Mark Sisson's Blog, page 204

November 3, 2016

Embodiment for Emotional Health: Is Mindful Movement a Primal Key?

“Women carry trauma in their hips.”

(The stray remark got my attention, too.) I was walking along the beach when I heard it. Two women, deep in conversation, had passed me. Between the waves and my dog’s bark, it was the only snippet I caught. One had matter-of-factly professed it, and the other offered a knowing sigh in agreement. As a trainer, the thought jumped out at me—not so much the gendered suggestion (I have no claim on expertise there) but the idea that emotion gets stored in our bodies and not just in our memories. All of us are at various points in life subject to pain, loss and suffering. Whether we contend with something as severe as trauma or something difficult but normal like grief, anxiety or resentment, how do unresolved emotions linger within our physiology or even particular locations or functions within it? How might these feelings that we retain act as a wild card in our overall health? Finally, in keeping with this possibility, does “moving through” emotional suffering oblige us to move bodily toward healing?

All of this, you could say, flies in the face of the modern, cerebral perspective. Ever since the the 17th Century, the Western sense of “true” identity has been philosophically disembodied (e.g. “I think, therefore I am.). The mind, with its thoughts and sentiment, was separated, elevated above the baser body of instinct and machination. Increasingly, however, that disembodied assumption doesn’t jibe with contemporary neuroscience. And let’s face it. It never quite squared with a primal sensibility.

Research into embodied cognition reveals how our bodies not only respond to our inner thoughts and outer environments but actually have the power to steer our emotional and intellectual reactions (and allow physical sensation to mirror abstract concepts—e.g. a subject judging a person as “warmer” while he/she holds a hot drink).

In essence, how we move and stimulate our bodies subtly but potently influences our emotional state.

Cultures that never philosophically divorced the mind from the body seem to have the edge here. They’re incidentally the wellspring of many movement-based contemplative practices, including yoga, active meditation and many martial arts. Long before even these traditions, however, indigenous groups participated in active, shamanistic ceremonies for healing.

Grok didn’t lie on the psychotherapist’s leather couch after all. Healing for the individual and the collective was simultaneously enacted and elicited through archetypal dance and physical ritual that symbolically embodied sensations of safety, belonging, and integration. (PDF) As observation of these ceremonies reveal, coordinating sounds and rhythms within traditional drumming and chanting respectively harmonize heart rates and produce innately calming Alpha waves. In a deeply visceral way, healing was synchronistically performed as well as received.

Today progressive psychotherapists have begun incorporating movement-based modalities like yoga poses within their practice. As clients talk through their wounds, they enact poses to support that opening and vulnerability. The effect of emotional release, however, didn’t begin in the psychotherapists’ room. Yoga instructors will tell you that “heart-opening” postures, for instance, inspire many a breakdown or breakthrough in their classes.

Fast forward to today, and even Western society has given rise to somatic therapies like Feldenkrais and the Alexander Technique, which (in a simplistic nutshell) reason that errant physical alignment or movement patterns can skew our sensory perception and hamper well-being.

But what about regular exercise? Can other, more basic physical activities offer a psychic release? Research is still clarifying this answer, but theoretically and anecdotally, it appears to be yes. We’ve long understood that exercise neurochemically acts on and within the brain. While studies have focused on benefits to cognition and mood, the crux here may be what happens in the moment rather than what comes afterward or builds over time. The interesting question may be, how does physical activity neurochemically allow us to engage certain brain centers or functions differently?

Can exercise, of a general or targeted sort, create a uniquely potent window for dealing with problematic memories and “lower” limbic responses?

Trauma experts like Peter A Levine note that the intensive fear of certain experiences “freezes” us like a wild animal caught by a predator. Vestiges of that momentary response, when severe and/or frequent enough, may never quite resolve. The physical cycle of fear, Levine posits, requires processing and closure for fully normal functioning to be restored. Similarly, the study of somatoemotional release within the craniosacral therapy field suggests that emotions can become locked within us and offers body positions for their effective release. These theories and fields aren’t without controversy, but they illustrate perhaps how movement may, indeed, move us emotionally as well as physically.

As a trainer, I’ve known many people who spontaneously took up exercise of one kind or another following points of major tragedy or transition in their lives. There was something about the shift in their needs and, in their words, something to the freedom they received on a long run or a challenging climb that became their best therapy. At times, something in their exertion opened the emotional floodgates. These moments, some have shared, were turning points in their grief or struggle.

Maybe for them there was something in that flow state, something to the re-grounding in sensation when they spent much of the day otherwise numb. Movement became the antidote to overwhelm and even offered access through emotional obstruction.

It’s an intriguing thought. I might not be ready to call it an official Primal principle, but movement for emotional health and psychological processing might just be one of the most essentially Primal concepts we can enact in our lives.

Thanks for reading, everybody. Does this concept resonate with your experience? Share your thoughts, and have a great end to the week.

The post Embodiment for Emotional Health: Is Mindful Movement a Primal Key? appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

November 2, 2016

10 Nutrient Optimizing Tips for the Primal Enthusiast

You’re reading a blog about nutrition. You’re clicking links to scientific studies and abstracts. You’re in deep. You obviously care about the quality of the food you eat and the effect it has on your health.

But you also know that perfect is a myth. We can’t achieve it, and if we think we can and spend all our time obsessing over perfection, we usually subvert our own goals. Perfection becomes the enemy. But better is always within reach, and today I’m going to give you a few ways to improve your nutrient intake and make your food healthier and safer. Who’s in?

I’ve already discussed optimizing your meat intake and given you tips for cooking eggs. Today will be more far-reaching. Here are 10 tips for quickly and painlessly improving the nutrient quality of your food.

Safer scrambled eggs

Eggs are in many ways the perfect food. Almost every dietary ideology allows their consumption, whether it’s vegetarian, standard American, Primal, or carnivore. Even a low-fatter can slip a few in and stay under the threshold. And I’d argue that vegans should consider raising their own chickens in a loving environment for the eggs.

But what about the oxidized cholesterol? We now know that cholesterol isn’t a bad thing to eat, and it can even provide benefits, but oxidized, fully-damaged cholesterol is an issue. When you scramble an egg, you’re introducing heat and oxygen while increasing the surface area of the yolk exposed to those oxidative forces.

But scrambled eggs are great. And while I’m pretty sure regular scrambled eggs are perfectly fine to eat, there is a better way:

Separate the whites and yolks.

Scramble the whites first.

Once they’re close to finished, add the yolks and briefly scramble.

You get scrambled eggs with runny yolks, intact cholesterol, and fully cooked whites.

More nutritious rice

Years ago, I offered a mea culpa: rice isn’t all that bad actually. In fact, it’s fairly inoffensive, if somewhat lacking in nutrition. Rice can be a useful, safe source of starch for people who need to replenish glycogen stores after a workout. But let’s face it. White rice is basically pure glucose. What if there were a way to dress it up a bit?

Consider this two-parter idea….

First, use mineralized cooking water or bone broth. What I do is dump a half teaspoon to a teaspoon or so of Trace Mineral Drops into the cooking liquid, along with some kelp granules for the iodine (or sometimes a drop of liquid iodine) and a little butter, olive oil, or coconut oil. If you have some leftover mineral water, you can use this too. The end result is high in magnesium, iodine, and various other trace minerals. Most water consumed throughout human history was high in minerals, so this is just emulating that ancestral milieu.

Second, make your rice ahead of time and refrigerate it before use for at least 12 hours. This increases the resistant starch content of the rice. Not to cooked and cooled potato levels, but it’s significant enough to reduce the amount of digestible glucose available.

Low-acrylamide, high-resistant starch fries

French fries are good. Don’t lie, folks. A crispy potato is incredible. But as they’re commonly found, they’re awful for you—the rancid oil used to fry them, the high-heat carcinogens formed, the lack of any fiber at all. Luckily, there’s a way to make healthier, (IMO) better French fries.

Bake, boil, or steam a bunch of potatoes a day in advance.

Peel and refrigerate them overnight in an open container.

Cut into fries.

Sauté in oil of your choice.

Toss in salt, pepper, and any other seasoning you like.

Since they’re already cooked, you just need to sear the sides and develop a crust. You can have crispy, creamy French fries in about 8 minutes (minus the previous day’s cooking time) that haven’t been exposed to enough heat for a long enough time to develop acrylamide and oxidize the cooking fats. Plus, the cooked and cooled potatoes provide resistant starch to feed your gut bacteria and reduce the amount of glucose you absorb.

Instant pan sauce

I love reducing a quart of bone broth down to a syrup, swirling in some cold butter, and making a luscious, velvety sauce as much as anyone, but I don’t always have the time.

Keeping a can of gelatin powder on hand works almost as well. You don’t get the essence of the roasted bones and veggies that go into a good broth, but you do get as much collagen as you want. Just shake a tablespoon or two into the pan in a thin layer across the top as the liquid cooks, and whisk until smooth.

Instant bone broth

Say you’re making clam chowder, and you’ve only got boxed chicken stock. Or you’re doing veggie soup, and all you have is some weird veggie broth. The real thing would be great, but you simply don’t have it. Luckily you do have powdered gelatin.

Mix some powdered gelatin with cold water—enough to bloom it. Let it sit for 5 minutes, and stir it into the hot soup. There: impromptu bone broth.

Save stems and trimmings

Every time you prepare vegetables, you’re throwing stuff away. You’re tossing the ends of asparagus and carrots. You’re eating the leafy part of the kale and discarding the stemmy sections. You’re composting potato peels, onion skins, tomato pith. Stop doing it, and start eating them.

Well, maybe not eat them directly. All those bits contain nutrients, but they’re not exactly appetizing. Freeze all the veggie trimmings as you produce them. If you’re ever making bone broth or soup, bring out the trimmings and add a handful.

Vegetable addiction with fish sauce

Vegetables are some of the only foods everyone can agree on. They’re low-calorie, high-nutrient, high-satiety. Most research has found strong links between their consumption and copious health benefits. “Eat lots of plants and animals,” as I’ve always said. But not everyone likes them (and I’m not just talking about toddlers).

I’ve given tips for learning to eat more vegetables before. Those are good, so you should read them. But there’s another way to make yourself enjoy vegetables (or any food, really): add umami.

Umami is the fifth flavor, providing a kind of meaty unctuousness. That’s the glutamate. To capitalize on it, add a few splashes of high quality fish sauce (I like Red Boat) to anything you want to like more. It adds a depth of flavor to any dish and doesn’t actually taste fishy. Its coolest application, however, may be as a training tool to condition people to like novel flavors. Splashing some fish sauce onto bitter greens can help just about anyone learn to enjoy them, even after the source of glutamate has been removed.

More powerful alliums

Garlic and onion (and, I guess, shallot and leek and the others) are nutrition powerhouses—not so much in terms of vitamins and minerals but because of phytonutrients with remarkable capacities for blocking inflammation and reducing oxidative stress. But there’s a simple recipe to make those phytonutrients even stronger: a little compressive force and a little patience.

Rupturing the cell walls on a clove of garlic or an onion triggers the enzymatic production of new and more potent phytonutrients. The process takes 5-10 minutes, so wait about that long after smashing, chopping, or dicing your alliums to begin eating or cooking with them.

Liver sausage

Liver is the great white whale for many Primal eaters. They know they’re supposed to be eating it, but they can’t figure out how. I understand. Liver goes bad pretty quickly in the fridge. It’s tricky to cook without ruining the texture. It’s messy. That’s why you should let someone else handle it for you.

Next time you’re at your local butcher, ask if they’ll make a custom set of sausages that contain liver for you. In my experience, they will. I recommend a pork breakfast sausage with 20% chicken liver subbed in for some of the pork meat. That’s an easy way to get your liver, and chicken liver is mild enough that you probably won’t notice.

Prefer lamb? Have them slip 15% lamb liver into merguez sausage. Beef? Do 15% beef liver within a spicy Italian sausage. And so on.

Offer to buy in bulk (say, 10 pounds or so), and they’ll likely accommodate the request.

Yolks as thickeners

Ounce for ounce, egg yolks trump all other sources of fat when it comes to nutrient density. There simply isn’t any other argument. But yolks aren’t as easy to use as, say, olive or avocado oil. You can’t sauté in egg yolk. You can’t just pop one out of the fridge and eat it.

One of my favorite ways to incorporate more yolks into my diet is to add them to sauces and curries at the end of cooking. The lecithin contained in the yolk is a great thickener. You’re getting tons of nutrients without subjecting the yolk to an hour of cooking, and it lends a velvety richness.

Two yolks added to your tomato basil spaghetti sauce after it comes off the heat? Incredible.

So, those are my 10 tips for general nutrition improvement today. What about you? How have you learned to enhance or preserve the nutrient content of your Primal meals?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care.

The post 10 Nutrient Optimizing Tips for the Primal Enthusiast appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

November 1, 2016

Why the Blood-Brain Barrier Is So Critical (and How to Maintain It)

You all know about intestinal permeability, or “leaky gut.” The job of the gut lining is to be selectively permeable, allowing helpful things passage into the body and preventing harmful things from getting in. Nutrients get through, toxins and pathogens do not. Leaky gut describes the failure of this vetting process. But what about “leaky brain”?

You all know about intestinal permeability, or “leaky gut.” The job of the gut lining is to be selectively permeable, allowing helpful things passage into the body and preventing harmful things from getting in. Nutrients get through, toxins and pathogens do not. Leaky gut describes the failure of this vetting process. But what about “leaky brain”?

A similarly dynamic barrier lies between the brain and the rest of the body: the blood-brain barrier. Since the brain is the seat of all the conscious machinations and subconscious processes that comprise human existence, anything attempting entry receives severe scrutiny. We want to admit glucose, amino acids, fat-soluble nutrients, and ketones. We want to reject toxins, pathogens, and errant immune cells. Think of the blood-brain barrier like the cordon of guards keeping the drunken rabble from spilling over into the VIP room in a nightclub.

The blood-brain barrier (or BBB) can get leaky, just like the gut lining. This is bad.

A compromised BBB has been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and vascular dementia.

More generally, the BBB regulates passage of inflammatory cytokines into the brain, prevents fluctuations in serum composition from affecting brain levels, and protects against environmental toxins and infectious pathogens from reaching the brain. A leaky BBB means the floodgates are open for all manner of unpleasantries to enter the brain.

Some pathogens even wield chemical weaponry that blasts open the blood-brain barrier, giving them—and anything else in the vicinity—access to the brain. To prepare for that, you must support the integrity of your blood-brain barrier.

How?

Optimize your B vitamin intake

In adults with normal B vitamin levels, mild cognitive impairment, high homocysteine levels, and a leaky BBB, taking vitamins B12, B6, and B9 (folate) restored the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.

Review this post and make sure you’re getting the B vitamins you need. Primal folks tend to overlook them.

Nourish your gut

A leaky gut accompanies, and maybe causes, a leaky brain. Funny how that works, eh?

It’s a rodent study, but it’s quite illustrative: a fecal transplant from healthy mice with pristine BBB integrity to unhealthy mice with leaky BBB and pathogen-filled guts restored the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.

DIY fecal transplants are an extreme intervention. Until that becomes more feasible, simply eating more prebiotic fiber, experimenting with resistant starch, taking a quality probiotic, and eating fermented foods on a regular basis will get you most of the way there.

Eat plenty of magnesium

Okay, Sisson. Enough already with the magnesium. We get it! But magnesium can attenuate BBB permeability, even if you inject an agent explicitly designed to induce leaky blood-brain barriers.

This is yet another reason to eat enough magnesium-rich foods (like spinach, almonds, blackstrap molasses, winter squash), drink magnesium-rich mineral water (I love Gerolsteiner, but you can also just go down to the local Euro food market and check the labels for high-Mg waters), or take a good magnesium supplement (anything ending in “-ate” like magnesium glycinate or citrate).

Don’t eat a 40% cocoa butter diet

Rodents given a 40% saturated fat (from cocoa butter) diet experienced elevated BBB permeability.

Except wait: The remaining 60% of calories was split up between white sugar, wheat starch, casein, and dextrin (PDF). So this isn’t the type of 40% SFA diet you folks are eating.

Except wait again: Adding in either aged garlic extract, alpha lipoic acid (ALA), niacin, or nicotinamide completely abolished the increase in permeability.

It looks like a refined diet high in saturated fat and sugar/starch and absent any phytonutrient-rich plant foods like garlic or antioxidant supplements like ALA will cause elevated BBB permeability (in rodents). I’m not sure I’d recommend a 40% SFA diet either way, however. Balance is probably better.

Use phytonutrient-rich plants and spices

Recall the study from the last section where some garlic extract was enough to eliminate the bad BBB effects of a refined lab diet. That’s because aged garlic extract is particularly rich in phytonutrients with strong antioxidant effects. What about other fruits, vegetables, and spices with different phytonutrients—do those also help BBB function?

Curcumin (from turmeric) certainly helps. Astragalus root, used in many ancient medical traditions, can help. Sulforaphane, from cruciferous veggies like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage, shows promise.

Drink coffee and/or tea

As phytonutrient-rich plants, they technically belong in the previous section, but coffee and tea are so special that they deserve their own space. Both are sources of caffeine, a noted protector of BBB integrity.

Supplements can help

Supplement forms of the aforementioned nutrients are worth a look. Also:

Alpha-GPC (a type of choline that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier) has been shown to reduce BBB permeability in hypertensive rats.

Inositol (which you can get from foods like egg yolks but not in very large amounts) improves BBB integrity. Another option is to consume phytate-containing foods; if you’ve got the right gut bacteria, you can convert phytate into inositol.

Berberine, noted anti-diabetic compound, reduces BBB permeability and increases resistance to brain damage following head trauma.

Control your blood pressure

Both acute and chronic hypertension increase BBB permeability. This means you’ll have to control your sleep and stress. You’ll need to reduce insulin resistance. Eat dark chocolate (the horror). Figure out if you’re salt-sensitive (you may even have to increase salt intake if it’s too low). Get enough magnesium (yes, again) and potassium.

Sleep

Sleep really is everything. You can’t avoid it, and if you skimp on it, things fall apart. The blood-brain barrier is no exception: sleep restriction impairs BBB function and increases permeability.

If you can’t stick to the bedtime you know is ideal, a little (0.25-0.5mg) melatonin can help set your circadian rhythm. Plus, supplementary melatonin may also preserve BBB integrity.

Don’t drink too much alcohol

Alcohol is a tough one. While I just wrote a big post explaining the merits of wine consumption, ethanol is undoubtedly a poison in high doses, and I derived real benefits when I gave it up for a few months. One way alcohol exerts its negative effects is by inducing BBB dysfunction. This allows both the pleasant effects of alcohol (low-dose ethanol migrating across the BBB and directly interacting with neurons, triggering endorphins and interacting with GABA receptors) and the negative effects (high-dose ethanol migrating across the BBB to damage the neurons, leaving the door open long enough for immune cells to sneak in and cause all sorts of trouble).

Stimulate your vagal nerve

After a traumatic brain injury or stroke, the resultant increase in BBB permeability floods the brain with inflammatory cytokines, causes swelling and neuronal death, and worsens the prognosis. Stimulating the vagal nerve after such an injury decreases the BBB permeability and improves the prognosis.

One treatment for epilepsy is to wear vagal nerve stimulators which send light electronic pulses to the nerve, akin to a pacemaker for the brain. Easier options include humming, cold water exposure (even just splashing the face can help), singing, chanting, meditating, deep breathing, coughing, moving your bowels (or summoning the same abdominal pressure required for said movement; girding your core for a heavy squat or deadlift should also work along the same lines), and many more.

Perhaps an entire post on the vagal nerve is in order. It’s an interesting area that impacts more than just the BBB.

Stop eating so often

Ghrelin is the hunger hormone. When you haven’t eaten in a while, ghrelin tells you that it’s time to eat. It also increases blood-brain barrier stability after (again) a traumatic brain injury.

So, never eat? No. But make sure to feel actual hunger. It’s the best spice, and it confers a whole host of other benefits, including better blood-brain barrier function. Heck, try intermittent fasting for the ultimate boost to ghrelin.

You might notice that a lot of the studies I cite involve traumatic brain injuries to rodents. Dropping a weight on a rat’s head or triggering a stroke in a mouse are two of the most reliable ways to induce BBB permeability. Brain injuries are also quite common in humans, and the BBB permeability that results is a major therapeutic target, but we can’t study it so easily in people. While acute and chronic BBB permeability are different beasts, and mice are not men, they operate along the same rough pathway.

That’s about it for today, folks. I hope you feel encouraged and able to fortify your blood-brain barrier. Don’t wait for cognitive decline to set in. Get started now.

How do you improve the integrity of your blood-brain barrier? Have you even considered it prior to today?

Thanks for reading!

The post Why the Blood-Brain Barrier Is So Critical (and How to Maintain It) appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 31, 2016

Dear Mark: Social Contact and Neuroplasticity; Extra Protein and Muscle Gain

As you all know, one of my favorite parts of doing this blog is the constant, unyielding, uncompromising feedback I get from readers. When I make a mistake, or overlook a crucial piece of a puzzle, someone tells me where I went wrong or provides that missing piece. For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’ll be addressing two emails from readers who took me to task for things I missed on this week’s posts.

As you all know, one of my favorite parts of doing this blog is the constant, unyielding, uncompromising feedback I get from readers. When I make a mistake, or overlook a crucial piece of a puzzle, someone tells me where I went wrong or provides that missing piece. For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’ll be addressing two emails from readers who took me to task for things I missed on this week’s posts.

The first comes from Simon, who had a great suggestion for increasing neuroplasticity. The second comes from Jen, who highlighted a new study shedding light on the effect of extra protein on muscle gains.

Let’s go:

Mark,

I really liked your post on neuroplasticity, but I think you may have missed a big one: socializing!

Simon

This makes sense on an intuitive level. When you’re alone, you control the environmental inputs. You can expose yourself to novel situations and inputs, but you’re the primary arbiter. It’s a curated experience.

Adding one, two, or several more big-brained hominids (or an entire party full of them) who can think and talk for themselves catapults you into new strata of novelty. Spending time with other members of the most intelligent species on earth can be intense.

You’re not reacting to a static novelty input, like a new route home or a beautiful piece of art you’ve never seen before. You’re responding to another living, breathing mind who challenges you.

You’re not analyzing a character in a novel or movie. You have to exercise empathy, to place yourself in another person’s shoes (and head) to maintain real communication.

Keeping up with other people requires mental agility. I’m thinking that has to induce some profound neuroplasticity. So, what does the research say?

