Mark Sisson's Blog, page 327

September 11, 2013

How-To: Standup and Mobile Workstations

A few years back, my general manager and editor hurt his back deadlifting. He found the only way he could comfortably work at a desk was to stand. It worked really well for him, even offering benefits above and beyond the improvements in lower back pain – stuff like improved energy levels and increased focus and cognition. Once his back recovered, he continued to stand because of these benefits. It eventually spread to the rest of us at Mark’s Daily Apple and Primal Blueprint, prompting me to devote an entire post to standup workstations.

The first standup desk at our headquarters was cobbled together using a stack of shipping boxes laid flat, but, as the video shows, we’ve improved on it. And, as more of our workers have taken up the practice, we’ve realized that while standing in one place all day may be better than sitting in one place all day, it’s not ideal. Man was neither meant to stand nor sit in place. You stand long enough and you start resting on the desk, leaning forward or to either side and picking up some other bad habits. Some research even indicates that standing at a desk all day comes with certain risks of its own, including increased risk of varicose veins and carotid artery damage. Now, we think in terms of the mobile workstation, and emphasize changing things up throughout the day (i.e. sitting, standing, and walking).

In that vein, we’ve brought in treadmill desks. My favorite is the TreadDesk, a standalone treadmill that fits underneath most desks. It’s just the tread; no podium, no handles, no bulky set-up. Super simple. You walk while you work at the computer. Some folks do around 1.5 miles per hour, others can handle a little over 2 mph, but the most comfortable range seems to lie between 1.5 and 1.8 mph. Every worker gets a TreadDesk if they want one and if it makes sense for their job.

The real beauty of the treadmill desk is that you never feel that incessant need to workout tugging at the back of your mind. Since you’ve already done 5, 6, 7 miles at work, you don’t necessarily have to find time to trudge off to the gym. You can relax, unwind, and spend time with friends and family after work. It doesn’t replace exercise, but it certainly takes the edge off it.

If a TreadDesk doesn’t work or make sense for someone, I encourage frequent movement: walking, squatting, pushups, pullups (there’s even a bar in the office), a light jaunt outside in the Malibu sun. The key is to break up the stasis. Even just five minutes every two hours is plenty.

Since our shipping department processes hundreds of orders a day, we’ve made a simple but revolutionary change to the setup there: we bumped the tables up eight inches. This allowed the guys to do all their packing, taping, and shipping standing up straight, with open hips, rather than bending over hundreds of times a day to reach the materials. 45 degrees of hip flexion doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up (and eventually turns into dangerous lumbar flexion!) and wears the body down.

At home, which is where I do most of my work these days, I don’t find I really need the TreadDesk, since I’m the boss and I can take as many breaks as I need. Instead, I have a Locus Workstation from Focal. This is a great standup desk with a “human kickstand” to lean against when you get sick of standing, promoting excellent posture and proper ergonomic angles.

I reached out to Focal to see if I could score some kind of special deal for Mark’s Daily Apple readers. They provided me a coupon code that gets you a free anti-fatigue mat ($75 value) with purchase. Just add the mat to the cart and use the code “Upright!” during checkout. (They also informed me about their affiliate program, so full disclosure, the Focal link above is an affiliate link. If you happen to purchase something from them after clicking on the link, I’ll earn a small commission. Proceeds go towards maintaining Mark’s Daily Apple.)

The mobile workstation is a no-brainer for me – and for anyone, really. Not only does it promote better health in my employees, it makes work more enjoyable and workers more productive. And though the gadgets and the treadmills and the fancy desks might make staying mobile easier, they certainly aren’t required. Anyone can get up and go for a short walk, right?

Standup and Mobile Workstation Tips

1. Start with short bouts of standup time – use boxes to elevate computer

2. Take 5-minute walking/exercise breaks every two hours

3. Practice good posture – elongated spine and proper ergonomic angles

Do you have a standup workstation? How have you found it? Do you stand all day, or mix things up? Let everyone know in the comment board!

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 10, 2013

Unveiling The Paleo Manifesto: An Exclusive Excerpt

I’m happy to have my friend, John Durant, share an exclusive excerpt from his new book,

The Paleo Manifesto

. Many of you remember John from his

feature in the New York Times

and hilarious

interview on The Colbert Report

, which raised the profile of primal living.

I’m happy to have my friend, John Durant, share an exclusive excerpt from his new book,

The Paleo Manifesto

. Many of you remember John from his

feature in the New York Times

and hilarious

interview on The Colbert Report

, which raised the profile of primal living.

Well, John’s book is finally done – and trust me, it’s worth the wait. Just don’t expect any recipes or meal plans (he’s a crummy cook). John begins by going behind the scenes at one of the world’s top zoos to learn how they keep animals healthy in captivity – hint: mimic their natural habitat – which kicks off a series of adventures exploring everything from the Bible’s obsession with hygiene to the British reputation for lousy teeth. John distills the lessons from his adventures and applies them to modern life – food, fasting, movement, bipedalism (standing, walking running), thermoregulation, sun, sleep, ethics, and the environment – showing how to craft a holistic primal lifestyle in the modern world. Entertaining and beautifully-written, The Paleo Manifesto is an accessible and credible defense of primal living that even skeptics will enjoy.

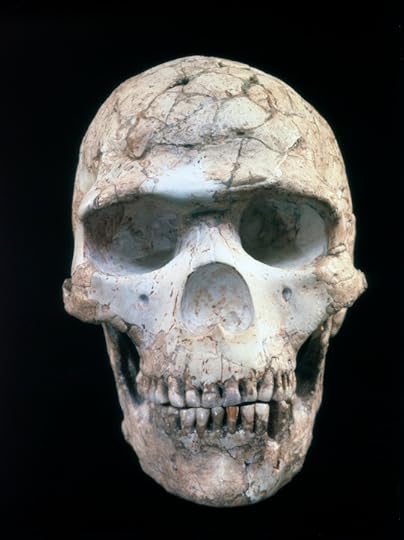

In this excerpt, John receives a private tour of Harvard’s fossil archive, holds the 80,000 year-old skull of a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer, and unravels the mystery of his amazing grin.

Enter John…

Five years after graduating, I found myself back on the Harvard campus in a familiar situation: late to meet with a professor. My destination? Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

The Peabody boasts a collection of over six million ancient artifacts from around the world: a shark tooth spearhead from the South Pacific; Mayan hieroglyphics engraved on giant limestone slabs; a Native American whistle carved out of eagle bone collected by Lewis and Clark on their legendary transcontinental expedition.

The Peabody is also where Harvard stores its osteological collections: bones. Lots of bones. Neanderthals from Europe, mummified remains from South America, chimpanzees from Africa. The collections contain fossils famous for documenting the emergence of human beings, as well as skulls with uncommon deformities used to teach students about skeletal development. Delicate and rare, the bones in the collections are locked away in an archive, not on display to the public.

I was meeting with Dr. Daniel Lieberman, chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology. Bearded and bespectacled, he looked just like a professor should; he was the ur-professor. Dr. Lieberman studies bones, both dead bones (paleoanthropology) and living bones (biomechanics). He earned tenure by studying the human head, but he earns mention in ESPN stories for his research on barefoot running.

My visit today was all about the human head – skulls, actually – and the impact of the Agricultural Revolution on human health. Our diverse, omnivorous diet as hunter-gatherers became heavily grain-based, contributing to an overall decline in health—and I was about to hold the evidence in my own hands.

“Okay, let’s go see some skulls,” said Dr. Lieberman, as he led me into the museum.

We walked up to an old wooden door. Probably part of the original construction in the late nineteenth century, it had been retrofitted with an electronic security system. Dr. Lieberman swiped a key fob past it, the lock clicked open, and we walked into a brightly lit room with laboratory equipment lining one wall. It felt like moving from historic to modern, but we were actually moving from historic to prehistoric.

The archive felt like a cross between a library and a morgue. It was lined with shelves, which were filled with boxes of bones. Handwritten words faced outward: “Natufian—El Wad”; “Chimpanzee—Liberia.” The labels served the dual role of title and tombstone.

Dr. Lieberman handed me a pair of latex gloves.

“Here, put these on.”

The gloves weren’t there simply to protect the ancient remains from me; they were also there to protect me from the ancient remains, since many had been preserved in nasty chemicals.

Dr. Lieberman pulled a box off the shelf, carried it over to a table, and took off the lid. He gently lifted up a skull.

“This is Skhul V. This guy is famous. He was a hunter-gatherer living more than 80,000 years ago in the Levant. That’s modern-day Israel. He’s one of the earliest anatomically modern Homo sapiens ever recovered. Here, you can hold his skull. There’s only one rule.”

Dr. Lieberman paused and looked directly at me.

“Use two hands.”

It was a command, not a suggestion. This is not something you want to drop.

With that he gingerly passed me Skhul V.

Looking at a human skull creates an optical illusion: it looks like the skull is smiling. The brain interprets the visible teeth and upswept jawbone as an upturned mouth. Not only did this phenomenon create the creepy effect that Skhul V was somehow alive, but he seemed downright cocky, brimming with a confidence that even the grave couldn’t shake.

And what a grin this guy had. What an amazing grin.

“Notice anything?” Dr. Lieberman asked. “Look at the teeth. They’re straight. And no cavities. His wisdom teeth came in just fine. Humans, like all animals, have evolved teeth that are well suited to their natural diet. An infected tooth can easily kill you, and there were no dentists in the Paleolithic.”

Nearly one hundred thousand years before dentists and orthodontists, this hunter-gatherer had a strong, straight set of chompers. Skhul V challenged much of what I’d been taught about the history of human health.

“Now, look,” Dr. Lieberman continued, “hunter-gatherers didn’t have perfect teeth. This guy has well-worn teeth, and he’s actually missing one due to an abscess. So don’t stop going to the dentist. But wait until I show you the skulls of early farmers—a lot of them would need to get fitted for dentures.”

“So what’s the secret? Eat less sugar?” I asked.

“Well, yes, but healthy teeth depend on a variety of factors,” Dr. Lieberman explained. “First, yes, it matters what you eat. Amylase in your saliva breaks down carbohydrate into sugar in your mouth. Bacteria feed on the sugar and produce acid that wears away the enamel on teeth, giving you cavities. We’ll see what happened to the early farmers who started eating a starchier diet.”

To figure out what humans used to eat, teeth are a good place to start. Not only do teeth fossilize well, but they’re the first point of contact between the food we eat and our body, the first part of our internal digestive tract. And if our teeth aren’t well adapted to a particular food, it’s unlikely the rest of our digestive tract is. But whatever Skhul V was eating, his teeth seemed to be up to the challenge.

“It also matters how tough your food is to chew,” Dr. Lieberman continued. “When you put force on bones, they grow bigger and stronger. People back then ate tougher foods, they put larger forces on their jaw, and thus they had jaws large enough to actually fit all of our teeth. And those bite forces may have helped our teeth come in straight.”

“And since we all eat such soft foods these days?” I asked.

“Smaller jaws.”

It felt oddly insulting to hear him say that. In a sense he was pointing out that my growth had been stunted in childhood. I’m deformed. And not just me, but most modern people.

Dr. Lieberman took the skull and put it back in the box, then pulled out a femur and held it up.

“I don’t know if you’ve seen many femurs, but I have, and this is quite a femur. He almost certainly has much thicker bones than either of us. Bone cross-sectional thickness increases with use, particularly before the mid-twenties. It suggests significant musculature.”

“He was tall, too,” Dr. Lieberman said as he held the femur up to my thigh. I’m five foot ten, and the femur was longer than mine. (Dr. Lieberman later sent me a published estimate on Skhul V: five foot ten and 150 pounds. “Yeah, I don’t believe it,” he said. “I suspect they estimated them wrong.”) Even so, five foot ten would have been considered gigantic from the Agricultural Revolution until recently. Early farming populations lost as much as five inches of height compared with early foragers.

“So how long did this guy live?” I asked.

“Well, this guy probably fits the stereotype of dying young,” Dr. Lieberman said. “Maybe thirty to forty years old. But life was dangerous back then, and it looks like he was healthy right up to the end. Plenty of ancient hunter-gatherers lived a long time. Contemporary hunter-gatherers regularly live well into their sixties and seventies.”

The common misperception is that ancient people would blow out the candles at their thirty-fifth birthday party and then just drop dead. But even chimpanzees and gorillas can live that long in the wild, and there are good reasons to believe we are naturally longer lived than they are. Humans have fewer natural predators than do other primates, as well as a longer childhood before puberty. The age of the oldest documented human (122 years old) far exceeds the oldest documented chimpanzee (66 years old) and gorilla (56 years old), both of which lived in captivity with no risk of predation or starvation. The natural human life span appears to have lengthened in the late Paleolithic when humans were able to fend off external sources of mortality and bear (or support) offspring at older ages. In fact, it’s likely that life expectancy initially dropped after the Agricultural Revolution.

The Agricultural Revolution seems like a paradox of history: if human health got worse, then why did people become farmers?

The shift to an agricultural lifestyle wasn’t something that anyone consciously planned. Even so, the domestication of animals and plants appears to have taken place independently in multiple locations around the world (the Fertile Crescent, China, India, the Americas, and Africa) at about the same time, 15,000 b.c. to 5,000 b.c. It was a technology whose time had come.

In short, the Agricultural Revolution unlocked a path to more rapid growth—in population, culture, and technology—and the people who took that path left descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky. A fifty-person band of hunter-gatherers—even if they are relatively tall and healthy—will be displaced by a wealthy, technologically advanced city-state with a fast-breeding population, many of whom could be enlisted as soldiers, even if they are short and sickly.

“Shall we go look at some diseased farmers?” asked Dr. Lieberman, and he led me to another part of the archive. He pulled out a couple more boxes of bones and placed them on the counter. He lifted up another skull, holding it for me to have a look. “This is an early Neolithic farmer from Tangier, in modern-day Morocco.”

Dr. Lieberman turned it over to show the dental cavity.

“These are some shitty teeth. Once you get farming, you get a lot more cavities. It’s classic.”

The teeth were ground flat, filled with holes, and many were missing. It looked brutally painful.

“By the way, it’s not just starch that causes this. It’s also the little bits of stone that get mixed into food when grinding grains. That’s why the teeth are all ground flat. And see how shiny they are? They’ve been polished by the stone bits, like by sandpaper. A lot of starch, plus wear and tear, and a poor diet make for a lot of dental problems.”

Dr. Lieberman put the Moroccan farmer away and opened another box.

“We’ve got lots of diseased farmers. This guy is from the fifteenth century in modern-day Montenegro.”

He held up the skull. There were long gaps where teeth were missing. Based on the bones, he wasn’t much more than five feet tall.

“This is a squat little person who had a horrible, nasty life,” Dr. Lieberman observed. “I know you’re focused on diet, but probably the biggest negative impact on the overall health of early farmers came from infectious disease: a result of living in close proximity to other people and domesticated animals for the first time.”

What Dr. Lieberman said confirmed my basic take on the story of human health. It wasn’t one uninterrupted improvement. Things got worse before they got better. Teeth got worse, stature declined, infectious disease went through the roof, and life span declined for the average person.

“Just don’t forget that the Agricultural Revolution allowed more people to survive. All of us wouldn’t be here without it,” Dr. Lieberman said as he packed up the bones.

“Speaking of the Agricultural Revolution, who’s hungry for lunch?”

For the rest of the story, order The Paleo Manifesto .

John Durant

John Durant is author of The Paleo Manifesto: Ancient Wisdom for Lifelong Health and is a leader of the growing ancestral health movement. He has been featured in the New York Times and interviewed on The Colbert Report. Prior to founding Barefoot Runners NYC and Paleo NYC, the largest paleo/primal group in the world, Durant studied evolutionary psychology at Harvard. He keeps a freezer chest full of organ meats in the bedroom of his Manhattan apartment, and he is fully aware of how weird that is. He blogs at HunterGatherer.com.

John Durant is author of The Paleo Manifesto: Ancient Wisdom for Lifelong Health and is a leader of the growing ancestral health movement. He has been featured in the New York Times and interviewed on The Colbert Report. Prior to founding Barefoot Runners NYC and Paleo NYC, the largest paleo/primal group in the world, Durant studied evolutionary psychology at Harvard. He keeps a freezer chest full of organ meats in the bedroom of his Manhattan apartment, and he is fully aware of how weird that is. He blogs at HunterGatherer.com.

Author Photograph: Gabrielle Revere

Skull image courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 46-49-60/N7365.0, Digital File #60743070.

Excerpted and adapted from The Paleo Manifesto by John Durant. Copyright © 2013 by John Durant. Excerpted by permission of Crown Publishers, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

September 9, 2013

Dear Mark: What’s the Deal with Fiber?

Last week’s guest post from Konstantin Monastyrsky, author of Fiber Menace, generated a lively, boisterous, and at times combative comment section. I use these descriptors in the best sense possible, mind you; debate is healthy and necessary, even – nay, especially – if it’s impassioned. So right off the bat, I want to thank everyone who wrote in. I also want to thank Konstantin, whose views on fiber forced me to reconsider my own way back when I first encountered him over five years ago. Without his input last week, we wouldn’t be having this discussion, and many people would still be sitting on whatever side of the fiber fence they prefer, never even considering that another side exists. I know I might still be catching up if I’d never read his book all those years.

Last week’s guest post from Konstantin Monastyrsky, author of Fiber Menace, generated a lively, boisterous, and at times combative comment section. I use these descriptors in the best sense possible, mind you; debate is healthy and necessary, even – nay, especially – if it’s impassioned. So right off the bat, I want to thank everyone who wrote in. I also want to thank Konstantin, whose views on fiber forced me to reconsider my own way back when I first encountered him over five years ago. Without his input last week, we wouldn’t be having this discussion, and many people would still be sitting on whatever side of the fiber fence they prefer, never even considering that another side exists. I know I might still be catching up if I’d never read his book all those years.

Many of you asked whether I endorsed the views espoused in the guest post. You wondered whether I’d shifted my stance on the Big Ass Salad. You wanted my take on the whole fiber thing, basically. So without further ado, let’s discuss fiber.

It’s often said that fiber is indigestible, that it serves no nutritive purpose – and that’s partially true. Humans can’t digest fiber. Our digestive enzymes and endogenous pancreatic secretions simply have no effect on roughage. Our gut flora, though? Those trillions of “foreign” cells residing along our digestive tract that actually outnumber our native human cells? To those guys, certain types of fiber are food to be fermented, or digested. That we feed our gut flora these prebiotic fibers is important for three main reasons:

1. Because the health (and composition) of the gut flora helps determine the health of the human host (that’s us!). It’s difficult to name a physiological function or health parameter that is not impacted by the gut microbiome, including but not limited to digestive, cognitive, immune, emotional, psychological, metabolic, and liver health. Our microbiota depend on fermentable fibers for food. It’s not clear what exactly constitutes “healthy gut flora,” and we’re still teasing out exactly how it affects the various physiological functions, but we know we need them and we know they need to eat something to even have a chance at helping us.

2. Because the short chain fatty acids that are byproducts of fiber fermentation, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, improve our health in many ways. Butyrate in particular has been shown to have beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity, colonic transport, inflammation, and symptoms of Crohn’s disease. It’s also the preferred fuel source for our native colonic cells. Basically, without enough butyrate (and, by extension, fermentable prebiotic fiber to make it), our colons don’t work as well as they should. This can lead to digestive impairments and perhaps even cancer. Mucin-degrading bacteria predominate in colorectal cancer patients, for example, while butyrate-producing bacteria rule the roost in healthy patients without cancer. Populations with lower rates of colorectal cancer also tend to have higher levels of butyrate. Propionate is helpful, too, though not to the extent of butyrate.

3. Because by feeding and bolstering the populations of “good bacteria,” we reduce the amount of available real estate for “bad bacteria” to set up shop. Gut bacteria don’t just float around in there. They cling to surfaces, nooks, crannies, and crevasses. They’re impossibly small, but they do take up space. After antibiotic treatment where both good and bad gut flora are indiscriminately targeted and wiped out, pathogenic obesity-promoting bacteria take advantage of the open space. That’s a worst-case scenario, but it shows what can happen when the harmony of the gut is disturbed (whether by antibiotics or lack of fermentable fibers).

Overall, because the health of our gut community is inextricably tied to the health of our minds and bodies, I think attaining fermentable fiber through the fruits and vegetables we eat is incredibly important. Heck, even the only food that’s actually expressly “designed” to feed humans – breast milk - contains prebiotic compounds whose main purpose is to feed and cultivate healthy gut flora in infants, which suggests that the need for prebiotics is innate. Coprolite (read: ancient fossilized stool) studies certainly indicate that our ancestors may have consumed a significant amount of prebiotics, and we even have receptors and transporters built-in to handle and accept the butyrate produced from fermentable fiber. Or, if you want to say that humans haven’t evolved a dietary requirement for fiber, that’s fine. But we have evolved to rely on gut flora to help our bodies work best, and that gut flora has evolved to require a steady, varied source of fermentable, prebiotic fiber. That can’t be denied.

I have been suspicious of fiber in the past, though. Like Konstantin, I’ve discussed the folly of loading up on the kind of fiber whose only purpose is to rend the intestinal walls, doing enough damage to induce mucus secretion which acts as lubricant. I’m talking about insoluble fiber, of course.

Insoluble fiber is a bulking agent. You know how weight lifters swear by whole milk and beef for adding mass? Insoluble fiber is like that, only for poop. It makes for extremely impressive toilet bowl displays and potentially expensive plumber fees, I’ll admit. And some people “need” to feel like they’ve done something down there. They like to take a peek after a bowel movement and let the distinct sensation of accomplishment wash over them. But for digestive health? I’m unconvinced, and there’s not much evidence in favor of it. Optimally, stool is made up of mostly water and bacteria - not undigested food.

The health claims just don’t add up.

For one, insoluble fiber doesn’t ferment very well. That’s why neither we nor our gut microbes can digest, say, cellulose-rich grass – we don’t have the hardware, and neither do our gut flora. No fermentation, no short chain fatty acid production.

How about constipation? Bulking up your stool is supposed to improve symptoms of constipation, right? That’s why almost every doctor will tell you to “eat more fiber” upon hearing that you’re constipated. It’s gotta be evidence-based advice! Well, the actual evidence is rather weak. A recent meta-analysis concluded that while increasing dietary fiber does increase the frequency of bowel movements, it does nothing for stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use, and painful defecation. So it will make you poop more often, sure, but each bowel movement is going to hurt and you’re still going to need laxatives to do it. Another recent study found that stopping or reducing dietary fiber intake reduced constipation.

Or cancer? One recent study compared the fiber intakes and gut flora composition of advanced colorectal cancer patients to healthy controls. Healthy controls who ate high-fiber tended to have more butyrate-producing microbes than low-fiber healthy controls and high-fiber cancer patients, suggesting that it’s not “fiber” that protects against cancer but “fermentable fiber.” The cancer patients who ate high-fiber were likely eating insoluble, cereal-based fiber, which was not protective. This jibes with an older study’s results: while both fruit and vegetable fiber were associated with lower risks of cancer, cereal fiber – which is mostly insoluble - was associated with a slightly higher risk. Another study found similarly protective links between fruit and vegetable fiber and stomach cancer, but not grain fiber.

If you desperately need to execute a double decker at the home of a sworn enemy, load up on insoluble fiber beforehand. Otherwise, stick to what insoluble fiber you’ll get as a byproduct of eating real fruits and vegetables.

How many fruits and vegetables should I eat, you might be wondering? And does that mean soluble, fermentable fiber, and lots of it, is fair game?

It depends. I know that’s not a sexy, easy answer, but it’s the right one. Allow me to explain.

The Sub-Saharan farmer who’s spent his life handling and milking goats, picking up and distributing manure, working the fields, plunging his bare hands into fresh loamy soil to plant a seed or pull a weed, taking his meals with soil still underneath his fingernails, eating lots of fiber-rich vegetation (often without washing it), and encountering not a single dose of antibiotics is going to have a more robust, varied gut microbiome and greater capacity to handle fiber than the suburban pencil pusher (perhaps that term needs updating – let’s go with keyboard rattler or desk jockey) who’s spent his childhood mostly indoors wearing a perma-sheen of hand sanitizer and sunscreen while eating a diet of peanut butter and jelly on white bread, mac and cheese, hot dogs, and pizza, and his later years wracked by chronic low level stress that disrupts his gut flora and alters his digestion.

Should you fear fruits and vegetables because of the fiber? Has your modern upbringing ruined your digestive capability forever? No, I don’t think so. It may have temporarily impaired your ability to handle fermentable fibers – increasing numbers of people are reporting trouble with the class of fermentable carbohydrates known as FODMAPs (check the FODMAP list at this PDF) largely because they don’t have the right levels/populations of gut flora – but it isn’t permanent. You just need to be aware of the complex, delicate interplay between the food fiber we eat, the composition and health of our gut flora, and our digestion. You should pay attention to your own digestion and how fiber affects it. You should introduce foods rich in soluble, fermentable fiber gradually and even cautiously. Allow time for your gut flora to adjust to the new food source. Expect flatulence.

But you should definitely introduce them.

Eventually, you’ll be able to fish a sample out of the toilet, snap a shot of it with your iPhone camera, and have your entire gut microbiome analyzed on the spot, complete with dietary fiber recommendations for optimal butyrate production and minimal flatulence, but that’s a long while off. Scientists are still figuring out which gut flora are best, which species are good and which are bad, what kind of fiber source they like, and how often and how much we should feed them. In other words, we’ve reached the stage of knowing enough to know that we know very little. In the meantime, we know “gut flora are important.” We have vague ideas of which populations are “good” based on correlative studies that link certain species with diseases. We know we need gut flora because of their endless interactions with the host, and that they need food. We know that the plants (and breast milk) we eat provide that food.

And that’s about it.

It’s enough to get started, though. I’d say between 75 and 100 grams of carbs from mostly vegetables and some fruits, plus the occasional emphasis on plants particularly heavy on the prebiotic fiber - stuff like raw onion and garlic, leeks, jerusalem artichokes, dandelion greens, raw plantains and green bananas – should provide sufficient food for your gut. If you have too much, you’ll know it.

Oh, and the Big Ass Salad is definitely here to stay.

That’s what I’ve got, folks. What say you?

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 8, 2013

Weekend Link Love

I’ve just launched a new Facebook page for Primal Blueprint Publishing, where you can find photos, videos, book reviews, and recipes from your favorite Primal books. Stay tuned for constant updates to the page to keep you guys up to speed with the latest news from our Primal authors – what books we’re getting ready to release, when we’re releasing them, and fun, random info about our authors. Make sure to “Like” it, too! Thanks!

I’ve just launched a new Facebook page for Primal Blueprint Publishing, where you can find photos, videos, book reviews, and recipes from your favorite Primal books. Stay tuned for constant updates to the page to keep you guys up to speed with the latest news from our Primal authors – what books we’re getting ready to release, when we’re releasing them, and fun, random info about our authors. Make sure to “Like” it, too! Thanks!

Research of the Week

We’ve all heard of the hygiene hypothesis, which posits that excessive sterility is responsible for the increase in allergies and autoimmune diseases. New research suggests that it may extend to Alzheimer’s disease, too.

Strength training has been dubbed safe for kids and teens. Good to have it confirmed.

Interesting Blog Posts

How to check your leg muscle function – and your general preparedness for life – with a simple physical test.

Okay, you’ve got a treadmill desk, and that’s great and all, but can you use it to scroll through a web page or control your Internet speed? (Side note: Check back next Wednesday when I’ll be publishing a video on the standup workstations at both my home and office.)

Media, Schmedia

This is a great story of how the son of an American anthropologist and Yanomami tribeswoman returned to the Amazon in search of his mother, twenty years after she got sick of America and hightailed it back to the jungle.

C-sections are big moneymakers. Is that why they’re on the rise?

Everything Else

Looks like Vibram Fivefingers aren’t so new after all.

Here’s what happens when you stop going outside. It ain’t pretty. Well, the video is actually quite pretty, but the ramifications of avoiding the outdoors are not.

Boy, inadequate sleep really, really messes with the hormones responsible for keeping you lean and healthy.

Recipe Corner

Good dense winter squash is finally beginning to appear in markets around here, so it’s the perfect time to make spicy cocoa-dusted kabocha squash.

Most lamb tagines I’ve had were made with apricots or raisins. Those were good, but I’m really interested in making this one using dates.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Sept 8 – Sept 14)

Starting From Zero – Why starting from what feels like zero isn’t actually all that bad, if you know how to approach it.

Action Item #1: Eliminate SAD Foods – The first thing you must do when going Primal is eliminate the bad stuff. Here’s how to do it.

Comment of the Week

Cynics/skeptics bring the same utility to any discussion about health as a eunuch would bring to an orgy.

- Illustratively (and well!) said, Laurie.

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 7, 2013

Grilled Okra with Spicy Sumac Seasoning Salt

Okra lovers and haters, rejoice. Grilled okra with spicy sumac seasoning salt is an untraditional and finger lickin’ good recipe that will make you fall in love with okra all over again, or, for the very first time.

Okra lovers and haters, rejoice. Grilled okra with spicy sumac seasoning salt is an untraditional and finger lickin’ good recipe that will make you fall in love with okra all over again, or, for the very first time.

Okra is rarely described as addictive. All it takes, though, is a few minutes on a hot grill and a tart and spicy seasoning salt to transform okra into finger food that will fly off the table. Crispy, salty, spicy veggies hot off the grill are better than a bowl of chips, any day. Set them out as an appetizer or snack and eat as many as you like without worrying about spoiling your dinner or your waistline.

Bell pepper and zucchini strips, asparagus, green beans, carrots, even cucumbers, can be thrown on the grill. A grilling basket (or skewers) will keep the veggies from falling through the grates. Olive oil or coconut oil, salt, cayenne and your favorite spices add the finger lickin’ flavor.

Grilling is a really easy way to prepare okra and cuts down on the slime factor. The outside is nicely charred and the fresh, moist middle is a pleasant contrast. Although it’s really the bold, tart flavor of ground sumac blended with thyme, cayenne and salt that transform okra into a killer snack.

This spice blend is similar to za’atar, a Middle Eastern seasoning that also contains toasted sesame seeds and a variety of different herbs. The flavor of sumac is tart and lemony. In addition to thyme, sumac is often blended with cumin, oregano and marjoram (fresh or dried). Play around to find the combination you like best then keep a jar in the kitchen for seasoning not only veggies, but lamb and beef as well.

Servings: 2 to 4, as a snack or appetizer

Time in the Kitchen: 20 minutes

Ingredients:

24 okra

1 tablespoon fresh thyme (15 ml)

1 teaspoon sumac* (5 ml)

1/8 to 1/4 teaspoon cayenne (a pinch)

3/4 teaspoon salt (3.70 ml)

1 tablespoon olive oil (15 ml)

Instructions:

*Look for sumac in the spice aisle of specialty foods stores or Middle Eastern markets

Prepare grill for high heat.

In a small bowl, mix together the thyme, sumac, cayenne and salt.

Trim off the little stems on the end of the okra pods (optional).

In a large bowl, drizzle olive oil over the okra and use your hands to toss until the okra is evenly coated.

Sprinkle the seasoning blend over the okra, tossing the okra with your hands again to evenly coat.

Put the okra in a grilling basket or skewer the pods to keep them from falling through the grill grates.

Grill the okra un-covered until nicely charred, about 4 to 6 minutes on each side.

Serve the okra hot off the grill or soon afterward. When refrigerated, leftover grilled veggies quickly become soggy.

Not Sure What to Eat? Get the Primal Blueprint Meal Plan for Shopping Lists and Recipes Delivered Directly to Your Inbox Each Week

September 6, 2013

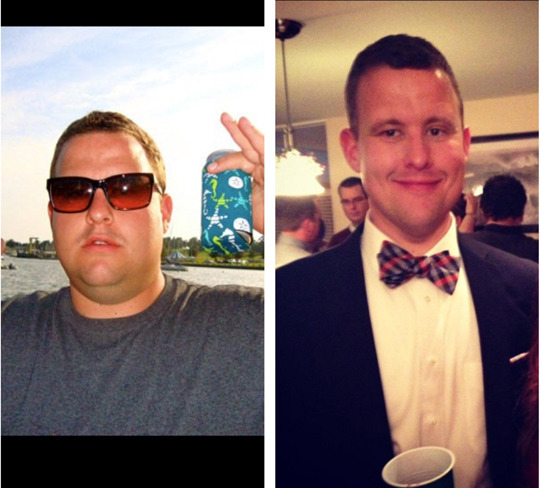

Down 100 Pounds in 9 Months!

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

How I Gained It: For as long as I can remember I have been overweight. As a child I never thought I was inactive. I played all of the neighborhood sports, league baseball, rode bikes, I was always outside with my core group of friends in Island Park, RI. It was my diet that led me to be overweight. I would consume pizza, fast food, chips, cookies and everything else under the sun. It really got out of control when I got my drivers license. I now had access to a job and a car and could buy anything I wanted to eat. It was like this through high-school, college, and even in my job on a tugboat. Tugboats can be a very sedentary lifestyle. There is not much walking around on a 100ft boat. With access to all of the boat’s food, I was eating a lot with not much exercise. It is a very unhealthy lifestyle. I work on the boat for 3 weeks and then I am home for 3 weeks. The time spent at home was sleeping and eating and drinking, that was all I did.

How I Gained It: For as long as I can remember I have been overweight. As a child I never thought I was inactive. I played all of the neighborhood sports, league baseball, rode bikes, I was always outside with my core group of friends in Island Park, RI. It was my diet that led me to be overweight. I would consume pizza, fast food, chips, cookies and everything else under the sun. It really got out of control when I got my drivers license. I now had access to a job and a car and could buy anything I wanted to eat. It was like this through high-school, college, and even in my job on a tugboat. Tugboats can be a very sedentary lifestyle. There is not much walking around on a 100ft boat. With access to all of the boat’s food, I was eating a lot with not much exercise. It is a very unhealthy lifestyle. I work on the boat for 3 weeks and then I am home for 3 weeks. The time spent at home was sleeping and eating and drinking, that was all I did.

Breaking Point: I had always thought about losing weight but never gave it a fair try. I thought about it everyday. The hardest part for me was trying to find clothes. I would have to order them online or go to big and tall stores. There are only so many styles at those stores and I definitely didn’t like many of them. On January 1, 2012 I decided I needed to change, not just for being able to buy nicer clothes but for my health. The US Coast Guard is in charge of Merchant Mariner licenses and they have been cracking down on BMIs in the industry. I had my annual physical coming up in March 2012. So I figured if I jumped into a healthier lifestyle I would have 3 months to shed some weight.

How I Lost Weight: My close friend Ryan suggested I read a book by the name of The Primal Blueprint by Mark Sisson. This book covers the paleo Lifestyle. Eating like our caveman ancestors. I figured I could eat meat and veggies and be happy with it. After diving head first into the book I adopted a paleo way of eating. I found it to be very easy especially while reading every paleo book I could get my hands on. During my March physical I had lost 40 pounds with little effort. In fact, my doctor and nurse were shocked when I walked in. The nurse even asked, “do you realize you lost 40lbs”? I jokingly said “I had no idea”. Then they bombarded me with questions about paleo because they had never heard of it. I decided against exercising and to focus on my diet. It was September 2012 and I was down 100lbs. 100lbs in 9 months! I started to exercise after that and have been to this day.

The weight loss has slowed down a bit but muscle weighs more than fat, right? I have lost 130lbs total. I go to the gym everyday and mix in cardio and weight lifting. I really enjoy it now. I never thought I would enjoy going to the gym. My biggest joy of losing the weight is helping other people. I love talking paleo and I have even started a blog to help my friends WWJME.com (What Would John Mack Eat?). I can’t tell you how happy I am. It truly is a life changing event. My new goal is to get to 220lbs and go from there. My even bigger goal is to help people with losing weight.

Age: 30

Height: 6′ 1″

Before Weight: 370 pounds

After Weight: 240 pounds

John Mack

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

Down 100 Pounds in 9 months!

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

How I Gained It: For as long as I can remember I have been overweight. As a child I never thought I was inactive. I played all of the neighborhood sports, league baseball, rode bikes, I was always outside with my core group of friends in Island Park, RI. It was my diet that led me to be overweight. I would consume pizza, fast food, chips, cookies and everything else under the sun. It really got out of control when I got my drivers license. I now had access to a job and a car and could buy anything I wanted to eat. It was like this through high-school, college, and even in my job on a tugboat. Tugboats can be a very sedentary lifestyle. There is not much walking around on a 100ft boat. With access to all of the boat’s food, I was eating a lot with not much exercise. It is a very unhealthy lifestyle. I work on the boat for 3 weeks and then I am home for 3 weeks. The time spent at home was sleeping and eating and drinking, that was all I did.

How I Gained It: For as long as I can remember I have been overweight. As a child I never thought I was inactive. I played all of the neighborhood sports, league baseball, rode bikes, I was always outside with my core group of friends in Island Park, RI. It was my diet that led me to be overweight. I would consume pizza, fast food, chips, cookies and everything else under the sun. It really got out of control when I got my drivers license. I now had access to a job and a car and could buy anything I wanted to eat. It was like this through high-school, college, and even in my job on a tugboat. Tugboats can be a very sedentary lifestyle. There is not much walking around on a 100ft boat. With access to all of the boat’s food, I was eating a lot with not much exercise. It is a very unhealthy lifestyle. I work on the boat for 3 weeks and then I am home for 3 weeks. The time spent at home was sleeping and eating and drinking, that was all I did.

Breaking Point: I had always thought about losing weight but never gave it a fair try. I thought about it everyday. The hardest part for me was trying to find clothes. I would have to order them online or go to big and tall stores. There are only so many styles at those stores and I definitely didn’t like many of them. On January 1, 2012 I decided I needed to change, not just for being able to buy nicer clothes but for my health. The US Coast Guard is in charge of Merchant Mariner licenses and they have been cracking down on BMIs in the industry. I had my annual physical coming up in March 2012. So I figured if I jumped into a healthier lifestyle I would have 3 months to shed some weight.

How I Lost Weight: My close friend Ryan suggested I read a book by the name of The Primal Blueprint by Mark Sisson. This book covers the paleo Lifestyle. Eating like our caveman ancestors. I figured I could eat meat and veggies and be happy with it. After diving head first into the book I adopted a paleo way of eating. I found it to be very easy especially while reading every paleo book I could get my hands on. During my March physical I had lost 40 pounds with little effort. In fact, my doctor and nurse were shocked when I walked in. The nurse even asked, “do you realize you lost 40lbs”? I jokingly said “I had no idea”. Then they bombarded me with questions about paleo because they had never heard of it. I decided against exercising and to focus on my diet. It was September 2012 and I was down 100lbs. 100lbs in 9 months! I started to exercise after that and have been to this day.

The weight loss has slowed down a bit but muscle weighs more than fat, right? I have lost 130lbs total. I go to the gym everyday and mix in cardio and weight lifting. I really enjoy it now. I never thought I would enjoy going to the gym. My biggest joy of losing the weight is helping other people. I love talking paleo and I have even started a blog to help my friends WWJME.com (What Would John Mack Eat?). I can’t tell you how happy I am. It truly is a life changing event. My new goal is to get to 220lbs and go from there. My even bigger goal is to help people with losing weight.

Age: 30

Height: 6′ 1″

Before Weight: 370 pounds

After Weight: 240 pounds

John Mack

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 5, 2013

The Impact of Loneliness

We’ve likely all felt it at some point in our lives – those depressing days (or more) when we walk through the world feeling like we’re traveling on a separate plane of existence from the rest of the happily coupled and connected human race. For some of us, however, these blips in social well-being take on a chronic trajectory, an ongoing emotional journey of their own. Loneliness can seem like a self-exacerbating condition. We’re isolated, and we’re unsure how to break through it. Some of us enjoy lifelong proximity to extended family, intact partnerships and childhood friendships that take us from grade school to grave. For many of us, however, we socialize more on Facebook than at our kitchen tables. We might have a strong core (“nuclear”) family but no friends in our current locales that we could call on at 2:00 in the morning.

We’ve likely all felt it at some point in our lives – those depressing days (or more) when we walk through the world feeling like we’re traveling on a separate plane of existence from the rest of the happily coupled and connected human race. For some of us, however, these blips in social well-being take on a chronic trajectory, an ongoing emotional journey of their own. Loneliness can seem like a self-exacerbating condition. We’re isolated, and we’re unsure how to break through it. Some of us enjoy lifelong proximity to extended family, intact partnerships and childhood friendships that take us from grade school to grave. For many of us, however, we socialize more on Facebook than at our kitchen tables. We might have a strong core (“nuclear”) family but no friends in our current locales that we could call on at 2:00 in the morning.

In addition to the serious emotional toll, research suggests the physical fallout is rather grim as well. Studies have linked loneliness and social isolations to everything from cancer to cardiovascular disease, inflammation to immune issues. Additionally, loneliness can cause us to develop excessive reactivity to stress and throw our cortisol levels as well as our blood pressure into unhealthy territory. Its negative health impact is reportedly on par with that of smoking in terms of mortality risk. On the less immediately dire but disturbing end of things, it appears to set us up for pain, fatigue and depression. Although we might think more often of older adults and social isolation, there’s really something to the developmental processes of adolescence that put young adults at a higher risk for feelings of social isolation. What’s worse? Those who experience high or chronic levels of loneliness in those first couple decades of life fare worse down the road in terms of both mental and physical health. Something doesn’t feel too Primal here.

As I’ve suggested before, there’s something to the ancestral context – the genetically wired, “expected” conditions that characterized our evolutionary history. Extended isolation meant almost sure death in our ancestors’ days. The risk was so great, we evolved sophisticated social natures to keep ourselves voluntarily bound to our insulating band communities, which presumably ran somewhere in the 20-50 person range, although they likely had a larger circle of neighboring acquaintances and extended family numbering around 150 known today as Dunbar’s number for social cohesion.

These days our social lives often bear little to no resemblance to that of our Primal forebears. In the culture of social media, we often settle (or sometimes compete) for the appearance of connections rather than the realities (beneficial and challenging) of intimacy. We’ve lost the preference for – and maybe even understanding of – what truly fills the well socially. Far, far away from the standards of our ancestral conditions, I often think our barometers have become skewed – when we listen to our culture instead of our clearer instincts anyway. Can we differentiate, for example, loneliness from solitude, that vital and therapeutic experience of simply being fully present to yourself? Do we have the same collective sense of give and take, grown up friendships that are tested (and grown) by change over time? Some suggest we often settle into a collection of “situational friendships,” connections organized (and separated) by setting or life activity. What do we end up missing as a result?

Although it seems to be less directly studied, I think much of our loneliness and isolation can often come as a result of our estrangement from that larger context of our “expected environment” as well. The same loneliness that can feel soul-crushing day after day in your living room feels more porous, even dispersed, in the middle of a forest next to a rushing river. In the living, breathing world of nature – even if there’s not another hominid within 10 miles – I think we instinctually feel the age-old sense of kinship. We’re home in a manner of evolutionary speaking. We’re also in the presence of something larger than ourselves. You could say we’re taken down to right size, which might at first glance seem more depressing, but I think it’s a question of restorative humility. The dimensions of the modern Self can become distorting and downright burdensome. In certain situations, a portion of loneliness might be the psychic rut of inadvertent solipsism.

That said, there are still older adults who live out their days in institutions without a single visitor and few connections among their co-residents. There are adolescents who feel stuck in a social arena they’ll never fit into and simply aren’t connected to any other rooted and functional family or community circles. There are new mothers at home who feel isolated more days than they can count because they can’t find a way off a hamster wheel of caregiving they never could’ve envisioned. There we might see any of us at a given time of our lives when the roots are pulled up by choice or circumstance and social connections dissipated through death, divorce, relocation or maybe just forgetfulness. Each day we’re overwhelmed by the demands of just living and working. We put off maintaining or making social connections. Years later, we look around and wonder what happened to our friendships and close family relationships. The realization alone can induce a regretful burden of loneliness – not to mention the shadows of those other health effects….

The fact is, our modern social circle is much more disjointed than that of our ancestors. We accept fragmentation as a necessary condition of modern progress, career climbing and “free” living. We all have to make those choices, and it’s not about right or wrong. Sure, there’s something to knowing your neighbors, having them see your kids grow up and feeling like you can call people around the corner at 2:00 a.m. if you need to. It’s a sense of knowing and feeling known, of nurturing a visceral bond with community and place that comes with, as author Scott Russell Sanders examines it, “staying put.”

Long term communities and commitments aside, however, I’ve experienced first-hand how powerful it can be to meet people who feel like long lost family. Relationships can burst onto the scene as well as evolve. In the newest of places and the oddest of circumstances, meaningful and transformative social connections can take hold. Some of my closest friends today are those I met later in my life. I was following a new vision for myself at the time, and with that came an unconscious openness to new connections. Sometimes it depends as much on where we’re at in our individual journeys as where we’re at geographically.

On that note, let me put in a plug for the Grokfeasts that will again be part of this year’s upcoming 21-Day Challenge. Attending or organizing a Grokfeast is a great way to discover like-minded people in your area and celebrate Primal living in community. I know many a continuing social circle and genuine friendship (even relationship!) that have come as a result of these and related meetups!

Thanks for reading, everyone. Let me know your thoughts on the connection between loneliness and compromised well-being. Have a good end to the week.

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 4, 2013

This Gluten-Free Thing Is a Really Overblown Fad!

This is a comment I’m starting to see more and more often. Go to any news article about gluten and the comment section will be littered with angry outbursts and outright vitriol for people who go gluten-free. Skeptical blogs love to trot out posts lambasting and ridiculing the “gluten-free fad.” And from what I can tell, nothing inspires a contemptible eye-roll like a person asking a waiter in a restaurant if they have gluten-free options. By some stretch of the known laws of cause-and-effect, the removal of gluten from someone’s diet apparently causes irreparable harm to people with knowledge of the decision and deserves unequivocal reprobation. Otherwise, why else would they care so much?

This is a comment I’m starting to see more and more often. Go to any news article about gluten and the comment section will be littered with angry outbursts and outright vitriol for people who go gluten-free. Skeptical blogs love to trot out posts lambasting and ridiculing the “gluten-free fad.” And from what I can tell, nothing inspires a contemptible eye-roll like a person asking a waiter in a restaurant if they have gluten-free options. By some stretch of the known laws of cause-and-effect, the removal of gluten from someone’s diet apparently causes irreparable harm to people with knowledge of the decision and deserves unequivocal reprobation. Otherwise, why else would they care so much?

Well, gluten-free is clearly more popular than ever. More and more people are becoming aware of it. Google searches for “gluten” have been trending higher month over month for years, while the number of searches for “celiac” has plateaued. 30% of American adults are actively trying to reduce or eliminate gluten from their diets, according to a recent poll. Gluten-free dating sites are popping up to help gluten-free dieters match up with people who share their situation. The FDA’s just weighed in with some official standards for gluten-labeling. It’s everywhere, in other words. It’s arrived. It’s popular. And whenever anything gets popular, people immediately begin hating it. I’m not sure why that is, really, but it’s a known human phenomenon. Couple that with your already annoying co-worker droning endlessly on about this new diet she’s on, and I can see how someone might get a bit annoyed at all the gluten-free talk.

But is the vitriol really necessary? Does its popularity invalidate it as a legitimate therapeutic option for people with a sensitivity or downright intolerance to gluten? Should incurious cynics masquerading as skeptics be so quick to dismiss it?

Okay, maybe sometimes people can be a bit evangelical about avoiding gluten, and that’s unpleasant. And sometimes, people can’t give you a straight answer when you grill them on exactly why they’re avoiding gluten. I’d wonder why you felt it was your place to “grill them” in the first place, of course, but there is that subset of the population who takes umbrage at people making health decisions without conducting randomized controlled trials, being able to cite research by memory, and consulting the authorities.

I’ll also admit that the prospect of marketers taking over and appropriating the movement for their own benefit concerns me. For many people, a “gluten-free” label unfortunately bestows a cachet of health onto whatever processed food it graces. Potato chips? They’re gluten-free! Triple-chocolate brownie mud slide fudge-topped soy flour locust bean gum explosion? Gluten-free! Eat without guilt! Gluten-free bread that makes up for the lack of gluten’s texturizing power with a half cup of soybean oil? Go for it! Even foods that never contained gluten in the first place, like Cheetos, and hummus, are getting the gluten-free label to capitalize on the trend.

On one hand, it’s like the fat-free labeling craze, where you had fat-free cookies with twice the sugar, fat-free yogurt with thrice the sugar, fat-free salad dressing with whatever sorcery they incorporated to make that possible. And people ate those things with willful abandon, confident that “fat-free” was a synonym for “healthy” – and obesity rates continued to rise. Heck, the fat-free movement most likely exacerbated America’s obesity problem. I can understand why people who mistrust food marketing would be skeptical of gluten-free in general.

Of course, there is an important difference that distinguishes gluten-free from other faddish, market-driven diets: you don’t actually need gluten-free products to go gluten-free. The fat-free movement turned people off of legitimately healthy nutrient-dense foods like beef, eggs, butter, nuts, avocados, and olive oil just because they contained fat, whereas going gluten-free doesn’t remove a vital, essential nutrient or food. In fact, it can even increase your intake of nutrients, assuming you replace the gluten-containing foods with naturally gluten-free meat, fish, fruits, vegetables, and nuts rather than gluten-free junk food. In my experience, gluten-free consumers are more informed about health in general and do the former.

Amidst all the marketing speak, the gluten-free water, the gnashing of teeth upon discovering that the person you’re talking to avoids gluten, real science is being done, and any honest, literate person who looks at the available evidence on the health effects of gluten will admit that there’s something to this “fad.” And yet, I’m increasingly struck by the unwillingness of intelligent people to acknowledge the reams of research coming out every week exploring the effects of gluten on non-celiacs.

It couldn’t be that non-celiac gluten sensitivity is real and we don’t know how many people actually have it as the epidemiology is too new and underdeveloped. It can’t possibly be that gluten-free diets might reduce adiposity/inflammation via epigenetic effects (potentially reaching across generational lines). There’s no way that gluten free diets help non-celiac IBS patients who had no preconceived notions of gluten-free dieting (and thus no risk of being influence by the hype). And that case study of the child with type 1 diabetes going into remission with a gluten free diet? Let’s just sweep that under the rug and completely forget about it. Oh, what about the link between autism and non-celiac gluten sensitivity? Doesn’t exist. PubMed is a liar. Those autistic kids with GI symptoms who do respond positively to a gluten-free diet? They don’t, and the study you just thought you read is a figment of your imagination. All that hubbub about modern dwarf wheat being more allergenic than ever is also nonsense. Besides needing a stool to reach the top shelf, modern wheat is totally identical to older wheat and is no more allergenic.

Another popular canard is the “celiac is too rare for most people to worry about” one. Well, about that: the latest research out of Australia (a remarkably gluten-conscious country) shows that celiac is far more prevalent than previously thought and about 50 percent of the population carries the genetic markers associated with gluten sensitivity. Scientists used a combination of traditional antibody testing (which measures the immune response to gluten) with analysis of genetic risk factors for celiac to reach their conclusions. Not everyone with risk factors actually displayed gluten intolerance or celiac disease, of course, but the presumption is that some combination of environmental factors – inflammatory diet, damaged gut microbiome, etc. – could trigger its expression. (Epigenetics rears its head yet again.) Most people skeptical of gluten-free diets take an “either you are or you aren’t” stance on gluten sensitivity or celiac disease, while the results of the Australian research would suggest that it’s far more dynamic and that a large portion of the population can develop issues with gluten given the right (or wrong) environmental context.

Nope, forget all that research: it’s just people latching onto a fad. It’s just nearly a third of Americans going gluten-free because Miley Cyrus did it (I eagerly await widespread adoption of twerking by millions of soccer moms). It’s millions of people sticking with a dietary regimen that offers no tangible benefits and actually makes them actively unhealthier. And if there is a benefit, it’s all in their heads.

I guess it’s easier to pick on the easy targets and ignore the people with evidence. It’s easy to dismiss the entire movement because of a few misinformed trend-followers, but it’s dishonest. Look – I’m all for the denunciation of health fads and trends that don’t make sense and are based on spurious claims, but not everything that’s popular is bad.

My favorite thing is when “concerned health experts” caution against starting a gluten-free diet without talking to your doctor, paying for a test to determine a gluten allergy, and consulting with a registered dietitian. As if giving up bread, pasta, and cake for more animals and plants is a dangerous undertaking that requires professional assistance. As if removing gluten and feeling loads better only to feel terrible upon a chance reintroduction is an unreliable way to determine if you should go gluten-free.

Here’s why I welcome the explosion in gluten-free awareness, even if it all amounts to a whole lot of nothing for some people: it leads to an overall more healthy diet. Even if you can eat gluten without incident, even if your gut flora is able to cleave gluten in twain for easy digestion, you will still get more nutrients by replacing your grain products with more meat, seafood, vegetables, roots, and fruit. Sure, you’ve got the folks who go gluten-free by swapping in gluten-free versions of all their favorite foods and end up eating nutrient bereft diets full of refined alternative flours, but I think they’re in the minority for a few reasons.

First, gluten-free junk food tastes worse than the originals, although that’s changing as the market grows and food producers improve their methods.

Second, gluten-free products are generally more expensive than the regular products.

Third, in my experience, people who go gluten-free usually stumble into a Primal way of eating. The way I see it playing out is you have sweet potatoes or rice instead of rolls at dinner. You go with a real corn tortilla or lettuce wrap tacos instead of burritos. Instead of buying all that gluten-free bread that turns into dust at the slightest touch, you spend the money on meat and vegetables. You go out to eat at a burger joint and maybe they don’t have the gluten-free bun that day, so you have the patty on a salad and realize it’s not such a bad way to eat – and you stick with it.

I’ve read the studies. I’ve consulted the experts (who are actually studying this stuff). I’ve witnessed the incredibly positive changes in thousands of readers, friends, family members, and clients who gave up gluten (and most grains for that matter). Heck, I’ve felt it myself. Is there something to this whole gluten-free thing?

I’d say so, yeah.

What about you?

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

September 3, 2013

Dietary Fiber Is Bad for Sex – That’s the Only Claim About It That Isn’t a Myth

Today’s article is a guest post from Konstantin Monastyrsky of GutSense.org. In keeping with the mission statement of Mark’s Daily Apple to investigate, discuss, and critically rethink everything we’ve assumed to be true about health and wellness, I like to periodically give credible researchers who are challenging conventional wisdom the opportunity to share their insights and findings here. It’s a great way to open a dialogue on topics that deserve challenging. Like fiber, for instance. Everyone knows that fiber is good for you, right? Well, let’s find out what Konstantin—a guy who’s spent an incredible amount of time researching this topic—thinks about this truism. Enter Konstantin…

Today’s article is a guest post from Konstantin Monastyrsky of GutSense.org. In keeping with the mission statement of Mark’s Daily Apple to investigate, discuss, and critically rethink everything we’ve assumed to be true about health and wellness, I like to periodically give credible researchers who are challenging conventional wisdom the opportunity to share their insights and findings here. It’s a great way to open a dialogue on topics that deserve challenging. Like fiber, for instance. Everyone knows that fiber is good for you, right? Well, let’s find out what Konstantin—a guy who’s spent an incredible amount of time researching this topic—thinks about this truism. Enter Konstantin…

Does dietary fiber contain anything of nutritional value? No, it doesn’t. Zero vitamins… Zero minerals… Zero protein… Zero fat… Nothing, zilch, not even digestible carbohydrates. Why, then, is it considered a healthy nutrient? As the story goes, you can thank Dr. John Harvey Kellogg for that:

“Dr. Kellogg was obsessed with chastity and constipation. True to principle, he never made love to his wife. To “remedy” the sin of masturbation, he advocated circumcision without anesthetic for boys, and mutilation of the clitoris with carbolic acid for girls. He blamed constipation for “nymphomania” in women, and lust in men, because, according to Kellogg, impacted stools inside one’s rectum were stimulating the prostate gland and the female vagina into sexual proclivity.” [link]

To fix these “ailments,” Dr. Kellogg was prescribing a coarse vegetarian diet along with 1 to 3 ounces of bran daily, and mineral oil with every meal. As any nutritionist will tell you, the decline of libido and infertility are among the very first symptoms of malnutrition prevalent among ardent vegans. And in this particular case, extra bran and mineral oil were “enhancing” damage by blocking the assimilation of nutrients from an already meager diet.

And what was Dr. Kellogg’s rationale for prescribing mineral oil? Well, because so much fiber was enlarging stools, intense straining was required to expel them. The oil was used as a lubricant to reduce pain caused by straining, and to prevent bloody anal fissures inside the anal canal.

However, the ultimate fame and money came to Dr. Kellogg not from crusading against sex, but from ready-to-eat morning cereals after he found that baking bran into cereals proved to be incredibly profitable for Kellogg Company. From that point on, it took another sixty years or so of relentless brainwashing to turn what once used to be a dirt-cheap livestock feed into a premium health food.

Well, that’s an old story, and I can understand if you doubt it—it sounds too incredulous to be true! So, let’s debunk fiber’s mythology with facts and science. Here we go, one myth at a time:

Myth #1: For maximum health, obtain 30 to 40 g of fiber daily from fresh fruits and vegetables.

Reality: Here is how many fresh fruits you’ll need to eat throughout the day in order to obtain those 30 to 40 grams (1-1.4 oz.) of daily fiber:

As you can see, that comes to five apples, three pears, and two oranges. A small apple contains 3.6 g of fiber and 15.5 g of sugars. A small pear—4.6 g and 14.5 g; and a small orange—2.3 g and 11.3 g, respectively (USDA National Nutrient Database; NDB #s: 09003; 09200; 09252 [link]).

These ten small (not medium or large) fruits will provide you with 36.4 g of indigestible fiber and a whopping 143.6 g of digestible sugars, or an equivalent of that many (ten) tablespoons of plain table sugar!

And that‘s before accounting for all the other carbs consumed throughout the day for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and from snacks and beverages.

So ask yourself this question: even if you are a 100% healthy 25-year-old muscle-bound athlete, would you ever ingest that much sugar willingly? Well, maybe under the influence of a controlled substance or torture…

But that’s exactly what’s being recommended for “health purposes” to children and adults. It‘s not surprising that so many Americans are suffering from the ravages of diabetes and obesity—a moderately active adult can utilize no more than about 200 grams of carbohydrates per day without encountering a scourge of the inevitable obesity, prediabetes, or diabetes.

The ratio of digestible carbohydrates (sugars) to fiber in vegetables, cereals, breads, beans, and legumes is, on average, similar to fruits. Thus, no matter how hard you try to mix’n’match, you’ll be getting harmed all the same.

Please do note that if you are healthy, active, and normal weight, there is nothing wrong with consuming fruits and vegetables in moderation. The point of this section is to impress on you that it is NOT OK to binge on fruits to ingest recommended daily intake of fiber.

This myth—that fruits and vegetables are the best source of dietary fiber—is probably the most pervasive and damaging of all. If 30 grams of fiber is what you’re really after, you’re better off getting it from supplements. These, after all, have almost no digestible carbs. But, then, of course, you run into those other persistent falsehoods…

Myth #2: Fiber reduces blood sugar levels and prevents diabetes, metabolic disorders, and weight gain.

Reality: That’s a blatant deception. If you consume 100 g of plain table sugar at once, the blood absorbs all 100 g of sugar almost as soon as it reaches the small intestine, where the assimilation takes place. If you add 30 g of fiber into the mix, the fiber may extend the rate of sugar assimilation into the blood, from, let‘s say, one hour to three.

But at the end of those extra three hours the blood will still absorb exactly the same 100 g of sugar—not an iota more, not an iota less. If you are a diabetic, the only difference will be that you‘ll require more extended (long-acting) insulin for type 1 diabetes, or larger doses of medication for type 2 diabetes in order to deal with slow-digesting sugars, and your blood glucose test will not spike as high after the meal.

But you‘re fooling no one but a glucose meter. In all other respects, the damage will be all the same, or even worse. And that‘s even before taking into account the negative impact of fiber on the digestive organs, or hyperinsulinemia and triglycerides on the heart, blood vessels, and blood pressure.

Myth #3: Fiber-rich foods improve digestion by slowing down the digestive process.

Reality: Fiber indeed slows down the “digestive process,” because it interferes with digestion in the stomach and, later, clogs the intestines the “whole nine yards.” The myth is that it can be good for health and the digestive process.

Here is what you get from delayed digestion: indigestion (dyspepsia), heartburn (GERD), gastritis (the inflammation of the stomach‘s mucosal membrane), peptic ulcers, enteritis (the inflammation of the intestinal mucosal membrane), and further down the chain, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn‘s disease.

All this, in fact, is the core message of Fiber Menace: fiber slows down the digestive process! And slow digestion is ruinous for your health. Don‘t mess with fiber unless your gut is made of steel!

Myth #4: Fiber speeds food through the digestive tract, helping to protect it against cancer.

Reality: Not true. In fact, this claim directly contradicts the claim that fiber-rich foods slow down the digestive process. For a reality check, here’s an excerpt from a college-level physiology textbook that reveals the truth:

“Colonic Motility: Energy-rich meals with a high fat content increase motility [the rate of intestinal propulsion]; carbohydrates and proteins have no effect.”

R.F. Schmidt, G. Thews; Human Physiology, 2nd edition. 29.7:730 [link]

This, incidentally, is why low-fat diets and constipation commonly accompany each other. And don’t count on getting any cancer protection from fiber, either. That‘s yet another oft-repeated deception.

Myth #5: Fiber promotes a healthy digestive tract and reduces cancer risk.

Reality: Not true. Here’s what doctors-in-the-know have to say on the subject of the colon cancer/fiber connection:

Lack of Effect of a Low-Fat, High-Fiber Diet on the Recurrence of Colorectal Adenomas

“Adopting a diet that is low in fat and high in fiber, fruits, and vegetables does not influence the risk of recurrence of colorectal adenomas.”

Arthur Schatzkin, M.D et al. The New England Journal of Medicine; [link]

The excerpt below comes, of all places, from the Harvard School of Public Health:

Fiber and colon cancer

“For years, Americans have been told to consume a high-fiber diet to lower the risk of colon cancer—mainly on the basis of results from relatively small studies. Larger and better-designed studies have failed to show a link between fiber and colon cancer.”

Fiber: Start Roughing It [link]

Not convinced yet? Well, here is even more damning evidence from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration:

Letter Regarding Dietary Supplement Health Claim for Fiber With Respect to Colorectal Cancer

“Based on its review of the scientific evidence, FDA finds that (1) the most directly relevant, scientifically probative, and therefore most persuasive evidence (i.e., randomized, controlled clinical trials with fiber as a test substance) consistently finds that dietary fiber has no [preventive] effect on incidence of adenomatous polyps, a precursor of and surrogate marker for colorectal cancer; and (2) other available human evidence does not adequately differentiate dietary fiber from other components of diets rich in foods of plant origin, and thus is inconclusive as to whether diet-disease associations can be directly attributed to dietary fiber. FDA has concluded from this review that the totality of the publicly available scientific evidence not only demonstrates lack of significant scientific agreement as to the validity of a [preventive] relationship between dietary fiber and colorectal cancer, but also provides strong evidence that such a relationship does not exist.”

U. S. Food and Drug Administration – Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Office of Nutritional Products, Labeling, and Dietary Supplements; [link]

Alas, the story doesn’t end there. Adding insult to injury, Chapter 10 of my book entitled Fiber Menace, “Colon Cancer” cites studies that demonstrate the connection between increased fiber consumption and colon cancer. Also, countries with the highest and lowest consumption of meat are compared. Not surprisingly, the countries with the lowest consumption of meat and, correspondingly, the highest consumption of carbohydrates, including fiber, have the highest rate of digestive cancers, particularly of the stomach.

Myth #6: Fiber offers protection from breast cancer.