Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 230

March 18, 2012

The Introduction to "Adam and Eve After the Pill" by Mary Eberstadt

The Introduction to Adam and Eve After the Pill: Paradoxes of the Sexual Revolution by Mary Eberstadt

Time magazine and Francis Fukuyama, Raquel Welch and a series of popes, some of the world's leading scientists, and many other unlikely allies all agree: No single event since Eve took the apple has been as consequential for relations between the sexes as the arrival of modern contraception. Moreover, there is good reason for their agreement. By rendering fertile women infertile with nearly 100 percent accuracy, the Pill and related devices have transformed the lives and families of the great  majority of people born after their invention. Modern contraception is not only a fact of our time; it may even be the central fact, in the sense that it is hard to think of any other whose demographic, social, behavioral, and personal fallout has been as profound.

majority of people born after their invention. Modern contraception is not only a fact of our time; it may even be the central fact, in the sense that it is hard to think of any other whose demographic, social, behavioral, and personal fallout has been as profound.

For many decades now, prescient people have understood as much. Though these days contraception as such attracts little interest in secular academia, being more or less simply taken for granted as a fact of life, such neglect was not always the rule. As early as I929, for example, fabled social observer Walter Lippmann was calling attention to the radical implications of reliable birth control—even explicitly agreeing with the Catholic Church in his classic book A Preface to Morals that modern contraception "is the most revolutionary practice in the history of sexual morals." In 2010—the year that the Pill celebrated its fiftieth anniversary—that early verdict appeared wholly vindicated, as an outpouring of reflections on that anniversary affirmed the ongoing and colossal changes that optional and intentional sterility in women has wrought.

The technological revolution of modern contraception has in turn fueled the equally widely noted "sexual revolution"—defined here and elsewhere as the ongoing destigmatization of all varieties of nonmarital sexual activity, accompanied by a sharp rise in such sexual activity, in diverse societies around the world (most notably, in the most advanced). And though professional nitpickers can and do quibble about the exact nature of the connection between the two epochal events, the overall cause and effect is plain enough. It may be possible to imagine the Pill being invented without the sexual revolution that followed, but imagining the sexual revolution without the Pill and other modern contraceptives simply cannot be done.

Like the technological revolution that occasioned it, this sexual revolution, too, has long attracted the attention of social observers. In I956, for example, the towering twentieth-century sociologist Pitirim Sorokin—founder of Harvard's Department of Sociology—published a short book called The American Sex Revolution. Written for a general audience and much discussed in its time, it forcefully linked what Sorokin variously called "sex freedom" and "sex anarchy" to a long list of what he argued were critical social ills, including rising rates of divorce and illegitimacy, abandoned and neglected children, a coarsening of the arts high and low, and much more, including the apparent increase in mental disorders. "Sex obsession", argued Sorokin, now "bombards us continuously, from cradle to grave, from all points of our living space, at almost every step of our activity, feeling, and thinking."

Around the same time, another celebrated secular Harvard sociologist, Carle Zimmerman, published his masterwork of history and sociology called Family and Civilization. Though less immediately concerned with the sexual revolution as such than Sorokin had been in his more popularized text, Zimmerman's work likewise casts obvious, albeit tacit, criticism upon the social changes unleashed by modern contraception. Family and Civilization repeatedly linked declines in civilization to the features of what the author called "the atomistic family" type, including rising divorce rates, increasing promiscuity, juvenile delinquency, and neglect of children and other family responsibilities. These were features of modern society that Zimmerman, like Sorokin (and many other people in those days), judged to be self-evidently malignant. "The United States", Zimmerman concluded, "will reach the final phases of a great family crisis between now [1947] and the last of this century"—one "identical in nature to the two previous crises in Greece and Rome".

Of course one need not be a Harvard sociologist to grasp that the technological severing of nature from nurture has changed some of the most elemental connections among human beings. Yet plainly, the atmosphere surrounding discussion of these changes has changed radically between our own time and that of the mid-twentieth century. What Zimmerman felt free to say in the I940s and Sorokin in the I950s about the downside of changing mores are by and large not things that most people feel free to say about our changed moral code today—not unless they strive to be written off as religious zealots or as the blogosphere's laughingstock du jour. Again, as the celebrations of the Pill's fiftieth anniversary went to show, the sexual revolution is now not only a fait accompli for the vast majority of modern men and women; it is also one that many people openly embrace. Fifty years after the Pill's approval and counting, it is beyond question that liberationists and not traditionalists have written the revolution's public legacy across the West.

In this standard celebratory rendition, the sexual revolution has been a nearly unmitigated boon for all humanity. Along with its permanent backup plan, abortion, it has liberated women from the slavery of their fertility, thus freeing them for personal and professional opportunities they could not have enjoyed before. It has liberated men, too, from their former chains, many would argue—chiefly from the bondage of having to take responsibility for the women they had sex with and/or for the children that resulted. It has also enriched children, some would posit, by making it easier to limit family size, and hence share the pie of family wealth and attention among fewer claimants. "In my mind," as one modern historian summarized the standard script, "there can be no doubt that, on the whole, the sexual revolution of the '60s and '70s improved the quality of life for most Americans."

It is the contention of this book that such benign renditions of the story of the sexual revolution are wrong. That is to say, they are critically incomplete when measured against the weight of the evidence now before us.

Thus the chapters ahead tell a different version of what the sexual revolution has wrought than the Panglossian version that is standard today. They examine from different angles a wide body of empirical and literary and other evidence about what really happened once nurture was divorced from nature as never before in history. My aim in these pages is to understand in a new way certain of the human fallout of our post-Pill world—to shed light on what Sorokin once provocatively and probably correctly called a revolution "more far-reaching than those of almost all other revolutions, except perhaps the total revolutions such as the Russian".

The evidence presented in the following chapters, I believe, roundly confirms two propositions that are—or ought to be—deeply troubling to serious people. First, and contrary to conventional depiction, the sexual revolution has proved a disaster for many men and women; and second, its weight has fallen heaviest on the smallest and weakest shoulders in society—even as it has given extra strength to those already strongest and most predatory. For decades now, and apparently out of view of many people telling the tale, a compelling record has been building of the real costs that have been mounting since procreation became so effectively amputated from sexual behavior for so many people. It is a record rich now in detail from a variety of sources ranging from the social sciences—especially psychology and sociology—to more microscopic accounts of the revolution's real and permanent consequences in many lives. Like a mosaic, it is also a record that reveals and sheds light variously depending on which angle we choose to view.

Revealing that mosaic is the substance of this book. Chapter 1 concerns the contemporary secular intellectual backdrop inherited from the tumultuous i960s. For decades now, it argues, the negative empirical fallout from the sexual revolution, while plain to see, has persistently been met with deep and entrenched denial among academic and other cultural authorities. So thoroughgoing is this denial, the chapter details, that it bears comparison to the deep denial among Western intellectuals that was characteristic of the last great debate that ran for decades—namely, the Cold War. Hence, the subtitle is "The Will to Disbelieve", which takes its name from a famous essay on intellectual denial from that other debate past. This opening of the book examines the evidence of such intellectual denial and the probable reasons for it.

The book then moves from theory to the ground, as it were, to examine the effects of the sexual revolution on actual human beings: women, children, and men. "What Is the Sexual Revolution Doing to Women? What Does Woman Want?", a chapter examining trends in current fashionable writing about women and marriage, exhumes the pervasive themes of anger and loss that underlie much of today's writing on romance. This chapter includes discussion of the latest sociological literature arguing for the "paradox of declining female happiness"—that is, the unexplained gap between the unprecedented freedoms enjoyed by today's women and their simultaneous increasing unhappiness as measured by social science. The fact that women disproportionately bear the burdens of the sexual revolution, I argue here, might explain that hitherto unexplained paradox.

The following chapter, "What Is the Sexual Revolution Doing to Men? Peter Pan and the Weight of Smut", examines more paradoxical fallout from the revolution. Even as widely available contraception and abortion have liberated men from husbandhood and fatherhood, it has also encouraged in many a new and problematic phase of prolonged adolescence— what sociologist Kay S. Hymowitz has perspicaciously identified as "pre-adulthood". Then there is the other paradoxical consequence of sexual liberation: widespread pornography on a scale and with a verisimilitude never seen before. This chapter cites interesting and recent work by psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, and other experts on a range of issues relating to Internet pornography: the sharp rise in pornographic addiction, the evidence of serious psychological problems of the addicted, the chilling effect of increasing pornography in the public square, and other measures of social harm.

Chapter 4, "What Is the Sexual Revolution Doing to Children? The 'Pedophilia Chic', Then and Now", covers one uniquely disturbing legacy of sexual liberation, which is the assault unleashed from the 1960s onward on the taboo against sexual seduction or exploitation of the young. This chapter argues that ironically, the Catholic priest-boy sex scandals that erupted in 2002—which evoked widespread revulsion across the West at these repeated violations of the taboo against sex with the young—have effectively served to interrupt this profoundly destructive former trend. Interestingly, this makes the taboo against sex with youngsters the only one of those considered in this book in which some "rollback" of the sexual revolution has been demonstrated.

Chapter 5, "What Is the Sexual Revolution Doing to Young Adults? What to Do about Toxic U?", examines in detail what may be ground zero of the sexual revolution today: the secular American campus. Using sources ranging from social science to popular culture, it sifts the ingredients of the toxic collegiate social brew made possible by the sexual revolution. The feral rates of date rapes, hookups, and binge drinking now documented on many campuses, this chapter argues, are direct descendants of the sexual revolution—one whose central promise is that women can and should be sexually available in the name of liberation, which translated into the reality of the modern campus has empowered and largely exonerated predatory men as never before.

Chapters 6 and 7 move back from the ground to a more abstract plane to examine other society-wide changes wrought by the revolution—in particular, its effect on social mores. They focus on what Friedrich Nietzsche called "the trans-valuation of values", meaning the ways in which the existing moral code would become transformed in a social order no longer centered on Judeo-Christianity. Such a transvaluation, I argue, is being wrought by the revolution in ways we are only beginning to understand. Chapter 6, subtitled "Is Food the New Sex?", argues that the morality once attached to sexual behavior has been transferred onto an unlikely yet fascinating substitute—matters of food. Chapter 7, subtitled "Is Pornography the New Tobacco?", similarly traces the stunning parallels between yesteryear's laissez-faire attitudes about one widely accepted substance— tobacco—and today's laissez-faire attitudes about the substance of pornography.

The book's closing chapter examines what may be the ultimate of the many paradoxes ushered in by the collision between the sexual revolution and human nature itself. "The Vindication of Humanae Vitae" examines the remarkable predictions made in that watershed document just a few years after the Pill itself appeared and examines a large historical irony: that one of the most reviled documents of modern times, the Catholic Church's reiteration of traditional Christian moral teaching, would also turn out to be the most prophetic in its understanding of the nature of the changes that the revolution would ring in. This chapter explores the extraordinary irony of our own particular moment in time, half a century after the sexual revolution—one in which every prediction made by Paul VI has been vindicated, even as the traditional Christian teaching against artificial contraception has come to be reviled by its adversaries and abandoned by Christians themselves as never before.

One final note: These chapters are indeed, as the title suggests, reflections—not manifestos or screeds or roadmaps to activism. It is my hope that readers will bring to them the same spirit with which the pages ahead were written: that of seeking sincerely and without cant to understand something of the manifold and unprecedented fallout of what may yet turn out to be the most consequential social revolution of all.

[From Adam and Eve after the Pill by Mary Eberstadt, © 2012 Ignatius Press. This online version of the Introduction eliminates the footnotes found in the print and e-book editions.]

• Visit the website for Adam and Eve after the Pill

• "The Party's Over": A Catholic World Report interview with Mary Eberstadt

March 16, 2012

"But whoever lives the truth comes to the light..."

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for March 18, 2012, the Fourth Sunday of Lent | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

2 Chr 36:14-16, 19-23

Ps 137:1-2, 3, 4-5, 6

Eph 2:4-10

Jn 3:14-21

If I've heard it once, I've heard it a thousand times. If I've said it once, I've said it about the same number of times.

"It" is John 3:16, one of the most famous verses in the Bible: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him might not perish but might have eternal life." I first memorized it at the age of four, reciting it before a small Fundamentalist congregation.

That verse, from today's Gospel reading, is a beautiful summary, from the lips of the Savior, of the heart of salvation. As Pope Benedict XVI stated in the opening of his encyclical on love, "Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction." And that is an apt description of the season of Lent: a transforming encounter with a person, the Son of God, who gives us life, direction, purpose.

Nicodemus, a Pharisee, sought out an encounter with Jesus. He came at night, fearful of being seen with Jesus The nighttime, in John's Gospel, symbolizes the spiritual darkness in which man lives apart from God, a theme introduced in the opening verses of John's Gospel (Jn 1:4-5). This ruler of the Jews realized his need for spiritual light, readily confessing his belief that Jesus was "a teacher who has come from God." Surely he must have been challenged by Jesus' declaration that "whoever lives the truth comes to the light, so that his works may be clearly seen as done in God."

A decisive direction was presented to Nicodemus. Yet the Apostle John does not describe what reaction Nicodemus had to the words of Jesus; the secretive visitor seems to have silently disappeared back into the night. Perhaps St. John did not immediately reveal Nicodemus's choice because Nicodemus, in a certain way, is each of us. We have met Jesus, we have sat at his feet, and we have heard his words. What will we do?

This is one of so many brilliant qualities of the Fourth Gospel, which is a literary and spiritual icon offering a window into the mystery of Christ—and into the mystery of our own hearts. We can relate to Nicodemus, just as we can understand the joy of the woman at the well (Jn 4), the hunger of the crowds who followed Jesus (Jn 6), and the fear and anguish of Peter, who betrayed Jesus after the arrest in the garden (Jn 18). "Nicodemus," wrote Monsignor Romano Guardini in his classic work, The Lord, "has been shaken by Jesus' mysterious power; his wonderful teaching has struck home." But, just like the woman at the well, the crowds, and Peter, there was at first bewilderment and confusion. He no longer wanted to be in the darkness, but he was not ready to step fully into the light. He would stay in the shadows for a while longer, pondering the person and words of Jesus.

But eventually Nicodemus did, cautiously, step forward a bit, coming to Jesus' defense before his fellow Pharisees (Jn 7:50-52). But his appeal for fairness was met with suspicious anger. Perhaps he pondered again these words: "whoever lives the truth comes to the light…"

We meet Nicodemus one more time, after the Crucifixion. Pilate had given Joseph of Arimathea permission to remove and bury Christ's body, and Nicodemus, "the one who had first come to him at night, also came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes weighing about one hundred pounds" (Jn 19:39). He was finally in the light completely, revealing himself as a disciple of the Son of Man who had been lifted up "so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life."

Lent is a time to come into the light and to embrace the gift of eternal life. That's worth hearing about a thousand times. Or more.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the March 22, 2009, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

About that Vatican Press Release concerning the SSPX

Michael J. Miller makes some helpful observations on the CWR blog:

Today the Vatican issued a press release entitled "Meeting Between the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Superior General of the Society of St. Pius X, March 16, 2012" in the original French and an Italian translation. An independent English translation is posted below.

The Vatican Information Service (VIS) translation, although accurate, omits all honorific titles, appears to have been produced hurriedly, and lacks nuance. One example: it says that the Doctrinal Preamble "defined" certain doctrinal principles, etc., a technical term that is much too forceful to convey the meaning of the French verb énoncer, "to enunciate". (The CDF expressly allowed for the possibility of modifying the wording of the Preamble.)

The chronology in the Communiqué is telescoped: Bishop Fellay's response, proposing modifications to the Doctrinal Preamble, was sent to the Vatican in December. The CDF replied requesting clarifications, which were duly sent later that month. The "response … that arrived in January 2012" is therefore presumably at least the third attempt by the General Superior of the SSPX to state their position with regard a doctrinal basis for reconciliation with the Holy See.

The procedural details in paragraph 3 of the Communiqué are significant. This was not a vote by a panel of judges. The CDF, made up of cardinals and theologians, examined the SSPX response and probably summarized its findings in writing, but it acted only in an advisory capacity. The Pope, having taken their findings into consideration, has the authority to make the judgment about this doctrinal matter. The paragraph ends by referring to the SSPX indirectly as "the aforesaid Society". The legal phraseology is a pointed reminder that there are canonical as well as doctrinal questions involved in the CDF-SSPX talks; it also prompts the reflection that, although the Society has chosen St. Pius X as their patron saint and invokes his doctrinal authority, it is only a society of priests that was formed after Vatican II during the pontificate of Paul VI.

Even though the Society's response was deemed inadequate, the final paragraph in the Communiqué leaves the door open. The SSPX Superior General was invited "à bien vouloir clarifier sa position", "to be so kind as to clarify his position". This is a typical French formality at the conclusion of a bureaucratic document, but the expression can also mean "really to try to clarify his position," implying that now is not the time for maneuvering.

Read his entire post, which includes his independent translation of the release.

Huston, you have a problem. However, we have a solution.

Rosie O'Donnell, whose deep analysis of current events includes once comparing the Catholic Church to the Jonestown cult, recently expressed grave concern (see video below) that "women in America" are "once again" having to "fight for reproductive rights". Her guest, the talented Anjelica Huston, perhaps still angry about being embarrassed many years ago by the philandering Jack Nicholson, wonders, "How did guys get to be the ones who solely discuss it?", perhaps not aware that she and O'Donnell were discussing "it" on an hour-long primetime news program (CNN's "The Piers Morgan Tonight Show", guested hosted by O'Donnell).

Huston then intones, "It's the Dark Ages!" (What would fundamentalist Protestants and fundamentalist secularists do without recourse to the "Dark Ages"? I suspect their history-challenged, rhetorically-wanting brains would implode.) Intent upon showing that her lack of substantive knowledge is not limited to only past events, she says, "My theory was that if we dropped radios and blankets on Afghanistan, we wouldn't be having the problems that we're having now. I'm just so depressed about the state of the world." Unfortunately, she fails to explain how radios and blankets—which have been in Middle East since, what, the "Dark Ages"?—would ward off terrorist attacks and thwart radical Islamism. (To be fair, we all know the Iron Curtain collapsed under the weight of radios, blankets, and Happy Meals. Right?)

Huston is correct, however, in saying, "I don't understand a lot of things in present day America." She obviously doesn't understand that "reproductive rights" are not under assault, but are actually the reason used to currently assault religious liberty. As for the supposed goodness and inherent helpfulness of contraception, abortion, and related modern wonders, she would do well to read Mary Eberstadt's new and excellent book, Adam and Eve After the Pill: Paradoxes of the Sexual Revolution (Ignatius Press; visit the book's website), which readily documents the painful and destructive chaos unleased upon individuals, families, and communities by "reproductive justice" — a term, by the way, that is a bald-faced lie, as there is no reproduction and no justice involved.

Some of the basic facts are touched on in the video trailer for the Eberstadt's book:

Perfecting the Art of Totalitarianism

Perfecting the Art of Totalitarianism | Brian O'Neel | Catholic World Report

Since the mid-20th century, North Korea has become the most fully realized totalitarian regime in history.

For most people, a normal day might look like the following.

After rising and getting yourself ready for the day, you read the newspaper or get your news online. You like to be informed, so you read the op-ed section, making sure to see what both Mr. Liberal Columnist and Miss Conservative Columnist have written.

During your commute, you flip back and forth among any number of radio stations. After arriving and beginning the day's work, you might now and then take break and talk with colleagues. Naturally, each person would express his or her own opinions, which might lead to some strong disagreements.

If you work a blue-collar job, maybe you occasionally check your cell phone for texts or emails. If yours is a white-collar job, you would probably check your work and personal emails accounts. You might also surf the web, either because of a project or to handle some light personal business.

After returning home, maybe you watch the news, read the newspaper, or peruse a magazine that came in the mail. After dinner, maybe you gather with friends at a local coffee house or pub for some carefree conversation over some current political topic. Or maybe you stay home and pray the family Rosary or the Liturgy of Hours.

Before going to bed, if you didn't stay up and watch the news or a late-night comedy show, you might read some book of your choosing. Perhaps, for the sake of illustration, an excoriating evaluation of your nation's leader.

Perfecting the system

If you live in most nations on the planet, the description above probably looks familiar. If, however, you live in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (or the DPRK, and better known as North Korea), 12 of the items described above would not be possible, and six of them would get you and your whole family arrested. If the latter happened, it is very likely that none of you would live beyond five years, much less the duration of your 15-year sentence.

Such is life in the world's most totalitarian state—which is not, as many claim, Stalinist so much as it is a combination of Stalinism, pre-1945 Japanese fascism, and national socialism in slightly varied forms.

"Put on the Garments of Christ": Cyril of Jerusalem and the Origins of Lent

by Carl Sommer | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

If Cyril of Jerusalem were among us today, he might merely challenge us to take our Lenten devotions a little deeper.

In the Spring of 347, Cyril of Jerusalem delivered a series of teachings to the catechumens of Jerusalem. In the introduction to these lectures, Cyril told his auditors, "This charge I give you, before Jesus the Bridegroom of souls come in….A long notice is allowed you; you have forty days for repentance…" 1 Seated in the magnificent, newly completed Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Cyril delivered an impassioned plea for genuine repentance, conversion, and the acceptance of an entirely new way of life. "Even Simon Magus once came to the Laver: he was baptized, but was not enlightened; and though he dipped his body in water, he enlightened not his heart with the Spirit: his body went down and came up, but his soul was not buried with Christ, nor raised with Him" 2, Cyril warned the catechumens.

It must have been a powerful moment for Cyril's hearers. Seated in the very place where Christ spent three days in the tomb, then rose from the dead, Cyril's powerful rhetoric must have touched them to the core. And, indeed, his words still have the same power to this very day, for in reading them anew, I am reminded how feeble my own Lenten preparations are, and am stirred to genuine conversion.

March 15, 2012

On God's "Unrest" and Human Silence

by Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

"The restless heart,…echoing St. Augustine, is the heart that is ultimately satisfied with nothing less than God, and in this way becomes a loving heart. Our heart is restless for God and remains so, even if every effort is made today, by means of more effective anaesthetizing methods, to deliver people from this unrest. But not only are we restless for God; God's heart is restless for us. God is waiting for us. He is looking for us. He knows no rest either, until he finds us. God's heart is restless, and this is why he set out on the path towards us—to Bethlehem, to Calvary, from Jerusalem to Galilee and on to the very ends of the earth."

— Pope Benedict XVI, Solemnity of the Epiphany, 2012 (L'Osservatore Romano, January 11, 2012)

"Silence is nothing merely negative; it is not the mere absence of speech. It is a positive, a complete world in itself. Silence has greatness simply because it is. It is, and that is its greatness, its pure existence."

— Max Picard, The World of Silence, 1948.

"Silence is an integral element of communication; in its absence, words rich in content cannot exist. In silence, we are better able to listen to and understand ourselves; ideas come to birth and acquire depth; we understand with greater clarity what it is we want to say and what we expect from others; and we choose how to express ourselves. By remaining silent we allow the other person to speak, to express him or herself, and we avoid being tied simply to our own words and ideas without them being adequately tested."

— Pope Benedict XVI, Message for 46th World Communications Day, May 20, 2012

I

We are used to the notion that God is in peace, at rest. If He were not, He would be lacking something necessary for the complete beatitude in which He exists. God did not create the world because He needed something that He was lacking to Him. Yet, the cosmos, though not necessary either from God's side or the world's side, was created for a purpose, as it were, a human purpose. Christian revelation is unique since it is based on the fact that God goes out of His Trinitarian life to "dwell amongst us." The Incarnation implies that something needs to be accomplished in the world that only God can achieve or at least inspire.

In the creation of the free, intelligent being we call man, God put Himself at risk. This risk followed from the very nature and hence purpose of His creation. This purpose was to invite other free beings into His own inner Trinitarian life. Creation is for man, not man for creation. To bring this purpose about, God had, so to speak, to play fair. He could not make the world a deterministic place where what He wanted would automatically come to pass even in the free being. The meaning of the creation of a real, finite, free, and rational being was that the end of God's plan had to be freely accepted on the side of the creature. And if initially it was not accepted, as it evidently was not, God would have to freely and intelligently respond, as it were, to man's free choice.

This response is the origin of Benedict's use of the notion that God has some "unrest" in His being. Our world is not just one in which we are looking for some answer to what we are, an answer to our own restlessness. This restlessness itself is put in us from the very beginning because we are created to—invited to—participate in this inner life of rest in the Godhead. Such response implies an active providence on the part of God. His constant reaction to human evil is to find what is good and bring forth from it something better, yet still bearing God's respect for human freedom. This is what is known as the divine plan of human salvation.

Do we ever hear this divine "unrest" in our souls? In some sense, I suppose, we would call it grace. Grace is not merely justice. God's mode of redemption, through the Cross—a way that none of us would have chosen—represents something beyond our expectations. But God's way remains within the order of freedom, both human and divine. Something at risk is really going on among us. This is the more profound meaning of hell. Our acts are not ultimately indifferent. We are every day deciding what we are and what we shall be. We do this within the confines of our individual lives, whenever and wherever they play themselves out. We are given enough rope, as they say, to hang ourselves and more than enough to grasp the gift of salvation. This is the meaning of the relation of mercy and justice. Indeed, as St. Paul says, God's grace is "sufficient" for us. We are not, any of us, left alone. But we are left free.

II.

Following this Epiphany reflection on the "restlessness" of God, Benedict wrote a brief but powerful reflection on silence in connection to the upcoming World Day of Communication. A young man I know enthusiastically called it to my attention even before it appeared in L'Osservatore Romano. In it, the Holy Father shows himself to be aware of something we in the colleges and universities notice every day, namely, the lack of silence in students' lives. With the internet and cell phones and the many various modifications, everyone can be busy all day or night, every day of the year, hearing and talking.

"The process of communication nowadays is largely fuelled by questions in search of answers," Benedict wrote. "Search engines and social networks have become the starting point of communication for many people who are seeking advice, ideas, information and answers. In our time, the internet is becoming ever more a forum for questions and answers—indeed, people today are frequently bombarded with answers to questions they have never asked and to needs of which they were never aware."

Watching the world of cell-devices today, one can easily get the impression not of freedom but a kind of slavery, an inability to depend on the human memory or experience. Some authority is always out there to modify, contradict, or affirm what anyone thinks he know. Few would deny the value of knowing "facts" and having them immediately at hand. And yet, the Pope is right. It is rather eerie to have answers before we have questions, to be prodded to needs we were pleasantly unaware of moments before.

Again, we do not much live in a world of silence. A moment of silence almost seems like an irresponsible use of time when we could be doing something useful. In a famous introductory passage to his work, On Duties, Cicero cites Marcus Tullius Scipio who once remarked he was "never less idle than when he had nothing to do, and never less lonely than when he was by himself." The Christian addendum to these memorable words would be that, for us, we have seen the face of God. We are also taught that we can converse with Him. He is not an isolated or inert being. "When word and silence become mutually exclusive," Benedict tells us, "communication breaks down, either because it gives rise to confusion or because, on the contrary, it creates an atmosphere of coldness; when they complement one another, however, communication acquires value and meaning."

III.

In today's world of all news, all the time, reading the following sentence of the Pope is almost shocking: "Silence is an integral element of communication; in its absence, words rich in content cannot exist." The word bears reality to us. Each existing thing deserves and invites pondering. We often allow ourselves only to see the surface of things, including one another.

"By remaining silent, we allow the other person to speak, to express him or herself, and we avoid being tied simply to our own words and ideas without them being adequately tested." It is out of silence that the voice of others arrive to us and arise in us. But unless we ourselves have contemplated what is, have wondered and searched for what it is all about, we will not easily recognize what we hear. Our silence is not designed to lock us into ourselves but to free us to listen to what is not ourselves.

"Deeper reflection helps us to discern the links between events that at first sight seem unconnected, to make evaluations, to analyze messages; this makes it possible to share thoughtful and relevant opinions, giving rise to an authentic body of shared knowledge." Aristotle taught that what the best friends have most in common is agreement on the highest things. Benedict points out that much of what married couples know of each other they learn in silence.

"Many people," Benedict tells us, "find themselves confronted with ultimate questions of human existence: Why am I? What can I know? What ought I to do? What may I hope? It is important to affirm those who ask these questions, and to open up the possibility of a profound dialogue, by means of words and interchange, but also through the call of silent reflection, something that is often more eloquent than a hasty answer…." One wonders how many students pass through our colleges and universities without ever really wondering about these basic questions and what answers might be given, even in silence.

Indeed, how many people pass through life itself without asking them? The culture conspires to never answer them because it is itself closed off from the sources of silence and revelation in which these answers are heard. It denies an order of nature or human soul, a providence of God at work in history. Hence, there is nothing to look for or to hear. The culture wants the answer to be, "There are no answers. Therefore tolerate everything; deny truth to anything." Yet, Benedict rightly adds: "Men and women cannot rest content with a superficial and unquestioning exchange of skeptical opinions and experiments of life."

Benedict does wonder if there cannot be at least some "websites" that might help us to silence and meditation. He points out that even one verse of the Scripture can serve to ground us in the reality of the transcendent. But we come across this meaning only in silence, even if we read it or hear it first in public. Benedict recalls the beautiful homily that is heard on Holy Saturday about the whole world suddenly being in stillness, as if something is gone, as if something is awaited.

Benedict then turns to a theme that was all through his book, Jesus of Nazareth. "If God speaks to us even in silence, we in turn discover in silence the possibility of speaking with God and about God." All reading of the Old and New Testaments, all scholarship points to the fact that Jesus was who He said He was. He was the Word who dwelt amongst us. "I and the Father are one." With this event, the world can never be the same, however much we might want it to be, because of this fact. "Silent contemplation immerses us in the source of that Love who directs us towards our neighbours so that we may feel their suffering and offer them the light of Christ…"

God's "plan of salvation" is "being accomplished through our history by word and deed." Everything conspires in our noisy world to prevent us from seeing such events working themselves in our lives and in in that of those we love. But that plan is what is happening. In silence we hear; in light we see. A world day of communication is nothing if what is communicated are not the deepest things of what we are.

We best see this depth in the silence that teaches us what the words, and the Word, mean to us and our kind.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

He is the author of numerous books on social issues, spirituality, culture, and literature including Another Sort of Learning, Idylls and Rambles, A Student's Guide to Liberal Learning, The Life of the Mind (ISI, 2006), The Sum Total of Human Happiness (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), The Regensburg Lecture (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), and The Mind That Is Catholic: Philosophical and Political Essays (CUA, 2008). His most recent book from Ignatius Press is The Order of Things(Ignatius Press, 2007).

His most recent book, The Modern Age, is available from St. Augustine's Press. Read more of his essays on his website.

The Party's Over: Mary Eberstadt on what the sexual revolution has wrought

The Party's Over | Catholic World Report | Interview

Mary Eberstadt on men, women, and what the sexual revolution has wrought

"No single event since Eve took the apple has been as consequential for relations between the sexes as the arrival of modern contraception," writes Mary Eberstadt in the introduction to her new book Adam and Eve After the Pill: Paradoxes of the Sexual Revolution (Ignatius). A research fellow at the Hoover Institution and consulting editor to Policy Review, Eberstadt's writings have appeared in a variety of newspapers, magazines, and online journals, including First Things, the Weekly Standard, National Review, National Review Online, the Claremont Review of Books, and the Wall Street Journal. Her previous books include The Loser Letters: A Comic Tale of Life, Death, and Atheism (Ignatius). She recently spoke with CWR about her latest book, the far-reaching consequences of the sexual revolution, and what the Catholic Church has to offer in today's debates over birth control and in the still-raging battle of the sexes.

Catholic World Report: In a recent op-ed in the New York Times, retired law professor Louise G. Trubek wrote, "Can we still be arguing about a woman's ability to control her own fertility?" How is your book a response to that sort of attitude? Do we really need to being arguing over contraceptives? Isn't that a matter of private choice and personal preference?

Mary Eberstadt: It is indeed fascinating that America is arguing over contraceptives. But pace certain retired law professors, the deeper meaning of that argument is not what the fear-mongers say it is. Torquemada 2.0 is not about to go slinking into college dormitories, filching pills and condoms from cowering college students. That's not what this argument is about.

The argument is instead over something much larger. In the short term, as many have pointed out, and in the specific matter of the HHS mandate, it is indeed an argument over religious freedom. Many capable people, starting with certain other law professors and including the US bishops, have explained the dispute over the HHS mandate clearly and well.

Beyond that, though, there is an even wider meaning to the manifest unease over these issues that everyone thought settled. That is the legacy of the sexual revolution, whose consequences in one realm after another are only beginning to be understood. As the founder of Harvard's sociology department, Pitirim Sorokin, once observed, it is a revolution that in the long run may have more influence on the world than any other—and we're only beginning to understand it.

In that sense—and in a way that the sexual liberationists and their allies really don't get—it doesn't matter where you stand on the matter of religion. You could be a Wiccan. You could be a Carmelite. You could be Lady Gaga's biggest fan. No matter what, you are still affected by the sexual revolution in more ways than can be counted—economically, politically, personally, and otherwise, for reasons I try to explain in the book.

I'm just pointing out that to say the sexual revolution amounts to a "woman thing" is absurd. And this is true leaving aside the question of morality altogether. One way or another, regardless of where individuals stand, the Western world and the rest of the world will have to grapple with the legacy of the revolution—and not just now, but centuries from now. Reducing this enormous phenomenon to something personal, a mere matter of women's prerogatives, is just that: indefensibly reductionist.

CWR: Why do so many people—especially (but not only) those secular elites who dress themselves in the cloaks of science and reason—either ignore or deny outright both the statistical and anecdotal evidence demonstrating the serious personal and social damage wrought by the sexual revolution?

Prayer. Statements. Ecumenism. Contraceptotalitarians. Dances. Details. More.

Recent posts on the Catholic World Report blog:

• Pope's audience focuses on Mary's prayers, role of prayer in the early Church

• New USCCB statement clarifies what the HHS debate is--and isn't--about

• Pope Benedict XVI knows ecumenism. Who knew?

• The upside Dowd world of liberated contraceptotalitarians

• Dionne's dutiful dance and those devilish details

• Evangelicals and Catholics Together, defending religious freedom

• Study: Britain will be an atheist nation by 2030

• Details of Abby Johnson's lawsuit against Planned Parenthood made public

• And Much More!

March 14, 2012

"Well, you could have been hardly more anti-Nazi than the Ratzinger family."

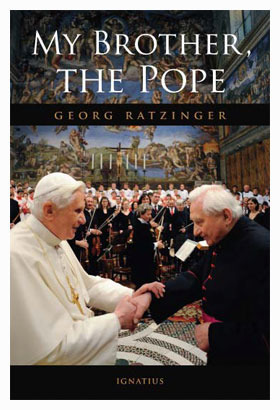

From an interview with German journalist Hesemann, who recorded and edited the material that makes up My Brother, the Pope (also available in e-book format), in today's edition of National Catholic Register:

In the past, we have experienced various attempts to reduce Pope Benedict's past to the Nazi era. How does this book help to address that mischaracterization of the Ratzinger family's values and activities during that era?

Well, you could have been hardly more anti-Nazi than the Ratzinger family. The Pope's father was a small-town policeman when he stopped Nazi rallies and ended Nazi Party meetings, so the Nazis complained about him, and he was advised to  request removal to a village — which he did, although it was a step down the career ladder. He hated them; he called Hitler "the Antichrist." He couldn't wait for his retirement, since he did not want to serve the Nazi regime, and, of course, he never joined the Nazi Party.

request removal to a village — which he did, although it was a step down the career ladder. He hated them; he called Hitler "the Antichrist." He couldn't wait for his retirement, since he did not want to serve the Nazi regime, and, of course, he never joined the Nazi Party.

Instead, he was a subscriber to the most outspoken Catholic anti-Nazi Newspaper, Der gerade Weg, whose editor in chief, Fritz Gerlich, was murdered by the Nazis just after they came to power. After Hitler's election, Joseph Ratzinger Sr. told his family frankly and nearly prophetically: "Soon we will have a war, so let's buy a house" — which they did.

Indeed, the decision of both brothers to join the seminary was also a protest against the Nazis, and you can just imagine how seminarians were mocked by the Nazi boys of their age. Although it was the law to join the Hitler Youth and the whole class was automatically enlisted, young Joseph Ratzinger avoided it. He frankly told his school teacher he did not want to go, and, eventually, the teacher allowed him to stay at home. Even their older sister, Maria Ratzinger, who was an intelligent young lady and dreamed of becoming a school teacher for all her childhood, refused to study when the Nazis came to power and became a lawyer's secretary instead: She just did not want to teach Nazi ideology at a Nazi school.

There were a few good Catholics in Germany, even during the Nazi regime — people who suffered a lot, and the Ratzingers were among them.

Read the entire interview, which is really interesting. For more about My Brother the Pope, visit the book's website.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers