Mark Sisson's Blog, page 311

January 29, 2014

19 Tips for Avoiding Injuries During Sprint Sessions

Sprinting is a powerful asset to any training program. It’s brief and effective and long-lasting and reverberates throughout multiple aspects of health and performance. If you sprint regularly, you’ll likely improve your body composition, strength and fitness levels, metabolic flexibility, stamina, and explosiveness. Since sprinting is “going as fast as you can,” it’s infinitely and instantly scalable to your ability level. Anyone who can sprint but does not is making a huge mistake.

Sprinting is a powerful asset to any training program. It’s brief and effective and long-lasting and reverberates throughout multiple aspects of health and performance. If you sprint regularly, you’ll likely improve your body composition, strength and fitness levels, metabolic flexibility, stamina, and explosiveness. Since sprinting is “going as fast as you can,” it’s infinitely and instantly scalable to your ability level. Anyone who can sprint but does not is making a huge mistake.

However, with great power comes great responsibility. You have to do it right. Sprinting actually isn’t very dangerous compared to other athletic pursuits. You’re more liable to get injured playing a team sport, where you’re responding quickly to unpredictable changes in the game, moving laterally and vertically, diving and leaping for balls or discs, jostling for position. Sprinting is linear, straightforward. You go from point A to point B. However, the very thing that makes sprinting work so well – the fact that it represents the highest intensity your body can muster – can lead to injury if you’re not prepared.

So make sure to be prepared. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

1. Raise your body temperature.

Literally warm yourself up a bit. This could be a short, brisk walk, a few minutes on a bike, rolling around on the floor like a kid, or even a really light jog. Just get warm. This is why sprinting in really cold weather requires extra prep – your body is really, really cold, which can increase injury risk. Heck, it might even mean taking a hot bath before training.

2. Don’t static stretch before.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to construct a controlled trial testing the effects of different stretching modalities on sprinting injuries. You’d have to come up with an “injury-inducing”, and that’s just not ethical. What we do have is plenty of research into the effect of various types of stretching on sprint performance. Generally speaking, improved performance is a barometer for good technique, which is a fair representation of safety and protection from injury. Most studies suggest that static stretching before sprinting impedes performance.

3. Instead, do dynamic stretches.

Dynamic stretches are active stretches that involve movement through the full range of motion. Some sprint-specific ones include:

High knees

Butt kicks

Toy soldiers

A couple rounds of those should suffice. Do about 10-20 meters for each move per round.

4. Do dynamic stretches before, but not too many.

Dynamic stretching before sprinting improves performance, but there is a limit. One study found that while one to two sets of 20 meter long dynamic stretch drills improved subsequent sprint performance, three sets impaired performance by inducing fatigue. Do enough dynamic stretching that you feel energized and ready to go. Stop short of doing so many that you start getting tired.

5. Do a few depth jumps.

This is a depth jump. In one recent study, subjects who performed three depth jumps a minute before sprinting improved their performance. Three depth jumps are enough to “shock” the nervous system and get it prepared to move your body, but not enough to impair your performance or fatigue your legs. A few deep squat jumps should work, too.

6. Do a few trial ramp up runs.

Run several half sprints before your real session starts, starting at about 50% intensity and steadily increasing it until you hit 80% in the last one. These are all rough approximations, of course. Just work up to near-full intensity. Beginners may want to hold off from hitting full intensity for a few sprint sessions as they get used to it.

7. Use proper technique.

Good technique is paramount. It won’t just make you faster; it will protect you.

Maintain a balanced center of gravity at all times, never overstride. When landing don’t let your feet land way out in front.

Stand as tall as possible – never collapse weight into ground.

Torso and hips should face forward at all times.

Arms swing fore and back – never side to side – locked at 90 degree angle.

Bicycle style stride: flex foot immediately after takeoff and snap foot back onto the ground quickly.

Generate explosive force with each footfall: midfoot landing, Achilles snap to touch ground, explosive midfoot takeoff. Foot on ground as short a time as possible.

The difference between Usain Bolt and you the reader is more explosive force per stride and less time on ground per stride. Stride frequency is nearly identical believe it or not. Your turnover is almost identical to Usain Bolt but you only generate half as much force per stride. Hence, Usain’s strides are 9 feet long due to the explosive force.

8. Only run barefoot if your feet are conditioned.

Barefoot sprinting is one of life’s greatest joys. I do all my sprinting barefoot (on the beach), in fact. But if you’re not accustomed to going barefoot, sprinting can introduce an excessive amount of loading to your tissues. Remember: it takes awhile to undo a lifetime of shoe-wearing.

9. Never run barefoot on rubberized tracks.

Those tracks are made for traction, but you don’t really want that much traction applied to your bare feet. You’ll rip the skin clean off (I’ve seen it happen). They’re great when you’re wearing shoes, though.

10. Stop while you’re ahead.

Think you’ve got “one more in ya”? Stop. End your workout. That’s exactly when you need to quit. Sprinting should not be done to failure, because failure means fatigue and fatigue is when systems fail, technique breaks down, and injuries occur. Stopping just short of that point is ideal for injury prevention. I always stop my workout right when I figure I have another one or two in me. It’s just not worth it.

11. Optimize your rest intervals.

When I sprint, I usually try to recover as completely as I can between sprints. If I’m running 30 second sprints (rare for me these days), I’ll usually rest for at least four minutes. If I’m running 10-15 second sprints, I’ll rest about two minutes. If I’m doing real short 3-5 second bursts, I’ll only rest about 20 seconds or so. I go by how I feel, though – not the numbers or some formula. When I’m rested and ready, I sprint. Folks looking to maximize their cardiovascular fitness will probably want to reduce the length of their rest periods, but full recovery is safest.

12. Sprint when fully recovered from the last workout.

Don’t sprint after heavy deadlifts (your hamstrings will be fried). Don’t sprint two days in a row (you won’t have recovered). Don’t sprint after a sleepless night (your balance and proprioception will be impaired).

13. Choose the right surface.

Generally speaking, natural surfaces are better for sprinting than manmade ones. In a comparison of plantar loading forces, running on natural grass resulted in lighter loading on the rear and forefoot, while running on asphalt placed considerably more stress on the rear and forefoot. Many top sprinters, including Usain Bolt, even promote training on grass tracks to reduce the impact to joints and bones. I love sprinting in sand. It’s harder (since your feet are sinking into the sand) and easier (since the sand is dampening your foot’s impact) at the same time. Lower impact, more difficulty.

The only time I sprint on pavement is uphill (which significantly reduces impact forces). I usually advise against it. Most of us aren’t sixth graders with invincible bones and joints playing freeze tag on the blacktop playground anymore.

14. Don’t sprint on a treadmill.

Some people pull this off, but it can be pretty dangerous – far more dangerous than sprinting out on solid ground. For one, it changes the kinematics of the hamstring and increases the risk of hamstring pulls. Two, it’s hard to go all out on a treadmill without overshooting, falling off, or holding back. I’ve never been able to really go for it on a treadmill. Something lingers in the back of my mind and holds me back. If you’re sprinting in the gym, use an exercise bike or a rower instead of the treadmill.

15. If you’ve got a prior history of hamstring pulls, knee pain, or other lower body injuries, favor hill sprints over flat sprints.

The number one risk factor for a pulled hamstring while running is having had one previously. The best way to pull a hamstring while sprinting is to overextend your leg so that your foot is out in front of your center of gravity when you land. Pretty easy to do during flat sprints over level ground, but very difficult when running hills, which prevents the full extension of the hamstring. Hill sprints generally result in lower ground forces.

16. Don’t neglect eccentric strength training movements.

Sprint-related hamstring strains can often be caused by inadequate training of the eccentric portion of movements. That means you shouldn’t just focus on lifting weights, but also lowering them. For the hamstring, a great strength builder that incorporates both concentric (lifting) and plenty of eccentric (lowering) is the Romanian deadlift.

17. Cool down.

There are many ways to cool down after sprinting. The easiest, and my favorite, is to simply walk followed by a minute or so of Grok squatting. Walk for about 5-10 minutes, then sit in a squat, maybe grabbing your feet and pushing your thighs out with your elbows to get a little stretch going. Biking, rowing, jogging, it all works. Whatever you do, do something.

18. Use a lacrosse ball, foam roller, or other self myofascial release tool at night.

At night after your sprint workout, get the SMR tool of your choice and do some hunting for tender spots. Focus on the glutes, hamstrings, quads, and calves – about a couple minutes per body part. The research is inconsistent, but I’ve always found this stuff really does seem to help break up adhesions and promote improved mobility.

Better yet, get a regular sports massage if you can swing it.

19. Choose the right vehicle for sprinting.

Not everyone is ready for traditional sprinting. Some will never be ready, and that’s okay. Choose your method wisely. Defer to the safer option with less impact if you’re not sure. Consider:

Exercise bikes

Road bikes

Swimming pools

Rowers

Ellipticals

All are viable. All will give you the “sprint effect.”

I don’t mean to overwhelm you guys. Sprinting does work best when performed safely, however, and the rewards are worth the investment. If you don’t want to worry about traditional sprinting, remember that you can always get most of the same health benefits from doing sprints on a bike, rower, and other more forgiving, more user-friendly machinery.

Let’s hear from you. Got any additional tips for safer sprinting? Let me know in the comments!

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

January 28, 2014

Stretching For Strength: 5 Flexibility Standards

This is a guest post from our friend Al Kavadlo of AlKavadlo.com. Al has a new book out Stretching Your Boundaries – Flexibility Training for Extreme Calisthenic Strength that’s well worth a look. You can catch Al at the yet-to-be-officially-announced PrimalCon New York later on this year where he’ll be a guest presenter. Stay tuned for all the details.

This is a guest post from our friend Al Kavadlo of AlKavadlo.com. Al has a new book out Stretching Your Boundaries – Flexibility Training for Extreme Calisthenic Strength that’s well worth a look. You can catch Al at the yet-to-be-officially-announced PrimalCon New York later on this year where he’ll be a guest presenter. Stay tuned for all the details.

If you look around any commercial gym, you’re likely to see a wide variety of activities taking place: strength training, aerobics, simulated bicycle riding, people doing god-knows-what on a vibrating stability platform, and of course, good ol’ stretching. Most gyms even have a designated stretch area. Though you sometimes see serious-minded folk in these rooms, the stretching area in many fitness facilities seems to be primarily for people who want to screw around, be seen at the gym and feel like they accomplished something productive.

For this reason (as well as others), a lot of serious strength training enthusiasts are quick to overlook or even decry flexibility training. Some even argue that static stretching will actually hinder your strength gains and athletic performance. Though I believe stretching is generally more helpful than harmful, there is some truth to these claims. Prolonged static stretching immediately prior to intense dynamic movement can be a recipe for injury. For example, performing ten minutes of static hamstring stretches right before a set of plyometric jump squats may relax your legs too much, temporarily reducing their ability to explosively contract. When you suddenly go into that jump, you may pull a muscle or land poorly.

This does not mean that all static stretching is a waste of time! Everything has its time and place. It’s usually a bad idea to eat right before swimming, but eating is generally pretty important – and so is stretching! In fact, it’s possible that a lack of mobility may be holding you back from reaching your strength potential. Without a full range of motion, fundamental exercises like squats, bridges and even push-ups can’t be fully utilized. Focusing on mobility may ultimately improve your strength in the long run.

Though primitive humans were unlikely to have participated in any sort of formal mobility routine (or formal exercise for that matter), people have mindfully practiced stretching for thousands of years. It’s been a part of various cultures and societies all over the world since the earliest human civilizations. Even animals stretch; since the dawn of movement, stretching has been a part of living.

While a few folks may naturally be tight, the cause of most peoples’ stiffness is simply years of neglect. Your body adapts to your actions (or inactions). If you move often, you will get good at moving, but if you’ve spent most of your life sitting in a chair, chances are your hips, hamstrings, shoulders and upper back have tightened up as a result. It takes a long time for this to happen, and it can take just as long to undo. Many of us could benefit from giving extra time and attention to improving our mobility, as well as making a point to avoid activities that can make matters worse.

Genetics also play an undeniable role in everything related to how our bodies look and move, including our flexibility potential. Some people are just naturally flexible and really don’t need to stretch much at all, but they are the outliers. If you’re one of these lucky few, don’t take it for granted. Mobility tends to be a “use it or lose it” sort of thing and while some folks are naturally more “bendy” than others, your genetics don’t give you an excuse to be inflexible. Though the spectrum of mobility is quite large, we all have the potential to achieve a full, healthy range of motion in all of our joints. There are certain minimum standards that one should aim to meet in order to possess the basic foundation of mobility that is required for healthy, functional movement patterns. Any healthy, able-bodied person should be perform the following:

1. Bend over and touch your toes with your knees locked.

2. Get into a deep squat position with both heels flat on the floor and your calves and hamstrings in contact with one another.

3. Lie flat on your back with your legs straight and lower back in contact with the ground. Reach your arms overhead with both wrists flat on the floor behind you with minimal flexion at the elbows.

4. From a standing position, pick up one leg and place the outside of your ankle on a bench, bar or other object that is just below waist height. Now rotate your hip to touch your knee to the object as well (your shin should be perpendicular to your body.)

5. Reach both arms behind your back – one from above, one from below – and touch the tips of your middle fingers together.

Nowadays, most adults are unlikely to pass all of these requirements, so don’t feel bad if you’ve failed at one or more of these tests. Instead, use these standards as a template to gauge which areas you need to work on. Once you identify your tight areas, you can work toward gradually improving your range of motion.

For more information, check out Al’s latest book, Stretching Your Boundaries – Flexibility Training for Extreme Calisthenic Strength.

January 27, 2014

Dear Mark: Cold Weather Sprint Alternatives, Palm Olein, Podcast Questions, and Dark Circles

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a four-parter. First, I discuss some alternatives to traditional outdoor sprinting for people in cold weather. Just because you can’t go run 100 meter dashes doesn’t mean you can’t get a fantastic sprint workout. Running is unnecessary. Next, I give my take on the suitability of palm olein in the diet. Nutritionally, it seems sound enough, but are there other concerns we should consider? Then, I tell you how you can get your questions answered on a future Primal Blueprint podcast. Last, Carrie gives a reader with chronic dark circles under her eyes some avenues of exploration for figuring out the cause.

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a four-parter. First, I discuss some alternatives to traditional outdoor sprinting for people in cold weather. Just because you can’t go run 100 meter dashes doesn’t mean you can’t get a fantastic sprint workout. Running is unnecessary. Next, I give my take on the suitability of palm olein in the diet. Nutritionally, it seems sound enough, but are there other concerns we should consider? Then, I tell you how you can get your questions answered on a future Primal Blueprint podcast. Last, Carrie gives a reader with chronic dark circles under her eyes some avenues of exploration for figuring out the cause.

Let’s go:

Would jumping up to and down from a 18′ to 24″ platform 10 times for 20 seconds be the equivalent of a 100 yard spring? Man it’s cold outside and I need an alternative.

Thanks,

Jeff

Box jumps are a good exercise, but when you do them correctly they don’t really qualify as sprinting. I see a lot of people doing box jumps as fast as possible, sacrificing form and landing all hunched over with their knees up to their necks just to get to the next rep. You should be landing almost upright with minimal knee flexion so that you can absorb the impact. If you land bent over at the waist, sweaty and heaving, you’re asking for an injury. Doing box jumps – even for time – is great and I’d imagine the benefits approach an all out sprint. Just don’t try to turn it into a sprint by sacrificing form. Go as quickly as you can while maintaining good, clean technique.

There are other, perhaps better indoor options:

A better, maybe the best, indoor sprint alternative would be to grab a cheap used exercise bike off Craigslist. Go for one of the heavy older bikes like a Schwinn Airdyne, because they can take a ton of abuse and they usually go for cheaper than the newer ones. A quick and dirty (but effective) way to do sprints on your average exercise bike is to start slow as a warmup, work up to max RPM with minimal resistance, crank the resistance up as high as it’ll go, and sprint for 20-30 seconds. Drop the resistance back down and pedal slowly and lightly as you recover. Then, do it again.

Sprints on the elliptical are legitimately challenging. If you have access to one of these contraptions, go for it. Use a similar protocol to the exercise bike sprint I described above: start easy, work up to a high RPM, then crank up the resistance.

Indoor pool access? Do swim sprints. Depending on your swimming ability, do either 25 or 50 meter sprints (or even shorter distances). Take plenty of rest in between – swimming is a different beast entirely, a kind of perfect fusion of cardiovascular and strength. At least for the first few sessions, you’ll get a pump all over your body and be fairly sore the next day or two.

Go find a reasonably tall building at least three stories high and go run the stairs. Carry a kettlebell or wear a weighted vest when you run for added intensity. For some reason, I find that weighted stair sprints work better and feel safer than trying to add weight to flat or hill sprints.

If you’ve got a kettlebell or dumbbell handy, swings and snatches are a good option. Not quite the same as a max effort sprint because there’s so much “downtime” between reps, but it’s certainly going to improve your conditioning. Do max swings or max snatches for ten minutes, maybe. Or a modified tabata protocol. 15 seconds on, 10 seconds off for 8-10 cycles is a fun one.

Grab a speedrope and start jumproping as fast you can. Check out this routine on Rosstraining, pretty much the premier source for jumprope conditioning information, for a basic example of what to do.

Classic bodyweight circuits done at high speed with good form are great conditioning (and recent evidence shows that they might be 50% more metabolically demanding than previously thought!). Do ten sets of 5 pullups, 10 pushups, and 15 squats with 20 seconds of rest in between each set. That’ll wear you out. Again, not the same as a sprint but close enough to make it worthwhile.

I was recently introduced to resistance band jumps, and they are “fun.” Attach a resistance band to the ground somehow, or to something very close to ground level. Hold the band in the Zercher or curl position and jump. Do sets of 20 jumps. I got to about quarter squat depth, maybe a bit lower, so I wasn’t quite doing full squat jumps.

Hope you find something that works!

Just as a note to people who brave the freezing weather to run sprints outside: warm up properly! I’ll discuss this further in a future post, but running sprints in cold weather without adequately warming up your legs can cause pulled muscles, torn tendons, and all sorts of unpleasantness.

Is Palm Olein a good fat? The name Olein makes me worry.

Charlene

It’s generally pretty solid (not literally; it’s actually liquid at room temperature), being the more monounsaturated fraction of fractionated palm oil. It’s mostly palmitic (saturated, the same found in your body fat) and oleic (monounsaturated, the same found in olive oil) acid, with about 12% linoleic (PUFA) acid. Let’s see what happens when people eat it:

Replacing sunflower oil (high in omega-6 fat) with a 70-30 mix of sunflower oil and palm olein as the cooking fat increased HDL levels and, perhaps more importantly, made the LDL more resistant to oxidation.

Compared to olive oil, palm olein raises LDL but lowers triglycerides in healthy people. I’d say it’s a wash.

Still, red palm olein (and oil) was superior to refined palm olein due to the presence of carotenoids and other micronutrients. I’m not even sure where you’d buy red palm olein. I suspect that a lot of studies are using “palm oil” and “palm olein” interchangeably.

There is a potential downside to palm olein consumption: the impact palm oil production has on orangutan habitats on the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Basically, natural forests – which the apes have lived in for millennia – are clearcut to make way for oil palms. Although there’s talk of it all being a big conspiracy on the part of seed oil producers, I’m not sure. Orangutans are some of the gentlest, smartest, most fascinating creatures on this planet, and I have reservations about destroying the habitat of a great primate with intelligence similar to a toddler’s. Luckily, African palm oil production does not impact orangutans (or any other great apes), since they don’t live there. It’s also smaller scale with less infringement on existing ecosystems. That doesn’t really solve the palm olein question, since most mass market palm oil comes from Indonesian plantations, while African palm oil produces most of the unrefined, red palm oil that has the most nutritional benefits.

Short answer: if orangutan habitats are a concern for you, palm olein is likely off limits. If you’re only concerned with nutrient quality, palm olein looks to be a fine fat – certainly better than seed oils (most of which are also pretty bad for the environment).

Oh, I almost forgot because this is pretty tangential and I suspect you’re not a baby yourself. Infant formulas using palm olein as the fat source have shown to have negative effects on nutrient absorption. In study after study, infants fed using palm olein have trouble absorbing fat and calcium and end up with lower bone mineral density.

Loving your first few podcasts, Mark. Will you be answering listener questions in future podcasts? If so, how can I submit a question?

Anthony

This one’s easy. Yes, I’ll definitely be answering your questions in future podcasts, and submitting them is easy. Anyone reading can click the button below, and record a question. Be sure to state your first name and tell us where you’re from. Also, please try to keep your questions brief and to the point. It will make sorting through all the submissions easier. Thanks for listening, and stay tuned to The Primal Blueprint Podcast for all (well, as many as I can manage!) your Primal questions answered.

Leave a voicemail

Let’s go to Carrie for the last one…

I have been paleo for 3+ years, typically the better part of a 95/5 rule, and live the lifestyle as well. I get about 7-9 hours of sleep daily, close to 1 gal water, yoga, CrossFit, organic foods, vitamins/minerals, the works. However, I consistently have very dark circles under my eyes. To the point where people (even my fiance!) have asked if I got hit in the eyes. I don’t wear a ton of makeup but usually go for “bare minerals”.

Any suggestions?

Bonnie

Great question! There are several different potential causes. I’ll go through the most likely ones and you can see if anything looks familiar.

Allergies: Known as allergic shiners, dark circles can sometimes be caused by allergies, either environmental (pollen and stuff) or food. A constantly congested nose increases pressure on the blood vessels under the eye and may create a dark circle.

Leaky gut: This goes hand in hand with allergies. Oftentimes you don’t have an out and out food allergy but because your gut is permeable and allowing food proteins entrance into your body your immune system responds as if you were allergic. Exercise can increase leaky gut, too. Normally this is a normal part of training, but it can get out of hand if you’re exercising too much and recovering inadequately. Which takes me to the next one…

Inadequate recovery: CrossFit and yoga require plenty of recovery. CrossFit alone is very demanding. To recover, you need lots of sleep and food. You’re getting “7-9 hours,” but seven hours might not be enough, especially since your name is Bonnie and we women generally need more sleep than men. Sleep inadequacy hits us way harder than the average man, causing more physical and mental disturbances. We also need more sleep to recover from our training, hence “beauty sleep.” Aim for nine hours. If you can’t manage that much sleep, consider dropping a day of CrossFit, or at least replacing it with some walking. Strict paleo also leads to greater satiety on fewer calories, which is good if you’re trying to lose weight but can become problematic when recovering from intense exercise like CrossFit. Support your body with the calories it needs. Ease up a bit and have a few extra helpings of sweet potatoes, maybe some rice, and an extra pat of butter or dollop of coconut oil after your workouts.

Too much water: A gallon of water sounds like way too much to me. As you may know, Mark has always been skeptical of the “eight glasses a day” advice, and you’re getting twice that! I don’t know that hyperhydration would directly cause dark circles under the eyes, but it could impair your recovery and in a roundabout manner worsen the circles. Just drink when thirsty. Your pee should have some color to it – not too dark, not too light.

Thin skin around the eyes: Eye skin is already thin by nature, but certain nutritional deficiencies can manifest as even thinner skin which allow dark circles greater visibility.

Vitamin C – is involved intimately in collagen formation, and one 2009 study found that topical vitamin C solutions applied to the eyelid increased dermal thickness. Make sure you’re also getting vitamin C through your diet. Broccoli and berries are good sources.

Gelatin – Make and eat bone broth or gelatinous cuts of meat like shanks, oxtail, and skin. If that’s not in the cards (it should be, though), powdered gelatin will do, too. Collagen is made of gelatin. I personally love having a cup of broth every other day or so.

Vitamin A – Also involved in collagen formation. Eat plenty of colorful veggies and egg yolks and try to get a serving of beef liver at least once a week. Topical vitamin A creams might help strengthen the skin, too.

If nothing from this list is helping, it might be worth it to get some lab tests from your doctor and check kidney, liver, and thyroid function. Maybe a blood count, too.

Good luck with it!

That’s it for today folks. Keep sending in your questions, and let everyone know what you think in the comment board. Grok on!

Order The Primal Blueprint Starter Kit and Take Control of Your Health Today!

January 26, 2014

Weekend Link Love

PALEOCON is here! Have you registered yet? It’s got 25+ awesome interviews with the top Paleo experts (myself included), behind the scenes at Paleo restaurants, and much more - check it out here.

PALEOCON is here! Have you registered yet? It’s got 25+ awesome interviews with the top Paleo experts (myself included), behind the scenes at Paleo restaurants, and much more - check it out here.

Primal Blueprint Podcast news:

Episode #3 is now available.

All episodes are now up on the Primal Blueprint YouTube channel. You can subscribe to the channel, so you don’t miss an episode.

It’s also now available on Stitcher for those of you that requested this.

If you’ve liked what we’ve done so far, consider leaving a review on iTunes. Thanks!

Research of the Week

A new open-access review explains how manipulating carbohydrate and/or calorie intake can make radiation therapy more effective against tumors.

Got European, Asian, African ancestry? Better hope your gut flora do, too. A recent study finds that H. pylori may only be a pathogen if it did not co-evolve with its host.

Whadya know: converting 10-20% of cropland to prairie grassland can actually reduce erosion and runoff by 90-95%. Sounds familiar, right?

Interesting Blog Posts

When it comes to premies, a mother’s touch has beneficial effects ten years down the line.

Are the hypothyroid-like symptoms people report on low carb due to low carb or low calorie?

Are we underestimating the energetic cost of exercises like pullups, pushups, and squats? Seems we are - by about 50%.

Media, Schmedia

The many stages of eating paleo.

Medicine or mass murder? I guess some mistakes were made. What else have they gotten wrong?

Everything Else

Check out Denise Minger on the Underground Wellness and Prairie Public podcasts.

I’m all for eating more gelatin and reducing your sugar intake, but… wow.

Everyone knows how that one song can catapult you back in time to past memories. Watch it happen here in a patient with severe Alzheimer’s.

Do the brains of elderly people only slow down because they’re processing so much knowledge and wisdom - data, essentially?

Sign up for the En*theos Conference, a series of 22 talks on health, diet, and lifestyle optimization, including one I did with Jonathan Bailor on calorie counting and Primal eating (check out his new book while you’re at it).

This seems like a decent enough training program, but I mostly just liked its name: broga.

The microbial communities living in hunter-gatherer guts look very differently from ours.

Consider tossing a couple bucks toward this documentary about the real ancestral Hawaiian diet.

I’m a big fan of Blade Runner, but I don’t necessarily want to live in that world.

Recipe Corner

Meatloaf with a South African (and Primal) twist: bobotie. Your belly will like it.

You should make this frittata with smoked salmon and green onion sauce.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Jan 27 – Feb 2)

10 Ways to Make Your Workplace Healthier and More Productive – When health is optimized, productivity increases. Who knew?

Why You Should Wear (or Carry) Your Baby (at Least Some of the Time) – The health benefits of carrying and/or wearing your baby – for you and for the kid.

Comment of the Week

Despite being a Sacramento Kings fan, I no longer hate the Lakers and even Kobe.

- Man, after what the Lakers and Kobe have done to you guys, I’m impressed!

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

January 25, 2014

Buttermilk Marinated Pork Chops

Buttermilk is a marinade that pork responds to beautifully. Soak pork chops in buttermilk and the meat will stay juicy and tender, even if you overcook it just a bit. Overcooking a pork chop is easy to do. One minute it’s red and juicy and the next minute it’s tough and chewy. So if you tolerate dairy and hate a dry chop, then buttermilk can be your go-to marinade for pork (it works well for chicken too).

Buttermilk is a marinade that pork responds to beautifully. Soak pork chops in buttermilk and the meat will stay juicy and tender, even if you overcook it just a bit. Overcooking a pork chop is easy to do. One minute it’s red and juicy and the next minute it’s tough and chewy. So if you tolerate dairy and hate a dry chop, then buttermilk can be your go-to marinade for pork (it works well for chicken too).

A buttermilk marinade is especially helpful when cooking thin, boneless chops. You know, the ones that curl up around the edges and usually have the texture of a rubber tire. But even thick succulent pork chops with a flavorful bone holding the meat together can benefit from a soak. It’s some combination of the buttermilk’s mild acidity and calcium content that works the tenderizing magic.

This recipe for buttermilk marinated pork chops uses a plain buttermilk marinade then flavors the meat with a rich caper and parsley sauce. You can also add seasonings to the buttermilk, making the marinade more flavorful. Throw the buttermilk in a blender with garlic, fresh herbs, or your favorite spices.

Servings: 2

Time in the Kitchen: 25 minutes plus 4+ hours to marinate

Ingredients:

2 1-inch (2.5 cm) thick bone-in pork chops

1 cup buttermilk (240 ml)

1 cup chicken stock (240 ml)

2 tablespoons capers, drained (25 g)

2 tablespoons finely chopped parsley (15 ml)

2 tablespoon unsalted butter (30 g)

Salt and Pepper

Instructions:

Soak pork chops in buttermilk for 4 hours or overnight.

Thirty minutes before cooking, drain buttermilk from the chops. Pat the chops dry and season with salt and pepper.

Preheat the oven to 425° F (218 °C).

In an ovenproof skillet over high heat, brown one side of the pork chops for 3 to 4 minutes. Flip the chops and put the skillet in the oven. Roast until the center of each pork chop reads 135 to 140 °F, (57 to 60 °C) about 8 to 10 minutes.

Remove the pork chops from the skillet.

Set the skillet over medium-high heat. Add the stock to the skillet. Boil for five minutes, scraping up any bits of meat on the bottom of the pan. The liquid should reduce by half.

Stir the capers, parsley and butter into the sauce.

Boil 3 minutes more, until the sauce has a deep brown color and syrupy texture. Serve immediately over the pork chops.

Not Sure What to Eat? Get the Primal Blueprint Meal Plan for Shopping Lists and Recipes Delivered Directly to Your Inbox Each Week

January 24, 2014

My Entire Attitude and Outlook on Life Has Been Altered by This Lifestyle

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

I should have been happy, I was sitting around a dinner table at a restaurant enjoying a martini with my step-father and talking with the rest of my family. I reached for another roll (I skipped the butter of course) but before I could even take a bite I was lightheaded, dizzy to the point that I had to leave the table. In the bathroom of the restaurant I almost passed out – I had no idea what was wrong with me. What I didn’t know is that I was bleeding inside, and the amount of bleeding was significant. The next day after my morning throne time I noticed that the entire bowel movement was blood – this repeated three times that morning. After a long night in the hospital and a halfhearted diagnosis of “bleeding ulcer” I was discharged and told to see a specialist. The pain and sickness wasn’t new, neither were the intense headaches, but everything was getting worse.

I should have been happy, I was sitting around a dinner table at a restaurant enjoying a martini with my step-father and talking with the rest of my family. I reached for another roll (I skipped the butter of course) but before I could even take a bite I was lightheaded, dizzy to the point that I had to leave the table. In the bathroom of the restaurant I almost passed out – I had no idea what was wrong with me. What I didn’t know is that I was bleeding inside, and the amount of bleeding was significant. The next day after my morning throne time I noticed that the entire bowel movement was blood – this repeated three times that morning. After a long night in the hospital and a halfhearted diagnosis of “bleeding ulcer” I was discharged and told to see a specialist. The pain and sickness wasn’t new, neither were the intense headaches, but everything was getting worse.

I was at the end of a six year military enlistment and had been unable to pass the physical requirements that year; nobody, including myself could figure out why. About six months before, I was running 15+ miles a week and living in the gym. Now I couldn’t run the required two miles in the allotted time, it wasn’t even close, I had to stop multiple times during the run just to catch my breath before soldiering on for another few hundred yards. I felt such immense shame but it was just the beginning. At the age of 28 my health was collapsing – only a year prior I was in great shape and very active. Below is a photo of my girlfriend (now my wife) and I about a year before I started getting symptoms.

My energy levels, strength and endurance had been collapsing steadily for months – the only other change in my health at the time was intense abdominal pain. After further misdiagnosis my frustration was growing; I couldn’t live the active lifestyle I was enjoying prior to this sickness and the feeling that this was the way I was going to have to live my life was leading me into a deep depression. Weight started to pile on and my physical, emotional and mental health was collapsing. Something had to give.

Finally something did give, my appendix. I woke up in the middle of the night with a sharp pain in a new spot. I knew almost instantly what this was and woke my fiancée (now my lovely wife) and through clenched teeth, told her I needed to go to the ER. At the ER check in I told the nurse what I believed was the problem and then sat to wait for close to an hour. When I was taken in the doctor ran some confirmatory tests and told me what I already knew – appendicitis. Prior to surgery they needed to run blood tests – and this is where it hit the fan. The doctor returned to my room and asked me if I had been “wounded” lately. When I asked for clarification he suggested stab wounds, gun shots or severe lacerations as possible causes for the 7% hematocrit reading he got from my blood samples (normal levels for men are in the 40-50% range).

Amid growing concern I received multiple transfusions over the course of the next several hours before the surgeon went in to remove the pieces of my now ruptured appendix. This entire situation led to several meetings with a new GI specialist. During these meetings over the course of the next few months I asked repeatedly about potential dietary causes to which the only response was – you tested negative for Celiac-Sprue. Eventually we arrived at a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. This diagnosis led to a feeling of bitter relief. I was relieved to “know” what the cause was even if it meant that I was stuck with this horrible condition for the rest of my days. At the very least I knew what had been causing my health to steadily deteriorate for the past 4-5 years.

The next few years were spent trying different ineffective medications and closely monitoring my bleeding induced anemia – on a good day I could get a reading in the 20-25% range, still a long way from normal. My activity levels continued to decline, and the resulting depression, inflammation and sedentary lifestyle were causing my weight to balloon and my attitude continued to deteriorate. The extra work my heart was having to do to pump my anemic blood faster and harder was leading to blood pressure problems which caused the doctors to prescribe additional medications to alleviate this symptom.

It was a discussion with a gluten sensitive coworker that caused me to revisit the idea that this could be dietary. She described her symptoms prior to eliminating gluten and they mirrored my own – I began to do some research into gluten free living and at roughly the same time my wife suggested I look into this “paleo” diet. There seemed to be a wealth of information available about this particular gluten free lifestyle so I set out to build an exceptionally rigid paleo nutrition plan – I would find out for sure one way or another if this was something I could control myself. It was during this time that I discovered MDA and The Primal Blueprint.

The principles set forth in The Primal Blueprint simply made sense to me. I am a biologist by education with a hobbyist’s interest in evolutionary biology. It would seem this lifestyle was tailor made for me – if by name alone! By this point I had been paleo for a couple of weeks and was already seeing promising signs. Sure, weight was coming off but what was more important to me was the way I was feeling.

It took my body about three to four weeks to “feel” adapted. Eating clean like this was causing all sorts of changes for me. I noticed my ability to taste the subtleties in food was becoming stronger. I attribute this to the absence of all the processed garbage which was creating “noise” for my taste buds. Without all the noise I could enjoy the taste of the food that these additives and their accompanying outrageous sugar and sodium levels had been masking all this time. Other physical changes manifested themselves across an entire spectrum of benefits ranging from dry skin on my elbows going away for the first time in years to the holy grail of my quest – absence of abdominal pain. The inflammation and bleeding had stopped. It is something we obviously take for granted, the ability to eat a meal and not double over in pain. After living that way for years, to not feel gutshot every time I eat is incredible, it still defies description.

Energized by these positive developments I began to exercise, slowly at first – just 20 minutes at a time on the treadmill. I began to up this amount as my strength began to return. It was at this point that I knew I had made the first correct decision about my health that anybody had made in years. From this point on, every small change I made to get myself more in-line with a Primal lifestyle was yielding benefits and they were all complimenting each other. My exercise routine changed from 20 minutes on the treadmill to 30 minutes of outside running, to running longer distances 4+ times a week (bordering on chronic cardio) to my current routine of HIIT days alternating with heavy lift days with shorter runs, swims and hikes thrown in for good measure. I was weighing myself every day, but more to develop an understanding of my body than to monitor weight loss – which was occurring at a steady pace.

My entire attitude and outlook on life has been altered by this lifestyle. The gift of being able to challenge myself physically has been returned to me, and it isn’t a gift that I intend to squander. I’ve developed an addiction to obstacle racing! Here is a picture of me crossing the finish line at the 2013 Spartan Beast world championship race in Killington Vt. For perspective – only 8 months prior I was 115 lbs heavier and so anemic I couldn’t ascend a flight of stairs – my heart would pound so hard that it shook my torso. This race was 12-14 miles long up and down the mountain all day with 40+ obstacles.

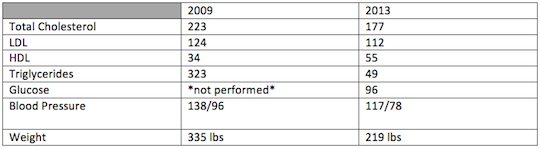

It is almost a year to the day since my first steps down this path, although to be perfectly honest my weight hasn’t fluctuated in months. I just had to wait to get my physical results before I submitted this, I wanted the data for that side by side comparison.

It is easy to focus on what I lost during a period of change like this (115 lbs, an array of worthless medications, and frequent headaches) but it is far more valuable to focus on what I gained – energy, confidence, health, speed, strength, vitality and youth; like a phoenix born from the ashes of my prior life.

Before

After

Sitting down to write this story brought in to stark focus exactly how long and challenging this period of my life has been. Undiagnosed for years, misdiagnosed for even longer – I lost nearly a decade of my most vital years (28-37) because I wasn’t confident enough to make my own decisions about my health. No more, my vitality is mine to control. I know this lifestyle has its fair share of critics and doubters and while I have a hefty repertoire of arguments, counterarguments and even my own openly expressed data sets (see above) I don’t engage in debate. If there is anything this experience taught me it is that there is nobody with a bigger stake in your well-being than yourself, and it is up to you to not only make the change, but to commit to it. It isn’t easy – but it is simple.

It is wonderful to know, that when people do finally reach the point where they know a change is required – there is a wealth of information and a supportive community here at MDA waiting to help them through the metamorphosis. This is something I hope to provide as well with my own upcoming blog dedicated to Primal living. Thanks for reading!

Like This Blog Post? Dig Deeper with Primal Blueprint Books and Learn How You Can Reprogram Your Genes to Become Leaner, Stronger and Healthier

January 23, 2014

What Is Your Inner Athlete?

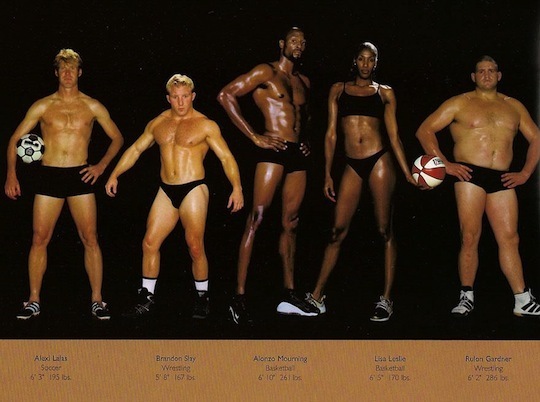

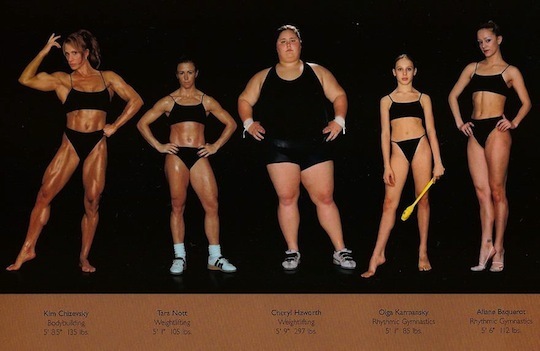

Visualization time… Take a moment and picture a world class athlete in your mind. What image is coming? If you’re like most people, you’re probably visualizing a tall, lean, muscle-bound (or at least very muscular) man or woman, the epitome of brawny human form. On the flip side of this exercise, of course, that means you’re likely not thinking of anyone who’s short, stocky, slight, overweight, exceptionally tall, etc. And yet athletes, even world class athletes, come in literally all shapes and sizes. You may have seen these pics (a few of which are embedded below) making the rounds recently (or remember them when they were first published by Howard Schatz about twelve years ago or so). On the surface, the idea of body “variety” isn’t all that novel of an observation, but I’m still struck when I look at these photos.

Visualization time… Take a moment and picture a world class athlete in your mind. What image is coming? If you’re like most people, you’re probably visualizing a tall, lean, muscle-bound (or at least very muscular) man or woman, the epitome of brawny human form. On the flip side of this exercise, of course, that means you’re likely not thinking of anyone who’s short, stocky, slight, overweight, exceptionally tall, etc. And yet athletes, even world class athletes, come in literally all shapes and sizes. You may have seen these pics (a few of which are embedded below) making the rounds recently (or remember them when they were first published by Howard Schatz about twelve years ago or so). On the surface, the idea of body “variety” isn’t all that novel of an observation, but I’m still struck when I look at these photos.

The pictures themselves drive the point home in a way that the general concept can’t touch. The broad diversity and profound individuality of body shapes, forms, and musculature jumps off the page, and yet all of these people are world class athletes. (Inherent to this message, too, is the diversity of sport itself as physical endeavor that uniquely cultivates the body). It’s fascinating, I think, to see what the human body is capable of – not some “perfect,” standardized, conventionally “ideal” physique but a real body with individual uniqueness and stunning utility. In this case, it’s a wide spectrum of body types. When you look at these folks, it makes the fluffy enhanced images on magazine covers look that much more ridiculous.

It also makes me think how many people assume they aren’t “athlete material” because they don’t believe they have the body for it – or so they’ve been told (directly or indirectly). Sure, most of us will never be professional athletes. Most of us are not and never will be 7-foot tall basketball player material. But the fact remains: if you have a body, you’re an athlete. The identity and intention dwell in your genes themselves. Whether you’re a 5 foot tall rhythmic gymnast waiting to happen or a lanky dude who’s built for covering long distances quickly, there’s a niche for you. You embody in some way the athletic mission of our species.

Maybe you haven’t figured out what that embodiment is yet. It’s always eluded you, or you always shunned the prospect so entirely that you struggle against identifying with it at all. (What too often passes for physical education in this country can do this to people – as much of a shame and an irony as it is.) We tell ourselves a whole lot of self-limiting stories, and this arena might be prime territory for that unfortunate tendency. Let me say point blank: find your athletic embodiment in your lifetime. You won’t be sorry you did and will likely always wonder if you don’t.

With that in mind, find your niche. Find your sport. Figure out – or flat out decide – what kind of athlete you are or want to be. There’s no need to play perfectionist and opt out because you can’t be Lebron James or Lindsey Vonn. We don’t let ourselves play defeatist that way in our careers, hobbies or social lives. (Right?) Why on earth would we hold ourselves back from enjoying cultivating our bodies to their full and creative potential because someone on the T.V. can do a skill better (that they get paid millions of dollars a year to do of course)? It should be about vitality and fun. It’s about self-actualization and the unique thrill of it.

When someone tells me they’re not an athlete “type,” I often tell them they haven’t found the right sport for their inner athlete. Maybe they bristle against the athletic “type casting” their build suggests to people, or (again) maybe they rejected the athletic potential of their bodies period. Maybe they shrug off the possibility now because of age. (Another lie to discard…) The fact is, your body is so much more than your build – or your years.

Here’s a novel thought perhaps – an extension of what those photographs suggest. Do what you want to do. Do you think you have to be lean and willowy to be a yoga guru. No, you have to be committed and passionate to be a yoga guru. And guess what? You have to be committed and passionate to be a soccer player or a wrestler or a dancer or a body builder. The same holds for every activity and sport. If you can show up with a good attitude and consistent determination, you’ll be able to enjoy yourself and develop within a sport. It might not be the “natural” fit for your body, but it can be the best, most fulfilling choice for your personality. When we do what we love for exercise, it doesn’t feel like work. How much more ideal can it get?

Primal exercise is a flexible set of general principles that mirror the basic patterns of our ancestors’ exertion – period. How you fulfill these in your modern life is entirely your choice. Be whatever Primal athlete makes sense to you and you alone. By all means, make it as fun as possible. Your fitness should enhance more than your physical health but be a meaningful, self-affirming, self-exploratory part of your life. It’s the best of all Primal worlds.

Thanks for reading, everyone. Let me know your thoughts on the photo collection and the journey you’ve taken to find or develop your inner athlete.

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

January 22, 2014

15 Reasons to Sprint More This Year

A couple weeks ago, I gave you 17 reasons why you should walk more this year, citing dozens of studies in my attempt to convince you that walking is a healthy, effective endeavor for everyone and anyone. But it’s not the only thing you should be doing if you can help it. If you have the ability, I strongly believe that you should also be sprinting – at least (and maybe at most) once a week. The effects of regular sprinting on your health, your body composition, your fitness, your strength, and your susceptibility to disease are so impressive that it’d be foolish not to. I’ve said it before and even enshrined it in the Primal Laws to accentuate its importance, but here it is again: you should sprint more this year.

A couple weeks ago, I gave you 17 reasons why you should walk more this year, citing dozens of studies in my attempt to convince you that walking is a healthy, effective endeavor for everyone and anyone. But it’s not the only thing you should be doing if you can help it. If you have the ability, I strongly believe that you should also be sprinting – at least (and maybe at most) once a week. The effects of regular sprinting on your health, your body composition, your fitness, your strength, and your susceptibility to disease are so impressive that it’d be foolish not to. I’ve said it before and even enshrined it in the Primal Laws to accentuate its importance, but here it is again: you should sprint more this year.

Why, though? Let’s hear some specific, science-based reasons to get up and move as fast as possible:

It preferentially burns body fat.

Weight loss isn’t just about eliminating any old kind of body mass. It’s about losing body fat while preserving or even gaining muscle and bone. Sprinting appears to be excellent at eliminating body fat without the negative impact on muscle mass commonly seen with excessive endurance training. A recent study found that a single sprint session can increase post-exercise fat oxidation by 75%. Not that this is a surprise, but even in young adults with an intellectual disability, sprinting improves body composition by reducing body fat.

It’s anabolic (that means it can increase muscle mass and strength).

An acute bout of sprinting increased dihydrotestosterone in healthy young men, while in overweight young men, a sprinting program increased lean mass in the legs and trunk. (In one study, men and women did three 30 second all-out sprint intervals on the stationary bike with 20 minutes of rest in between each sprint. Muscle biopsies were taken from their quads and analyzed for markers of protein synthesis – how muscle gets laid down.

It’s even more anabolic in women than men.

Yeah, yeah, you don’t wanna “get all big and bulky.” I know. But ladies, it won’t happen to you unless you’re somehow using an exogenous source of anabolic hormones to reach supraphysiological levels that you’d otherwise never reach naturally. More lean mass for you means more “tone,” less body fat, and more strength. In the previously mentioned study, female protein synthesis was up by 222%, male by 43%.

It makes you better at accessing body fat during other types of exercise.

Sprinting primes the substrate utilization pump, so to speak, for other activities. In one study, a two week program of cycling sprint interval training increased the rate of (body) fat oxidation (and decreased the rate of glycogen utilization) during subsequent lower intensity sessions in women.

It builds new mitochondria.

The basic function of our mitochondria is to extract energy from nutrients to produce ATP, the standard energy currency of our body. More mitochondria, more power available to our brain and our body, more fuel burned, more energy produced. It’s a generally good idea to have healthy, numerous mitochondria, and scientists are constantly trying to figure out how to preserve or increase their numbers because so many degenerative diseases are characterized by malfunctioning mitochondria. Well, sprinting is one way to make more. A single bout of 4×30 second all-out cycling sprints activated mitochondrial biogenesis in the skeletal muscle of human subjects in one study. Shorter sprints work, too. In fact, a program consisting of three sets of 5 4-second treadmill sprints with 20 seconds of rest in between each sprint, done three times per week for four weeks up-regulated molecular signaling associated with mitochondrial biogenesis.

It even works if you go slowly.

Allow me to expand on that statement: it even works if you go slowly because you’re pushing a heavy weighted sled. If that doesn’t sound like an advantage to you, consider someone who can’t run a flat-out sprint on a flat surface because of prior joint injuries. Pushing a heavy sled (or a car) slows the person down, thus reducing the joint impact, without making the exercise any less intense. Research shows that heavy sled pushing is extremely effective.

It’s more efficient than endurance training.

Obviously, sprint training takes less time to do than endurance training. But did you know it’s just as effective in many regards in a fraction of the time? Sprinting three times a week (4-6 times per session) was just as good as spending five days a week cycling for 40-60 minutes at improving whole body insulin sensitivity, arterial elasticity, and muscle microvascular density.

It takes way less time than you think.

A 30 second all out sprint is “just” 30 seconds, but it’s a hellish 30 seconds. A single hill sprint isn’t too bad, nor are two or three, but when you hit the eight, nine, ten sprint range, it gets rough. You will feel it after. Still better than slogging it out for an hour and half, mind you. I get the sense that most people think for any training to be effective, it has to hurt – even if only for twenty seconds or so. Actually, when you sprint, extremely brief intervals work very well. In this study, for example, subjects cycle-sprinted for a mere 5 seconds at a time and actively rested for 55 seconds in between sprints (that’s where you’re just casually pedaling on the cycle, equivalent to walking after a running sprint); that was enough to increase the maximum amount of work they were able to perform in 30 seconds. Instead of walking down the beach, I’ll sometimes traverse it in ultra-short sprint intervals: sprint for 5 seconds, walk for 20, sprint for 5, and so on. I don’t really even get winded doing this. Or if there’s a short (<10 meters) but steep hill, I’ll sprint up it, walk down, and repeat about a dozen times.

It’s a good excuse to get to the beach.

Doing your sprints on sand makes them more effective (and harder). A recent study found that sprint interval training sessions performed on sand resulted in better performances in subsequent training bouts, beating out grass as a training surface. I’ve also found that beach sprints enable post-training water plunges, regardless of water temperature.

It works for overweight people.

Sprinting may be the most daunting exercise of all for overweight people. How can moving that fast be safe or healthy? Well, there’s evidence that sprinting is extremely effective in this population. In a 2012 study (PDF), a group of overweight female students followed a 12-week sprint program consisting of 8-16 200 meter sprints done three days a week. After the program, body fat and body weight had gone down significantly, insulin sensitivity had improved by 100%, and V02max had increased. Another study, this time in overweight/obese men, found that a sprinting program (this time on a cycle) increased fat burning at rest while decreasing carb burning at rest – exactly what an overweight person needs to achieve to start burning body fat and become fat-adapted. The men also lost significant amounts of waist and hip fat.

It works for elderly people.

Oldsters needn’t stick with 2.5 pound dumbbells and “stretching workouts.” They can derive great benefit from high intensity interval training. Sure, they might go a bit slower than the rest of us. They might do better on exercise bikes than tracks. But they can still do it.

It improves glucose control and insulin sensitivity.

Diabetics, take heed. Sprint training improves insulin sensitivity, improves hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, and lowers the postprandial glucose response in diabetics. You gotta start doing it if you’re not already.

It lowers high blood pressure.

Okay, while you’re sprinting, you’ll probably have sky-high blood pressure. That’s okay, that’s just an acute spike – it happens with any type of exercise. Overall, sprint training appears to have the most potential of any exercise modality for the long term resolution of hypertension.

It’s safe for people with heart disease.

Heart disease patients interested in improving their cardiovascular health are often told to start jogging or something similarly unpleasant. Why not sprinting? We already know it’s more effective against heart disease risk factors, and high intensity interval training has been shown to be safe in heart disease patients, particularly when they keep the intensity high and the duration low (15 seconds or thereabouts). Check with your doctor first, of course, just to be safe (but prepare yourself for the “jogging” lecture).

It comes in many forms.

When people hear “sprinting,” they think of 100 meter flat sprints on the track. Those are effective, sure, but they’re not the only way you can reap the benefits of sprint training. You can run hills (easier on the joints and more intense overall). You can cycle (easier on the joints and proven to work in dozens of sprinting studies). You can do it in the pool (either running in water or swimming). You can row or use the elliptical. Heck, if you loathe “cardio” of any kind you can probably get sprint-esque effects from lifting weights really quickly (think doing a set of 20 back squats or something similar). Upper body interval training works for general fitness in elderly hip replacement patients, for example. There’s something for everyone, which means there are almost no excuses not to sprint.

That’s what I’ve got. There are probably more reasons to sprint, but I think the 15 I discussed are a good start. So get to it!

What about you guys? Why do you sprint? What are you hoping to get out of it? What have you already gotten out of it? Let us know in the comment section!

Get the 7-Day Course on the Primal Blueprint Fundamentals for Lifelong Health Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

January 21, 2014

Are Parasites Primal?

The environment of ages past has shaped who we are today, even (or especially) the difficult, unpleasant stuff – this is the foundation of ancestral health. Take exercise. Early man’s daily life was one of frequent, constant activity interspersed with infrequent bouts of intense activity. Hard exercise is, well, hard and physically unpleasant in the moment, and constant low level activity is often untenable given modern schedules, but both make us stronger, healthier, and ultimately happier. Intermittent fasting, while difficult, can be beneficial when artificially imposed today because our genome evolved under periods of nutritional stress where food was scarce. Going without food from time to time was expected; it was our genome’s evolutionary backdrop. Our bodies evolved with these hardships as assumed and inevitable aspects of the environment. Our modern bodies function best when exposed to these hardships.

The environment of ages past has shaped who we are today, even (or especially) the difficult, unpleasant stuff – this is the foundation of ancestral health. Take exercise. Early man’s daily life was one of frequent, constant activity interspersed with infrequent bouts of intense activity. Hard exercise is, well, hard and physically unpleasant in the moment, and constant low level activity is often untenable given modern schedules, but both make us stronger, healthier, and ultimately happier. Intermittent fasting, while difficult, can be beneficial when artificially imposed today because our genome evolved under periods of nutritional stress where food was scarce. Going without food from time to time was expected; it was our genome’s evolutionary backdrop. Our bodies evolved with these hardships as assumed and inevitable aspects of the environment. Our modern bodies function best when exposed to these hardships.

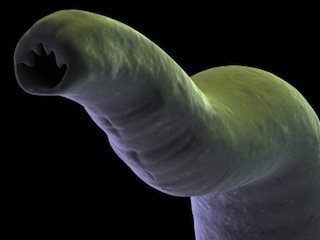

What about another almost unavoidable aspect of the ancestral environment – parasites? Do our bodies expect and function best with a few (dozen) worms along for the ride? You know about gut flora’s effect on our immune response and overall health, but does the fact that our immune systems evolved with the presence of various helminthic worms also have implications for our health?

A growing number of researchers think it’s likely. They posit the “Old Friends Hypothesis,” which suggests that helminthic worms and other parasites commonly assumed to be wholly pathogenic are actually “old friends” that can provide a steady, low-level anti-inflammatory buffer that reduces the incidence of autoimmune diseases like celiac, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, and Crohn’s disease. Populations with high parasite loads tend to display a remarkable absence of autoimmune disease as well as distinctive genetic markers that bias them toward higher baseline inflammation levels that are only held back by the presence of worms. Many of the alleles associated with having parasites are also associated with celiac, multiple sclerosis, colitis, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis, which suggests parasite/host co-evolution. In the presence of worms, maybe those alleles become harmless.

If you’re wondering why worms would ever be a “good thing,” you have to realize that helminthic worms are stubborn. They get lodged in there. They can’t really be removed by our immune system because the inflammatory response required to do so would damage the host (that’s us) more than keeping the thing around would damage the host. In turn, the worm doesn’t want to overstay its welcome by taking too much from the host and killing it. So, the host adapts to its inextricable bedfellow, while the bedfellow adapts to its host by modulating the host’s inflammatory response. And in time, it becomes reliant on the parasite, and the parasite becomes an external fixture of our immune system. It’s not really part of us, but we treat it like it is because it’s been there for so long over so many generations that we can’t function without it. We’re used to the inflammatory buffer. Humans have encountered many different species of helminth, and most, if not all of them modulate immune function in unique ways.

And when it’s no longer there, when we move to cities and stop having parasite-enriched dirt under our fingernails, when we enact widespread sanitation measures and clean up our water and throw our trash away in nice neat bins that get cleaned every week, there are unforeseen consequences. Even though infectious disease rates and deaths from infectious disease drop, and more infants make it through to adulthood, there’s no free lunch. As long as the old friends are there to buffer against the elevated inflammation, autoimmune disease is relatively absent. When the old friends are withdrawn (like through anti-helminthic therapy), autoimmune disease and allergies increase.

So, what should we do? Go spelunking in a rural Indonesian porta-potty? Take shots of Ganges River water? French kiss a pig? You’d actually be surprised. One guy cured his asthma by walking barefoot through the latrines of Cameroon. While that may be the “most Primal” way to do things, it’s not advised. As mentioned earlier, there are a lot of parasites out there whose effects we don’t quite understand and there are plenty whose effects we know to be pathogenic. Inoculating yourself with random wild helminths could cure your allergies or it could give you tapeworm (or both, I suppose).

Trials have been completed and more trials are underway, and the results are extremely promising thus far. Just so you know I’m not pulling your legs, let’s go through a few of them:

Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s, colitis): Epidemiology suggests a protective effect of childhood helminth exposure on IBD risk, but what about controlled trials in adults? In one case, patients with Crohn’s disease who were exposed to hookworms had less reactivity to the parasites than controls without Crohn’s; the hookworms were less of an “immune insult,” and presumably more of an aid.

Allergies: A number of helminth species down-regulate allergic responses to otherwise harmless antigens by modulating the immune system, but some species appear to have the opposite effect (common roundworm infection for example has been associated with asthma and shrimp allergy). The children of mothers given antihelminthic drugs during pregnancy tend to have more infant eczema, which may presage future allergies.

Asthma: One study found that hookworm infection mildly improved airway responsiveness in asthmatic patients, with no effect on other parameters of asthma, but the dose was small – just 10 hookworm larvae. The most common dosage for hookworm therapy is around 35 larvae, so it’s possible the dosage was just too low.

Multiple sclerosis: Via a retinoic acid-dependent pathway (eat your vitamin A!), helminths have been shown to modulate the immune response in multiple sclerosis patients. Those who were infected had better outcomes than those who were not.

Celiac disease: Human hookworm infection suppresses the inflammatory immune response to gluten normally seen in patients with celiac. It even improves mucosal immunity and may help heal celiac patients, not just suppress their response. However, another study using an oral wheat challenge (equivalent to 16 grams of gluten a day, which is a fairly high dose) in celiacs found no benefit to hookworm infection.

Helminths may also be a potential therapy for atherosclerosis, joint inflammation, autism, and type 1 diabetes (PDF, if you catch it before it develops). They seem to have a favorable impact on gut microbes, restoring the mucosal lining and rebalancing the floral communities to be less inflammatory in macaques with diarrhea, so there’s probably a role for general immune and digestive health as well.

Okay, that’s cool and all, but we’re still dealing with worms wriggling around in your gut. There’s little else more unnerving and repulsive than the thought of hookworms setting up shop in and gnawing on your small intestinal lining. And there are dangers to helminths, particularly in developing countries where people tend to be malnourished, absent access to medical care, and carry large parasite loads. Most intestinal worms consume blood. Get enough of them lodged in there and you can end up with anemia, malnutrition, growth deficiencies – especially if you’re a young child.

But anemia only occurs when people are getting reinfected due to frequent contact with parasite-laden fecal matter in the environment and the parasite loads get out of hand. In a controlled, clinical setting where infection is carefully curated (to prevent reinfection) and the patients have access to plenty of nutritious food and medical care, it’s far safer. As it stands now, helminths must satisify certain safety and efficacy parameters before being considered for therapy. Qualifying worms:

should not have the potential to cause disease in man at therapeutic doses

should not be able to reproduce in a host, thus allowing control of dose

should not be a potential vector for other parasites, viruses, or bacteria

should not be easily transmissible from the host to other people

should be compatible with a patient’s existing medication

should have a significant period of residence in the host

must be easily eradicated from the host, if required

The majority of clinical trials of helminthic therapy have a relative paucity of adverse reactions. Diarrhea, stomach upset, and skin irritation are the most common side effects, but usually only for the first few days and not in everyone. If it were to get out of hand, anti-parasite drugs are effective, fast-acting, and safe.

Grok definitely had parasites, but he probably wasn’t loaded to the gills, instead carrying just a few select species. The most prevalent helminth among a group like the San Bushmen, for example, is necator americanus, the human hookworm (PDF) species thought to have the most therapeutic potential. The largest parasite loads are seen in agricultural communities whose inhabitants have close, constant contact with animals (and their waste) and each other (and their waste). Hunter-gatherers had (and have) higher parasite loads than modern industrialized populations, but not as high as agriculturalists because they were steadily on the move and switched locations when parasites and parasite-laden feces became a problem. When hunter-gatherers hunker down and become sedentary, parasite infections skyrocket.

Pig whipworm is a current favorite among helminth enthusiasts, since it’s non-native to humans, it doesn’t survive for long and it doesn’t reproduce in the human host. This prevents overpopulation, but it also necessitates frequent re-dosing of eggs to maintain treatment, which gets very expensive. Treatment with pig whipworm can easily hit thousands of dollars per month.

Necator americanus, the human hookworm, appears to have the most potential against autoimmune diseases. It’s native to humans, cost-effective (lives for 3-5 years inside the host after a one-time infection), and sheds its eggs in the feces. As long as your feces are going into a toilet and not your backyard, there’s no chance of increasing your parasite load from reinfection.

This information isn’t easily actionable, not like information about exercise or diet or sleep is actionable. First of all, worms are scary. Way scarier than trying squats or eating liver or setting a strict bedtime. Parasites can be problematic, and many of us really have no way of safely inoculating ourselves. Which ones? Where do we find them? What if we mess up and get something really pathogenic? After all, the people who do carry parasite burdens generally don’t go about looking for them; they just pick them up through incidental, everyday contact. Clinical trials are underway, and I’d imagine the FDA will be getting involved soon enough.

If you are interested in helminthic therapy, you’ll probably have to handle things yourself. Here are a few ways to learn more, but please be advised that I don’t recommend, exactly, you do any of the following, and suggest you consult with a doctor before proceeding:

You could join the helminthic therapy group on Facebook and/or the Yahoo mailing list, where you’ll gain access to plenty of likeminded souls with extensive personal experience with worm therapy, as well as helpful resources, links, and advice. Brave souls are even doing some clandestine unregulated worm trading.

Nearly everyone but US residents can have worms shipped to them by Autoimmune Therapies.

US residents will have to truck it down to Worm Therapy, which operates out of Tijuana, Mexico, just across the border from San Diego. They offer hookworm and whipworm. Another option is to contact Coronado Biosciences, a company that’s currently running US trials for pig whipworm in Crohn’s disease in a number of cities across the country.

Also, mention it to your physician! He or she may balk or cringe or shower you with condescension, but it’s a good idea to be under medical supervision when infecting oneself with helminthic worms. And hey, if it works – and there’s a good chance it might – you very well could change an influential mind.

Is there a role for helminths in general health and immunity? Probably. But I’d wait for more research to take place before having nematode eggs and bacon for breakfast. If you’re suffering from any of the diseases shown to be modulated or improved by helminthic therapy, however, it might be worth researching.

What about you guys? Grossed out? Intrigued? About to book a trip to Cameroon? Let’s hear your reactions in the comment section!

Order The Primal Blueprint Starter Kit and Take Control of Your Health Today!

January 20, 2014

Dear Mark: Salmon and Mercury, Fruit and Sugar, plus Seniors Gaining Muscle