Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 659

April 13, 2011

The Motherland

The documentary film, Blacks Without Borders: Chasing the American Dream on Foreign Soil (2008, directed and produced by Stafford U. Bailey. Co-produced by Judy Thayer-Bailey)–which tells the story of a group of African-American professionals who immigrate to South Africa right after the end of legal Apartheid–is now on Youtube in its entirety. (It's been since February last year). You can watch it in seven parts. Here's a link to part one. Anyway, when the film first came out 3 years ago, I was asked to review it. This what I wrote:

This documentary film made by the husband and wife team of Stafford U. Bailey and Judy Thayer-Bailey follows twelve African-American entrepreneurs who decided to settle in South Africa in the early 1990s. The tone is upbeat and the subjects of the documentary all have similar-sounding stories. These include Cora Vaughn, a Chicago attorney who opened a guesthouse ("bed and breakfast" in South Africa) in Houghton, a few blocks away from now-retired President Nelson Mandela's house. There is also Charles Henderson, who grew up poor in Harlem and briefly a drug addict. He later graduate of Harvard University and now runs a company that provides "services in leadership, emotional intelligence and customer service" to South Africans. Henderson's businesses include a counseling service for victims of human rights abuses under the apartheid regime. James Prevost, a promoter and real estate developer, is the youngest of the group. He first travelled to South Africa in 1995 when then-Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell visited the country with a business delegation of African Americans in tow. Prevost later returned to Johannesburg, opening a nightclub and later establishing a booking agency for both local and visiting — mainly African-American — comedians. For Prevost business has gone up by 2,000% in four years. Now he is buying up dilapidated buildings in Johannesburg's decaying and abandoned downtown: "Here in Africa, everything is possible", he tells the filmmakers. The group is rounded out by figures like Karen Vundla, who with her South African husband owns one of the major television production companies, and Eugene Robinson, a former Atlanta-based entrepreneur whose individual investments in South Africa total $30 million — in dairy farming, real estate development, and telecommunications.

The film's subjects briefly mention the high rate of divorce among the group, but it appears that the filmmakers did not want to explore reasons for this, rather choosing to engage with positive topics. Some of the documentary subjects marvel at how relatively inexpensive things are in South Africa; Hamilton, for example, paid cash for his suburban house (he explains: "I grew up in the projects. If I am going to live in Africa I am not going to live in the projects").

Cora Vaughn estimates that her $300,000 guesthouse would have cost her at least $3 million back in Chicago. Occasionally, they strike a discordant note. Darrel West, who owns a brokerage, talks about how he had to "deal" with the fact that employees' rights are protected, while Jarman Hollard, a key player in the private medical insurance business in South Africa (only 7 million South Africans have some kind of insurance) proclaims: "I'm a capitalist. I am truly here to make … business."

Not everyone only keeps an eye on the bottom line. Jose Bright is a soft-spoken, middle-aged former aide to the mayor of Washington DC who served as liaison for South African trade missions to the US capital. He eventually moved to South Africa, where he started a non-governmental organization, Teboho's Trust, working with young people in Soweto (average income R1,000 per month) to help them to prepare for college. Telling his story, the film ventures into the townships for the first time, giving some glimpses of the racial and class inequalities of the world that these new immigrants walk into. Otherwise, the film spends most of its time in Johannesburg's wealthier suburbs and its corporate offices where its subjects are at home.

Blacks without Borders gives little sense of the historical contexts of African-American immigration to South Africa in relation to the longer history of the settlement of African Americans in Africa, and that group's relation to modern South African history. In 1859, two free descendants of African slaves brought to the Americas—Robert Campbell, a chemist from Jamaica, and Martin Delaney, a medical doctor from the United States—travelled to what is now Nigeria to investigate possibilities of settling in Africa. Their trip included signing agreements with Yoruba authorities to settle African Americans there in exchange for contributing their skills as tradesmen and entrepreneurs. Both men returned to the Americas, but Campbell would later return and settle in Lagos with his family in 1862, where he established one of the colony's first black-owned newspapers. Though freed slaves established the West African country of Liberia in 1822 and settled in Sierra Leone in the mid-19th century, Campbell and Delaney were the first to popularize the idea of returning to Africa among black Americans. Later Marcus Garvey's "Back to Africa" movement garnered a strong following among urban black Americans during the first half of the twentieth century.

It was only from the late 1950s, however, with the advent of political independence for a large number of sub-Saharan African countries, that emigrating to Africa became an attractive (and feasible) option for African Americans tired of American racial segregation. In 1957, when the Gold Coast attained its independence, Kwame Nkrumah—who had a long association with American blacks and studied outside Philadelphia—invited African-Americans to come and live in the newly independent Ghana. Many of these—including Maya Angelou and Shirley Du Bois, who started Ghana's television service—would play key roles in Ghana's new government, business classes, and civil society.

However, as early romantic enthusiasm for independence tapered off (Nkrumah, for one, was removed by a military coup in 1966), many of these immigrants returned to the United States, or moved elsewhere.

By the mid-1970s only a few scattered committed individuals—former Black Panthers in Tanzania, Kwame Toure in Guinea, development workers and academics scattered over Southern African frontline states—remained. Despite persistent racism and inequality, blacks in the United States were making some headway in political and economic life. A number of blacks were elected to public office and private entities were under pressure to hire more minorities. For most Americans—in its media at least—the continent was increasingly associated with political and economic crises. Not surprisingly, by 1997, black journalist Keith Richburg, who had worked as a foreign correspondent covering civil wars in Somalia and Rwanda in the early 1990s, wrote in his memoir: "Talk to me about Africa and my black roots and my kinship with my African brothers, and I'll throw it back in your face, and then I'll rub your nose into the images of the rotting flesh."[1] He added for good measure that he was happy his ancestors escaped Africa, even if through slavery.

One country, however, sustained in the African-American imagination: South Africa. African-Americans had played some role in that country's history since the mid-nineteenth century, especially in educating some of its nationalist leadership (among others, ANC leader John Dube, who studied at Oberlin College, Charlotte Maxeke, who started the ANC Women's League and was educated at Wilberforce College, also in Ohio, and Alfred B. Xuma, educated at Tuskegee, the University of Minnesota, and Northwestern).[2] In South Africa, African-American missionaries started one of the largest black independent churches, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Later when the ANC was outlawed in South Africa, African-Americans were some of the early and most vocal supporters of the South African struggle (while mainstream US opinion largely sided with the apartheid regime until the 1980s). The mid twentieth-century South African system of apartheid mirrored the US Jim Crow system of racial violence and racial discrimination. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X both singled out apartheid for criticism.

When, in 1990, Nelson Mandela, the symbol of the South African freedom struggle, was freed after 27 years in prison, he immediately travelled to the United States. Visiting eight cities in 11 days and addressing the US Congress, as the first African and only the third private citizen to do so, Mandela helped cement Americans' popular associations with South Africa. This was what Port Elizabeth-born academic Rob Nixon described at the time as South Africa's "idiom and psychology of redemptive politics": deliverance from bondage, divine election, promised lands and the destiny of humanity. South Africa's transition definitely resonated with African-Americans and some began to look to South Africa as an emigration option.[3]

Blacks without Borders feels at times like an infomercial for an immigration firm. It shows, for example, some members of the group taking the director on "tours" of their houses in a way that reminds of the popular US television show, MTV Cribs. The filmmakers hint at the tensions between the African-American immigrants and black South Africans, but the film glosses over this. In a brief scene where African-Americans and black South Africans discussed "misunderstandings," African-Americans are said to be "arrogant."

There is also evidence of competition for business between the two groups. There is little mention, either, of the toxic xenophobia of South Africans especially towards black immigrants or of what this means for African-Americans in South Africa. In February 2008 such xenophobia resulted in widespread violence: 42 African immigrants and refugees were killed, and thousands were left homeless by black South African demonstrators. In the filmmakers' defence, Blacks without Borders was completed before the violence broke out, and some may argue that African-Americans are not subject to the same anomie reserved for continental black Africans. But that is enough reason for the film to explore that relationship.

Other flaws include the fact that, to illustrate the back history of apartheid, the filmmakers present footage of Australian Aboriginals or Polynesians to stand in for nineteenth-century black South Africans, while images of Cape Town stand in awkwardly for Johannesburg.

I watched this film for the first time soon after Barack Obama had been elected President of the United States; I wondered what that momentous and historical turn of events would mean for the film's subjects. The filmmakers would do well to update the film with this in mind.

References

Campbell, James. Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa,

1787-2005. New York: Penguin, 2007.

Gish, Steven. Alfred B. Xuma: African, American, South African. New

York: New York University Press, 2000.

Massie, Robert. Loosening the Bonds. The United States and South

Africa in the Apartheid Years. New York: Nan A Talese Books, 1998.

Nixon, Rob. Homelands, Harlem and Hollywood: South African Culture and

the World Beyond. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Richburg, Keith. Out of America: A Black Man Confronts Africa. San

Diego: Harvest/HBJ Books, 1998.

Notes

[1] Richburg (1998), p.xvi

[2] See Massie (1998) and Gish (2000).

[3] Nixon (1995), p6.

Tunde Olaniran

Tunde Olaniran is hip hop. Tunde Olaniran is the son of an American mother and a Nigerian father. Tunde Olaniran lives in Flint, Michigan. This is the video for his latest single 'Cobra.'

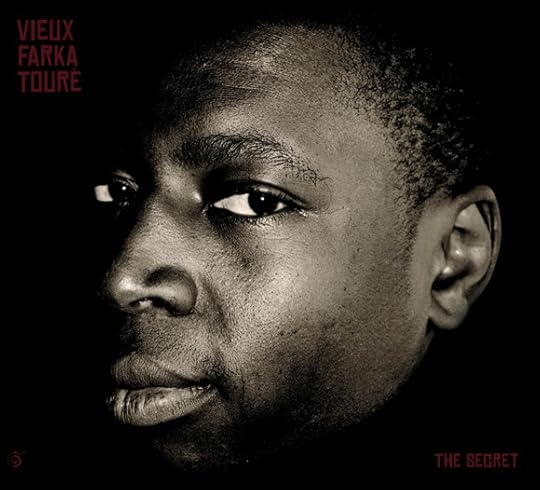

'The Secret'

No it's not the formula to rid Libya of Gaddafi and his sons, but the announcement of Vieux Farka Toure's new album next month.

'Coming to America'

Writer Teju Cole– he has a new novel, "Open City"–talks and writes about identity and immigration to The New Yorker.

The Roy Ayers Project

Roy Ayers played and recorded with Fela Kuti (here's an example) and he has reinvented himself musically a few times–he still does. Now there's a new documentary film about Ayers. In the trailer, above, Bobbito Garcia, tells about Ayers' ability to bring the sunshine. There's also this, below, by The Roots drummer and bandleader, Questlove.

The 'Top Think Tanks' in the World

Despite my skepticism about "top 10″ lists, I waded through the University of Pennsylvania's Penn's Think Tanks and Civil Society Program's annual rankings of the world's top think tanks. Mainly because it says something about the political economy and ideology of knowledge.

The "Global Go To Think Tank Rankings" was publicly released in late January. The authors of the report go on about how the rankings "… are based on a 2010 worldwide survey of 1,500 scholars, journalists, policymakers and peers from approximately 120 countries. The panel nominated and ranked nearly 7,000 think tanks from every region of the world." Basically those ranked judged themselves.

No surprises that the Brookings Institute in Washington D.C. finished top. Second and third are the Council on Foreign Relations and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, also both based in the U.S. Chatham House (aka The Royal Institute of International Affairs) and Amnesty International, both based in London, are 4th and 5th in the world.

You can see where this is going.

The results are then broken down for the top non-U.S. think tanks and the top U.S. institutions. So Chatham House and Amnesty International, Transparency International (in Germany), the International Institute for Strategic Studies (also in Britain) and the Stockholm Peace Research Institute in Sweden, are the top "non U.S." think tanks.

On the "US-only list," the top 3 institutions from the earlier mentioned "global top 5″ list are the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington D.C. and the RAND Corporation.

There's also a couple of other sub-lists readers of this blog will be interested in.

Take the "Development" think tank rankings. This is the top 5: (1) Brookings Institution (2) Center for Global Development, (United States); (3) Overseas Development Institute (United Kingdom); (4) German Development Institute or Deutsches Institut fur Entwicklungspolitik, (Germany); and (5) Chatham House.

The report also notes "… the rise of think tanks in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa." Whether these think tanks offer fresh ideas or anything different from their counterparts in the West–given that they share the same funding sources and ideas–is not discussed in the report.

So who are the top think tanks in Africa?

There are two separate "top 25″ lists in which African think tanks are ranked: North Africa and the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. (I already know a few people who won't like this demarcation.)

In the "North Africa and the Middle East" list, the follow African centers make the cut: Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, (Egypt) at no.3, the Ibn Khaldoun Center for Development Studies, (Egypt) at no. 19, theCenter d'Etudes et des Recherches en Sciences Sociales, (Morocco) at no. 22, and the Information and Decision Support Center in Egypt at no. 25.

As for Sub Saharan Africa, here's the full list:

1. South African Institute of International Affairs, (South Africa)

2. Institute for Security Studies (ISS), (South Africa)

3. Free Market Foundation, (South Africa)

4. Centre for Conflict Resolution, (South Africa)

5. African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes or ACCORD, (South Africa)

6. Centre for Development and Enterprise, (South Africa)

7. Africa Institute of South Africa, (South Africa)

8. African Economic Research Consortium, (Kenya)

9. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), (Senegal)

10. Center for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA), (Nigeria)

11. Institute of Economic Affairs, (IEA-Ghana), (Ghana)

12. Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA), (Botswana)

13. African Technology Policy Studies Network, (ATPS-Tanzania), (Tanzania)

14. IMANI Center for Policy and Education, (Ghana)

15. Centre d'Etudes, de Documentation et de Recherches Economique et sociale (CEDRES), (Burkina Faso)

16. Centre for Development Studies, (Ghana)

17. Ghana Centre for Democratic Development (CDD), (Ghana)

18. Centre for Policy Analysis, (Ghana)

19. Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), (Nigeria)

20. Research on Poverty Alleviation (REPOA), (Tanzania)

21. Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC), (Uganda)

22. Initiative for Public Policy Analysis (IPPA), (Nigeria)

23. Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR), (Uganda)

24. Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF), (Tanzania)

25. Kenya Institute

You can download the full report here.

Reality TV

The practice of renting out Cape Town's "scenery" and its cheaper film crews can have its misunderstandings. Take "Safe House," the new "action thriller" starring Denzel Washington and Ryan Reynolds, that's really set in South America. I can only imagine the cliches about South America for which South Africa stands in here. Anyway it sounds more like "Training Day":

A movie starring Denzel Washington was a little too thrilling for a Cape Town neighbourhood that has experienced gang violence.

Callers to talk radio said they feared gang fights had returned to the township when they heard the sounds of automatic gunfire overnight.

Denis Lillie, head of the Cape Film Commission, said today the producers had been authorised to film a sequence involving car chases and the firing of blanks, and had informed residents in the immediate neighbourhood. But he says the sound carried further than expected.

Lillie says the Cape Town community is getting "used to the fact that people want to film here". The movie, Safe House, is described as a crime thriller.–SAPA.

April 12, 2011

'Why is it so hard to make it in America'

Charles Bradley, backed by The Menahan Street Band, performs "Why Is It So Hard" live from Mellow Johnny's Bike Shop in Austin, TX, during KEXP's broadcast at SXSW

Orientalism in Sub-Saharan Africa

James North:

Orientalism takes a different form in sub-Saharan Africa. There, Orientalists do not emphasize the "Islamic" angle quite as much, although they do sometimes suggest that a "fault line" running across the Sahel, with an expansive "Islam" to the north and "Christianity" to the south, is a reliable guide to conflict in many countries.

But in Africa, the Orientalists are more likely to emphasize that "ancient tribal enmities" explain contemporary conflict, without necessarily adding the religious dimension.

I recently returned from the West African nation of Cote d'Ivoire, in which fighting with a strong ethnic base is still simmering. Several thousand people are already dead, and up to 1 million are refugees. I produced this fairly lengthy report for The Nation.

The mainstream Western press cites ethnic differences to explain the violence there. I found that citing ethnicity is not "wrong," but woefully incomplete.

In short, Cote d'Ivoire['s economy] is dominated by millions of small cocoa planters, who grow the raw material from which our chocolate is made. Big Western multinational corporations, like the U.S. agribusinesses Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland, shamelessly underpay the small Ivorian farmers for their cocoa beans. I met with these hard-working, likeable people, and I listened to their bitter complaints.

Without a reasonable income from cocoa exports, the Ivorian economy stagnates, promoting frustration, particularly among young men. Unscrupulous local politicians use ethnicity to mobilize support. Violence grows, and then explodes.

One key fact here is that these ethnic differences are not "ancient tribal hatreds." Until the world cocoa market weakened a couple of decades ago, the various ethnicities in Cote d'Ivoire got along well. The economic crisis raised the tensions.

The average well-meaning American sees a brief, confusing report on his television news, in which wild-looking young African men are riding around brandishing weapons in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire's commercial capital. Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland are never mentioned.

Freedom's in the Toilet

Ahead of local government elections in South Africa–scheduled for May–the Democratic Alliance, which governs Cape Town and the Western Cape, spins about its "service delivery successes." Of course they're taking of downtown Cape Town and its surrounding, historically white, suburbs, but tell that to the country's mainstream media. The truth is the DA's electoral successes are more a mix of the ANC's excesses and blunders, racial pandering and good PR.

For most of Cape Town's inhabitants, life is still one of substandard, overcrowded housing, forced evictions, non-existent primary health care, bad schools and, crucially, no access to proper sanitation facilities. We've detailed the city's policies on AIAC, here and here.

Anyway, to show up the DA's empty spin, the Social Justice Coalition–an organization we like here at AIAC–are planning "toilet queues" this month–to coincide with the 17th anniversary of South Africa's first democratic elections. Research shows that 10,5 million people don't have access to a toilet countrywide. Half of a million of these in Cape Town. The Social Justice Coalition's "build-up event" will take place in Khayelitsha this coming Saturday 16 April. The "main event" is scheduled on Freedom Day, 27 April. They plan to hold an inter-faith service at the historical St. George's Cathedral. Protesters will then march on the city council's offices "where a symbolic queue for toilets will be held." If you're in Cape Town, get in the queue.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers