Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 9

September 21, 2016

Dr. Janet Smith: Positive response to pro-Humanae Vitae "Affirmation" has "been stunning"

Left: Dr. Janet Smith, who holds the Father Michael J. McGivney Chair of Life Ethics at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit; right: John Grabowski, Catholic University associate professor of moral theology and ethics, discusses a scholars' statement reaffirming Blessed Paul VI's 1968 "Humanae Vitae" encyclical on human sexuality at The Catholic University of America in Washington Sept. 20. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

Dr. Janet Smith: Positive response to pro-Humanae Vitae "Affirmation" has "been stunning" | Carl E. Olson | CWR's The Dispatch

"The dissenters still run some places," says the well-known speaker and author, "and some of the major professional organizations and journals but they are losing ground fast. They are no longer getting disciples."

Yesterday, the Catholic University of America hosted a press conference for the release of the document "Affirmation of the Catholic Church’s Teaching on the Gift of Sexuality", which was signed by over 500 Catholic scholars with doctoral degrees in theology, medicine, law and other fields. The document opens by stating: "We, the undersigned scholars, affirm that the Catholic Church’s teachings on the gift of sexuality, on marriage, and on contraception are true and defensible on many grounds, among them the truths of reason and revelation concerning the dignity of the human person." As the CNA/EWTN report explained:

Signatories of the document included Fr. Wojciech Giertych O.P., the theologian of the papal household; John H. Garvey, president of Catholic University of America; Tracey Rowland, Dean of the John Paul II Institute for Marriage & Family in Melbourne, Australia; Sister Prudence Allen, philosophy professor at St. John Vianney Seminary in Denver; Fr. Thomas Petri, O.P., academic dean of the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C.; and Helen M. Alvaré, law professor at George Mason University.

The scholars charged that a new U.K.-based statement opposing Church teaching “offers nothing new to discussions about the morality of contraception and, in fact, repeats the arguments that the Church has rejected and that numerous scholars have engaged and refuted since 1968.”

The statement in question, organized by the U.K.-based Wijngaards Institute, claims there are “no grounds” for Catholic teaching against contraception. It questioned the idea that openness to procreation is inherent to the significance of sexual intercourse, and said that “the choice to use contraceptives for either family planning or prophylactic purposes can be a responsible and ethical decision and even, at times, an ethical imperative.”

Yesterday's press conference at CUA included panelists John Grabowski, Catholic University associate professor of moral theology and ethics who served as an expert at the 2015 Synod of Bishops on the Family; Janet Smith, who holds the Father Michael J. McGivney Chair of Life Ethics at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit; and Mary Hasson, director of the Catholic Women’s Forum at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Late yesterday I e-mailed with Dr. Smith, who has also edited and authored several books, including Why Humanae Vitae Was Right: A Reader for Ignatius Press. Here is our written communication:

September 20, 2016

The Catholic Conscience, the Argentine Bishops, and "Amoris Laetitia"

(Photo: us.fotolia.com/andriychuk)

The Catholic Conscience, the Argentine Bishops, and "Amoris Laetitia" | E. Christian Brugger | Catholic World Report

Chapter 8 of Pope Francis' Apostolic Exhortation is characterized by a false dichotomy between the objective and subjective realms of morality, contrary to Vatican II and St. John Paul II.

A group of Argentine bishops (ABs) recently published pastoral guidelines for implementing Chapter 8 of Amoris Laetitia (AL). The ABs tell their clergy that under certain circumstances divorced Catholics in sexually active second unions may receive the Holy Eucharist, even without receiving an annulment.

The ABs sent their guidelines to Pope Francis to ask whether their pastoral approach was consistent with the meaning of AL. Pope Francis replied in a letter on papal stationary saying that their “document is very good and completely explains the meaning of chapter VIII of Amoris Laetitia”; he then stated, “There are no other interpretations.” The authenticity of the pope’s letter was verified on Sept. 12 by the Italian edition of L’Osservatore Romano and reprinted later by Vatican Radio. There no longer seems to be any doubt about where Pope Francis stands on the disputed “Kasper Proposal”.

Other authors have commented and reported on the papal reply, so I will not do so here. The purpose of this article rather is to critique the account of moral conscience implicit in the reasoning of the AB’s and AL as defended in a recent article in National Catholic Reporter by Michael Lawler and Todd Salzman entitled: “In Amoris Laetitia, Francis’ model of conscience empowers Catholic”. The Salzman-Lawler (SL) duet made fame in 2008 for its publication of the book, “The Sexual Person”, which set forth a fulsome defense of same-sex genital acts from Scripture, tradition, and natural reason, and which was censured by the Committee on Doctrine of the USCCB in 2010.

In the NCR article, the authors consider what they refer to as two “diametrically opposed” understandings of conscience, one which they say overly emphasizes the “objective realm” of moral truth, and the other which, in their opinion, rightfully emphasizes the “subjective realm” of freedom and individuality. Let’s call these the “objectivist” and “subjectivist” models.

SL say that St. John Paul II, Archbishop Charles Chaput (“Pastoral Guidelines for Implementing Amoris Laetitia”) and Germain Grisez represent the objectivist model; and Pope Francis (in Evangelii Gaudium 231-232 and Amoris Laetitia Ch. 8), the German Jesuit theologian Josef Fuchs, and German Redemptorist theologian Bernard Häring represent the subjectivist school.

In what follows I will show that SL have set up a false dichotomy between the objective and subjective realms of morality; then demonstrate how that false dichotomy characterizes the account of conscience found in the ABs and Ch. 8 of AL; and finally offer a fair explanation of the John Paul II-Chaput-Grisez (and Vatican II) account of conscience. I end with some remarks on the question of whether Catholics are obliged in conscience to accept the papal prescriptions taught in AL, Ch. 8.

Proportionalism: “no intrinsically wrongful actions”

Before summarizing SL’s account, it’s important to understand a presupposition of their theory. They follow the reasoning of Fuchs and Häring, who in the years after Vatican II became Europe’s foremost defenders of the moral theory known as “Proportionalism”. Although it comes in different flavors, common to all proportionalists is the insistence that intending evil as an end or means (what defenders refer to variously as “premoral evil”, “ontic evil”, “disvalue”, etc.) does not by that fact make an action morally wrong. If there are “morally relevant circumstances” justifying the commission of the evil—what they call “proportionate reasons” (not to be confused with proportionate reason as used in the classical Principle of Double Effect)—then it can rightly be chosen.

Why do I say this is important to understand?

September 15, 2016

Christian Life: The Outworking of Christ’s Life Within Us

[image error]

Christian Life: The Outworking of Christ’s Life Within Us | Fr. John Navone, SJ | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The Christian community of faith is born of the grace of God. Grace expresses what God does for us. Just as when we hear of the wisdom of God in the Bible, we think of how God’s action makes us wise, so when we hear of God’s justice we should think of that act by which he makes us just. God’s justice, like his goodness and compassion, is not God’s reaction to our behavior, but his initiative, quite irrespective of our behavior. God is free to do what he wills, and his freedom takes the form of acting so as to transform us. It is a mistake to think that “justification” means a change in God’s attitude without an effect in us. On the contrary, what changes is that we become the locus of God’s free activity. Unprovoked, unconditioned, and unconstrained by any other agent, God steps into the void and chaos of created existence and establishes himself there as God

The mystery of the cross tells of the place where the wretchedness of the created world, and the total failure of human resource, or human virtue, is most fully exhibited. Where else could we see God’s absolute freedom to be God, irrespective of any external conditions? And where but in our own emptiness and dereliction could we find what it is to trust, without reserve, in God’s freedom exercised for our sake? What gives us the ground to stand before God is God. The Christian community of faith believes that God has, in Christ, taken his stand in the human world, and answered for, taken responsibility for, every human being, quite apart from any achievement or aspiration on our part.

Christians believe the God whose historical biblical revelation inspired the biblical authors. They do not believe in the Bible independently of the God who inspired it. Such a belief would be bibliolatry: making an idol of the Book

Christian life is essentially the outworking of Christ’s life within us, expressing the Spirit of Christ poured into our hearts (Rom. 5:5). The incarnate Lord was not merciful, generous, and forgiving to win approval from heaven, since heaven was already his environment. His good works are the expression of who he is.

Our ability to discern the divine authority of Jesus Christ is, itself, the gift of God. The First Vatican Council taught that saving faith is impossible without the light and inspiration of the Holy Spirit that make assenting to, and believing the truth, a free and meritorious act of which the word suavitas (delight, pleasantness) may be used. St. Augustine spoke of the need of “inner eyes”; St. Thomas said that the principle cause of faith is the inner impulse of the Holy Spirit; Pierre Rousselot wrote of “the eyes of faith,” and Bernard Lonergan of faith as “the eyes of love.” The ocular metaphor for the communion of Christian faith and love with God originates in the Gospel of John: “Who sees me, sees the Father” (14:9).

The effectiveness of Christian witness is caused by the tri-dimensional, tri-personal unity of mutual love (of the Trinity) between the Father and the Son, among believers themselves, and ultimately, in that between all the believers and the Father and Son, into whose unity of mutual love they are absorbed. The unity of Christians in mutual love reveals the mutual love of the Father and Son as effectively present in the lives of believers whom their love unifies: “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (Jn 13:35). The love of God poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit authors the new life of Christian conversion within the community of faith.

All of this means that nothing can take the place of conversion—intellectual, moral, and religious. The converted are likely to discern correctly who may and should be trusted, and to trust them; the unconverted are likely to trust the untrustworthy, and not to trust the trustworthy. Unfortunately, it is also the case that people who occupy posts that only the trustworthy ought to occupy sometimes are not themselves trustworthy because they are not converted— intellectually, morally, religiously—and when that happens, a grave crisis can ensue. There is really no substitute for conversion, and that is the work of the Holy Spirit.

Affirming that we achieve authenticity in self-transcendence, Bernard Lonergan makes conversion a central theme in his Method in Theology. We are called to the realization of self-transcendence in terms of intellectual, moral, and religious conversion. Religious conversion, for Lonergan, is most vital, central, common, and foundational. Without it, a sustained and perduring moral conversion is a de facto impossibility. Similarly, without religious and moral conversion, a fully developed intellectual conversion that enables us to arrive at a critically grounded natural knowledge of the existence of God is for all practical purposes an impossible achievement.

Lonergan distinguishes between moral and religious conversion because he believes in the need to distinguish between nature and grace.

September 12, 2016

Is Dialogue with Islam Possible? Some Reflections on Benedict XVI's Address at the University of Regensburg

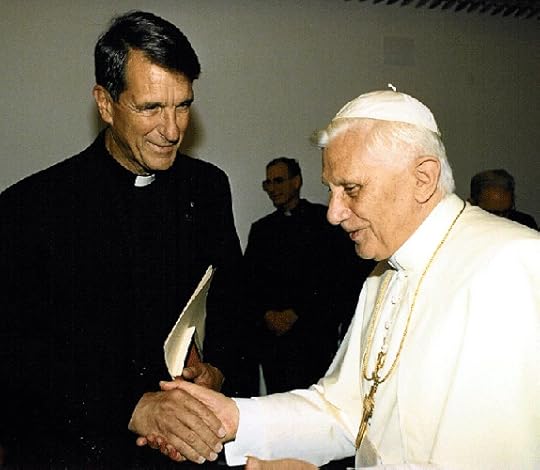

Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J., founder and editor of Ignatius Press, with Pope Benedict XVI.

Is Dialogue with Islam Possible? Some Reflections on Benedict XVI's Address at the University of Regensburg | Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.

Editor's note: This essay was originally published on Ignatius Insight on September 18, 2006. It is republished here on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Benedict XVI's Regensburg Address.

I.

Both before and since his elevation to the papacy, Benedict has taken a consistent approach to controversial issues: he locates the assumptions and fundamental principles underlying the controversy, analyzes their "inner" structure or dynamism, and lays out the consequences of the principles.

For example, in Deus Caritas Est, Benedict does not address directly the controversial issues of homosexual partners, promiscuity, or divorce. Instead he examines the "inner logic" of the love of eros, which is "love between man and woman, where body and soul are inseparably joined . . ." He shows that it has been understood historically to have a relationship with the divine ("love promises infinity, eternity") and to require "purification and growth in maturity ... through the path of renunciation". In love's "growth towards higher levels and inward purification ... it seeks to become definitive ... both in the sense of exclusivity (this particular person alone) and in the sense of being 'for ever'."

So starting from the "inner logic" of the fundamental reality of love, Benedict concludes to an exclusive and permanent relationship between a man and a woman. That is a fair description of the Catholic idea of marriage, and it excludes homosexual partners, promiscuity, and divorce.

Incidentally, in the very first paragraph of this encyclical, Benedict states: "In a world where the name of God is sometimes associated with vengeance or even a duty of hatred and violence, this message [that God is love] is both timely and significant." Clearly the religious justification of violence is an aberration that's on his mind.

II.

While in Deus Caritas Est Benedict defends the foundational truth that God is Love, in his Regensburg lecture he is defending the foundational truth that God is Logos, Reason. The central theme of the lecture is that the Christian conviction that God is Logos is not simply the result of a contingent historical process of inculturation that has been called the "hellenization of Christianity". Rather it is something that is "always and intrinsically true".

In the main body of the lecture, Benedict criticizes attempts in the West to "dehellenize" Christianity: the rejection of the rational component of faith (the sola fides of the 16th century reformers); the reduction of reason to the merely empirical or historical (modern exegesis and modern science); a multiculturalism which regards the union of faith and reason as merely one possible form of inculturation of the faith. All this is a Western self-critique.

But as the starting point of his lecture, Benedict takes a 14th century dialogue between the Byzantine Emperor and a learned Muslim to focus on the central question of the entire lecture: whether God is Logos. The Emperor's objection to Islam is Mohammed's "command to spread by the sword the faith he preached". The emperor asserts that this is not in accordance with right reason, and "not acting reasonably is contrary to God's nature". Benedict points to this as "the decisive statement in this argument against violent conversion".

It is at this point in the lecture that Benedict makes a statement which cannot be avoided or evaded if there is ever to be any dialogue between Christianity and Islam that is more than empty words and diplomatic gestures. For the Emperor, God's rationality is "self-evident". But for Muslim teaching, according to the editor of the book from which Benedict has been quoting, "God is absolutely transcendent. His will is not bound up with any of our categories, even that of rationality".

Benedict has struck bedrock. This is the challenge to Islam. This is the issue that lies beneath all the rest. If God is above reason in this way, then it is useless to employ rational arguments against (or for) forced conversion, terrorism, or Sharia law, which calls for the execution of Muslim converts to Christianity. If God wills it, it is beyond discussion.

III.

Let us now turn to the statement in Benedict's lecture which has aroused the most anger. Benedict quotes the Byzantine Emperor's challenge to the learned Muslim: "Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."

Benedict's main argument -- that God is Logos and that violence in spreading or defending religion is contrary to the divine nature -- could have been made without including that part of Emperor's remark (made "somewhat brusquely" according to Benedict) that challenges Islam much more globally. And in his Angelus message the following Sunday, Benedict said: "These (words) were in fact a quotation from a Medieval text which do not in any way express my personal thought." Nevertheless, it may be instructive to examine this "brusque" utterance of the Emperor and ask the question: Is it simply indefensible?

As a thought experiment, let's reverse the situation. Suppose a major spokesman for Islam publicly issued the challenge: "Show me just what Jesus brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman." What would be the Christian response? Not to burn a mosque or an effigy of the Muslim spokesman, or to shoot a Muslim nurse in the back in Somalia. It would rather be to reply with some examples of just what makes the New Covenant new: the revelation that God is a Father who has a co-equal Son and Holy Spirit; that Jesus is God's Son made flesh; the Sermon on the Mount; the Resurrection of the body; the list would be long. As Irenaeus put it: he brought all newness, bringing himself. Such a statement would not make dialogue impossible; it would be an occasion for dialogue.

There is obviously much room for qualification in the Emperor's blunt statement, even for a Christian who holds that Mohammed was not a prophet, and that whatever is good in Islam is traceable either to man's natural religious knowledge or to conscious or unconscious borrowings from Jewish and Christian revelation.

Yet there is a crucial underlying principle that needs to be enunciated. Christianity and Islam make incompatible truth claims. Despite the difficulty in determining who can speak authoritatively for Christianity or for Islam, there are elements of belief common to all Christians which are incompatible with elements of belief common to all Muslims. The two most obvious and most fundamental are the Trinity and the Incarnation.

I would expect an intelligent and informed Muslim to consider me a blasphemer (because I introduce multiplicity into the one God) and an idolator (because I worship as God a man named Jesus). Should I be offended if he says so publicly? Should I not rather be offended if he conceals his position for the alleged purpose of fostering dialogue?

The question of respect is entirely distinct. Benedict is clearly aware of this distinction as evidenced in the official Vatican statement subsequent to Benedict's lecture, where the Secretary of State refers to his "respect and esteem for those who profess Islam". That is, one can and should respect Muslims (those who profess Islam) as persons with inherent dignity; but where there are incompatible truth claims, they cannot be simultaneously true. One cannot hold one as true without holding the other as false. Any religious dialogue should begin by examining the evidence for the incompatible claims.

It's worth noting, however, that while consistent Christians and Muslims in fact hold the position of the other to be erroneous in important ways, the Christian is not obliged by his faith to subject the Muslim to dhimmitude nor to deny him his religious freedom. There is a serious asymmetry here, which Benedict has criticized before. The Saudis can build a multi-million dollar mosque in Rome; but Christians can be arrested in Saudi Arabia for possessing a Bible.

Certainly, it may sound provocative to make the claim the Emperor did. But why (since Christians believe that God's full and definitive revelation has come with Christ, who brings all prophecy to an end) isn't it just as provocative for a Muslim to proclaim that Mohammed is a new prophet, bringing new revelation that corrects and supplements that of Christ?

Is it really offensive to say that Christians and Muslims disagree profoundly about this? Is not this the necessary starting point that must be recognized before any religious dialogue can even begin?

And if the response from Islam is violence, then must we not ask precisely the question raised by Benedict: Is this violence an aberration that is inconsistent with genuine Islam (as similar violence by Christians would be an aberration inconsistent with genuine Christianity)? Or is it justifiable on the basis of Islam's image of God as absolutely transcending all human categories, even that of rationality? And if the response to this question is violence, then the question has been answered existentially, and rational dialogue has been repudiated.

IV.

Finally, has no one seen the irony in the episode related by Benedict? Byzantium was increasingly threatened in the 14th century by an aggressive Islamic force, the growing Ottoman Empire. The Byzantine Emperor seems to have committed the dialogue to writing while his imperial capital, Constantinople, was under siege by the Ottoman Turks. It would fall definitively in 1453. Muslims were military enemies, engaged in a war of aggression against Byzantium. Yet even in these circumstances the Christian Emperor and the learned Persian Muslim could be utterly candid with one another and discuss civilly their fundamental religious differences. As Benedict described the dialogue, the subject was "Christianity and Islam, and the truth of both".

The West is once again under siege. Doubly so because in addition to terrorist attacks there is a new form of conquest: immigration coupled with high fertility. Let us hope that, following the Holy Father's courageous example in these troubled times, there can be a dialogue whose subject is the truth claims of Christianity and Islam.

September 11, 2016

The Parable of the Perfect Father

Detail from "The Return of the Prodigal Son" by Rembrandt (1669).

Carl E. Olson | On the Readings for Sunday, September 11, 2016

Readings:

• Ex 32:7-11, 13-14

• Ps 51:3-4, 12-13, 17, 19

• 1 Tim 1:12-17

• Lk 15:1-32

The parable of the prodigal son is well known, arguably the most famous of Jesus’ parables. Yet, as Scripture scholar Joachim Jeremias states in The Parables of Jesus (New York, 1963), it “might more correctly be called the parable of the Father’s Love…”, for it is a powerful and unforgettable depiction of God’s love and mercy.

While the two sons are decidedly human—sinful, self-centered, materialistic—the father exhibits a serene, pervasive holiness that reveals the heart of the heavenly Father. In Dives in misericordia, his encyclical on the mercy of God, Pope John Paul II noted that although the word “mercy” doesn’t appear in the famous parable, “it nevertheless expresses the essence of the divine mercy in a particularly clear way.” Read carefully, the parable offers a wealth of insight into our relationship with our heavenly Father; it offers a glimpse of the Father’s face. But it also is a mirror that confronts us with our own distorted priorities and self-centered attitudes.

For example, the younger son’s request for his share of the estate was not just an impulsive, youthful demand for autonomy, but a harsh renunciation of his father. In essence, his demand was a way of publicly declaring, “I wish you were dead!” The son, wrote St. Peter Chrysologus, “is weary of his father’s own life. Since he cannot shorten his father’s life, he works to get possession of his property.” In rejecting his father and the life-giving communion he once had with him, he lost the privilege of being a son and embarked upon a calamitous course.

As a father myself, I think it is safe to say that most ordinary fathers would have objected to the son’s request, even refused to consider it. Yet our heavenly Father does not object; he respects our freedom—his great gift to us—even when we use it to rebel against him. So the father divided up the property; in doing so, grace was destroyed and communion was severed. The familial bond was broken, and the son took his money into the “far country,” a reference to a place of utter emptiness and spiritual desolation.

“What is farther away,” asked St. Ambrose, “then to depart from oneself, and not from a place? … Surely whoever separates himself from Christ is an exile from his country, a citizen of the world” The physical distance was not as painful as the loss of familial love and embrace; the son’s inner life vanished as quickly as did his inheritance. He is soon faced with eating unclean swill while tending unclean animals, the swine.

