Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 642

June 2, 2011

'Three soldiers from Somalia'

I reread that infamous 2010 New Yorker profile. of Gil Scott Heron earlier today. I was struck by the conclusion where Scott Heron tells reporter Alec Wilkinson about a novel he wants to write:

I have a novel that I can write … It's about three soldiers from Somalia. Some babies have been disappearing up on 144th Street, and I speculate later on what happened to them and how they might have been got back. These guys are dead, all three, and they have a chance in the afterlife to do something they should have done when they were alive … I have everything except a suitable conclusion.

It's also worth reading Greg Tate's obituary of Gil Scott Heron here.

Goksin Sipahioglu

One of the highlights of a recent trip to Istanbul–dominated by run-ins with operatives of a secretive Turkish political group–was a quick stop at the Istanbul Modern. What I remember most were a set of photographs taken in the 1960s in East and West Africa by the legendary photographer, Goksin Sipahioglu. This link takes you to 2008 interview with Sipahioglu, who founded the SIPA Press Agency, in Paris where he lives.

June 1, 2011

'More Time'

Masks at the Met

There's been a resurgence interest in the inscrutable African mask in several museums lately, including this horrible one at the Barbie Museum. Its as if the more evidence there is that the African of the European imagination does not exist in static primitivity, the stronger the attempt to put it back into that caged zoo.

Thankfully, there's something different at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in a small section of a first floor gallery: "Reconfiguring an African Icon: Odes to the Mask by Modern and Contemporary Artists from Three Continents" (March 8, 2011–August 21, 2011).

Ever since Man Ray's image of the porcelain-white visage his mistress, Kiki, juxtaposed with that of a gleaming Baule portrait mask from Côte d'Ivoire was published in French Vogue ("Noir et Blanche," May 1926), the West appropriated the African mask as the visual object that embodies static "primitivity." Roll in Picasso, André Derain, and Henri Matisse, whose collective homage to the inscrutable Other helped manufacture visual distance from the primitive, while inviting comparison and desire.

The Met's small exhibit includes the Beninese sculptors Romuald Hazoumé and Calixte Dakpogan (that's Hazoumé "Ibedji (Nos.1 and 2) Twins," completed in 1992, above) and American sculptors Lynda Benglis and Willie Cole. Using natural, traditionally used materials, the effluvia of consumption, and fine, coloured glass, these four artists experiment with re-personifying the performative and living qualities that masks embody in their original, animated contexts, re-configuring those traditional 'Western' associations of masks with the savage/native/other.

While Hazoumé and Dakpogan are artists who are intimately involved in the business of traditional masquerade and mask-making (Dakpogan is a descendant of a family of royal blacksmiths), their work gestures towards Benin's long history of trade—exchanges that defined its cultural, religious, political and aesthetic history. Hazoumé use of a series of discarded petrol jerrycans, and Dakpogan's repertory of discarded consumer goods, including cassette tapes, floppy disks, CDs, combs, sandals, and soda cans are a humorous nod to Marcel Duchamp's readymades, inviting the viewer into a conversation about the multifaceted, multilinear relationship with the West, modernity and the disposable nature of consumption.

May 31, 2011

The Restaurant Manager

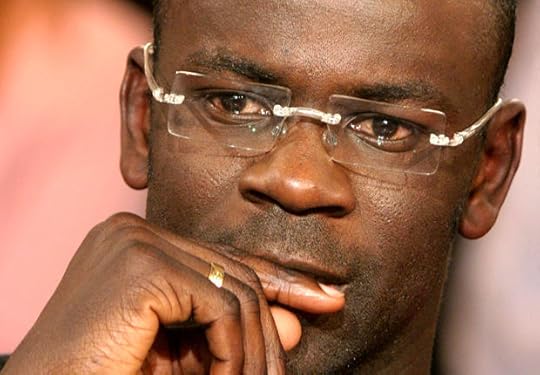

If you missed this: Lilian Thuram, the former footballer who won a World Cup medal with France in 1998 and sometimes philosopher, was in Brussels last week to promote his anti-racism campaign. While having lunch at a restaurant, the staff there told him that the toilets were "reserved for clients." The manager David Martin is quoted as saying it is all a "misunderstanding," and "… we didn't know he was a client and I admit I didn't recognise him. There was no wilful discrimination."

Martin has offered his apologies: "I also told him I would love to cook for him. But (Thuram) didn't want to stay. I really regret I am being accused of racism. I grew up among Algerians in this neigborhood and I have two blacks and a Morrocan guy working in my kitchen."

The Manager

If you missed this: Lilian Thuram, the former footballer who won a World Cup medal with France in 1998 and sometimes philosopher, was in Brussels last week to promote his anti-racism campaign. While having lunch at a restaurant, the staff there told him that the toilets were "reserved for clients." The manager David Martin is quoted as saying it is all a "misunderstanding," and "… we didn't know he was a client and I admit I didn't recognise him. There was no wilful discrimination."

Martin has offered his apologies: "I also told him I would love to cook for him. But (Thuram) didn't want to stay. I really regret I am being accused of racism. I grew up among Algerians in this neigborhood and I have two blacks and a Morrocan guy working in my kitchen."

Ephemera

"… South Africa's first Afrikaans musical." This description of the film on Youtube comes across as ridiculous and perhaps dishonest, given that (white) Afrikaans cinema is replete with musicals. For one, I could mention the films of Al Debbo or all those films you had no choice watching on Sunday nights on state TV.

5 Questions for Pole Pole Press

Earlier this year, I interviewed Fouad Asafour of the Johannesburg-based Pole Pole Press, about the press' first publication, Emzana Shack Recollections, by Lungile Sojini, and what he learned as he dipped into the world of publishing and distributing books. At "close to 100 pages in 12 pt Times New Roman on A4, single spacing," it was "not exactly a short story," but something about its "peculiar style" got a hold of Asafour. He wanted readers to encounter the writing as is, rather than have it shaped by teams of editors. What followed was an entertaining email conversation about his "experiment" to "show that it's possible to make publishing more broadly available"; the "dictatorship" of paper production companies that "molest" people "with the whiteness of [their] oh so clean bonded paper, ignoring requests for recycled or unbleached paper"; and why the low readership in South Africa is more attributable to the fact that the "current book market clearly does not produce for the large audience…but for a small, mainly white middle class" in the country.

Tell us about your new press, Pole Pole, and how you came around to creating this opportunity.

Pole Pole Press started off as an experiment out of a situation which suggested the necessity to create other and new avenues for the publication of young writers' texts. And some sort of feeling of desperation after trying to organise NIPPA, a network for independent publishers which aimed at facilitating the distribution of what I find the most amazing publications from countries as far flung as Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa – like Farafina in Lagos, Kwani in Nairobi, Chimurenga in Cape Town – all of which however are located on one and the same continent, that is, Africa. But then, I realised what I imagined was nothing but one more of those triangulations which other white people like me use to project on what we/they think is an unnavigable territory – yes, again it's Africa – scheming to create one more of the many snug and seamless (for us) solutions while ignoring the realities in the places here and there. And yes… I am learning to realise that I'm coming from this seamlessly woven public comfort zone Europe and that this missionary attempt is not really forgivable as I should know better by now. In the end, it's advised to learn from Fela Kuti, who no know go know.

But I am digressing.

Last year I received through Allan "Botsotso" Horwitz a manuscript of a novel written by Lungile Sojini, entitled Emzana Shack Recollections which the author had sent to several publishers before without ever receiving a response. And then, half a year later, Lungile calls me again and…the novel has not been read by any professional of the publishing houses he had sent it to.

Now, imagine receiving an email with a story which goes on and on and never seems to end! Amounting to close to 100 pages in 12 pt Times New Roman on A4, single spacing – not exactly a short story. But, I went on every other day to read another bit. You know, I somehow started to get caught in this text and felt that the story was really exciting and that this was due to its very peculiar style, this uncontrolled inner monologue by the narrator which results in an incredible imaginative piece of writing which I then thought deserved to be taken up and read. And that the writer ought to get some responses and reactions from other readers about his text. The story stroke a chord in me and I wanted to tell friends and others about it, like when you're saying "Hey, there is something you should know…"

At the same time I know that for a novel – especially for the first novel of young writers – to be published involves lots of work, and that the conversation between editors and authors, same with curators or gallerists or lecturers and artists, need to spend some time and effort in this process shapes a work. But then I thought maybe one could turn the process around and publish the book in this stage already before it went through a process of feedback and modification. This way, the reader directly would accompany the writer on what could become a long and ever changing road elaborating a novel. I mean, look at it this way: in publishing houses editors use to compose "Reader's Reports" when presenting a manuscript for publication, so I thought to take this literally and put the text out in the open for readers and wait for their reports.

That is just the idea behind it, and it's an experiment and we'll need see what is going to happen.

What is your vision as a publishing house, and who are your targeted writers? Your audience?

Maybe it's a bit too much to call it a publishing house, as said before, it's more like an experiment. The vision is to show that it's possible to make publishing more broadly available – apart from what has become known as the "self publishing" hype or the steadily growing web 2.0. It's more about going back and show that a printed book is something people can enjoy without spending much money. While we're ready to pay 50 or 70 Rands to watch a movie or eat out at KFC, it's actually possible to produce books cheaper in a low print run and sell at the same cost.

I am not going to elaborate here about my odyssee trying to find cheap, newsprint paper for small print runs, using photocopy machines (Yes, you monopolists of the paper production industry, molesting us with the whiteness of your oh so clean bonded paper, ignoring requests for recycled or unbleached paper: Now I know that we CAN use 60 gsm Envirotext paper which in its unobtrusive grey is perfect for book production (see Sapphire Press) – and yes, I KNOW, it is not available in sheets but only in reels as big as skyscrapers so we cannot stuff it in our little photocopy machines, but we know the people to sheet the reel and thus find a way to break this dictatorship of bleached white immaculate office paper which pierces our eyes with its sharp whiteness!).

And for sure it's about finding readers who are not satisfied with what publishing houses produce, who are looking for other things to read. As for the audience, it's also about finding access to readers who don't go to bookshops but rather to the internet cafe. Distribution right now is done informally, but I'm thinking of sharing publications as e-books – everyone interested could download a book and print a few copies in a copy shop around the corner – it's possible to find photocopiers in most towns in South Africa today, I think. This way, the headache with distribution will be cancelled, too. I think that the audience will show if this idea works.

Tell us about your first publication/author of Emzana Shack Recollections.

I met Lungile Sojini first time when he came to read in Joburg at Keleketla! Library. I will not say more about the book, read it yourself and write a review, will you? I liked the readings Lungile did in Joburg, he engaged with the audience and made them listen for around 45 minutes, that was quite amazing, I think. He joked and said that as they came and sat there in the audience he would take the opportunity to read as much as he can as he does not have the chance that often. I think that's the spirit of Pole Pole Press, don't ask for permission, if you have the airtime, go for it and perform. I think that the readings were a success.

People always bemoan the lack of a "literary culture" in South Africa, which they blame for everything from low sales to the lack of interesting stories. What's your take? Clearly, if you begin a new press, you've realised that there is a group of people interested in writing/interested in reading who are not catered to?

It's always easier to bemoan than to do anything about it, I also use/d to do that a lot. But then there is a point when you start feeling bored, which I always reach rather soon. As for the lack of interesting stories, or the lack of quality stories, I think it's a problematic statement as the current book market clearly does not produce for the large audience in South Africa but for a small mainly white middle class in South Africa. There are a few new imprints such as Sapphire Press or Nollybooks which start to produce popular literature, stuff that is easy to read at little cost. Publishers from Nigeria say that lots of different publications are sold in Lagos in all sorts of places, in corner shops, hair salons, etc. I think that this would be important for book selling culture in South Africa as well, to leave the high price shopping malls and go to places where the people shop. And publish books that people want to read. In our independent publishers network meeting Bibi Bakare Yusuf from Cassava Press in Abuja mentioned the example of the legendary Pacesettter Macmillan series.

And then, how can there be quality writing if there is no large reading public with access to books which are affordable? Don't fool yourself, it's not the critics (sorry, Darryl and Percy) who will decide what's going to be published or not. It's the masses who read and buy the books. And I find this obsession with quality, quality paper, quality writing, quality editing, depressing, as it also stretches into the realm of language, as if language has been devised as a straight-jacket system to torture human beings into who unfortunately happen to use it (and hey, we tend to forget that the one thing that never never should ever possibly happen is a lack of language use – while I am afraid to be proven wrong, looking at dystopic novels projecting a world with human language restricted to the use of certain phrases, like newspeak …). I will digress here some more about language and publishing. What I've experienced, when it comes to publishing African languages is a depressing fact that everyone seems to first look at problems of codification, that is, putting spelling conventions first and imaginative use of language second. At the same time, it's important to remind us that the shape of today's codified languages is a result of a process of nationalisation and homogenisation. For instance, in German publications around the turn of the 19th/20th century, different standards in spelling German language were abundant. The process of language standardisation goes hand in hand with nationalisation, but it takes education and language institutions a long time to agree to standards – but you won't get arrested for breaking them. I find that this field is one of the few remaining spaces for politics in its true sense, for creating antagonism in a public space, using the liberty of the writer and confronting others with your language production. That's another reason for keeping the language in the book "Emzana Shack Recollections" as it is – ungrammatical English with spelling mistakes mixed with Tsotsi-Taal.

So, I think it's about publishing what's there, with or without soiled grammar and mis-spelling. By the way, recently I started to become interested in mnemonic tricks around correct spelling in second language speakers: I remembered how I use/d to memorise the spelling of "immediately" – pronounced in German "im-maidee-aah-telly" – when a Zulu speaker told me abut his memorising of the word "question" as "lateral click-westion".

Publishing in history is and always has been one of the most important education tools, after the Germans burned all available books during Nazi time, the Rohwolt publishing house created after the war a paperback series which were named after it's production method, the rotating press: rororo, an idea they got from publishing in the US.

So, what to do in South Africa today? If publishing houses don't have the capacity to read each and every manuscript which is sent to them? And if special incentives are needed to elicit publications in the African languages? I think that there never is a lack of interesting stories but that publishing houses and literary critics maybe don't have enough time and energy to read and appreciate manuscripts and to commit grooming young authors. Or, for schools to pay attention to talent and to promote it. Same with visual arts, by the way. Everybody is waiting for once-off literary talents, but nobody wants to acknowledge that artists working in any medium need lots of time and support by and interaction with the public and other creatives to actually nurture and mature their writing in order for it to become "interesting". Recently I read somewhere that anyone can beat a lack of talent with hard work. It always is about hard work.

I also want to ask you about which SA writers – and books you are reading, in general.

I like to read everything that comes my way, there are many writers from Southern Africa which I really like. To name the authors of the texts which I've sent to Sicak Nal, translated by its publisher Sureyyya Evern into the Turkish language: Fezisa Mbidi, Goodenough Mashego, Anton Krueger, Grace Musila, Achal Prabhala, Martin Njaga and Welsey Pepper. There is always more that I want to read. My all time favourite author is the Hungarian author Tibor Dery, who wrote this wonderful novel "Mr. G. A. in X" which you really need to read yourself.

'The Ballad of the Black Gold'

Keeping with the oil theme, here's Talib Kweli, featuring his frequent collaborator Hi-Tek and Imani Uzuri, from June 2010.

"We can handle the truth. Can you handle the shame?"

I interviewed my colleague at SUNY-Oswego, Faith Maina, just as the story broke about Britain's involvement in human rights atrocities in Kenya. Faith was a young girl during the Mau Mau uprising, and her father—a teacher—was detained twice; afterwards, he could only get a job as a "boy" in the city. Her family also lost their lands, in retaliation for a suspected murder of a "white man or a chief [who was friendly to the British]." I asked her to comment on the significance of the trials and the case brought by four Kenyans against the British Foreign Office, for her and her family.

Faith began by telling me about the significance of Caroline Elkins' book, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya. Imperial Reckoning intended to present a revised history of Mau Mau insurgency, uncovering the colonial myths about 'civilizing' the dark continent—building schools, hospitals and railways—and exposing the manner in which this 'mission' gave way to the savagery of imperial self-preservation. It details the atrocities committed by the British colonial system, including the colonial office in London, the colonial government in Nairobi and the British settlers, missionaries and businessmen in Kenya. Five years ago, when the book was published, Faith "read it from cover to cover because it was simply 'unputdownable.'" Elkins' book "validated those stories that my grandmother, Njeri wa Kagunya told us, and put them in a policy perspective so that I can now really understand the pain of the unfortunate relatives, friends and neighbors who had to endure the British 'civilizing mission.'"

Faith points out that when the book first came out, certain British reviewers reacted with the expected denialist-stance, indicating wider, more pervasive attitudes towards imperial war crimes. In particular, Betty Caplan, who critiqued Elkins' book in the Kenyan press, cited Imperial Reckoning as an example of what goes wrong in "revisionist" historical accounts. Caplan's review, titled "Pitfalls in writing modern history" (published in March 7, 2005), claims that the people interviewed for the book "had decayed memory," and that any brutality was carried out by the Kenyans. In fact, and old geography coffee table book I saved from the rubbish dump, Africa Aeterna: pictoral of a continent, documents the Mau Mau uprising as having employed a "fearful mixture of primitivism, secret societies and of borrowings from the European arsenal of psychosexuality" (text by Paul Marc Henry, trans. Joel Carmichael).

We also spoke about the role played those Kenyans co-opted by the British. Faith names the Michuki family as "the subject of [her] grandmother's scorn" and "some of the biggest beneficiaries" of the colonial period, at whose hands her family incurred many losses. She explains that the Kikuyu used to rule through a non-hereditary council of elders—women, in particular, "looked forward to menopause," because they would be invited to the council as elders. When the British came, they instituted a different system of rule: they elevated some people, according to their "friendliness." People "like [current MP, John Michuki]'s father" were made the "chief," and his descendents (following the new British system of inherited power) continue to enjoy those privileges.

Michuki Sr. earned the name "kimedero" (clippers) because he had reportedly castrated many men. Michuki Jr. has been an MP of her constituency "for nearly 30 years, or since [she] can remember," and one of the richest men in the country, buying votes for his continued stay in power. Meanwhile, the village women were made to dig the deep trenches and put up the barbed wire that "secured" them from providing sustenance for the Mau Mau. Their confiscated farmland was used for coffee, sisal, and pyrethrum plantations, and they still haven't seen it returned.

–Neelika Jayawardane (Mohammed Elsafty on camera)

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers