Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 393

July 31, 2014

What is happening to Mombasa, Kenya?

Historically known for a relaxed pace of life, Mombasa on Kenya’s coast has also been a regional hub for business, trade and tourism. Its population is diverse; recent figures indicate the city is divided between Christians and Muslims (59% and 41%, respectively), with one-third of inhabitants also originating from outside of the region. Along with its diversity, Mombasa has also been associated with experiences of everyday tolerance.

In the past year, this seems to be changing. Mombasa has come under particular scrutiny with reports of a police raid on a mosque and the incarceration of more than 100 youth, targeted killings of prominent Muslims leaders, shooting in a local church, heightened international travel advisories, and the evacuation of tourists by UK-based tour operators.

Serious attempts to understand recent events require attention to local differences and how they shape unrest. I suggest there are three broad differences that must be considered.

First, religion. Kenya is predominantly Christian, but Mombasa is situated in a region where the dominant way of life appears intimately bound to Islam.

Second, place of origin. Place and identity are closely linked in Kenya. Mombasa is part of the ‘home’ areas of coastal ethnic groups, controversial due to land ownership by those originating from outside the region. However, the city challenges discourses of autochthony, with a growing number of inhabitants from ‘upcountry’ Kenya, but whose birthplace, occupation and children belong to Mombasa.

Third, ethnicity. While arguably dynamic and negotiable, ethnicity remains an organising principle for political contest in Kenya, as people perceive that the benefits of political office follow ethnic lines.

Through recent events, these differences have not provided for the emergence of clearly defined victims and perpetrators. Muslims identify disadvantage within a national context dominated by Christians, reinforced by targeted anti-terrorism efforts. Christians in Mombasa perceive disadvantage in a region dominated by Muslim politicians. Coastal ethnic groups see themselves as continually marginal in national political and economic structures, while ethnic groups constituting the national ruling coalition find they are a minority in the region.

There is a sobering potential for different explanations of insecurity to resonate in ways that enable multiple groups to identify as victims. This is particularly concerning as identities converge into broader fault lines, for example, Christian and upcountry versus Muslim and coastal, producing captivating, simplistic narratives of persecution.

While stability does require addressing direct causes and conditions of violence, both internal and external, it also hinges on the popular narratives that define disadvantage, and shape people’s willingness to speak and act. Competing views of disadvantage point to a pressing need for action by those in positions of power: action that acknowledges multiple differences that resonate locally; action that presents a transparent and just response to insecurity across these differences; and action that values and upholds the right to life and security of all denizens of Mombasa.

The winners and losers of the platinum strike in South Africa

On January 23 this year the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), a firebrand breakaway of the COSATU-affiliated National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), took an estimated 50,000 mineworkers to the plateaus of Rustenburg to demand a R12,500 (about US$1,250) basic salary.

For months – without pay, their families going hungry and their spirits waning – the workers were assiduous. While the mining companies were spurting money, they too were not budging.

Five months later, the workers are estimated to have lost between R42,501 and R52,000 in pay. The business journalist Alec Hogg argues that it will take workers over a decade to recover this amount. The mining firms, on the other hand, are estimated to have lost between R11 billion and north of R24 billion, depending on who you ask.

On Monday 23 June, the workers and firms announced that they had reached agreement and clinched a 3 year deal. The two lowest bands of categories will receive a R1 000 increase for the first three years. Other categories will receive between 7.5% and 8%; benefits and allowances will be fixed or rise with inflation.

A question many are asking is who won the five-month and 26-day battle?

Critics of Amcu (and labour in general) have weighed, calling the deal a “hallow victory” for Amcu (hint: a loss). Mr Hogg, for example, points out that: on January 29, six days into the strike, “the mining companies offered increases of between 7.5% and 9% with the higher figure tagged for the lowest paid workers. This offer, incidentally, was increased on April 17 to between 7.5% and 10%. If [Amcu] had accepted the offer received six days into the strike, the lowest paid worker’s monthly earnings would have increased by that 9%, or R644, to R7 798.”

According to Mr Hogg, the difference between the offer made by mining firms in January and the offer accepted five months later is a meagre R356.

In my view, any analysis of the gains and losses made by workers on purely financial terms will be insufficient, if not utterly flawed.

While one could properly quantify the losses and the meagre, almost negligible, economic benefits of Amcu’s exercise, the extra-financial gains are weightier and more significant. The answer to the question ‘who won’ requires some digression.

In 1912 the South African Native National Congress – now African National Congress – was founded to “address the just grievances of the black people” with the Union Government. Shortly, in 1913, the Native Land Act was promulgated, further aggravating situation. Natives were rendered landless pariahs in their country of birth. More policies were written and laws passed which further alienated natives. In 1948 the voting minority gave green light to a more brutal regime, entrenching race-based discrimination, repression and economic exclusion.

In 1955 the Congress of the People agreed to draft a Freedom Charter. That too did not help. Instead of making concessions, the regime tightened its noose. It offered black South Africans a deal: to leave South Africa and gain independence in homelands. Liberation fighters rejected this deal and opted, instead, to intensify the struggle. They were either killed or thrown into jail, where many spent between 10 and 27 years.

In 1990, after scores of the movement’s members had been thrown in jail, tortured or slaughtered by the regime, the movement agreed to a deal. To any observer, the deal was a loss for the movement. The demands for land, for nationalisation or common ownership of strategic sectors, which had been at the centre struggle, were stacked off. For a short while the newly-formed democratic government even went to bed with the apartheid regime in a “Government of National Unity”.

With the economy in the hands of apartheid beneficiaries (white and some black), the apartheid status quo of economic, social and cultural exclusion persists. Black South Africans remain wanting in rural areas, outside the economic epicentre. Basic services – like education, clean water and health infrastructure – remain concentrated in former “white areas”. Blacks must thus assimilate themselves into social, political and economic cultures. Except, this time, they do it for carrots and not to avoid sticks. Twenty years after democracy, many still ask who won the 82-year battle.

The answer is, in my view, more complex than demand versus gain. While (black) South Africans attained very of little their social, cultural and economic demands, their bargaining position has improved considerably. As equal citizens in a democratic republic – even if as poor as church mice – we wield significant political power and socio-cultural potential. The constitutional settlement negotiated between 1990 and 1996 is a springboard on which we can launch ourselves to a better deal –– that is if we try hard enough.

Comparably, mineworkers are in a terrible bargaining position. For centuries mines have been the driving force behind the South African economy, with cheap (migrant) labour as the engine. The system of race-based oppression was constructed, partly, to keep black mineworkers outside the economic epicentre.

Further, economic laws of supply and demand dictate that mineworkers (who are in oversupply) are disposable.

The bargaining position of mineworkers is further weakened by the alliance between labour and the government. Leaders of COSATU often capitulate under government pressure and give in to “market demands”. The government and the market are synonymous, which makes labour subservient. This is where the Amcu strike comes in.

Having persisted for 5 months, and made it out alive, workers have made their biggest show of strength since 1949. They have also reduced the platinum stockpiles which serve as a cushion for mining firms. This is a benefit of the strike which is not measurable through economic models.

The strike serves an even greater purpose for Amcu (and labour in general). It has solidified support and showcased Amcu’s tenacity under pressure. Because Amcu is apolitical (and thus does not have the support of the tripartite alliance or the government), the strike was driven purely by workers for workers’ interest. This should increase Amcu’s support base.

The strike is the start of a new era in South African labour politics. COSATU has been plagued by infighting. The interests of labour appear to be taking the backseat as the rank and file of the alliance scrambles for political power and government positions.

Amcu, on the other hand, is an outlier. By rejecting politics, it found a niche in workers who are less bothered by who is the president of the day. These workers are concerned with their own interests –– the politics of bread.

This makes Amcu a wildcard, which is why market-minded academics, pundits and other political players were against the strike. “The market” takes comfort in knowing that the ANC-led government has control over the labour movement. Very often, the government will intervene and labour backs off. This was impossible with Amcu because it does not have a stake in government. If Amcu had succeeded, it would have further eroded ANC support by uniting workers outside the alliance’s reach.

The fact is Amcu came out stronger, with the trust and support of workers. The union showed potential members and supporters that it was single-minded and capable of withstanding national and international pressure. The government, which is usually in the deep pockets of tax-forking mine bosses, has also awoken to the potential power of a united worker front.

Amcu is the clear winner! While it may be true that workers made an economic loss that may take years to recoup, they have also made significant political gains. These gains are a springboard for future shows of strength and they improve the bargaining position of organised labour in the country.

Whether the Amcu will grab the opportunity to consolidate its gains by unifying and rallying worker outside of the alliance is the first question we should ask. The second is whether it will resist the urge of politics, and thus remain independent and incorruptible, at least politically.

* Photo Credit: Siphiwe Sibeko.

July 30, 2014

White Schools in postapartheid South Africa

It’s a little over two decades ago that South Africa’s Whites Only schools began to ‘welcome’ Black students (African, Coloured and Indian) students into their classrooms. Guided by the official principles of multiculturalism and equality, many a White teacher witnessed his or her classroom diversify. In response, many of them adopted the rhetoric of ‘color blindness.’

Ever since, the media has exposed various incidents that showed that (surprise) color-blindness was neither real, nor desirable. Race, it turned out, was quite a real thing in the average Rainbow classroom. Examples of violent incidents abound.

In 1999, the country’s Human Rights Commission, for example, raised alarm bells about widespread physical violence and death threats faced by black newcomers in formerly white public schools. Later, a bunch of white Limpopo parents literally barricaded their school gates. More recently, one teacher in Bloemfontein was suspended for using the racist “Kaffir” slur (the South African equivalent for “Nigger”). Another white teacher compared black people to demons. Late last month the Human Rights Commission announced that it was wrapping up its investigation of another school in Bloemfontein, where teachers not only called pupils baboons and monkeys, but also told them to go back to their township schools instead.

Pupils at the school in Bloemfontein said teachers told them to go back to the black schools in the townships because their parents could not afford to pay school fees, and that they would never succeed in life and would end up like their parents who work in chain stores.

The ways in which white parents (through governing bodies) and schools’ leadership structures resist racial integration and uphold white superiority in former white schools is one of those things that everybody knows about and only a few will deny or talk about. A 2010 study on South Africans’ attitudes to social integration in schools observed: “It is widely believed that not many white parents feel comfortable letting their children share the same school with children of other races, especially African children.”

In most former white schools, however, racial hierarchies are not so much maintained and reproduced by the extreme physical, vile and verbal kinds of violence that we encounter as ‘incidents’ in the media. Instead, white superiority is more commonly inscribed on students’ identities in more subtle, implicit and ‘every day’ ways, through race, class, language, hair, style, culture, sports as well as by the refusal to hire more Black teachers. It’s the type of assimilative push towards whiteness, a symbolic kind of violence, which may be more difficult to recognize as a human rights issue, but one that’s institutional and that affects thousands of Black South African children every day. Yet compared to the ‘baboon’ and ‘barricade’ type of racism, you got to dig much deeper to read about the experiences and effects of symbolic violence. What it feels like when your mother-tongue is forbidden, your culture fetishized or when your hair style and accent deemed too Black. Or what it’s like when you know your teacher considers you less smart than you are, just because maths (in your second or third language) takes you a tad longer to digest.

When white middle class superiority is woven into the fabric of the institutions, you can hardly blame white students for adopting similar attitudes. In this 2004 study by Battersby, one Black student lamented that:

there are certain, few black kids that are accepted by the white kids in this school. You know what I’m saying? And the rest are just another black kid that you walk past in the passage, that you don’t give a damn about. And no one says it, but it’s just there. And no one will say it.

And in this 2010 study, Ndlangamandla quotes a student as saying

the fact that eh, only one Indian person is doing Zulu in the … is really bugging me because you know, eh, a lot of black people are doing Afrikaans. We are trying to adapt to eh, white people’s ways, but they don’t wanna learn something new or learn our language and that makes me feel bad, because I am proud to be African, you know.

As the sociologist Crain Soudien argued in his 2012 book, without other forms of support, students are likely to leave such assimilationist environments “with feelings of alienation and discomfort.”

More books and studies on the topic can be found here, here and here.

* Photo Credit: Hasan Wazan.

The World War One in Africa Project: What happened in Africa should not stay in Africa

For the next four years, the world is celebrating the Centenary of World War I, and once again Africa is not invited to the party.

The story of Africans’ involvement in the Great War is unheard of outside of academia, and thus remains to be told: the tens of thousands of African lives lost at home and abroad, defending the interests of foreign powers and the lives of complete strangers; the forced recruitment of African soldiers to fight Europe’s war, and of African workers to replace the labour force gone to the front; the battles between colonies pitting Africans against each other on their own soil; the reshaping of Africa’s borders and inner workings after the war under new rulers.

It was supposed to be the “war to end war” and yet, by the proxy of colonial empires, it created war where no one cared for it, dragging an estimated two million Africans into the conflict, originating from Algeria to South Africa. Such bitter irony is lost on today’s France, Britain, Germany, Belgium and Portugal, all colonial powers who sat at the Berlin conference in 1885 to finalise the scramble for Africa.

Not only are the commemorations of the First World War becoming resolutely local, but the colour of memory remains essentially white. Even the small steps taken to remember the role of former colonies, like this year’s invitation to African troops to take part in the Bastille Day celebrations, amount to mere pats on the back for spilling their blood obediently.

The reality of World War I in Africa is messier. As early as September 1914, Britain faced a rebellion from some 12,000 of its own South African troops, Afrikaners for whom the Second Boer War remained an open wound, who went on to proclaim a free South African republic, some of them even joining forces with the Germans. And though France praised itself for being able to count on its “Black Force“, it faced significant resistance throughout the recruitment campaigns, which culminated in the Volta-Bani revolt where things escalated into an all-out anti-colonial war in 1915-16.

Yet when looking into Africa’s involvement in World War I, the draft of African soldiers constitute the smaller end of the telescope. Throughout the East Africa campaign, the longest and deadliest part of the war on the continent by far, both Britain and Germany relied heavily on porters, to the tune of four per one soldier. This translated into one million Africans under British command carrying, cooking, cleaning, and dying of exhaustion, malnutrition and disease, in a guerrilla war of short raids and long treks from present-day Kenya to Zambia over the course of four years.

Europe’s 20th century started in 1914, and the yoke of colonialism steered Africa along for the ride. Migration trends were set, economies transformed, borders redefined. The task we’ve given ourselves is to dig this heritage out: not to commemorate its passing, but to restore its meaning. We claim no expertise as we aim to educate ourselves as much as we hope to teach others. In light of current zeitgeists — a morbid obsession with the past in Europe and an unfeigned disdain for anything but the future in Africa — we believe the Centenary to be a fertile common ground for investigating the present. The next four years represent a window of opportunity to connect the dots and discuss the knots, to challenge the boilerplate narrative and change the usual narrators. Let’s unpack what the world thinks it knows, and put what it should not ignore right under its nose.

Join us on Twitter, on Facebook and on our website.

* Photo Credit: Sar Amadou, Wolof class of 1900, Seventh regiment of Senegalese Tirailleurs, June 1917 (by Paul Castelnou)

July 29, 2014

It may be time to drop the ‘world music’ label (and The Brother Moves On has something to say about it)

Last week the second Cape Town World Music Festival (CTWMF) took place, and warmed up a very cold and wet “Mother City” weekend. The notoriously lax Cape Town audience (myself included) got out from under our duvets to check out some of the best bands in South Africa, as well as some international acts, such as Malian guitar maestro Vieux Farka Toure and US singer/ songwriter The Mynabirds.

The festival has had a few ideological bumps in the road to its success. In 2011 the Israeli embassy provided airfare for Israeli artist Boom Pam to fly to the festival, which resulted in much criticism and a call from Palestinian solidarity group BDS South Africa to boycott. Luckily CTWMF seems to have cut ties with the Israeli embassy, which is good. The festival itself, held at Cape Town’s beautiful city hall, was well received by all who attended. However, on another note, we need to ask, why use the dated term “world music” for such a progressive and inclusive lineup?

Acclaimed Johannesburg-based band/performing arts collective The Brother Moves On performed a much- anticipated and moving set on the first night of CTWMF. Near the end of their show they commented on the term world music. Lead vocalist Siyabonga Mthembu addressed the audience, questioning the legitimacy of the term. Guitarist Zelizwe Mthembu, Siya’s cousin, expressed his disdain in our video interview: “The term world music has taken a whole lot of genres and placed them under one category… you can’t do that!” He was quick to add however, that the festival organizers had put together an amazing lineup, and because of that they could call the festival whatever they want.

The term itself originated in Western academia. Ethnomusicologist Steven Feld writes in his essay “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music” that the term was first circulated in the 60s by academics as a friendlier, less cumbersome alternative to ethnomusicology, which referred to the study of non-Western music and the “musics of ethnic minorities.” Although its mission was liberal and inclusive, Feld writes that this reinscribed a binary which separated musicology from ethnolomusicology, the West from the rest: “The relationship of the colonizing and the colonized thus remained generally intact in distinguishing music from world music.”

The 1980s and 1990s saw a proliferation of Western artists collaborating with and drawing samples from artists from the third world, such as Paul Simon and Peter Byrne. This often perpetuated the global power structures that colour the relationships of the West from the rest. In “Sweet Lullaby for World Music,” Feld writes about how The Grammy Award winning Deep Forest sampled a UNESCO Solomon Islands recording in which a woman named Afunakwa sang a lullaby called “Rorogwela.” The recordist, Hugo Zemp never gave his consent, let alone the singer Afunakwa, and the song became highly lucrative, even appearing in commercials for Coca Cola and Porsche. Because of legal loopholes and the recording being labeled as “oral tradition,” Deep Forest and their record label legally owed nothing to the original sources of their hit. The lullaby eventually became sampled again by Kenny G-esque Norwegian artist Jan Garbarek, who misidentified the song as Central African and named his smooth jazz version “Pygmy Lullaby.”

We have to conclude that the term world music is at best dated, and at worst problematic. So, CTWMF, perhaps its time to drop the word world from your title? Cape Town Music Festival has a nicer ring to it. Why clump together the maskandi of Madala Kunene, the experimental afro-rock of the Brother Moves On and the electronic kwaito of Okmalumkoolkat under this contentious label and continue Western classifications of ethnic others on our own soil? In all fairness, the festival audience didn’t seem to be bothered, but perhaps that speaks to a general Eurocentric attitude which pervades in the administrative passageways and cultural hubs of the Mother City.

Photo Credit: Kent Lingeveldt.

July 28, 2014

Tanzania and the Palestinian Struggle

The current conflict between Israelis and Palestinians has once again brought to the forefront the suffering of the Palestinian people. It has reignited the debate on collective punishment they are made to endure as well as the unequal application of firepower by Israel. After close to 20 days of Israeli air raids followed by a ground invasion of Gaza, the casualties from the conflict have been lopsided, with 80% to 90% of the casualties on the Palestinian side being civilians. The death toll has climbed to over 1,000 Palestinians killed and 5,500 wounded. On the Israeli side, 42 soldiers and 3 civilians have lost their lives in the conflict. It begs the question: what is the value of a Palestinian life?

While there are no easy answers to bringing peace in the Middle East, what is apparent to those who dare say it is that Israel policies on Palestine have continued to violate basic human rights. It was partly due to this that many African countries broke off their diplomatic relations with Israel during the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Today however, the landscape has changed significantly, with previous staunch supporters of the Palestinian cause in Africa sufficiently neutralized by Israel’s diplomatic and economic push in the region.

Take the example of Tanzania, which under its first leader Julius Nyerere, provided the moral leadership to the rest of Africa on the Palestinian question. After gaining her own independence in 1961, the country’s top mission was to support liberation of other countries still under colonial yoke, including those under Apartheid in South Africa and Namibia, as well as the Palestinian cause. Mwalimu Nyerere spoke forcefully in support of Palestinian right to self-determination as early as 1967 after the Six-Day War when he delivered a speech on Tanzania’s foreign policy based on principles of justice and freedom for all human beings irrespective of where they lived. This policy guided the country’s foreign policy for many years during his tenure which ended in retirement in 1985. The following excerpts from the speech are relevant to Middle East:

“Our desire for friendship with every other nation does not, however, mean that we can be unconcerned with world events, or that we should try to buy that friendship with silence on the great issues of world peace and justice. If it is to be meaningful, friendship must be able to withstand honesty in international affairs. Certainly we should refrain from adverse comments on the internal affairs of other states, just as we expect them to do with regard to ourselves. ..

“The establishment of the state of Israel was an act of aggression against the Arab people. It was connived at by the international community because of the history of persecution against the Jews. This persecution reached its climax in the murder by Nazi Germany of six million Jewish men, women, and children … The survivors of this persecution sought security in a Jewish national state in Arab Palestine. The international community accepted this. The Arab states did not and could not accept that act of aggression. We believe that there cannot be lasting peace in the Middle East until the Arab states have accepted the fact of Israel. But the Arab states cannot be beaten into such acceptance. On the contrary, attempts to coerce the Arab states into recognizing Israel – whether it be by refusal to relinquish occupied territory, or by an insistence on direct negotiations between the two sides – would only make such acceptance impossible”.

“In expressing our hope that a peaceful settlement of this terribly difficult situation will soon become possible, it is necessary for us to accept two things. First, Israel’s desire to be acknowledged as a nation is understandable. But second, and equally important, that Israel’s occupation of the territories of UAR [now Egypt], Jordan and Syria, must be brought to an end. Israel must evacuate the areas she overran in June this year -without exception – before she can reasonably expect Arab countries will begin to acquiesce in her national presence. Israel has had her victory, at terrible cost in human lives. She must now accept that the United Nations which sanctioned her birth is, and must be, unalterably opposed to territorial aggrandizement by force or threat of force.”

“That is Tanzania’s position. We recognize Israel and wish to be friendly with her as well as with the Arab nations. But we cannot condone aggression on any pretext, nor accept victory in war as a justification for the exploitation of other lands, or government over other peoples.”

Tanzania had established formal diplomatic relations with Israel in 1963 before severing them in 1973, when it recognized the PLO as a legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and becoming the first African country to allow the PLO to open an Embassy in Dar es Salaam. During those 10 years of diplomatic relationship with Israel, Tanzania benefited from development assistance and investments towards agriculture, infrastructure development and security cooperation among others. Regarding this beneficial cooperation he was receiving at the time, Mwalimu Nyerere said “while it [Israel] was a small country it could contribute a great deal to his country since Tanzania faced similar problems to the Jewish state. The two main issues facing both countries, he said, were (1) to build a nation and (2) change the landscape, both physically and economically.”

It is said that Nyerere’s Ujamaa villagization program was modelled after the Kibbutz system and his agricultural cooperative schemes were adopted from Moshav model. Many roads in the main city of Dar es Salaam were built by the Israelis, such as the Port Access road now renamed Mandela Expressway. The Israelis even built their own Embassy there, which they had to abandon in 1973. The embassy building was later taken over by the Americans who moved their own embassy there in 1980 (it was the same building that was bombed in 1998 together with the US Embassy in Nairobi).

Relations between Tanzania and Israel were not restored until February 1995. By then, Mwalimu Nyerere was no longer in power. The majority of the other 25 or so African countries which had broken ties with Israel in 1973 had reestablished them, with a big wave taking place between 1991 and 1994 as a result of the Oslo Accords. Some countries like Malawi, Swaziland and Lesotho have never broken their ties with Israel at any point in time, enjoying continuous friendship throughout the troubled times of the Middle East Wars. Today, more than 40 African nations have diplomatic relations with Israel, with only a handful still refusing to either recognize her (Algeria, Libya, Sudan and Somalia) or yet to establish diplomatic ties with her (Guinea, Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Chad, Comoros, Tunisia, Morocco and Djibouti).

By 1995, Tanzanian foreign policy had evolved from that of liberation and common brotherhood of man, to a new era of “economic diplomacy”. The idea was to make foreign policy a tool to support economic transformation, focusing on “the pursuit of economic objectives, while at the same time preserving the gains of the past and consolidating the fundamental principles of Tanzania’s traditional foreign policy.” However, the effect of this policy change is that Tanzania’s voice on matters such as the Palestinian cause has faded. Many blame not just the change in policy but the current crop of leaders failing to maintain the spirit of Nyerere’s moral leadership. The government is accused of not being quick as they used to be in condemning atrocities against Palestinians, and when they eventually issue statements, they amount to empty words with no concrete actions or repercussions, not even the mobilization of citizens to publicly demonstrate and voice their support as used to happen in Nyerere’s day. In a documentary interview last year, Tanzania’s Foreign Minister Bernard Membe denied any outside pressure or lobby to soften their stance saying, “our support for the Palestinian cause is unwavering. It’s principled and nobody can uproot it. The world is smart and clever. They know these are some of the areas that Tanzania cannot be touched.”

On the eighth day of the ongoing crisis, during a press conference Minister Membe condemned the killings of innocent civilians in Gaza and “called on Israel to stop their ongoing aggression on the Gaza Strip” and also called on “the armed Palestinian groups to stop firing rockets into Israel.” Ironically, the government newspaper buried this condemnation inside another story about plan to take Ambassadors accredited to Tanzania to visit the mausoleum of Mwalimu Nyerere. You can’t make this stuff up. Even Foreign Ministry’s own blog story emphasized the issue of dissolving the FDLR rebels in Eastern DRC and mentioned the Gaza remarks in passing. It was after days of mounting pressure from different corners that the Ministry released a separate statement fully focusing on the current situation in Gaza.

Meanwhile, while the crisis is ongoing, media reports were full of stories about the Israeli Ambassador to Tanzania making the rounds to bid farewell to national leaders at the end of his tour of duty. The story on Gaza was never featured in the reporting, instead a lot of emphasis on the economic cooperation with Israel, who will soon open a fully-fledged embassy in Tanzania instead of being accredited from Nairobi. It is unlikely that Tanzania will rush to open an embassy in Tell Aviv any time soon, but for the first time it accredited its Ambassador in Cairo, Egypt to represent the country in Israel. The relationship is thriving and over 6,000 Israeli tourists are expected to visit Tanzania this year through weekly “tourism-oriented flights” from Tel Aviv to Kilimanjaro operated by the El Al airline.

Dr. Azaveli Lwaitama of University of Dar es Salaam, wonders about the usefulness of the colorful statements in support of Palestinian cause from countries like Tanzania while at the same time allowing Israel to continue “weaving itself in the economic fabric” of the country. Prof. Azaria Mbughuni of Spelman College in Atlanta, who has extensively researched Tanzania’s contribution in the liberation of Southern Africa, still believes that the issues of justice and human rights remain relevant in Africa’s foreign policy and need to be fully restored. He says that, “the struggle of Palestinians is a struggle for human rights. It is not a struggle for a particular religion, for the Palestinian people belong to different religious creeds; it is not a struggle for race, for the Palestinian people come in different shades; it is a struggle for land, it is a struggle for the basic human principles of freedom, dignity, and the right to self-determination”.

Africa’s Last Colony

Earlier this year I flew to the Algerian military town of Tindouf, as part of a Vice News crew, to help make a documentary and write an article about the struggle for an independent Western Sahara. Tindouf sits outside a network of five camps housing Sahrawi refugees from the war between Morocco and Polisario, the Sahrawi liberation movement fighting for a referendum in the region. The war lasted from 1975 – when Spain, with Franco on his death bed, ceded one of Africa’s last colonies, the Spanish Sahara, to Morocco and Mauritania – to 1991, when the UN brokered a cease fire, confidently and erroneously predicting that they would bring about a referendum within six months.

Twenty-three years later, the Sahrawis are still waiting for that referendum and the UN doesn’t even monitor human rights abuses in occupied Western Sahara. In fact, Spain’s ceding of the territory is not recognised by international law, making Western Sahara “the only non-self-governing territory on the African continent still awaiting the completion of its process of decolonization.” With Western Sahara, it’s easy to get bogged down in international legalese. On the ground, the life lived by the 100,000 or so refugees is one of desert exile, a limbo that prevents them from either putting down roots where they are or returning to their land, in which many of their fellow Sahrawis suffer under Moroccan rule.

The camps are run on aid. There are few jobs and fewer education programmes. People worry that if they spend too much time making their temporary home nice, it will become their permanent home. Depression is common in a place caught between a past defined by betrayal and a future that seems to promise only stasis. On an afternoon at the hospital for victims of the seven million landmines littering the desert, the air hung thick with the heat as we spoke to a man who had spent the past thirty years in the same bed, his legs destroyed. As I sat in a patch of shade in the courtyard, it was easy to see his existence as a metaphor for the whole situation.

From the refugee camps, we headed into the wide, barely inhabited stretch of desert given back to the Sahrawis by Mauritania in the late 1970s. We were joined, in our 20-year-old Land Cruiser, by a Polisario commander and six of his fighters. In an area increasingly used by Jihadist groups to smuggle drugs, the Polisario tell us they remain in charge, even guarding the UN Mission for a Referendum in Western Sahara’s (MINURSO) desert base, which blinks multi-coloured in the night like an oil rig, a testament to human impotence. Warming his hands in front of a fire, the commander of one of Polisario’s nightly anti-smuggling patrols tells us that they believe Morocco control the drugs trade in the region.

The Kingdom of Morocco calls Polisario terrorists. They say Polisario have enslaved the Sahrawi people, keeping them in refugee camps (or “gulags”, as Moroccan spies refer to them) in order to profit from the conflict and the largesse of their main sponsors, Algeria. Polisario has had the same leader since the 1976, members of its high command are said to own large houses in Spain and the military regime in Algeria is using them as part of its proxy war with its hated rival Morocco, but the vast majority of people we spoke to in the camps see no differentiation between Polisario and the Sahrawi cause. Out at their desert bases, surrounded by ancient meteors and fossils, Polisario took us through their network of tunnels and showed us some of their military hardware, much of it dating from the Cold War. One commander showed me an Apartheid-made cannon: in the 1970s and 1980s the Polisario would capture South African-made weaponry from the Moroccans and send it down to their revolutionary brothers in the ANC.

Back at the refugee camps, I think of how Polisario relates to successful African liberation movements like the ANC. I think of those other movements that turned sour once they were realized, of Russia post-1917, ZANU in Zimbabwe and the EPLA in Eritrea, of South Sudan and its troubled birth. No-one could say that an independent Western Sahara, sitting in an unstable region, surrounded by rivals and hated by Morocco, might not suffer a similar fate to those places, but there is no good reason why Western Sahara shouldn’t be granted the same right to decide on its freedom that has been granted in East Timor, Kosovo, South Sudan and, later this summer, Scotland.

Right now, the people of Western Sahara feel betrayed, which could lead them to break the ceasefire. This is one of the reasons the film is called The Sahara’s Forgotten War: the international community has abandoned the Sahrawis. Countries across the world recognise Western Sahara’s right to exist in theory but in practice, they trade with Morocco or, as is the case with the United States, actively support them. The Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara is full of phosphates, fisheries and potentially oil and gas.

The Polisario’s frustration at the failure to bring about a referendum is close to boiling over. They told us repeatedly that they were “ready for war” but they lack the resources and international support to mount a full scale offensive on Morocco. They are more likely to carry out IRA-style bombings in big Moroccan cities like Rabat and Casablanca. In the world’s last major colony, the affects of Europe’s scramble for Africa and Morocco’s imperial delusions are plain to see.

Watch here:

Also read Oscar’s full article here.

July 25, 2014

Once a month Hipsters don’t Dance will bless us with their top 5 World Carnival tunes

Africa is a Country is proud to present a new partnership with London-based DJ crew Hipster’s Don’t Dance. The British DJ duo with Trinidadian and Nigerian origins are doing an amazing job representing the Atlantic music world to the London massive with their regular parties, and reflecting back their London scene to the world with their outstanding blog, DJ mixes, and edits. Taking a cue from the lively West Indian Carnival in London, they are injecting other faces of London’s immigrant cultures into the scene, and cultivating what they call a “World Carnival Sound.” Starting this month, they will be doing a regular round up of their top five World Carnival tunes here on Africa is a Country. Here is their top five for July 2014:

Africa is a Country is proud to present a new partnership with London-based DJ crew Hipster’s Don’t Dance. The British DJ duo with Trinidadian and Nigerian origins are doing an amazing job representing the Atlantic music world to the London massive with their regular parties, and reflecting back their London scene to the world with their outstanding blog, DJ mixes, and edits. Taking a cue from the lively West Indian Carnival in London, they are injecting other faces of London’s immigrant cultures into the scene, and cultivating what they call a “World Carnival Sound.” Starting this month, they will be doing a regular round up of their top five World Carnival tunes here on Africa is a Country. Here is their top five for July 2014:

Moelogo – The Baddest (feat. Giggs)

Currently the biggest song out and it has a sneaky chance to be the song of the summer. By adding Giggs , and his incredible voice, to this track it has given this song an even bigger audience. P.S. congrats to Moelogo on signing his major label deal.

Wizkid – Show You The Money

Wizkid when will you release an LP? There are a ton of us that would really like that to happen. Instead he is chilling in LA with Chris Brown and Ty Dolla $ign, this will be placed alongside his other Wizkid classics like Jaiye Jaiye and Caro.

Edem – Wicked and Bad (feat. 4 x 4)

Some Ghanaian dancehall that instantly connected with a lot of DJ’s, it will be interesting to see this work in the club. This could have a big crossover appeal with dancehall and U.K. club heads.

Dj Hassan – Early Momo (Feat. Patoranking)

Its been a busy month for Patoranking, between this, the Girlie O remix, and his anti-bleaching cover of Loyal he really is setting himself up to be the man of the moment. Having a cut on the incredible Bam Bam Riddim can’t hurt either.

Dr Sid – Baby Tornado (feat. Alexandra Burke)

Continuing the theme of odd Afropop collaborators (Idris Elba, Diana King, Olivia….) this one works really well. The video is glossy enough to make it on to UK music channels as well, which is probably the best way into everyone’s homes these days.

July 24, 2014

5 Questions for a Filmmaker … Akin Omotoso

Award-winning South African/Nigerian filmmaker Akin Omotoso is the director of the feature films “Man on Ground” and “God Is African“, the documentaries “Wole Soyinka – Child of the Forest,” “Gathering the Scattered Cousins” and the short “Jesus and the Giant” among other films and TV-productions. Omotoso is also an actor, with roles in Andrew Nicol’s Lord of War alongside Nicolas Cage, as Rwandan President Paul Kagame in “Shake Hands with the Devil” by Roger Spottiswoode, and in the South African TV-series “Generations” on his CV.

What is your first film memory?

I have a couple of film memories from between the age of 4 to 6, mainly because video had just come out and my parents were watching a lot of films that drifted in and out of my consciousness. My first memory is of , but I couldn’t tell you which film. It was probably a combination of his films but Poitier as a first film memory is not a bad one to have.

Why did you decide to become a filmmaker?

I decided to become a filmmaker because I love telling stories. I always loved telling stories and always loved stories. I wanted to be a novelist at first, but at drama school that notion turned into becoming a director.

Which already made film do you wish you had made?

Lumumba directed by . The final image in that film is still among the best closing images I have seen, and the opening image of my latest film Man On Ground is a homage to it.

Name one of the films on your top-5 list and the reason why it is there.

Daughters of the Dust by . It was the first film that I saw that had a non-linear narrative. At the time I didn’t understand what I was watching other than it was very confusing but intriguing at the same time. When I watched it again a second time I was blown away. It’s a beautiful film. The way the story is told, the way the African oral tradition is woven into cinematic realisation, the gorgeous cinematography, the music and the performances. A true visual feast.

Which question should I have asked?

People always ask me “Do you think African Cinema has arrived?” I always reply “It never left.”

Photo Credit: Victor Dlamini.

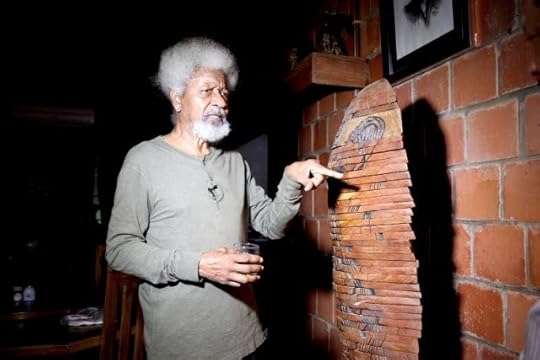

Walking With Wole Soyinka

Several times, I have met Professor Wole Soyinka without actually meeting him. It was either in a crowded reading room in Washington D.C. or at some event in Nigeria. As a photographer not as a writer, I really wanted to meet the man away from the usual crowd that surrounds him all the time. I wanted to do a proper portrait of the man and the legendary white Afro. With his hectic schedule, one couldn’t really tell where he would be at any particular time or how possible it was to even be alone with one of the world’s busiest and famous men of letters.Earlier this month, as events to mark his 80th birthday swirled around towns in Nigeria and beyond, I begged my friend Lola Shoneyin, the novelist and Soyinka’s daughter-in-law, to help me gain access to him. She agreed to try, not promising anything because Kongi, (as he is called by many) had a hectic schedule and wouldn’t really have time to be photographed.

However, I got lucky. Lola called me at about 10pm one night to say she had found an opportunity for me to photograph him. There was a short documentary she and her husband were making of Soyinka to mark his birthday. I would have to rise early the next morning for the two hours drive from my base in Lagos to Soyinka’s private country house in the outskirt of Abeokuta.

I was elated. I’d finally get to photograph him in his lair. I had heard all kinds of tales about this famed house he built in the middle of the forest. Getting there, we needed a guide because though Lola had been to her father-in-law’s house on numerous occasions, she still couldn’t navigate her way there alone because of the convolutedness of the location in the forest.

The first shocker as we got close to his long path leading to the forest read “TRESPASSING VEHICLES WILL BE SHOT AND EATEN.” I figured then that I had to expect the unexpected and also hoped Lola had made an appointment. A man who promises to eat vehicles could do worse to an uninvited photographer. The red-brick house, which nestled atop a hill with a tiny river flowing below and giant trees towering above it, was surreal. For the first few minutes, I couldn’t take pictures. I just marveled at the serenity of the natural habitat. Coming from the craziness of a mega city like Lagos to this quiet green environment was not something I wanted to squander. I took in the clean air and stared at the flowers while Lola went in to tell Prof that he had guests.

I have to navigate carefully in this man’s domain, I told myself. There were more warning signs. If I had doubts about his seriousness when I arrived, I dispelled these when he later brought out his double-barreled hunting rifle while we were interviewing and photographing him. He had no qualms bearing arms, as a famed hunter.

The six hours I spent in Soyinka’s presence flew by like a second. As an artist and a writer, I felt at home amidst his varied art collection, of contemporary and ancient works. He had more sculptures than paintings and it was obvious his preference was three dimensional works of art. Books sprout from ground and walls and bookshelves. I listened intently to the Nobel Laureate’s wild tales and conquests.

Perhaps what was most intriguing to me was his elaborate sense of humor and how he could switch from one extremely serious world affair, like the yet to be rescued kidnapped Chibok school girls in the northern part of Nigeria, to the fact that a man should never run out of wine in his house.

We took a tour of the house and all the hidden reading rooms (there were reading spaces everywhere) and a special prayer room for Christians, Muslims and traditionalists – to Soyinka, there is room for all religions to co-exist. The house on the hill had everything, including an amphitheater for drama rehearsals and performances. There was a shooting range that provided a bird’s eye view of a section of the path that led to the house.

When it was time to visit his reading spot in the middle of the forest, the heavens opened with loud thunder and lightning which had Soyinka, a man who has great regard for Ogun, the god of thunder and iron, and had written so much about it, bust into chanting and incantation. We waited for the rain to subside before going out. We walked along the edge of the forest, watched the river flow gently across our path. With fresh raindrops on the leaves, the forest took on an ominous look.

Prof. Soyinka’s white hair against the dense and dark green of his environment was pleasing to capture. His steps were smart and sure, not betraying his age and decades of struggle against the vilest rulers Nigeria has had. It is not every day one gets to tread the same path as a living legend, so I listened to him with every part of my body.

In a nicely nurtured section of a cultivated garden with lush green grass and blooming flowers, the man stopped and pointed to a serene section, “That is the cactus spot. At some point in life a man has to think of mortality.” I blinked and clicked at the direction he’d pointed. That cactus spot, I hope and pray, would have to wait many more years for its lone occupant, because the man I walked with on that raining day is a rare strong breed.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers