Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 320

May 17, 2011

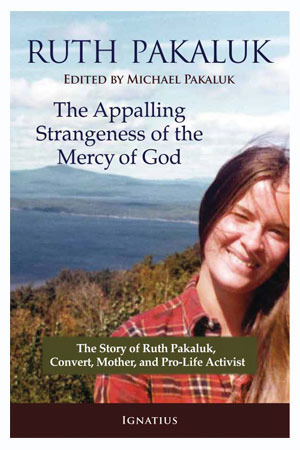

It was not just the arguments—"It was the witness"

Phil Lawler, who knew Ruth Pakaluk, reviews the recently published The Appalling Strangeness of the Mercy of God: The Story of Ruth Pakaluk: Covert, Mother, Pro-life Activist, edited by Michael Pakaluk:

Still, there are many effective pro-life activists. To appreciate the power of Ruth's influence, you had to know the woman. That's the purpose of this book: to offer readers an introduction to an amazing life. The decision to do so by collecting her letters was a wise one.

The first letters are light and chatty. She mentions, but does not dwell upon, her entry into the Catholic Church and her growing determination to fight for the dignity of human life. More often, the young Ruth tells correspondents about the weather, her domestic projects, the meals she has cooked and hikes she has taken: the quotidian life of a grad-student's wife. Yes, the correspondence is fluffy. But gradually the reader gains a sense of the personality behind these letters.

Then, as the months and the pages pass by, the letters take on a more serious tone. For this reader, the turning point in the book came with one letter in which Ruth lowered the boom on a young priest who had criticized her. She was not shy about confronting the clergy, and her own bishop felt the sting of her rebukes. (To his credit, Bishop Daniel Reilly hired Ruth as his diocesan pro-life coordinator despite their differences, and he joins in the chorus of praise with a back-cover blurb for this book.)

The relentless progress of cancer also give a more serious tone to the later pages of the book. Ruth talks candidly about her disease, her flagging strength, her worries for her husband and children. What's missing from the book is any sign that she worried about her own future; she expresses the calm confidence of a daughter of God, looking forward to coming home.

The Appalling Strangeness of the Mercy of God concludes with a series of Ruth's public talks. These are careful, logical presentations, delivered in a tone quite different from her breezy correspondence with friends. The arguments are solid, the rhetoric is persuasive. Yet by this point, at the end of the book, the reader should realize that it was not just the arguments that won over so many audiences. It was the witness.

Read the entire piece on CatholicCulture.org.

• I Invite You to Meet A Warrior for Life | Peter Kreeft | The Introduction to The Appalling Strangeness of the Mercy of God: The Story of Ruth Pakaluk: Covert, Mother, Pro-life Activist.

Cardinal Koch: Pope Benedict XVI in first step of a "reform of the reform"

From yesterday's Catholic News Service:

VATICAN CITY (CNS) -- Pope Benedict XVI's easing of restrictions on use of the 1962 Roman Missal, known as the Tridentine rite, is just the first step in a "reform of the reform" in liturgy, the Vatican's top ecumenist said.

The pope's long-term aim is not simply to allow the old and new rites to coexist, but to move toward a "common rite" that is shaped by the mutual enrichment of the two Mass forms, Cardinal Kurt Koch, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, said May 14.

In effect, the pope is launching a new liturgical reform movement, the cardinal said. Those who resist it, including "rigid" progressives, mistakenly view the Second Vatican Council as a rupture with the church's liturgical tradition, he said.

Cardinal Koch made the remarks at a Rome conference on "Summorum Pontificum," Pope Benedict's 2007 apostolic letter that offered wider latitude for use of the Tridentine rite. The cardinal's text was published the same day by L'Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper.

Cardinal Koch said Pope Benedict thinks the post-Vatican II liturgical changes have brought "many positive fruits" but also problems, including a focus on purely practical matters and a neglect of the paschal mystery in the Eucharistic celebration. The cardinal said it was legitimate to ask whether liturgical innovators had intentionally gone beyond the council's stated intentions.

The piece concludes:

On the final day of the conference, participants attended a Mass celebrated according to the Tridentine rite at the Altar of the Chair in St. Peter's Basilica. Cardinal Walter Brandmuller presided over the liturgy. It was the first time in several decades that the old rite was celebrated at the altar.

Damian Thompson of The Telegraph has video of Cardinal Brandmüller saying the Solemn Pontifical Mass at the altar of the Chair in St. Peter's Basilica, and the New Liturgical Movement site has a number of photos and more of the story. Cardinal Brandmüller is the author of Light and Shadows: Church History amid Faith, Fact and Legend (Ignatius, 2009; read Introduction on Ignatius Insight).

Related:

• Reform or Return? An Interview with Rev. Thomas M. Kocik, author of The Reform of the Reform? | Carl E. Olson

• Walking To Heaven Backward | Interview with Father Jonathan Robinson of the Oratory

• The Rotten Fruits of a Fashionable, Unserious Liturgist | Rev. Brian Van Hove, S.J.

• The Preface to The Old Mass and The New: Explaining the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum of Pope Benedict XVI | Bishop Marc Aillet

• Foreword to U.M. Lang's Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Reform of the Liturgy and the Position of the Celebrant at the Altar | Uwe Michael Lang | From Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer (2nd edition)

• The Altar and the Direction of Liturgical Prayer | Excerpt from The Spirit of the Liturgy | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• How Should We Worship? | Preface to The Organic Development of the Liturgy by Alcuin Reid, O.S.B. | by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Learning the Liturgy From the Saints | An Interview with Fr. Thomas Crean, O.P., author of The Mass and the Saints

• The Mass of Vatican II | Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.

• Does Christianity Need A Liturgy? | Martin Mosebach | From The Heresy of Formlessness: The Roman Liturgy and Its Enemy

• Music and Liturgy | Excerpt from The Spirit of the Liturgy | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Rite and Liturgy | Denis Crouan, STD

• The Liturgy Lived: The Divinization of Man | Jean Corbon, OP

• Reflections On Saying Mass (And Saying It Correctly) | Fr. James V. Schall, S. J.

What the Pope might say to Stephen Hawking if the two had a chat

The famous theoretical physicist Hawking was recently interviewed by The Guardian, and revealed that he does, in fact, believe in and worship a god—the name of which is "Science":

What is the value in knowing "Why are we here?"

The universe is governed by science. But science tells us that we can't solve the equations, directly in the abstract. We need to use the effective theory of Darwinian natural selection of those societies most likely to survive. We assign them higher value.

I'm not a physicist, and science was not my favorite subject in high school, but I do know that science (from the Latin, scientia, "having knowledge"), as defined by about any dictionary worth buying, is "an area of knowledge that is an object of study" and/or "knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through the scientific method" (Merriam Webster). So how is it that the study of general laws, which are obtained and tested through the "scientific method"—a human construct and enterprise, correct?—governs the universe? And, no, I'm not being entirely flippant, because while I know that this surely must not be what Hawkings is saying, it is what he is saying. Put another way, he renders science as some sort of abstact, objective giver of truth, and thus seeks to do away with the possibility of God as understood by Christians (as he attempted to do last year). More from the interview:

You've said there is no reason to invoke God to light the blue touchpaper. Is our existence all down to luck?

Science predicts that many different kinds of universe will be spontaneously created out of nothing. It is a matter of chance which we are in.

Was that an answer? Argument? Or simply the pronouncement of a prophet of the god, Science? Should we blithely accept that logic, reason, order, structure, study, and even science can exist—and be proclaimed trustworthy to boot—in a universe/cosmos that came into existence through random chance, has no extrinsic meaning or purpose, and "just is"? Hmmm. It sounds sketchy, at best.

Actually, it's completely unfair to speak ill here of science, because it's not science's fault (since science is an area of knowledge that utilizes a particular method of study, and is thus impersonal) that Hawking seems to be misusing or playing fast and loose with it. Hawking is, whether he knows it or not, following the lead taken by Comte, who claimed (again, in rather pontifical style), "Theology will necessarily vanish in the presence of physics". He is a disciple of scientism, which is a philosophical, pehaps even theological, system of belief. The Dutch philosopher William A. Luijpen, in Phenomenology and Atheism (Duquesne University Press, 1964), wrote of how the "closed realm of the physicist" often leads scientists to embrace atheism. And:

Having resolved to question the objects and phenomena of nature only from the standpoint of measurements, [the physicist] deliminates his field of presence in such a way that nothing that is not quantitative can ever arise in it. In other words, the realm in which the physicist is interested is fundamentally closed. This does not mean that his dialogue with the world is ever finished and complete, but it means that his realm is, as a matter of principle, delimited in such a way that, from the standpoint of the thematizing project of the physicist, nothing can ever come into view except the quantitative. If, nevertheless, the physicist introduces something else, he thereby abandons the questioning attitude that is characteristic of him. For instance, he can be impressed by the greatness of what he sees and call is beautiful, but he thus goes beyond his pursuit as a physicist. In physical science itself nothing is "great" or "beautiful." At the same time, however, it follows that on the basis of his physical science along he can never deny that something is great or beautiful. (pp. 62-3)

A bit later, Luijpen argues, "All this clearly indicates that the physicist, on the basis of his science, lacks competence to deny the existence of the Creator-God, which is affirmed by the believer. The fact that such a denial has been made by scientists in the past, and is made even today, reveals a frightful want of insight into the nature of knowledge." This statement is all the more interesting when read along with the following remarks from Hawking's interview:

So here we are. What should we do?

We should seek the greatest value of our action.

You had a health scare and spent time in hospital in 2009. What, if anything, do you fear about death?

I have lived with the prospect of an early death for the last 49 years. I'm not afraid of death, but I'm in no hurry to die. I have so much I want to do first. I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.

How, then, does science/physics inform us about "the greatest value of our action"? This is like watching actors testifying before Congress about farm bills or economics: everyone is very serious and there is much ponderous head-nodding, but does anyone really think that William Flowinghair, star of The Jaded Nightquest, should really be treated as an expert on the challenges of making a living on 5,000 acres of turnips in Iowa? Which is not to say that Hawking's knowledge or wisdom is necessarily limited to physics, or that he doesn't have a right to say anything at all about his beliefs regarding the Meaning of Everything. No, it is simply to note that when a physicist—even a theoretical physicist—moves into the realm of philosophical or theological musings, folks should keep in mind that he might not be on solid ground or expressing cogent ideas precisely because physics and science, properly speaking, don't tell us anything about "values" and the meaning of life.

Luijpen's remarks as similar to those found in a modestly-titled book, Introduction to Christianity (Ignatius Press, 2004; 2nd edition), originally published in 1968 by then-Fr. Joseph Ratzinger. In the chapter titled, "Faith in God Today", Ratzinger outlined an argument for God's existence based on intelligibility that is directly relevant to Hawking's remarks in particular, but also in general to the ongoing clash (supposed or real) between faith and science.

Ratzinger begins by noting that the statement, "I believe in God", is based on the presupposition that truth can actually be known, considered, and stated. "Christian faith in God means first the decision in favor of the primacy of the logos as against mere matter", he wrote. "In other words, faith means deciding for the view that thought and meaning do not just form a chance by-product of being; that, on the contrary, all being is a product of thought and, indeed, in its innermost structure is itself thought" (pp. 151, 152). Finite being as we experience it is marked by intelligibility, by a formal structure that makes it capable of being understood by the seeking, thinking mind. This recognition of the intelligible, knowable nature of things points to the rational position of belief in creation. It also is the basis for scientific research and thought, for scientists rely—implicitly or otherwise—on the belief that the material realm is intelligible and open to logical study, systematic observation, and ordered experimentation.

Ratzinger quotes Albert Einstein, who said that in the laws of nature "an intelligence so superior is revealed that in comparison all the significance of human thinking and human arrangements is a completely worthless reflection" (p. 153). But he also notes that Einstein was dismissive of belief in a personal God, which the great theoretical physicist dismissed as "anthropomorphic". This reveals, Ratzinger notes, the difficulty many have in believing that the "God of the philosophers" is also the "God of faith", one and the same. But Ratzinger insists that Einstein's view is too limited, too mathematically-focused, and misses the fact that in the world "we also find equally present in the world unparalleled and unexplained wonders of beauty, or, to be more accurate, there are events that appear to the apprehending mind of man in the form of beauty, so that he is bound to say that the mathematician responsible for these events has displayed an unparalleled degree of creative imagination" p. 155). The strange thing is that while physicists such as Hawking apparently think belief in God (and the afterlife) is somehow limiting (and based in some way on fear and superstition), they are the ones who limit themselves by embracing scientism rather than acknowledging the limitations of science proper.

Ratzinger argues that universal objective intelligibility leads to the conclusion of the existence of a great Intelligence, which has thought the world into being. He notes that there are a couple of false beliefs that can arise when it comes to a scientific study of "matter": 1) "Everything we encounter is in the last analysis stuff, matter; this is the only thing that always remains as demonstrable reality and, consequently, represents the real being of all that exists—the materialist solution", and 2) "all being is ultimately being-thought and can be traced back to mind as the original reality; this is the 'idealistic' solution." (p. 156). Rejecting both as unsatisfactory and limited, he goes on to say that "Christian belief in God means that things are the being-thought of a creative consciousness, of a creative freedom, and that the creative consciousness that bears up all things has released what has been thought into the the freedom of its, independent existence. ... the model from which creation must be understood is not the craftsman but the creative mind, creative thinking" (p. 157).

This point is clearly one that Ratzinger/Benedict XVI has dwelt upon over the decades, for in his 2011 Easter Vigil Homily, he again made similar observations, stating:

The central message of the creation account can be defined more precisely still. In the opening words of his Gospel, Saint John sums up the essential meaning of that account in this single statement: "In the beginning was the Word". In effect, the creation account that we listened to earlier is characterized by the regularly recurring phrase: "And God said ..." The world is a product of the Word, of the Logos, as Saint John expresses it, using a key term from the Greek language. "Logos" means "reason", "sense", "word". It is not reason pure and simple, but creative Reason, that speaks and communicates itself. It is Reason that both is and creates sense. The creation account tells us, then, that the world is a product of creative Reason. Hence it tells us that, far from there being an absence of reason and freedom at the origin of all things, the source of everything is creative Reason, love, and freedom. Here we are faced with the ultimate alternative that is at stake in the dispute between faith and unbelief: are irrationality, lack of freedom and pure chance the origin of everything, or are reason, freedom and love at the origin of being? Does the primacy belong to unreason or to reason? This is what everything hinges upon in the final analysis. As believers we answer, with the creation account and with Saint John, that in the beginning is reason. (April 23, 2011)

Hawking talks about the universe being "governed", but denies there is a governor/law-giver. He speaks of "values", but rejects the idea of an objective source of values. He describes his mind as a "computer", but apparently doesn't think that his personal brain or the universe comes from Reason that is personal, or a Being who is reasonable. Hawking even speaks of what is "beautiful" in science, saying, "Science is beautiful when it makes simple explanations of phenomena or connections between different observations." But upon what basis does he recognize phenomena and connections between different observations? Why, in the end, even bother?

In my essay, "Traveling with Walker Percy", I wrote of how Percy, once an avowed disciple of scientism, embraced Catholicism:

Percy often noted the paradoxical fact that man can form a perfect scientific theory explaining the material world –- but cannot adequately account for himself in that theory. Man is the round peg never quite fitting into the square hole of scientism. "Our view of the world, which we get consciously or unconsciously from modern science, is radically incoherent," Percy wrote in his essay "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind." Again, science must either recognize its own limits or create confusion: "A corollary of this proposition is that modern science is itself radically incoherent, not when it seeks to understand things and subhuman organisms and the cosmos itself, but when it seeks to understand man, not man's physiology or neurology or his bloodstream, but man qua man, man when he is peculiarly human. In short, the sciences of man are incoherent." ("The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault In The Modern Mind," p. 271). In a self-interview, "Questions They Never Asked Me," he put the matter more bluntly:

"This life is much too much trouble, far too strange, to arrive at the end of it and then be asked what you make of it and have to answer, 'Scientific humanism.' That won't do. A poor show. Life is a mystery, love is a delight. Therefore, I take it as axiomatic that one should settle for nothing less than the infinite mystery and infinite delight; i.e., God." ("Questions They Never Asked Me," p. 417)

In a nutshell, Hawking can explain much about the physical world. But he cannot explain himself. He cannot account for the mystery of man. He would do well, in all of his genius, to consider these words from Pope Ratzinger:

God made the world so that there could be a space where he might communicate his love, and from which the response of love might come back to him. From God's perspective, the heart of the man who responds to him is greater and more important than the whole immense material cosmos, for all that the latter allows us to glimpse something of God's grandeur.

Related on Ignatius Insight:

• Excerpts from Chance or Purpose: Creation, Evolution, and a Rational Faith | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Mythological Conflict Between Christianity and Science | An interview with physicist Dr. Stephen Barr | Mark Brumley

• The Universe is Meaning-full | An interview with Dr. Benjamin Wiker, co-author of A Meaningful World | Carl E. Olson

• Deadly Architects | An Interview with Donald De Marco & Benjamin Wiker | Carl E. Olson

• The Mystery of Human Origins | Mark Brumley

• Designed Beauty and Evolutionary Theory | Thomas Dubay, S.M.

May 16, 2011

What the Pope might say to Stephen Hawking

The famous theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking was recently interviewed by The Guardian, and revealed that he does, in fact, believe in and worship a god—the name of which is "Science":

What is the value in knowing "Why are we here?"

The universe is governed by science. But science tells us that we can't solve the equations, directly in the abstract. We need to use the effective theory of Darwinian natural selection of those societies most likely to survive. We assign them higher value.

I'm not a physicist, and science was not my favorite subject in high school, but I do know that science (from the Latin, scientia, "having knowledge"), as defined by about any dictionary worth buying, is "an area of knowledge that is an object of study" and/or "knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through the scientific method" (Merriam Webster). So how is it that the study of general laws, which are obtained and tested through the "scientific method"—a human construct and enterprise, correct?—governs the universe? And, no, I'm not being entirely flippant, because while I know that this surely must not be what Hawkings is saying, it is what he is saying. Put another way, he renders science as some sort of abstact, objective giver of truth, and thus seeks to do away with the possibility of God as understood by Christians (as he attempted to do last year). More from the interview:

You've said there is no reason to invoke God to light the blue touchpaper. Is our existence all down to luck?

Science predicts that many different kinds of universe will be spontaneously created out of nothing. It is a matter of chance which we are in.

Was that an answer? Argument? Or simply the pronouncement of a prophet of the god, Science? Should we blithely accept that logic, reason, order, structure, study, and even science can exist—and be proclaimed trustworthy to boot—in a universe/cosmos that came into existence through random chance, has no extrinsic meaning or purpose, and "just is"? Hmmm. It sounds sketchy, at best.

Actually, it's completely unfair to speak ill here of science, because it's not science's fault (since science is an area of knowledge that utilizes a particular method of study, and is thus impersonal) that Hawking seems to be misusing or playing fast and loose with it. Hawking is, whether he knows it or not, following the lead taken by Comte, who claimed (again, in rather pontifical style), "Theology will necessarily vanish in the presence of physics". He is a disciple of scientism, which is a philosophical, pehaps even theological, system of belief. The Dutch philosopher William A. Luijpen, in Phenomenology and Atheism (Duquesne University Press, 1964), wrote of how the "closed realm of the physicist" often leads scientists to embrace atheism. And:

Having resolved to question the objects and phenomena of nature only from the standpoint of measurements, [the physicist] deliminates his field of presence in such a way that nothing that is not quantitative can ever arise in it. In other words, the realm in which the physicist is interested is fundamentally closed. This does not mean that his dialogue with the world is ever finished and complete, but it means that his realm is, as a matter of principle, delimited in such a way that, from the standpoint of the thematizing project of the physicist, nothing can ever come into view except the quantitative. If, nevertheless, the physicist introduces something else, he thereby abandons the questioning attitude that is characteristic of him. For instance, he can be impressed by the greatness of what he sees and call is beautiful, but he thus goes beyond his pursuit as a physicist. In physical science itself nothing is "great" or "beautiful." At the same time, however, it follows that on the basis of his physical science along he can never deny that something is great or beautiful. (pp. 62-3)

A bit later, Luijpen argues, "All this clearly indicates that the physicist, on the basis of his science, lacks competence to deny the existence of the Creator-God, which is affirmed by the believer. The fact that such a denial has been made by scientists in the past, and is made even today, reveals a frightful want of insight into the nature of knowledge." This statement is all the more interesting when read along with the following remarks from Hawking's interview:

So here we are. What should we do?

We should seek the greatest value of our action.

You had a health scare and spent time in hospital in 2009. What, if anything, do you fear about death?

I have lived with the prospect of an early death for the last 49 years. I'm not afraid of death, but I'm in no hurry to die. I have so much I want to do first. I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.

How, then, does science/physics inform us about "the greatest value of our action"? This is like watching actors testifying before Congress about farm bills or economics: everyone is very serious and there is much ponderous head-nodding, but does anyone really think that William Flowinghair, star of The Jaded Nightquest, should really be treated as an expert on the challenges of making a living on 5,000 acres of turnips in Iowa? Which is not to say that Hawking's knowledge or wisdom is necessarily limited to physics, or that he doesn't have a right to say anything at all about his beliefs regarding the Meaning of Everything. No, it is simply to note that when a physicist—even a theoretical physicist—moves into the realm of philosophical or theological musings, folks should keep in mind that he might not be on solid ground or expressing cogent ideas precisely because physics and science, properly speaking, don't tell us anything about "values" and the meaning of life.

Luijpen's remarks as similar to those found in a modestly-titled book, Introduction to Christianity (Ignatius Press, 2004; 2nd edition), originally published in 1968 by then-Fr. Joseph Ratzinger. In the chapter titled, "Faith in God Today", Ratzinger outlined an argument for God's existence based on intelligibility that is directly relevant to Hawking's remarks in particular, but also in general to the ongoing clash (supposed or real) between faith and science.

Ratzinger begins by noting that the statement, "I believe in God", is based on the presupposition that truth can actually be known, considered, and stated. "Christian faith in God means first the decision in favor of the primacy of the logos as against mere matter", he wrote. "In other words, faith means deciding for the view that thought and meaning do not just form a chance by-product of being; that, on the contrary, all being is a product of thought and, indeed, in its innermost structure is itself thought" (pp. 151, 152). Finite being as we experience it is marked by intelligibility, by a formal structure that makes it capable of being understood by the seeking, thinking mind. This recognition of the intelligible, knowable nature of things points to the rational position of belief in creation. It also is the basis for scientific research and thought, for scientists rely—implicitly or otherwise—on the belief that the material realm is intelligible and open to logical study, systematic observation, and ordered experimentation.

Ratzinger quotes Albert Einstein, who said that in the laws of nature "an intelligence so superior is revealed that in comparison all the significance of human thinking and human arrangements is a completely worthless reflection" (p. 153). But he also notes that Einstein was dismissive of belief in a personal God, which the great theoretical physicist dismissed as "anthropomorphic". This reveals, Ratzinger notes, the difficulty many have in believing that the "God of the philosophers" is also the "God of faith", one and the same. But Ratzinger insists that Einstein's view is too limited, too mathematically-focused, and misses the fact that in the world "we also find equally present in the world unparalleled and unexplained wonders of beauty, or, to be more accurate, there are events that appear to the apprehending mind of man in the form of beauty, so that he is bound to say that the mathematician responsible for these events has displayed an unparalleled degree of creative imagination" p. 155). The strange thing is that while physicists such as Hawking apparently think belief in God (and the afterlife) is somehow limiting (and based in some way on fear and superstition), they are the ones who limit themselves by embracing scientism rather than acknowledging the limitations of science proper.

Ratzinger argues that universal objective intelligibility leads to the conclusion of the existence of a great Intelligence, which has thought the world into being. He notes that there are a couple of false beliefs that can arise when it comes to a scientific study of "matter": 1) "Everything we encounter is in the last analysis stuff, matter; this is the only thing that always remains as demonstrable reality and, consequently, represents the real being of all that exists—the materialist solution", and 2) "all being is ultimately being-thought and can be traced back to mind as the original reality; this is the 'idealistic' solution." (p. 156). Rejecting both as unsatisfactory and limited, he goes on to say that "Christian belief in God means that things are the being-thought of a creative consciousness, of a creative freedom, and that the creative consciousness that bears up all things has released what has been thought into the the freedom of its, independent existence. ... the model from which creation must be understood is not the craftsman but the creative mind, creative thinking" (p. 157).

This point is clearly one that Ratzinger/Benedict XVI has dwelt upon over the decades, for in his 2011 Easter Vigil Homily, he again made similar observations, stating:

The central message of the creation account can be defined more precisely still. In the opening words of his Gospel, Saint John sums up the essential meaning of that account in this single statement: "In the beginning was the Word". In effect, the creation account that we listened to earlier is characterized by the regularly recurring phrase: "And God said ..." The world is a product of the Word, of the Logos, as Saint John expresses it, using a key term from the Greek language. "Logos" means "reason", "sense", "word". It is not reason pure and simple, but creative Reason, that speaks and communicates itself. It is Reason that both is and creates sense. The creation account tells us, then, that the world is a product of creative Reason. Hence it tells us that, far from there being an absence of reason and freedom at the origin of all things, the source of everything is creative Reason, love, and freedom. Here we are faced with the ultimate alternative that is at stake in the dispute between faith and unbelief: are irrationality, lack of freedom and pure chance the origin of everything, or are reason, freedom and love at the origin of being? Does the primacy belong to unreason or to reason? This is what everything hinges upon in the final analysis. As believers we answer, with the creation account and with Saint John, that in the beginning is reason. (April 23, 2011)

Hawking talks about the universe being "governed", but denies there is a governor/law-giver. He speaks of "values", but rejects the idea of an objective source of values. He describes his mind as a "computer", but apparently doesn't think that his personal brain or the universe comes from Reason that is personal, or a Being who is reasonable. Hawking even speaks of what is "beautiful" in science, saying, "Science is beautiful when it makes simple explanations of phenomena or connections between different observations." But upon what basis does he recognize phenomena and connections between different observations? Why, in the end, even bother?

In my essay, "Traveling with Walker Percy", I wrote of how Percy, once an avowed disciple of scientism, embraced Catholicism:

Percy often noted the paradoxical fact that man can form a perfect scientific theory explaining the material world –- but cannot adequately account for himself in that theory. Man is the round peg never quite fitting into the square hole of scientism. "Our view of the world, which we get consciously or unconsciously from modern science, is radically incoherent," Percy wrote in his essay "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind." Again, science must either recognize its own limits or create confusion: "A corollary of this proposition is that modern science is itself radically incoherent, not when it seeks to understand things and subhuman organisms and the cosmos itself, but when it seeks to understand man, not man's physiology or neurology or his bloodstream, but man qua man, man when he is peculiarly human. In short, the sciences of man are incoherent." ("The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault In The Modern Mind," p. 271). In a self-interview, "Questions They Never Asked Me," he put the matter more bluntly:

"This life is much too much trouble, far too strange, to arrive at the end of it and then be asked what you make of it and have to answer, 'Scientific humanism.' That won't do. A poor show. Life is a mystery, love is a delight. Therefore, I take it as axiomatic that one should settle for nothing less than the infinite mystery and infinite delight; i.e., God." ("Questions They Never Asked Me," p. 417)

In a nutshell, Hawking can explain much about the physical world. But he cannot explain himself. He cannot account for the mystery of man. He would do well, in all of his genius, to consider these words from Pope Ratzinger:

God made the world so that there could be a space where he might communicate his love, and from which the response of love might come back to him. From God's perspective, the heart of the man who responds to him is greater and more important than the whole immense material cosmos, for all that the latter allows us to glimpse something of God's grandeur.

Related on Ignatius Insight:

• Excerpts from Chance or Purpose: Creation, Evolution, and a Rational Faith | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Mythological Conflict Between Christianity and Science | An interview with physicist Dr. Stephen Barr | Mark Brumley

• The Universe is Meaning-full | An interview with Dr. Benjamin Wiker, co-author of A Meaningful World | Carl E. Olson

• Deadly Architects | An Interview with Donald De Marco & Benjamin Wiker | Carl E. Olson

• The Mystery of Human Origins | Mark Brumley

• Designed Beauty and Evolutionary Theory | Thomas Dubay, S.M.

"If the average Catholic reader could be tracked down..."

... through the swamps of letters-to-the-editor and other places where he momentarily reveals himself, he would be found to be something of a Manichean. By separating nature and grace as much as possible, he has reduced his conception of the supernatural to pious cliche and has become able to recognize nature in literature in only two forms, the sentimental and the obscene. He would seem to prefer the former, while being more of an authority on the latter, but the similarity between the two generally escapes him. He forgets that sentimentality is an excess, a distortion of sentiment, usually in the direction of an overemphasis on innocence; and that innocence, whenever it is overemphasized in the ordinary human condition, tends by some natural law to become its opposite.

We lost our innocence in the fall of our first parents, and our return to it is through the redemption which was brought about by Christ's death and by our slow participation in it. Sentimentality is a skipping of this process in its concrete reality and an early arrival at a mock state of innocence, which strongly suggests its opposite. Pornography, on the other hand, is essentially sentimental, for it leaves out the connection of sex with its hard purposes, disconnects it from its meaning in life and makes it simply an experience for its own sake.

Many well-grounded complaints have been made about religious literature on the score that it tends to minimize the importance and dignity of life here and now in favor of life in the next world or in favor of miraculous manifestations of grace. When fiction is made according to its nature, it should reinforce our sense of the supernatural by grounding it in concrete observable reality. If the writer uses his eyes in the real security of his faith, he will be obliged to use them honestly and his sense of mystery and his acceptance of it will be increased. To look at the worst will be for him no more than an act of trust in God; but what is one thing for the writer may be another for the reader. What leads the writer to his salvation may lead the reader into sin, and the Catholic writer who looks at this possibility directly looks the Medusa in the face and is turned to stone.

That is from Flannery O'Connor's essay, "The Church and the Fiction Writer" (orig. published in America, March 30, 1957), from the indispensible and must-read-it-now-if-you haven't-already! collection Mystery and Manners (Farrar, Straus & Girous, 1961). Earlier today I posted Ronald Webber's 1999 essay, "A Good Writer is Hard to Find", and am pleased that many readers have expressed interest in it.

I reposted Webber's essay in part because I have been reading Peculiar Crossroads: Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, and Catholic Vision in Postwar Southern Fiction (Louisiana State University Press, 2004), by Farrell O'Gorman, professor at DePaul University. It is an excellent work, and I especially recommend it to anyone interested in the writing and thought of either O'Connor and Percy (I tend to think that if you like one, you surely must like the other). Among other things, O'Gorman digs deeply into the theological and philosophical works that influenced both O'Connor and Percy, showing how they shared a deep affection for the writings of Romano Guardini (The End of the Modern World) and Jacques Maritain (Art and Scholasticism), among others (Merton, Marcel, Tate, etc.). He also does a nice job examining some of the significant similarities between the two authors, as well as showing how they differ in various ways.

A bit more from O'Connor:

Henry James said that the morality of a piece of fiction depended on the amount of "felt life" that was in it. The Catholic writer, in so far as he has the mind of the Church, will feel life from the standpoint of the central Christian mystery; that it has, for all its horror, been found by God to be worth dying for.

To the modem mind, as represented by Mr. Wylie, this is warped vision which "bears little or no relation to the truth as it is known today." The Catholic who does not write for a limited circle of fellow Catholics will in all probability consider that since this is his vision, he is writing for a hostile audience, and he will be more than ever concerned to have his work stand on its own feet and be complete and self-sufficient and impregnable in its own right. When people have told me that because I am a Catholic, I cannot be an artist, I have had to reply, ruefully, that because I am a Catholic I cannot afford to be less than an artist.

Read it all on the America website.

• A Good Writer is Hard to Find | Ronald Webber

• "Traveling with Walker Percy" | Carl E. Olson

UNITEforLIFE webcast with Abby Johnson, Tuesday, May 17th

From UnitedForLifeWebcast.org:

On May 17th at 8:00 PM local time*, come be a part of the UNITEforLIFE webcast with Abby Johnson, a former abortion clinic director for Planned Parenthood. Join us for heartfelt discussions as Abby shares her long-held desire to help women in crisis, and the moment of pure awakening that led her to re-evaluate her life's work.

During this webcast, hosted by Kelly Rosati, Vice President of Community Outreach for Focus on the Family, you'll discover why Abby is now an advocate for the pro-life pregnancy centers and clinics around the nation that truly serve women and save lives.

Visit the site to learn more about the webcast and the various speakers who will take part in the event.

CDF's circular letter on "Guidelines in Cases of Sexual Abuse"; Fr. Lombardi's note

From the Vatican Information Service blog, the circular letter from the CDF on developing guideliens for dealing with cases of sexual abuse by clerics, followed by a Note on the letter from the director of the Holy See Press Office, Fr. Federico Lombardi:

CIRCULAR LETTER: GUIDELINES IN CASES OF SEXUAL ABUSE

VATICAN CITY, 16 MAY 2011 (VIS) - The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith today published a circular letter intended to assist Episcopal Conferences in developing Guidelines for dealing with cases of sexual abuse of minors by clerics.

"Among the important responsibilities of the Diocesan Bishop in his task of assuring the common good of the faithful and, especially, the protection of children and of the young, is the duty he has to give an appropriate response to the cases of sexual abuse of minors by clerics in his diocese. Such a response entails the development of procedures suitable for assisting the victims of such abuse, and also for educating the ecclesial community concerning the protection of minors. A response will also make provision for the implementation of the appropriate canon law, and, at the same time, allow for the requirements of civil law.

I. General considerations:

a) The victims of sexual abuse

The Church, in the person of the Bishop or his delegate, should be prepared to listen to the victims and their families, and to be committed to their spiritual and psychological assistance. In the course of his Apostolic trips our Holy Father, Benedict XVI, has given an eminent model of this with his availability to meet with and listen to the victims of sexual abuse. In these encounters the Holy Father has focused his attention on the victims with words of compassion and support, as we read in his 'Pastoral Letter to the Catholics of Ireland' (n.6): 'You have suffered grievously and I am truly sorry. I know that nothing can undo the wrong you have endured. Your trust has been betrayed and your dignity has been violated'.

b) The protection of minors

In some countries programs of education and prevention have been begun within the Church in order to ensure 'safe environments' for minors. Such programs seek to help parents as well as those engaged in pastoral work and schools to recognize the signs of abuse and to take appropriate measures. These programs have often been seen as models in the commitment to eliminate cases of sexual abuse of minors in society today.

c) The formation of future priests and religious

In 2002, Pope John Paul II stated, 'there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young' (n. 3, 'Address to the American Cardinals', 23 April 2002). These words call to mind the specific responsibility of Bishops and Major Superiors and all those responsible for the formation of future priests and religious. The directions given in the Apostolic Exhortation Pastores Dabo Vobis as well as the instructions of the competent Dicasteries of the Holy See take on an even greater importance in assuring a proper discernment of vocations as well as a healthy human and spiritual formation of candidates. In particular, candidates should be formed in an appreciation of chastity and celibacy, and the responsibility of the cleric for spiritual fatherhood. Formation should also assure that the candidates have an appreciation of the Church's discipline in these matters. More specific directions can be integrated into the formation programs of seminaries and houses of formation through the respective Ratio institutionis sacerdotalis of each nation, Institute of Consecrated Life and Society of Apostolic Life.

Particular attention, moreover, is to be given to the necessary exchange of information in regard to those candidates to priesthood or religious life who transfer from one seminary to another, between different dioceses, or between religious Institutes and dioceses.

d) Support of Priests

1. The bishop has the duty to treat all his priests as father and brother. With special attention, moreover, the bishop should care for the continuing formation of the clergy, especially in the first years after Ordination, promoting the importance of prayer and the mutual support of priestly fraternity. Priests are to be well informed of the damage done to victims of clerical sexual abuse. They should also be aware of their own responsibilities in this regard in both canon and civil law. They should as well be helped to recognize the potential signs of abuse perpetrated by anyone in relation to minors;

2. In dealing with cases of abuse which have been denounced to them the bishops are to follow as thoroughly as possible the discipline of canon and civil law, with respect for the rights of all parties;

3. The accused cleric is presumed innocent until the contrary is proven. Nonetheless the bishop is always able to limit the exercise of the cleric's ministry until the accusations are clarified. If the case so warrants, whatever measures can be taken to rehabilitate the good name of a cleric wrongly accused should be done.

e) Cooperation with Civil Authority

Sexual abuse of minors is not just a canonical delict but also a crime prosecuted by civil law. Although relations with civil authority will differ in various countries, nevertheless it is important to cooperate with such authority within their responsibilities. Specifically, without prejudice to the sacramental internal forum, the prescriptions of civil law regarding the reporting of such crimes to the designated authority should always be followed. This collaboration, moreover, not only concerns cases of abuse committed by clerics, but also those cases which involve religious or lay persons who function in ecclesiastical structures.

II. A brief summary of the applicable canonical legislation concerning the delict of sexual abuse of minors perpetrated by a cleric:

On 30 April 2001, Pope John Paul II promulgated the Motu Proprio Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela [SST], by which sexual abuse of a minor under 18 years of age committed by a cleric was included in the list of more grave crimes (delicta graviora) reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). Prescription for this delict was fixed at 10 years beginning at the completion of the 18th year of the victim. The norm of the Motu Proprio applied both to Latin and Eastern clerics, as well as for diocesan and religious clergy.

In 2003, Cardinal Ratzinger, then Prefect of the CDF, obtained from Pope John Paul II the concession of some special faculties in order to provide greater flexibility in conducting penal processes for these more grave delicts. These measures included the use of the administrative penal process, and, in more serious cases, a request for dismissal from the clerical state ex officio. These faculties have now been incorporated in the revision of the Motu Proprio approved by the Holy Father, Benedict XVI, on 21 May 2010. In the new norms prescription, in the case of abuse of minors, is set for 20 years calculated from the completion of the 18th year of age of the victim. In individual cases, the CDF is able to derogate from prescription when indicated. The canonical delict of acquisition, possession or distribution of pedopornography is also specified in this revised Motu Proprio.

The responsibility for dealing with cases of sexual abuse of minors belongs, in the first place, to Bishops or Major Superiors. If an accusation seems true the Bishop or Major Superior, or a delegate, ought to carry out the preliminary investigation in accord with CIC can. 1717, CCEO can. 1468, and SST art. 16.

If the accusation is considered credible, it is required that the case be referred to the CDF. Once the case is studied the CDF will indicate the further steps to be taken. At the same time, the CDF will offer direction to assure that appropriate measures are taken which both guarantee a just process for the accused priest, respecting his fundamental right of defence, and care for the good of the Church, including the good of victims. In this regard, it should be noted that normally the imposition of a permanent penalty, such as dismissal from the clerical state, requires a penal judicial process. In accord with canon law (cf. CIC can. 1342) the Ordinary is not able to decree permanent penalties by extrajudicial decree. The matter must be referred to the CDF which will make the definitive judgement on the guilt of the cleric and his unsuitability for ministry, as well as the consequent imposition of a perpetual penalty (SST art. 21, '2).

The canonical measures applied in dealing with a cleric found guilty of sexual abuse of a minor are generally of two kinds: 1) measures which completely restrict public ministry or at least exclude the cleric from any contact with minors. These measures can be reinforced with a penal precept; 2) ecclesiastical penalties, among which the most grave is the dismissal from the clerical state.

In some cases, at the request of the cleric himself, a dispensation from the obligations of the clerical state, including celibacy, can be given pro bono Ecclesiae.

The preliminary investigation, as well as the entire process, ought to be carried out with due respect for the privacy of the persons involved and due attention to their reputations.

Unless there are serious contrary indications, before a case is referred to the CDF, the accused cleric should be informed of the accusation which has been made, and given the opportunity to respond to it. The prudence of the bishop will determine what information will be communicated to the accused in the course of the preliminary investigation.

It remains the duty of the Bishop or the Major Superior to provide for the common good by determining what precautionary measures of CIC can. 1722 and CCEO can. 1473 should be imposed. In accord with SST art. 19, this can be done once the preliminary investigation has been initiated.

Finally, it should be noted that, saving the approval of the Holy See, when a Conference of Bishops intends to give specific norms, such provisions must be understood as a complement to universal law and not replacing it. The particular provisions must therefore be in harmony with the CIC / CCEO as well as with the Motu Proprio Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela (30 April 2001) as updated on 21 May 2010. In the event that a Conference would decide to establish binding norms it will be necessary to request the recognitio from the competent Dicasteries of the Roman Curia.

III. Suggestions for Ordinaries on Procedures:

The Guidelines prepared by the Episcopal Conference ought to provide guidance to Diocesan Bishops and Major Superiors in case they are informed of allegations of sexual abuse of minors by clerics present in the territory of their jurisdiction. Such Guidelines, moreover, should take account of the following observations:

a.) the notion of 'sexual abuse of minors' should concur with the definition of article 6 of the Motu Proprio SST ('the delict against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue committed by a cleric with a minor below the age of eighteen years'), as well as with the interpretation and jurisprudence of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, while taking into account the civil law of the respective country;

b.) the person who reports the delict ought to be treated with respect. In the cases where sexual abuse is connected with another delict against the dignity of the sacrament of Penance (SST art. 4), the one reporting has the right to request that his or her name not be made known to the priest denounced (SST art. 24);

c.) ecclesiastical authority should commit itself to offering spiritual and psychological assistance to the victims;

d.) investigation of accusations is to be done with due respect for the principle of privacy and the good name of the persons involved;

e.) unless there are serious contrary indications, even in the course of the preliminary investigation, the accused cleric should be informed of the accusation, and given the opportunity to respond to it.

f.) consultative bodies of review and discernment concerning individual cases, foreseen in some places, cannot substitute for the discernment and potestas regiminis of individual bishops;

g.) the Guidelines are to make allowance for the legislation of the country where the Conference is located, in particular regarding what pertains to the obligation of notifying civil authorities;

h.) during the course of the disciplinary or penal process the accused cleric should always be afforded a just and fit sustenance;

i.) the return of a cleric to public ministry is excluded if such ministry is a danger for minors or a cause of scandal for the community.

Conclusion

The Guidelines developed by Episcopal Conferences seek to protect minors and to help victims in finding assistance and reconciliation. They will also indicate that the responsibility for dealing with the delicts of sexual abuse of minors by clerics belongs in the first place to the Diocesan Bishop. Finally, the Guidelines will lead to a common orientation within each Episcopal Conference helping to better harmonize the resources of single Bishops in safeguarding minors."

NOTE ON THE CIRCULAR LETTER:

VATICAN CITY, 16 MAY 2011 (VIS) - Below is the note from the director of the Holy See Press Office, Fr. Federico Lombardi S.J., regarding the Circular Letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to the Episcopal Conferences on the Guidelines for dealing with cases of sexual abuse of minors by clerics:

"The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has asked every Bishops' Conferences in the world to prepare 'Guidelines' for dealing with cases of sexual abuse of minors by clergy, in ways appropriate to specific situations in different regions, by May 2012.

In its 'Circular Letter', the Congregation has offered a broad set of principles and indications, which will not only facilitate the formulation of the guidelines and therefore a uniformity of conduct of ecclesiastical authorities in various nations, but will also ensure consistency at the level of the universal Church, while respecting the competence of bishops and religious superiors.

Priority is given to victims, prevention programs, seminary formation and an ongoing formation of clergy, cooperation with civil authorities, the careful and rigorous implementation of the most canonical recent legislation in the area are the principal considerations that must structure the Guidelines in every corner of the world.

* * *

In recent days, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has sent to all Episcopal conferences a 'Circular Letter to assist Episcopal Conferences in developing Guidelines for dealing with cases of sexual abuse of minors perpetrated by clerics'.

The preparation of the document was announced in July, at the time of the publication of new rules for the implementation of the Motu Proprio " Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela " (see Note Fr. F. Lombardi, in OR, 16/07/2010, 1, and www.vatican.va, Abuse of minors. The Church's response).

H.E., Cardinal Levada, Prefect of the Congregation, later informed of its preparation during the meeting of the Cardinals at the November Consistory (see Press Release on the Afternoon Session, 11/19/2010).

The document is accompanied by a letter of presentation, signed by Cardinal Levada, illustrating its nature and purpose.

Following the revision of norms on sexual abuse of minors by members of the clergy, approved by the Pope last year, 'it seems opportune that each Episcopal Conference prepare Guidelines' whose purpose will be to assist the Bishops of the Conference to follow clear and coordinated procedures in dealing with these instances of abuse. Such Guidelines would take into account the concrete situation of the jurisdictions within the Episcopal Conference.

To this end, the Circular Letter 'contains general themes' for consideration which naturally must be adapted to national realities, but which will help to ensure a coordinated approach by the various episcopates as well as - precisely thanks to the Guidelines - within the Episcopal Conferences.

Regarding the drafting of new Guidelines or the revision of existing ones, Cardinal Levada's letter also gives two indications: first, to involve the Major Superiors of clerical religious Institutes (to take into account not only diocesan clergy, but also religious), and then to send a copy of the completed Guidelines to the Congregation by the end of May 2012.

In conclusion, two concerns are clear:

1. The need to address the problem promptly and effectively with clear, organic, indications that are suitable to local situations and in relation to the norms and civil authorities. The indication of a specific date and a relatively short period within which all Episcopal conferences must develop Guidelines is clearly a very strong and eloquent statement.

2. Respect for the fundamental competence of the diocesan bishops (and Major Superiors) in the matter (the wording of the Circular is very keen to stress this aspect: the guidelines are intended to 'assist the diocesan bishops and Major Superiors').

The Circular Letter itself is short but very dense, and is divided into three parts.

The first part develops a set of general considerations, including in particular:

Priority attention to the victims of sexual abuse: listening to the victims and their families, and a commitment to their spiritual and psychological assistance.

The development of prevention programs to create truly safe environments for children.

The formation of future priests and religious and exchange of information on candidates to the priesthood or religious life who are transferred.

Support for priests, their ongoing formation and informing them of their responsibilities regarding the issue, how to support them when they are accused, dealing with cases of abuse according to law, the rehabilitation of the good reputation of those who have been unjustly accused.

Cooperation with civil authorities within their responsibilities. 'Specifically, without prejudice to the sacramental internal forum, the prescriptions of civil law regarding the reporting of such crimes to the designated authority should always be followed'. This cooperation should be implemented not only in cases of abuse by clergy, but by any employee who works in a Church structure.

The second part addresses applicable canonical legislation in force today, after the revision of 2010.

It refers to the power of bishops and Major Superiors in preliminary investigation and, in the case of a credible allegation, their obligation to refer the matter to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which offers guidance for the handling of the case.

It speaks about the precautionary measures to be imposed and information to be given to the accused during the preliminary investigation.

It refers to the canonical measures and ecclesiastical penalties that can be applied to offenders, including dismissal from the clerical state.

Finally, it specifies the relationship between canon law valid for the entire Church and any additional specific particular norms that given Episcopal Conferences deem appropriate or necessary, and the procedure to be followed in such cases.

The Third and final part lists a number of useful observations in formulating concrete operational guidelines for bishops and major superiors.

Among other things, the need to offer assistance to victims is stressed as well as the need to treat the complainant with respect and ensure the privacy and reputation of the people involved; to take due account of the civil laws of the country, including any obligation to notify the civil authorities; to ensure the accused information on the allegation and an opportunity to respond, and in any case a just and worthy support; to exclude the cleric's return to public ministry, in case of danger to minors or of scandal to the community. Once again, the primary responsibility of bishops and Major Superiors is reiterated, a responsibility which can not be replaced by supervisory bodies, however useful or necessary they may be in support of this responsibility.

The Circular therefore represents a very important new step in promoting awareness throughout the Church of the need and urgency to effectively respond to the scourge of sexual abuse by members of the clergy. Only in this way can we renew full credibility in the witness and educational mission of the Church, and help create in society in general, safe educational environments of which there is an urgent need."

Sins of the Father: Abortion, Birth Control, and the ACLU

By Dr. Paul Kengor

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the National Catholic Register and on the "Center for Vision and Values" website.

As someone with the highly unusual task of researching old, declassified Soviet and Communist Party USA archives, I often get quizzical looks as to why certain things from the distant past still matter.

Well, it's indeed true that past is often prologue. And it's striking to see how something in communist archives from, say, the 1920s, pertains to America right now.

That certainly seems the case with what I've found on the American Civil Liberties Union, whether challenging Christmas carols in public schools seven decades ago, or, currently, trying to compel Catholic hospitals to do abortions, or denouncing the Catholic bishops for opposing birth-control funding in "healthcare" legislation.

How ironic that I would find seeds of these things in communist archives, or, even more directly, in the pro-communist or pro-Soviet writings of the ACLU's founders.

The ACLU's early atheism is no surprise; its founders' sympathies toward Bolshevism and the Soviet state are not disconnected from that atheism. Yet, most interesting, and unexpected, is how the ACLU's founders' views on the Leninist-Stalinist state's advancement of abortion and birth control are connected—symbolically, at the least—to the organization's advancement of abortion and birth control today.

Consider the founder of the ACLU, Roger Baldwin:

To get a sense of where Baldwin stood on all this, the best source is his 1928 book, Liberty Under the Soviets. The title was no joke. This champion of American "liberties," like many ACLU founders, was fascinated with the Leninist-Stalinist state, having travelled there with other progressives in the hope that they had found the new world.

As to Baldwin and abortion and birth control, it isn't easy to pin him down at the time of the Soviet legalization in the early 1920s. That said, Baldwin's book comes close. Baldwin had to tread lightly on abortion in particular, as did birth-control feminists like racial-eugenicist Margaret Sanger, Planned Parenthood founder. Baldwin understood that only the most vulgar Americans considered legalizing abortion.

So, what did Baldwin say about these things in Liberty Under the Soviets? He hailed the "significant" "new freedom of women" in Soviet Russia. On page 118, he came nearer to endorsing Soviet abortion and birth-control policy:

Birth control is legal throughout Russia, but not encouraged as an official policy. Abortions are legal also, but may be performed legally only in hospitals or by qualified physicians upon permits issued by local commissions to whom women apply. This, however, does not prevent illegal abortions by practitioners to whom women may go when refused permission by the commission. Birth control not being generally understood and abortions being controlled, women are not yet freed from unwilling child-bearing, though the regime is extending its efforts to aid them.

Such are the freedoms of women under the Soviets today, on paper and in practice. On paper they are an advance over the status of women elsewhere in the world, pushing to their logical ends what are only tendencies in other lands. In practice they are a great advance over the very limited position of women before the Revolution.

Here, Baldwin seemed to support the Soviet legalization of abortion and birth control, and generally freeing women from the shackles of "unwilling child-bearing." This he viewed as an advance, if not "great advance."

Where did Soviet Russia go from here? The rest of the story is hellacious.

Within a decade, there were millions of abortions. It got so bad that Joseph Stalin, mass-murdering tyrant, was horrified, and actually temporarily banned abortion, given that entire future generations were being wiped out in the womb. Re-legalization took place under Nikita Khrushchev in the mid-1950s. By the 1970s, there was a staggering seven to eight million abortions per year in the USSR. The very worst year for abortion in America, post-Roe, pales to the average year in the Soviet Union. To the extent that Roger Baldwin supported that legalization, here was the bitter fruit.

To that end, the ACLU is a group with some rotten roots, and I believe today, a century later, we are reaping the dark harvest in America. When the ACLU today challenges the liberty of Catholic hospitals to refuse to do abortions—obscene as that challenge is—or blasts bishops for opposing taxpayer-funded contraception, it isn't a surprise to those of us familiar with the sins of the father.

Dr. Paul Kengor is professor of political science at Grove City College, executive director of The Center for Vision & Values, and author of the newly released Dupes: How America's Adversaries Have Manipulated Progressives for a Century . His other books include The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of Communism , God and Ronald Reagan , and (as co-author) of The Judge: William P. Clark, Ronald Reagan's Top Hand (Ignatius Press, 2007).

Announcing the International Symposium, "Council and Continuity", Oct. 3-4, 2011

The Worship and Liturgy office of the Diocese of Phoenix (AZ) is hosting an international symposium, "Council and Continuity", on October 3 and 4, 2011, that will focus on "the interim missals and the immediate post-conciliar liturgical reform."

Addresses and speakers include:

• Opening: Greetings and Introduction – Bishop Thomas Olmsted, M.A.Th., J.C.D.

• The Historical Development of the Mass from its Origins to Sacrosanctum Concilium – Prof. Dr. H.-J. Feulner, S.T.L., S.T.D.

• The Historical Development of the Mass from Sacrosanctum Concilium to the Present – Prof. D. Martis, M.Div., S.T.L., Ph.D., S.T.D.

• The Latin-English Missals of 1964/66 (US) – A. Bieringer, M.A., M.A.Th.

• The Liturgical Renewal and the Ordo Missae (1965) – Rev. Deacon Prof. Dr. H. Hoping, S.T.D.

• Vespers with Homily – Bishop S. Cordileone, B.A., S.T.B., J.C.D

• Liturgy – Continuity or Rupture? Possibilities for Further Liturgical Development and Its Pastoral Relevance – Bishop P. Elliott, M.A., D.D., S.T.D.

There are also a number of minor lectures. Full details and information about registration can be found on the Diocese of Phoenix website.

A Good Writer is Hard to Find

A Good Writer is Hard to Find | Ronald Webber | Ignatius Insight

The great American author Flannery O'Connor once remarked, "When people have told me that because I am a Catholic, I cannot be an artist, I have had to reply, ruefully, that because I am a Catholic, I cannot afford to be less than an artist." "I have found... from reading my own writing, that my subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil. I have also found that what I write is read by an audience which puts little stock either in grace or the devil."

"If these stories are in fact the work of a young lady," Evelyn Waugh responded when the publisher sent him advance proofs of the volume, "they are indeed remarkable." The young lady in question was Flannery O'Connor and the short stories were in a collection called A Good Man is Hard to Find. The year was 1955.

Waugh's caution about the authorship of the stories is understandable. The stories were fierce, violent, and darkly comic in a Southern Gothic tradition extending from Poe to Faulkner – hardly the expected work of a young lady. Moreover, the accomplished technique suggested that the stories came from the hand of a mature practitioner rather than a new writer.

About the fundamental merit of the work, though, Waugh had no doubt. The stories had been sent to him in the hope of gaining an advertising blurb from an honored, widely-known Catholic writer. One can imagine that he found in them – stories from the other side of the Atlantic and in a uniquely American mode – a reflection of his own moral views and literary aims. Here indeed was another remarkable Catholic writer.

Like Waugh, O'Connor made no secret of her religious faith and its central place in her writing. "I write the way I do because and only because I am a Catholic," she declared. "I feel that if I were not a Catholic I would have no reason to write, no reason to see, no reason to feel horrified or even to enjoy anything." As she well knew, the remark flies in the face of conventional aesthetic wisdom. Religious commitment – so the view goes – limits a writer's freedom to portray life as it is, the world as it turns. O'Connor held that the reverse was true. "When people have told me that because I am a Catholic, I cannot be an artist, I have had to reply, ruefully, that because I am a Catholic, I cannot afford to be less than an artist."

On the surface her work is far removed from the recognizable Catholic world. Catholic characters and settings are almost entirely absent, as is the familiar language of Catholic spirituality. O'Connor's fictional world is drawn from Southern backwoods fundamentalism – a world of self-proclaimed prophets, tent revivals, and rocks scrawled with the bald truth that "Jesus saves." Yet behind the stories, propelling the characters in artfully-made plots often ending in violent death, is a deeply serious and sophisticated Catholicism.

O'Connor was born into a Catholic family in Savannah, Georgia, in 1925, graduated from Georgia State College for Women (now Georgia College) in Milledgeville, and went on to the graduate writing program at the University of Iowa. While still in Iowa she published her first short story and, on the basis of a portion of the manuscript, received a publisher's prize for her first novel, Wise Blood, and admission to the artistic community at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York.

She was working on the novel and staying with the family of the poet Robert Fitzgerald and his wife Sally in rural Connecticut when she was stricken with lupus, the disease that had taken her father's life at an early age. Thereafter she returned to the South, living with her mother on a family farm outside Milledgeville until her death in 1964 at age 39.

In her abbreviated writing life O'Connor published two novels, The Violent Bear It Away in addition to Wise Blood, and two collections of stories, the second, Everything That Rises Must Converge (the title drawn from Teilhard de Chardin, a writer O'Connor admired), appearing shortly after her death. The Complete Stories of Flannery O'Connor, published in 1971, won the National Book Award for fiction and has remained in print ever since. The recently published Best American Short Stories of the Century, co-edited by John Updike, includes her powerful story "Greenleaf."

O'Connor's critical success as a writer, both early and late in her career, belies the difficulty her work posed – poses still – for many readers. The violence of her stories and novels can seem harsh and unfeeling, overwhelming her moral vision as well as her comic effects. O'Connor's explanation for the off-putting "grotesque" elements in her fiction was characteristically forthright: "The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural .... When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock – to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures."

The same point was offered in a different way when she remarked that "I have found... from reading my own writing, that my subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil. I have also found that what I write is read by an audience which puts little stock either in grace or the devil."

Given the dramatic necessities of fiction, the action of grace in O'Connor's work is usually collapsed into a brief encounter rather than parcelled out as prolonged experience. Similarly, the instrument of grace is more often than not outfitted as one of the devil's disciples rather than an angelic presence. In the title story of the collection A Good Man Is Hard to Find, for example, grace comes to a pride-stuffed grandmother in the person of an escaped killer known as the Misfit. After each member of the grandmother's family is systematically shot, the Misfit fires three bullets into the old woman's chest. A grim ending, needless to say – but in the story, O'Connor insisted, the reader "should be on the lookout for such things as the action of grace in the Grandmother's soul, and not for the dead bodies."

In other of her works grace arrives with a Bible-selling seducer, a displaced person from Poland, a college girl from Wellesley, a club-footed juvenile delinquent, a seemingly blind street preacher and his ribald daughter. And the bodies pile up: shot, hung, beaten, gored by a bull, overrun by a tractor. But it remains that the heart of the matter for O'Connor is never the violent end but what precedes it – the response to grace that opens the way to Divine life, or blocks it forever.

It is the action of grace, not the inner nature of the experience – what, if anything, a character feels or comprehends – that we witness in O'Connor's fiction. A notable exception is "The Artificial Nigger," a story O'Connor called "my favorite and probably the best thing I'll ever write." Here the content of grace is revealed in the astonishing insight of a prideful old man, Mr. Head, who has cruelly denied knowing his grandson Nelson, then been forgiven by the boy. "He stood appalled, judging himself with the thoroughness of God, while the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it. He had never thought himself a great sinner before but he saw now his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair. He realized that he was forgiven for sins from the beginning of time, when he had conceived in his own heart the sin of Adam, until the present, when he had denied poor Nelson. He saw that some sin was too monstrous for him to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise."

Understood as the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil, O'Connor's fiction can seem written to a rigid formula – and a formula to which Catholic readers would seem to have special access. In fact, the stories and novels are vastly richer and more complex than any formula can suggest – and disturbing for readers regardless of religious belief. "Catholic life as seen by a Catholic," O'Connor noted, "doesn't always make comfortable reading for Catholics." She added, "We Catholics are very much given to the Instant Answer. Fiction doesn't have any. It leaves us, like Job, with a renewed sense of mystery."

At the same time that her fiction renews the sense of spiritual mystery, it relishes in full measure the human comedy in its backwoods Southern variety. For the antics and especially the talk of that world, O'Connor had an exact eye and perfect pitch. The extended opening scene in a doctor's office in "Revelation" – thought by many to be her finest story – is a telling example.

Until the long-awaited biography of O'Connor appears, the most revealing account of her private and professional life comes from her letters, collected in a 600 page volume called The Habit of Being, the title drawn by the editor, Sally Fitzgerald, from O'Connor's admiration for Jacques Maritain's Art and Scholasticism. The letters show in ample detail not only the habit of art and unwavering religious faith but O'Connor's zest for the immediate world about her.

In one letter she reports that her mother was "vastly insulted" by Evelyn Waugh wondering if her daughter's stories were really the work of a young lady, putting "the emphasis on if and lady." "Does he suppose you're not a lady?" her mother asked. And added, "Who is this Evalin Wow?"

[This article originally appeared in the July-August 1999 edition of Catholic Dossier.]