Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 226

April 9, 2012

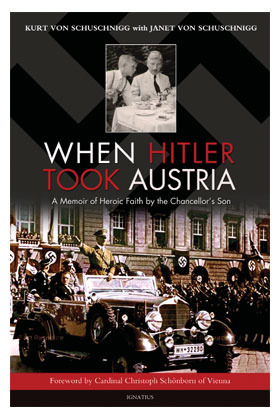

"'When Hitler Took Austria' outclasses a great number of its peers within the genre."

Jeff Emanuel has reviewed, at length, the recently released book, When Hitler Took Austria: A Memoir of Heroic Faith by the Chancellor's Son, co-authored by Kurt and Janet von Schuschnigg. Emanuel writes that the book

shines a bright light on the events of the late 1930s in Austria from a very particular point of view: that of a chancellor's son who came of age during the events he is recounting. As may be expected, a significant portion of this memoir  focuses on the author's father, Kurt von Schuschnigg the elder, both as Chancellor of Austria prior to the German invasion (1934–1938) and as a prisoner of Hitler's government. The recollections in the book as a whole, and in the pre-Anschluss portion in particular, are made up of a precise intertwining of history and personal memory, and the result is a narrative that is as intellectually informative as it is personally engaging. Von Schuschnigg sets his own youthful exploits and learning experiences against the backdrop of serious situations and events that his father and his country faced in the run-up to WWII, from Austria's long and painful climb back from the economic knockout punch delivered it after the first world war to the desperate attempts by the chancellor to keep his nation independent and secure in the face of the growing Nazi threat across the German border and at home.

focuses on the author's father, Kurt von Schuschnigg the elder, both as Chancellor of Austria prior to the German invasion (1934–1938) and as a prisoner of Hitler's government. The recollections in the book as a whole, and in the pre-Anschluss portion in particular, are made up of a precise intertwining of history and personal memory, and the result is a narrative that is as intellectually informative as it is personally engaging. Von Schuschnigg sets his own youthful exploits and learning experiences against the backdrop of serious situations and events that his father and his country faced in the run-up to WWII, from Austria's long and painful climb back from the economic knockout punch delivered it after the first world war to the desperate attempts by the chancellor to keep his nation independent and secure in the face of the growing Nazi threat across the German border and at home.

And, later, he states:

A FAST-PACED, ENGAGING memoir that clearly communicates the author's strength and suffering (both physical and mental) at Hitler's tyrannical hands, When Hitler Took Austria outclasses a great number of its peers within the genre. The book is well-written, thanks in no small part to the narrator's wife (and titular co-author) Janet,* who took on the large task of writing down her husband's recollections, and whose first-person writing in the preface and acknowledgments should not be confused with the first-person narrative of the book itself. Further, its unique point of view and informative personal anecdotes make it a must-read for those interested in run-up to the war in Europe, as does its focus on events in Austria, a country whose story rarely receives the attention it deserves, perhaps due to the Austro-Hungarian role in WWI. Whatever the reason, When Hitler Took Austria makes up for a deficit of information and recognition on two fronts. The first is the story of Austria in the years before WWII, which has received precious little attention from the general public. The second, of a far less ephemeral nature, is the recognition this book provides for overworked and underappreciated guardian angels everywhere, without whom neither the author nor his family would have survived a fraction of the encounters recounted in this excellent book. [*Janet von Schuschnigg née Cook is also my lovely wife's aunt.]

Read the entire review on Emanuel's website. When Hitler Took Austria is also available in Electronic Book Format.

The Catholic faith is centered, undoubtedly, on the Resurrected Lord of all, ...

... Jesus Christ, Christus Victor! By no means could we ever hope to comprehend this mystery as the climactic point of human history; yet, we can apprehend something meaningful about it. Because we cannot wrap our minds around this mystery, we are instead forced to think about it from different perspectives. There is no single dimension of the Resurrection that can provide us with a comprehensive understanding. What follows are some different ways in which the central mystery of our faith is related to Catholic discipleship and common theological understandings. Ideas have consequences. Beliefs affect behavior; doctrine helps to determine devotion. It is my hope and prayer that we will be more conscious of Easter Sunday throughout the liturgical year. Let us now turn to Christ's Resurrection, and its relevance for all of our beliefs and practices as Catholics.

Easter and Theology

First, the Resurrection is a necessary prolegomenon (the study of the preconditions which make theology possible) for the Christian faith. While it is true that "we believe in order to understand," it is equally true to say that "the more we authentically understand, the more disposed we are to have faith." Genuine knowledge can be used by God as a springboard for Catholic faith. Whether one wishes to theologize on the Resurrection as an act of forgiveness, or as the commencement of the new future, or as the establishment of the Apostles' proclamation, none of these are possible if Jesus' body still remains in the tomb (cf. 1 Cor 15:12-19). That is why we need to defend the historicity of the Resurrection in order to make theology a genuine possibility.

The apologists' concerns also act as a call to reinvigorate what the late Cardinal Avery Dulles has called the "herald model of the church." The case for Christ's Resurrection can be just one means through which the saints can become equipped to become confident in verbally sharing their faith (cf. Eph. 6:19; Col. 4:5, 6; 1 Pet. 3:15; Jude 3). Apologetics reminds us of why we believe, and in whom we believe. Building confidence might help believers to share the things we believe with others, and to face the suffering that is often accompanied by these exchanges. By having good reasons for faith, we know that whom we believe can be backed with legitimate evidence.

The Resurrection appearances of Jesus from the dead are closely linked to the Church's mission (thus the branch of theology known as "missiology") to spread the good news.

Continue reading the Homiletic & Pastoral Review essay, "Christ's Resurrection and Theological Relevance", by Glenn B. Siniscalchi.

"Together Behind Locked Doors": On resurrection, abortion, and judgment

by Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

"On the morning of the first day of the week, the disciples were gathered together behind locked doors, suddenly, Jesus stood among them and said: 'Peace be with you,' alleluia."

— Antiphon, Evening Prayer, Easter Sunday.

I.

In the twelfth chapter of the twenty-second book of the City of God, St. Augustine gives us a remarkably up-to-date objection to the resurrection of the body, one that might be of rather unsettling concern to many of our contemporaries. "It is the habit of the pagans to subject our belief in a bodily resurrection to a scrupulous examination and to ridicule it with such questions as, 'What about abortions?'" Augustine tells us. "'Will they rise again?' … Now we are not going to say that those infants (who die early) will not rise again: for they are capable not only of being born, but also of being reborn." All persons capable of being born are capable of being reborn.

The fact that a significant percentage of the actual human race, though conceived, are not born, does not mean those unborn do not have the same destiny and purpose of those born. The pagan assumption is, of course, that, while those once born may perhaps rise again, surely not those who were never born but were instead aborted. In our time, the number of those who were not born but aborted, on a world wide scale, is simply staggering—around forty to fifty million a year at a minimum. Yet, these too participate in the same end designed for all of us.

Contemporary pagans and others usually do not give aborted infants the honor even of worrying themselves about the final status of such infants. Or of considering their final status as participators, directly or indirectly, in decisions and actions that terminate actual lives. But it is quite clear in this regard that the eternal status of aborted children is not a frivolous issue if their claim to humanness is as solid as that of anyone else, which it is.

II.

Why bring up at this time the same issue of aborted children brought up by the pagans in Augustine's time? It is standard biological and Church teaching, on the basis of evidence, that an individual human life begins at conception. However lightly we want to dance around this fact, it remains true. Everyone who ever came forth out of the womb had his beginning in the union of a male and female element. This new life is not "part" of the mother, nor is it unnatural to her body. That is where it belongs.

Moreover, aborted babies and babies who die in the womb before birth have the same destiny as the mother who carries them and the father who begot them. What it is to be a human being begins here. Mortal life ends with death, whenever that occurs, be it by abortion at five months, be it by miscarriage at six months, be it by sickness at three years, heart attack at thirty, or Parkinson's disease at ninety-five.

Now none of these human beings, however or whenever his death might occur, is caused solely by his parents or by himself. The ultimate origin of each human person is within the Godhead itself, within the Trinity. Our initial origin is in the image of God in which our very possibility must first exist. This origin too is why we are all related to one another in our very being. To be a person is to be related to others. Our dependence on one another is based on trues of one another. And this trust must be freely accepted. In this sense, all abortions are a violation of a truest that is ultimately rooted in that Trinitarian life in which we are to participate in God's grace.

III.

Easter is our central feast, our fundamental doctrine. "If Christ be not risen," Paul says, "our faith is in vain." We grant that logic. That Christ rose from the dead is known to us because the fact of it was observed by certain definite witnesses. They did not invent what they saw, but, with some astonishment, reported what they went on. They were neither liars nor ideologues. They were not wishful thinkers or deluded mystics. Hard headed fishermen and a tax collector, among others, were among them. Many of them died for their testimony.

But when the Apostles were gathered together behind closed doors, they were in fact being cautious. What they were claiming in public was in its day not "politically correct." They were testifying to the fact of the resurrection of Christ. Christ did not break down the doors to lead them out on a triumphant, overwhelming conquest. Rather, He appeared among them. He told them to be at peace. I bring this Easter passage up to remind us that even the aborted children are at peace. Even if their lives were unjustly cut off, God's grace is sufficient for them to reach the end for which they were initially created as images of God.

The real drama of the aborted babies of our time, or any other time, concerns rather those who aborted them. To remind our contemporaries of their responsibility in this area is perhaps one often reasons that Benedict XVI speaks so often and so earnestly of final judgment. No human act is finally complete unless and until it is judged. Everything is done to keep the reality of abortions, what is actually done, from our eyes. They are in fact "behind closed doors." But they bring no peace unless they are repented, and even then they unsettle our souls with the knowledge that members of our kind could justify such things.

And yet, Christ's resurrection is an assurance that each of us, including those whose lives we cut short, will rise again, first to judgment. The assurance of that fact is this: When Christ appeared to the frightened Apostles after the resurrection, He told them that His peace was with them. Easter is indeed the Day the Lord hath made. This is why we can rejoice and be glad. It is not because whatever we do, including killing our kind as infants, makes no difference, but because it does matter. The peace follows the judgment of how we receive the give of the image of God in which we are all, from conception to death, created.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

He is the author of numerous books on social issues, spirituality, culture, and literature including Another Sort of Learning, Idylls and Rambles, A Student's Guide to Liberal Learning, The Life of the Mind (ISI, 2006), The Sum Total of Human Happiness (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), The Regensburg Lecture (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), and The Mind That Is Catholic: Philosophical and Political Essays (CUA, 2008). His most recent book from Ignatius Press is The Order of Things(Ignatius Press, 2007).

His new book, The Modern Age, is available from St. Augustine's Press. Read more of his essays on his website.

April 7, 2012

The Resurrection of Christ: Four Flawed Theories and the Glorious Truth

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, April 8, 2012, The Solemnity of Easter, the Resurrection of the Lord

It is something of a tradition for magazines and newspapers to run articles about the death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ in the weeks leading up to Easter. Scholars, pastors, skeptics, and ordinary people weigh in with their arguments and opinions. Some argue the Resurrection never took place. Down  through time there have been a number of arguments made about what really happened on that Sunday some two thousand years ago. Peter Kreeft and Fr. Ronald Tacelli, in Handbook of Catholic Apologetics, outline the four basic theories used to explain away the Resurrection.

through time there have been a number of arguments made about what really happened on that Sunday some two thousand years ago. Peter Kreeft and Fr. Ronald Tacelli, in Handbook of Catholic Apologetics, outline the four basic theories used to explain away the Resurrection.

The first is that a conspiracy existed to misrepresent what transpired in the aftermath of Jesus' death. The most ancient variation of this argument was concocted by the chief priests upon discovering the empty tomb: the body of Jesus was stolen by his disciples (Matt 28:11-15).

The second is that the apostles and other disciples—nearly mad with grief and deeply confused—experienced the world's most dramatic group hallucination. Convinced that they had seen and experienced the impossible, they set out to convince the world of the same.

Another argument—the "swoon theory"—is that Jesus, tortured and exhausted, had not died, but had only passed out for a time until he was revived by his followers.

The final argument, which has a loyal following in different forms among atheists, skeptics, and theologically liberal Christians, is that the Resurrection is a myth. Some insist this does away with the meaning of the Resurrection, while others insist this actually provides a deeper, metaphorical meaning.

There are, of course, many problems with each of these theories. For example, how exactly would a group of frightened fisherman overwhelm Roman guards and move away a huge stone? And why would they, only weeks later, fearlessly proclaim Christ's Resurrection and then, over the years, accept martyrdom, despite knowing Jesus was actually dead? How is it that hundreds of people (cf., 1 Cor 15:3-8) experienced the same hallucination? How would Jesus, who was ripped to shreds and crucified by trained killers, appear shortly thereafter as physically whole, even glorious in appearance (Jn 20:19-29)?

But it is the theory of the mythical or metaphorical Resurrection that is most disconcerting, especially when embraced by Christians. In today's reading from Acts, Peter is described stating bluntly, "They put him to death by hanging him on a tree. This man God raised on the third day and granted that he be visible, not to all the people, but to us." The story of doubting Thomas (Jn. 20:19-29) soundly rejects any such understanding. And today's Gospel readings all describe real confusion on the part of the disciples and the fact that this confusion was due to a physical Resurrection. "Do not be amazed!" the angel told the women, "You seek Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified. He has been raised; he is not here" (Mk 16:5-6).

The story of the two disciples journeying to Emmaus (Lk 24:13-35) emphasizes how belief in the Resurrection is not, in the end, a matter of mere reason or facts, but of a real encounter with the Risen Lord. Having walked and talked at length with Jesus, they still did not recognize him. But when he took break and blessed it and gave it to them—that is, when Jesus gave them Eucharist—their "eyes were opened and they recognized him."

"The basic form of Christian faith," Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger wrote in Faith and the Future (Ignatius, 2009), "is not: I believe something, but I believe you." It's not that faith is unreasonable; rather, it is finally, in the end, above and beyond reason, although never contrary to reason.

It is ultimately an act of will and love. "We believe, because we love," wrote John Henry Newman in a sermon titled, "Love the Safeguard of Faith against Superstition." "The divinely-enlightened mind sees in Christ the very Object whom it desires to love and worship,—the Object correlative of its own affections; and it trusts Him, or believes, from loving Him."

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in a slightly different form in the April 12, 2009, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

April 6, 2012

Great and Holy Friday

The burial icon/shroud, or Epitaphios, at our parish, Nativity of the Mother of God Ukrainian Catholic Church:

"In the Cross man encounters a love not of this world."

From the essay, "Love Alone is Believable: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Apologetics" by Monsignor John R. Cihak:

The Father, Son and Holy Spirit have revealed themselves as one God in order to liberate man and bring him to live within the divine life of the Trinity. Man could never anticipate God's astounding initiative in reaching out to save him.

The Form of the Cross

The pinnacle of this revelation, which Balthasar calls the "Christform", is Jesus nailed to the Cross. One may object, "How can the crucifixion of Jesus be the preeminent revelation of Beauty?" In the ugliest place of human existence (crucifixion and death) God reveals himself as absolute, total self-giving love. The Trinity is self-giving love. Being disguised under the disfigurement of an ugly crucifixion and death, the Christform is paradoxically the clearest revelation of who God is. This love can only be fully revealed in a world corrupted by sin through death, the ultimate expression of self-giving in this world.

And so this is the supreme moment of transcending beauty, a revelation of love visible in the world, yet pointing to a love beyond this world. As St. John so profoundly grasps in his Gospel, the concealment of the Son under the form of the Cross is his glory because it reveals a love to the absolute end. The glory of the Son does not come after the Cross. The Cross is his glory. Even in this ultimate form of beauty in self-giving love, God does not overwhelm human freedom. No one is forced to believe that this crucified man is the divine Son of God saving the world.

As in the aesthetical encounter, the form is Jesus nailed to the Cross. One must decipher the Christform which stands in history as a concrete sign (species). Anyone can stand before it and wonder, "Who is this?" God has disturbed history forever with his provocative sign of love. The perception of faith, however, is beyond the ability of man alone. What is required is a new light. Without this light man cannot see the depths of the form. In other words, the non-believer looks at the Cross and says, "I see just a man." God must awaken in man the capacity to recognize him.

The splendor (lumen) emanating from the form is the glory of the Lord containing divine grace. This glory strikes the non-believer (vision) pulling him into the form and enabling him to believe (rapture). He is pulled into its depths, not simply for an encounter with absolute Being, but into a personal relationship with the tri-personal God (who is also absolute Being). The act of faith is to be swept up into the form of the Triune God's self-revelation in Jesus of Nazareth through the splendor of divine grace. The non-believer is seduced by the form.

Divine grace, working in the interior of the person, allows him to see the form for what it is. Only grace enables him to organize the evidence for belief into a coherent whole and see what the sign reveals. As in beauty, to share in the revelation of divine love, one must renounce himself and surrender to the grace offered. Furthermore, one does not "get behind" the form of the Cross in order to then see God. Rather the Trinity is revealed in the Cross. Jesus said to Philip, "He who has seen me has seen the Father" (John 14:9). When the non-believer encounters Christ crucified, an historical event situated in time and space, he can be pulled into that form, by assenting to the grace offered, for an encounter with the Triune God.

In the Cross man encounters a love not of this world. Man sees "that the love offered him is quite unlike anything he knows as love; and that the scandal [of God's love] exists in order to make him see the uniqueness of this new love -- and by its light to reveal and lay bare to him his own love for what it is, lack of love" (LA). The non-believer asks, "With my broken love, and my life hurtling toward death, is there anything worthy of my belief?" Jesus of Nazareth is the unique sign, expressive of a persuasive love which draws the beholder into the same dynamic of love. In the act of faith, as in the encounter with beauty, one is marked by the beautiful form. The Father impresses his form on the Son, and the Son, through the Holy Spirit, presses his form on the believer. The person's own life is to take on the dimensions of the Christform. He is not to be a bystander but a participant in this dynamic of divine love.

The credibility of the revelation comes through the Christform, from which breaks forth the pulsating, burning furnace of Trinitarian love. This sign needs no other proofs. It is the proof of love. In the encounter of faith, the non-believer realizes that this revelation not only unites the fragments of truth in the world, not only gives meaning to mankind at its deepest level, but that it pulls him beyond into the very life of God encountering a love beyond his capacity to imagine. Finally, one finds a love worthy of his faith, of his very life. This is a love that is believable.

• Read the entire essay on Ignatius Insight.

Pope Benedict's headline-grabbing rebuke of disobedient priests...

... is analyzed by Catherine Harmon, managing editor of Catholic World Report, on the CWR blog.

"The mere forgiveness of God would not affect us in our alienation from God. ..."

... Man must be represented in the making of the new treaty of peace, the "new and eternal covenant". He is represented because we have been taken over by the man Jesus Christ. When he "signs" this treaty in advance in the name of all of us, it suffices if we add our name under his now or, at the latest, when we die.

Of course, it would be meaningless to speak of the Cross without considering the other side, the Resurrection of the Crucified. "If Christ has not risen, then our preaching is nothing and also your faith is nothing; you are still in your sins and also those who have fallen asleep . . . are lost. If we are merely people who have put their whole hope in Christ in this life, then we are the most pitiful of all men" (I Cor 15:14, 17-19).

If one does away with the fact of the Resurrection, one also does away with the Cross, for both stand and fall together, and one would then have to find a new center for the whole message of the gospel. What would come to occupy this center is at best a mild father-god who is not affected by the terrible injustice in the world, or man in his morality and hope who must take care of his own redemption: "atheism in Christianity".

— from A Short Primer For Unsettled Laymen by Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar. Read more here:

The Cross: The Mystery at the Center of Our Faith

The Mystery at the Center of Our Faith | Hans Urs von Balthasar | The Introduction to To the Heart of the Mystery of Redemption | Ignatius Insight

All over the world, the best young people are seeking God. They would like to discover the paths where they can meet him, where they can experience him, where they can be challenged by him. They are tired of sociological and psychological expedients, of all the banal substitutes for the truly miraculous. In order to respond to their desire—which corresponds, moreover, to that of true Christians of all ages—let us not delay: let us be spiritual men who live and know how to hand on the extraordinary mystery that is at the center of our faith, the mystery without which all Christianity becomes trivial and, thereby, ineffective.

In order to respond to their desire—which corresponds, moreover, to that of true Christians of all ages—let us not delay: let us be spiritual men who live and know how to hand on the extraordinary mystery that is at the center of our faith, the mystery without which all Christianity becomes trivial and, thereby, ineffective.

At the center of our faith: the Cross

"For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified" (1 Cor 2:2): there you have Paul's plan of action. Why? Because the entire Credo of the early Church was focused on the interpretation of the appalling end of Jesus, of the Cross, as having been brought about pro nobis, for us; Paul even says: for each one of us, thus, for me.

"The life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me" (Gal 2:20).

What effect can such an act of love have? Is it a manifestation of solidarity? But if I suffer from cancer, what good does it do me if someone else lets himself be stricken by the same illness in order to keep me company? In order to understand the original faith, we must certainly go beyond the simple concept of solidarity.

For the early Church, this "going beyond" was justified after the experience of the Resurrection. Far from being a private event in the history of Jesus, it is the attestation on God's part that this crucified Jesus is truly the advent of the kingdom of God, of the pardon offaults, of the justification of the sinner, of filial adoption.

Well, then, what did happen on the Cross?

The ancient Roman liturgy speaks of a sacrum commercium, or admirabile commercium, of a mysterious exchange that Saint Paul expresses by these words: "[If] one has died for all, therefore all have died" (2 Cor 5:13), which obviously means: if a single one has the competence and the authorization to die for all, that creates an objective fact that affects them all. Consequently, Paul can continue: "And he died for all, that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised" (2 Cor 5:15).

Four aspects of the mystery

Here we are before a mystery that is usually referred to as redemption. Let us not dwell on questions of terminology. It is clear that, if this Christian mystery is a reality, it is absolutely unique. Consequently, no concept drawn from common experience will be able to exhaust it.

This is what Saint Thomas has demonstrated superlatively in his Christology by aligning four concepts that all capture one aspect of the mystery but that all also need to be surpassed and that are all mutually complementary. Here they are, all indispensable, each by itself insufficient: merit, satisfaction, sacrifice, redemption (or atonement).

We will come back to this. Let us say briefly in advance that all have their references in Scripture, in the Fathers, and in the great theologians. Scripture seems to advocate sacrificial vocabulary (Letter to the Hebrews); the Fathers, atonement/ redemption; Saint Anselm, satisfaction; Saint Thomas, merit, while stressing the interpenetration of the four aspects.

The shortcomings are also immediately apparent:

Sacrifice comes from the Old Testament and nonbiblical religions; now Christ, at once priest and victim, transcends this stage of relations with God.

Atonement/redemption is a vivid image; but from whom would Christ be redeeming us? Not from the devil, who cannot have true rights over sinners; not from God the Father and his justice or his anger, since it is precisely the Father who in his love for the world has handed over his Son to us.

Satisfaction: in one sense, yes: for us who are incapable of reconciling ourselves with God, Christ effectively works this reconciliation, and Scripture instills in us the idea that at the Cross it was not merely a question of a symbol by which God demonstrated that he was already reconciled. But what event in this world could influence God? Change his attitude toward the world? That seems metaphysically impossible.

Finally, merit, supereminently: because, according to Anselm and Thomas, the person who suffers is divine and since he is through his Incarnation the Head of the Body of mankind. But is this merit enough to account for theexchange between Christ and us?

It thus seems that none of the concepts exhausts the mystery. And that is just what we would have to expect.

How, then, shall we proceed?

------

1. First of all, we are going to say a word about the relation in the Gospel between the earthly Jesus going to his death and the risen Christ as he appears in the faith of the early Christians.

2. It will then be necessary to confront the formidable problem—evangelical and theological at the same time—of the relation between the wrath of God (orge) and his mercy, in other words, the problem of the beloved Son handed over to sinners by God the Father.

3. Finally, a word about the theories of redemption, in particular that of Anselm, which was the classic one until thirty years ago but nearly unanimously abandoned since.

And as a final word, we will make a very brief reflection on the possibility of proclaiming the mystery of the Cross today.

To the Heart of the Mystery of Redemption

by Hans Urs von Balthasar and Adrienne von Speyr

Preface by Henri Cardinal de Lubac | Postscript and foreword by Jacques Servais, S.J.

In the 1960's, Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar gave two conferences in Paris on the subject of redemption. One considered the perspective of Christ the Redeemer. The other gave a view of the redemption from the perspective of Mary and the Church, consenting to the sacrifice of Jesus. These two conferences are what Fr. Jacques Servais, S.J., in his foreword calls "a lantern of the Word", shedding light amidst the advancing turmoil of the postconciliar period.

These conferences were later collected by the eminent theologian Henri Cardinal de Lubac, S.J., in a single volume along with an anthology of meditations on the Passion by the mystic Adrienne von Speyr, and selected by von Balthasar.

In this new edition, prepared for the centenary of the birth of Hans Urs von Balthasar, Fr. Servais, the director of Casa Balthasar in Rome, provides an extensive postscript illuminating the text along with the original preface by de Lubac.

"I had the joy of knowing and associating with this renowned Swiss theologian. I am convinced that his theological reflections preserve their freshness and profound relevance undiminished to this day and that they incite many others to penetrate ever further into the depths of the mystery of the Faith, with such an authoritative guide leading them by the hand." -- Pope Benedict XVI

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Book Excerpts:

• The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Cross--For Us | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Introduction | From Adrienne von Speyr's The Book of All Saints

• The Conquest of the Bride | From Heart of the World

• Jesus Is Catholic | From In The Fullness of Faith: On the Centrality of the Distinctively Catholic

• A Résumé of My Thought | From Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Work

• Church Authority and the Petrine Element | From In The Fullness of Faith: On the Centrality of the Distinctively Catholic

• The Cross–For Us | From A Short Primer For Unsettled Laymen

• A Theology of Anxiety? | The Introduction to The Christian and Anxiety

• "Conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary" | From Credo: Meditations on the Apostles' Creed

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. Incredibly prolific and diverse, he wrote over one hundred books and hundreds of articles. Read more about his life and work in the Author's Pages section of IgnatiusInsight.com.

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. Incredibly prolific and diverse, he wrote over one hundred books and hundreds of articles. Read more about his life and work in the Author's Pages section of IgnatiusInsight.com.

The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross

The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

An excerpt from God and the World: A Conversation with Peter Seewald (Ignatius Press, 2002), by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, pages 332-36, 333.

Seewald: We are used to thinking of suffering as something we try to avoid at all costs. And there is nothing that many societies get more angry about than the Christian idea that one should bear with pain, should endure suffering, should even sometimes give oneself up to it, in order thereby to overcome it. "Suffering", John Paul II believes, "is a part of the mystery of being human." Why is this?  Cardinal Ratzinger:Today what people have in view is eliminating suffering from the world. For the individual, that means avoiding pain and suffering in whatever way. Yet we must also see that it is in this very way that the world becomes very hard and very cold. Pain is part of being human. Anyone who really wanted to get rid of suffering would have to get rid of love before anything else, because there can be no love without suffering, because it always demands an element of self-sacrifice, because, given temperamental differences and the drama of situations, it will always bring with it renunciation and pain.

Cardinal Ratzinger:Today what people have in view is eliminating suffering from the world. For the individual, that means avoiding pain and suffering in whatever way. Yet we must also see that it is in this very way that the world becomes very hard and very cold. Pain is part of being human. Anyone who really wanted to get rid of suffering would have to get rid of love before anything else, because there can be no love without suffering, because it always demands an element of self-sacrifice, because, given temperamental differences and the drama of situations, it will always bring with it renunciation and pain.

When we know that the way of love–this exodus, this going out of oneself–is the true way by which man becomes human, then we also understand that suffering is the process through which we mature. Anyone who has inwardly accepted suffering becomes more mature and more understanding of others, becomes more human. Anyone who has consistently avoided suffering does not understand other people; he becomes hard and selfish.

Love itself is a passion, something we endure. In love experience first a happiness, a general feeling of happiness.

Yet on the other hand, I am taken out of my comfortable tranquility and have to let myself be reshaped. If we say that suffering is the inner side of love, we then also understand it is so important to learn how to suffer–and why, conversely, the avoidance of suffering renders someone unfit to cope with life. He would be left with an existential emptiness, which could then only be combined with bitterness, with rejection and no longer with any inner acceptance or progress toward maturity.

Seewald: What would actually have happened if Christ had not appeared and if he had not died on the tree of the Cross? Would the world long since have come to ruin without him?

Cardinal Ratzinger: That we cannot say. Yet we can say that man would have no access to God. He would then only be able to relate to God in occasional fragmentary attempts. And, in the end, he would not know who or what God actually is.

Something of the light of God shines through in the great religions of the world, of course, and yet they remain a matter of fragments and questions. But if the question about God finds no answer, if the road to him is blocked, if there is no forgiveness, which can only come with the authority of God himself, then human life is nothing but a meaningless experiment. Thus, God himself has parted the clouds at a certain point. He has turned on the light and has shown us the way that is the truth, that makes it possible for us to live and that is life itself.

Seewald: Someone like Jesus inevitably attracts an enormous amount of attention and would be bound to offend any society. At the time of his appearance, the prophet from Nazareth was not only cheered, but also mocked and persecuted. The representatives of the established order saw in Jesus' teaching and his person a serious threat to their power, and Pharisees and high priests began to seek to take his life. At the same time, the Passion was obviously part and parcel of his message, since Christ himself began to prepare his disciples for his suffering and death. In two days, he declared at the beginning of the feast of Passover, "the Son of Man will be betrayed and crucified."

Cardinal Ratzinger: Jesus is adjusting the ideas of the disciples to the fact that the Messiah is not appearing as the Savior or the glorious powerful hero to restore the renown of Israel as a powerful state, as of old. He doesn't even call himself Messiah, but Son of Man. His way, quite to the contrary, lies in powerlessness and in suffering death, betrayed to the heathen, as he says, and brought by the heathen to the Cross. The disciples would have to learn that the kingdom of God comes into the world in that way, and in no other.

Seewald: A world-famous picture by Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper, shows Jesus' farewell meal in the circle of his twelve apostles. On that evening, Jesus first of all throws them all into terror and confusion by indicating that he will be the victim of betrayal. After that he founds the holy Eucharist, which from that point onward has been performed by Christians day after day for two thousand years.

"During the meal," we read in the Gospel, "Jesus took the bread and spoke the blessing; then he broke the bread, shared it with the disciples, and said: Take and eat; this is my body. Then he took the cup, spoke the thanksgiving, and passed it to the disciples with the words: Drink of this, all of you; this is my blood, the blood of the New Covenant, which is shed for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in remembrance of me." These are presumably the sentences that have been most often pronounced in the entire history of the world up till now. They give the impression of a sacred formula.

Cardinal Ratzinger: They are a sacred formula. In any case, these are words that entirely fail to fit into any category of what would be usual, what could be expected or premeditated. They are enormously rich in meaning and enormously profound. If you want to get to know Christ, you can get to know him best by meditating on these words, and by getting to know the context of these words, which have become a sacrament, by joining in the celebration. The institution of the Eucharist represents the sum total of what Christ Is.

Here Jesus takes up the essential threads of the Old Testament. Thereby he relies on the institution of the Old Covenant, on Sinai, on one hand, thus making clear that what was begun on Sinai is now enacted anew: The Covenant that God made with men is now truly perfected. The Last Supper is the rite of institution of the New Covenant. In giving himself over to men, he creates a community of blood between God and man.

On the other hand, some words of the prophet Jeremiah are taken up here, proclaiming the New Covenant. Both strands of the Old Testament (Law and prophets) are amalgamated to create this unity and, at the same time, shaped into a sacramental action. The Cross is already anticipated in this. For when Christ gives his Body and his Blood, gives himself, then this assumes that he is really giving up his life. In that sense, these words are the inner act of the Cross, which occurs when God transforms this external violence against him into an act of self-donation to mankind.

And something else is anticipated here, the Resurrection. You cannot give anyone dead flesh, dead body to eat. Only because he is going to rise again are his Body and his Blood new. It is no longer cannibalism but union with the living, risen Christ that is happening here.

In these few words, as we see, lies a synthesis of the history of religion—of the history of Israel's faith, as well as of Jesus' own being and work, which finally becomes a sacrament and an abiding presence. ...

Seewald: The soldiers abuse Jesus in a way we can hardly imagine. All hatred, everything bestial in man, utterly abysmal, the most horrible things men can do to one another, is obviously unloaded onto this man.

Cardinal Ratzinger: Jesus stands for all victims of brute force. In the twentieth century itself we have seen again how inventive human cruelty can be; how cruelty, in the act of destroying the image of man in others, dishonors and destroys that image in itself. The fact that the Son of God took all this upon himself in exemplary manner, as the "Lamb of God", is bound to make us shudder at the cruelty of man, on one hand, and make us think carefully about ourselves, how far we are willing to stand by as cowardly or silent onlookers, or how far we share responsibility ourselves. On the other side, it is bound to transform us and to make us rejoice in God. He has put himself on the side of the innocent and the suffering and would like to see us standing there too.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• Author Page for Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI

• The Truth of the Resurrection | Excerpts from Introduction to Christianity | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• God Made Visible | A Review of On The Way to Jesus Christ | Justin Nickelsen

• A Shepherd Like No Other | Excerpt from Behold, God's Son! | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• A Jesus Worth Dying For | On the Foreword to Benedict XVI's Jesus of Nazareth | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Studying The Early Christians | The Introduction to We Look For the Kingdom: The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians | Carl J. Sommer

• The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians | An interview with Carl J. Sommer

Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, was for over two decades the Prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith under Pope John Paul II. He is a renowned theologian and author of numerous books. A mini-bio and full listing of his books published by Ignatius Press are available onhis IgnatiusInsight.com Author Page.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers