Sarahbeth Caplin's Blog, page 44

August 19, 2015

‘Confessions’ reaches bestseller status!

The best things in life aren’t “things,” but when you’re a writer, a screen shot like this is kind of a big deal:

#199 in Kindle free books, #1 in personal growth, #1 in memoirs!

#199 in Kindle free books, #1 in personal growth, #1 in memoirs!

I’ve come a long way since I first started writing books out of construction paper and crayons. Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter was my first self-published book baby to be released into the world, and I was just thrilled that I figured out how to put it out there. It was a real shock that people who don’t even know me actually read the thing.

Thank you to everyone who took the time to invest in my story. Thank you to everyone who downloaded a copy, and special thanks to those who wrote honest reviews. I wouldn’t be where I am today without you. I may not be rich from what I do (hell, I don’t even have a real annual salary), but I get to do what I love, and that gift is priceless (but speaking of prices…the book is free to download through tomorrow before returning to its regular price of $2.99).

Thank you, thank you, a million times thank you. This girl feels mighty blessed.

Filed under: Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, Christianity, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, Judaism, self-publishing, Writing

If he were my son, I’d put the cuffs on him myself

The newest TLC reality show featuring the infamous Duggar family is called “Breaking the Silence,” referring to the recent discovery of molestation committed by Josh, the oldest Duggar child, against his own sisters. The original show that made them famous, 19 Kids and Counting, has been cancelled, but I guess the network just can’t bring itself to part with its biggest cash cow yet. It’s also more than a little ironic that the title “Breaking the Silence” is referring to a family that went out of its way to cover up the abuse, and only issued half-assed not-pologies when they couldn’t hide it any longer.

The newest TLC reality show featuring the infamous Duggar family is called “Breaking the Silence,” referring to the recent discovery of molestation committed by Josh, the oldest Duggar child, against his own sisters. The original show that made them famous, 19 Kids and Counting, has been cancelled, but I guess the network just can’t bring itself to part with its biggest cash cow yet. It’s also more than a little ironic that the title “Breaking the Silence” is referring to a family that went out of its way to cover up the abuse, and only issued half-assed not-pologies when they couldn’t hide it any longer.

I learned something throughout this entire “scandal.” I learned how many people, my own Facebook friends included, know shockingly little about sex abuse. What it is: a crime. And what it isn’t: a “teenage mistake,” an expression that’s been thrown around quite a bit, as if molesting your sibling is on par with breaking a window playing baseball or staying out past curfew. Those are things that normal teenagers do.

But the biggest shock for me was the outrage after I commented (unwisely, I know) on a related article that if Josh Duggar were my son, I would put the handcuffs on him myself.

Is it necessary for me to have children of my own to understand that helping them hide from the consequences of their actions isn’t helping them at all? Why is the future of an outed sex offender more important than the future of a victim who has been shamed into silence? To ask, “What would you do if it were your son?” is the wrong question. If you are outraged at the thought of someone wrongly touching your child, then you know reporting the offender is the right thing to do. Frankly, I’m a little concerned about the number of people who seem to put image above justice. How many people are aware that letting justice be served is a form of love?

I know a family in which the kid caught with drugs was denied bail by his parents, who wanted him to spend a night in jail to fully comprehend the magnitude of his decision. On a lesser scale, I was raised in a home where we lost privileges for breaking the rules no matter how “sorry” we said we were. We were old enough to have rules, and therefore old enough to choose to break them. At fourteen years of age, why do we act like Josh Duggar shouldn’t have known better than to hurt someone?

Love may be tough, but it doesn’t enable.

Filed under: Rape Culture Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, Duggars, evangelicals, Facebook, rape culture

August 17, 2015

A birthday post for a special co-worker

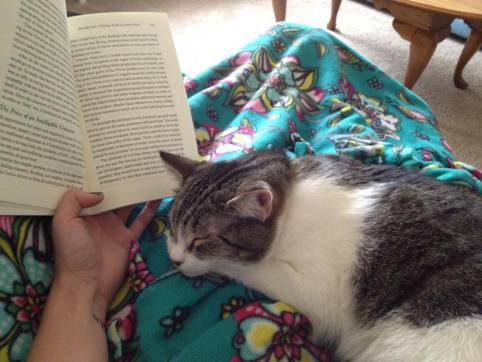

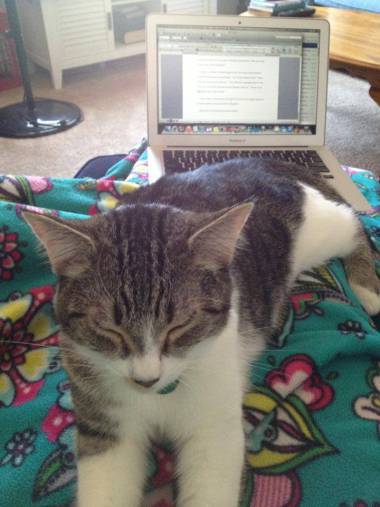

I interrupt my normal flow of serious posts to honor the birth of one of my favorite co-workers.

This little lady has been a huge encouragement to me, always there with an encouraging hug when I need it. In fact, she loves hugs so much, I gave her her own special seat, so she can work closely with me at all times.

And yesterday was her first birthday.

It’s been a privilege getting to know little Zoey over the last eight months. True, she’s not as serious a work-o-holic as I am – at least, not in the same department. Her specialty lies in toilet paper art.

It’s been a privilege getting to know little Zoey over the last eight months. True, she’s not as serious a work-o-holic as I am – at least, not in the same department. Her specialty lies in toilet paper art.

And sleeping in bizarre positions.

And crawling into small spaces.

But most importantly, she loves reading, just like her Mommy Boss.

She’s listening, she’s just…concentrating really hard.

Happy birthday, Zo-Zo girl!

Filed under: Other stuff Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, cats, Writing

August 16, 2015

Can you help your “unbelief”?

“Lord, I believe – help my unbelief!”

I was more than a little surprised when a friend asked if I would consider taking on the role of a “moderator” on his blog about living openly atheist in the Bible Belt. I was his first and only theist moderator, charged with keeping the comment threads civil: not an easy task, given the subject matter of leaving a religion whose culture influences literally every aspect of Southern life. I was chosen for the “job” because I identified myself as a Christian with the sole agenda of learning rather than preaching. Not until discovering Neil’s blog did I give serious consideration to the question of how much control we have in choosing our beliefs.

In our world, beliefs tend to be distinguished from facts. We treat beliefs as individual preferences, but facts as indisputable. You can believe gravity doesn’t exist, but will be proven dangerously wrong by jumping off a building. Facts transcend culture on every level.

Evangelicals, I’ve noticed, have a different definition of “belief.” I’ve read tracts with careful phrasing about “choosing” to believe in Jesus as Lord and Savior. Since words are my livelihood, I spend a great deal of time analyzing them in definition and context, and in evangelical context you can choose to believe or choose to reject. It’s all very simple.

But for many people, the choice to believe is a struggle. If I could easily choose to believe or disbelieve, I wouldn’t struggle with doctrinal ideas like eternal punishment. I struggle to believe because the very idea itself makes little sense to me. Is my thinking brain, my ability to reason, a gift from God or a defect from the Fall? I’ve sat in bible studies with people who believe that asking questions and using logic is playing straight into the hands of the Devil.

With the ability to reason comes the ability to accept or reject an ideology, and the amount of grace I have for people who tried to believe and failed continues to increase as I get older. Christianity asks thinking adults to believe in talking snakes, parting seas, and a dead man coming back to life. Even more uncomfortable is the belief that man has something inherently wrong with him, and he cannot find meaning on his own. I completely understand why, for some people, the choice to believe is as feasible as choosing to believe in the Easter Bunny. It stretches the mind too much.

There is one thing I must choose to believe, no matter how unlikely it seems: I must choose to believe that God’s grace is bigger and deeper than what our human brains are capable of comprehending. I have to believe that God’s love transcends the roadblocks set in place by nature: we know that when people die, they stay dead. We know that watching a newborn sleep soundly makes Original Sin sound ludicrous. We observe and believe what is tangibly visible with evidence. Is it wrong to want a God of the universe to be proven the same way? No one who can see God would consider it a choice to believe; they would simply know.

I envy people who feel they know. And while I choose to believe (for my own sanity) that God has his ways of making himself known to people who wish they were born with a “belief gene,” I strongly empathize with those who just couldn’t do it. I’ve been there; some days I still am. I believe those who say they were devout believers for many years, but are not anymore. Let no one try and dictate your story for you when they haven’t lived it.

Excerpted from my upcoming book, Add Jesus and Stir: a Jewish-born Christian’s attempt to understand evangelical culture.

Filed under: Religion, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, Campus Crusade for Christ, Christian culture, Christianity, evangelicals, Writing

August 15, 2015

A word about my next book, ‘Add Jesus and Stir’

Surprise, surprise, I’m working on another book. Because of the unexpected success of my first memoir, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, which ranked #51 in Amazon’s top 100 paid books on personal growth this summer (for six days!), I think now is the best time to write a second one.

Surprise, surprise, I’m working on another book. Because of the unexpected success of my first memoir, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, which ranked #51 in Amazon’s top 100 paid books on personal growth this summer (for six days!), I think now is the best time to write a second one.

I didn’t expect to be a nonfiction author, particularly a nonfiction religious author, but writing about religion is when I am most honest, most authentic, and I would not have nearly the same number of blog and Twitter followers as I do if not for all my questions. Some of my favorite religious writers are people who dare to ask the questions I’m afraid to acknowledge even in my own head. I like to imagine that that’s how many readers of this blog and of Confessions feel.

But a second memoir was inevitable, regardless of how well the first one did. It was inevitable not because I’ve lived such a unique life, but because the questions keep on growing, and they are hard to find addressed in mainstream Christian books. There are plenty of stories out there about finding God, but not so much what to do when no one in church can answer your questions, and when those questions threaten to break your faith. There are few books out there that address doubt but don’t end neatly, and for converts like myself, who still carry some baggage from the faith of their childhood, that pool of books has even fewer options.

Add Jesus and Stir: a Jewish-born Christian’s attempt at understanding evangelical culture is my response to Christians who claim to love Judaism, but don’t really understand what it’s about. It’s also a book for anyone, not just converted Jews, who embraced a new tradition as an adult, but cannot for the life of them fit in with the surrounding cultural norms. My story of wading through evangelical waters has been, and continues to be, a fish out of water experience. In Evangelical World I have met some truly amazing people, but have also experienced a lot of damage, which my Jewish background made me particularly prone to.

This is a book about questioning all the beautiful parts – an incarnate god, the promise of redemption – because of the ugly: when not enjoying worship music is sinful, and your non-believing relatives are assumed destined for hell.

What is one to do with a dichotomy like that – especially coming from a religious tradition that affirms more than one viable path to God?

Add Jesus and Stir doesn’t offer any answers, but it has been therapeutic for me to write (100 pages and 22,000 words so far, some of which have been test-driven on this blog). I have a love-hate relationship with my unusual testimony, but I don’t think it’s so “out there” that no cradle Christian can possibly relate. I come from a tradition that is known for asking questions, and I want this book to be encouraging for Christians bred with the idea that doubt is not okay.

Much has changed since the first edition of Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter was published. The honeymoon phase of my new relationship with Jesus has long faded. Restlessness has moved in. Frustration and irreconcilable differences are daily battles.

At the time I started writing that first draft, I was an opinion columnist for my college newspaper. I wanted the job because I was tired of the pervasive liberal attitude of seemingly every editorial. It didn’t take long to develop a reputation as “that Christian columnist,” and the title was not always used favorably. I can see now that my tone was obnoxious in many columns, writing as someone who thought she found indisputable Truth. But the biggest mistake I made as a columnist was adopting the assumption that I was disliked by so many because I happened to be Christian, which could not have been further from the truth. As a Jew raised in a small, conservative Christian town, shouldn’t I have known better than to play the persecution card? Why would I have done that?

I know why, though I wouldn’t have admitted it then. It’s very much a cultural trend to take on a persecution complex, no matter how outrageous it sounds compared to Christians across the world who are losing their lives for their faith. I just wanted to be included more than anything. I wanted to know what being part of the religious in-crowd felt like. If that meant pretending that the Christian majority I recognized so clearly growing up was actually in danger of extinction, so be it.

Thankfully, the mindset didn’t last. I could only pretend for so long that being the odd Jew out (an actual minority) for most of my life wouldn’t catch up to me at some point. Sure enough, during my stint at seminary, it did.

Add Jesus and Stir is the story of what happened to my faith when I confronted my inner Jew, who was buried for a time, but never actually went away. Perhaps she was never meant to.

Filed under: Religion, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, Campus Crusade for Christ, Christian culture, Christianity, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, Controversy, evangelicals, Judaism, self-publishing, Writing

August 10, 2015

Thinking outside the tampon box

A woman runs a marathon during her period, without a tampon, and it’s all that Twitter is talking about (this hour, anyway). I had never heard of “period shaming,” but then again, I live in a society where no one cares if I sit down on a public bench whilst “unclean.” For many women around the world, there is a real stigma.

A woman runs a marathon during her period, without a tampon, and it’s all that Twitter is talking about (this hour, anyway). I had never heard of “period shaming,” but then again, I live in a society where no one cares if I sit down on a public bench whilst “unclean.” For many women around the world, there is a real stigma.

Still, I’m not entirely convinced that running with blood covering your crotch is really the best way to draw the kind of attention you want. I’m torn between thinking, “Wow, she’s got lady-balls,” and “Damn, that’s disgusting.”

Maybe I don’t think outside the [tampon] box enough, but can you really convince people to see your point when violating basic rules of hygiene?

Well, people are talking about it, so I guess her point has been made. Still, I can’t help but get the feeling that the new goal of awareness is to create as much shock value as possible, even though it’s worked in the past: the Holocaust museum in Washington, DC uses graphic footage not just to show history as it happened, but also because there are still people out there who believe it never happened. I have friends who post disturbing photos of slaughtered pigs and post-abortion fetuses on Facebook to get their messages across, but even if the message is one I agree with, at what point does shock value push away more people than it actually educates?

In a world that craves “big” stories, the need to go drastic is understandable, and I’ve certainly felt that burning need to have people LOOK AT ME, because I HAVE SOMETHING I NEED TO SAY. I’d just be afraid that saying something with menstrual blood soaking my pants might cause more people to stare rather than actually listen.

Do these shock-value methods for awareness really work? Better question: what are you willing to do to get people to pay attention?

Filed under: Feminism, Other stuff Tagged: Abortion, censorship, Controversy, Feminism, social justice

August 8, 2015

Permission to be myself

A common flaw in Christian and Jewish culture I can’t seem to escape from is the debate about who “qualifies” as a Christian or a Jew. To be fair, the “Who is a Jew” question is prioritized more among conservative groups than liberal ones, especially when applications for Israeli citizenship are concerned. Still, the idea that one’s identity can be scrutinized by people not familiar with the intricacies of the journey behind it is troubling.

A common flaw in Christian and Jewish culture I can’t seem to escape from is the debate about who “qualifies” as a Christian or a Jew. To be fair, the “Who is a Jew” question is prioritized more among conservative groups than liberal ones, especially when applications for Israeli citizenship are concerned. Still, the idea that one’s identity can be scrutinized by people not familiar with the intricacies of the journey behind it is troubling.

Sometimes definitions can be obvious. Who is a Democrat or a Republican? Someone registered to vote as a Democrat or Republican (technically speaking). Who is a vegetarian? A person who abstains from meat. But what if you consume meat only once a week? Once a year? Are you no longer a vegetarian?

What if you’re a Christian who curses? What if you’re a Jew who was born from a Jewish mother, but believes Jesus is the Messiah? Or believes in no god(s) at all?

I was wearing that teardrop star pendant when I went to get my glasses adjusted. I thought I had reached a place of contentedness about it: it represented my heritage, and I was comfortable wearing it for that purpose. But as she cleaned off my lenses, the woman behind the counter at LensCrafters said, “I like your necklace. I’m Jewish, too.”

All I said in response was “Thanks.” I wondered if I should say more, explain myself, because leaving that comment alone made me feel like I was lying to her. I left the store thinking, Lady, if you knew the truth, you’d probably hate me.

Why do I do this? Why do I continue making decisions based on how I will appear to other people? Why do I constantly seek to validate myself in others’ eyes? What would have happened if I explained my reasons to that perfect stranger, as if I were seeking her permission: Do you think this is okay? It’s not offensive because I really do have Jewish heritage, right?

Oh, enough already. This is a miserable trajectory I am on, constantly molding myself to others’ expectations so I can be accepted. Religion has become like high school again: I’m finding myself studying the ways of the kids I perceive as cool so I know what I can and cannot say. What I can and cannot admit to.

I am reaching a point of exhaustion, and I have no other choice: screw it, I’m just going to be myself.

I’ll encounter Jews who will deny my Judaism, regardless of how I was raised. I’ll meet Christians who might judge me if a curse word slips out of my mouth. I will run into legalism in many forms, wearing all kinds of masks, and will learn to not feel threatened by it. Rejection has added a layer of toughness on my skin, thick as grime, and just as difficult to scrub away.

Filed under: Religion Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, evangelicals, Judaism

August 6, 2015

“It’s Complicated”

While Judaism made me aware that everyone suffers, and Christianity taught me how to persevere through suffering, most of the time I really don’t suffer – I’m just uncomfortable. And the things that cause this discomfort are really kind of silly. When there’s grime in the shower again, and I can’t enjoy my book knowing that it’s there, both faiths remind me that at least I have a place to live. When I find myself sitting next to someone I don’t like, both faiths help remind me of his or her inherent value (I wish I could say this drastically changes my attitude, but at least I’m reminded of it).

While Judaism made me aware that everyone suffers, and Christianity taught me how to persevere through suffering, most of the time I really don’t suffer – I’m just uncomfortable. And the things that cause this discomfort are really kind of silly. When there’s grime in the shower again, and I can’t enjoy my book knowing that it’s there, both faiths remind me that at least I have a place to live. When I find myself sitting next to someone I don’t like, both faiths help remind me of his or her inherent value (I wish I could say this drastically changes my attitude, but at least I’m reminded of it).

The reality is, no religion will ever make complete sense to me and not have parts that I either don’t understand or feel greatly disturbed by. I have greater appreciation now for the ritual prayers of Judaism, but most of them being in Hebrew makes it difficult to reflect on their meaning, and reciting them in English just doesn’t have the same rhythm.

The closest ritual system I’ve found in Christianity is that of the Catholic Church (it even operates by a lunar calendar!), using rosary beads as focal points much like Jews use teffillim, and the prescribed prayers in English are much easier to understand. But I don’t think I could ever call myself Catholic because I don’t know how much I can untangle the beauty of Catholic tradition from the Vatican politics. I don’t believe the pope is infallible. Not to mention that I use birth control and am leaning towards not having children, both of which are frowned upon.

I’m not sure if viewing the Bible as inerrant is mostly an evangelical thing, but it doesn’t seem very popular to question it. What exactly do people mean when they call the Bible “perfect”? Is it grammatically perfect? How do they not feel the same stomach-churning that I do when reading the parts about genocide ordered by God, and laws about rape victims being forced to marry their assailants? Why are those things included if they contradict the morality that most people, religious and non-religious alike, condemn as evil? How hard would it have been for God to add an eleventh commandment, “Men, don’t rape or hit women. This is detestable”?

Actually, I wish that God had thought to add a few more commandments: “Treat homosexuals like human beings.” “Don’t bomb abortion clinics.” “Don’t try to turn America into a theocracy.” “Don’t tell your congregants how to vote.” “Don’t cry ‘persecution’ because someone disagreed with you.” “Never use an evangelism tract in place of a tip.”

I know, I know. If I’m so smart, why don’t I be God? And if religion causes me so many problems, why not abandon it altogether?

Believe me, I’ve considered that last possibility. But religion speaks to my desire to be part of something bigger than myself. It speaks to that part of me that believes we are more than just accidents of nature. I’ve always believed there was some kind of higher being out there, and religion is the tool to try and know him, as opposed to making up my own ideas about him. There’s a great deal of ugliness in religious history, to be sure. But there are stories of great glory, too, as well as the smaller, private moments of clarity that won’t convince skeptics en masse, but are enough to convince me.

People we love may be hard to understand at times, and have aspects of their personalities that bug the crap out of us. Honestly, I think the same of God.

Filed under: Religion Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Judaism, rape culture

August 4, 2015

Evangelicals and the surrender of privacy

I have a tendency to pull away from people during times of stress. Sometimes this is a necessary thing to do, but it was completely forbidden in my experience with Evangelical World.

During a summer retreat in Estes Park, Colorado with my college church, I fell in love with the idea of complete authenticity. How annoying is it to give the colloquial response “I’m fine” to store clerks who ask how you’re doing, even when you’re not? No one actually admits the truth. We all know that “How are you?” is really more of a greeting than a sincere inquiry.

Everyone was transparent that summer. You could walk up to a stranger at lunch, sit down next to them, and immediately learn everything you never thought you’d want to know about what that person’s life is like. A single conversation could include stories of painful divorces, struggles with internet porn, and drug use without ever learning anyone’s last name. Yes, at times this was extremely intimidating, but in a way, it was also refreshing. Without any pretenses or masks, you knew exactly whom you could trust.

I resolved to be completely authentic after that summer: no more “I’m great, how are you?” platitudes if I wasn’t feeling that great. Wasn’t it a sin to lie, anyway?

That authenticity phase didn’t last a week beyond the retreat. I returned home, got a job at a local restaurant, saw my rapist’s mother walk in and immediately had a panic attack. I started counseling, anti-depressants, and really dealing with un-faced trauma. I started drinking. Complete authenticity? Yeah, screw that.

But there were some bible studies and prayer groups I joined where privacy wasn’t a choice; or at least, it was highly frowned upon. The idea of being open among strangers is terrifying for many people, even without a history of trauma. Just being introverted makes me uncomfortable having to speak in front of crowds if it’s not necessary. I prefer the option of quiet listening and one-on-one conversations. When you are the only one in a small group who hasn’t said anything, though, your lack of participation is obvious. For me, it was not viewed as silent participation, but rebellion. We were Christians; we were a community. That community was automatic because we all loved Jesus, and as such, we had to be open and honest with one another so we could hold each other accountable for any sins.

Per small group instructions, I tried explaining some of my issues once to someone with zero concept of depression and anxiety as legitimate mental disorders. It didn’t go very well. In fact, it scared me out of opening up to people I don’t know ever again, because until I use my own judgment to determine whether or not a person is “safe,” I will be making myself vulnerable to getting hurt. That’s how many churches end up with an increase of empty seats. You can’t force community any more than you can ask someone to do you a favor in such a way that is really volun-telling instead of volunteering.

There is one instance I can think of in which being completely authentic among strangers was one of the best things that happened to me, only it wasn’t me who opened up: it was my future best friend, Kelly. On the first day of Intro to Counseling at seminary, there was a student who made a remark that depression was nothing more than a label used to justify sin. To add further insult to such a horrendous injury, the woman also added that “true Christians” wouldn’t face depression if they had true joy and contentment in Christ.

It was Kelly who immediately stood up and responded, “I’m a Christian, and I have depression. I’ve felt Jesus going through it with me. You can’t tell me that my relationship with him isn’t real.”

I had never been so proud of someone I didn’t know. Immediately after class, I went up to her and introduced myself. She is one of the few people from that toxic environment that I still keep in touch with, though I do wish I hadn’t had to pay $30,000 to be able to meet her. But, “there is a season for everything under the sun,” including an unfinished graduate degree. And through her I have learned that it’s okay to be have faith and still wrestle with doubt; she is one of my favorite sounding boards to share those doubts with.

Now that is community done well.

Filed under: Religion Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, depression, evangelicals, grief

Another Form of Interfaith: A Christian From a Jewish Family

Guest blogging with Susan Katz Miller today, author of “Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family.”

Originally posted on On Being Both:

Originally posted on On Being Both:

Jewish identities are diverse. Christian identities are diverse. And, interfaith identities are diverse. I often write about the idea that every child, no matter which religious label and education parents give them, grows up to choose their own beliefs, practices and affiliations. Today, guest blogger Sarahbeth Caplin recounts her journey, from a Jewish childhood to her conversion to evangelical Christianity, and her sense of being interfaith.–SKM

No one, not even myself, can figure out where my fascination with religion came from: I wasn’t raised in a religious family, and I certainly wasn’t raised within any Christian tradition. I don’t know what my Jewish parents thought about my early fascination with saints and martyrdom; surely it wasn’t normal, at an age when most girls I knew were into reading The Babysitter’s Club and Boxcar Children series. As an adult, it’s clear to me that God had a firm grip on my…

View original 709 more words

Filed under: Other stuff