Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 87

July 19, 2014

Weeds, Seeds, and the Kingdom of Heaven

"Wheat Field" (1888) by Vincent van Gogh (Wikiart.org)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, July 20, 2014 | Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Wis 12:13, 16-19

• Ps 86:5-6, 9-10, 15-16

• Rom 8:26-27

• Mt 13:24-43

What is the Kingdom of God? How does it come about? And how will it grow?

These are some of the questions addressed in the parables of Jesus, including the seven parables found in Matthew 13. As we saw last week, these parables are not simply stories with a moral, nor are they theological tracts or even pithy catechetical lessons. Parables are not, writes Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis in Fire of Mercy, Heart of the World (Ignatius Press, 2003), “a test of human intelligence that functions like riddles. Rather they are verbal strategies of grace that test the willingness of the human heart to surrender to, and be enfolded by, the always surprising generosity of Wisdom.”

Leiva-Merikakis describes a parable, strikingly, as “a coded letter left by a Lover” (p 192). He points out that the original Greek renditions of the parables are imbued with a beautiful musicality, adding even more meaning to Jesus’ exhortation: “He who has ears, let him hear” (Mt 13:9). God’s love for mankind is such that the eternal Word uses words of beauty to redeem our souls and transform our hearts.

Today’s Gospel reading contains three of the seven parables: the parables of the weeds among the wheat, the mustard seed, and the yeast (or leaven). Like the parable of the sower and seeds heard last week, all three express something about the growth of the Kingdom and how God’s word brings about that mysterious—and often unseen—growth.

Like the parable of the sower and the seeds, the parable of the weeds among the wheat has an agricultural setting. However, the parable is unique to Matthew’s Gospel and does not appear in the other Gospels. The focus is less on the response of the soil to the sower’s seeds and more on the mystery of evil and how it grows alongside what the Son of Man has planted in the field of the world. In his explanation of the parable to the disciples, Jesus draws a stark contrast between the children of the kingdom and the children of the evil one. Those who hear the word of God and reject it are the children of Satan. Having been offered light, they choose darkness (cf., Jn 1:9-11; 3:19-20).

But, as Saint Augustine noted, what is currently wheat can become a weed, and what is a weed can still become wheat “and no one knows what they will be tomorrow.” It is right to lament the sins committed by sons and daughters of the Church. But we shouldn’t be blind to our own weaknesses, nor to the ravenous appetite of the devil, who “is prowling around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour” (1 Pet 5:8). Mindful of our failings, as the Apostle Paul exhorts the Romans in today’s epistle, we must trust in the Holy Spirit, who “comes to the aid of our weakness, for we do not know how to pray as we ought.”

The parable of the mustard seed, although short, is memorable in its imagery, especially in the comparison between the largeness of the bush (growing to ten feet in height) and the smallness of the seed. Its central meaning is that the works of God often begin in small ways and are usually ignored or missed by the world. The temptation for the children of the Kingdom is to become impatient, forgetting that this tree has now been growing for thousands of years, and will continue to grow until the end of time.

Even shorter is the parable of the yeast, or leaven. From what seems to be of little consequence comes a super abundance, a theme echoing the reality of the Incarnation and the stunning truth of the empty tomb. It is Christ, the lover of mankind, who is the leaven. And it is through his death and Resurrection and by his Body and Blood that we are leavened—transformed and transferred into the always growing kingdom of the Son (Col 1:13).

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the July 20, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

July 18, 2014

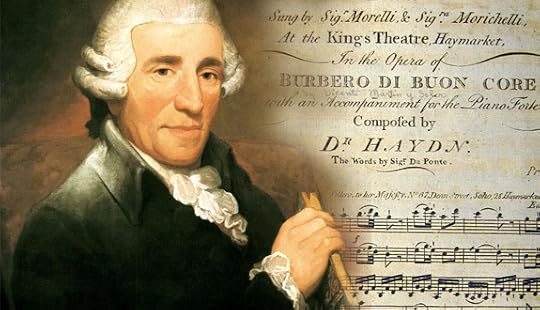

“Too Late Have I Loved Thee”: On the Genius of Franz Joseph Haydn

“Too Late Have I Loved Thee”: On the Genius of Franz Joseph Haydn | R. J. Stove | Catholic World Report

He seems to need rediscovering with each new generation. And by the way, let’s lose the fatuous “Papa Haydn” tag.

Strange how certain extremely famous creators are not really famous after all. For proof of this sub-Chestertonian paradox, consult Franz Joseph Haydn, who seems in many respects the musical counterpart to Mark Twain’s definition of a literary classic: “something that everyone wants to have read and nobody wants to read.” The normally perspicacious Schumann—possibly misled by the “Papa” which common usage all too swiftly attached to Haydn’s name —dismissed Haydn as “a familiar friend of the house whom all greet with pleasure and with esteem but who has ceased to arouse any particular interest.” Tchaikovsky remained only slightly more enthusiastic: “I also like some things of Haydn.” Kingsley Amis, in 1982, exhibited downright contempt: “Except perhaps for J.S. Bach, Haydn was the laziest of the great composers.” (Proof, if we required proof, that a verdict once passed upon Belloc fits Amis still more: “As he grew older the rather juvenile desire to ‘shock’ grew stronger and not weaker.”)

Overall it is surprising how accurate the remark credited both to pianist Paul Badura-Skoda and musicologist Sir Donald Tovey—“Haydn The Unknown”—continues to be now. For Cincinnati-based editor Donald Vroon, writing in 1992, “Haydn is almost like a secret.” Two years beforehand, former New York Times critic Joseph Horowitz had provided mostly illuminating specifics about this quasi-clandestine role:

[Haydn] … holds limited popular appeal. He is not a sufferer, a lover, a confessor, a combatant—all the personae we expect our heroic musical executants to embody. His knowing wit and repartee privately gratify the attuned interpreter. Interpreters otherwise attuned—to a mass public, for instance—smooth away his subversive detail, transforming him into a cut-rate Mozart.

In one respect Horowitz's conclusion is inept because parochial. Outside the New York Times mindset, no automatic contradiction exists between “a mass public” and Haydn's output.

July 16, 2014

Teaching the Faith: Contributions from Thomas Aquinas

Teaching the Faith: Contributions from Thomas Aquinas | Brother Michael Weibley, O.P. | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

God’s love, mediated through the articles of faith, is a communication of God’s love speaking to us. Those who hear, and cling to the merciful speech of God, in faith, are the ones who attain this saving knowledge.

“But when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” – Luke 18:8

This is a striking, and relevant, question. It has become somewhat common to note the inadequate retention rates of many RCIA and sacramental catechesis programs in parishes. Recent converts cycle in and out of programs, seemingly designed to teach the faith, only to find at the end of the program that they are still incapable of connecting to an authentic faith life in the Church. Many pastors will see people walk into their parishes, then quickly walk back out. The poignancy of Jesus’ question for the Church of the 21st century is, therefore, very much relevant. The problem, naturally, elicits another question: What are some solutions to the need for robust and abiding catechesis at the parish level?

Looking to the traditions of the Church, any catechist will inevitably fall upon the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas. One encounters in Aquinas a master of theological understanding. He was a man guided by the Holy Spirit, who pursued the science of God in wisdom and truth, which directed his every teaching towards the goal of every man: eternal life. Aquinas was not purely an academic, but a man who found his abiding attraction to God in the love that God first had for him. It was this love that urged him to write his Summa Theologiae for the sake of beginners, so that they, too, could be ever pointed toward their final goal and lead others in that direction. Likewise, it is the goal of every catechist to orient his or her students to that same end. Recourse to Aquinas’ method of teaching, therefore, is certainly relevant for the catechist of the 21st century.

In this short essay, I will draw upon the prevailing wisdom of Aquinas and his importance for catechists today. I will first outline Aquinas’ thought on the role of teaching, using the structure of the Summa Theologiae as an example of theological teaching. Next, I will develop how his thought on teaching corresponds to his teaching on the Articles of Faith. In summation, I will describe how the wisdom of Aquinas provides a model for catechists today in orienting their students towards the goal of Christian life.

Aquinas on Teaching

Aquinas saw the reality and dignity of being a human person in the fact that the individual is able to come to know the truth and choose the good.

July 14, 2014

Home and School in American Catholic Life

Home and School in American Catholic Life | Joseph T. Stuart | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The Church in America needs both homeschooling, and Catholic schools. Homeschooling provides a bold reminder to priests, bishops, and government leaders that parents are the first educators of their children.

The education of children within the home is booming nationwide. In Bismarck, North Dakota, where I live, over one hundred families participate in the local homeschool group (there are more, besides) even as private schools, both Protestant and Catholic, thrive. Often homeschool and Catholic school families attend the same parishes, and know each other, but sometimes there is little interaction, and even less mutual understanding, between them. Catholic schools are condemned as not Catholic enough, and homeschooling is attacked because everyone knows of a family in which the “schooling” left much to be desired. This essay argues that understanding the historical reasons why Catholic schools and, later, homeschooling arose to help one to see how both can contribute to the revitalization of a Catholic subculture and an American society in complementary ways.

Those historical reasons clustered around an antagonistic relationship between home and school that developed in the past. In the 19th century, Catholics resisted Protestant control of public education, giving rise to their own system. In the 20th century, home and school could be increasingly at odds because of changes in American civil religion that inhibited the transmission of Christian faith. In addition, some families came to see education in consolidated schools far removed from the home as damaging to domestic life. I will argue that this dual history of shifting relationships, between home and school, points to important principles for religious and social renewal in 21st century America: Catholic schools can provide a base for flourishing Catholic subcultures and evangelization, while homeschooling can enrich domestic culture, and function as a “check and balance” on schools to remain true to their mission of educating the whole person. In turn, flourishing homes and schools encourage that subsidiarity of rightly-ordered power structures helping to check the spread of politics into social life.

The Rise of Antagonism

While laws in the colonial era requiring parental home education of children eventually disappeared, the lives of pre-industrial Americans continued by necessity to revolve around their homes for generations.

Unveiling the Tactics (and Tantrums) of Tyrannical Feminists

Supporters of legal abortion and the federal contraceptive mandate demonstrate outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington June 30. (CNS photo/Jonathan Ernst, Reuters)

Unveiling the Tactics (and Tantrums) of Tyrannical Feminists | Carrie Gress | Catholic World Report

The concocted “war on women” is sheer marketing genius; it is also angry, irrational, and dishonest.

The Hobby Lobby case pass set off an unabating, shrill firestorm. Late last week, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi issued this warning about the Supreme Court: “We should be afraid about this court … five men can decide if a woman can use a diaphragm.” Somehow, poor Nancy misread the case.

Among the publishable screeds – many others are too crass to even quote – there is an odd, recurring pattern: like Pelosi, very few actually address the real issues of the case. Hillary Clinton, a lawyer whom one would hope had actually read and understood the Supreme Court ruling, contributed this dire warning to the debate: “It’s very troubling that a salesclerk at Hobby Lobby who needs contraception, which is pretty expensive, is not going to get that service through her employer’s health-care plan because her employer doesn’t think she should be using contraception.” Even the Washington Post, recognizing the unbelievable misfire on the topic, gave Clinton “two pinocchios” for this comment, stating that “Clinton was leaping to an assumption about the impact on employees.”

A Slate article, adding to the sensational rhetoric, resorted to an ominous tone: “The Supreme Court term wrapped up nice and neat last week. Unless you are a woman.” The decision, the author claimed, still has women reeling over its implications. Reeling? Really? Because a few very select bosses in the country aren’t required to pay for your abortifacients?

One often hears about the “fog of war” that comes about in battles, in which the truth is difficult to discern, only clarified later by time and distance. Somehow, however, the fog around the so-called “war on women” seems to be self-imposed and self-perpetuating.

Ours is an age of tyrannical feminists. Using shrill voices, dialed up to the highest pitch possible, these women warn of impending catastrophe from anything that might not align with their current allegiances, while actively drowning out dissent.

July 13, 2014

"Renewing the West by Renewing Common Sense" Conference, July 17-20th

HEAR YE! HEAR YE!

Announcing a “Call for Papers and Plenary Session Panelists” for an international congress to

discuss the revolutionary proposal:

RENEWING THE WEST BY RENEWING COMMON SENSE

LOCATION: Seminary of the Immaculate Conception

440 West Neck Road

Huntington, Long Island, NY 11743

DATES: THURSDAY AFTERNOON 17 JULY 2014 to

SUNDAY MORNING 20 JULY 2014

CHIEF TOPICS OF DISCUSSION:

A Common Sense Understanding of Ethics

A Common Sense Understanding of Politics

A Common Sense Understanding of Philosophy, Science, and the Art

A Common Sense Understanding of Religion and Theology

ALSO ANNOUNCING FORMATION OF The Thomistic Leadership Circle

and

The Aquinas School of Leadership, Management, and

Organizational Development

CO-SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS

• Adler-Aquinas Institute

• Aquinas School of Leadership, Management, and Organizational Development

• Caritas Consulting

• Catholic Education Foundation

• Catholic Education Online/MOOC

• Center for the Study of the Great Ideas

• Holy Apostles College and Seminary

• International Étienne Gilson Society

• Studia Gilsoniana, a Journal in Classical

Philosophy

People interested in presenting a paper or being a plenary session panelist should contact conference organizer, Dr. Peter A. Redpath, ASAP, at: redpathp@gmail.com

NOTE: This meeting will focus on discussion, not lecture. We intend it as a working conference in which all participants will be as actively involved as possible. Hence, we will try to have as many participants as possible as plenary session panelists.

Total cost for overnight accommodations for 3 nights, plus 9 meals, conference participation, coffee breaks, cocktail reception, and registration: $325.00. The cost is a package deal (whether a person stays 1, 2, or 3 nights). Early arrivals on Wednesday evening permitted at a nominal additional cost (to be determined by the Seminary).

Presently, the Seminary has 30 air-conditioned rooms available for overnight accommodations. They have many other rooms presently available, but only 30 are air conditioned. Those wanting those rooms should register now and reserve them ASAP.

Registration to start after 12:30 pm lunch on Thursday, 17 July 2014.

Go to the Adler-Aquinas Institute website for further information

July 12, 2014

The parables of Christ are not secret codes but calls to conversion

"The Sower (Sower with Setting Sun)" (1888) by Vincent van Gogh (www.wikiart.org)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, July 13, 2014 | Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Isa 55:10-11

• Psa 65:10, 11, 12-13, 14

• Rom 8:18-23

• Mt 13:1-23

The well-known parable of the seed and the sower is the first of seven parables in Matthew 13. These are known as the “Sermon of Parables” (Mt 13:1-53), and this sermon, as a whole, is the third great sermon recorded in the first Gospel, the previous two being the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5-7) and the Mission Sermon (Mt 10:5-42).

There are about forty parables in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke (the Fourth Gospel contains no parables), and each expresses some truth about the mystery of the Kingdom of God, which is the heart of Jesus’ preaching. They impart, Jesus told the disciples, “the secrets of the kingdom of heaven”, and are meant to enlighten those who hear with faith, while frustrating those without faith, “because they look but do not see and hear but do not listen or understand”.

Yet the parables are not secret codes for a certain select, but are challenging calls to conversion. Parables, explains Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, “are means used by God’s mercy to reach the obtuse and hard-hearted, to give them something they can grasp that will perhaps initiate in them a process of conversion.” They reveal by concealing, and in doing so they test our humility and our willingness to really hear and know the Word of God.

The first four parables in Matthew 13 (vs. 1-43) focus on how the kingdom grows and the transforming power of God’s Word that brings about such supernatural growth. The final three parables (vs. 44-50), are concerned with the complete and radical choice demanded by the reality of the kingdom, which requires a full commitment of the heart, soul, and mind.

Today’s reading from the prophet Isaiah describes how the goodness of God is evident in the rain and snow that waters the earth, thus providing the means of natural life—seed and bread—for everyone. Likewise, the word of God goes forth to all men and it “shall not return to me void”. So the word of God is likened to a seed; similarly, Jesus made a direct connection between the seed and the “word of the kingdom”. The seed that is sowed is not just a collection of words about the kingdom, but is the Word sent by the Father to dwell among men. This is, of course, the Incarnation, the coming the Logos, or Word, into the world (cf. Jn 1:9-18).

This seed is also the entire body of the teachings of the Incarnate Word, as well as the “good news” of his saving death and resurrection, by which the Kingdom is established and revealed. “In the word, in the works, and in the presence of Christ, this kingdom was clearly open to the view of men”, states the Second Vatican Council’s dogmatic constitution on the Church, “The Word of the Lord is compared to a seed which is sown in a field; those who hear the Word with faith and become part of the little flock of Christ, have received the Kingdom itself. Then, by its own power the seed sprouts and grows until harvest time”.

The constitution further notes, “While it slowly grows, the Church strains toward the completed Kingdom and, with all its strength, hopes and desires to be united in glory with its King” (par 5).

This parable of the seed and sower describes the slow growth and the straining of the Church here on earth. The path is the world, which is fallen and fractured, containing every sort of distraction and temptation. It contains much rocky ground and many thorns. Creation, as St. Paul observed, “is made subject to futility”, desiring to “be set free from slavery to corruption”.

But the world is also a place of authentic choice and of new life for those who are receptive to the seed. Those who truly hear, Jesus said, will be healed; they are, in the words of St. Paul, partakers in the “glorious freedom of the children of God”.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the July 10, 2011, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

July 11, 2014

Skeptics and the Claims of the Catholic Church

(CNS file photo)

by Thomas M. Doran | CWR blog

Seventeen reasons scoffers ought to rethink Catholicism, if they really thought about it

In today’s world, isn’t it crazy to appeal to scoffers to consider Catholicism? Why would a rational modern man or woman in the 21st century be attracted to what the world and its enlightened guides consider an outdated, misogynistic, anti-LGBT, anti-science cult?

Is historical momentum on the side of these scoffers? Doesn't history itself demonstrate the allegedly backwards and inhuman nature of the Catholic Church? The modern soothsayers say yes, but here are 17 reasons—hardly an exhaustive list—why the soothsayers are wrong:

1. The Church “conceived” the university, the hospital, and countless institutions to assist the world’s suffering.

2. Catholic martyrs—unlike Muslim “martyrs”—never kill, but offer their own lives as a sign of their love of God and their fellow man.

3. The Church, in obedience to its founder, conceived the concepts of universal justice, mercy, and generosity that became the moral foundation of the world’s representative democracies. Prior to this, and in much of the world today, only certain groups or classes are entitled to human and legal rights.

The World and the Church

Pope Paul VI presides over a meeting of the Second Vatican Council in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican in 1963. (CNS photo/Catholic Press Photo)

The World and the Church | James Kalb | Catholic World Report

We are all, faithful Catholics and secular humanists alike, members of the faith-based as well as the reality-based community

In his speech closing the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI noted that “the trend of modern culture” is “centered on humanity, … the modern mind” is “accustomed to assess everything in terms of usefulness,” “the fundamental act of the human person … tends to pronounce in favor of his own absolute autonomy, … [and] “secularism seems the legitimate consequence of modern thought and the highest wisdom in the temporal ordering of society.”

The Council proposed to deal with that situation, according to the Holy Father, by working with it as much as possible in hopes of eventually getting beyond it. In its deliberations, therefore, “the modern world’s values were not only respected but honored,” so much so that the Church “felt the need … almost to run after [the society in which she lives] in its rapid and continuous change.” The outcome of the discussions was “a simple, new and solemn teaching to love man in order to love God … to love man … not as a means but as the first step toward the final and transcendent goal which is the basis and cause of every love.”

So the ultimate goal did not change: “the effort to look on [God], and to center our heart in Him which we call contemplation, is the highest, the most perfect act of the spirit, the act which even today can and must be at the apex of all human activity.” Nonetheless, the Holy Father seemed to say, the Church must meet and value people where they are, and lead them to God by developing the implications of what they already know, want, and do. Just as all roads lead to Rome, one might say, all human interests and efforts, pursued honestly, consistently, and fully, should lead to God.

Such was the hope, a hope that indeed has much to be said for it. Nonetheless, the process turned out more difficult than expected.

"Citadel of God: A Novel About Saint Benedict" (Chapter One)

Citadel of God: A Novel About Saint Benedict (Chapter One) | Louis de Wohl

"Rome is finished", said Senator Albinus. He sipped his wine, then held up the goblet carved from amethyst. "Very pretty", he approved. "I wonder where they find stones large enough to be cut like this. Very pretty."

Senator Boethius frowned. 'They come from India, I believe", he said, with a warning glance towards his wife.

Senator Boethius frowned. 'They come from India, I believe", he said, with a warning glance towards his wife.

But Rusticiana was beyond taking notice. Her face was drained of blood, and her hands twitched. "Rome is indeed finished", she said breathlessly, "if there are no Romans left. And I see there aren't."

The boy Peter gazed at her with rapt admiration. She was as beautiful as a goddess when she was angry. She was a white flame burning.

"Romans", Senator Albinus drawled. "I wouldn't say there aren't any, Domina Rusticiana, but they are few, you know. The city prefect tells me he had great difficulty in getting the men together for the escort of honor."

"The escort of honor for a barbarian tyrant", Rusticiana said icily. "Indeed, I hope it was difficult. It is bad enough that anyone at all would comply."

"Oh, it wasn't for that reason, I'm afraid", Albinus said dryly. "They didn't want to wear armor all day. So heavy, don! 't you see, and standing on the walls and in the streets in it for hours on end. The city prefect had to grant them three sesterces for special duty. They asked for five, at first." He smiled at Rustician's disgust. "The trouble with you, Domina, is that you were born five centuries too late. On second thought, make it a thousand years. You ought to have been a contemporary of Cloelia, Virginia, and Lucretia."

"I wish I could return the compliment", Rusticiana. snapped.

"Don't you see that he talks like that only because he, too, is suffering?" Boethius asked with gentle reproach.

"Talking seems to be all that is done', she said. "If there were one true Roman left, he would act."

"What would you have him do, Domina?" Albinus asked, mockery in his tone, but not in his eyes. "Have a nice, hot bath and open his veins? Old Scaurus did that, last week, when he heard that the King was coming to Rome."

"He was eighty", Rusticiana said, her eyes blazing. "And at that age the only veins a man can open are his own. But at least he did do that."

Albinus looked at Boethius. "Do you know, I begin to believe your wife wants me to go and kill the King." He laughed. "As her husband, I trust she has given you first chance."

"A thousand years ago," Rusticiana said, "at the time of Lucretia, we threw out our own King, and not even the maddest of the Caesars dared to assume that title again. Now we are to give it to an Ostrogoth."

'Just as I thought." Albinus gave a nod. "No denial. No contradiction. I wonder what you told her when she suggested it. But whatever it was, it doesn't seem to have been very convincing. Very well, I'll have a try." He turned to Rusticiana, the mask of amused banter gone. The clever little face with its small, almost womanish mouth was tense. "What do you think would happen in such a case?" he asked softly. "Not that I could succeed–there are clusters of his brawny giants around him all the time, and they'd cut me down as soon as they saw a sword or dagger in my hand. But let's assume I succeed before they cut me down. What would happen? First, they'd massacre everybody in sight. I am a senator, so is your husband and so, of course, is your noble father. They'd kill every member of the Senate, Domina, and they would not choose an easy death. Nothing would convince them that this wasn't a conspiracy, and they'd torture all of us to get the names of other conspirators. King Theodoric isn't coming here alone, you know. He'll have a small army with him, and his men don't mind wearing armor. They would have to elect a new king, naturally.

Theodoric has no son, only a daughter, and she is little more than a child. They'd choose a soldier-king. Young Tuluin, perhaps, or his cousin Ibba or someone of that kind. Theodoric is a barbarian, but at least he has some respect for our culture and civilization; and hes practically the only one who has. His successor's first great action would be to avenge Theodoric's death. There is no Roman army on whom he could avenge it, so he'd have to find a scapegoat. There is only one: Rome itself. He'd burn it down, destroy it. No one could stop him. Do you want this to happen, Domina? You would lose your husband, your father, your friends, your wealth, and your home, and Rome would be in ashes. And Italy would still be ruled by the Ostrogoths, under a king worse than Theodoric. You'd gain nothing."

"I?" Rusticiana asked. "You don't think I would survive my husband's death, do you? But we would all die as free Romans. And history would record it."

"History would do no such thing", Albinus returned to his easy, almost playful tone. "And that for the simple reason that there'd be no one left to write it down, except perhaps Cassiodor. The King has made him his private secretary, I'm told."

"Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus", Rusticiana said bitterly. "A man of his family and upbringing, the secretary of Theodoric. Freedom has no meaning any longer, it seems."

"Nothing has any meaning when you're dead", Albinus said, with a shrug. "Forgive me, Rusticiana–you and your husband are known to be good Christians and therefore you believe in a good many things. They baptized me too, but ... well, never mind. As for Cassiodor, he wouldn't survive the King's death either, I'm afraid. But no historian worthy of the name could possibly record that Rome was burned because the Romans rose against the tyrant and fought for their freedom. It wouldn't be true. It may be extremely regrettable, but on the whole they are not opposed to Theodoric's regime at all."

"Albinus!"

"I'm afraid he's right, Rusticiana", Boethius said sadly.

"You're living in a dream world, Domina", Albinus went on. "You seem to forget that the man has been the ruler of Italy for seven years. True, this is the first time he's come to Rome. But what of it? He's been ruling Rome from Ravenna, just as some of our own emperors did in the past. This is no more than a visit, a ceremonial visit, of course, with everyone present in his best clothes to greet the great royal illiterate."

"He can't write? He's as crude as that!"

"He does quite well,. nevertheless. He's not a stupid ox as so many of them are. He likes erudite people, I'm told. He's an organizer, too; and for a German he's remarkably mild."

"True", Boethius agreed quietly.

"His laws are not without a kind of down-to-earth wisdom", Albinus continued. "He's shrewd. Twice within the last five years he has lowered the taxes. And those of my colleagues in the Senate who visited him in Ravenna, say that he has great dignity and even that he is a great ruler in his own barbarous way."

"He bought them, no doubt", Rusticiana said contemptuously. "Not all senators are as wealthy as you are, Albinus. And if it weren't for that and for the fact that you are an old friend of my husband's, I would be tempted to ask what he has done for you that you defend him so eagerly."

"Rusticiana," Boethius said severely, "you forget yourself. Do not pay any attention to this, Albinus, I beg of you. My wife is very young and very much upset by this ... royal visit."

"I'm not offended." Albinus smiled. "In fact, I admire your wife's spirit. And there is no harm in saying what one feels ... here, in the great house of the Anicians. Elsewhere, of course, it might be a little dangerous. The Anician family knows how to choose its slaves, too. Besides, we're among ourselves, in this room, the three of us–the four of us, I mean", he corrected himself, still smiling. "I almost forgot our young friend here. But you won't give us away, Peter, I know that."

"I'm a Roman", the boy Peter said, staring at Rusticiana.

"Exactly", Albinus said.

"Peter had a Roman father and a Greek mother", Boethius explained. "She was a great and gracious lady. We are happy to have him with us."

"I well believe that." Albinus gave the boy a friendly nod. Intelligent little face, he thought. He wondered for a moment whether Boethius might be the boy's father and dismissed the thought. Boethius was a paragon of virtue. Besides, Domina Rusticiana was not the kind of woman who would consent to have her husband's natural son under her roof. The boy adored her, obviously. "How old is he?"

"Thirteen", Peter said quickly.

"He will be thirteen next month", Boethius corrected. "His birthday is almost the same as my wife's. We celebrate them together."

"You make me sound like a child, too", Rusticiana said reproachfully. "I shall be eighteen."

"As old as that, are you, Domina?" Albinus asked gravely. "Then there will be silver in your lovely hair in only forty years' time."

She could not help smiling. "I'm glad you are not offended, Albinus. My husband often tells me that I'm hasty and too impulsive. But I do feel strongly–"

She was interrupted by the chant of a beautiful voice, coming from somewhere high up. "The ninth ... hour."

"As late as that", Albinus said. "We must go, friend. The Senate is assembling."

"The ... ninth ... hour", sang the slave at the sundial on the roof.

"The King hasn't come yet", Boethius said. "I have posted slaves at the gates where he is most likely to arrive. None of them has come back so far."

"The ... ninth ... hour", came the third call.

"Even so I think we'd better go", Albinus said. "They'll be on horseback and they love galloping through the streets. Once they're within the city gates all the streets to the Forum will be blocked."

Rusticiana gritted her teeth. "Rome has been invaded by barbarians before", she said. "There was Brennus and Alaric and Genseric of the Vandals. But what I cannot bear is that instead of resisting we open our gates to this brute, this great, organizing, tax-reducing brute; that the greatest assembly on earth, the Roman Senate, consents to receive a barbarian as their lawful ruler. We no longer feel the shame of slavery. We're content to lick the boots of a Goth."

"They won't taste very different from those of Nero and Domitian", Albinus replied bitterly. "We have become accustomed to slavery. That's why I said Rome is finished, Domina. The spirit of a few of us won't help. Only if a couple of hundred thousand Romans would share it and act accordingly ... by all the gods and saints, you'll have me daydreaming too, if I listen to you long enough. Boethius, we must go."

"My litter is waiting beside yours in the courtyard." Boethius embraced his wife. 'Don't take it so hard", he said gently. "It's only a formality. I shall be back for the night meal. The official banquet is not until tomorrow." But she was stiff and unyielding in his arms, and her bow to Albinus was cool.

When the men had left, she sank down on the couch and buried her face in her hands. "Rome is finished", she said. "Finished. Finished."

"I'm a Roman!', the boy Peter said fiercely.

Perhaps Albinus was suffering, too, as Boethius seemed to think, but what if he were? As a Christian one could offer up one's own suffering to Christ–Deacon Varro always said that. But could one offer up the shame of one's country?

And to think of the finest mind and the greatest person in the world, of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, bowing and scraping to a barbarian chieftain and a heretic to boot ... it was too much.

She burst into tears. But almost at once she remembered that she was not alone in the room, the boy was there, it was not seemly that she should let herself go like this before his eyes. He had said something, a little while ago, what was it?

She wiped her eyes. "What was it you were saying, Peter?"

There was no answer. She looked up. The boy had gone.

Louis de Wohl (1903-1961) was a distinguished and internationally respected Catholic writer whose books on Catholic saints were bestsellers worldwide. He wrote over fifty books; sixteen of those books were made into films. Pope John XXIII conferred on him the title of Knight Commander of the Order of St. Gregory the Great.

• Read de Wohl's thoughts about being a Catholic and a novelist.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers