Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 175

January 2, 2013

Diarmaid MacCulloch "does not conceal his preference for secularism."

CWR's sister publication, Homiletic & Pastoral Review, has a number of new book reviews posted, including a lengthy review of Diarmaid MacCulloch's popular 2010 book, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. It is reviewed by Fr. Brian Van Hove, S.J., a regular contributor to both CWR and HPR. Fr. Van Hove begins:

According to Catholic tradition, faith is a gift. The author’s

cultural background is Low-Church or Evangelical Anglicanism. But this

is a heritage and not a theological virtue.

Diarmaid MacCulloch is professor of the History of the Church in the

theology faculty at St Cross College, Oxford. Professor MacCulloch

proclaims himself a skeptic, although he writes with the zeal of an

apostate. His is a paradoxical mixture of both skepticism and

appreciation of religion, especially Christianity. At times, he reveals

classical Greek tastes which are benevolently pre-Christian, though he

has been shaped by the Enlightenment. His erudition permits him to

indulge freely in refined, urbane scoffing. And his erudition is

considerable.

Why is this important? Because all writing emerges out of a tradition; 1

no author can be fully original. Perhaps, he could have written a

shorter work had he not considered the subject a formidable one. In over

a thousand pages, he writes about Christianity—not as a Christopher

Dawson (d. 1970), or a Paul Johnson, or a Hubert Jedin (d. 1980), or a

James Hitchcock, 2

who, each of them from within the subject, wrote histories of

Christianity and the Church. Nor are these religious historians ever

quoted. Anglican—especially Owen and Henry Chadwick—and various, and

often liberal, Christian historians—including Richard P. McBrien and

Hans Küng—do appear among the “Further Reading” selections, beginning on

page 1098. 3 John W. O’Malley, Eamon Duffy, and John McManners are a few of his more favored historians.

He says that Edward Gibbon, who wrote a celebrated Enlightenment-era history in seven volumes, 4 “had a fine eye for the absurdities and tragedies that result from the profession of religion.” 5

The author does not conceal his preference for secularism. One can say

that MacCulloch is a thoughtful, post-Enlightenment writer who knows

more about Christianity than most Christians, including the clergy. Yet

another reason for us to posit that faith is a gift, although we must

observe that, some without this gift, at times strenuously defend the

Church and the Christian tradition. 6

Read his entire review, along with several other reviews, at HPRweb.com. Fr. Van Hove's review of Dr. James Hitchcock's new book, History of the Catholic Church (Ignatius Press, 2012), will be published by CWR later this month.

January 1, 2013

On Being Human In a Civilization of Forgetfulness

On

Being Human In a Civilization of Forgetfulness | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | Catholic World Report

The

Pope understands that the wars of the world are still fought in the minds and

hearts of men.

“The

Church represents the memory of what it means to be human in the face of a

civilization of forgetfulness, which knows only itself and its own criteria.

Yet just as an individual without memory has lost his identity, so too a human

race without memory would lose its identity.”

— Pope

Benedict XVI,

Christmas Greetings to the Roman Curia, December 21, 2012.

“I would

say that the Christian can afford to be supremely confident, yes, fundamentally

certain that he can venture freely into the open sea of the truth, without

having to fear for his Christian identity. To be sure, we do not possess the

truth, the truth possesses us; Christ, who is the truth, has taken us by the

hand, and we know that his hand is holding us securely on the path of our quest

for knowledge.”

— Pope

Benedict XVI,

Christmas Greetings to the Roman Curia, December 21, 2012.

I.

Each year

the Holy Father gives a significant lecture to the Roman Curia about the events

of the previous year. In this year’s account, Benedict spent time recalling his

trips to Mexico, Cuba, and Lebanon. In the course of a year, the modern popes

probably see more important (and “unimportant”) people in the world than any

other public figure. Their trips to various countries are usually major events

in those countries. It is said that John Paul II was seen in person by more

human beings than any man in history.

In introducing

Pope Benedict, Cardinal Sodano recalled the liturgical antiphon: “Propre est

jam Dominus, venite adoremus–The Lord is near, come let us adore Him.” The

Child in the stable in Bethlehem, Benedict continues, “is God himself and has

come so close as to become a man like us.” Benedict never hesitates to identify

Christ as true God and true man. These very words—the “Child is God

Himself”—defy and challenge the whole world by affirming its truth.

Benedict

made a most interesting remark about Cuba: “That country’s search for a proper

balancing of the relationship between obligations and freedom cannot succeed

without reference to the basic criteria that mankind has discovered through

encounter with the God of Jesus Christ.” One presumes that, if that statement

is true for Cuba, it will be true for other lands, including our own.

Evidently, mankind has learned something about obligation and freedom from its

dealing with the reality of Christ. Essentially it is that no freedom exists

without corresponding obligation. Likewise, an obligation that is not freely

accepted is more like determinism or coercion than free responsibility.

II.

To the

Curia, Benedict devotes considerable discussion to two topics: the family and

the meaning of dialogue. The meeting on families in Milan gave the Holy Father

an opportunity to reflect on the nature of the family and the modern effort to

eliminate it as the central institution of human life.

December 30, 2012

Social Justice According to Pius XI

Social Justice According to Pius XI | Thomas Storck | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The term “social justice”… is the key term and concept of Catholic social teaching … with all the other aspects of the Church’s social doctrine—the principle of subsidiarity, the just wage or the right to private property—are related to, and rely, on the existence of social justice.

The term “social justice,” though common

enough today, is little understood by most of those who use it—whether

they consider themselves friends and practitioners of social justice, or

they regard it as a suspect term of probably socialist origin. But the

term does have a precise meaning. That meaning and the significance of

this concept of justice, were carefully explained by Pius XI, the

pontiff who introduced it into the corpus of Catholic social teaching.

In many respects it is the key term and concept of Catholic

social teaching. All the other aspects of the Church’s social

doctrine—such as the principle of subsidiarity, the just wage or the

right to private property—are related to social justice, and rely on the

existence of social justice. Pope Pius, who reigned from 1922 to 1939,

introduced the term into Catholic teaching in his encyclical, Studiorum Ducem (1923). He later made extensive use of it in two important social encyclicals: Quadragesimo Anno (1931) and Divini Redemptoris

(1937). But, before taking a close look at the exact meaning of social

justice, let us try to clear away some confusions over justice itself,

especially as contrasted with charity.

To illustrate the frequent confusion about the meaning of social

justice, and, indeed, about justice in general, one sometimes hears the

activity of working in a soup kitchen cited as an example of social

justice. However laudable such work is, it is not a work of

justice, social or otherwise, but rather one of charity. Thus, the

first distinction we must make is between “justice” and “charity.” What

is justice then? Thomas Aquinas takes as the settled definition of

justice that of the Roman jurists. 1

According to them, justice is “a perpetual and constant will of giving

to each one his right {jus}.” Plato had already referred to justice

under similar terms in the Republic (331e), attributing the

definition to Simonides, a poet who died ca. 468 B.C. As we will see,

there is more than one kind of justice, but common to all of them is

this notion of rendering what is due, i.e., of what someone has a right to. As Josef Pieper put it: “The hallmark of all…forms of justice is some kind of indebtedness….” 2

Charity, on the other hand, although it can be a duty binding on

someone, and even a duty toward a particular person, differs from

justice in that its “violation does not involve injury, in the technical

sense, and does not call for restitution or punishment.” 3

Often, duties of charity are not directed towards anyone in

particular. For example, my duty of charity to give away a certain

amount of my goods, while binding in conscience, does not oblige me to

give to any particular person. No one particular poor man ordinarily

has a claim on my charity.

The character of justice is easiest to see in the fundamental type of justice, commutative justice.

Atheist A.C. Grayling is a meretricious thinker, but a marvelous comedian

by Carl E. Olson | Catholic World Report blog

Here is the deep, philosophical question of the week: What is more annoying, insufferable, and unintentionally hilarious than the pontifications of atheist, "humanist", and "free thinker" A. C. Grayling?

Yes, I know, it's a tough one. I won't keep you in suspense.

Answer: The fawning, embarrassing adoration of an eighteen-year-old English student who interviews Grayling and acts as if the impressively maned Englishman's empty pontifications are rhetorical gold nuggets. That the interview is published in The Humanist is cause for the stones to cry out: "Oh, the inhumanity! Stop! Cease!"

But, to be honest, we can at least admit how fun it is to read this sort of nonsense and think, "And atheists think Christians are stupid? Goodness. I weep for them." No need to waste time with the entire train wreck of an interview, but a few pieces of broken thinking and confused stereotypes are worth kicking about for a moment. First, from the opening:

Philosophy is a rather strange business in the modern world of consumerism and commerce, I suppose. We’re so used to being force-fed ideas these days that we rarely, if ever, stop and think for ourselves.

Uh, speak for yourself, young man, speak for yourself.

And that’s where Grayling bucks the trend.

I think a gallon of coffee just shot out my nose. That is one of the funniest things I've read in a long time. Mind you, I've crossed cyber swords with Dr. Grayling in the past, over the matter of his ridiculous—nay, farcical—take on Christianity and the "Dark Ages". How shall I put this? Grayling isn't about bucking trends, but making bucks out of trends—in this case, the whole "new atheists" vehicle, to which he has hitched his modest bag of philosophical agitprop and public relations handles. A few years ago, an acquaintance who earned his doctorate in London and is now an atheist (we attended Bible college together 20 years ago as young Evangelicals), smirked at the mention of Grayling, saying, "He's all about fame and money." True enough.

But there is also the fact that Grayling acts as if his thinking is fresh and his perspective is daring, when both are actually decades out of dates. As I wrote six years ago: "He

is an heir to the Enlightenment and thrives on the sort of anti-Christian

polemics and dubious historical assertions that became the rage among many

intellectuals during the Enlightenment era, so much so that he seems to be

nearly entombed in a dusty (dare I say 'old-fashioned') form of simplistic skepticism

that was in style many decades ago." Carry on.

December 29, 2012

“Why were you looking for me?" (On the Feast of The Holy Family)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, December 30, 2012, the Feast of The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Sir 3:2-6, 12-14 or 1 Sm 1:20-22, 24-28

• Ps 128:1-2, 3, 4-5 or Ps 84:2-3, 5-6, 9-10

• Col 3:12-21 or 1 Jn 3:1-2, 21-24

• Lk 2:41-52

Being

lost isn’t always what it seems. People usually end up lost when they take a

wrong turn or misread directions. And then we sometimes speak of “losing

ourselves,” usually in some sort of pleasant diversion: reading a book,

watching a movie, or taking a walk in a familiar park or garden.

Yet

it takes a unique person and perspective to be lost without actually being lost

in order that those who seek you will not only find you, but will find you more

deeply and more truly. It takes

the twelve-year-old Incarnate Word to be lost in such a way. It is rather

humorous, in fact, to think that today’s Gospel reading, which is the only story

about the youthful Jesus between his first weeks of life and his adulthood, is

sometimes said to be about Mary and Joseph seeking the “lost” Jesus. Is he

lost?

To

them, yes, he is lost; they are as anxious as any parent (even a sinless

mother!) would be. But the young Jesus was not lost. He purposefully, St. Luke

writes, “remained behind in Jerusalem.” He had spent time in Jerusalem every

year; undoubtedly he had explored parts of the city and knew some it quite

well, especially around the Temple. And when he was found after three days of

frantic searching by Mary and Joseph, he did not express the relief of a

frightened child huddled in the woods. Rather, he matter-of-factly asked two

questions: “Why were you looking for me? Did you not know that I must be in my

Father’s house?”

As

Monsignor Ronald Knox observed in his Lightning Meditations (Sheed and Ward, 1959), these responses leave us

“puzzled, perhaps faintly disconcerted…” Surely the young man spoke with a

smile, Knox suggested, “otherwise the remark would be intolerably priggish.”

What

is clear is how difficult is the translating of Jesus’ words; they do not

directly refer to a “house,” but more obscurely to “the things of the Father.”

Knox muses that “the sight of Joseph hard at work makes him want to be a

carpenter already, at twelve; but then, the thought of his Heavenly Father,

tirelessly at work all the time, makes him impatient to begin his real

ministry…” After all, his words—“I must”—are as urgent as they are puzzling.

What was the work, the ministry, the things of the Father? A central part of it

was teaching, especially to teach “the teachers.” The Son of God, the author of

the Law, would both explain and fulfill the Law to the teachers of the Law.

This focus on teaching is especially emphasized as the Passion approaches: “And

he was teaching daily in the temple” (Lk 19:47; see 20:1; 21:37). After being

arrested, facing the chief priests and elders, Jesus stated, “When I was with

you day after day in the temple, you did not lay hands on me” (Lk. 22:53).

Sitting

in the midst of the teachers, Jesus taught by asking questions. This was,

Origen observed in a homily, befitting his youth. Jesus “interrogated the

teachers not to learn anything but to teach them by his questions,” he wrote,

“It is part of the same wisdom to know what you should ask and what you should

answer.” But Jesus also astounded the teachers, St. Luke writes, with “his

understanding and his answers.” Having come to seek and save the lost, he

revealed man’s need for the Messiah by both asking and proclaiming, prodding

and eliciting. “For the Son of man came,” he told Zacchae'us, “to seek and to

save the lost” (Lk 19:10).

When

Joseph and Mary spent three days seeking Jesus, they were being drawn deeper

into the mystery of salvation. They knew Jesus was the Messiah, but how could

they not be astonished that he was teaching the teachers? This required further

pondering, thought, contemplation. And so, also, for us. In seeking him, we

will not only find him, but will find that we are the ones who have been

found.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the December

27, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

On Writing a History of the Catholic Church

On Writing a History of the Catholic Church | James

Hitchcock | Catholic World Report

The Introduction to History of the Catholic Church: From the

Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium

The Catholic Church is the longest-enduring institution in

the world, and her historical character is integral to her identity. The

earliest Christians claimed to be witnesses to the life, death, and

Resurrection of Jesus, thereby making Christianity a historical religion,

emanating from a Judaism that was itself a historical religion.

Christianity staked its claim to truth on certain events, notably that at a

precise moment in history the Son of God came to  earth. The Gospels have a ring

earth. The Gospels have a ring

of historical authenticity partly because of the numerous concrete details they

contain, the care with which they record the times and places of Jesus’ life.

While there is no purely historical argument that could convince skeptics that

Jesus rose from the dead and appeared to His disciples, His Resurrection can

scarcely be excluded from any historical account. Marc Bloch, the great

medievalist who was a secular-minded Jew (he perished in a German prison camp),

observed that the real question concerning the history of Christianity is why

so many people fervently believed that Jesus rose from the dead, a belief of

such power and duration as to be hardly explicable in purely human terms. [1]

But an awareness of the historical character of the Church carries with it the

danger that she will be seen as only a product of history, without a

transcendent divine character. While Christians can never be indifferent to the

reliability of historical claims, since to discredit the historical basis of

the Gospel would be to discredit the entire faith, they must be aware of their

limits.

The modern “historical-critical method” has provided valuable help in

understanding Scripture—explicating the precise meaning of words, recovering

the social and cultural milieu in which Jesus lived, situating particular

passages in the context of the entire Bible. But it understands the Bible

primarily in terms of the times in which it was written and can affirm no

transcendent meaning.

Also, modern scholarship itself is bound by its own times, and the

historical-critical method has a history of its own that can also be

relativized. Some scholars cultivate a spirit of skepticism about almost

everything in Scripture, including its antiquity and the accuracy of its

accounts. A major fallacy of this skepticism is the assumption that, while

religious believers are fatally biased, skeptics are objective and

disinterested. Some practitioners of the historical-critical method take a far

more suspicious view of Christian origins than most historians take toward

other aspects of ancient history. (Far more is known about Jesus than about

many of the Roman emperors.)

Then there are the attempts of some historians to make Jesus a modern man—the

claim that He “liberated” women in the feminist sense or that He was the leader

of a political movement. Such claims necessarily assume that from the very

beginning the leaders of the Church systematically falsified the record,

concealing the fact that women were among the Twelve, for example.

The distinction between “the Jesus of history” and “the Christ of faith” was

formulated by certain modern theologians as part of the effort to

“demythologize” Jesus as the Son of God and Redeemer of the universe,

dismissing that belief as a theological construct only loosely connected, if at

all, to the actual, historical Jesus.

A fundamental flaw of the historical-critical method is that, while at various

times it has called virtually all traditional beliefs into question, it offers

no sure replacement, merely many competing theories.

If the babel of scholarly voices is taken at face value, it forces the

conclusion that there is no reliable knowledge of Jesus. But Christians can

scarcely think that God gave the Bible to man as a revelation of Himself but

did so in such a way as to render it endlessly problematical, or that for many

centuries its true meaning was obscured and only came to light in modern times.

Thus, while making use of scholarship, Christians must ultimately read

Scripture with the eyes of faith. Its central message—salvation through Jesus

Christ—is incomprehensible to those who treat it as a merely human document.

December 28, 2012

The New “Blesseds” of 2012

The New “Blesseds” of 2012 | J. J. Ziegler | Catholic World Report

A look at the lives of the holy men and women beatified in the last year.

In September 2005, the Congregation for the Causes of

Saints announced that Pope Benedict was instituting new

procedures for the rite of beatification.

“Canonization is the supreme glorification by the Church of

a Servant of God raised to the honors of the altar with a decree declared

definitive and preceptive for the whole Church, involving the solemn

Magisterium of the Roman Pontiff,” the Congregation stated. “Beatification, on

the other hand, consists in the concession of a public cult in the form of an

indult and limited to a Servant of God whose virtues to a heroic degree, or

martyrdom, have been duly recognized.” The liturgical cult of blessed,

according to the formula of beatification, is limited in locis ac modis iure

statutis (“in places and modes established by law”).

Beginning in 1662, beatifications took place in Rome, with

a curial official leading the ceremony in the morning and the pope venerating

the blessed in the afternoon. In 1971, the popes began to preside personally at

the beatification rites, which at times came to be celebrated outside Rome.

“Rites of beatification and canonization are already in themselves

quite different; nonetheless, the fact that from 1971 onwards the Holy Father

generally presided at them has almost blinded people to the substantial

difference between the two institutions,” the Congregation noted. Pope Benedict

blended aspects of the older and newer practices: beatifications would henceforth

typically be presided over by the prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of

Saints and would typically take place outside Rome.

In 2012, 28 venerable servants of God—including 15 martyrs,

five founders of religious communities, and two converts—have been raised to

the altars in 14 beatification ceremonies.

Continue reading on the CWR site.

Obstacles to Reading Scripture in Modernity: Von Balthasar’s Response

Obstacles to Reading Scripture in Modernity: Von Balthasar’s Response | Daniel M. Garland, Jr. | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Hans Urs von Balthasar’s theological aesthetics {are} a remedy for the breakdown in modern biblical exegesis and the groundwork of an approach to revelation that allows the glory of God to show forth in all of its splendor.

In the first book of the first part of Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Trilogy, The Glory of the Lord: Seeing the Form,

von Balthasar lays out his plan for a theological aesthetics. He

envisions his project as a reversal of the ordering of the

transcendentals in the works of Immanuel Kant. Kant began with his

critique of pure reason (truth), then moved to a critique of practical

reason (good), and finally a critique of judgment (beauty). Thus, von

Balthasar begins where Kant ends and affirms that without beauty as the

starting point, the other transcendentals are lost.

In a world without beauty—even if people cannot dispense

with the word and constantly have it on the tip of their tongues in

order to abuse it—in a world which is perhaps not wholly without beauty,

but which can no longer see it or reckon with it: in such a world the

good also loses its attractiveness, the self-evidence of why it must be

carried out. Man stands before the good and asks himself why it must be done and not rather its alternative, evil. 1

This is precisely where we have arrived in modernity. Beauty has been

tossed out of every sphere of modern society as evidenced by modern

art, music, literature, and manner of dress. All types of vulgarities

affront us when we turn on a television set, radio, or take a stroll

down a city street. A perusal of the daily news headlines reveals that

goodness is slipping away. As with the good, so also with the truth.

Relativism is an imposing beast that no longer tries to conceal itself,

but instead walks out in the open and produces more spawn than rabbits

in mating season. Eventually, Being itself is questioned. Without

beauty, nihilism is the final frontier. “The witness borne by Being

becomes untrustworthy for the person who can no longer read the language

of beauty.” 2 Thus,

for von Balthasar, beauty must be restored to its fundamental place at

the head of the transcendentals. Not only is this restoration needed for

the survival of culture, it is likewise necessary for the renewal of

modern biblical studies with its destructive approach to reading Sacred

Scripture. In this article, I will present von Balthasar’s theological

aesthetics as a remedy for the breakdown in modern biblical exegesis and

the groundwork of an approach to revelation that allows the glory of

God to show forth in all of its splendor.

The starting point of von Balthasar’s aesthetics comes from the Christmas preface of the Roman rite:

December 27, 2012

Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John

Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | An Excerpt from On

The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

The farewell discourses of Jesus, as the Gospel of John presents them

to us, hover in a singular way between time and eternity, between the

present

hour

hour of the Passion and the new presence of Jesus that is already dawning,

because the Passion itself is at the same time his "glorification" as

well. On the one hand, the darkness of the betrayal, of the denial, of

the abandonment of Jesus to the ultimate ignominy of the Cross weighs

upon these discourses; in them, on the other hand, it seems that all of

this has already been overcome and resolved into the glory that is to

come.

Thus Jesus describes his Passion as a going away that leads to a new and

fuller coming–as a state of being-on-the-way with which the disciples

are already acquainted.[1] Thereupon Thomas, surprised, asks the question,

"Lord, we do not know where you are going; how can we know the way?" Jesus

answers with a statement that has become one of the central texts of Christology:

"I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father,

but by me."

This revelation of the Lord, however, elicits a new question now-or rather,

a request, which this time is made by Philip: "Lord, show us the Father,

and we shall be satisfied." Again Jesus replies with a revelatory word,

which leads from another perspective into the very depths of his self-consciousness,

into the very depths of the Church's faith in Christ: "He who has seen

me has seen the Father" (Jn 14:2-9). The primordial human longing to see

God had taken, in the Old Testament, the form of "seeking the face of

God". The disciples of Jesus are men who are seeking God's face. That

is why they joined up with Jesus and followed after him. Now Philip lays

this longing before the Lord and receives a surprising answer, in which

the novelty of the New Testament, the new thing that is coming through

Christ, shines as though in crystallized form: Yes, you can see God. Whoever

sees Christ sees him.

This answer, which characterizes Christianity as a religion of fulfillment,

as a religion of the divine presence, nevertheless immediately evokes

a new question. "Already and not yet" has been called the fundamental

attitude of Christian living; what this means becomes evident precisely

in this passage. For the next question is now (for all of post-apostolic

Christianity, at least): How can you see Christ and see him in

such a way that you see the Father at the same time?

This abiding question is placed in the Gospel of John, not in the discourses

in the Cenacle, but rather in the Palm Sunday account. There it is related

that some Greeks, who had made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to worship, came

to Philip–that is, to the disciple who in the Cenacle would voice

the request to see the Father. These Greeks present their request to Philip,

who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, an extensively Hellenized part of the

Holy Land: "Sir, we wish to see Jesus"' (Jn 12:20-21). It is the request

of the pagan world, but it is also the request of the Christian faithful

of all times, our request: We want to see Jesus. How can that happen?

Jesus' response to this request, which was conveyed

to the Lord by Philip together with Andrew, is mysterious, like most of

the answers that Jesus gives in the fourth Gospel to the great questions

of mankind that are posed to him. It is not recorded whether there was

an actual encounter between Jesus and those Greeks. Jesus' answer, instead,

opens up a horizon that is completely unexpected at this point. For Jesus

sees in this request an indication that the moment of his glorification

has come. He suggests in greater detail in the following words how this

glorification will come about: "Unless a grain of wheat falls into the

earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit"

(Jn 12:24).

The glorification occurs in the Passion. This is what will produce "much

fruit"–which is, we might add, the Church of the Gentiles, the encounter

between Christ and the Greeks, who stand for the peoples of the world

in general. Jesus' answer transcends the moment and reaches far into the

future: Indeed, the Greeks shall see me, and not only these men who have

come now to Philip, but the entire world of the Greeks. They shall see

me, yes, but not in my earthly, historical life, "according to the flesh"

(cf. 2 Cor 5:16 [Douay Rheims]); they will see me by and through the Passion.

By and through it I am coming, and I will no longer come merely in one

single geographic locality, but I will come over all geographical boundaries

into the farthest reaches of the world, which wants to see the Father.

Jesus announces his coming from the perspective of his Resurrection, his

coming in the power of the Holy Spirit, and so he proclaims a new way

of seeing that occurs in faith. The Passion is not thereby left behind

as something in the past. It is, rather, the place from which and in which

alone he can be seen. Jesus expands the parable of the dying grain of

wheat that is fruitful only in death into the proper and fundamental pattern

for human existence: "He who loves his life loses it, and he who hates

his life in this world will keep it for eternal life. If any one serves

me, he must follow me; and where I am, there shall my servant be also"

(Jn 12:25-26). The seeing occurs in following after, Following Christ

as his disciple is a life lived at the place where Jesus stands, and this

place is the Passion. In it, and nowhere else, is his glory present.

What does this demonstrate? The concept of seeing has acquired an unexpected

dynamic. Seeing happens through a manner of living that we call following

after. Seeing occurs by entering into the Passion of Jesus. There we see,

and in him we see the Father also. From this perspective the words of

the prophet quoted at the end of the Passion narrative of John attain

their full greatness: "They shall look on him whom they have pierced"

(Jn 19:37; cf. Zech 12:10).[2]

Seeing Jesus, in whom we see the Father at the same time, is a thoroughly

existential act. From the verbal perspective we must add that the concept

of the "face of Christ" is not found in these Johannine texts. Yet they

are implicitly connected with a central theme of the Old Testament, concerning

an essential attitude of piety that is described in a series of texts

as "seeking the face of God". Despite the difference in terminology; there

is a profound continuity between the Johannine "looking on Christ" and

the Old Testament "being on the way" toward looking upon the face of God.

In Paul's Second Letter to the Corinthians the verbal connection is also

to be found, when he writes about the glory of God that appears in the

face of Christ (2 Cor 4:6). We will have to return to this later. Both

John and Paul refer us to the Old Testament. The New Testament texts about

seeing God in Christ are deeply rooted in the piety of Israel; by and

through it they extend through the entire breadth of the history of religion

or, perhaps to put it better: They draw the obscure longing of religious

history upward to Christ and thereby guide it toward his response.

If we want to understand the New Testament theology of the face of Christ,

we must look back into the Old Testament. Only in this way can it be understood

in all its depth.

Endnotes:

[1] Romano Guardini has described this interpretation of the farewell

discourses very beautifully in: The Lord: Reflections on the Person

and the Life of Jesus Christ, trans. Elinor Castendyk Briefs (Chicago:

Henry Regnery, 1954), pp. 374-80.

[2] For the interpretation of John 19:37, see also Rudolf Schnackenburg,

Das Johannesevangeluin 3 (Herder, 1975), pp. 343-45 [English trans.,

The Gospel according to St. John (New York: Crossroad, 1982)].

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• Author Page for Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI

• The Truth of the Resurrection |

Excerpts from Introduction to Christianity | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John |

Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• God Made Visible |

A Review of On The Way to Jesus Christ | Justin Nickelsen

• A Shepherd Like No Other |

Excerpt from Behold, God's Son! | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel |

Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• God Made Visible: On the Foreword to Benedict XVI's Jesus of Nazareth | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• A Jesus Worth Dying For |

On the Foreword to Benedict XVI's Jesus of Nazareth | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion

| From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

December 26, 2012

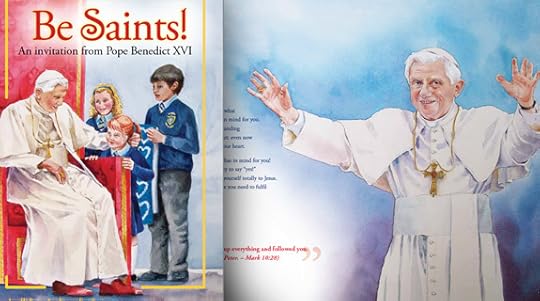

The Joy of Painting the Pope and Saints

The Joy of Painting the Pope and Saints | Catholic World Report | Interview

Painter and illustrator Ann Kissane Engelhart uses an unforgiving medium to depict the call to holiness.

Ann Kissane Engelhart (www.annkissaneengelhart.com) is a

watercolorist based in Long Island whose paintings have been featured in the

Empire State Building, St. Francis Hospital, the DeMatties Center, Brooklyn

College and Wagner College and in private collections. She has won numerous

awards, she has exhibited in galleries on Long Island and New York, and her

illustrations have been published in a variety of magazines and periodicals.

She illustrated the children's book, Friendship

With Jesus: Pope Benedict XVI talks to Children on Their First Holy Communion, which featured Benedict

XVI's answers to questions put to him by children in Rome; the book was edited by

popular author and blogger Amy Welborn. Ann and Amy recently collaborated again

recently in the creation of Be

Saints! An Invitation from Pope Benedict XVI. She recently spoke with Catholic

World Report

about her artwork and illustrating two books about the Holy Father.

CWR: Your first book with Amy Welborn was Friendship With Jesus:

Pope Benedict XVI talks to Children on Their First Holy Communion, which featured Benedict

XVI's answers to questions put to him by children in Rome. How did you and Amy

decide upon the focus of this second book? What was the creative process like for you and Amy Welborn, who edited

the book?

Engelhart: In both instances we were inspired to create picture books

after hearing the Pope speak to young people. We felt that it was important to

find a way for more children to hear these wise words of the Holy Father.

When

Pope Benedict visited England two years ago, he made a trip to St. Mary’s college

in London where he met with young students. His beautiful and encouraging

address was broadcast to every Catholic school throughout Great Britain. Of

course when the pope speaks to the people of one country, the message is

intended for the whole world. We were confident that his lesson, inviting them

to be the saints of the 21st century, would resonate with all Catholic

children.

The

English publisher, The Catholic Truth Society, was happy to make the book

available after the great success of the Pope’s visit. We are delighted that

Ignatius Press/ Magnificat decided to collaborate with CTS once again, making

the book available in the United States and Canada.

Amy and I have developed a friendship after working on the two books, so

we informally send ideas back and forth, mostly through emails. We had a

similar vision for how to communicate the Pope’s important message, so it was a

joy to work together again.

CWR: You’ve produced many pieces of art for collections and public

displays. What is different about creating artwork for a children’s book? Are

there unique compositional challenges involved in illustrating a book?

Continue reading on the CWR site.

Also see the 2011 Ignatius Insight interview with Engelhart about the book, Friendship With Jesus: Pope Benedict

XVI talks to Children on Their First Holy Communion.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers