Mark Sisson's Blog, page 283

October 22, 2014

Are Elite Athletes Inadvertently Training Like Grok?

Modern elite athletes have different goals than our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Their training loads are higher and their physical activity is contrived and somewhat artificial. But for the most part, elite athletes are working with the same metabolic and neuromuscular machinery as Grok. The activities and movement patterns that benefited and shaped the evolution and performance of our hunter-gatherer ancestors should thus prove useful for contemporary humans seeking optimal physical performance. According to a recent paper (PDF), many top athletes have settled upon the hunter-gatherer fitness modality as optimal for performance. Even highly specialized athletes without much room in their routine for generalizing – like marathon runners who have to be able to log insane mileage at high intensities above all else – are incorporating aspects of paleolithic fitness to improve their training. These athletes and their coaches aren’t combing the anthropological records to devise their programs; they’re inadvertently arriving at similar conclusions because that’s where the latest exercise science points.

Modern elite athletes have different goals than our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Their training loads are higher and their physical activity is contrived and somewhat artificial. But for the most part, elite athletes are working with the same metabolic and neuromuscular machinery as Grok. The activities and movement patterns that benefited and shaped the evolution and performance of our hunter-gatherer ancestors should thus prove useful for contemporary humans seeking optimal physical performance. According to a recent paper (PDF), many top athletes have settled upon the hunter-gatherer fitness modality as optimal for performance. Even highly specialized athletes without much room in their routine for generalizing – like marathon runners who have to be able to log insane mileage at high intensities above all else – are incorporating aspects of paleolithic fitness to improve their training. These athletes and their coaches aren’t combing the anthropological records to devise their programs; they’re inadvertently arriving at similar conclusions because that’s where the latest exercise science points.

What movement and training patterns am I talking about, exactly?

Shift away from “one size fits all” periodization.

Grok didn’t follow a predetermined workout routine or fitness program. Instead, ancient humans autoregulated their physical activity according to energy availability and expenditure. If yesterday was a heavy day of hunting, butchering, and carrying the food back to camp, and food was plentiful for the next few days, what would be the point of going out again and expending more energy? Heck, he might take a deload week if he could get away with it. The only reason we train hard on consecutive days is because the program says to do it. Because we think we “have” to workout. If we listened to our bodies, like hunter-gatherer ancestors had to, we’d take a lot more rest days and we’d actually get more out of workouts.

Unfortunately, “one size fits all” periodization makes for easy programming. Instead of coming up with personalized routines for each athlete, you hand everyone the same program. Sometimes this works. Total novices respond well to any kind of physical activity, and they’re coming from a similar starting position, so a general program will work for them. That’s one reason why beginning strength routines like Starting Strength can get anyone starting from scratch fairly strong fairly reliably. But to optimize performance and training adaptations, you’ll have greater success with dynamic programming that heeds the athlete’s dynamic needs.

These days, the advent of heart rate variability tracking is allowing modern elite athletes to monitor the state of their autonomic nervous system activity, avoid overtraining, and adjust their training accordingly – and they’re getting better results than athletes who follow predetermined training plans that fail to account for the day-to-day fluctuations in rest/recovery balance.

Growth of polarized training.

You know how I’ve always said make your long, easy workouts longer and easier and your hard workouts shorter and harder? The foundation of Primal Blueprint Fitness is lots (and I mean lots) of low level activity. Easy walks, hikes, cycling, even jogging (depending on your base fitness level) all qualify, as long as you avoid dipping into the medium-high intensity zone for too long and too frequently. We punctuate this slow, frequent movement with infrequent bouts of extremely high intensity – strength training and sprinting. From the available anthropological and ethnographic evidence, this seems to characterize the likeliest activity patterns of paleolithic humans. Humans were obligate walkers, with modern foragers putting in an average of 6 to 16 kilometers a day (PDF). And when they weren’t walking, they usually still had to constantly move in order to perform the day-to-day tasks required for survival. Bursts of intensity – lugging a heavy carcass, throwing a spear, climbing a tree to grab honey, sprinting after something – were relatively infrequent but no less crucial in shaping our fitness.

Modern endurance athletes are beginning to incorporate something called polarized training, which is characterized by spending 80% of training volume in the low intensity zone and 20% in the high intensity zone – extremely similar to the projected patterns of hunter gatherers. Comparisons between polarized training and more conventional threshold training (with 57% of volume as low intensity, 43% as medium intensity, and none at high intensity) in trained cyclists found that polarized training resulted in greater systemic performance adaptations. And in runners, cyclists, triathletes, and cross-country skiers, polarized training resulted in greater endurance performance adaptations than threshold training, high intensity training, and high volume training. At first glance, this seems paradoxical because most endurance events occur in that medium-high, lactate metabolism zone that polarized training appears to neglect and threshold training specifically targets. But the results speak for themselves; training the extremes (both high and low) can improve performance across the spectrum of intensities.

“Train low, race high.”

Paleolithic hunter-gatherers couldn’t hop on down to the grocery store for food. They had to expend energy to obtain energy – they had to “exercise” – and they often did it without fully-stocked muscle glycogen stores. This is familiar territory for any regular reader of this blog, but rather than focus on how this discrepancy might explain modern conditions like obesity and diabetes, I’m more interested in how it affected our adaptation to physical training. When you train, or hunt, or forage in a glycogen depleted state, you augment the normal adaptations to exercise. You get better at burning fat for energy and conserving muscle glycogen during physical activity. You increase mitochondrial biogenesis.

Modern athletes have taken this concept and run with it, creating the “train low, race high” modality. From cyclists to marathoners to triathletes, endurance athletes have begun including low-glycogen training sessions in order to improve their fat burning capacity and glycogen conservation. Then, when it’s race day, you load up on glucose, fill your muscles with glycogen, and enjoy the benefits of fat adaptation. You can go longer without dipping too much into your precious glycogen, and by the time the last leg of the race rolls around, you have more glycogen left over than the next guy who’s bonking. The latest exercise science agrees: athletes should incorporate “train low” days in order to take advantage of this ancestral metabolic pathway.

Importance of strength training for endurance athletes.

Back when I was competing, endurance guys dabbled in strength training, but a lot of it was for show and primarily focused on the upper body. A belief that training the legs with heavy squats or deadlifts would only tire you out, slow you down, or run the risk of injury ran through the community and so people neglected their lower bodies. Plus, after the kind of heavy, chronic sessions we’d frequently put in, the last thing anyone wanted to do was lift something with their legs.

While strength training myths persist in the endurance world, the tide is changing. The research has confirmed what Grok “knew” eons ago: everyone can benefit from strength training, even, or especially, endurance athletes. Concurrent strength and endurance training improves running economy, peak velocity, force development, and overall performance in endurance athletes of all stripes. There’s even evidence (PDF) that an endurance session acutely potentiates a subsequent strength session, as if our bodies expect us to lift and manipulate heavy things (carcasses?) after running (or chasing/hunting something down?). Wild.

I don’t know about you guys, but I’d say this is all a very strong sign that we’re on the right track with all this “heed the lessons of the past and run them through the prism of modern scientific research” stuff. Wouldn’t you?

Thanks for reading, everyone. If you have any questions, comments, or concerns about today’s post, let’s hear it in the comment section below!

Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

You CAN Lose Weight and Get Healthy. Find Out How>>

October 21, 2014

Are Video Games Good or Bad for Us?

Non-gamers tend to take a dim view of video games and their fans, assuming they’re all a bunch of sweaty man-children clutching liter bottles of Mountain Dew between Cheeto-dusted fingers and screaming racist obscenities that diffuse, muffled, through thick neckbeard thatches into their headsets at online opponents. And a few weeks ago, even I referenced the stereotypical World of Warcraft addict’s set-up of pee bottles and poop buckets. But the latest statistics indicate that the popular stereotype isn’t very representative of most gamers. In fact, if you’re an American, you’re more likely to be a gamer than not:

Non-gamers tend to take a dim view of video games and their fans, assuming they’re all a bunch of sweaty man-children clutching liter bottles of Mountain Dew between Cheeto-dusted fingers and screaming racist obscenities that diffuse, muffled, through thick neckbeard thatches into their headsets at online opponents. And a few weeks ago, even I referenced the stereotypical World of Warcraft addict’s set-up of pee bottles and poop buckets. But the latest statistics indicate that the popular stereotype isn’t very representative of most gamers. In fact, if you’re an American, you’re more likely to be a gamer than not:

In the Unites States, the average gamer is 30 (PDF); in the UK, it’s 35. As the kids who grew up playing Nintendo and Sega Genesis get all growns-up and continue playing, the average age will only grow. 62% of gamers are adults. 29% of gamers are over the age of 55.

45% of US gamers are female.

58% of Americans play games.

Surely, though, video gaming is unhealthy. I mean, you’re sitting there on a couch, or in a computer chair, or hunched over a smartphone for hours at a time. If watching TV for hours is bad for us, why wouldn’t video games be bad for us?

There are differences between the two. TV is wholly consumptive. You’re sitting there, passive and placid, while the TV does the work. You just consume it. Yeah, yeah, I’m sure a Ken Burns documentary is qualitatively different than binge watching reality TV, but my point stands.

Meanwhile, gaming requires mental and physical engagement. You’re problem solving. You’re reacting to stimuli. You’re planning and strategizing and, in the case of online gaming, competing and communicating with other people. Rather than watch beautiful people do interesting things on a TV, a gamer participates in the story and drives the narrative. On the face of it, video gaming is a different beast than TV and deserves a closer, more comprehensive look before dismissal.

There’s a huge body of research examining the potentially negative effects of video games. There’s also a huge body of research examining the potentially positive cognitive effects of video games. I’ll examine the former, followed by the latter. Then I’ll give my take on everything.

Video games and violence.

This is a popular notion that arises whenever a school shooter’s personal history reveals a fondness for playing violent video games, but the actual evidence is murky. Some researchers are adamant that video games increase aggression and violence, while others take the opposing view.

In a number of studies, playing violent video games has been linked to increased aggression. Most of this aggression occurs immediately after the gaming session and lasts just a few minutes. Researchers test increased aggression by having subjects play games and then giving them the opportunity to dose an unseen study participant with something unpleasant – loud noises, hot sauce, cold water. Subjects can make the dose as strong (loud/spicy/cold) as they desire. The louder/spicier/colder the delivery, the greater the aggression.

Other researchers aren’t very convinced by the inconsistent results, either (PDF). Like Christopher Ferguson, a psychology professor from Texas A&M, who frequently points out limitations and errors in studies that find links between gaming and violence, publishes papers that find no relationship between the two, and discusses the futility of even studying “violent video games” as a monolithic entity when they’re all so different from each other.

The causality may be reversed as well. An earlier study of adolescent boys in the Netherlands and Belgium found that aggressive teens are more attracted to violent video games in the first place. The authors suggest a “cycle of desensitization,” whereby aggressive teens play violent video games which make them even more tolerant of real violence, but I don’t think we have sufficient evidence to show that.

A 2014 paper even suggests that it’s not the violence in a video game causing the short term aggression, but the frustration from losing or failing to master the controls. That means that losing a match in Call of Duty, a round in Tetris, a game of Ultimate, or even a prized property in Monopoly could all temporarily increase your aggression. Now, I’m no video gamer. I do enjoy a board game or two when I get the time, and I can get pretty competitive and aggressive, especially when I lose. Same goes for Ultimate Frisbee. It’s fun, but it’s competitive fun; anyone who’s played a game with me at PrimalCon has probably noticed the subtle shift in tone when the game’s on the line. I don’t like to lose. Is that unhealthy or dangerous?

We just don’t see the evidence that video game-induced aggression is causing a wave of violence. Gaming is more popular than ever in this country and violent crime rates continue to drop. If anything, increased sales of violent video games are associated with a decreased incidence of violent crime. I’m not convinced this temporarily increased aggression in a contrived clinical setting is all that bad, let alone leads to long-term aggressive behavior.

Video games and stress.

A considerable body of evidence shows that playing video games can trigger the stress response and engage the sympathetic nervous system. It makes sense, doesn’t it? Video games catapult you into stressful and increasingly realistic situations – gunfights, car chases, zombie apocalypses – where people are trying to kill and/or eat you. When you’re playing online and your opponent is another human, the stakes get even higher.

Remember, though: lots of things that are good for us, like exercise, engage the stress response. The key is balance between stress and recovery. Exercise is self-limiting, if you do it right. You can’t deadlift for four hours straight because your body will simply quit before you do too much damage. And when you override your body and do something like Chronic Cardio, you risk injuries and long term negative health effects. Gaming doesn’t have the off switch. You can easily play for hours and hours, just running with a chronic flight or fight response.

Stress isn’t bad. Too much stress is bad. Too little is also bad.

Video games and obesity.

Compared to sitting around doing nothing for an hour, playing games for an hour increases short term energy intake.Violent games may have more of an effect, causing an increase in blood pressure and calorie intake and a preference for sweets. My take is that gaming can be stressful – as we’ve already shown – and stress tends to increase food intake. But so does reading an essay and writing a short response to it. It doesn’t help, of course, that it’s logistically tough to eat healthy food while gaming. You’re not going to pause your game to tuck into a braised lamb shank with whipped butternut squash, but you will cram a fistful of Doritos into your mouth without skipping a beat.

Okay, what about the beneficial effects to cognition that don’t get nearly as much press as the bad effects? Let’s take a look.

A recent review of the evidence published in the American Psychologist found that playing commercial video games (especially the “violent” ones that involve shooting and quick decision-making) has a number of cognitive benefits (PDF):

Improved spatial skills that carry over into non-video game environments.

Increased neural efficiency.

Improved problem solving.

Enhanced creativity.

Just recently, a study comparing Portal 2 (a first-person puzzle game) and Luminosity (the most popular and widely used brain game) found that Portal 2 improved cognitive skills in the short term more than the game designed to do it. Speaking of brain games, they might not even really work.

And after two months of playing Super Mario, a side scrolling platformer designed purely for fun, gray matter in certain regions of the brain increased, indicating structural neuroplasticity. The researchers think similar video games could be used as therapeutic tools for mental disorders that cause these brain areas to shrink.

Furthermore, another study found that lifetime video gaming history (called “joystick years”) was associated with increased brain volume in areas linked to navigation and visual attention; logic/puzzle games and platformers (like Super Mario) had the strongest effects.

In women who never or rarely gamed, playing the real time strategy game Starcraft for 40 hours over six weeks increased cognitive flexibility, or the ability to quickly switch from one task to another.

It also has great therapeutic potential that’s already being realized. Video gaming has been used to help the blind learn to navigate through unfamiliar environments (in the real world), dyslexic students learn to read, and stroke patients regain lost motor skills, for example.

I have a few reservations, though.

One genre of video game I’m fairly suspicious of are the social media games. They’re time suckers, wallet drainers, and according to a leading game developer, are designed to be “negative” and “draining” experiences that invade your thoughts, disrupt your waking and sleeping life, and keep you in a heightened state of stress and unease. Many of these games penalize you for taking breaks; your crops will wither and your livestock will die if you fail to log in and water and feed them. And most contain sticking points that require real-world cash in order to progress and keep playing. I’ve heard about marriages dissolving because of a partner’s addiction. They’re whipping them out at dinner, in the middle of conversations, checking in during sex. They’re draining their bank accounts.

Massively multiplayer online (MMO) games, like World of Warcraft, may also be problematic for many of the same reasons. Although the majority of players aren’t letting their kids starve or locking them in trash-filled RVs for years, the incidence of marital, financial, social, employment, sleep, health, and family problems among heavy MMO players is high.

Gaming is only going to get more realistic as time goes on. The uncanny valley is already flattening thanks to video game developers taking advantage of the increasing processing power available, and pretty soon the opponents you gun down in Call of Duty will be indistinguishable from the real thing, at least visually.

And with the coming wave of virtual reality headsets like Oculus Rift and Sony Morpheus that promise to immerse gamers in three-dimensional virtual game spaces, gaming will move from the living room/office to the inner space. Gamers should eventually be able to live out full-blown Star Trek holodeck-style simulated realities with total sensorial immersion. If that’s the case, and a video game warzone feels almost exactly like a real-life warzone (except for actual injuries), and your nervous system assumes that yes, a velociraptor really is coming for your throat, it’ll be tough to remain in rational, normal headspace. That could be problematic. We’ll just have to wait and see.

For now? I see nothing wrong and a whole lot right with gaming, if that’s what you’re into.

Gaming can be social, whether you’re playing with friends online or on the couch next to you.

Gaming can be competitive. It’s good to feel the pulse of adrenaline as you go toe to toe with someone else, even if that someone else is a non-player character generated by the game.

Gaming can be creative. Perhaps the most popular game right now, Minecraft, allows players to construct complicated structures and build entire worlds out of the game’s raw materials.

Gaming can be relaxing. It’s not all guns and dwarves and aliens.

Bottom line: gaming is play. And play is a good thing. As long as you don’t let gaming take over your life and crowd out or disturb your physical activity, your relationships, your eating habits, your sleep, your sunlight, your nature exposure, your green space time, your exciting and fun and meaningful pursuits out there in the real world – why not play a little?

Seeing as how I’m not a gamer myself, and this is mostly just an academic interest, I’d love to hear from all you gamers out there. Does today’s post jibe with your experiences? Did I miss anything? Got any recommendations for Primal people who might be interested in gaming? Let’s try to avoid any console wars, though, okay?

em>Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

October 20, 2014

Dear Mark: Eggs and Colon Cancer; Softened Water and Health

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a two-parter. First up is a question about a sensitive subject: the collective Primal love of all things egg. They form the backbone of millions of breakfasts across the ancestral health community on a daily basis, but David wonders if they might be contributing to colorectal carcinogenesis. There are a few studies that appear to suggest a connection; should we worry? After that, I discuss the effects of softened water on human health. Is it safe? Is it healthy? Read on to find out.

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a two-parter. First up is a question about a sensitive subject: the collective Primal love of all things egg. They form the backbone of millions of breakfasts across the ancestral health community on a daily basis, but David wonders if they might be contributing to colorectal carcinogenesis. There are a few studies that appear to suggest a connection; should we worry? After that, I discuss the effects of softened water on human health. Is it safe? Is it healthy? Read on to find out.

Let’s go:

Hi Mark,

So I was eating close to a dozen egg whites (maybe 1-2 whole eggs) a day for a few weeks up until yesterday (10/13) when I came across an article on the alkaline diet which prompted me to look at some studies about egg consumption (including just egg whites). These studies were negative and not just because of the high cholesterol argument but because of colon and rectal issues. I never heard this before but the study is from the 90’s and well known. Wtf!? What is your position on egg consumption?

Thanks,

David

I’ve seen those egg/colon cancer studies, and they’re almost always referring to data pulled from ecological studies. An ecological study looks at large populations defined temporally or geographically. In this case, the populations were geographically-defined – they plotted the colon cancer deaths in each country against the average egg intake of that country (using a total of 34 nations, even though data was available for more). Sure enough, the more eggs a country consumed, the more colon cancer mortality they had. So, swear off eggs forever?

I’m not convinced we need to do that.

First, this is just an observational study. It’s an observation of a correlation, an association. It cannot prove causality. To do that, you’d have to propose a mechanism for the association. Here’s one mechanism, though it’s probably not the one the researchers would have chosen: rising income.

Egg intake (and intake of animal protein in general) rises as a nation’s income rises. The richer the nation, the more eggs they eat.

The richer a nation, the higher the life expectancy.

The higher the life expectancy, the more numerous the cancer deaths. Cancer is an old person’s disease. And mortality from colorectal cancer in particular is strongly linked to age, with the highest death rates occurring in men and women over 85. If your nation’s life expectancy is on the low end, your citizens aren’t living long enough to get colorectal cancer in droves, let alone die from it.

Denise Minger proposes another mechanism: schistosomiasis infection. Schistosomiasis is a disease caused by various species of parasitic worms that’s fairly common across Africa, parts of Asia, and South America. Why does it matter? There is extensive epidemiological and clinical evidence suggesting a causal link between chronic schistosomiasis infection and colorectal cancer. And as Denise shows, when you remove the regions where schistosomiasis infection is widespread, the link between egg intake and colorectal cancer disappears.

Second, colon cancer mortality is important, no doubt. I don’t want to die from it, and I gather neither do any of you. However, I also don’t want to die from any other degenerative disease like heart disease, diabetes, stroke, or any of the other cancers. And as Paul Jaminet elegantly displays, when you plot egg consumption against the ultimate barometer – all-cause mortality – in those same countries, the association is inverse; the greater the egg consumption, the lower the risk of all-cause mortality. Again, this is just epidemiology and not proof of causation, but it’s equally as valid as the colon cancer/egg epidemiology.

But let’s not be hasty. This is our health we’re talking about, and we shouldn’t dismiss evidence. Assuming the association actually is causative, what could explain it? Is there anything we should pay attention to when eating or choosing eggs?

If eggs are causing colorectal cancers, it probably has something to do with the cholesterol oxides – the oxidation products that form when egg yolks encounter high heat or oxygen and which have been implicated in carcinogenesis. For example, in rats, a high cholesterol diet only promotes colon cancer when combined with an oxidizing agent that, well, oxidizes the cholesterol.

When it comes to preventing cholesterol oxidation, quality of the eggs matters – a lot. I’ve always felt that when deciding where to spend your money on food, aiming for high-quality animal foods (whether butter or beef or eggs or fish) is more important than buying organic lettuce for eight bucks a pound. And we have research showing the huge disparity in quality between pastured eggs and battery farm-raised eggs that could have meaningful differences on the effects the eggs you eat have on colorectal cancer risk.

For instance, conventional eggs from corn and soy-fed chickens are higher in unstable omega-6 fats. When you eat conventional eggs, your LDL is more easily oxidized than the person who ate pastured eggs. And pastured eggs are far higher in vitamin E, an antioxidant that prevents cholesterol oxidation.

How you cook the egg matters, too, just as how you cook your meat matters. Full-on hard boiling your egg (till the yolk turns chalky) dramatically increases lipid oxidation, even more than scrambling them. If you plan on eating lots of eggs, you’d be better off keeping the yolks softer rather than harder. I’ll sometimes even toss in a raw yolk or two into a smoothie. As long as you’re getting eggs from a trusted source, the risk of food poisoning is minute. Besides, everyone knows that soft-boiled eggs are far superior to hard-boiled eggs.

Check out my egg guide for more guidance on handling this incredible food.

Mark,

I’ve looked up and down the internet, and can’t seem to get a straight answer anywhere about the health effects of drinking softened water. All the water softener companies want to assure me that is the best thing since sliced bread, while an assortment of other sites insist it will kill me in a variety of unpleasant ways. Have you done any poking around on this issue?

Thanks,

Jesse

The World Health Organization doesn’t consider softened water suitable for drinking (PDF), citing a large amount of evidence.

Softened water leaches more toxic metals than hard water. In one instance, softened water sitting in storage containers with brass fittings and lead-soldered seams caused lead poisoning in kids who drank it. Also, the calcium and magnesium normally in hard water can inhibit the absorption of lead and cadmium from the intestine by binding to receptor sites and/or forming compounds that we cannot absorb; removing them removes their inhibitory effects.

Using softened water to cook food (meat and vegetables) leads to greater mineral loss. Up to 60% of magnesium and calcium, 66% of copper, 70% of manganese, and 86% of cobalt leach into softened water used for cooking.

The biggest downside, though? Softening water means removing the minerals that are supposed to be there, minerals like calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate that our bodies need to function. It’s likely that we’ve evolved drinking hard water. Most natural bodies of water, including the rivers, streams, and springs from which humans have historically quenched their thirst, contain hard water rich in these minerals. And a decent amount of epidemiological evidence points toward it being a factor in human health. A small sampling:

Magnesium content of water is associated with lower mortality from heart attacks.

Serbian municipalities with high-magnesium drinking water have less hypertension than areas with low-magnesium water.

Magnesium content of tap water seems to be inversely correlated with cardiovascular disease mortality.

Calcium content in drinking water is associated with a reduced risk of kidney cancer.

Geographic regions with higher lithium content in drinking water have lower suicide rates.

This is my favorite: drinking high-mineral deep sea water lowered lipid peroxidation, total, and LDL cholesterol in subjects with high cholesterol.

If your house has softened water and you’d prefer to drink a harder water, consider these options:

Remineralize it with mineral drops.

Splurge for a good high mineral-content mineral water. Gerolsteiner is a good widely available one and, if you can find a European market (or you happen to live in Europe) that carries it, Borsec (from Romania) is also great. Both of these waters are rich in calcium, bicarbonate, and magnesium. Whole Foods brand mineral water has a high mineral content, too, although I don’t know the specific mineral breakdown.

Find a spring near you and go get yourself some naturally hard water (that’s often free of charge).

Also, make sure your diet is otherwise rich in minerals. To replace the lost calcium, magnesium, and other minerals, eat leafy greens like spinach, chard, and kale; bony fish like sardines and herring; high-quality grass-fed dairy like kefir, aged cheeses, and yogurt; and nuts like almonds, brazil nuts, and macadamias.

That’s it for this week, folks. Thanks for reading and be sure to leave your thoughts below.

Further Your Knowledge. Deepen Your Impact. Become an Expert! Learn More About the Primal Blueprint Expert Certification

October 19, 2014

Weekend Link Love – Edition 318

We’ve got three Primal Blueprint Transformation Seminars coming up: In NYC on November 1; Richmond, VA on November 15; and West Bloomfield, MI, also on November 15. Kickstart your Primal lifestyle – or give someone else the gift of a lifetime!

We’ve got three Primal Blueprint Transformation Seminars coming up: In NYC on November 1; Richmond, VA on November 15; and West Bloomfield, MI, also on November 15. Kickstart your Primal lifestyle – or give someone else the gift of a lifetime!

Research of the Week

Eating disorders may have a gut bacterial origin.

Biomarkers of dairy fat consumption are yet again associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.

Is Ebola more virulent in selenium-deficient people (an old PDF)?

Even in surgery, the placebo effect exist.

A “Paleothitic-type diet” has favorable effects on the metabolic syndrome (PDF), including weight loss despite “efforts to keep bodyweight stable.”

New Primal Blueprint Podcasts

Episode #38: Ask the Primal Doctor – Q&A with Dr. Cate Shanahan – Dr. Shanahan covers a wide variety of topics, including hormone replacement therapy (for men and women), hot flashes, pharmaceutical treatment of mild hypertension, and a little-known predictor of longevity and healthspan.

Each week, select Mark’s Daily Apple blog posts are prepared as Primal Blueprint Podcasts. Need to catch up on reading, but don’t have the time? Prefer to listen to articles while on the go? Check out the new blog post podcasts below, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast here so you never miss an episode.

Why These Nine Famous Thinkers Walked So Much

How to Increase Your Heart Rate Variability

Mark’s Daily Apple Best of 2014, Vol. 6: Gluten

The Definitive Guide to Grains

The Power of Words: How We Talk About Food

Interesting Blog Posts

Pediatric medicine’s damaging oversight: sleep.

Before you use buttered coffee in place of a meal, heed these warnings.

This might be why resistant starch gives (most) people such wild dreams.

Dr. Briffa’s thoughts on walking versus running. I mostly concur.

No, vegetable oil fatty acids are not essential – as long as you’re eating seafood or taking DHA supplements.

How cooking, cooling, and cooking starches again reduces their glycemic impact more than just cooking and cooling them.

Media, Schmedia

BBC science journalist questions the conventional wisdom regarding saturated fat. He’s still a little leery of it, but it’s a fair piece.

Outside Magazine covers the growing trend of high-fat diets among endurance athletes.

Everything Else

Kids don’t just need to move. They need to spin, roll, flip upside down, and fall down on daily basis.

A very moving video and spoken-word piece about the effect technology has on our social lives.

The NY Knicks’ Amar’e Stoudemire takes red wine baths after games.

If you feel like reaching for that second (or third) cup of coffee, go right ahead. That’s probably just your genes helping you reach your optimal caffeine dosage.

A new two-legged chair makes sitting a “bearable discomfort” that’s healthier than the traditional way.

If only it were a bald eagle instead of a hawk.

Why.

Recipe Corner

Rest assured, weeknight shredded pork tacos with spicy pear salsa are also good on the weekends.

East meets west (and then takes a weeks-long briny bath together): kimchi kraut.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Oct 19 – Oct 25)

Starch: Fallback Food or Essential Nutrient? – How important was starch to our ancestors?

Making Music: Why You Should Pick Up and Instrument and Start Playing – We can’t all be musical geniuses, but we can derive benefits from learning to play a musical instrument.

Comment of the Week

“I’m not normally into literary works, but this post was interesting, Mark. And for some reason once I reached the end of reading the Beethoven section, I realized I had read it as Beeth-oven a la ‘Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure.’”

October 18, 2014

Slow Roasted Chicken

There are already so many different recipes for cooking a whole chicken, you might wonder why you need one more. But if you’re a fan of store-bought rotisserie chicken, then you definitely need this one. Just like a cooked chicken from the market, the meat on this bird is plump, juicy and tender and the skin browned and deeply flavorful. Plus, this recipe is so simple and hands-off that it’s basically as convenient as driving to the store to buy a rotisserie chicken.

There are already so many different recipes for cooking a whole chicken, you might wonder why you need one more. But if you’re a fan of store-bought rotisserie chicken, then you definitely need this one. Just like a cooked chicken from the market, the meat on this bird is plump, juicy and tender and the skin browned and deeply flavorful. Plus, this recipe is so simple and hands-off that it’s basically as convenient as driving to the store to buy a rotisserie chicken.

What’s the secret? Low and slow. Most recipes for roasted whole chicken crank the oven temperature above 400 ºF/205 ºC in an attempt to crisp up the skin and quickly cook the meat before it dries out. This recipe keeps the temperature at a low 300 ºF/150 ºC and cooks the chicken slowly for 3 hours. While the skin doesn’t get super crispy, it’s far from flabby, and has the same rich flavor that rotisserie chicken skin has. The meat is flavorful and really moist but never rubbery around the bones, like some roasted chickens can be.

The long cooking time at low heat is a gentle and reliable way to make sure the chicken is fully cooked without drying out, so it’s really hard to over or under cook this bird. As an another added bonus, you get to choose the quality of the chicken (ideally pastured and/or organic) and don’t have to wonder if the chicken’s been ruined by a rub down in vegetable oil or other undesirable ingredients, like many store-bought rotisserie chickens are.

Tender, flavorful, healthy and easy – four good reasons why this recipe for roasted chicken is a real winner.

Servings: 1 whole chicken

Time in the Kitchen: 15 minutes, plus 3 hours roasting time

Ingredients:

1 3 to 4 pound whole chicken (1.4 kg to 1.8 kg)

2 teaspoons fennel seeds (10 ml)

1 teaspoon coriander seeds (5 ml)

2 teaspoons paprika (10 ml)

2 tablespoons thyme, plus several sprigs to stuff in the chicken cavity

(30 ml)

1 tablespoon kosher salt (8 g)

3 tablespoons olive oil (45 ml)

1 lemon, quartered

Instructions:

Preheat oven to 300 ºF/150 ºC.

Grind fennel and coriander seeds. Mix with paprika, thyme, salt, and olive oil. Rub all over the chicken.

Stuff the lemon pieces and thyme sprigs inside the chicken cavity. Tie the legs of the chicken together.

In a roasting pan or rimmed baking sheet, roast the chicken for about 3 hours. As juices/fat accumulate in the pan during the roasting process, baste the chicken a few times while it cooks.

When the chicken is done, the skin should be nicely browned and the meat very tender. A thermometer inserted between the leg and thigh should register at 165 ºF/74 ºC.

Not Sure What to Eat? Get the Primal Blueprint Meal Plan for Shopping Lists and Recipes Delivered Directly to Your Inbox Each Week

October 17, 2014

Finding My New Normal

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

I want to share my MDA success story. I consider it a success because it has been a long-term solution and not a “quick fix.” I can’t thank you enough for the website contributions and the insights on primal living. I finally feel like the young healthy person my age should reflect. Below is my story that I am so thankful to share.

I want to share my MDA success story. I consider it a success because it has been a long-term solution and not a “quick fix.” I can’t thank you enough for the website contributions and the insights on primal living. I finally feel like the young healthy person my age should reflect. Below is my story that I am so thankful to share.

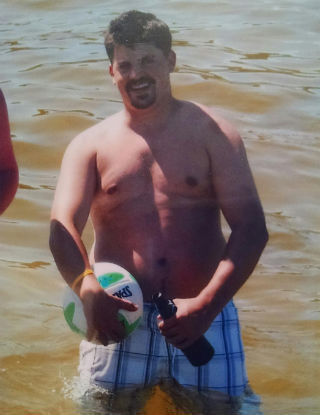

For most of my life, I have sought to find a sense of normalcy. Normal to me as a young adult was playing sports and eating as much of whatever I wanted. Any junk food you could think of, I was eating it—all the while not gaining a single pound and feeling great. I even had coaches asking me to eat double the amount of food I would normally eat to put some weight on me for sports like football and baseball.

This is not that uncommon for young people and I by no means feel unique in this regard. Even less surprisingly, I went off to college and carried much of this “normal” lifestyle with me. You can probably guess what happened next. My “new normal” became a lifestyle of eating even worse, drinking more, and sleeping less. The stress of school combined with work compounded this lifestyle. BOOM—I was roughly 65 pounds overweight five years after I graduated high school. This is the result of my “new normal” lifestyle at its peak.

This is not that uncommon for young people and I by no means feel unique in this regard. Even less surprisingly, I went off to college and carried much of this “normal” lifestyle with me. You can probably guess what happened next. My “new normal” became a lifestyle of eating even worse, drinking more, and sleeping less. The stress of school combined with work compounded this lifestyle. BOOM—I was roughly 65 pounds overweight five years after I graduated high school. This is the result of my “new normal” lifestyle at its peak.

I saw this picture a few weeks after it was taken and decided I needed a different normal. This picture was not reflective of who I felt I was on the inside. I didn’t know much at the time about eating as a means to improve my health, but I did know how to exercise through my time playing sports when I was younger. The simplest equation I knew was calories in vs. calories out. I created a calorie counting account online and tracked my food intake and exercise regimen religiously every day. I starved myself and ran my brains out with the goal of losing two pounds per week. This would be the way I would find my new normal.

Guess what? It worked! I felt like hell and hated every calorie I logged or every mile I ran. But it was working. I was losing weight! This is what normal must feel like, right? You have to sacrifice everything to be fit and healthy. I even ran two marathons while following this regimen. My new normal was finally working—until it wasn’t. The minute I stopped training for a marathon or counting my calories, the weight came back, and came back fast. My new normal was letting me down and I became frustrated. I was sick of running multiple hours a day and my calorie counting diet always left me tired and hungry. I could feel myself letting go and slipping back into my more destructive “new normal” of years passed.

Guess what? It worked! I felt like hell and hated every calorie I logged or every mile I ran. But it was working. I was losing weight! This is what normal must feel like, right? You have to sacrifice everything to be fit and healthy. I even ran two marathons while following this regimen. My new normal was finally working—until it wasn’t. The minute I stopped training for a marathon or counting my calories, the weight came back, and came back fast. My new normal was letting me down and I became frustrated. I was sick of running multiple hours a day and my calorie counting diet always left me tired and hungry. I could feel myself letting go and slipping back into my more destructive “new normal” of years passed.

(This was taken after my first half marathon. I had finally woken up and ditched the horrible beard by then.)

What was most embarrassing at the time was the fact that I had been dating, got engaged, and ultimately married a dietitian. How could an overweight and very unhealthy guy marry a dietitian? My wife always gave me all the tools I needed and all the support I could ever ask for to be successful. Regardless, I was still failing her and myself. This is when I met a Grok (through my wife) that helped me find a new normal that finally changed my life for good.

My wife’s college roommate is also a dietitian. Her husband, who is built like a Sherman tank, is an avid CrossFitter. He and I bonded quickly and became fast friends. So much so, that he felt comfortable enough to begin poking fun at me for running marathons while still maintaining a certain “heftiness.” Slowly and subtly he encouraged me to do CrossFit and I kept blowing him off, not wanting to join his cult. Then I watched him perform in a local CrossFit competition that blew my “new normal” at the time into the stratosphere. Here’s the most amazing part of it all: when I asked him how I could get on his level, he attributed his physique not to CrossFit, but to living like Grok. I picked his brain for weeks after the competition to understand what, by then, was normal to him. He referred me to Mark’s Daily Apple and my new normal evolved one last time.

The change was amazing and followed a similar path of the many other stories I so diligently read on this site every week. I told my wife I wanted to start a primal lifestyle. She was totally on board, as she had been in the past, and helped me everyday to be mindful. I ditched sugars and grains. I focused on eating fresh whole foods. I stopped drinking diet soda, which I normally craved daily. I got enough sleep at night. I stopped running until I was blue in the face and focused on HIIT training a few days a week instead.

The change was amazing and followed a similar path of the many other stories I so diligently read on this site every week. I told my wife I wanted to start a primal lifestyle. She was totally on board, as she had been in the past, and helped me everyday to be mindful. I ditched sugars and grains. I focused on eating fresh whole foods. I stopped drinking diet soda, which I normally craved daily. I got enough sleep at night. I stopped running until I was blue in the face and focused on HIIT training a few days a week instead.

For the first week, I felt like death and wasn’t sure I could carry on. I was reassured this was to be expected and powered through. I completed The 21 Day Challenge and decided that I would double it for good measure. To this day, I still feel well rested every morning and have loads of energy throughout the day. I still have my bad days, weekends, and even weeks. But I am now confident in what is actually normal in my life. I am so thankful for all of the helpful information I refer to this site for daily. I even challenged my dad to take the 21 Day challenge himself. Hopefully he can find a new normal too. This is my normal. Period.

Ryan

October 16, 2014

How Your Primal Connection to Water Runs Deeper Than Thirst

The guy who kayaks and sets up camp along the same river each year. The woman who gets through the first year after her husband’s death one nightly hot bath at a time. The girl who brings her thoughts to the ocean each evening before sunset. The boy who throws rocks in the lake every day. The older couple who fall asleep to the sound of the waves. When was the last time you spent a period of time next to (or in) water? Maybe it was a week, or maybe it was ten minutes. Chances are, no matter how little time it was, it changed you somehow. It shifted your mood. It relaxed your thoughts. It softened the edges of your day, and you left at least somewhat revived.

The guy who kayaks and sets up camp along the same river each year. The woman who gets through the first year after her husband’s death one nightly hot bath at a time. The girl who brings her thoughts to the ocean each evening before sunset. The boy who throws rocks in the lake every day. The older couple who fall asleep to the sound of the waves. When was the last time you spent a period of time next to (or in) water? Maybe it was a week, or maybe it was ten minutes. Chances are, no matter how little time it was, it changed you somehow. It shifted your mood. It relaxed your thoughts. It softened the edges of your day, and you left at least somewhat revived.

Many of us grew up or now live close to a body of water. Still more of us choose to vacation by water – spend a week at the beach, stay in a cabin by the lake, camp by the river, etc. (By extension, how many of you wish you did or are planning to?) Even if we live in the middle of a major city, think of how people congregate around a city fountain to eat their lunch or simply sit and watch the people go by? The fact is, people invariably congregate around water (kind of like the kitchen at a house party). We’re drawn to water like our animal brethren despite the fact we have faucets and water bottles at our ready disposal.

Prehistoric human communities and, later, civilizations developed around water. Naturally, it was a matter of survival then. Human can survive on average about three days without water (despite those headline-grabbing outliers who manage a week or more). Lakes, rivers and oceans offered meals as well as hydration. These days we can live hundreds of miles from substantial water sources but be fully supplied through modern modes of transport. Yet, as with so much of our physical and cognitive blueprints, the psychological draw (and reward) operates beyond the context of necessity. To this day, surveys continually show people substantially prefer landscapes (whether urban or rural) with visible water to those without water. (PDF)

Water is at once perhaps the most utilitarian substance. Yet, it is also an aesthetic influence and even spiritual symbol that reaches deep into our innate associations. Culturally speaking, water embodies varied and significant archetypal meanings. Religious ceremonies and rituals using water abound across the globe around themes of cleansing, immersion, initiation and transformation.

It is also a sensual force that acts on us both physically and emotionally. Aquatic therapy (e.g. water play, exercise and flotation) is used for individuals with autism and other neurological conditions or trauma for proprioceptive and tactile input. Emotionally speaking, anyone who’s luxuriated in a hot bath after a stressful week or used a shower to “wash the day away,” can understand something of its healing element. Whether we approach it as aesthetic power, spiritual presence or therapeutic remedy, water holds a deeply ingrained if not sacred place in our evolutionary psyche.

Dr. Wallace J. Nichols, a marine biologist and author of Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do picks up this very idea and describes in full detail the common human experience of water exposure (or immersion) using everything from historical poetry to clinical study results to his own scientific experimentation.

He describes his experience, for example on a North Carolina shore while a 68-channel full-spectrum mobile EEG unit is measuring his subconscious reactions to the water with data collections 256 times per second. As he observes and jumps in to swim, would any of us be surprised to hear the EEG reflected both “fear” and “exhilaration”?

Bodies of water, particularly large bodies like the ocean can dwarf us, leaving us with a euphoric sensation of skimming the edge of risk or with a quiet, contemplative release in the shadow of a force so much greater and more timeless than ourselves.

Yet, the connection and rewards are tangible and becoming clearer with unfolding research. Nichols assembles an impressive array of studies supporting the role of not simply “green” (general nature) space but specifically “blue” space (body of water) exposure in encouraging greater stress relief, potent trauma therapy, added physical activity, and better community cohesion. Studies have found a moderate gain in general well-being and (likely related) an increase in exercise in those living on or near coastal areas as opposed to those who live inland. What’s more, those who exercise in the presence of water demonstrate greater self-esteem and better mood than those who exercise in other natural settings.

Researchers have analyzed the data of hundreds of studies related to water exposure and affirm the mental and physical health benefits (e.g. related to cardiovascular health, cancer, obesity, post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction recovery, depression, and anxiety) that are difficult to always scientifically measure but simple to appreciate whether our experience is “recreational” or “contemplative,” “harvest” (e.g. fishing) or aesthetic. (PDF) However we act on water, it’s clear it acts on us.

Nichols takes it a step further, coining the term “blue mind” as the calm, “mildly meditative state” and peaceful, connected sense of satisfaction we experience in a body of water’s presence. He considers this blue state of mind as a critical antidote to modern stress soak we experience in this disconnected age. At issue, he claims, is our own mental well-being. Our “emotional interaction with the most prevalent substance on the planet,” as Nichols puts it, has implications for individual as well as societal health, not to mention environmental sustainability. Our evolutionary predispositions and preferences are far from archaic shadows but perhaps saving graces.

Thanks for reading today, everyone. What are your favorite “blue” places and memories? What could time near water do for you today. Contemplate that – and have a great end to your week.

Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

Further Your Knowledge. Deepen Your Impact. Become an Expert! Learn More About the Primal Blueprint Expert Certification

October 15, 2014

Why These Nine Famous Thinkers Walked So Much

A couple weeks back, I wrote about how integral walking is to being human. And over the years I’ve written about the health benefits of walking, how and why you should walk barefoot, and even a definitive guide on the subject. In other words, I’m a huge proponent of walking and I think just about everyone who’s able should do more of it. But I’m not the only one that finds daily walks critical to health, energy, mental clarity and, ultimately, at least in some part, my success as a human being. Many of the most accomplished and creative people throughout history have also found walking to be an integral part of their daily routines and key to their success as artists, creators, writers, musicians, thinkers, and human beings.

A couple weeks back, I wrote about how integral walking is to being human. And over the years I’ve written about the health benefits of walking, how and why you should walk barefoot, and even a definitive guide on the subject. In other words, I’m a huge proponent of walking and I think just about everyone who’s able should do more of it. But I’m not the only one that finds daily walks critical to health, energy, mental clarity and, ultimately, at least in some part, my success as a human being. Many of the most accomplished and creative people throughout history have also found walking to be an integral part of their daily routines and key to their success as artists, creators, writers, musicians, thinkers, and human beings.

Let’s look at how some of these folks used walking to improve their work:

Aristotle

Aristotle, the famous Greek philosopher, empiricist, and pupil to Plato, conducted his lectures while walking the grounds of his school in Athens. His followers (who quite literally followed him as he walked) were even known as the peripatetics – Greek for meandering or walking about. Ah, to witness one of history’s greatest minds utilizing the cognitive benefits of moving while thinking must have been incredible.

William Wordsworth

The poet with the most fitting surname ever, William Wordsworth walked nearly 175 thousand miles throughout his life while maintaining a prolific writing career. He managed these two seemingly opposing habits for two reasons. First, being shorter (but not necessarily easier) than novels, poems take less actual writing time to produce. Second, Wordsworth’s walking was writing, in a way. As he saw it, the act of walking was “indivisible” from the act of writing poetry. Both were rhythmic, both employed meter. He needed to walk in order to write.

Man, I feel like I’m in English lit class all over again.

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens, author, social commentator, walker? Yes. After writing from 9 in the morning to 2 in the afternoon, he would go for a long walk. A 20- or 30-miler was routine for him. When Dickens couldn’t sleep at night – which was often – he’d crawl London’s streets until dawn. Dickens walked so much that his friends worried, figuring he had a mania for walking that bordered on pathology. But clearly, the walking worked; Dickens was prolific, writing more than a dozen major and well-regarded novels, several short story collections, a few plays, and even some non-fiction books.

According to the man himself, if he couldn’t walk “far and fast,” he would “explode and perish” from the psychological burden of remaining still. I bet a treadmill desk would have blown his mind (and brought us even more works). Actually, it might not have worked for him. The walking was so important for Dickens because it meant he wasn’t writing, the act of which he found quite miserable and difficult. Walking was relief. Without the walking, he’d probably have gone mad.

Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau was a famous saunterer. In the aptly titled essay “Walking,” he comments on the etymology of the word “saunter,” noting that it comes from “the idle people who roved about the country… under the pretense of going à la Sainte Terre,” or the Holy Land. And for Thoreau, walking through nature was a kind of pilgrimage without a destination. His Holy Land was all around him. And as long as he walked, he kept discovering new temples, new places to worship.

John Muir

John Muir was a naturalist who helped preserve Yosemite, Sequoia National Park, and other wild areas from development and private interests. He wasn’t just “a” naturalist. He was the guy who climbed peaks to whoop and howl at vistas, chased waterfalls (take that, TLC), leapt “tirelessly from flower to flower,” and had an entire forest named after him. But here’s the thing about John Muir: he wasn’t whizzing around in his Prius with a “coexist” bumper sticker (nothing against either of those, by the way). He was walking, and hiking, and climbing, and traipsing through the wilds that he considered home.

It wasn’t just that walking inspired his nature writing. It’s that walking was often the only way to access the subject of his writing and passion. In that respect, walking was a utility for Muir.

Nassim Taleb

Taleb’s a contemporary writer, unlike most of these other famous walkers. You can find him trading jabs with critics on Twitter, probably in the last hour. He’s been writing about anti-fragility for many years, about how successful systems and economies and businesses must experience and be able to adequately respond to punctuated, not chronic, stresses and randomness to stay successful and robust. But it wasn’t until he started walking that he realized the same concepts applied to humans. We also need to face intermittent stressors to remain healthy, robust, and anti-fragile, and we require randomness and variation. So, for Taleb, that means some intense strength training every so often, a fair amount of relaxation, and lots and lots of aimless meandering as a foundation.

Patrick Leigh Fermor

I first read about Fermor almost a decade ago in a New Yorker piece describing him as a cross between Indiana Jones, Graham Greene, and James Bond. A British Special Operations officer, he fought in the Cretan resistance during World War 2, going undercover as a mountain shepherd and leading the successful capture of German commander General Heinrich Kreipe. But Fermor was also a serious walker. At the age of 18, after dropping out (or failing) of school and drifting somewhat aimlessly around London, he walked from western Holland clear to Istanbul over the course of a year and change. This walk transformed him from wayward youth to man, soldier, and eventual travel writer. Driving or taking the train wouldn’t have produced the same quality (man or writer), for walking allowed the total saturation of the senses and accumulation of detailed memories that informed his transformation and colored his writing.

Soren Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard had two main pursuits: walking and writing. He wrote through the morning until noon, when he’d walk the streets of Copenhagen, mentally composing paragraphs and working through new ideas. After the walk, he was back to writing (at a standing desk, no less). The success of his thinking depended almost entirely on his walking (emphasis mine):

Above all, do not lose your desire to walk. Everyday, I walk myself into a state of well-being & walk away from every illness. I have walked myself into my best thoughts, and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it. But by sitting still, & the more one sits still, the closer one comes to feeling ill. Thus if one just keeps on walking, everything will be all right.

That just might be the most useful, actionable piece of advice he ever wrote.

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Famous composer Ludwig Van Beethoven typically worked from sun-up through mid afternoon, taking several breaks to “[run] out into the open” and work while walking. One biographer described these short walks as a bee swarming out to collect honey. And then, after a large midday meal, Beethoven would take a longer, more vigorous “promenade” lasting the rest of the afternoon. These walks happened regardless of the weather, for they were important for his creativity. He would carry a pen and sheets of music paper in case inspiration struck – which it often did.

As you can see, walking isn’t just putting one foot in front of the other. For some of the greatest minds in history, walking was a way to clear the brain, prevent mental breakdown, extend life, solve – or evade – problems, fully experience the world, beat insomnia, and find life purpose. If it worked for these guys, if it by many accounts made these guys, it’s probably worth a shot. Don’t you think?

Yeah, things are different. We can’t all stroll through a Viennese forest, traipse along the cobblestone streets of 19th century London, or hope to beat the Yosemite Valley crowds by a hundred years. You might have to settle for a suburban sidewalk after work, a trail along a city creek, a crowded hike on the weekend, or even a quick jaunt out of the office to the Starbucks across the street. And that’s fine. What matters is the walking.

I hope this resonates with you. All I know is I definitely feel the need to go for a walk.

Thanks for reading, everyone! How does walking figure into your life, your work, your productivity?

Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

Further Your Knowledge. Deepen Your Impact. Become an Expert! Learn More About the Primal Blueprint Expert Certification

October 14, 2014

How to Increase Your Heart Rate Variability

Last week, I introduced the concept of heart rate variability – the variation of heart beat to beat intervals. Far from the metronome we might assume it to be, the healthiest heart beat follows a fractal pattern, with varying lengths of time separating each pulse. A higher heart rate variability (HRV) suggests a relaxed, low-stress physiological milieu, while a lower HRV indicates a need for recovery, rest, and sleep. That’s why athletes use HRV monitoring to plan their workouts and rest periods, PR attempts and deload weeks: it eliminates the guesswork. Even if you’re not an athlete, the HRV is a strong diagnostic biomarker for general health and resiliency. Today, we’ll be exploring 16 ways to increase it.

Last week, I introduced the concept of heart rate variability – the variation of heart beat to beat intervals. Far from the metronome we might assume it to be, the healthiest heart beat follows a fractal pattern, with varying lengths of time separating each pulse. A higher heart rate variability (HRV) suggests a relaxed, low-stress physiological milieu, while a lower HRV indicates a need for recovery, rest, and sleep. That’s why athletes use HRV monitoring to plan their workouts and rest periods, PR attempts and deload weeks: it eliminates the guesswork. Even if you’re not an athlete, the HRV is a strong diagnostic biomarker for general health and resiliency. Today, we’ll be exploring 16 ways to increase it.

The following tips are researched-based methods for increasing your HRV, but they’re not deal breakers. Failing to check one or several or even most of these methods off won’t necessarily result in rock bottom HRV. Maybe you have a job you love, but the commute is long. Maybe green tea makes you jittery and nauseated. I’m just giving you all the information I have so that you can find a method that works for you. No one can do them all; I certainly can’t.

Oh, and I won’t go into the normal stuff that positively impacts our HRV, like getting enough sleep and regular exercise. Those are all important, so keep doing them, but the benefits are implied and don’t require further explication or justification.

Let’s get on with it:

Rest.

We shouldn’t be aiming for perpetually high HRV, because that would mean we were never encountering any stressors. We couldn’t exercise. We couldn’t lift heavy things or sprint (not even once in awhile). We couldn’t watch scary movies. We’d never have anything to recover from and improve upon. But after these stressful events that tax our bodies, throw us out of homeostasis, and bias us toward the sympathetic nervous system, we must rest in order to restore our HRV. So make time to rest. And remember – you don’t just need to rest after a hard workout. Exposure to any stressor that increases sympathetic nervous system activity should be followed by some rest, even if it’s just chilling out with a good book.

Drink green tea (or take L-theanine).

Green tea is an interesting beverage, containing both stimulating (caffeine) and calming properties. In an animal model of diabetes, green tea consumption increased heart rate variability (among other cardiometabolic biomarkers). If you hate green tea, no worries. One of the active compounds found in green tea, L-theanine, has also been shown to increase HRV. That’s actually a big reason why I include L-theanine in Primal Calm – for its ability to reduce sympathetic nervous system activity.

Don’t procrastinate.

Procrastination is that form of self-sabotage that almost everyone practices despite the near universal denunciation it receives. I’ve railed against it before, and I’ve even given you some tips and tools for combatting it. Well, here’s another reason to stop doing it: it kills your heart rate variability. In almost every available study of HRV in college students during exam week, heart rate variability plummets. The more anxious and unprepared you are for a test, the more its impending arrival will tank your HRV. What’s funny is that the kids who tended toward lower HRVs actually performed better on the tests, but that’s probably a function of actually caring about the tests enough to cram for them. The better way is to plan ahead and remain low-stress during exam week not because you don’t care about doing well, but because you’re prepared.

Don’t work too much or commute too far.

Ha, I know. Easier said than done. Regardless, long working and commuting hours don’t just prevent you from seeing friends and family, doing things that you enjoy, and getting adequate sleep. They’re also strongly associated with reduced HRV.

Try active commuting unless it’s through an area of high pollution.

Although it didn’t measure HRV directly, one paper found that active commuting increased resilience to stress and reduced stress reactivity – two indices that generally correlate with higher HRV. However, active commuting amidst high pollution might be counterproductive. Air particulate exposure is bad enough for your health and HRV, but it gets worse when you add in running or cycling. Active commuters who commute through high pollution areas breathe in more air particulates and see greater reductions in HRV.

Find a job that gives you enough reward for the work you put into it.

We can’t all do jobs we love or deeply care about. I get that. But if we can find a job that gives back as much as we put into it, our HRV might benefit. One study found that job stress as measured by the work/reward ratio inversely correlated with HRV. People who felt they got sufficient reward for the work they put in (low stress) had higher nighttime HRV. People who felt they were putting in more than they received had lower nighttime HRV. Another study in young Finnish women had similar results. To me, this indicates that entrepreneurship might lead to a higher HRV, since despite all the stress that accompanies owning your own business, you definitely get the fruits of your labor (after taxes and overhead, of course).

Practice forgiveness.

Forgiveness practice is one of those methods that so-conventional-they’d-rather-die-than-take-a-supplement types would ridicule, but it’s got merit. One study actually examined the vagal ramifications of giving forgiveness compared to ruminating on a past transgression. Initially, both groups induced negative feelings by thinking about a time where they were wronged; this lowered HRV. Then, one group was told to forgive their transgressor and the other group was to continue ruminating on the transgression. In the forgiveness group, HRV increased while in the ruminating group, HRV remained depressed. Note that the forgiveness occurred entirely in the subjects’ heads. They didn’t actually contact their transgressors. Forgiveness can happen comfortably and exclusively from the confines of your own brain.

Do yoga.

There are dozens of yoga varieties, and most of them have been found to improve heart rate variability, whether it’s hatha yoga, yoga nidra, laughter yoga, or isha yoga. Even just lying in a single pose (savasana, or corpse pose) with relaxing music playing increases HRV. You won’t find me in leotards and dreadlocks (that’s what yoga dudes wear, right?) anytime soon, but I gotta admit that yoga is a powerful practice.

Try meditating.

If you search the literature for heart rate variability and meditation, you get the distinct impression that as with yoga, nearly every type of meditation practice has the potential to increase HRV. Vipassana (mindfulness meditation), zen, and pranic meditation all work. I’ve never had much success with meditating myself – guided meditation podcasts/Youtube videos worked better than trying to sit on my own – but it clearly works for many people.

Listen to the right kind of music.

In young women without experience listening to either, baroque music seems to improve HRV relative to heavy metal. Same goes for men. While I’d bet the kid with Metallica posters (I’m showing the pitiful extent of my heavy metal knowledge here, aren’t I?) on his walls would have a different HRV response to heavy metal than people without a prior relationship to it, maybe Viking death metal isn’t the best choice for anyone looking to relax and increase HRV. Also, don’t be fooled by the spacey vibes issuing from the local kundalini center; new age music seems to bias the autonomic nervous system response toward the sympathetic side. A safe choice is probably whatever music you find calming and soothing.

Breathe deeply and slowly.

Slow breathing consistently raises HRV. Don’t get hung up on the pattern of the breath, which doesn’t matter so much as long as the rate is slow. Of course, I wouldn’t recommend deep breathing exclusively. That would just be weird.

Try alternate nostril breathing.

Huh? It sounds odd, but it’s simple and it works:

Place your ring and pinky fingers at your left nostril and your thumb at your right nostril.

Block the left nostril using your ring and pinky fingers and inhale through your right nostril.

Block the right nostril with your thumb and exhale through your left nostril.

Inhale through your left nostril, keeping the right nostril blocked.

Continue for 9 more rounds.

Studies show that alternate nostril breathing can increase HRV.

Go for a walk in nature.

The Japanese therapy known as “forest bathing,” which involves taking a short, leisurely visit to the forest, increases HRV and reduces stress. Since all trees (and plant matter in general) give off the volatile organic compounds thought to be responsible for the benefits, any nature setting should do the trick.

Take fish oil or eat seafood.

Several studies indicate that taking omega-3 supplements can increase HRV. In patients with high triglycerides, a largish dose of EPA and DHA (3.4 grams/day) increased HRV at rest and in times of stress (when a high HRV can really help). A smaller dose (0.85 g/day) did not. In men who’ve recently had heart attacks (a population in dire need of improved heart rate variability), omega-3s increase HRV. These results jibe with the well-known inhibitory effect of marine omega-3s on stress hormones.

Travel back in time and tell your pregnant mother to start exercising.

Exercising during pregnancy appears to increase fetal HRV (a good thing, just as it is for humans out of the womb) and confer epigenetic benefits to the HRV of infants one month post-birth. It’s unclear whether these benefits persist into childhood and adulthood, but I’d probably take the bet that they do. If you can swing time travel, make it happen. Just be wary of paradoxes (don’t even go near your grandpa) and tears in the space time, even small ones. Take along a photo of yourself; if your image starts to fade, something has gone horribly wrong.

While you’re back there, have her also eat seafood or take DHA supplements.

Pregnant mothers who take DHA supplements (or eat foods high in DHA, like fish) improve the heart rate variability of their fetuses.

Okay, that’s it for today, folks. With any luck, everyone will find something new and useful to implement into their life. Even if you’re not into the HRV stuff, most of these recommendations have the added benefit of simply being pleasant and good for overall quality of life.

Any experts out there with personal experience care to add their methods for improving HRV? I’d love to hear. Take care, everyone, and thanks for reading!

Further Your Knowledge. Deepen Your Impact. Become an Expert! Learn More About the Primal Blueprint Expert Certification

October 13, 2014

Dear Mark: Sleep Deprivation as Hormesis, Sweet Cravings, CrossFit, and More

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a three-parter that’s really closer to a five-parter. First are a couple of questions from Joe, who first wonders about the hormetic benefits of acute sleep deprivation (are there any?) and then asks how he can beat a sweet tooth he suspects is brought on by lack of exercise. The second pair of questions concern CrossFit (is it an example of Chronic Cardio and should I be recommending it?) and breadfruit (does it have a place on the Primal eating plan?). And finally, Andy asks for the origin of the popular “gut is 80% of our immune system” statement.

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, we’ve got a three-parter that’s really closer to a five-parter. First are a couple of questions from Joe, who first wonders about the hormetic benefits of acute sleep deprivation (are there any?) and then asks how he can beat a sweet tooth he suspects is brought on by lack of exercise. The second pair of questions concern CrossFit (is it an example of Chronic Cardio and should I be recommending it?) and breadfruit (does it have a place on the Primal eating plan?). And finally, Andy asks for the origin of the popular “gut is 80% of our immune system” statement.

Let’s go:

Dear Mark,

Thanks for all you do. Your work provides a wealth of knowledge (accurate and not self-seeking), and I consider myself blessed to have found MDA.