Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 270

October 8, 2017

Nobel Prizes and Politics in Kenya

Ngugi Wa’Thiong’o reads from Wizard Of The Crow at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 2008.

Ngugi Wa’Thiong’o reads from Wizard Of The Crow at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 2008.Memories of the past is what makes us evaluate the present, as we plan for tomorrow

Nobody is entitled to a Nobel Prize and many are deserving of the honor. On October 5th though, Kenyans mourned another lost opportunity. Many expected to celebrate their second Nobel Prize winner in the nation’s history. African literary giant Ngugi wa Thiong’o was the odds on favorite for the prize in literature, and would have joined environmental activist Wangari Maathai, the first Kenyan, and African woman to win in 2004.

Ngugi’s hopes were sidelined last year by the controversial pick of Bob Dylan and this week by Kazuo Ishiguro. However, the Nobel buzz around Ngugi points to both his seminal contributions to African literature but also his work to kept the memory of Kenya’s divisive past alive. Comparing the life of Kenya’s perennial Nobel frontrunner to that of the country’s sole Nobel Laureate begs the question, just what do these two luminaries in their respective fields have in common? They were both born under the yoke British colonial rule and forged their careers challenging authoritarianism.

Growing up nearly sixty miles apart during the violence of the Mau Mau rebellion, Kenya’s Nobel Laureate and perennial Nobel martyr were shaped by a colonial war against inequality, and became staunch critics of a political system still grappling with this legacy today. Placed in the context of Kenya’s contemporary politics, where historical injustice and electoral corruption dominates the news cycle, Ngugi’s and Wangari’s contributions to political change and historical memory at home, likely outweigh their Nobel worthy impact on the politics of language and conservation abroad.

Colonialism and Kenya’s Wars of Liberation

Born in 1938 and 1940, Kenya’s future Nobel finalists grew up during the peak of British colonial occupation among the Kikuyu community. The elder Ngugi outside of Limuru and Wangari near Nyeri, were born into rural farming communities bordered by the racially dominated “White Highlands,” and not far from the colonial capital of Nairobi.

Their mission education challenged local forms of identity and politics. Socialized in a system marked by Christian teachings and colonial evangelism, Ngugi and Wangari recall that children who spoke in their native African language were often beaten by school authorities.

Forced to carefully negotiate their identity in an oppressive system, both went by the baptismal names of James and Mary Josephine during their youth. However, they were also members of the growing class of educated elite, the Athomi or “readers” in Gikuyu. On both sides of an increasing divide, the Athomi used their status to challenge and collaborate with colonial authority.

During their formative teenage years, Kenya plunged into a bitter anti-colonial insurgency. Mau Mau as it was pejoratively called, pitted radical “freedom fighters” again colonial loyalists in a war of liberation which was not simple a black vs white affair. Freedom fighters, drawn mainly from the landless Kikuyu poor, attacked white settlers but also fellow Kenyans who worked for the colonial state, labeled as “loyalists” during the war.

From 1952-1956, at least 20,000 Africans were killed and 10,000s more imprisoned and often tortured in squalid conditions. Less than 50 white settlers were killed and the war’s largest single “battle” known as the Lari Massacre occurred just a few miles from Ngugi’s home. While not a single white settler was among the perpetrators or hundreds of casualties at Lari, the divisive local effects of Kenya’s racist colonial hierarchy were evident. Mau Mau was a war of liberation, but also one which reflected the bitter class divides colonial oppression had sparked within Kenyan society.

Ngugi, Wangari and the athomi, were stuck in the middle of this conflict. At times attacked for the symbols of their elite status, the necktie wearing “Tai Tai” as they were sometimes called, often represented a moderate political voice during Kenya’s struggle for independence. As the war ravaged Ngugi’s and Wangari’s home regions, these young athomi were forced to choose sides and their careers challenging elite authoritarian rule reflects the legacy of Kenya’s brutal struggle for independence.

Authoritarianism and Persecution

When Kenya emerged from colonial rule in 1963 it was the moderate athomi who took power and not the landless poor who had risked their lives as front-line “freedom fighters.” Jomo Kenyatta, though imprisoned during Mau Mau, often distanced himself from the movement and dismissed the divisions of the past. At the 1964 national holiday celebrating the independence struggle Kenyatta claimed: “It is the future, my friends, that is living, the past is dead.”

From 1963-2002 Kenya was ruled by just one political party and two authoritarian leaders, Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Arap Moi. As a de facto one party state from 1969-1991, Ngugi was a harsh critic of both Kenyatta and Moi. Political detention and persecution in the late 1970s forced him into exile in 1982.

Wangari was also shaped by the authoritarian Moi regime. When her Green Belt Movement advocated for environmental conservation and sustainable development by planting trees, her efforts clashed with corrupt officials who routinely grabbed public land and exploited it for political gain. Most famously, her public protests to preserve Nairobi’s Uhuru Park and Karura forest from illegal development put her in violent conflict with Moi during Kenya’s “second liberation” from one party rule.

This ongoing struggle to deal with the past still dominates contemporary politics and shaped Ngugi’s and Wangari’s careers. The memories of the divisive violence of Mau Mau and Kenya’s postcolonial struggles are still vividly alive in many communities where the struggle for land and opportunity are not just memories of the past.

Memory, Fiction and Politics

For Ngugi, Mau Mau and the oppressive corruption of the Kenyatta and Moi regimes was a reoccurring theme throughout much of his literary career at home and in exile in the U.S. As he famously advocated for the promotion of African language to “decolonize the mind,” Kenya’s ongoing, internal struggle for liberation continues.

More than fifty years removed from independence, Mau Mau veterans are still struggling to reveal the human right abuses of British rule, even as British foreign minister Boris Johnson continues to bask in a post-Brexit nostalgia for “empire.” And in Kenya, stories of national heroes like Dedan Kimathi are still being uncovered and reclaimed.

As a teacher, Ngugi’s writings provide a rich window into Kenya’s complex past but also a bridge to the present. Next week my introductory African history class will be reading Ngugi’s classic 1965 novel The River Between. Set in the early years of colonial occupation, the novel is about the growing internal divide Christianity and other colonial impositions sparked within African communities.

The protagonist and athomi characters of the The River Between represents a moderate political bridge between two communities polarized by colonial divisions. Through the tragic voice of young people we learn that Muthoni pays with her life for attempting to live as both a circumcised and Christian woman, and the protagonist Waiyaki is rebuked by both communities for his efforts to unite the opposing ridges. With only one minor white character in the novel, it is an important story of the internal divides of colonial Kenya, which has eerie resonance with contemporary politics.

On October 26th, the sons of Kenya’s first President and Vice President will square off to contest the Presidency for a third time. Historical injustices related to unresolved land claims, corruption, political violence and authoritarian rule have loomed large over contemporary electoral politics. With the Kenyan Supreme Court asserting itself as the final arbitrator of bitter electoral disputes, the politics of memory and a violent past continue to dominate Kenyan lives.

As Ngugi argued it in the wake of Kenya’s horrific 2007-2008 post-election violence: “The solution to Kenya’s problems, then, is long term. But ‘the urgency of now’, to use Martin Luther King’s phrase, requires that progressive forces from within and without the warring camps to lean heavily on the leaderships to hearken to the voice of reason and not tear the country apart.”

Ngugi’s elusive Nobel Prize puts a spotlight on the unfinished work of decolonization. His words in 2008 are a firm reminder that the struggles of the past are sometimes dangerously still alive in the present.

October 6, 2017

Is a Chinese education the best shot at success in Africa?

On a recent research trip to Tanzania, I interviewed an undergraduate student of the University of Dar es Salaam. Soon our conversation descended into a general discussion about life and the future. He, unlike me, was unfazed by life after graduation, having set his sights firmly on employment with the most visible partner throughout Tanzania. “The director of the Confucius Institute said he’d recommend me for a Masters scholarship in China because I’ve been interning in the department; I’ve been learning Chinese there for a year so he knows I’m serious.”

I asked him why he had chosen China over postgraduate courses in Europe or the United States, traditionally the route for ambitious African students: “China is reasonable” was his simple answer. He continued, “and the opportunities are everywhere.”

Image via author.

Image via author.“Opportunity” was a rationale that dominated many conversations about China I had had both within the university, and amongst young professionals in offices clustered near Dar’s city centre. It is easy to see why, in Dar at least, China had become synonymous with economic opportunity: it feels as if one cannot walk down a street in the city without passing another Chinese backed construction project, often great monoliths which stretch their concrete limbs across the skyline.

Image via author.

Image via author.China’s growing presence in Tanzania has been replicated in the field of education, with two Confucius Institutes founded in the country since 2013; one in Dar es Salaam, and another in Dodoma, seven hours by car from Dar. CIs are bases from which Chinese language and culture can be promoted in many forms, both within universities by offering elective and BA language courses, and throughout a select number of secondary schools to which CI teachers are sent. Moreover, the growth in Chinese educational investment into Tanzania has been matched with significant increases in the providence of short and long term scholarships for academic study in China.

It is easy to mistake the distinct growth of scholarships offered to African students by China (an estimated 30,000 a year from 2015) as a repeat of policies undertaken by the erstwhile Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War; programs that sought to educate African leaders of the future, and in the process align these students with their ideological leaning. While there are undoubtedly soft power connotations to this growing influence, China’s educational programs in Africa differs by its overt pragmatic motivations: China requires a new generation with Chinese language and cultural knowledge to facilitate the growing political and economic relationship.

Image via author.

Image via author.Pragmatism dictates how many young Tanzanians I spoke to view a Chinese education. Despite voicing unflattering accusations about Chinese workers and Chinese products, a Chinese education was seen as a logical pathway to securing well-paying reliable employment. This is evidenced by Chinese firms employing students directly through the Confucius Institutes for a growing number of available positions in marketing, sales, architecture, quantity surveying, and law. Many more Tanzanians are returning from China after their undergraduate or postgraduate degrees and setting up businesses which directly trade with the Chinese in a number of capacities. The financial benefits of a Chinese education in the private sector are becoming increasingly obvious, shown not just by the institutional growth of Chinese language education, but also through the advertisement of unofficial language classes taught by Chinese immigrants across Dar.

In short, a generation of young Tanzanians are approaching China’s growing investment with a nuanced mindset, simultaneously swayed by the latent benefits of learning Chinese for future career prospects while continually aware of the unsavory implications of Chinese presence. Perhaps it was this pragmatic perspective that my interviewee in the basement of the University of Dar es Salaam was alluding to when he described China as reasonable: an understanding that the demands of Chinese influence are, at least for now, outweighed by the benefits of cooperation.

October 2, 2017

Contemporary affairs–on reading Lindiwe Hani, Pumla Gqola & Redi Tlhabi

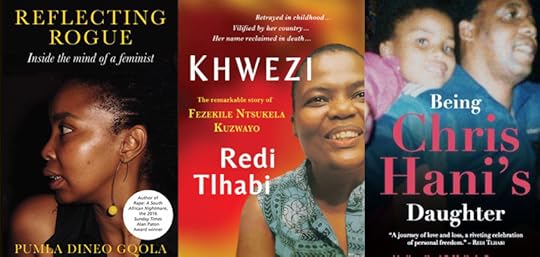

Books by Pumla Gqola, Redi Tlhabi and Lindiwe Hani.

Books by Pumla Gqola, Redi Tlhabi and Lindiwe Hani.Over the past few months I have been in correspondence with a South African intellectual and academic who is old enough to be my father. Our exchanges have been rich and warm. I have long admired him. When I worked up the courage to share with him my excitement about our conversations and told him I appreciated the time he had taken to read my work, and when I said I was especially grateful because of the place he has long held in my mind as someone of true intellectual integrity, he was kind enough to delve into his archives and share a review he once received from one of his own heroes. He told me he remembered his own gratitude for the attention he had received from this man – a writer and thinker of great stature – whom he too had read and admired from a distance for years. It was a touching act, a reminder to a younger writer struggling with her voice and her place in her society that she was not the first to have jitters; a reminder that even the greats doubt themselves at first. In part, the form and candor of the exchange was possible because of the positions we occupy on the spectrum of our careers. He sits well past mid-age; his most productive years (though perhaps not his best) behind him. I am much younger and so for me the future holds a different set of possibilities.

When I was younger everyone whose intellect I admired was much older than I was. I read people who were published, which 20 years ago when I was reading voraciously as a student, meant they were established. The timeframe between thinking and writing and then between writing and getting published, was much longer then. The spaces were fewer and the options narrower and this meant that to have your name in print – in an era when there literally no such thing as online – you were very talented and connected and lucky.

Writers like Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag and Ursula Le Guin in the United States; Sindiwe Magona and Lindiwe Mabuza who were South African; Ayi Kwei Armah in Ghana and Chinua Achebe who seemed to own the world – they were all much older than me and partly as a function of their age they felt impossibly wiser than I might hope to ever be.

I grew up with pictures of them as models of what “real” intellectuals and writers looked and sounded like. For obvious reasons, the public thinkers who whom I was drawn were primarily African or black, and many of them were women. I was drawn to their minds but I was impressed too with the bodies from which their minds operated – unruly and brown and so different from the mainly angular lean spectacle-wearing bodies of the men who dominated the backs of book jackets that filled the library in my university.

They weren’t my peers. Nothing about them felt within reach. Instead, they represented what, if I was very lucky and worked very hard, might lie in my future. They were a set of goals. Also, because their own age and experience were ever-expanding; they were also a group of people with whom I could never catch up: They were moving targets.

Of course it would be wrong to give the impression that my admiration for them did not stop me from engaging their work critically. I disagreed here and there with some of their ideas. Sometimes as I read them (because my formative adult years were pre-podcast and Youtube clips, when even commencement addresses had to be published and read in print) I shook my head and called a friend and together we would compare notes. Still, my posture towards each of these greats, was that of a student to a set of wise teachers. So when the esteemed older writer ad I engaged, I assumed a position in relation to him that was familiar and comfortable: I was appropriately and genuinely deferential.

There is a beauty in this. In many ways the relationships that occur across generations are what make humans exceptional. Humans and other primates keep our young close. Our societies are complex because we survive across generations and we cultivate relationships well past the point of physiological maturity. In other words we continue to learn from and love one another long past the biological utility of these emotions.

In contrast of course both literature and history are full of stories about the great friendships and dramatic rivalries that have always existed between contemporaries. Aunts and uncles play a special role in nurturing and teaching but siblings – ah, siblings are both a source of camaraderie and deep-seated resentment. There is something about being in a similar stage of emotional and physical stage of maturity that shifts the dynamic. Peers – those who are equals by virtue of age and accomplishment and a range of other factors – can both be the deepest enemies and the closest of allies.

In societies where race operates as a divisive force (which is of course every society where race has any meaning), contemporaries who are raced as “black” are often pitted against one another. There is only room for one spokesperson. The space for black women’s voices in particular is limited. I was told when I first started writing, that I should not approach a certain news outlet as they already had a regular black woman columnist writing for them. For black people there is only so much room. This is in stark contrast with the space provided to white writers. For them there are no limits, no questions that the white male perspective is already covered. Each white man who comments is already seen as an expert and so his commentary is seen on its own merits.

Charles Van Onselen has written, and Johnny Steinberg and Du Preez. They are not white men: they are themselves. Media managers sometimes think that having two or three or four black voices weighing in on a topic might be “repetitive.” This is of course a standard that isn’t applied for whites, especially for white men.

This law of limited space is applied especially stringently for black people who are contemporaries of one another. The older generation is allowed to have space – but for up-and-coming voices, well, the space is winnowed.

I make these perambulatory comments to explain why I am increasingly drawn to the public display of support for the work of my contemporaries – where it is warranted. For me, the politics of supporting the intellectual efforts of my contemporaries moves beyond the celebration of black girl magic – a term and phenomenon I have critiqued elsewhere.

Instead, I am mindful that while the intellectual work of black people is often celebrated, it is seldom reviewed with any depth or seriousness. The true hallmark of supporting African thinking it seems, ought to be in the extent to which the work is genuinely engaged, debated and taken seriously on its merits.

Both the volume and quality of work being produced by my contemporaries – black writers in their 30s and 40s – is impressive. The space that was once occupied almost exclusively by the cohort of living writers and intellectuals who influenced my intellectual development – those who cut their teeth in the 1970s and 1980s – is being replaced by people my age. So, while on the one hand there is deep resistance on the part of media owners, universities and established institutions to the multiplicity of our voices, and a real cap on how many of us can be celebrated, on the other hand the demographics are on our side. We have amassed enough experience and credibility – tenuous though these may be – to be on the rise.

The commentary of this generation is substantively different from the commentary of the past. Those who were in their 30s and 40s in the Mandela era embraced the Rainbow Nation. Indeed, they were authors of the narrative and were deeply implicated in the fight for a discourse of multiracialism. This generation of public intellectuals, writers and activists are more ambivalent about these ideas. They write about their experience of living within this ideology; about the Arendtian notion of the banality of evil that has arisen from the very idea of the rainbow.

Three new books illustrate this especially well. It is no accident that each of these books are authored by African women in their 30s and 40s. The first is Redi Tlhabi’s book Khwezi: The remarkable story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo about the woman who accused South Africa’s President, Jacob Zuma of raping her, and who was let down by a whole chain of people, and indeed by a movement. The second is Pumla Gqola’s autobiographical collection of feminist essays; Reflecting Rogue: Inside the mind of a feminist. The last is Lindiwe Hani’s book Being Chris Hani’s Daughter which explores sadness, trauma, addiction and independence.

Each book explores the complexity of having grown up with one foot in Apartheid South Africa and being shaped by its pathos. Each book is authored by a woman who was a child during Apartheid but has lived her entire adult life in a “free” South Africa.

In different ways, each of these books is really about the end of innocence – about how each author has marked her departure from the halcyon days when the African National Congress and its leaders were held in high regard, to today, when they are seen by and large as having betrayed the ideals of the struggle.

While the daily news headlines in South Africa are obsessed with the political machinations of the day – with the Guptas and corruption and breaches of the Constitution, these books are about something deeper. Tlhabi, Gqola and Hani write about the emotional manifestations of this mass betrayal. Each of these books is concerned with the psychic effects of the ANC’s callousness and what is has meant for the post-Apartheid generations who have been its collateral damage. In Hani’s case, the turn to drugs – and the “shame” and fear of bringing the family and movement into disrepute because of being Chris Hani’s daughter – offers a rich backdrop for the unfolding and tragic dramas of both the party and her life. For Gqola, the continuation of institutional sexism and racism, in systems she has had to navigate, speak to the abrogation of the new government’s duties. And for Tlhabi, the treatment of Fezeka both during the trail but more importantly, in her difficult childhood in exile, are a testament to the myth of justice that has always surrounded the ANC.

Over the next three months I will review each of these books. My aim is to examine each book separately but also to talk about the connections made in the analysis proffered by the women who have written them. My contemporaries are engaged in the important work of looking back and surveying the wreckage of the past 40 years of South African history. They are bridging the generation that bred them and the post-Apartheid era that has shaped them. In the process, they are writing a new future. I hope you can join me as we think together about their work and their words.

Contemporary affairs–on reading Lindiwe Hani, Pumla Gqola & Redi Tihabi

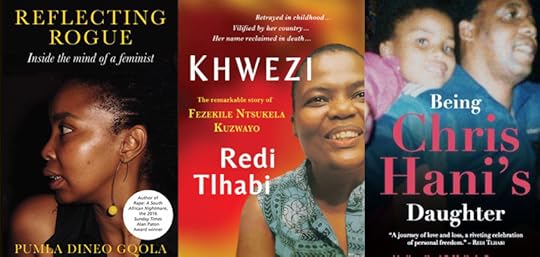

Books by Pumla Gqola, Redi Tlhabi and Lindiwe Hani.

Books by Pumla Gqola, Redi Tlhabi and Lindiwe Hani.Over the past few months I have been in correspondence with a South African intellectual and academic who is old enough to be my father. Our exchanges have been rich and warm. I have long admired him. When I worked up the courage to share with him my excitement about our conversations and told him I appreciated the time he had taken to read my work, and when I said I was especially grateful because of the place he has long held in my mind as someone of true intellectual integrity, he was kind enough to delve into his archives and share a review he once received from one of his own heroes. He told me he remembered his own gratitude for the attention he had received from this man – a writer and thinker of great stature – whom he too had read and admired from a distance for years. It was a touching act, a reminder to a younger writer struggling with her voice and her place in her society that she was not the first to have jitters; a reminder that even the greats doubt themselves at first. In part, the form and candor of the exchange was possible because of the positions we occupy on the spectrum of our careers. He sits well past mid-age; his most productive years (though perhaps not his best) behind him. I am much younger and so for me the future holds a different set of possibilities.

When I was younger everyone whose intellect I admired was much older than I was. I read people who were published, which 20 years ago when I was reading voraciously as a student, meant they were established. The timeframe between thinking and writing and then between writing and getting published, was much longer then. The spaces were fewer and the options narrower and this meant that to have your name in print – in an era when there literally no such thing as online – you were very talented and connected and lucky.

Writers like Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag and Ursula Le Guin in the United States; Sindiwe Magona and Lindiwe Mabuza who were South African; Ayi Kwei Armah in Ghana and Chinua Achebe who seemed to own the world – they were all much older than me and partly as a function of their age they felt impossibly wiser than I might hope to ever be.

I grew up with pictures of them as models of what “real” intellectuals and writers looked and sounded like. For obvious reasons, the public thinkers who whom I was drawn were primarily African or black, and many of them were women. I was drawn to their minds but I was impressed too with the bodies from which their minds operated – unruly and brown and so different from the mainly angular lean spectacle-wearing bodies of the men who dominated the backs of book jackets that filled the library in my university.

They weren’t my peers. Nothing about them felt within reach. Instead, they represented what, if I was very lucky and worked very hard, might lie in my future. They were a set of goals. Also, because their own age and experience were ever-expanding; they were also a group of people with whom I could never catch up: They were moving targets.

Of course it would be wrong to give the impression that my admiration for them did not stop me from engaging their work critically. I disagreed here and there with some of their ideas. Sometimes as I read them (because my formative adult years were pre-podcast and Youtube clips, when even commencement addresses had to be published and read in print) I shook my head and called a friend and together we would compare notes. Still, my posture towards each of these greats, was that of a student to a set of wise teachers. So when the esteemed older writer ad I engaged, I assumed a position in relation to him that was familiar and comfortable: I was appropriately and genuinely deferential.

There is a beauty in this. In many ways the relationships that occur across generations are what make humans exceptional. Humans and other primates keep our young close. Our societies are complex because we survive across generations and we cultivate relationships well past the point of physiological maturity. In other words we continue to learn from and love one another long past the biological utility of these emotions.

In contrast of course both literature and history are full of stories about the great friendships and dramatic rivalries that have always existed between contemporaries. Aunts and uncles play a special role in nurturing and teaching but siblings – ah, siblings are both a source of camaraderie and deep-seated resentment. There is something about being in a similar stage of emotional and physical stage of maturity that shifts the dynamic. Peers – those who are equals by virtue of age and accomplishment and a range of other factors – can both be the deepest enemies and the closest of allies.

In societies where race operates as a divisive force (which is of course every society where race has any meaning), contemporaries who are raced as “black” are often pitted against one another. There is only room for one spokesperson. The space for black women’s voices in particular is limited. I was told when I first started writing, that I should not approach a certain news outlet as they already had a regular black woman columnist writing for them. For black people there is only so much room. This is in stark contrast with the space provided to white writers. For them there are no limits, no questions that the white male perspective is already covered. Each white man who comments is already seen as an expert and so his commentary is seen on its own merits.

Charles Van Onselen has written, and Johnny Steinberg and Du Preez. They are not white men: they are themselves. Media managers sometimes think that having two or three or four black voices weighing in on a topic might be “repetitive.” This is of course a standard that isn’t applied for whites, especially for white men.

This law of limited space is applied especially stringently for black people who are contemporaries of one another. The older generation is allowed to have space – but for up-and-coming voices, well, the space is winnowed.

I make these perambulatory comments to explain why I am increasingly drawn to the public display of support for the work of my contemporaries – where it is warranted. For me, the politics of supporting the intellectual efforts of my contemporaries moves beyond the celebration of black girl magic – a term and phenomenon I have critiqued elsewhere.

Instead, I am mindful that while the intellectual work of black people is often celebrated, it is seldom reviewed with any depth or seriousness. The true hallmark of supporting African thinking it seems, ought to be in the extent to which the work is genuinely engaged, debated and taken seriously on its merits.

Both the volume and quality of work being produced by my contemporaries – black writers in their 30s and 40s – is impressive. The space that was once occupied almost exclusively by the cohort of living writers and intellectuals who influenced my intellectual development – those who cut their teeth in the 1970s and 1980s – is being replaced by people my age. So, while on the one hand there is deep resistance on the part of media owners, universities and established institutions to the multiplicity of our voices, and a real cap on how many of us can be celebrated, on the other hand the demographics are on our side. We have amassed enough experience and credibility – tenuous though these may be – to be on the rise.

The commentary of this generation is substantively different from the commentary of the past. Those who were in their 30s and 40s in the Mandela era embraced the Rainbow Nation. Indeed, they were authors of the narrative and were deeply implicated in the fight for a discourse of multiracialism. This generation of public intellectuals, writers and activists are more ambivalent about these ideas. They write about their experience of living within this ideology; about the Arendtian notion of the banality of evil that has arisen from the very idea of the rainbow.

Three new books illustrate this especially well. It is no accident that each of these books are authored by African women in their 30s and 40s. The first is Redi Tlhabi’s book Khwezi: The remarkable story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo about the woman who accused South Africa’s President, Jacob Zuma of raping her, and who was let down by a whole chain of people, and indeed by a movement. The second is Pumla Gqola’s autobiographical collection of feminist essays; Reflecting Rogue: Inside the mind of a feminist. The last is Lindiwe Hani’s book Being Chris Hani’s Daughter which explores sadness, trauma, addiction and independence.

Each book explores the complexity of having grown up with one foot in Apartheid South Africa and being shaped by its pathos. Each book is authored by a woman who was a child during Apartheid but has lived her entire adult life in a “free” South Africa.

In different ways, each of these books is really about the end of innocence – about how each author has marked her departure from the halcyon days when the African National Congress and its leaders were held in high regard, to today, when they are seen by and large as having betrayed the ideals of the struggle.

While the daily news headlines in South Africa are obsessed with the political machinations of the day – with the Guptas and corruption and breaches of the Constitution, these books are about something deeper. Tlhabi, Gqola and Hani write about the emotional manifestations of this mass betrayal. Each of these books is concerned with the psychic effects of the ANC’s callousness and what is has meant for the post-Apartheid generations who have been its collateral damage. In Hani’s case, the turn to drugs – and the “shame” and fear of bringing the family and movement into disrepute because of being Chris Hani’s daughter – offers a rich backdrop for the unfolding and tragic dramas of both the party and her life. For Gqola, the continuation of institutional sexism and racism, in systems she has had to navigate, speak to the abrogation of the new government’s duties. And for Tlhabi, the treatment of Fezeka both during the trail but more importantly, in her difficult childhood in exile, are a testament to the myth of justice that has always surrounded the ANC.

Over the next three months I will review each of these books. My aim is to examine each book separately but also to talk about the connections made in the analysis proffered by the women who have written them. My contemporaries are engaged in the important work of looking back and surveying the wreckage of the past 40 years of South African history. They are bridging the generation that bred them and the post-Apartheid era that has shaped them. In the process, they are writing a new future. I hope you can join me as we think together about their work and their words.

September 26, 2017

‘Kati Kati’ shows us a Kenya in limbo

Kati Kati, the fifth collaboration from One Fine Day Films and Ginger Ink productions, is a beautiful movie. Set in the land in between, (literally Kati Kati in Swahili), it focuses on Kaleche, our protagonist, who having woken up in this liminal space, embarks on the journey to find out how she died and the circumstances that keep her suspended in this unknown.

Kati Kati trailer

Though a film about dead people, Kati Kati is not just a film about dead people. Mbithi Masya’s work is rather, a poetic portrayal of little triumphs amidst tragedy, the humor implicit in our foibles and the work it takes for us to let go. What’s more, in eliding the themes common in many films from Kenya (developmentalist, urban violence, big man politics), Kati Kati shines its light instead on us; our internal follies, the performances we take up to run from them and how they leave us suspended, unable to launch ourselves into whatever destinies await us.

While Kaleche is working out how she got here, through the stories of three residents of this afterlife, the film makes us reflect on the deaths whose details we are always so ready to obscure in Kenya; suicide, post-election violence and drunk-driving accidents. These, from my experience, are the ways of dying that are most easily made invisible, not just because they are taboo — especially suicide — but from the pain of their needlessness. This, it appears, is what the film sheds light on: the murky grief these deaths produce. It does this in ways that also bring out the irony, crassness and irreverent humanities that characterize much of daily life in Kenya. The plot line melds together what I have been trying to understand about Kenyans for a long time; a seemingly simultaneous flagrant zest for life and hesitant fascination with death.

Take one scene in the film in which a bash is called to celebrate the departure of Mickey from Kati Kati; it is all bells and whistles, whisky and DJs; the whole works. At the same time, those in attendance are still disavowing the decisions that would see them proceed to a more certain place like Mikey, and they couch their guardedness over their own mortality with pool parties, basketball games, painting and ordering clothes from unseen hands through notes written on mini blackboards.

Though the environment chosen as the site of this film is austere — Kati Kati is essentially an abandoned lodge in a dehydrated savanna — it is a stunning backdrop for the larger questions being worked out here. The minimalist background, nonetheless, accented with select focus on color, nature and climate, accompany the changes in tone throughout the film. It is thunder that stands out as the marker for the most meaningful transitions between critical scenes and, above all, for the characters.

The acting does not disappoint. A special shout out to Paul Ogola who plays Mikey — a young man who commits suicide just before his graduation — and embodies this character with such intimacy and power, giving us sublime glimpses into the grief, irony, tragedies and triumph that he represents.

Is Kati Kati a metaphor for our present socio-political moment in Kenya? We are after all in a political limbo produced by stolen elections, and dramatized further when the head of the Central Organization of Trade Unions (COTU) can make a TV plea to the president to try and be sober.

Whichever directions Kati Kati leads each of us to, we are steered there because of its poesis, originality and generosity towards our various human syncopations — even those Kenyan eccentricities that are thankfully not globalized.

First shown locally at the February 2017 NBO Film Festival (and also now available on Showmax), Kati Kati stands out for its gentle and layered portrayal of the little triumphs amidst affliction that we take on to redeem life and death — no matter how in between these may be.

September 25, 2017

Is environmental philanthropy still a white man’s game?

Local communities planting trees on Mount Gorongosa. Image via Gorongosa National Park Vimeo page.

Local communities planting trees on Mount Gorongosa. Image via Gorongosa National Park Vimeo page.In our ravaged anthropocene, few things seem more noble and worthwhile than rebuilding a national park, increasing the stock of wildlife, preserving biodiversity and saving the ecosystem. If these efforts manage to turn a profit by attracting tourists, even better. But what happens when well-intentioned foreign aid efforts consider would-be beneficiaries as its enemies?

In her new book, The White Man’s Game, the journalist Stephanie Hanes locates the restoration efforts of American philanthropist Greg Carr in Gorongosa National Park in the central region of Mozambique within the broader context of foreign aid. Hanes shows that many of the challenges to the preservation effort stem from a one-dimensional approach that sees local residents as obstacles rather than partners in the development effort.

The park in Gorongosa was founded by Portuguese colonists in 1920, but was closed due to the liberation struggle and the civil war that followed Mozambique’s independence from Portugal in 1975. When Greg Carr, who made his fortune in the telecommunications industry, decided to become a full-time philanthropist, he “discovered” the beauty of Gorongosa and decided to offer his help to the Mozambican government. His hope was to restore the park to its former glory. Since 2004, Carr, his Mozambican colleagues, and a growing team of scientists, rangers and other workers have attempted to rebuild the animal population with imports from neighboring South Africa and elsewhere and have taken measures to protect the fragile ecosystem around Mount Gorongosa, from which the park takes its name. After a more general introduction to the challenges of conservation, the link to tourism, and the role of “eco barons” in saving wildlife, the book chronicles the ups and downs of Carr’s endeavor in Mozambique.

The book’s strengths lie in making the link between conservation and development policy and practice more generally, and in chronicling a specific case of how the semi-privatization of space cuts local residents off from their habitat. A short history of colonial writing about nature, wildlife, and people in Africa provides the background for the argument that the narratives that western explorers (and eco barons such as Carr) have created for audiences at home show how the newly discovered “wilderness” becomes a mere backdrop for these explorers’ own adventures. Though superficially these narratives are about nature, animals and people in the places visited, the real protagonists are the foreigners who look for an “out-of-place experience” — the philanthropists, development workers, and tourists. This is, of course, a familiar trope in the colonial imagination aka The Heart of Darkness. What is new is the greenwashed variety in which the western explorer ventures into the wild in the name of conservation.

As a consequence, Hanes successfully shows how not only the narratives of local populations in Gorongosa are marginalized, but also how residents are physically removed from the protected area through enclosures and planned resettlement. Park managers understand forms of community resistance to their interventions as obstacles that need to be overcome by educating people about the benefits of conservation, overlooking the ways in which communities have taken care of their natural habitat for a long time. For example, research has shown that peasants living in the area developed a sophisticated system of slash-and-burn agriculture that park managers only saw as a menace to the park’s ecosystem. As a form of resistance against the prohibition of controlled wildfires, peasants neglected their sophisticated system, letting wildfires burn uncontrolled and thus turning the park managers’ concerns into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But more generally, communities’ concerns find expression in the narratives of angry spirits that react to the park project’s alleged prioritization of material possessions over the respect for human life. Marginalizing the surrounding communities for the sake of wildlife protection has exposed, in the eyes of the communities, the real purpose of the park endeavor: privatizing space for private profit. It is this neoliberal logic that is the most hard-hitting point of Hanes’ critique, paralleling a recent critique of the philanthropic non-profit industrial complex. Hanes states in the Afterword to the book that those involved in the project have already dismissed the thrust of her analysis although they have not yet read her book. They feel misunderstood; after all, their intentions are good.

The book is a reminder of the complicated nature of the politics of development, but more importantly, it points to a source of misguided intervention, which is mistrust towards the population the work is intended to benefit. As Hanes describes it, this is captured by the term poaching — a central challenge for conservation efforts. Poaching has negative connotations in American and European culture, the positive (or more neutral) term being hunting. Just think of hunting safaris: locals poach and tourists hunt. Poaching can, however, have a diverse set of causes and is not limited to organized crime.

White Man’s Game provides an important corrective for the image of the white savior of wildlife in Africa. It is a valuable read for broad audiences interested in development, conservation, resilience and practices of community resistance. That said, I wished for more exploration in the book of the contradictions within both the western and the local narratives. Residents of Gorongosa, such as the chiefs who understand themselves as gatekeepers, want to benefit from the park, the tourists, the money flowing in. But they want to keep the state (and, by extension, development workers) out. The region is known for a deep mistrust towards the Frelimo government, and the chiefs’ anti-statist stance provides Renamo, the former rebel movement and now largest opposition party, with opportunities for mobilization. That’s why the Gorongosa region has been a staging ground for recent political violence.

Hanes acknowledges the existence of this diverse set of motives of community residents’ reactions to the park, but doesn’t explore them in greater detail. Her narrative remains focused on the white man; local resident’s stories are featured in the book but do not form a red thread throughout. This is a missed opportunity in narrating the politics of development as seen from below.

September 24, 2017

The Third World Quarterly debacle

Helen Zille is the leader of South Africa’s second largest political party, the Democratic Alliance. Her praise of colonialism and the supposed “good” that the selfless and enlightened colonizers (including white South Africans) brought to colonized peoples may have disappeared from South African public debates after her half-hearted apology. It turns out, however, she has since become a hero of colonial apologists far beyond South Africa.

In “The Case for Colonialism,” an academic paper recently published by the British journal Third World Quarterly, Bruce Gilley, a political scientist from Portland State University in the United States, wrote it is time to stop looking at Western colonialism as something that brought chaos, oppression and unthinkable suffering. Rather, he argued, colonialism was “objectively beneficial and subjectively legitimate in most of the places where it was found.” He also calls for recolonization of many parts of the world that cannot and will not ever function and prosper on their own unless caring and altruistic white Westerners come to their rescue.

Gilley opened his article with praise for Zille, whom he sees as the voice of reason in the hostile and biased anti-colonial environment and the defender of “truth” and the European civilizing project. In line with Zille’s claims that colonialism brought many benefits to the colonized, Gilley notes that the West needs to figure out how to “unlock those benefits again.” He further argues that the world will remain a chaotic place unless the Western powers take up their “civilizing mission” once again and “reclaim the colonial toolkit and language as part of their commitment to effective governance and international order.”

For those not familiar with academic publishing, prominent peer-reviewed journals are not expected to publish garbage like this. Good academic journals have editors who rely on a blind peer-review process in order to ensure reliability, validity and academic rigor of the arguments and highlight any possible shortcomings of the research. If Third World Quarterly did this properly, Gilley’s piece would have never been published – not necessarily because the views and arguments in his paper are highly offensive to so many people but because it is full of inaccuracies, fallacies, unsubstantiated and wild claims and anecdotal evidence.

A lot has happened in the short period since the publication of Gilley’s paper a few weeks ago. Fifteen members of the editorial board of the Third World Quarterly (they include Mahmood Mamdani, Lisa Ann Richey and Vijay Prashad) have resigned in protest. It turns out the editorial board was not consulted in this instance and the peer reviewers rejected the paper, but the editor still decided to publish it. There is a petition that calls for retraction of the piece going around; others have expressed disdain for the invitation to academics by the journal’s editor-in-chief, Shahid Qadir, to submit counter arguments and engage in a debate about the benefits of colonialism. Nathan Robinson, editor-in-chief of CurrentAffairs.org, wrote a “quick reminder of why colonialism was bad;” Vijay Prashad explained in Scroll.in why he resigned from the editorial board; political scientist Brandon Kendhammer, who researches Nigeria, published a post on the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog reminding everyone of colonialism’s ugly legacy; and Portia Roelofs and Max Gallien wrote in the LSE Impact Blog that Gilley’s piece is nothing but ‘travesty, the academic equivalent of a Trump tweet, clickbait with footnotes.’

Colonialism included the invasion and takeover of foreign lands, slavery, unthinkable brutality, subjugation of indigenous peoples, dispossession and economic exploitation through authoritarian and ruthless rule. It also included the use of knowledge and education to dehumanize colonized populations, diminish their cultures and humanity and maintain structural domination during and long after the colonial rule.

In Gilley’s entire piece, there is literally nothing about the mass murder, genocide, oppression, looting, exploitation and other evils that the European colonizers wrought all over the world. Nathan Robinson notes that instead of conducting a thorough evaluation of the colonial record, Gilley’s piece distorts the record and deliberately conceals the overwhelming evidence of horrific crimes. He adds that “the result is not only unscholarly, but is morally tantamount to Holocaust denial.”

Racism and the notion of white supremacy were at the core of the colonial project. Ramón Grosfoguel, who has extensively researched colonialism in the Caribbean, writes that European epistemology and patriarchy had been exported to the colonies “as the hegemonic criteria to racialize, classify and pathologize the rest of the world’s population in a hierarchy of superior and inferior races.” These are well-established facts. Yet, in his entire piece, Gilley doesn’t once mention racism or white supremacy.

Gilley argues that the Western colonial powers, through noble acts and “rational policy processes,” left behind functioning states, market economies and pluralistic and constitutional polities. All this was destroyed by unscrupulous and corrupt “anti-colonial agitators” in the years after independence. While it is true that many former colonies have suffered under bad leaders, it is a blatant lie that the colonialists left behind stable states and economies. As the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie points out, “start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.”

Gilley claims that “the lack of state capacity to uphold the rule of law and deliver public services was the central tragedy of “independence” in the Third World.” Anyone who has read a thing or two about colonialism knows that building capacity in the colonies was never a priority of the European colonizers. What they did instead was destroy whatever structures and capacity they found in the colonies. After decades of looting, exploitation and racist denigration, dehumanization and oppression, they left behind empty shells.

For Gilley, problems in many African countries that have faced violent conflict and instability since independence have nothing to do with colonial policies, divide-and-rule tactics, arbitrary boundaries drawn up by the colonizers, manipulation of ethnic and other identities, or blatant economic exploitation and pillaging of the colonies, their resources and labor for the benefit of the colonizers. Rather, the former colonies are dysfunctional and underdeveloped solely because the people in these societies are not capable of governing and developing themselves and their economies.

According to Gilley, many of the formerly colonized societies are still uncivilized, their populations are not yet fully human and lack creativity and capacity for effective self-rule. This leads him to his grand proposal: ‘reclaim the colonial governance.’ He calls on the Western powers to recolonize the wretched in order to civilize them and bring to them much needed help, economic prosperity and good governance. How would this look like in practice? Create European states in Africa and bring hope, stability and economic prosperity to Africans. Or let former colonizers go back and “fix” their past possessions. As Gilley suggests in his paper, allow Belgians to rule the Congo again, as they have done so splendidly in the past.

That’s it. Gilley has found the solution to most of the world’s problems. Recolonize the world, impose Western ways of life, destroy any anti-colonial agitators that may resist this and we will have world peace.

We should not be surprised to see Gilley’s white supremacist propaganda masquerading as academic research. The anthropologist Vito Laterza – who wrote on this site about Zille’s praise for colonialism when she first made those claims – notes that the open and subtle racism, notions of white and Western superiority or the belief that colonialism was not all that bad have been the default positions of the Western academia for centuries. However, the current “shift from liberal racism to explicit white supremacy” in the United States and Europe have signaled to people like Gilley that it’s ok to come out and show their true racist colors.

There are many Gilley’s out there. Let them come out. Expose them and their racism, hatred, inhumanity, intellectual ineptitude, inferiority and deplorable propaganda and lies. And fight them.

September 22, 2017

The golden age of the Nigerian short film

Still from Gone Nine Months.

Still from Gone Nine Months.We are presently experiencing something of a golden age of Nigerian short films. From Iquo B. Essien’s moving, impassioned Aissa’s Story (2013), which was an official selection of the 2015 edition of the prestigious Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), to the marvelously quirky work of Abba T. Makama, whose hilarious Direc-toh (2010) was screened at the Eko International Film Festival in 2011, Nigerian filmmakers are embracing the short form as more than just a cinematic calling card. Both Essien and Makama have made multiple shorts—Essien’s New York, I Love You (2016) screened to sold-out audiences at Lincoln Center and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, while Makama’s Quacks (2012) has been met with similar enthusiasm throughout West Africa and the diaspora. Their careers model a respect for the short film that is altogether inspiring, and they are but two examples of Nigerian artists successfully testing the boundaries of the form.

Another is Lola Okusami, who was born in the United States but raised in Nigeria. Okusami studied journalism at the University of Minnesota before beginning a career in print media, corporate communications, and television. She recently completed her first film, the impressive short Gone Nine Months (2017), which she shot in Calabar.

Gone Nine Months trailer.

Set in 1993, in and around the fictional University of Southwestern Nigeria (modeled, perhaps, on Southwestern University, in Ikeja), Gone Nine Months depicts the experiences of two academics and their five children, all of them coping (albeit in vastly different ways) with the stresses of life under military rule. The matriarch, an accomplished geophysicist named Agnes (played by the talented, immensely appealing ’Najite Dede), is pursuing various postdoctoral fellowship opportunities in France and the United States (and has her heart set on the latter). The patriarch, the taciturn Tunde (Olu Euba), initially (if brusquely) claims that he supports his wife’s ambitions (“Whatever you want to do, do it!”), but later reveals that he does not, in fact, want Agnes to travel—much less to be abroad for as long as nine consecutive months. Tunde’s all-too-recognizable patriarchal conservatism is a key element of the film—the repressive fulcrum of its original plot.

The film opens with economical introductions to each of the couple’s five children. Ensconced in staff quarters on a quiet street near the university, the siblings await the arrival of their parents from what is later revealed to have been a tense “face-off” between members of the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) and the military government. The eldest of the siblings, Isha (Zoe Favour), sits reading This Is Our Chance: Plays from West Africa (1957), a major collection by the Nigerian playwright James Ene Henshaw, while the others (including Inimfon Iniama’s Oumou, who is close to Isha in age) enjoy a series of decidedly less intellectual pursuits. The film’s plot is set in motion by the delivery of a letter informing the hardworking Agnes that she has finally been offered a postdoctoral fellowship in France. (Tellingly, the children at first worry that the delivery is a “letter bomb” of the sort that terrorized journalists, academics, and political activists during the military dictatorship of General Sani Abacha.) When he returns home to news of his wife’s fellowship opportunity, Tunde seems more interested in watching the evening news, which is reporting on the standoff of which he himself has long been a part. (These interpolated television broadcasts—staged by Okusami—are impressive approximations of the era’s dominant televisual aesthetic, as well as a subtly effective means of evoking actual ASUU struggles, particularly the union’s efforts to protest the unjust dismissal of teachers by the Abacha regime.)

Much of what follows centers on the visa interviews for which Agnes so thoroughly and so hopefully prepares. The first interview, at the French embassy in Lagos, does not go well; Agnes is turned down. “They said I could not show sufficient proof that I would ever come back,” she says, in exhausted disbelief. Finally, Agnes is offered a fellowship at the American Institute of Geophysics, and the future looks bright—she promises to save much of her stipend for use on shoes, multicolored jeans, and other presents for her children—until the family receives some startling news about Oumou.

Gone Nine Months is a well-acted and beautifully shot film, full of details that powerfully evoke the precise historical moment of the early 1990s. Okusami, who left Nigeria in 1996, and says that she can “remember the early 90s as fraught with this air of desperation,” told me that she was interested in conveying this atmosphere—the product of a military government whose predations had led to seemingly constant university strikes, including those affecting the filmmaker’s parents, both of them lecturers. That Okusami manages to capture this panicked period in fewer than 22 minutes is altogether remarkable. The semiautobiographical Gone Nine Months gets at the generalized anxieties that came with military rule, showing how the traumas of Abacha’s regime reached into every corner of everyday life in Nigeria. This is a most welcome contribution to the golden age of the Nigerian short film.

September 17, 2017

‘Africa Rising’ in retreat: Signs of new resistances

Image via UN Photo Flickr.

Image via UN Photo Flickr.At the very moment that Africa’s GDP ceased its rapid 2002–11 increase, a profound myth took hold in elite economic and political circles, embodied in the slogan “Africa Rising.” That myth persists. Deutsche Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann claimed in June 2017 at a Berlin conference, “Africa stands ready to benefit from an open world economy. Its economic outlook is positive.” The conference was arranged by German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble to promote his G20 “Compact with Africa,” whose “main aim is to lower the level of risk for private investments” (but in the run-up to the German election, he and Angela Merkel were obviously also concerned to give the impression the strategy would reduce Europe’s African refugee crisis).

In reality, after the 2011 peak of the commodity super-cycle and subsequent price crash, it was simply illogical to proclaim that Africa was prospering in “an open world economy”, given that so many of the continent’s economies depend on mineral and oil deposits whose extraction is dominated by transnational corporations (TNCs) and whose prices have been on a roller-coaster since 2002. A brief commodity price recovery in 2016 and ongoing drop in the value of most African currencies did not set the stage for renewed competitiveness, business confidence, or TNC investment, but instead catalyzed another round of fiscal crises, extreme current account deficits, sovereign debt defaults and intense social protests.

There is no hope of a decisive upturn on the horizon, despite hype surrounding China’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) mega-infrastructure projects, touted for restoring some market demand for construction-related commodities. As Xin Zhang explained, “Although there is an element of US-China competition for global hegemony behind the OBOR, the main driving force is the pressure from ‘over-accumulation’ in a typical capitalist economy when it approaches the end of a major cycle of capitalist cyclic change…. However, in China, there is also an ongoing debate about whether it is economically rational to pour such huge amounts of money into low-return projects and high-risk countries, especially in the case of massive infrastructural projects.”

The largest of China’s “Maritime Silk Road” enterprises reaching into Africa was Tanzania’s $11 billion Bagamoyo port, planned in 2013 to handle ten times more containers than nearby Dar Es Salaam harbor. The project, Forbes observed, was “vying to become the largest port in Africa upon completion,” but was cancelled in 2016 due—according to Deloitte and Touche—“to austerity measures introduced in Tanzania in order to reduce the widening budget deficit.”

At the same time in Durban, the $20 billion expansion of the continent’s current main container port (which had also aimed at increasing containers 8-fold to 20 million per annum by 2040) was delayed until at least 2032. Corruption in lending and locomotive acquisition (both from China) implicating the South African parastatal Transnet is one factor; rising social resistance to port expansion is another; but the overarching problem was the post-2011 collapse of the Baltic Dry Index, signifying a profound crisis across world shipping. Although the $5 billion Lamu port construction in Kenya now underway not far from the Somalia border will link to South Sudan’s oil fields, between civil war there and Al-Shabaab’s attacks on Kenya (including kidnapping of a top official when she was unveiling Lamu’s spatial plan in July), the project is extremely risky, and 2017 also witnessed widespread community protest, including against a $2 billion coal fired power plant at the port, on grounds of climate change.

Although a $3.2 billion Nairobi-Mombasa rail line was recently built and a $3.6 billion Uganda-Tanzania oil pipeline is planned, and although Ethiopian sweat-shop manufacturing is booming and can now be exported directly via n a $4 billion Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad, all with Chinese aid, the downturn halved the value of East Africa’s large infrastructure projects under construction last year. Southern Africa also faced a 22 percent fall in project numbers (to 85 in 2016), down from a cumulative $140 billion in 2015 to $93 billion in 2016, Deloitte also reported. Other recent mega-project reversals associated with Chinese over-reach or outright failure, according to the Wall Street Journal, include cancelled railway initiatives in Nigeria ($7.5 billion) and Libya ($4.2 billion), petroleum expansion in Angola ($3.4 billion) and Nigeria ($1.4 billion), an irreparably damaged coal-fired power-plant in Botswana ($1 billion), and metal smelting investments in the DRC and Ghana ($3 billion each). The world’s largest dam, the $100 billion Inga Hydropower Project on the Congo River (three times the size of China’s Three Gorges), is also on indefinite hold after the World Bank pulled out last year and after Obama Administration officials rejected Beijing’s 2014 appeals for a joint venture.

The crisis of the extractive industries is also witnessed in the plummeting share prices of most mining houses, by more than 75 percent from their early 2015 levels, led by those with African exposure. Neither the entry of the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) bloc nor the G20’s meager new aid promises—mainly aimed at subsidizing TNCs—can disguise the generalized stagnation within the circuits of the world economy most important to Africa or indeed to global prosperity and ecological sanity.

Even before the 2011 commodity peak and 2015 crash, the neoliberal export-oriented strategy had done enormous damage to human development, gender equity, and the natural environment. Although rates of poverty, mortality and morbidity, and education have improved somewhat (especially after the West’s G7 debt relief package in 2005 which allowed the phase-out of what had been prohibitive user fees for basic state services), the conditions for reproduction of daily life in Africa have not, especially since the onset of global recession in 2008.

Africa’s per-capita GDP levels did indeed rise rapidly from 1998 until then, but with very little trickling down. In 2013, the African Development Bank’s chief economist, Mthuli Ncube, made the spurious claim that “one in three Africans is middle class.” In 2017, the bank reiterated that “one of the main drivers of the surge in consumer demand in Africa is the continent’s growing population (currently 1 billion) and expanding middle class (estimated at 350 million).” But Ncube had defined “middle class” as those who spend anywhere between $2 and $20 per day, with 20 percent in the $2–4 range and 13 percent from $4–$20. Both categories represent poverty incomes in most African cities, whose price levels make them among the world’s most expensive. The share of those spending above $20 per day was less than 5 percent and shrinking, Ncube’s own data revealed.

A central reason for the disparity between official talk of “Africa Rising” and the deep poverty of most of the continent’s people is sheer looting: illicit financial flows (IFFs) as well as legal financial outflows in the form of profits repatriated to TNC headquarters. The most exploitative channels of foreign direct investment (FDI) tend to be those that come in search of raw materials. After the commodity crash, annual FDI inflows to Africa slowed by 15 percent from 2008 to 2016, but despite the reversal, the extractive industries’ existing pressures on people and environments intensified, ascorporate desperation heightened site-specific industry malpractices, ecological degradation, social abuse, and labor exploitation. The metabolism of capital versus nature and society has amplified to the point even the mining houses’ Corporate Social Responsibility is in profound retreat.

That desperation was most obvious during 2015. The British mining firm Lonmin’s London listing plummeted from a high price of 427,800c per share in 2007 to just 41c in early 2016, mostly during late 2015 in a fall that was far faster and further than even in the wake of the firm’s 2012 massacre of 34 striking platinum mineworkers at Marikana, South Africa. The value of the Anglo American Corporation (a 1917 joint venture of Ernest Oppenheimer and JP Morgan), which for much of the twentieth century was the largest firm on the continent, shriveled by 93.6 percent from a 2008 peak (3540c per share) to a 2016 low (227c), prompting the company to slash mining employment by more than half and begin selling African assets to the Indian entrepreneur Anil Agarwal of Vedanta. Even the world’s largest commodity trading firm, Glencore (formerly owned by apartheid oil sanctions-buster Marc Rich and then by his protégé, the South African Ivan Glasenburg), fell 86 percent from its 2011 initial London listing price of 532c per share, to a low of 74c.

As shareholders demanded restoration of their wealth, such crisis conditions generated pressure for more intense extraction. In mid-2017, London-based Global Justice Now and several allies released a study by Mark Curtis estimating that forty-eight countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are “collectively net creditors to the rest of the world, to the tune of $41.3 billion in 2015.” According to Curtis: “African countries received $161.6 billion in 2015 — mainly in loans, personal remittances and aid in the form of grants. Yet $203 billion was taken from Africa, either directly — mainly through corporations repatriating profits and by illegally moving money out of the continent — or by costs imposed by the rest of the world through climate change. African countries receive around $19 billion in aid in the form of grants but over three times that much ($68 billion) is taken out in capital flight, mainly by multinational companies deliberately misreporting the value of their imports or exports to reduce tax. While Africans receive $31 billion in personal remittances from overseas, multinational companies operating on the continent repatriate a similar amount ($32 billion) in profits to their home countries each year. African governments received $32.8 billion in loans in 2015 but paid $18 billion in debt interest and principal payments, with the overall level of debt rising rapidly. An estimated $29 billion a year is being stolen from Africa in illegal logging, fishing and the trade in wildlife/plants.”

As Curtis’s figures and the following pages show, regardless of whether Western or BRICS TNCs are to blame, the excessive profits exiting Africa take many forms. Below we consider IFFs, legal financial outflows, FDI flows, foreign indebtedness, South African sub-imperial accumulation, new subsidies used for infrastructure financing, and uncompensated mineral and oil and gas depletion. The continent is further threatened by land grabs, militarization, and climate change. Multilateral management like the Compact With Africa, Bretton Woods loans and United Nations climate finance aren’t helping; only rising social resistance can halt and reverse these trends.

Illicit Financial Flows

First, IFFs reflect many of the corrupt ways that wealth is withdrawn from Africa, mostly in the extractive sector. TNCs employ a myriad of crooked tactics in this regard, including mis-invoicing inputs, transfer pricing and other trading scams, tax avoidance and evasion of royalties, bribery, “round-tripping” investment through tax havens, and outright theft of profits. Examples abound: in South Africa, Sarah Bracking and Khadija Sharife reported that De Beers mis-invoiced $2.83 billion of diamonds over six years. A report by the Alternative Information and Development Centre in Cape Town showed that Lonmin’s platinum operations have spirited hundreds of millions of dollars offshore to Bermuda since 2000. And Vedanta chief executive Agarwal bragged at a Bangalore meeting that in 2006 he had spent $25 million to buy Zambia’s Konkola copper mines, Africa’s largest, and went on to reap at least $500 million profits from it annually, apparently through an accounting scam.

Studies of IFFs by the Washington-based NGO Global Financial Integrity and by economist Leonce Ndikumana and his University of Massachusetts colleagues show how they have helped produce an Africa that is both “more integrated but more marginalized” in world trade. Ndikumana subsequently authored a 2016 UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) critique of extractive industries, and his accounts of South African and Zambian operations provoked angry rebuttals from mining industry representatives who objected to the poor quality of statistics provided by the two country’s governments. While this has required some recalculations, especially in copper and gold exports, the larger truth of these critiques of IFFs remains.

There are also policy-oriented NGOs working against IFF across Africa and the South, including several with northern roots like Trust Africa’s “Stop the Bleeding” campaign, Global Financial Integrity (GFI), Tax Justice Network, Publish What You Pay and Eurodad. (A large share of the credit for making this a major African and world policy matter is due to GFI’s Raymond Baker, a U.S. businessman active in Nigeria before moving to the Brookings Institution where he began advocacy on the issue.) Localization has also occurred through NGOs which demand more accountability, including Trust Africa’s “Stop the Bleeding” campaign. Linking radical and liberal critiques of TNCs and African elites, the new-found visibility of IFFs gives hope to many who want Africa’s scarce revenues to be recirculated inside poor countries, not siphoned away to offshore financial centers. Nevertheless, the head offices of some NGOs remain wedded to the dubious theory that that the bright light of transparency can uncover, disinfect and deter corruption. Their main task is to make capitalism “cleaner,” by bringing problems like IFFs to light.

Consider the case of Tanzanian NGOs, whose neo-colonial outlook was remarked upon by local Marxist scholar Issa Shivji more than a decade ago. In June 2017, Tanzanian President John Magufuli demanded that Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold pay billions of dollars in taxes that had been illegally exported: “We are in an economic war,” he declared. “Billions in revenue have been lost. It’s something that is very painful and shameful for Tanzania.” In response, the NGO network HakiRasilimali—an affiliate of George Soros’ Publish What You Pay (PWYP)—praised Magufuli for standing up, but also warned the government to be mindful of the legal conundrums that could arise from “international legal commitments under [which] the government is bound with guaranteeing companies protection from nationalization and safeguards against retrospective legal applications.” The group further emphasized “the need to continue being an investor friendly country where both the investor and government engage in a win-win situation.”

Such a mindset is not unusual in PWYP circuits. Still, to their credit, many NGOs, allied funders, and grassroots activists have put enough pressure on governments and corporations to compel the African Union and UN Economic Commission on Africa to at least commission an IFF study, led by former South African president Thabo Mbeki. Published in mid-2015, his report used a conservative methodology to estimate that IFFs from Africa exceed $50 billion every year.

This IFF looting originates largely but not entirely in extractive industries. According to an even narrower accounting than Mbeki’s, the African Development Bank and allies’ African Economic Outlook report estimated $319 billion was robbed from 2001–10, with the most theft in metals, totalling $84 billion; oil, $79 billion; natural gas, $34 billion; minerals, $33 billion; petroleum and coal products, $20 billion; crops, $17 billion; food products, $17 billion; machinery, $17 billion; clothing, $14 billion; and iron and steel, $13 billion. These data reaffirm the common charge that Africa is “resource cursed.”

From IFFs to LFFs

Even if IFFs were reduced, FDI would continue to impoverish African countries, in the form of Licit Financial Flows (LFFs). These are legal profits and dividends sent home to TNC headquarters after FDI begins to pay off. The payments of such outflows, along with interest and the net trading position, are termed the “current account.” According to the most recent International Monetary Fund Regional Economic Outlook, the last fifteen years or so have witnessed trade surpluses between Sub-Saharan African nations and the rest of the world reach 5.6 percent of GDP in 2011, followed by smaller net surpluses, and then in 2015-16, deficits of 3.1 and 2.0 percent of GDP, respectively, with more deficits projected by the IMF.

The current account measures not only the balance of imports and exports, but also the flows of profits, dividends, and interest. During the long commodity boom, Sub-Saharan Africa maintained a fair balance, and in 2004–08 even had an average surplus of 2.1 percent of GDP. But since 2011, it has plunged into the danger zone, with a current account deficit of 4.0 percent of GDP in 2016, led by Mozambique (–38 percent) the Republic of the Congo (–29 percent) and Liberia (–25 percent). Including North African countries, the full continent’s current account deficit was 6.5 percent of GDP in 2016, as a result of the fall in oil prices to a low of $26 per barrel in early 2016. Of fifty-four African countries, twenty had double-digit current account deficits in 2016. For context, the 1998 crash of leading East Asian economies was catalyzed by current account deficits of only 5 percent.

To cover a current account deficit, inflows of external finance are required. Such flows to Africa amounted to $178 billion in 2016, which was $5 billion less than 2015, largely as a result of a 60 percent decline in portfolio capital inflows (i.e., purchases of shares in debt or stock market investments, especially in the three major markets of Johannesburg, Cairo, and Lagos). Overseas development aid to Africa declined 2 percent in 2016, and remittances were virtually unchanged. Foreign Direct Investment is somewhat more complicated, however.

FDI in Retreat