How did the son come to his senses? An answer can be found in today’s epistle, in which St. Paul confesses his sins of blasphemy, persecution, and arrogance, and explains he has “been mercifully treated because I acted out of ignorance in my unbelief.” By God’s grace he—a prodigal son—recognized his sinfulness. Confronted by Christ on the dusty road to Damascus, he experienced divine grace and mercy.

The prodigal son knew his father had every right to disown him, to consider him dead and gone. But he was willing to admit his sin and become a nameless hired hand. Yet, even as he tried to articulate a cry for mercy, he was wrapped in mercy—held, kissed, clothed, and restored to life. Having walked away in petulant selfishness, the son had embraced death; having been embraced by his patient and compassionate father, he was restored to life.

John Paul II explained that God is not just Creator, but “He is also Father: He is linked to man, whom He called to existence in the visible world, by a bond still more intimate than that of creation. It is love which not only creates the good but also grants participation in the very life of God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For he who loves desires to give himself.” The merciful Father waits for the dead, eager to clothe them with new life.

(This is "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the September 12, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

September 8, 2016

Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J., discusses core message of DOCAT: "Do good and avoid evil."

CWR Staff | Catholic World Report

Fr. Fessio, the founder and editor of Ignatius Press, was recently interviewed by Sean Salai, S.J. for America magazine about DOCAT, the follow-up to the popular youth catechism YOUCAT. Focused on the social doctrine of the Church, DOCAT was officially released by Pope Francis at World Youth Day in July. Here are some of Fr. Fessio's remarks on the genesis and contents of DOCAT:

What inspired Pope Francis to publish a youth catechism on Catholic social teaching and how did you get involved?

Actually, if Pope Francis was inspired, it was post factum. Docat had already been planned, and the writing had begun, before his election to the papacy. However, it is certainly a happy providence that the Docat aligned so well with his interests and priorities.

My involvement in the Youcat and now the Docat has an odd pre-history. Cardinal Christoph Schönborn and I have been friends since we lived together in the Schottenkolleg (at the time the diocesan seminary) in Regensburg in 1973-74 as students of then-Professor Ratzinger. In the 1990s he asked for my help in the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. After the publication of the Catechism he was making a presentation in his Archdiocese of Vienna and during the Q&A period a woman stood up and said, in so many words, “This is wonderful. But it’s for adults. What about the children? They need a catechism too.”

Cardinal Schönborn responded by agreeing with her, but saying it needed to be a catechism not only for but also with the participation of young people. The woman organized two summer youth programs to work on adapting the Catechism for young people. She was joined by Bernhard Meuser, a German editor and youth catechist. From this the Youcat was born.

How did Ignatius Press become English-language publisher of the Youcat and now the Docat?

When Bernhard contacted me to see if Ignatius Press would be interested in being the publisher of the worldwide English edition, I assumed it was because of Cardinal Schönborn. That was not the case.

I had been invited to give a talk in Torun, Poland, and while I was there I was interviewed by a journalist working for a German Catholic magazine called Vatikan. He asked me about the origins of Ignatius Press. I explained that during my theology studies in Europe I had not only made the acquaintance of theologians like de Lubac, von Balthasar, Bouyer and Ratzinger but also for the first time had begun drinking wine (in France) and beer (in Bavaria).

Upon my return to the United States, I had my first taste of American beer. I spat it out and said, “If this is going to be called beer, I need another name for what I drank in Bavaria.” (This was in the days before the microbrewery revolution.) Later, as I was giving a retreat and quoting de Lubac, Balthasar, et al., a sister asked me if there were any great American theologians. I told her the beer story and said that while there were some very good theologians in the United States (I mentioned Avery Dulles, of course), still, if we were going to call them theologians, we needed another name for the giants I had studied in Europe.

I concluded the interview by saying that Ignatius Press was founded in 1979 so that the writings of these theologians could be accessible to an English-speaking readership.

And:

How is the Docat a successor to the Youcat in spirit and content?

The spirit, the collaboration of young people, and the appealing language and graphics are just like the Youcat. But the Docat focuses on the church’s social teaching and expands the Youcat’s treatment of it.

Where did you get the acronym “Docat” and what does it stand for?

It’s from the Germans, whose popular culture includes a lot of borrowings from the United States. Youcat was a contraction for “Youth Catechism.” (Sounds much more appealing to young Germans—and everyone else—than Jugendkatechismus.) Docat is a back formation from Youcat: “Do” (as in moral and social obligations) and “Catechism.” ...

What is the message of this catechism?

Do good and avoid evil. With a little more detail and practical help, of course.

"The Blessed Virgin in the History of Christianity" by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.

The Blessed Virgin in the History of Christianity | John A. Hardon, S.J.

Christianity would be meaningless without the Blessed Virgin. Her quiet presence opened Christian history at the Incarnation and will continue to pervade the Church's history until the end of time.

Our purpose in this meditation is to glance over the past two thousand years to answer one question: What are the highlights of our Marian faith as found in the Bible and the teaching of the Catholic Church?

New Testament

The first three evangelists were mainly concerned with tracing Christ's ancestry as Son of Man and, therefore, as Son of Mary. St. Matthew, writing for the Jews, stressed Christ's descent from Abraham. St. Luke, disciple of St. Paul, traced Christ's origin to Adam, the father of the human race. Yet both writers were at pains to point out that Mary's Son fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah about the Messiah. He was to be born of a virgin to become Emmanuel, which means "God with us." Luke gave a long account of the angel's visit to Mary to announce that the Child would be holy and would be called the "Son of God" (Luke 1:36).

St. John followed the same pattern. He introduced Mary as the Mother of Jesus when He began His public ministry. In answer to her wishes, Christ performed the miracle of changing water into wine at the wedding feast in Cana in Galilee. What happened then has continued ever since. Most of the miraculous shrines of Christianity have been dedicated to Our Lady.

It is also St. John who tells us that Mary stood under the Cross of Calvary as her Son was dying for our salvation. Speaking of John, Jesus told His Mother, "This is your son." To John, He said of Mary, "This is your Mother." The apostle John represented all of us. On Good Friday, therefore, Christ made His Mother the supernatural Mother of the human race and made us her spiritual children.

Mother of God

In the early fifth century, a controversy arose in Asia Minor, where the Bishop of Constantinople claimed that Mary was only the Mother of Christ (Greek=Christotokos). He was condemned by the Council of Ephesus in 431, which declared that "the holy Virgin is the Mother of God (Greek=Theotokos).

St. Cyril, Bishop of Alexandria in Egypt, was mainly responsible for this solemn definition of Mary's divine maternity. It was St. Cyril who thus composed the most famous Marian hymn of antiquity. It is a praise of Our Lady as Mediatrix with God:

Through you, the Trinity is glorified.

Through you, the Cross is venerated throughout the world.

Through you, angels and archangels rejoice.

Through you, the demons are driven away.

Through you, the fallen creature is raised to heaven.

Through you, the churches are founded in the whole world.

Through you, people are led to conversion.

Every other title of Mary and all the Marian devotion of the faithful are finally based on the Blessed Virgin's primary claim to our extraordinary love. She is the Mother of God. She gave her Son all that every human mother gives the child she conceives and gives birth to. She gave Him His human body. Without her, there would have been no Incarnation, no Redemption, no Eucharist; in a word, no Christianity.

Mary's Virginity

Logically related to her divine maternity is Our Lady's perpetual virginity. From the earliest days the Church has taught that Mary was a virgin before giving birth to Jesus, in giving His birth, and after His birth in Bethlehem.

All of this is already stated or implied in the Gospels. In St. Matthew's genealogy of Jesus, all the previous ancestors are called "father." But then we are told there came "Joseph, the husband of Mary of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Christ" (Matthew 1:16). St. Luke twice identifies Mary as "virgin," who "knows not man."

Already in the early Church, those who questioned Christ's divinity were the same ones who denied His Mother's virginity. As explained by St. Augustine, "When God vouchsafed to become Man, it was fitting that He should be born in this way. He who was made of her, had made her what she was: a virgin who conceives, a virgin who gives birth; a virgin with child, a virgin labored of child-a virgin ever virgin."

Given the fact of the Incarnation, its manner follows as a matter of course. Why should not the Almighty who created His Mother have also preserved the body of which He would be born? But this appropriateness of Mary's virginity makes sense only if you believe that Mary's Son is the living God.

Immaculate Conception

Mary's freedom from sin, present at her conception, is already taught by St. Ephraem in the fourth century. In one of his hymns, he addresses Our Lord, "Certainly you alone and your Mother are from every aspect completely beautiful. There is no blemish in you my Lord, and no stain in your Mother."

By the seventh century, the feast of Mary's Immaculate Conception was celebrated in the East. In the eight century, the feast was commemorated in Ireland, and from there spread to other countries in Europe.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, some leading theologians, even saints, raised objections to the Immaculate Conception. Their main difficulty was how Mary could be exempt from all sin before the coming of Christ. Here the Franciscan Blessed John Duns Scotus (1266-1308) stood firm and paved the way for the definition of the Immaculate Conception by Pope Blessed Pius IX in 1854.

In the words of Pope Blessed Pius IX, "We declare, pronounce, and define that the doctrine which holds that the most Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instant of her conception . . . was preserved from all stain of original sin, is a doctrine revealed by God and therefore to be believed firmly and constantly by all the faithful."

Four years after the definition, Our Lady appeared to St. Bernadette in Lourdes, identifying herself as the Immaculate Conception. The numerous miracles at Lourdes are a divine confirmation of the doctrine defined by Pius IX. They are also a confirmation of the papal primacy defined by the First Vatican Council under the same Bishop of Rome.

Assumption into Heaven

Not unlike his predecessor, Pope Pius XII defined Mary's bodily Assumption into heaven. On November 1, 1950, the pope responded to the all but unanimous request of the Catholic hierarchy by making a formal definition:

By the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by our own authority, we pronounce, declare and define as divinely revealed dogma: the Immaculate Mother of God, Mary ever Virgin, after her life on earth, was assumed body and soul to the glory of heaven.

The day after the definition, Pius XII told the assembled hundreds of bishops his hope for the future: May this new honor given to Mary introduce "a spirit of penance to replace the prevalent love of pleasure and a renewal of family life stabilized where divorce was common and made fruitful where birth control was practiced." If there is one feature that characterizes the modern world, observed the Pope, it is the worship of the body. Mary's bodily Assumption into heaven reminds us of our own bodily resurrection on the last day, provided we use our bodies on earth according to the will of God.

Mother of the Church

Never in the history of Christianity has any general council spoken at such length and with such depth about Mary as the Second Vatican Council.

This is not surprising in view of the extraordinary devotion to the Blessed Virgin in our day. What the Council did was put this devotion into focus and spell out its doctrinal foundation.

First a quiet admonition. The council "charges that practices and exercises of devotion to her be treasured as recommended by the teaching authority of the Church in the course of centuries." True Marian piety consists neither in fruitless and passing emotion, nor in a certain empty credulity.

Rather authentic devotion to Mary "proceeds from true faith by which we are led to know the excellence of the Mother of God, and are moved to filial love toward our Mother and to the invitation of her virtues" (Constitution on the Church, 67-8).

What are we being told? We are told that true devotion to Our Lady is shown in a deep love of her as our Mother, put into practice by the imitation of her virtues-especially her faith, her chastity and charity.

These are the three virtues that the modern world most desperately needs.

• Like Mary, we need to believe that everything which God has revealed to us will be fulfilled.

• Like Mary, we need to use our bodily powers to serve their divine purpose no matter what the sacrifice of our own pleasure.

• Like Mary, we are to be always sensitive to the needs of others. Like her, we are to respond to these needs without being asked and, like her, even ask Jesus to work a miracle to benefit those whom we love.

No wonder the Catechism of the Catholic Church makes this astounding profession of faith: "We believe that the most holy Mother of God, the new Eve, Mother of the Church, continues in heaven her maternal role toward the members of Christ." It all depends on our faith in her maternal care and our trust in her influence over the almighty hand of her Son.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2001 issue of The Catholic Faith magazine.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Excerpts:

• "Hail, Full of Grace": Mary, the Mother of Believers | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Mary in Feminist Theology: Mother of God or Domesticated Goddess? | Fr. Manfred Hauke

• Excerpts from The Rosary: Chain of Hope | Fr. Benedict Groeschel, C.F.R.

• The Past Her Prelude: Marian Imagery in the Old Testament | Sandra Miesel

• Immaculate Mary, Matchless in Grace | John Saward

• The Medieval Mary | The Introduction to Mary in the Middle Ages | by Luigi Gambero

• Misgivings About Mary | Dr. James Hitchcock

• Born of the Virgin Mary | Paul Claudel

• Assumed Into Mother's Arms | Carl E. Olson

• The Disciple Contemplates the Mother | Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis

Father John Hardon, S.J. (b. June 18th, 1914 - d. December 30, 2000) was the Executive Editor of The Catholic Faith magazine. He was ordained on his 33rd birthday, June 18th, 1947 at West Baden Springs, Indiana. Father Hardon was a member of the Society of Jesus for 63 years and an ordained priest for 52 years. Father Hardon held a Masters degree in Philosophy from Loyola University and a Doctorate in Theology from Gregorian University in Rome. He taught at the Jesuit School of Theology at Loyola University in Chicago and the Institute for Advanced Studies in Catholic Doctrine at St. John's University in New York. A prolific writer, he authored over forty books, including The Catholic Catechism, Religions of the World, Protestant Churches of America, Christianity in the Twentieth Century, Theology of Prayer, The Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan, History And Theology Of Grace, With Us Today: On the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, and The Treasury Of Catholic Wisdom, which he edited.

Father John Hardon, S.J. (b. June 18th, 1914 - d. December 30, 2000) was the Executive Editor of The Catholic Faith magazine. He was ordained on his 33rd birthday, June 18th, 1947 at West Baden Springs, Indiana. Father Hardon was a member of the Society of Jesus for 63 years and an ordained priest for 52 years. Father Hardon held a Masters degree in Philosophy from Loyola University and a Doctorate in Theology from Gregorian University in Rome. He taught at the Jesuit School of Theology at Loyola University in Chicago and the Institute for Advanced Studies in Catholic Doctrine at St. John's University in New York. A prolific writer, he authored over forty books, including The Catholic Catechism, Religions of the World, Protestant Churches of America, Christianity in the Twentieth Century, Theology of Prayer, The Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan, History And Theology Of Grace, With Us Today: On the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, and The Treasury Of Catholic Wisdom, which he edited.

September 5, 2016

New: "How I Stayed Catholic at Harvard: Forty Tips for Faithful College Students" by Aurora Griffin

Now available from Ignatius Press:

How I Stayed Catholic at Harvard: Forty Tips for Faithful College Students

by Aurora Griffin

• Also available as an Electronic Book Download

A Harvard graduate, Rhodes Scholar, and devout Catholic tells you everything you need to know about keeping your faith at a modern university. Drawing on her recent experience, Aurora Griffin shares forty practical tips relating to academics, community, prayer, and service that helped her stay Catholic in college.

She reminds us that keeping the faith is a conscious decision, reinforced by commitment to daily practices. Aurora’s story illustrates that when you decide your faith matters to you, no one can take it away, even in the most secular environments and under strong peer pressure. Throughout the book, she shows how being Catholic in college did not prevent her from having a full “college experience,” but actually enabled her to make the most of her time at Harvard.

Aurora encourages students who are about to begin this formative journey, or those now in college, that the most valuable parts of college life -- lasting friendships, intellectual growth, and cherished memories -- are experienced in a more meaningful way when lived in and through the Catholic faith.

Aurora Catherine Griffin attended Harvard University, where she graduated Magna Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa with a degree in Classics in 2014. There she served as President of the Catholic Student Association. She was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford University, where she received a graduate degree in Theology.

"The best way to keep your faith, at any college, is to read this book."

— Peter Kreeft, Ph.D, Professor of Philosophy, Boston College

"Those who go to college without a plan are likely to lose the greatest legacy their parents have given them. Aurora Griffin has given us that plan. And if it can work at Harvard, it can work anywhere. This book is an answer to many, many prayers."

— Scott Hahn, Ph.D, Author, Rome Sweet Home

"Pure gold. In her warm, but practical style, Miss Griffin makes every one of her forty points crystal-clear and down to earth. She shows how a living faith is not a tablet of beliefs and commands, but a more joyful life to be lived. She gets it."

— Michael Novak, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research

"Miss Griffin engages her readers, not as an advisor who knows all, but as a peer who has just experienced college as a faithful Catholic. She insists on the importance of community and friendship in walking with Christ, as well as personal engagement with Scripture and the Sacraments. This book is a shining example of what the next generation of leaders can do to further the work of the new evangelization. Please read this book and join her."

— Curtis Martin, President, FOCUS

September 4, 2016

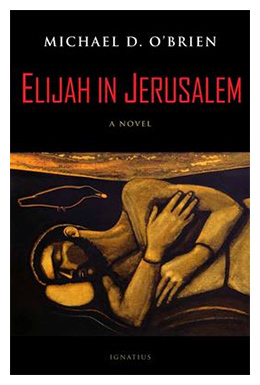

Michael O’Brien to receive Aquinas Award for Fiction

by John Herreid | IPNovels.com

The 2016 Aquinas Award for Fiction will be given to Michael D. O’Brien for his novel Elijah in Jerusalem at Aquinas College’s Second Annual Tolkien & Lewis Celebration in Nashville, Tennessee. Joseph Pearce, the acclaimed literary biographer and director of the Center for Faith and Culture, will present the award to Mr. O’Brien, who will be at the event to accept.

The Aquinas Award for Fiction is judged by a panel of five judges appointed by Mr. Pearce. Last year’s award went to Ignatius Press author Lucy Beckett for her historical novel The Leaves are Falling.

“I was looking for ways in which the Center could serve as a catalyst for a new Catholic literary revival. It seemed that launching the Aquinas Award for Fiction would serve in this way as a means of encouraging Catholic novelists and their publishers,” explained Joseph Pearce in an interview with Ignatius Press Novels last year.

Apart from the presentation of the Aquinas Award for Fiction, the Second Annual Tolkien & Lewis Celebration will include talks and presentations from authors such as Joseph Pearce, Fr. Dwight Longenecker, Michael Ward, Devin Brown, and Hal Poe, and a performance by Kevin O’Brien and the Theatre of the Word.

The event takes place at Aquinas College in Nashville on Saturday, September 17, 2016.

September 2, 2016

Being the “poorest of the poor” with Mother Teresa

An undated file picture shows Mother Teresa holding a child during a visit to Warsaw, Poland. Mother Teresa will be canonized by Pope Francis Sept. 4 at the Vatican. (CNS photo/Tomasz Gzell, EPA)

Being the “poorest of the poor” with Mother Teresa | Donna-Marie Cooper O’Boyle | Catholic World Report

How Mother Teresa taught this wife and mother to see and to serve Jesus in everyone she meets.

Never in my wildest dreams did I ever think I would be staying at Mother Teresa’s homeless shelters. And not just once, but twice. Truth be told, I have endured times of poverty, but my days spent in the shelters were not during those times, and they were in two different parts of the world.

The first time was in Harlem, New York about 30 years ago, when it was very dangerous to be on the streets of that barbed-wire jungle. The second time was just a few years ago in Rome, Italy.

Allow me to back up a bit in order to tell the story about meeting my spiritual mother, whom others knew as the Saint of the Gutters, or simply as Mother Teresa. Almost 30 years ago, I first laid eyes on the little saint of the poor, dressed in a simple white cotton sari trimmed in Blessed Mother blue. I caught my first glimpse of her out of the corner of my eye, when she walked right past me quietly in her bare feet just before Mass was about to begin at the Missionaries of Charity convent in Washington, DC.

I was visiting the nation’s capital because my spiritual director, Father John A. Hardon, SJ, had asked me to bring my family to see him for a face-to-face meeting. After our time with him, at Father’s encouragement, we set out to visit the sick and dying in the “Gift of Peace” home at the convent. We had a very meaningful visit, observing the great love and tenderness shown to the poor and suffering living in the home, at which there was a clear and beautiful aura of holiness. The MC sisters invited us to return the following day for a private Mass in their chapel. I was honored to be invited, but imagine my excitement when one sister informed me that Mother Teresa would be at one of their two Masses the next day; she didn’t know which one. My heart secretly soared hearing that Mother Teresa was there at the convent. Still, as much as I had always admired her for her selfless work with the poor and had considered her to be a living saint, I didn’t want to take up her time if we happened to see her the following day.

Early the next morning, we arrived at the convent’s chapel and I spotted several pairs of sandals lined up outside the door, which prompted us to take off our shoes before entering. Once inside, one of the first things I noticed was actually a lack of things. The chapel was very stark, yet so very meaningful. The few items there—an altar, a tabernacle, a crucifix, a statue of the Blessed Mother, and the words, “I Thirst” painted on the wall beside the tabernacle—drew my heart to what was most important. Those two words—“I thirst”—would echo in my heart for years after, and still do. I settled my children and we all knelt down to say our prayers before Mass.

Meeting the Saint of the Gutters

We had picked the right Mass, for Mother Teresa unexpectedly walked in. She seemed to float right past me. I needed to quickly direct my mind back to the Mass that was about to begin. Never mind the fact that a living saint was in our midst! I was kneeling down on the chapel’s bare floor with my husband and children, trying my best to prepare my heart for Mass, while still keeping an eye on my children: Justin, Chaldea, and Jessica. Mother Teresa’s presence certainly seemed to send a holy jolt up and down my spine!

Another surprise unfolded right after the Mass.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers