Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 387

October 13, 2014

Africa is a Radio: Episode 6

(photo via NBC news)

Africa is a Radio episode 6 opens up with a transnational blend, combining remixes of Dotorado Pro’s “African Scream” with its sample source: DJ Sbu & Zahara’s “Lengoma.” From there we travel around the world -from Ferguson to Havana to Monrovia- touching on the sonic imprints of the contemporary news cycle. We end on a lighter, danceable note.

Israel’s arms exports to African countries has more than doubled

Despite an overall drastic decline in Israeli arms exports, trade with Africa had reached a four-year record, Haaretz reported on Tuesday.

Interestingly, African countries spent $223 million on Israeli arms in 2013 compared to $107 million in 2012.

The report that was given to Haaretz by the Israeli Defence Ministry doesn’t detail specific countries so there is no official comprehensive information on which country imported how much and what. Despite past demands and petitions Israel refuses to reveal the full list of the countries it sells arms to. As Haaretz reported in January 2014, when ordered by an Israeli court, Israel’s Defence Ministry would only reveal that it had sold arms in 2011-12 to the United States, Spain, Kenya, Britain and South Korea, “but its other customers can’t be named.” As Haaretz pointed out at the time, this was “like a bad joke. First, the ministry itself boasts of the great achievements of Israel’s defense industry and the billions of dollars of business it does worldwide. Second, every international defense journal or website reports at length on the deals of Israel’s defense companies.” In addition, a 2013 British government report was very detailed about Israel’s customer list:

The British report, covering the years 2008-12, listed India, Singapore, Turkey, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan, Sweden, Portugal, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Colombia, Holland, Italy, Germany, Spain, Thailand, Macedonia, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Switzerland, Ecuador, Mexico, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Equatorial Guinea, Poland, Argentina and Egypt as Israeli customers. Even countries that have no official relations with Israel appeared on the list: Pakistan, Algeria, the United Arab Emirates and Morocco. The report also said Britain refused to approve components for products destined for Russia, Sri Lanka, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. In total, that’s 41 countries, and there are others not listed in the British report.

In June, Israel’s foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman toured West and East Africa (that’s him in the photo above in Cote d’Ivoire after being crowned honorary chief), accompanied by 50 executives. The delegation visited Ivory Coast, Ghana, Ethiopia, Ruanda and Kenya. Among the delegates were representatives of Israel Aerospace Industries, Israel Military Industries, and the defence electronics firm Elbit Systems, Israel’s leading defence contractor, which provides arms and services to the IDF in hundreds of millions of dollars.

In April 2013 it was announced that Elbit had won a $40 million contract to provide an anonymous African country with “intelligence analysis and cyber defence.”

Why I am Afraid of the African Disease of Ebola

Wherever I turn, there is Ebola. In the newspapers and magazines, on television and radio, and across the ubiquitous social media. Ebola. I sweat, shake, and cringe in mortal fear. Such an ugly word, fearsome in its primal sound, so African, so dark, so black. Since Africa is one country, beware of going to Africa, the media screams. Never mind those who occasionally mention the disease is currently confined to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, three out of Africa’s 54 countries. But what do they know about world geography, Africa is Africa. That’s the problem with political correctness, denial of inconvenient truths. This is an African disease. It afflicts Africa, that benighted land of biblical agonies, of inexplicable scourges, of unimaginable suffering, of epidemics and pandemics, of AIDS.

I am afraid of Ebola because I am an African. I am not one of the nearly 1.1 billion Africans actually living on the continent. What difference does it make that all of western and eastern Europe, China, India, and the United States would fit into Africa; it is one sorry place home to all those hapless people living in trepidation of Ebola. I am part of Africa’s large global diaspora numbering in the tens of millions. But I remain an African, so I am scared of my susceptibility to the disease that is so African. I live in the United States, and I am terrified because, as of today, months after the panic started Ebola has already killed one person, an African who had travelled to Africa, and infected one health care worker.

I wonder how many people have since died of other diseases—heart disease, malignant cancers, lung disease, brain disease, accidents or unintentional injuries, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide, the ten leading causes of death in the United States, responsible for nearly 1.86 million deaths in 2011, three-quarters of all deaths in the country. Where is the panic on all these deaths, some of which were surely preventable and premature. But that is beside the point. These are normal deaths. Ebola is terrifying in its monstrosity. It is a disease out of Africa.

I am afraid of Ebola because I, too, come from Africa. I watch the gory images of deaths from Ebola in Africa. I listen to the pundits pontificating about the millions it will kill in Africa, the need to close US borders from Africa. I shudder at seeing President Obama whose father came from Africa (or is it Kenya) being called President Ebola. I am stunned when a student refuses to go on a study abroad trip to Spain because it is close to Africa. Hasn’t one Ebola case already been diagnosed there? I am speechless when well meaning colleagues wonder why I’m going to Africa; they never hear the names of the actual countries I am going to.

I am afraid of Ebola because it is robbing me of my African authenticity when I fail to give special insights into the nature of the disease from inquiring colleagues or the media. About the culinary delights of eating monkey meat that apparently sparked Ebola and the strange primeval customs that helped spread it like wildfire. The fact that I am not a medical doctor, or from the three affected countries doesn’t matter. I am an African. Or have I become too Americanized to understand my African disease heritage? Maybe I am not Americanized enough to speak authoritatively about things I know little about, not even when it comes to that simple place with a single story called Africa.

I am afraid of Ebola for bringing back to the center stage the Afro-pessimists with their perennial death wishes for the continent. In recent years they had lost some traction to the narratives of a ‘rising’ Africa. I am afraid of Ebola because it has quarantined me in the denigrated Africa of the western imagination, in the diseased blackness of my body. Ebola has robbed the American public of Africa’s multiple stories, of the continent’s splendid diversities, complexities, contradictions, and contemporary transformations. Ebola is indeed a deadly panic. It threatens civilization as we know it.

Or are my fears about Ebola misplaced? Is it about something else deep in the western psyche I can’t understand, perhaps going back the Black Death of the 14th century that decimated nearly one-third of Europe, the influenza pandemic of 1918 that killed tens of millions of people, or the genocide of native peoples in the Americas brought about by European diseases? But questions offer little solace in the avalanche of grim stories about the African plague of the year, Ebola. As someone who earns a living as an educator, I am afraid of Ebola because it is an enemy of critical and balanced thinking about Africa, about disease, about our common humanity.

October 8, 2014

What’s the matter with … Stellenbosch University

One afternoon, during my final year of high school, I first found myself at Stellenbosch University (also known as University of Stellenbosch) on a tour of potential universities in the Western Cape, South Africa’s south-western province. Walking around the various buildings on campus and after a quick stopover in the Neelsie, the university’s mall, I hesitated at the thought of studying there–besides, they didn’t offer what I thought I wanted to do for the rest of my life at the time. So I spent my undergraduate years at the University of Cape Town instead. However, a decade-and-a-bit and some career adjustments later, I am back at SU as a Masters student in the Visual Art department.

In line with the typical Apartheid urban planning practices of many South African towns and cities, Stellenbosch consists of a town center, reserved for “white” people during Apartheid by the Group Areas Act (1950) surrounded by spatially disconnected and racially segregated suburbs and townships. In Stellenbosch, the Group Areas Act was implemented through forced removals in thriving neighborhoods like Die Vlakte (English: The Flats) in the center of town where “black” and “coloured” people lived. The land in Die Vlakte was subsequently acquired by SU after the communities who lived there were evicted and displaced to Kayamandi, Cloetesville and Idas Valley on the town’s margins.

Legacies of colonialism and apartheid are etched into social dynamics of the town in the way its inhabitants occupy public space – real and imagined boundaries are still constructed according to race and class. Spending a significant amount of time there has reminded me that the architecture of a place, both in the physical and social sense, is always deeply embedded in relationships of power.

The ‘dop’ (tot) system, where farm laborers were paid in alcohol in return for their labor led to generational alcoholism and left visible marks on the town’s psyche. Stellenbosch could be viewed as a microcosm of contemporary power relationships among race groups in South Africa – a wealthy “white” minority with access to cultural capital, a “black” elite and growing yet small middle class and disenfranchised poor “black” majority. In a discussion on poverty and inequality in Stellenbosch, the sociologist, Joachim Ewert suggests that between 1996 and 2009 (roughly coinciding with the first decade and a half of of democratic rule) poverty in Stellenbosch increased within all race groups, except the “white” population, and that poverty in Stellenbosch may be greater when compared to other towns of similar size.

In the ten years since my first visit, the university seems to have made some transformative strides in terms of race representation on the surface. That said, 2013 enrollment statistics show that “white” students make up just over 65% of the student population in a town where the overall “white” population is 18,5%. University projects like the HOPE project, an initiative by the late University Vice-Chancellor, Russel Botman, attempts to address issues of transformation at SU and has identified several core focus areas intended to facilitate institutional redress.

However, recent events in Stellenbosch show that there is room for robust dialogue around race and transformation at the university. These include, most notably: the university’s failure to act against two white students photographed in blackface at a party in September. Then there’s the eugenics kit belonging to a SU scientist close to Adolf Hitler and discovered by researchers in the university’s Anthropology department in 2013 (the university spun it as the basis for a new “innovative” project about the find). Finally, there’s the death of Russell Botman, the university’s first black president, in 2014.

Professor Jonathan Jansen, Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Free State and one of a new generation of black university presidents, among others have hinted at the difficulties and pressures surrounding Botman’s tenure (which may have led to his death) and has publicly called on those who contributed to these pressures for “introspection and acknowledgement of their contribution to the immense difficulties the rector had to absorb as he tried to transform this rock-solid cultural monolith.”

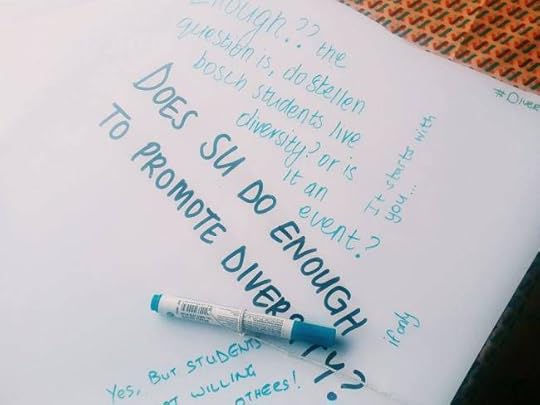

It’s with that background that recently, from 29 September to 3 October, the university held its annual “Diversity week” celebrations, a week-long event organized by SU’s Centre for Inclusivity with the intention to “reflect the University’s view that a variety of people and ideas is an asset for a 21st-century higher-education institution”. The program included a lineup of local comedians and celebrities and a series of discussions called “Critical Hour” on various topics affecting the university, like “Women in Leadership – Must Have or Nice to have?”

The event was opened with a flag bearing ceremony supposedly representing multicultural, Pan-African unity and inclusivity. This was followed by Vicky Sampson’s opening performances of “African Dream” and a cover of Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston’s “When you believe”– a confusing choice for the mostly millennial audience. The event logo and slogan “Glocal is Lekker” (Glocal is Cool) seems to suggest that by embracing a global outlook, the university is aspiring to position itself as a “world-class” tertiary institution and cultivate perceptions of itself as multi-cultural and progressive. (This seems to be a strategy of most South African universities; unfortunately, becoming “world class” often excludes coming to terms with racial and class inequalities inherited from Apartheid)

Browsing through Diversity Week’s twitter feed, and confronted with video-tweets reminiscent of post-1994 Mandela-era rainbowism, I wondered aloud whether university-sanctioned efforts at celebrating “diversity” are premature in place where non-Afrikaans speaking students are still excluded through language (While it is the official language policy of the university to have a dual-lingual approach to tuition i.e. Afrikaans and English, Afrikaans is often the preferred language of lecturers in class) or subjected to forms of institutional and physical violence. For example, stories of incidents involving violent racist insults are commonplace against black students. The university administration proves slow to react. Then there’s the commemorative bronze plaque to H.F Verwoerd, one of the founders of Apartheid and prime minister of South Africa from 1958 to 1966 which adorns the foyer of the Accounting and Statistics building on SU’s main campus.

Although advertised as somewhat subversive of the prevailing ethos on campus, there was nothing transgressive about “Diversity Week” and many of the events I went to were poorly attended. It seemed like little more than a week-long marketing opportunity for the university and a diversion from the real challenges facing the institution. A friend remarked that there were proportionately more photographers to students at the opening ceremony looking for opportunities to capture the “diversity” of the institution. To cultivate a sense of gees or institutional spirit among students seems very important to the culture of this University. Historically, this institutional spirit played an important part in cultivating Afrikaner nationalist identity in building institutions like the Broederbond (the secretive organization which controlled the National Party) and affirmed Stellenbosch’s position as the cultural seat of Afrikaner Nationalism for much of the 20th century.

Given the context of the socially engineered polarization of the town, how can we begin to facilitate a spirit of inclusivity? The Stellenbosch literary Project (SLiP) supported by SU’s English department is a student-led initiative trying to negotiate these challenges in addressing topical issues of inclusivity, inequality and race in Stellenbosch through poetry.

A regular at their InZync poetry event at AmaZink, a bar/restaurant in Kayamandi and one of the few social settings I feel comfortable in in town, I was surprised that they weren’t included on the “Diversity Week” bill. (AmaZink, ironically, was also the setting for a party where two white male students dressed up in blackface as the Williams sisters recently.)

Pieter Odendaal, one of the founders and project manager of SLiP says the idea behind the project was to create an inclusive space where poets performing different styles of poetry, from paper poets to spaza rap could get together to meet and perform their work. SLiP has 3 main projects: InZync Poetry sessions, The INKcredibles—a weekly youth poetry workshop—and an online literary blog, slipnet.co.za.

InZync sessions happen monthly and probably attract the most diverse audience in Stellenbosch. Each session is an exhilarating mix of regular student acts with visiting poets like Cape Town poet/musician Jitsvinger and young poets from the INKcredibles poetry workshops. It has become a space where participants can become entangled in one another’s narratives and perspectives, through addressing the big questions relevant to our time and place like identity, transformation, economic freedom and also the shared human experiences that connect us regardless of race or socio-economic background.

It was important for SLiP to situate the project in Kayamandi, as opposed to a space like the university auditorium to connect students at SU to the wider Stellenbosch community. Crossing boundaries remains a core value of the project. Events are free, which allow anyone to enter the poetry session at AmaZink and shuttles transport students from SU to Kayamandi and vice versa when sessions are held at the university or at Cafe Art in town. Adrian VanWyk, student, poet and Events manager for SLiP adds that while they have been successful in bringing students to Kayamandi, they have been less successful in attracting people from neighbouring Cloetesville. “Black” and “coloured” communities of Stellenbosch remain socially polarized and physically divided by a road – another Apartheid hangover, certainly not unique to Stellenbosch, but hyper visible in a town of this size.

SLiP fulfills an important role in building a spirit of inclusion in a context where “black” students often talk about feeling unwelcome and where they are often excluded outright from entering the town’s bars and clubs. I question whether “Diversity Week” in its current neatly-branded form is really addressing and challenging issues of race, homophobia and sexism at this institution. Transformation is a messy process which may need to involve confrontation and contestation that can’t be limited to a single event for 5 days of the year.

Germany has its own “Sinterklaas Scandal”

The Oktoberfest in Munich may be over, but a curious debate sparked by the annual Bavarian bierfest is lingering like a bad hangover. Is it racist to put up targets portraying black people for fairgoers to shoot at? Yes, in Germany this is treated as a question to be answered with yes or no. This curious “debate” was kicked off by an article in the Munich-based national newspaper, the Süddeutsche Zeitung, on an attraction at this year’s “Wiesn” where visitors could shoot at iron figures portraying a black soldier and a black man in “civilized” clothing with air guns firing lead pellets.

Maximilian Fritz, who runs the stand, clearly knew that something was wrong with his attraction. He expected Wiesn organizers to question him about it, and was surprised when they didn’t. His justification for setting up shop anyway? “It’s about tradition, that’s how it was done in the past!” Oh, and of course he adds another line from the playbook: “I’m definitely not a racist.” Why? Because he removed the iron figure of a man resembling a Jew. In his mind, accusations of racism were “boring and narrow-minded.”

The stand was part of the “Oide Wiesn,” the “old Oktoberfest,” a section of the Wiesn that puts on display artefacts of Oktoberfest’s past. But make no mistake, it’s not a museum. It celebrates the history and tradition of the Oktoberfest, but there is no critical commentary on what is exhibited there. After the Munich newspaper contacted the Wiesn organizers, they did attach a plaque to the stand explaining that shooting at black people was not about racism; it just had to be understood “in the context of the colonial history of the time.” Clearly, the organizers have a high tolerance for contradiction.

The newspaper article triggered what Germans like to refer to as a “shitstorm” on social media. A look into the streams and comment sections is instructive about the level of public debate in Germany. The Süddeutsche Zeitung’s question, “Is this racism or tradition?” prompted many people to comment that it’s both, a “racist tradition.” But many other comments reveal that people think like Mr Fritz, the stand owner. “We have more important problems to discuss” was a usual response—fighting ISIS, for example. Some people even suggested exchanging the black figures with figures of Islamists.

Comments conveyed all the well-worn tropes of reactions to charges of racism. For many, it was a “typically German” debate. Germans overreact, they cause alarm for no reason, and they are too dramatic. Some complained that critics were too quick to “wield the Nazi cudgel,” a term recalling a debate around renowned author Martin Walser’s rightward shift in the 1990s. Many commenters were concerned that soon “it won’t even be allowed to shoot at animals and flowers, lest we upset animals rights activists.” Finally, the whole thing couldn’t be racist because some targets were white figures and players don’t actually shoot at the figures directly but at moving clay pipes attached to the figures.

The level of ignorance these comments convey is alarming. Commentators did not recognize that the other figures probably portray outcasts and other marginalized people of the time. And many people cited in their comments their happy childhood memories of singing the song “10 kleine Negerlein” (10 little N***), playing with their N***-puppet, and eating N***-kisses, a type of chocolate-glazed sweets. In those times, “no one thought this was racist,” and that’s why apparently it should be OK today. Some thought placing things in historical perspective made things worse. If the explanatory plaque hadn’t been attached, their reasoning goes, nobody would have made a connection with race discrimination.

The most disturbing comments were those characterizing people who raised concerns about racism as “fascists of political correctness,” “sharia public order officers,” leftist idiots who always complain, smartasses, and “Gutmenschen” (do-gooders)—a term linked to right-wing populism that was declared the second-worst term of 2011 (“Unwort des Jahres 2011″). Many commentators felt that those who raised concerns were people who felt the need to distinguish themselves.

At a time when Germans are concerned once more with the “refugee problem” and fears of a rising tide of anti-Semitism, this debate is troubling. As in many other contexts we wrote about, tradition is used as an excuse for racism. People don’t see a problem with the usual justification that it’s not meant to be racism. Hamado Dipama, member of the Panafricanism working group and of Munich’s Council for Foreign Residents, rightly wonders “Why is it so difficult to understand when we Africans say that it’s offensive?”

* Image Credit: Twitter.

5 Questions for a Filmmaker … Moussa Sene Absa

Moussa Sene Absa is a Senegalese filmmaker, artist and songwriter.

What is your first film memory?

It happened during the school holidays the year I turned ten in 1968. As a reward for my good grades my uncle took me to the cinema to watch <The Lion from Saint Marc. At one point when a lion looks straight into the camera I was terrified and tried to run away, but my uncle grabbed me and said “It’s just a film.” The scene haunted me for days.

Why did you decide to become a filmmaker?

I fell in love with movies as a teenager, but before that, when I was ten, I used to make Chinese shadow films at our house in Tableau Ferraille. Kids would pay me to tell them stories, which I had read in comic books or seen on film, like ‘Blek’ and ‘Zembla.’ Story telling is my way to make the world a better place, to dream and allow others to do the same. I’m a Griot and a storyteller, who grew up in a family of musicians and singers. I started in theatre before turning to film. I was fascinated by both art forms and I’ve always considered the stage to be the best storytelling platform. Film is the perfect tool to tap into other realities in order to make sense of the world, and to portray people and their stories. I became a filmmaker to tell both great and decadent stories, and to make people cry and laugh out of fear and joy.

Which film do you wish you had made?

There are many films that made a huge impression on me and that I wish I had made, like Once upon a time in America, Rome, open City, Breathless, Hyenas, The little girl who sold the sun and In the mood for love. But if I had indeed made them they would be different as they would have reflected my personality and culture in terms of music, costumes, casting etc.

Name one of the films on your top-5 list and the reason why it is there.

In its simplicity and the way the story is told, The little girl who sold the sun is the most accomplished film, which talks about life and the future. It’s such a pure and humanist story, and without ever becoming sentimental, it portrays the protagonist – a young girl – as a hero.

Ask yourself any question you think I should have asked and answer it.

‘Where is African cinema heading, and what are you working on now?’ Africans have made films for half a century, and the continent has produced many great filmmakers, who made films rooted in Africa while also reflecting a universal vision, However, during the last couple years, our film language has become increasingly uniform, and with a structure that originates from the West: “Introduction and development followed by conclusion”. Africans usually begin with the end, saying, “He is dead” and then trace the life of the dead person and the people concerned. This storytelling structure is hardly applied on our films.

I’m hoping that our filmmakers embark on a search for our identity and our cultures. You could easily think that some Africans films were made by British, Germans or Americans, with a gaze that is truly problematic.

At the moment I’m working on a project called Sangomaar, which explores how we adapt to our turbulent world. According to Senegalese tradition, Sangomaar is where the sea meets the river and where the Gods gather to discuss mankind and suggest solutions to our problems, as well as scolding or rewarding us. It’s the place where our destinies are formed.

‘Sangomaar’ is the second film in a trilogy about black people that starts with my film ‘Yoolé’ (The Sacrifice). I’m applying the principles of Kurukan Fuga (the ancient Malian constitution) to judge whether we as human beings are moving forward or backwards.

I ask questions about where we come from, how we are living our lives, and alternative ways of living and thinking. I also explore the painful moments of our rich and poor continent. Africa is indeed a place of contrast and paradoxes.

* The ‘5 Questions for a Filmmaker …’ series is archived here.

October 7, 2014

Let’s talk about ethnicity and nationalism in Ethiopia

So much of the discord and paralysis in the pro-rights movement in Ethiopia and the Diaspora comes down to one factor: ethnicity. Politics related to Ethiopia has become so heavily “ethnicized” that we have a difficult time distinguishing between ideology and identity. Conversations about change cease to center on shared concern (like justice, human rights and democracy) and turn to disputes over ethnicity. While recognizing that we shouldn’t sweep these issues under the rug, it is clear that currently no one benefits more from this fragmentation than those who are interested in maintaining the status quo—chiefly, the ruling regime which has inflicted injustice and repression on people of all ethnic groups, including its own.

Increasingly elites in Ethiopia are using ethnicity as a basis for political organization, infusing linguistic and cultural differences and competing historical narratives with new political meaning. In recent years, there has been a rise of ethnic consciousness and ethno-nationalism, most notably amongst Oromos—the nation’s largest ethnic group (estimated at over 25 million people within Ethiopia, larger than most African states), which has historically been disproportionately underrepresented in national politics. Under the existing Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government, power has been wielded predominately by elites from the minority Tigrayan ethnic group, while in the past—with the noted exception of the Derg regime during the 1970s and 1980s—it shifted mainly between Amhara and Tigrayan monarchs.

Despite having introduced ethnic federalism, a system of decentralization that, in theory, distributes power and resources to regional states based on ethnic majorities, the EPRDF government views ethnic nationalism of any sort as a threat to its centralized rule. In fact, the intention of this new system was never to share power but to maintain political dominance. According to a 1993 EPRDF manifesto:

The interests of the majority of the population would be fulfilled only through our revolutionary democratic lines. So the objective condition requires the establishment and continuity of our hegemony”. The way that the EPRDF seeks to establish this hegemony is by institutionalizing ethnic divisions: “The mission of these nationally-based organizations is, on the one hand, to disseminate in various languages the same revolutionary democratic substance, to translate this substance into practice by adapting it to local conditions (history culture, character, etc.).

Though the EPRDF envisioned ethnic federalism as a means of maintaining control over an ethnically-diverse state, when groups assert their autonomy, the government’s response to ethnic mobilization around political grievances—similar to its response to any type of political opposition—has been harsh and swift. For instance, earlier this year, Oromo students took to the streets in the town of Ambo to protest the government’s plan to expand the administrative boundaries of the federal capital, Addis Ababa, into parts of the Oromia Regional State. According to the government, 11 students died in Ambo when they encountered police who were deployed to quell the protests, although eyewitnesses say that dozens of students were killed. As protests spread to other towns, hundreds more students were arrested. Although human rights groups and activists rightfully condemned the brutal massacre and crackdown, there was scant national or international coverage of these deaths or arrests—not surprising given the state’s control of the media.

Within the vocal Oromo Diaspora community, the state violence in response to the student protests has been described as more than an attempt by a repressive regime to crush opposition to government policy. Instead, it is understood as part of a systematic and long-standing history of oppression against Oromo people by the Ethiopian State. The expansion of Addis Ababa into 1.1 million hectares of the Oromia Region demonstrates blatant disregard to the authority of the Oromia Regional Government and is viewed as legally and morally indefensible. Mohammed Ademo explains: “For the Oromo, as in the past, the seceding of surrounding towns to Addis means a loss of their language and culture once more, even if today’s driving forces of urbanization differ from the 19th century imperialist expansion.”

Conversely, for some non-Oromos, the fact that the protestors were advocating for upholding Oromos’ regional autonomy over federal planning priorities is viewed as “anti-Ethiopian” and an impediment for national development. This idea is aided by the government’s response that the protesting students were “anti-peace forces.” While seemingly laughable, re-focusing the debate on whether Oromo nationalism is “threatening” Ethiopian stability has quietly shifted attention away from the government’s egregious actions against peaceful protestors.

Beneath the recent dispute over urban expansion, federalism and the government’s common use of excessive force against protesters is a boiling debate about identity, history and state legitimacy in Ethiopia. One typically encounters two competing narratives on the question of Oromo national identity. The first is a narrative of imperialist expansion, in which Oromos have been marginalized politically and economically for centuries and continue to be oppressed under the current regime. In this version, what is promoted as Ethiopian culture—food, music, language, and traditions—is largely Amhara and Tigrayan and does not reflect the unique contributions of Oromo people.

The second is the multi-ethnic nation narrative, where (similar to South Africa) Ethiopia is construed as a multi-ethnic nation that accommodates and embraces its cultural diversity. Under this framing, all ethnic groups have equal standing in politics, and those who complain of marginalization are portrayed as being “anti-Ethiopian” – promoting their own self-interest above what’s best for all. Repression, injustice and inequality in Ethiopia under this narrative are not issues related to ethnicity but rather to class and political affiliation.

Admittedly this is an oversimplification, but that these two narratives dominate many conversations in Ethiopia today is revealing in demonstrating how a lack of open debate and dialogue begins to dangerously cloud the truth. Ethiopians should really be discussing how to respond to a government that feels the need to kill peaceful student protestors. The less we converse—and the more we compete to have our narrative told over others—the more dangerous our silences become.

‘Niçoise with sweet potatoes’

What is more surprising than a mix of traditional Congolese music and European baroque music? What is more powerful than someone who makes another culture’s codes his own? “Coup Fatal” (currently on tour in Italy and Germany) is a collaboration between the Congolese baroque singer, Serge Kakudji, the Belgian choreographer, Alain Platel and the Belgian jazz musician, Fabrizio Cassol. A bit tongue-in-cheek, the makers explain that they have made something like a salad; mixing a bit of Europe and a bit of Africa. This “niçoise with sweet potatoes” brings thirteen musicians and dancers from Kinshasa plus the counter-tenor to the scene, under the musical supervision of Rodriguez Vangama. Here’s the trailer:

I saw the show in Brussels. After the show, try to explain to a friend what you saw and I bet words will fall short to describe this inexplicable experience. This performance appeals directly to the senses and the emotions invoked. The absence of a clear story, logic or structure forces you to be guided by your instincts.

When I asked Serge Kakudji what Coup Fatal is about, he simply answered: “Coup Fatal is like the Congo River, you expect a wave to arrive but you never know when and how it will manifest itself.” I would even go as far as saying this show intelligently represents several facets of Congolese daily life: a day-by-day-existence enveloping the absence of thoughts about “tomorrow,” poverty, political corruption but above all, a determination to overcome hardship. According to Alain Platel it is remarkable how much that determination lacks in Western society.

Alain Platel smartly let the dancers’ bodies express in their own individuality the contradictory phenomena we can find in Congo; for instance, poverty opposed to the dandy movement better known as “sapologie.” This paradox is even present in the setting. In fact, the sculptor, Freddy Tsimba, offered an incredibly beautiful curtain made of war bullets for the show.

I think the paradox is everywhere in “Coup Fatal.” Perhaps, the main lesson here is that differences can be harmonious and allow people to come together despite their background and roots.

Angola’s Forgotten Massacre

In her famous tract on literature and trauma, Cathy Caruth writes: “If Freud turns to literature to describe traumatic experience, it is because literature, like psychoanalysis, is interested in the complex relation between knowing and not knowing…” Lara Pawson’s In the Name of the People: Angola’s Forgotten Massacre (2014) is literary reportage that flirts with memoire. It tells a slice of the complex and violent events on and after the 27th of May, 1977: the date of a supposed coup d’etat in Luanda, Angola. As the coup (or demonstration, depending on who is speaking) was initiated by internal dissenters of the (still ruling) MPLA party in the early years of Angolan independence, it has been scarcely acknowledged within Angola, and absent from discussions outside the country. In the years following the events of vinte-sete de Maio, thousands were purged from the MPLA, including many who were demonstrably innocent of collusion with the opposition, led by Nito Alvez, a former government minister. The numbers killed are only surmised, and the wide disparity of numbers each party claims tells of the darkness that shrouds the vinte-sete: claims are anywhere from four to 2000 to 90,000.

Now, if literature provides a key to traumatic experience, the historical content in Pawson’s book includes overviews of historical writing, witness and victim testimony, confession, and description: both hers and others’. The confessionary model has been used in modern truth and reconciliation hearings, but this book, however, is the struggle of a reporter and a sympathizer to come to terms with what happened in a country far from her home in Britain. As she was paid to witness events in Angola as a war correspondent for the BBC in the 1990s, the events of the country haunt her in an oblique and powerfully confusing way. In fact, one of the many crises that emerge in the course of the narrative is that of the public sphere, especially given the media networks within which Pawson moves. If, as Graça Francisco insists (reprinted in the opening of the book), this is Angola’s history alone, what are the affiliations, strings, attachments, and collusions that allow someone like Lara Pawson to engage? Pawson answers: “Someone has told me a story. Why do I believe it? Will anyone else? I just want to stay very still, to let the heat fill me up, and to know that Maria [a victim of the vinte-sete] is beside me, that we are together, sewn into each other’s skin by an immense effort to revisit the past. Before I met her today, I believed that cultivating the memory was an obligation: now I’m beginning to understand that it’s also an art.”

There are two major crises the book lays out: political and historiographical. Therefore the question that immediately presents itself is whether this book should be considered a contribution to existing (though scarce) literature on the vinte-sete or whether it exists more as an elegy and reverberations of the vinte-sete. Politico’s José Pedro Monteiro points out that the tactic of confession and the subjective textures of memory can also immunize Pawson from the burden of facticity. If these are just stories from particular points of view, what is the point of trying to determine the truth of this set of events?

Perhaps, then the book spells out what historian David William Cohen called “the risks of knowledge.” It has become, in fact, common in Angolan historiography to turn to memory because of the lack archival evidence and the obscurity of official documents: in the vinte-sete case, there are very few documents or official statements outside of the sixty-five page pamphlet published by the MPLA in 1977. And consider the archival reliability of the publication. The pamphlet ends with a whole page block letter quote from the Political Bureau of the MPLA, a purist Leninist sentiment:

We will apply the Democratic Revolutionary Dictatorship to finally finish with saboteurs, with parasites, and with opportunists.

In this quote is the seed of contention, which rages on today, about who were the peasants and proletariat that were to be the beneficiaries of the “new Angola”. If the vinte-sete has a particular valence today, then it is perhaps the ghosts of the MPLA that are emerging as the country moves on from the 2002 ceasefire and manages an economic boom.

But if one of the criticisms of the book is that Pawson blows the vinte-sete out of proportion in relation to the millions who died in the war with UNITA, it is because the war has been the only history told about the MPLA; it is the only one that for the party is verifiably “heroic” and moral. It is in this vein that the issue of numbers of dead becomes important. She asks whether it would be any less horrifying if the number were 2000 instead of 90,000. Of course it would be less of an “event,” still abject, but comparatively insignificant given the overall level of trauma and numbers of dead in the years since the 1961 insurgency against the Portuguese. Counting the dead and determining the official cause and labels has become the political plague of modern war worldwide.

A major contribution of the book is the refusal—poised on an inability—to discuss this event on the level of official history. The most riveting moment for me was when Pawson describes sitting at a beachside café watching while two men might be murdering a man; she’s not sure. I read it several times, attempting to process the same scant amount of information she gives. This sense of alarm and absurdity—sitting comfortably on a beach while feet away someone violently loses their life—discernibly shapes the affect of the book. The vignette is telling of the positionality that so clearly troubles her: she sits comfortably and safely in a space demarcated by money, status, a labyrinth of laws, and international intrigue, while gazing in horror at what happens just on the other side of that boundary. She is a witness.

October 6, 2014

Who profits from the production of blackface?

That time of the year is coming up again and the contested Dutch blackface figure Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) is still with us. Some tried to turn blackface into brownface (only in the Netherlands) while others are still trying to convince us that Black Pete sets a fine example for black people. In any case, anti-blackface protestors have not been silent.

Recently, anti-blackface campaigners have again drawn attention to the economic dimension of blackface. It is quite apparent that the Dutch state and its economy are profiting generously from their annual blackface partay. The Dutch spend more on the Sinterklaas celebration than on any other public holiday – think presents, but also lots of Sinterklaas related stuff from toys, candy, and chocolates to wrapping paper. It comes to no surprise then that campaigners are critically examining who exactly is profiting from the production of blackface.

The idea that blackface is not only produced, but also very much consumed goes back a long while. Blackface has a long trajectory of entertainment. The consumerist notion of blackface has led to a situation in which the use of blackface has become normalized. In the same vein, using caricatures and stereotypes of black people in the design of, for instance, children’s toys is also common practice. The act of consuming blackface has now become a disposable act, unrelated to any political issue and completely emptied out of its historical context. This also, partly, explains the huge outrage (and all the tears) that anti-blackface campaigners are faced with; they are disturbing the natural order of things (blackface). As many have argued before me, the dehumanization of black people has become ingrained in the fabric of our societies.

There have thus been a lot of instances where blackface has been used, in print, in commercials, etcetera. A few years back a franchise of Dunkin’ Donuts in Thailand came under criticism for having woman in blackface promoting a new chocolate flavoured doughnut. Although the Thai officials tried to defend themselves, the company’s US headquarters immediately pulled the add and offered an apology.

There’s little hope that Dutch owned department stores will give up the profits made from dehumanizing black people, but what about Dutch department stores that have international owners? Do they condone the use of blackface? Do they want to promote the use of blackface? Do they want to make their money from blackface? We know that in their respective home countries, for example the UK, there would be a national outrage if any department store had the audacity to put up giant stuffed golliwogs on a rope for entertaining purposes.

Dutch department store group De Bijenkorf (known for the Black Pete’s on a rope spectacle) is internationally owned, more specifically by Selfridges, a chain of high-end department stores in the UK.

To that end, campaigner Eduard Mangal posted the following to the Facebook page of Selfridges:

Mr. Anthony Graham of Wittington Investments, and Mr. Paul Kelly of Selfridges do you support racial offending actions that can hurt your business and ignore court decisions? Do you really support blackface? Talk to your management in the Netherlands and please respond!

He also posted this to the Facebookpage of De Bijenkorf (who deleted the whole topic):

Why does the Bijenkorf not respect the decisions of the [Dutch] court, the Board for the Protection of Human Rights and the UN working group of experts on peoples of African descent, that the blackface character “Zwarte Piet” is a racist caricature, confirming stereotypes? Why does the Bijenkorf [- your store in the Netherlands! - continue to offend people by] decorating their store with blackface characters?

On September 26th, Selfridges responded to Eduard Mangal by basically saying that they are fine with promoting blackface because De Bijenkorf styles their Black Petes differently every year and take the “Dutch Centre for Folk Culture and Immaterial Heritage” into account.

Thank you for your inquiry we have checked with our colleagues in de Bijenkorf and they have informed us that they have responded to this information request on their Facebook page

The response is as follows:

The Piets will again decorate the Atrium in de Bijenkorf, the way they have for decades.

Separate from the societal discussions about the appearance of Piets the appearance at de Bijenkorf are in line with the recommendations of the “Dutch Centre for Folk Culture and Immaterial Heritage”.

Each year the Piets in the deBijenkorf are styled differently in terms of accessories, clothes and hair. So for example the Piets don’t have golden earrings and they have different hair styles, such as straight hair. Matching the current trends.

This year the appearance will evolve in line with the recommendations from the “Dutch Centre for Folk Culture and Immaterial Heritage”.

We thank you for your interest.

Selfridges cannot be taking itself seriously with such an answer.

They as owners profit from promoting and selling blackface and they are not the only ones. Dutch department chain store HEMA is also internationally owned. UK private equity fund Lion Capital LLP owns HEMA, which has branches in Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, France, and now in Spain and in the UK as well. Recently HEMA opened its first UK store in London (without Black Pete products). HEMA had announced that it would take Black Pete related products off the shelves, but later backed out by saying in a public statement that they will be selling these products par usual and will follow the debate closely in case of any important changes in the regulations. However, they did make some changes to the products that are also for sale in other countries. So basically: What is absolutely not racist to us might be racist to others, i.e. the Dutch logic. Eduard Mangal also questioned HEMA owners Lion Capital LLP and still awaits a response.

Campaigning against big companies that have big money might seem impossible, but there have been success stories. A collective of people, including the action group Mad Mothers NL, sent letters to the Sesame Street Workshop Corporation in the US and demanded that Black Pete be scrapped from the Dutch version of the program. Black Pete will now no longer appear on the show or be used for promotional purposes. Another example is Playmobil, who will no longer be selling plastic Black Petes. These actions are important because they demonstrate that international companies are indeed weary of supporting blackface – as they should be – and that protesting does help in some instances.

Although some Dutch people still like to think we’re an isolated little nation– we are not. Stores such as De Bijenkorf and the HEMA perpetuate blackface, and through their international owners contribute to a global economy on blackface. Selfridges, would you have a window display full of fun golliwog products? I think not.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers