Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 555

March 6, 2012

The Jazz of Samuel Yirga Mitiku

I was in Dubai recently, working on a documentary, and on the way back to Cape Town I visited Ethiopia to see some friends and experience some of the Ethio-jazz music I had fallen in love with ever since I first heard Mulatu Astatke and the "Ethiopiques" compilations. Even though I had high hopes, Ethiopia completely exceeded my expectations. On my first night in Addis, I was lucky enough to see an Ethio-jazz funk band called The Nubian Arc play live. For me the standout performance was by Samuel Yirga Mitiku, a young piano prodigy, who also plays in the acclaimed UK-based band Dub Collosus, known for their blending of dub and Ethiopian traditional music. Samuel's solo stuff is particularly interesting, as he revisits traditional Ethiopian folk songs, with their unique scale progressions and ancient, mystical sounds, giving them a contemporary jazz interpretation. You can sense in his interviews that his aim (like Mulatu before him) is to preserve Ethiopia's rich musical heritage, and after listening to those fingers play you know it's in good hands.

Shit people don't say about shit

Short documentary on "businessman-turned-sanitation-superhero" Jack Sim who wants to bring toilets to the 2.6 billion people who don't have them (a large chunk of them in Africa). He wants to talk about shit people don't say. Best line: Sim wants people without toilets to desire them 'like a Louis Vuitton handbag.'* The film seemed to have been removed on vimeo. As soon as the video is up again, we'll put it up again.

Shit (some) South Africans say

When the ubiquitous "Shit (People) Say" meme was still popular, and after seeing the genuinely funny Shit Nigerians Say video, I thought about making a video myself about shit South Africans say. Then I saw that someone had beaten me to it. Watching it, I literally laughed out loud, but for all the wrong reasons. The rest of the time I was mostly just cringing.

The most obvious critique (besides the fact that there is almost no comedic or satirical value) is that the video is called "Shit South Africans Say" and yet it should have been called "Shit some English-speaking White South Africans say." The only Black guy in the video is the one who the lead male character said was "checking him skeef" (that is, looked at him funny).

This blatant error would have been forgiveable if it wasn't made by an actual commercial production company, Mercury Productions, whose clients include Levis, Coca Cola and The City of Copenhagen. Surely they could have come up with something that was a little more representative and funny. If not, they could have at least named the video in a way that doesn't propose that all South Africans sound like a relatively small portion portion of the population. Somebody should let Mercury Productions know that there are Black people in South Africa too (besides the "bergies" or homeless people they refer to in the video). South African film has a long history of exclusion, and it's really frustrating to see this being carried forward into the Youtube age. But then this is South Africa.

However, I found this low-fi DIY video made by two young girls who call themselves KK and MM. Despite the poor production values, it's a lot funnier, and way more genuine. It's also a lot more aware of shared South African experiences that cross race and class barriers. There is still hope:

The Little Book of Terror

[image error]

It was Daisy Rockwell's "New Hat," a painting of Nigerian "underwear bomber" Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab that caught my eye. In her portrait, the young Umar tries on a new black woollen cap, one with the Nike swoosh jauntily embroidered to the front, while on a school trip to London. His fingers are engaged in the action of pulling down the sides of the cap over his ears; the collar of his warm jacket is upturned against the autumnal chill. Around him, the Indian colours of fading summer—golden yellow, burning orange—halo the darkness encasing Umar's figure. His eyes have that reticent inwardness already. It is that same immobilising sadness we came to recognise in his terrorist mugshot, after he was accused of attempting to blow up a Detroit-bound aeroplane in mid-flight, with explosives hidden in his underwear.

News accounts recreating the Mutallab family's history repeat the same tropes, marvelling at how the boy who came from privilege—from one of the richest and well-connected families in Nigeria, in fact—could have ended up as far from his father's expectations for him as this. Wall Street Journal, like other venerable western news outlets, fell to speculation: when the "lives of the 70-year-old father and the 23-year-old son shows they were shaped by similar experiences and shared many traits, including a withdrawn seriousness and devotion to Islam," why did one embrace the separation from suffering that capital accumulation permits, while the other developed a deep level of compassion for the poor, and for the afflictions of fellow Muslims in Palestine, Iraq and Afghanistan?

Rather than fall into the sort of pop-psychology that claims to sort out why the children of the well-off (Osama bin-Laden included) may find "radicalism" attractive, Daisy Rockwell's "cheeky little volume" of paintings and minimalist essays, The Little Book of Terror, offers a series of "big-name, international rogues" as well as the small fry caught in a big net. But, as Sepia Mutiny reports, "the feeling of uneasiness comes not from these over-chronicled villain archetypes whose images we've all seen scattered over televisions a hundred times over." Instead, that unease comes from the realization that "The State is…a makeup artist," as Amitava Kumar writes in the introduction to the book: the theatre surrounding "the bad guys" portray the accused as the "shabbiest" of actors with the "worst lines." But beyond the re-plays repeated on CNN, we also see that the State is skilled "at presenting us with people who come to us stripped of any sign of place or past": this way, we only see terrorists and terror without a contextualising history.

Rockwell works from some of those highly publicised photographs for many of her paintings, giving the captured people a depth that photography and the State's vision of them often robs. She writes, in an email correspondence, "I have been interested in Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab for some time. Looking through photos of him on the internet, it was almost hard to pick which one to work with because he looks kind of sad and lost in all of them." Her fauve painter's techniques capture the "ordinary teen" who sported jeans and T-shirts, track suits, headphones, and rode a red-and-blue motorbike too fast sometimes. Her painting also reveals a significant moment in the life of a young man: he has found himself in a location where, perhaps, his limited understanding of subjectivity intersects with power structures that had over-determined the fortunes of vast swathes of humanity. It is far more than he is ready to face. Here, in this photograph, Rockwell points out, "he seemed excited to model his new Nike hat, and perhaps excited to be in London." In a way, he had too much understanding, but little wisdom or equanimity. "I felt like that interaction with Empire might have somehow informed his eventual decision to attempt to make himself into a human bomb."

Foxhead Books, Rockwell's publisher, calls her book "a secular missal." But rather than a "compilation of piquant essays" and images, I think of Rockwell's The Little Book of Terror as an eulogy to freedom, but also, an invitation to a meditation on compassion: in this collection of terrorists great and small, there are portraits of the unlikely, and the obvious (one may ask, faux-ironically, where the Rumsfeld, Cheney, et al might be).

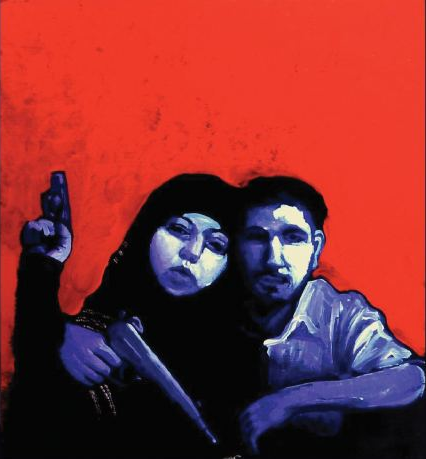

On the cover, a couple with his and her pistols: hers, a dainty one barely larger than the tight ball of her fist; his, a lengthy-barrelled phallic affair. They pose together in a reverse of the pose that Princess Diana and Prince Charles did for their engagement photo: she before him, he with her arms around her hijab-covered shoulders. The intimacy of the danger they share is palpable, across time, medium, and the misunderstandings between us and them. Rockwell says (on Sepia Mutiny) that this is a portrait "based on a photograph of the young woman who allegedly suicide bombed the Moscow subway in 2010. Her name was Dzhanet Abdullayeva and she was seventeen years old. The photo was a self-portrait of her with her husband, who had earlier been killed by Russian forces." Rockwell has a distinct memory of when she first came across the grainy photograph of them on the cover of the New York Times. She was "at a rest stop somewhere in Vermont. It's the kind of grainy, low quality self-portrait people use on their Facebook pages. I couldn't get it out of my head, which is usually how a painting starts for me."

Rockwell's paintings evoke memories of language primers found throughout South Asia, and "old Bollywood posters hand-painted by artists with a keen sense of the fantastic," as Amitava Kumar writes. They also have the horror-attraction characteristic of the abstract expressionists and the fauves: in her portrait of Taliban leader Mullah Omar, though himself darkened in indigo and violet cloth, a field of fire-cracker brilliant flowers engulfs his shadowy figure, highlighting his estrangement. Then there is Charles Grainer and Lynndie England, Abu Ghraib torturers, "enjoying a pleasant moment": their faces are inexplicably green, and England's eyes sealed shut in the pleasure of that elusive moment. The caption accompanying John Walker Lindh describes him as "the ultimate foreign exchange student," whose "Arabic is reportedly quite good." Mohamed Mahmood Alessa had a fight with his mother before he left on a misguided mission: he wanted to take his beloved, Tuna Princess, with him. In the painting, he luxuriates in bed with her: she is generously furred, long of whisker, and large of eye, much like Alessa himself. We learn that his mother did not permit him to take the cat. Instead, he left with "a large bag full of candy from his parents' deli," which the FBI confiscated.

Rockwell has been writing for Chapati Mystery (my other fave blog, run by Manan Ahmed, aka Sepoy), using the pseudonym Lapata. "Lapata" in Hindi and Urdu can mean 'anonymous', but also references the idea of something that has 'disappeared'. Rockwell writes, "A part of me also wanted to escape the legacy contained within my real name, I suppose, that of my grandfather, Norman Rockwell. I wanted to make art without the burden of expectations that come with that identity."

I would also posit that she writes for those Others who have been disappeared—by the media, by the state, by the Global War on Terror. When I think of her grandfather's portraits, beloved in diners throughout the Midwestern states of my drive-through American youth, I remember that his work, too, involved painting the fantastic—though his subject matter appeared to be hyper-real. Here, his granddaughter Daisy paints the hyper-real as scenes from a seemingly unlikely world, just so that we (who do not want to know this real) can comprehend the fantastical nature of the times in which we live.

Rockwell's paintings will be part of faux-tourism pamphlet included with Kanishka Raja's installation Switzerland for Movie Stars at the Armory Show next weekend. Drop by and take a look at the Armory Show here.

Her work will also be shown in Beckett, MA. Join Loo Gallery in the Dreamaway Lodge for a delicious brunch opening on Sunday, March 11, 2012. The event is from 10:30 AM-3 PM.

Watch the book trailer here.

Julius Malema's History

Last week, after Malema was expelled from South Africa's ruling party, we went back and looked at our archives to see how we've blogged about him and his politics. Here's a sample.

From the go we recognized that although Malema is very much a creation of South Africa's media, he is the ANC's responsibility. Early in 2010, Sean wondered "how long it will take before the ANC's leaders kick Malema out."

In May last year we linked to Hein Marais's description of the "work-in-progress" that is Malema:

a politics that accommodates social conservatism, lumpen radicalism and grasping entitlement … a political experiment within the ruling African National Congress.

In November, Jonathan, writing at the time of Malema's initial suspension, suggested that Malema's

rise was marked by an occasional penchant for tapping the zeitgeist: needling the nerves of big capital and the entrenched political elite (both black and white), while concurrently channeling the very real frustrations of poor and increasingly marginal South Africans. In a very real way his causes tapped the desperation of those trapped within the structural violence of South African poverty. Ultimately, he overstepped, over-played, and was caught in a web of his own making. He is, for the minute, politically a dead man walking, although his shadow will continue to fall across the politics of the ANC in the run-up to Mangaung, and beyond.

Jonathan then concluded:

The twittering classes, never a good barometer of South African opinion, are now ablaze with back-slapping mirth. And some analysts are overstating things. But, the material conditions that grind the dignity from so many South African lives will be reproduced tomorrow, and the next day, awaiting a new "Juju" to give them voice.

And then there was comic artist Nathan Trantaal who told AIAC:

The South African mainstream likes to have a black man they can laugh at, a black man who says something that is so obviously wrong they can jump at the opportunity to lampoon him. Take Julius Malema, for example. I don't particularly like the way people talk or write about him. I mean, he's a dumb bastard, but there's just something very uncomfortably self-righteous about it. Don't call a black person dumb in the media every single day. "Dom Kaffir" [dumb kaffir] is what the old government used to say. And whether it is deliberate or not, it has that undercurrent.

And the post we intended to write as a reaction to South African author Jonny Steinberg's recent analysis in The Guardian, but never did, would have sounded something like this:

In this article, Steinberg puts his finger on the hysteria around Malema: the extent to which Malema highlights tensions in the ANC, all of which seem to be coming home to roost at this crucial moment, only serves to illustrate that his views are rooted in white paranoia. Malema's real influence might be overstated, but as a figure in politics, he is significant in what it says of the fault lines in South African politics, but also of the fault lines along which the media reports on politics. Malema is portrayed in the manner of the bling and Cribs obsessed hip hop star. We all know that the danger of rap was subsumed by the siren call of consumer goods — the fearsome lyrics eaten up by clown-like distracted children. Similarly, once Breitling watches were dangling on wrists, Malema no longer allowed those South Africans relaxing at the swimming pool to enjoy it without the threat of it being taken away. Steinberg is saying: we like the caricature, because we know we can tame it. In Malema, we recognize the child who will eat too much ice cream and puke. But we became scared when said child acquired a certain momentum…driven by our own attention to him. So who converted the child to threat? The author's own ilk. Thus, the scar tissue Malema left in his wake is found on the media's fragile self-image (not on the 'country', as the title of Steinberg's piece suggests). The media is to be held at least partially accountable. Unfortunately, a reading of reactions to Malema's expulsion from and by the ANC in recent South African (and foreign) media shows little soul searching on their part.

Plenty Koko

We didn't expect anything else: the video for FOKN Bois 'Sexin Islamic Girls' goes all the way. March 6 is Ghana's Independence Day — which means we have an excuse to post it.

March 5, 2012

Music Break. Gasandji

Thrones no one wants to sit on

Gonçalo Mabunda's chilling constructions are now on display at the Jack Bell gallery in London. His thrones (above) and faceless masks (below) are made from weapons used in Mozambique's civil war. These designs make dark mockery of ergonomics: you wouldn't want to put these masks on your face. There is some uncanny resemblance to Modernist assemblages, and the gallery notes make a connection with Cubists. An instructive comparison is Jacob Epstein's The Rock Drill (1913-15), a prophetic monument to the horrific potentialities of modern industry. Mabunda's work suggests a similar comparison, between the intensive wastefulness of war and the difficulties of post-conflict community projects. Above all, it seems a grim satire on the useless objects which adorn bad leadership.

Abdoulaye Wade's praise singer Coumba Gawlo

Senegalese griot singer Coumba Gawlo Seck is a rising star both in her native country and in Europe. People also occasionally ask her about her political opinions. What makes Coumba Gawlo interesting is that she is a supporter of embattled Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade. (He is so unpopular that he has been forced to face a second round of voting against a divided opposition later this month.) The thing about Coumba Gawlo is that she feels compelled to defend Wade at all costs. This is certainly at odds with the political stances of most of Senegal top musicians (if you don't include Akon).

In a recent interview on Senegalese TV, she quoted her grandmother about the meaning of true friendship and loyalty. Coumba Gawlo was asked why she's not part of the musicians and opposition's Y'En A Marre movement in protesting president Wade's run for another term: A man wants to know who his real friends are, so he goes knocking on a first friend's door. "I've killed somebody," he says. The friend responds he doesn't want anything to do with it. The man goes over to a second friend's house, knocks on the door and says: "I've killed somebody." The friend gets angry and shouts he should go the police, but he won' let him in. So the man goes to a third friend, knocks on his door and says: "I've killed somebody." The friend hears this and invites him in. "You're my friend, no matter what happens in life."

She defends her loyalty to Wade because of his supporting and looking after her from a young age, which pushed her career and made her into the popular singer she is today. "He's like a father to me." But, she also says, "the fact that Y'En A Mar exists, is a sign of Senegal being an open, free and democratic country." She's a praise singer, after all.

The news that demonstrators were killed by Wade's police force, gives her answers an eerie edge.

Asked for her opinion on N'Dour's candidacy, she's defensively evasive.

Which brings me to a recent special on Senegalese music broadcast on CNN's "Inside Africa" program. This is of course part of CNN's ongoing "discovery of the real Africa." Journalist Errol Barnett traveled to Dakar where he met a few musicians, including Daara J Family (more on that later), Doudou N'Diaye Rose and Coumba Gawlo. Barnett's insert on Coumba Gawlo amounts to "a bizarre interview" (in his words). He is basically forced to wait hours outside her dressing room at the National Theater and when he does get to talk to her, he's covered in glitter dust. Anyway, what was interesting is that given that he seems to be in Dakar during these tumultuous times (elections anyone?) he asks her about Senegalese drums. I'm not sure if it's the glitter or the struggle to get the interview.

To talk to musicians about their instruments is fine, but given today's circumstances in Senegal, an insight into the "real" part of Africa they're so eager to cover, a different approach might have given us a more interesting picture.

Watch the full CNN documentary here (in which he also pays a visit to the Daara J Family hoping to learn something about Senegal's music — there's a nice diversion into their engagement with South African choral music — but can't resist zooming in on Nigeria's Afrobeat two minutes in).

Also over the weekend, Arte interviewed Didier Awadi. He was more to the point: "we've killed the youth's hope; listen to the rap albums to understand what's happening."

Cape Town Leather

The Rupert clan of South Africa owns a few businesses that make a lot of money: Cartier, Dunhill, Montblanc and Piaget, etcetera. Their fortunes began with Anthony Edward Rupert, who could not finish medical school "due to lack of funds," but thanks to apartheid magic (and business smarts) he began manufacturing cigarettes in his garage. He eventually built this into the tobacco industrial conglomerate The Rembrandt Group, which made him a billionaire. In the late '60s (think the time of the Rivonia Trials), a scion of the family purchased the L'Ormarins wine estate in Franschhoek in the then Cape province. The family's fortunes continued, with the addition of another wine estate, La Motte. One could say that Franschhoek's current stature is probably owed in large part to the efforts of the Ruperts to promote the district as a little corner of France, replete with cheeses, fruits, herbs, mushrooms, nuts, olives, coupled with the exotic appeal of the bush: ostrich and crocodile steaks. Of course, there's also the poorly paid coloured labour, but that's not in brochures intended to lure visitors.

Recently, one of the clan, Hanneli Rupert, opened a leather-goods outlet in South Africa, naming it "Okapi". And the PR is charming, though not aimed at anyone who has read any postcolonial critique in the last forty or so years. It begins harmlessly enough, with some inane nonsense about the Okapi being "the African Unicorn"; that "the elusive forest dwelling creature…has been hiding for millenia waiting to be discovered"; and that "she can shift shapes and as you navigate through the Okapi adventure try and figure out where she is hiding." The sales pitch includes some predictable lines about providing "job opportunities" and "growth," with "locally-sourced" materials, etc.

And then it got annoying. Apparently, the okapi "lives amongst the God's and Goddesses of Africa and over the years has taken on many of their powers."

Surely, the PR team that can be hired by the likes of the Ruperts knows about the proper use of plurals and possessives (not to mention using commas to separate coordinating conjunctions).

As I wandered to the "Campaign" pages, I began to wonder what exactly Hanneli meant when she "draws inspiration for her designs from the mystical traditions of Africa and its primordial beauty": is the primordial-quality of mystical Africa encapsulated within the exposed breasts of the black models, positioned (rather primordially, I must admit) amongst lianas, dugout canoes, a lily pond, and some strategic kudu horns? The promo video, where an all white crew photographs a (very beautiful) set of half-naked black women is the most troubling.

I can't say that I'm terribly surprised, since this is, after all, South Africa. And judging by the inspiration for the logo's typeface ("designed by hand for the brand. It's aesthetic was inspired by the art nouveau era often associated with an unchartered Africa. It was also during this time period that the Okapi was first discovered in the Belgian Congo"), I can see that some people haven't listened to Mbembe lately (or learned about the difference between its/it's: one is a possessive – its; the other, a contraction – it's).

In any case, even if the workmanship is stellar, the designs don't stand up to offerings by Longchamp, Dooney and Bourke, Cole Haan, or the ethereal Bottega Veneta's leather goods. If I'm gonna strap a thousand-dollar piece of cow to my shoulder, it'd better look more cutting edge than the offerings by Okapi.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers