Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 648

May 12, 2011

The Lion King Moment

Great scene from ABC's "Modern Family," a comedy series about a very traditional family.

The scene is featured on Sphere of Influence, a blog about stereotypes, by one of my students, Loren Lynch. Check out the blog.

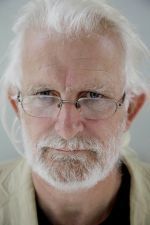

What's So Funny

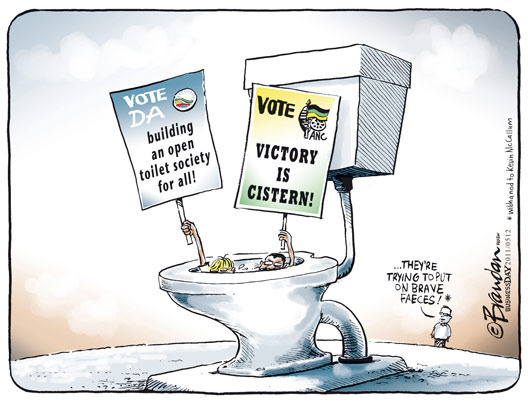

Cartoonist Andy Mason recently published a history of the art form in South Africa. What's So Funny? Under the skin of South African Cartooning is the only book of its kind that traces the origins and development of cartooning in South Africa, and its political place in the socio-political context. Brett Davidson recently interviewed Mason and put 5 questions to him.

Where did the idea for a history of cartooning come from?

Well it actually rose out of my masters' research that I did at the University of Kwazulu-Natal about 10 years ago. As cartoonist myself, I was interested in looking at the impact that cartooning had had on the South African struggle — whether in fact we could say that cartooning and comics had had any impact at all on the transition to democracy. I came to the conclusion that it had, albeit a modest one. And then from there I became more and more interested in particular in looking at the icons and stereotypes that cartoonists used in the South African context to describe the different actors in the political scenario.

I tried to define when South African cartooning started, I started to do research through the 50s and the liberal cartooning of the mid-century period, and then I went back to look at the antecedents to that, and eventually I went all the way back to a cartoon which was published in 1819 by George Cruikshank who was a leading London caricaturist of the day. I called it the Cruikshank's cannibal cartoon. It shows the white settlers being devoured by these cannibal figures – these huge, hulking monstrous figures. And it kind of – for me that became an iconic cartoon, a prototypical South African cartoon.

The same time as I was doing that historical research the whole pace of political change in SA developed in the post-apartheid period – and moved from what I call the euphoric national consensus of the transition to a period which I call the discourse of disillusionment. And the cartoonist that I particularly focused on with regard to that was Zapiro. While I was writing the book, I became good friends with him. And I started to become involved in the actual unfolding story of this epic confrontation between the cartoonist and the political figure in South Africa–between Zapiro and Jacob Zuma.

And so that particular conflict or confrontation/contest seemed to me to be a contest between two enormously powerful forces which in South Africa had assumed a unique form. And that was kind of symbolized by this conflict between the politician and the artist or the cartoonist. Which is essentially an embodiment of the eternal conflict between the pen and the sword.

One of the illustrations you have is a particular drawing of Zapiro's which you say displays a British style of cartooning. Is there a South African style that's identifiable and different from any other style?

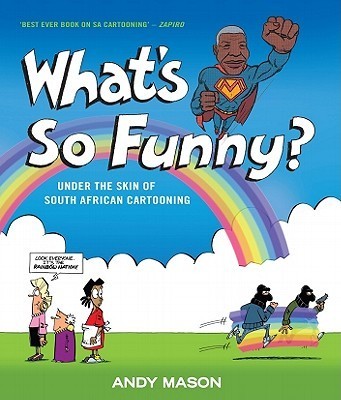

There is an evolving South African cartooning style. In my book when I talk about cartooning I talk about three main types of categories of cartooning. One is political cartooning, the other is the kind of educational campaign cartooning which was very influential in the pre-1994 period. And the third is underground cartooning, of which we have a very strong tradition in SA. There are different styles in the different sectors. Since the 90s the underground style of South African cartooning was hugely influenced by the Bitterkomix movement and in the political cartooning sector the cartooning style was hugely influenced by Zapiro. In fact all the cartoonists that came after Zapiro imitated him in one way or another.

I think that there is a style of SA cartooning. It's not so much a particular visual style. Some are very influenced by the American traditions, others more by the British and European traditions. If there is a South African style of cartooning its more to do with other less visual aspects, such as a courageous engagement with the political environment. Our cartooning has become internationally known for its enormous courage and its ability to take political leaders to task in a way that would be considered very extreme in some countries, for example the USA.

What the underground cartoonists brought to political cartooning – though it didn't start as a political movement – was a very liberated way of looking at the world, a strong left wing critical theory, and also a very scatological rude, aggressive kind of approach. They use a lot of sexual imagery and it was very robust.

If you look at the work of some of the up-and-coming new cartoonists, particularly the black cartoonists, you'll see that robustness of the way in which they depict the political scenario and in which they depict political leaders is very groundbreaking and unique to SA. And it really does define SA cartooning.

Can you say a bit more about the Bitterkomix movement?

These were Afrikaans fine artists from Stellenbosch University. They were extremely radical. They were influenced by the underground press. They were very pornographic. They were also operating from within the Afrikaans establishment. They produced their comics in Afrikaans and critiqued their own society and looked at the psychosexual aspects of it. They drew parallels between perverse forms of sexual repression within the home and family, and the political scenario. They started to mount a very damning critique of patriarchy and the patriarchal system which lay behind Apartheid, which was basically Afrikaner nationalism.

They had a free ride for a while because there was very little censorship in those years. It was a kind of anything goes environment in which not only cartoonists but visual artists, musicians, stand up comedians — lots of people exploited that political environment.

Then when the euphoric period started to dissipate after Mandela left power and the failures of the Mbeki administration started to become apparent, cartoonists started to critique the new political establishment, which was predominantly black. But unfortunately what had happened was that the racial demographic change within the South African cartooning community hadn't kept pace with the democratic changes in the rest of the country. So most of the cartoonists were still white, and the targets of their cartooning were black and so you started to get allegations of racism and those particularly revolved around the depiction of black people, particularly black politicians.

I saw there was a very challenging problematic there because cartoonists by the very nature of what they do, they work with stereotypes. They exaggerate everything. The way people look, facial stereotypes. They laid themselves open to a kind of a critique around racial issues. Interestingly that critique, even though it has been voiced by some very prominent public commentators, hasn't really got a lot of traction. And the reason is that in South Africa there is a very robust discourse that goes on. There's an enormous amount of name-calling, an enormous amount of political insult. Political insult is actually the modus operandi of the South African political establishment. For example, Helen Zille and Julius Malema are very unrestrained in their use of all kinds of epithets to describe each other, and they're always insulting each other. So the political behaviour of people in positions of authority provides fantastic material for South African cartoonists.

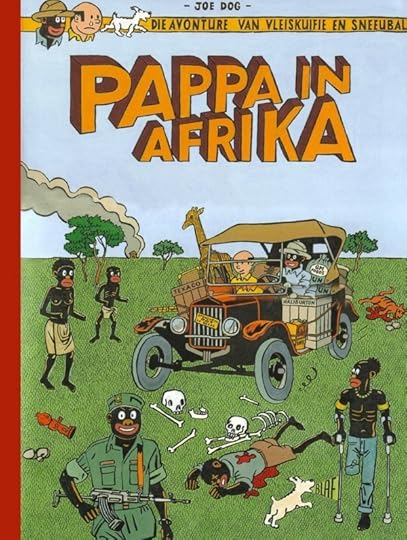

Are you seeing more black cartoonists emerging now? Looking at your book, the faces and names are predominantly white, until quite recently

The first black cartoonists emerged in the alternative publications of the late apartheid period. Until the late 1970s you didn't have any black cartoonists to speak of in the South African press. Then as new opportunities arose in the newspapers you started to get new cartoonists emerging. There are a couple of important ones. There's Brandan Reynolds who's at Business Day. He grew up in the Cape Flats. He's a very sophisticated cartoonist who is influenced by the American scene. He has been very critical of Mbeki, very critical of Zuma. He shows politicians as pigs rooting in the trough for example, and all that sort of stuff.

You have Sifiso Yalo who is at the Sowetan, probably the most prominent black cartoonist in that milieu. You have Wilson Mgobhozi who took over from Zapiro at The Star and is syndicated throughout the Independent newspaper group. You have a couple of other lesser figures – Bethuel Mangena at Sunday World and a couple of others like that. Numerically they are not very many and the demographic is still completely skewed, but because of syndication these guys get a lot of exposure. Just in terms of publication I think we have a strong presence of significant black cartoonists in South Africa, but it's nowhere near where we want to go. It's probably a generational thing. Cartoonists are very tenacious in holding on to their positions. A cartoonist like Fred Mouton who started working for Die Burger during the height of apartheid — I think he started in 1974 — he's still at Die Burger today.

What do you make of claims that South Africans are not ready for satire (made mainly by broadcasters reluctant to air satirical shows such as ZA News). The history of cartoons would suggest that that's nonsense.

I don't believe that for a moment. If you just look at the field of stand-up comedy — a field of satire where the number of South African black comics has increased exponentially in the past ten years – there are so many brilliant black stand up comedians now. Perhaps because it's a theatrical discipline it has outstripped cartooning, which is in a sense a lonely, arduous field of activity. But it's only a matter of time. I also think that the media themselves are to blame for not being more proactive in providing the opportunities that should be provided. But the South African satirical tradition is extremely strong. It started off with challenging the British, with Daniel Boonzaier slagging off Smuts and Botha in the early years of the last century. It went through the liberal cartoonists slagging off the Nationalist government. It intensified during the 80s in the oppositional papers of the alternative press and it blossomed in the 90s with the new South African democracy. And it's on a roll, it's not going to be stopped. The efforts being made by the establishment to contain that space – which I call the Jester's space — are not that successful and a tradition has been established which is going to be very difficult to combat. I think satire in South Africa is definitely here to stay.

Oh Canada

A long, long time ago when there was still Apartheid, I needed a passport to travel by bus from Cape Town to Durban in South Africa. That meant going through the "independent homeland" of Transkei in South Africa's Eastern Cape. If you forgot that's where the state banished surplus black people and from where capital got its cheap labor. I can still remember the farce of crossing the "border" and having our documents checked by Transkei police in brown uniforms and ten gallon hats.

Then last week, before a short trip to Toronto, Canada, I received this message for South African citizens visiting Canada from Delta Airlines:

Additional Information: – Passports, identity or travel documents of Bophuthatswana, Ciskei, Transkei and Venda are not accepted.

Who even traveled or still travels with such passports? Is it because I was traveling to a country that offers refugee status to white South Africans from democratic rule in South Africa.

Toronto–where I was for the Canadian Association of African Studies annual meeting–actually turned out to be worth it. I was on a panel with fellow AIAC contributor, Neelika, and Tsitsi Jaji, in English at Penn. Other highlights: I went to a screening of academic and filmmaker Daniel Yon's beautiful new film on Sathima Bea Benjamin (review forthcoming); went to visit some exhibits of the Contact Photo Festival downtown (reviews and a possible interview on its way); drove around the Toronto suburbs and went for some cheap, very good Tamil food; met scholar and activist John S. Saul (video of John talking about his new book forthcoming on AIAC), and watched Canada's version of FOX News.–Sean Jacobs

May 11, 2011

Music Break

1970 Britain, Jamaican duo Bob and Marcia's cover of "Young, Gifted and Black" climbs to no. 5 on the UK charts. They're featured in a recent BBC documentary on the influence of reggae on 1970s British music culture.

So is Steel Pulse's "Prodigal Son" from 1978:

Matumbi's "Rock":

And Aswad's "It's Not Our Wish"

Watch the film on Youtube or below:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdfvUo...

H/T: Tony Karon

The Belgian Color Bar

Roland Gust was born to a Congolese mother and a Belgian father. He grew up in Congo, believing he was white. That is, until his family decided to return to Belgium when he was twelve. Twenty years later, in a recently released documentary, Colour Bar, we follow him in his desire to find a grammar to describe his past. 5 Questions for Roland Gust.– Tom Devriendt

Why have you waited so long to make this documentary? Why now?

It took me a long time to find the courage to talk about my being 'métis'. To formulate my feelings felt like raising problems. As long as I kept it to myself, there was no problem. Not for the outer world, that is. I remained Roland, the perfectly integrated coloured. I didn't want to come across as a frustrated black man who was ungrateful for what Belgium offered him. I didn't want to be expelled after so many years of trying, because I was begging for a recognition of my Belgian identity. I had to serve Belgium and remain silent.

After all those years of absolute and blind dedication to the country of Belgium I have now crowned myself a Belgian. I have earned my place in Belgium and no longer need the Belgian's approval to be a Belgian. As a Belgian I make use of my freedom of speech to tell my Belgian story. I no longer lie awake about the potential repercussions following my critical discourse about Belgium and the Belgian identity. A Belgian criticizes his country out of love and concern about his country. If my experiences and reflections can add to the building of a better and richer country, I have fulfilled my duty as a Belgian.

In 2010 we celebrated Congo's 50 years of independence. It was an opportunity to tell the Belgian-Congolese story in all its facets. It also allowed for the métis story to be told, although I fear the métis already is slipping back into forgetfulness.

How do you look back to the year 2010 and the way in which Belgian media reported on Congo's 50 years of independence?

Personally I don't think we can be dissatisfied about the media attention for Congo. I do find it hard to judge the general reporting here though, since I'm only exposed to a handful of media. My little interest for these media has to do with the fact that most reporting is done by Belgians. They look at Congo first and foremost as Belgians. They thus also look with different interests and desires compared to the Congo-rooted people. One should rather get inspired by stories the Congolese want to relate. This way they are given a stage where to offer their own history and projections of Congo. Maybe Belgium could have offered its own story to Congo. A series about Belgium for the Congolese television and radio maybe?

Living in Belgium, how do you look at what's happening in Congo these days?

As a member of the Congolese community I care for what's happening in Congo. I grew up there and lived the happiest days of my life. From the paradise I knew little remains apart from a tiny oasis reserved for a small group of privileged people. But I know too little about what's going on at political, social and economic levels to say much more about this. Congo is pretty much stateless and divided by different actors with their own interests and (hidden) agendas. Congo's not in the hands of the Congolese.

How do you relate to the African diaspora in Belgium and, more broadly, Europe?

I used to mainly consider myself Belgian since my self-image and identity was Belgian/white. Nowadays I also feel more Congolese than ever — without necessarily having the feeling to share the same interests and needs of other Africans in Europe. We all face the same battle against intolerance and racism. We all wish to share and experience our African culture. We share a longing for our countries. But compared to other Africans in Europe I do feel at home in Belgium. I'm also Roland, the Flemish guy from a small town in Belgium.

In which works (books, music, artists) by 'Métis' people do you find inspiration?

Before working on this film I never really searched for the voice of a métis. Although Spike Lee is one of my greatest examples, I never wondered whether he is métis. Ever since my youth I recognize myself in Afro-American artists because they shared a similar situation. We are non-white or half-white westerners in a white western world trying to produce an audio-visual language that can articulate our being métis in the best possible ways.

The Belgian Colour Bar

Roland Gust was born to a Congolese mother and a Belgian father. He grew up in Congo, believing he was white. That is, until his family decided to return to Belgium when he was twelve. Twenty years later, in a recently released documentary, Colour Bar, we follow him in his desire to find a grammar to describe his past. 5 Questions for Roland Gust.– Tom Devriendt

Why have you waited so long to make this documentary? Why now?

It took me a long time to find the courage to talk about my being 'métis'. To formulate my feelings felt like raising problems. As long as I kept it to myself, there was no problem. Not for the outer world, that is. I remained Roland, the perfectly integrated coloured. I didn't want to come across as a frustrated black man who was ungrateful for what Belgium offered him. I didn't want to be expelled after so many years of trying, because I was begging for a recognition of my Belgian identity. I had to serve Belgium and remain silent.

After all those years of absolute and blind dedication to the country of Belgium I have now crowned myself a Belgian. I have earned my place in Belgium and no longer need the Belgian's approval to be a Belgian. As a Belgian I make use of my freedom of speech to tell my Belgian story. I no longer lie awake about the potential repercussions following my critical discourse about Belgium and the Belgian identity. A Belgian criticizes his country out of love and concern about his country. If my experiences and reflections can add to the building of a better and richer country, I have fulfilled my duty as a Belgian.

In 2010 we celebrated Congo's 50 years of independence. It was an opportunity to tell the Belgian-Congolese story in all its facets. It also allowed for the métis story to be told, although I fear the métis already is slipping back into forgetfulness.

How do you look back to the year 2010 and the way in which Belgian media reported on Congo's 50 years of independence?

Personally I don't think we can be dissatisfied about the media attention for Congo. I do find it hard to judge the general reporting here though, since I'm only exposed to a handful of media. My little interest for these media has to do with the fact that most reporting is done by Belgians. They look at Congo first and foremost as Belgians. They thus also look with different interests and desires compared to the Congo-rooted people. One should rather get inspired by stories the Congolese want to relate. This way they are given a stage where to offer their own history and projections of Congo. Maybe Belgium could have offered its own story to Congo. A series about Belgium for the Congolese television and radio maybe?

Living in Belgium, how do you look at what's happening in Congo these days?

As a member of the Congolese community I care for what's happening in Congo. I grew up there and lived the happiest days of my life. From the paradise I knew little remains apart from a tiny oasis reserved for a small group of privileged people. But I know too little about what's going on at political, social and economic levels to say much more about this. Congo is pretty much stateless and divided by different actors with their own interests and (hidden) agendas. Congo's not in the hands of the Congolese.

How do you relate to the African diaspora in Belgium and, more broadly, Europe?

I used to mainly consider myself Belgian since my self-image and identity was Belgian/white. Nowadays I also feel more Congolese than ever — without necessarily having the feeling to share the same interests and needs of other Africans in Europe. We all face the same battle against intolerance and racism. We all wish to share and experience our African culture. We share a longing for our countries. But compared to other Africans in Europe I do feel at home in Belgium. I'm also Roland, the Flemish guy from a small town in Belgium.

In which works (books, music, artists) by 'Métis' people do you find inspiration?

Before working on this film I never really searched for the voice of a métis. Although Spike Lee is one of my greatest examples, I never wondered whether he is métis. Ever since my youth I recognize myself in Afro-American artists because they shared a similar situation. We are non-white or half-white westerners in a white western world trying to produce an audio-visual language that can articulate our being métis in the best possible ways.

Finland's Africa

The (Finnish) ARS 11 exhibition investigates Africa in contemporary art. In addition to artists living in Africa, the show also features others who live outside the continent, artists of African descent as well as Western artists who address African issues in their work. The exhibition features some 300 works by a total of 30 artists. The Kiasma Theatre also has a programme of ARS events and performances. The themes of the exhibition, such as migration, environmental problems and urban life are global, issues that affect us all. At best ARS 11 can produce new understanding and also provide background information on the situation in today's Africa. The exhibition will extend the idea of what Africa, contemporary art and African contemporary art are today.

I don't want to sound too obsessed about this, but the chosen 'young' African artists again really are the same ones you'll have encountered at any recent major Africa-themed exhibition around the world (I'm thinking for example of those in the U.K., Brazil and Germany). Surely there is more than this pool of, say, ten young artists? Some curators are getting lazy.

On the other hand, of the following artists also present we haven't seen much yet: Baaba Jakeh Chande (in the picture above) whose "performances in particular are influenced by change, the contrasts and similarities he encounters in the two lifestyles he has, Zambian and Finnish", and Senegalese born Samba Fall (painting below), so we might take that northbound train after all.

The exhibition runs until November 27.

– Tom Devriendt

May 10, 2011

Music Break

I can't think of any other South African artist right now who's got a bigger following outside of South Africa than DJ and producer Black Coffee. Kwaito might sell in South Africa and its neighboring countries, Black Coffee really delivers his house music also beyond the continent's borders. Reasons for his success are obvious. These two new videos pretty much sum it up: smart collaborations, clean production, catchy hooks, breezy vibes.

–Tom Devriendt

Memoirs about Africa

Timothy Burke, Swarthmore history professor–he's written a book on commodity culture in Zimbabwe–and blogger, has a great post about 'memoirs from Africa.' Basically he was asked to prepare a year-long reading of books about Africa for school alumni. Burke decided to only include memoirs or first-person perspective accounts from the last 30 years or so. He acknowledges that he's end up with "… a surplus of certain kinds of books that I find tedious because they follow such a strong template and are so driven by market fads: memoirs of white women who grew up on African farms that followed on Alexandra Fuller's great memoir of life in Rhodesia and now memoirs of child soldiers and survivors of Darfur." Anyway, his list is interesting for what it says about who publishes memoirs in Africa and what's available outside the continent. Some of the titles that made it onto his initial list are familiar, but there are also some surprises. Here are samples with Burke's mostly spot-on comments:

Alexandra Fuller's Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: "It's so distinctive in stylistic terms, and so unsentimental and unapologetic, that it still unsettles a kind of complacently do-gooder liberal expectation about what reading about Africa or white settlers ought to be like."

Samson Kambalu's The Jive Talker: An Artist's Genesis: "Great fun, fascinating, and a real cure-all for the endless parade of memoirs by Africans about their experiences of war, genocide and violence."

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: "There are other travel accounts by African-Americans that I like, but some are out of print (Eddy Harris' Native Stranger) and some I don't like (like Keith Richburg's Out of America) but Hartman's is really distinctive and fiercely resists compression or reductionism."

Aidan Hartley's The Zanzibar Chest: "I actually like this less for the early more standard colonial-nostalgia stuff on white settlers and more for Hartley's honest accounts of his work as a journalist and rootless traveller and the kind of scruffy hedonism that he got caught up in in between covering war and genocide."

William Kamkwamba's The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: " God, this is so well-meaning and sincere that I feel a bit like I've just watched a marathon of The Waltons when I read it. But again, the last thing I want is a year full of genocide and war."

Anyway, you can read the rest of the list and the back and forth between Burke and his blog readers here.

'Africa's burgeoning middle class'

At least 313 million Africans–that's one in three Africans–can be defined as middle class, according to the African Development Bank. If you earn between $2 and $20 a day , working in "salaried jobs or own small businesses," you're middle class. But only 123 million of these–those who are spending between $4 and $20 a day–can be considered economically stable, according to the ADB. And, "Tunisia, Gabon and Botswana have the largest middle classes, while Liberia, Mozambique and Rwanda have the smallest." The BBC combined all this information with a slideshow of the photographer Philippe Sibelly's project on middle class Africans, The Other Africa. The photo above is is "Antoine, a tennis instructor in Gabon's capital, Libreville. Below is a picture of Manal, "a successful singer and TV presenter in Algeria's capital, Algiers."

You can see the BBC's edit of the project here, or view it on the project's website.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers