Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 316

May 30, 2011

The Preface to "The Retrial of Joan of Arc"

... by Régine Pernoud:

In 1839, that learned scholar Vallet de Viriville assessed the number of works devoted to Joan of Arc at five hundred; fifty years later the figure had increased fivefold. Yet the interest she aroused in the nineteenth century is as nothing compared with the interest she has aroused since then. In France, her day has become both a religious and a national festival, Church and state finding themselves at one in raising her likeness on the altar and in the public square. More important, Joan has assumed for our age a living reality unimaginable a hundred years ago.

This being so, it is strange that a document of cardinal importance in Joan's story has been neglected. The detailed record of the trial in which Joan was condemned has been several times published and translated and is familiar in outline even to the  general public; one cannot say the same of the record of the proceedings that led to her rehabilitation. This record is well known to specialists and has been much drawn upon by historians--generally at second hand--but the only edition today available is a transcription of the Latin version prepared by Jules Quicherat. It is an admirable work, but it has been unprocurable for many years, not only in the bookshops but also in the majority of libraries. As for translations, there is only the very fragmentary one made by Eugene O'Reilly [1] and used by Joseph Fabre, dating from 1868 and 1888 respectively; [2] and it is, moreover, stiff reading.

general public; one cannot say the same of the record of the proceedings that led to her rehabilitation. This record is well known to specialists and has been much drawn upon by historians--generally at second hand--but the only edition today available is a transcription of the Latin version prepared by Jules Quicherat. It is an admirable work, but it has been unprocurable for many years, not only in the bookshops but also in the majority of libraries. As for translations, there is only the very fragmentary one made by Eugene O'Reilly [1] and used by Joseph Fabre, dating from 1868 and 1888 respectively; [2] and it is, moreover, stiff reading.

That is all that we have of the only great document--except the account of her trial and condemnation--that throws on Joan, her personality, and her times the direct light of living men's evidence, reflected by no distorting mirror of chronicle or tale. What is more, the account of her condemnation, though it gives the drama at Rouen, leaves the details of Joan's life in shadow, whereas the record of her rehabilitation presents all the stages and essential episodes, one by one, from her baptism in the parish church of Domremy to her burning. (It also shows the impression she made on the crowds.) And it is her childhood friends, her comrades in arms, her former judges, who come, one after another, to evoke her memory; those same persons who had been the actors, or at least the supernumeraries, in the drama of which she was the heroine.

What is more, this rehabilitation suit, staged a bare twenty years after Joan's execution, in itself forms a strange enough page in history; it dealt with events still recent and tinged with the miraculous, events of which men were then free to measure the repercussions. For if we are in a better position than her contemporaries to analyze their effect on the structure of Europe, there was not, on the other hand, a single peasant or townsman in France whose life would not have been changed, to a greater or lesser extent, by the outcome of those battles that decided whether France should remain attached to England or be free. Finally, the case that was being argued was a singularly moving one: a victim, a woman, a mere girl had been burnt alive by judicial decree, and the question was whether that victim was a heroine or a simple visionary--that is to say, a dangerous heretic.

The majority of historians have, inexplicably, failed to recognize the importance of the case. Many, looking through entirely modern spectacles, have been unable to see what it revealed to contemporaries. They have assumed the knowledge at that time of certain truths that, in fact, could not have come to light but for the suit for Joan's rehabilitation. It is, however, indisputable that the details, both of her career and her condemnation, were unknown to the great majority: the details of her heroism to people who had lived in the occupied zone, the details of her trial to the former inhabitants of free France. Facts that are absolutely familiar to us--the falsification or omission of certain documents in her trial--were totally unknown to those very men who undertook her rehabilitation. Finally, it is beyond doubt that public opinion, whether for or against Joan, was only inaccurately informed about her story, and that it was the suit that brought the truth to light. Some historians have even thought it possible to regard the whole rehabilitation suit as a cleverly staged play, put on either by the Church or the King. But if one takes the trouble to follow the stages of this affair, the development of which took no less than seven years and called together people from every district of France and from all social classes, it is clear that a piece of mummery on such a scale would have been difficult to carry through.

It will be up to the reader, in any case, to judge the facts from the documents of the case, which we intend to put before him in a translation as close as possible to the original text. There could be no question of publishing the complete record of the trial. With the account of each hearing and such legal documents as writs and summonses, it fills no less than octavo pages in Quicherat's edition--and even so he omitted the majority of the preliminary reports (nineteen in all) drawn up in preparation for the case, and likewise the Recollectio, or general résumé of the whole proceedings made by Jean Bréhal (the Inquisitor entrusted with its conduct), which alone takes up a whole volume. We have extracted only the parts that are to us most alive and most valuable--that is to say, the statements of the witnesses- suppressing only repetitions that would have made the book bulkier without adding anything new. We have, in addition, put back into the first person those statements that the scribe had transposed into the third on translating them into Latin--"The witness says that ... , etc."--in which he followed the habitual procedure in ecclesiastical courts.

ENDNOTES:

[1] This was, of course, a translation into French.

[2] For these works, see the Bibliography.

May 28, 2011

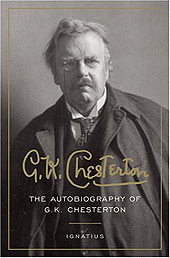

Happy Birthday, G. K. Chesterton!

Chesterton was born on this day in 1874, in Campden Hill in Kensington, London.

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) Author Page | Ignatius Insight

• Articles By and About G. K. Chesterton

• Ignatius Press Books about G. K. Chesterton

• Books by G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton: "Who is this guy and why haven't I heard of him?"

A pithy bio of G.K. Chesterton by Dale Ahlquist, President, American Chesterton Society

I've heard the question more than once. It is asked by people who have just started to discover G.K. Chesterton. They have begun reading a Chesterton book, or perhaps have seen an issue of Gilbert! Magazine, or maybe they've only encountered a series of pithy quotations that marvelously articulate some forgotten bit of common sense. They ask the question with a mixture of wonder, gratitude and . . . resentment. They are amazed by what they have discovered. They are thankful to have discovered it. And they are almost angry that it has taken so long for them to make the discovery.

"Who is this guy. . .?"

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) cannot be summed up in one  sentence. Nor in one paragraph. In fact, in spite of the fine biographies that have been written of him, (and his Autobiography) he has never been captured between the covers of one book. But rather than waiting to separate the goats from the sheep, let's just come right out and say it: G.K. Chesterton was the best writer of the twentieth century. He said something about everything and he said it better than anybody else. But he was no mere wordsmith. He was very good at expressing himself, but more importantly, he had something very good to express. The reason he was the greatest writer of the twentieth century was because he was also the greatest thinker of the twentieth century.

sentence. Nor in one paragraph. In fact, in spite of the fine biographies that have been written of him, (and his Autobiography) he has never been captured between the covers of one book. But rather than waiting to separate the goats from the sheep, let's just come right out and say it: G.K. Chesterton was the best writer of the twentieth century. He said something about everything and he said it better than anybody else. But he was no mere wordsmith. He was very good at expressing himself, but more importantly, he had something very good to express. The reason he was the greatest writer of the twentieth century was because he was also the greatest thinker of the twentieth century.

Born in London, Chesterton was educated at St. Paul's, but never went to college. He went to art school. In 1900, he was asked to contribute a few magazine articles on art criticism, and went on to become one of the most prolific writers of all time. He wrote a hundred books, contributions to 200 more, hundreds of poems, including the epic Ballad of the White Horse, five plays, five novels, and some two hundred short stories, including a popular series featuring the priest-detective, Father Brown. In spite of his literary accomplishments, he considered himself primarily a journalist. He wrote over 4000 newspaper essays, including 30 years worth of weekly columns for the Illustrated London News, and 13 years of weekly columns for the Daily News. He also edited his own newspaper, G.K.'s Weekly. (To put it into perspective, four thousand essays is the equivalent of writing an essay a day, every day, for 11 years. If you're not impressed, try it some time. But they have to be good essays, all of them, as funny as they are serious, and as readable and rewarding a century after you've written them.)

Chesterton was equally at ease with literary and social criticism, history, politics, economics, philosophy, and theology. His style is unmistakable, always marked by humility, consistency, paradox, wit, and wonder. His writing remains as timely and as timeless today as when it first appeared, even though much of it was published in throw away paper.

The Spirit of Truth, the Soul of the Church

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for the Sixth Sunday of Easter | May 29, 2011 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Acts 8:5-8, 14-17

• Ps 66:1-3, 4-5, 6-7, 16, 20

• 1 Pt 3:15-18

• Jn 14:15-21

The last sermon I heard as a Protestant stunned me. The preacher argued that it was better to "have the Holy Spirit" than to "have Christ". He wasn't merely contrasting the work and persons of the Son and the Holy Spirit, he was actually pitting them against one another.

Various Catholics have also, in their own way, misunderstood the work of the third person of the Trinity. The thirteenth-century monk, Joachim of Fiore, created an elaborate interpretation of history associating the Father with the Old Testament and the Son with the hierarchical Church. Joachim taught that the perfect kingdom of the Holy Spirit would be ushered into being around the year 1260, and that true peace and spiritual wholeness—without any need for Church authority—would finally be established.

But pitting the Holy Spirit against the Father or the Son is simply bad theology; it misrepresents the essential relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, which is perfect, self-giving love. The Holy Spirit is both a gift of the Father and the Son and the soul of the Church. In today's reading from the Gospel of John, the Son, who was sent by the Father, tells the disciples that He will, in turn, ask the Father to send "another Advocate…the Spirit of truth." The word Advocate, or Paraclete, refers to someone who comes to our side to console us and intercedes on our behalf. Jesus is the first advocate; the Holy Spirit is the second.

"The Spirit of truth," states the Catechism, "the other Paraclete, will be given by the Father in answer to Jesus' prayer; he will be sent by the Father in Jesus' name; and Jesus will send him from the Father's side, since he comes from the Father" (par 729). Each of the three persons of the Trinity is completely God by nature; they are distinguished by their relationship with one another, in the way they work to bring about the salvation of mankind.

Some of the early Church Fathers pointed out that the Trinity was revealed as it was due to God's gracious condescension to man's weakened mind and heart. The Holy Spirit would not be fully revealed until the Son was shown to be one with the Father. Therefore, "the sending of the person of the Spirit after Jesus' glorification reveals in its fullness the mystery of the Holy Trinity" (CCC, par 244).

A major theme of the Acts of the Apostles is how the will of the Father and the work of the Son are carried out by the Holy Spirit through the Church. The Holy Spirit, the soul of the Church, unifies and directs the Apostles, their successors, and the members of Christ's Mystical Body (cf., CCC 797-8). Today's reading from the Acts of the Apostles recounts how some Samaritans who had accepted the Gospel because of Philip's preaching needed the authority of the Apostles Peter and John in order to receive the Holy Spirit. Philip apparently had been ordained and blessed by the Apostles (Acts 6:5-6), but it was, as John Chrysostom explained, "the prerogative of the apostles" to give the Holy Spirit.

Likewise, Peter was directed by God to impart the gift of the Holy Spirit on the first Gentile converts, an act the Apostle recognized as a continuation of the work of Pentecost: "As I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell on them just as on us at the beginning" (Acts 11:15). The early Church grew through the power of the Holy Spirit and the fearless witness of the men who had been given the Spirit of Truth by the Son. And the purpose Christ's salvific work, as Peter remarked in his first epistle, is "that he might lead you to God."

As another Apostle wrote, "There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call..." (Eph 4:4). If we have the Holy Spirit, we most certainly have Jesus Christ.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the April 27, 2008, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

May 27, 2011

Tracey Rowland on Jesus as Eternal High Priest and Sacrificial Victim

The wonderful Tracey Rowland reflects on Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week: From the Entrance Into Jerusalem To The Resurrection, by Benedict XVI:

The second volume of Pope Benedict's Jesus of Nazareth covers the events in the life of Jesus from his triumphal entry into Jerusalem to his even more triumphal resurrection.

One emphasis which flows through the chapters like a watermark is the pivotal position of Christ bridging the Old and Testaments, bringing one to fulfilment and inaugurating the other. In the mysteries of Holy Week Jesus is revealed as the eternal high priest and sacrificial victim as well as the King of his people.

In an address given in Jerusalem in 1994 at the invitation of Rabbi Rosen, Joseph Ratzinger described Christ's crucifixion as an 'act endured in innermost solidarity with the Law and with Israel' and he noted that the crucifixion was the perfect realisation of what the signs of the Jewish Day of Atonement signify. As he explained, all sacrifices are acts of representation, which, from being typological symbols in the Old Testament, become reality in the life of Christ, so that the symbols can be dropped without one iota being lost:

The universalising of the Torah by Jesus, as the New Testament understands it, is not the extraction of some universal moral prescriptions from the living whole of God's revelation. It preserves the unity of cult and ethos. The ethos remains grounded and anchored in the cult, in the worship of God, in such a way that the entire cult is bound together in the Cross, indeed, for the first time it has become fully real.

Similarly, in an address to the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences in Paris he noted that both the Letter to the Hebrews and the Gospel of John go beyond the link of the Last Supper to the Pasch and view the Eucharist in connection with the Day of Atonement. Christ, who makes an offering of himself on the Cross, is the true and eternal high priest anticipated symbolically by the Aaronic priesthood. To borrow a phrase from the Oxford Professor of Poetry, Geoffrey Hill, this was 'no bloodless myth'.

The Atonement of Christ as both the eternal high priest and sacrificial victim not only fulfils the Old Testament in the sense of transfiguring its symbols into a new reality it also gives rise to a new sovereignty, a new kingship.

Read the entire piece, "No Bloodless Myth: Jesus of Nazareth as the Eternal High Priest and Sacrificial Victim", on The Christocentric Life blog.

The Trinity: Three Persons in One Nature

The Trinity: Three Persons in One Nature | Frank Sheed | From Theology and Sanity | Ignatius Insight

The notion is unfortunately widespread that the mystery of the Blessed Trinity is a mystery of mathematics, that is to say, of how one can equal three. The plain Christian accepts the doctrine of the Trinity; the "advanced" Christian rejects it; but too often what is being accepted by the one and rejected by the other is that one equals three. The believer argues that God has said it, therefore it must be true; the rejecter argues it cannot be true, therefore God has not said it. A learned non-Catholic divine, being asked if he believed in the Trinity, answered, "I must confess that  the arithmetical aspect of the Deity does not greatly interest me"; and if the learned can think that there is some question of arithmetic involved, the ordinary person can hardly be expected to know any better.

the arithmetical aspect of the Deity does not greatly interest me"; and if the learned can think that there is some question of arithmetic involved, the ordinary person can hardly be expected to know any better.

(i) Importance of the doctrine of the Trinity

Consider what happens when a believer in the doctrine is suddenly called upon to explain it — and note that unless he is forced to, he will not talk about it at all: there is no likelihood of his being so much in love with the principal doctrine of his Faith that he will want to tell people about it. Anyhow, here he is: he has been challenged, and must say something. The dialogue runs something like this:

Believer: "Well, you see, there are three persons in one nature."

Questioner: "Tell me more."

Believer: "Well, there is God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit."

Questioner: "Ah, I see, three gods."

Believer (shocked): "Oh, no! Only one God."

Questioner: "But you said three: you called the Father God, which is one; and you called the Son God, which makes two; and you called the Holy Spirit God, which makes three."

Here the dialogue form breaks down. From the believer's mouth there emerges what can only be called a soup of words, sentences that begin and do not end, words that change into something else halfway. This goes on for a longer or shorter time. But finally there comes something like: "Thus, you see, three is one and one is three." The questioner not unnaturally retorts that three is not one nor one three. Then comes the believer's great moment. With his eyes fairly gleaming he cries: "Ah, that is the mystery. You have to have faith."

Now it is true that the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity is a mystery, and that we can know it only by faith. But what we have just been hearing is not the mystery of the Trinity; it is not the mystery of anything, it is wretched nonsense. It may be heroic faith to believe it, like the man who

Wished there were four of 'em

That he might believe more of 'em

or it may be total intellectual unconcern - God has revealed certain things about Himself, we accept the fact that He has done so, but find in ourselves no particular inclination to follow it up. God has told us that He is three persons in one Divine nature, and we say "Quite so", and proceed to think of other matters - last week's Retreat or next week's Confession or Lent or Lourdes or the Church's social teaching or foreign missions. All these are vital things, but compared with God Himself, they are as nothing: and the Trinity is God Himself. These other things must be thought about, but to think about them exclusively and about the Trinity not at all is plain folly. And not only folly, but a kind of insensitiveness, almost a callousness, to the love of God. For the doctrine of the Trinity is the inner, the innermost, life of God, His profoundest secret. He did not have to reveal it to us. We could have been saved without knowing that ultimate truth. In the strictest sense it is His business, not ours. He revealed it to us because He loves men and so wants not only to be served by them but truly known. The revelation of the Trinity was in one sense an even more certain proof than Calvary that God loves mankind. To accept it politely and think no more of it is an insensitiveness beyond comprehension in those who quite certainly love God: as many certainly do who could give no better statement of the doctrine than the believer in the dialogue we have just been considering.

How did we reach this curious travesty of the supreme truth about God? The short statement of the doctrine is, as we have heard all our lives, that there are three persons in one nature. But if we attach no meaning to the word person, and no meaning to the word nature, then both the nouns have dropped out of our definition, and we are left only with the numbers three and one, and get along as best we can with these. Let us agree that there may be more in the mind of the believer than he manages to get said: but the things that do get said give a pretty strong impression that his notion of the Trinity is simply a travesty. It does him no positive harm provided he does not look at it too closely; but it sheds no light in his own soul: and his statement of it, when he is driven to make a statement, might very well extinguish such flickering as there may be in others. The Catholic whose faith is wavering might well have it blown out altogether by such an explanation of the Trinity as some fellow Catholic of stronger faith might feel moved to give: and no one coming fresh to the study of God would be much encouraged.

(ii) "Person" and "Nature"

Let us come now to a consideration of the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity to see what light there is in it for us, being utterly confident that had there been no light for us, God would not have revealed it to us. There would be a rather horrible note of mockery in telling us something of which we can make nothing. The doctrine may be set out in four statements:

"I think the criticism which we find it most uncomfortable to meet ..."

... is when they tell us that the Catholic Church is all right when you consider it a priori, on paper, as a system, but when you look at its actual record in history you do not find its effects on human life the kind of effects which you would expect a supernatural institution to have. The world, to be sure, has advanced a great deal since the times of our Lord. Slavery has given place to freedom, savagery to kindness, selfishness to philanthropy; men are no longer (in the more favoured countries) executed for slight offences, or tortured when they refuse to give evidence, or killed in duels; some attempt is made, at any rate, to give working men decent wages, and rescue them and their families from destitution; and in a thousand other ways it is possible to show that the world has become a more comfortable place to live in. But how much, we are asked, has all this to do with Christianity, or at any rate with the Catholic Church? Is it not true that the improvements which have been made in the condition of human living have been made, for the most part, without any effort of sympathy on the part of Catholics, and sometimes in the teeth of theIr opposition? And if that is so, how can we claim that the Catholic Church, as we find the Catholic Church in history, is the Church which our Lord referred to in his parables? How strange that the leaven which has leavened the world has not, noticeably at any rate, proceeded from her!

The answer to that kind of objection is not an easy one, and I think it is rather a humiliating one. Perhaps the simplest way to put it is this. During the period between the Ascension and the Reformation, that charge is not true. During the period between the Reformation and the French Revolution that charge is true, but it was not our fault; in great measure at least it was not our fault. In our own day, the situation has grown so desperately complicated that It defies analysis. What seems to emerge from it is that under modern conditions we Catholics ought, more than ever, to be taking the lead in enlightening the conscience of the world; that, largely, we are not doing it, and it is our fault that we are not doing it; and moreover, that in proportion as we do succeed in our efforts, we shall not be given any credit for it; we shall be cried down as much as ever by the prophets of materialistic humanitarianism for not going about it in a different and more wholehearted way.

— Monsignor Ronald A. Knox, from "The Church and Human Progress", a chapter from In Soft Garments: Classic Catholic Apologetics.

May 26, 2011

I'll see your outrage and double it

During his NFL career (which he is currently re-starting), Tiki Barber took many a hard hit from huge defensive linemen and punishing linebackers, but I don't know if he ever had a foot shoved down his throat and into his stomach. Alas, he accomplished that on his own, albeit metaphorically:

Tiki Barber hasn't taken the football field yet in his comeback, but he's already taking hits for making an analogy to Holocaust victim Anne Frank.

The former New York Giants running back has been criticized in local media for making the analogy during an interview in this week's Sports Illustrated. At one point in the article, Barber describes going into hiding with his girlfriend after his well-publicized breakup with his then-pregnant wife. Barber and his girlfriend ended up in the attic of the home of the player's agent, Mark Lepselter.

"Lep's Jewish," Barber told Sports Illustrated. "And it was like a reverse Anne Frank thing."

Lepselter came to his client's defense Thursday.

"In a world where nothing surprises me, where things get completely blown out of proportion, this only adds to the list," Lepselter told ESPNNewYork.com. "[Tiki] was shedding light on going back to that time when he was literally trapped, so to speak, in my attic for a week. Nothing more, nothing less.

"Let me remind all those who want to make this more than it is: Tiki was a guest of [president] Shimon Peres in Israel five years ago."

Abraham H. Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, described Barber's comment as "outrageous and perverse."

Yes, it was outrageous. Absolutely. Flippant and glib, I think, but definitely the wrong historical event to draw upon for analogies. But it doesn't say anything good that while there is an understandable outcry about Barber's comments, there isn't any mention of anger or disgust about this: "going into hiding with his girlfriend after his well-publicized breakup with his then-pregnant wife." Comparing oneself to Anne Frank when you aren't in any danger is outrageous. But comparing yourself to Anne Frank when you are hiding with your girlfriend from your pregnant (with twins) wife? That certainly is perverse.

By the way, give the Orwellian Spin of the Day Award to the agent for saying, "literally trapped, so to speak." Uh, was he literally trapped? "Uh, yeah, so to speak." So he wasn't really trapped? "Um, no, not literally, but in a...um... non-literal kinda way...yeah...no...I gotta run." Good idea.

I just found this New York Post piece from April 2010:

Ex-Giants superstar Tiki Barber has dumped his 8-months-pregnant wife, Ginny, for sexy former NBC intern Traci Lynn Johnson, sources told The Post last night.

The football star-turned-"Today" show-correspondent left his wife of 11 years, Ginny, for the 23-year-old blonde, who also worked at 30 Rock, the sources said.

Ginny, who is expecting twins, found out about the relationship late last year, after the run-around running back moved out of their Upper East Side home. ...

The affair is particularly stunning in light of Barber's long-standing disdain for his philandering father.

"I don't give a [bleep] that the relationship didn't work," he said of his parents' split in a 2004 Post interview. "Not only did he abandon her, I felt like he abandoned us for a lot of our lives. I have a hard time forgiving that."

Barber's confidants were shocked. ...

In his 2007 memoir, "Tiki: My Life in the Game and Beyond," Barber described the example he wanted to set for his kids.

"I want to be an honorable man, because that's what I want them both to be," he wrote, noting, "My family is everything to me."

I don't say this often: I'm a 100% with Foxman on this one. Ugh.

The Argument from Contingency...

... as summarized by the great apologist Frank Sheed:

If we consider the universe, we find that everything in it bears this mark, that it does exist but might very well not have existed. We ourselves exist, but we would not have existed if a man and a woman had not met and mated. The same mark can be found upon everything. A particular valley exists because a stream of water took that way down, perhaps

because the ice melted up there. If the melting ice had not been there, there would have been no valley. And so with all the things of our experience. They exist, but they would not have existed if some other thing had not been what it was or done what it did.

because the ice melted up there. If the melting ice had not been there, there would have been no valley. And so with all the things of our experience. They exist, but they would not have existed if some other thing had not been what it was or done what it did.

None of these things, therefore, is the explanation of its own existence or the source of its own existence. In other words, their existence is contingent upon something else. Each things possesses existence, and can pass on existence; but it did not originate its existence. It is essentially a receiver of existence. Now it is impossible to conceive of a universe consisting exclusively of contingent beings, that is, of beings which are only receivers of existence and not originators. The reader who is taking his role as explorer seriously might very well stop reading at this point and let his mind make for itself the effort to conceive a condition in which nothing should exist save receivers of existence.

Anyone who has taken this suggestion seriously and pondered the matter for himself before reading on, will have seen that the thing is a contradiction in terms and therefore an impossibility. If nothing exists save beings that receive their existence, how does anything exist at all? Where do they receive their existence from? In such a system made up exclusively of receivers, one being may have got it from another, and that from still another, but how did existence get into the system at all? Even if you tell yourself that this system contains an infinite number of receivers of existence, you still have not accounted for existence. Even an infinite number of beings, if no one of these is the source of its own existence, will not account for existence.

Thus we are driven to see that the beings of our experience, the contingent beings, could not exist at all unless there is also a being which differs from them by possessing existence in its own right. It does not have to receive existence; it simply has existence. It is not contingent: it simply is. This is the Being that we call God.

All this may seem very simple and matter of course, but in reality we have arrived at a truth of inexhaustible profundity and of inexhaustible fertility in giving birth to other truths.

From Theology and Sanity (pp. 54-55), available in both paperback and electronic book formats.

Author of "The Spirit of Father Damien" to give presentation at Flanders House (NYC) on June 8th

From Rose Trabbic, publicist for Ignatius Press:

Ignatius Press author Jan De Volder will be giving a presentation about his new book, The Spirit of Father Damien: The Leper Priest—A Saint for Our Times, on Wednesday, June 8 at 6:30 pm ET. The event will take place at the Flanders House in New York  (www.flandershouse.org) and will be followed by a reception. Guests must by RSVP by June 2 to: rsvp6@flandershouse.org.

(www.flandershouse.org) and will be followed by a reception. Guests must by RSVP by June 2 to: rsvp6@flandershouse.org.

For more information, please see the invitation below.

Flanders House requests the pleasure of your and your guest's company at the book launch of Jan De Volder's The Spirit of Father Damien:

Wednesday, June 8 | 6.30 PM

Flanders House

The New York Times Building

620 Eighth Avenue, 44th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Jan De Volder lives and works in Antwerp, Belgium. He has an MA in Romance Literature and Languages and a PhD in Social and Religious History. He is editor of the Flemish Catholic weekly Tertio. Each week he writes articles on religion, culture, politics, and society. As such, he often comments on church and social issues on radio and television. He is an active member of the Community of Sant'Egidio.

Please confirm your and your guest's attendance by providing us with both full names by Thursday, June 2: rsvp6@flandershouse.org

Flanders House

The New York Times Building

620 Eighth Avenue, 44th Floor

New York, NY 10018

You can read the Introduction to The Spirit of Father Damien on Ignatius Insight.

Listen to recent interviews with Fr. Andrew Apostli, T. M. Doran

Fr. Andrew Apostoli, C.F.R., author of Fatima For Today: The Urgent Marian Message of Hope, was recently a guest on the The Bishop's Radio Hour, hosted by Bob Dunning on Immaculate Heart Radio (Sacramento, 1620 AM):

Fr. Apostoli was also a guest on May 18th on "Kresta In the Afternoon" on Ave Maria Radio (the interview starts at the eight minute mark):

Novelist T. M. Doran, author of Toward the Gleam, was also on "Kresta in the Afternoon" on the same day (interview begins around the 6 minutes, 30 second mark):

For more about Toward the Gleam, including a lengthy excerpt, visit the book's website. For more interviews with T. M. Doran about his novel, visit the interview page on the same site.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers