Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 285

September 20, 2011

Brave New World Term of the Week: "Wrongful birth"

That term is used (aptly and damningly) by Billy Hallowell in a post on The Blaze about a Florida couple of who sued medical personnel for negligence because they allegedly were not given information they would have used in choosing to abort their now three-year-old son:

Many times, "wrongful death" is at the root cause of a lawsuit, but what happens in the case of a "wrongful birth" charge?

In West Palm Beach, Florida, a couple sued a doctor and an ultrasound technician for negligence. The two claimed that they would have aborted their son, who was born with no arms and only one leg, had they known about his disabilities beforehand.

The Palm Beach Post reports:

With the heartbreaking image of the small boy etched into their minds, jurors found Palm Beach Gardens obstetrician Dr. Marie Morel, OB/GYN Specialists of the Palm Beaches and Perinatal Specialists of the Palm Beaches responsible for not detecting the boy's horrific disabilities before he was born. The amount they awarded is half of the $9 million Ana Mejia and Rodolfo Santana were seeking for their son, Bryan.

The teary-eyed couple said they were overjoyed by the verdict. "I have no words," Mejia said in her native Spanish. Both agreed the award will make a huge difference in their son's life.

The jury of four men and two women found Morel 85 percent and an ultrasound technician 15 percent negligent for failing to properly read sonograms that would have alerted the couple of their son's disabilities before he was born in October 2008.

Attorney Mark Rosen, who represents Morel and the clinics, said they would appeal.

During a roughly two-week-long trial that ended Wednesday, Mejia and Santana claimed they would have never have brought Bryan into the world had they known about his horrific disabilities. Had Morel and technicians at OB/GYN Specialists of the Palm Beaches and Perinatal Specialists of the Palm Beaches properly administered two ultrasounds and seen he was missing three limbs, the West Palm Beach couple said they would have terminated the pregnancy.

A rather bizarre irony—if that's the right word for such a topic—is that the parents would have learned of their unborn son's condition if the mother had undergone amniocentesis (a procedure used in prenatal diagnosis of abnormalities and infections), but "rejected it because they were told that there was a 1 in 500 chance that removing amniotic fluid for testing would cause a miscarriage."

One commenter asks the perfectly logical question: "How great is that kid going to feel when he's old enough to learn his parents testified that had they known his true condition they would have killed him?" But it seems that in the Brave New World, regret is a one-way street, shame is never allowed in the room, and everyone must be protected from any possible ills, difficulties, or tragedies. Everyone, that is, except for the unborn. They are expendable—and if they aren't expendable, they are a burden. My prayer is that Mejia and Rodolfo Santana realize that their son, Bryan, is a gift and a blessing.

The Facebook page for...

... Teresa Tomeo's book, Extreme Makeover Women Transformed by Christ, Not Conformed to the Culture (October 2011, Ignatius Press), is now up and running. Check it out!

September 19, 2011

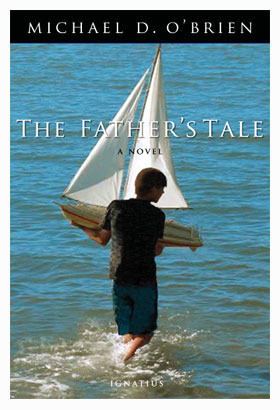

The opening pages of Michael D. O'Brien's "The Father's Tale: A Novel"

The Opening Pages of The Father's Tale: A Novel | Michael D. O'Brien | Ignatius Insight | September 20, 2011

Prologue

In late February of a year not long past, Dr. Irina Filippovna, a physician, was crossing the interminable expanse of the taiga on the Trans-Siberian Railroad and happened to be an unwilling witness to a singularly odd event. Though the coach in which she rode was third class, the seat hard, and her fellow passengers in foul or despairing moods due to the recent disruption of rail service by ecology protestors, she had planned to sleep away much of the  journey between Novosibirsk and Irkutsk. She had delivered a lecture on immunology at a medical institute in the former city and had hoped to disembark in the latter without undue trouble, and from there to make her way by bus and horse-drawn sleigh to her home village, where she maintained a small but necessary practice.

journey between Novosibirsk and Irkutsk. She had delivered a lecture on immunology at a medical institute in the former city and had hoped to disembark in the latter without undue trouble, and from there to make her way by bus and horse-drawn sleigh to her home village, where she maintained a small but necessary practice.

A handsome woman in her early forties, she was a widow with two sons to support. It was her custom to work with quiet determination to keep her life as simple as possible in order to bring what remained of her family through these times—the sociopolitical situation that now seemed more confused in some ways than it had been under the Communist regime. She had no love for anything that remained of the state's apparent omnipotence and its omnivorousness. Neither did she waste energy trying to understand the universe in other terms, for what might or might not lie beyond it could never be proved by science. She was in her own estimation a mother and a scientist. She often reminded herself that she had a good deal to be grateful for, especially her husband, whom she had loved as no other in her life, and her sons, who were now, if it might be expressed in this way, her very life. She was a person with a complicated but by no means unique personal history. An intellectual, though an impoverished one, she was neither political nor naïve. She entertained no sentimental illusions about her native land, yet in her soul she loved it fiercely, even as she doubted the existence of the soul.

It was her habit from time to time to adjust what she called her "Russian mask", the impenetrable neutral expression that projected an attitude of indifference and resignation, for it had a tendency to slip from her face at inopportune moments, usually those moments that she later dismissed as lapses "for humanitarian reasons". She was not indifferent and she was not resigned, but she had throughout her lifetime learned that it was best to hide the more personal elements of her character—and certainly before strangers. She was, she told herself, immune.

Thus, when from the corner of her eye she observed an unhappy man on the seat across the aisle, she noted the fact but attributed no significance to his presence. He appeared at first glance to be little different from several others in the coach, hunched as he was inside a dirty greatcoat, gaunt, haggard around the eyes, scowling, unshaven. He was about her age, perhaps a bit older. From time to time he lifted his left hand, favoring it as if it were sprained or burned, and pressed it to the frosted glass of the window beside him. Yes, a burn, she decided, assessing his wincing, the livid red disk on his palm, and the weeping blisters. She considered offering him an antibiotic salve from the medical bag at her feet but thought the better of it. His hair, dyed a glaringly artificial yellow, stood up in spikes, like that of a decadent American rock star. Not a few young Russians in the big cities affected the same appearance, but in a middle-aged man it was repulsive. She decided not to make contact. He might be drunk or a criminal, or both, but clearly he was a disturbed person, and the hundreds of versts yet to cross could all too easily degenerate into tribulation. The country was full of irrational, dispossessed people like him. Though she felt a momentary impulse to help, she warned herself against involvement and firmly put the poor fool from her thoughts.

Study reveals many "Da Vinci Code" fans are irrational, illogical, and scared of death

Our family is currently playing a game of "Pass the Flu from Me to You", and I'm "it" today, which partially explains the lack of posts (the other part of the equation is my current pet project: transcribing every episode of "Oprah" and "Dr. Phil", and then cross-referencing them for an online database).

But I couldn't let this article pass by without comment, not with a headline like this:

Belief in 'Da Vinci Code' Conspiracy May Ease Fear of Death [LiveScience.com, Sept. 16, 2011]

What seems at first glance to perhaps be something a silly bit of pseudo-academic nonsense is actually quite the opposite. The article is about a study—"The functional nature of conspiracy beliefs: Examining the underpinnings of belief in the Da Vinci Code conspiracy"—conducted by Anna Newheiser, a doctoral student in social psychology at Yale University, that examines why people fall for the conspiracy theories presented by Dan Brown in his best-selling, worst-written novel. But why use Brown's novel?

"The Da Vinci Code" was a good starting point, Newheiser said, because unlike other conspiracy believers, Da Vinci conspiracy believers are not marginalized as tin-foil hat types.

The researchers gathered college students who had read the book and conducted two studies. In the first, they asked 144 students to rate their agreement with Da Vinci conspiracy beliefs, such as "The church has burned witches and other 'heretics' to keep the truth about Jesus hidden." The students also filled out questionnaires about their religiosity, biblical knowledge, enjoyment of "The Da Vinci Code" novel or movie, and their fear of death. They also answered questions about New Age beliefs, such as "The whole cosmos is an unbroken living whole that modern man has lost contact with."

The study (which can be purchased online) revealed some findings that are more than a little interesting:

The students most likely to believe the conspiracies in Brown's novel were those who enjoyed the book the most, expressed the most New Age beliefs, and felt the most anxiety about dying. People who were religious, knowledgeable about the Bible and desiring of social approval, on the other hand, tended not to buy into the Da Vinci conspiracy.

Next, the researchers called 50 of the original students back and presented them with historical evidence that the Da Vinci conspiracy is false. They found that among the most religious participants, this counterevidence lessened the belief in the conspiracy. Nonreligious participants, however, did not budge.

The study, published online Sept. 7 in the journal Personality and Individual Differences, is preliminary, Newheiser said. But the finding that people with death anxiety are more likely to believe in the Da Vinci conspiracy jibes with the theory that conspiracies, as wacky as they can be, provide a sense of comfort to adherents.

Which indicates, among others things, that contra the "wisdom" of the day, religious adherents are more open to logic, arguments, and facts than are non-religious folks. But many of us religious zealots already knew that. So why are people attracted to conspiracy theories? The (partial) answer is rather commonsensical, but also revealing:

Conspiracy theories "can alleviate people's sense of loss of control by giving them a reason that things happen," Newheiser said. "In this case, it's particularly interesting because it might help people who are nonreligious or non-Christian to understand the events related to early Christian history."

Religious people have their own understanding of those events, Newheiser said, which may be why they were more easily persuaded that the Da Vinci conspiracy was false.

And much of "their own understanding of those events", as Sandra Miesel and I explained in detail in The Da Vinci Hoax: Exposing the Errors in The Da Vinci Code (Ignatius, 2004)., is based, again, in historical fact and logic. Yes, many Catholic scholars disagree about the details and meaning and such of this or that event, but they at least use what is known rather than what they wish had been the case. I've often said that one of the beautiful things about conspiracy theories is that the lack of evidence is almost always used as evidence. "Well, of course there's no evidence that Jesus was married!", exclaims Captain Conspiracy to his faithful band of merry-challenged followers, "Why? Because the Catholic Church got rid of the evidence!" Or, as Newheiser says, "There is past research showing that conspiracy beliefs don't really respond to counterevidence very well, because they're not based on logical arguments to begin with. Showing logical arguments against them doesn't change people's minds."

If nothing else, the attention being paid to Newheiser's study answers at least one question that Sandra and I put forth in the conclusion of our book, where we wrote that

The Da Vinci Code is a perfect post-modern myth, pulp fiction style. Occasionally clever and hip, it is never wise or insightful. Often cheesy, it is never artful. Seriously contrived, it is never believable or engaging. As Amy Welborn, another Da Vinci Code debunker, acidly notes, the characters are one-dimensional and the novel "is neither learned nor challenging – except to the reader's patience. Moreover, it's not really suspenseful, and the writing is shockingly banal, even for genre fiction. It's a pretentious, bigoted, tendentious mess."

So what is The Da Vinci Code. Is it just a fad? A one hit wonder? A novelty novel? Will people remember it in ten years? Will it matter? Is it worth writing an entire book in response to it? We think it is necessary, especially considering the impact and influence the novel has had and continues to have. Our hope is that readers will not only consider the truth about specific topics and issues, but will agree that Truth does exist and needs to be respected. "Truth, once it is rightly apprehended", wrote Ronald Knox, "has a compelling power over men's hearts; they must needs assert and defend what they know to be the truth, or they would lose their birthright as men."

So, yes, people will most likely remember it in ten years, for better or worse. Also see:

September 17, 2011

The lesson of the parable of the laborers in the vineyard

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, September 18, 2011 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Is 55:6-9

• Ps 145:2-3, 8-9, 17-18

• Phil 1:20c-24, 27a

• Mt 20:1-16a

Why did God make us? The Baltimore Catechism, in its first lesson, answers this question succinctly: "God made us to show forth His goodness and to share with us His everlasting happiness in heaven."

The opening paragraph of the Catechism of the Catholic Church addresses the same topic, saying, "God, infinitely perfect and blessed in himself, in a plan of sheer goodness freely created man to make him share in his own blessed life. … In his Son and through him, he invites men to become, in the Holy Spirit, his adopted children and thus heirs of his blessed life" (par 1).

It is a foundational belief of the Catholic faith that man was created because of the goodness of the loving Creator, and that God desires each of us to enter into the Kingdom of God and to live in perfect communion with Him. This relational, familial fact helps make sense of passages such as today's Gospel reading, the parable of the laborers in the vineyard.

This parable, of course, is not an economic treatise or a business blueprint. Like many parables, it draws upon the agrarian life that most first-century Jewish readers would know and understand intimately, and uses that familiar context to reveal something significant about the Kingdom proclaimed by Jesus throughout his public ministry. Matthew's Gospel was meant first and foremost for a Jewish audience and one of its main themes is that the kingdom of heaven is not meant exclusively for the Jews, but for Gentiles as well (cf., Matt. 12:18-21).

The parable has often been interpreted as referring to the Jews—the laborers chosen early in the day, that is, earlier in history—and to the Gentiles—the laborers chosen later in the day. Cyril of Alexandria wrote that "day" refers to "the whole age during which at different moments since the transgression of Adam [God] calls just individuals to their pious work, defining rewards for them for their actions." The laborers hired first are angry that the laborers hired late in the day receive the same way. This indeed seems unfair to us as long as we think in temporal, earthly terms. But, as today's reading from the prophet Isaiah reminds us, "For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways, says the LORD."

In fact, if man—whether Jew or Gentile—was judged by God on his own merits, he would fail to receive the wage of eternal life; that "wage" is actually a gift from God. As Saint Paul explained to the Ephesians, the Gentiles, who were once "without hope and without God in the world … have become near by the blood of Christ" (Eph 2:11-13).

Another interpretation, given by Saint John Chrysostom (as well as others), is that the vineyard refers to "the commandments of God, and the time of working refers to the present life." The workers are those who are "who have come forward at different ages and lived justly." Some are baptized as babies and remain in the family of God their entire lives, some enter the Church as adults, and some accept Christ on their deathbeds. Those who might think this is unfair fail to appreciate that the issue is not who is most deserving, but Who is most merciful. It is God who has pity on man, who invites him to work in the vineyard, and who pays the generous wage.

"The Church is a cultivated field, the tillage of God…" states the Catechism, "That land, like a choice vineyard, has been planted by the heavenly cultivator. Yet the true vine is Christ who gives life and fruitfulness to the branches, that is, to us, who through the Church remain in Christ, without whom we can do nothing" (CCC 755). This echoes what Paul explained to the Philippians in today's Epistle: fruitful labor is only possible in and through Jesus Christ.

That is how God shows forth His goodness and shares with us His everlasting happiness in heaven.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the September 21, 2008, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

St. Robert Bellarmine on Mary's Place in the Mystical Body of Christ

From the excellent essay, "Communion of Saints: St. Robert Bellarmine on the Mystical Body of Christ", by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.:

In a way, the most inspiring feature of Bellarmine's theology of the Mystical Body is the place which he assigns within it to the Blessed Mother of God: "The Head of the Catholic Church is Jesus Christ, and Mary is the neck which joins the Head to its Body." Because she has merited so well of God by her perfect conformity to His holy will, He has decreed that "all the gifts and all the graces which proceed from Christ as the Head should pass through Mary to the Body of the Church. Even the physical body has several members in its other parts—hands, shoulders, arms and feet—but only one head and one neck. So also the Church has many apostles, martyrs, confessors and virgins, but only one Head, the Son of God, and one bond between the Head and members, the Mother of God. By virtue of her transcendent merits before God, the Blessed Virgin stands closer than any other creature to the Head of the Mystical Body; it is no exaggeration to say that she unites the Head to the Body, and that therefore through her, before all others, flow the heavenly blessings from the Head, who is Christ, to us who are His members." [13]

The doctrine of the Mystical Body is anything but sterile theology. Among the practical consequences which St. Robert derives from our incorporation in Christ is the motive which it gives for the practice of fraternal charity. The Saints in heaven intercede for the souls in purgatory, he says, because they are both members of the same Body. The souls in purgatory intercede for each other because they are also members of one Body; the Saints and poor souls intercede for us because we are one Body with them, member of member; and we are moved to pray for each other on earth, to ask for favors from the Saints in heaven, and to pray for the souls in purgatory because "together with them we form one Church and one Body, united by the bond of the same charity in the Kingdom of Christ." [14]

Read the entire essay on Ignatius Insight:

September 16, 2011

Diocese of Spokane: Bp. Cupich does allow priests to participate in "40 Days for Life"

From Catherine Harmon, on the Catholic World Report blog:

In an effort to dispel rumors that have been circulating around the Internet this week (including here and here), the Diocese of Spokane has released a statement on its policy for clergy participation in pro-life efforts, specifically 40 Days for Life. In response to reports from several Spokane priests that their bishop had ordered them to refrain from praying in front of Planned Parenthood and from participating in 40 Days for Life vigils in particular, an online petition was launched by the coordinators of Spokane's 40 Days for Life campaign requesting that bishop reverse this position. More than 500 people signed the petition, including prominent pro-life advocate Abby Johnson.

She goes on to report to that while the statement from the Diocese of Spokane is rather ambiguous, a "clarifying email from the Diocese of Spokane's director of communications stated that yes, priests in Spokane may in good conscience participate in 40 Days for Life vigils without being considered disobedient to their ordinary." What remains unclear is whether it was a matter of miscommunication (doubtful, it seems, based on the evidence) or a complete change of direction by the Bishop. Read the entire CWR blog post.

Faith in China: Sunday Mass at Beijing's North Church

Sunday Mass at Beijing's North Church | Anthony E. Clark, Ph.D. | September 16, 2011 | Ignatius Insight

After Sunday Mass at Beijing's largest and oldest church, Beitang (North Church), well over a thousand faithful filed out of their pews into the Chinese-style courtyard leading to the church's dramatic entrance. Inside, one man, roughly mid-thirties, stretched his arms high above his head, looked upward, and offered prayers of thanksgiving. His right hand held a long, worn, rosary. Behind him several elderly men and women began intoning Catholic hymns that still use the melody and style of Ming dynasty Buddhist chanting.

Several priests gathered in the courtyard to meet with members of the parish – most of the priests are older, but at least one appeared recently ordained. During Mass, the celebrant spoke animatedly about Christ's exhortation: "Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. What profit would there be for one to gain the whole world and forfeit his life."

This is a difficult topic in modern China, wrenched apart by its two antagonized personalities, one explicitly Marxist, and another implicitly capitalistic. China's class division grows more intense while it purports to espouse Marx's ideology of class elimination. But the Middle Kingdom has always been a place of accepted paradox. The ancient philosopher, Han Feizi, once wrote about a weapons seller who boasted that his spears could pierce through anything, and that his shields could not be pierced – a nearby man then asked the seller if his spears could pierce his own shields. "Spear/shield" (maodun) is thus the Chinese word for paradox, and the notion that all things are essentially "spear/shield" is a common Chinese assumption. China's Catholics, who live in a society that seemingly accepts that Marxism can be materialist (Marx would have blanched), try to live their faith in an impossible situation. To some extent, even they live in a state of paradox – "spear/shield."

Evolution and Art (the "signature of man")

In an American Spectator essay, "Evolution Needs to Evolve", Hal G.P. Colebatch writes:

Monkeys and men appear to have a common ancestor. Monkeys, like men, have hands. But, as Chesterton said, the significant point is not that monkeys have hands, but that, compared to Man, monkeys do almost nothing with them. A five-year old child can paint a crude picture of a monkey. But not the wisest monkey ever painted a picture of a child. Years of experiments trying to teach apes language show they cannot form even the simplest sentences.

If a monkey was born capable not only of gathering nuts and bananas but also of building cathedrals, writing Hamlet or flying to the moon, we would see it as a major objection to the pure theory of evolution. We might even be tempted to believe that a God had intervened somewhere along the line.

But Man is born capable of doing these things and has done them. The fact speaks for itself. Further, as far as paleontology can tell us, Cro-Magnon Man, the earliest form of Homo sapiens, had brains as good as modern men -- Cro-Magnon Man simply knew less. We know from cave paintings that 16,000 years ago at least Man had highly developed art.

Why? Art is useless for survival. There is no reason why evolution should have produced it. It is possible to be reminded of Gandalf's cryptic comment in The Lord of the Rings: "Something else is at work."

The reference to Chesterton is, I believe, a reference to one or more passages in The Everlasting Man, one of his greatest books. Chesterton wrote:

It is the simple truth that man does differ from the brutes in kind and not in degree; and the proof of it is here; that it sounds like a truism to say that the most primitive man drew a picture of a monkey and that it sounds like a joke to say that the most intelligent monkey drew a picture of a man. Something of division and disproportion has appeared; and it is unique. Art is the signature of man.

That is the sort of simple truth with which a story of the beginnings ought really to begin. The evolutionist stands staring in the painted cavern at the things that are too large to be seen and too simple to be understood. He tries to deduce all sorts of other indirect and doubtful things from the details of the pictures, because he can not see the primary significance of the whole; thin and theoretical deductions about the absence of religion or the presence of superstition; about tribal government and hunting and human sacrifice and heaven knows what. ... When all is said, the main fact that the record of the reindeer men attests, along with all other records, is that the reindeer man could draw and the reindeer could not. If the reindeer man was as much an animal as the reindeer, it was all the more extraordinary that he could do what all other animals could not. If he was an ordinary product of biological growth, like any other beast or bird, then it is all the more extraordinary that he was not in the least like any other beast or bird. He seems rather more supernatural as a natural product than as a supernatural one. ...

It is not contended here that these primitive men did wear clothes any more than they did weave rushes; but merely that we have not enough evidence to know whether they did or not. But it may be worthwhile to look back for a moment at some of the very few things that we do know and that they did do. If we consider them, we shall certainly not find them inconsistent with such ideas as dress and decoration. We do not know whether they decorated other things. We do not know whether they had embroideries, and if they had the embroideries could not be expected to have remained. But we do know that they did have pictures; and the pictures have remained. And there remains with them, as already suggested, the testimony to something that is absolute and unique; that belongs to man and to nothing else except man; that is a difference of kind and not a difference of degree. A monkey does not draw clumsily and a man cleverly; a monkey does not begin the art of representation and a man carry it to perfection. A monkey does not do it at all; he does not begin to do it at all; he does not begin to begin to do it at all. A line of some kind is crossed before the first faint line can begin.

On a lighter note, see the young Chesterton's satirical piece, "Half Hours in Hades" (written and illustrated in 1891, when Chesterton was seventeen), which contains a section on the "evolution of demons". The piece contains this little bit of hilarious brilliance:

To proceed at once to business, I will first introduce to my young readers the Common, or "Garden" serpent, so called because its first appearance in the world took place in a garden. Since that time its proportions have dwindled considerably, but its influence and power have largely increased; it is found in almost everything.

Indeed!

"I think I understand how the typical Protestant feels...

... about sacramentalism not only because I was a Protestant but because it is a natural and universal feeling. The Catholic doctrine of the sacraments is shocking to everyone. It should be a shock to Catholics too. But familiarity breeds dullness.

To Protestants, sacraments must be one of two things: either mere symbols, reminders, like words; or else real magic. And the Catholic definition of a sacrament — a visible sign instituted by Christ to give grace, a sign that really effects what it symbolizes — sounds like magic. Catholic doctrine teaches that the sacraments work ex opere operato, i.e., objectively, though not impersonally and automatically like machines. They are gifts that come from without but must be freely received.

Protestants are usually much more comfortable with a merely symbolic view of sacraments, for their faith is primarily verbal, not sacramental. After all, it is the Bible that looms so large in the center of their horizon. They believe in creation and Incarnation and Resurrection only because they are in the Bible. The material events are surrounded by the holy words. The Catholic sensibility is the inside-out version of this: the words are surrounded by the holy facts. To the Catholic sensibility it is not primarily words but matter that is holy because God created it, incarnated himself in it, raised it from death, and took it to heaven with him in his ascension.

Orthodox Protestants believe these scriptural dogmas, of course, just as surely as Catholics do. But they do not, I think, feel the crude, even vulgar facticity of them as strongly. That's why they do not merely disagree with but are profoundly shocked by the real presence and transubstantiation. Luther, by the way, taught the real presence and something much closer to transubstantiation than most Protestants believe, namely consubstantiation, the belief that Christ's body and blood are really present in the Eucharist, but so are the bread and wine. Catholics believe the elements are changed; Lutherans believe they are added to.

Most Protestants believe the Eucharist only symbolizes Christ, though some, following Calvin, add that it is an occasion for special grace, a sign and a seal. But though I was a Calvinist for twenty one years, I do not remember any emphasis on that notion. Much more often, I heard the contrast between the Protestant " spiritual " interpretation and the Catholic "material ", "magical" one.

The basic objection Protestants have to sacramentalism is this: How can divine grace depend on matter, something passive and unfree? Isn't it unfair for God's grace to depend on anything other than his will and mine? I felt that objection strongly until I realized that the sheer fact that I have a body — this body, with this heredity, which came to me and still comes to me without my choice — is also "unfair". One gets a healthy body, another does not. As one philosopher said, "Life isn't fair."

— Peter Kreeft, from the chapter, "The Sacraments", in Fundamentals of the Faith.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers