Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 286

September 16, 2011

Teresa Tomeo's "Extreme Makeover" addresses self-image, false "freedoms", authentic femininity

Teresa Tomeo, who hosts a syndicated talk show on EWTN and is the author of the book, Extreme Makeover: Women Transformed by Christ, Not Conformed to the Culture (Ignatius Press; available in October 2011), was recently interviewed by Catholic News Service about how

women are pressured into being many different things to different people: a powerhouse professional, a flawless wife and beautiful woman.

She said much in society is contradictory: "We have all these advancements and yet we're more objectified than ever."

There's a kind of "split personality" in the media, she said, when a newspaper or newscast reports on studies showing how influential media are on an audience, especially children, or studies showing ways women are still objectified.

"And then they turn around and promote sex at 2 in the afternoon in a soap opera or a commercial," she said.

Women's self-image is often distorted because of too much emphasis on youth, physical beauty and sexuality, she said.

Add to the mix the modern-day "freedoms" of contraception, abortion, and sex outside of marriage and women end up being not more free or equal "but more in bondage, and you don't realize it when you're accepting it."

"You have to go through your own crisis" to see there is another way, she said.

In her book, published by Ignatius Press, Tomeo details the personal crises she weathered -- an eating disorder, a frenetic work ethic and a crumbling marriage. She had been living distant from God, she said, and just accepted the current culture's stereotypes wholesale.

Read the entire piece. Tomeo also spoke with "Rome Reports" about the book:

September 15, 2011

Dr. Ed Peters remarks on the Bp. Zurek-Fr. Pavone dispute ...

... on his "In the Light of the Law" blog. Highly recommended to anyone looking for a careful, knowledgeable guide to the various (and sometimes complex) canonical issues involved.

For helpful background information on the story, see this post on the Catholic World Report blog by managing editor, Cate Harmon.

September 14, 2011

My list of ten "Books That Make Us Human"

I'm writing this in Boise, Idaho (90 degrees today!), where I will be giving a talk to a group of priests midday, before heading back home in the evening. I see that the gracious and never-sleeping, ever-going, always-posting Brad Birzer (professor, historian, author, prog rock expert) has posted my list of "Books That Make Us Human" on the Imaginative Conservative blog, part of a symposium of sorts (here is a note by Brad explaining the criteria for the book choices). Here are my first three books:

1. The Bible. It is one of the first books I read (not cover-to-cover, at first, of course), and the first book I memorized passages from as a child. I cannot imagine trying to think about or comprehend the human condition without it. A few specific books within The Good Book that merit note: Genesis and Exodus, the Psalms and The Book of Wisdom, the Gospel of John, and Apostle Paul's Epistle to the Romans.

2. Confessions, by St. Augustine of Hippo. I've read it several times now, and I am always amazed by the depth of Augustine's thinking and emotions, as well as by the clarity and profundity of his expression.

3. Summa Theologica, by St. Thomas Aquinas. It would be a mistake to assume this seminal work of theology/philosophy is dry or merely didactic, because a careful and reflective reading reveals an understanding of man's origin, nature, and end that has rarely been rivaled.

Read the remaining seven. It was a tough list to narrow down to ten (and I actually list more than ten); there are many other deserving titles. What are some of your choices?

The Blessed Virgin Mary "has experienced every joy and pain imaginable"

On this day, the Memorial of Our Lady of Sorrows, a few reflections taken from an Advent piece I wrote several years ago:

"But," it might be objected, "what does Mary really know about sin and death? Didn't she escape both?" It's true that because she was immaculately conceived–a gift of God's grace–Mary was saved from sin. But because she is full of grace and in perfect union with her Son, Mary is able to see with utter clarity the human condition and the effect sin has had on the world and on mankind.

She truly rejoiced in God her Savior (Lk 1:47) because she knew what sin was, even while she remained untouched by its stain. And she stood at the foot of the Cross and experienced the heart-wrenching pain of seeing her Son and Savior die a death due to the sins of the world (cf. Lk 2:35).

So it is fitting and comforting that the mother of the Son of God prays for her sons and daughters at the hour of their deaths. The Mother of God, from whose faith and body the Redeemer was born, prays that men and women will have the faith to become true children of God, born of the Spirit. The Woman, who experienced the death of her Son, prays that they will die to themselves so that they will live to Christ (cf. Gal 2:20).

Some theologians have suggested that the Immaculate Conception was a doctrine meant to awaken the modern world to the fact that human perfection and salvation cannot come from technology, science, or ideology, but only by God's initiative, mercy, and grace. Modern man denies that he is a sinner in need of salvation. Contrast that to Paul, who exclaims that "it is a trustworthy statement, deserving full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, among whom I am foremost of all" (1Tim. 1:15).

The true disciple of Jesus Christ must admit his need and his inability to save himself. He is then invited to become a son of God by grace and through divine adoption. This is the incredible reality of deification–man sharing in the freely offered life of God. In the words of St. Hilary of Poitiers, "Everything that happened to Christ lets us know that, after the bath of water, the Holy Spirit swoops down upon us from high heaven and that, adopted by the Father's voice, we become sons of God" (CCC 537). ...

Mary has experienced every joy and pain imaginable. She clasped in wonder the newborn Christ in her weary arms. She held in sorrow the bloody body of that same Son, grown and violently killed. She stands in heaven and patiently waits for her sons and daughters to come home.

What if Jesus had not died on the Cross?

That question was put to then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger by Peter Seewald in the interview that became the wonderful book, God and the World: A Conversation with Peter Seewald (Ignatius Press, 2002):

Seewald: What would actually have happened if Christ had not appeared and if he had not died on the tree of the Cross? Would the world long since have come to ruin without him?

Cardinal Ratzinger: That we cannot say. Yet we can say that man would have no access to God. He would then only be able to relate to God in occasional fragmentary attempts. And, in the end, he would not know who or what God actually is.

Something of the light of God shines through in the great religions of the world, of course, and yet they remain a matter of fragments and questions. But if the question about God finds no answer, if the road to him is blocked, if there is no forgiveness, which can only come with the authority of God himself, then human life is nothing but a meaningless experiment. Thus, God himself has parted the clouds at a certain point. He has turned on the light and has shown us the way that is the truth, that makes it possible for us to live and that is life itself.

Seewald: Someone like Jesus inevitably attracts an enormous amount of attention and would be bound to offend any society. At the time of his appearance, the prophet from Nazareth was not only cheered, but also mocked and persecuted. The representatives of the established order saw in Jesus' teaching and his person a serious threat to their power, and Pharisees and high priests began to seek to take his life. At the same time, the Passion was obviously part and parcel of his message, since Christ himself began to prepare his disciples for his suffering and death. In two days, he declared at the beginning of the feast of Passover, "the Son of Man will be betrayed and crucified."

Cardinal Ratzinger: Jesus is adjusting the ideas of the disciples to the fact that the Messiah is not appearing as the Savior or the glorious powerful hero to restore the renown of Israel as a powerful state, as of old. He doesn't even call himself Messiah, but Son of Man. His way, quite to the contrary, lies in powerlessness and in suffering death, betrayed to the heathen, as he says, and brought by the heathen to the Cross. The disciples would have to learn that the kingdom of God comes into the world in that way, and in no other.

Read more of the interview on Ignatius Insight:

SSPX given a "doctrinal preamble" by Vatican; assent required for reconciliation

From Cate Harmon on the Catholic World Report blog:

At a meeting today with Vatican officials, including the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's Cardinal William Levada, leaders of the Society of St. Pius X were given a "doctrinal preamble" detailing principles of the Catholic faith to which assent must be given in order for the traditionalist group to achieve reconciliation with the Catholic Church.

In addition, the leaders discussed what a "canonical solution" to the SSPX fissure might look like, should the group accept the doctrinal statement.

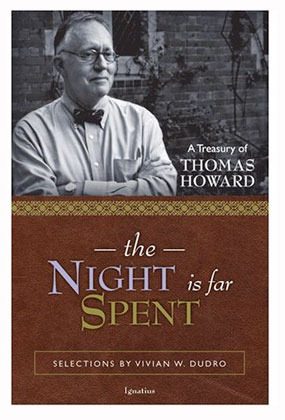

Thomas Howard on the Image and the Mystery of the Cross

From the essay, "The Image of the Cross", taken from the collection, The Night Is Far Spent: A Treasury of Thomas Howard (Ignatius Press, 2007):

At the center of Christian vision and imagery stands a great and enigmatic sign, the sign of the Cross. Like the brass serpent held aloft on a pole by Moses in the desert, the Cross has drawn and fixed the gazes of men ever since it was  raised. It is there at the center of Christian vision because it is there at the center of the divine drama celebrated in that vision—the drama unfolded on the stage of our history in the sequence of Annunciation, Nativity, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension. And, like all these mighty mysteries in this sequence, the Cross defies all our efforts to grasp its full significance, and all our attempts to respond adequately. Shall we approach in sackcloth or in festal garments? Shall we sing songs of penitence or of triumph? Shall we bring ashes or garlands?

raised. It is there at the center of Christian vision because it is there at the center of the divine drama celebrated in that vision—the drama unfolded on the stage of our history in the sequence of Annunciation, Nativity, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension. And, like all these mighty mysteries in this sequence, the Cross defies all our efforts to grasp its full significance, and all our attempts to respond adequately. Shall we approach in sackcloth or in festal garments? Shall we sing songs of penitence or of triumph? Shall we bring ashes or garlands?

The difficulty we mortal men have in the presence of the events that make up the Gospel is that, while the events themselves are straightforward enough for any peasant to understand (the angels appeared to shepherds), the significance of those events exhausts the efforts of the most sublime intellects to grasp them. The plain Gospel story is told, century after century, to peasants, children, and philosophers and calls forth adoration and faith from all alike. The stable, the Upper Room, the garden, the Cross, the tomb, and so forth: these are points in a tale that is plain enough for all of us. But these are also points on the frontier between the seen and the unseen, the historic and the eternal, the contingent and the unconditioned, and hence open out onto vistas where the divine immensities loom in all their terror and splendor.

For this reason, the Cross, which is a clear enough object, attracts the unceasing efforts of man's intellect and imagination and affection to respond in some manner fitting its significance. It is carried in procession with great pomp in Rome and hangs on a string around the neck of an Irish farmer. It glimmers from a plaque next to a child's crib and shines from the pages of Aquinas, Calvin, and Barth. It is hailed in sorrowful chants ("O vos omnes ... videte si est dolor sicut dolor mei") and in hymns of contrition ("When I survey the wondrous Cross") and of triumph ("Onward, Christian soldiers"). There are gold crosses, plastic crosses, wooden crosses, jeweled crosses, and stone crosses. There are huge crosses towering in the Alps and the Andes and tiny crosses on dashboards and shelves. There are crosses on spires and crosses on gravestones. There are Celtic crosses, Crusaders' crosses, crosses of Saint Anne, and Coptic crosses. There is the bare cross, the crucifix, and the Christus Rex (Christ crowned and in royal robes on the Cross). And of course there is no counting the frescoes, mosaics, icons, and oil paintings that have for their subject the crucifixion scene.

What can we say of the Cross—this mystery celebrated, extolled, lauded, adored, and followed for two thousand years? Nothing new, certainly.

For Protestant imagination, the focus has always been not so much on the image of the Cross as on the work on the Cross: the work of atonement wrought by Christ there for us, from which proceed our redemption and the forgiveness of our sins; and the work of the Cross in the heart of the Christian who embraces it, dealing death to the Adam in us with all of his sin, and opening the way to new life. Hence, in this imagination, the Cross is thought about, and spoken about, and preached and written about, but not much depicted. The idea here is that if you externalize and visualize your representations of the Cross, you will get: to looking at the thing you have made and miss the significance behind it. It is a caution that has been alive in the Church from the beginning, and one that will need to be kept alive until we pass from faith to sight in the final triumph.

But whether Christians' meditations on the Cross have been accompanied by any sort of visual representation or not, all Christians have known that this Cross is right at the center for them. The story that they call Good News anticipates and moves straight toward the Cross from the outset; nay, there is shed blood and the promise of bruising some thousands of years before that story itself unfolds. And there is no victorious denouement to the Gospel story (what Professor Tolkien calls the "eucatastrophe"—the good outcome) in Resurrection and Ascension without the Cross first. There is no question of eternal life for us without our going down into crucifixion and burial with Christ, like seeds of wheat planted in the ground before the crop and harvest. There is no putting away of sin by any method other than crucifixion. There is no doing away with the debt piled against us unless it is nailed to the Cross.

Christians see themselves, then, as a people under the sign of the Cross. It is the sign of their salvation; it is their ensign, their banner, their cover, their plea, and their glory. It is an interesting datum in the history of the Church that there has never been defined for Christian orthodoxy one universally satisfactory doctrine as to what happened at the Cross. All creeds and councils agree that at the Cross Christ effected our salvation, and that our debt was, somehow, paid there (paid to whom? God? the Devil?), and that we have forgiveness of sins and eternal life on the basis of that event. But the fullness of the transaction remains a mystery. The words offering, sacrifice, substitution, atonement, example, and victory all crowd around the Cross, but no one can get all the pieces fitted together, any more than they can fit together the pieces in the other events of the Gospel story. We affirm these events and the dogmas that define them; we confess them, we believe them, we bow to them, we preach them, and we sing of them. But we cannot explain them.

This, surely, is at least part of the glory of Christian Faith: it speeds like a light between two poles, the one pole being the plain events in the Gospel story, the other being the great mysteries evinced in the events. For Christians, the very act of contemplating the events and the mysteries is nourishing and gladdening. For two thousand years now, peasants and sages have focused on the few simple events of the Gospel in their meditations; but no one has come near to exhausting it.

Related on Ignatius Insight:

• The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Cross--For Us | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Cross and The Holocaust | Regis Martin

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

September 13, 2011

Possessed of Both Reason and Revelation: Revisiting Regensburg

Possessed of Both Reason and Revelation: Revisiting Regensburg | Brian Jones, MA | Ignatius Insight | September 13, 2011

On September 12, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI gave an address at University of Regensburg, where he was once a distinguished professor and scholar. In the days and weeks that followed his lecture, outcries began to surface, and many commentators misinterpreted not only what the pope actually said, but also missed the heart of the lecture. Quite a few felt (notice that I said "felt" and not "thought") that the pope negatively criticized Islam, and this was clearly seen in the riots that broke out in some Muslim countries. Other commentators (such as Fr. James V. Schall, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, George Weigel, and C.S. Morrisey) noted how greatly the message of the Holy Father was distorted and misunderstood, especially by many in the Western world.

Although Benedict did discuss a few issues regarding Islam, this is not his main focus. His reflections were meant to challenge us to ask the most basic and fundamental questions about faith and reason: How are we to understand the two: as united, or as entities that must be separated? Is reason more itself with or without the aid of knowledge outside of itself? The great inheritance of the Catholic intellectual tradition reveals that faith and reason can never be separated, but must be harmoniously united so as to uphold the full dignity of each.

According to Benedict, if faith and reason are mutually exclusive, then they become distorted and susceptible to a widespread confusion about their true purpose and nature. By establishing a correct understanding of faith and reason (along with their proper integration), Benedict gave the world "an interreligious and ecumenical vocabulary by which Muslims, Jews, Christians, adherents of other world religions, and non-believers can engage in genuine conversation." [1] In his book, The Nature and Mission of Theology, the then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger said that men are capable of reciprocal comprehension in truth so that "the greater their inner contact with the one reality which unites them, namely, the truth, the greater their capacity to meet on common ground." [2] Without this understanding, dialogue would merely be spoken on "deaf ears."

This essay will elaborate upon this ever-present dismantling of the unity of faith and reason, by first examining the idea of God as Logos (Reason) versus the idea of God as purely "will," and then explain the consequences of separating God from reason, what Benedict calls the "dehellenization of Christianity." If man is capable of seeing why this synthesis of faith and reason is so vital for every culture, then their proper reconciliation can be achieved. This achievement will also enable faith and reason to remain intact, and prevent politics from becoming that science most proper to man, namely, metaphysics.

Postcards from the Planets Confusion and Dissent

First, from Fr. Richard McBrien, whose September 12th column in the National "Catholic" Reporter takes a mostly mundane gander at a recent study on the "state of Catholic parishes" produced by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) at Georgetown—until McBrien tries to awkwardly interject his support for priestettes into the stats:

Staffing of parishes yields some of the most compelling data. The estimated number of lay ecclesial ministers (that is, those who are paid and who work at least 20 hours per week) is approximately 38,000, or 2.1 percent per parish. Fourteen percent of these are vowed religious, while 86 percent are laypersons.

Overall, 80 percent are female–a statistic that has remained steady for many years and which makes the continued alienation of Catholic women a serious and growing pastoral problem.

The priest who sent me the link wryly notes: "I think we're supposed to acknowledge that women should be ordained so they're not alienated. Oh, wait, they are the overwhelming number of people working in 'lay ministries' which proves that they are alienated from the church. Oh, wait, that can't be right....now I am confused." Of course, it's McBrien who is confused, as he apparently thinks that 80% somehow indicates a minority. Of course, if 100% were women, then McBrien wouldn't be a priest. Hmmm.

The second postcard is from 84-year-old Adele Jones, writing on www.MySanAntonio.com about becoming something she can't become:

Today, in a beautiful ceremony in Falls Church, Va., I will be ordained a Roman Catholic woman priest.

Bishop Bridget Mary Meehan will be the ordaining bishop.

I realize the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church does not recognize my ordination into the all-male priesthood.

Since the Catholic Church will not let the ceremony take place in a Catholic setting, it will be held at the First Christian Church.

We'll use the same ordination rites that the Catholic Church uses for men.

My two sons and several friends will be there. I will be the first woman in San Antonio and in Texas to be ordained as a Roman Catholic woman priest. And I will be the oldest at age 84.

More than a year ago, the pope approved a new church law that called the ordination of women as priests a "grave crime."

Hey, it's the Three D's of Dissent, a veritable hat trick of shame: delusional, disingenuous, and damning. But Jones at least provides further evidence that my use of the term "priestette" is completely accurate, even if deemed "intolerant" and "mean-spirited" by those who loathe the Magisterium and the authentic teachings of the Church. As I explained on this blog nearly a year ago:

In fact, I came up with the term "priestette" (I'm not aware of prior use, but may have missed it; as best I can tell, my first use of it was in a blog post titled, "PRIESTETTES! PRIESTETTES! GET YOUR PRIESTETTES HERE!", posted on February 10/2003, on the Envoy Encore blog) precisely because it is an accurate term. Consider that the suffix "-ette" can mean or imply the following:

• A smaller form of something. And, indeed, the "ordination" of women as Catholic priests is a small attempt to be or accomplish something that cannot actually exist.

• The female equivalent of something. Ditto. Fairly self-evident.

• An imitation or substitute of something. Bingo! This is actually the primary focus of the term "priestette"--the imitative quality that speaks to a lack of knowledge, or humility, or maturity. Or all three, as is often the case.

And, from the same post, a review of the inherently illogical nature of the priestette movement:

• The priestette's demand that their "ordinations" be recognized by the Church and they be accepted as Catholic priests. Put another way, they want the blessing and backing of the Church and her authority.

• When excommunicated for knowingly violating Church law in a grave manner, said preistettes brazenly "reject" the law and acts of the Church.

• They say their conscience is supreme without qualification, which is directly contrary to clear Church teaching, which describes their position as a "mistaken notion of autonomy of conscience" and a "rejection of the Church's authority and her teaching" (CCC, par. 1792; see this post for much more).

• If their conscience is supreme, without qualification, it logically must have greater authority than the Church, which means 1) they have no need for the Church (so why do they seek the Church's approval?) and/or 2) the Church's authority is seriously flawed, even morally bankrupt, which also begs the question: why bother to be recognized and accepted by such an institution?

• Put simply, these priestettes go on and on about their desire and need to be a Catholic priest, yet always demean and even denounce the authority upon which the priesthood rests. If they can indeed "reject" Magisterial authority, that same authority is, logically, powerless to ordain them in any real and meaningful way. This is akin to Dan Brown's claim that Jesus was a simple carpenter who had, by virtue of some unknown quality, power over his goddess wife, Mary Magdalene. Right. And I have a bridge in southern Utah that you should buy.

St. John Chrysostom, the "Doctor Eucharisticus" and "a second Paul"

Back in 2007, which marked the 16th centenary of the death of St John Chrysostom—whose feast is celebrated today in the West (it is celebrated on November 13th in the East)—Pope Benedict XVI gave two general audiences and wrote a fairly lengthy letter about the great Eastern Father and Doctor. In the first general audience, given on September 19, 2007, Benedict presented an overview of Chrysostom's life and work, stating:

Chrysostom is among the most prolific of the Fathers: 17 treatises, more than 700 authentic homilies, commentaries on Matthew and on Paul (Letters to the Romans, Corinthians, Ephesians and Hebrews) and 241 letters are extant. He was not a speculative theologian.

Nevertheless, he passed on the Church's tradition and reliable doctrine in an age of theological controversies, sparked above all by Arianism or, in other words, the denial of Christ's divinity. He is therefore a trustworthy witness of the dogmatic development achieved by the Church from the  fourth to the fifth centuries.

fourth to the fifth centuries.

His is a perfectly pastoral theology in which there is constant concern for consistency between thought expressed via words and existential experience. It is this in particular that forms the main theme of the splendid catecheses with which he prepared catechumens to receive Baptism.

On approaching death, he wrote that the value of the human being lies in "exact knowledge of true doctrine and in rectitude of life" (Letter from Exile). Both these things, knowledge of truth and rectitude of life, go hand in hand: knowledge has to be expressed in life. All his discourses aimed to develop in the faithful the use of intelligence, of true reason, in order to understand and to put into practice the moral and spiritual requirements of faith.

In the second audience, given a week later on September 26, 2007, the Holy Father said:

It is said of John Chrysostom that when he was seated upon the throne of the New Rome, that is, Constantinople, God caused him to be seen as a second Paul, a doctor of the Universe. Indeed, there is in Chrysostom a substantial unity of thought and action, in Antioch as in Constantinople. It is only the role and situations that change. In his commentary on Genesis, in meditating on God's eight acts in the sequence of six days, Chrysostom desired to restore the faithful from the creation to the Creator: "It is a great good", he said, "to know the creature from the Creator", He shows us the beauty of the creation and God's transparency in his creation, which thus becomes, as it were, a "ladder" to ascend to God in order to know him. To this first step, however, is added a second: this God Creator is also the God of indulgence (synkatabasis). We are weak in "climbing", our eyes grow dim. Thus, God becomes an indulgent God who sends to fallen man, foreign man, a letter, Sacred Scripture, so that the creation and Scripture may complete each another. We can decipher creation in the light of Scripture, the letter that God has given to us. God is called a "tender father" (philostorgios) (ibid.), a healer of souls (Homily on Genesis, 40, 3), a mother (ibid.) and an affectionate friend (On Providence 8, 11-12). But in addition to this second step - first, the creation as a "ladder" to God, and then, the indulgence of God through a letter which he has given to us, Sacred Scripture - there is a third step. God does not only give us a letter: ultimately, he himself comes down to us, he takes flesh, becomes truly "God-with-us", our brother until his death on a Cross. And to these three steps - God is visible in creation, God gives us a letter, God descends and becomes one of us - a fourth is added at the end. In the Christian's life and action, the vital and dynamic principle is the Holy Spirit (Pneuma) who transforms the realities of the world. God enters our very existence through the Holy Spirit and transforms us from within our hearts.

Against this background, in Constantinople itself, John proposed in his continuing Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles the model of the primitive Church (Acts 4: 32-37) as a pattern for society, developing a social "utopia" (almost an "ideal city"). In fact, it was a question of giving the city a soul and a Christian face. In other words, Chrysostom realized that it is not enough to give alms, to help the poor sporadically, but it is necessary to create a new structure, a new model of society; a model based on the outlook of the New Testament. It was this new society that was revealed in the newborn Church. John Chrysostom thus truly became one of the great Fathers of the Church's social doctrine: the old idea of the Greek "polis" gave way to the new idea of a city inspired by Christian faith. With Paul (cf. I Cor 8: 11), Chrysostom upheld the primacy of the individual Christian, of the person as such, even of the slave and the poor person.

In his letter presented on August 10, 2007, Benedict reflected in more detail on various aspects of Chrysostom's thought, including his understanding of the intimate relationship between liturgy, Eucharist, and ecclesial communion—a topic of great interest to the Holy Father:

John held that the Church's unity was founded on Christ, the Divine Word who with his Incarnation was united to the Church as the head is united to the body. "Where the head is, there also is the body", and that is why "there is no separation between the head and the body". He had comprehended that in the Incarnation the Divine Word not only became man but also united himself to us, making us his body: "Since it did not suffice for him to make himself a man to be scourged and killed, he united himself to us not only through faith but also de facto makes us his body". Commenting on the passage of the Letter of St Paul to the Ephesians: "In fact, he put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things for the Church which is his body, the fullness of him who is fully realized in all things", John explained that "it is as if the head were completed by the body, because the body is made up and formed of its various parts. His body is therefore composed by all. Thus, the head is completed and the body rendered perfect when we are all clustered closely together and united". John then concluded that Christ unites all the members of his Church with himself and with one another. Our faith in Christ requires us to work hard for an effective, sacramental union among the members of the Church, putting an end to all divisions.

For Chrysostom, the ecclesial unity that is brought about in Christ is attested to in a quite special way in the Eucharist. "Called "Doctor of the Eucharist' because of the vastness and depth of his teaching on the Most Holy Sacrament", he taught that the sacramental unity of the Eucharist constitutes the basis of ecclesial unity in and for Christ. "Of course, there are many things to keep us united. A table is prepared before all... all are offered the same drink, or, rather, not only the same drink but also the same cup. Our Father, desiring to lead us to tender affection, has also disposed this: that we drink from one cup, something that is befitting to an intense love". Reflecting on the words of St Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians, "The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ?", John commented: for the Apostle, therefore, "just as that body is united to Christ, so we are united to him through this bread". And even more clearly, in the light of the Apostle's subsequent words: "Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body", John argued: "What is bread? The Body of Christ. And what does it become when we eat it? The Body of Christ; not many bodies but one body. "Just as bread becomes one loaf although it is made of numerous grains of wheat..., so we too are united both with one another and with Christ.... Now, if we are nourished by the same loaf and all become the same thing, why do we not also show the same love, so as to become one in this dimension, too?"

Chrysostom's faith in the mystery of love that binds believers to Christ and to one another led him to experience profound veneration for the Eucharist, a veneration which he nourished in particular in the celebration of the Divine Liturgy. Indeed, one of the richest forms of the Eastern Liturgy bears his name: "The Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom". John understood that the Divine Liturgy places the believer spiritually between earthly life and the heavenly realities that have been promised by the Lord. He told Basil the Great of the reverential awe he felt in celebrating the sacred mysteries with these words: "When you see the immolated Lord lying on the altar and the priest who, standing, prays over the victim... can you still believe you are among men, that you are on earth? Are you not on the contrary suddenly transported to Heaven?". The sacred rites, John said, "are not only marvellous to see, but extraordinary because of the reverential awe they inspire. The priest who brings down the Holy Spirit stands there... he prays at length that the grace which descends on the sacrifice may illuminate the minds of all in that place and make them brighter than silver purified in the crucible. Who can spurn this venerable mystery?"

With great depth, Chrysostom developed his reflection on the effect of sacramental Communion in believers: "The Blood of Christ renews in us the image of our King, it produces an indescribable beauty and does not allow the nobility of our souls to be destroyed but ceaselessly waters and nourishes them". For this reason, John often and insistently urged the faithful to approach the Lord's altar in a dignified manner, "not with levity... not by habit or with formality", but with "sincerity and purity of spirit".

This same topic was addressed by Adrian Fortescue over a hundred years ago in his classic study,  The Greek Fathers: Their Lives and Writings (Ignatius Press, 2007; orig. 1908):

The Greek Fathers: Their Lives and Writings (Ignatius Press, 2007; orig. 1908):

Most of the Doctors of the Church have some one point of the faith of which they are the classic exponents: thus, Saint Athanasius is the Doctor of the Divinity of Christ, Saint Augustine is the "Mouth of the Church about Grace". By universal consent, Saint John Chrysostom is looked upon as the great defender of the holy Eucharist. He is the Doctor Eucharisticus. The Blessed Sacrament and the Real Presence are the subjects to which he turns most often; his writings on this question form a complete defence and exposition of the teaching of the Catholic Church about her most sacred inheritance. In his homilies On the Sixth Chapter of St John, he develops the ideas that our Lord has given us "Bread from Heaven, that he who eats it may not perish", that he himself is the "Living Bread that came down from heaven", that we are to "eat his Body and drink his Blood". "We must listen", says Chrysostom, "to this teaching with fear, because what we have to say today is very awful." He points to the altar and says, "Christ lies there sacrificed" "His Body lies before us", "That which is there in the chalice is what flowed from the side of Christ. What is the Bread? The Body of Christ." "Think, man, what sacrifice you receive in your hand [people took the Blessed Sacrament in their right hands], what altar you approach. Consider that you, dust and ashes, receive the Body and Blood of Christ." We not only see the Lord, "we take him in our hand, eat, our teeth pierce his flesh, that we may be closely joined to him." "What he did not allow on the cross, that he allows now at the Liturgy; for your sake he is broken, that all may receive." "It is not a man who causes the Offering to become the Body and Blood of Christ, but he himself who died for us. The priest stands there as his minister when he speaks the words, but the power and grace come from the Lord. This is my Body, he says. This word changes the Offering." "With confidence we receive your gift," he says in a prayer, "and because of your word we firmly believe that we receive a pledge of eternal life, because you say so, Lord, Son of God, who live with the Father in eternal life." (pp. 120-21).

Read the Foreword to Fortescue's book, written by Alcuin Reid, author of The Organic Development of the Liturgy:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers