Craig Pirrong's Blog, page 83

April 7, 2017

Trump, Putin, and the Tomahawk Chop

President Trump ordered a cruise missile strike on a Syrian air base that was allegedly the launching point of a sarin attack on a town in the Idlib Governate. My initial take is like Tim Newman’s: although the inhumanity in Syria beggars description, getting involved there is foolish and will not end well.

The Syrian conflict is terrible, but Syria makes the snake pit in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom look hospitable.

Further, the politics of Syria (both internally, and in the region) make the intrigues of Game of Thrones seem like child’s play by comparison. So I agree with Tim:

Every course of action I can think of other than “fuck ’em” has an almost zero chance of succeeding in its aims and a very high chance of making things worse.

. . . .

It’s not through moral principle that I am saying this, it is from practicality based on fourteen years of recent, bloody experience: Assad is a monster, the Russian government is showing the world exactly what they are like by backing him, and the Syrian people are suffering terribly, but there is nothing – nothing – we can do about it. It is a terrible indictment on the state of the world, but a policy of “fuck the lot of ’em” is the only workable one on the table right now. It’s high time our leaders started taking it seriously.

To put it slightly differently. Good intentions mean nothing. Results and consequences do. I am at a loss to think of any policy with results and consequences that accord with good intentions. Indeed, it almost inevitable that any major military intervention would not save Syrian lives but would cost American ones.

Truth be told, given the devastation wreaked on children, women, and men in Syria by bombs, shells, small arms and even throat-slashing blades, chemical weapons do not represent a quantum shift in the horribleness of the Syrian war. Dead is dead, and periodic use of chemical weapons does not materially affect the amount of dying that is going on. Assad–and the Islamists he is fighting–have killed and maimed far more innocent civilians with conventional weapons than with chemical ones. The use of chemical weapons does not represent a fundamental shift in the nature of the war, which was already a total war waged without restraint against civilians by all sides (would that there were only two sides in Syria).

Insofar as Trump’s action is concerned, it is best characterized as a punitive strike. And as punitive strikes go, it is modest. It bears more similarity to Clinton strikes in Iraq (e.g., Desert Fox) than Reagan’s Operation El Dorado Canyon in 1986, which put the fear of god into Gaddafi: a 2000 pound bomb dropped near one’s tent has a tendency to do that. In contrast, Thursday’s Tomahawk detonations wouldn’t have disturbed Assad’s sleep in the slightest, let alone put him in mortal danger.

The record of such punitive actions in curbing the misbehavior of bad actors like Saddam or even Gaddafi is hardly encouraging, but at least the downside (to the US) of such indulgences of the Jupiter Complex is rather limited. The concern is that the raid turns out to be ineffectual in moderating Assad’s behavior and leads to Trump to escalate, and to make regime change–rather than a change of regime behavior–the objective. The neocons are celebrating and baying for more: that should be a cause for serious concern.

And I don’t think that this was exclusively about Syria, or even primarily so. The Tomahawks might have landed in Syria, but in a very real sense they were aimed at North Korea. It is significant that Trump launched the attack while Chinese premier Xi was still digesting the steak he had eaten with the president.

Russia is clearly processing the message. The Russians are obviously angered. One would think that this puts paid to the Trump is Putin’s bitch narrative. But that would assume sanity on the part of the left and the Never Trumpers, who are anything but sane.

The prospects for some rapprochement between the US and Russia were already on life support, now they appear to be dead and buried. This reinforces a point I’ve made for months: that if Putin really did think that a Trump presidency would be better for him than a Clinton one, he made a grave miscalculation. This event proves that Trump is predictably unpredictable, and that he is completely capable of a volte face at a moment’s notice. The word I used was “protean”, and the decision to fire off a barrage of cruise missiles after months-years, in fact-of criticizing the idea of American intervention in Syria is about as protean as you get.

This points to a broader message. For all his alleged tactical acumen, Putin has stumbled from one strategic blunder to another. It is highly unlikely that Russian involvement, whatever it was, materially impacted the US election: its impact has been exaggerated for purely partisan and psychological reasons. It is also highly unlikely that any Russian meddling in European elections will sway them in favor of pro-Putin candidates.

But Russia has paid a steep price for these equivocal gains: Russian actions have created political firestorms not just in the US but in Europe that have actually increased Russian isolation. Hysteria in America about Russian meddling in US politics is vastly overblown, and has been ginned up for partisan reasons, but that is irrelevant as a practical matter: it has made the US-Russia relationship more adversarial than it has been since the height of the Cold War, and that works to Russia’s detriment.

His support for Assad in Syria has had similar effects. Yes, Putin achieved his immediate objective: Assad has survived, and looks likely to prevail. But Russia has only cemented its pariah status. The chemical attack makes it even more than a pariah. For what? Syria’s strategic value is minimal.

Indeed, the chemical attack is not just a crime, but a blunder, and puts Putin and Russia in an even worse spot. The action appears so militarily unnecessary and politically counterproductive that like Scott Adams, it raises doubts in my mind as to whether Assad actually ordered it. (The alternative explanations include a rogue general or a false flag carried out by the opposition.) But this is largely irrelevant: Assad is almost universally blamed, and as his stalwart defender, Putin and Russia have been deemed guilty of being accessories to and enablers of what is just as universally considered a war crime. By going all in for Assad, Putin made himself vulnerable to this. (That might provide a Machiavellian motive for Assad’s action: maybe he thought that the chemical attack would bind Putin even more closely to him.)

So by intervening in Syria, and defending Assad even in the aftermath of a widely reviled chemical attack, what has Putin gained? Yes, he had the satisfaction of showing Obama (and in his mind, the US as a whole) to be feckless, all grandiose talk and no action. He could claim to have reversed Russia’s retreat from the Middle East. He could assert that Russia is back and must be reckoned with in world affairs. He apparently experienced great personal satisfaction as a result of these accomplishments.

But viewed more soberly, these gains are more than offset by losses on the other side of the ledger. Russia is isolated, distrusted, feared, and reviled. It’s not entirely fair, but it should have been predictable. Moreover, nothing that Putin has done has improved what the Soviets called the correlation of forces. Indeed, although Russia has rejuvenated its military to some degree, other elements of national power (relative to the US) have slipped since 2008, and a Trump presidency will almost certainly erase the relative change in military power that occurred during Russian rearmament and the American sequester.

The simple fact is that other than in nuclear weapons, Russia cannot compete with the US, let alone the entire west. By achieving limited victories in strategic backwaters like Syria, all Putin has succeeded in doing is goading the US and the west into viewing him as a threat and sparking a competition that he can’t win.

But Putin has staked a great deal on Syria, in terms of both national and personal prestige. He is not the kind of man to back down and lose face after putting down such a stake. For his part, after claiming benign indifference to who rules Syria, the protean Trump has reversed course, and in so doing has put his own reputation on the line over who rules there, or at least how the man who rules there behaves. That is a combustible mix, and I have no idea how it will turn out.

But I am sure of how things will not turn out. Sore election losers’ dystopian fantasy of Trump selling out to Putin will never become reality. In fact, the reverse is more likely. Indeed, this could develop into a reversal of Reagan-Gorbachev. Then, two bitter antagonists found enough common ground to come to an understanding and ratchet down Cold War tensions. Now, two alleged members of a mutual admiration society are likely to find themselves in an increasingly antagonistic relationship, in yet further proof of my axiom that if you want to find the truth, you could do far worse than to invert elite conventional wisdom.

April 4, 2017

The Unintended Consequences of Blockchain Are Not Unpredictable: Respond Now Rather Than Repent Later*

In the past week the WSJ and the FT have run articles about a new bank-led initiative to move commodity trading onto a blockchain. In many ways, this makes great sense. By its nature, the process of recording and trading commodity trades and shipments is (a) collectively involve large numbers of spatially dispersed counterparties, (b) have myriad terms, and (c) can give rise to costly disputes. As a result of these factors, the process is currently very labor intensive, fraught with operational risk (e.g., inadvertent errors) and vulnerable to fraud (cf., the Qingdao metals warehouse scandal of 2014). In theory, blockchain has the ability to reduce costs, errors, and fraud. Thus, it is understandable that traders and banks are quite keen on the potential of blockchain to reduce costs and perhaps even revolutionize the trading business.

But before you get too excited, a remark by my friend Christophe Salmon at Trafigura is latent with deep implications that should lead you to take pause and consider the likely consequences of widespread adoption of blockchain:

Christophe Salmon, Trafigura’s chief financial officer, said there would need to be widespread adoption by major oil traders and refiners to make blockchain in commodity trading viable in the long term.

This seemingly commonsense and innocuous remark is actually laden with implications of unintended consequences that should be recognized and considered now, before the blockchain train gets too far down the track.

In essence, Christophe’s remark means that to be viable blockchain has to scale. If it doesn’t scale, it won’t reduce cost. But if it does scale, a blockchain for a particular application is likely to be a natural monopoly, or at most a natural duopoly. (Issues of scope economies are also potentially relevant, but I’ll defer discussion of that for now.)

Indeed, if there are no technical impediments to scaling (which in itself is an open question–note the block size debate in Bitcoin), the “widespread adoption” feature that Christophe identifies as essential means that network effects create scale economies that are likely to result in the dominance of a single platform. Traders will want to record their business on the blockchain that their counterparties use. Since many trade with many, this creates a centripetal force that will tend to draw everyone to a single blockchain.

I can hear you say: “Well, if there is a public blockchain, that happens automatically because everyone has access to it.” But the nature of public blockchain means that it faces extreme obstacles that make it wildly impractical for commercial adoption on the scale being considered not just in commodity markets, but in virtually every aspect of the financial markets. Commercial blockchains will be centrally governed, limited access, private systems rather than a radically decentralized, open access, commons.

The “forking problem” alone is a difficulty. As demonstrated by Bitcoin in 2013 and Ethereum in 2016, public blockchains based on open source are vulnerable to “forking,” whereby uncoordinated changes in the software (inevitable in an open source system that lacks central governance and coordination) result in the simultaneous existence of multiple, parallel blockchains. Such forking would destroy the network economy/scale effects that make the idea of a single database attractive to commercial participants.

Prevention of forking requires central governance to coordinate changes in the code–something that offends the anarcho-libertarian spirits who view blockchain as a totally decentralized mechanism.

Other aspects of the pure version of an open, public blockchain make it inappropriate for most financial and commercial applications. For instance, public blockchain is touted because it does not require trust in the reputation of large entities such as clearing networks or exchanges. But the ability to operate without trust does not come for free.

Trust and reputation are indeed costly: as Becker and Stigler first noted decades ago, and others have formalized since, reputation is a bonding mechanism that requires the trusted entity to incur sunk costs that would be lost if it violates trust. (Alternatively, the trusted entity has to have market power–which is costly–that generates a stream of rents that is lost when trust is violated. That is, to secure trust prices have to be higher and output lower than would be necessary in a zero transactions cost world.)

But public blockchains have not been able to eliminate trust without cost. In Bitcoin, trust is replaced with “proof of work.” Well, work means cost. The blockchain mining industry consumes vast amounts of electricity and computing power in order to prove work. It is highly likely that the cost of creating trusted entities is lower than the cost of proof of work or alternative ways of eliminating the need for trust. Thus, a (natural monopoly) commercial blockchain is likely to have to be a trusted centralized institution, rather than a decentralized anarchist’s wet-dream.

Blockchain is also touted as permitting “smart contracts,” which automatically execute certain actions when certain pre-defined (and coded) contingencies are met. But “smart contracts” is not a synonym for “complete contracts,” i.e., contracts where every possible contingency is anticipated, and each party’s actions under each contingency is specified. Thus, even with smart (but incomplete) contracts, there will inevitably arise unanticipated contingencies.

Parties will have to negotiate what to do under these contingencies. Given that this will usually be a bilateral bargaining situation under asymmetric information, the bargaining will be costly and sometimes negotiations will break down. Moreover, under some contingencies the smart contracts will automatically execute actions that the parties do not expect and would like to change: here, self-execution prevents such contractual revisions, or at least makes them very difficult.

Indeed, it may be the execution of the contractual feature that first makes the parties aware that something has gone horribly wrong. Here another touted feature of pure blockchain–immutability–can become a problem. The revelation of information ex post may lead market participants to desire to change the terms of their contract. Can’t do that if the contracts are immutable.

Paper and ink contracts are inherently incomplete too, and this is why there are centralized mechanisms to address incompleteness. These include courts, but also, historically, bodies like stock or commodity exchanges, or merchants’ associations (in diamonds, for instance) have helped adjudicate disputes and to re-do deals that turn out to be inefficient ex post. The existence of institutions to facilitate the efficient adaption of parties to contractual incompleteness demonstrates that in the real world, man does not live (or transact) by contract alone.

Thus, the benefits of a mechanism for adjudicating and responding to contractual incompleteness create another reason for a centralized authority for blockchain, even–or especially–blockchains with smart contracts.

Further, the blockchain (especially with smart contracts) will be a complex interconnected system, in the technical sense of the term. There will be myriad possible interactions between individual transactions recorded on the system, and these interactions can lead to highly undesirable, and entirely unpredictable, outcomes. A centralized authority can greatly facilitate the response to such crises. (Indeed, years ago I posited this as one of the reasons for integration of exchanges and clearinghouses.)

And the connections are not only within a particular blockchain. There will be connections between blockchains, and between a blockchain and other parts of the financial system. Consider for example smart contracts that in a particular contingency dictate large cash flows (e.g., margin calls) from one group of participants to another. This will lead to a liquidity shock that will affect banks, funding markets, and liquidity supply mechanisms more broadly. Since the shock can be destabilizing and lead to actions that are individually rational but systemically destructive if uncoordinated, central coordination can improve efficiency and reduce the likelihood of a systemic crisis. That’s not possible with a radically decentralized blockchain.

I could go on, but you get the point: there are several compelling reasons for centralized governance of a commercial blockchain like that envisioned for commodity trading. Indeed, many of the features that attract blockchain devotees are bugs–and extremely nasty ones–in commercial applications, especially if adopted at large scale as is being contemplated. As one individual who works on commercializing blockchain told me: “Commercial applications of blockchain will strip out all of the features that the anarchists love about it.”

So step back for a minute. Christophe’s point about “widespread adoption” and an understanding of the network economies inherent in the financial and commercial applications of blockchain means that it is likely to be a natural monopoly in a particular application (e.g., physical oil trading) and likely across applications due to economies of scope (which plausibly exist because major market participants will transact in multiple segments, and because of the ability to use common coding across different applications, to name just two factors). Second, a totally decentralized, open access, public blockchain has numerous disadvantages in large-scale commercial applications: central governance creates value.

Therefore, commercial blockchains will be “permissioned” in the lingo of the business. That is, unlike public blockchain, entry will be limited to privileged members and their customers. Moreover, the privileged members will govern and control the centralized entity. It will be a private club, not a public commons. (And note that even the Bitcoin blockchain is not ungoverned. Everyone is equal, but the big miners–and there are now a relatively small number of big miners–are more equal than others. The Iron Law of Oligarchy applies in blockchain too.)

Now add another factor: the natural monopoly blockchain will likely not be contestible, for reasons very similar to the ones I have written about for years to demonstrate why futures and equity exchanges are typically natural monopolies that earn large rents because they are largely immune from competitive entry. Once a particular blockchain gets critical mass, there will be the lock-in problem from hell: a coordinated movement of a large set of users from the incumbent to a competitor will be necessary for the entrant to achieve the scale necessary to compete. This is difficult, if not impossible to arrange. Three Finger Brown could count the number of times that has happened in futures trading on his bad hand.

Now do you understand why banks are so keen on the blockchain? Yes, they couch it in terms of improving transactional efficiency, and it does that. But it also presents the opportunity to create monopoly financial market infrastructures that are immune from competitive entry. The past 50 years have seen an erosion of bank dominance–“disintermediation”–that has also eroded their rents. Blockchain gives the empire a chance to strike back. A coalition of banks (and note that most blockchain initiatives are driven by a bank-led cooperative, sometimes in partnership with a technology provider or providers) can form a blockchain for a particular application or applications, exploit the centripetal force arising from network effects, and gain a natural monopoly largely immune from competitive entry. Great work if you can get it. And believe me, the banks are trying. Very hard.

Left to develop on its own, therefore, the blockchain ecosystem will evolve to look like the exchange ecosystem of the 19th or early-20th centuries. Monopoly coalitions of intermediaries–“clubs” or “cartels”–offering transactional services, with member governance, and with the members reaping economic rents.

Right now regulators are focused on the technology, and (like many others) seem to be smitten with the potential of the technology to reduce certain costs and risks. They really need to look ahead and consider the market structure implications of that technology. Just as the natural monopoly nature of exchanges eventually led to intense disputes over the distribution of the benefits that they created, which in turn led to regulation (after bitter political battles), the fundamental economics of blockchain are likely to result in similar conflicts.

The law and regulation of blockchain is likely to be complicated and controversial precisely because natural monopoly regulation is inherently complicated and controversial. The yin and yang of financial infrastructure in particular is that the technology likely makes monopoly efficient, but also creates the potential for the exercise of market power (and, I might add, the exercise of political power to support and sustain market power, and to influence the distribution of rents that result from that market power). Better to think about those things now when things are still developing, than when the monopolies are developed, operating, and entrenched–and can influence the political and regulatory process, as monopolies are wont to do.

The digital economy is driven by network effects: think Google, Facebook, Amazon, and even Twitter. In addition to creating new efficiencies, these dominant platforms create serious challenges for competition, as scholars like Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice Stucke have shown:

Peter Thiel, the successful venture capitalist, famously noted that ‘Competition Is for Losers.’ That useful phrase captures the essence of many technology markets. Markets in which the winner of the competitive process is able to cement its position and protect it. Using data-driven network effects, it can undermine new entry attempts. Using deep pockets and the nowcasting radar, the dominant firm can purchase disruptive innovators.

Our new economy enables the winners to capture much more of the welfare. They are able to affect downstream competition as well as upstream providers. Often, they can do so with limited resistance from governmental agencies, as power in the online economy is not always easily captured using traditional competition analysis. Digital personal assistants, as we explore, have the potential to strengthen the winner’s gatekeeper power.

Blockchain will do the exact same thing.

You’ve been warned.

*My understanding of these issues has benefited greatly from many conversations over the past year with Izabella Kaminska, who saw through the hype well before pretty much anyone. Any errors herein are of course mine.

Big Brother Revealed!

Some 200 theaters around the world are screening 1984 to warn about the dark descending night of fascism under Donald Trump. The timing of this could not be more ironic, given that all the news of late makes it abundantly clear that the former administration, not the current one, deserves to be known as Big Brother.

In particular, after a steady trickle of news about surveillance and unmasking of Trump campaign and transition personnel by the US intelligence community, yesterday the story broke that ex-National Security Advisor and noted f-bomber* Susan Rice–yes, that paragon of honesty, Madam Benghazi Talking Points–had requested the unmasking of numerous Trump personnel picked up in reports of surveillance on foreigners (incidentally, of course! Trust them on this!).

Last month, Ms. Rice played dumb (not a stretch!) by claiming that she had no idea what Devin Nunes was on about. Yesterday, Susie F was unavailable for comment, although one of the Obama creatures working for CNN (but I repeat myself) tweeted: “Just in: ‘The idea that Ambassador Rice improperly sought the identities of Americans is false.’ – person close to Rice tells me.”

Note the presence of the weasel modifier “improperly.” Not a categorical denial of unmasking. I therefore consider this an admission that unmasking did occur.

Within minutes of Rice’s unmasking, the left and the egregious never Trumpers (led by Jennifer Rubin, David Frum, and Evan McMuffin), had their narrative response ready to go: It’s a good thing that Rice was keeping tabs on the evil Trump’s canoodling with the Russkies! Just doing her job and saving the Republic!

Which overlooks one crucial detail: Nunes claims that the unmasked communications he saw had nothing to do with Russia. And let’s get real here. It is almost certain that Nunes saw a sample of what the White House has learned. NSC staffer Evan Cohen-Watnick (who played a role in discovering the information, though his exact part is hazy, like most details in this story) was apparently told to stop collecting material by the White House counsel’s office. Presumably they have continued the effort given its political and legal sensitivities. We know that US intelligence systematically collects intelligence on foreigners, meaning that any contacts by the Trump campaign and the Trump administration with anyone in countries ranging from Albania to Zanzibar would have been collected (incidentally! pinkie swear!) and available for unmasking. If Rice was asking for material on contacts with one non-Russian country, it is likely she was asking for it all.

So just who is Big Brother now?

The defense of Rice overlooks another crucial detail. Despite the huffing and puffing of the likes of Andy Kaufman lookalike Adam Schiff and every talking shill on CNN/MSNBC/ABC/NBC/CBS and writing shill on the NYT/WaPoo, etc., all of the allegations of collusion have produced bupkis in terms of actual, you know, evidence. We are treated to stories about peripheral figures like Carter Page and Paul Manafort dating from about the time of the Trojan War (in political time), but nothing of substance. Even the Flynn “bombshell” is something of a dud: what he actually said to the Russian ambassador has not been revealed, strongly suggesting that nothing explosive transpired–if it had, you can be sure we would have heard of it by now. My colleague and eminent scholar of Russia Paul Gregory, no shill for Putin, believe me, writes persuasively of the emptiness of the allegations, and their baleful impact on our politics. It even appears that Obama is trying to end this line of attack. There is little doubt that the linked article originated from the Obama camp, and its timing is particularly interesting now that it looks like the issue is boomeranging on him and his closest aides.

I would also point out some other 1984 echoes in the Obama tenure. Consider this nauseating piece on how different official photography of the White House is under Trump as compared to Obama:

Many of the most iconic photos of Barack Obama’s presidency came from Pete Souza, the official White House photographer. Granted extensive access to Obama, he shot the Osama Bin Laden war room photo, moments the president shared with Michelle Obama, the many famous images of the president interacting with kids, and countless more. These carefully composed photos so defined the public image of Obama that it nearly made Souza a household name.

In its visual representation, as in so many other respects, the Trump administration has made a break with the past. Most of what we see of Trump comes from either the traveling pool of press photographers or the smartphones of his staff. On the one hand there are Getty Images or Reuters shots of Trump standing at podiums (or pretending to drive a truck). And on the other, we get unusually informal images of him posing with world leaders or appearing to be caught off guard. In the meantime, the White House’s Flickr account was purged, and the “Photos” section was removed from the official website.

In other words, Obama deliberately created a cult of personality, using “carefully composed” “iconic” (there’s a tell!) photos to “define the public image of Obama.” Yes, Trump is a narcissist, but he could learn something about narcissism from Obama, who from long before he became president obsessed about creating a public image–a personality cult, in all but name.

And the U-turn to the late-Obama administration and current Democratic hysteria over Russia, the Monopoly of Evil (none of this wimpy multi-country axis stuff) from the previous Reset/”tell Vladimir that after my election I have more flexibility”/”the 1980s called and want their foreign policy back” policies bears more than a little similarity to 1984’s Oceania Has Always Been at War With Eastasia. Alas, whereas in 1984 there was only Hate Week, we are now well into Hate Year.

So those tramping to a revival of 1984 to protest Trump are way, way late to the game. They should have expressed their outrage years ago. But that’s when they were all part of Big Brother’s personality cult, wasn’t it?

*I’ve got nothing against f-bombers! There was a time when I could be the B-52 of f-bombers

March 27, 2017

No, I Haven’t Gone Soft on Putin: It’s That I Understand Who the Real Menace Is

I spoke to my uncle over the weekend. He asked me, in all seriousness: “You haven’t written anything about Vlad lately. You going soft?”

My answer: “No–not going soft. But there are so many know-nothing lunatics shrieking about Putin that I don’t want to run the risk of being lumped in with them or confused with them or giving them any credence.” (If you think “know-nothing lunatic” is too strong, check out the Twitter timelines of Louise Mensch or John Schindler. You’ll see I’m actually being overly generous.)

And here’s the truly perverse thing about the hysteria. The lunatics are Putin’s most useful allies. If he really desired to create havoc in the American political system–which I would have no problem believing–in his wildest dreams he couldn’t have done the amount of damage that is now being wreaked by the Democrats and the media (I repeat myself, I know). They are using Putin and Russia as the pretext to carry out their own political vendettas, and to express their rage at losing a race that they just knew was in their pocket. By massively overreacting to rather pitiful allegations (Podesta’s emails–really?) for purely partisan reasons they are doing far worse harm to the US than Putin could have ever hoped of doing.

I know Putin has an obsession with the US, and would love nothing more to undermine it. But his best sappers are unwitting ones, and Americans to boot. And bizarrely, they are doing their sabotage in the name of fighting Putin. I have never seen anything so demented and destructive in all my living days: it is so twisted it is difficult to explain it. Given that, it is far more important that I go after them, and leave Putin out of it. They are the immediate menace, and fighting them is not only justified in its own right, it is also the most direct way of depriving Putin of a chance to weaken the US.

Seeing the OTC Derivatives Markets (and the Financial Markets) Like a State

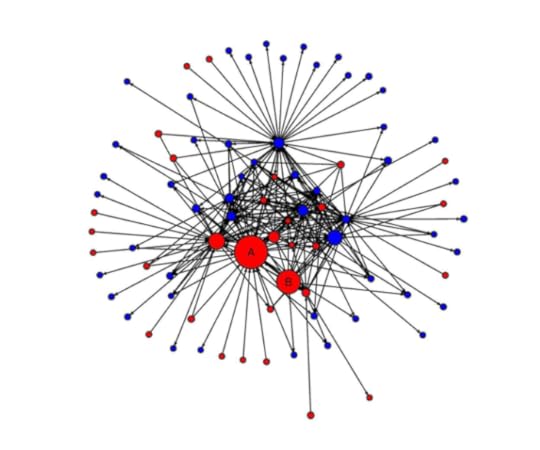

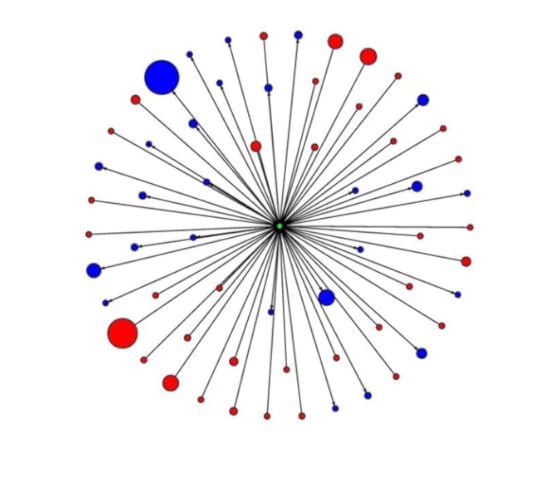

In the years since the financial crisis, and in particular the period preceding and immediately following the passage of Frankendodd, I can’t tell you how many times I saw diagrams that looked like this:

The top diagram is a schematic representation of an OTC derivatives market, with a tangle of bilateral connections between counterparties. The second is a picture of a hub-and-spoke trading network with a CCP serving as the hub. (These particular versions of this comparison are from a 2013 Janet Yellen speech.)

These diagrams came to mind when re-reading James Scott’s Seeing Like a State and his Two Cheers for Anarchism. Scott argues that states have an obsession with making the societies they rule over “legible” in order to make them easier to tax, regulate, and control. States are confounded by evolved complexity and emergent orders: such systems are difficult to comprehend, and what cannot be comprehended cannot be easily ruled. So states attempt to impose schemes to simplify such complex orders. Examples that Scott gives include standardization of language and suppression of dialects; standardization of land tenure, measurements, and property rights; cadastral censuses; population censuses; the imposition of familial names; and urban renewal (e.g., Hausmann’s/Napoleon III’s massive reconstruction of Paris). These things make a populace easier to tax, conscript, and control.

Complex realities of emergent orders are too difficult to map. So states conceive of a mental map that is legible to them, and then impose rules on society to force it to conform with this mental map.

Looking back at the debate over OTC markets generally, and clearing, centralized execution, and trade reporting in particular, it is clear that legislators and regulators (including central banks) found these markets to be illegible. Figures like the first one–which are themselves a greatly simplified representation of OTC reality–were bewildering and disturbing to them. The second figure was much more comprehensible, and much more comforting: not just because they could comprehend it better, but because it gave them the sense that they could impose an order that would be easier to monitor and control. The emergent order was frightening in its wildness: the sense of imposing order and control was deeply comforting.

But as Scott notes, attempts to impose control on emergent orders (which in Scott’s books include both social and natural orders, e.g., forests) themselves carry great risks because although hard to comprehend, these orders evolved the way they did for a reason, and the parts interact in poorly understood–and sometimes completely not understood–ways. Attempts to make reality fit a simple mental map can cause the system to react in unpredicted and unpredictable ways, many of which are perverse.

My criticism of the attempts to “reform” OTC markets was largely predicated on my view that the regulators’ simple mental maps did great violence to complex reality. Even though these “reform” efforts were framed as ways of reducing systemic risk, they were fatally flawed because they were profoundly unsystemic in their understanding of the financial system. My critique focused specifically on the confident assertions based on the diagrams presented above. By focusing only on the OTC derivatives market, and ignoring the myriad connections of this market to other parts of the financial market, regulators could not have possibly comprehended the systemic implications of what they were doing. Indeed, even the portrayal of the OTC market alone was comically simplistic. The fallacy of composition played a role here too: the regulators thought they could reform the system piece-by-piece, without thinking seriously about how these pieces interacted in non-linear ways.

The regulators were guilty of the hubris illustrated beautifully by the parable of Chesterton’s Fence:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.

In other words, the regulators should have understood the system and why it evolved the way that it did before leaping in to “reform” it. As Chesterton says, such attempts at reformation quite frequently result in deformation.

Somewhat belatedly, there are efforts underway to map the financial system more accurately. The work of Richard Bookstaber and various colleagues under the auspices of the Office of Financial Research to create multilayer maps of the financial system is certainly a vast improvement on the childish stick figure depictions of Janet Yellen, Gary Gensler, Timmy Geithner, Chris Dodd, Barney Frank et al. But even these more sophisticated maps are extreme abstractions, not least because they cannot capture incentives, the distribution of information among myriad market participants, and the motivations and behaviors of these participants. Think of embedding these maps in the most complicated extensive form large-N player game you can imagine, and you might have some inkling of how inadequate any schematic representation of the financial system is likely to be. When you combine this with the fact that in complex systems, even slight changes in initial conditions can result in completely different outcomes, the futility of “seeing like a state” in this context becomes apparent. The map of initial conditions is inevitably crude, making it an unreliable guide to understanding the system’s future behavior.

In my view, Scott goes too far. There is no doubt that some state-driven standardization has dramatically reduced transactions costs and opened up new possibilities for wealth-enhancing exchanges (at some cost, yes, but these costs are almost certainly less than the benefit), but Scott looks askance at virtually all such interventions. Thus, I do not exclude the possibility of true reform. But Scott’s warning about the dangers of forcing complex emergent orders to conform to simplified, “legible”, mental constructs must be taken seriously, and should inform any attempt to intervene in something like the financial system. Alas, this did not happen when legislators and regulators embarked on their crusade to reorganize wholesale the world financial system. It is frightening indeed to contemplate that this crusade was guided by such crude mental maps such as those supposedly illustrating the virtues of moving from an emergent bilateral OTC market to a tamed hub-and-spoke cleared one.

PS. I was very disappointed by this presentation by James Scott. He comes off as a doctrinaire leftist anthropologist (but I repeat myself), which is definitely not the case in his books. Indeed, the juxtaposition of Chesterton and Scott shows how deeply conservative Scott is (in the literal sense of the word).

March 26, 2017

Counting the Days Until Jerry Brown Raises the Confederate Flag Over Sacramento

For more than a century, progressives have tried to read the 9th and 10th Amendments out of the Constitution. Some conservatives and libertarians periodically attempted to argue that the amendments could be used as a check on federal power: whenever they did so, the left assailed them as extremist cranks–that is when they did not accuse them of racism and other reprobate tendencies:

[Senator Mike] Lee is a “Tenther,” part of a new extremist movement that seeks to brand all major federal legislation — not only labor regulation, but environmental laws, gun control laws, and Social Security and Medicare — as violations of the “rights” of states as supposedly spelled out in the Tenth Amendment.

But that view is soooo pre-Trump. Post-20 January, 2017, the progressive left is enamored with these amendments, and is seizing upon them as a talisman to ward off the evil Trump spirits. Want proof? Look no further than Governor Moonbeam himself, Jerry Brown:

Despite some recent threats from the president to use federal funding as a “weapon” against the state if it voted to become a sanctuary state, the Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown gave a tough rebuttal in an interview on NBC’s “Meet the Press” this week from the nation’s capital.

“We do have something called the ninth and the 10th amendment,” Brown said.

“The federal government just can’t arbitrarily for political reasons punish the State of California, that’s number one,” he said.

Jerry Brown, Tenther. I wait with bated breath for The Atlantic to label him an extremist fellow traveler of Mike Lee.

Under Brown’s leadership, California is moving to become a “sanctuary state”. As such, it would not be able to prevent the operation of federal law enforcement of immigration laws, but it would bar local and state cooperation with such efforts. In response, Trump has threatened to pull federal funding, and it is this that Brown considers a violation of the amendments that his ilk previously considered Constitutional dead letters appealed to only by right wing freaks.

The sanctuary state movement (which includes Maryland as well) edges very close to advocating nullification of federal immigration laws: it is interesting to note that nullifiers on the right routinely appeal to the 10th Amendment. To do so in defiance of a Jacksonian president is quite risky, in light of how it worked out for South Carolina in the 1830s in its conflict with the original Jacksonian. Like Jackson, Trump may well take up the challenge. Because of his personality. Because immigration is one of his signature issues. Because he is on firm legal ground, since courts have been decidedly hostile to 10th Amendment based claims (although I would not be surprised if leftist judges followed the example of Brown and find a strange new respect for the 10th). And since politically it should cost little: California (and Maryland and other states likely to pursue sanctuary legislation) aren’t going to vote for Trump anyways. This is the kind of fight someone like Trump relishes.

But regardless of whether Brown and Trump come to legal blows over sanctuary status, it is beyond amusing to see progressives man the 10th Amendment barricades. I expect any day now that Jerry Brown will take up the states rights banner, and raise the Confederate flag over Sacramento. Even if he doesn’t go quite that far, the mere fact that he cites amendments that the left once scorned and which the hardcore right embraced demonstrates just how thoroughly Trump has scrambled American politics.

March 24, 2017

Creative Destruction and Industry Life Cycles, HFT Edition

No worries, folks: I’m not dead! Just a little hiatus while in Geneva for my annual teaching gig at Université de Genève, followed by a side trip for a seminar (to be released as a webinar) at ESSEC. The world didn’t collapse without my close attention, but at times it looked like a close run thing. But then again, I was restricted to watching CNN so my perception may be a little bit warped. Well, not a little bit: I have to say that I knew CNN was bad, but I didn’t know how bad until I watched a bit while on the road. Appalling doesn’t even come close to describing it. Strident, tendentious, unrelentingly biased, snide. I switched over to RT to get more reasonable coverage. Yes. It was that bad.

There are so many allegations regarding surveillance swirling about that only fools would rush in to comment on that now. I’ll be an angel for once in the hope that some actual verifiable facts come out.

So for my return, I’ll just comment on a set of HFT-related stories that came out during my trip. One is Alex Osipovich’s story on HFT traders falling on hard times. Another is that Virtu is bidding for KCG. A third one is that Quantlabs (a Houston outfit) is buying one-time HFT high flyer Teza. And finally, one that pre-dates my trip, but fits the theme: Thomas Peterffy’s Interactive Brokers Group is exiting options market making.

Alex’s story repeats Tabb Group data documenting a roughly 85 percent drop in HFT revenues in US equity trading. The Virtu-KCG proposed tie-up and the Quantlabs-Teza consummated one are indications of consolidation that is typical of maturing industries, and a shift it the business model of these firms. The Quantlabs-Teza story is particularly interesting. It suggests that it is no longer possible (or at least remunerative) to get a competitive edge via speed alone. Instead, the focus is shifting to extracting information from the vast flow of data generated in modern markets. Speed will matter here–he who analyzes faster, all else equal, will have an edge. But the margin for innovation will shift from hardware to data analytics software (presumably paired with specialized hardware optimized to use it).

None of these developments is surprising. They are part of the natural life cycle of a new industry. Indeed, I discussed this over two years ago:

In fact, HFT has followed the trajectory of any technological innovation in a highly competitive environment. At its inception, it was a dramatically innovative way of performing longstanding functions undertaken by intermediaries in financial markets: market making and arbitrage. It did so much more efficiently than incumbents did, and so rapidly it displaced the old-style intermediaries. During this transitional period, the first-movers earned supernormal profits because of cost and speed advantages over the old school intermediaries. HFT market share expanded dramatically, and the profits attracted expansion in the capital and capacity of the first-movers, and the entry of new firms. And as day follows night, this entry of new HFT capacity and the intensification of competition dissipated these profits. This is basic economics in action.

. . . .

Whether it is by the entry of a new destructively creative technology, or the inexorable forces of entry and expansion in a technologically static setting, one expects profits earned by firms in one wave of creative destruction to decline. That’s what we’re seeing in HFT. It was definitely a disruptive technology that reaped substantial profits at the time of its introduction, but those profits are eroding.

That shouldn’t be a surprise. But it no doubt is to many of those who have made apocalyptic predictions about the machines taking over the earth. Or the markets, anyways.

Or, as Herb Stein famously said as a caution against extrapolating from current trends, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Those making dire predictions about HFT were largely extrapolating from the events of 2008-2010, and ignored the natural economic forces that constrain growth and dissipate profits. HFT is now a normal, competitive business earning normal, competitive profits. And hopefully this reality will eventually sink in, and the hysteria surrounding HFT will fade away just as its profits did.

The rise and fall of Peterffy/Interactive illustrates Schumpeterian creative destruction in action. Interactive was part of a wave of innovation that displaced the floor. Now it can’t compete against HFT. And as the other articles show, HFT is in the maturation stage during which profits are competed away (ironically, a phenomenon that was central to Marx’s analysis, and which Schumpeter’s theory was specifically intended to address).

This reminds me of a set of conversations I had with a very prominent trader. In the 1990s he said he was glad to see that the markets were becoming computerized because he was “tired of being fucked by the floor.” About 10 years later, he lamented to me how he was being “fucked by HFT.” Now HFT is an industry earning “normal” profits (in the economics lexicon) due to intensifying competition and technological maturation: the fuckers are fucking each other now, I guess.

One interesting public policy issue in the Peterffy story is the role played by internalization of order flow in undermining the economics of Interactive: there is also an internalization angle to the Virtu-KCG story, because one reason for Virtu to buy KCG is to obtain the latter’s juicy retail order flow. I’ve been writing about this (and related) subjects for going on 20 years, and it’s complicated.

Internalization (and other trading in non-lit/exchange venues) reduces liquidity on exchanges, which raises trading costs there and reduces the informativeness of prices. Those factors are usually cited as criticism of off-exchange execution, but there are other considerations. Retail order flow (likely uninformed) gets executed more cheaply, as it should because it it less costly (due to the fact that it poses less of an adverse selection risk). (Who benefits from this cheaper execution is a matter of controversy.) Furthermore, as I pointed out in a 2002 Journal of Law, Economics and Organization paper, off-exchange venues provide competition for exchanges that often have market power (though this is less likely to be the case in post-RegNMS which made inter-exchange competition much more intense). Finally, some (and arguably a lot of) informed trading is rent seeking: by reducing the ability of informed traders to extract rents from uninformed traders, internalization (and dark markets) reduce the incentives to invest excessively in information collection (an incentive Hirshleifer the Elder noted in the 1970s).

Securities and derivatives market structure is fascinating, and it presents many interesting analytical challenges. But these markets, and the firms that operate in them, are not immune to the basic forces of innovation, imitation, and entry that economists have understood for a long time (but which too many have forgotten, alas). We are seeing those forces at work in real time, and the fates of firms like Interactive and Teza, and the HFT sector overall, are living illustrations.

March 11, 2017

One Degree of Idiocy: Michael Weiss Expounds on Trump-Putin Connections

Some years ago, “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” was somewhat popular. The object of the game was to connect any randomly chosen actor to Kevin Bacon in six movies or less.

Today, the game that is all the range in DC and the media is Six Degrees of Donald Trump. The main difference is that the starting point is not any randomly chosen individual, but one very specific individual: Vladimir Putin.

Not surprisingly, the most demented and absurd entry in this game was submitted by Michael Weiss of the Daily Beast. Here’s how it goes. Putin is connected to Gazprom. Gazprom was a participant in a consortium (which also included European energy giants Shell, ENGIE, Winterhall, OMV, and Uniper) to build the Nordstream 2 pipeline. This consortium hired McClarty Associates as a lobbyist. McClarty employs ex-US diplomat Richard Burt. Burt made suggestions about Russia policy that a third party passed on to Trump. As a bonus connection, Burt attended two dinners hosted by Jeff Sessions, and wrote white papers for him.

Burt has never met Trump. Like many in the foreign policy establishment, Burt advocates a pragmatic approach to Russia. He was engaged in diplomacy with the USSR while in the Reagan administration (hardly a hotbed of commsymps and Russophiles), and shockingly, has continued to do business in Russia in the past 30 years. But apparently under the Oceania Has Always Been at War With Eastasia mindset that dominates DC at present, this is tantamount to Burt being a Russian puppet (a view that requires the consignment of most of the history of that period, not least of all that of the Obama administration 2009-2014, to the Memory Hole).

As far as connections are concerned, this is about as tenuous as one can get. The headline (“The Kremlin’s Gas Company Has a Man in Trumpland”) is a vast overstatement. For one thing, Burt is barely in Trumpland. Indeed, although the article says that the connection offers “Republican bona fides,” it is almost certain that was not the reason for hiring McClarty. Astoundingly, the article fails to note that said McClarty himself is a Clintonoid: Mack McClarty is from an old-time Arkansas political family, was closely connected to Bill Clinton in Arkansas, and was Clinton’s first chief of staff. Weiss ominously starts his piece with a recounting of the importance of having a krysha (“roof”, i.e., political protection) and insinuates that hiring Burt was intended to obtain a roof in the Trump administration. But if anything, it would have been an entree into a Clinton administration–which, of course, everybody figured was an inevitability.

Furthermore, perhaps Weiss hasn’t noticed, but “Republican bona fides” are hardly a ticket into Trumpland. Trump’s relationship with the party establishment varies between the hostile and the transactional.

And the timing is all wrong: the contract was signed before Trump was even the Republican nominee, and at a time when no one figured he would be the party’s candidate, let alone president. Talk about a deep out-of-the-money option.

It’s also rather bizarre that the connection between Burt and Gazprom also involves several very large European companies, and a purely European issue. There is nary an American company involved, and the matter is an intramural European spat pitting eastern vs. western EU countries. Wouldn’t you think that if you are trying to buy influence in the United States, you’d engage McClarty/Burt on an issue that would allow them to interact with US officials and politicians?

Further, if you are going to buy a krysha in the Trump administration, dontcha think you’d want to hire somebody who, you know, actually knows Trump?

But our Mikey is not deterred by such pesky details. He has a connection between Putin and Trump, and he is going to flog it for all it’s worth. Which isn’t much.

Of course the details of the Burt-Trump (non-) connection alone wouldn’t make for much of an article, especially for Weiss, who typically drones on paragraph after endless paragraph. So he adds gratuitous ad hominem attacks on Burt, such as comparing him to the late Russian UN ambassador Vitaly Churkin (career diplomats are a type–who knew?), and trotting out Bill Browder, who snarked about how gauche the Russian influence efforts were back in the bad old days (you know, when he was on the make in Russia) and yet again drags out the corpse of his lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, in order to score political points.

Weiss also notes that McClarty has been retained by a Mikhail Fridman company in the UK, but fails to point out that Fridman is hardly a Putin pet. Indeed, Fridman took on Sechin, and came out the winner. But in Weiss’ worldview–which makes that of a 1950s John Bircher look nuanced by comparison–all them Russkies are Putin pawns.

And the anti-Trump establishment should at least get its story straight. On the same day that Weiss’ article appeared, Foreign Policy ran a piece claiming that Tillerson is a weak Secretary of State (the weakest ever, in fact!) because he doesn’t have Trump’s ear. So Trump ignores his own Secretary of State but somehow a guy whom he has never met and who has no position in the administration exerts some great influence over him? And weren’t we told a month ago that Tillerson was going to be Putin’s cat’s paw in the Trump administration because of his extensive dealings there (including with Gazprom in Sakhalin I)? But now he’s a nobody? Damn, that Memory Hole is getting a helluva workout.

Indeed, if the Burt connection (such as it is) and the like are the best that these people can come up with, they are doing a great job of showing how limited and tenuous Trump’s ties to Russia are. And remember the whole point of the Kevin Bacon game: it was a cutesy way of illustrating the “six degrees of association” theory, which posits that any two people in the world are separated by no more than six acquaintances. Any two people, no matter how obscure. Play Six Degrees of Vladimir Putin using yourself as the terminal connection: I bet you could connect with Vlad in six steps or less. I know I can. And does make me some sort of Putinoid? Hardly, as anyone who has read this blog knows.

When major international figures are involved, moreover, there are inevitably multiple such connections, often involving less than six steps. So finding a connection is about as earth shattering as finding sand on a beach. Furthermore, when considering a figure like Trump, he has myriad connections to other figures, many of whom may have interests and views contrary to Putin’s/Russia’s, or orthogonal thereto. Ignoring all these other contrary connections and focusing monomaniacally on ties to Putin and Russia when attempting to predict or explain Trump’s motivations is beyond asinine. In econometrics, this is called omitted variable bias–if you omit relevant variables, you get a very biased estimate of the influence of the ones you include.

But this is what passes for journalism in the United States right now: parlor games posing as deep analysis, latent with dark meanings.

March 10, 2017

US Shale Puts the Saudis and OPEC in Zugzwang

This was CERA Week in Houston, and the Saudis and OPEC provided the comedic entertainment for the assembled oil industry luminaries.

It is quite evident that the speed and intensity of the U-turn in US oil production has unsettled the Saudis, and they don’t know quite what to do about it. So they were left with making empty threats.

My favorite was when Saudi Energy Minister Khalid al-Falih said there would be no “free rides” for US shale producers (and non-OPEC producers generally). Further, he said OPEC “will not bear the burden of free riders,” and “[w]e can’t do what we did in the ’80s and ’90s by swinging millions of barrels in response to market condition.”

Um, what is OPEC going to do about US free riders? Bomb the Permian? If it cuts output, and prices rise as a result, US E&P activity will pick up, and damn quick. The resulting replacement of a good deal of the OPEC output cut will limit the price impact thereof. The best place to be is outside a cartel that cuts output: you can get the benefit of the higher prices, and produce to the max. That’s what is happening in the US right now. OPEC has no credible way of showing off, or threatening to show off, free riders.

As for not doing what they did in the ’80s, well that’s exactly OPEC’s problem. It’s not the ’80s anymore. Now if it tries to “swing millions of barrels” to raise price, there is a fairly elastic and rapidly responding source of supply that can replace a large fraction of those barrels, thereby limiting the price impact of the OPEC swingers, baby.

Falih’s advisers were also trying to scare the US producers. Or something:

“One of the advisors said that OPEC would not take the hit for the rise in U.S. shale production,” a U.S. executive who was at the meeting told Reuters. “He said we and other shale producers should not automatically assume OPEC will extend the cuts.”

Presumably they are threatening a return to their predatory pricing strategy (euphemistically referred to as “defending market share”) that worked out so well for them the last time. Or perhaps it is just a concession that US supply is so elastic that it makes the demand for OPEC oil so elastic that output cuts are a losing proposition and will not endure. Either way, it means that OPEC is coming to the realization that continuing output cuts are unlikely to work. Meaning they won’t happen.

OPEC also floated cooperation with US producers on output. Mr. al-Falih, meet Senator Sherman! And if the antitrust laws didn’t make US participation in an agreement a non-starter, it would be almost impossible to cartelize the US industry given the largely free entry into E&P and the fungibility of technology, human capital, land, services, and labor. Maybe OPEC should hold talks with the Texas Railroad Commission instead.

Finally, in another laugh riot, OPEC canoodled with hedge funds. Apparently under the delusion that financial players play a material role in setting the price of physical barrels, rather than the price of risk. Disabling speculation could materially help OPEC only by raising the cost of hedging, which would tend to raise the costs of E&P firms, especially the more financially stretched ones. (Along these lines, I would argue that the big increase in net long speculative positions in recent months is not due to speculators pushing themselves into the market, but instead they have been pulled into the market by increased hedging activity that has occurred due to the increase in drilling activity in the US.)

Oil prices were down hard this week, from a $53 handle to a (at the time of this writing) $49.50 price. The first down-leg was due to the surprise spike in US inventories, but the continued weakness could well reflect the OPEC and Saudi messaging at CERA Week. The pathetic performance signaled deep strategic weakness, and suggests that the Saudis et al realize they are in zugzwang: regardless of what they do with regards to output, they are going to regret doing it.

My heart bleeds. Bleeds, I tells ya!

March 4, 2017

Obama v. Trump: Strictly Correct & Misleading v. Not Strictly Correct But Fundamentally True

I won’t comment in detail on the substance of today’s latest outbreak of our fevered politics: Trump’s accusation that Obama ordered wiretapping of Trump Tower and the Trump campaign. I will just mention one fact that strongly supports the veracity of Trump’s allegation: namely, the very narrow–and lawyerly–“denials” emanating from the Obama camp.

Obama and his surrogates–notably the slug (or is he a cockroach?) Ben Rhodes–harrumph that Obama could not unilaterally order electronic surveillance. Well, yes, it is the case that Obama did not personally issue the order: the FISA court did so. But even if that is literally correct, it is also true that the FISA court would not unilaterally issue such an order: it would only do so in response to a request from the executive branch. Thus, Obama is clearly implicated even if he did not issue the order. He could have ordered his subordinates to make the request to the court, or could have approved a subordinate’s request to seek an order. Maybe he merely hinted, a la Henry II–“will no one rid me of this turbulent candidate?” (And “turbulent” is a good adjective to apply to Trump.) But regardless, there is no way that such a request to the court in such a fraught and weighty matter would have proceeded without Obama’s acquiescence.

I therefore consider that the substance of Trump’s charge–that he was surveilled at behest of Obama has been admitted by the principals.

This episode illustrates a broader point that is definitely useful to keep in mind. What Obama and his minions (and the Democrats and many in the media) say is likely to be correct, strictly speaking, but fundamentally misleading. In contrast, what Trump says is often incorrect, strictly speaking, but captures the fundamental truth. I would wager that is the case here.

The lawyer word games are not limited to this episode. The entire Sessions imbroglio smacks of scumbag lawyer tactics. The Unfunny Clown, Senator Al Franken, asked (in a convoluted way) a very narrow question (which was related to an even narrower written question in a set of interrogatories) about Session’s interactions with the Russians. Sessions answered the question–which was not an unconditional query about contacts with the Russians, but which related to very specific types of contacts and discussions. Franken and the Democrats then accused Sessions of perjury because the Senator (and then-Attorney General designate) had met with the Russian ambassador to the US on two occasions. Asking a narrow question, and then claiming the answer was a false response to a broader question (that was not asked) is a sleazy lawyer trick (and one that has been tried on me, BTW).

One last thing. Why did Trump push this button today? I can think of offensive and defensive reasons. Offensively, he might want to gain the initiative in the war against Obama and the intelligence community. Defensively, this could be an excellent way of derailing the Russia hysteria, and the calls for an investigation. If it turns out that there was an FBI investigation, and it turned up nothing, then there is no justification for further investigation, whether by Congress or law enforcement. So it could actually help Trump if the FBI and the intelligence community were forced to acknowledge that they had investigated, to no avail. By raising the issue, Trump is pressuring the FBI to put up or shut up.

Figuring out Trump’s reasoning is always hard, but it is worth remembering that he is often at his most clever when he appears to be at his most unhinged and outrageous. So stay tuned. This isn’t over. By a long shot. And given that Trump has emerged triumphant whenever his foes have declared him to be dead meat, I would be very nervous right now if I were Barry or Ben or anyone in the IC.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers