Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 7

November 17, 2016

New: "Mary of Nazareth: History, Archaeology, Legends" by Michael Hesemann

Now available from Ignatius Press:

Mary of Nazareth: History, Archaeology, Legends

by Michael Hesemann

This is the first archaeological and historical biography of the most fascinating and revered woman in history, the Mother of Christ. Millions of faithful around the world invoke her as their Queen, Protectress and Advocate. But who was this extraordinary woman chosen by God to give birth to the Savior? Michael Hesemann searched for her traces in Italy, Israel, Turkey and Egypt. Based on biblical traditions, legends and archaeological discoveries, he reconstructs the life of Mary of Nazareth, the Mother of the Messiah.

From the most ancient icon of Christianity to the Holy House in Loreto, from the Grotto of Nazareth to the refuge of the Holy Family in Egypt, from Mary's residence in Ephesus, Turkey, to Mount Zion and her empty tomb in Jerusalem, this is a journey of discovery, full of surprising insights that deepen our faith in the great mystery of the Mother of God.

Michael Hesemann studied History and Cultural Anthropology at Goettingen University, Germany. His 38 books have been published in 14 languages. He lives in Duesseldorf and Rome where he teaches Church history. He participated in archaeological excavations in the Holy Land, and helped to date discoveries in Nazareth as well as several Christian relics. He advised and participated in TV programs for the Discovery Channel, the History Channel,and EWTN. Together with Msgr. Georg Ratzinger, he wrote the international bestseller on Pope Benedict XVI, My Brother, the Pope.

"Michael Hesemann brings the work of careful scholarship to bear in Mary of Nazareth, and gives a book rich in research and redolent of a healthy respect for Our Lady and her only Son, Jesus Christ Our Lord."

— Mark P. Shea, Author, Mary, Mother of the Son

"Through historical, archaeological and textual research, Hesemann takes us on a lively adventure that sheds fascinating new light on the mother of Jesus. His personal devotion to the Virgin shines through his extensive scholarship to create a delightful and enchanting portrait of the Mother of God."

— Paul Thigpen, Ph.D., Author, A Year with Mary: Daily Meditations on the Mother of God

"We pray to her and hold her up as an example of faith and virtue, but what do we really know about Mary and her life? Michael Hesemann has studied the texts, searched the world for clues and compiled the details of Mary's life in a readable and exciting story. He introduces us to the real Mary and all the details of her unique and exemplary life."

— Steven Ray, Author, Crossing the Tiber

"I'm thrilled to have discovered this work, which provides a context for and answers to many of my long-held queries about Mary. Meticulously researched yet accessibly written. I strongly recommend it!"

— Lisa Hendey, Founder, CatholicMom.Com

November 14, 2016

Digging into Pope Francis' remarks about the "old Latin Mass", "rigidity" and "insecurity"

Pope Francis celebrates Mass in St. Peter's Basilica Nov. 13. (CNS photo/Remo Casilli, Reuters)

Recent remarks by the Holy Father about young people and the Extraordinary Form sound more like the words of a psychologist than a pastor.

by Carl E. Olson on The Dispatch at Catholic World Report

A November 10th article by CNS reporter Cindy Wooden about a new collection, in Italian, of homilies and speeches given by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been raising eyebrows. And even some ire. The problem, to be clear, isn't in Wooden's reporting, but in some excerpts from the book, specifically a new interview given by Pope Francis to his close confidant Fr. Antonio Spadaro SJ, who is Editor-in-Chief of Civiltà Cattolica. The except in question is at the very end of the article:

Listening to people’s stories, including in the confessional, is essential for preaching the Gospel, he said. “The further you are from the people and their problems, the further you hide behind a theology framed as ‘You must and you must not,’ which doesn’t communicate anything, which is empty, abstract, lost in nothingness.”

Asked about the liturgy, Pope Francis insisted the Mass reformed after the Second Vatican Council is here to stay and “to speak of a ‘reform of the reform’ is an error.

In authorizing regular use of the older Mass, now referred to as the “extraordinary form,” now-retired Pope Benedict XVI was “magnanimous” toward those attached to the old liturgy, he said. “But it is an exception."

Pope Francis told Father Spadaro he wonders why some young people, who were not raised with the old Latin Mass, nevertheless prefer it.

“And I ask myself: Why so much rigidity? Dig, dig, this rigidity always hides something, insecurity or even something else. Rigidity is defensive. True love is not rigid.”

Those who follow Francis' various addresses and interviews closely will recognize the usual rhetoric: the implication that theology (or doctrine) is somehow opposed to pastoral ministry, the psycho-analysis of those the Pope disagrees with, the pretense to contemplation without evidence of much insight, and the digs—in more than one sense, in this case—at supposed rigidity, insecurity, and defensiveness.

Much could be said about the the excerpt above, but I'll first note, in fairness, that the full context of the remarks isn't known and the remarks are apparently not official translations. That said, it's hard to not be disappointed, or even troubled, by the Holy Father's comments and approach. And there are a couple of deep ironies involved. One of them is that Francis insists strongly in the need to close to the people and their problems, but then, in remarking on why some young people (and plenty of older people as well) would be attracted to the "old Latin Mass", gives every appearance of not having really been close to any of the young people in question. I don't attend the Extraordinary Form (EF), but I know several people who do, including many younger folks, and I have talked to them at length about the EF and the Ordinary Form. To respond to these young people and their motives with shallow neo-Freudian dismissals comes off as both unfair and uncharitable.

A second irony is that this excerpt, as it stands, does not give the impression of a sensitive and caring pastor, but of an annoyed and arrogant man who cannot fathom why people many decades younger than himself would think or act differently than he thinks they should.

Part of the problem, to return to a point stressed in detail in my October 2016 editorial, is that pitting theology and doctrine over and against pastoral ministry is going to create a number of problems and will lead, again and again, to a skewed reading of people and events.

November 10, 2016

Catholicism embodied: “The Pivotal Players”

Catholicism embodied: “The Pivotal Players” | George Weigel | Catholic World Report

In Bishop Barron's new DVD series, six of the most striking personalities in Catholic history take center stage, the adventure of their lives serving to deepen our understanding of the “faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3).

Looking for some uplift after this tawdry election cycle? Some inspiration for tackling what lies ahead? A good way to enrich Advent? Examples of sanctity to help you be the missionary disciple you were baptized to be? Then let me recommend Bishop Robert Barron’s new DVD series, Catholicism: The Pivotal Players.

Pivotal Players is a follow-up to Bishop Barron’s immensely successful, ten-part mega-series, Catholicism, the most compelling presentation of the symphony of Catholic truth ever created for modern media. Key figures in Catholic history appeared throughout the original series to illustrate this truth of the faith or that facet of the Catholic experience. Now, with Pivotal Players, six of the most striking personalities in Catholic history take center stage, the adventure of their lives serving to deepen our understanding of the “faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3).

The six are Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Siena, Thomas Aquinas, John Henry Newman, G.K. Chesterton, and Michelangelo Buonarroti: the reformer, the mystic, the theologian, the convert, the evangelist, and the artist. Two are doctors of the Church – and a third may be one day. Several of them inspired successors of St. Peter; another told a pope off in no uncertain terms. Two were Englishmen and converts from Anglicanism: one, will-o-the-wisp slight and the other gargantuan; one the quintessential Oxford don, the other, the quintessential Anglo-eccentric genius. One grew up a wannabe knight errant before his abrupt turn into radical evangelicalism. Still another was arguably the greatest genius in human history, his extraordinary talents ranging across sculpture, painting, architecture, poetry and other fields. Four were Italians (if you’ll permit the anachronism for an Umbrian, a Sienese, a sort-of Neapolitan, and a devout Florentine). Each of them was the human analogue to what astrophysicists call a “singularity,” someone to whom the old rules of spiritual gravitation didn’t apply.

And they shared something else in common besides the passionate intensity of their Catholic faith: each lived at a time of crisis for the Church, and each helped the Church address that crisis creatively while remaining true to itself.

Francis of Assisi and Catherine of Siena lived at times when institutional Catholicism had become complacent, losing its evangelical edge. By creating something utterly new in Catholic life – the mendicant religious order dedicated to evangelization – Francis inspired in the Church a new Gospel radicalism centered on the joyful experience of salvation. By persuading (perhaps better, shaming) Pope Gregory XI to return to Rome from his political exile in Avignon, Catherine of Siena made it possible for the papacy to be again the center of unity for the entire Catholic world, as Christ intended it to be.

Thomas Aquinas, for his part, grafted the “new learning” of Aristotle into Catholic theology in a creative synthesis that gave the Church conceptual tools that remain powerful today. In doing so, he helped create what we know in the West as higher education, even as he showed the Church how to incorporate the best of the “modernity” of his time into its intellectual and spiritual life without losing touch with the truths it had long possessed as a bequest from the Lord.

Michelangelo lived during that moment of sometimes-brash human assertiveness we call the Renaissance; his theologically-driven art (which Bishop Barron explains in perhaps the most scintillating part of Pivotal Players) enriched the classically-inspired humanism of his day by marrying it to the biblical account of the human person.

Newman and Chesterton, closer to our moment, were key figures in crafting a Catholic response to the scientific revolution and the other dramatic changes that were reshaping how we think about things – and imagine our place in the scheme of things – during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That each of them did so in wonderfully winsome prose helped demonstrate the continuing vitality of the Catholic mind and spirit in an increasingly skeptical age, even as they bequeathed to the 21st-century Church models of apologetics that remain cogent at a time like ours, when skepticism has often hardened into cynicism, or just plain boredom.

There are important things to be learned from each of these God-touched human personalities for the challenges Catholicism faces in the post-modern world of the twenty-first century. Kudos to Bishop Barron for bringing those things to our attention in a gripping way.

November 4, 2016

What Is Really At Stake for Catholic Voters in this Election | HPR Editorial

What Is Really At Stake for Catholic Voters in this Election | Fr. David Vincent Meconi, SJ | HPR Editorial

In his Republic, Plato argues that we all get the government we deserve. That is, the political leaders of any given people are a direct reflection of what those people hold dear. Does a society think riches are the defining characteristic of excellence? Their leaders will no doubt be elected because they are billionaires. Does a society think military might is the most important factor? The leaders of that citizenry will be hawkish soldiers, mindful of nothing but their own ability to dominate.

These days, we all have our minds on government. The political wrangling, insincere promises, and shameless currying of favor has filled our ears and souls for many, many months now. Many in the country have been attracted to the fresh (yet, candidly too fresh) voice and bravado of Trump; many find Clinton’s supposed solicitude for the under-served comforting. I doubt many of us trust either of them, surely neither fully, but their candidacies have only reminded me how far ahead the Church is in proclaiming truth, the dignity of human freedom, the true nature of liberty and the common good. No party can do what the Church does, not even come close, as the prophets will always outrun the politicians. So what are we to do? Fr. John Lankeit of the Diocese of Phoenix fed his faithful with a sermon treating the 2016 presidential election from one of the best Catholic perspectives I have heard from the pulpit in a very long time (if you haven’t watched it, please do so).

Fr. Lankeit also begins by reminding us that we faithful Catholics will never find a lasting home here. But that does not mean we become so other-worldly that we neglect this one! As Americans, we all have the responsibility to vote; and as Catholic, we all have the duty to vote rightly. In his sermon, Fr. Lankeit teaches the faithful that we are surrounded by a myriad of important issues, and that living as a Catholic in America is not always an easy thing. Yet, political issues must be ordered properly: the depletion of our inner-cities, financial matters, racial injustice, healthcare, and the other items on both the Democratic and Republican platforms are all of concern. But they are not of equal concern, and the wise person is able to distinguish between those things which can allow for leeway and thus disagreement, and those issues which are absolute and cannot allow for any latitude.

Therefore, we hear how Fr. Lankeit leads his flock through an exercise of self-reflection, meant for all of us. He never names names, and he never insists on the superiority of one party over another. What he does do is simply hold up a mirror to the American voter to have each of us reflect on what we think is essential in the building up of our great nation.

November 3, 2016

New: "General Escobar's War: A Novel of the Spanish Civil War" by José Luis Olaizola

Now available from Ignatius Press:

General Escobar's War: A Novel of the Spanish Civil War

by José Luis Olaizola

Appearing here in English translation for the first time, General Escobar's War won Spain's prestigious Planeta Prize for fiction. The historical novel takes the form of an imagined diary by General Antonio Escobar, the highest-ranking officer of the Republican Army remaining in Spain at the end of the Spanish Civil War, while he awaited trial and execution.

Besides being a vivid reminder of how destructive political passions can be, General Escobar's War is also a profoundly intimate portrait of an inspiring man. By his decisive action on July 19, 1936, Escobar, then a Civil Guard colonel and a man of profound religious conviction, succeeded in thwarting the military uprising in Barcelona.

Although his father was a hero of the Spanish-American War in Cuba, his daughter was a nun, and one of his sons was a Falangist fighter, Escobar freely chose to defend the Republic in accordance with his oath to support the legally constituted government.

The author gives a rare perspective of the Spanish Civil War, free of partisanship and ideology, through a soldier who, in Spain's great historic schism, chose to take a deeply uncomfortable stance because he believed his duty called him to do so.

José Luis Olaizola is an award-winning Spanish author of more than 70 books. He is known throughout the Spanish-speaking world for his works on great historical figures such as El Cid, Hernán Cortés, and Bartolomé de las Casas. Fire of Love, his novel about Saint John of the Cross, is also published by Ignatius Press.

"A wonderful book that explores the experience of a brave and honorable soldier, a faithful Catholic. His true story, here fluently translated, is told with moving sensitivity and an admirable lightness of touch."

— Lucy Beckett, Author, Postcard from the Volcano, and winner of the Aquinas Award for Fiction

"Many books are called 'brave' without cause, but this one is the genuine article-a truly courageous and insightful work. The reader is forced to consider the heartbreaking choices faced by anyone who has lived to see his country so cruelly divided."

— Fiorella De Maria , Author, We'll Never Tell Them

"Like all good historical fiction, this novel brings the past to graphic and disturbing light. It also shows the dignity of the human person in the midst of the ugliness of war."

— Joseph Pearce, Author, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G.K. Chesterton

"The fatalistic first person narrative is haunted by Escobar's resigned courage as he clings to his honor and his faith in a time when both were dangerous."

— Michael Richard, Author, Tobit's Dog

November 2, 2016

To Trace All Souls Day

To Trace All Souls Day | Fr. Brian Van Hove, S.J. | Ignatius Insight

As Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger once said so well, one major difference between Protestants and Catholics is that Catholics pray for the dead:

"My view is that if Purgatory did not exist, we should have to invent it." Why?

"Because few things are as immediate, as human and as widespread—at all times and in all cultures—as prayer for one"s own departed dear ones." Calvin, the Reformer of Geneva, had a woman whipped because she was discovered praying at the grave of herson and hence was guilty, according to Calvin, of superstition". "In theory, the Reformation refuses to accept Purgatory, and consequently it also rejects prayer for the departed. In fact German Lutherans at least have returned to it in practice and have found considerable theological justification for it. Praying for one's departed loved ones is a far too immediate urge to be suppressed; it is a most beautiful manifestation of solidarity, love and assistance, reaching beyond the barrier of death. The happiness or unhappiness of a person dear to me, who has now crossed to the other shore, depends in part on whether I remember or forget him; he does not stop needing my love." [1]

Catholics are not the only ones who pray for the dead. The custom is also a Jewish one, and Catholics traditionally drew upon the following text from the Jewish Scriptures, in addition to some New Testament passages, to justify their belief:

Then Judas assembled his army and went to the city of Adulam. As the seventh day was coming on, they purified themselves according to the custom, and they kept the sabbath there. On the next day, as by that time it had become necessary, Judas and his men went to take up the bodies of the fallen and to bring them back to lie with their kinsmen in the sepulchres of their fathers. Then under the tunic of every one of the dead they found sacred tokens of the idols of Jamnia, which the law forbids the Jews to wear. And it became clear to all that this was why these men had fallen. So they all blessed the ways of the Lord, the righteous Judge, who reveals the things that are hidden; and they turned to prayer, beseeching that the sin which had been committed might be wholly blotted out. And the noble Judas exhorted the people to keep themselves free from sin, for they had seen with their own eyes what had happened because of the sin of those who had fallen. He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In doing this he acted very well and honourably, taking account of the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin. [2]

Besides the Jews, many ancient peoples also prayed for the deceased. Some societies, such as that of ancient Egypt, were actually "funereal" and built around the practice. [3] The urge to do so is deep in the human spirit which rebels against the concept of annihilation after death. Although there is some evidence for a Christian liturgical feast akin to our All Souls Day as early as the fourth century, the Church was slow to introduce such a festival because of the persistence, in Europe, of more ancient pagan rituals for the dead. In fact, the Protestant reaction to praying for the dead may be based more on these survivals and a deformed piety from pre-Christian times than on the true Catholic doctrine as expressed by either the Western or the Eastern Church. The doctrine of purgatory, rightly understood as praying for the dead, should never give offense to anyone who professes faith in Christ.

When we discuss the Feast of All Souls, we look at a liturgical commemoration which pre-dated doctrinal formulation itself, since the Church often clarifies only that which is being undermined or threatened. The first clear documentation for this celebration comes from Isidore of Seville (d. 636; the last of the great Western Church Fathers) whose monastic rule includes a liturgy for all the dead on the day after Pentecost. [4] St. Odilo (962-1049 AD) was the abbot of Cluny in France who set the date for the liturgical commemoration of the departed faithful on November 2.

Before that, other dates had been seen around the Christian world, and the Armenians still use Easter Monday for this purpose. He issued a decree that all the monasteries of the congregation of Cluny were annually to keep this feast. On November 1 the bell was to be tolled and afterward the Office of the Dead was to be recited in common, and on the next day all the priests would celebrate Mass for the repose of the souls in purgatory. The observance of the Benedictines of Cluny was soon adopted by other Benedictines and by the Carthusians who were reformed Benedictines. Pope Sylvester in 1003 AD approved and recommended the practice. Eventually the parish clergy introduced this liturgical observance, and from the eleventh to the fourteenth century it spread in France, Germany, England, and Spain.

Finally, in the fourteenth century, Rome placed the day of the commemoration of all the faithful departed in the official books of the Western or Latin Church. November 2 was chosen in order that the memory of all the holy spirits, both of the saints in heaven and of the souls in purgatory, should be celebrated in two successive days. In this way the Catholic belief in the Communion of Saints would be expressed. Since for centuries the Feast of All the Saints had already been celebrated on November first, the memory of the departed souls in purgatory was placed on the following day. All Saints Day goes back to the fourth century, but was finally fixed on November 1 by Pope Gregory IV in 835 AD. The two feasts bind the saints-to-be with the almost-saints and the already-saints before the resurrection from the dead.

Incidentally, the practice of priests celebrating three Masses on this day is of somewhat recent origin, and dates back only to ca. 1500 AD with the Dominicans of Valencia. Pope Benedict XIV extended it to the whole of Spain, Portugal, and Latin America in 1748 AD. Pope Benedict XV in 1915 AD granted the "three Masses privilege" to the universal Church. [5]

On All Souls Day, can we pray for those in limbo? The notion of limbo is not ancient in the Church, and was a theological extrapolation to provide explanation for cases not included in the heaven-purgatory-hell triad. Cardinal Ratzinger was in favor of its being set aside, and it does not appear as a thesis to be taught in the new Universal Catechism of the Catholic Church. [6]

The doctrine of Purgatory, upon which the liturgy of All Souls rests, is formulated in canons promulgated by the Councils of Florence (1439 AD) and Trent (1545-1563 AD). The truth of the doctrine existed before its clarification, of course, and only historical necessities motivated both Florence and Trent to pronounce when they did. Acceptance of this doctrine still remains a required belief of Catholic faith.

What about "indulgences"? Indulgences from the treasury of grace in the Church are applied to the departed on All Souls Day, as well as on other days, according to the norms of ecclesiastical law. The faithful make use of their intercessory role in prayer to ask the Lord"s mercy upon those who have died. Essentially, the practice urges the faithful to take responsibility. This is the opinion of Michael Morrissey:

Against the common juridical and commercial view, the teaching essentially attempts to induce the faithful to show responsibility toward the dead and the communion of saints. Since the Church has taught that death is not the end of life, then neither is it the end of our relationship with loved ones who have died, who along with the saints make up the Body of Christ in the "Church Triumphant."

The diminishing theological interest in indulgences today is due to an increased emphasis on the sacraments, the prayer life of Catholics, and an active engagement in the world as constitutive of the spiritual life. More soberly, perhaps, it is due to an individualistic attitude endemic in modern culture that makes it harder to feel responsibility for, let alone solidarity with, dead relatives and friends. [7]

As with everything Christian, then, All Souls Day has to do with the mystery of charity, that divine love overcomes everything, even death. Bonds of love uniting us creatures, living and dead, and the Lord who is resurrected, are celebrated both on All Saints Day and on All Souls Day each year.

All who have been baptized into Christ and have chosen him will continue to live in Him. The grave does not impede progress toward a closer union with Him. It is only this degree of closeness to Him which we consider when we celebrate All Saints one day, and All Souls the next. Purgatory is a great blessing because it shows those who love God how they failed in love, and heals their ensuing shame. Most of us have neither fulfilled the commandments nor failed to fulfill them. Our very mediocrity shames us. Purgatory fills in the void. We learn finally what to fulfill all of them means. Most of us neither hate nor fail completely in love. Purgatory teaches us what radical love means, when God remakes our failure to love in this world into the perfection of love in the next.

As the sacraments on earth provide us with a process of transformation into Christ, so Purgatory continues that process until the likeness to Him is completed. It is all grace. Actively praying for the dead is that "holy mitzvah" or act of charity on our part which hastens that process. The Church encourages it and does it with special consciousness and in unison on All Souls Day, even though it is always and everywhere salutary to pray for the dead.

ENDNOTES:

[1] See Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church, with Vittorio Messori (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985) 146-147. Michael P. Morrissey says on the point: "The Protestant Reformers rejected the doctrine of purgatory, based on the teaching that salvation is by faith through grace alone, unaffected by intercessory prayers for the dead." See his "Afterlife" in The Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality, ed. Michael Downey (Collegeville: Michael Glazier/Liturgical Press, 1993) 28.

[2] Maccabees 12:38-46. From The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version, Containing the Old and New Testaments. Catholic Edition. (London: The Catholic Truth Society, 1966) 988-989. Neil J. McEleney, CSP, adds: "These verses contain clear reference to belief in the resurrection of the just...a belief which the author attributes to Judas ...although Judas may have wanted simply to ward off punishment from the living, lest they be found guilty by association with the fallen sinners.... The author believes that those who died piously will rise again...and who can die more piously than in a battle for God"s law? ...Thus, he says, Judas prayed that these men might be delivered from their sin, for which God was angry with them a little while.... The author, then, does not share the view expressed in 1 Enoch 22:12-13 that sinned- against sinners are kept in a division of Sheol from which they do not rise, although they are free of the suffering inflicted on other sinners. Instead, he sees Judas"s action as evidence that those who die piously can be delivered from unexpiated sins that impede their attainment of a joyful resurrection. This doctrine, thus vaguely formulated, contains the essence of what would become (with further precisions) the Christian theologian's teaching on purgatory." See The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, ed. Raymond E. Brown, SS, etal., art. 26, "1-2 Maccabees" (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1990) 446. Gehinnom in Jewish writings is more appropriately understood as a purgatory than a final destination of damnation.

[3] Spanish-speaking Catholics today popularly refer to All Souls Day as "El Día de los Muertos", a relic of the past when the pre- Christian Indians had a "Day of the Dead"; liturgically, the day is referred to as "El Día de las Animas". Germans call their Sunday of the Dead "Totensonntag". The French Jesuit missionaries in New France in the seventeenth century easily explained All Souls Day by comparing it to the the local Indian "Day of the Dead". The Jesuit Relations are replete with examples of how conscious were the people of their duties toward their dead. Ancestor worship was also well known in China and elsewhere in Asia, and missionaries there in times gone by perhaps had it easier explaining All Souls Day to them, and Christianizing the concept, than they would have to us in the Western world as the twentieth century draws to a close.

[4] See Michael Witczak, "The Feast of All Souls", in The Dictionary of Sacramental Worship, ed. Peter Fink, SJ, (Collegeville: Michael Glazier/Liturgical Press, 1990) 42.

[5] "Three Masses were formerly allowed to be celebrated by each priest, but one intention was stipulated for all the Poor Souls and another for the Pope"s intention. This permission was granted by Benedict XV during the World War of 1914-1918 because of the great slaughter of that war, and because, since the time of the Reformation and the confiscation of church property, obligations for anniversary Masses which had come as gifts and legacies were almost impossible to continue in the intended manner. Some canonists believe Canon 905 of the New Code has abolished this practice. However, the Sacramentary, printed prior to the Code, provides three separate Masses for this date." See Jovian P. Lang, OFM, Dictionary of the Liturgy (New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1989) 21. Also see Francis X. Weiser, The Holyday Book (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1956) 121-136.

[6] Ratzinger stated: "Limbo was never a defined truth of faith. Personally—and here I am speaking more as a theologian and not as Prefect of the Congregation—I would abandon it since it was only a theological hypothesis. It formed part of a secondary thesis in support of a truth which is absolutely of first significance for faith, namely, the importance of baptism. To put it in the words of Jesus to Nicodemus: "Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God" (John 3:5). One should not hesitate to give up the idea of "limbo" if need be (and it is worth noting that the very theologians who proposed "limbo" also said that parents could spare the child limbo by desiring its baptism and through prayer); but the concern behind it must not be surrendered. Baptism has never been a side issue for faith; it is not now, nor will it ever be." See Ratzinger, The Ratzinger Report, 147-148.

[7] Morrissey, "Afterlife" in The Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality, 28-29.

This article was originally published, in a slightly different form, as "To Trace All Souls Day," in The Catholic Answer, vol. 8, no. 5 (November/December 1994): 8-11.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• On November: All Souls and the "Permanent Things" | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Death, Where Is Thy Sting? | Adrienne von Speyr

• Purgatory: Service Shop for Heaven | Reverend Anthony Zimmerman

• The Question of Hope | Peter Kreeft

• The Next Life Is a Lot Longer Than This One | Mary Beth Bonacci

• My Imaginary Funeral Homily | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Do All Catholics Go Straight to Heaven? | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Be Nice To Me. I'm Dying. | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Are God's Ways Fair? | Ralph Martin

• The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Cross and The Holocaust | Regis Martin

• From Defeat to Victory: On the Question of Evil | Alice von Hildebrand

November 1, 2016

The saints are sealed, called, and saved by God

"Christ Glorified in the Court of Heaven" (1428-30) by Fra Angelico [WikiArt.org]

by Carl E. Olson | The Dispatch at CWR

A passage from The Apocalypse is read on the Solemnity of All Saints because it describes the reason we were created: to be holy ones

Readings:

• Rev 7:2-4, 9-14

• Psa 24:1BC-2, 3-4AB, 5-6

• 1 Jn 3:1-3

• Mt 5:1-12a

Many readers are understandably confused or puzzled when hearing a passage from the Book of Revelation. It is unfortunate, however, that many end up dismissing what they’ve heard. In so doing, they miss out on some of the most joyful passages of sacred Scripture. Yes, that's right—joyful.

Today’s first reading is a perfect example of such a passage. It is read on the Solemnity of All Saints because it describes the reason we were created. Using a multitude of references to the Old Testament, John the Revelator shows what it means to be a saint, a “holy one.” I wish to highlight three of the characteristics shared by all saints revealed in the seventh chapter of The Apocalypse. The word apokalypsis, by the way, refers to an “unveiling”—primarily of Jesus Christ, of course, but also of God’s fulfilled work of salvation and his plan for each of us.

The first characteristic of all the saints is they are sealed by God. Prior to judgment being sent from the throne room of heaven upon the wickedness of man, the servants of God are to be sealed, or marked, and thus set apart as holy. This imagery is drawn from the ninth chapter of Ezekiel, which describes the Lord commanding a mysterious “man clothed in linen” to go through Jerusalem and “put a mark upon the foreheads of the men who sigh and groan over all the abominations that are committed in it” (Ezek. 9:3-4). Those who loved God and who hated sin were saved; all others perished. The mark described by Ezekiel would protect the righteous Israelites from four rapidly approaching judgments, to be carried out by Babylon (another name used often in the Book of Revelation).

Jesus was set apart by the Father with a seal (Jn. 6:27). Those who are baptized into Christ are also marked, with the seal of the Holy Spirit, which is both familial and judicial in nature. Those marked by God belong to him; they are now of his household—the Church—and are under his authority and protection from eternal damnation (see Catechism, pars. 1295-6).

The second characteristic of saints, which builds on the first, is that they are servants and sons of God.

October 27, 2016

New: "Catholics Confronting Hitler: The Catholic Church and the Nazis"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

Catholics Confronting Hitler: The Catholic Church and the Nazis

by Peter Bartley

Written with economy and in chronological order, this book offers a comprehensive account of the response to the Nazi tyranny by Pope Pius XII, his envoys, and various representatives of the Catholic Church in every country where Nazism existed before and during WWII.

Peter Bartley makes extensive use of primary sources – letters, diaries, memoirs, official government reports, German and British. He manifestly quotes the works of several prominent Nazis, of churchmen, diplomats, members of the Resistance, and ordinary Jews and gentiles who left eye-witness accounts of life under the Nazis, in addition to the wartime correspondence between Pius XII and President Roosevelt.

This book reveals how resistance to Hitler and rescue work engaged many churchmen and laypeople at all levels, and was often undertaken in collaboration with Protestants and Jews. The Church paid a high price in many countries for its resistance, with hundreds of churches closed down, bishops exiled or martyred, and many priests shot or sent to Nazi death camps.

Bartley also explores the supposed inaction of the German bishops over Hitler's oppression of the Jews, showing that the Reich Concordat did not deter the hierarchy and clergy from protesting the regime's iniquities or from rescuing its victims. While giving clear evidence for Papal condemnation of the Jewish persecution, he also explains why Pius XII could not completely set aside the language of diplomacy and be more openly vocal in his rebuke of the Nazis.

Peter Bartley, was born in England and educated at Plater College, Oxford, receiving a degree in Political Science. He has written for various UK publications, and is the author of two other books, The Gospel of Jesus: Fact or Fiction?, and Mormonism: The Prophet, the Book, the Cult.

October 25, 2016

The Liberty of Dogma vs. the Tyranny of Taste

St. John the Apostle, a portrait from the Book of Kells, c. 800 (Wikipedia)

The Liberty of Dogma vs. the Tyranny of Taste | Carl E. Olson | Catholic World Report

Those who say that doctrines must serve the Church's pastoral mission have both inverted the proper order of things and placed sentiment above shepherding.

Years ago I wrote an article titled "Dogma is Not a Dirty Word". In it, I noted how those who criticize the Church for being "dogmatic" fail to understand that everyone is dogmatic in a very real sense, as G.K. Chesterton noted in his 1905 book Heretics: "Man can be defined as an animal that makes dogmas. . . . Trees have no dogmas." Along those same lines, in 1928, Chesterton observed, “There are two kinds of people in the world, the conscious dogmatists and the unconscious dogmatists. I have always found myself that the unconscious dogmatists were by far the most dogmatic.”

In fact, the unconscious dogmatist has a funny way of dogmatically insisting he is entirely free of dogma—or, at the very least, he has attained a special perch above and beyond the clutches of dogma and doctrine, which are sources of discord, confusion, and contention. Examples abound within the secular realm. Far more disconcerting, however, are examples and instances within the Church. As when, to draw upon my dusty article, we encounter those who declare "that real ecumenism and real Christianity are not found in dry formulas but in the 'spirit of Christ.' Much is made of 'love' or 'sincerity' but often with little or no reference to the kind of demanding, self-denying life of holiness that Jesus set before his disciples."

This came to mind upon reading a recent Crux interview with Bishop William Kenney of the Archdiocese of Birmingham, who was appointed by Pope Francis in 2013 to be, as his online bio states, "co-chair of the international conversations between the Lutheran and Catholic Churches." It's not that Bishop Kenney is unaware of various theological or doctrinal concerns, but it appears he has happily moved past them, saying:

The things that we thought caused the Reformation have been taken away- the excommunication of the Lutherans was lifted, the condemnation of the Catholics were lifted. That is the formal Churches’ position now, it is not just a theological proposition. There are those who say this has already achieved unity; it is certainly a major step forward, and it has removed most of the problems of the Reformation.

Yes, he acknowledges, the "women priests question is complicated", but he then muses that when it comes to the Eucharist, "Lutherans have more or less the same doctrine as we have." How much more, or in what way less is not clear. But does it really matter? Apparently not. "Would Martin Luther have been excommunicated today? The answer is no, he probably wouldn’t. And he did not want to split the Church - he came to that, but it’s not where he began." In truth, contra the bishop's Monday morning quarterbacking, Luther was a man of many moods and many positions, perhaps even multiple personalities. As Dr. Christopher Malloy, a theologian who has studied and written extensively on Catholic-Lutheran matters, said to me in a lengthy June 2007 Ignatius Insight interview: "We need to pay attention to the following question: 'Which Lutheranism? Whose Luther?'"

Not to worry, however, as Bishop Kenney serenely assures readers:

October 24, 2016

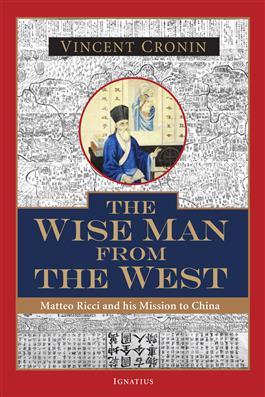

New: "The Wise Man from the West: Matteo Ricci and His Mission to China"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Wise Man from the West: Matteo Ricci and His Mission to China

by Vincent Cronin

This is the amazing story of the famous Jesuit missionary priest to China, Fr. Matteo Ricci, revered as a "Wise Man" by the Chinese. He arrived in China in 1582 and died there twenty-eight years later, having developing a deep knowledge of and love for the country, the culture and the people.

Before Ricci's heroic mission, China was an unexplored land bordering on the vague, mysterious Cathay, and the West was no more than a rumor to the learned Mandarins, a distant unknown region lying beyond the bounds of geography. In the person of Father Ricci these two worlds met, and Vincent Cronin dramatically recreates the romance, the crossed purposes, the potential tragedy of that meeting. He shows us ancient China, the timeless state, with a civilization older than that wherein Christianity first found expression.

Because Ricci loved this civilization and honored it, he was able to teach his strange new Christian doctrine with tact and sympathy. He carried much of the technological and philosophical wisdom of the late Renaissance Europe, and thus found favor among the Mandarins, the men of learning who enjoyed high status at the Imperial Court. He learned Chinese to discuss with them the problems in science and technology, and also questions of religion and the hereafter. He lived as a great scholar among great scholars and left behind him a memory worthy of the Christian faith he served.

Well researched and written with an enchanting style, Cronin relied almost entirely on contemporary material only recently assembled, including Father Ricci's own letters and reports, and his account of China written in Peking before his death. The seed of Faith was sown and the crop, even after a century of atheistic communism, continues to grow in present-day China.

Vincent Cronin (1924-2011), was a British historical, cultural, and biographical writer, well-known for his many historical biographies and for his two-volume history of the Renaissance. Acclaimed for his scholarly and elegantly written works, he was as one of the finest popular historians of his generation, best known for his biographies of of Louis XIV, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Catherine the Great, and Napoleon.

"Matteo Ricci was, by any standards, an extraordinary man. One concludes from reading this riveting book just how pertinent Ricci remains to both modern China and to the Church, ever ancient and ever new."

— James V. Schall, S.J., From the Foreword

"A book which does for once deserve the all too lightly used adjective 'outstanding.' "

— Honor Tracy, New Statesman

"A delightfully told story of a truly remarkable man."

— Rodney Gilbert, New York Herald Tribune

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers