Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 84

August 11, 2014

The Drama of Faith: Priestly Sub-Creation

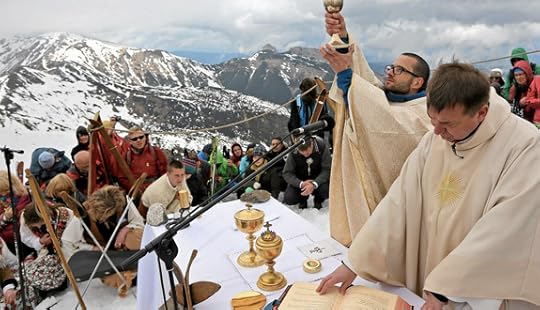

A priest raises the chalice as he celebrates Mass in honor of Sts. John Paul II and John XXIII in the ski resort Kasprowy Wierch in Poland's Tatra Mountains April 27, 2014. (CNS photo/Agencj a Gazeta/Marek Podmokly, Reuters)

The Drama of Faith: Priestly Sub-Creation | Mark P. Shea | Catholic World Report

The gamble that God took in becoming human was the willingness to risk that we would approach creation sacramentally

Both liturgy and drama are stylized representations of reality that mediate to us an encounter with the human and the divine. That’s because human beings are born to be priests. A priest is nothing more or other than a go-between, mediating man to God and God to man. We must live out our priestly role. It is our nature, since we were made by God to do it and continue to do it, in some form or another, even after the Fall. Therefore, we do it both through art and religion—as well as in every other sphere.

So when a man becomes a father, he mediates the image of God the Father to his children, whether he will or no. That’s why Paul tells us that the Father (Pater) is the one from whom all fatherhood (patria) is named (Ephesians 3:14). A father is an image of the Father. He may be a very debased image, but the mediation happens nonetheless. Likewise, teachers, bosses, authority figures, politicians, baseball players, scientists in lab coats, rock stars and so forth are all “looked up to”. Why do we “look up”? Because they are “on a pedestal”: you know, where the statue of Zeus used to be. We crave a priesthood that will mediate ultimate reality to us and tell us who we are—and who we might be. Not for nothing is the show called “American Idol”.

This conflation of the arts with revelation is nothing new.

August 10, 2014

St. Peter Walks on Water: Rebuke, Revelation, and Redemption

"St. Peter Invited to Walk on the Water" (1766) by Francois Boucher (WikiArt.org)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, August 10, 2014 | Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• 1 Kgs 19:9a, 11-13a

• Ps 85:9, 10, 11-12, 13-14

• Rom. 9:1-5

• Mt 14:22-23

Recently, I led a Bible study through the Book of Proverbs. It is, of course, filled with many challenging sayings, some of which are too easily passed over before their depth and insight can be fully appreciated.

One such proverb comes to mind in reading today’s Gospel: “Better is an open rebuke than a love that remains hidden” (Prov 27:5). Such a statement runs counter to the dominant culture of our day, which insists, first, that any and all “love”—whether really loving or not—declare itself from the rooftops (or one’s Facebook page) and, second, that rebuke comes from those who unloving, rigid, and needlessly judgmental. But this proverb indicates that real love sometimes compels a necessary rebuke.

How so? The answer can be found in the famous story of Peter walking on water and then sinking in dramatic fashion. In fact, a connection can be seen between three essentials: rebuke, revelation, and redemption. A proper rebuke, or reprimand, is never an end in itself. And when it comes from God, it is a grace meant for our growth in understanding and the attainment of salvation.

It appears that Jesus wished to test the faith of the apostles, for he “made the disciples get into a boat” to go to the other side of the lake while he spent time alone in prayer. Surely he knew the storm was coming; surely he knew the distressed state of the disciples. The boat was being “tossed”—or, more literally, “harassed” and “tortured” by the winds and rain. Darkness and chaos reigned, as they seemingly did before God separated light from darkness in the very beginning (cf. Gen 1:2). The fourth watch of the night was between three and six in the morning, so the disciples had been caught in the storm for several hours when Jesus came toward them. Exhausted and unnerved, they were further terrified at the sight of Christ, thinking he was a ghost.

“Take courage, it is I; do not be afraid.” The phrase “it is I” (ego eimi) can also be translated as “I AM”; it is an implicit declaration of divinity, harkening back to Yahweh’s revelation to Moses in the burning bush (Ex 3:14). Peter, the leader of the group, asked for the Lord’s command to come to him. Whereas Yahweh had told Moses, “Come no nearer!” (Ex 3:5), Jesus responded to Peter’s request by simply saying, “Come.” Moses needed to see and know the power of God who is completely Other and Holy. Peter, who already believed in God, needed to see and know the power of Jesus who is completely divine and human, approachable because he is the unique God-man.

Peter, ever impulsive and filled with faith, stepped out of the boat and began walking toward Jesus. It’s easy to fixate on Peter’s moment of fear and to overlook that Peter did actually walk on water and that he did so because of his faith. After all, as Peter faltered, Jesus did not grab his hand and say, “O you of no faith!” As St. Jerome wrote of this story: “Peter is found to be of ardent faith at all times. … he believes he can do by the will of the Master what the latter could do by nature.”

But Peter’s faith was still lacking. He needed to be rebuked so he could be see more clearly and be redeemed more completely. Two other occasions come to mind. Having declared Jesus to be the Messiah, Peter (wrongly!) rebuked his Master for prophetically announcing his approaching Passion; he was then rebuked soundly by Jesus: “Get behind me, Satan!” (Matt 16:16-23). And even before he denied Jesus three times, Peter was rebuked for his hubristic declarations of courage (Matt 26:33-35, 75).

The revelation in each instance was the same: the true nature and power of the King and his Kingdom. Loved perfectly, Peter was rebuked openly so he could walk without fear and witness without faltering.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the August 7, 2011, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

August 8, 2014

The Holy Inquisition: Dominic and the Dominicans

The Holy Inquisition: Dominic and the Dominicans | Guy Bedouelle, O.P. | From Saint Dominic: The Grace of the Word (Ignatius, 1987, 1995)

In his History of France, so characteristic of the nineteenth century, Jules Michelet has painted a fresco in which he shows the Church of the thirteenth century in Languedoc checking "the spirit of free thought" that represented heresy. The sentences pour out, nervous, breathless, romantic . . . and inexact. "This Dominic", he writes, "this terrifying founder of the Inquisition, was a Castilian noble. No one surpassed him in the gift of tears, a thing so often joined to fanaticism." [1] And in the following chapter he continues: "The Pope could only vanquish independent mysticism by himself opening great schools of mysticism: I refer to the mendicant orders. This was fighting evil with evil; attempting that most difficult of contradictions, the regulation of inspiration, the determination of illuminism . . . delirium unleashed!"

Pedro Berruguete's (d. 1504) tableau, the Scene of Auto da fé in the Prado museum in Madrid, is equally well known. St. Dominic, recognizable by his mantle ornamented with stars, is seated on a throne presiding over a tribunal and surrounded by six magistrates, almost all of them laymen. Below, to the right, are heretics roped to stakes soon to be set ablaze. The contrast is striking and the composition noteworthy. The tableau was doubtless intended for the glory of Dominic: the same painter designed several altar pieces for the Dominican convent in Avila at the request of Thomas of Torquemada (d. 1493), Inquisitor General in Spain in 1483.

If we go back a little further in history we shall find Dominican witnesses to show how Dominic took part in the first Inquisition against the Catharists and Vaudois in Languedoc. A reference made by Bernard Gui (1261-1331) in aLife of St. Dominic does not hesitate to claim for his Founder the title of First Inquisitor, following the "legendary" texts of the thirteenth century. [2] Nor has the author of the celebrated "Manual for Inquisitors" hesitated to interpolate on his own authority the Albigensian History of Pierre des Vaux de Cernai in order to prove Dominic's presence at the Battle of Muret during the bloody Albigensian Crusade on September 12, 1213: the Saint is pictured holding in his hands a crucifix riddled with wounds, which is still shown at St. Sernin in Toulouse. [3]

Lacordaire, on the contrary, at the moment when he was pleading before his "country" the cause of the reestablishment of the Order of Preachers in France in 1838, that is to say, a few years after the impassioned words of Michelet about the foundation of the mendicant orders, affirmed boldly (chap. 6) that "St. Dominic was not the inventor of the Inquisition, and never performed the duties of an inquisitor. The Dominicans were never the promoters or principal agents of the Inquisition." The historical demonstration following these claims must unfortunately be viewed with some reserve. It was - and not only on the basis of historical accuracy - vehemently attacked, in particular by his friend Dom Prosper Guéranger, the restorer of the Benedictines of Solesmes; he accused Lacordaire of not having the courage to "accept his heritage".

What, then, are we to believe? Was Dominic the first of the inquisitors? The answer is categorically: by no means! Simple chronology suffices to resolve the problem: Dominic died in 1221, and the office of Inquisitor was not established until 1231 in Lombardy and 1234 in Languedoc.

Were the Friars the principal agents of the Inquisition? Or did they simply take part in it "like everyone else", as Lacordaire says? This time the answer must be more nuanced. But we must know exactly what we are referring to when we use the word inquisition, so deadly in its ordinary connotation, before we can attempt to define its significance.

We must first realize that there were two inquisitions or, to put it better, two currents of inquisition, quite dissimilar in their origins and functions. The first, in the thirteenth century, was the result of a long process set in motion by the popes; it is often called "the pontifical inquisition". The second answered to an initiative of the Catholic kings of Spain who, in 1478, asked the pope to reorganize the former institution. This tool of royal absolutism - aimed at the religious minorities of Jews and Moslems, who were being assimilated with difficulty into the national life, and at the current trends of thought which seemed to be threatening the social order - would not be suppressed until the nineteenth century. This was the object of "the black legend", so tenacious that even today the term "inquisition" immediately arouses emotional reactions and evokes concepts of fanaticism and intolerance among the people. The kings of Spain often appealed to Dominicans like Thomas of Torquemada, but more often, from the end of the sixteenth century on, to Jesuits. [4]

When we speak of the Inquisition today we often confuse two entities which it would be greatly to our advantage to distinguish: a procedure and a tribunal. The Inquisitio is first of all a juridical procedure. It is the procedure of inquiry which, in modern nations, is officially opened by public authority when some crime is brought to its attention. It precedes the registering of a complaint or accusation, which in its turn will set in motion the handling of the civil offense. The introduction of this procedure is very objective and detailed: this is its guarantee for the accused. The method has come a long way in comparison with the ancient procedure of accusation, which was in early times very general in its character. This was the situation at the beginning of the thirteenth century in regard to heretics: they were prosecuted only after having been formally accused. Toward 1230 the process of inquiry was used in regard to matters of faith. The problem lay not in the process of inquiry itself, but in the fact that the royal and ecclesiastical authorities considered that a manifestation of dissent in matters of faith was a crime, subject to official prosecution.

The Inquisition was also a tribunal, an emergency tribunal destined to identify the crime for heresy, using among other procedures that of inquiry. This was the origin of the Office of Inquisition, entrusted to various persons. Without voiding the tribunal of the bishop which, up to that time, had dealt with matters of faith, this new tribunal largely substituted for it.

Heretofore, heresy had been handled as a spiritual matter by the bishop's tribunal, which was charged with assessing the belief of the baptized in a given diocese. The prince, who used secular constraint to obtain the accusation and punishment of those condemned for heresy, according to the normal functioning of his penal law, left to the bishop the final decision as to the validity of the accusation of heresy.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century Pope Innocent III's many moves against heretics, in sending legates to various parts of Christendom, served only to arouse and increase the bishops' action. There were vast campaigns of preaching, destined to bolster the belief of Catholics and to lead heretics back to the Faith. It was with one of these campaigns of the Word, being conducted in the Midi, that Dominic was associated (1206-1209).

The frequent inefficiency of the bishops' tribunals led Emperor Frederick II of Germany and Pope Gregory IX to move toward the creation of an emergency tribunal. Its judge would be a cleric, but the prince would vouch for its foundation and temporal effectiveness. He would determine the locales, maintenance, the carrying out of arrests, and appearances before the courts, as well as the penalties incurred according to his own penal laws. In 1231 a joint decision of Pope and Emperor led to the creation of the Office of the Inquisition, to be erected from that time on in Germany and Italy. This tribunal was introduced in northern France in 1233 and in the Midi at the beginning of 1234. It is clear, therefore, that it was not especially designed for the latter region as is commonly supposed. It had nothing to do with St. Dominic.

This office may be defined as an emergency tribunal set up on a permanent basis to deal with all matters involving the defense of the Faith, and using the inquisitorial procedure, which was far more flexible and effective. [5] It was not a "religious policy". It was a matter of convincing a heretic of the contradictory position he held in regard to the Christian Faith, and of converting him. The Inquisitor must therefore be a good preacher. For the least grave faults the tribunal imposed penalties of a religious nature: to carry a cross, to visit churches, to make pilgrimages - or more weighty undertakings. If the heretic was obdurate, the Church handed him over to the secular arm which could, from the thirteenth century on, decree the death penalty, forbidden however at the Third Lateran Council. From 1252 on, the Inquisition made use of the right to torture those charged with heresy, as was customary at the time in common law. We can see from this the importance of the role of the Inquisition.

The choice of the one who should be judge of the Faith was all the more serious in Pope Gregory IX's opinion, since he feared the danger of a judge too dependent on the prince, in whose service he could slight honesty in the performance of his duties. This was often the case with bishops, especially in Germany. The Pope therefore tended to choose religious, and sometimes secular priests. The first known Inquisitor, Conrad of Marburg, was a secular priest. Soon, however, the Pope turned to the Dominicans, particularly for France (1233) and Languedoc (1234). Two years later he added a Franciscan. In the ensuing years the Inquisitors of Languedoc were regularly Dominicans, those of Provence, Franciscans. These religious could devote themselves to instructing the people in the Faith with more continuity and greater depth than could monks or secular clergy, who were frequently drawn away to other tasks. But the Inquisition was never, as such, an office of the Order of Preachers.

The inquisitors were not responsible for the creation of the Inquisition. If some of them lost their sense of proportion due to the fearsome power given them, like the too celebrated Roger of Bougre, named in 1235, who dishonored his name by his excesses in northern France, most fulfilled the duties of judge entrusted to them with competence, freedom of spirit and a concern for the salvation of souls. They were convinced of the salutary need for this charge, as were most Christians in the West.

The problem of the Inquisition is rooted in two far older problems: that of the prosecution of heresy in Christian society and, more generally, that of the feelings of this society about disagreements within the body of the faithful.

The latter goes back to the origins of the Church, when Christians were intensely attached to "being of one mind" (Phil 2:2): "one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all" as St. Paul wrote (Eph 4:5). Faith was indeed entirely a gift of God; but to be authentic, it required belief and a common objective content.

It was Western society, ecclesiastical and political, which was responsible for creating and perfecting the Inquisition by a series of decisions on many levels. Western Christianity, welding the Church and temporal society together, believed it a just and holy thing to make Christian Faith and morals the basis for civil legislation and to place in its service the power of temporal coercion, of which the Inquisition was but one tool.

This sense of responsibility on the part of Europeans for the rule of Faith and for the salvation of their subjects, and their desire to intervene for its defense with the help of their bishops, remained very much alive in the West until the sixteenth century, even until the seventeenth. To rebel against the Faith was to rebel against the prince.

In their concern about salvation, so preponderant at the time, nations were often the first to insist on the prosecution of those who propagated teachings or methods of obtaining salvation that, in the judgment of the Church, risked the eternal loss of Christians. The man of the Middle Ages could understand tolerance of pagans who had no way of knowing revelation, but he was rigorous in dealing with Jews. This was to be the attitude of the papacy. It could regard deviations from the Catholic Faith and the repudiation of baptism only as grave sins. [6]

Dissension regarding the Faith thus appeared as the gravest of faults, by far the most pernicious. This is why the inquisitorial process sought first to cure, as a physician does. Not only the society that was threatened, but also the heretic himself, must be saved. This was the famous dilemma posed by Dostoyevsky in the striking scene of the Grand Inquisitor, depicted by him as an expression of Ivan Karamazov's revolt.

Throughout the Middle Ages this sort of temporal and spiritual collusion culminating in the Inquisition was considered normal. In none of the quarrels in which kings, emperors and rebellious clerics opposed the papacy - theologians like Marsile of Padua for example, so virulent and violent - do we find taunts about the Inquisition. Public opinion gave every evidence of approving, even desiring it. We must await the eve of the ideal of "tolerance", to find the challenging of at least the methods, if not the existence, of the institution. Erasmus, in this area as in others, seems to have been a precursor.

The Middle Ages were far more aware of social truths and values than of the sincerity of personal convictions. The deepening of the sense of the person and of liberty, though stressed by St. Paul as he considered Christian life to be ruled by grace (Gal 5:13) is a comparatively recent triumph. Our times cannot judge ages which thought otherwise. Our actual living out of this liberty is not, despite all the declarations of its intentions, favorable to the rights of man.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Vol. II, r. IV, chap. 7, Oeuvres complètes, vol. IV, critical edition, P. Viallaneix (Paris, 1974). In the first edition, Michelet wrote: "He was a noble Castilian, singularly charitable and pure. He was unsurpassed for his gift of tears and for the eloquence which drew tears from others." These last words were suppressed in 1852 and replaced by the vengeful sentence of 1861. "Examination of the revision of the text of 1833", op. cit., p. 657.

[2] For a statement of the question, see Vicaire, Dominique et ses Prêcheurs, pp. 36 57 ("Dominique et les Inquisiteurs", and also pp. 243 50).

[3] Cahiers de Fanjeaux, 16, pp. 243 5o (M. Prin and M. H. Vicaire).

[4] Guy Testas and Jean Testas, L'Inquisition (Paris, 1974).

[5] Cf "Le Credo, la morale et l'Inquisition", Cahiers de Fanjeaux 6 (1971), in particular the contributions of Yves Dossat. By the same author, Les crises de l'Inquisition toulousaine (1233 1273) (Bordeaux, 1959). See also Henri Maisonneuve, Etudes sur les origines de l'Inquisition, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1960); on Dominic and the early brethren, see pp. 248 49.

[6] For an exposition of the medieval attitude, see in the Summa Theologiaeof St. Thomas, Ila IIae, q. 10. It is here that the famous formula is found: "The acceptance of faith is a matter of free will, yet keeping it when once it has been received is a matter of obligation" (10, a 10 ad 3).

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Book Excerpts:

• St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers | Jordan Aumann, O.P.

• The Inquisitions of History: The Mythology and the Reality | Reverend Brian Van Hove, S.J.

• The Spanish Inquisition: Fact Versus Fiction | Marvin R. O'Connell

• The Crusades 101 | Jimmy Akin

• Were the Crusades Anti-Semitic? | Vince Ryan

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century | Josef Pieper

• Theologians and Saints | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

Guy Bedouelle, O.P. (b. 1940), is a French theologian, born in 1940 in Lisieux. He graduated from the Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris and has been the rector of the Catholic University of the West since 2008. He is the author of several books of Church history.

St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers

St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers | Jordan Aumann, O.P. | FromChristian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition | Ignatius Insight

Religious life continued to evolve in the thirteenth century as it had in the twelfth, and the evolution necessarily involved the retention of some traditional elements as well as the introduction of original creations. In fact, the variety of new forms of religious life reached such a point that the Lateran Council in 1215 and the Council of Lyons in 1274 prohibited the creation of new religious institutes henceforth.

Nevertheless, two new orders came into existence in the thirteenth century: the Franciscans and the Dominicans. As mendicant orders they both emphasized a strict observance of poverty; as apostolic orders, they were dedicated to the ministry of preaching. Yet there was a noticeable continuity between the newly founded mendicant orders and the older forms of monasticism and the life of the canons regular. At the risk of oversimplifying, we may say that the Franciscans adapted Benedictine monasticism to new needs while the Dominicans adapted the monastic observances of the Premonstratensians to the assiduous study of sacred truth, which characterized the Canons of St. Victor.

The mendicant orders, however, were not simply a development of monasticism; much more than that, they were a response to vital needs in the Church: the need to return to the Christian life of the Gospel (vita apostolica); the need to reform religious life, especially in the area of poverty; the need to extirpate the heresies of the time; the need to raise the level of the diocesan clergy; the need to preach the Gospel and administer the sacraments to the faithful. This was especially true of the Dominicans, who were consciously and explicitly designed to meet the needs of the times and to foster the "new" theology, Scholasticism. The Franciscans, as we shall see, were more in the tradition of the old monasticism and sought to return to a life of simplicity and poverty.

St Dominic Guzmán, born at Caleruega, Spain, in 1170 or 1171, was subprior of the Augustinian canons of the cathedral chapter at Osma. As a result of his travels with his bishop, Diego de Acevedo, he came face to face with the Albigensian heresy that was ravaging the Church in southern France. When they learned of the failure of the legates to make any progress in the conversion of the French heretics, Bishop Diego made a drastic recommendation. They should dismiss their retinue and, travelling on foot as mendicants, become itinerant preachers, as the apostles were.

In the autumn of 1206 Dominic founded the first cloister of Dominican nuns at Prouille; towards the end of 1207 Bishop Diego died at Osma, where he had returned to recruit more preachers. The work of preaching did not end with the death of Bishop Diego, but during the Albigensian Crusade under Simon Montfort, from 1209 to 1213, Dominic continued the work almost alone, with the approval of Pope Innocent III and the Council of Avignon (1209). By 1214 a group of associates had joined Dominic and in June, 1215, Bishop Fulk of Toulouse issued a document in which he declared: "We, Fulk, ... Institute Brother Dominic and his associates as preachers in our diocese . . . . They propose to travel on foot and to preach the word of the Gospel in evangelical poverty as religious." (56) The next step was to obtain the approval of the Holy See, and this was of special necessity in an age in which preaching was the prerogative of bishops. The opportunity presented itself when Dominic accompanied Bishop Fulk to Rome for the Lateran Council, which was convoked for November, 1215. According to Jordan of Saxony, Dominic desired confirmation on two points: the papal approval of an order dedicated to preaching and papal recognition of the revenues that had been granted to the community at Toulouse. (57)

Although Pope Innocent III was favorably inclined to the petition, he advised Dominic to return to Toulouse and consult with his companions regarding the adoption of a Rule. (58) Quite logically, the Rule chosen was that of St. Augustine, as Hinnebusch points out:

The adoption was dictated by the specific purpose St. Dominic sought to achieve -- the salvation of souls through preaching -- an eminently clerical function. The Rule of St. Augustine was best suited for this purpose. During the preceding century it had become par excellence the Rule of canons, clerical religious. In its emphasis on personal poverty and fraternal charity, in its reference to the common life lived by the Christians of the apostolic age, in its author, it was an apostolic Rule. Its prescriptions were general enough to allow great flexibility; it would not stand in the way of particular constitutions designed to achieve the special end of the Order. (59)

In addition to the Rule of St. Augustine, the early Dominicans used the customs of the Premonstratensians as a source for their monastic observances, for which reason they were often called canons as well as mendicant friars. What was peculiar to the Dominican Order was added by the first Chapter of 1216 and the General Chapter Of 1220: the salvation of souls through preaching as the primary end of the Order; the assiduous study of sacred truth to replace the monastic lectio divina and manual labor; great insistence on silence as an aid to study; brisk and succinct recitation of the choral office lest the study of sacred truth be impeded; the use of dispensations for reasons of study and the apostolate as well as illness; election of superiors by the community or province,; annual General Chapter of the entire Order; profession of obedience to the Master General; and strict personal and community poverty.

On December 22, 1216, the Order of Friars Preachers was confirmed by the papal bull, Religiosam vitam, signed by Pope Honorius III and eighteen cardinals. On January 21, 1217, the pope issued a second bull, Gratiarum omnium, in which he addressed Dominic and his companions as Friars Preachers and entrusted them with the mission of preaching. He called them "Christ's unconquered athletes, armed with the shield of faith and the helmet of salvation" and took them under his protection as his "special sons." (60)

From that time until his death in 1221, St. Dominic received numerous bulls from the Holy See, of which more than thirty have survived. The same theme is found in all of them: the Order of Preachers is approved and recommended by the Church for the ministry of preaching. St. Dominic himself left very little in writing, although we may presume that he carried on an extensive correspondence. The writings attributed to him are the Book of Customs, based on the Institutiones of the Premonstratensians; the Constitutions for the cloistered Dominican nuns of San Sisto in Rome; and a personal letter to the Dominican nuns at Madrid.

The Dominican friars were fully aware of the mission entrusted to them by Pope Honorius III. In the prologue of the primitive Constitutions we read that "the prelate shall have power to dispense the brethren in his priory when it shall seem expedient to him, especially in those things that are seen to impede study, preaching, or the good of souls, since it is known that our Order was especially founded from the beginning for preaching and the salvation of souls." (61)

"This text," says Hinnebusch, "is the keystone of the apostolic Order of Friars Preachers. The ultimate end of the Order, it states, is the salvation of souls; the specific end,. preaching; the indispensable means, study. The power of dispensation will facilitate the attainment of these high purposes. All this is new, almost radical." (62) On the other hand, it may be interpreted as a return to the authentic "vita apostolica," and that is the way St. Thomas Aquinas would see it: "The apostolic life consists in this, that having abandoned everything, they should go throughout the world announcing and preaching the Gospel, as is made clear in Matthew 10:7-10." (63)

Preachers of the Gospel need to be fortified by sound doctrine, and for that reason the first General Chapter of the Order specified that in every priory there should be a professor. Quite logically, the assiduous study of sacred truth, which replaced the manual labor and lectio divina of monasticism, would in time produce outstanding theologians and would also extend the concept of Dominican preaching to include teaching and writing.

Dominican life was also contemplative, not in the monastic tradition, but in the canonical manner of the Victorines; that is to say, its contemplative aspect was manifested especially in the assiduous study of sacred truth and in the liturgical worship of God. However, even the contemplative occupation of study was directly ordered to the salvation of souls through preaching and teaching, and the liturgy, in turn, was streamlined with a view to the study that prepared the friars for their apostolate. Thus, the primitive Constitutions stated:

Our study Ought to tend principally, ardently, and with the highest endeavor to the end that we might be useful to the souls of our neighbors. (64)

All the hours are to be said in church briefly and succinctly lest the brethren lose devotion and their study be in any way impeded. (65)

Because of the central role which the study of sacred truth plays in the Dominican life, the spirituality of the Friars Preachers is at once a doctrinal spirituality and an apostolic spirituality. (66) By the same token, the greatest contribution which the Dominicans have made to the Church through the centuries has been in the area of sacred doctrine, whether from the pulpit of the preacher, the platform of the teacher or the books of the writer. The assiduous study of sacred truth, so strictly enjoined on the friars by St. Dominic, provides the contemplative attitude from which the Friar Preacher gives to others the fruits of his contemplation. In this restricted sense we may say with Walgrave that the Dominican is a "contemplative apostle." (67)

ENDNOTES:

(56) Cf. Laurent, Monumenta historica S. Dominici, Paris, 1933, Vol. 15, p. 60.

(57) Jordan of Saxony, Libellus de principiis ordinis praedicatorum, ed. H. C. Scheeben in Monumenta O. P. Historica, Rome, 1935, pp. 1-88.

(58) The Fourth Lateran Council forbade the foundation of new religious institutes unless they were extensions of an existing institute or adopted an approved Rule.

(59) W. Hinnebusch, The History of the Dominican Order, New York, N.Y., 1965, Vol. 1, p. 44. The Rule of St. Augustine was also adopted by numerous other religious institutes founded in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

(60) Cf. W. Hinnebusch, op.cit., p. 49. On February 17, 1217, a third papal bull, Jus petentium, specified that a Dominican friar could not transfer to any but a stricter religious institute and approved the stability pledged to the Dominican Order rather than to a particular church or monastery.

(61) I Constitutiones S.O.P., prologue; cf. P. Mandonnet-M. H. Vicaire, S. Dominique: l'idee, l'homme et l'oeuvre, 2 vols., Paris, 1938.

(62) Cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 84.

(63) Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem.

(64) I Const. S.O.P., prologue; cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 84.

(65) I Const. S.O.P., n. 4; cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 351.

(66) Cf. M. S. Gillet, Encyclical Letter on Dominican Spirituality, Santa Sabina, Rome, 1945 Mandonnet-Vicaire, op. cit.; V. Walgrave, Dominican Self-Appraisal in the Light of the Council, Priory Press, Chicago, Ill., 1968; S. Tugwell, The Way of the Preacher, Templegate, Springfield, Ill., 1979; H. Clérissac, The Spirit of St. Dominic, London, 1939.

(67) V. Walgrave, op. cit., pp. 39-42.

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Book Excerpts:

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century | Josef Pieper

• Theologians and Saints | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

Jordan Aumann, O.P. (1916-2007), was a theologian and spiritual writer who authored Christian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition and Spiritual Theology.

Introducing Part 2 of "Symbolon: The Catholic Faith Explained"

August 7, 2014

Moral Feelings and the Moral World

(Left) Same-sex marriage supporters chant outside the Miami-Dade County courthouse July 2. (CNS photo/Zachary Fagenson, Reuters) (Right) Robert Stone from Springfield, Mo., and his daughter, Miracle, attend the March for Marriage rally in Washington March 26, 2013. (CNS photo/Matthew Barrick)

Moral Feelings and the Moral World | James Kalb | CWR

Progressives and traditionalists tend to approach moral decisions with differences in basic understandings of man, society, and the world.

A recent account of moral sentiments, proposed by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt in his book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion(Pantheon, 2012), has attracted attention for its explanation of the difference between progressives and traditionalists.

According to the account, moral judgments typically have to do with six dimensions of concern: care versus harm, fairness versus cheating, liberty versus oppression, loyalty versus betrayal, authority versus subversion, and sanctity versus degradation. Surveys show that progressives, by and large, are concerned with the care, fairness, and liberty dimensions, while traditionalists are concerned with all six. So it appears that the “culture wars” have to do with the moral status of loyalty, authority, and sanctity. Traditionally-minded people accept them as morally important, while their more progressive fellows do not.

But why the difference? It appears, although Haidt’s concerns lie elsewhere, that the difference lines up with the opposition between the modern tendency to view man as radically free and the world as technological, and the traditional, classical, and religious view of man as social, and the world as pervaded by intrinsic meanings, natural ways of functioning, and natural ends.

The difference is a difference in basic understandings of man, society, and the world.

August 6, 2014

“Ressourcement,” “Aggiornamento,” and Vatican II in Ecumenical Perspective

“Ressourcement,” “Aggiornamento,” and Vatican II in Ecumenical Perspective Eduardo Echeverria | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Some interpreters of Vatican II wrongly took renewal to be merely a matter of the Church’s adaptation or accommodation to the standards of the modern world

Ressourcement, Aggiornamento: Perhaps no two words were used more frequently by the Second Vatican Council to define the question regarding the nature and extent of the Church’s aim of renewal. What does each of these words mean and how do they stand in relation to each other? Ressourcement involves a “return to the authoritative sources” of Christian faith, for the purpose of rediscovering their truth and meaning in order to meet the critical challenges of our time. If ressourcement is about revitalization, renewal, then the oft-mentioned, but often misunderstood concept, aggiornamento is essentially a question of a new and wider contextualization, with the aim of finding new ways to rethink and reformulate the fundamental affirmations of the Christian faith in order to more effectively communicate the Gospel.

Ecumenical Context

Catholic theologians can learn something from Dutch Reformed theologian and master of dogmatic and ecumenical theology, G.C. Berkouwer (1903-1996), about how properly to interpret the relationship between ressourcement and aggiornamento. He wrote two books on Vatican II: The Second Vatican Council and the New Catholicism (ET: 1965) and Retrospective of the Council (1968). Berkouwer, then holder of the Chair in Dogmatics at the Free University of Amsterdam, was a personal guest of the Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, now the Pontifical Council, at the Second Vatican Council. Regarding the meaning of aggiornamento, Berkouwer rightly senses, “the questions involving ‘aggiornamento,’ renewal, are the ones that confront us big as life. As expected, after the call for accommodation was sounded, the question arose with increasing urgency of what the ideals of this ‘renewal’ could possibly mean concretely.” What, then, as Berkouwer understood it, are the goals of aggiornamento?

Unfortunately, some interpreters of Vatican II took renewal to be merely a matter of the Church’s adaptation or accommodation to the standards of the modern world—in short, “catching up” with the times. In other words, as Swiss biblical theologian, Oscar Cullman, rightly noted, they took aggiornamento as an “isolated motive for renewal.” When taken as such, aggiornamento means, on the accommodationist interpretation, simply adapting to the culture of modernity. The impulse for this misinterpretation indirectly derives, says Berkouwer, from Pope John XXIII’s understanding that the council’s “deepest intent did not lie in a sharp ‘anti’ but in a clear ‘pro’”—“God loves the world and calls the church to serve the world.” Of course, John XXIII did not share the accommodationist interpretation of his words that the primary stance of the Church to the world was not “apriori-antithetical.”

Rather, John XXIII states the primary aim of the council:

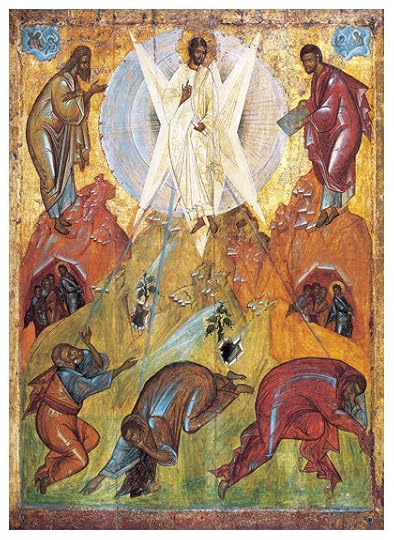

The Feast of the Transfiguration (and the 36th anniversary of Pope Paul VI's death)

The following is taken from an "Opening the Word" column I wrote for the February 28, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor:

In sum, in the days leading up the Transfiguration, Jesus had directly confronted and demolished any false notions the disciples might have had about the nature of his mission. He strongly expressed the unwavering commitment he had to offering himself as a sacrifice for the world. His kingdom was not of this world, and he was not a political leader or a military warrior; he was not promising comfort and wealth. On the contrary, Jesus was promising a cross: “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me” (Lk. 9:23).

We can only try to imagine how disorienting and confusing this had to be for the disciples. Suffering, rejection, and rapidly approaching death were not parts of their plan! In the midst of this confusion and anxiety, Jesus took Peter, John, and James, the inner circle of the disciples, up to the mountain to pray, ascending, as it were, toward the heavenly places. There, above the tumult of the world and an ominous future, Jesus revealed his glory and gave them a dazzling glimpse of their eternal calling.

But the glory witnessed by the three apostles was not just about the future. “The Transfiguration,” notes Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis in Fire of Mercy, Heart of the World (Ignatius Press, 2003), “is the experience of the fullness of divine Presence, action, communication, and glory now, in our very midst, in this world of passingness and disappointment.” It is about the fullness of life now—not ordinary, natural life, but extraordinary, supernatural life. The Transfiguration is about the gift of divine sonship, which comes from the Father, who says of Jesus, “This is my chosen Son; listen to him.”

St. Thomas Aquinas, in considering whether it was fitting that Jesus should be transfigured, observed that since Jesus exhorted his disciples to follow the path of His sufferings, it was right for them to see his glory, to taste for a moment such eternal splendor so they might persevere. He wrote, in the third part of the Summa, “The adoption of the sons of God is through a certain conformity of image to the natural Son of God. Now this takes place in two ways: first, by the grace of the wayfarer, which is imperfect conformity; secondly, by glory, which is perfect conformity…”

Peter and the disciples had to learn that Jesus’ death was necessary so his life could be fully revealed and given to the world. “On Tabor, light pours forth from him,” writes Leiva-Merikakis, “on Calvary it will be blood.”

Today also marks the 36th anniversary of the death of Pope Paul VI. Here is some of what Pope John Paul II said about Paul VI and this great feast day in 1999:

Today, the Eucharist which we are preparing to celebrate takes us in spirit to Mount Tabor together with the Apostles Peter, James and John, to admire in rapture the splendour of the transfigured Lord. In the event of the Transfiguration we contemplate the mysterious encounter between history, which is being built every day, and the blessed inheritance that awaits us in heaven in full union with Christ, the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End.

We, pilgrims on earth, are granted to rejoice in the company of the transfigured Lord when we immerse ourselves in the things of above through prayer and the celebration of the divine mysteries. But, like the disciples, we too must descend from Tabor into daily life where human events challenge our faith. On the mountain we saw; on the paths of life we are asked tirelessly to proclaim the Gospel which illuminates the steps of believers.

This deep spiritual conviction guided the whole ecclesial mission of my venerable Predecessor, the Servant of God Paul VI, who returned to the Father's house precisely on the Feast of the Transfiguration, 21 years ago now. In the reflection he had planned to give at the Angelus on that day, 6 August 1978, he said: 'The Transfiguration of the Lord, recalled by the liturgy of today's solemnity throws a dazzling light on our daily life, and makes us turn our mind to the immortal destiny which that fact foreshadows'.

Yes! Paul VI reminds us: we are made for eternity and eternity begins at this very moment, since the Lord is among us and lives with and in his Church.

From the Byzantine Divine Liturgy, here is the Troparion for the Feast of the Holy Transfiguration:

You were transfigured on the mountain, O Christ our God, revealing as much of Your glory to Your Disciples as they could behold. Through the prayers of the Mother of God, let Your everlasting light also shine upon us sinners. O Giver of Light, glory be to You.

And here is part of reflection on the Feast and the tropar, written by a Byzantine Catholic monk:

The union of Christ's humanity and divinity is complete and full, and as we meditate upon the feasts of the Lord's life we always benefit by focusing on this wonderfully unity in his person. Let us, as disciples might, bask in the brightness of this mystery, begging our Savior God to reveal Himself more fully to us. For what we see is beautiful and alluring. The tropar proclaims that Christ reveals His glory to his disciples. But the glory is not the divinity, nor is it the humanity, both are glorious in Him! Let the light shine upon us sinners (for the glory of humanity is marred in us by sin), that enlightened and purified through this feast, we too may shine through His generous gift of mercy.

The Anniversary of Hiroshima: John Paul II and Fulton Sheen on the Bomb and Conversion

The Anniversary of Hiroshima: John Paul II and Fulton Sheen on the Bomb and Conversion | Dr. R. Jared Staudt | CWR

Some reflections from two spiritual giants of the 20th century on the bombing of Hiroshima and the new, deadly era it ushered in

Today is the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. This is not simply an historical anniversary, but a continuing call to conversion. The reflections of St. John Paul II and Ven. Fulton Sheen will show how the use of atomic weapons is still a pressing moral issue, not only in terms of warfare, but in terms of broader cultural changes.

St. John Paul II on Hiroshima

St. John Paul II made the following remarks during his visit to Hiroshima on February 25, 1981:

Two cities will forever have their names linked together, two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as the only cities in the world that have had the ill fortune to be a reminder that man is capable of destruction beyond belief. Their names will forever stand out as the names of the only cities in our time that have been singled out as a warning to future generations that war can destroy human efforts to build a world of peace.

John Paul continued: “To remember Hiroshima is to abhor nuclear war.”

Going further, he stated to Japan’s ambassador to the Holy See on September 11, 1999: “The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are a message to all our contemporaries, inviting all the earth’s peoples to learn the lessons of history and to work for peace with ever greater determination. Indeed, they remind our contemporaries of all the crimes committed during the Second World War against civilian populations, crimes and acts of true genocide.”

Reflecting on the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, John Paul also spoke of

the haunting memory of the atomic explosions which struck first Hiroshima and then Nagasaki in August 1945. … Fifty years after that tragic conflict, which ended some months later also in the Pacific with the terrible events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and with the subsequent surrender of Japan, it appears ever more clearly as “a self-destruction of mankind” (Centessiumus Annus, 18). War is in fact, if we look at it clearly, as much a tragedy for the victors as for the vanquished.

John Paul makes clear that we have not yet dealt with all the effects of these bombs—bombs which have inflicted our country as well as Japan.

Ven. Fulton Sheen on the moral effects of the bomb

Ven. Fulton Sheen cuts right to the heart of these effects, ironically when talking to school students about sex.

August 5, 2014

Cardinal Mueller's book-long interview emphasizes indissolubility of marriage

Abp. Gerhard Ludwig Müller, now Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in 2010. (CNS file photo)

Cardinal Mueller's book-long interview emphasizes indissolubility of the marriage | CNA | Catholic World Report blog

"The Hope of the Family" (Ignatius Press) responds to mistakes in understanding the marriage in society

Vatican City, Aug 5, 2014 / 02:06 am (CNA/EWTN News).- In a book-length interview, Cardinal Gerhard Mueller has underscored that the indissolubility of the marriage is no mere doctrine, but a dogma of the Church, and stressed the need to recover the sacramental understanding of marriage and family.

Cardinal Mueller, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, granted the interview in June to the Spanish journalist Carlos Granados, director of the Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos in Madrid.

The book is titled “The Hope of the Family”, and will be released in English, Italian, and Spanish. It will be published shortly by Ignatius Press, and is priced at $10.95.

In the book, Cardinal Mueller corrects misunderstandings about the Church’s teaching on family; underscores the dramatic situation of the children of separated parents; and stresses that more education is needed, and that education should start from the reality of the love of God.

The book can be considered Cardinal Mueller's definitive contribution to preparations for the next synod of bishops, dedicated to the family, which will take place in Rome Oct. 5-19; he has chosen to give no further interviews for the time being.

The synod's theme will be “pastoral challenges to the family in the context of evangelization,” and numerous outlets have speculated about a possible change in Church teaching regarding the reception of Communion by those who are divorced and remarried, as well as a more lax discipline regarding annulment.

Despite such speculation, Cardinal Mueller underscored that “the total indissolubility of a valid marriage is not a mere doctrine, it is a divine and definitive dogma of the Church.”

Cardinal Mueller also addressed discussions on the possibility of allowing spouses to “start life over again,” and that the love between two persons may die.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers