Mark Sisson's Blog, page 71

June 9, 2020

Training for “The COVID-19”

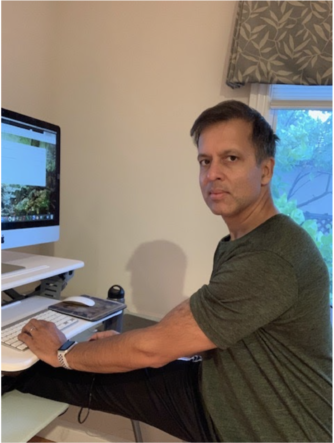

Today we welcome guest author Dr. Ronesh Sinha, internal medicine physician and expert on insulin resistance and corporate wellness, author of The South Asian Health Solution. He is a top rated speaker for companies like Google, Oracle, Cisco and more. Check out his media page for lectures, interviews and articles from Dr. Sinha.

Today we welcome guest author Dr. Ronesh Sinha, internal medicine physician and expert on insulin resistance and corporate wellness, author of The South Asian Health Solution. He is a top rated speaker for companies like Google, Oracle, Cisco and more. Check out his media page for lectures, interviews and articles from Dr. Sinha.

Most of us have been sheltering-in-place for a few months now, and we have evolved into an unprecedented state of fear and hyper-vigilance in this pandemic. After a long period of being cooped up, we are now gradually released into the wild, which introduces us to a whole new level of anxiety. Public health recommendations appear to be flip-flopping regularly, and we are learning on the fly as the situation evolves.

In today’s post, I’d like to share some thoughts on how we can regain some control of our lives. Rather than duck and cover for several more months, we can face this beast head-on. I don’t mean being careless and reckless and not following social distancing and hygiene protocols. Instead, we can adopt a mindset that we will do what is necessary to minimize our risk of a severe COVID-19 outcome. I titled this post “Training for the COVID-19” to help you reframe this pandemic in your mind, and view it like a warrior approaches an enemy on the battlefield or an athlete faces an opponent in a competition.

Cognitive Reframing Coronavirus: From Fear to Readiness

Cognitive reframing isn’t just some touchy-feely behavioral technique. Viewing the world through a more positive lens has a beneficial impact on your immune system, which is potentially relevant to COVID-19. One study shows that participants who were cognitive reappraisers, identified by a 10-item Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, and then exposed to an experimental cold virus (rhinovirus not coronavirus) had reduced nasal cytokine release compared to individuals who were emotional suppressors.1 As you’ll learn in a moment, excessive cytokine release is a crucial mechanism by which COVID-19 imparts significant lung and tissue damage. As with rhinovirus, the nose is a primary portal through which coronavirus accesses our body.

So as you read this post and continue to keep getting bombarded by pandemic news media, remember the lens through which you view this content. Your external world has a direct impact on how your immune system might respond to an infection like COVID-19. Let’s start by summarizing COVID-19’s basic operating system for you.

Fear of the unknown is one of the single most significant stressors to our nervous system. I want you to read this with the attitude that “I will acquire the knowledge I need to understand this virus and defend myself and my loved ones against its effects.” Rather than, “Oh my God, the extra fat around my waistline will be the death of me.”

One way I view our pandemic and its relationship to our individual health is by splitting it into external viral load vs. internal cytokine load. Refer to the image below.

Excerpt from the Free COVID Guide

Excerpt from the Free COVID Guide The left side of the image shows how the COVID-19 virus enters a cell by gaining access through the ACE-2 receptor, which hijacks our cell’s reproductive machinery (think 3D printer). Then, it makes copies of itself. This is the external viral load.

The right side of the image illustrates our immune system response. NLRP3 is an alarm sensor in our cells that gets turned on when an infectious pathogen like COVID-19 knocks on the door of our cells, specifically by attaching to the ACE-2 receptor. Once the alarm sounds, a rush of immune system chemical messengers called cytokines comes rushing inside to thwart the attack. NLRP3 is a critical gatekeeper to the cytokine surge. If you want to learn more about how it works and how it’s connected to other common health conditions, watch my 4-minute explainer video here.

The volume of this cytokine response is what I refer to as the internal cytokine load. An optimal cytokine load would be sufficient to thwart an attack by an outside offender. Still, an overzealous cytokine response (aka “cytokine storm” or “fire”) would damage and destroy our cells through a process called pyroptosis, which is literally cellular death by fire.

I want to highlight that cytokines are not the enemy in this process and are an essential part of our innate immune response. It’s excessive cytokine release that inflicts damage and destruction. Fortunately, our cytokine response is something that we can control through targeted lifestyle changes. Just a reminder that these are the same cytokines I mentioned at the beginning of the post, which were released in excess amounts in the noses of emotional suppressors vs. cognitive reappraisers exposed to the cold virus. So what’s the link with obesity?

Obesity is so intimately tied to our risk of a severe COVID-19 outcome that I refer to this association with the term, “Covesity,” which I write about in detail here.2 Specifically, it’s the central visceral fat (aka “belly fat”) that is an especially insidious storehouse of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-alpha, which fuel the cytokine fire.

Another reason fat cells may increase risk is through the ACE-2 receptor shown in the above image. Fat cells have an abundance of these receptors, and their affinity for COVID-19 means they may serve as a viral storehouse. So fat cells not only provide more entry points for COVID-19 but also ready access to an ammunition supply of cytokines.

ACE-2 also puts the brakes on the enzyme angiotensin II, which, if left unrestrained, can contribute to the more severe manifestations of COVID-19 (like acute lung injury, heart damage, etc.). Angiotensin II levels appear to rise in severe COVID-19 infections due to a downregulation in ACE-2 (the “brake pedal” for Angiotensin II). In the case of obesity, angiotensin II increases further by visceral fat cells that secrete angiotensin II in addition to the cytokines we just discussed.

So fat cells provide the fuel to ignite the cytokine fire and release excess amounts of angiotensin II, which can further provoke damage and destruction of vital organs. We also know that obesity increases our risk of chronic health conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure, which are additional risk factors for a more severe COVID-19 infection.

Again, I don’t want this information to set you into a state of panic if you are struggling with extra weight or other COVID-19 health risks. I assure you that this is not a disease where the only people left standing at the end of the pandemic will have single-digit body fat percentages and 6-packs. Fit, lean individuals who are experiencing chronic stress and sleep issues might have a higher risk than slightly more substantial, less fit individuals who are physically active and better manage their sleep and stress. No matter where we are in our health journey, we need to identify our own gaps (physical, mental, social, etc.) and make key changes that will markedly reduce our cytokine load and overall risk.

One common question I get during lectures and in the clinic is, “how do I know if my fat is the inflammatory type?” This is an important distinction. Some of us might be above the recommended BMI (body mass index) cutoff, but not have as much inflammatory adipose tissue. In contrast, others might be underweight but have visceral fat cells packed with proinflammatory cytokines. This is why body weight and BMI can often be a misleading marker. Some clues that you might have more inflammatory adipose tissue are below. Just a reminder that NLRP3 is the alarm sensor that COVID-19 turns on and triggers the cytokine surge.

Increased belly fat: ethnic waistline cutoffs are here and to learn more about body fat and the impact of ethnicity, read my post here.

High triglycerides: aim for triglyceride levels to be closer to 100 mg/dL or below

Low HDL (healthy cholesterol): males should target an HDL>40 mg/dL and for females, HDL>50 mg/dL

High triglyceride/HDL ratio is even better than looking at individual triglyceride and HDL, aiming for a ratio of less than 3.0 (lower the better)

Elevated blood glucose (prediabetes, diabetes)

High blood pressure: More recent research is showing that hypertension may be an inflammatory condition and the NLRP3 inflammasome might be a key switch as discussed in this study.3

Fatty liver: Learn more by reading my post here. 4 This mouse study 5 is linked to NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) and blockade of this pathway leads to regression of fatty liver.

Elevated hsCRP: this is a test for inflammation that is not indicated in all patients and can give an elevated result for various reasons. Many of my patients with insulin resistance have elevated hs-CRP, and research 6 mentions the strong link between CRP and NLRP3, where NLRP3 appears to be predictive of elevated hs-CRP levels.

Some of you might recognize many of the items on this list as being criteria for a condition called metabolic syndrome, 7 whose root cause is insulin resistance. Many of us have become disconnected from our health care providers and systems as a result of shelter-in. I strongly encourage you to track the risk numbers applicable to you. For example, I’m putting a growing number of my at-risk patients on continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), especially given studies 8 showing a strong correlation between glucose control and COVID-19 severity. I wrote a detailed post on how to get your health care provider to order a CGM here.

I’m seeing many patients losing track of their waistlines since they’ve been living and working in stretchy pants for months. It might be time to dust off those jeans or work pants, so you regain some waistline awareness. Tracking your risk numbers and making appropriate lifestyle changes is a powerful way to regain control of your health.

Lifestyle Changes

So now that you understand COVID-19’s operating system and COVID-specific risk factors more logically and less emotionally, how do you specifically train for the COVID-19? First, we need to understand what type of event we are preparing for. Is this an event based on strength and power, or is it more of an endurance event?

We know major target sites for COVID are the lungs and heart. When you talk to patients that have had a moderate or severe outcome, they report feeling like being dragged underwater or dropped on top of a mountain and asked to run a marathon. There is a distinct sensation of what we call “air hunger,” and this is something we can actually train for without having to live at least 7,000 ft above sea level.

In other words, surviving and even thriving through COVID-19 likely depends on how fast you can walk or run a mile rather than how much you can squat, deadlift, or bench press. We can improve our tolerance to low oxygen (aka hypoxic) stress if we can improve our aerobic fitness through movement and exercise. Tying this back to cytokines and inflammation – hypoxic stress is a powerful trigger for inflammation. It is mediated by several different chemicals referred to as HIFs (Hypoxia-Inducible Factors) as reviewed in this study. 9 This makes sense given we can live around three weeks without food, three days without water, but only 3 minutes without air.

Any time our body senses a lack of oxygen, the resulting cytokine surge’s intensity and volume are significant. This is a medical code blue or a five-alarm fire signal to our immune system, and there’s a link to our body fat. This study 10 shows that hypoxic (low oxygen) stress specifically unlocks cytokines from fat cells. So, if you are carrying extra inches around the waist and are also aerobically deconditioned, then that’s a double whammy for fueling a cytokine storm.

Now that we understand the type of event we are preparing for, let’s turn to our training plan. I have three main principles for COVID-specific training, which I outline as the “ABCs.” “A” is for Activity, “B” is for Breathing and “C” is for cardio. Most of my patients might be doing one or two of these, but rarely is anyone doing all three. I strongly recommend that you do all three of these to improve your resilience to COVID-19.

Activity: Moving Throughout the Day

For activity, I’m referring to regularly staying active throughout your day since interrupting prolonged sitting has been shown in numerous studies to increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines. You might know this already, but our COVID-19 environment takes on a whole new level of significance. Mark refers to these as “microworkouts”, which you can read about in his post here. I refer to it as exercise snacking (not my term). I am teaching my patients to stock their “exercise pantry” with at least 10 different movements they can perform throughout the day. I have 20+ different work positions and mini-exercises that I do while I’m on business calls or doing creative work.

Personalize your pantry to target problem areas. For example, I have struggled with tight hamstrings for many years, so I’m always working in positions like the one below, which has made a huge difference.

Now, after hours of work, when I decide to do something more intense, my legs are limber, warmed up, and ready to go. Work to me is a combination of a light interval workout with flexibility and warm-up drills that have my body prepped and ready to transition to something more intense at any given moment. My patients that do this are more energetic during work hours and less sore after workouts because they are already warmed up.

For more examples of my work positions, refer to the end of my free Covid Survival Guide here. Since I’m doing lots of remote patient visits now during our medical group’s shelter-in, I’m teaching some of my patients how to integrate workouts into their work hours.

Deep Breathing Exercises

Breathing is next on the list and is the item that is most commonly overlooked from my ABCs. Improved breathing is something we can easily practice at rest as well as during exercise. I’ve been teaching many of my patients to nasal breathe, nasal hum, and even do exercises like alternate or single nostril breathing. Alternate nostril breathing is one of my absolute favorites and I made a video on how to do it here. Even Hillary Clinton swears by it here in her interview with Anderson Cooper.

These types of breathing exercises help activate our diaphragm, which turns on our parasympathetic nervous system (rest or relaxation response) and also improves our breathing mechanics so we can improve oxygenation at rest and during exercise. Recall how I mentioned the sensation of breathlessness or air hunger as being a tremendous stressor to our nervous system that can open the cytokine floodgates, especially from fat tissue.

Despite being a lifelong exerciser, I (like many of my patients) have struggled with aerobic fitness and only recently discovered that a major root cause was a poorly conditioned diaphragm. I’m also a recovering emotional suppressor, and we suppressors tend to bottle up our emotions and breathe more from our chests than our bellies. Emotional suppressors also produce more cytokines and I explain the link in this video here, along with my own strategies on dealing with emotional suppression.

Finally, recall that I mentioned how coronavirus appears to produce a sensation of being dragged under water or dropped on top of a mountain. The physiology of COVID lung disease is complex, but appears to mimic some form of high altitude lung disease. As a result, I’m actually training for it like a high altitude endurance event. Unfortunately I don’t live above 7,000 feet, but am using my high altitude training mask as a substitute. These masks all sold out on Amazon after I did a few interviews and blog posts on the topic, but you can use your medical mask as a hack.

Nasal breathing, single nostril breathing, or using a mask are ways of limiting oxygen intake so your lungs adapt to exercising in a slightly hypoxic environment. I call this “oxygen fasting” which you can read about in more detail in my Oxygen Fasting and Biohacking Breathing post. If you’re not used to it, it will feel suffocating at first, but then you adapt. The reason this is important is that if your lungs are exposed to an infection like novel coronavirus, because you are partially adapted to a lower oxygen environment, it will not be a novel threat that causes a huge surge in stress hormones and cytokines.

Interestingly, right after I submitted the draft for this post I noticed MDA released a guest post on nitric oxide by Nobel Prize winning scientist, Dr.Louis J.Ignarro, where he mentions nasal breathing. I am a HUGE fan of nasal breathing and nasal humming for optimal health, and wrote a detailed post on this a while back which you can read here or just watch my short video on nasal breathing and nitric oxide here.

Back to biohacking breathing, I actually have been using masks as a training tool in my patients. I had an older high risk female patient who absolutely could not tolerate wearing an N95 mask for even a few minutes. By doing some breathing exercises and viewing her mask as an opportunity to improve her aerobic fitness, she increased her “mask tolerance time” enough so she can effortlessly grocery shop and do other errands with her mask in place. This allows her to minimize external viral load exposure by allowing her to comfortably wear her mask more often when needed, while also improving her internal cytokine load and aerobicfitness.

Cardio: Building your Cardio Fitness for COVID-19

Cardio is the final link in the training for COVID-19 protocol, and I already alluded to some of this in the breathing section since the two are intimately linked. The only thing I would really emphasize for type A exercisers like myself, is to not overtrain, especially in our current environment. Mark’s personal story as a former burned out world class endurance athlete definitely had an impact on how I view exercise and fitness. He also introduced me to the work of Phil Maffetone, whose heart rate principles I use and prescribe to patients to help them dose exercise just like we would dose medication. Yes, exercise (like food) is medicine and must be dosed properly to optimize immune system function.

As a result of shelter-in, some of my patients are under-dosing exercise with more sedentary behavior, while my Type A exercisers are overdosing on more high intensity workouts. I am using the extra time to work on range of motion and recovery so I can perform better when I do train. I’ve also been consistently breaking personal bests with daily lower intensity walking milage.

For many of my patients who spent long hours doing the tech commute in Silicon Valley, I tell them that regaining their mornings back can be a gift if they use it the right way. Instead of turning on their car engine to drive to work, they can now fire up their mitochondrial engine first thing in the morning and get some physical activity. This keeps their metabolism revved up so their body’s burning more fat throughout the day, especially if they can do this morning activity in a fasted state.

What About Resistance Training?

You might be asking why I didn’t call out weight training here in my ABCs? I guess I could have added a “D” for deadlifts which I am doing twice a week, but I really wanted to highlight the mechanics and physiology of COVID-19 which makes it prey on the aerobically challenged. If this were a pathogen that tore through skeletal muscle, I’d prioritize my lifts over longer cardio sessions. I love lifting weights and I’m not dissuading individuals from doing weight training, but maybe doing it a little differently than stacking progressively heavier plates on bars.

I’ve encouraged my patients who are no longer going to a gym to focus more on plyometrics and body weight training. A new fun goal I’ve set for myself is increasing my vertical leap so I can be more competitive in grabbing rebounds when I face my teen boys for one-on-one basketball. I also encourage you to set goals aligned with fun and pIay, rather than the more rigid goals of increasing your 1 rep max (1RM). I know I likely compromised my 1RM on weights, but I’ve added a spring to my walking step and running stride I didn’t have before, and that has improved my overall aerobic fitness and energy levels. My patients are also learning different exercises that they can now independently do at home or outdoors, so they are less tethered to an indoor gym or class schedule, and can now get a workout in anytime, anyplace.

A final thought I want to share with you that will hopefully help you view this new world we are living in with a brighter lens is the legacy you plan to leave after we are through this pandemic. Imagine if you had a journal you dusted off from your ancestors who lived through the 1918 pandemic. How inspiring would it be to read about how they endured that event, especially without internet and doorstep delivery of food and virtually any item we need with a few taps of our phone. We complain about the “fear of the unknown,” but we know so much more on a minute-to-minute basis about this virus and its impact than any of our pandemic predecessors who truly lived in the dark.

I’m actually keeping a pandemic journal and recommend you do the same. Do you want your future generations to know that you spent this period predominantly in fear, glued to your phone, hiding under the covers, and neglecting your health by baking every single day and avoiding exercise and all forms of social contact? Or would you rather share your fears and vulnerability openly, but then provide hope with all of the things you did to train for the COVID-19, by supporting your own physical and emotional health, and that of your family and surrounding community. Your actions now can provide courage and hope for future generations who will inevitably face their own pandemics and epidemics. Lift yourself and others out of this period, and be their inspiration. I wish all of you peace, safety and optimal health. Grok On!

For more information on health and access to my free COVID-19 survival guide and resources being used by Silicon Valley companies and readers worldwide, go to this page, and follow me for cutting edge science and daily tips on Instagram @roneshsinhamd.

References https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7057831/https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/beware-of-the-covesity-covid-obesity-pandemic/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4418473/https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/is-your-liver-fat/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2... shows NLRP3https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30761006https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/metabolic-syndrome-what-cholesterol-guidelines-should-really-focus-on/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/05/200501120102.htmhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

The post Training for “The COVID-19” appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

The Complete Magnesium Manual

Magnesium is an essential mineral that doesn’t get the attention it deserves. You’d be hard pressed to find any activity in the body that doesn’t use magnesium in some way. It has literally hundreds of functions.

Magnesium is an essential mineral that doesn’t get the attention it deserves. You’d be hard pressed to find any activity in the body that doesn’t use magnesium in some way. It has literally hundreds of functions.

Cellular energy production, protein synthesis, DNA and RNA synthesis, and cell signaling—which controls the secretion of certain hormones, among other things—all depend on magnesium. It plays an important role in ion channels that allow nerves to fire, potassium and sodium to cross cellular membranes, and muscles to contract. Production of ATP, the energy currency of the body, depends on magnesium. Your heart beats rhythmically thanks to magnesium.

Not surprisingly, then, magnesium deficiencies seem to factor into a wide range of health issues. Let me tell you about some of the biggies.

Health Issues Related to Magnesium

Before getting into the details, I want to draw your attention to a few challenges with the research literature. One, which I’ll return to later, is that magnesium levels in the body are tough to measure.

Second, lots of studies try to link dietary magnesium intake to specific health outcomes. Foods that contain magnesium, like leafy greens and fish, also contain a host of other vitamins and minerals, fiber, sometimes amino acids. This makes it hard to isolate the effects of any single nutrient.

The way magnesium intake is measured, usually with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) or food diaries, is also fraught with error. I don’t put too much stock in studies that correlate dietary intake with any specific health outcome. Correlation doesn’t prove causation anyway, as you know. I’ll mention them here to give you a complete picture of what researchers are working with. Ideally, though, I like to see randomized controlled trials.

Magnesium and Inflammation

It’s increasingly clear that inflammation is at the heart of many, if not most, chronic disease states. Studies have shown that people who consume less than half the recommended daily allowance of magnesium have higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation.

11 Magnesium intake negatively correlated with CRP in two large observational studies, the Women’s Health Initiative Study 12 and the NHANES Study 13.

These observations are supported by experimental studies which, according to a 2018 meta-analysis. confirm that magnesium supplementation lowers CRP levels14

The Link Between Heart Health and Magnesium

There are many well-documented metabolic pathways through which magnesium can affect heart health. Magnesium may reduce heart disease risk by reducing arterial stiffness, improving endothelial function15, and/or lowering chronic inflammation. It also inhibits platelet aggregation, which is itself a risk factor for heart disease.16

Several large prospective studies have correlated higher magnesium intake or higher magnesium levels in the blood with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.17 18 19 20 Magnesium deficiency is considered a risk factor for cardiac arrhythmia and hypertension (high blood pressure).

A recent review of the available evidence concluded that while it’s fair to say that magnesium intake is important for cardiovascular health overall, more randomized controlled trials are needed to understand the particulars better.21

It’s also too soon to conclude that supplementing would have any specific effects, although there is some promising evidence when it comes to hypertension. Two meta-analyses found overall positive, though inconsistent, benefits for lowering blood pressure.22 23 Magnesium supplementation can also be used alongside blood pressure meds to increase their effectiveness.24

Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Sensitivity

Magnesium affects how cells take up glucose out of the bloodstream, glucose oxidation, and insulin sensitivity.25 Researchers estimate that 25 to 38 percent of type 2 diabetics are deficient in magnesium.26

Diabetes and magnesium deficiency is a vicious cycle. Prospective studies suggest that people with lower magnesium intake are at greater risk for insulin resistance27 and developing type 2 diabetes28. Once they have the disease, they lose more magnesium through urine, making them more susceptible to ongoing magnesium deficiency. This then exacerbates the problems of poor glucose management and insulin resistance, increasing the chances of diabetic complications.29

A 2016 review and meta-analysis showed that magnesium supplementation improves fasting glucose in folks with type 2 diabetes. Among folks who are at risk of developing the disease, supplementing leads to better glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. However, the authors also noted a high degree of variability in the data.30 A second meta-analysis found better insulin sensitivity and fasting glucose, particularly when supplementation lasted at least four months.The results of this analysis also indicate that the effects are greatest among people who start out with low magnesium.31

Magnesium and Bone health

Low magnesium is associated with low calcium, impaired parathyroid hormone secretion, low vitamin D, and inflammation. This adds up to a perfect storm when it comes to developing osteopenia and osteoporosis. On the other hand, chronically high magnesium levels may demineralize bones and put people at risk for fracture.32

In correlational studies, dietary intake is positively associated with bone mineral density in postmenopausal and premenopausal women 33, older men and women34, and older white, but not Black, folks 35. However, magnesium levels in the blood don’t consistently correlate with bone mineral density like you’d predict.

Several studies have shown that supplementing improves bone health in young men,36 postmenopausal women,37 and healthy girls.38

Magnesium and Migraines

A fair number of studies find that migraine sufferers have lower magnesium levels than people who don’t get migraines.39 Although migraines are still not well understood overall, scientists have proposed a variety way low magnesium contributes to migraines, including by affecting inflammation and vasodilation, among others.

Research also points to magnesium supplementation as an effective option for managing migraines. Children40 and adults41 with a history of migraines reported fewer and less severe episodes when supplementing with magnesium. One impressive study found that when people went to the emergency room with migraines, magnesium provided even more relief than drugs.42

The American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society agree that magnesium is probably effective for the treatment of migraines.43

The authors of a 2012 paper even went so far as to argue that all migraine sufferers should be taking magnesium.44

Magnesium Could Help with Depression and Anxiety

Magnesium has many complex actions in the brain, including affecting neurotransmitter and hormone release and neuronal firing. Although research provided promising evidence a century ago that magnesium can be used to treat depression, nobody took much notice.45 Even now there aren’t a ton of studies.

Depressive symptoms seem to correlate with dietary intake.46 Supplementation may alleviate symptoms of mild-to-moderate47 48 and major depression.49

In a 2017 review of 18 studies, about half reported that magnesium supplementation alleviated anxiety symptoms.50

But Wait, There’s More!

More research is needed, but magnesium may be a factor in:

Restless leg syndrome51

Fibromyalgia52

PMS53

ADHD54

What about Sleep?

Magnesium supplementation is often touted for sleep, but there’s actually not that much direct evidence that it helps. One small study involving 12 elderly participants concluded that magnesium supplementation enhanced sleep quality.55 In another study of 46 elderly insomnia patients, eight weeks of magnesium supplementation significantly improved sleep quality and quantity.56 That’s about it.

Still, many sleep aids contain magnesium because it is needed to convert 5-HTP to serotonin, which in turn converts to melatonin. It also blocks NMDA receptors in the brain and promotes GABA, both of which are important for sleep. (These same mechanisms may explain why magnesium helps with depression, by the way. Some scientists have also suggested magnesium’s action on NMDA receptors is why it alleviates migraines.)

Exercise Performance

Magnesium plays a key role in glucose metabolism and energy production. Since glucose is mobilized during exercise, it makes sense that magnesium would be important. Research in mice shows that giving them magnesium increases the amount of available glucose during exercise. It also delays the accumulation of lactate in the muscles, which may prevent fatigue.57

The evidence for using magnesium supplementation to improve human performance is mixed. For example, in one study, male professional volleyball players were able to jump higher, and they had decreased lactate production, after supplementing magnesium for four weeks.58 Triathletes likewise improved their swim, bike, and run times.59 However, another study found no benefit for marathoners.60

Even if it doesn’t yield a performance benefit, though, it’s clearly important that athletes make sure their electrolyte intake is sufficient. More on that next week.

Normal Levels and Magnesium Deficiencies

It’s difficult to test magnesium levels. The most common method is a blood test. Normal serum concentrations fall between 0.75 and 0.95 mmol/L.

However, less than 1 percent of total body magnesium is in the bloodstream, and serum level is tightly regulated by the kidneys, as well as bone and intestines. Blood tests are poor indicators of total body magnesium levels. Your doctor may use a combination of blood, saliva, and urine tests if they suspect a severe deficiency. No single method seems to work very well.

Clinical deficiencies in healthy adults are rare, but data from the large NHANES study suggests that perhaps only one-third of Americans hits the recommended daily intake.61 If true, many people may be walking around with sub-optimal magnesium levels. People who are at greater risk for deficiencies include those with gastrointestinal issues such as Chron’s or celiac disease that interfere with nutrient absorption, diabetes, kidney disease, or who take certain medications. The elderly and people with alcoholism often have low magnesium

Severe deficiencies can be indicated by low calcium and potassium levels, and by non-specific symptoms like muscle spasms and vomiting. Mild deficiencies usually have no noticeable symptoms.

Recommended Intake

The recommended daily intake for adults is 310 mg for females aged 19 to 30, and 320 mg thereafter. For males, it’s 400 mg up to age 30, then 420 mg. Pregnant women need an extra 40 mg per day.

Does Diet Matter?

Possibly. If you’re following a keto diet, you should supplement with sodium, potassium, and magnesium. You need up to an additional 300 to 500 mg of magnesium per day.

I’ve also previously considered whether folks following a carnivore diet may need less magnesium from their food, perhaps because they consume less glucose or fiber than omnivorous types. I think it’s too soon to tell, although I’m open to the possibility.

Foods High in Magnesium

Some of the best Primal-friendly sources of magnesium include:

Leafy greens: spinach, Swiss chard

Dark chocolate

Nuts: almonds, cashews

Seeds: pumpkin, hemp, watermelon

Fish: halibut, mackerel, salmon

Avocado

In addition to food sources, as much as 10 percent of our magnesium intake comes from drinking water.62

How to Choose a Magnesium Supplement

As with any nutrient, it’s best to get magnesium from food. The Food and Nutrition Board of the US Institute of Medicine designates 350 mg/day as the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for supplementing.

When choosing a magnesium supplement, look for a chelated form, the ones ending in -ate. They have the best bioavailability. Magnesium glycinate and malate are both good choices. Magnesium citrate is probably the most common since it is inexpensive and widely studied, but it can have undesirable laxative effects for some people. L-threonate is particularly noted for its cognitive benefits. Avoid magnesium oxide unless you specifically want diarrhea.

Certain pharmaceutical drugs can interact with magnesium. Talk to your doctor, especially if you take medications for osteoporosis or HIV, if you are on a diuretic, or if you are prescribed tetracycline or quinolone antibiotics.

Can You Get Too Much Magnesium?

While magnesium toxicity is possible, it’s very rare. Most forms of magnesium will cause gastrointestinal distress before that point. Stick to recommended doses, though.

Transdermal Magnesium: Epsom Salts Baths and Magnesium Oil

Both epsom salt baths (magnesium sulfate) and magnesium oil sprays (usually magnesium chloride) are touted as alternatives for boosting magnesium levels. However, there is almost no research verifying that it is effectively absorbed through the skin.63 Still, many people use them for recovery from exercise, relief from pain or cramping, and as sleep aids.

If it works for you, by all means keep doing it. However, if you’re looking for a guaranteed way to increase magnesium levels, it’s safer to go with a supplement.

Some Important Things to Keep in Mind

We covered a lot of ground today. Before I let you go, let me point out a couple of things.

First, as with most—probably all—vitamins and minerals, there’s a sweet spot with magnesium. Too little is clearly bad, but trying to cram in more than you need is not good either.

That said, some of the experiments referenced here used doses that are well above the 350 mg UL for supplementation. Don’t go mega-dosing on your own, of course. On the other hand, if you’re considering using magnesium to help with a specific health issue, consult your doctor to see how much you might need to see results.

Though it’s clear that magnesium is a big-time player in optimal health overall, more research is needed to understand the specific benefits. My guess is that most Primal folks eating a diverse diet are getting enough magnesium. If you’re curious, use a food tracking app like Cronometer to see how much you get over the course of several days to a week.

Stay tuned next week. I’m planning to talk more generally about electrolytes and when and why you’d want to supplement. Let me know if you have any questions along those lines.

References https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7057831/https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/beware-of-the-covesity-covid-obesity-pandemic/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4418473/https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/is-your-liver-fat/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2... shows NLRP3https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30761006https://www.culturalhealthsolutions.com/metabolic-syndrome-what-cholesterol-guidelines-should-really-focus-on/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/05/200501120102.htmhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19658273/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15920065/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15930481/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6040119/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29709832/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1418832/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21703623/https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/93/2/253/4597608https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2939007/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6692462/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5852744/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28724644/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22318649/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20228010/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4586582/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9589224/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24084051/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5133122/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29758962/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27530471/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043661816303085https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3775240/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10617959/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10197575https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16274367/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9709941/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19488681/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995550/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25533715/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12786918/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18705538/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25278139/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3335449/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22426836/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19944540/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25748766/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28654669/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0899900716302441https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16542786/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5452159/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9703590/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27296515/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4161081/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9368236/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12163983/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3703169/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24465574/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24015935/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9794094/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1299490/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15930481/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9494787/https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/9/8/813/htm

The post The Complete Magnesium Manual appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 8, 2020

What Does It Mean to Be Fat Adapted or Keto Adapted?

When describing someone that has successfully made the transition to a Primal or Keto way of eating I often refer to them as “fat-adapted” or as “fat-burning beasts”. But what exactly does it mean to be fat-adapted? How can you tell if you’re fat-adapted or still a sugar-burner?

When describing someone that has successfully made the transition to a Primal or Keto way of eating I often refer to them as “fat-adapted” or as “fat-burning beasts”. But what exactly does it mean to be fat-adapted? How can you tell if you’re fat-adapted or still a sugar-burner?

As I’ve mentioned before, fat-adaptation is the normal, preferred metabolic state of the human animal. It’s nothing special. It’s just how we’re meant to fuel ourselves. That’s actually why we have all this fat on our bodies – turns out it’s a pretty reliable source of energy.

Here’s what you need to know about the benefits of becoming fat adapted, or keto adapted, and why it works with your biology.

Instantly Download Your Copy of the Keto Reset Diet Recipe Sampler

Are Being in Ketosis and Being Fat Adapted the Same Thing?

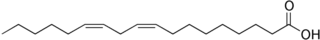

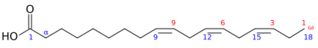

Fat-adaption does not necessarily mean you’re in ketosis all the time. Ketosis ketosis describes the use of fat-derived ketone bodies by tissues (like parts of the brain) that normally use glucose. That happens after you’ve depleted your glucose stores, and your body starts producing ketones for energy. When you’re in ketosis, you can usually detect ketones in your bloodstream.

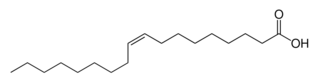

Fat-adaption describes the ability to burn both fat (through beta-oxidation) and glucose (through glycolysis).

The Disadvantages of Primarily Burning Sugar for Energy

To understand what it means to be fat adapted, it’s useful examine what it means to depend on sugar for energy.

It Is More Difficult to Access Stored Fat for Energy When You’re Dependent on Sugar

What that means is, when your body is primarily looking for sugar for fuel, your skeletal muscle doesn’t as readily oxidize fat for energy.

What happens when a sugar-burner goes two, three, four hours without food, or skips a whole entire meal? They get ravenously hungry. A sugar-burner’s adipose (fat) tissue even releases a bunch of fatty acids 4-6 hours after eating and during fasting, because as far as your biology is concerned, your muscles should be able to oxidize them. After all, we evolved to rely on beta oxidation of fat for the bulk of our energy needs. Once your blood sugar is all used up (which happens really quickly), hunger sets in, and your hand reaches into the chip bag yet again.

A Sugar Burner Doesn’t Readily Access Dietary Fat for Energy

As a result, more dietary fat is stored than burned. Unfortunately for them, they’re likely to end up gaining lots of body fat. As we know, a low ratio of fat to carbohydrate oxidation is a strong predictor of future weight gain.1

Sugar Stores Deplete Quickly And Need to Be Replenished Often

A sugar-burner depends on a perpetually-fleeting source of energy. Glucose is nice to burn when you need it, but you can’t really store very much of it on your person (unless you count snacks in pockets). Even a 160 pound person who’s visibly lean at 12% body fat still has 19.2 pounds of animal fat on hand for oxidation, while our ability to store glucose as muscle and liver glycogen (stored glucose) are limited to about 500 grams (depending on the size of the liver and amount of muscle you’re sporting).2 If you’re unable to effectively beta oxidize fat (as sugar-burners often are), you’d better have some quick snack options on hand.

Sugar Burners Use Stored Glucose Quickly During Exercise

Depending on the nature of the physical activity, glycogen burning could be perfectly desirable and expected, but it’s precious, valuable stuff. If you’re able to power your efforts with fat for as long as possible, that gives you more glycogen – more rocket fuel for later, intenser efforts (like climbing a hill or grabbing that fourth quarter offensive rebound or running from a predator). Sugar-burners waste their glycogen on efforts that fat should be able to power.

The Benefits of Being Fat Adapted

There are some compelling advantages to being fat adapted or keto adapted, which may move you to make the switch if you haven’t already.

People Who are Fat Adapted Often See Improved Insulin Sensitivity

A ketogenic diet “tells” your body that no or very little glucose is available in the environment. The result? “Impaired” glucose tolerance 3 and “physiological” insulin resistance, which sound like negatives but are actually necessary to spare what little glucose exists for use in the brain. On the other hand, a well-constructed, lower-carb (but not full-blown ketogenic) Primal way of eating that leads to weight loss generally improves insulin sensitivity.4

Being Fat Adapted Means You Go Longer Between Meals

A fat-burning beast can effectively burn stored fat for energy throughout the day. If you are fat adapted, chances are, you can handle missing meals and are able to go hours without getting ravenous and cranky (or craving carbs).

You Can Better Utilize the Fat You Eat for Energy

A fat-burning beast is able to effectively oxidize dietary fat for energy. If you’re adapted, your post-prandial (after mealtime) fat oxidation will be increased, and less dietary fat will be stored in adipose tissue.

When You’re Keto Adapted, You Always Have a Fuel Source

A fat-burning beast has plenty of accessible energy available in the form of body fat, even if he or she is lean. If you’re adapted, the genes associated with lipid metabolism will be upregulated in your skeletal muscles.5 You will essentially reprogram your body.

You Can Burn Fat While Exercising

A fat-burning beast can rely more on fat for energy during exercise, sparing glycogen for when he or she really needs it. As I’ve discussed before, being able to mobilize and oxidize stored fat during exercise can reduce an athlete’s reliance on glycogen. This is the classic “train low, race high” phenomenon, and it can improve performance, save the glycogen for the truly intense segments of a session, and burn more body fat.6 If you can handle exercising without having to carb-load, you’re probably fat-adapted. If you can workout effectively in a fasted state, you’re definitely fat-adapted.

You Can Still Burn Glucose When Fat Adapted

It’s not that the fat-burning beast can’t burn glucose – because glucose is toxic in the blood, we’ll always preferentially burn it, store it, or otherwise “handle” it – it’s that we do not depend on it. I’d even suggest that true fat-adaptation will allow someone to eat a higher carb meal or day without derailing the train. Once the fat-burning machinery has been established and programmed, you should be able to effortlessly switch between fuel sources as needed.

A fat-burning beast will be able to burn glucose when necessary or available, whereas the opposite cannot be said for a sugar-burner. Ultimately, fat-adaption means metabolic flexibility. It means that a fat-burning beast will be able to handle some carbs along with some fat. When you’re fat adapted, you will be able to empty glycogen stores through intense exercise, refill those stores, burn whatever dietary fat isn’t stored, and then easily access and oxidize the fat that is stored when it’s needed.

If you want to feel these benefits and more, sign up for Keto Month and get

Access to an exclusive webinar about metabolism and you immune system featuring myself and Elle Russ

A 30 day meal plan and exercise regimen

30 days of valuable email tips, guidance, and encouragement

Access to the Keto Reset Facebook Group for additional support from others on the journey with you

How Do You Know if You’re Fat Adapted or Keto Adapted?

There’s really no “fat-adaptation home test kit.” I suppose you could test your respiratory quotient, which is the ratio of carbon dioxide you produce to oxygen you consume. An RQ of 1+ indicates full glucose-burning; an RQ of 0.7 indicates full fat-burning. Somewhere around 0.8 would probably mean you’re fairly well fat-adapted, while something closer to 1 probably means you’re closer to a sugar-burner. The obese have higher RQs. Diabetics have higher RQs.7 Nighttime eaters have higher RQs (and lower lipid oxidation).8 What do these groups all have in common? Lower satiety, insistent hunger, impaired beta-oxidation of fat, increased carb cravings and intake – all hallmarks of the sugar-burner.

It’d be great if you could monitor the efficiency of your mitochondria, including the waste products produced by their ATP manufacturing, perhaps with a really, really powerful microscope, but you’d have to know what you were looking for.

No, there’s no test to take, no simple thing to measure, no one number to track, no lab to order from your doctor. To find out if you’re fat-adapted, the most effective way is to ask yourself a few basic questions:

Can you go three hours without eating? Is skipping a meal an exercise in futility and misery?

Do you enjoy steady, even energy throughout the day? Are midday naps pleasurable indulgences, rather than necessary staples?

Can you exercise without carb-loading?

Have the headaches and brain fuzziness passed?

Yes? Then you’re probably fat-adapted. Welcome to the human metabolism you were wired for!

That’s it for today, folks. Send along any questions or comments that you have. I’d love to hear from you guys.

References http://ajpendo.physiology.org/content/259/5/E650.abstracthttp://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1970.tb04764.x/abstract?systemMessage=Due+to+scheduled+maintenance+access+to+the+Wiley+Online+Library+may+be+disrupted+as+follows%3A+Monday%2C+6+September+-+New+York+0400+EDT+to+0500+EDT%3B+London+0900+BST+to+1000+BST%3B+Singapore+1600+to+1700http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20427477http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19407076http://www.ajcn.org/content/77/2/313.shorthttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18801964http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9895421http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20864947

The post What Does It Mean to Be Fat Adapted or Keto Adapted? appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 6, 2020

Grain-free Fish and Chips Recipe

Fancy fish dishes have their place, but we’d rather roll up our sleeves and dive into a salty, crunchy, no-fuss Fish and Chips platter any day. It’s the perfect rainy-day comfort food. Crispy pan-fried coating wrapped around tender white fish – it’s the perfect combination for dipping.

Fancy fish dishes have their place, but we’d rather roll up our sleeves and dive into a salty, crunchy, no-fuss Fish and Chips platter any day. It’s the perfect rainy-day comfort food. Crispy pan-fried coating wrapped around tender white fish – it’s the perfect combination for dipping.

When you first go Primal, Keto, paleo, or other version of grain-free, it’s easy to assume fried food is off the table. We think that you can eat virtually anything you want, as long as you find the right way to make it with ingredients that won’t slow you down. Here’s a Primal spin on Fish and Chips with all the flavor and none of the fried food hangover.

Grain-free Fish and Chips Recipe

Serves: 4-5

Time in the kitchen: 50 minutes, including 25-35 minutes bake time

Ingredients

1 lb. cod, cut into 5 pieces

2 eggs

1/2 cup + 2 tbsp tapioca starch

2 Tbsp fine almond flour

½ tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp lemon juice

1/4 tsp salt

1/4 tsp black pepper

1/4 cup Primal Kitchen® Avocado Oil, divided

1/4 cup salted butter

1.5 lbs russet potatoes

Salt and pepper

Primal Kitchen Tartar Sauce, Cocktail Sauce, or our favorite Spicy Ketchup for dipping

Directions

Preheat your oven to 400 degrees Fahrenheit. Cut the potatoes into fries and spread them out on a large parchment covered sheet pan for 10 minutes. Toss the potatoes in 2 tablespoons of Primal Kitchen Avocado Oil, salt and pepper and lay them spread out in a single layer so they aren’t overlapping or touching one another. Roast for 10-15 minutes, then flip them over. Continue roasting for about 10 minutes or until they are golden on the outside and soft on the inside.

While the potatoes are roasting, prepare the fish. Combine the tapioca starch, almond flour, baking soda, salt and pepper in a large bowl. Whisk in the eggs and lemon juice.

Heat the butter and remaining avocado oil in a pan over medium-high heat. While the butter and oil are heating, dredge the fish portions in the batter. When the fat in the pan begins to bubble, dredge and add the fish portions to the pan one at a time. Wait 10 seconds or so after adding each portion to the pan.

Try to have the butter and oil mixture heating in the pan while you are dredging the fish portions in the batter, that way you can quickly move the fish from the batter to the hot pan to get that nice crispy and light fried coating.

The temperature of the pan and oil will decrease as you add each piece of fish to the pan, so wait 10 seconds or so before adding each additional portion so the oil stays hot enough. Cook the fish portions for about 3 minutes on each side. Check the internal temperature of the thickest portion of fish with a meat thermometer. You are aiming for an internal temperature of 145 degrees. If your fish is not up to temperature yet, you can continue to cook the fish for 1-2 minutes on either side, carefully flipping the fish in between. You can also transfer the pan to the oven to finish off the fish.

When the fish is cooked through, use a fish spatula to transfer the fish to a plate or sheet pan with a couple of pieces of paper towel over it to absorb any extra oil.

Serve the fish and chips hot with a few wedges of lemon, fresh parsley, and tartar sauce.

Nutrition Information (1/5 of recipe, without tartar sauce):

Calories: 475

Total Carbs: 35 grams

Net Carbs: 33 grams

Fat: 27 grams

Protein: 25 grams

The post Grain-free Fish and Chips Recipe appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 5, 2020

Weekly Link Love — Edition 84

Research of the Week

Split brain, no split consciousness.

High circulating ketone levels reduce cardiac inflammation and inhibit the progression of heart failure.

Psychological distress and loneliness are way up.

Analyzing the genetic imprints of the animal skins used for the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Why weed makes you go, “Whoa.”

New Primal Blueprint Podcasts

Episode 426: Mark Sisson: Host Elle Russ chats with yours truly.

Episode 427: Ron Sinha: Host Brad Kearns chats with Dr. Ron Sinha about the “Covesity Pandemic.”

Primal Health Coach Radio, Episode 63: Laura and Erin talk with Amy Berger about the primacy of context.

Media, Schmedia

Glad to have the Nutrition Coalition on the job.

It’s not so much the chlorinated chicken that disturbs me, but the reason why chlorinating chicken is necessary.

Interesting Blog Posts

Why does sleep deprivation kill? Might be the gut.

Social Notes

Everything Else

Should saturated fat intakes be reduced?

76 acre farms are about the ideal size by some measures. Agile and productive and resilient.

Things I’m Up to and Interested In

While we wait for a long term study on carnivore health: Somatic health in the Indigenous Sami population.

Interesting paper: The one exploring the interactions between vitamin D and the coronavirus.

Video I liked: 3D reconstruction of Australopithecus sediba walking.

Some of you will enjoy this: Beer probably good for cardiovascular health.

More “paradoxes”: Butter beats margarine, again.

Question I’m Asking

What has you excited?

Recipe Corner

Instant Pot honey mustard chicken and potatoes. Lose the potatoes if you want it low-carb.

Chicken pesto cast iron meatza.

Time Capsule

One year ago (May 31 – Jun 6)

10 Natural Anxiety Remedies – How to chill out.

Is Keto Cheating Unhealthy?– Well, is it?

Comment of the Week

“Can’t wait till I’m 130 years old. Max aerobic heart rate will roughly equal resting heart rate so I can finally burn maximum fat in my Barcalounger.”

– Great idea, Neanderchow.

The post Weekly Link Love — Edition 84 appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 4, 2020

7 Ways to Change Negative Self-Talk

Let me be the first to tell you that there’s nothing wrong with you. You may have some patterns to unlearn, some self-love to embrace, and some new behaviors to embody, but seriously, there’s nothing wrong with you. If you want to change your negative self-talk, you’ve got to first understand where it comes from.

Let me be the first to tell you that there’s nothing wrong with you. You may have some patterns to unlearn, some self-love to embrace, and some new behaviors to embody, but seriously, there’s nothing wrong with you. If you want to change your negative self-talk, you’ve got to first understand where it comes from.

There’s a famous quote by Mahatma Gandhi, that, in a nutshell says, “Your beliefs become your thoughts. Your thoughts become your words. And your words become your actions.”

So if your actions include binging on sourdough (again), rolling your eyes at your rolls and wrinkles, or subconsciously sabotaging your sleep cycle, you can go ahead and thank your belief system for that. You can also take comfort in knowing you’re not alone.

On any given week I’ll hear my clients say that making a protein rich breakfast takes too much effort. Or that they’re too busy to work out. Or they can’t stop eating desserts. These are all beliefs. And, as we’ll be breaking down here in a second, there’s a big difference between beliefs and truths.

Your Brain’s Role in Self-talk

Here’s the deal. Your brain’s job is to keep you safe.1 Because of this, it will always choose what’s familiar and comfortable over working toward a change that’s different. Even if that change is in the best interest of your health and happiness.

What’s familiar is safe and what’s unknown has the potential to hurt you. At least from your brain’s point of view. And so, it automatically creates negative thoughts (and negative self-talk) to keep you nicely tucked into your comfort zone.

Examples of Negative Self-talk

Here’s a scenario to illustrate what I mean. Say you’re thinking about ordering take out. Will it be a large, extra pepperoni pizza or a thick steak and roasted veggies? Depending on your past experiences and your personal belief system, your brain will automatically assign a meaning to that choice.

If you choose the pizza, your self-talk might be, “well, I guess I’ll be heavy my whole life” or “I never make good choices” or “life’s too short not to eat pizza!!” Unfortunately, that reaffirms your negative beliefs, which you’ll continue to repeat unless you do something to change them.

Other examples of negative self-talk might be:

I’m always out of shape

I’m too lazy

Why bother I never have enough time

Nothing ever goes right for me

That’s impossible

When will I learn

It’s my fault

I always mess things up

Overcoming Negative Self-talk

Reframing is a psychological technique used in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Also known as cognitive restructuring, 2 it allows you to reprogram your brain, changing your pattern of negative thinking — and the way you feel about certain situations, people, places, and things (including yourself).

This is important because, as noted above, your thoughts end up becoming your actions. And negative thoughts very often turn into self-destructive actions. “I’ll never be able to stick to the Primal Blueprint” quickly spirals into you speeding through a Krispy Kreme drive-thru for a dozen maple bars. Negative self-talk can cause a lot of damage. Not just to your waistline or your pancreas either. Having a critical inner dialogue has been linked to an increased risk of mental health issues, including depression.

The thing is, we’re so quick to criticize ourselves and classify our attempts as failures. But what they should really be, are learnings. Take for example, toddlers figuring out how to walk. If they bad mouthed themselves or gave up every time they fell down, we’d have a bunch of grownups crawling around on all fours.

Since they don’t have the stories we do — yet — they don’t thrash themselves with self-talk like “I always fall down” or “what the heck is wrong with me?” They just do it. And then they do it again, learning from their mistakes and building their confidence along the way.

Positive Self-talk Leads to Success

While negative self-talk clearly has its consequences, research shows that positive self-talk is actually the best predictor of how successful you’ll be. In One study, athletes were placed into four groups and asked to use four different methods of self-talk, including instructional, motivational, positive, and negative. Researchers found that the group that practiced positive self-talk performed the best.3 What they learned is that the athletes didn’t need to be reminded of what to do to play better or even psych themselves up to do it. They were the most successful when they told themselves what a great job they were doing.

The language you use creates your reality. So, when you say you hate exercising, do you really hate it, or do you just dislike the workouts you’ve done in the past? If you say healthy food is disgusting, is it really gross or not as delicious as a cheeseburger and fries? If you indulged too much over the weekend are you a failure or are you learning what you need to do differently next time? See where I’m going with this?

It’s all in the way you talk to yourself.

But you don’t have to do a complete 180 right out of the gates. Turning “I want to eat healthier, but I don’t know where to start” into “I want to eat healthier and I don’t know where to start” is a great first step. Changing the but to and allows you to acknowledge your experience and create room for opportunity.

How to Turn Negative Self-talk Into Positive Self-talk

Our brains are often hardwired to see the negative side4 of things, but choosing whether or not to believe those thoughts is always up to you. It’s entirely under your control to reframe those negative, nagging thoughts into empowering ones. Here’s a snapshot of how to do it, followed by a deeper dive down below.

Catch yourself in the act

Name your inner critic

Challenge your inner critic

Go from negative to neutral

Think like a friend

Be willing to be imperfect

Break out a gratitude journal

Ready? Here we go:

1. Catch yourself in the act. There’s a good chance you’re not even aware that you’re using negative self-talk, because you’re so used to doing it — it just feels normal! Building an awareness of your self-talk and acknowledging the fact that you’re sending yourself a negative message is the first step toward changing it. Track your negative thoughts for a week, writing down every time you say something mean to yourself.

2. Name your inner critic. This is designed to help separate yourself from your negative thoughts. And if you’re up for it, give it a silly voice too and say the mean thought out loud. Doing this interrupts the pattern, takes away your inner critic’s power, and creates space between you and the self-sabotaging message. When you give your inner critic a name, choose something lighthearted that reminds you not to take it seriously.

3. Challenge your inner critic. Look for evidence that this mean thought isn’t true. Do you always stress eat? Or feel defeated? Or skip workouts? The answer is probably no. I’m sure there’s been at least one time in your life that you made a choice that benefited your health. Think of the positive experiences you’ve had instead of dwelling on the not-so-positive ones.

4. Go from negative to neutral. As far as positivity goes, it doesn’t have to be all rainbows and puppies right away. However, starting to move from negative thoughts to neutral ones is a good start. Instead of “it’s disgusting how out of shape I am,” you could say “I get tired easily during my workouts right now.” It’s just a neutral awareness. No negativity. No mean inner critic.

5. Think like a friend. You’d never talk to a friend or family member the way you talk to yourself. Well, at least I hope you wouldn’t. Imagine someone close to you is in the situation that you’re currently in. What kind of words or emotions would you use to console them? Or motivate them? When you take yourself out of the situation, it’s easier to see things from a positive viewpoint.

6. Be willing to be imperfect. As a recovering perfectionist, I can tell you first-hand that this is key to changing your self-talk. We’re humans — and while we are miraculous creatures, we’re far from perfect. Having the ability to accept your imperfections allows you to look for what you can learn from your efforts. Plus, it helps you stay on track with your goals because you’re not fussing over whether or not every little detail is on point.

7. Break out a gratitude journal. Research that having a gratitude practice can help you see things from a glass-half-full perspective rather than half empty.5 I started incorporating a gratitude practice into my morning routine a few months ago and it’s a game changer. To help redirect your negative patterns and begin seeing things with a positive outlook, try writing down three to five things that you’re grateful for every day.

I don’t care how much proof you have that you always get it wrong, or that you couldn’t lose fat if your life depended on it. You’re a work in progress. It takes time and regular practice to unlearn years or maybe even decades of negative self-talk and start seeing (and believing) things from a positive point of view.

References https://mi-psych.com.au/what-your-brain-doesnt-know/https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/in-practice/201301/cognitive-restructuringhttps://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsep/33/5/article-p666.xmlhttps://www.verywellmind.com/negative-bias-4589618http://local.psy.miami.edu/faculty/mm... shows

The post 7 Ways to Change Negative Self-Talk appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 3, 2020

Dear Mark: Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) Training

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m going to be answering questions about Maximum Aerobic Function, or MAF. If this is your first time hearing the term, MAF refers to a method of endurance training that maximizes the function of your fat-burning aerobic system. I’ve come down hard on conventional or popular modes of endurance training in the past for being too stressful and reliant on sugar. MAF training is the opposite: low stress and reliance on body fat.

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m going to be answering questions about Maximum Aerobic Function, or MAF. If this is your first time hearing the term, MAF refers to a method of endurance training that maximizes the function of your fat-burning aerobic system. I’ve come down hard on conventional or popular modes of endurance training in the past for being too stressful and reliant on sugar. MAF training is the opposite: low stress and reliance on body fat.

Let’s dive right in to the questions:

What is MAF training?

MAF trains your aerobic fat-burning system to be more efficient and produce greater output at the same “intensity.” It means slowing the hell down to go faster. It means the slower you go, the more fat you’re burning and the better your mitochondria are getting at utilizing fat for energy. It means training up to but not over your maximum aerobic heart rate.

MAF was coined by Phil Maffetone, who came up with an ingenious way to calculate your max aerobic heart rate: subtracting your age from 180. 180 minus your age gives you the heart rate at which you’re burning the maximum amount of fat and minimum amount of sugar.

Say you’re 30 years old. 180 minus 30 is 150. To burn the most fat possible, you maintain a heart rate equal to or lower than 150 BPM. Now, and here’s the trick: It doesn’t sound like much. It doesn’t feel like much. It probably feels way too easy. But bear with me. It works. This is where the magic happens, where you accumulate easy volume, where the “base” is built, where you begin building more fat-burning mitochondria.

The hard truth is that if jogging spikes your heart rate past your aerobic max, you’re not very good at burning fat during exercise. Even if you don’t “mind” pushing that heart rate up. Even if you “feel fine” jogging at 153 bpm. 180 minus age is where you have to be to improve fat burning. That might look like jogging, or walking, or walking uphill, or running pretty briskly, depending on where you’re starting. It’s all relative to your aerobic fitness.

It takes patience to stay at the aerobic zone, but over time, if you’re consistent, you’ll notice that you can handle a higher and higher workload at that same “easy” MAF heart rate. You’ll be going faster while still burning mostly fat—and it’ll still feel easy.

What are the benefits of cardio using MAF training?

In some parts, I’m known as the anti-cardio guy. I coined the phrase “chronic cardio,” and the entire reason I got into this Primal business is that decades of elite endurance training—marathons and triathlons—wrecked my body and drove me to develop and pursue a different, more sustainable path to health and fitness.

But I’m not anti-cardio. In fact, moving frequently at a slow pace in all its incarnations forms the foundation of my Primal Blueprint Fitness philosophy. And MAF is just about the best way to do it.

When you build your aerobic base, you don’t just get better at running (or cycling, or rowing, or swimming, or whatever it is that you’re doing). There are more benefits that aren’t as overtly noticeable:

You get better at utilizing the fat you eat and the fat you store, paying huge dividends in other areas of your life.

You get steadier energy levels throughout the day. There’s always that big bolus of energy hanging around, ready to be consumed and converted into ATP. And you’re very good at burning it.

You have a lower propensity to snack. It’s easier to stick to a healthy way of eating and refrain from snacking when you can cruise along eating your own adipose tissue in between meals.

You have more mitochondria, and the mitochondria you have are better at burning fat.1 This is what everything comes down to. Mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent energy overload lie at the root of many degenerative diseases. The better your mitochondria work, the more energy you can handle, and the less likely you are to suffer the negative ramifications of chronic energy overload.

This seems to confer benefits to longevity. Although we can’t establish causation, moderate exercise—jogging up to 20 miles a week at an 11 minute mile pace—offered the most protection against early mortality in one study. Running more than 20 miles a week, or running at a 7 minute mile pace, offered fewer mortality benefits.2

Plus, having that large aerobic base helps with any physical pursuit, and not just endurance sports. A large aerobic base helps in CrossFit. A large aerobic base helps in football or martial arts or rock climbing. Whenever you can burn more fat, save more glycogen, and still get the same amount of performance, you’re winning.

When you’re aiming for MAF, how much cardio is too much?

As long as you stay in the MAF zone, it’s very hard to overdo cardio. You’re deriving your energy primarily (90/95%) from fat, a virtually inexhaustible energy source, and very little from carbohydrate. You have thousands of calories at your disposal. Your relative intensity is lower than the person who’s out there burning sugar, so your joints aren’t falling apart and your muscles aren’t getting as fatigued. You’re accumulating less stress overall.

When you start hitting intensities that elevate your heart rate beyond the 180 minus age MAF zone, your tally begins. The stress and joint damage begins to accumulate. You become more reliant on sugar compared to fat. You can still train like this, but your margin for error is a lot smaller.

If I had to put a number to it, I’d say that you shouldn’t burn more than 4000 calories a week from cardio.

How should you eat while doing maximum aerobic function?

MAF is most effective when paired with carbohydrate restriction. It doesn’t have to be keto reset levels, although that’s a great option. Standard Primal low-carb, staying under 150 grams per day, is good enough.

When you combine MAF training with carb restriction, everything is enhanced. You build more mitochondria after a single carb-restricted MAF training session than after the same session without the carb restriction. 3

Going low-carb while MAF training also continues the work when you’re at rest. If you burn primarily fat when endurance training but go home to a high-carb diet, you’re squandering a lot of progress.

What if I’m too slow?

One of the most common questions I receive comes from people worried they’re too slow. “I feel like I am going too slow. I can run a 7:00 minute mile no problem at race pace and a higher heart rate, but if I stay at 180 minus age, I can’t get my speed past 10 minute miles.”

You can keep doing the higher HR runs, but you’re not building a base and you may be setting yourself up for damage down the line. That means you are good at burning glucose/glycogen and have a good tolerance for discomfort, but it also means that in this current configuration, you suck at burning fat. The whole point of MAF training is to train at the highest heart rate you can handle (and highest speed) while still getting 90-95% of your energy from fat. Over time, you’ll find that as you get better fat adapted, your mile pace will come down at that same MAF heart rate. That’s the indicator that you are becoming more efficient with your burning of fat over glucose.

Track things over months, not workouts. It may take a long time to improve, but improve you will. Pro tip: if you are a well-trained runner or cyclist, you could probably add 5 to that 180-age number and be OK.

Isn’t my MAF pace way too easy?

It seems way too easy, and that’s the whole point. It’s also where people get tripped up.

You think you can handle a bit more, so you push the HR up. I mean, running at an easy pace couldn’t possibly make you faster.

Over time, you’ll find that as you get better fat adapted, your mile pace will come down at that same MAF heart rate. That’s the indicator that you are becoming more efficient with your burning of fat over glucose.

Just be sure you are always able to carry on a conversation and not get winded as the “guard-rail.”

Folks, that’s MAF training. If you want more details and a specific plan of attack, check out my book Primal Endurance.

If you have any more questions, ask down below! Thanks for reading, everyone.

References https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1540458/http://health.heraldtribune.com/2012/06/06/moderate-exercise-may-be-better-for-you-than-vigorous-workouts/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3823511/

The post Dear Mark: Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) Training appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

June 2, 2020

Definitive Guide to Carb Timing and Carb Cycling

The Primal Blueprint is generally considered a low-carb way of eating, especially in contrast to the Standard American Diet and the like. We’re not anti-carb. My Big-Ass Salad is a huge bowl of carbs from vegetables, after all. We’re selective about the sources of our carbs and generally mindful about how many we take in.

The Primal Blueprint is generally considered a low-carb way of eating, especially in contrast to the Standard American Diet and the like. We’re not anti-carb. My Big-Ass Salad is a huge bowl of carbs from vegetables, after all. We’re selective about the sources of our carbs and generally mindful about how many we take in.

Given that, readers always want to know the “right” way to incorporate carbs. Which carb sources? How many? When? How often?

The Primal Blueprint Food Pyramid and Carb Curve provide answers to the first two questions. The latter two… well, those are more complicated.

I’ve written about these topics many times, but the questions keep on coming. Today I’m going to try to condense the main points into one post. I’ll touch on some issues you’ve raised in the comments of recent posts, too.

In truth, I keep getting questions because there are so few definitive answers about the optimal way to incorporate carbs in your diet. Underlying hormonal and metabolic health, activity level, and lifestyle variables to make it impossible to make across-the-board recommendations. Few studies address these issues, and those that do always use standard high-carb diets in their manipulations.

The best I can do is explain the logic behind different strategies and encourage you to experiment. As with so many things, it might take time to discover which strategies work best for you.