We know that social isolation turns off genes related to neuroplasticity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus—at least in rodents.

Chronic social isolation also causes depressive-like symptoms while reducing neuroplasticity.

We’ve all heard of oxytocin, the “love” hormone. Perhaps a more accurate description is “socializing” hormone. Hanging out with other people increases secretion of oxytocin partially to increase pleasure and promote socializing, actually triggering the release of endogenous cannabinoids. A good laugh with friends really can leave us feeling high as a kite.

But oxytocin also helps us tune into the emotional cues and body language others give off, determine friend from foe, and respond accordingly. In animals, it has also been shown to mediate certain types of neuroplasticity, particularly in instances of sensory deprivation. It’s almost like the body “knows” that socializing with other humans requires a nimble mind able to make new connections in the brain.

Great suggestion, Simon!

Hey Mark,

Any thoughts on this paper? Made me think of your post from the other day on lowering protein or not.

Jen

Here’s the paper. They took weightlifting novices—people who hadn’t lifted regularly for the past 2 years but who did regularly play team sports—split them up into a high-protein group (1.8 g/kg per day) and a normal-protein group (0.85 g/kg per day), and placed them on identical training regimens for 8 weeks.

They did bench press, shoulder press, lying shoulder extensions, seated rows, lat pull downs, and bicep hammer curls. They totally skipped leg day, in other words.

To hit 1.8 g/kg protein per day, the high-protein group used whey protein on top of their regular food. The normal-protein group got a non-caloric placebo drink.

Focusing on the latissimus dorsi (the “wings”), the researchers found that both groups experienced similar gains in size and strength. Extra protein had no effect on either.

Why the latissimus dorsi? For one, it hadn’t been studied much in this context, despite being the largest muscle in the human body. The second reason they chose it was “its relevance in many athletic gestures.” I can only assume they’re referring to the fist pump.

They also took a biopsy of the lats to analyze the effect the different protocols had on muscle fiber distribution. Normally, sticking with a resistance training program increases conversion of type 2x (super fast twitch, maximal force production, burns through energy) fibers into type 2A (fast twitch, less force production than 2x but more endurance). This indicates that your muscles are gaining metabolic efficiency. What once required super fast twitch fibers and maximal effort no longer does.

The high protein diet blunted the conversion, retaining more type 2x fibers. Is this good or bad?

It depends.

More 2x fibers mean greater capacity for truly explosive movements. These are useful for power sports, sprints, weight lifting, and other activities requiring all-out max efforts. If those are the types of activities you enjoy, eating a bit more protein may help retain them.

More 2A fibers mean a greater capacity for strength-endurance. You can still go hard and heavy, but you’ll last a bit longer. These are important for athletes who engage in strength-endurance activities like cycling.

Realize that these are probably very small differences. When you get down into the weeds like this, mucking around with fiber types, you’ll see marginal returns. It’s important to keep an eye on the big picture: Eating more than double the protein improved neither size nor strength.

Does this mean you should definitely eat 0.8g/kg protein per day? No. Like I said in last week’s post, experiment. Try going lower in protein, just to see if you can get away with it and save money (protein is expensive, especially the high-quality stuff) while preserving your performance and body composition. Maybe you can’t, and higher protein just works better. That’s fine too.

Just another thing to file away for later consideration.

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

The post Dear Mark: Social Contact and Neuroplasticity; Extra Protein and Muscle Gain appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 30, 2016

Weekend Link Love – Edition 424

Research of the Week

Research of the WeekHigh-protein diet causes remission from pre-diabetes to normal glucose tolerance; isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet does not.

Fasted morning exercise reduces 24-hour food intake and increases fat burning.

Natural birth prepares a newborn’s liver to metabolize fats.

Our understanding of ancient human history is still in flux.

Formula spiked with L. reuteri DSM 17938 makes the gut biomes of C-section babies resemble those of vaginally-born babies.

Converting cropland to intensively-grazed (by evil livestock, no less) pastureland “rapidly” increases soil carbon.

Men who work in the sun get less prostate cancer. Women who work in the sun get none.

How genes can predict optimal rep range.

New Primal Blueprint Podcasts

Episode 140: Gary Foresman, MD: Host Elle Russ chats with Dr. Foresman about general breast health.

Each week, select Mark’s Daily Apple blog posts are prepared as Primal Blueprint Podcasts. Need to catch up on reading, but don’t have the time? Prefer to listen to articles while on the go? Check out the new blog post podcasts below, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast here so you never miss an episode.

Should You Eat Less Protein?

7 Primal Ways to Bridge the Parent Happiness Gap

The Benefits of Caloric Efficiency (and 10 Ways to Achieve It)

Interesting Blog Posts

Media, Schmedia

Earlier this month, Soylent had to recall their new food bars because they were making people sick. Now, Soylent’s pulling their flagship powder for the same reason.

Framing healthy eating as “rebellion” makes teens more likely to do it.

Everything Else

A bookstore in Cairo has a “scream room” where customers can vent their frustration at life, the universe, and everything.

Australian wine researchers are exploring ancient Aboriginal fermented beverages.

I’d love to see the nutrient profile of seaweed-fed meat and dairy.

Can consumer demand for camel milk revitalize India’s semi-nomadic camel herders?

I know what I’m eating for lunch today.

Things I’m Up to and Interested In

Video I’m watching: “Why We Get Sad: How Evolution Makes Sense of Emotional Disorders.”

Product I’m excited about: Primal Kitchen Ranch Dressing is finally real, and it’s spectacular. The team and I have been sucking down the various iterations of this stuff for the better part of a year, and now you can join the fun!

Tweet I’m pondering: “At Netflix, we are competing for our customers’ time, so our competitors include Snapchat, YouTube, sleep, etc.”

Podcast I can’t wait to listen to: Joe Rogan chats with Wim Hof, the Iceman.

Turn of phrase I enjoyed: “Test-marketing new fears.”

Recipe Corner

Cantonese crispy chicken thighs. Nom Nom Paleo’s stuff is always great.

Beet hummus beats hummus.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Oct 30 – Nov 5)

5 Things You Learn Being a Primal Lifer – Wisdom only years in the trenches (and, maybe, this blog post) can reveal.

Stop Saying No, Start Saying Yes! – Shift your frame of mind.

Comment of the Week

“My amygdala (lizard brain) makes me crave insets. No crickets around my house.”

– There’s one way to avoid insecticides. Thanks, Nocona.

The post Weekend Link Love – Edition 424 appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 29, 2016

Tapioca Crepes

Tapioca crepes are a popular food in Brazil that just happens to also be Primal and paleo friendly. Made from tapioca flour, these crepes are naturally gluten-free. They have a completely neutral flavor that works with both sweet and savory fillings. Often eaten for breakfast or for a snack, the crepes can be filled with scrambled eggs, shredded meat, avocado and lox, roasted vegetables and pesto, fresh berries, or melted dark chocolate.

Tapioca crepes are a popular food in Brazil that just happens to also be Primal and paleo friendly. Made from tapioca flour, these crepes are naturally gluten-free. They have a completely neutral flavor that works with both sweet and savory fillings. Often eaten for breakfast or for a snack, the crepes can be filled with scrambled eggs, shredded meat, avocado and lox, roasted vegetables and pesto, fresh berries, or melted dark chocolate.

Basically, tapioca crepes are an edible container for just about anything.

These crepes are thin and light with a chewy texture and crispy edges. The technique for making the crepes can take a little practice to perfect, but it’s very straightforward: moistened tapioca flour is sifted into a dry, hot pan and in less than a minute, the flour melds together into a crepe. Spreading salted butter onto the crepe as soon as it comes out of the pan adds more flavor, for both sweet and savory fillings.

Tapioca flour, also called tapioca starch, is extracted from the root of the cassava plant. Tapioca flour is popular in Brazil partly because cassava is a native shrub that grows abundantly in South America (as opposed to wheat, which can be difficult to grow in parts of Brazil due to regional climate and poor soil quality)

Tapioca flour, however, is not the same as cassava flour. As noted above, tapioca flour is starch that is extracted from the cassava root. Cassava flour is made from the root itself after it’s peeled, dried, and ground. The two flours are not interchangeable in recipes.

Curious about what crepes made from cassava flour look and taste like? Enjoy these tapioca crepes first, then check back next week for a cassava flour recipe.

Servings: 4

Time in the Kitchen: 20 minutes

Ingredients

1 cup tapioca flour (100 g)

1/4 cup water (approximately) (60 ml)

Tools

Fine mesh strainer

8-inch/20 cm non-stick skillet

Recipe Note: Tapioca flour varies in its absorption capabilities, so the exact amount of water needed will vary depending on the brand of tapioca flour. Start with ¼ cup/60 ml water, and add more if needed. Water is not added to create runny batter, it’s used simply to hydrate the flour so that it’s moist enough to form clumps. If too much water is added, the tapioca flour will become simultaneously runny and sticky like glue. If this happens, add more flour until the texture is once again moist and clumpy, not runny.

Instructions

In a medium bowl, slowly drizzle the water into the tapioca flour while mixing with your fingers. Clumps will form that you can break up with your fingers, giving the flour the texture of streusel.

Using your fingers or a spoon, press the tapioca flour through a mesh strainer into a bowl. The texture of the tapioca flour will now be very delicate and light. (If the mesh strainer is too fine, it will be harder and more time consuming to press the flour through)

Heat an 8-inch/20 cm non-stick skillet over medium heat. Sprinkle a very thin, even layer of the tapioca flour into the pan. After about 30 seconds, the tapioca flour should be sticking together into a crepe that can be flipped. Flip it over, and cook the other side 30 seconds more.

Tapioca crepes taste best while still warm. Spread salted butter over one side, and wrap the crepe around the filling of your choice.

Filling Suggestions:

Scrambled eggs

Shredded or ground meat

Roasted vegetables and pesto

Lox and avocado

Berries

Coconut flakes

Dark chocolate

The post Tapioca Crepes appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 28, 2016

How I Lost over 100 Pounds—and Gained Strength, Stamina and Control

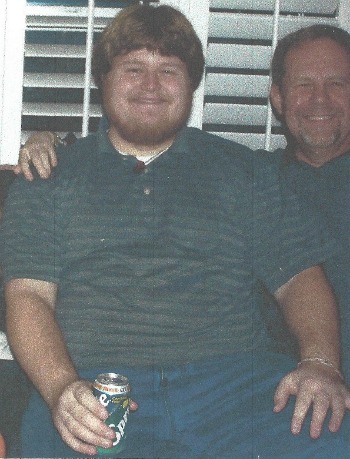

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. In fact, I have a contest going right now. So if you have a story to share, no matter how big or how small, you’ll be in the running to win a big prize. Read more here.

I was always fat. No, seriously. My whole life, I was fat. In middle school I was around 160-180 pounds. In high school I hit 250 pounds. At my heaviest, a few years after college, I was 330 pounds. I never liked how I looked or how I felt. I didn’t like that I would get exhausted easily. I didn’t like that I would get injured easily and be sore. I didn’t like that I could be basically danced around in sporting events because I was so big and clumsy that I couldn’t move. I didn’t like the constant bloated feeling. I didn’t like being dateless.

I occasionally tried to get away from my soda and fast food diet, eating the standard American “healthy” diet of low fat, low calorie, whole grain diet with heavy exercise, and would sometimes have short term positive results, but I would be constantly hungry, unsatisfied, and get injuries which would derail my progress. A few months later, the weight and poor eating habits were back.

To be fair, the start of my turn around was because my wife was diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder. She did a lot of research, read a lot of books and blogs, and we tried a variety of different foods before we found that eating essentially Primal/paleo was easiest for her stomach. We read your blog, the Primal Blueprint, (and other sources) and have been eating this way for about 3+ years now.

After that first few weeks of adjustment, it’s been amazing. I feel constantly great, and I never worry about portion control or calories. I just let my body tell me how much food I need. When coworkers bring in cakes or donuts, I can smell the sugar a room away, but don’t crave it. It usually smells like chemicals as much as sugar if that makes sense. Coworkers marvel at my change, and people whom I haven’t seen for years literally don’t recognize me.

The most difficult part of the change was the fact that cooking is an integral part of our life, and is, I guess, our biggest hobby at this point. We buy beef a quarter cow at a time (grass fed and finished of course) and pork a half-pig at a time (pastured). We cook most of our meals for the month over one incredibly long weekend, and freeze them to make weeknights easier. There are days when work stress makes the convenience of easily picked up drive-thru meals tempting, but the extra effort is worth it.

The Primal lifestyle has also affected the way I work out and train. I’m a 2nd degree blackbelt in taekwondo, and am known around the dojang as the guy with crazy stamina, strength and speed. I used to be known as the big guy who could kick hard with no balance, control, or stamina. For a while, to get in shape, I was going into the dojang on my own, jumping rope and doing all sorts of crazy extra work for 2-2.5 hours at a time. While my stamina did increase, I was often too physically drained for days, and sometimes my knees barked. Now when I train, though we focus a ton on fundamentals, (footwork, balance, basics) I see the training as fun or play. Cardio, footwork, and complex kicking drills are like dancing, and I often find myself smiling after a particularly challenging drill while others are panting. Trying something new is an exploration of balance and joint strength that I enjoy! I have even better stamina, even though I’ve cut out the crazy extra workouts.

The Primal lifestyle has also affected the way I work out and train. I’m a 2nd degree blackbelt in taekwondo, and am known around the dojang as the guy with crazy stamina, strength and speed. I used to be known as the big guy who could kick hard with no balance, control, or stamina. For a while, to get in shape, I was going into the dojang on my own, jumping rope and doing all sorts of crazy extra work for 2-2.5 hours at a time. While my stamina did increase, I was often too physically drained for days, and sometimes my knees barked. Now when I train, though we focus a ton on fundamentals, (footwork, balance, basics) I see the training as fun or play. Cardio, footwork, and complex kicking drills are like dancing, and I often find myself smiling after a particularly challenging drill while others are panting. Trying something new is an exploration of balance and joint strength that I enjoy! I have even better stamina, even though I’ve cut out the crazy extra workouts.

I also wanted to start some strength training recently as I had never done a pull up. I could barely lift myself at all when hanging from a bar. I also struggled with pushups and core strength. After a lot of books and blogs, and influenced by the Primal lifestyle, I decided on basic bodyweight training because it emphasized natural human movements more closely connected with how the body evolved to function. My work consists of variations on pushups, pull ups, leg raises and squats, starting with simple, assisted versions, and increasing in difficulty as I build strength. The training doesn’t take long, and if my body is tired, I’ll work just once a week. If I’m feeling great, I’ll go twice. While others I know have constant injuries and inflamation problems from their weight lifting (and their grain intense diet I’m sure), I’m still injury free, and am happy to report that just this week, after about 10 months of consistent work, I completed my first three pull ups ever! I’m also moving towards one-legged squats, and am getting closer to good, perfect form pushups. As for core work, I started barely able to hold a plank for 20 seconds. As for now, well, I was playing basketball with some coworkers a couple of months ago, and a coworker injured his hand against my stomach when we both went for a rebound. I didn’t even feel it.

I also wanted to start some strength training recently as I had never done a pull up. I could barely lift myself at all when hanging from a bar. I also struggled with pushups and core strength. After a lot of books and blogs, and influenced by the Primal lifestyle, I decided on basic bodyweight training because it emphasized natural human movements more closely connected with how the body evolved to function. My work consists of variations on pushups, pull ups, leg raises and squats, starting with simple, assisted versions, and increasing in difficulty as I build strength. The training doesn’t take long, and if my body is tired, I’ll work just once a week. If I’m feeling great, I’ll go twice. While others I know have constant injuries and inflamation problems from their weight lifting (and their grain intense diet I’m sure), I’m still injury free, and am happy to report that just this week, after about 10 months of consistent work, I completed my first three pull ups ever! I’m also moving towards one-legged squats, and am getting closer to good, perfect form pushups. As for core work, I started barely able to hold a plank for 20 seconds. As for now, well, I was playing basketball with some coworkers a couple of months ago, and a coworker injured his hand against my stomach when we both went for a rebound. I didn’t even feel it.

As for that weight, I’m now 200 pounds, which for my height, 6’3″, is great. The weight just kept sliding off with seemingly no effort. I’m in fantastic shape. I’m in my mid 30s, and I have no trouble competing against (and defeating) kids in their early 20s. I also have a sense of self control over my body that feels amazing. I’m no longer clumsy, but am graceful! I feel like I can do anything I put my mind towards, and the physical change has made me more confident, happy, and mentally resilient.

Grok on!!!

The post How I Lost over 100 Pounds—and Gained Strength, Stamina and Control appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 27, 2016

It’s Here Early! Grab Your Calendar Today and Get Four Free Gifts!

I’ve been writing a blog a day for the last decade, and I’m not gonna stop. But I was thinking, what about those days when my readers don’t have a full few minutes to read through an entire post? I can still reach and inspire on a limited word count, right? That impetus spawned the creation of Primal Blueprint’s latest publication: The Primal Blueprint Day-to-Day 2017 Calendar. We just got a limited shipment in, so I wanted to tell all my Mark’s Daily Apple readers about it in case you’d like to order the calendar in plenty of time for 2017.

I’ve been writing a blog a day for the last decade, and I’m not gonna stop. But I was thinking, what about those days when my readers don’t have a full few minutes to read through an entire post? I can still reach and inspire on a limited word count, right? That impetus spawned the creation of Primal Blueprint’s latest publication: The Primal Blueprint Day-to-Day 2017 Calendar. We just got a limited shipment in, so I wanted to tell all my Mark’s Daily Apple readers about it in case you’d like to order the calendar in plenty of time for 2017.

Each month is inspired by a Primal Blueprint lifestyle law or Primal Connection law. For instance, we start January with Law #1 Eat Lots of Plants and Animals, and each day of the week reflects that law with a recipe, an exercise, a nature connection, or an activity that helps you de-stress and recalibrate to primal balance. It’s a terrific resource of easily digestible daily tidbits to keep you focused, inspired, and enlightened with primal information.

We formatted the calendar as a desk calendar—a five-inch square pad rests on a plastic base that you can lay flat or prop up. Many of the days are jam-packed with succinct messages about vitamin D health, the Primal Essential Movements, the psychological benefits of play, the hormonal aspects of fat adaptation, the physical and psychological benefits of spending time in nature or limiting use of digital technology, and so forth. These educational offerings are interspersed with inspirational quotes, recipes, and quick de-stressing tips—all honoring the monthly themes to get you into a good reading rhythm and diverse and fresh experience every time you peel back a new page. You can peel off your favorite workout or recipe tips and stick ‘em on the fridge!

The calendar also serves as a great introduction to primal living by providing simple, bite-sized inspirations and practical tips one day at a time, so consider gifting the calendar and turning someone you care about on to primal.

I’m in a gifting mood myself, so if you order The Primal Blueprint Day-to-Day 2017 Calendar by November 3rd at midnight, I’ll throw in three of Primal Blueprint’s most recent and popular publications. The Primal Blueprint Cookbook, The Definitive Guide to Troubleshooting Weight Loss, and 6 Foods You Should Be Eating for a Healthy Gut.

In case you’re not familiar, here’s a back cover blurb for each.

The Primal Blueprint Cookbook

I wrote this innovative cookbook with acclaimed chef/food writer/photographer Jennifer Meier. It includes over 100 mouth-watering recipes with easy-to-follow instructions and nearly 400 brilliant full-color photographs to guide and inspire you to primal cooking heights. Save time with intuitive recipe steps, easy navigation, and great visual support. I published The Primal Blueprint Cookbook in 2010, and it still takes up prime real estate in my kitchen.

The Definitive Guide to Troubleshooting Weight Loss

Weight loss stalls are a huge issue for people. If you type “weight loss p” into Google, the first autofill suggestion is “plateau.” So in this eBook I provide a simple framework for tackling weight loss plateaus and slowdowns by explaining the 23 weight loss stumbling blocks that most frequently trip people up (and how to overcome each one)…describing the eight most common weight loss plateau archetypes (and how to figure out which one you are)…and showing you how to construct a weight loss plan that will work for you.

6 Foods You Should Be Eating for a Healthy Gut

Your gut is your body’s second brain. It is inextricably linked to your moods, your immune system, your skin health, your ability to lose weight…virtually every component of your body in some way depends on a healthy gut. Here I spill the secrets to a happy digestive system. You’ll learn about your gut’s microbiome and how to keep it thriving, 6 of the best foods for gut health, 3 foods you should never eat, the dietary pattern to avoid at all costs, and much more!

Okay, I’ll thrown in one more freebie. How about a 20% off coupon for your next order on PrimalBlueprint.com?

The coupon alone can pay for the calendar in savings depending on what you order. The coupon isn’t valid on digital products, but it’s good for anything else at our online store.

(Offer expires November 3rd at midnight.)

Looking forward to inspiring you every day of next year and beyond.

The post It’s Here Early! Grab Your Calendar Today and Get Four Free Gifts! appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 26, 2016

16 Ways to Increase Neuroplasticity (and Why That’s Important)

For hundreds of years, the localizationism theory of the brain reigned: the idea that the adult brain is composed of distinct regions, each responsible for a separate function. Most people still hew to this, assuming that vision goes here, memories there (with separate sections for short and long term memories), smell here, verbal fluency over here and quantitative processing over there. We assume the number of neurons is fixed and their wiring soldered.

But the emerging science of neuroplasticity shows how wrong this is: rather than fixed and immutable, the neural connections between different “regions” of the brain can reorganize themselves. This is why someone with brain damage to one part of the brain can often recover—neuroplasticity allows a healthy section to assume the role of the damaged section. It’s also how we learn, form memories, and develop new skills.

Neuroplasticity can refer to the strengthening (or lessening) of existing neuronal pathways (synaptic plasticity), or the establishment of entirely new neurons and connections (structural plasticity).

Cool. So neuroplasticity exists. What’s it good for, and why should we care about preserving or enhancing it?

Most neurodegenerative diseases are accompanied by a loss of neuroplasticity, including Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Schizophrenia may actually be a “disorder of neuroplasticity.” Loss of neuroplasticity even characterizes mild cognitive impairment. It may very well be the case that the aging brain is a less plastic brain. If we can enhance neuroplasticity or hold back its degradation, perhaps we can mitigate the scariest effect of aging: the loss of cognitive function.

Neuroplasticity isn’t wholly good, of course. Depression is often associated with negative neuroplasticity—plasticity that establishes unpleasant thought patterns, not beneficial ones.

Ultimately, neuroplasticity allows us to adapt, to respond, to evolve in real time to a changing environment. Want to get rid of bad habits and establish good ones? Want to acquire a new skill? Want to remain cognitively fluid and mentally limber as you age?

You’d better support healthy brain plasticity.

One way is to provide the basic substrates required for maintenance of neuroplasticity. Lacking them will definitely impair our ability to grow new neurons, establish new connections, and strengthen existing ones.

Another major mediator of plasticity is brain derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, which regulates axonal growth and remodeling, as well as synapse formation and function. Axons are the (relatively) long, slender structures linking two neurons together; synapses are the junctions where axons connect to neurons. BDNF is remarkably “activity-dependent,” meaning we can affect its expression by performing certain behaviors.

So what does this all look like?

Get enough magnesium.

You know how any article about magnesium begins with something about how it’s “involved in over 400 physiological functions”? Neuroplasticity is one of them. Giving rats magnesium threonate increased synaptic plasticity and the number of synaptic connections, and it improved cognitive performance on tests of spatial and associative memory. Magnesium also increases plasticity in the visual cortex of mice.

Human studies are scant, but we do know that Alzheimer’s patients have lower brain levels of magnesium, which jibes with the animal research.

Get enough choline (and maybe supplement with specific forms).

We use choline to produce acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter required for neuronal plasticity. Two forms of choline in particular—CDP choline and Alpha-GPC—have been shown to increase brain plasticity following stroke.

Don’t sell pastured egg yolks short though. While they may not contain as much concentrated choline as the supplements, they are the richest natural source and contain many other brain-friendly nutrients (selenium, cholesterol, DHA).

Sleep.

Sleep might be the most essential nutrient for neuroplasticity. The sleep deprived brain is hyperconnected. It’s muddled with connections, dense with nervous information. Sleep restores that. Sleep provides a soft wipe of the brain, giving you the opening necessary to lay down new connections, form new memories, and learn new skills.

Eat fish.

Animal studies reveal that omega-3 fats enhance neurogenesis in the hippocampus, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation of learned behaviors. As for humans, seafood intake is consistently linked to lower rates of two of the conditions that brain plasticity protects against—depression/suicidal ideation and mild cognitive impairment.

Eat turmeric (or use curcumin).

In rats with depression, curcumin improves neuronal plasticity while reducing the depressive symptoms. In humans with major depressive disorder, curcumin reduces depressive symptoms. While the human evidence remains circumstantial, I’m confident that turmeric/curcumin can aid neuroplasticity.

Move frequently at a slow pace.

Compared to strength training, aerobic training is a far more potent booster of BDNF. A rat study even showed how running can inhibit the depression of neuroplasticity that usually occurs after a stroke.

That’s not to suggest resistance training is useless for cognitive function. In fact, a recent paper found that strength gains, but not aerobic gains, in response to training were associated with cognitive improvements in mild cognitive impairment.

Sprint.

Sprinting is an even better way to boost BDNF. Sprinters have high basal levels of BDNF, with elite international sprinters having higher levels than amateurs.

Go hard.

Intensity seems to be the key mediator of exercise-induced BDNF increases.

I’d imagine anything of sufficient intensity will do the trick: a CrossFit WOD, a 20 rep set of squats, playing Ultimate frisbee, a few barbell complexes, several sets of burpees, or anything from this post.

Go fast.

I don’t mean “go quickly.” I mean go without food for 12-24 hours, AKA intermittent fast. Fasting is a sure-fire way to increase BDNF levels.

Bonus: fasting also increases neuronal autophagy.

Mitigate stress.

Stress dampens neuroplasticity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex while increasing it in the amygdala (our “lizard brain” associated with fear, anger, anxiety, and other autonomic emotional responses).

Stress will happen. What matters is our response to it and whether we mitigate its damage.

Most of this is laying the foundation for healthy brain function with the necessary nutrients, training inputs, sleep, and lifestyle factors—so you can take advantage of the brain’s natural plasticity.

But you still need to take action, try new things, and exercise that plasticity. What are some ideas?

Grease the groove.

Choose an exercise, like the pullup. Pretty much whenever you get a chance to do the movement, you do it. You might do five or six pullups every time you see the pullup bar, ten times a day perhaps (or more!). So by the end of the day you’ve done fifty to sixty pullups without having to grind any of the reps out. Each rep is crisp and clean, and you never go to failure.

You’re building new neuronal pathways for that movement when you perform it frequently without excess strain and stress.

Seek novelty.

Following the same routine everyday reduces the metabolic costs of experiencing and perceiving it. This is good for base survival, but it also means our brains aren’t working very hard. If you seek novelty—take a different path to work, try something new and maybe scary, visit a different part of town, try a new restaurant—you’ll be less efficient, but your brain will establish new pathways.

Humans are already novelty seekers, and for good reason: it’s how we learn, experience, and ultimately live most fully in the moment.

Learn an instrument.

Music training has profound effects on neuroplasticity.

Tackle a difficult—yet interesting—subject.

Do a deep dive into a subject that interests you. Read a book, take an online course, attend a class, go to a seminar, learn to code. Make sure it takes actual effort, but don’t let difficulty be the sole criterion. Engagement is just as important.

Learn a language.

There’s no better way to test and train your neuroplasticity than learning an entirely new form of communication.

Try psilocybin (when legal).

Research shows that psilocybin’s enhancement of neuroplasticity explains why it reduces depression and extinguishes conditioned fear. It also reduces reactivity (negative plasticity) in the amygdala and improves well being (positive plasticity).

It’s still illegal, but probably not for long. If you get the chance to try psilocybin or magic mushrooms, do so with an experienced guide or clinician.

Since neuroplasticity allows us to engage with, learn from, and experience the world around us, there are hundreds, maybe thousands of ways for us to activate it. I’ve missed most of them, but I know you guys have some suggestions.

So let’s hear ’em. How do you train your brain? What’s your favorite way to increase neuroplasticity?

Oh, and don’t worry. Neuroplasticity is BPA-free.

Thanks for reading, everyone.

The post 16 Ways to Increase Neuroplasticity (and Why That’s Important) appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

October 25, 2016

Should You Eat Less Protein?

Over the past several years, I’ve noticed a subtle shift in the way the media discusses dietary protein, with many experts promoting lower intakes. The push for lower intakes hasn’t only come from the mainstream crowing about red meat and colon cancer. Many voices from the alternative health communities are urging a reduction in protein. Even the ancestral health community counts among its ranks protein skeptics.

Am I one? I’m not sure. In past posts, I’ve discussed how my own tastes have changed, going from eating high protein to more moderate amounts.

Today I’m addressing the standard arguments levied against high protein intakes. Hopefully, we can get to the bottom of the issue.

High protein diets stress the kidneys.

While it’s true that people with existing kidney damage or disease must limit protein intake, this isn’t the case in healthy people. Even type 2 diabetics with good kidney function can safely eat a long-term high-protein diet. If anything, higher protein intakes protect against kidney disease by making it easier to avoid obesity.

High protein diets exceed your capacity for ammonia detox.

Protein metabolism begets ammonia, a toxin. The liver usually converts ammonia into urea, which is safely expelled through the urine. The average human can handle about 230 grams of protein before ammonia-urea conversion tanks. After that, ammonia lingers. If your liver health is compromised, or your protein intake exceeds your ammonia detox capacity, ammonia toxicity can ensue.

Acute ammonia toxicity is neurotoxic, actually causing your astrocytes to swell. Rabbit starvation, which afflicted Arctic explorers living exclusively on lean protein (rabbits) and causes nausea, diarrhea, and eventually death, might derive from ammonia toxicity. A subtler, lower-grade ammonia toxicity likely exists in people with chronically-high intakes of protein. The dangers are mostly theoretical but based in physiology—ammonia is a toxin, and there is a limit to how much of it we can convert to urea.

High protein diets create toxins in the gut.

Sufficiently high intakes of protein can exceed the gut’s capacity to absorb it. The protein then passes on to the colon, where colonic bacteria ferment it and produce metabolic byproducts like ammonia, indoles, and phenols. As many of these compounds can have toxic effects, some have suggested that excess protein fermentation produces a toxic gut environment.

In one study, researchers gave subjects either a high protein diet, a low protein diet, or a normal protein diet. They analyzed the fecal water of each group for evidence of protein fermentation and ran a series of tests to determine the toxicity of each batch of fecal water. Surprisingly, while the high protein fecal water had elevated markers of fermentation, it was not toxic, and elevated protein fermentation metabolites actually correlated with lower cytotoxicity.

High protein diets give you cancer.

Vegans love citing the T. Colin Campbell research from the China Study, which appeared to show that high intakes of protein caused increased cancer deaths. While adequate intakes of protein (from casein) promoted the growth of existing tumors in those rodents, it also protected against the mutagens that cause the initial appearance of tumors. Protein was protective against cancer until they had it, at which point it accelerated the cancer’s progression. Rodents on the low protein diet were more susceptible to getting cancer after aflatoxin exposure. Once the rodents already had cancer, low protein was protective against further growth.

More accurate: adequate protein protects against the initiation of cancer (and probably other maladaptive ills), but patients with cancer should limit it. That makes sense. Context is everything.

Extra protein just converts to glucose.

Through the process of gluconeogenesis, we can convert protein into glucose. This has led some folks to believe that eating “extra protein” is like eating a piece of chocolate cake. So, does a high protein diet spike glucose levels? Is eating more protein just like cramming in extra sugar?

In one study, type 2 diabetics ate half a pound of steak (50 grams protein) and nothing else for breakfast. Compared to the control group who just had water, 50 grams of protein had almost no effect on glucose levels, adding just 2 grams to circulation. In another older study, eating up to 160 grams of protein in a single meal had no effect on blood glucose.

On the contrary, high-protein diets have been shown to improve glucose control in the population most at risk from high-carb intakes: type 2 diabetics.

High protein is unnecessary.

Protein is the most expensive macronutrient. In the wild, it takes the most energy to acquire. In the civilized world, it costs the most money to purchase. If we don’t need large amounts of protein, it makes sense to reduce our intake.

Many people lifting weights and cramming down protein shakes likely are eating more protein than they need. The more advanced you are as a lifter, the less protein you need. Beginners gain weight like crazy; experienced lifters do not.

Advanced lifters are closer to their genetic muscle ceiling. There’s less room to grow, so they grow more slowly, and muscle protein synthesis actually declines. Plus, their muscles have become more resistant to exercise-induced breakdown. It takes more to damage them, and there’s less to recover from. Overall, experienced lifters are more efficient with their protein and can maintain nitrogen balance at 1.05 g/kg. If they want to gain muscle, 1.8 grams per kg (which is much lower than most people assume) seems to be the absolute ceiling for natural lifters. After that, the benefits level off, and you’re just wasting protein.

Interestingly, endurance athletes require more protein than bodybuilders to remain in nitrogen balance.

High protein diets increase IGF-1 signaling.

IGF-1 is an important compound that helps us build and maintain bone and muscle mass. We need it to thrive, yet excessively high levels of IGF-1 may increase growth of unwanted tissues like tumors and hasten the aging process.

That said, there’s no indication that IGF-1 increases the formation of tumors. As in Campbell’s rats, it’s likely that IGF-1 makes the organism more robust, but once cancer is present, hastens its growth. And the proposed link between elevated IGF-1 and mortality in humans hasn’t been confirmed. It looks like both high and low levels are bad.

High protein diets reduce longevity.

A study from 2014 had a somewhat paradoxical finding: higher protein intakes had a negative effect on mortality in 50-year-olds, a neutral effect in 65-year-olds, and a beneficial effect in those over 80. Let’s assume for a second that the links are causal—that higher protein intakes are the proximate causes of the shifting mortality risks.

When older people eat more protein, even (or especially) if it comes from evil red meat, they get stronger, build more muscle, improve their ability to take care of themselves, and even think better. The studies didn’t track mortality, but loss of muscle, strength, independence, and cognitive function typically precede death in senior citizens. If higher protein intakes can improve those parameters, they should also improve survival in the population.

Another wrinkle is that dietary protein—especially of animal origin—is the best source of cysteine, a crucial backbone we use to produce the endogenous antioxidant glutathione. A group of researchers recently proposed that a reduction in glutathione synthesis “underlies” the increased mortality linked to low protein intakes in the elderly. Glutathione protects our liver, helps metabolize toxins, and regulates oxidative stress; glutathione deficiency in older populations has been linked to neurodegeneration, heart attacks, and “accelerated aging.”

What’s the verdict?

I’d advise against a low-protein diet unless you have an express reason to do so. You’ll likely grow lethargic, lose muscle mass, gain fat mass, and be less resilient in the face of stressors and illnesses. Maybe it’ll buy you an extra year or two, but at what cost? Low-protein diets have been shown to:

Slow the metabolism, increase insulin resistance, and cause body fat gain.

Impair the immune system and make infections more severe.

Reduce muscle function, cellular mass (yes, the actual mass of the cell itself), and immune response in elderly women.

Impair nitrogen balance in athletes.

Increase the risk of osteoporosis.

Increase the risk of sarcopenia (muscle wasting).

Meanwhile, high-protein diets confer a few potential risks, which I’ve laid out above.

There are clear benefits to higher protein intakes (lean mass retention, muscle growth, fat loss, increased satiety) and legitimate concerns (reduced longevity, excess IGF-1, too much growth of unwanted tissues). How do we square all the evidence? How do we balance the effects?

Short term is fine: Brief bursts of very high protein diets while lifting heavy things can probably help you shed excess weight and retain lean mass. Recent studies find evidence of improved body composition and no evidence of any deleterious effects up to 4.4 g/kg for several weeks at a time. I’m not sure I’d continue eating that much protein for the rest of your life though.

Go high and low: Eat high protein one day, lower protein the next. If you’re trying to gain muscle, you probably need more protein on workout days. If you’re just maintaining, you can get away with far less.

Fast: When someone constantly eats, never going more than 5-6 hours between meals, that person never gives his/her body time to recover and prune damaged cells. Intermittent fasting imposes periods of zero protein and zero food, giving your body a dose of autophagy and a respite from mTOR/IGF-1 activation, and likely making higher protein intakes on feeding days safer.

Overall, I’d say using 100 grams per day as a baseline and going as low as you can without suffering the negative symptoms is worth exploring. It’s likely enough for the majority of people reading this, and if you cycle your protein or fast, you give yourself a chance at some nice autophagy and healthy growth. Plus, you can always increase your intake if you notice negative symptoms.

Athletes aiming for muscle growth and endurance athletes trying to avoid muscle loss may go up to 1.8 g/kg. Dieting athletes should probably go at least that high to preserve lean mass.

Be sure to check out past posts on conditions that determine if you need more or less protein.

Don’t forget my previous protein intake recommendations for different populations.

Now I’d love to hear from you.

How much protein do you eat each day? How do lower—or higher—intakes affect you?

The post Should You Eat Less Protein? appeared first on Mark's Daily Apple.

Mark Sisson's Blog

- Mark Sisson's profile

- 199 followers