ll find a range of innovations that Apple have brought to mobile, not least of which was Core MIDI.

But back to the first question, Audiobus have played a much wider and a more central role than just producing the Audiobus app. They’ve successfully created a developer community behind the app. That in itself is an achievement. But they’ve also become a valuable focus for the community as well.

That’s not to say that they’ve had an easy ride. I don’t think for a minute that they have. Apple’s own inter-app audio standard could have caused them significant issues but didn’t. Time will tell how they react to the introduction of audio units in iOS9. But Audiobus is a strong team and seem to have a clear vision of where they want to go next. So I think they’ll remain a key player in the iOS music world for some time to come.

Only Connect: An example of how the Audiobus app allows for routing sound between apps

On the second point, this is quite difficult actually. You mention Android, which is the most obvious operating system to compare against iOS but by no means the only one. So I’ll run through a few to give a wider perspective.

About Android:

It’s only fair to say that at one point Android had the potential to be a real contender against iOS for mobile music. Sadly, at least from my perspective, this hasn’t come to pass. That’s not to say that there aren’t some really good mobile music apps for Android. There are. However, there aren’t the numbers for critical mass. What I’ve observed in the world of Android is some very good apps starting out there and then going cross-platform and reaching into world of iOS to gain a larger audience. Caustic is an excellent example of this. It’s an amazing app that started out on Android then moved over to iOS.

Of course the biggest problem for Android is, and has always been, latency. Whilst there have been solutions to this they’ve been contingent on specific hardware, like the Samsung solution, or very app-specific.

I still have hopes that Android will become a more popular mobile music platform, and it is possible, but it never seems to be really on Google’s agenda or at least not very high up.

About Windows Phone / Surface etc:

I still have an old Windows Mobile device which I use every now and then. I never moved to Microsoft’s newer mobile operating system, called Windows Phone, and I never owned a Surface, although I’ve played with them a bit here and there.

I’ll cover Windows Mobile (Microsoft’s original mobile OS) in a moment, but here I’ll concentrate more on what they’re doing now.

When Microsoft made the initial move from Windows mobile, a lot of developers were annoyed. The move meant not just a change to their code for a new version of the OS, but a complete re-write of apps from the ground up. No one was happy and as a result no developers (that I’m aware of) moved their apps to the new OS.

Since then I’ve periodically taken a look in Microsoft’s App Store for their mobile OS to see if there was anything of interest and always found it wanting. As for the Surface, that seemed to hold some promise and I was contacted by Pete Brown from Microsoft who was very excited about the possibilities for music. Again, this hasn’t seemed to meet expectations. I’m not sure why though as in theory it is a very capable device.

Perhaps as Windows 10 rolls out there will be more interest. Perhaps Microsoft will get a real mobile strategy in the future. Time will tell, but for now it holds little interest for me, which, in my opinion, is a missed opportunity.

About Palm OS:

Whilst it’s only fair to say that Palm OS is a legacy operating system, I still think it’s worth a mention. Not least because it is where the journey started for me, but also because it is still a very capable operating system for music, albeit there are really only a handful of useful apps available for it. However, one of those, Bhajis Loops, is still one of the most fully featured mobile music making apps ever, in my opinion. It’s well worth taking a look at even though the OS is long dead and not supported in any way. I’ve written a number of pieces about Bhajis Loops (examples: “My 24 apps for Christmas: 24 – Bhajis Loops and Microbe” and “Turn £50 into an Amazing Mobile Music Studio”).

About Windows Mobile:

Not to be confused with its successor, Windows Phone, Windows Mobile was actually very useful for mobile music, and, in its day had some truly amazing apps for creating music. The best of these was almost certainly Griff. Griff had a full plugin architecture together with synthesis, sampling, and mix automation. It was way ahead of its time, but when Windows Mobile got dumped by Microsoft, it came to an end. It was a great shame. There were a number of other music-making apps for Windows Mobile, but Griff was the by far the best.

About the mobile OS that didn’t see the light of day, Capers:

Capers was intended to be a replacement for Palm OS. A real mobile operating system for music. It was pretty much MIDI-based and had a huge amount of promise to do some truly innovative things on a Palm OS device. The developer did release some demo apps to show what it might be able to do, but apart from these nothing else ever came about. Which was a real shame. There was some talk of making Capers open source some time ago, but that too never came about.

If you want to know more about Capers here’s a link: palmsounds.net.

Field Work: This early Nagra handheld tape recorder exemplifies the connection between efficiency and design.

Weidenbaum: I said I wanted to move from software to hardware, and right on time, as this interview has progressed, you posted on PalmSounds.net a picture highlighting the beautiful engineering of a portable, handheld Nagra. Can you make a connection between pre-software mobile sound and the world of iOS and other digital tools?

Elsdon: Now that’s a good question. In many ways the iOS world often echoes a pre-app world. The Nagra is a good example, actually, as the recorder in Waldorf’s Nave iPad synth looks a lot like the Nagra. Even more than that there are apps that are in fact a direct port from their hardware forebears. Yamaha did this with their Mobile Music Sequencer app, which borrows heavily from the QY series of sequencers such as the QY10, 70 and 100. All amazing devices in their day (and still today, too, in my opinion) and worth replicating into the world of iOS, not just for nostalgia, but also because these were competent music making devices and translating them into the world of software makes sense. Another example is that of the Electribe and iElectribe from Korg, also Roland’s more recent Sound Canvas app.

Korg Before: The original hardware Elektribe

Korg After: The iPad adaptation, the iElectribe — note the tubes up top.

So I think that there is a definite line to draw between the world of hardware and how it has translated into software, be that in the iOS or desktop world. Of course the opposite is also true. I mentioned Bhajis Loops earlier. The creator of that seminal app for the Palm OS is now the man behind Mutable Instruments, maker of some very highly regarded Eurorack modules.

All Mod Cons: The recent work of the Bhaji Loops creator is the Mutable line of original synthesizer modules.

Weidenbaum: Over time, what have you learned about the audience for Palm Sounds, and how has that knowledge influenced your coverage?

Elsdon: That’s an interesting question. In the early days there was little or no interaction with the audience, and I think that was largely due to there not really being anyone reading, but I persevered, and it changed and more people started to read and then get in touch. Over time readership has altered as the medium has shifted: Blog, Twitter, Facebook etc, but one more or less constant has been the contact with people working in music technology. That could be developers, people in hardware, from established manufacturers, or those doing interesting things involving mobile music. One example being the SoundLab project which I became involved with as a direct result of Palm Sounds.

In terms of how it has influenced my coverage I can’t say that I think it has consciously. If anything I find myself shying away from the mainstream issues the more mainstream they get. As iOS music creation becomes mainstream I find myself less drawn to it.

Weidenbaum: Please talk a bit about SoundLab. Explain what it is and your role in it.

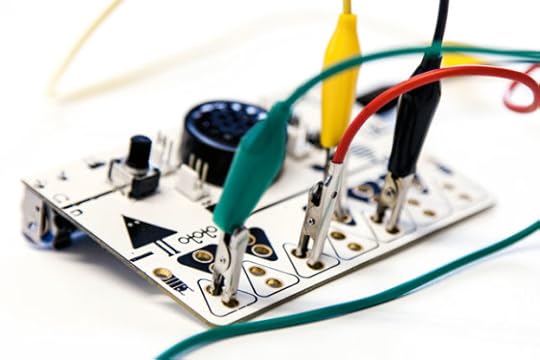

Elsdon: SoundLab aims to find simple and effective ways to help people with learning disabilities to express themselves musically and collaborate with other people using readily available musical technologies. We wanted to show how technologies can be brought together and combined to allow users new ways to make music.

As for my role in SoundLab, well, it covered a number of different things, like planning out some of the phases of the project, being involved in the workshops where we tested a wide range of technologies and apps, and being a part of a number of big public events too.

The other thing I’ve been doing with SoundLab is getting the project known in the music-technology community by talking to a lot of the best known manufacturers. We’ve had really good responses from people like Moog, Ableton, Korg, IK Multimedia, and Native Instruments. We’ve also been really lucky to work with a number of smaller music tech companies like Nu Desine, who make the Alphasphere, Dentaku who Kickstarted the Ototo board, Mogees and their app/hardware combo, and lots of other smaller companies too.

Clip ‘N Play: The Ototo, which can make music from just about anything

It’s been really interesting to see how people in the music technology world react to the needs of people with learning disabilities. In fact, we’ve had a fantastic response overall.

I got involved in SoundLab because one of the project leaders was a reader of PalmSounds and decided to get in touch to see if I would be happy to get involved in the project, and, one thing lead to another. In fact this is how I’ve got involved in a number of projects over the years.

In many ways I think that the work I’ve been doing at SoundLab is really an extension of how I’ve always thought about mobile music. It’s about accessibility and immediacy, and those ideas apply even more so in projects like SoundLab.

If anyone wants to know more about the project, the site is makeyoursoundlab.org.

Also, these videos might be of interest, both on YouTube: “Welcome to SoundLab” and “Heart n Soul: Who We Are.”

Weidenbaum: The second is the “mainstream” comment. I wrestle with that, too, in terms of music. Part of it in apps, I think, is that just because a lot of people buy an app, they aren’t necessarily using it, so sales aren’t a real gauge of what’s happening. But still, how do you track the environment while not covering the major players?

Elsdon: Yes, I do often skip over apps that I find are just iterations of existing ideas. Sometimes I find that a new synth app just doesn’t do anything really new. It might be a lovely synth but unless it really stands out from what is beginning to be a crowded space then it might not grab my attention.

Where an app is doing something really different it’s going to get my interest. One of the things I’m especially interested in at the moment is how developers are starting to implement 3D Touch. I think it has enormous potential for mobile music. There are already a handful of apps that have started down this road which is great. The downside is it’s making me want to buy an iPhone 6s!

But going back to the original question, I find that increasingly I’m drawn to apps that have a really different take on making music or sound. Apps that have a different take on creativity and expression. There are plenty of examples of these, but here are a few examples:

Figure — which was groundbreaking in its interface and ease of use for non-musicians

Thumbjam — for very similar reasons

Gestrument — also an amazing interface that allows people create amazing music without years of learning

I also really like finding apps that do something quite unusual. Apps by the Strange Agency fall firmly into this category, my favourite of which is The Donut. If you know it then you’ll understand what I mean, if you don’t, go take a look. Another couple of good examples of this would be Hexaglyphics, Sector, and Thicket:Classic. Ok, that’s three, but sometimes when you get started you know.

Anyway, my point here is that there are some truly genius apps around which have a completely different take on sound and interface, and, given the choice, I’d rather spend my time with one of those than something that looks like lots of other synth apps, and probably sounds very similar too.

However, I think that the creativity involved in creating a truly innovative music making app is very similar to the creativity involved in crafting a great piece of music. Really innovative apps bring something new to your workflow and enhance your own creativity. They’re more than just tools, they help and inspire.

It isn’t to say that the mainstream or large-scale app developers don’t produce innovative apps. They do. One example of this would be Gadget from Korg. That was a fantastic surprise and is a wonderful, creative tool. So I’m not sure that I particularly ignore the mainstream in terms of large companies. Instead, I think I actively seek out apps that display innovation and new ways of making music, connecting the app world to the physical world.

Weidenbaum: Have you noticed anything about apps made by coders who happen upon music as a subject, versus apps made by music-minded people who then learn to code or engage with coding resources to achieve their goals?

Elsdon: Well, yes, there have been a few people who have made the jump into coding as a result of either not finding the app they really wanted or just wanting to have a go. Often with apps developed by people who are already musicians you find have more attention to detail and more focus on the purpose of the app. However, I have to say that the majority of serious music apps (and I know that’s a difficult classification to make) are already made by people who like making music. I guess that this is the same of good games: they tend to be made by people who like games.

There are of course apps that hit the app stores that just don’t stack up at all. In the early days of iOS it was radio apps, and there are still hundreds of those around, but there are an increasing number of apps that seem to be cashing in on the mobile music world. I tend to ignore these though. It isn’t a huge phenomenon as in general the community can see when an app isn’t going to work with their workflow.

Weidenbaum: What have you observed about the pricing of apps, about dollar amounts, and occasional sales and promotions? Is there any sort of clear correlation between cost and complexity of an app. We’ve discussed inter-app functionality, like via Audiobus, but do you have any thoughts on in-app purchases

Elsdon: App pricing is a difficult area. To a large degree it has calmed down in the last couple of years, if not more. Whilst on the whole app prices are lower for mobile than for desktop, within the iOS — and to a degree Android — worlds there is no real consistency in pricing. For example, there are apps which are either free or only one step above that ($0.99) which vastly outstrip other more expensive apps in terms of their functionality. There are apps that are charged at $10 or more that I’d expect to see at around half their price.

Often you’ll see apps that launch at a high (respectively) price and then seem to follow a steady series of price drops to find their actual market price. One exception to this is Korg’s apps, which are amongst the most expensive in the iOS app store. They usually do at least one sale a year, but other than that they stay at their normal price.

A more recent pricing technique that seems to have gained popularity is the “launch price.” Often an app will launch at a 50% discount for the first week or two and then go up to its “normal” price after that. This is following the logic that most apps will make most of their money in the first month of launch. Prompting a sense of urgency for the user to get the new app at the launch price seems to work a lot of the time.

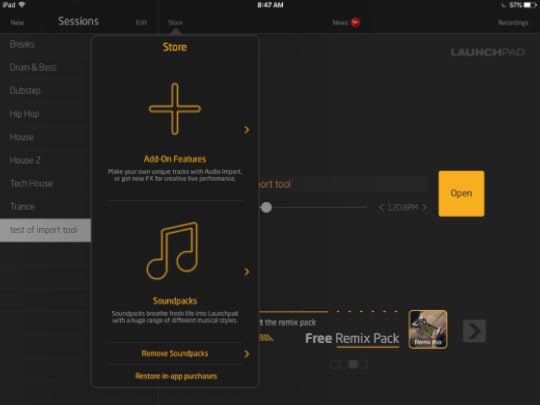

Cache Cow: An example of in-app purchases, this is the “store” within the Launchpad app for iOS.

On in-app purchases (or IAPs), these were treated with a large amount of skepticism when developers first brought them to their apps. I think a lot of this was to do with what was offered early on. Many of the first IAPs were sample packs and the like. These have evolved since IAPs were introduced and now I think they’re treated more reasonably. Also, there have emerged a few “taboo” IAPs. These are things like MIDI, Audiobus compatibility, and possibly a few more.

More recently we’ve seen more expensive IAPs come from Korg in their Gadget app. No one seemed to complain about these, which is interesting. Steinberg have done the same with their Cubasis app, and seem to have had a positive reaction.

I think that the biggest issue in iOS pricing is upgrade pricing. It’s the thing that Apple has never addressed. Developers can’t keep on delivering free updates to apps. It doesn’t make any commercial sense at all. Desktop software makers are used to charging for upgrades. It makes sense. Users are comfortable with this, but in the iOS world this doesn’t exist. Many developers have decided to issue new versions of their apps. So Intua released BeatMaker 2 as a new app entirely and charged a premium price for it. Apple gives them no way to offer a discount to existing users, which is a massive missed opportunity in my view. It causes developers issues as they need to maintain, at least to a degree, the previous versions, whilst also creating a new app to keep themselves afloat.

I think that users are coming to terms with this now, but there is still some resistance. It isn’t ideal, but without a real platform solution, developers have no real alternative at all.

Weidenbaum: What is your schedule like? I think you tend, for example, to post videos and audio of apps on the weekend. What is your system for tracking information in such a quickly changing and vast field, and what is your personal schedule like for maintaining and updating PalmSounds.net?

Elsdon: Well, as for a system, it sort of evolves over time. In fact, I use a lot of different systems to track information. Lots of feeds, lots of people on Twitter, and Facebook, and a few other things besides. However, it does change and flex over time.

My personal schedule changes a lot at the moment. So some days you’ll find that there’s nothing new on PalmSounds, and other days there’ll be lots and lots. Right now, things are pretty variable though, so there’s plenty of peaks and troughs with the site. My expectation is that it’ll be like that for some time to come.

More from Elsdon at palmsounds.net.

Image sources: Borderlands, Palm III, Casio VL-1, OP-1, Bhajis Loops, Nagra, Mutable Instruments, Ototo, Propellerheads, Electribe, iElectribe, Audiobus.

November 7, 2015

What Sound Looks Like

This is an extreme close-up of a doorbell, or of what had been a doorbell. It is/was the sixth of six buzzers at the entrance to a small apartment building near Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. The other five buzzers look and presumably work fine. This one, however, has been gutted. It has, like the others, a handwritten number next to it, paint on weather-proofed metal. But its button and the circular casing are long gone. They yield a small bit of transparency, not into the apartments themselves, but into the wiring. Small, worn, colored cabling is viewable within, as are tiny scraps of paper. Also evident: dirt and insects. The result is an especially tidy version of the classic urban-development infill story: What had been a buzzer to a residence has itself become a residence.

An ongoing series cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.